Antiochus VII

Antiochus VII. Euergetes (* 164 or around 160 BC; † 129 BC ; also called Antiochus Sidetes ) ruled from 138 to 129 BC. As king of the Seleucid Empire and is considered the last important ruler of this Hellenistic state.

After the capture of his brother, the Seleucid king Demetrios II. , By the Parthians , Antiochus, who had grown up abroad up to that point, raised a claim to rule in his father's realm. With the support of Demetrios' wife Cleopatra Thea , he was able to prevail in a military dispute against Diodoto's Tryphon , his brother's previous rival to the throne. With this he ended the long civil wars in the Seleucid Empire, which only broke out again after his death. To legitimize his rule, he married his sister-in-law Cleopatra Thea.

In his nine-year reign, Antiochus endeavored with some success to reverse the massive losses of territory and authority of the past decades. Of the numerous wars he waged for it, only the one against the independence movement of the Maccabees in Palestine is better known. This conflict led to a siege of Jerusalem that lasted several months , which ended with a compromise. In the peace treaty that was concluded, the Jews were able to maintain their internal autonomy, but were again firmly integrated into the Seleucid Empire.

131 BC BC Antiochus finally began a large-scale campaign against the Parthians, the most aggressive enemy of the Seleucid Empire at the time. The military advance was initially extremely successful: in the first year of the war, his army brought Mesopotamia under its control, in the second it advanced into the Parthian heartland southeast of the Caspian Sea . While his soldiers were decentralized into winter camps there, the Parthian king Phraates II organized a joint uprising of the cities in the region in which the militarily weaker Antiochus and his troops were defeated and perished. His brother Demetrios, whom Phraates had released shortly beforehand for tactical reasons, then took up his second government in the Seleucid Empire. In the following years, however, this shrank again to a comparatively small area in Syria , Cilicia and Koile Syria .

Origin and youth

Antiochus VII came from the Seleucid family , one of the most important Hellenistic ruling families . The progenitor Seleucus I was one of the Macedonian generals who had established rival empires in his domain in the decades after the death of Alexander the Great . Little is known of Antiochus' early years. His father, King Demetrios I , ruled from 162 to 150 BC. And was married to a Laodic, probably his sister . Whether Antiochus came from this connection is not certain and depends on the determination of the year of his birth. So it cannot be ruled out that he was the offspring of a neighboring marriage. Besides him, Demetrios I had two other sons: Antigonus and Demetrios. Antigonus and Laodike were born in 150 BC. After the military defeat and the death of his father by his political adversaries, Demetrios ruled as Demetrios II from 145 to 139/138 BC. And after the death of Antiochus VII in the years 129–125 BC. Over the Seleucid Empire.

The year Antiochus was born can be deduced from a statement in the Chronicle of Eusebius of Caesarea , who cites a historical work by the Neo-Platonic philosopher Porphyrios as a source. It says that the king was 35 years old when he died. From the year of death 129 BC BC can be calculated back that Antiochus 164 BC. Must have come into the world. That would mean he was born in Rome, where his father was held hostage at the time. Edwyn Robert Bevan objected that Demetrios I would surely only accept his sister after he came to power in 162 BC. I got married and the birth of his three sons could only be scheduled after this year. For this reason, he and various other authors put Antiochus' year of birth around 160 BC. Chr. However, since it is by no means certain that Antiochus actually emerged from his father's marriage to his sister Laodike, this conclusion is not compelling. An indication of a late date of birth could be that the Roman historian Justin states that the king was when he came to power in 138 BC. Was "almost a boy" (puer admodum) .

The order in which Demetrios I's three sons were born is also uncertain. Kay Ehling came to the conclusion, based on the inscriptions on Demetrios' coins, that Demetrios could not have been the first-born because of his nickname Philadelphos ("the brother-lover"). Usually only twins or younger brothers adopted this nickname. Since Demetrios was nicknamed in 139 BC. BC obviously in the beginning dispute with Antiochus, this will have been the older one and statements to the contrary in the ancient written sources are probably based on a misunderstanding.

In his historical work Justin writes that Demetrios I in 152 BC. He had two sons, including Demetrios, brought to the city of Knidos in Asia Minor to protect them from the civil war that was raging in Syria. The fact that Antigonus was still 150 BC Was in Syria and was killed there, Kay Ehling suggests that the children brought to Knidos were Demetrios II and Antiochus VII and that Antigonus was only born after this evacuation measure. Antiochus seems to have left Knidos soon, as he spent his youth in the city of Side , which was located in Pamphylia on the south coast of Asia Minor and traditionally had close ties to the Seleucids and the Roman Empire. This later earned him the unofficial nickname Sidetes ("from Side").

Political starting point

Antiochus' reign was preceded by a lengthy phase with various conflicts over the throne. In essence, the pretenders to the throne to two branches of the ruling family, the two children of King Antiochus III. (ruled 223–187 BC) went out. The brothers Antiochus VII and Demetrios II descended from the line of the older son Seleukos IV. The line of the younger son Antiochus IV had already died out, but the two pretenders to the throne, Alexander I and his son Antiochus VI , who were not related to the Seleucids, claimed . to descend from this branch of the family.

Around the year 140 BC Was Demetrios II from the "older line" of the Seleucid house in power. His rival Antiochus VI. from the "younger branch" of the family was 141 BC. Died in childhood. In its place now claimed the general Diodotos Tryphon , who was already the reign for the young Antiochus VI. had led to power in the empire without claiming belonging to the dynasty. Despite this domestic rival, Demetrios II began a campaign against the Parthian Empire, which had been able to conquer large parts of the Seleucid territory - including Mesopotamia - in the previous decade . After initial victories, he got in the middle of 138 BC. Captured by a ruse by the enemy and was married to Rhodogune , a daughter of the Parthian king.

Accession to power

Proclamation as king and preparations for war

Antiochus VII was on the island of Rhodes when the news reached him that his brother Demetrios II had been captured by the Parthians and that the rival to the throne, Diodotos Tryphon, was expanding his sphere of influence as a result. Thereupon he was proclaimed king. It is noteworthy that Demetrios omitted his previous nickname “Philadelphos” (“the sibling lover”) in the title of one of his last coin series, which arose during the Parthian campaign. This could be an indication that the relationship with his brother had already deteriorated during this time, possibly because Antiochus had already shown his own ambitions to rule before Demetrios' capture. In any case, Antiochus began to prepare the war against Tryphon from Rhodes and recruited troops and a fleet. Thereupon he sent letters to the most important cities of his empire to get them on his side for the upcoming battle.

In the 1st book of the Maccabees , the letter which he addressed to the Jewish high priest Simon from "the islands of the sea" is quoted verbatim. In it Antiochus describes himself as king ( βασιλεύς ) and refers to the legitimation of the kingdom of his "fathers", that is, to his membership of the "rightful" ruling dynasty. In addition, the letter not only confirms the previous privileges and freedoms of the Jewish population, but also promises far-reaching new privileges. For example, the Jews are given permission to mint their own coins, have the right to use their newly built fortifications confirmed and are exempt from all duties to the king. The authenticity of this document has been questioned in research, especially since not a single coin of the high priest is known, i.e. he does not seem to have exercised his alleged right to coin. On the other hand, it was objected that the right to mint was indeed an honorable, but not an outstanding privilege, and that Antiochus could also have withdrawn this privilege when he later fell out with the Maccabees. Ultimately, it is not possible to clearly determine whether the document has been handed down in a completely authentic manner, has been subsequently revised or has been entirely forged.

Regardless of the authenticity of the surviving letter text, it can be assumed that all the important cities ( Poleis ) of the Seleucid dominion have received corresponding letters from Antiochus VII. Most of these communications, however, were unsuccessful, apparently due to Tryphon's military presence. This only changed when Cleopatra Thea , the wife of Demetrios II, offered Antiochus that he could go ashore in the port city of Seleukia Pieria, which she controlled , and marry her. Cleopatra's decision is justified by the ancient writer Appian , because she was jealous because of her husband's marriage to the Parthian king's daughter Rhodogune . However, the report by the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus is considered more credible , who considers tactical reasons to be decisive, as Cleopatra hoped to be able to better preserve her life and position of power on the side of her brother-in-law.

Fight against Diodoto's tryphon

Cleopatra Thea's offer made it possible a little later for Antiochus to land with his forces in Seleukia Pieria and to marry the queen. These events were celebrated by minting coins that marked the arrival of the Seleucids in Syria in the spring or mid-138 BC. BC, dated the marriage to the time before October of this year. The direct military presence and the additional legitimation through his marriage to the wife of his predecessor gave Antiochus a considerable authority, which led to various cities and some mercenary troops Tryphons overflowing to him.

