Jewish community of Oberwesel

The Jewish community of Oberwesel , the former imperial city of Wesel (1237 to 1309), was first mentioned in the imperial tax register of 1241 . As in most regions of the empire, in the centuries that followed, the Oberwesel Jews experienced a constant sequence of toleration and expulsion. The latter usually went hand in hand with the loss of their belongings, often even with the loss of their lives. Even a period of peaceful coexistence that began in the 19th century ended soon after the First World War , because the anti-Semitism that was still latent in Oberwesel regained the upper hand and culminated in the complete annihilation of Jewish life in the city during the Nazi era .

history

Jews on the Rhine

Relevant research assumes that Ashkenazi Jews were already trading along the Rhine in the wake of the Roman conquest of Lower Germania and settling on this waterway lined with military roads . However, it was only from the time of the Salians up to the first crusades that there was evidence of permanent Jewish residency in the larger cities on the Rhine. The economic and social situation in which this population group lived at that time is illustrated by a text in Herimanus quodam Judaeus written around the middle of the 12th century . The descriptions in this document show that at that time the Jews were not yet subject to any arbitrary legislation, as it was then enacted and also practiced in various Jewish ordinances in the centuries to come . For the time being, they had free space for their business activities and were able to acquire real estate inside and outside the cities, which they were even allowed to have Christian day laborers cultivate.

Free imperial city and the protection of the rulers

In a decree from Emperor Heinrich in 1090, it was said : Nobody should levy customs duties or a public or private tax from them (the Jews) , but the Jews experienced that reality soon looked different. An imperial privilege given to protect the Jews was supposed to place the Jews under the special care of the ruler and regulate their rights in dealing with Christians. But even with the pogroms that broke out against the Jews of Mainz , protection was missing and with Heinrich's death in 1106 the living conditions of the Jews on the Rhine became almost incessantly worse.

At the beginning of the Second Crusade (1147/49), a fanatical monk called Radulf (also Rudolf, Roudolphe) used the Cistercians (the order later also had a branch in Oberwesel) by calling on the crusaders who also passed through the Oberwesel region to to slay the unbelievers (a popular metaphor for those of different faiths). As recently as 1236, in the last year of his reign, Emperor Friedrich II had issued a so-called Judenregal by decree - a tax known as protection money - but the Jews received no protection in an emergency that soon occurred. This was the case with the pogroms in the second quarter of the 13th century, when brutal attacks against the Jewish population emerged again. As the supreme patron, Friedrich defends the Jews against so-called blood lies, but they were only words of criticism and no action was taken. On a court day, too, he turned against further charges of this kind against the Jews and forbade them. Threatened sanctions in the event of violations were not reported at the Hoftag in the Palatinate in Hagenau .

Regalia - taxes

With the new status of the city, the elevation to a free imperial city , (Upper) Wesel was only subordinate to the successor of Frederick King Konrad IV as the highest authority . Otherwise the city was self-sufficient in almost all areas. For example, the Jewish tax was initially reserved for the Reich. In this it was for the authorities soon to rule them from Jews to be paid poll tax in individual cases, but as a package from the head (the mostly congregational rabbi of each) Jewish community to make collect. The certificate of a tax list received contains the recorded data of the region. According to this, the tax rates of the Jewish communities created within a Christian commune were staggered. For example, during the reign of Emperor Frederick II , the tax authorities levied an annual fee of 20 silver marks for the Jewish community in Oberwesel in 1241 . A comparative study of the tax amounts set by different Jewish communities in the Reich showed, on the one hand, that the majority of these communities lay on the Middle Rhine , and on the other hand, the data on the tax assessment amount showed the size of the communities that were created. According to Schilling's research , the Worms Jews had to pay 130 marks , those in Speyer 80 marks, the Oppenheim Jews 15 and those from Sinzig and Boppard each had to pay 25 marks.

Pogrom of 1287

In 1287/88 the events of a ritual murder allegedly committed in Oberwesel developed into a two-year national wave of violence against Jews.

This escalating violence is said to have been triggered by members of the Franciscan Order , who had already founded a branch in Oberwesel (Wesel) in 1242. The Franciscans preached until their own monastery church on the northwestern Martinsberg was completed, in the two parish churches of Liebfrauen and St. Martin in the village. The sermons in these churches, which were given in the simplest of terms, were very popular and found increasing popularity. However, since the contents of these sermons were directed very aggressively against the Jews, they fueled the Jewish hatred of the faithful and encouraged violence.

The unexplained death of the 16-year-old day laborer Werner von Oberwesel from Womrath , who was employed by a Jewish family in Oberwesel, led to a prolonged wave of pogroms.

