Senate of Canada

| Parliament Buildings on Parliament Hill . The plenary hall of the Senate is located in the right part of the building | Senate meeting room |

|---|---|

|

|

| Basic data | |

| Seat: | Center Block, Parliament Hill , Ottawa |

| MPs: | 105 |

| Current legislative period | |

| Chair: |

Speaker George Furey ( Independent ) |

| Distribution of seats: |

|

| Website | |

| Canadian Parliament website | |

The Canadian Senate ( English Senate of Canada , French Le Sénat du Canada ) is, like the Canadian monarch and the House of Commons (English House of Commons , French Chambre des communes ), a part of the Canadian Parliament .

The Canadian Parliament is modeled on the British Westminster system . In line with this, the Senate is called the "upper house" (English. Upper House , fr. Chambre haute ), the House of Commons as "the House" (English. Lower House , fr. Chambre basse ), respectively. Although this designation is in line with the protocol's ranking, it does not make any statement about the political significance. In fact , the House of Commons is far more influential. Although the approval of both chambers is formally required in order to pass a law, the Senate only rejects a bill in exceptional cases. The Senate has no power to appoint or remove the Prime Minister and the other ministers. According to the constitution, tax laws must always begin their way in the House of Commons.

The Senate has 105 members appointed by the Governor General on the recommendation of the Canadian Prime Minister. The seats are divided by region. Since the number of senators per region has remained the same since 1867, there are now large disproportionalities in the representation in relation to the number of inhabitants. The senators do not have a fixed term of office, but can hold office up to the age of 75.

The Canadian Parliament goes back to the Constitutional Act of 1867 . Reform proposals for the Senate are almost as old as the Senate itself. However, major reforms have always failed due to the problems of a constitutional amendment that is necessary for this. The seat of parliament and thus also of the Senate is the Canadian capital Ottawa .

Position in the political system

Legislative tasks

In theory, the two chambers of parliament have almost identical legislative rights: the consent of both chambers is necessary for a law to come into force. Exceptions are tax laws and constitutional amendments. Following British tradition, the right of initiative in tax laws rests with the House of Commons. While this follows purely from common law in the United Kingdom , the Canadian Constitutional Fathers oriented themselves on the USA on this point : Article 53 of the constitutional law of 1867 explicitly stipulates the privilege of the House of Commons. Whether the Senate has the right to influence tax legislation at all cannot be inferred explicitly from the constitutional text. The Senate itself takes the position that it has the right to intervene as long as these interventions do not increase the tax burden caused by a law. The House of Commons never challenged the Senate interpretation.

According to Article 47 (1) of the 1982 Constitutional Act , the House of Commons can override the Senate in the event of constitutional amendments. However, before it can vote again, 180 days must elapse after the failed vote. In all other areas of law, although the Senate theoretically has the power to stop laws, it only rarely exercises this against the directly democratically legitimized lower house. Although a bill can be tabled in either House of Parliament, most bills come from the House of Commons. However, since the Senate's schedule is more flexible and allows for more extensive debates, the government may send a particularly complex law to the Senate first.

Often the Senate is more concerned with the details than with the basic lines of a bill and makes numerous minor amendments, which are then usually accepted by the House of Commons. However, many bills reach the Senate at the end of the session, so that the Senate in fact no longer has time to examine their content. Although the senators regularly complained about being overlooked, the bills have ultimately nodded their approval for decades.

Until the 1980s, Senators believed Senator Keith Davey ( Liberal , Ontario ) said in 1986: “Although we are not elected, we can block any and all legislative initiatives from the elected House of Commons. Not that, given our unelected status, we would ever use our powerful veto. If we did it, it would be taken from us immediately; and that's how it should be. "

Since 1985 the Senate has been more actively involved in legislation. If the Senate did not even make use of its veto right between 1961 and 1985, it has since then started to use it more often. He opposed the free trade agreement with the USA as well as the Goods and Services Tax (GST; French Taxe sur les produits et services , TPS ), the first nationwide sales tax in Canada. In the 1990s, the Senate rejected four bills: C-43, which aimed to restrict abortion rights, C-93, which aimed to consolidate federal agencies, C-28, privatizing Lester B. Pearson Airport in Toronto , and C-220 , which deals with profits from authors' rights on crimes actually committed.