In this strengthened position he was able to defeat his adversary in a battle, drive him out of the Seleucid heartland to Palestine and lock him up in the local coastal city of Dora . The author of the 1st Book of Maccabees writes that he had 120,000 foot soldiers and 8,000 horsemen on his side; however, this figure is certainly exaggerated and was perhaps chosen by the author in order to reinforce the impression of divine intervention against Tryphon in the context of the entire text passage. The siege of Dora lasted until 138/137. This is evident from a slinging lead , a small metal projectile that was excavated near the city and on which the following inscription is carved: “For the victory of Tryphon. Dora. Year 5 [= 5th year of Tryphon's reign, ie 138/137]. The city of the Dorians. Taste this fruit. ”(“ ΤΡΥΦΩΝΟ (ς) / ΝΙΚΗ / ![]() [= Phoenician letter Dalet ] L Ε / ΔΩ (ριτῶν) Π (όλεως) ΡΟΥ / ΓΕΥΣΑΙ ”).

[= Phoenician letter Dalet ] L Ε / ΔΩ (ριτῶν) Π (όλεως) ΡΟΥ / ΓΕΥΣΑΙ ”).

After several months Diodotos Tryphon managed to flee the besieged city by ship and first to Ptolemais , then to Orthosia and finally to Apamea . The Roman writer Frontinus reports the anecdote about this escape in his work on lists of wars (strategemata) that Tryphon distributed coins behind him, so that the units of Antiochus were distracted by collecting the money and allowed him to escape. In Apamea, however, Tryphon was seized again after another siege and came in 137 BC. The ancient sources do not agree on the type of death: while Flavius Josephus, Appian and John of Antioch write of a violent death, according to Strabon and Georgios Synkellos he committed suicide. Antiochus VII was the first ruler since his brother's uprising against the then reigning king from 147 BC. BC regained control over the entire - albeit weakened - Seleucid Empire.

Reign

Very little information is available in ancient sources about the reign of Antiochus VII. Only the conflict with the rebellious Jews, which culminated in a siege of Jerusalem, and the campaign against the Parthian Empire, in which the king was killed, are dealt with several times.

From the marriage of Antiochus to Cleopatra Thea a total of five children emerged who are named in the chronicle of Porphyrios in the following order: Laodike, Laodike, Antiochus, Seleukos, Antiochus. It may be the order of birth. According to this, the two daughters would have been born first, of whom nothing is known other than their natural death. The former Antiochus would have been the eldest son - he too is said to have died of an illness. He was left behind in Syria when his father moved against the Parthians, but died shortly after him at the latest (see below in the “ Outlook ” section). Antiochus VII took his son Seleucus with him on his campaign to the east, he was captured by the enemy after the death of his father (see below in the section “ Parthian War: Defeat and Death of Antiochus ”). The other son named Antiochus, presumably the youngest son, was later Antiochus IX. , the 129 BC Was brought abroad by his mother to protect him from his uncle and stepfather Demetrios II when he returned from Parthian captivity.

Foreign policy up to 131 BC Chr.

Since Rome viewed Diodotus Tryphon as a usurper , Antiochus should have quickly recognized it as ruler after consolidating his position of power. According to the prevailing research opinion, in the year 139 BC BC the Roman politician Scipio Aemilianus visited Syria as part of a legation trip through the eastern Mediterranean and negotiated there with a Seleucid king. Some researchers assume that this ruler was Antiochus VII. Since the latter only set out from Rhodes to Syria after his brother was captured in the autumn of that year, chronologically this is virtually impossible; In all probability Scipio met Demetrios II. Years later, when Scipio Aemilianus around 134 BC When he besieged the Spanish city of Numantia in BC , Antiochus sent gifts to him according to a note from the Roman historian Titus Livius , otherwise nothing is known about a personal acquaintance of the two. Antiochus' good relations with the Romans were possibly a reason for his comparatively mild behavior towards the Jews, as they also had good relations with the Senate (see below in the section " Confrontation with the Maccabees: Historical Classification of the Peace Agreement ").

Kay Ehling suspects on the basis of numismatic evidence from Egypt that the Egyptian king Ptolemy VIII wanted to exploit the weak phase of the Seleucid Empire and that it was in 138/137 BC. BC planned an invasion of Phenicia . From the ancient written sources, however, no military conflicts are known. How the relations between the two Hellenistic kingdoms developed in the following years is also unclear. With Athens, "the journalistic and literary center of the Greek world", Antiochus VII maintained good relations. This emerges from a decree of the city, according to which a statue of a Seleucid ambassador named [Me] nodoros or [Ze] nodoros should be placed next to a statue of Antiochus VII on the agora . An Athenian coin series from 134/133 BC. BC with the traditional Seleucid symbols anchor and star possibly also indicates benefits of King Antiochus for the city, another from the period around 130 BC. With the illustration of elephants and the inscription “Antiochus”, BC perhaps refers to the Parthian War that took place at the time. Conversely, Antiochus usually depicted the Athenian city goddess Athena on his own coins , which can be taken as an indication of at least a certain Greek friendliness.

In his remarks on the Parthian War of the years 131–129 BC The ancient author Justin stated that Antiochus had "hardened his army through many border wars" ("multis finitimorum bellis induraverat"). None of these disputes is known from other ancient evidence. It can therefore be assumed that the opponents were not the important neighboring states such as the Ptolemies in Egypt or the Attalids in Asia Minor, for whose history there are numerous sources. Instead, Antiochus may have fought the rebellious Mesopotamian satrap Dionysius the Medes , the Kommagene , which had only just become independent, under his king Samos II, or the first approaches of the separation movement in the Osrhoene . There could be found in the years around 133 BC. Develop a semi-autonomous principality that lasted until the 3rd century AD.

Domestic politics and epithets

Of the domestic political measures of Antiochus VII, only his behavior towards the cities of the Seleucid Empire is known. According to Justin's history, he is said to have conquered and re-annexed the communities that had fallen away from his brother or him in recent years. On the other hand, he seems to have rewarded the cities that remained loyal: This is how Arad coined in 138/137 BC. BC for the first time in 43 years it had its own coins again - it was probably given the right to do so by Antiochus after it had supported him in his fight against Diodotus Tryphon with ships and sailors. Seleukia Pieria , where Antiochus landed with his fleet, coming from Rhodes, is called from these years a "holy and inviolable" (ἱερά καὶ ἄσυλος) city. Apparently, this honorary title was bestowed upon her as a thank you for her loyalty to the Seleucid king. The frequent depiction of the goddess Athena on the coins of his reign is also interpreted in research as an attempt to publicly propagate the overcoming of the long-standing divisions in the Seleucid house: Previously, Alexander I. Balas from the warring, “younger” family branch had this motif used on his coinage, so that the resumption by Antiochus VII. should have represented a symbolic connection to him and therefore a reconciling gesture.

Various Greek ruler names appear in the sources for Antiochus. His official epithet , which is used on most coins and which is also attested by an ancient author with Johannes Malalas , was Euergetes (“benefactor”). Since this nickname had previously been borne by Alexander I, it was possibly also a symbolic reconciliation with the warring family branch. The terms Eusebes (“the pious”, at least used on the Jewish side) and Soter (“savior”) are also documented in literature . With regard to the ruler's nomenclature, a dedicatory inscription from Ptolemais is also relevant, which is addressed to a king named Antiochus and his wife and was originally interpreted as a consecration to Antiochus VII. Thomas Fischer , on the other hand, has proven that she was actually his son Antiochus IX. it was believed that Antiochus VII was the king's father named in the text. This means that Antiochus VII does not bear the nickname Kallinikos ("the victorious") in the said inscription (as had been assumed ), but the nickname Soter , which is already known from literary sources . In most literary sources, however, he is not referred to with one of these formal epithets, but the unofficial nickname Sidetes ("from Side").

According to Justin, after the successful conquest of Babylonia, Antiochus finally took on the nickname Megas ("the great") during the Parthian campaign . On inscriptions he is later referred to as "Great King". On the one hand, by accepting the Megas title from a Greek or Seleucid perspective , he placed himself in the tradition of the Hellenistic kings, who had carried out a large-scale campaign in the east (a so-called anabasis ) before him and were also given this epithet, namely Alexander the great and Antiochus III. On the other hand, the title referred to the office of "Great King" held by the Persian rulers from the Achaemenid family and was intended to establish continuity with these former rulers of the Middle East. A single coin dating from 134/133 BC. BC was coined in Antioch , the epithet Megas shows for the time before the Parthian campaign. Attempts at explaining this have been taken into account that Antiochus was either already before 131 BC. B.C. undertook an earlier Parthian campaign that is not documented in the remaining sources (which, however, is considered unlikely from a historical perspective) or that the nickname, contrary to Justin’s statement, was adopted after the conquest of Jerusalem. The dedicatory inscription from Ptolemais even names Antiochus VII Megistus (“the greatest”); probably this superlative, like the nickname Soter, was only used after his death.

