winter

The winter (from Old High German wintar , recyclable as gothic wintrus a Germanic root; .. Etymologically unclear (s u) , including an origin were suspected earlier of Indo UI "shine" ṷed- "moisten flow" and kinship with "water" as “the flowing” as well as a connection with a root with the meaning “white”) is the coldest of the four seasons in the subtropical , temperate , subpolar and arctic climatic zones of the earth. Depending on whether it is in the northern or southern hemisphere , one speaks of northern winter or southern winter . The northern winter takes place simultaneously with the southern summer.

Emergence

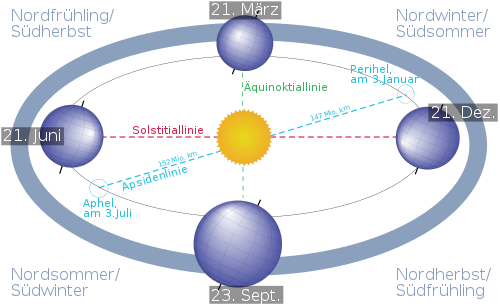

The seasons arise because the earth's rotation does not take place in the plane of the orbit around the sun, but inclined by 23.4 ° (see ecliptic inclination ). As a result, the south and north poles lie alternately in the grazing sunlight for half a year, and the zenith of the sun changes in the annual cycle between the southern and northern tropic .

Beginning of winter and duration

astronomy

Astronomically or in terms of calendar, winter begins with the winter solstice - the point in time when the sun is vertically above the tropic of the other half of the earth and the days are the shortest:

Then the days get longer again and the nights get shorter. Winter ends with the equinox of spring on

- March 20 or on the night of March 21 in the northern hemisphere and

- September 22 or 23 for the southern hemisphere .

The winter therefore lasts 89 days in the northern hemisphere and 93 days in the southern hemisphere.

In the East Asian cultural area, which is characterized by the Chinese calendar , winter begins when the sun is 45 ° before the solstice (November 7 or 8) and ends when the sun is 45 ° behind it (3rd, 4th November). or February 5th). The solstice is in the middle of winter.

Since the earth's orbit around the sun is slightly elliptical, i. H. deviates from an exact circular path by 1.7%, the four seasons are not exactly the same length. The northern winters are slightly shorter and milder than the southern winters because of the closeness to the sun ( perihelion on January 3rd).

meteorology

In meteorology , the beginning of (northern) winter is set on December 1st . It therefore includes the months of December, January and February.

Phenologically , the beginning of winter can differ considerably from the astronomical one and, in addition to the land-sea distribution ( maritime vs. continental climate ), is often marked by the beginning of a permanent snow cover . The increase or decrease of glaciers depends less on the winter snow conditions than on the first fresh snow in autumn , which inhibits ablation .

In the Alps , the festival “ Presentation of the Lord ” (popularly “Mariä Lichtmess”) on February 2nd is a statistical “ Lost Day ” for the weather in late winter. The saying “When it storms and snows at Candlemas, spring is never far” is well known. With the same meaning, but formulated the other way around , there is also the farmer's rule : "If the badger sundays himself during the week of light measurement, he stays in his hole for another 4 weeks!"

Approached dividing the winter in the northern hemisphere the months December , January and February to and in the southern hemisphere the June , July and August . The “ polar night ” prevails in the geographic poles for six months ; near the polar circles it lasts from a few days to weeks.

Energy industry

In the energy industry, the winter is defined as the winter half-year from October 1st to March 31st, because of the higher energy demand then, in deviation from the seasonal definitions.

Weather patterns and their influence on winter weather

The winter weather in Central Europe is determined by different weather conditions that result from the interaction of high and low pressure areas . The weather can last from a day to several weeks. Their continued existence or change can only be determined a few days in advance. A westerly weather situation with low pressure over Northern Europe and high pressure over Southern Europe brings humid and rather mild air from the Atlantic to Central Europe. Depending on the altitude, it can snow or rain. Storms coming from the west are possible. In the south-westerly weather conditions with high pressure over south-east Europe and low pressure near the British Isles, mild air flows in. Possible precipitation also falls in the high altitudes as rain. This weather situation is partly responsible for the Christmas thaw . In the area of action of a north weather situation with high pressure over west and low pressure over Eastern Europe, north-westerly winds bring damp and mild and north-east winds drier and colder air. The east or north-east weather situation with high pressure over north and low pressure over southern Europe causes the influx of dry, cold continental air.