According to a report from the Latin translation of the Colmar manuscript , the Jews had turned to the ruler for help. After that, in 1288 Rudolf von Habsburg felt compelled to react and fined the citizens of the imperial cities of Boppard and Oberwesel. He also returned their property to the expelled Jews.

Under the Jewish ordinances in the times of the prince-bishop

When the election of a new king came up in 1308, Baldwin , elector and archbishop of Trier , is said to have successfully helped his brother Heinrich to power by all means (diplomatic and financial). For the enormous funds required for the coronation and later anointing in Rome, Henry VII now had to owe his brother 394 marks ( Cologne ) to whom he assigned the Jewish tax for the cities of Boppard and Oberwesel as security. In addition, Heinrich gave his brother Balduin in the contract of September 1309 the rights of a governor (Vogt) over both cities. Since the pledge was never released (Heinrich died on the way back from Rome), the two cities lost their imperial immediacy . After this loss of status, the protective system of chamber protection ceased to apply to Oberwesel's Jews as well. The amendment and usufruct of the Judenregal was subsequently firmly in the hands of the Trier sovereign and remained a valued source of income for the ruling authorities.

During the time of the marauding Armleder pogroms in 1336/37, there were new riots and looting against Jews from Oberwesel, whereupon Archbishop Balduin forced the city in 1338 to redeem the property stolen from the Jews in return for high compensation and stipulated conditions for how Jews would live in Oberwesel in the future should. During the years of the plague spreading from Genoa and rampant across Europe (1347 to 1351), the Oberwesel Jews were also accused of the epidemic and the like. a. to have triggered by well poisoning . The real reasons for looting and murder, however, were a lack of religious tolerance and the Christian population's frequent indebtedness with their Jewish believers. At this time, 217 Oberwesel citizens of Christian faith are said to have been indebted to 29 Jews in their city. Around a third of these creditors are said to have been women who acted as moneylenders. In almost all regions of the empire, the Jews were plagued by outbreak of pogroms. On the Middle Rhine, the communities in Andernach , Bacharach , Boppard, Braubach , Kaub , Koblenz , Lahnstein , Mayen , Oberwesel, Remagen and Sinzig were particularly hard hit . Despite all these bad times, displaced or surviving Jews viewed their respective city on the Rhine as their home, which they usually did not give up, even if some had the courage to return after years.

If you add up some data and facts, for example the tax list from 1241 with the first mention of the Oberwesel Jewish community, the reimbursement of costs to Archbishop Balduin through the pledging of the annual tax in 1309, the 49 Jewish families in the town documented for 1338 and those in a parchment deed of the Entry cited in the year 1379: "Joseph, son of Jakob von Montabaur (" Montabur "), Jew from Oberwesel (" Wesel "), issues a lapel to Junker Eberhard von Isenburg about an agreement that will deliver the 400 gold guilders still owed from customs Kaub to get “, these facts document the existence of an established Jewish community of medium size in Oberwesel, as they were apparently typically to be found on the Middle Rhine.

Late Middle Ages and Modern Times

The resulting better economic conditions in the empire also increased the prosperity of Rhenish cities. Trade and industry flourished and filled civic and communal caskets as well as sovereign coffers, so that Jewish credits became more and more dispensable. So Jews were expelled from various cities in the Rhineland at the beginning of the 15th century , a procedure of the authorities, as also the Trier Archbishop Otto von Ziegenhain ordered in 1418/19 for all Jews of his archbishopric. This temporary dispensability of Jewish tax money had shown itself in a wave of expulsions of Jews by the sovereigns that had started for some time. They were expelled from the city of Strasbourg as early as 1387, while the Electoral Palatinate initially only ordered individual expulsions. In 1418 von Ziegenhain ordered the expulsion from the Archbishopric of Trier. Jews were expelled from the city of Cologne in 1426 until the French era and in 1435 in the diocese of Speyer, which Mainz also followed with expulsions in 1438. Occasionally, in smaller communities, Jewish families were still tolerated, as, for example, a Jewish school in Oberwesel is occupied for the year 1452 . At the beginning of the 16th century, following a decree by Archbishop Richard von Greiffenklau zu Vollrads of Trier, Jews were allowed to reside in the Archbishopric again. This happened first in Lützel and then in the old town of Koblenz . In 1547 the Elector Johann allowed 34 families to reside in Boppard and other places of the archbishopric and in 1555 the growing communities were even allowed to elect a rabbi . The devastating "accidental" fire of 1570 in Oberwesel, destroying many of the houses, was part of a chain of calamities that were usually blamed on the Jews. Only a little later, there was another U-turn in the Jewish policy of the Archbishopric by making the accumulation of restrictions in the Jewish regulations even more drastic. In 1579, under Archbishop Jakob , the expulsion of all Jews living in the archbishopric was again ordered. The new regional order of the Rheingau said:

"That in addition no Jew is allowed to live or live in our country, the Rheingau."