Confrontation with the Maccabees

Origin of the conflict

The relationship between the Seleucid central power and the Jewish population in Palestine had changed since the Maccabees' uprising in the 160s BC. Very changeable. The high priest Simon , who from 143 BC BC was in office, but succeeded in largely consolidating an independent state structure in Judea. Demetrios II granted him extensive autonomy in gratitude for his support in the fight against Diodoto's Tryphon. Antiochus VII, too, had to confirm Simon's privileges during his struggle for rule and also grant him the right to mint (see above under “ Coming to power: proclamation as king and preparations for war ”). In return, he received support in the siege of Dora, according to Flavius Josephus in the form of money and food, according to the 1st Book of Maccabees, including 2000 soldiers and war material. The latter report states that Antiochus refused military support from the Jewish side and did not keep the promises made to the Jews. In view of the military situation, however, this is considered implausible, possibly the author of the text mistakenly brought into play the break between Simon and Antiochus that occurred a little later. More plausible is Josephus' statement that the high priest was briefly one of the “friends” ( φίλοι ) of the king.

In the later course of Dora's siege, however, Antiochus turned against the Jews. The reason for this may have been that he needed regular tax payments from the Jewish areas in Palestine for the consolidation and permanent enforcement of his rule and not just one-off aid, for which he also had to make political concessions. So Antiochus sent his confidante Athenobius to Jerusalem. He demanded the return of the cities of Joppa and Gezer , the evacuation of the Seleucid garrison in the city of David and taxes for all places outside Judea that were in Jewish possession. Alternatively, he wanted to accept a payment of 1000 talents of silver. Since Simon only agreed to surrender 100 talents, Athenobios returned without having achieved anything. Instead, a certain Kendebaios became the Epistrategos appointed (possibly in reference to the same office of Epistrategen in Ptolemaic ) thus equipped with special military and civilian powers for the Greater Palestine. He fortified the city of Kedron and from there undertook military advances into Judea while Antiochus was still pursuing Tryphons. Judas and Johannes Hyrcanus , two sons of the high priest, went into the field with their father against Kendebaios and beat him in 137/136 BC. Near Jamnia . The course of the battle is described in the 1st Book of Maccabees: The two armies faced each other north of Jerusalem near Modein , separated from each other by a raging mountain stream. After a brief hesitation, the allegedly 20,000-strong Jewish army crossed the waters and succeeded in routing the Seleucid troops, pushing back to Kedron and the smaller fortifications around Azotos and killing a total of 2,000 soldiers.

In February 135 BC In BC Simon and his sons Mattathias and Judas were murdered by his son-in-law Ptolemy. The latter then asked Antiochus VII in writing to send troops to his support - from the available sources nothing is known of a direct reaction on the part of the Seleucids. Simon's third son, John Hyrcanus, succeeded a short time later in driving out Ptolemy and becoming the new high priest himself.

Campaign to Palestine and siege of Jerusalem

In the mid-130s, Antiochus began a campaign of revenge against the Maccabees. After devastating the Jewish populated areas, the king moved towards Jerusalem and began to siege the city. These processes are dated inconsistently in the ancient sources, so that modern research came to different dates. For a dating of the siege to the year 135/134 BC However, there are several indications that speak for themselves: Firstly, it is historically plausible that Antiochus took advantage of the situation after the power struggle for the office of high priest - especially since that year was a sabbatical year , which is why he could hope that the fighting strength of the Jews through their religious ones Regulations will be reduced. On the other hand, from the year 134/133 BC A stater is known whose stamp motif, with a characteristic representation of the goddess of victory Nike, indicates a significant military victory and is partly related in research to the successfully completed campaign against the Jews.

The siege of Jerusalem is likely to be 135 BC. It was probably opened in the fall, since according to Flavius Josephus the city was already completely enclosed when the Pleiades fell in November. For this purpose, a double trench was dug around the fortification wall and the city was surrounded by seven army groups. On the north side, where the nature of the terrain allowed this, 100 three-story siege towers were erected, from which daily attacks on the city were launched. But neither these advances nor the failures of the besieged had a decisive effect on the battle.

The incapable of fighting, driven out of the city by Johannes Hyrkanos because of lack of food, were not let through by Antiochus and were therefore stuck between the fronts. Not until Antiochus to celebrate the Feast of Tabernacles , i.e. in September / October 134 BC. At the request of the high priest, he granted a one-week truce and made rich offerings for the religious celebrations of the Jews, the survivors were taken back to Jerusalem by them. Shortly afterwards, Hyrcanus, encouraged by the “pious” and perceived fair behavior of the opposing party at the Feast of Tabernacles, asked for peace by means of an embassy. According to the report of the Greek historian Diodorus , the advisors to Antiochus VII are said to have recommended not to go into it and to exterminate the Jews because of their otherness and their “hatred of people”. The king, on the other hand, was ready to negotiate and demanded the surrender of all weapons, the payment of taxes for the cities outside Judea and the establishment of a garrison in Jerusalem. When the last point provoked displeasure, he instead accepted the extradition of hostages of his choice and a payment of 500 talents of silver. 300 talents of this were paid immediately, for which, according to Flavius Josephus, Hyrcanus had the tomb of King David opened and a total of over 3000 talents took silver from it. Thomas Fischer suspected that the high priest had actually taken the money from the Jerusalem temple located near the tomb of David in order to be able to buy the peace treaty with Antiochus, and only claimed that the money came from the tomb of the early king to cover up this temple robbery . After the crown of the wall of Jerusalem had been symbolically razed , Antiochus withdrew with his army. The fact that an ancient source reports on the killing of Hyrcanus (which is certainly unhistorical) and another of a bloodbath among the most important inhabitants of Jerusalem should not have any historical significance - at best Antiochus could have executed a small number of extremists. In addition, some research has found that the peace conditions also included the Jews renouncing their own foreign policy and performing military service for the Seleucid king - these provisions are not explicitly found in the ancient reports, however.

Historical classification of the peace treaty

The peace conditions clearly restored the royal authority, but were comparatively mild overall - it was not a question of a complete reintegration of the Jews into the Seleucid Empire. The reasons for the behavior of Antiochus, who advanced as far as Jerusalem and besieged it for a year, but brought offerings to the enemy in the meantime and then only claimed the border towns of Judea for himself, have been controversially discussed in research. Thus Tessa Rajak theorize the Roman Senate had asked the Seleucids at the request of a Jewish delegation and for the purposes of the balance of power in the eastern Mediterranean in a letter to lift the siege of Jerusalem. Flavius Josephus' report, according to which Antiochus acted in this way out of pure “piety”, goes back to a historical work by a Hellenistic author used by Josephus as a source (now lost). He was interested in showing King Antiochus in the best possible light and therefore covering up Rome's intervention. Research has largely rejected this interpretation by Rajak without providing a clear alternative theory. The most widespread explanation is that, after a simple profit-loss calculation and in view of the hardening fronts in front of Jerusalem, Antiochus decided to concentrate his resources on the urgently needed Parthian War and to save face on both sides through his peace conditions.

Johann Maier explains the sudden “pious gestures” of the Seleucid king with the double task that he had to fulfill as head of state: “He acted [with the donation of offerings during the siege] as the supreme sovereign who also knew himself to be responsible for the state cult of Jerusalem The siege, on the other hand, was aimed at the insubordinate vassal. ”In his understanding of ruler, care and punishment did not have to be mutually exclusive. Unlike his predecessor Antiochus IV, Antiochus was quite willing to take the sensitivities and religious feelings of the Jews into consideration, as long as this did not lead to the independence of the territory and the collapse of his empire.

In the following years, Hyrcanus apparently actually incorporated himself as a loyal vassal into the Seleucid Empire - Flavius Josephus writes of “friendship and alliance” (“φιλία καὶ συμμαχία”) with the king. In the late 130s, he uniquely minted a large number of bronze coins, the inscription of which mentions the office, name and surname of Antiochus and on which, in addition to the lily as the symbol of high priesthood, the anchor as a traditional emblem of the Seleucid kings is depicted (a portrait of the ruling ruler contradicted the Jewish ban on images ). Some coins from the years 132–130 BC have also survived the outstanding monetary payments for lifting the siege of Jerusalem. Received. They correspond in their design to the typical tetradrachms of Antiochus with his own portrait and a standing representation of the goddess Athene Nikephoros. As a reference to the origin of the silver used, however, the monogram “ΥΡΚΑΝ (ΟΥ)” (“[des] Hyrkanos”) was also imprinted, which means that these coins can be assigned to the 500 talents agreed in the peace treaty. Later, Johannes Hyrcanus took part in the Parthian campaign of Antiochus VII as commander of a Jewish contingent. Only after the death of the Seleucid king did he expand his sphere of influence again and advance into Syria.

