Helena Petrovna Blavatsky

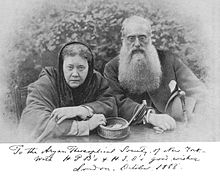

Helena Blavatsky (born Helena Petrovna Hahn-Rottenstein , after the first marriage Russian Елена Петровна Блаватская , Jelena Petrovna Blawatskaja , Eng. Transcription Yelena Petrovna Blavatskaya ; born July 31, jul. / 12. August 1831 greg. In Yekaterinoslav , New Russia , Russian Empire ; † May 8, 1891 in London ) was a Russian-German occultist . Her main works Isis Unveiled (1877, German:Isis unveiled ) and The Secret Doctrine (1888, German: The Secret Doctrine ) contributed significantly to the foundation of modern or Anglo-Indian theosophy and gained a significant influence on wide areas of modern esotericism . In 1875, Blavatsky foundedthe Theosophical Society with Henry Steel Olcott .

Life

Childhood and adolescence

Helena von Hahn was born in Yekaterinoslav (now Dnipro, Ukraine) in 1831. Her father Peter von Hahn was an officer in the mounted artillery and the son of Lieutenant General Alexis Hahn von Rottenstein-Hahn ; he came from a Mecklenburg family who were in Russian service. Helena's mother Jelena Hahn (Russified Gan), née Fadejewa, was a well-known novelist and the daughter of the Privy Council Andrei Fadejew and a princess, Princess Helene Dolgoruki . About this line she was the cousin of the Russian statesman and reformer Sergei Yulievich Witte . As a child, Helena lived with her mother with her grandparents. As a member of the Imperial Russian Army, his father was stationed in constantly changing garrisons in the Caucasus .

When she was eleven, her mother died giving birth to her second child, her sister Vera, and Helena spent the rest of her childhood with her grandparents. The grandfather was a high government official in the newly formed provinces of the Russian Empire and changed location several times. As an adolescent she drew, played the piano and was an excellent rider who enjoyed riding semi-wild horses. According to the testimony of her aunt Nadjezhda (Nadja) Fadejev, she already felt attracted to the simple way of life in her childhood and later, and was emphatically indifferent to the nobility. At the same time, her openness in particular caused difficulties, because she told her counterpart directly in the face what she thought of him. On the other hand, she was always ready to do anything for a friend and give everything to those in need. She is said to have been quick-tempered and rebellious and found it difficult to conform to the conventions of her social class.

Even as a child it caused quite a stir as a “ writing medium ”. As a twelve-year-old she was automatically writing extensive manuscripts that had been sent to her in the media by a deceased German-Russian woman whose pictures and letters she had played with as a five-year-old. However, after a few years it was found that the woman was still alive. Helena's interest in esotericism was sparked by the extensive library of her great-grandfather, a Masonic with a Rosicrucian orientation, which she studied extensively. A high "sensitivity" was attributed to her, as she constantly saw ghost figures in her surroundings , and her family subjected her to several exorcisms because of somnambulism .

Marriages and children

At the age of 17, Helena married the much older General and State Councilor Nikifor Blavatzky (also: Blavatsky, actually Blavacki), Vice-Governor of the Russian Caucasus province of Yerevan in today's Armenia, in Tbilisi in 1848 . The theologian Gerhard Wehr suspects that the marriage only served her to be respected as a married woman. After a short time, according to her own statements after three months, she left her husband as a virgin because of the great age difference and fled to Egypt.

On April 3, 1875, Helena Blavatsky married again, this time the Armenian Michael Betanelly. She made the condition that she keep her name and that the marriage not be consummated. This marriage was divorced on May 25, 1878, whereupon Blavatsky said with relief that “the thought of being able to reveal her body to a man was so appalling and incomprehensible to her that she only gave her consent to a sham marriage by an obsession at the time. ”According to some sources, she is said to have married the opera singer and Carbonaro Arkadi Metrowitsch, whom she met in 1850 and with whom she devoted herself to the production of inks and artificial flowers. In the spring of 1860 Blavatsky traveled with her sister to Tbilisi, where she wanted to stay. At the grandfather's request, she had to return to her husband, with whom she then lived for a year. She spent most of the time in her grandfather's palace , where almost every evening invited guests gathered for their séances to be entertained by moving the table , writing ghost messages and other manipulations. In 1863 she again spent three days with her first husband Nikifor in Tbilisi.

Her alleged son Yuri (also: Juri) is said to have been born in 1861 or 1862, who died at the age of five. She gave Baron Nicholas Meyendorff from Tbilisi as her father . It was questioned whether she could get pregnant at all because of the medical findings of a possible congenital malformation of the uterus . Towards the end of her life, Blavatsky sued the New York newspaper Sun for alleging she had an illegitimate child. She also had a gynecologist certify her virginity, and the Sun published a reply a year after her death. The Blavatsky biographer Marion Meade , on the other hand, thinks it is likely that Yuri was not her only child.

Wandering years

Over two decades from 1848 to 1872 Blavatsky left largely unconfirmed and partly contradicting statements, which made her biographer AP Sinnett almost desperate. While traveling through Europe, Asia and America, which were financed by her father and grandfather, she is said to have received the basics of her later teachings from initiates and “masters”.

After separating from her first husband, she went back to her grandfather's house, who sent her to her father in the port city of Poti . There she became friends with the captain of an English steamer, which it for passage to Constantinople Opel as a (disguised) sailors hired . In 1850 she hired herself as an art rider in the circus in Constantinople , where she met the Hungarian opera singer and Carbonaro Arkadi Metrowitsch, whom she then accompanied on his opera tours. She then traveled to Egypt, Greece and the Balkans with the Russian Countess Kisselev, whom she also met in Constantinople .

In Cairo in the same year she came into contact with the Coptic magician and occultist Paulos Metamon , who is said to have been one of her teachers in those early years.

In 1851 she went with a friend from France to the world exhibition in London, where she claims to have met her "Master Morya" for the first time in a physical body that had already appeared to her in visions in her childhood. According to research by Paul Johnson, Morya was not a real person; rather, at the specified time, Blavatsky met the Italian freedom fighter Giuseppe Mazzini , whom she admired and who was in exile in London. Inspired by the novels by James Fenimore Cooper , she then traveled to Québec , where she wanted to study Indian shamanism . This was followed by a stay in New Orleans with research on the voodoo cult practiced there .

She spent most of the year 1852 in Latin America . In the same year she went to India and tried for the first time, albeit unsuccessfully, to get to Tibet , which was then very isolated . In the following years she stayed mainly in the Middle and Far East and in the USA . In 1855, Blavatsky is said to have tried in vain to enter Tibet via India, disguised as a man.

Mesmerism Studies and Conversion to Spiritism

In 1856 she stayed in France to study mesmerism , which was flourishing there. In Paris she appeared as assistant to the spiritualist Daniel Dunglas Home and became the conductor of the royal Serbian choir. Next she went via Germany to the Balkans, where she performed again as a riding artist. She traveled to Cairo with the opera singer Metrowitsch and a Madame Sébire. In the same year she said she converted to spiritism in Paris.

In 1858 she returned to her Russian homeland for the first time via Germany and the Balkans. There she appeared on the estate in Rugedow of her sister Vera, who was now married, where she soon became the center of society with her spiritualistic activities. Until 1863 she stayed mainly with her family in Russia. It is unclear where she stayed in the following years.

- Italian irregulars under Giuseppe Garibaldi

After Yuri died in 1867, Blavatsky said she joined the Italian Risorgimento , whose anti-clericalism she shared. According to her own statements, she took part in the Battle of Mentana and was wounded several times. According to one version she was saved by the Red Cross , according to another by the intervention of her Indian “masters”. In the rich literature of the participants in this battle between the troops of Giuseppe Garibaldi on the one hand and the Papal States and France on the other, there is no mention of a Russian fighter disguised as a man. According to the Italian historian Lucetta Scaraffia, this episode in Blavatsky's biography has the function of a “political initiation ” into enmity against the Catholic Church , from which the Eastern religion offers salvation.