The former imperial Judenregal was almost completely in sovereign hands at the beginning of the 17th century . With regard to a temporary settlement or the escort for one or more Jews, the respective sovereigns had issued their own Jewish regulations in the territories of the Reich. These stricter regulations were in force in the diocese of Strasbourg in 1575, in Worms in 1584, in the Archdiocese of Cologne in 1599, in Frankfurt am Main in 1613 and were also found in the first Electoral Trier Jewish Regulations of 1618 for the Archdiocese of Trier. The regulations contained therein demanded, for example: the Jews should: not engage in usury; have no secret or public synagogues ; do not teach a Christian in their law; hold no office or craft; to make special signs unconcealed on their clothes.

The Jewish order, which was also relevant for Oberwesel, was confirmed again in 1624, and after the unrest that broke out in 1635, the already strict decrees were tightened by Archbishop Karl Kaspar .

Emigration of the Jews

As at the time of the Crusades, the rights of the Jews were steadily reduced and the atrocities of the war (from 1618 to 1648) did the rest, so that many Jews in the Rhenish cities resigned and left Germany. They mostly turned to eastern countries, preferring to start a new life in Poland . In German states, they moved to areas of the Rhineland in which isolated places or newly established cities were ready to accept some of the expelled.

The Jews who remained in the Archbishopric Trier for high escort payments were threatened with new restrictions after the war years. Because of persistent complaints from the estates , Archbishop Karl Kaspar von der Leyen tightened the Jewish laws in June 1654 by a. the interest rates to the detriment changed. The rate of interest granted to Jews for credit transactions was further reduced in 1681 by Archbishop Johann Hugo von Orsbeck and lowered by Elector Franz Ludwig to the 5% annual interest rate permitted in the imperial statutes. In 1722, as sovereign, he allowed 160 Jewish families to continue living in the archbishopric and issued a new escort license for a period of twelve years. The Jewish families living in camera locations were not included. Franz Ludwig's Jewish ordinance, issued in 1723 and valid for all capitals and sub-towns of the archbishopric, also contained something new. In paragraph 3 it was stated that the Jews should no longer live among Christians, rather each city should designate and fence in a "strange" street in which the Jews would then have to build a dwelling. This ghettoization in the form of a Judengasse can be found in Oberwesel's neighboring towns of Boppard and Bacharach, but the Jews in Oberwesel lived scattered among the Christian population. But the passage in paragraph 7 was also new , in which it said, for example: "... how the Jews can seek and receive justice". In connection with Paragraph 3, a document from the Koblenz State Main Archive can be seen. It comes from the year 1725 and is a fair copy of a protocol of the court chamber approved by Elector Franz Ludwig ( protocollum regiminis electoralis una cum apostillis eminentissimi ), which contains the assurance of the office of Boppard, according to which "no Christians are in office in wages and bread with Jews , only in Oberwesel Jews live permanently with the widow of Wilhelm Schütz ”. Another transcript from October 10, 1726 shows that times had changed even in the case of a legal dispute with a Jew. The opposing parties did not become violent, but instead brought the matter to the Oberwesel lay judge. Various subjects from Langscheid and Dellhofen (both today's suburbs of Oberwesel) brought a lawsuit against the Jew Meyer Moses zu Oberwesel before the Oberwesel lay judge and accused him of unjustified financial calculations. The change to the rule of King Friedrich replaced the electoral decrees, but for the time being there were few improvements for the Jews. The general privilege issued in 1750 and only slightly changed followed almost seamlessly from previously valid Jewish regulations.

