Basque language

| Basque (Euskara) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

Spain , France | |

| speaker | approx. 751,500 to 1,185,500 (native speakers) | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

eu |

|

| ISO 639 -2 | ( B ) baq | ( T ) eus |

| ISO 639-3 | ||

The Basque language - its own name Euskara (dialectal also euskera, eskuara, üskara ) - is spoken in the Basque Country (Euskal Herria), the Spanish - French border region on the Atlantic coast ( Biscay ), by over 750,000 people, of which over 700,000 in Spain. The number of speakers outside the traditional language area is not insignificant, especially in Europe and America, so that a total of around 1.2 million people speak Basque.

Basque is not genetically related to any other known language, according to the vast majority of relevant research . It would therefore be a so-called isolated language , while all the other languages of Europe today belong to a larger family of languages : either the Indo-European , Uralic , Turkic languages or - like Maltese - the Semitic languages.

The name " Basque " comes from the Latin vascones , a name that is etymologically related to the root eusk- and was originally used for Celtiberian groups . The Basque name is Euskaldunak, derived from the language name Euskara (which actually means "Basque speaker").

For the current language policy in the Basque Country, see the article Basque Language Policy .

classification

Basque is now the only non-Indo-European language in western Europe and the only isolated language on the entire European continent. For this reason alone, it takes on a noticeable special role. In the western Pyrenees of Spain (in the autonomous communities of Basque Country and Navarre ) and France ( French Basque Country ) Basque was able to hold its own against various Indo-European languages , including Celtic , Latin and today's Romance languages. It is believed that Basque is the last surviving representative of an ancient European language class that was widespread in much of Western Europe before the advance of Indo-European. However, the Old Baskish or Vasconic - the ancient predecessor of the modern language - can hardly be regarded as a kind of old European common language, which is said to have been spread throughout southern, western and central Europe before Indo- Germanization . Certainly there were pre-Indo-European languages in these extensive areas , one or the other of which may have been related to the forerunner of today's Basque. But even the relationship to the pre-Indo-European languages Iberian and South Lusitan , which were previously widespread on the Iberian Peninsula , is questioned by most researchers.

Aquitaine , documented from antiquity, can be considered an early form of Basque (in southern France ), which has only come down to about 500 names of persons and gods on grave and dedicatory inscriptions written in Latin. Both the name and the few identifiable morphological particles are related to today's Basque language (e.g. Aquitanian nesca "water nymph", Basque neska "girl"; Aquitanian cison "man", Basque gizon "human being, man"; - en (n) Aquitaine and Basque genitive ending).

Basque ethnolinguistic data

Number of speakers, language status

Basque is spoken by around 700,000 people today, mainly in northeastern Spain and southwestern France. Reliable numbers of speakers for Basque outside the Basque Country are not available, but around 90,000 are likely to speak or at least understand the language in other parts of Europe and America, bringing the total number of speakers to nearly 800,000. ( Encyclopædia Britannica 1998 provides higher numbers, Ethnologue 2006 - based on censuses from 1991 - assumes a total of 650,000 speakers. The 1994 census showed around 618,000 native speakers. EUROSTAT, the EU's statistical yearbook , gives around 690,000 speakers for Spain in 1999, For France, the Instituto Cultural Vasco estimates 56,000 Basque speakers over the age of 15 in 1997.)

Almost all Basque speakers are bilingual or multilingual and also speak at least the national language of their respective country. In the Spanish Basque Country (in the narrower sense: Provinces of Guipúzcoa, Vizcaya and Álava), Basque has had the status of a regional official language since 1978 (for details see the article Basque Language Policy ), in Navarra it has been the co-official language in the predominantly Basque- speaking communities since 1986. In France, the French language alone has the status of an official (official) language throughout the national territory. Basque, like all other languages traditionally spoken in the various parts of the country, is a regional language of France and as such (not specifically mentioned) has constitutional status as a (protected) cultural asset (patrimoine de la France) since the constitutional amendment of 23 July 2008 . No concrete legal claim has (so far) been derived from this. The French language policy does not even before an official count of the speaker. Basque associations sometimes assume a higher number of speakers - up to two million - but no distinction is made between competent active speakers and passive speakers (people who understand Basque to a certain extent but cannot speak it competently). In Spain today around 4.5 million people have a Basque surname.

Geographical distribution

The language area is located on the coast in the southeast of the Bay of Biscay from Bilbao in Spain to Bayonne in France. Today it has an east-west extension of over 150 km, a north-south extension of less than 100 km and covers an area of about 10,000 km². In Spain these are the provinces of Guipúzcoa , parts of Vizcaya and Navarra , and the northern part of Álava . Basque speakers are mainly concentrated in the highly industrialized regions of this area. However, they have the highest proportion of the population in rural mountain valleys. Numerous Basque speakers also live in the major cities outside the closed Basque-speaking area, in particular the provincial capitals Vitoria-Gasteiz and Pamplona / Iruña as well as in Madrid . In France, Basque is spoken mainly in the French part of the Basque Country, the western part of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department with the historic Basque provinces of Labourd , Basse-Navarre and Soule . On the coast in the area of the populous urban centers (Bayonne / Baiona, which has been mostly French-speaking since the 19th century, and Biarritz ), the proportion of Basque speakers is also lower here than in the rural interior. Outside the Basque Country, there are larger numbers of speakers in the United States , Latin American countries, Australia , the Philippines and other parts of Europe.