- Shipwreck and death of Metrowitsch

In 1870 Blavatsky lived with Metrowitsch in Odessa , where she made a living for the two of them with singing lessons, various temporary jobs in shops and as a factory worker. Because their ink factory, a wholesale business and an artificial flower shop, which opened in quick succession, were complete failures, Metrowitsch accepted a commitment in Cairo.

In 1871 she boarded the ferry SS Eumonia with Metrowitsch to Alexandria , where Metrowitsch intended to continue his operatic career. On board were 400 passengers, a load of gunpowder and fireworks. On July 4, 1871 there was an accident during the crossing when the gunpowder magazine exploded in the Gulf of Nauplia , whereupon the ship capsized. Metrowitsch was killed in the process. Blavatsky was one of the 17 castaways who survived the disaster and were stranded in Egypt.

- Foundation of the Société spirite

She stayed in Egypt until 1872, where she founded the spiritist association Société spirite . Because of an allegedly ectoplastically materialized hand, which during research turned out to be a tricky device for moving a stuffed glove dummy , Blavatsky was convicted of fraud a short time later and had to dissolve the association again.

Tibet

In 1868, according to Blavatsky's information, the master Morya came into contact with her. Allegedly they traveled together to Tibet, where they stayed for a long time in Samzhubzê , the seat of the Penchen Lama , and was initiated into Tibetan Buddhism . Whether she was actually ever in Tibet is a matter of dispute. Blavatsky's claims, however, are supported by her previously unknown descriptions of the city of Xigazê and her knowledge of Mahayana Buddhism, which she was certified by respected Buddhist scholars. According to research by the biographer Marion Blade, Blavatsky was not, as she claimed, in Tibet for seven years, but rather trundled through Europe during this time. Blavatsky's myth of the "masters" who allegedly lived in Tibet benefited for a long time from the fact that the real empire of the Dalai Lama was inaccessible and thus shrouded in mystery until the British Tibet campaign in 1903 . Your claims could therefore not be verified.

In the following years Blavatsky stayed mainly in the Middle East, where she met other masters who were familiar with the Greek, Coptic and Druze mysteries. In 1873 Morya is said to have contacted her again and instructed her to go to New York.

New York years

Since her father, who had previously financed her trips generously, had recently passed away, Blavatsky arrived in New York on July 7, 1873, almost penniless. Through their common interest in spiritualistic séances , she met the agricultural expert and later lawyer Henry Steel Olcott in 1874 , who appeared in spiritualist circles as a medium for materialization and contacts with the hereafter. Olcott became her confidante, student, and eventually her manager.

Spiritist meetings

Blavatsky became interested in spiritualism at an early age and held spiritualistic meetings in Cairo as early as the 1860s. She was admired in America's spiritualist circles, which had expanded rapidly since 1848, and she was attended to at her séances , which she held regularly from 1874 onwards. Her friend Olcott persuaded Blavatsky to join his spiritualist circle and tried to make her popular as a medium in relevant circles. A certain "John King" acted as Blavatsky's "guardian spirit" at that time. Olcott and Blavatsky founded the "Miracle Club" in May 1875, the meetings of which were kept secret. Since spiritism was generally discredited by press reports about charlatans, Blavatsky ended her activities in this regard from mid-1875. Now she and Olcott were looking for new ideological foundations to explain the spiritualistic phenomena and to fathom the truth of the religions. The "Miracle Club" was renamed on November 17, 1875 in the initially secret Theosophical Society ( Theosophical Society ).

Turning to esotericism

Around the beginning of 1875, Blavatsky began to preach esoteric teachings, initially building on the western esoteric tradition. Her apartment on Irving Place in Manhattan became a meeting place for people interested in her teachings. At the same time, she began to write her first book, and in July 1875 an article appeared in the magazine Spiritual Scientist in which she publicly presented her views for the first time, and in considerable detail. With this publication she apparently also introduced the term occultisme , which until then had only been used in French, into English.

- Foundation of the Theosophical Society

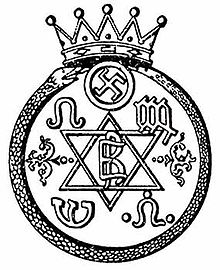

Blavatsky's transition from practicing spiritualist to theosophist took place after she gave the “spiritualistic phenomena” a monistic interpretation. Her breakthrough to monism meant that she overcame the conventional explanation of spiritualistic phenomena as the effects of spirits of the dead and instead interpreted them as emanations of a universal spirit. An ideal continuity between the Haeckelian monism, which was experiencing a real fashion wave at the time, and theosophy was later explicitly affirmed by Rudolf Steiner when he entered the theosophical society. The Theosophical Society (TG) was conceived and founded as a secret society in Blavatsky's apartment in the fall of 1875 , with Olcott, who was the first to propose such a society, was elected as president. Blavatsky acted as secretary, but was the real spiritus rector of the company. The later Vice President George Henry Felt and Charles Carleton Massey , who founded a branch in London on June 27, 1878, were co-signers of the charter . The study of occultism, Kabbalah and similar teachings of Western esotericism was recorded as a task of the society in the minutes of the founding meeting . According to the statutes, which were developed later, the aim was to "collect and disseminate knowledge about the laws that rule the universe". Instead of the medial transmission of messages from the hereafter, the appropriation of “old secret doctrines” should take place, which was seen as the core of all world religions. On this basis, the aim was to create a new world religion .

- Arya Samaj

The TG's last general meeting took place in July 1876. Two years after it was founded, its activities came to a standstill. The Indian Mooljij Thackersey, with whom Olcott had corresponded for a few months, put Blavatsky and Olcott in contact with Dayananda and his Hindu reform movement Arya Samaj (" Aryan Congregation "), which seemed to them to be a kind of Indian Theosophical Society. At Olcott's suggestion, it was incorporated into the TG on May 22, 1878. The merged association was called Theosophical Society of the Arya Samaj of India until March 1882 .

After Blavatsky was the first Russian to take American citizenship on July 8, 1878, she left the United States with Olcott on December 17 and never returned.

Activities in India and Ceylon

On February 16, 1879, Olcott and Blavatsky arrived in Bombay . The following evening there was a great reception for them at the house of Chintamon Hurrychund, the president of the Arya Samaj , where the two were quartered. But the next day, your host presented his theosophical guests with an invoice for his expenses. It turned out that he had embezzled the donations entrusted to him, whereupon the friendship was broken. Blavatsky and Olcott moved into quarters on Girgaum Back Road for the next two years .

The disputes with the Arya Samaj in 1878 led to the formulation of those three theosophical principles that still form the "program" of the TG:

- Formation of a nucleus of a universal brotherhood regardless of race, creed, gender, caste or skin color

- Promotion of comparative studies of world religions, philosophy and natural sciences

- Research into previously undiscovered laws of nature and human psychological forces.

On December 17, 1879, the statutes of the TG were changed at a theosophical meeting and all characteristics typical of a secret society such as secret symbols and secret writing were abolished. The Esoteric School ( Esoteric Section ) as the inner circle of the TG remained a secret society. Soon afterwards, Blavatsky began work on her second major book project, and in October the magazine The Theosophist appeared for the first time as the monthly publication organ of the TG. Through extensive travels and correspondence with leading intellectuals and politicians in India, Blavatsky and Olcott promoted theosophy. In May 1888 they converted to Buddhism in Ceylon . Blavatsky had already called herself a Buddhist during her time in New York. This brought her into a certain contrast to the Hindu-influenced theosophists. From then on she maintained contact with spirits , whom she referred to as masters and mahatmas . Her advocacy of Indian religion and philosophy coincided with the growing self-confidence of the Indian educated bourgeoisie towards the influences of the European colonial powers. Ranbir Singh, the Maharaja of Kashmir , sponsored their trips. Another important ally was Sirdar Thakar Singh Sandhanwalia, the founder of the Singh Sabha Movement , a Sikh reform movement in the Punjab .