Funeral services

As can be seen in numerous examples, the Jews were given mostly agriculturally unusable land for their burials. For the construction of the cemetery, they were given a plot of land located in Oberwesel's district Graue Lay, then unwooded on the southern slope of the Niederbach valley. According to the oldest legible gravestones, this happened in the first half of the 18th century at the latest. The facility was used by the Jewish population of Oberwesel and the Jews from Perscheid . This chronological classification is also confirmed by the oldest legible tombstone from 1718 or 1738. Altogether (up to the last burial of a parishioner in 1942) the tombs there with their inscriptions show that there were extensive family ties. The inscriptions list the professions of the deceased, such as teachers, doctors, rabbis and merchants, etc., from which their membership of an educated middle class can be seen. It is not known whether Jews in Oberwesel were able to bury their deceased relatives on site in the centuries before. Conceivable are burials at the end of the 17th century created (1681) Jewish cemetery Bornich in Bornicher Forst, who is also from the Jewish communities Sankt Goar and Werlau was used. Alternatively, an arduous and expensive burial could take place in Koblenz. There was a Jewish association cemetery there , to which temporarily deceased Jews from the surrounding area could also be brought. However, high fees had to be paid to bury corpses brought in from distant places by land or water, whereby a gold guilder was charged for adults and half the amount charged for the burial of a child's body. It was not until the 18th century that Jews dared to take action against the collection of this “corpse tax” by suing the court court , but only after nearly 40 years of litigation (1742–1784) were successful with the lawsuit.

French rule

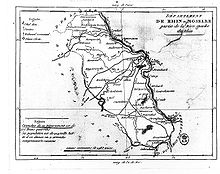

In 1794, with the occupation of the country by the French, feudal legislation also ended for the Jews of Oberwesel. The French revolutionaries conquered the area on the left bank of the Rhine , which was granted to them as their own national territory in the peace treaty of Campo Formio . Oberwesel's Jews, after a census of May 6, 1808 only 33 souls, had now, like their neighbors, become French citizens of the Arrondissement de Simmern in the Rhin-et-Moselle department and, like them, were subject to the same legislation. Now her situation was immediately improving in some matters. Although no ghetto with the gates of a Jewish alley had to be closed in Oberwesel, another city could now be visited without any formalities. The body duty could no longer be demanded from them either. According to the “Code Napoleon” decree, the Mairie Oberwesel belonging to the canton of Bacharach also recorded family data and prescribed the use of fixed hereditary names for the local Jews. They did not experience the hoped-for equality, for example a free choice of profession or place of residence, under French rule . For the time being, the contents of the revolutionary slogan Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité remained just a pipe dream for the Jews on the Rhine.

Smaller municipal administrations later outsourced their files. This was true for both the medieval and modern collections, with the French and Prussian administrative periods containing more extensive documents. They are now in the Koblenz State Main Archive and can be viewed there in detail. For example, under the heading “Jewish Cult”, the archive also offers some information on matters relating to the Jewish citizens in Oberwesel. There are some overviews of the personal and commercial circumstances of the Jews between 1808 and 1835.

Development of the Jewish community in the Prussian state

The Jews of the Rhine Province , in which Friedrich Wilhelm III. ruled in June 1822, comprised about 15,400 people on the left bank of the Rhine, of which about 6,600 lived in the Koblenz administrative district . Oberwesel's Jews now lived under a Prussian government, but initially neither they nor the Jews of the entire Rhineland were given the same rights and freedoms that the Prussian Jewish edict of 1812 had legally guaranteed in "old Prussia" by recognizing the Jews there as Prussian citizens . The circumstances of the Rhenish Jews changed due to the change in the line of succession of the House of Hohenzollern , but these changes were only of marginal importance. For example, under Friedrich Wilhelm IV., During the second year of his reign, they were allowed to use Christian first names. The joint application of numerous Rhenish cities during the 7th Provincial Parliament of the Rhine Province to transfer all civil rights to the Rhenish Jews was rejected, apart from a few local regulations.

Information in archival documents

In the Koblenz archives, in which the regional collections of the cities and municipalities are located today, one learns, for example, that between 1823 and 1853, school attendance by Jewish children was regulated.

The Oberwesel boys' school , built between 1834 and 1840 under the Koblenz architect Ferdinand Nebel , which greatly increased the capacity of the previous classroom , certainly contributed to this innovation . A file on the financial support of the synagogue community records data between 1824 and 1920. This probably confirms a synagogue that existed at that time , but not the time of its construction;

The formation of synagogue districts, elections of rulers, etc. are recorded in files from the years 1847–1927. Religious instruction was given to Jewish children around 1899–1900. In 1847 the organization of Jewish communities was regulated by law. In the St. Goar district , which was formed in 1815, the district town of the same name also remained the seat of the St. Goar synagogue community, which initially comprised three electoral districts. The first constituency consisted of the Jewish communities in Oberwesel, Niederburg , Damscheid , St. Goar, Werlau , Biebernheim , Urbar , Utzenhain and Badenhard .