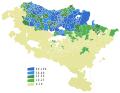

Language situation in the entire Basque Country - low proportions of Basque in the south (especially Navarre) and west as well as on the French coast

Distribution of Basque speakers in the Spanish Basque Country and Navarre in 2001

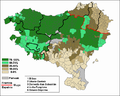

Autonomous Community of Navarre (Spain): Municipalities of the Basque-speaking, mixed and Spanish-speaking zones

Autonomous Community of Navarre (Spain): Share of Basque speakers by municipality

Dialects, Euskara Batua

Linguistics usually distinguishes seven main dialects of Basque:

- in Spain: the dialects of Bizkaia ( Biskayisch also Vizcainisch), Gipuzkoa (Gipuzkoanisch), Araba (Álava) (today †) and Nafarroa (Obernavarrisch)

- In France: the dialects of Lapurdi (Laburdinisch also Labourdisch), Nafarroa Beherea (Lower Navarre) and Zuberoa (Suletinisch, also Soulisch)

These dialects can be broken down into at least 25 subdialects. The dialects are divided according to the (former) provinces. The dialect differences are not very great, neighboring dialects are mutually easy to understand, the most eastern French dialect, the dialect of Zuberoa (Suletino), deviates most.

A distinction is made between three main groups: 1. Biscay, 2. Gipuzcoan, Labourdisch and Obernavarresisch, 3. Niederavarresisch and Soulisch. A division of the Basque dialects into three separate languages - Spanish Basque, Navarro-Labourdin and Souletin, as done by Ethnologue - does not correspond to the scientific literature despite the strong deviation of the Suletin dialect.

From the central dialect of Gipuzkoa and on the basis of previous standardization projects, the Basque Academy, under the direction of Koldo Mitxelena (Luís Michelena), has created a language and writing standard Euskara Batua (United Basque) since 1968 . Since 1980, more than 80% of all Basque publications - around 5000 titles, after all - have appeared in this standardized language, which is slowly beginning to establish itself as a spoken high-level language. (More details on this in the article Basque Language Policy .)

History of the Basque Language

The evolution of Basque

At the beginning of our era, Basque was demonstrably spoken north and south of the Pyrenees and in large parts of northern Spain. After Roman rule, the language area expanded further to the southwest into the province of Rioja Alta, an area within today's province of La Rioja . The easternmost Basque dialects ( Aquitaine ) were superseded by the Romance languages early on . In the Middle Ages, rural Basque without writing found it difficult to assert itself against the emerging Romance written and cultural languages (e.g. Aragonese and Occitan ). In the south, Basque has continuously lost ground to the advancing Castilian and Spanish since the 10th century .

Written tradition

Latin inscriptions, mostly from what is now southwestern France, preserve some clearly Basque personal names or names of gods ( Leherenno deo "the first god"). Since 1000 AD, Basque proper names, but also Basque formulas and short sentences, have been preserved more frequently. The first book in Basque was printed in 1545 (Linguae Vasconum Primitiae) . It was written by Jean (d ') Etxepare (Echepare), a priest from Niedernavarra, and contains a number of popular poems. This book was the beginning of an uninterrupted, but not particularly extensive literary tradition, which has mainly religious titles. The "Basque Revival or Renaissance Movement " ( Euskal pizkundea, 1887–1936) took the first concrete steps to standardize the written language on the basis of the central dialect of Gipuzkoa.

In 2005 and 2006, Basque inscriptions dated to the 4th century were found in Iruña-Veleia (province of Alava); H. to the time of the Christianization of the Basques. Its authenticity is controversial, but the finders defend it.

Civil War and Franco Period

Basque temporarily acquired the status of an official language for the Spanish Basque Country in 1936 after the adoption of the Basque Statute of Autonomy during the Second Spanish Republic . After the victory of the insurgents in the " War in the North " it lost this status again (1937). In the subsequent Franco dictatorship (1939–1975), the use of Basque was banned in the entire public sector, which caused the number of speakers to drop sharply over the years. It was not until 1975 that the restrictions were relaxed somewhat, so that schools with Basque as the language of instruction (ikastolak) and Basque courses for adults could also be set up. These institutions, which soon spread throughout the Basque Country, made the creation of a uniform written Basque language ever more urgent.

Standardization, regional official language

The establishment of the common writing and language standard Euskara Batua ('united Basque') was decisively promoted by the spelling definition by Koldo Mitxelena (also Luís Michelena) in 1968, but it has not yet been fully completed. The democratization of Spain since 1975 and in particular the constitution of 1978 , which granted Basque the status of a regional official language alongside Spanish in the provinces of Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa, Álava and parts of Navarre, created more favorable conditions for the stabilization and further development of the Basque language in Spain.

outlook

These favorable political circumstances, the strong roots of Basque in the Basque population and their strong ethnic and linguistic awareness certainly contribute significantly to the long-term survival of this extraordinary language, despite the fact that it has less than a million speakers.

Theories of origin

Proof of a genetic relationship between Basque and other languages is difficult for the following reasons:

- Larger written evidence is only available from the 15th or 16th century, so that older language levels can only be reconstructed with difficulty. Here, however, the old Basque toponymy (place name science) can help.

- Other old Iberian languages are only poorly known. It is therefore not possible to decide whether the few Basque-Old Iberian word equations that exist in small numbers are not due to borrowing or language contact (see “ Iberian hypothesis ”).

The most widespread hypothesis among serious researchers is that Basque is not related to any other language, i.e. is isolated. Nevertheless, there have been and are numerous attempts to genetically relate Basque to other languages and language families. Obviously, the isolation of Basque in the midst of Indo-European languages provided a special incentive to do so. R. P. G. Rijk (1992) describes the result of these efforts succinctly: "Despite all the ink that has been put on its genetic relationship over the past hundred years, the matter is still unclear."