Constitution of the Secret Doctrine in Madras

In December 1882 the headquarters of the TG were relocated to the village of Adyar near Madras , and after years of intensive travel, Blavatsky spent most of the year 1883 there, writing numerous articles for the theosophist . In it she dealt above all with the concept of the sevenfold constitution of humanity and the cosmos, which took the place of the three-part scheme rooted in ancient European traditions, which she had presented in Isis Unveiled and has since been fundamental in modern theosophy. In India theosophy was given a systematic version. In Madras she wrote her main work, The Secret Doctrine , in which she was again guilty of plagiarism, only this time she copied from contemporary works of Hinduism and modern science. The Secret Doctrine rejects ancient Egypt, which was previously considered the TG's source of wisdom, and pretends to know all of God's activities from the beginning of creation to its end, and describes them as ever-repeating cycles.

Counterfeit allegations

While Blavatsky and Olcott were temporarily in Europe in 1884, where theosophy also found increasing followers, an article appeared in Madras Christian College Magazine in September 1884 in which Blavatsky was accused of fraud in connection with the so-called Master's Letters. These letters, which have been received in large numbers by various theosophists since 1880, were attributed to the "masters" Koot Hoomi and Morya, who set out their teachings in them. In Madras Christian College Magazine it has now been claimed under the title The Collapse of Koot Hoomi that these alleged masters letters were in fact written by Blavatsky. The article was based on the statements of a former employee of the TG in Adyar, Emma Coulomb (hence the " Coulomb affair "), and on alleged letters from Blavatsky to Coulomb, which support Coulomb's statements. Blavatsky firmly denied these allegations but, on the advice of Olcott and others, failed to take legal action.

Division of the TG and flight to Europe

The Coulomb affair severely damaged the reputation of Blavatsky and the TG. A growing number of followers doubted their integrity and many admirers turned their backs on their former idol. Others steadfastly believed in the reality of the phenomena and their masters. In this atmosphere of slander and accusation, the American branch of the TG split from the Indian branch. In February 1885 Blavatsky fell seriously ill, which ultimately led to her having to resign from her position as Corresponding Secretary of the TG on March 21, 1885.

Blavatsky was on the verge of death, the doctors diagnosed an incurable disease of the heart and kidneys and gave her another year to live. When news of an impending libel suit by the Coulombs against the theosophist Henry Rhodes Morgan , who had called Emma Coulomb a fraud, arrived, the TG rushed to decide that Blavatsky had to leave India unobtrusively in order to forestall a summons and to keep the TG harmless . Since her own friends had conspired against her, she left India on March 31, 1885, escaped and psychologically broken, accompanied by Franz Hartmann forever, to spend the last years of her life in Europe.

Last years and death

After Blavatsky finally returned to Europe, she spent the summer of 1885 in Italy.

Exile in Würzburg and Ostend

In August 1885 Blavatsky settled in Würzburg in the house of Constance Wachtmeister . Wachtmeister took over the fair copy of the manuscript of the Secret Doctrine . On December 31, 1885, the final report of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) arrived, which followed on from the Coulomb affair, and reinforced the allegations against Blavatsky. This report, known as the Hodgson Report , was based on research and interviews conducted by Richard Hodgson on behalf of the SPR in Adyar. Hodgson came to the conclusion that the master craftsman's letters were forgeries, some of which had been made by the " impostor " Blavatsky herself, and some by someone else. In addition, Blavatsky had simulated paranormal phenomena in connection with the "appearance" of the letters. In addition, the TG's goals are in fact political, and Blavatsky is a Russian spy . This SPR report, quasi a scientific confirmation of the allegations made in the context of the Coulomb affair, branded Blavatsky as a fraud for a long time. In 1986, a good 100 years later, the SPR published a new investigation in which both Coulomb's accusations and Hodgson's conclusions were rejected. In July 1886 Blavatsky moved to Ostend (Belgium).

Move to London

At the turn of the year 1886/87 she completed work on the first volume of the Secret Doctrine . Already weakened by a severe chronic kidney disease, she moved to London on May 1, 1887, where she founded the magazine Lucifer . In the last years of her life, Blavatsky invested a large part of her energy in securing her position in the TG. In the open power struggle against Olcott, things smoothed a little when Blavatsky founded her own Esoteric Section of the TG for England on May 19, 1887 , in which she gave esoteric instructions to her closest students, whom she had recruited from the Blavatsky Lodge , which she had recently formed .

In October 1888 came the publication of her magnum opus, The Secret Doctrine - the Synthesis of Science, Religion, and Philosophy (German: The Secret Doctrine ). In 1889 Blavatsky published two more books: The Voice of the Silence (German: The Voice of the Silence ) and The Key to Theosophy (German: The Key to Theosophy ). Similar to The Secret Doctrine, The Voice of the Silence is conceived as a translation of supposedly very old texts and deals with the ascent to higher levels of consciousness, while The Key to Theosophy gives a popular introduction to Blavatsky's theosophy.

With the founding of the British Section of the TG, Blavatsky raised a further claim to representation that Olcott did not accept. Therefore, in 1890, she separated her British lodges from the Adyar TG and declared herself head of the European TG groups, which marked the break. In July of the same year, the New York Sun newspaper published an article by the influential American theosophist Samuel Elliott Coues , in which he described Blavatsky as a cheater. This sparked a lawsuit, which was put down without result after Blavatsky's death. (However, on another indictment brought by William Quan Judge , Secretary General of the American TG, the New York Sun distanced itself from Coues' article in 1892 and printed an obituary written by Judge for Blavatsky.)

Ailing for a long time, she died after an acute cold on May 8, 1891 in London. Over 100 obituaries and numerous letters to the editor from Theosophists appeared in the British press.

Teaching

Blavatsky developed as Theosophy called, syncretic belief, the same is the teaching of the TG. In contrast to Christian theosophy, the Anglo-Indian direction of its religious syncretism pursues the goal of attaining a higher form of "truth" through esoteric knowledge, occult training and the study of Far Eastern religiosity. The term theosophy is used as another name for the primarily monistic system of interpretation of modern spiritualistic or old magical and religious practices that has emerged since the 19th century under the name “ occultism ”.

Blavatsky's teaching was also referred to as " esoteric Buddhism", which, in contrast to orthodox Buddhism, which was called exoteric , was the only true one. This teaching must not be confused with older esoteric traditions within Buddhism such as the Vajrayana, which is also referred to .

Isis unveiled

1877 appeared Blavatsky's first work Isis Unveiled ( Isis Unveiled ), in which she turned away from spiritualism. Instead, it now ties in with Indian teachings such as Hinduism and Buddhism. At the same time she tried to prove that the spiritualism and clairvoyance , hypnosis, (day) dreams and all “miracles” that she had represented up to then came from a common tradition. In doing so, she pretended to be based on the alleged "occult teaching of ancient Egypt ", in which a primordial religion is revealed, from which all religions that exist today arose. This teaching is able to resolve the contradictions between spirituality , rational philosophy and the natural sciences. Most reviewers were disparaging or confused.

Isis unveiled was less of an overview of Blavatsky's new religion and more of a tirade against the rationalistic and materialistic culture of the modern Western world. In order to discredit the trust of her readers in the prevailing worldview, she made use of various secondary sources on pagan mythologies , mystery cults , Gnosticism , Hermetics , the Arcane tradition of the Renaissance and even secret societies such as the Rosicrucians , whose common origin they located in ancient Egypt. She was largely inspired by the literary works of Edward George Bulwer-Lyttons . The book was a success: the first edition of 1,000 copies was sold out after ten days.

The secret doctrine

Blavatsky presented her own teaching mainly in The Secret Doctrine in 1888. In this work she no longer referred to the wisdom of Egypt, but oriented herself towards Indian and Tibetan traditions. The book is said to be based on the " stanzas " of the Book of Dzyan , a supposedly very old religious text. Dzyan is the Tibetan name of the Daoist Ly-tzyn, who lived in the fourth century and wrote a book of secret correspondence .

Their theosophy was a reaction to the triumphant advance of the natural sciences , Darwin's theory of evolution and the associated discrediting of the Christian faith in the 19th century. In addition, in the Secret Doctrine, Blavatsky tied in with the then modern Western ideas, namely the idea of progress and race theory . In it she claimed to proclaim a scientifically founded religion.