Parthian War

Occasion and preparations

Since the year 139 BC The Parthians kept Demetrios II in captivity and probably intended to release him at the appropriate opportunity and play him off against Antiochus VII. The 131 BC The Parthian War that began in BC was a preventive war for him , because the brother and predecessor represented a constant danger in the hands of the enemy. Another reason and probably also a public reason for the campaign was the desire to make up for Demetrios' defeat and the lost territories of the Seleucid Empire. Since the Parthians were weakened by the incursions of nomadic peoples in the north of their empire and the still young King Phraates II from the ruling house of the Arsacids was bound there, the military situation at the end of the 130s BC. Particularly cheap.

Antiochus used the time after the withdrawal from Jerusalem for intensive preparations for the campaign. For this reason, the traditional number of 80,000 to 100,000 soldiers could be quite realistic, as it corresponds to the basic personnel capabilities of the Seleucid Empire. The statement in the ancient sources that 200,000 to 300,000 civilians came along as a train is, however, probably clearly exaggerated. It is assumed that in the reports on the Parthian campaign it was only intended to create a picture of the "oriental" decadence in the Seleucid army. It also fits that the corresponding reports contain decorative details on the pomp of the army, according to Justin, large quantities of luxury goods and precious metals were carried with them, while Orosius writes of "whores and actors" (scortis et histrionibus) in the army's entourage . In any case, it was the last significant army contingent of the Seleucids. The fact that a lot of precious metal, especially in the form of coins, was brought to the eastern areas as a result of the campaign is plausible and actually confirmed numismatically. The corresponding coins must have been in circulation in the Middle East for many centuries, since in the 12th century the Oghuz dynasty of the Ortoqids, ruling in southeastern Anatolia , copied the portrait of Antiochus VII on its bronze coins. Paul J. Kosmin also pointed out that when a Seleucid army went into battle, for ideological reasons, attention was paid to the most effective public display of splendor and wealth, i.e. a true historical core was hidden in the reports of Justin and Orosius should.

Antiochus took the middle of his three sons named Seleukos with him to the Parthian War, while his two other sons named Antiochus were left behind with their mother Cleopatra Thea in the Syrian heartland of the Seleucid Empire.

Advance of the Seleucid army

In his dissertation , Thomas Fischer examined the course of the entire Parthian War and differentiated between two partial campaigns, of which the first 131/130 BC. BC, the second 130/129 BC Took place. Before that, the Parthian War was mostly only in the years 130/129 BC. Has been dated. Fischer's reconstruction of the chronology has been contradicted from various sides, but it is now considered to be somewhat certain. The departure from Syria therefore took place in March 131 BC. While the Parthian king was staying in the east of his empire, numerous local vassal rulers in Mesopotamia defected to the Seleucids even before the first fighting. In three battles, Antiochus then succeeded in defeating Parthian satraps . One of these battles probably took place on the Lykos (a tributary of the Tigris ) against the General Indates , where the Seleucid army erected a monument to victory ( Tropaion ). Since the army then stopped for a few days so that the Jewish fighters could celebrate the festival of weeks (50 days after Passover ), the battle of Lykos can be dated to May or June. Then Antiochus moved back to the Euphrates and along this river to Babylon , where he took the nickname "the great" and wintered with the army. One of his new vassals was in all likelihood the Satrap Hyspaosines , who had been able to maintain his sphere of influence near the Persian Gulf for decades despite the changeable political situation and who later founded the State of Charakene . In his natural history, Pliny the Elder rejects the statement of a non-preserved document by the Mauritanian king Juba II , according to which Hyspaosines was the satrap of a king named Antiochus. However, research has come to the conclusion that the later characteric ruler may well have placed himself in the service of Antiochus VII and Pliny therefore erroneously declared Juba's statement to be false.

Encouraged by the rapid success, Antiochus was able to succeed in the spring of 130 BC. BC let the peace negotiations initiated by Phraates fail due to unacceptably high demands. The Parthian king could not accept the conditions he had set (release of Demetrios II, return of all former Seleucid territories, tribute payments) because they would have made him politically incapable of acting. Antiochus' position was strengthened by the fact that hostile tribes continued to invade the north of the Parthian Empire and Phraates was therefore tied on two fronts.

When the negotiations were broken off, the second part of the campaign began in the spring. The season is determined by the details of Claudius Aelianus and Julius Obsequens confirmed both deliver an anecdote to leave Antiochus in their respective treatises on good and bad omen: At the tent of the Seleucids a swallow had built her nest, what a bad omen have shown but had been ignored by the king. The army marched again in an easterly direction over the Tigris to Susa , conquered Media with the capital Ekbatana and pushed Phraates II in the course of 130 BC. Back to the Parthyena without encountering any resistance worth mentioning in the regions crossed. Possibly it penetrated as far as the coastal region of the Caspian Sea , to Hyrcania . According to the world chronicle of Georgios Synkellos, this is where the nickname of the Jewish high priest Johannes Hyrcanus, who accompanied Antiochus on the campaign, comes from. This is contradicted by the fact that coins from the years 132–130 BC. (See above under discussion of the Maccabees: Historical classification of the peace treaty ) the monogram for "Hyrcanus" is used - nevertheless, this derivation of the name must have been plausible for the ancient public, so that one can assume that Antiochus actually up to Hyrcania advanced. The Parthian king was forced to enter into an alliance with steppe peoples in the north of his empire and to recruit them as mercenaries. These tribes are referred to in the ancient sources with the general term "Scythians", which was customary at the time, and they can probably be specifically identified with the Saks .

Defeat and Death of Antiochus

Towards the end of 130 BC Because of its size, the Seleucid army was divided into the cities of the Parthyene for wintering, which was an enormous burden for these towns. The ruthless action of the army and attacks by the soldiers made the locals look for an opportunity to get rid of the occupation quickly. The fact that the places affected were in the Parthian heartland may have contributed to this dissatisfaction. So it was not a matter of Greek cities that had only recently come under Parthian rule, such as in Mesopotamia, which Antiochus had received enthusiastically. Phraates took advantage of this mood and attacked in February or March 129 BC. With the support of the Parthyenian localities, the individual armies of King Antiochus, which hit him completely unprepared. In his attempt to get the situation under control by means of a quick tactical maneuver, he and some of his troops encountered the Parthian army in a narrow valley. Declining the advice of his friends , who recommended that the conflict be relocated to more favorable territory by retreating, he embarked on a battle with the now numerically superior Parthian army. The ancient sources give the enemy troops a strength of 120,000 men, while Antiochus could only fall back on a fraction of his own armed forces. When it came to a fight, he was also abandoned by his comrades-in-arms and was killed. According to most ancient authors, he fell in battle while Appian and Claudius Aelianus are writing of suicide. In a hopeless situation, suicide would have been an honorable opportunity for Antiochus to escape capture by the Parthians - which of the traditional variants is more likely cannot be determined with certainty.

After the death of Antiochus VII, his son Seleucus, who was about five years old, followed him for a short time as king and nominally assumed command of the rest of the army. There are two different reports about his further fate in the ancient sources: Poseidonios and Porphyrios say that he was captured by them after another battle with the Parthians, but that he was treated extremely well. John of Antioch, on the other hand, writes that Seleucus came into conflict with Demetrios II, who had escaped from Parthian captivity, and was deposed in order to then flee to Phraates, who married him to one of his daughters. In view of these contradicting data, it cannot be clarified whether Seleucus actually fought a battle with the remaining Seleucid army and whether there was a dispute between him and Demetrios for which there is no surviving evidence apart from John of Antioch. In the turmoil after Antiochus' death, Phraates also captured a daughter of Demetrius and married her. Antiochus had probably taken them with him to the east in order to give them to a vassal prince as wife if necessary and thus to secure political control over the conquered territories. Parts of Antiochus' army were subsequently incorporated into the Parthian army - possibly these were mercenaries he had recruited. In a later battle against a nomadic people, however, these soldiers abandoned Phraates II at the decisive moment and turned against him, which allegedly cost the Parthian king his life.

outlook

In late autumn or winter 130 BC According to traditional research, Demetrios II had been released and sent to Syria with Parthian troops, in all probability to open a second front to his brother Antiochus VII as a rival to the throne at home. Another, undoubtedly false, hypothesis is based on the abbreviated description in Appian's Syrian history and says that Phraates only wanted to meet one of the demands of Antiochus during the peace negotiations in the spring with the release of Demetrius. Finally, a third theory developed by Peter Franz Mittag assumes that the Parthians did not hold Demetrius prisoner for tactical reasons, but actually had the goal of acquiring foreign and domestic political prestige by building family ties to a Hellenistic ruling house. Demetrios is therefore 129 BC. BC was not released in order to endanger the political situation of Antiochus VII, but simply fled from the Parthian captivity. At the latest when Antiochus died, Phraates tried to bring Demetrios back and had him pursued by riders. The Parthian king hoped that if a power vacuum arose in the neighboring kingdom, he would be able to conquer it more easily; from a renewed rise to power Demetrios II, he no longer had any tactical advantages to expect. However, the former Seleucid king managed to escape his persecutors, return to Syria and actually take up his second government there (129–125 BC).