Until the first known synagogue was built in 1853, the community had used a prayer room in one of the Jewish houses. Religious tasks in the community were taken care of by a teacher who was both prayer leader and shochet . In 1856 Oberwesel was awarded the Rhenish City Code, the statutes of which promised a little more liberality , but it was not until the German Empire was founded in 1871 that all Jews in the German provinces received full civil rights. In 1872 the corner house at Damscheider Strasse 1 (today Oberstrasse 1, corner of Chablisstrasse) was built on Schaarplatz, a two-storey brick building commissioned by the Jewish businessman Alexander Mayer from Oberwesel.

Jewish institutions

The first known Jewish institution in the village was a school (at that time also a prayer house), so a synagogue cannot be excluded. In the past, lessons and services were often held in these buildings or in smaller congregations in a prayer room . However, this location cannot be localized today, nor is a likely Jewish cemetery in the village at the time. There is evidence that a cemetery was built in the first half of the 18th century. It is the cemetery that still exists today, outside the city on the northern slope of the Niederbach valley leading to Damscheid , which the Jewish community used until its destruction. The following decades, up to the next century, seem to have passed peacefully between the Christians and Jews of Oberwesels. In 1824, the files mentioned financial support from the local synagogue community and in 1836 the community received timber from the city for the construction of a new synagogue, as the church that had been in use up to that point had burned down.

Ritual bath in Holzgasse

The ritually used Jewish facilities included the house of worship or prayer (school), as well as a house near a running water for washing the deceased (in Oberwesel der Niederbach) and also the availability of a mikveh , which was also used in a neighboring community if necessary. Such a ritual bath was very important for life in a Jewish community. The ritual ablutions carried out in it demanded “living water”, with the help of which the establishment of cultic purity could be brought about. There was no evidence of such an institution in Oberwesel in the files. This may be due to the modest size, which could not be compared with the sometimes magnificent grounds of the large and affluent communities in the cities of Worms, Speyer, Mainz, Frankfurt or Cologne. Chance brought to light that there was a former mikveh in the old Jewish community of Oberwesel.

Like the house wells or Pütze, which were used earlier, one of them on Holzgasse 4 (1576), a medieval mikveh was usually well below street level. Such a ritual bath was mostly located under the cellar of a residential building, from which another stairway was led down until the groundwater level was reached. An additional deepening was created there as a plunge pool, so that the community always had a sufficiently filled plunge pool available despite seasonal fluctuations in the water level.

The Oberwesel mikveh in Holzgasse - a street in the city already mentioned in 1253 - was discovered after the new owner bought an old half-timbered house when, on the occasion of extensive disposal work on the cellar vault, a corridor filled with soil appeared. The poorly excavated well system was identified as a ritual Jewish bath in 2003 after investigations by the State Office for Monument Protection. The description of the location (supplemented by a black and white photo) contains the following information:… “15 steps lead into another room, which is 5 - 6 m below street level. The room is filled with crystal clear water, even in the extremely dry summer of 2003. “A more detailed investigation, as well as the systematic search for such systems in places in the region, is still pending.

Association of the individual communities

From 1888 the rural communities of Perscheid , Hirzenach and Werlau belonged to the municipality of Oberwesel. Bacharach, Oberheimbach , Niederheimbach and St. Goar also joined in the 1930s . Although Oberwesel's Jewish community no longer reached its numerical peak of the Middle Ages in modern times, it became one of the large association communities on the Middle Rhine due to the space available for a new synagogue and the organizationally sensible alliances with neighboring communities.

Information on the last synagogues

The architectural forms that still prevailed well into the 19th century, which often preferred the Moorish style when building a new synagogue or renovating it, were now supplanted by romantic classicism or by the neo-Romanesque architectural style, in keeping with the taste of the time . The latter was significantly influenced in sacred building by Edwin Oppler from Hanover , who was considered the leading German architect of synagogue construction.

For the year 1853 reports mention a new and spacious synagogue, which is also said to have had a women's gallery . Its existence was probably only short-lived due to a fire, because an archive file from 1886 documents the construction of a new synagogue on Oberwesel Schaarplatz.

A surviving design drawing by master bricklayer J. Küpper shows the later church as a three-storey building, which was then built on the lower Schaarplatz as a corner building on Rheinstrasse. A two-sided staircase led to the arched entrance above the basement , which was flanked by half-height windows of the same style. The next upper floor received a women's gallery in its later version and, according to the drawing, received four high, harmoniously arranged arched windows, which helped both floors inside to a large amount of light. The end of the construction was formed by the top of a dwelling , flush with the house facade , the half-height winged arched window of which was bordered on both sides by a graceful arched frieze with corner waiting areas. The house facade with its features and the gewalmte roof with the by battlements decorated dormer , where a weather vane was set up, should the ornament of the square had been, and also met the traditional ideas of the Jewish community. The aim was to design such a building, which was not exposed by the elevated position of the property, in such a way that it stood out from its neighboring buildings at least at its location.