According to the historian Goodrick-Clarke , it gave man back the dignity and importance that the Judeo-Christian doctrine of creation had ascribed to him and that no longer played a role in the scientific worldview, by embedding him in a cosmology , which traditional ideas of the western world Combined esotericism with elements of Eastern religions and also incorporated concepts from contemporary natural sciences. Blavatsky was critical of Christianity, especially the Catholic Church and Protestantism , throughout his life; She made an exception to this anti-clerical stance in self-admitted inconsistency only with regard to the domestic Russian Orthodox Church .

Doctrine of reincarnation and karma

The secret doctrine is based eclecticistically on Buddhism, Hinduism and various other wisdom doctrines . The first volume, entitled Cosmogenesis, deals with the evolution of the cosmos, and the second, Anthropogenesis , deals with the evolution of mankind as a succession of so-called root races . In it she postulated the existence of an absolute, infinite and eternal reality, which conditions everything. The cosmos as well as the human soul emerge from this absolute ( emanation ). Blavatsky linked this idea with the modern scientific concept of evolution. Accordingly, the evolution of the cosmos, as well as that of every human individuality, takes place in cycles of emanation from the absolute and the return to the absolute, but not in the sense of an eternal return of the same, but connected with progress from cycle to cycle. With humans it is about the succession of numerous embodiments of the immortal individuality ( reincarnation ), which are connected by the principle of karma . Added to this was their practice of clairvoyance , which is of particular importance in Tibetan Buddhism.

However, as Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke writes, these representations in The Secret Doctrine only form the background for the central theme of the work: the development of human individuality through reincarnation and karma, with fate in a present life being the result of one's own deeds and thoughts is in previous lives and the goal is an ascent to higher and higher spiritual levels.

In Blavatsky's view, the Buddha had a secret teaching whose true esoteric meaning was withheld from uninitiated researchers. Buddha answered questions about metaphysics , soul and eternity to only a limited number of people . In her book Keys to Theosophy, Blavatsky revealed these secrets, which are also the subject of her secret doctrine and which roughly contain the philosophy of theosophy. It is characterized by the mixing of Brahmanic and Buddhist teachings with reference to Sanskrit sources, since the Pali canon was not yet accessible at that time.

Cosmos and anthropogenesis

Another fundamental concept of Blavatsky's teaching is the sevenfold constitution of man and the cosmos. In humans, she distinguished (similar to the theosophist Alfred Percy Sinnett in Esoteric Buddhism , 1883) seven components or principles, four of which are mortal and three are immortal. Likewise, the earth and every other celestial body are constituted sevenfold, and the evolution of every planet proceeds in sevenfold cycles. So the earth develops first descending from a spiritual via a mental and an astral stage to the present physical and then ascending again via an astral and a mental to a spiritual stage. Only the present fourth stage is visible. Within this physical stage of the evolution of the earth, Blavatsky developed her own race mythology: In it she further distinguished seven stages of the development of humanity, which she called " root races ". With these, too, it is initially a question of a descent into matter, followed by a spiritualization. She referred to the present fifth stage of humanity as the "Aryan" root race. Each root race in turn consists of seven successive "sub-races", and the current stage of human evolution is the fifth or Anglo-Saxon sub-race of the Aryan root race.

Doctrine of the Ascended Masters

An important aspect of Blavatsky's theosophy is her teaching of the Ascended Masters. She developed the idea that religious founders and other outstanding people like Buddha or Jesus enter a spiritual sphere after their life on earth, where they form the "Great White Brotherhood" and through predestined people who serve them as a medium, the fate of the Determine humanity.

In their own accounts of their biography and the origin of their theosophy, the so-called masters or mahatmas are of great importance. Even in her childhood she had dreamed of a “Master Morya”, and she first met him in person in 1851 in London's Hyde Park . At that meeting, he told her that she had been chosen for an important task and that she had to prepare for it in Tibet beforehand. In 1868 he made contact with her again and they traveled to Tibet together, where Morya and another master named Koot Hoomi ran a school for adepts of Tibetan Buddhism in Samzhubzê , in the vicinity of the Penchen Lama’s seat . There she was accepted as a student and instructed for about two years. Then she consulted other masters of secret teachings in the Middle East. Her trip to New York in 1873 was again at the behest of the (probably fictitious) Morya, and the founding of the TG there as well as the later relocation to India was initiated by the masters. Furthermore, the masters appeared as the alleged authors of the controversial masters or Mahatma letters (see above).

After Blavatsky's stay in India, there were important changes in their ideas about the "Masters" ("Mahatmas"), namely Koot Hoomi and Morya . Now she passed her Mahatmas as members of a "Great White Brotherhood". According to Blavatsky, the “masters” sent letters by post or by “occult” channels. Blavatsky's teachings are a syncretism of already existing teachings, whereby she was initially influenced by Russian, Rosicrucian-oriented Freemasonry and then got to know other secret teachings on her travels in the Near and Middle East. The concept of masters can be derived from Rosicrucianism through high-level Freemasonry. The teaching of the Great White Brotherhood of Tibet and the story of the Masters were invented in the Arya Samaj .

Whether these masters really existed is controversial in the publications on Blavatsky. According to Paul Johnson, the masters were neither real nor entirely fictional, but rather deck identities made up by Blavatsky for various real people who had inspired or helped her. So when Master Koot Hoomi actually meant the Sikh politician Sirdar Thakar Singh, Master Morya stood for Ranbir Singh, the Maharaja of Kashmir .

Blavatsky's “ascended masters” were emotionally involved in the disputes of the TG and expressed themselves only “too humanly” in the Mahatma letters. They complained about a lack of paper, gave swipes at other competing masters, and their apparent misogyny was astonishing in view of Blavatsky's role: women were described as a "terrible calamity in this fifth race, " lacking any male power of concentration, and so on.

Posthumous effect

Helena Blavatsky is considered to be the most important figure in the founding of modern western esotericism in the late 19th century. She was the first to merge Eastern and Western wisdom teachings into a new system, referring to the early Rosicrucians , the alchemists and the medieval theosophists as well as to ancient Indian Vedic religions and Tibetan Buddhism. In addition to this effect in Europe and America, it was at times very popular among spiritual seekers in India.

Frequent fragmentation resulted in a wide organizational diversification of the TG, whereby theosophical ideas spread in numerous groups and mixed with other ideas. Views from Blavatsky's secret doctrine have now almost become “common property” of esotericism and are now also received by communities that are not directly connected to theosophy. Several splits emerged from the TG itself, such as the Liberal Catholic Church or the Archan School, which spread Blavatsky's ideas. The best-known German offshoot of theosophy was the German section of the Theosophical Society , headed by Rudolf Steiner from 1902 to 1913 , which initially made strong reference to Blavatsky's teachings (see, for example, Steiner's work: From the Akasha Chronicle ). When the director of the Theosophical Society Adyar , Annie Besant, propagated Jiddu Krishnamurti, who was then proclaimed a “world teacher”, as the theosophical leading figure, Steiner separated from the theosophical movement. The reason for this, in addition to personal competition, was his decidedly anti-Eastern course: He increasingly relied on Western esoteric traditions such as Rosicrucianism and a “ Christology ” with the “Myterium of Golgotha ” as the central event. The cosmic dimension of Steiner's “theosophical Christology” largely agrees with the ideas from Besant's system of thought, just as his idea of a “cosmic Christ” is a concept that was coined by Besant according to Werner Thiede . The Anthroposophical Society was founded in 1913 (re-establishment in 1923: General Anthroposophical Society ).

Occultism, Neo-Paganism and New Age

Blavatsky's teaching was of great importance to occultism and neo-paganism , generating new doctrines, orders and associations, and influencing writers and artists such as Hermann Hesse , William Butler Yeats , James Joyce , George William Russel , Jack London , D. H. Lawrence , TS Eliot , Wassily Kandinsky , Piet Mondrian , Paul Klee , Paul Gauguin , Gustav Mahler , Jean Sibelius , Alexander Scriabin and others. The magician Aleister Crowley came into contact with Blavatsky's teaching through the poet Yeats, who was a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn .

