Linden tunnel

| Linden tunnel | |

|---|---|

|

South portal of the east tunnel, 1950

|

|

| use | Tram tunnel |

| place | Berlin center |

| length |

Incl. Ramps:

Tunnel structure:

|

| vehicles per day | up to 120 trains / h and direction |

| Number of tubes | 1 |

| Largest coverage | 1.3 m |

| construction | |

| Client | City of Berlin |

| building-costs | 3,270,000 marks |

| start of building | August 6, 1914 |

| planner | Siemens & Halske |

| business | |

| release | December 9, 1916

West tunnel: December 17, 1916 East tunnel: December 19, 1916 |

| closure | West tunnel: November 9, 1923

East tunnel: September 2, 1951 |

| map | |

Plan of the Lindentunnel, 1914

|

|

| Coordinates | |

| North portal | 52 ° 31 '6 " N , 13 ° 23' 41" E |

| South portal west tunnel | 52 ° 31 '1 " N , 13 ° 23' 38" E |

| South portal east tunnel | 52 ° 31 '2 " N , 13 ° 23' 43" E |

The Lindentunnel is a partially filled in tunnel under the boulevard Unter den Linden in the Berlin district of Mitte . The tunnel, built from 1914 and opened on December 17 and 19, 1916, served the tram as an underpass for the boulevard and replaced an intersection at the same height that was put into operation in 1894. The building was used by trams until 1951, after which it was, among other things, a props store for the Berlin State Opera and parking space for vehicles of the East German People's Police . After German reunification , the action artist Ben Wagin used some parts as exhibition space, while other parts have been used as props at the Maxim Gorki Theater since the 1990s . A complete dismantling of the tunnel is planned in the medium term .

prehistory

Linden crossing

The boulevard Unter den Linden was legally a specialty in the Berlin road network. The streets, squares and bridges laid out in Berlin before 1837 passed into the property of the city on January 1, 1876 by law of December 1875. Exceptions existed among other things for Landes-Chausseen and the street Unter den Linden. In addition, the right of the German Emperor and Prussian King to have the last word on urban design matters.

The Great Berlin Horse Railway (GBPfE), founded in 1871, opened its first line from Rosenthaler Tor to Gesundbrunnen in 1873 . In the next few years, further routes followed from the former gates of the excise wall to the suburbs. The individual routes were linked by a ring line , the later line 1 - city ring, which followed the approximate course of the wall. It was the first north-south connection within Berlin. A second connection via Spandauer Strasse went into operation in 1883. The 2.2 kilometer long section between Spandauer Strasse and the Brandenburg Gate , in which the Unter den Linden street is located, was left out. The GBPfE tried for the first time in 1875 for a crossing of the "Linden" along Charlottenstrasse , which the Berlin police chief refused with reference to the narrow width of the street.

From the 1880s onwards, the GBPfE concentrated on further expanding its network. Since the central north-south connection was still missing, the management of the horse-drawn railway approached the police headquarters again in 1885 with the support of the Berlin magistrate . This rejected the project again and instead suggested a crossing at the level of the castle bridge over Schinkelplatz and Am Kupfergraben . The city then sent an immediate application to the Kaiser in 1888 , referring to the urgent need for a north-south tram connection. She proposed to lead the route through Friedrichstrasse , which should be widened sufficiently between Behrenstrasse and Dorotheenstrasse . The emperor recognized the urgency of the project, yet he rejected the plan submitted by the city. There were further negotiations about the location of the intersection; Those involved agreed on a connection at the level of the street Behind the Catholic Church , the square at the opera house and the chestnut grove (between the Palais des Prinzen Heinrich , Neuer Wache and Sing-Akademie ). The connection went into operation on September 22, 1894.

The company paid the city a lump sum of one million marks to establish the connection . She was thus exempt from the costs of purchasing the land . The city for its part got into a 20 year legal dispute with the university as the owner of the chestnut grove. The university demanded for the use of its 1810 by Friedrich Wilhelm III. transferred grove an annual pension of five percent of 1,526,800 marks. The sum corresponded to the value that the property would have achieved as building land . The city saw the chestnut grove only as a green area and wanted to reduce the price. The dispute ended in 1914 with a settlement under the rectorate of Max Planck . At this point in time the First World War had broken out and the construction of the Lindentunnel was certain. The city paid the sum of 1,069,250.86 marks to the university (adjusted for purchasing power in today's currency: around 4.31 million euros). On the instructions of the Prussian Finance Minister August Lentze, the latter had to spend the money on a war loan.

