German forest

The German Forest has been described and exaggerated as a metaphor and landscape of longing since the beginning of the 19th century in poems, fairy tales and sagas of the Romantic era . Historical and folkloric treatises declared him a symbol of the Germanic-German style and culture or, as with Heinrich Heine or Madame de Staël, as a counter-image to French urbanity. Reference was also made to historical or legendary events in German forests, such as Tacitus ' description of the battle in the Teutoburg Forest or the natural mysticism of the Nibelungenlied, stylized as a German national myth, as its diverse reception history shows.

The early nature conservation and environmental movement , tourism that began as early as the 19th century, the youth movement , social democratic nature lovers , hiking birds and hiking clubs, as well as the right-wing folk movement saw forests as an important element of German cultural landscapes .

In the National Socialist ideology, the motif of the “German Forest”, comparable to “ Blood and Soil ”, became a typical pattern. Propaganda and symbolic politics as well as landscape planning for the time after a German "final victory" included this centrally.

Albrecht Lehmann postulates the continuity of a romantic forest consciousness of the Germans spanning social classes and generations from Romanticism to the 21st century. The references to an intensive and pronounced handling of the forest as a cultural asset include the discussion of environmental damage, such as the " forest dieback " as well as the types of remembrance and mourning in the form of forest cemeteries and tree burials . Surveys show a specifically German equation of forest and nature. The forest as an educational medium and a place that is conducive to health is of particular importance in the context of environmental education (see, among others, forest education and forest kindergarten ) in the German-speaking area.

Forest as a central element of the landscape and national culture

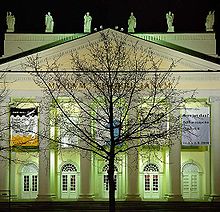

In Germany, forests are also known and institutionalized in the public consciousness, in folklore, in the media and in popular culture as a typically German backdrop. Der Freischütz , long referred to as the German national opera par excellence, the specifically German or Austrian appearance of the Heimatfilm , plays about robbers and game shooters like the Wirtshaus im Spessart , Jennerwein and the Brandner Kaspar are set against the wild and romantic backdrop of the German forest.

The exploitation of forests, not only by rural roads , but also by local and long-distance footpaths , hostels and cabins is an important aspect of the history of travel in Germany. In a lengthy process, forests and parks formerly reserved for the nobility and individual landowners were opened to everyone. The accessibility of state and private forests and natural beauties in general has constitutional status in some federal states (such as Bavaria). The pioneers were the Berlin Zoo in 1742 and the English Garden in Munich in 1789 , both of which were formerly closed hunting grounds for the nobility; the Essen Grugapark was only opened in the 20th century. The opening of the forests to the public can also be seen at events and holidays with processions and crossroads as well as demonstrations and festivals. Examples of this include the Frankfurt Wäldchestag , the May Day , Father's Day customs , Easter walks and Easter marches .

Without human influence, Germany would be almost completely covered by forest, mainly deciduous deciduous forest. Already in the Middle Ages, the forest in Germany was strongly pushed back by clearing for agricultural land and settlements. Forests currently still occupy a third of the German land area, especially in the low mountain ranges that were previously difficult to access, and represent an important economic factor. The designation of large forest protection areas as part of national parks based on the American model was and is subject to considerable conflicts of use in Germany. It did not come into play in the west until 1970 with the Bavarian Forest National Park bordering the Šumava Biosphere Reserve in the Czech Republic and in 1990 as part of the Harz National Park , which was adjacent to the Hochharz National Park in the GDR. The end phase of the GDR envisaged the protection of 4.5% of the GDR territory with the national park program , including the Spreewald and the former state hunting area Schorfheide , one of the largest contiguous forest areas in Germany.

The concept of sustainability , which is important in terms of both environmental and economic policy , was coined and practically implemented in German forestry as early as the 18th century, thus resolving conflicts with agricultural use differently than in Great Britain, for example. There, the grazing resulted in park-like landscapes (see English landscape garden ) with isolated hat trees and ongoing extensive deforestation of the landscape (see Clearances ). In contrast to the cleared areas and the heather economy of the north German lowlands, the forests in southern Central Europe were preserved over a large area like individual natural forest cells , the forest pasture was already stopped in the 19th century due to its harmful effects on the forest.

Cultural role of the forest in Germany

The cultural images of the “German” forest conveyed in the 19th century were primarily the result of urban, elitist thinking. However, these ideas were also adopted by industrial workers at the beginning of the 20th century. The romantic forest awareness of the Germans has since persisted across classes and generations into the 21st century, which in view of the political and social upheavals represents a remarkable continuity.