A role normally incumbent on the judicial system was performed by the Senate until the Divorce Act of 1968. In Canada, divorces were not possible in all provinces until 1930 - after that only in Québec and Newfoundland - not in court, but only by a parliamentary decree. The Senate established its own divorce committee in 1889. Between 1945 and 1968, for example, he broke an average of 340 marriages a year.

Government control

The Senate's control over the government is severely limited. Above all, he does not have the power to prematurely end the term of office of a prime minister or minister. Although cabinet members can theoretically come from either chamber, most modern Canadian cabinets are composed almost entirely of members of the lower house. Normally, only a minister sitting in the Senate: The government leader in the Senate (Engl. Leader of the Government in the Senate , fr. Du gouvernement au Sénat Leader ) - a minister who is specifically tasked to ensure cooperation with the Senate.

In rare cases, the government also appoints ministers from the Senate. The most recent example is Michael Fortier , who as Senator for Montreal was also Minister for Public Works and Services. Prime Minister Stephen Harper appointed him on February 6, 2006 because his minority government had no elected representatives from the region. Fortier resigned before the 2008 election to run for the House of Commons, but ultimately unsuccessfully.

Members of the Senate

Regional composition

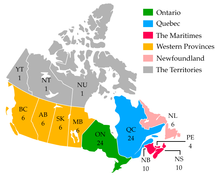

According to the Canadian Constitution , each province or territory can have a certain number of senators. The constitution divides Canada into four regions, each with 24 senators: the maritime provinces (ten each for Nova Scotia and New Brunswick , four for Prince Edward Island ), western Canada (six each for Manitoba , British Columbia , Saskatchewan and Alberta ), Ontario and Québec . Québec is the only province in which the senators are assigned to specific districts within the province - originally this was set up to ensure a proportional representation of English- and French-speaking senators. Newfoundland and Labrador has six senators and is not part of any of the regions. The three territories, the Northwest Territories , Yukon and Nunavut, each send a senator.

As a result of this arrangement, the three fastest growing provinces - Ontario, British Columbia and Alberta - are now seriously underrepresented in the Senate, while the maritime provinces are also seriously overrepresented. For example, British Columbia has six senators with a population of four million, while Nova Scotia has ten senatorial posts with less than one million residents. The only province where the population and the proportion of senators are roughly the same is Québec.

| Province or territory | Number of senators | Population per Senator (2001 census) |

|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 6th | 495,801 |

| British Columbia | 6th | 651.290 |

| Manitoba | 6th | 186,597 |

| New Brunswick | 10 | 72,950 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 6th | 85,488 |

| Nova Scotia | 10 | 90,801 |

| Northwest Territories | 1 | 37,360 |

| Nunavut | 1 | 26,745 |

| Ontario | 24 | 475.419 |

| Prince Edward Island | 4th | 33,824 |

| Quebec | 24 | 301,562 |

| Saskatchewan | 6th | 163.156 |

| Yukon | 1 | 28,674 |

Since 1989, residents of Alberta have been voting senators-in-waiting to support their demand for directly elected senators. These elections are non-binding, however, and so far the Governor General has only actually sent two of them to the Senate. Brian Mulroney proposed the elected Stan Waters in 1990 . But Waters died in 1991, one year after taking on the mandate. The second was Bert Brown , elected in 1998 and 2004, and finally appointed in 2007 on the recommendation of Stephen Harper.

Article 26 of the Constitutional Act of 1867 allows the Canadian monarch to appoint four or eight additional senators. The Prime Minister suggests one or two senators from each region. So far, the Prime Minister has only successfully used the law once: in 1990, Brian Mulroney needed a conservative majority in the Senate to pass the law on nationwide sales tax. He wanted to achieve this by appointing eight additional senators. Queen Elizabeth II accepted his suggestion, placing responsibility for the appointment with the Prime Minister, who is directly accountable to the House of Commons. In 1874, on the advice of the British government , Queen Victoria rejected Alexander Mackenzie's proposal for additional senators .