From 1896, the GBPfE began electrifying its route network, which it took into account in 1898 when it was renamed “Great Berlin Tram” (GBS). The power was supplied via the overhead line and roller pantograph . At representative places, including at the linden tree crossing, the overhead line was forbidden for aesthetic reasons. The GBS therefore initially used accumulator railcars, on October 7, 1901, they equipped the linden tree crossing with an underline (slotted pipe contact line). This type of power supply was unsatisfactory because the ducts quickly clogged with leaves and slush and the pantographs broke off at the smallest obstacle. The authorities therefore ordered the installation of emergency overhead lines in the winter of 1906/1907, which were replaced by permanent facilities in 1907. Due to the enormous width of the carriageway, the lines were guyed at the level of the street over a length of 60 meters without intermediate suspension.

Tunnel plans for the Great Berlin Tram and the City of Berlin

Since the linden intersection, which opened in 1894, quickly reached its limits, the city asked in vain for approval of a second intersection on Charlottenstrasse in 1897. The police chief suggested, however, an extension of the Kanonierstrasse to Neustädtische Kirchstrasse with a road break between Behrenstrasse and "Linden". The city then issued plans to implement the proposal. In April 1901, however, Kaiser Wilhelm II prohibited any further above-ground crossing of the boulevard. He is said to have marked the project documents with the remark “No, it will be done underground!”, The authenticity of the sentence cannot be proven. Alternatively, the emperor is also given the slogan “Underneath, not over it!” Which, according to other sources , was supposed to have applied to the construction of a suspension railway based on the Wuppertal model.

The time before the tunnel was built was marked by a strong rift between the city of Berlin and the Great Berlin Tram. The trigger for the conflict was the extension of the concession period to December 31, 1949, applied for by the GBS and approved by the police chief on May 4, 1900. The approval agreement concluded with the city, which regulated the use of the roads, ran until December 31, 1919 However, from the extension of the license, GBS generally derived the right to be allowed to run trams beyond 1919. As a result, there were several legal disputes , from which sometimes one party, sometimes the other, emerged victorious. Both sides went their own way in questions of traffic design. In 1900 the city decided to set up its own tram lines, and with regard to the linden tree crossing, both sides worked out different plans that included tunneling under the street at the level of the opera house. The morning edition of the Berliner Volks-Zeitung of December 11, 1904 presented the four variants - one urban and three from the GBS. The city revised its design under the leadership of city building officer Friedrich Krause and shortly afterwards presented two variants for a linden tunnel. The choice of location fell on the existing intersection, as the ramps could not have been built elsewhere or the costs of purchasing the land were too high. The tunnel carriageway was to have four tracks in order to be able to accommodate the lines of the GBS and its subsidiaries in addition to the lines of the city tram (SSB) and the Berlin electric trams (BESTAG) acquired by the city . In both designs, the north ramp was at the same height as the chestnut grove. In the first draft, the southern ramp was supposed to be to the east between the Opera House and the Prinzessinnenpalais , and in the second draft to the west between the Opera House and the Royal Library ("commode").

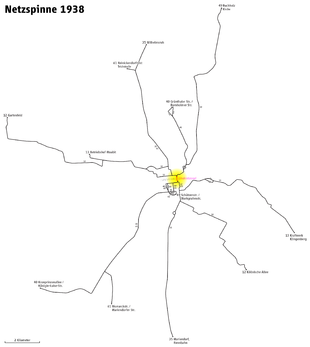

At the same time, GBS expanded its plans and, together with its subsidiary Berlin-Charlottenburger Straßenbahn, presented an extensive system of tunnel routes in 1905. They envisaged two tunnels running in an east-west direction, a southern one under Leipziger and Potsdamer Strasse and a northern one from the opera house to behind Siegesallee in the Tiergarten . The city criticized the plans as inadequate, whereupon the GBS changed them several times. The version from 1907 contained two loops in the north tunnel under the square at the opera house and the Brandenburg Gate, which were supposed to accommodate the north-south traffic. However, the city administration did not deviate from its criticism and relied on the results of several experts, including Gustav Kemmann and Otto Blum . City planning officer Friedrich Krause countered the GBS draft with a memorandum in which he proposed several short tunnels instead of two long tunnels, including at the opera house and the Brandenburg Gate, as well as numerous road openings. At a traffic conference on April 9, 1908, under the leadership of the Prussian minister of public works Paul von Breitenbach , he declared the appraisers' concerns about the GBS drafts to be justified and certified that the urban drafts were of great benefit. At an audience with the Emperor, Mayor Martin Kirschner of Berlin, it was ultimately determined that the north tunnel - with the exception of the north-south crossings - was unnecessary. For the south tunnel, however, further studies should be carried out. The tunnel projects were thus practically shelved .