19th century

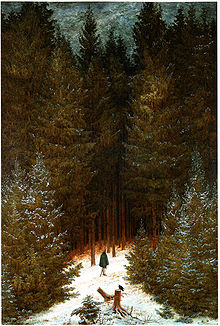

The pathetic evocation of the forest as an unadulterated “German” landscape began around 1800 in the poetry, painting and music of German Romanticism. During the Wars of Liberation from 1813 to 1815 against Napoleonic France, the German national movement declared the forest to be a symbol of national identity in historical reference to the mythical Hermannsschlacht in the Teutoburg Forest . The ideas of national unity and democracy in Germany, which originally came from the French Revolution, were a matter of the political opposition until the unification of the empire in 1871.

In this context, the career of the “German oak ”, which has quickly become proverbial, began as a national symbol of strength and heroism, as did its staging as apostrophized folk festivals. Was known in the pre-March , in the wake of the French revolution of July 1830 , the Hambach Festival on a ruin in the Palatinate Forest .

The romantic poets and painters who shaped the image of the German forest between nationalization and sentimentalization grew up with a supposed or actual wood shortage of the 18th century, but also with (coniferous) forests that were already subject to "enlightened" forestry calculations ; However, they also knew the lighter, oak-lined hat forests .

The poet Joseph von Eichendorff repeatedly conjured up the (“rushing”) forest, which functions as “a kind of echo chamber for the soul”. In his work, man's experience of separation from nature becomes just as clear as the attempt to aesthetically regain the unity that has been perceived as lost. In addition, in Eichendorff's explicitly political 'poems of time', the forest also functioned as the metaphorical epitome of national unity and freedom. In Wilhelm Grimm's understanding , dense forests next to remote mountains were the preferred areas in which folk traditions such as fairy tales and legends were most originally and completely preserved. In his influential German mythology, Jacob Grimm declared the forest to be a natural place of original folk belief and Germanic-German worship. The novelist Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl continued in 1854 in his main folklore work Natural History of the People. Land and people put the national character of the European peoples in a direct relationship to the environment around them , which is why the preservation of the forest was more of a national political than an economic necessity for him. Characteristic landscapes of the English and French, according to Riehl, were the tamed park and the cleared field , the counterpart of which he saw in the “forest wilderness” of the Germans. The "gymnastics father" Friedrich Ludwig Jahn struck even more nationalistic tones with his demand for afforestation especially on the borders of the German Reich against potential aggressors and Ernst Moritz Arndt , who understood the forest as a prerequisite for the survival of the German people.

At the beginning of the 19th century, Carl Maria von Weber turned to the local folklore , the popular character and affinity to the people as well as the folk song of the German cultural area, but also of other nations. In some of his works he combines the discovery of nature - and also the forest - for music with his patriotic attitude and his affirmation of the national character of art. Already in his opera Silvana , and later increasingly in Freischütz , a “romantic German spirit” is expressed especially in the forest and hunting scenes. In the opera Der Freischütz he implements the fairytale-romantic notion of the early 19th century of the forest as a place of danger and terror, but also of piety and redemption, above all through a new type of instrumentation. In the course of the German-national endeavors from the end of the 19th century, however, the Freischütz was seen overall as a musical reflection of the German Forest .

Hans Pfitzner wrote in 1914:

- “The heart of the Freischütz is the indescribably intimate and sensitive feeling for nature. The main character of the Freischütz is, so to speak, the forest, the German forest in the sunshine [...] Weber's broadcast was a national one - it was about the freedom and global validity of Germanness, ... "

A primary intention of Weber with regard to this later 'national interpretation of Freischütz cannot be proven.

Already at this time Wilhelm Hauff addressed in “The Cold Heart” (1827) the advance of capitalist ways of thinking in the Black Forest using two worlds that he described as contradicting: on the one hand the lumberjacks and raftsmen trading with the Netherlands, on the other hand those of him as the down-to-earth world of the Koehler and Glashüttner.

Empire and Weimar Republic

After the unification of the empire in 1871, national identity was increasingly sought in the early Germanic and medieval German past. This romanticizing and retrospective movement can be seen as a contradiction to the parallel industrialization and the emergence of mass tourism in the context of Rhine romanticism . It was reflected in the creation and protection of landscape parks and natural monuments , a national monument policy specifically in Germany . Monumental buildings such as the Niederwald Monument , the Hermann Monument , the Kyffhäuser Monument , the long controversial and recently not carried out reconstruction of the Heidelberg castle ruins and some buildings by the Bavarian fairy tale king such as Linderhof and Neuschwanstein programmatically include the surrounding forests. The progressive democratic tradition, for example in connection with the Hambach Festival , was put aside.