Winter in climate change

In Germany in particular, winters have been wetter and milder for over two decades. According to earlier climate forecasts, this trend will continue. According to more recent studies, however, paradoxically, the ice melt at the North Pole due to global warming favors the formation of high pressure areas over Eurasia , so that more severe winters are expected here in the future, such as the snowfall in Central Europe in January 2019 . In the winter of 2019/20 no ice wine could be produced in Germany for the first time .

Records

Worldwide

The world's lowest temperature was -89.2 ° C in July 1983 in Vostok (Antarctica) measured.

Europe

In Europe there was the warmest winter 2019/20 with 3.4 ° C above the average measured temperature from 1981 to 2010.

Germany

In Germany there was the coldest winter 1962/1963 with an average temperature of −5.5 ° C and the warmest winter 2006/07 with a temperature of 4.4 ° C. The lowest temperature was -37.8 ° C on February 12, 1929 in Hüll (Upper Bavaria). The highest amount of snow on April 2, 1944 on the Zugspitzplatt was 8.30 meters. Here, on March 24, 2004, the heaviest snowfall occurred within 24 hours, bringing fresh snow 1.50 meters high.

Switzerland

2019/20 there were in Switzerland, with a mean of 0.7 ° C, the warmest winter since records beginning in 1864. The coldest place in terms of the mean annual temperature from 1981 to 2010, with -7.2 ° C, the Jungfraujoch . The cold pole is located in La Brévine , where on January 12, 1987, −41.8 ° C was measured, which corresponds to −42.5 ° C under today's measurement conditions. The highest snow depth was measured in April 1999 at 816 cm on the Säntis . Most of the snowfall within one day was 130 cm on April 15, 1999 on the Bernina Pass and on March 30, 2018 on the Grimsel Pass .

Culture

As in summer, there are also old customs in winter, some of which have survived or have been revived: for example, the solstice as Christmas , Alban Arthuan (Celtic), Yule Festival (Nordic / Germanic), Yalda night (Iranian), Carnival / Shrovetide / Carnival , masked ball , winter burning and Perchten run . Numerous writers and poets addressed the peculiarities of winter and the feelings and sensations it triggered.

gallery

The Ammersee in winter

The frozen Lübbesee near Templin , Brandenburg

Winter blossom - witch hazel in Vogelsberg

Fresh snow on the Swabian Alb

Hunds-Rose in winter

etymology

Germanic languages

The word winter is a Germanic "special word": it is found similarly in all Germanic languages, but nowhere else:

-

West Germanic :

- Old High German wintar > Middle High German winter , occasionally winder > New High German winter , Yiddish ווינטער 'vinter', Luxembourgish Wanter

- Old Saxon wintar > Central and neuniederdeutsch winter

- old english uinter , winter , wintær > middle english winter , next to it winnterr , wyntra , vinter , vyntyr , wenter , wintir , wintur , wyntre , wintre , wunter > new english winter

- old, middle and new friesian winter

- Old Dutch wintar > Modern Dutch and Afrikaans winter

- North Germanic: on the rune stone from Rök (around 800) uintur or uintura ( acc.pl. )

- Old-Norse vintr > Danish, Norwegian and Swedish vinter

- Old-West Norse vintr , next to vetr , older also vettr (with regular assimilation from -nt- to -tt- ), later vetur (with

- gothic wintrus

Further chose LL Zamenhof for Esperanto Vintró as a designation for the winter from; In addition to somero , this is one of two names of the seasons in this planned language , which is not of Romance, but of Germanic origin.

The original meaning of the word, for which the ancient Germanic form * wintru can be reconstructed, is unclear; Although there is no lack of suggestions as to how it can be derived etymologically , these are mostly assessed as unconvincing in the relevant overview works. The assumption already made by Adelung (1786) that winter is derived from the wind - or from germ. * Windaz <idg. * U̯ē-nto-s ; see. lat. ventus - hardly finds advocates since Friedrich Kluge (1882) decided that germ. * wintru- and * windo do not go along with each other. The German dictionary (Volume XIV, II, 1960) and the Indo-Germanic etymological dictionary by Julius Pokorny (1959) favor the view already advocated by August Fick (1870) that winter ultimately flows onto the root * u̯ed- “ springs ; wetting, moistening ”, more precisely to a root expansion with Nasalinfix , as it is also present in Lithuanian vanduõ “ water ”and Latin unda “ wave, wave ”, as Evald Lidén (1889) and Herbert Petersson (1912) worked out. Against this reconstruction, which is also morphologically not unproblematic, it has often been objected that "the wet time" or " rainy season " does not seem particularly plausible as a naming motif, since rain and moisture can hardly be considered the most prominent characteristics of winter, also and especially not in the original home of the Teutons. Christianus Cornelis Uhlenbeck (1905), like Kluge before, did not want to completely rule out the older assumption that the Germanic * wintru is more related to Celtic * windo "white", which resulted in Welsh gwynn and Irish finn and in Central Europe in Celtic place names such as Vindobona ( Vienna ) encountered; however, an equivalent to this Celtic etymon has not yet been found in any Germanic language . Anatoly Liberman (2012) therefore considers this hypothesis to be as far-fetched as the efforts of Terje Mathiassen (1968) to link Germ. * Wintru with Slavic * wed- "wither, pass away". In contrast, Fritz Mezger's attempt (1960) to etymologically reconcile Gothic wintrus with Old Norse vinstri "links" (cf. ahd. Winistar , aengl . Winstre , etc. <Germanic * wenistraz "links") seems promising to him. Like the Celt, the Teutons also orientated themselves in the cosmos with a line of sight to the rising sun, and on the left is the north , the home of winter (cf. Old Irish túath , which means both “left” and “north”; German is north in turn probably originally related to Umbrian nertru "left").