- Tunnel designs 1904–1911

The GBS, however, initiated further lawsuits until a settlement with the city was reached in 1911. It was the basis for a new consent agreement. The contract was concluded on August 18, 1911. The city extended its approval period until December 31, 1939 and granted the company further rights with regard to the roads to be used and tariffs . The city, however, secured the right to acquire the company at certain times. An agreement on the tunnel issue had also been reached.

Construction work

Approval

Paragraph 45 of the consent agreement regulated the modalities for the construction of tram tunnels. The client was the city of Berlin. As a user of the systems, GBS was obliged to pay interest on the system costs at an annual rate of five percent. If other companies wanted to use the tunnels, they should share in the vehicle kilometers driven in relation to those driven by GBS. The city itself was extremely interested in a timely implementation of the Lindentunnel in order to be able to link its own lines - ending north and south of the tunnel - with one another. Initially, the city targeted one of its 1905 variants. The opera house and the neighboring Hedwig's Church criticized the construction of tram tracks between the two buildings, which would have been necessary in both cases. In order to avoid overloading the Französische Straße , a plan was made for a four-track tunnel with two separate southern ramps on both sides of the opera house. The east tunnel (opera tunnel) should be reserved for the lines of GBS, the west tunnel (Behrenstrasse tunnel), however, the lines of BESTAG and the city tram. In addition, the GBS lines coming from the northwest should also run through the west tunnel in order to avoid an intersection on the north ramp. In the event that the west tunnel was blocked, all lines would be routed through the east tunnel.

In February 1914, Wilhelm II granted the building permit for the project, which was submitted to the Berlin city council on April 17, 1914 for resolution. The construction costs were estimated at 3.27 million marks (adjusted for purchasing power in today's currency: around 13.19 million euros) including land purchase. The assembly approved the project on May 7, 1914, thereby authorizing the magistrate to sign the contract negotiated with the GBS. The police chief issued the last necessary permit on August 6, 1914, a few days after the outbreak of war . Preparatory work had previously started in July.

Description of the tunnel system

The east tunnel had a total length of 354 meters including ramps, the west tunnel a total length of 389 meters. The covered part measured 123 meters (east tunnel) or 187 meters. The ramps had a gradient of no more than 50 per thousand (1:20) with a length of 126 meters on the north ramp and 105 meters (east tunnel) and 77 meters (west tunnel) on the south ramps. The east and west tunnels ran together from Dorotheenstrasse to the level of the northern edge of the lane of the "Linden", where they split up. The clear width of the northern ramp was 11.60 meters, that of the southern ramps was 6.40 meters each. The center-to-center distance of the associated tracks was 2.60 meters, the center-to-center distance between the inner tracks in the four-track section was 2.90 meters. In the double-track tunnels, the clear width was 6.10 meters in the straight and widened to 6.215 meters in the curves. The four-track section was designed without intermediate supports for the first 15 meters and measured 11.90 meters clearance, on the following section with supports 12.30 meters. A shelter 45–70 centimeters wide was provided between the tracks. The smallest radius was 35 meters. The clearance height in the east tunnel was 4.65 meters, in the west tunnel 4.30 meters. According to the plans of GBS, the difference arose from the fact that double-deck trams should also run through the east tunnel . In the west tunnel, however, such an undertaking was not possible, as the building project was granted with the stipulation that the monument to Empress Augusta to be crossed would be left in place.

The tunnel floor was located entirely in the covered part, in the area of the ramps about halfway below the mean groundwater level . The deepest point in the east tunnel (28.39 meters above sea level ) was about 4.50 meters below the water table. Stamped concrete - Retaining walls with a thickness of 30-80 centimeters preconceived one the ramps at the top. In the part of the tunnel that is below the water table, a floor was inserted so that a U-shaped profile was created. A protective layer of sand mortar was used for waterproofing, over which an asphalt cardboard ceiling was laid. The walls above the water table and the ceiling were given a two-layer protective layer, the walls below the water table a three-layer and the bottom a four-layer design. The individual layers were glued together with asphalt compound. The thickness of the tunnel floor including the smoothing layer, concrete structure, seal and superstructure was 1.25 meters.