As early as the end of the 19th century, in addition to its socio-economic function, important social, health and educational tasks were assigned to the forest in Germany. Michael Duhr speaks of a large number of contemporary representations by foresters, educators, doctors, town planners and nature and homeland protection movements in this context. Life reformers and wandering nature enthusiasts and protectors, the wandering bird movement as well as the Bundische Jugend from 1890 saw in forest hiking not only a reference to nature but also a reference to a refuge of cultural traditions, especially Germanic mythologies. Hiking (in the forest) should help to develop norms and values such as “loyalty”, “camaraderie”, “helpfulness” and “naturalness”, just as the forest teaches instinct control and frugality and serves to toughen up. In the socialist youth and nature organizations, the aspect of "social wandering" was added with an emphasis on anti-militarism, education and solidarity.

After the German defeat in World War I and the end of the Wilhelmine Empire, the ideological charge of the forest became radicalized. The erection of a “national memorial” to commemorate the dead of the First World War was suggested by Reich President Friedrich Ebert and Reich Chancellor Wilhelm Marx in 1924 , and there was consensus among social democrats up to the extreme right that this memorial could only be found in a forest as a “primary cause”. and “source of strength” of the Germans. At the same time, this localization (a forest near Bad Berka was the preferred location for this never-implemented idea ) avoided any specific reference to controversially discussed events of the war and its consequences as well as current political developments.

For the emerging “Heimatschutz” movement, the “German forest” was the epitome of German essence, which was to be defended against western “civilization” and against the “threat from the east”. Particularly active in this regard was the German Forest Association, founded in 1923 - Association for Defense and Consecration of the Forest , which, under the patronage of former Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, operated tireless forest propaganda using forest notebooks and forest publications as well as a newspaper supplement titled German Forest .

In addition to representing the interests of forest owners and users, this association was also concerned with an undamaged national self-confidence after the lost First World War. Only “German” plants and “German” animals should find their place in the “German forest”. In connection with the stab-in- the-back legend , socialists, Jews and French were named as enemies of the German forest as well as of the German people, thus instrumentalizing the forest for chauvinist and anti-Semitic arguments. In 1929 Kurt Tucholsky made the claim beyond the “national” or bourgeois-militarist faction that the political left must also think along when thinking about “Germany”, and he included the (German) forest very closely in his German landscape descriptions.

National Socialism

ideology

During the time of National Socialism, some influential political actors such as the Reichsforstmeister, Reichsjägermeister and Reich nature conservation officer Hermann Göring , the Reichsführer SS and temporary interior minister Heinrich Himmler and the Nazi ideologist Alfred Rosenberg pursued a comprehensive ideologization of the natural phenomenon of the forest. According to Johannes Zechner, the “German forest” became the code for a multitude of modernity-critical, nationalistic , racist and biological thought patterns. This included the holistic nature of the forest as a counter-image to progress and the big city, the forest as home, as a Germanic sanctuary and “racial source of strength”. The Germans were seen as the original "forest people" following the Germanic tribes, while the stigmatization of the Jews as "desert people" was intended to justify their discrimination and persecution.

In 1936 the montage film Ewiger Wald , produced by the National Socialist Cultural Community (NSKG) under the direction of Alfred Rosenberg, announced the message that the Germans were a forest people and therefore "eternal" like the forest. Forest was associated with harmony. The destruction of forests was also equated with the destruction of the people. German history since Arminius - "Hermann the Cheruscan" - was closely related to the forest. The Weimar Republic is cited as a high point of the forest crime in the film: “rotten, decayed, interspersed with a foreign race. How do you carry the people, how do you carry the forest the unthinkable burden ”. The film, produced with great effort, was not a success with the public and should not have pleased Hitler. Allegedly he grumbled that the forest was a retreat for weak peoples, while the strong, warlike romped about in the wide steppe.

The research work Wald und Baum in the Aryan-Germanic intellectual and cultural history , initiated by Heinrich Himmler's SS-Ahnenerbe , wanted to prove the existence of an early “tree and forest religion” based on the assumed “forest origin” of the Germanic culture, in order to create a “species-specific religion” on this basis “To establish National Socialist beliefs.

A visible expression of the National Socialist “view of the forest” was the “ Hitler empire” , which was supposed to replace dance linden trees and maypoles , and some programmatic tree plantings called “ swastika forests” such as in the Uckermark pine forest. In the early days of the Nazi regime, 200 to 400 so-called Thing places were planned, mostly in “German forests” as part of the Thingspiel movement ; only 60 of these National Socialist open-air theaters were completed. The early Nazi order castles were also influenced by “forest ideological” considerations in terms of architecture and their integration into the landscape.

Reich nature protection, planning

Research on ecology, geography, soil science and forestry and forestry was intensified by the National Socialists. Legislative procedures with intensive propaganda support included the forest; Animal welfare law was passed in 1933 . 1934 was from Kurt coat commented Reich forest devastation bill passed first, reach Forstgesetzgebung, 1934, the Reich Hunting Act , including a bid Hege and 1935 the Reich Nature Protection Act adopted.