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, supporters of the New Age movement also referred to Blavatsky's world of thought and theosophy.

criticism

Blavatsky was proven to be fraudulent during his lifetime, and she was accused of fraud, especially in connection with the Meister letters (see above under “Life” as well as the Coulomb affair and the Hodgson report ).

Travel to Tibet

Blavatsky claims to have stayed in Tibet for a total of seven years. Despite many attempts, theosophists were unable to provide any evidence for this. Today it is believed that she never lived near Trashilhünpo , and there is no evidence that she ever set foot in Tibet, where she allegedly learned Sanskrit from masters and claims to have been initiated into the occult sciences. None of the numerous travelers to Tibet has ever heard or seen of Blavatsky's Indian masters from the Trashilhünpos area. Blavatsky's descriptions of Tibet, who pretended to be a “Tibetan Buddhist”, are only very superficial and extremely rare, and the teachings that are presented as Tibetan are mostly gross distortions that have nothing to do with Tibetan Buddhism. Blavatsky's teaching on transmigration (reincarnation and rebirth) is completely distorted and shows no conformity with Buddhism or any other doctrine.

The Book of Dzyan

The authenticity of Dzyan's book has been questioned by various quarters since 1895. The language "Senzar", in which it is said to have been written, cannot be proven anywhere in terms of linguistic history.

Racial Doctrine

The question of whether Blavatsky's root race doctrine is racist is controversial in research. The German historian of religion Helmut Zander refers to a ranking that Blavatsky assigned to the “races”. In the Secret Doctrine, for example, she emphasized " degrees of intellectuality between the various human races - the wild Bushman and the European". Even if she did not see herself as a racist, but stated the fraternal unification of all people as her goal , she legitimized the imperialism , colonialism and social Darwinism of her present. The German historian Jürgen Osterhammel also attests to Blavatsky adding “a dash of Aryan racism” to her teaching. According to the English religious scholar Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke , Blavatsky's teaching emphasized "in addition to an emphasis on questions of race, the principles of elitism and the value of hierarchies ". Therefore, the reception of their “mystical racism” in right-wing extremist circles is not surprising.

The American racism researcher George L. Mosse admits that later racist movements, such as ariosophy , were linked to theosophy, but emphasizes that theosophy itself was not racist. Rather, in contrast to European racism, it assumed that the Indian religions were superior to the European religions. The German theologian Linus Hauser also believes that racist concepts such as Adolf Hitler's Blavatsky were alien. The in their view necessary extermination of older races takes place with it rather through natural disasters. Nevertheless, their concept, which he calls "cosmic racism", has proven to be a treasure trove for ariosophical racial theorists such as Guido List and Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels . The American religious scholar James A. Santucci emphasizes that Blavatsky was concerned with the unity and the divine origin of mankind, not the differences between races. In this respect all racist undertones are alien to theosophy; Blavatsky used the term race only "because of its scientific connotation", "a term that fits well with the idea of distinct evolutionary stages of humanity". Israeli religious historian Isaac Lubelsky, like Mosse, points to Blavatsky's admiration for non-European cultures, but notes that the Secret Doctrine was "full of notes, remarks, and theories that a modern reader would most likely define as racist." As an example, he cites the extinct Tasmanians , whom Blavatsky describes as a sterile race inferior to the Europeans. This theosophical race theory is only a reflection of the scientific zeitgeist of the 19th century, on which Blavatsky was strongly based. Above all, she did not derive any political demands from her concept of race: therefore, there was no racist practice among the theosophists, and Blavatsky only made a marginal contribution to the development of the racist ideologies of the 20th century, particularly National Socialism .

The Canadian religious scholar Gillian McCann takes a mediating position. She points to the ambiguity of the theosophical positions on racial issues: On the one hand, Blavatsky propagated human brotherhood across all religious and ethnic boundaries and argued clearly not in a Eurocentric way ; on the other hand, the theosophists would have retained the prejudices and attitudes of their social environment. Although abstract concepts of general fraternity have been adopted, actual practice has often proven to be more problematic.

Plagiarism

Blavatsky's first work, Isis Unveiled , with over 1,000 pages , quickly came under fire because connoisseurs of occult literature noticed that Blavatsky had used works by third parties and, in some cases, copied them without giving any source. While Olcott admitted some templates such as Éliphas Lévi and otherwise claimed that Blavatsky had obtained her information from the "astral light", the American orientalist and occult researcher William Emmette Coleman raised serious allegations after three years of research in his monumental occult library in 1895 because Blavatsky's main works Isis Unveiled , The Secret Doctrine and The Voice of the Silence consist largely of plagiarism . In Isis Unveiled alone, Coleman found 2,000 references from over 100 titles in occult literature, especially those of the 19th century, which she had copied. Bruce F. Campbell checked this, and Olcott later confirmed that Blavatsky's reference library consisted of only about 100 books, many of which were on Coleman's list. The mostly claimed sole authorship of Blavatsky had to be revised after Olcott's detailed descriptions of his activities as a co-author. In this regard, Goodrick-Clarke notes in his Blavatsky anthology that Blavatsky's lack of familiarity with the customs of science is out of the question and that the real meaning of Coleman's investigation is to list the sources in contemporary literature that it has drawn upon. In Isis Unveiled it was mainly to works by Samuel Fales Dunlap , Joseph Ennemoser , JS Forsyth , Eusèbe Baconnière-Salverte and anti-Semites Roger Gougenot des Mousseaux .

Fraud allegations

Blavatsky is accused from various quarters that the supernatural phenomena with which she gained credibility were based on sleight of hand and fraud. She is said to have adopted tricks that she had learned in her time as the assistant to the spiritualist Daniel Dunglas Home in her work as a spiritualist medium and used assistants to generate poltergeist noises and dressed up as ghostly ambassadors from the hereafter. In addition, there was the Coulomb affair in 1884 and the Hodgson Report in 1885 , but the SPR distanced itself from its results in 1986.

Fonts

- Isis Unveiled , 1877 (German: Isis Unveiled )

- The Secret Doctrine , 1888 (German: The Secret Doctrine )

- The Voice of the Silence , 1889 (German: The Voice of the Silence )

- The Key to Theosophy , 1889 (German: The Key to Theosophy )

- Nightmare Tales , 1892 (German: Höllen-Träume )

literature

- Daniel Caldwell: The Esoteric World of Madame Blavatsky. Insights into the Life of a modern Sphinx. Quest Books - Theosophical Publishing House, Wheaton IL 2000, ISBN 0-8356-0794-1 .

- Sylvia Cranston: HPB. The Extraordinary Life and Influence of Helena Blavatsky, Founder of the Modern Theosophical Movement. Tarcher / Putnam, New York 1993. ISBN 0-87477-688-0 .

- Jean Overton Fuller : Blavatsky and Her Teachers. An Investigative Biography. East-West Publications, London 1988, ISBN 0-85692-171-8 .

- Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke (Ed.): Helena Blavatsky. North Atlantic Books, Berkeley CA 2004, ISBN 1-55643-457-X (anthology with introductions by the editor).

- Ursula Keller , Natalja Sharandak: Madame Blavatsky. A biography. Insel-Verlag, Berlin 2013. ISBN 978-3-458-17572-8 .

- Marion Meade: Madame Blavatsky. The Woman Behind the Myth. Putnam's, New York NY 1980, ISBN 0-399-12376-8 .

- Leslie Price: Madame Blavatsky Unveiled? A New Discussion of the Most Famous Investigation of the Society for Psychical Research. Theosophical History Center, London 1986, ISBN 0-948753-00-5 .

- Hans-Jürgen Ruppert : Theosophy - on the way to the occult superman. Series Apologetic Topics 2. Friedrich Bahn, Konstanz 1993.

- Björn Seidel-Dreffke: The Russian literature at the end of the 19th and at the beginning of the 20th century and the theosophy EP Blavatskajas. Exemplary studies (A. Belyj, MA Vološin, VI Kryžanovskaja, Vs. S. Solov'ev). ISBN 3-89846-308-7 .