Oberwesel heroes of the First World War

After the First World War , in which men of the Jewish community took part as well as their Christian neighbors, a memorial plaque was installed in the synagogue for the fallen officers and men who had not returned home, on which the names of the dead were recorded. The stone tablet contains the carved names of the fallen between 1914 and 1918, the full inscription reads:

- Our hero

- Isidor Aschenbrann

- Berthold Gerson

- Alfred Geson

- Moritz Lichtenstein

- Jakob Frenkel

- The grateful church

Although the Jews of Oberwesels fought side by side with the Christians for the common fatherland in the war, a common memorial plaque for the fallen of both religions was apparently not made. The plaque of honor for Christians was placed at the Church of Our Lady and the memorial plaque for the Jewish dead was placed in the synagogue on Schaarplatz.

Weimar period

After their participation in the First World War, Jews were officially honored and decorated with the Iron Cross , but it was only after the end of the German Empire and the Weimar Republic that was proclaimed that Jewish citizens were given the desired equality. They could now even be elected to state, administrative and government offices.

The economic situation of the young republic experienced some “golden years” after the inflation , which soon gave way to nationwide mass unemployment. In many places in the Rhineland, the municipalities employed the unemployed as part of so-called “emergency work”. The Jewish cemetery was given a paved access road between 1928 and 1932. Incidentally, Jews were most severely affected by unemployment, despite mostly good professional qualifications.

Years until the Shoah

By the propaganda of the NSDAP Gau Koblenz-Trier competent Gau (seat Koblenz) under from Gemünden (Hunsrück) originating Josef Grohé initiated the phase of the boycott of Jewish businesses. From there, the district leader responsible for Oberwesel (in one of the 23 district leaderships as the middle NSDAP level) in neighboring St. Goar received lists of addresses of Jewish businesses to be checked in June 1933, according to which all party members were to report which citizens were among Jews Made purchases. This stirring up of the anti-Semitic mood was followed by the creeping Aryanization of Jewish businesses and businesses, as well as the open measures that culminated for the time being in the Nuremberg Laws of 1935. Years of psychological harassment escalated into physical violence with the November pogroms in 1938 .

After the Second World War

The old synagogue of the orphaned Jewish community on Schaarplatz was converted into residential and office purposes in the 1950s. Initially, the building's rooms were used by the gendarmerie and the Oberwesel water police , for whose purposes detention cells were also created in the building . Only a few members of the former Jewish community survived. One of them is Alfred Gottschalk , who was able to leave Germany in 1939. In 2006, a few years before Gottschalk's death, a memorial donated by the citizens of Oberwesel was erected in his presence in front of the former synagogue on Schaarplatz, on which the names of his relatives were also written. Some of the other names were identical to the names of those Jewish soldiers who had died for Germany in the war between 1914 and 1918. The memorial plaque made at the time was recovered from the synagogue, which was later devastated, and can now be found “An der Grau Lay”, where it was attached to a high grave border in the old cemetery of the Oberwesel Jews.

Commemoration

The area of the Jewish cemetery has been under monument protection since 1992 and is part of a monument zone with all of its facilities in the Oberwesel district.

In addition to the memorial and memorial with the names of the last Jewish community members on the upper Schaarplatz, information on the vitae of the converted building was attached to the former synagogue building. Students at the local Realschule plus have dedicated themselves to the memory of their former Jewish fellow citizens for years. So they were / are actively involved when it comes to the maintenance of the Jewish cemetery complex and researched in the run-up to the Stolpersteine project about the fate of the deported Jewish fellow citizens, to whom the stones by the artist Gunter Demnig are dedicated.

