Boží Dar

| Boží Dar | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Basic data | ||||

| State : |

|

|||

| Region : | Karlovarský kraj | |||

| District : | Karlovy Vary | |||

| Area : | 3791.3139 ha | |||

| Geographic location : | 50 ° 25 ' N , 12 ° 55' E | |||

| Height: | 1028 m nm | |||

| Residents : | 253 (Jan. 1, 2019) | |||

| Postal code : | 362 62 | |||

| License plate : | K | |||

| structure | ||||

| Status: | city | |||

| Districts: | 3 | |||

| administration | ||||

| Mayor : | Jan Horník (as of 2007) | |||

| Address: | Boží Dar 1 362 62 Boží Dar |

|||

| Municipality number: | 506486 | |||

| Website : | www.bozi-dar.cz | |||

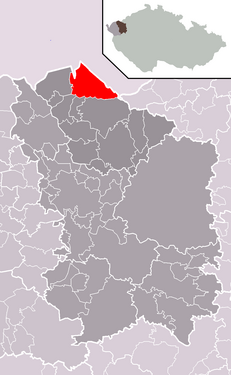

| Location of Boží Dar in the Karlovy Vary district | ||||

|

||||

Boží Dar ( German Gottesgab , Latin Theodosium ) is a city in Okres Karlovy Vary and the region of the same name in the Czech Republic . The old mountain town is an important winter sports center in the Ore Mountains and is considered the highest town in the Czech Republic.

geography

location

The city is located in western Bohemia on a plateau on the Ore Mountains ridge at an altitude of 1028 m nm . The border with Saxony runs north of the place . To the east rises the Klínovec ( Wedge Mountain ) and immediately to the southwest is the 1115 m nm high Božídarský Špičák ( Spitzberg ). Not far from Boží Dar, at the Börnerwiese at 1215 m above sea level. NN high Fichtelberg , the main source of the black water ( Černá ) lies on the German side . One of the tributaries flows directly through Boží Dar and flows into the black water at the location of the former New Mill.

City structure

The town of Boží Dar consists of the districts Boží Dar ( Gottesgab ), Ryžovna ( Soaps ) and Zlatý Kopec ( Golden Heights ). Basic settlement units are Boží Dar and Zlatý Kopec.

The hamlets are still in the corridors

- Myslivny ( Forester's Houses )

- Špičák ( Spitzberg houses ), demolished

- Solar vortex houses , canceled

- Neklid ( balance wheel )

- Mílov , previously Rozhraní ( half mile ), canceled

The municipality is divided into the cadastral districts of Boží Dar and Ryžovna.

Neighboring places

| Breitenbrunn / Erzgeb. | ||

| Potůčky (Breitenbach) |

|

Oberwiesenthal |

| Pernink (Bärringen), Abertamy (Abertham) | Jáchymov (St. Joachimsthal) |

history

The then Saxon region around Gottesgab was opened up by miners at the beginning of the 16th century. It was Zinnseifner who presumably penetrated this area long before 1520. In 1520 the Zwickau citizen Georg Zolchner owned the soaps in the upper Schwarzwassertal. The soaps in Gottesgab were leased to the Seifner for 5-10 groschen. Until then, the extreme weather conditions on the Erzgebirgskamm had prevented permanent settlement. Only the discovery of ore deposits offered an economic perspective in this inhospitable environment. As a result, a small settlement called Wintersgrün was established here, presumably as early as 1517. It was located in the extreme south of the Schwarzenberg rule , which belonged to the Lords of Tettau . In the south was the property of Count Schlick with the just blossoming mountain town of Sankt Joachimsthal . Tin soaping was expanded. Hans Brenner, owner of a Nuremberg company, received 80-100 florins a year from a soap from God. A smelter built by the Seifner Herald in Gottesgab was later taken over by the city's first magistrate, Georg Schmucker.