- Peter Washington: Madame Blavatsky's Baboon. Theosophy and the Emergence of the Western Guru. Seeker & Warburg, London 1993, ISBN 0-436-56418-1 .

- Gerhard Wehr : Helena Petrovna Blavatsky. A Modern Sphinx Biography. Pforte, Dornach 2005, ISBN 3-85636-160-X .

Web links

- German-language web links

- Literature by and about Helena Petrovna Blavatsky in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Helena Petrovna Blavatsky in the German Digital Library

- Blavatsky's Secret Doctrine online: Volume I (PDF, 3.6 MB) and Volume II (PDF, 4.8 MB)

- HP Blavatsky - A sketch of life

- HP Blavatsky - Life - Work - Effect

- Website dedicated to HP Blavatsky unveiled with introductory articles from Secret Doctrine and ISIS

- English-language web links

- Works by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky in Project Gutenberg ( currently not usually available for users from Germany )

- Link catalog on Helena Petrovna Blavatsky at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Blavatsky Study Center (With Photo Gallery)

- Blavatsky Net

- Books by HP Blavatsky at Theosophical University Press

- Biographical approach

- Collection of articles on HP Blavatsky

- Open Questions in Blavatsky's Genealogy (PDF; 1.1 MB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Walter Leifer: Weltprobleme am Himalaya . Marienburg-Verlag, Würzburg 1959, p. 169 .

- ↑ Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker: Time and knowledge . Hanser, Munich / Vienna 1992, p. 484 .

- ↑ James Webb: The Flight from Reason: Politics, Culture, and Occultism in the Nineteenth Century. marixverlag GmbH Wiesbaden; 1st edition 2009. p. 147.

- ^ A b Karl RH Frick: Light and Darkness. Gnostic-theosophical and Masonic-occult secret societies up to the turn of the 20th century , Volume 2; Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005; ISBN 3-86539-044-7 ; P. 259.

- ↑ Rudolf Passian: Light and shadow of esotericism. Droemersche Verlagsanstalt Th. Knaur Nachf., Munich 1991, p. 49.

- ↑ Sylvia Cranston and Carey Williams: HPB life and work of Helena Blavatsky founder of modern theosophy. Edition Adyar, Grafing 1995, ISBN 3-927837-53-9 , p. 46 f.

- ^ Gerhard Wehr : Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, a modern Sphinx - biography. Pforte, Dornach 2005, p. 19 f.

- ↑ Rudolf Passian: Light and shadow of esotericism. Droemersche Verlagsanstalt Th. Knaur Nachf., Munich 1991, p. 50.

- ^ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke : Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, pp. 2 f.

- ↑ Karl RH Frick: Light and Darkness. Gnostic-theosophical and Masonic-occult secret societies up to the turn of the 20th century , Volume 2; Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005; ISBN 3-86539-044-7 ; P. 259 gives the age difference as 43 years; According to Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 3, Nikifor Blavatsky was born in 1809, so the age difference would only be 22 years.

- ^ Gerhard Wehr: Helena Petrovna Blavatsky. A modern sphinx. Biography. Pforte, Dornach 2005, p. 24.

- ↑ Karl RH Frick: Light and Darkness. Gnostic-theosophical and Masonic-occult secret societies up to the turn of the 20th century , Volume 2; Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005; ISBN 3-86539-044-7 ; P. 259 gives the age difference as 43 years; According to Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 3, Nikifor Blavatsky was born in 1809, so the age difference would only be 22 years.

- ^ After Carl Kiesewetter: History of the newer occultism . New edition based on the original edition, Leipzig 1891–1895. Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2007; ISBN 978-3-86539-121-6 , p. 424, she had been divorced in 1851; according to Rosemary Guiley: The Encyclopedia of Magic and Alchemy . Infobase, New York 2006, p. 42, the marriage had never been divorced; the remarriage was made possible in 1875 by the death of Nikifors.

- ↑ Jeffrey D. Lavoie: The Theosophical Society: The History of a Spiritualist Movement . Brown Walker, Boca Raton, FL 2012, p. 23.

- ↑ Rudolf Passian : Light and shadow of esotericism. Droemersche Verlagsanstalt Th. Knaur Nachf., Munich 1991, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Lucetta Scaraffia: Lies and Sorcery. Helena Blavatsky in Mentana (1867) . In: Claire Gantet and Fabrice d'Almeida (eds.): Ghosts and Politics. 16th to 21st century . Wilhelm Fink, Munich 2007, p. 230.

- ^ A b Karl RH Frick: Light and Darkness. Gnostic-theosophical and Masonic-occult secret societies up to the turn of the 20th century , Volume 2; Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005; ISBN 3-86539-044-7 ; P. 262.

- ↑ Ursula Keller, Natalja Sharandak: Madame Blavatsky. A biography. Insel Verlag, Berlin 2013, pp. 84–86.

- ^ Edward T. James: Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary. 1607-1950. Harvard University Press 1974, p. 174.

- ↑ a b c d James A. Santucci: Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna . In: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (Ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism . Brill, Leiden 2006, p. 178.

- ^ Sylvia Cranston and Carey Williams: HPB life and work of Helena Blavatsky, founder of modern theosophy , Edition Adyar, Grafing 1995, ISBN 3-927837-53-9 , p. 453.

- ^ Marion Meade: Madame Blavatsky: The Woman Behind the Myth. Pp. 68-93.

- ↑ Horst E. Miers : Lexicon of secret knowledge. Goldmann Verlag, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-442-12179-5 . P. 115.

- ^ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 3.

- ↑ James Webb: The Flight from Reason: Politics, Culture, and Occultism in the Nineteenth Century. Marix Verlag GmbH Wiesbaden; 1st edition 2009. p. 148.

- ↑ a b c d Karl RH Frick: Light and Darkness. Gnostic-theosophical and Masonic-occult secret societies up to the turn of the 20th century , Volume 2; Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005; ISBN 3-86539-044-7 ; Pp. 259-260.

- ↑ Lucetta Scaraffia: Lies and Sorcery. Helena Blavatsky in Mentana (1867) . In: Claire Gantet and Fabrice d'Almeida (eds.): Ghosts and Politics. 16th to 21st century . Wilhelm Fink, Munich 2007, p. 230.

- ^ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 4.

- ↑ a b c James A. Santucci: Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna . In: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism , Brill, Leiden 2006, p. 177.

- ↑ Anette von Heinz: The great book of the secret sciences. Marix Verlag GmbH Wiesbaden 2005. p. 109.

- ^ K. Paul Johnson: The Masters Revealed: Madame Blavatsky and the Myth of the Great White Lodge , State University of New York Press, Albany 1994, p. 141; see also Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, pp. 5 f .; Lucetta Scaraffia: lies and sorcery. Helena Blavatsky in Mentana (1867) . In: Claire Gantet and Fabrice d'Almeida (eds.): Ghosts and Politics. 16th to 21st century . Wilhelm Fink, Munich 2007, p. 232.

- ↑ Anette von Heinz: The great book of the secret sciences. Marix Verlag GmbH Wiesbaden 2005. p. 109.

- ↑ James Webb: The Flight from Reason: Politics, Culture, and Occultism in the Nineteenth Century. marixverlag GmbH Wiesbaden; 1st edition 2009. p. 148.

- ↑ Karl RH Frick: Light and Darkness. Gnostic-theosophical and Masonic-occult secret societies up to the turn of the 20th century , Volume 2; Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005; ISBN 3-86539-044-7 ; P. 262.

- ^ Marion Meade: Madame Blavatsky: The Woman Behind the Myth. P. 73.

- ↑ Anette von Heinz: The great book of the secret sciences. Marix Verlag GmbH Wiesbaden 2005. p. 109.

- ↑ Rudolf Passian: Light and shadow of esotericism. Droemersche Verlagsanstalt Th. Knaur Nachf., Munich 1991, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Jean Overton Fuller: Blavatsky and Her Teachers. An Investigative Biography. East-West Publications, London 1988, p. 22; Lucetta Scaraffia: lies and sorcery. Helena Blavatsky in Mentana (1867) . In: Claire Gantet and Fabrice d'Almeida (eds.): Ghosts and Politics. 16th to 21st century . Wilhelm Fink, Munich 2007, pp. 221-234.