The two sons of Antiochus, whom he had not taken with him to the East, had stayed in their Syrian homeland during the Parthian War. In the name of the older of the two, some coins were minted, from which it can be seen that he was appointed king and was nicknamed "Epiphanes" ("the one who appeared"). These coins have been dated differently in research, but according to the latest findings they date from the year 129/128 BC. After the death of Antiochus VII, it seems that his eldest son - probably on the initiative of Cleopatra Theas - was briefly proclaimed ruler in Syria. According to the Chronicle of Porphyry, he died of natural causes. However, this must have happened after a very short time, since when Uncle Demetrios II returned, only his younger brother of the same name was brought to safety abroad, but he himself is no longer mentioned.

In Babylonia, after the victory over the Seleucids, the Parthian king appointed a certain Himeros as governor, who enforced punitive measures against the localities that had joined the Seleucid king . Phraates treated the body of Antiochus VII with honor and had it brought to the Seleucid Empire in a silver coffin, where another conflict of the throne had already broken out. There, according to Justin, the anti-king Alexander II Zabinas accepted the body and had it buried in pretended deep mourning in order to make his fictitious claim that he was an adopted son of Antiochus more credible.

With the crushing defeat of Antiochus VII in the Parthian campaign, the Seleucids lost Mesopotamia, Iran and all other areas east of the Euphrates. Phraates was only prevented from invading Syria by a revolt of the steppe peoples whom he had originally recruited against Antiochus. Around 128 BC He fell fighting them. Nevertheless, the Arsacid Empire was able to maintain all its territorial gains of the previous decades in the following period, while the former Seleucid empire sank to a meaningless middle power. After his return from the Parthian campaign, Johannes Hyrcanus also took advantage of the weakness of the Seleucids to expand Jewish territory again and to gain de facto sovereignty. Domestically, the following decades in the Seleucid Empire until the annexation by the Romans (63 BC) were characterized by constant turmoil and disputes over the throne, which made the state incapable of action for long periods. These internal conflicts were essentially carried out between two branches of the Seleucid house, which were divided between the two brothers Antiochus VII (son Antiochus IX and the alleged son Alexander II Zabinas) and Demetrios II (sons Antiochus VIII and Seleucus V ). derived.

Sources

The sources for the history of the late Seleucid Empire are comparatively poor. Much of the information obtained comes from the lost history of Poseidonius , who wrote a continuation of Polybius ' famous work Historíai . Poseidonios came from the Syrian city of Apamea on the Orontes and was born in 135 BC. Born as a child, for example, the downfall of the Syrian army in 129 BC. And experienced its effects. His lost report had a decisive influence on the ancient sources on Antiochus VII that are preserved today. This applies, for example, to Flavius Josephus , whose writings De bello Judaico and Antiquitates Judaicae represent a central source for the epoch. Josephus and the anonymous author of the 1st Book of Maccabees , through which the most extensive information about Antiochus has been handed down, both write from a Jewish, i.e. non-Seleucid perspective. Above all, Josephus also made extensive use of Seleucid-influenced literature, either directly on Poseidonios or probably more on a third author who in turn had evaluated Poseidonios' work.

In addition to the texts mentioned, there are other reports about Antiochus on the one hand Diodorus in his world history and on the other hand the Latin writer Pompeius Trogus (whose work itself is lost, but is indirectly known through a summary of Justin ). For these authors, too, Poseidonios was the decisive source with regard to the epoch of Antiochus VII. Additional information about his reign can be found in the historical works of Appian (whose eleventh book deals with the history of the Seleucids) and the philosopher Porphyrios (whose "Chronicle" various precise historical data, but also some incorrect years). In addition, there are individual passages from the work “Scholars' Meal” by Athenaios , which primarily contains anecdotal material and stories about personal life on the Seleucid kings, and from Strabon's geographical handbook , which is repeatedly peppered with cultural-historical side remarks. Three Byzantine chroniclers, Georgios Synkellos , John of Antioch, and John Malalas , also contain summarizing sections on Antiochus VII, although the source value of the latter in particular is low. Finally, Claudius Aelianus , Charax of Pergamon , Sextus Iulius Frontinus , Moses of Choren , Iulius Obsequens , Plutarch and Valerius Maximus pass on isolated details about the Seleucid king.

The Roman historian Titus Livius also dealt with the Parthian War of Antiochus VII in his historical work (whereby his main source was apparently again Poseidonius). Only a very brief summary of the corresponding book has been preserved. Orosius , whose Historiae Adversum Paganos contains a short section on the Parthian War, presumably also used a summary of Livy as a source, which was somewhat more detailed than the one preserved today. In the case of two other historical works, it can be assumed that they once existed, but the texts themselves are lost. It is a story of the Seleucid Empire by Flavius Josephus, whose earlier existence Thomas Fischer assumes on the basis of various references in the author's surviving works, and another work by Athenaios with the title “On the Kings of Syria”.

Poseidonios as the reconstructed main source for Antiochus VII not only documented numerous facts in his work, but also made his own clear assessments, which are expressed in some anecdotes that have been handed down. Athenaios quotes two of them in his "Scholarly Banquet" and explicitly gives Poseidonios as his source. One is about decadent and lavish banquets that the Seleucids are said to have arranged for the “common people” (although it is not clear whether this refers to the civilian population or whether the story belongs in the context of the Parthian campaign and relates to the soldiers ). The other anecdote relates to Antiochus' alleged drunkenness, which Phraates II led to the following statement after the death of the Seleucids: “On the ground, Antiochus, you have boldness and carelessness. Because you hoped to be able to drink the Kingdom of Arsakes [= the Parthian Empire] from large cups. "As with the reports on the pomp of the convoy that was taken into the Parthian campaign, it is also possible here that there is a true historical core behind the naturally invented stories: Antiochus VII certainly had to adapt to “oriental forms of life and feasts” during his conquest of the Middle East in order not to be perceived as a foreign ruler there. Another (though not marked as such) fragment of Poseidonios in Athenaios tells of an (otherwise not attested) Epicurean philosopher named Diogenes, who exhibited provocative behavior at the royal court until a king Antiochus - in all likelihood that is Antiochus VII meant - after taking office he had him executed. Finally, Plutarch reports in his " Moralia " that Antiochus had left his entourage one day, "disguised" as a private individual and stopped by ordinary people in a hut and asked them for their opinion about the king - this anecdote was supposed to be close to the people and emphasize the positive character traits of the king.

The Armenian and Georgian written sources offer hardly any relevant information on Antiochus VII due to their geographical and temporal distance. However, his defeat in the Parthian campaign is often considered in them (based on a traditional oriental tradition) as the point in time when the "world domination" of the Hellenistic empires passed to the Parthians. In addition to the literary sources, inscriptions offer important additional information, for example on the titulature of Antiochus VII and his foreign policy relations or on the meaning and self-portrayal of his wife Cleopatra Thea. As the last “western” ruler, Antiochus VII also appears in a cuneiform document from Babylon that the reconquest of this city in 130 BC. Occupied. In addition, for a short period in the years 130 and 129 B.C.E. Chr. In the Babylonian cuneiform texts only dated after the Seleucid era and no longer, as in previous years, by means of a double indication of the Seleucid and Arsakid chronology - an effect of the Seleucid rule over Babylonia during this period. In addition, there are the coins as an extensive group of sources, which enable detailed information about iconography, public self-portrayal and the king's program of rule as well as the spread of the right to mint, but also allow very precise chronological statements to be made through the dates on them.