Senators

The governor general appoints the senators on behalf of the queen. In fact, he is sticking to the "recommendations" made by the Prime Minister. Practice shows that a large number of senators are former ministers, former provincial premiers or other formerly influential politicians. The Constitutional Act of 1867 stipulates the conditions a senator must meet. It excludes non-citizens of Canada as well as anyone under the age of 30. Senators must be resident in the province for which they are appointed.

Due to the appointment procedure, new senators come almost exclusively from the party of the incumbent Prime Minister or are at least close to it. The liberal Prime Minister Paul Martin (2003-2006) attempted a slight break with this tradition . He was of the opinion that huge liberal majorities in the Senate seriously compromised its constitutional task and thus represented a serious democratic deficit. Martin appointed five of 14 senators in his term from among the opposition. Before that, only two prime ministers had appointed opposition senators in greater numbers, albeit in a far smaller proportion than Martin: Pierre Trudeau (1968–1979; 1980–1983) appointed eight of 81 senators from among the opposition, Canada's first prime minister John Macdonald (1867–1873; 1878–1891) nine of 91. All other prime ministers combined only appointed nine opposition senators.

The constitutional law sets certain minimum limits on the assets of the senators. A senator must be at least land in the value of 4,000 CAD in the province have, he represents. In addition, he must have mobile and immovable assets that exceed his debt by at least $ 4,000. Originally, these conditions were in law to ensure that only the economic and social elite had access to senatorial office. Since the financial requirements were never increased, however, they have decreased drastically since 1867 due to inflation. Back then, CAD 4,000 was roughly the equivalent of CAD 175,000 to 200,000 today. Nevertheless, in 1997 the Roman Catholic nun Peggy Butts had problems becoming a senator. She had sworn an oath of poverty and therefore had no personal assets at all. The situation could only be resolved when her order gave her a small piece of land.

Until the 1920s, only men were appointed to the Senate. In 1927 five women (" The Famous Five ") asked the Supreme Court to state whether women can generally become senators. Specifically, they asked whether the "persons" referred to in the British North America Act ("The Governor General should ... appoint qualified persons to the Senate; and ... every person so appointed should become a member of the Senate and a Senator") also include women are meant. In Edwards v. Canada (Attorney General) , now known as the "Persons Case," the Supreme Court unanimously decided that only men could become senators. The women took their request to the Justice Committee of the Privy Council in London, then the highest court for the British Empire , which female senators considered constitutional. Four months later, the government of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King recommended the appointment of Canada's first female senator, Cairine Wilson, to Ontario.

Originally, senators held office for life. Since the British North America Act of 1965, they are only allowed to serve until they have reached the age of 75. A senator automatically loses his seat if he does not attend the Senate for two consecutive parliamentary sessions. Likewise, a senator who is found guilty of high treason or other serious crimes, who is bankrupt or otherwise loses his or her original qualifications, loses his mandate.

The annual salary in 2006 was $ 122,700, with senators allowed to have additional income from other public offices. Senators are directly above members of the House of Commons in the protocol order of Canada . Senators are on average older than members of the lower house and usually have already gained parliamentary experience. In addition, many prime ministers use the Senate for a broad representation of the population groups, so that the proportion of women as well as that of minorities is higher than in the lower house.

List of Senators

organization

Functionaries

The chairman of the Senate is the speaker (English Speaker , French Président du Sénat ). He is appointed by the Governor General on the proposal of the Prime Minister. He is assisted by a “pro tempore” spokesperson, who is elected by the Senate at the beginning of each parliamentary session. If the speaker does not take part in a meeting, the speaker takes the presidium pro tempore. According to the Parliament of Canada Act of 1985, the speaker himself can also appoint other senators to temporarily represent him.

The speaker chairs the meetings and calls on the individual senators to make their contributions. If a senator believes that the Senate's rules of procedure have been violated, he can bring a "point of order" (French point d'ordre ) to the hearing, which the speaker decides. However, the Senate as a whole can override this decision. While chairing the meeting, the speaker should remain impartial, although he is still a member of his party. Like any other senator, he has his right to vote. The current speaker is Noël A. Kinsella .