Iberian hypothesis

Wilhelm von Humboldt and later Hugo Schuchardt already hypothesized that Basque and Iberian were related in the 19th century . Iberian - not to be confused with Celtiberian , a Celtic and thus Indo-European language - is a non-Indo-European language of pre- and early Roman Spain (6th to 1st century BC), which was initially sporadically translated into Greek , later in It was handed down to a greater extent in its own Iberian script, influenced by the Phoenicians and Greeks , on numerous inscriptions and coins in Spain, the Balearic Islands and southern France. Although the Iberian letter-syllable script was successfully deciphered (M. G. Moreno 1922–24), the Iberian texts were barely understandable. In particular - contrary to original expectations - Basque has not been helpful in any way to understand them, which alone makes a closer relationship between these two languages improbable. However, some researchers still support the Basque-Iberian hypothesis while the majority now reject it. Some Iberian-Basque word equations (e.g. with Basque bizkar “rock face”, argi “bright”, ilun “dark”, iri / ili “city”) can also be explained by the close contact of Old Baskish with Iberian.

African hypothesis

Others see a connection between Basque and African languages . The Berber languages , a subgroup of the Afro-Asian languages , the Songhai languages , whose own classification is controversial, and the group of Mande languages , which belong to the Niger-Congo languages , were named. None of these hypotheses could prevail; In terms of language typology , they are extremely questionable.

Caucasian hypothesis

These hypotheses were also soon superseded by the Basque-Caucasian thesis, which linked Basque with the Caucasus languages as a whole or with a subset of them. The Caucasian languages are the long-established languages of the Caucasus , which are neither Indo-European, nor Turkish, nor Semitic . The Caucasologist Georgij A. Klimov critically examined various authors of the Basque-Caucasian thesis and came to a complete rejection (Klimov 1994).

Klimov's main reasons for rejecting a relationship between Basque and Caucasian languages are:

- The different genetic units of the Caucasian (which is divided into at least three different language families ) are not taken into account when comparing languages.

- Basque is compared with some of the 40 modern Caucasian languages as required, instead of using reconstructed proto- Caucasian languages .

- Phonetic laws between the Basque and Caucasian units are seldom established.

- The reasoning is generally strongly typological , which means that it has no genetic evidence.

- Semantic anachronisms are used (for example, iron processing words are used for comparison, although Basque and Caucasus languages must have separated at least 5000 years ago; there was no iron processing at that time).

- Indo-European loanwords are included in the comparison.

Klimov's conclusion: “The Basque-Caucasian thesis is nowadays only upheld by journalists or linguists who are not familiar with the facts of Basque or the Caucasian languages” (Klimov 1994).

Dene-Caucasian hypothesis

Edward Sapir introduced the designation Na Dené languages in 1915 . In addition, there are other approaches to connect the Na-Dené language family with the Eurasian languages, such as Sinotibetic and Yenisian . On the basis of linguistic analyzes, a genetic relationship of different language families, constituted in a hypothetical macro family, the Dene-Caucasian , was established, in this language family there are some languages from Eurasia and North America. The main members are Sino-Tibetan, the North Caucasian languages and Basque. After Vitaly Shevoroshkin also "Dene-Sino-Caucasian Languages".

The latest attempts aim to establish Basque as a member of a hypothetical European-Asian-North American macro family , the so-called Dene-Caucasian . This macro family essentially goes back to Sergei Starostin 1984; the addition of Basque was suggested by Vyacheslav Tschirikba (* 1959) in 1985 , among others . According to this thesis, Basque would be related to North Caucasian , Sino-Tibetan and the Na-Dené languages of North America.

Eurasian hypothesis

The French linguist Michel Morvan has considered a “Euro-Siberian” substrate for Basque and sees parallels with Siberian languages and cultures, but also with other pre-Indo-European languages. He tries to prove a Eurasian relationship (Etymological Dictionary, Online / Internet /).

Vasconic hypothesis

The Munich linguist Theo Vennemann hypothesizes that a forerunner of Basque called Vaskonian was once widespread in large parts of Western and Central Europe. According to his name (see " Onomastics ") and hydrological (see " Hydronymy ") interpretations, he sees correspondences of word cores of many river and place names in Western and Central Europe with Basque words for water, river, water, valley and the like. a. Many researchers, including bascologists, have rejected this approach because it can hardly be proven.

Interrelationships with neighboring languages

Phonology

Two neighboring Romance languages, namely Spanish and even more strongly the southwest Occitan regional language Gaskognisch , show a reduction of the Latin f to h , which is now silent in the standard Spanish language. This phenomenon is attributed to the influence of Basque, for comparison the Spanish place name Fuenterrabia, Basque Hondarribia, High Aragon Ongotituero .

- lat. filia → French fille , Occitan . filha | Spanish hija , gas cognitive hilha 'daughter'

- lat. farina → French farine , occ. farina | span. harina , gas. haría 'flour'

- lat. flos / pile → French. fleur , span./okz. flor | gas. hlor 'flower'

- lat. frigidus → Spanish. frío , French. froid , occ. freg , fred | gas. hred 'cold'

- Vulgar Latin calefare → French chauffer , Catalan . calfar , occ . caufar | gas. cauhar 'heating'

Other influences are the distinction between two r sounds in Basque and Spanish and the prosthetic scion vowel before the original r .

- lat. rota → Spanish rueda, French roue, Occitan ròda | Basque Errota, Gascon arroda , wheel '

The whole of Gascony is regarded as a former Basque language area, which is already evident from the name (Vascones> Wascons> Gascons). In Spain, the toponomy points to a previously far more extensive distribution area, e.g. B. Val d'Aran (Basque aran 'valley').

Lexical borrowing

Basque has retained a striking independence not only in its morphology , but also in its vocabulary , despite at least 2500 years of pressure from the surrounding Indo-European languages. Nevertheless, in the course of its history it has integrated loan words mainly from the Latin - Romance languages. Some examples are:

- bake 'peace' → Latin pax, pacis

- dorre 'tower' → Latin turris

- eliza 'church' → Latin ecclesia

- excite 'king' → lat. rex, regis

- errota 'wheel' → Latin rota

- gaztelu 'fort' → Latin castellum

- katu 'cat' → Latin cattus

- put 'law' → Latin lex, legis

- liburu 'book' → Latin liber, vulgar lat . librum

Another important layer of loanwords comes from Celtic such as B.