- ↑ Lucetta Scaraffia: Lies and Sorcery. Helena Blavatsky in Mentana (1867) . In: Claire Gantet and Fabrice d'Almeida (eds.): Ghosts and Politics. 16th to 21st century . Wilhelm Fink, Munich 2007, pp. 225 and 233 (here the quote).

- ^ Marion Meade: Madame Blavatsky: The Woman Behind the Myth. Chapter IV.

- ↑ James Webb: The Flight from Reason: Politics, Culture, and Occultism in the Nineteenth Century. marixverlag GmbH Wiesbaden; 1st edition 2009. p. 148.

- ^ Marion Meade: Madame Blavatsky: The Woman Behind the Myth. Chapter IV.

- ^ Edward T. James: Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary, Volumes 1-3: 1607-1950. Harvard Univ Pr Verlag (November 1974). P. 174.

- ^ Helmut Zander: Anthroposophy in Germany. Theosophical worldview and social practice 1884–1945 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-55452-4 . Volume I p. 80.

- ^ Gregor Eisenhauer : Charlatans. Ten case studies . Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-8218-4112-5 , pp. 197-223 ( Hans Magnus Enzensberger (Ed.): Die Andere Bibliothek 112). P. 206.

- ↑ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 4 f.

- ^ A b Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 5.

- ^ Gregor Eisenhauer: Charlatans. Ten case studies . Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-8218-4112-5 , pp. 197-223 ( Hans Magnus Enzensberger (Ed.): Die Andere Bibliothek 112). P. 204.

- ^ A b Ulrich Linse : Theosophy / Anthroposophy . In: Metzler Lexicon Religion. Present - everyday life - media . JB Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2005, vol. 3, p. 491.

- ↑ Wehr, p. 37.

- ^ Helmut Zander: Anthroposophy in Germany. Theosophical worldview and social practice 1884–1945 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-55452-4 . Volume I p. 81.

- ↑ Karl RH Frick: Light and Darkness. Gnostic-theosophical and Masonic-occult secret societies up to the turn of the 20th century , Volume 2; Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005; ISBN 3-86539-044-7 ; P. 262.

- ^ A b Karl RH Frick: Light and Darkness. Gnostic-theosophical and Masonic-occult secret societies up to the turn of the 20th century , Volume 2; Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005; ISBN 3-86539-044-7 ; Pp. 262-264.

- ↑ Rudolf Passian: Light and shadow of esotericism. Droemersche Verlagsanstalt Th. Knaur Nachf., Munich 1991, p. 52.

- ^ Helmut Zander: Anthroposophy in Germany. Theosophical worldview and social practice 1884–1945 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-55452-4 . Volume I pp. 78-84; Ursula Keller, Natalja Sharandak: Madame Blavatsky. A biography. Insel Verlag Berlin 2013. 131–132.

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Ruppert : Theosophy. On the way to the occult superman . Friedrich Bahn, Konstanz 1993, pp. 15-16.

- ↑ James A. Santucci: Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna . In: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (Ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism . Brill, Leiden 2006, p. 179 f.

- ^ Wouter J. Hanegraaff: Occult / Occultism , in: Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism , pp. 884-889, here p. 887.

- ↑ Heiner Ullrich: Rudolf Steiner: Life and Teaching , CH Beck, 2011, p. 35

- ^ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, pp. 7 f; Wehr, pp. 49-52.

- ↑ Karl RH Frick: Light and Darkness. Gnostic-theosophical and Masonic-occult secret societies up to the turn of the 20th century , Volume 2; Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005; ISBN 3-86539-044-7 ; P. 263.

- ↑ quoted in Wehr, p. 51.

- ↑ "to collect and diffuse a knowledge of the laws which govern the universe", quoted in Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky. North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 8.

- ^ Helmut Zander: Anthroposophy in Germany. Theosophical worldview and social practice 1884–1945 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-55452-4 . Volume I p. 78.

- ↑ Hans-Dieter Leuenberger: That is esoteric. Introduction to esoteric thinking. Verlag Hermann Bauer, Freiburg im Breisburg 1995, ISBN 3-7626-0621-8 , p. 114.

- ↑ Ursula Keller, Natalja Sharandak: Madame Blavatsky. A biography. Insel Verlag, Berlin 2013, p. 165.

- ↑ Ursula Keller, Natalja Sharandak: Madame Blavatsky. A biography. Insel Verlag Berlin 2013. pp. 164–165.

- ↑ James Webb: The Flight from Reason: Politics, Culture, and Occultism in the Nineteenth Century. Marix Verlag GmbH Wiesbaden; 1st edition 2009. pp. 154-155.

- ↑ Ursula Keller, Natalja Sharandak: Madame Blavatsky. A biography. Insel Verlag Berlin 2013. pp. 169–171.

- ^ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky, North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 11

- ↑ Karl RH Frick: Light and Darkness. Gnostic-theosophical and Masonic-occult secret societies up to the turn of the 20th century , Volume 2; Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005; ISBN 3-86539-044-7 ; P. 264.

- ↑ Karl RH Frick: Light and Darkness. Gnostic-theosophical and Masonic-occult secret societies up to the turn of the 20th century , Volume 2; Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005; ISBN 3-86539-044-7 ; Pp. 265-266.

- ↑ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 11 f.

- ^ A b Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 12.

- ↑ a b c James A. Santucci: Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna . In: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (Ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism . Brill, Leiden 2006, p. 181.

- ↑ a b c d Karl RH Frick: Light and Darkness. Gnostic-theosophical and Masonic-occult secret societies up to the turn of the 20th century , Volume 2; Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005; ISBN 3-86539-044-7 ; P. 265.

- ^ A b Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 10.

- ^ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: The occult roots of National Socialism , marixverlag GmbH 2009. pp. 25–26; René Freund: Brown magic? Occultism, New Age and National Socialism . Picus, Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-85452-271-1 . P. 18 f.

- ↑ Santucci, pp. 181f.

- ↑ Harald Lamprecht : New Rosicrucians. A manual. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-525-56549-6 . P. 168.

- ↑ a b James A. Santucci: Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna . In: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (Ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism . Brill, Leiden 2006, p. 182.

- ↑ Ursula Keller, Natalja Sharandak: Madame Blavatsky. A biography. Insel Verlag, Berlin 2013, pp. 229–232.

- ↑ James A. Santucci: Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna . In: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (Ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism . Brill, Leiden 2006, p. 182; Ursula Keller, Natalja Sharandak: Madame Blavatsky. A biography. Insel Verlag, Berlin 2013, pp. 242–246.

- ^ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 14; Vernon Harrison: HP Blavatsky and the SPR , 1986.

- ↑ a b Kocku von Stuckrad: What is esotericism? Beck, Munich 2004, SS 208.

- ↑ James A. Santucci: Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna . In: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (Ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism . Brill, Leiden 2006, p. 182 f.

- ↑ James A. Santucci: Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna . In: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (Ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism . Brill, Leiden 2006, p. 183.

- ↑ a b c James A. Santucci: Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna . In: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (Ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism . Brill, Leiden 2006, p. 184.

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Ruppert: Theosophy. On the way to the occult superman . Friedrich Bahn, Konstanz 1993, p. 16.

- ↑ Horst E. Miers: Lexicon of secret knowledge. Goldmann Verlag, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-442-12179-5 . P. 128.

- ↑ Karl RH Frick: Light and Darkness. Gnostic-theosophical and Masonic-occult secret societies up to the turn of the 20th century , Volume 2; Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005; ISBN 3-86539-044-7 ; Pp. 263-264.

- ↑ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: The Occult Roots of Nazism. Secret Aryan Cults and their Influence on Nazi Ideology . Tauris Parke, London 2005, p. 19.

- ↑ James Webb: The Flight from Reason: Politics, Culture, and Occultism in the Nineteenth Century. Marix Verlag GmbH Wiesbaden; 1st edition 2009. p. 150.

- ↑ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: The occult roots of National Socialism , marixverlag GmbH 2009. p. 24.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad : What is esotericism? Beck, Munich 2004, p. 204.