The government appoints a senator who is responsible for representing its interests in the Senate, the government leader in the Senate . The senator appointed by the prime minister (currently Marjory LeBreton ) has a ministerial rank in the cabinet in addition to his mandate. He sets the agenda of the body and tries to involve the opposition in the legislation. His opponent in the opposition is the opposition leader in the Senate (currently: Celine Hervieux-Payette ), who is appointed by the opposition leader in the lower house . Should the majority party in the lower house form the opposition in the Senate, as for example between 1993 and 2003, the faction of the Senate opposition independently appoints its leader.

Other officials who are not senators are the secretary (English: clerk , French: greffier ), the deputy secretary (English: Deputy Clerk , French: greffier adjoint ), the legal secretary (English: Law Clerk , French: greffier de droit ) , as well as various other secretaries. They advise the speaker and the senators on the rules of procedure and the course of the Senate meetings. The Usher of the Black Rod (French: Huissier de la Verge Noire ) is responsible for order and security within the Senate Chamber. He carries a ceremonial black ebony staff from which his name is derived. The Director General of Parliamentary Precinct Services (French: Directeur général des services de la Cité parlementaire ) is responsible for security on the entire parliamentary grounds .

procedure

For most of the Senate's history, the internal process was very informal. It was mainly based on the trust in a "gentlemanly" behavior of all involved. After the political disputes in the Senate became more violent in the 1980s, the Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney was finally able to enforce a much more restrictive by-law. It gave his political opponents fewer opportunities to act against the Senate majority. Debates in the Senate usually still tend to run less along party lines, to be less confrontational in style and to end in consensus far more often than in the House of Commons.

The Senate meets from Monday to Friday. The debates are public and are published verbatim in the “Debates of the Senate” or the “Débats du Sénat”. Unlike in the House of Commons, there are usually no live broadcasts of the meetings. However, if the Senate deals with issues of particular public interest, it can allow them.

The order of speech results from the order in which the senators rise to speak on the subject. The chairman of the meeting decides in confusing cases, but this decision can be overruled by the Senate itself. Motions must be brought up by one senator and supported by another before they can be debated.

The constitutional law of 1867 stipulates the quorum for at least 15 senators present, including the chairman of the session. Each senator can request the chairman of the session to determine the quorum. If this is not the case, the president can use a bell to call on other senators in the parliament building to come into the meeting room. If even then 15 senators do not meet, the president has to postpone the meeting to the next day.

Senators can debate in either English or French. They must direct their speech to the full Senate by the Senate members "honorable senators" (English: honorable senator : French honorables sénateurs address). Individual senators cannot address them directly, but have to mention them in the third person. Each senator is only allowed to speak once on a topic. The only exception is a senator who has made an important motion, proposed an investigation, or introduces a law; he has the right to an answer, so that he can speak again at the end of the debate. The speaking time is generally limited. The exact limit depends on the subject of the debate, but is usually set at 15 minutes. Government and opposition leaders are not subject to these time restrictions. Speaking time can be further limited by a corresponding resolution during a debate. The Senate can also decide to end the debate immediately and go straight to the vote.

The first vote is taken orally. The session president asks the voting question and the senators answer either “Yea” (for) or “Nay” (against). The president of the meeting then announces the result of the vote. If at least two senators doubt the evaluation, another vote follows. In this "division" (French: vote par appel nominal ), only those who vote in favor stand up and the secretary writes down their names. After that, the same thing happens with the senators who reject the proposal. The abstentions then follow in the last course. In all cases, contrary to the usual practice, the speaker takes part in the vote. If a vote ends in a draw, the proposal is deemed to have failed. If no 15 members vote, the quorum is deemed not to have been met and the vote is therefore invalid.

The formal opening of parliament takes place at the beginning of each session in the Senate Hall in front of the members of both chambers of parliament. During the ceremony, the Governor General will deliver the speech from his seat in the hall , in which he will present the government's program for the coming session. Should the Queen be in Canada during the opening of Parliament, she too can deliver the speech from the throne.

Committees

The Canadian Parliament is a committee parliament. Parliamentary committees discuss bills in detail and propose changes. Other committees oversee the work of government agencies and ministries.