- adar 'horn' → kelt. adarcos (unsure)

- hartz 'bear' → kelt. artos

- lekeda 'sediment' → kelt. legita

- maite 'loved' → kelt. matis 'good' (unsure)

- mando 'mule' → kelt. mandus 'little horse'

- tegi 'house' → kelt. tegos (unsure)

- tusuri ' devilry ' → kelt. dusios 'devil'

Although Basque has numerous opportunities to create new words through derivatives , the English and Romance words of modern technology are now widely used as foreign words in Basque. Conversely, very few Basque words have been borrowed into the surrounding Romance languages; however, Basque surnames and place names have found widespread use in Spain and Latin America (e.g. Bolívar , Echeverría and Guevara ). Possible loanwords of Basque origin in Romance languages are:

- span. becerro 'one year old calf', to aspan. bezerro → bask. bet - 'cow' ( word form of behi ) + - irru .

- Spanish bizarro , bold, lively, brave '→ bask. bizarre 'beard'.

- Spanish cachorro ' little dog', southern Corsican ghjacaru 'hunting dog', Sardinian giagaru → bask. txakur 'puppy'.

- span. cencerro 'cow bell' → bask. zintzarri, zintzerri .

- port. esquerdo, Spanish. izquierda, cat. esquerre 'left', occ. esquèr (ra) 'link' → bask. ezkerra 'Linke', formed into ezker 'link'.

- Spanish madroño, arag . martuel, cat. maduixa 'strawberry tree' → bask. martotx 'blackberry bush', martuts ~ martuza 'blackberry'.

- port. pestana, span. pestaña, cat. pestanya 'eyelash' → * pistanna → urbaskisch * pist -, from which basque. pizta ' eye butter ' and piztule 'eyelash'.

- port. sarça, span. zarza , blackberry bush ', in old Spanish çarça → old baskish çarzi (17th century), of which basque. sasi 'thorn bush' and sarri 'bushes, thickets'.

- port. veiga, Spanish vega 'floodplain, fertile plain', in old Spanish vayca → bask. ibai 'river' + - ko (separative ending ; diminutive suffix ).

Language structure

Basque is typologically completely different from today's neighboring Romance and all Indo-European languages: it has a suffix -declination (like agglutinating languages , e.g. the Urals and Turkic languages), no grammatical gender and an extremely complex verbal system with the Marking of one or up to four people in every finite verbal form (polypersonal inflection). The marking of the nominal inflection (declination) takes place at the end of a word group ( syntagma ). In contrast to most Indo-European languages - which obey a nominative / accusative system - Basque is an absolute / ergative language (see below).

According to the system

alphabet

The Basque alphabet , which is based on the Latin alphabet , has the following 27 letters and 7 digraphs :

| Letter | Surname | Pronunciation according to IPA |

comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Letters | |||

| A, a | a | / a / | |

| B, b | be | / b /, [β̞] | |

| C, c | ze | / s /, / k / | Is only used in foreign or loan words. |

| Ç, ç | ze hautsia | / s / | Does not count as a separate letter, but as a variant of the C, and is only used in foreign or loan words. |

| D, d | de | / d̪ /, [ð̞] | |

| E, e | e | / e / | |

| F, f | efe | / f / | |

| G, g | ge | / ɡ /, [ɣ̞] | |

| H, h | hatxe | / ɦ / or mute | |

| I, i | i | / i /, / i̭ / | |

| J, j | iota | / y / | Also pronounced in dialectal terms / ʝ /, / ɟ /, / dʒ /, / ʒ /, / ʃ / or / χ / |

| K, k | ka | / k / | |

| L, l | ele | / l / | |

| M, m | eme | / m / | |

| N, m | ene | / n / | |

| Ñ, ñ | eñe | / ɲ / | |

| O, o | O | / o / | |

| P, p | pe | / p / | |

| Q, q | ku | / k / | Is only used in foreign or loan words. |

| R, r | achieve | / r /, / ɾ / | |

| S, s | ese | / s̺ / or / ɕ / | |

| T, t | te | / t̪ / | |

| U, u | u | / u /, / u̯ / | |

| Ü, ü | ü | / y / | Dialectal variant of the U, is not counted as a separate letter. |

| V, v | uve | / b /, [β̞] | Is only used in foreign or loan words. |

| W, w | uve bikoitza | / u̯ / | Is only used in foreign or loan words. |

| X, x | ixa | / ʃ / | |

| Y, y | i grekoa | / i /, / i̭ /, / j / | Is only used in foreign or loan words. |

| Z, z | zeta | / s̻ / | |

| Digraphs | |||

| DD, dd | / ɟ / | ||

| LL, ll | / ʎ / | ||

| RR, rr | / r / | ||

| TS, ts | / t͡s̺ / | ||

| Dd, dd | / c / | ||

| TX, tx | / t͡ʃ / | ||

| TZ, tz | / t͡s̻ / | ||

Vowels

The vowel system has three levels and does not distinguish between vowel quantities . Basque has five vowels and ten diphthongs . The vowels are a [a], e [e], i [i], o [o] and u [u]. Depending on the environment , e and i can be pronounced more openly or more closed. In addition, there is the sound ü [y] in the Suletin dialect . It is a matter of dispute among linguists whether it is to be regarded only as a pronunciation variant of the u or as an independent phoneme . There are two groups of diphthongs. The decreasing diphthongs start with an open vowel and end with a closed one: ai, ei, oi, au, eu . In the ascending diphthongs, a closed vowel is followed by an open one: ia, ie, io, ua, ue . The most common vowel letter combination, the "ai", often does not mark a diphthong, but the i contained therein palatalizes the following consonant , example baina [baɲa].

Consonants

Special features of the Basque consonant system are the two s sounds and the five palatal sounds.