The ceiling in the two-track tunnels consisted of I-beams , which were arranged at a distance of one meter. In between, concrete caps at least 35 centimeters thick formed the actual ceiling. The walls here were 55 centimeters thick. In the four-track section with central supports, the distance between the I-beams was also one meter, the middle beams in turn rested on longitudinal beams, which were supported on the central pillars, each three meters apart. The wall here was 35 centimeters thick. In the four-track section without central supports, the I-girders were encased in concrete and arranged at a distance of 40 centimeters with a wall thickness of 66 centimeters.

The tracks consisted of 15 meter long grooved rails weighing 51 kilograms per meter. They were laid on wooden sleepers in gravel bedding at a distance of one meter. The overhead line consisted of profile copper wire with a cross-section of 80 square millimeters, it was attached to ceiling insulators . The contact line was suitable for both roller pantographs and hoop pantographs . The cable was suspended from cantilever masts on the ramps. A double contact line had to be laid on the south ramp of the west tunnel due to the steep incline. The tunnel had electric wall lights for lighting, which were shielded so that the light was only emitted upwards and downwards. The tram cars could do without their own lighting during the day.

As a result of the steep incline on the ramps and the restricted field of vision as a result of the curved track, there were several safety systems:

- On the ramps posted dispatchers had to make sure that the cars complied with the speed limit of 10 km / h was sufficient distance to the train.

- The dispatchers were in telephone contact with each other and with the depots.

- There were safety buttons in the tunnel that alerted the dispatchers and prevented further entries.

- Furthermore, operating stops were set up. During these compulsory stops, the train driver - the conductor in the railcar - had to check the correct coupling between the cars and to apply any handbrake, then he gave the departure signal.

- The conductors had to be ready to brake on the rear boarding platforms during the passage.

All in all, these measures meant that there were no serious disruptions to operations in regular operation.

In addition to these measures, the Königliche Eisenbahn-Direktion Berlin, as the technical supervisory authority , requested the installation of a signal system to show the drivers whether the section ahead is occupied or not. The signals were placed at a distance of 32 meters and indicated a red light when occupied and a green light when free. In the middle of the block points there were contacts that brought the signal from the drive to the stop position when driving. When driving through the next contact, the section was released again.

The service regulations for the tunnel that came into force in 1925 dealt with the signaling system; According to some literature sources, it is not known whether it was still in use at the time. Other sources assume that due to the compulsory stops, the prescribed maximum speed of 10 km / h and the prescribed minimum distance between two trains of 25 meters, no signaling was used in the end.

Special constructions

Below the northern lane of the "Linden", the tunnel floor was reinforced over a length of about ten meters in order to be able to dig an excavation below the tram tunnel for the construction of the Moabit - Görlitzer Bahnhof underground railway planned at the time. In addition, several supply lines of the Reichspost , the gas , electricity and waterworks crossed the tunnel. If possible, the ceiling was provided with corresponding arches in which the cables were laid. Because of the low ceiling height, stronger pipes had to be broken down into several weaker pipes. The sewer lines were led around the ramps. The walk-heating duct of the Opera House was gedükert .

On the south side of the avenue, the tunnel crossed under the monuments of Blucher east of the opera house and the Empress Augusta between the opera house and the “dresser” . For this purpose, foundation walls were led to the side of the tunnel walls to under the tunnel floor and support grids were placed over them at a small distance , which supported the base plates of the monuments. The tunnel ceiling was weakened in the sections. The monument to Auguste Viktoria also had to be raised by around 60 centimeters to create enough space for the ramp of the west tunnel.

Pump sumps with two centrifugal pumps each were installed in niches at the deepest points of both tunnels to divert the penetrating surface water into the sewer system . One pump each served as a reserve. The devices were activated automatically via float switches .