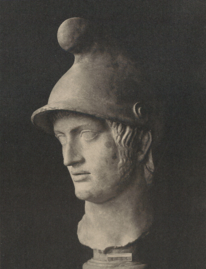

iconography

Pictorial representations that can be ascribed to Antiochus VII with a certain degree of certainty have only survived on his coins. As far as the material has been published and evaluated, its representation there is largely uniform with the exception of the forehead hair. The ruler is depicted with a relatively plump face that is reminiscent of the portrait of his predecessor Diodotos Tryphon and usually has a double chin. The mouth is clearly defined, the upper lip protruding from the lower lip; the nose is comparatively high and in some embossings it is also shown as a hooked nose. The hairstyle consists of strands arranged like a spider on the back of the head; Curls running parallel to each other (so-called "sickle curls") fall over the neck . The forehead hairs are not represented in a completely uniform way in the coinage: They are partly designed in the form of simple, parallel strands, but partly they protrude from the head in a significantly more disordered manner. The first corresponds to the representation of his father Demetrios, while the second hairstyle is based on his direct predecessor. In the rest of the face, too, similarities to the characteristic representation of Demetrios I can be made out.

In his treatise on the Seleucid ruler's portrait, Robert Fleischer lists four portraits, some of which have been interpreted in research as depictions of Antiochus VII. However, this attribution is not considered likely for any of the works of art. The individual works are as follows:

- Marble sculpture of a head in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen (inventory number 447)

- Bronze sculpture of a head in the Iranian National Museum in Tehran (inventory number 2477)

- Silver emblem depicting a head with a Phrygian cap in an approximate frontal view, which was originally attached as a decoration to an object that has not survived; the current location of the emblem is unknown

- Gem in the Louvre in Paris from the collection of Louis De Clercq

In addition, a cameo in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna is identified with Antiochus VII.

State of research and assessment

The last comprehensive overall scientific accounts of the Seleucid rulers' history date back to the beginning of the 20th century: These are the works of Edwyn Robert Bevan and Auguste Bouché-Leclercq , which are still fundamental to the political history of the Seleucid Empire, even if they are no longer the reflect the current state of research. More recent monographs on the Seleucid Empire, on the other hand, have brought structural aspects to the fore, so that they do not contain any more detailed sections on individual rulers such as Antiochus VII. For the period after 164 BC Chr. Has Kay Ehling created with his "Studies on the history of the late Seleucid" and various supplementary essays a certain compensation. In addition to his writings, the work of Thomas Fischer is primarily important for the knowledge of the government of Antiochus VII. In his dissertation he dealt with the Parthian War (especially in chronological and topographical terms) and in various contributions with the coinage of the king.

As a ruler, Antiochus VII has been judged very positively in the history of research: He is often considered the last capable member of the Seleucid dynasty, for example with Thomas Fischer, according to which his successors were "only weak figures". Even Susan Sherwin-White and Amélie Kuhrt expected Antiochus to the "most dynamic and successful" members of his dynasty; Charles Bradford Welles describes him as "the last [n] able [n] king of the Seleucid family". John D. Grainger , who ascribes the political successes of Antiochus VII only to the favorable foreign policy situation during his reign and a general tiredness of war in the Seleucid Empire, not to any particular qualities of rulership, draws a significantly more negative balance sheet . On the other hand, he attributes the positive image of the rest of the research to the sources, since the authors of the traditional ancient texts would have already had a correspondingly colored view of Antiochus.

The key position that Antiochus VII's reign plays in the history of the Seleucid Empire is undisputed in research. So the year 129 BC meant For the Polish ancient historian Józef Wolski “undoubtedly the beginning of the end of the Seleucid monarchy”, and Eduard Meyer already described the death of Antiochus as the “catastrophe of Hellenism in continental Asia and at the same time that of the Seleucid Empire”. David Engels plays through the idea that the Seleucid would have been successful in his great Eastern campaign and would have permanently regained control over Mesopotamia, Persia and possibly the Parthyena. With this possibility - which is absolutely plausible for Engels - the Seleucid Empire could have been preserved in the long term, but then, due to the structure of the ruled territories, it would in all probability have become a feudal state with weak central power (as actually happened with the Parthian Empire).

literature

- Edward Dąbrowa : Kings of Syria in captivity by the Parthians . In: Tyche , Volume 7, 1992, pp. 45-54 ( PDF ). Reprinted in: The same: Studia Graeco-Parthica. Political and Cultural Relations between Greeks and Parthians (= Philippika. Volume 49). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2011, pp. 15-25.

- Kay Ehling : Two 'Seleucid' miscells. In: Historia . Volume 50, Number 3, 2001, pp. 374-378.

- Kay Ehling: Studies on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey (= Historia individual writings. Volume 196). Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 3-515-09035-5 , esp. Pp. 186-205 (habilitation thesis, University of Augsburg 2005).

- Thomas Fischer : Investigations into the Parthian War Antiochus VII. In the context of the Seleucid history. Dissertation, Munich 1970.

- Thomas Fischer: Silver from David's tomb? Jewish and Hellenistic things on coins of the Seleucid king Antiochus VII. 132–130 BC Chr. (= Small notebooks of the coin collection at the Ruhr University Bochum. Number 7). Brockmeyer, Bochum 1983, ISBN 3-88339-325-8 .

- Arthur Houghton , Catharine Lorber, Oliver Hoover: Seleucid Coins. A Comprehensive Catalog. Part 2: Seleucus IV through Antiochus XIII. 2 volumes, American Numismatic Society / Classical Numismatic Group, New York and Lancaster / London 2008, ISBN 978-0-9802387-2-3 , Volume 1, pp. 348-397 and Volume 2 passim (on the coinage of Antiochus VII .; see also Volume 1, pp. 399-407 for later Cappadocian coins in Antiochus' name).

- Charlotte Lerouge-Cohen: Les guerres parthiques de Démétrios II et Antiochos VII dans les sources gréco-romaines, de Posidonios à Trogue / Justin. In: Journal des savants . Year 2005, pp. 217–252 ( online ; close to sources, but not based on current research).

- Peter Franz Mittag : By Demetrios' beard. Reflections on the Parthian captivity of Demetrios II. In: Klio . Volume 84, Number 2, 2002, pp. 373-399.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Titus Livius , Periochae 50.

- ↑ Kay Ehling: Two 'Seleucid' miscells. In: Historia . Volume 50, number 3, 2001, pp. 374–378, here p. 374, note 1.

- ↑ Hugo Willrich : Demetrios 40. In: Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen antiquity science (RE). Volume IV, 2, Stuttgart 1901, Col. 2795-2798, here Col. 2798.

- ↑ Porphyrios, FGrH 260, fragment 32, 19.

- ↑ For example Ulrich Wilcken : Antiochos 30 . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume I, 2, Stuttgart 1894, Col. 2478-2480, here Col. 2478.

- ^ Edwyn Robert Bevan: The House of Seleucus. 2 volumes, Edward Arnold, London 1902 (reprint, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1966), volume 2, p. 302 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Kay Ehling: Two 'Seleucid' miscells. In: Historia. Volume 50, number 3, 2001, pp. 374-378, here pp. 374 and 376.

- ^ Justin, Epitoma historiarum Philippicarum 36,1,8. Translation after: Pompeius Trogus: World history from the beginnings to Augustus in the excerpt of Justin. Edited and translated by Otto Seel . Artemis, Zurich 1972, p. 400.

- ↑ Justin, Epitoma historiarum Philippicarum 35,2,2; Porphyrios, FGrH 260, fragment 32.17.

- ↑ Kay Ehling: Two 'Seleucid' miscells. In: Historia. Volume 50, number 3, 2001, pp. 374-378, here p. 374 f.

- ↑ Justin, Epitoma historiarum Philippicarum 35,2,1 f.

- ↑ Kay Ehling: Two 'Seleucid' miscells. In: Historia. Volume 50, Number 3, 2001, pp. 374-378, here p. 376; Thérèse Liebmann-Frankfort: La frontière orientale dans la politique extérieure de la République romaine depuis le traité d'Apamée jusquà la fin des conquêtes asiatiques de Pompée (189 / 8-63). Académie Royale de Belgique, Brussels 1969, p. 129.

- ↑ Porphyrios, FGrH 260, fragment 32.17; Georgios Synkellos, World Chronicle p. 351 (Mosshammer); see Edwyn Robert Bevan: The House of Seleucus. 2 volumes, Edward Arnold, London 1902 (reprint, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1966), volume 2, p. 237, note 7 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ On the history of the Seleucid Empire from the death of Antiochus III. up to Antiochus VII. see for example the overview in Józef Wolski: The Seleucids. The Decline and Fall of their Empire. Nakł. Polskiej Akad. Umiejętności, Cracow 1999, ISBN 83-86110-36-8 , pp. 100-110.