The letter z represents an unvoiced [s] with the tip of the tongue on the lower tooth wall, as in the German, French or English pronunciation of the letter s . In the case of the Basque sound [ɕ] represented with s , the tip of the tongue is on the other hand at the upper tooth wall, similar to the pronunciation of the sound, which is represented in European Spanish with the letter s .

The palatals include: voiceless [c] (between German “z” and “tsch”), written as tt or -it-, plus the voiced [ɟ] (between “ds” and “dj”), written as dd or -id-, das [ɲ] (between German “n” and “j”), written ñ or in, das [ʎ] (between German “l” and “j”), written ll or il, and the [ʃ ], represented in Basque with the letter x . The pronunciation is similar to German “sch”, but fluctuates between ch and dsch .

| labial | dental |

apico- alveol. |

dorso- alveol. |

postalv. | palatal | velar | glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Occlusive voiceless |

p | t | ʦ (tz) | ʨ (ts) | ʧ (tx) | ( c ) (tt) | k | - |

|

Occlusive voiced |

b | d | - | - | - | ( ɟ ) (dd) | G | - |

| Fricatives | ( f ) | - | s (z) | ɕ (s) | ʃ (x) | - | x / ʤ (j) | H |

| Nasals | m | n | - | - | - | ( ɲ ) (ñ) | - | - |

| Vibrants | - | - | - | r (rr) | - | - | - | - |

| Taps / flaps | - | - | - | ɾ (r) | - | - | - | - |

| Lateral | - | - | - | l | - | ʎ (ll) | - | - |

The sounds are given in the IPA form, followed by the written realizations of the Basque orthography in brackets , if they differ from the IPA form. Phonemes in parentheses do not have a complete phoneme status, so [f] only occurs in loan words, [c] and [ɟ] occur especially in pet forms. Even if [h] is not articulated on the surface by many speakers, it is systematically a Basque phoneme.

The difference between ts and tz is phonemic, like the example pair

- atzo "yesterday"

- atso "old"

occupied.

The pronunciation of voiceless plosives is more aspirated than in the Romance languages.

Word order

Some basic word order:

- Subject - object - verb (position of the clauses in the sentence)

- explanatory genitive noun

- Noun - related adjective

- Possessive pronouns - nouns

- Noun - post position

- Numeral - counted noun

Ergative language

Basque is an ergative language , which means that there is a special case for the subject of a transitive verb, the ergative , while the absolute is used for the subject of intransitive verbs . This absolute also serves as a direct (accusative) object of transitive verbs. In Basque, the ergative is identified by the suffix / - (e) k /, the absolute remains unmarked, it represents the basic form of the noun.

- Jon dator > John is coming (intransitive, Jon in the absolute)

- Jonek ardoa dakar > John brings wine (ardo) (transitive, Jon in the ergative, ardo in the absolute)

- Oinak zerbitzatzen du eskua eta eskuak oina > The foot (oina) operates the hand (eskua) and the hand the foot.

Nominal morphology

There are two perspectives here:

1. Transnumeral

In this representation, the noun has a numerus-free basic form ( transnumeral ), a singular and a plural form. In the absolute (see above) the forms are as follows:

| number | shape | translation |

|---|---|---|

| Absolutely transnumeral | katu | cat |

| Absolutely singulative | katu- a | the cat |

| Absolutely plural | katu- ak | the cats |

The number-free basic form (transnumeral) is about abstracting from the number.

2. Definiteness suffix

Some linguists prefer an alternative view. They describe the endless form katu as "indefinite" (not distinguished by any feature) and the morpheme -a as a "definiteness suffix", which is appended to the indefinite form in any characterization. One can see, however, that Basque, even if the indefiniteness is restricted by a partial characterization (“specific indefinite”) of a noun, prescribes a suffix such as the example sentence Garfield katua da (“Garfield is a (and a very specific!) Cat ”) shows.

Case formation

Basque forms the case of a noun by adding suffixes , which, however, do not have to follow the noun immediately, but are always added to the last element of a noun group. The suffixes of the declension are preserved in their pure form in proper names and transnumeral forms. The singular suffixes are formed by adding the marker / -a (-) /, the plurals usually by removing the prefix / -r- /. A genus (grammatical gender) does not know the Basque. The following table gives an overview of the regular declination in Basque.

The cases and their corresponding suffixes:

| case | Inanimate | Animated | meaning | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transnumeral | Singular |

Plural |

Transnumeral | Singular |

Plural | ||

| Absolutely | - | -a | -ak | like inanimate | (see above) | ||

| Ergative | - ([r] e) k | -ak | -ek | (see above) | |||

| dative | - (r) i | -ari | -egg | For | |||

| Genitive | - (r) en | -aren | -en | possessive genitive | |||

| Benefactive | - (r) rentzat | -arentzat | -entzat | In favor of | |||

| Comitative | - (r) ekin | -arekin | -kin | along with | |||

| Motivational | - ([r] e) ngatik | -a (ren) gatik | -engatik | because of | |||

| Instrumental | - (e) z, - (e) taz | -az | -ez | by means of | |||

| Inessive |

- ([r] e) tan - ([r] e) n (for proper names) |

- (e) on | - done |

- (r) engan - ([r] en) gan (for proper names) |

-a (ren) gan | - tight | in / at |

| Allative |

- (e) tara - ([r] e) ra (for proper names) |

- (e) ra | -etara |

- (r) engana - ([r] en) gana (for proper names) |

-a (ren) gana | -engana | towards |

| ablative |

- (e) tatik - ([r] e) tik (for proper names) |

- (e) tik | -atatik |

- (r) engandik - ([r] en) gandik (for proper names) |

-a (ren) gandik | -engandik | From through |

| Directive |

- ([e] ta) rantz - ([r] e) rantz (for proper names) |

- (e) rantz | -etarantz | - ([r] en) completely | -a (ren) completely | -enganantz | in the direction |

| Terminative |

- ([e] ta) taraino - ([r] e) raino (for proper names) |

- (e) raino | -etaraino |

- (r) enganaino - ([r] en) ganaino (for proper names) |

-a (ren) ganaino | -enganaino | up to |

| Separately |

- (e) tako - ([r] e) ko (for proper names) |

- (e) ko | -etako | - | from / her | ||

| Prolative | -tzat | - | - | -tzat | - | - | hold for / view as |

| Partitive | - (r) ik | - | - | - (r) ik | - | - | any / none |

The declination of nouns ending in a consonant differs only slightly: the suffix-introducing / -r / is omitted in the transnumeral forms, a / -e- / is inserted in front of some suffixes.