- ↑ Summaries in Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, pp. 14-17, and James A. Santucci: Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna . In: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (Ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism . Brill, Leiden 2006, p. 183.

- ↑ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky . North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 75.

- ^ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, pp. 1 f.

- ^ Ulrich Linse: Theosophy / Anthroposophy . In: Metzler Lexicon Religion. Present - everyday life - media . JB Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2005, vol. 3, p. 492.

- ^ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 2.

- ^ Sylvia Cranston: Helena Blavatsky. La straordinaria vita e il pensiero della fondatrice del movimento teosofico moderno . Milan, 1994, p. 260 f., Quoted from Lucetta Scaraffia: Läge und Zaubererei . Helena Blavatsky in Mentana (1867) . In: Claire Gantet and Fabrice d'Almeida (eds.): Ghosts and Politics. 16th to 21st century . Wilhelm Fink, Munich 2007, p. 231 f.

- ^ Hubertus Mynarek : Theosophical Societies . In: Evangelisches Kirchenlexikon . Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1996, vol. 3, col. 869.

- ^ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 16.

- ↑ Marcel Messing: Buddhism in the West. From ancient times to today. Kösel-Verlag GmbH & Co 1997. pp. 129-131.

- ^ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, pp. 15 f.

- ↑ Also on the following Isaac Lubelsky: Mythological and Real Race Issues in Theosophy . In: Olav Hammer, Mikael Rothstein (Eds.): Handbook of the Theosophical Current . Brill, Leiden 2013, pp. 335-355, the citation pp. 337-347.

- ↑ Horst E. Miers: Lexicon of Secret Knowledge (= Esoteric. Vol. 12179). Original edition; and 3rd updated edition, both Goldmann, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-442-12179-5 , pp. 412-417, p. 653.

- ^ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, pp. 3-6.

- ^ Helmut Zander: Anthroposophy in Germany. Theosophical worldview and social practice 1884–1945 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-55452-4 . Volume I p. 95.

- ^ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 6.

- ↑ Horst E. Miers: Lexicon of secret knowledge. Goldmann Verlag, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-442-12179-5 . P. 115.

- ↑ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: The occult roots of National Socialism , marixverlag GmbH 2009. P. 116.

- ↑ K. Paul Johnson: The Masters Revealed: Madame Blavatsky and the Myth of the Great White Lodge . State University of New York Press, Albany 1994, pp. Xii and passim.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad : What is esotericism? Beck, Munich 2004, p. 208.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: What is esotericism? Beck, Munich 2004, SS 197.

- ↑ René Freund : Brown magic? Occultism , New Age and National Socialism . Picus, Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-85452-271-1 . P. 14.

- ↑ Harald Lamprecht: New Rosicrucians. A manual. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-525-56549-6 . P. 169.

- ^ Ulrich Linse: Theosophy / Anthroposophy . In: Metzler Lexicon Religion. Present - everyday life - media . JB Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2005, vol. 3, p. 492.

- ↑ Werner Thiede : Who is the cosmic Christ? Career and change in the meaning of a modern metaphor (church - denomination - religion 44). Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht Verlag, Göttingen 2001. pp. 129–148.

- ↑ René Freund : Brown magic? Occultism , New Age and National Socialism . Picus, Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-85452-271-1 . Pp. 19-20.

- ^ Sylvia Cranston: Life and work of Helena Blavatsky , extensively documented on pp. 543-582.

- ↑ René Freund: Brown magic? Occultism, New Age and National Socialism . Picus, Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-85452-271-1 . Pp. 19-20.

- ↑ Martin Brauen: Traumwelt Tibet: Western illusions. Publishing house Paul Haupt Berne, Bern; Stuttgart; Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-258-05639-0 . Pp. 38-40.

- ↑ Horst E. Miers: Lexicon of Secret Knowledge (= Esoteric. Vol. 12179). Original edition; and 3rd updated edition, both Goldmann, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-442-12179-5 , p. 116.

- ↑ William Emmette Coleman: The Sources of Madame Blavatsky's Writings . In: Vsevolod Sergyeevich Solovyoff: A Modern Priestess of Isis . Longmans, Green, & Co, London 1895, pp. 353-366 ( online , accessed January 18, 2014); James Webb: The Age of the Irrational. Politics, Culture & Occultism in the 20th Century. Marix, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-86539-152-0 , p. 276; Martin Brauen : dream world Tibet: western illusions. Publishing house Paul Haupt Berne, Bern; Stuttgart; Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-258-05639-0 . Pp. 39-40 .; Linus Hauser , Critique of Neomythic Reason , Schöningh, Paderborn 2005, p. 329.

- ↑ Helmut Zander: Social Darwinist race theories from the occult underground of the empire . In: Uwe Puschner , Walter Schmitz, Justus H. Ulbricht (eds.): Handbook on the “Völkische Movement” 1871–1918 . Munich 1996, p. 229 f .; the original quotations from Helena Blavatsky: The Secret Doctrine , Vol. 1, pp. 168 and 185 ( online , accessed on January 31, 2014).

- ↑ Jürgen Osterhammel: The transformation of the world. A nineteenth century story . CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 1154; The theologian Hans-Jürgen Ruppert attributes an "occult race theory" to Blavatsky and refers to several quotations from the 2nd volume of her secret doctrine . Ruppert: Theosophie , 1993, p. 65f. Here Blavatsky stated that some "lower races" (including Tasmanians and Bushmen) "are now represented on earth by a few miserable extinct tribes and the great human-like apes". She saw the extinction of these lower races as "a karmic necessity."

- ^ "Besides its racial emphasis, theosophy also stressed the principle of elitism and the value of hierarchy". Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: The Occult Roots of Nazism. Secret Aryan Cults and their Influence on Nazi Ideology . Tauris Parke, London 2005, p. 20.

- ↑ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: In the shadow of the black sun: Aryan cults, Esoteric National Socialism and the politics of demarcation Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2002, ISBN 978-3-86539-185-8 , p. 170.

- ↑ George L. Mosse: History of Racism in Europe . Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1990, p. 119.

- ↑ Linus Hauser: Critique of the neo-mythical reason. Volume 1: People as gods of the earth 1800–1945 . Schöningh, Paderborn 2004, p. 326 (here the quote) –328.

- ↑ James A. Santucci: The Notion of Race in Theosophy . In: Nova Religio. The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions , 11, Issue 3 (2008), p. 51.

- ^ "The book was full of notes, remarks, and theories which a modern reader would most certainly define as racist." Isaac Lubelsky: Mythological and Real Race Issues in Theosophy . In: Olav Hammer, Mikael Rothstein (Eds.): Handbook of the Theosophical Current . Brill, Leiden 2013, pp. 335-355, the quotation p. 343.

- ^ Gillian McCann: Vanguard of the New Age. The Toronto Theosophical Society 1891-1945 . McGill-Queens University Press, Montreal 2012, p. 70.

- ^ Helmut Zander: Anthroposophy in Germany. Theosophical worldview and social practice 1884–1945 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-55452-4 . Volume I pp. 85-86; Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 50 and p. 8 f .; James A. Santucci: Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna . In: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (Ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism . Brill, Leiden 2006, p. 183 f.

- ↑ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky , North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, p. 52: “an argument about Blavatsky's scholarship is beside the point”.

- ↑ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: Helena Blavatsky . North Atlantic Books, Berkeley 2004, pp. 50-52.

- ↑ James Webb: The Flight from Reason: Politics, Culture, and Occultism in the Nineteenth Century. marixverlag GmbH Wiesbaden; 1st edition 2009. p. 148.

- ^ Gregor Eisenhauer: Charlatans. Ten case studies . Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-8218-4112-5 , (Hans Magnus Enzensberger (Hrsg.): Die Andere Bibliothek 112). P. 208 f. And p. 213 f.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Блаватская, Елена Петровна; Blawatzkaja, Jelena Petrovna; Hahn, Helena von; Blavatzki, Helena |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian-American occultist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 12, 1831 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Ekaterinoslav , New Russia , Russian Empire |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 8, 1891 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | London |