The stones laid in spring 2015 (21 in total) are located in front of the houses at Chablis Straße 12, Heumarkt 11, Kirchstraße 85, Liebfrauenstraße 50, Pliersgasse 5 and Schaarplatz 1. They not only remind of the victims of the Nazi era, they also show that the Jewish citizens were scattered across the city.

literature

- Eduard Sebald and co-authors: The art monuments of Rhineland-Palatinate, volume 9. The art monuments of the Rhein-Hunsrück district, part 2. Former district of St. Goar, here: City of Oberwesel in volumes I and II, State Office for Monument Preservation Rhineland-Palatinate (Ed.) Deutscher Kunstverlag 1977. ISBN 3-422-00576-5

- Anton Ph. Schwarz: A journey through time through Oberwesel , Bauverein Historische Stadt Oberwesel e. V. 2000 (Ed.), Printing: HVA Grafische Betriebe GmbH, Heidelberg

- Anton Ph. Schwarz and Winfried Monschauer: Citizens under the protection of their walls. 800 years of Oberwesel city fortifications . Edited by Bauverein Historische Stadt Oberwesel, 2012

- Konrad Schilling, Hermann Kellenbenz , in: Monumenta Judaica. 2000 years of history and culture of the Jews on the Rhine. Handbook for the exhibition in the Cologne City Museum Oct. 1963 - Febr. 1964 . On behalf of the city of Cologne. Edited by Konrad Schilling. [Vol. 1:] - Cologne 1963, Bachem publishing house

- Doris Spormann and Willi Wagner: The synagogue communities in St. Goar and Oberwesel in the 19th and 20th centuries. Traces of rural Jewish community life on the Middle Rhine. In: Sachor. For contributions to Jewish history in Rhineland-Palatinate see 1992 issue 3, pp. 22-30.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bredt, cemetery and tomb: "The Jewish cemeteries" in communications of the Rhenish Association for the Preservation of Monuments and Heritage Protection, year 10 (1916)

- Hermann Keussen : Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages , in 2 volumes. Cologne 1910. ISBN 978-3-7700-7560-7 and ISBN 978-3-7700-7561-4

- Adolf Kober , in: On the history and culture of the Jews in the Rhineland , Ed. Falk Wiesenmann. Pedagogical publishing house L. Schwann-Bagel GmbH Düsseldorf, reprint 1985. ISBN 3-590-32009-5

- Reinhold Bohlen, René Richtscheid, Emil Frank Institute , 2010. Richtscheid, Rene: Know who you are standing in front of : The Wittlich synagogue through the ages. Paulinus Verlag GmbH, ISBN 978-3-7902-1650-9

- Angelika Schleindel, Jewish life in Wittlich . Exhibition catalog Wittlich, Stadtverwaltung (Hg), 1993

- Winfried Monschauer, The Minorite Monastery in Oberwesel - History of an extraordinary monument. Editor Kulturstiftung Hütte Oberwesel, 2013. ISBN 978-3-00-043393-1

- Christof Pies (among others): Jewish life in the Rhein-Hunsrück district . Hunsrück History Association V. (Ed.) Volume 40, Argenthal 2004. ISBN 3-9807919-7-1

- Pia Heberer, The Wernerkapelle in Bacharach , in: Preservation of monuments in Rhineland-Palatinate, annual reports 1992–96, Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, Worms 1999, p. 37 ff ISSN 0341-9967

Individual evidence

- ^ Hermann Kellenbenz in: Monumenta Judaica. 2000 years of history and culture of the Jews on the Rhine , Konrad Schilling (Ed.), Here “Taxes” p. 209 ff

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Anton Schwarz, A journey through Oberwesel, in: Bauverein Historische Stadt Oberwesel, p. 96 ff

- ^ Hermann Kellenbenz in: Monumenta Judaica. 2000 years of history and culture of the Jews on the Rhine , here “The Jews in the economic history of the Rhenish region”, p. 207, note 40, reference to: J. Greven: The writing of Herimannus quondam Judaeus “De conversione sua opusculum” . In: Annals of the Historical Association for the Lower Rhine. Volume 115, 1929, pp. 111-135

- ↑ a b c d Hermann Kellenbenz in: Monumenta Judaica. 2000 years of history and culture of the Jews on the Rhine , here “The Jews in the Economic History of the Rhenish Region”, p. 199 ff

- ^ Online version of The Blood Lie , Schildberger, Berlin 1892

- ^ Hermann Kellenbenz in: Monumenta Judaica. 2000 years of history and culture of the Jews on the Rhine , here “Excesses of the 12th Century”, p. 68 ff

- ↑ Konrad Schilling In: Monumenta Judaica. 2000 years of history and culture of the Jews on the Rhine . Here "Taxes" p. 209 ff

- ↑ a b Anton Ph. Schwarz in: Citizens in the protection of their walls. 800 years of Oberwesel city fortifications

- ↑ a b Eduard Sebald and co-authors: Die Kunstdenkmäler von Rheinland-Pfalz, Volume 9. The art monuments of the Rhein-Hunsrück district, part 2. Former district of St. Goar, here: City of Oberwesel , inner city former synagogue, p. 706 ff

- ^ Konrad Schilling in: Monumenta Judaica. 2000 years of history and culture of the Jews on the Rhine . Here “State Archives Koblenz, I documents, inventory 1 A No. 4417 (Jan. 24, 1309)” note 67, p. 237

- ^ Hermann Kellenbenz in: Monumenta Judaica. 2000 years of history and culture of the Jews on the Rhine . Here "Money transactions", p. 214 ff

- ↑ Adolf Kober, in: On the history and culture of the Jews in the Rhineland , p. 23, note 3.)