Personal pronouns

The declension of the personal pronouns follows the same scheme:

| case | I | you | he she | we | she | her | she (plural) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolutely | ni | Hi | hura | gu | to | zuek | haiek |

| Ergative | nik | hik | hark | guk | zuk | zuek | haiek |

| dative | niri | hiri | hari | guri | zuri | zuei | shark egg |

| Genitive | nire | hire | hair | gure | to be sure | zuen | sharks |

| Benefactive | niretzat | hiretzat | harentzat | guretzat | available | zuentzat | haientzat |

| Comitative | nirekin | hirekin | harekin | gurekin | zuurekin | zuekin | haiekin |

| Instrumental | nitaz | hitaz | hartaz | gutaz | additionally | zuetaz | haietaz |

Noun phrases

The case endings are only appended to the last term in a noun phrase made up of several terms. The preceding terms are not declined. Attributive adjectives come after the associated noun, bat ('a') has the function of an indefinite article and is at the end of the noun phrase.

| Basque | German |

|---|---|

| asto txuri asked | a white (txuri) donkey (asto) |

| katu beltz batengatik | because of a black (beltz) cat (katu) |

| etxe ederra | the beautiful (eder) house (etxe) |

| gure ahuntz politak | our (gure) beautiful (polit) goats (xahuntzx) |

| zahagi berrietan | in the new (berri) (wine) tubes (zahagi) |

Numerals

Basque shows a clear vigesimal system (twenties system), e.g. B. 40 = 2 × 20, 60 = 3 × 20, 80 = 4 × 20, 90 = 4 × 20 + 10. However, there is also a vigesimal system in other European languages: in the Caucasian languages, in the Celtic languages Breton , Irish , Scottish Gaelic (optional there) and Welsh , in Danish and in remnants in French (70 = soixante-dix, 80 = quatre-vingts, 90 = quatre-vingt-dix ).

| 1 | asked | 11 | hamaica | 30th | hogeita hamar |

| 2 | bi | 12 | hamabi | 40 | berrogei |

| 3 | hiru | 13 | hamahiru | 50 | berrogeita hamar |

| 4th | lukewarm | 14th | hamalau | 60 | hirurogei |

| 5 | bost | 15th | hamabost | 70 | hirurogeita hamar |

| 6th | be | 16 | hamasei | 80 | laurogei |

| 7th | zazpi | 17th | hamazazpi | 90 | laurogeita hamar |

| 8th | zortzi | 18th | hemezortzi | 100 | ehun |

| 9 | bederatzi | 19th | hemeretzi | ||

| 10 | hamar | 20th | hogei |

Verbal morphology

While the inflection of the noun in Basque is quite clear despite the many cases, the verb morphology is downright notorious for its extraordinarily diverse and complicated forms. Eighteenth-century grammarians counted no fewer than 30,952 forms of a single verb. This has the following cause: the forms of the finite verb in Basque contain not only a reference to the respective person of the acting subject (this is the normal case in Indo-European languages: I love-e, you love-st, he loves-t etc. ), but also on the person of the direct and indirect object of the action and sometimes even the person of the person addressed.

Here are some forms of the present tense of the verb ukan ' to have' (3sg = 3rd person singular etc.):

| Basque | translation | subject | direct object |

indirect object |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| you | he / she has it | 3sg | 3sg | - |

| gaitu | he / she has us | 3sg | 1pl | - |

| zaitugu | we have them | 1pl | 2sg | - |

| diot | I have it for him / her | 1sg | 3sg | 3sg |

| dizut | i have it for you | 1sg | 3sg | 2sg |

| dizkizut | i have it for you | 1sg | 3pl | 2sg |

| dizkigute | they have it for us | 3pl | 3pl | 1pl |

One recognizes immediately the abundance of forms this triple marking of the verbal forms must lead to. A clear representation of the paradigm would have to be three-dimensional.

The simple conjugation

Basque differentiates between a so-called simple (or synthetic ) conjugation, in which the forms are formed directly from the verb itself (such as the German present tense 'he loves') and a compound ( analytical or periphrastic ) conjugation with auxiliary verbs (such as e.g. the German perfect 'I have loved').

The so-called simple conjugation is only used for a small group of commonly used verbs. The verbs izan 'be', ukan 'have', egon 'be', etorri 'come', joan '(purposefully) go', ibili 'go around', eduki 'have, hold', jakin 'know', are simply conjugated . esan 'say'. In the literary Basque language, a few other verbs are simply conjugated, such as ekarri 'bring', erabili 'use', eraman 'wear', etzan 'lie', iraun 'last'. The proportion of so-called simple verbs was greater in earlier language phases; texts from the 16th century contain around fifty. Today they are used as a means of upscale style . All other verbs are conjugated periphrastically (i.e. with auxiliary verbs). The simple conjugation now only has two tenses - present and past tense - and one imperative .