During the expansion of the Reichsautobahn and the associated deforestation, a general "experience" of the German (forest) landscapes was emphasized under the aegis of Alwin Seifert with a landscape-related placement of bridges and crossings. The technical specifications for integrating this central infrastructure and propaganda project into the topography and the design were based, among other things, on the American model of the United States Highways .

After the initially very influential representative of homeland security architecture , monument conservator and homeland security officer Paul Schultze-Naumburg fell out of favor in favor of Albert Speer after a dispute with Hitler in 1935 , the folkish approaches and also the forest ideological projects became opposed to neoclassical monumental rulership architectures and plans such as war preparation repressed. Reichsjägermeister Göring initially spread propagandistic criticism of capitalism and anti-Semitism:

"If we [sc. Germans] walking through the forest […], the forest fills us with […] an immense joy in God's wonderful nature. That distinguishes us from that people who think they have been chosen and who can only calculate the solid cubic meter when they walk through the forest . "

Significant forest ideological plans were made for the time after the envisaged final victory. Hermann Göring's Reichsforstamt planned extensive reforestation of the annexed Polish territories for the reforestation of the East as part of the settlement planning of the General Plan East , before which almost 900,000 Poles were deported to the “ General Government ” and over 600,000 Jews to ghettos and concentration camps.

In contrast to the ideological elevation of the forest, there was the planning and forestry reality. When Göring took over the four-year plan and the agricultural and forestry policy in 1936, nature conservation stagnated. Among other things, the logging and thus the pollution of the forests have increased significantly. As early as 1935, forestry had to subordinate itself to the National Socialists' self-sufficiency efforts. As of October 1935, a logging has been arranged for the state forest, 50% higher than the annual growth of wood went. From 1937 this also applied to community and private forest over 50 ha. Extensive destruction of nature was carried out through amelioration , motorway construction , the intensification of forest use and the construction of industrial and military facilities. The overuse of ecological resources due to the abrupt transition to self-sufficiency, with inefficient use due to lack of economic structural change, became a motive for conquering new living space .

From Heimatfilm to the wilderness debate

The immediate post-war period was characterized by increased stress on the forests. As part of reparations, massive deforestation was carried out, as in the case of the French felling , the use and utilization of wood as fuel and building material led to considerable price increases such as intensive clearing of the forests and approaches to reforestation measures.

The Schutzgemeinschaft Deutscher Wald (SDW) was founded in Bad Honnef in 1947 in order to counteract the overexploitation of the forest caused by the consequences of the war . This makes it the oldest German citizens' initiative.

The otherwise rather seldom preoccupation with numinous and mysterious aspects of the forest was mainly found at that time with Will-Erich Peuckert . With the currency reform and the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany, forest was once again included in German national symbolism, both in the depiction of oak leaves on coins and bills as well as the " oak planter " on the 50-pfennig pieces of the former D-Mark; In the GDR , the oak leaves were part of the NVA cockade .

In the early 1950s, trivial literature and homeland films such as Der Förster vom Silberwald used the German forest as a popular setting. In the film Sissi , Duke Max, played by Gustav Knuth , expressed the quasi-religious feeling for the forest of the 1950s:

“If you have grief and worries once in your life, then go through the forest with your eyes open as you do now. In every tree, in every bush, in every animal and in every flower you will become aware of God's omnipotence and give you comfort and strength. "

In the 1970s, there was a renaissance of the preservation of monuments, which was discredited by the use and abuse under National Socialism, as well as of nature conservation under pan-European auspices. The eighties and nineties reflected a still specifically German approach to the forest as a cultural asset in the context of the discussion of environmental damage, such as the " death of forests " in the more recent commemorative culture as well as in the popularity of forest education such as tree burials in existing cemeteries or in forests .

Conceptual pairs such as wilderness and cultural landscape have been structuring the debate in nature conservation and about the forest for decades. In Europe, in contrast to North America, the wilderness debate does not have a long tradition. In 2002 Stremlow and Sidler noted a change in the perception of the forest as a threatened, sensitive ecosystem worthy of protection, as in the 80s, towards a real longing, a desire for wilderness as a cultural phenomenon. The concept of wilderness was historically shaped by a cultural understanding of primeval landscape that was inhabited by more or less “ noble savages ”. In the meantime, the ecologically reduced concept of a nature largely uninfluenced by humans had been emphasized.

In view of an enormously increased interest in nature and landscape in the form of wilderness, in a boom in leisure activities such as adventure vacations and extreme sports, in advertising, in educational concepts and in the design of landscape architecture, attempts are being made to make wilderness accessible again as a cultural concept for nature conservation do. This is particularly important when it comes to the combination of forest and mountains in the (German) low mountain range, just as the increasing accessibility and availability of fallow land and abandoned areas is a planning issue.