- ↑ On the death of Antiochus VI. and on Diodoto's Tryphon see Kay Ehling: Studies on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, pp. 178-181.

- ↑ On Demetrios II's campaign, see Edward Dąbrowa : L'Expédition de Démétrios II Nicator contre les Parthes (139–138 avant J.-C.). In: Parthica. Volume 1, 1999, pp. 9-17 ( online ); on his captivity, see the same: Kings of Syria in captivity by the Parthians . In: Tyche . Volume 7, 1992, pp. 45-54, here pp. 46-50.

- ↑ Appian, Syriaca 68,358, see also 1 Makk 15.1 EU . Kay Ehling, on the other hand, concludes from the text passage Porphyrios, FGrH 260, fragment 32, 17 that Antiochus only went to Rhodes after he had received news of his brother's capture: Studies on the history of the late Seleucids (164-63 BC .). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, p. 186.

- ↑ Kay Ehling: Studies on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, p. 184 (coinage of Demetrios) and p. 186 (proclamation of Antiochus as king). Critically Ehling in 2001 published hypothesis of a conflict between the brothers before the capture of Demetrius' Expresses Peter Franz Lunch : By the beard of Demetrius. Reflections on the Parthian captivity of Demetrios II. In: Klio . Volume 84, number 2, 2002, pp. 373-399, here p. 378.

- ↑ 1 Makk 15.1–3 EU .

- ↑ 1 Makk 15.2-9 EU . For this document see Michael Tilly : 1 Maccabees (Herder's theological commentary on the Old Testament) . Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2015, ISBN 978-3-451-26822-9 , p. 290 f.

- ^ Hugo Willrich: On the coinage of the Maccabees. In: Journal of Old Testament Science and the Knowledge of Post-Biblical Judaism . Volume 51, 1933, p. 78 f.

- ↑ Baruch Kanael: Literature overviews of Greek numismatics: Old Jewish coins. In: Yearbook for Numismatics and Monetary History. Volume 17, 1967, pp. 157-298, here p. 166 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Jörg-Dieter Gauger : Contributions to Jewish Apologetics. Investigations into the authenticity of documents with Flavius Josephus and in the 1st Book of Maccabees (= Bonn Biblical Contributions. Volume 49). Hanstein, Cologne / Bonn 1977, ISBN 3-7756-1048-0 , p. 138 suspects a subsequent revision. Kay Ehling remains indifferent: Studies on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, pp. 186-188.

- ↑ Flavius Josephus , Jüdische Antiquities 13,222.

- ↑ Appian, Syriaca 68,360.

- ↑ Flavius Josephus, Jüdische Antiquities 13,222. See Kai Brodersen : Appian's Outline of the Seleucid History (Syriake 45,232–70,369). Text and comment. Editio Maris, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-925801-03-0 , p. 225.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer: To Tryphon. In: Chiron . Volume 2, 1972, pp. 201-213, here p. 211 f. (Date of arrival mid-138); Kay Ehling: Studies on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, p. 188 f. (Date of arrival to spring and marriage to September at the latest).

- ↑ 1 Makk 15.10 EU ; Flavius Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 13,223.

- ↑ 1 Makk 15.11-14 EU ; 1 Makk 15.25 EU ; Flavius Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 13,223.

- ↑ Bezalel Bar-Kochva: The Seleucid Army. Organization and Tactics in the Great Campaigns. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1976, pp. 7-19 (military history classification); Michael Tilly: 1 Maccabees (Herder's theological commentary on the Old Testament) . Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2015, ISBN 978-3-451-26822-9 , p. 293 (possible reason for the exaggeration).

- ↑ Dov Gera: Tryphon's Sling Bullet from Dor. In: Israel Exploration Journal . Volume 35, Number 2/3, 1985, pp. 153-163. The German translation of the inscription slightly modified after Kay Ehling: Investigations on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, p. 190; Thomas Fischer reads differently: Tryphon's failed victory by Dor? In: Journal of Papyrology and Epigraphy . Volume 93, 1992, pp. 29-30: Τρύφωνο [ς] Νίκη / Διὸς Δωρίτου γεῦσαι “Tryphon's victory! / Taste Zeus von Dor! ”.

- ↑ 1 Makk 15.37 EU (escape by ship via Orthosia); Charax of Pergamon , FGrH 103, fragment 29 (escape via Ptolemais); Georgios Synkellos , World Chronicle p. 351 (Mosshammer) (Escape via Orthosia); Flavius Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 13,224 (Escape to Apamea).

- ↑ Frontinus, stratagems 2,13,2.

- ↑ On the dating of death: Dov Gera: Tryphon's Sling Bullet from Dor. In: Israel Exploration Journal. Volume 35, number 2/3, 1985, pp. 153-163, here p. 160; Kay Ehling: Studies on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, p. 191.

- ↑ Flavius Josephus, Jüdische Antiquities 13,224; Appian, Syriaca 68,358; John of Antioch, Chronicle , fragment 96 (Mariev); Strabon, geography 14,5,2; Georgios Synkellos, World Chronicle p. 351 (Mosshammer). For the different variants see Kay Ehling: Two 'Seleucid' miscells. In: Historia. Volume 50, number 3, 2001, pp. 374-378, here p. 376.

- ↑ Porphyrios, FGrH 260, fragment 32.20; Appian, Syriaca 68,361. Kay Ehling: The succession plan of Antiochus VII before his departure into the Parthian War (131 BC) . In: Yearbook for Numismatics and Monetary History , Volume 46, 1996, pp. 31–37 ( PDF ), especially pp. 35 and 37.

- ↑ Edouard Will: Histoire politique du monde hellénistique (323-30 av. J.-C.). Volume 2, Presses universitaires de Nancy, Nancy 1967, p. 346.

- ↑ For a detailed explanation of Thérèse Liebmann-Frankfort: La frontière orientale dans la politique extérieure de la République romaine depuis le traité d'Apamée jusquà la fin des conquêtes asiatiques de Pompée (189 / 8-63). Académie Royale de Belgique, Brussels 1969, pp. 129-132. The legation trip is documented in Diodorus , Bibliotheca historica 33, 28b, 3; for the dating of the embassy see Harold B. Mattingly : Scipio Aemilianus' Eastern Embassy. In: The Classical Quarterly. Volume 36, 1986, pp. 491-495, and the same: Scipio Aemilianus' Eastern Embassy - the Rhodian Evidence. In: Acta Classica. Volume 39, 1996, pp. 67-76, of the trip - not generally accepted - in the year 144/143 BC. Dated; he joined for example: Tom Stevenson: Scipio Aemilianus (Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus Africanus Numantinus). In: Roger S. Bagnall , Kai Brodersen , Craige B. Champion, Andrew Erskine, Sabine Hübner (Eds.): The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford 2012, ISBN 978-1-4051-7935-5 , pp. 6076-6078 ( online ).

- ↑ Kay Ehling: Problems of the Seleucid Chronology and History of the Years between 139 and 131 BC Chr. In: Ulrike Peter (ed.): Stephanos nomismatikos. Edith Schönert-Geiss on her 65th birthday. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1998, pp. 227–241, here p. 227.

- ^ Titus Livius, Periochae 57. On this point also Edwyn Robert Bevan: The House of Seleucus. 2 volumes, Edward Arnold, London 1902 (reprint, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1966), volume 2, p. 241 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ 1 Makk 15.15-24 EU . See Thomas Fischer: Investigations into the Parthian War of Antiochus VII in the context of the Seleucid history. Dissertation, Munich 1970, p. 85 and p. 96–101 as well as the commentary on this point in: Michael Tilly: 1 Maccabees (Herder's theological commentary on the Old Testament) . Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2015, ISBN 978-3-451-26822-9 , p. 293.

- ↑ Kay Ehling: Studies on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, p. 192.

- ^ Christian Habicht : Athens and the Seleucids. In: Chiron. Volume 19, 1989, pp. 7-26, cited on p. 24.

- ↑ On this decree see Steven V. Tracy: IG II² 937: Athens and the Seleucids. In: Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies. Volume 29, Number 4, 1988, pp. 383-388; Christian Habicht: Athens and the Seleucids. In: Chiron. Volume 19, 1989, pp. 7-26, here pp. 22-24 ( PDF ).