Example: Present tense from the verb ekarri 'bring' with some variants of the subject and direct and indirect object (3sg = 3rd person singular etc.):

| Basque | translation | subject | direct object |

indirect object |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dakart | I'll bring it | 1sg | 3sg | - |

| dakarna | you (female) bring it | 2sg | 3sg | - |

| dakark | you (male) bring it | 2sg | 3sg | - |

| dakar | he / she brings it | 3sg | 3sg | - |

| darkarte | they bring it | 3pl | 3sg | - |

| dakartza | he / she brings them | 3sg | 3pl | - |

| nakar | he / she brings me | 3sg | 1sg | - |

| hakar | he / she brings you | 3sg | 2sg | - |

| dakarkiote | they bring it to him / her | 3pl | 3sg | 3sg |

| dakarzkiote | they bring them to him / her | 3pl | 3pl | 3sg |

The following table shows a complete scheme of the present tense of the frequently used auxiliary verb ukan 'haben' with a fixed direct object in the 3rd Sg. ' Es ' and a variable dative object:

| subject | Person of the indirect object | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| without | 1sg (me) |

2sg (you female) |

2sg (you male) |

3sg (him her) |

1pl (us) |

2sg (Them) |

2pl (to you) |

3pl (them) |

|

| 1sg (I) |

dut | - | dinat | diet | diot | - | dizut | dizuet | diet |

| 2sg (you female) |

dun | didan | - | - | dion | digun | - | - | serve |

| 2sg (you male) |

duk | didak | - | - | diok | diguk | - | - | diek |

| 3sg (he she) |

you | dit | din | dik | dio | digu | dizu | dizue | the |

| 1pl (we) |

dugu | - | dinagu | diagu | diogu | - | dizugu | dizuegu | diegu |

| 2sg (She) |

duzu | did this | - | - | diozu | diguzu | - | - | the to |

| 2pl (her) |

duzue | didazue | - | - | diozue | diguzue | - | - | die to |

| 3pl (she) |

dute | didate | dinate | diet | diote | digute | dizute | dizuete | diete |

For example diguzue means “you have it for us” (subject 2.pl., indirect object 1.pl., direct object 3.sg. “it”). The corresponding forms for a direct object in the 3rd person. Plural be in the shapes with respect dative by insertion from / -zki- / di- / generated behind the first syllable / z. B. di zki ot "I have it (pl.) For him / her (sg.)", But diot "I have it for him / her (sg.)".

One recognizes that reflexive forms (e.g. 'I have myself') do not exist in this scheme. They have to be formed by paraphrasing.

The compound conjugation

The forms of compound or periphrastic conjugation, after which all other, non-simple verbs are conjugated, are formed from one of the root forms of the verb together with a form of the auxiliary verbs izan, ukan, edin or ezan . Root forms are the stem of the verb itself, the past participle , the future participle and the gerund (actually a verbal noun in the inessive ). Here ukan and ezan are used for transitive verbs , izan and edin for intransitive verbs. Further details should not be given here (see references).

Language example

As a language example, Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is mentioned:

“ Gizon-emakume guztiak aske jaiotzen dira, duintasun eta eskubide berberak dituztela; eta ezaguera eta kontzientzia dutenez gero, elkarren artean senide legez jokatu beharra dute. "

“All people are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should meet one another in a spirit of brotherhood. "

See also

literature

Lexicons

- Elena Martínez Rubio: Dictionary German – Basque / Basque – German. 2nd (corrected) edition, Buske, Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-87548-493-9 .

- Manuel Agud, A. Tovar: Diccionario etimológico vasco . Gipuzkaoko Foru Aldundia, Donostia-San Sebastián (1989, 1990, 1991 (not completed)).

- Helmut Kühnel: Dictionary of Basque . Reichert, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-89500-121-X (dictionary Basque-German and German-Basque; tables on word formation suffixes and verbal morphology).

- Martin Löpelmann : Etymological dictionary of the Basque language . Dialects of Labourd, Lower Navarre and La Soule. 2 volumes. de Gruyter, Berlin 1968.

- Luis Mitxelena et alii: Diccionario General Vasco / Orotariko Euskal Hiztegia . 16 volumes. Real academia de la lengua vasca, Bilbao, ISBN 84-271-1493-1 (1987 ff.).

- Michel Morvan: Dictionnaire étymologique basque . basque-français-espagnol. ( projetbabel.org / given 2009-2017).

Grammars and textbooks

- Resurrección María de Azkue: Morfología vasca. La Gran enciclopedia vasca, Bilbao 1969.

- Christiane Bendel: Basque grammar. Buske Verlag, Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-87548-419-3 .

- JI Hualde, J. Ortiz de Urbina: A Grammar of Basque. Mouton Grammar Library. Vol 26. de Gruyter, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-11-017683-1 .

- Alan R. King: The Basque Language. A Practical Introduction. University of Nevada Press, Reno 1994, ISBN 0-87417-155-5 .

- Pierre Lafitte: Grammaire basque - navarro-labordin littéraire. Elkarlanean, Donostia / Bayonne 1962/2001 , ISBN 2-913156-10-X .

- JA Letamendia: Bakarka 1. Método de aprendizaje individual del euskera . Elkarlanean, Donostia.

- JA Letamendia: textbook of the Basque language. Translated into German and edited by Christiane Bendel and Mercedes Pérez García . Buske, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-87548-508-0 .