The largest committee is the "Committee of the Whole" (English: Committee of the Whole , French: comité plénier ), which consists of all senators and meets in the plenary chamber. In contrast to official plenary sessions, different, more liberal rules of procedure apply when this committee meets - for example, there is no limit to the number of speeches a senator can make on an item on the agenda. The Senate can dissolve itself into the committee of the whole for various reasons: to discuss a law in detail or to hear statements. For example, the Senators ask many future Senate officials about their qualifications before taking office on the Committee of the Whole.

The Senate's standing committees each oversee a specific policy area. There the senators discuss the upcoming bills. They also investigate certain circumstances on behalf of the Senate and report their results to the Chamber; they can both hold hearings and collect evidence. The standing committees have between nine and 15 members, depending on the topic, and elect their own chairmen.

Temporary committees (English: Special Committees , French: comités spéciaux ) are appointed ad hoc by the Senate to deal with a specific topic. The number of members varies depending on the committee, but the composition should roughly reflect the composition of the entire parliamentary chamber. You can deal with individual laws (such as the Committee on the Anti-Terrorism Act (C-36), 2001) or entire topics (such as the Committee on Illegal Drugs).

Joint committees (English: Joint Committees , French: comités mixtes ) consist of senators and members of the lower house. They only existed again since the Senate began to develop independent political activity in the 1980s. There are currently two joint committees: the joint regulatory review committee, which deals with legislative projects delegated to it, and the joint parliamentary library committee, which advises the spokespersons of the Senate and the lower house on the management of the library. The Canadian Parliament as a whole can also convene temporary joint committees that function similarly to the Senate's temporary committees.

history

1867–1984: Timid activity

The Senate was created in 1867 by the first British North America Act (subsequently renamed the Constitutional Act of 1867 ). The Parliament of the United Kingdom united the Province of Canada (Québec and Ontario) with Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to form the new Dominion Canada. The newly created Canadian Parliament was modeled on the British Parliament and most Canadian provincial parliaments in two chambers. The Constitutional Fathers decided against a directly elected Senate because, in their opinion, this only functioned as a doubling of the lower house in the provinces and could not take a position of its own. Originally the Senate had 72 seats, in which Ontario, Québec and the Maritime Provinces each made up a third of the representatives.

In this division, the Senate should assume the role of the House of Lords in the British Parliament: it should represent the social and economic elite. According to the then Canadian Prime Minister John Macdonald, it was a chamber of "sober reflection" that would offset the democratic excesses of an elected lower house. He would also represent the regions on an equal footing.

The Senate played no active partisan role for most of its history. Situations where the Senate blocked a bill that had successfully passed the House of Commons only arose at intervals of several years. In 1875 the Senate prevented the construction of a railway from Esquimalt to Nanaimo , British Columbia. In 1913 he stopped payments to the Navy. The majority of the Senate believed that the voters should decide the then controversial issue in a new election. For decades, the liberals had the majority in the lower house, the government, and through the prime minister's proposals, the clear majority in the senate. That didn't change until 1984 when the Progressive Conservatives won the election and the Senate was suddenly in partisan opposition. After a landslide victory, the Conservatives had the largest government majority in Canadian history, with 211 of the 282 seats in the lower house. At the same time, this was the first conservative election victory since 1963. Of the then 99 senators in 1984, 73 were members of the Liberals. The new opposition leader in the Senate, Allan MacEachen , announced that he would lead a determined opposition to the government from there.

1984–1991: The opposition forms

At a time when the House of Commons was barely able to show a functioning opposition and debates and disputes there were accordingly short, the Senate developed unexpected activity. The arguments began in 1985 when the Senate long refused to approve Bill C-11 on new debt because the law did not say what the money should be used for. The press criticized him for this, as financial matters belong in their opinion in the lower house. Between July 1986 and November 19, 1987, a bill on the health system shuttled between the Senate and the House of Commons. The House of Commons refused to accept the Senate's proposed amendments, the Senate refused to accept the law in its original form. Finally, since the liberal senators were of the opinion that the lower house had the higher legitimacy, they abstained. The bill passed 27: 3 with 32 abstentions and numerous absent senators. In 1988, the Senate finally refused to approve the Canadian-American free trade agreement with the USA until the House of Commons was confirmed in its position by a new election. After the Conservatives under Prime Minister Mulroney won the 1988 elections, the Liberals approved the law.