In 1526 Valten Thanhorn came across rich silver ores on the neighboring Fichtelberg in Schönburg , which led to the founding of the mountain town of Oberwiesenthal a year later . As early as 1525, the St. Lorenz mine in Gottesgab was muted to silver . On May 13, 1529, the Saxon Elector Johann Friedrich I declared in a letter that the area around Gottesgab was free from mining. At the same time he gives the settlement city rights; “ We also want to forever bless the same new mountain town for a free mountain town .” He uses his miner Hans Glaser to award the mines. Glaser was also responsible for allocating land and timber for the miners. Mining should be organized according to the Buchholz mining regulations. On May 30, 1533, the Saxon Elector Johann Friedrich I bought the Schwarzenberg rule for 20,700 Rhenish guilders from the brothers Albrecht Christoph and Georg von Tettau. When the mistake was discovered in 1533, there were border disputes with Count Schlick. However, these were amicably settled. In the spring of 1534 a mountain order for Gottesgab was drafted. While the Buchholzer Bergordnung only applied to silver mining, the elector, as the landowner, was now also responsible for tin mining.

The only road connection to the newly planned city was via Schönburg ground. In order to avoid conflicts and impending blockades, the elector had a new access road built over the Rittersgrüner Pass. On June 20, 1534, the elector gave his mountain master Hans Glaser the order to complete the new road from Schwarzenberg to Gottesgab. Today it is a popular cross-border hiking trail and leads from Rittersgrün via Goldenhöhe to Gottesgab.

In 1537 Gottesgab was separated from the Schwarzenberg mining area as a separate mountain area. The area included Goldenhöhe, Kaff (near Goldenhöhe), Kleiner and Großer Hengst (between Gottesgab and Abertham ), Mückenberg , Schwimminger with a young stallion , Irrgang and Zwittermühl .

In the Prague Treaty of October 14, 1546, Emperor Charles V, Duke Moritz of Saxony, promised from the Albertine line of the Wettins the transfer of the Saxon electoral dignity and territorial gains at the expense of the Ernestine line after the end of the Schmalkaldic War . In return, Moritz von Sachsen promised u. a., the Vogtland and the southern part of the Barony of Schwarzenberg with the mountain towns Gottesgab and plates in the possession of the Kingdom of Bohemia under Ferdinand I to pass. This regulation was implemented after the end of the Schmalkaldic War, which ended with the Wittenberg surrender on May 19, 1547 and from which the Ernestine Saxony emerged as the loser. Albertine Saxony received the other part of the Schwarzenberg rule. The division was anything but smooth. For example, there was disagreement about the layout of the mountain shelf. In order to create a fait accompli, Ferdinand issued the mining regulations for the new mining towns in 1548. He placed the formerly independent mining offices of Platten and Gottesgab under the administration of Joachimsthal and appointed Platten a royal mining town. According to the partition agreement, the income from the mining should actually be transferred to the Saxon Elector. However, the accounting documents of the Bohemian Crown were so opaque that the Saxon side was constantly forced to complain. A viable compromise could not be reached until 1553, when the division of mining revenues, tithe and taxes between Saxony and Bohemia was decided.

The economic decline began after the evacuation of Protestant families around 1650. As a result of the Counter Reformation , as in other areas of the Bohemian Ore Mountains, Protestant families were forced to look for a new home as exiles . They found a new home in the Saxon Ore Mountains and revitalized the local mining industry with their knowledge and experience.

After the First World War , in 1919 Gottesgab was added to the newly created Czechoslovakia . Due to the Munich Agreement , the city belonged from 1938 to 1945 to the district of Sankt Joachimsthal , administrative district Eger , in the Reichsgau Sudetenland of the German Empire .

The predominantly German-Bohemian population was largely expelled after 1945 . In the 1950s Boží Dar lost its town charter, but received it back on October 13, 2006.

Demographics

| year | Residents | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1783 | k. A. | 130 houses |

| 1830 | 1207 | in 190 houses |

| 1845 | 1456 | in 194 houses |

| 1869 | 1297 | |

| 1880 | 1380 | |

| 1890 | 1344 | in 162 houses, of which 1325 residents speak German as a colloquial German (1339 Catholics and five Protestants) |

| 1900 | 1314 | German residents |

| 1910 | 1386 | in 164 houses, of which 1310 residents speak German |

| 1920 | 1076 | including 13 Czechs |

| 1930 | 1070 | , according to other data 1048 inhabitants, 19 of them Czech |

| 1938 | 938 |

| year | 1950 | 1961 1 | 1970 1 | 1980 1 | 1991 1 | 2001 1 | 2011 1 |

| Residents | 816 | 341 | 152 | 128 | 111 | 170 | 193 |

Attractions

- Baroque church of St. Anna from 1772.