The necessary active restoration of wilderness through active human involvement appears paradoxical, which is expressed in titles such as “The next forest will be different” or “Wh (h) re wilderness”. In addition, aesthetic points come into play - primeval forests are accepted and demanded, but bark beetle infestations , windthrow areas and the consequences of forest fires should be eliminated as quickly as possible.

Forest and culture of remembrance

In 1960, Elias Canetti , in his major work Mass and Power, emphasized the effect of the early and intensely cultivated romanticism of the German forest on the Germans. Canetti brings the German forest in connection with the army as a German mass symbol, literally:

- “The mass symbol of the Germans was the army. But the army was more than the army: it was the marching forest. In no modern country in the world has the forest feeling remained as lively as in Germany. The rigidity and parallelism of the upright trees, their density and number fill the heart of the German with deep and mysterious joy. He still likes to visit the forest where his ancestors lived and feels at one with trees. "

In US memory, the battle in the Huertgen Forest in World War II plays a central role as the first major field battle of the Americans and defeat on German soil and the longest battle of the US Army. The American processing cites well-known German myths and cultural elements, describes the Hürtgen Forest as a "black-green ocean of forest in which Hansel and Gretel lost their way", as " Verdun on the Eifel" and, due to the forest fighting, as "anticipated Vietnam". Ernest Hemingway called the forests of the Eifel "forests in which the dragons live", terms such as " dragon teeth ", " Siegfried line ", "Hell forest" with connotations to the Nibelungenlied , the Nazi propaganda of the "eternal forest" and on Ghost and witch tales in the deep fir.

The considerable fears of further advance and (cf. werewolf ) sustained resistance against the Allied occupation after the end of the war were not confirmed, contrary to expectations, which still played a role in the American planning for the Iraq war . A mystification can also be seen in the casualty figures, which were initially compared to the Battle of Gettysburg and the entire Vietnam War, which was exaggerated according to recent figures.

The battle in the Hürtgenwald was also indirectly the subject of the Bitburg controversy . Locally, historical-literary hiking trails recall the participation and literary processing of the battles in the snow-covered Hürtgenwald by Ernest Hemingway , Heinrich Böll , Paul Boesch , Samuel Fuller and Jerome David Salinger . Heinrich Böll's essay “You enter Germany” from 1966 contrasts the fighting in the Hürtgenwald with the post-war cooperation of the NATO allies in the region as part of a landscape study.

Forest dieback

As deforestation , also known as "novel forest damage" Forest of damage in central and northern Europe are called, have been identified since the mid-70s and discussed. The occurrence of extensive damage to forest trees and tree species that are important for forestry led to fears that the entire forest area in Germany on a third of the country's area is in danger.

The dying forest was portrayed by some critics as a "fantasy of nature conservationists" and described as a German media cliché which, especially in the early 80s, conjured up a completely exaggerated apocalyptic doomsday scenario and triggered alarmism. In the poetry and prose of the 80s, as with Günter Kunert , it was claimed that the German forest gave its last performance.

In France, “le Waldsterben” was initially considered to be a German mental illness. Some French forest damage was noted in the 1980s but was discussed publicly to a much lesser extent. This difference has been attributed several times to “une affinité culturelle des Allemands vis-à-vis de la forêt” (a special relationship between Germans and the forest).

A debate focused more on the raw material aspect and the availability of wood arose around a feared wood shortage around 1800 and was also particularly widespread in German-speaking countries.

Forest art

During the Kassel documenta in 1982, Joseph Beuys began his art campaign 7000 oaks - urban deforestation instead of city administration , which was one of the most elaborate German art campaigns.

The techno artist Wolfgang Voigt dealt with the topic of the “German forest” in the music albums of his project Gas . This was reflected in titles such as Zauberberg (1997) or Königsforst (1998), the cover design and, last but not least, the tonal references to Wagner's work . Voigt saw the aim of the project as “bringing the German forest to the disco”. He was sometimes criticized for this as an advocate of a German nationalism. Voigt himself emphasizes in this context that it was not about promoting German national feelings, but about "creating something like 'genuinely German pop music' aside from the usual clichés".

The Association for International Forest Art eV has been organizing the " International Forest Art Path " in Darmstadt every two years since 2002 . On 3.3 km from the Böllenfalltor to the Ludwigshöhe in the Darmstadt forest district, the forest is brought into the focus of the visitors in a special way with the means of art. This designed forest experience is intended to encourage the observers and walkers to explore with the means of art.

literature

- Wilson, Jeffrey K. The German Forest: Nature, Identity, and the Contestation of a National Symbol, 1871-1914 . Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012. ISBN 9781442640993 .