In 1990 the contrast worsened when the Mulroney government wanted to introduce nationwide sales tax. It took nine months of discussion in the House of Commons alone and the Senate was unwilling to approve. Mulroney took advantage of a largely unknown constitutional article on September 27th that allowed him to appoint eight additional senators, narrowing the majority in the chamber in his favor. As a result, the Liberals took advantage of every opportunity in the Rules of Procedure and began a long-running filibuster . At times, this procedure was "parliamentary terrorism" for Mulroney. During the dispute, the Liberals sank to an all-time low in opinion polls, but Mulroney's reputation also fell. Parliament finally passed the law on December 13th. The senators then had to work through the Christmas break to do the work that had piled up during the sales tax debate.

Since 1991: the government lost its vote

Despite the conservative majority, the government lost votes for the first time after 1991. A law designed to tighten abortion law resulted in a 43:43 on January 31, 1991, so it couldn't go into effect. If this vote was still carried out according to freedom of conscience and without party pressure, enough conservative senators were defective in 1993 to prevent a large-scale administrative reform (Bill C-93). The reform should dissolve and merge several government agencies. The attempt to merge the Canada Council, which promotes art, with the Social Sciences and Humanities Council, which is responsible for the humanities and social sciences, met with particular opposition from both artists and scholars. The vote ended in a draw on June 3, 1993, which meant a rejection.

In 1993 Brian Mulroney resigned as prime minister, his successor Kim Campbell lost the elections scheduled by her on October 25, 1993 like a landslide and the progressive conservative party shrank to two seats in the lower house. The new liberal Prime Minister Jean Chrétien now had to deal with a conservative majority in the Senate. In 1994 the Senate promptly announced that it would reject a change in electoral law by the Liberals, so the government withdrew the law before the vote.

The clashes over Pearson International Airport in Toronto, Canada's most important commercial airport, were much more violent. One of Chrétien's most important campaign promises was to reverse Mulroney's privatization of the airport. The Senate refused. The law shuttled between the chambers of parliament between July 7, 1994 and June 19, 1996. The vote ended 48:48, which means that this law also did not come into force. With the threat of appointing additional senators and getting an identical law through the Senate with the new majority, Chrétien succeeded in forcing the targeted buyers to withdraw from the purchase agreement in exchange for compensation. Several other laws did not even come to a vote in the Senate because the government withdrew them beforehand. The era of an oppositional Senate did not end until Chrétien appointed two new Senators in April 1997. This clearly tipped the majority in favor of the liberals. As a result, the House of Commons and Senate majorities were identical again by February 2006. After the Conservatives won again in 2006, they vigorously made further attempts to reform the Senate.

Senate reform

Concepts

Proposals for a reform of the Senate have been a regular topic of discussion since the Senate was founded. All Canadian provinces have already abolished their second chambers. As early as 1947, in his influential study of the Canadian system of government , the scientist MacGregor Dawson described the Senate as “so clumsy and sluggish that it only seems capable of fulfilling the most formal functions”, “it has not fulfilled the hopes of its founders, and one does It is good to remember that these hopes were not particularly high from the start. ”The first reform was the constitutional law of 1965, which set a maximum age for senators of 75 years.

In particular, most of the proposals focused on changing the appointment process. However, they did not gain support from the wider public until the 1980s, after the Senate began to gain political influence. In addition, it was the 1982 constitutional law that made it possible for Canadians to make decisive changes to their constitution without going through the British Parliament.

The first known example of widespread resentment against the Senate was the reaction to the National Energy Program , which Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau implemented in 1980 against vehement opposition in Western Canada. The law passed the Senate without resistance, as most of the senators had been appointed by Trudeau's predecessor, also a member of the Liberal Party . In Western Canada, discontent with the Senate first reached momentum. Politicians in Alberta protested against their low number of senators in relation to the size of the population and called for a three-E Senate ( elected - elected; equal - Gleich (legitimate representation); effective ). Proponents hoped that equal representation of all provinces would protect the interests of smaller provinces against Ontario and Québec. However, a distribution according to this pattern would not have guaranteed equal representation per inhabitant: Ontario, for example, has about 100 times as many inhabitants as Prince Edward Island; a provincial senator would have represented only one-hundredth of the population that an Ontario senator would have represented.