New construction of the Iron Bridge

At the same time as the tunnel was built, the new Iron Bridge was built over the Kupfergraben . Before the tunnel was built, the tracks led from the bridge in a straight line across the streets Am Festungsgraben and Hinter dem Gießhaus to the linden intersection. The construction of the north ramp required a detour via Dorotheenstraße and Am Kupfergraben . Since the old bridge was too narrow to accommodate the curved track in the direction of the street Am Kupfergraben, a new construction was necessary. The construction costs were estimated at 600,000 marks. On October 12, 1914, work began with the construction of an auxiliary bridge, which was completed on March 24, 1915. The old bridge was then demolished and the new bridge built. The abutments of the new bridge were erected in November 1915, and the building was accepted on December 9, 1916. In order not to obstruct through traffic, the trains of the Berlin-Charlottenburg tram that had previously been sweeping in Dorotheenstrasse were given a new turning system in the street Am Kupfergraben north of Dorotheenstrasse.

Construction process and commissioning

The actual construction work began on September 7, 1914 by Siemens & Halske . The work progressed relatively quickly at first, as many companies had to cease their normal contract operations as a result of the outbreak of war and there were now free capacities. In the course of 1915 there was a shortage of labor, as the remaining workers were usually called up for military service. As far as possible, women did the sometimes physically difficult work.

First of all, the later excavation pit was covered with steel girders and planks over which the roadway of the "Linden" would later lead. After its completion in December 1914, road traffic could be handled again almost unhindered. Then the excavation work began . Since the east tunnel ran roughly in the direction of the old linden tree crossing, the tracks of the above-ground crossing had to be swiveled eastwards during the construction work. On both sides of the construction pit, I-beams were rammed into the ground at a distance of 1.5 meters up to 1.5 meters below the base and stiffened against each other two meters above the base and 3 centimeters below the terrain. Wooden planks were then inserted between the girders. In the area of the university, the tunnel walls protruded up to half a meter from the foundation walls of the east wing. In order to prevent parts of the building from settling , the tension with which the planks were pressed to the ground was increased by means of arched metal sheets riveted between iron posts. The convex side of the arch faced the foundation of the university. The excavated material was loaded onto tipping trucks and driven by a locomotive with benzene as the fuel to the Kupfergraben, where a barge loading point was built.

The breakthrough in the west tunnel took place on January 3, 1915 . From the beginning of February 1915 the lowering of the groundwater could begin, the pumps were at a distance of five to six meters and directed the water into the nearby Spree . The excavation continued until May 1915, after which work on the floor and the tunnel walls began. The installation of the ceiling began on October 22, 1915. In January 1916, the pumps for lowering the groundwater could be removed again. From January 17, 1916, the last phase of construction for the north ramp began. For this purpose, the eastern access to the linden intersection via the streets Am Festungsgraben and Hinter dem Gießhaus was blocked and the trams were led from the Iron Bridge over the streets Am Kupfergraben and Dorotheenstraße to the Kastanienwäldchen.

In June 1916, the sealing and concreting work was so far completed that the construction of the track could begin. In addition to the actual track bed, this included the centrifugal pumps mentioned, the tunnel lighting, ramp railings and the catenary masts integrated in them, as well as the signaling system required by the supervisory authority. The ramps were largely hidden from view of passers-by with beds and hedges.

The building handover took place on December 9th, 1916 in the presence of the representatives of the Berlin police headquarters and the Royal Railway Directorate in their function as supervisory authorities, the Friedrich Krause city building council, representatives of the Greater Berlin Association and the directors of the three tram companies. Those present walked through the tunnel in both directions before it was used by two city trams. Since there were minor complaints about the tunnel's signaling system, the start of operations was postponed to a later date. Regardless of this, the city of Berlin celebrated the inauguration of the tunnel by Mayor Adolf Wermuth the following day . On the railing above the northern entrance, the latter revealed two memorial plaques. On the side facing the ramp it said: "Linden Tunnel - Built by the City of Berlin". On the side facing the street it could be read: “The construction of the Lindentunnel began under the government of Emperor Wilhelm II in 1914. Despite the World War, construction continued as planned and the tunnel was opened to traffic in 1916. ”The first memorial plaque has been preserved, but the second no longer.

Problems were still caused by the GBS roller pantographs, which did not reliably trigger the signal contacts. Since the three companies had agreed on a joint start-up, the urban lines did not go through the tunnel yet. December 14, 1916 was initially set as the new commissioning date, and when the problem persisted, December 16, 1916. Since the work on the vehicles had not been completed by then, the municipal companies started traffic on their lines the next day open the west tunnel. Lines 33, 40, 42, 44, 53, 54, 55 of the GBS and line III of the SBV used the east tunnel two days later on December 19, 1916, and lines 12, 18, 32, 43 of the used from that day GBS the west tunnel. The linden tree crossing above ground went out of service on the same day.