- ↑ State Main Archive Koblenz. Inventory 35, Reichsgrafschaft Wied-Runkel (Wied-Isenburg), certificate 153

- ↑ Winfried Monschauer, Das Minoritenkloster in Oberwesel , note 18 p. 22, l LHA Koblenz, inventory 1 C No. 37 p. 573 - 576

- ↑ Ernst Ludwig Ehrlich in: Monumenta Judaica. 2000 years of history and culture of the Jews on the Rhine . Here “The Jewish order and the inner life of the Jewish communities”, 3rd Archbishopric Trier, p. 254 ff

- ↑ Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz, inventory 1C: files of the ecclesiastical and state administration. Case file 8171, protection money of the camera Jews, lists of the number of Jews, duration 1731–1782

- ↑ Adolf Kober, in: On the history and culture of the Jews in the Rhineland , section “From expulsion from the cities on the Rhine to the Enlightenment of the Modern Age”.

- ↑ State Main Archive Koblenz, inventory 1C files of the clerical and state administration

- ↑ State Main Archive Koblenz. Inventory 631, case file 10194 562-563

- ↑ Eduard Sebald and co-authors: The art monuments of Rhineland-Palatinate, Volume 9. The art monuments of the Rhein-Hunsrück district, part 2. Former district of St. Goar, here: City of Oberwesel , Jewish cemetery, p. 1024 f

- ↑ Christof Pies (inter alia): Jewish life in the Rhein-Hunsrück district , p. 169

- ↑ Ernst Ludwig Ehrlich in: Monumenta Judaica. 2000 years of history and culture of the Jews on the Rhine . Here “The Jewish order and the inner life of the Jewish communities”, 3rd Archbishopric Trier, p. 254 ff

- ↑ List of tables with information on the number of Jews in the departments on the left bank of the Rhine in the years 1806–1807 in: Zur Geschichte und Kultur der Juden im Rheinland , ed. Falk Wiesenmann, pp. 90 ff

- ↑ Files for the years 1677–1810. State Main Archive Koblenz. Inventory 631, case file 269

- ↑ a b Wilhelm Treue in: Monumenta Judaica. 2000 years of history and culture of the Jews on the Rhine . Here “The Development from 1815 to 1848”, p. 441 ff

- ↑ Inventory 631, factual file 315

- ^ Inventory 631, factual file 521

- ↑ Inventory 631, factual file 925

- ↑ Inventory 631, factual file 1464

- ↑ Christof Pies (inter alia): Jewish life in the Rhein-Hunsrück district , p. 169

- ↑ Eduard Sebald and co-authors: The art monuments of Rhineland-Palatinate, Volume 9. The art monuments of the Rhein-Hunsrück district, part 2. Former district of St. Goar, here: City of Oberwesel in Volume II, p. 980 f

- ↑ State Main Archive Koblenz. Inventory 631, fact sheet 521

- ↑ Christof Pies (inter alia): Jewish life in the Rhein-Hunsrück district , p. 94 f

- ^ René Richtscheid, Emil Frank Institute, 2010. René Richtscheid: "Know who you are standing in front of": The Wittlich Synagogue through the ages. P. 12

- ↑ LHA Koblenz inventory 631, factual file 523

- ↑ Elisabeth Moses, in: On the history and culture of the Jews in the Rhineland , "Jüdische Kult- und Kunstdenkmäler in den Rheinlanden", section architecture p. 103

- ↑ Angelika Schleindel, Jewish life in Wittlich . Exhibition catalog p. 38

- ↑ State Main Archive Koblenz. Inventory 631, case file 734

- ^ Wilhelm Treue in: Monumenta Judaica. 2000 years of history and culture of the Jews on the Rhine . Here “Persecution of the Jews during the Nazi era in the economic sector”, p. 459 ff

- ↑ State Main Archive Koblenz. Inventory 631, factual file 1597

- ↑ District administration Rhein-Hunsrück-Kreis: Statutory ordinances on the protection of monument zones in the Rhein-Hunsrück-Kreis (PDF; 49 kB); Retrieved October 26, 2013