- Ursula Breymayer, Bernd Ulrich: Under trees. The Germans and their forest. Sandstein Verlag, Dresden, 2011. ISBN 978-3-942422-70-3 .

- Kenneth S. Calhoon / Karla L. Schultz (Eds.): The Idea of the Forest. German and American Perspectives on the Culture and Politics of Trees , New York et al. 1996 (= German Life and Civilization, 14).

- Roderich von Detten (Ed.): And the forests die forever. How the debate about forest dieback changed the country , oekom Verlag Munich 2012. ISBN 978-3-86581-448-7 .

- Christian Heger: The forest - a mythical zone. On the motif history of the forest in the literature of the 19th and 20th centuries . In: Ders .: In the shadow realm of fictions. Studies on the fantastic history of motifs and the inhospitable (media) modernity . AVM, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-86306-636-9 , pp. 61-85.

- Ute Jung-Kaiser (Ed.): The forest as a romantic topos. 5th interdisciplinary symposium of the University of Music and Performing Arts Frankfurt am Main 2007 . Peter Lang Verlag, Bern u. a. 2008, ISBN 978-3-03-911636-2 .

- Albrecht Lehmann : Of people and trees. The Germans and their forest . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-498-03891-5 .

- Albrecht Lehmann, Klaus Schriewer (eds.): The forest - a German myth? Perspectives on a cultural topic . Reimer, Berlin and Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-496-02696-0 (Lebensformen, 16).

- Carl W. Neumann: The book from the German forest - A guide to homeland love and nature conservation , Georg Dollheimer publishing house, Leipzig 1935, http://d-nb.info/361261470 .

- Erhard Schütz: Blissfully lost in the woods. Forest walker in German literature since the Romantic era . Pressburger Akzente, 3rd edition Lumiere, Bremen 2013, ISBN 978-3-943245-12-7 .

- Erhard Schütz: Romantic forest work . In: Claudia Lillge, Thorsten Unger, Björn Weyand (eds.): Work and idleness in romanticism . W. Fink, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3770559381 , pp. 329-344.

- Ann-Kathrin Thomm (Ed.): Mythos forest. Book accompanying the traveling exhibition of the same name by the LWL Museum Office for Westphalia . Münster, 2009, ISBN 3-927204-69-2 .

- Viktoria Urmersbach: In the forest, there are the robbers. A cultural history of the forest. Past Publishing, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-940621-07-8 .

- Bernd Weyergraf (ed.): Forests : The Germans and their forest. Exhibition catalog of the Academy of Arts . Nicolai, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-87584-215-4 (Academy Catalog 149).

- Johannes Zechner: The German forest. A history of ideas between poetry and ideology 1800–1945 , Darmstadt 2016. ISBN 978-3-805-34980-2 .

- Johannes Zechner: 'The green roots of our people': On the ideological career of the 'German forest' . In: Uwe Puschner and G. Ulrich Großmann (eds.): Völkisch und national. On the topicality of old thought patterns in the 21st century . Knowledge Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2009. ISBN 978-3-534-20040-5 (Scientific supplements to the Anzeiger des Germanisches Nationalmuseums, 29), pp. 179–194.

- Johannes Zechner: "Eternal Forest and Eternal People": The ideologization of the German forest under National Socialism . Freising 2006, ISBN 3-931472-14-0 (Contributions to the cultural history of nature, 15).

- * Johannes Zechner: Politicized Timber: The 'German Forest' and the Nature of the Nation 1800-1945. In: The Brock Review 11.2 (2011), pp. 19-32 .

- Johannes Zechner: From Poetry to Politics. The Romantic Roots of the "German Forest" . In: William Beinart / Karen Middleton / Simon Pooley (Eds.): Wild Things. Nature and the Social Imagination, White Horse Press Cambridge 2013. ISBN 978-1-87426775-1 . Pp. 185-210.

- * Johannes Zechner: Nature of the Nation. The 'German forest' as a thought pattern and worldview. In: From Politics and Contemporary History 67.49-50 (2017), pp. 4-10 .

- In particular, the subjective and collective meaning of the “German forest” culture pattern was examined in two ethnographic research projects funded by the DFG . DFG-Projekt Lebensstichwort Wald - Contemporary and historical studies on the cultural significance of forests .

Web links

- Herbert Heinzelmann: The German forest . In: Goethe.de , September 2016

- Johannes Zechner: The forest and the Germans . In: Forschung-und-Lehre.de , July 29, 2018

- Anja Wölker: The Germans and their forest - adored and demonized . In: Planet-Wissen.de , October 28, 2019

Individual evidence

- ↑ Publications on the history of the reception of the Nibelungenlied by Otfrid-Reinald Ehrismann ( Memento of the original of April 3, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed July 23, 2009

- ↑ "Immediately on the border of our new living space to the east, trees must also stand as German symbols of life." From: Heinrich Friedrich Wiepking-Jürgensmann: German landscape as a German task to the east In: Neues Bauerntum, vol. 32 (1940), volume 4 / 5, p. 132.