Other Indo-European languages

In all other branches of the Indo-European language family, however, the name of the cold season is derived from a typical root word * ǵʰey- ; so this applies to:

- Albanian

- Tuscan dimër , ghegisch dimën

- Armenian:

- Old Armenian ձմեռն 'jmeṙn'> new Armenian ձմեռ 'dsmer'

- Baltic:

- Latvian ziema , Lithuanian žiemà

- Greek:

- ancient Greek χειμών ‚cheimōn '> modern Greek χειμώνας‚ cheimónas'

- Indo-Iranian:

- Celtic:

- Old Irish gaim , gam , gem , also gaimred , gemred (compound with ráithe , "quarter year, season")> New Irish geimhreadh ; Old Welsh gaem , mittelwalisisch gayaf , neuwalisisch GEAF ; manx geurey ; Breton goañv

- Slavic:

- here in all individual languages quite uniform zima or зима, whereby the word accent falls on the second syllable in the East Slavic languages and on the first syllable in the West and South Slavic languages

as well as for the extinct Tocharian, Anatolian (Hittite gi-ma-an ) and Italian (Latin hiems ) languages. In the Romance languages that emerged from Latin , the word for "winter" is not derived directly from Latin hiems , but from the associated adjective hībernus "winterly": Italian and Portuguese inverno , Spanish invierno , Catalan invern , French hiver , Romanian iarnă . For idg. * Ǵʰey- an independent meaning "winter" is assumed; Pokorny also names the meaning “snow”, since the Greek χιών 'khiṓn' and Armenian ձիւն 'dzjun' 'snow' are derived from this root and Sanskrit 'himá' was also used in this sense (cf. Himalaya , actually the “ Heimstatt des Schnees ”), but this is likely to represent a secondary, i.e. derived, meaning, especially since * sneygʷʰ is a generally accepted root word for“ snow ”.

The Indo-European year

It should be noted that the Indo-Europeans only differentiated between two seasons. This should also still apply to the Teutons of antiquity, even if Tacitus reports in Germania around the year 100 that they knew not two but three seasons, namely winter, spring and summer, but had no term for autumn: 'unde annum quoque ipsum non in totidem digerunt species: hiems et ver et aestas intellectum ac vocabula habent, autumni perinde nomen ac bona ignorantur ' . The quarter division of the year, which is familiar to Tacitus and is still common today, can only be read in the Hippocratic script De diaeta and remained limited to the Greco-Roman culture for centuries. The fact that autumn and probably also spring were later innovations in the Germanic annual cycle brought about by Roman influence is confirmed by Beda , who explains in De temporum ratione (around 725) that, like the elements and temperaments , there are also four seasons, but also writes that the Anglo-Saxons have always distinguished between summer and winter: 'Antiqui autem Anglorum populi […] principaliter annum totum in duo tempora, hyemis, videlicet, et aestatis dispartiebant, sex illos menses quibus longiores noctibus dies sunt aestati tribuendo, sex reliquos hyemi ' . Beda also writes that October is called Wintirfylleth for them , since winter begins with the first full moon of this month - a possible parallel to this can be found in the Celtic, more precisely Gallic, calendar of Coligny , dated to the late 2nd century , in which six each of the twelve months are bundled into two half-years, with the Samon [* ios] (in Irish sam "summer" and samhain ?) the beginning - or the middle - of the one, the Giamon [* ios] (in Irish gam <idg . * ǵʰey- "Winter"?) marks that of the other half of the year. The old Icelandic calendar , the Misseristal , only differentiates between two seasons or half years ( misseri ). In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle , "autumn" is only mentioned in the entry for the year 1051, and not once about spring. The fact that winter and summer must be regarded as hyperonyms is also shown by the fact that the names of spring and autumn, in contrast to those of the two “main seasons”, are not represented uniformly in the Germanic languages (cf. German spring versus English spring and Swedish . vår ), sometimes even several terms compete in one language (German spring , spring and spring ; English autumn and fall ); for the Gothic there are no terms for the “secondary seasons” at all. The fact that summer and winter are a complementary pair of terms is shown not least by their word form: they are not only spoken of as homoioteleutons in German (cf. Irish sam and gam or also Welsh haf and geaf ) and appear as such in some old Germanic poems , so in Heliand ( 'he habda at them wîha sô filu wintrô endi sumarô' ) and in the Hildebrandslied ( 'in wallota sumaro enti wintro sehstic ur lante' ).