Attempted constitutional changes in 1985, 1987 and 1992

After his problems with the C-11 law in 1985, the Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney attempted to remove the Senate's say over tax laws. The attempt to amend the constitution petered out after a brief discussion: the parliaments of both Manitoba and Québec had made it sufficiently clear that they would not support the constitutional amendment: Manitoba because it would only support a complete abolition of the Senate, Québec because it did not support the constitutional law of 1982 recognized, on whose provisions the whole procedure was based.

In 1987, Mulroney proposed the Meech Lake Accord (French Accord du lac Meech ), a series of constitutional amendments that gave provincial governments the right to nominate senators from which the federal government would have to choose. Again he failed to win the support of the provincial parliaments. The following Charlottetown Accord (French Accord de Charlottetown ) of 1992 provided for each province to be represented by an equal number of senators - either directly elected or determined by the provincial parliaments. Mulroney did not try the way through the provincial parliaments, but had a referendum held. The Canadians rejected the constitutional amendment on October 26, 1992 with 54.3% to 45.7%, with the opponents achieving particularly good results in Québec and Western Canada. There, the Bloc Québécois (Québec) and the Reform Party (Western Canada) criticized in their major campaigns the insufficient scope of the changes that would ultimately only consolidate the power of the elites in Ottawa.

Current developments

Positions

The New Democratic Party and the Bloc Québécois are calling for the Senate to be abolished. The Prime Minister of Ontario, Dalton McGuinty , has also spoken out in favor of dissolving the Chamber. The Liberal Party has no official stance on Senate reform; the Conservative Party supports the direct election of senators.

Harper plan

Prime Minister Stephen Harper introduced the Senate S-4 Bill on May 30, 2006, which would limit the term of office of the new Senators to eight years. In addition, before taking office, he promised to hold elections to fill vacancies in the Senate. In contrast to previous reform attempts, he wanted to achieve this goal without changing the constitution. According to his plan, the Prime Minister will officially propose the election winners to the Governor General.

In December, he introduced Bill C-43 on "Consultation of Voters .. Relative to Senator Appointments". After that, Canadians elect their senators at the same time as the federal or provincial elections. according to the preference voting system . Due to the constitution, however, the result is not binding. It is still the prime minister's decision-making power to actually propose the election winners to the governor general. The law does not change the composition by provinces within the Senate.

Murray-Austin Amendment

To change the composition of the Senate, Senators Lowell Murray ( PC - Ontario ) and Jack Austin ( Liberal - British Columbia ) proposed a constitutional amendment on June 22, 2006. The Senate would then be increased to 117 seats and the number of senators from Western Canada increased. British Columbia would become an independent region, the current six seats of the province would be divided among the other western Canadian provinces. After the constitutional amendment, British Columbia would have twelve seats, Alberta ten, Saskatchewan seven and Manitoba seven instead of six each. Likewise, the number of additional senators that the queen can appoint increased from four or eight to five or ten. A Senate Special Committee on Senate Reform endorsed the proposal on October 26 and referred the issue back to the Senate as a whole. However, the Senate has not passed a resolution and now that the three-year period for constitutional amendments has expired, the draft has become obsolete.

Seat

The Senate meets on Parliament Hill (French: Colline du Parlement ) in Ottawa , Ontario . The Senate Chamber is informally called the “red chamber” in reference to the red fabric that dominates the room in terms of color. Its interior design stands out from the green of the lower house. The Canadian Parliament follows the color scheme of the British Parliament, in which the House of Lords meets in a luxurious room with a red interior, while the House of Commons debates in a barely green room.

In the British parliamentary tradition, the seats of the ruling and opposition parties face each other along a central aisle. The speaker's seat is at one end of the aisle, with the desk for the secretaries directly in front of it. Members of the government sit to the right of the speaker and members of the opposition to the left.