- ↑ a b Lehmann, Albrecht (2001): Mythos deutscher Wald. In: State Center for Political Education Baden-Württemberg (ed.): The German Forest . 51st year issue 1 (2001) The citizen in the state . Pp. 4-9

- ↑ Birgit Heller, Franz Winter (ed.): Death and ritual: intercultural perspectives between tradition and modernity. Austrian Society for Religious Studies, LIT Verlag, Berlin-Hamburg-Münster, 2007, ISBN 3825895645

- ↑ Forest pedagogy and perception of forest and nature, cultural conditions of nature conservation and environmental education against the background of changing social natural conditions, master's thesis in the sociology course, presented by Markus Barth, reviewer: Erhard Stölting and Fritz Reusswig, Berlin, August 16, 2007

- ↑ Erhard Schütz: Dense forest . In: Ursula Breymayer, Bernd Ulrich: Under trees. The Germans and their forest. Sandstein Verlag, Dresden, 2011, p. 111. ISBN 978-3-942422-70-3

- ↑ Klaus Lindemann: 'German Panier, the rustling waves'. The forest in Eichendorff's patriotic poems in the context of the poetry of the Wars of Liberation . In: Hans-Georg Pott (Ed.): Eichendorff and the late romanticism . Ferdinand Schöningh Verlag, Paderborn u. a. 1985, ISBN 3-506-76955-3 , pp. 91-130.

- ^ Wilhelm Grimm: Preface to children's and house tales [1812 and 1815], in: Wilhelm Grimm: Kleinere Schriften I. Edited by Gustav Hinrichs, Ferdinand Dümmlers Verlagbuchhandlung Berlin 1881, pp. 320–332, quoted on p. 320.

- ^ Jacob Grimm: Deutsche Mythologie, Dieterichsche Buchhandlung Göttingen 1835, p. 41.

- ↑ Johannes Zechner: From 'German oaks' and 'eternal forests'. The forest as a national-political projection surface. In: Ursula Breymayer, Bernd Ulrich (2011), p. 231.

- ^ Karl Laux: Carl Maria von Weber. Reclam Biografien, Reclam, Leipzig 1986, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ a b c Elmar Budde: Horns sound and sinister powers - To Carl Maria Weber's opera Der Freischütz , in: Helga De la Motte-Haber, Reinhard Copyz: Musicology between art, aesthetics and experiment. 1998, p. 47 ff.

- ↑ Quoted from Udo Bermbach: Opernsplitter. Königshausen & Neumann, 2005, p. 110.

- ^ Duhr, Michael (2006): The cultural phenomenon of the forest. The forest as an educational resource for schools, In: Corleis, Frank (Hrsg.): School: Forest. The forest as a resource for education for sustainable development in schools, School Biology and Environmental Education Center Lüneburg SCHUBZ, 225 pp.

- ^ Benjamin Ziemann : Forest violence. Forest and war. In: Ursula Breymayer, Bernd Ulrich (2011), p. 227 f.

- ^ Wikisource home of Kurt Tucholsky

- ↑ Joachim Radkau, Frank Uekötter: Nature Conservation and National Socialism, editors: Joachim Radkau, Frank Uekötter, Campus Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-593-37354-8 , ISBN 9783593373546 , p. 47 (online)

- ↑ text log of the film Eternal Forest (1936). Copy in the Federal Film Archive Berlin. Quoted in Karl Kovacs: The forest as an ideological instrument in the Third Reich. Grin Verlag, ISBN 3640337085 , ISBN 9783640337088 , p. 12. (online)

- ↑ according to Ulrich Linse: The film Ewiger Wald - or: the overcoming of time through space. A cinematic implementation of Rosenberg's myth of the 20th century. In: Ulrich Herrmann / Ulrich Nassen (Ed.): Formative Aesthetics in National Socialism. Intentions, media and forms of practice of totalitarian aesthetic domination and domination, Beltz Verlag, Basel - Weinheim 1993 (= supplements to the Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, vol. 31), pp. 57–75.

- ^ A b Wolfgang Schivelbusch: Distant Affinities Fascism, National Socialism, New Deal 1933-1939 Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2005 ISBN 3-446-20597-7 , overview and reviews at perlentaucher.de

- ↑ Joachim Radkau, Frank Uekötter: Nature Conservation and National Socialism, editors: Joachim Radkau, Frank Uekötter, Campus Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-593-37354-8 , ISBN 9783593373546 , p. 71 ( online )

- ↑ quoted from Johannes Zechner: The green roots of our people. On the ideological career of the 'German forest' . In: Uwe Puschner and G. Ulrich Großmann (eds.): Völkisch und national. On the topicality of old thought patterns in the 21st century . Knowledge Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-534-20040-5 , p. 182.