Language history

- Joxe Azurmendi : The importance of language in the Renaissance and Reformation and the emergence of Basque literature in the religious and political conflict area between Spain and France. In: Wolfgang W. Moelleken, Peter J. Weber (Hrsg.): New research on contact linguistics . Dümmler, Bonn 1997. ISBN 978-3-537-86419-2

- JB Orpustan: La langue basque au Moyen-Age. Baïgorri 1999. ISBN 2-909262-22-7

- Robert Lawrence Trask: The History of Basque. Routledge, London / New York 1997. ISBN 0-415-13116-2

- Eguzki Urteaga: La langue basque dans tous ses états - sociolinguistique du Pays Basque. Harmattan, Paris 2006. ISBN 2-296-00478-4

Kinship

- JD Bengtson: The Comparison of Basque and North Caucasian. In: Mother Tongue . Journal of the Association for the Study of Language in Prehistory. Gloucester MA 1999. ISSN 1087-0326

- Georgij A. Klimov: Introduction to Caucasian Linguistics. Buske, Hamburg 1994. ISBN 3-87548-060-0

- RW Thornton: Basque Parallels to Greenberg's Eurasiatic. In: Mother Tongue . Journal of the Association for the Study of Language in Prehistory. Gloucester MA 2002. ISSN 1087-0326

- M. Morvan: Les origines linguistiques du basque. Bordeaux, 1996. ISBN 978-2-86781-182-1

- RL Trask: Basque and Dene-Caucasian. In: Mother Tongue . Journal of the Association for the Study of Language in Prehistory. Gloucester MA 1995. ISSN 1087-0326 (With extensive and competent discussion of the subject.)

Others

- Michel Aurnague: Les structures de l'espace linguistique - regards croisés sur quelques constructions spatiales du basque et du français. Peeters, Louvain, et al. a. 2004. ISBN 2-87723-802-4 .

- Administración General de la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco, Departamento de Cultura: Euskara 21 - Bases para la política lingüística de principios del siglo XXI: Temas de debate. Vitoria-Gasteiz 2009

- Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco, Departamento de Cultura: 2006, IV Mapa Sociolingüístico. Vitoria-Gasteiz, 2009

- Jean-Baptiste Coyos: Politique linguistique - langue basque. Elkar, Baiona et al. a. 2004. ISBN 2-913156-65-7 .

- Elisabeth Hamel, Theo Vennemann: Vaskonian was the original language of the continent. In: Spectrum of Science . German edition of Scientific American . Spektrumverlag, Heidelberg 2002,5, p. 32. ISSN 0170-2971 (controversial discussion)

- Kausen, Ernst: The language families of the world. Part 1: Europe and Asia. Buske, Hamburg 2013. ISBN 978-3-87548-655-1 . (Chapter 5)

- Txomin Peillen: Les emprunts de la langue basque à l'occitan de Gascogne - étude du dialecte souletin de l'euskara. Univ. Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Madrid 1998. ISBN 84-362-3678-5

Web links

- Ernst Kausen: The Basque Language . ( MS Word ; 80 kB) Gießen 2001 (the essay is the basis for this article)

- (CNRS) Basque Language Academy

- Archive ARTXIKER Artxiboa: Archive de la Recherche pour la Langue basque et les Langues typologiquement proches

- Buber's Basque Page

- Basque course for beginners from Deusto University (in Spanish)

- Dictionnaire Freelang - Basque – French / French – Basque dictionary

- Morris Student Plus Hiztegia - Basque-English / English-Basque dictionary

- Euskonews - History of the last speaker of the Roncal dialect (Spanish)

- Muturzikin: Cartes linguistiques du Pays Basque. 2007 (French).

- Jacques Leclerc: Le Pays basque ( Memento of October 24, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ VI ° Enquête Sociolinguistique en Euskal herria (Communauté Autonome d'Euskadi, Navarre et Pays Basque Nord) (2016).

- ↑ Koldo Zuazo: Map of the Basque Dialects. 2008

- ↑ Diputación Foral de Alava: Informes sobre los grafitos de Iruña-Veleia (Reports and expert opinions on the inscriptions of Iruña-Velaia). November 19, 2008, Retrieved January 25, 2017 (Spanish).

- ↑ Mike Elkin: The Veleia Affair . In: Archeology . tape 62 , no. 5 , 2009 (English, archeology.org [accessed January 25, 2017]).

- ↑ Interview with Idoia Filloy. In: La Tribuna del País Vasco. February 11, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2017 (Spanish).

- ↑ Vitaly Shevoroshkin (Ed.): Dene-Sino-Caucasian Languages. Brockmeyer, Bochum 1991.

- ^ Georgij A. Klimov: Introduction to Caucasian Linguistics. German version by Jost Gippert, Hamburg 1994 [1] , p. 24

- ↑ Graphic for the hypothetical overview with timeline : A family tree of all the languages of Eurasia. From: Ulf von Rauchhaupt : Do you speak Nostratisch? FAZ , June 15, 2016 ( [2] on www.faz.net)

- ↑ Gerhard Jäger: How bioinformatics helps to reconstruct the history of language. University of Tübingen Swedish Collegium for Advanced Study, Seminar for Linguistics ( [3] on sfs.uni-tuebingen.de) here p. 12

- ↑ Morvan, M .: Les origines linguistiques du basque: l'ouralo-altaïque. Presses universitaires de Bordeaux, 1996.

- ^ Elisabeth Hamel, Theo Vennemann: Vaskonisch was the original language of the continent . In: Spectrum of Science . No. 05 . Spektrumverlag, Heidelberg 2002, p. 32 ( Spektrum.de [accessed on February 11, 2018]).

- ↑ Letra. In: Euskara Batuaren Eskuliburua. Euskaltzaindia , accessed on June 22, 2020 (eus).

- ↑ Description of the Basque Language: Vowels (Spanish)

- ↑ Description of the Basque Language: Consonants. (Spanish)

- ↑ Modified from: Jan Henrik Holst: Research questions on the Basque language. Shaker Verlag, Düren 2019.

- ↑ Thomas Stolz: Ergativ for the bloodiest beginners. (PDF) University of Bremen, pp. 1–12

- ↑ In typical Basque sentences, the verb comes at the end

- ↑ Singular form derived from the basic form

- ↑ In contrast to Indo-European languages such as Swedish

- ^ David Crystal: A Dictionary of Language and Linguistics . 6th ed., Blackwell 2008, p.444.

- ↑ The sentence does not mean the completely indefinite statement "Garfield is a (and any!) Cat" ( e.g. * Garfield katu da ).