literature

- Joachim Herrmann : dtv-Taschenbuch Astronomie , pp. 41–44 (seasons), 15th edition, Munich 2005

- Julius Bartels : Fischer-Lexikon Geophysics (Seasons, Weather), Frankfurt 1960.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Alois Walde : Latin etymological dictionary. 3rd edition, obtained from Johann Baptist Hofmann , 3 volumes. Heidelberg 1938-1965, Volume 2, p. 806 (sv vitrum ) and 817 (sv unda ).

- ^ Friedrich Kluge , Alfred Götze : Etymological dictionary of the German language . 20th edition. Edited by Walther Mitzka . De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1967; Reprint (“21st unchanged edition”) ibid 1975, ISBN 3-11-005709-3 , p. 862.

- ↑ Energy Industry Act (EnWG) Section 3 No. 40

- ↑ Weather conditions in winter and why nobody can predict it. In: wetterkanal.kachelmannwetter.com , accessed on December 28, 2015

- ↑ bildungsserver.hamburg.de. Retrieved December 28, 2015

- ↑ Heavy rain in summer, wet and mild in winter. In: focus.de , accessed on December 28, 2015

- ↑ The paradox of global warming: Germans have to constantly adapt to extreme winters. In: focus.de , accessed on December 28, 2015

- ↑ Global warming could make winter colder. In: pik-potsdam.de , accessed on December 28, 2015

- ↑ Benita Wintermantel: Consequences of climate change: For the first time no ice wine in Germany. In: oekotest.de . March 3, 2020, accessed March 4, 2020 .

- ↑ The boreal winter season 19/20 was by far the warmest winter season ever recorded in Europe. In: climate.copernicus.eu . March 4, 2020, accessed on March 14, 2020 .

- ↑ Data for Europe: warmest winter since records began. In: tagesschau.de . March 4, 2020, accessed March 14, 2020 .

- ↑ 3.4 degrees warmer than average - warmest winter in Europe since measurements began. In: srf.ch . March 5, 2020, accessed March 14, 2020 .

- ↑ dwd.de. Retrieved December 28, 2015

- ↑ Weather records in Germany and worldwide. In: wetterprognose-wetter forecast.de , accessed on December 28, 2015

- ↑ Federal Office for Meteorology and Climatology : Climate Bulletin Winter 2019/2020. (PDF; 961 KB) Retrieved August 25, 2020 .

- ↑ Federal Office for Meteorology and Climatology: Records and Extreme. Retrieved January 12, 2019 .

- ↑ Winter poems / selected by Evelyne Polt-Heinzl and Christine Schmidjell, eds. Evelyne Polt-Heinzl, Christine Schmidjell, Reclam Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-15-018938-2

- ↑ Anne Marie Fröhlich (ed.): Winter - Texts from world literature , Manesse Verlag, Zurich 1989, ISBN 3-7175-1780-5

- ↑ For the oldest Germanic evidence see Maria Tallen: Word geography of the names of the seasons in the Germanic languages. Schmitz, Gießen 1963, p. 169 f.

- ↑ At least that is the consensus of the current edition of the Kluge - Etymological Dictionary of the German Language , 25th, revised and expanded edition, edited by Elmar Seebold. De Gruyter, Berlin [ua] 2011, p. 990, sv Winter (“Neither morphologically nor semantically supported”), the Oxford English Dictionary . 2nd edition, 1989. sv winter, n. 1 ( "although semantically plausible, neither of these explanations can be accepted with confidence" ) and the Etymological Woordenboek van het Nederlands , ed. by Marlies Philippa et al., Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2003–2009, sv winter ( “Geen ervan is morfologische en semantisch overtuigend” ).