Use of the tunnel

tram

The tunnel never reached the intended capacity utilization of 120 trains per hour and direction. As a result of the First World War, the timetable was very limited when construction began. Further lines of the city tram, which should also use the tunnel, were not implemented. With the gradual amalgamation of the individual companies under the Greater Berlin Act to create the Berlin tram in December 1920, the offer initially remained the same. The progressive hyperinflation meant that the still young company had to stop tram traffic on September 8, 1923. The following day went down in Berlin traffic history as a "tram-free day". On September 10, 1923, the Berliner Straßenbahn-Betriebs-Gesellschaft began operating on a trunk network of 32 or 33 lines. At first there was no line through the linden tunnel; the west tunnel was completely shut down from this point in time and its tracks were expanded in the 1920s.

About half a year after the cessation of operations, line 32 ( Reinickendorf , Pankower Allee - Neukölln , Knesebeckstraße) ran again on March 31, 1924 through the east tunnel. In the following years, an average of four to five lines ran through the passage. Since the first section of the north-south railway went into operation in January 1923 , some of the passengers migrated to the subway . The west tunnel was thus dispensable and after the "tram-free day" in 1923 it remained without tram traffic in the following period. In 1926, as part of the redesign of Kaiser-Franz-Joseph-Platz on the occasion of the expansion of the opera house, it was closed with a leg wall, the ramps filled in and the area leveled.

The commissioning of the GN-Bahn as the second north-south line led to further line adjustments in the tram network. During the Second World War and the associated fuel rationing, the Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG), which emerged from the Berlin tram in 1929, replaced various bus routes with tram routes. With up to ten lines, the tunnel reached its highest capacity after inflation. In the further course of the war, the offer steadily decreased again before - according to literature from 1964 - in the spring of 1945 the last lines 12 (most recently Gartenfeld and Siemensstadt - Dönhoffplatz ) and 13 (most recently Moabit , Wiebestrasse - Klingenberg power plant ) after one Damage to the south ramp had to be stopped. According to information from 2012, with the last emergency timetable from January 25, 1945, the last line running through the tunnel was line 12 (until then lines 12, 35 and 61), which was also only operated during rush hour. It was still in service on April 12, 1945, until it was shut down shortly afterwards in the last days of the war.

By Allied bombing , the tunnel was badly damaged in a total of five points.

The restart after the end of the war was initially a long time coming, as other routes had priority. The Berliner Zeitung reported that one day after the opening of the 1st German Youth Meeting, the tunnel would be used again from May 26, 1950 on line 46 ( Nordend - Dönhoffplatz). About a year and a half later, the BVG stopped traffic after the III. World Festival of Youth and Students on September 2, 1951. The closure was in connection with the reconstruction of the State Opera , whose directorate building was to be enlarged and thus protruded into the building line of the south ramp. In the following years there were isolated plans to build a new south ramp with a confluence with Oberwallstraße. With the removal of the tram from the city center south of the light rail viaduct , the plans soon became obsolete. The north ramp was used to sweep tram trains into the 1960s .

Other uses and renovations until 1989

The west tunnel was used in the 1930s for lighting tests that were carried out as part of the redesign of Berlin to become the world capital Germania . The findings were to be incorporated into the construction of a road tunnel at the Brandenburg Gate . After its abandonment, the east tunnel was initially used as a backdrop for the State Opera. The components of the grandstand set up on Marx-Engels-Platz were later stored here. When a heating channel was built beneath the road in the 1960s, the profile height of the tunnel was restricted. The road north ramp received in the 1960s, paving with which the tunnel was opened for road vehicles. Furthermore, the tunnel walls and ceiling were painted white and modern lighting and an emergency power supply were installed. Initially, the factory combat group of the GDR Foreign Trade Ministry parked vehicles and equipment, and later the People's Police vehicles were also located here. In a separate room at the end of the west tunnel there was a switchgear for the operational television of the People's Police, with which the Ministry for State Security, among other things, monitored important points in East Berlin .