- ^ Christian Habicht: Athens and the Seleucids. In: Chiron. Volume 19, 1989, pp. 7-26, here pp. 20 f. and p. 24.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer: Silver from David's tomb? Jewish and Hellenistic things on coins of the Seleucid king Antiochus VII. 132–130 BC Chr. Brockmeyer, Bochum 1983, ISBN 3-88339-325-8 , p. 13 and p. 36 with note 13.

- ↑ Justin, Epitoma historiarum Philippicarum 38,10,1. Translation after: Pompeius Trogus: World history from the beginnings to Augustus in the excerpt of Justin. Edited and translated by Otto Seel. Artemis, Zurich 1972, p. 425.

- ↑ Auguste Bouché-Leclercq : Histoire des Séleucides (323-64 avant J.-C.). Volume 1, Leroux, Paris 1913-1914, p. 370 f.

- ^ Justin, Epitoma historiarum Philippicarum 36,1,9.

- ^ Henri Seyrig : Notes on Syrian coins (= Numismatic notes and monographs. Volume 119). American Numismatic Society, New York 1950, pp. 17-19; Dov Gera: Tryphon's Sling Bullet from Dor. In: Israel Exploration Journal. Volume 35, number 2/3, pp. 153-163, here p. 160; Arthur Houghton , Catharine Lorber, Oliver Hoover: Seleucid Coins. A Comprehensive Catalog. Part 2: Seleucus IV through Antiochus XIII. 2 volumes, New York 2008, volume 1, p. 351.

- ^ Ulrich Wilcken: A contribution to the history of the Seleucids. In: Hermes . Volume 29, 1894, pp. 436-450, here p. 442 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Thomas Fischer: On a Seleucid coin of Antiochus VII. In: Revue Numismatique. 6th Series, Volume 9, 1967, pp. 239-241 ( online ). For the coins dealt with there see also Arnold Spaer: Monnaies de Bronze Palestiniennes d'Antiochos VII. In: Revue Numismatique. 6th series, Volume 13, 1971, pp. 160 f. ( online ).

- ↑ Johannes Malalas, Weltchronik 8:26; for use in coinage Arthur Houghton, Catharine Lorber, Oliver Hoover: Seleucid Coins. A Comprehensive Catalog. Part 2: Seleucus IV through Antiochus XIII. 2 volumes, American Numismatic Society, New York 2008, Volume 1, p. 354; on the statement behind it Thomas Fischer: On a Seleucid coin of Antiochus VII. In: Revue Numismatique. 6. Series, Volume 9, 1967, pp. 239-241, here p. 240.

- ↑ Flavius Josephus, Jüdische Antiquities 13,244 ("Eusebes"); ibid 13,222 ("Soter").

- ↑ Thomas Fischer: Investigations into the Parthian War Antiochus VII. In the context of the Seleucid history. Dissertation, Munich 1970, pp. 102-109.

- ↑ Justin, Epitoma historiarum Philippicarum , prologue to Book 39; John of Antioch, Chronicle , fragment 96 (Mariev); Porphyrios, FGrH 260, fragment 32.17; Georgios Synkellos, World Chronicle p. 351 (Mosshammer).

- ↑ Justin, Epitoma historiarum Philippicarum 38,10,6; Pierre Roussel , Marcel Launey: Inscriptions de Délos. Décrets postérieurs à 166 av. J.-C. (N os 1497–1524), Dédicaces postérieures à 166 av. J.-C. (N os 1525-2219). Boccard, Paris 1937, no.1547 ( text of the inscription online ) and no.1548 ( text of the inscription online ).

- ↑ See, for example, Pierre Roussel, Marcel Launey: Inscriptions de Délos. Décrets postérieurs à 166 av. J.-C. (N os 1497–1524), Dédicaces postérieures à 166 av. J.-C. (N os 1525-2219). Boccard, Paris 1937, no.1540 ( text of the inscription online ) and no.1541 ( text of the inscription online ).

- ↑ To the epithet Megas in summary Kay Ehling: Studies on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, p. 67 and p. 203.

- ↑ Arthur Houghton, Catharine Lorber, Oliver Hoover: Seleucid Coins. A Comprehensive Catalog. Part 2: Seleucus IV through Antiochus XIII. 2 volumes, New York 2008, volume 1, p. 352 and p. 396 f .; Arthur Houghton: A victory coin and the Parthian Wars of Antiochus VII. In: Proceedings of the 10th International Congress of Numismatics / Actes du 10ème Congrès international de numismatique (= Publications de l'Association internationale des numismates professionels. Number 11). International Association of Professional Numismatists, London 1989, p. 65; Kay Ehling: Studies on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, p. 200.

- ↑ Kay Ehling: Studies on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, p. 78 f.

- ↑ Flavius Josephus, Jüdische Antiquities 13,224; 1 Makk 15.25-27 EU .

- ↑ Kay Ehling: Studies on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, p. 191.

- ↑ Kay Ehling: Studies on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, p. 192 f.

- ↑ 1 Makk 15.28-37 EU . On the literary embellishment of this passage Michael Tilly: 1 Maccabees (Herder's theological commentary on the Old Testament) . Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2015, ISBN 978-3-451-26822-9 , pp. 296–298. The episode is also mentioned in Georgios Synkellos, Weltchronik p. 346 (Mosshammer).

- ↑ 1 Makk 15.38-41 EU ; Flavius Josephus, Jewish antiquities 13,225; Flavius Josephus, Jewish War 1,2,2. For Kendebaios and the (otherwise not attested for the Seleucid Empire) office of the epistrategean see Hermann Bengtson : The strategy in the Hellenistic time. Volume 2 (= Munich contributions to papyrus research and ancient legal history. Volume 32). CH Beck, Munich 1944, pp. 178-181.

- ↑ 1 Makk 16.1–10 EU : Flavius Josephus, Jüdische Altertümer 13.226 f .; Flavius Josephus, Jewish War 1,2,2; Georgios Synkellos, World Chronicle p. 346 (Mosshammer). For the dating of the battle see Kay Ehling: Investigations on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, p. 194; on the literary design of the report in the Book of Maccabees Michael Tilly: 1 Maccabees (Herder's theological commentary on the Old Testament) . Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2015, ISBN 978-3-451-26822-9 , pp. 300–302.

- ↑ 1 Makk 16.11–24 EU : Flavius Josephus, Jüdische Altertümer 13.228–235; Flavius Josephus, Jewish War 1,2,3 f.

- ↑ Flavius Josephus, Jüdische Antiquities 13,236; Flavius Josephus, Jewish War 1,2,5; see also Édouard Will: Histoire politique du monde hellénistique (323–30 av. J.-C.). Volume 2, Presses universitaires de Nancy, Nancy 1967, p. 345.

- ↑ To date the siege in detail Kay Ehling: Investigations on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, pp. 195–197. For the gold stater with the Nike motif, see Arthur Houghton: A victory coin and the Parthian Wars of Antiochus VII. In: Proceedings of the 10th International Congress of Numismatics / Actes du 10ème Congrès international de numismatique (= Publications de l'Association internationale des numismates professional number 11). International Association of Professional Numismatists, London 1989, p. 65; see also the description and photograph of the coin on parthia.com .

- ↑ Flavius Josephus, Jüdische Antiquities 13,237; Kay Ehling: Studies on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, p. 196.

- ↑ Flavius Josephus, Jüdische Antiquities 13,236–239 (devastation of the landscape, establishment of the siege, defenses of the besieged).

- ↑ Flavius Josephus, Jüdische Altertümer 13,240–243 (treatment of those unable to fight, festival of tabernacles); Plutarch , Moralia 184 F.

- ↑ Diodor, Bibliotheca historica 34 / 35.1. On this passage see Kay Ehling: Investigations on the history of the late Seleucids (164–63 BC). From the death of Antiochus IV to the establishment of the province of Syria under Pompey. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, p. 198, who considers the report of anti-Jewish (or strictly Hellenistic) advisers to Antiochus to be unhistorical and an invention of Poseidonios as Diodor's source for literary reasons.

- ↑ Flavius Josephus, Jüdische Antiquities 13,243–247 (negotiations, peace agreement); Diodor, Bibliotheca historica 34 / 35,1,5. See Thomas Fischer: Investigations into the Parthian War of Antiochus VII in the context of the Seleucid history. Dissertation, Munich 1970, p. 70 f.

- ↑ Flavius Josephus, Jüdische Antiquities 13,249; Flavius Josephus, Jewish War 1,2,5; Georgios Synkellos, World Chronicle p. 348 (Mosshammer). See Thomas Fischer: Johannes Hyrkan I on tetradrachms Antiochus VII.? A contribution to the interpretation of the markings on Hellenistic coins. In: Journal of the German Palestine Association. Volume 91, number 2, 1975, pp. 191-196, here pp. 195 f.