- Gottesgaber Hochmoor ( Božídarské rašeliniště ), through which a three-kilometer educational trail leads. There are typical bog plants such as the rare dwarf birch .

- Memorial to the local poet Anton Günther from Gottesgaber from 1936 on the green area in front of the town hall. Next to it is a memorial stone dedicated to the Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis , who lived from 1929 to 1931 in the nearby scattered settlement of Försterhäuser.

- The Plattner Kunstgraben begins to the west of the city center and a nature trail leads to Horní Blatná .

- To the west of the nearby Klínovec, a path branches off the road to the Dreiherrenstein near Oberwiesenthal .

- The cross-border Anton-Günther-Weg leads through the urban area .

Personalities

sons and daughters of the town

- Joseph Wenzel Peithner von Lichtenfels (1725–1807), Bohemian Gubernialbergrat, mine inspector and senior administrator

- Johann Thaddäus Anton Peithner von Lichtenfels (1727–1792), Bohemian mining scientist

- Anton Günther (1876–1937), poet and singer from the Ore Mountains, on whose 60th birthday in 1936 a memorial was erected

- Erwin Günther (1909–1974), speaker of the Ore Mountains dialect

- Ewald Roscher (1927–2002), ski jumper and national coach of ski jumpers

People connected to the city

- Nickel von Ende (1504 - after 1533), electoral Saxon civil servant, co-founder of the city

- Kaspar Eberhard (1523–1575), German Lutheran theologian

- Lukáš Bauer (* 1977), Czech cross-country skier

literature

- Bruno Wähner: City history of Gottesgab in words and pictures. Issue 1–7. Stadtverlag Gottesgab, Gottesgab, 1936–1937.

- Erich Matthes : Document book of the Erzgebirge mountain town Gottesgab. 1529-1546. sn, sl approx. 1960.

- Elisabeth Günther-Schipfel: Erzgebirge saga. (Life and death of the free mountain city of God's gift). Preussler, Nuremberg 1999, ISBN 3-925362-96-7 .

Web links

- Panorama drawing of the surrounding area

- City map of Bozi Dar ( Memento of November 24, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- Information center website (DE, CZ, EN, FR)

Individual evidence

- ↑ http://www.uir.cz/obec/506486/Bozi-Dar

- ↑ Český statistický úřad - The population of the Czech municipalities as of January 1, 2019 (PDF; 7.4 MiB)

- ^ Handbook of the latest geography of the Austrian imperial state: 1 . Bauer, 1817 ( google.de [accessed on March 10, 2019]).

- ↑ Části obcí - Obec Boží Dar Územně identifikační registr ČR, accessed on June 28, 2018.

- ↑ Základní sídelní jednotky - Obec Boží Dar Územně identifikační registr ČR, accessed on June 28, 2018.

- ↑ Katastrální území - Obec Boží Dar Územně identifikační registr ČR, accessed on June 28, 2018.

- ↑ Origin of the name Gottesgab. In: Johann Aug. Ernst Köhler : Book of legends of the Erzgebirge. Gärtner, Schneeberg et al. 1886, 445–446, no. 533 .

- ↑ Bohemian ore mining. Hermann, ISBN 978-3-940860-09-5

- ↑ Jaroslaus Schaller : Topography of the Kingdom of Bohemia . Volume 2: Ellbogner Kreis , Prague 1785, pp. 97-100 .

- ↑ Yearbooks of the Bohemian Museum of Natural and Regional Studies, History, Art and Literature . Volume 2, Prague 1831, p. 199, item 10).

- ↑ Johann Gottfried Sommer : The Kingdom of Bohemia . Volume 15: Elbogner Kreis , Prague 1847, p. 125.

- ↑ a b c d e Genealogy network Sudetenland

- ^ Meyer's Large Conversational Lexicon . 6th edition, Volume 8, Leipzig and Vienna 1907, p. 175 .

- ^ Michael Rademacher: German administrative history from the unification of the empire in 1871 to the reunification in 1990. District of Sankt Joachimsthal. (Online material for the dissertation, Osnabrück 2006).

- ↑ Historický lexikon obcí České republiky - 1869–2015. Český statistický úřad, December 18, 2015, accessed on January 19, 2016 (Czech).