Current composition

Due to the long reign of Liberal Prime Ministers, the Liberal Party makes up more than half of the senators. Since the current Conservative government appoints most of the officials and controls the agenda, the Senate leadership is in the hands of the Conservatives. The other major opposition parties in the House of Commons, Bloc Québécois and New Democratic Party , are not represented in the Senate at all. Senator Lillian Dyck called herself a New Democrat, but since the party rejects the Senate as a whole, she also refused to recognize Dyck as a representative; Dyck joined the Liberal Group in 2009. The Liberal Party has also expelled Senator Raymond Lavigne (but he still sees himself as a party member). Although the progressive conservatives united at the federal level with the Canadian Alliance to form the Conservative Party in 2003 , three senators refused to take the step. Prime Minister Paul Martin then appointed two more senators who traded as progressive conservatives. Of the original five senators, one died, one joined the united Conservative Party and a third reached the age limit in 2009, so that the party, which actually no longer exists at the federal level, still has two senators.

| Political party |

Senators |

|

| Conservative Party | 40 | |

| Independent | 38 | |

| Liberal Party | 21st | |

| Vacant | 6th | |

| total |

105 | |

literature

- Canada. Senate Committes Directorate: A Legislative and Historical Overview of the Senate of Canada 2001 html version, accessed March 5, 2007

- R. MacGregor Dawson: The Government of Canada Toronto 5th ed. 1970, University of Toronto Press

- CES Franks: Not Dead Yet, But Should It Be Resurrected. The Canadian Senate. in: Samuel C. Patterson and Anthony Mughan (Eds.): Senates. Bicameralism in the Contemporary World. Columbus, Ohio 1999. Ohio State University Press ISBN 0-8142-0810-X pp. 120-161

- FA Kunz: The Modern Senate of Canada. A Re-Apraisal, 1925-1963 Toronto 1965, University of Toronto Press ISBN 0802051561

- Robert A. MacKay: The Unreformed Senate of Canada , Toronto 1963 McClelland and Stewart

- Tanja Zinterer: The Canadian Senate: unloved, undemocratic, unreformable? in: Gisela Riescher, Sabine Ruß, Christoph M. Haas (eds.): Second chambers. Munich, Vienna 2000. R.Oldenbourg Verlag ISBN 3-486-25089-2

Web links

- Department of Justice. (2004). Constitution Acts, 1867 to 1982.

- Forsey, Eugene. (2003). "How Canadians Govern Themselves."

- The Parliament of Canada. Official website.

- A Legislative and Historical Overview of the Canadian Senate

Remarks

Parts of the article are based on parts of the Senate of Canada article on Wikipedia in the version dated February 22, 2007.

- ↑ "Although we are not elected, we can block any and all legislation passed by the duly elected House of Commons. Not that we would ever use our powerful veto, given our unelected status. If we did, it would immediately be taken away from us; and so it should be. " quoted n. Franks p. 123

- ↑ a b Canada 2001

- ^ Fortier resigns from Senate to run for Tories , CBC News, September 15, 2008, accessed June 27, 2009

- ↑ “The Governor General shall… summon qualified Persons to the Senate; and ... every person so summoned shall become and be a Member of the Senate and a Senator "

- ↑ "sober second thought" quoted. n. Canada 2001

- ↑ "legislative terrorism" quoted. n. Franks p. 135

- ↑ "so sluggish and inert that it seemed capable of performing only the most nominal functions" Dawson p. 282 quoted. n. Franks p. 123

- ↑ "[The Senate] has not fulfilled the hopes of its founders; and it is well to remember that the hopes of its founders were not exceedingly high. "Dawson p. 279 quoted. n. Franks p. 123

- ↑ CBC: "Ontario premier ponders getting rid of the Senate"; Accessed March 5, 2007

- ↑ "The consultation of the electors ... in relation to the appointment of senators" CBC News: Canadians will choose senators under new bill ; Accessed March 5, 2007

- ^ Bill C-43: An Act to provide for consultations with electors on their preferences for appointments to the Senate , accessed March 5, 2007

- ^ Text of the proposal on the parliament server, accessed March 5, 2007