- ↑ Johann Christoph Adelung: Attempt of a complete grammatical-critical dictionary of the High German dialect, with constant comparison of the other dialects, but especially the Upper German , Volume 5 ( WZ ), published by Johann Gottlob Immanuel Breitkopf, Leipzig 1786, Sp. 244-245 , sv winter .

- ^ Friedrich Kluge: Etymological dictionary of the German language . 1st edition. Trübner, Strasbourg 1882, p. 375, sv Winter

- ^ German dictionary by Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm. 16 vols. [In 32 partial volumes]. S. Hirzel, Leipzig 1854-1960, Volume 30, Col. 418, sv winter, m.

- ↑ Julius Pokorny: Indo-European etymological dictionary. Francke, Munich 1959, entry on root 136. au̯ (e) -9, au̯ed-, au̯er- on pp. 78-81.

- ↑ August Fick: Comparative Dictionary of Indo-European Languages: An Attempt in Linguistic History. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1870, p. 875., sv vintru .

- ^ Evald Lidén: Etymologies. In: Contributions to the history of the German language and literature. Volume 15, 1889, p. 522.

- ↑ Guus Kronen (Ed.): Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic. Brill, Leiden / Boston 2013, sv "Wintru-" ( "unconvincing: it is based on the wrong analysis of Lat. Unda [...]"

- ^ CC Uhlenbeck: Comments on the Gothic vocabulary . In: Contributions to the history of the German language and literature , Volume 30, p. 326.

- ^ Anatoly Liberman: The Seasons, Part 3: Rainy Winter? Posted on his blog, The Oxford Etymologist, April 4, 2012.

- ↑ Terje Mathiassen: Could be slav. * wed- "wither" and germ. * wint- in "winter" belong together etymologically? In: Norsk tidsskrift for sprogvidenskap. Volume 22, 1968, pp. 91-98.

- ^ Fritz Mezger: Got. wintrus "Winter, Jahr" and aisl. vinstri "left". In: Journal for comparative linguistic research in the field of Indo-European languages. Volume 76, No. 3/4, 1960, pp. 306-307.

- ^ Frank Heidermanns: Left and Right . Article in the real dictionary of Germanic antiquity. Volume 18. De Gruyter, Berlin [et al.], 2001, pp. 480-483.

- ↑ Willy Sanders: To ahd. Lenka "Die Linke" in Abrogans . In: Eva Schmitsdorf et al. (Ed.): Lingua Germanica: Studies on German Philology. Jochen Splett on his 60th birthday. Waxmann, Münster 1998, p. 245.

- ↑ Lenka Doçkalová and Václav Blazek: The Indo-European Year . In: Journal of Indo-European Studies 39: 3-4, 2011, pp. 414–495.

- ↑ On the etymology of hibernus s. Oswald Szemerényi: Latin hībernus and Greek χειμερινός , in: Glotta 38: 1/2, pp. 107–125.

- ↑ On the reflexes of hībernus in the Romance languages s. Walther von Wartburg: French Etymological Dictionary , Volume 4 ( G, H, I ), Helbing and Lichtenhahn, Basel 1952, pp. 418–422, sv hībĕrnus .

- ↑ Julius Pokorny: Indo-European etymological dictionary . Francke, Munich 1959, entry on root 632. ĝhei-2: ĝhi- on pp. 425-426.

- ^ Thomas V. Gamkrelidze and Vjačeslav V. Ivanov: Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: A Reconstruction and Historical Analysis of a Proto-Language and Proto-Culture. Part I: The Text. De Gruyter, Berlin [et al.] 1995, pp. 587-588.

- ↑ Robert Nedoma: Article Seasons in the Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde , Volume 16. De Gruyter, Berlin [among others] 2001, pp. 17-21.

- ↑ Bearnard Ó Muireagáin: The Semantic Shift of "Samain" from Summer to Winter .

- ^ Xavier Delamarre: Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental . Errance, Paris, 2003, p. 178.

- ^ Jean-Paul Savignac: Dictionnaire français-gaulois . La Différence, Paris, p. 82.

- ^ Richard Jones: The Medieval Natural World. Routledge, London / New York 2013, p. 47.

- ↑ PS Langeslag: Seasons in the Literatures of the Medieval North . DS Brewer, Cambridge 2015, p. 9.

- ^ Earl R. Anderson: The Seasons of the Year in Old English. In: Anglo-Saxon England. Volume 26, 1997, pp. 231-263, here pp. 234 f.

- ^ German dictionary by Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm. 16 vols. [In 32 partial volumes]. S. Hirzel, Leipzig 1854-1960, Volume 30, Col. 418, sv winter, m.