- ↑ See Heinrich Rubner: Deutsche Forstgeschichte 1933–1945. Forestry, hunting and the environment in the Nazi state , Sankt Katharinen 1985 (2nd, expanded edition, 1997, ISBN 3-89590-032-X ).

- ↑ Joachim Radkau, Frank Uekötter: Nature Conservation and National Socialism , ed. v. Joachim Radkau, Frank Uekötter, Campus Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-593-37354-8 , ISBN 978-3-59337-354-6 , p. 125.

- ^ Walter Grottian, 1948: The crisis of the German and European wood supply

- ^ Edeltraud Klueting: The legal regulations of the National Socialist Reich government for animal welfare, nature conservation and environmental protection . In: Joachim Radkau, Frank Uekötter (ed.): Nature Conservation and National Socialism , Frankfurt / New York (Campus Verlag) 2003, pp. 104f.

- ↑ Joachim Radkau: Nature and Power. A world history of the environment . Munich 2002, p. 297 f.

- ↑ World forestry and Germany's forestry and timber industry, Johannes Weck, C. Wiebecke Verlag BLV Verlagsgesellschaft, 1961

- ↑ Report from the DFG project 'Forest', Institute for Folklore, University of Hamburg ( Memento of the original from April 26, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Institute for Folklore / Cultural Anthropology, report by Klaus Schriewer and Helga Stachow on the FP Lebensstichwort Wald (from the Hamburger Platt issue 2, 5/1995 and issue 2, 7/1997)

- ↑ Kenneth Anders, Jadranka Mrzljak, Dieter Wallschläger & Gerhard Wiegleb: Handbook open country management: Using the example of former and in use military training areas, editors: Kenneth Anders, Jadranka Mrzljak, Dieter Wallschläger, Gerhard Wiegleb, Springer Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3540224491 , ISBN 9783540224495 , P. 169

- ^ Matthias Stremlow & Christian Sidler: Writing trains through the wilderness. Wilderness notions in literature and print media in Switzerland. Bristol Foundation, Zurich. Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL, Birmensdorf. Haupt Verlag, Bern, Stuttgart, Vienna 2002. 192 pp.

- ^ "Forests and high mountains as ideal types of wilderness. A cultural-historical and phenomenological investigation against the background of the wilderness debate in nature conservation and landscape planning". Diploma thesis in the landscape architecture and landscape planning course at the Technical University of Munich, submitted to Ludwig Trepl, Chair of Landscape Ecology, second supervisor: Vera Vicenzotti, by Markus Schwarzer, Freising, in January 2007

- ↑ Böhmer, Hans Jürgen 1999: In the next forest everything will be different. Political Ecology 59: Wa (h) re wilderness. Ökom Verlag, Munich. Pp. 14-17.

- ↑ Bavarian Forest National Park: Our wild forest - No. 21 ( Memento of the original from May 14, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 1.4 MB) Winter 2007

- ^ Mass symbols of the nations, in Elias Canetti: Mass and Power, Fischer 1980 (1960) pp. 190f

- ↑ www.huertgenwald-film.de - YOU ENTER GERMANY - Konejung Foundation: Culture quoted from the film project on the battle in the Hürtgenwald, 2007, funded by the Konejung Foundation

- ↑ In the footsteps of Böll and Hemingway, by Reiner Züll, Kölner Stadtanzeiger, August 15, 2008, Neue Wanderwege are dedicated to the Hürtgenwald battles as reflected in literature. Hikes: In the footsteps of Böll and Hemingway, Region - Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Heinrich Böll: Articles, reviews, speeches. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne, Berlin 1967

- ↑ The so-called forest dieback. Rudi Holzberger. Publisher: Eppe 2002. ISBN 3-89089-750-9 , first edition 1995 as a dissertation in Konstanz

- ^ Armin Günther, Rolf Haubl, Peter Meyer, Martin Stengel: Sociological Ecology: An Introduction, edited by Armin Günther, Verlag Springer, 1998, ISBN 3540644318 , ISBN 9783540644316 , p. 184

- ↑ See Under dying trees: ecological texts in prose, poetry and theater: a green literary history from 1945 to 2000 , Jonas Torsten Krüger, Verlag Tectum Verlag DE, 2001 ISBN 3828882994

- ↑ So with Matthias Horx and Dirk Maxeiner

- ↑ The German Forest gives its last performance, by Günter Kunert, in Der Wald. Essay / photographs by Guido Mangold u. a. Hamburg: Ellert & Richter Verlag. 1985

- ↑ DFG project forest dieback

- ↑ The German forest in the disco. Interview with Voigt at Telepolis .

- ^ International Forest Art Center - Darmstadt .