After 1990

After the political change , the tunnel filled with rainwater after a pump failed, before various artists "rediscovered" it from 1994 onwards. From 1994, the action artist Ben Wagin used most of the tunnel for his installations. Among other things, in the run-up to the UN climate conference in Berlin , he set up the Reko car 217 053, which was handed over by BVG on July 15, 1994, on the north ramp.

In the mid-1990s, the Berlin Senate planned the construction of an underground car park under Bebelplatz, for which the linden tunnel was to serve as an access. The erection of a memorial to the book burning in Germany in 1933 in the area of the southern ramp in the middle of Bebelplatz changed these plans. The remains of the tunnel under the square were completely removed for its construction. In December 1998, Ben Wagin had to relocate the installations that had already been made to a loading hall at Gleisdreieck underground station . After backfilling, the square of the March Revolution was built on the area . The memorial plaque on the north side of the ramp railing came into the possession of the Berliner Unterwelten Association . The southern driveway on the west side of Unter den Linden has been partially exposed and a corresponding information board has been set up.

In 2000 there was another "attempt at revitalization": The Lindentunnel was to serve as an exhibition area for a Berlin museum to be created on the initiative of Wieland Giebel . This project also failed.

Since September 2002, the Maxim-Gorki-Theater has been using an approximately 80-meter-long section of the tunnel from the north ramp as a set store. The props can one into the pavement embedded freight elevator transported.

The planned underground car park was built from 2003. For this purpose, the west tunnel between the southern sidewalk of the "Linden" and Behrenstrasse had to be demolished. The remaining part is accessed via a door in a connecting passage between the underground car park and the State Opera.

During the renovation work on Unter den Linden in 2005/2006, the remaining parts of the tunnel were sealed. Structural defects such as strong movement cracks and concrete spalling made the installation of emergency supports necessary. After the completion of the extension of the U5 underground line crossing under the Linden tunnel , a partial demolition is planned. In the medium term, the tunnel is to be completely demolished.

Lines that ran through the tunnel

| operator | line | course | Ref | Web spider |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| September 1, 1911 |

|

|||

| GBS | 12 | Plötzensee - Görlitz train station | ||

| 13 | Moabit , Bremer Strasse - Neukölln , Knesebeckstrasse | |||

| 18th | Jungfernheide train station - Görlitzer train station | |||

| 20th | Beusselstraße station - Neukölln, Hertzbergplatz | |||

| 33 | Pappelallee / Schönhauser Allee - Charlottenburg , Kantstraße / Leibnizstraße (- Witzleben , Neue Kantstraße / Dernburgstraße) | |||

| 34 | Pankstrasse / Badstrasse - Wilmersdorf , Wilhelmsaue | |||

| 39 | Badstrasse / Exzerzierstrasse - Marheinekeplatz | |||

| 40 | Swinemünder Strasse / Ramlerstrasse - Schöneberg , Eisenacher Strasse | |||

| 42 | Seestrasse / Amrumer Strasse - Marheinekeplatz | |||

| 43 | Müllerstrasse / Seestrasse - Schöneberg, Eisenacher Strasse | |||

| 44 | Schönhauser Allee / Gleimstrasse - Kreuzberg , Bergmannstrasse | |||

| 53 | Danziger Strasse / Weißenburger Strasse - Neukölln, Steinmetzstrasse | |||

| 54 | Schönhauser Allee station - Jungfernheide station | |||

| 55 | Danziger Strasse / Weißenburger Strasse - Britz , town hall | |||

| SBV | III | Swinemünder Strasse / Ramlerstrasse - Schöneberg, General-Pape-Strasse | ||

| December 19, 1916 | ||||

| West tunnel | ||||

| BESTAG | o. no. | Buchholz , Church - Treptow , Graetzstrasse | ||

| o. no. | Pankow , Damerowstrasse / Mendelstrasse - Treptow, Graetzstrasse | |||

| SSB | Urban east ring | |||

| GBS | 12 | Plötzensee - Görlitz train station | ||

| 18th | ( Siemensstadt , administration building -) Jungfernheide station - Görlitzer station | |||

| 32 | Reinickendorf , town hall - Görlitz train station | |||

| 43 | Seestrasse / Müllerstrasse - Schöneberg , Mühlenstrasse | |||

| East tunnel | ||||

| GBS | 33 | Weißensee , Prenzlauer Promenade - Witzleben , Neue Kantstrasse / Dernburgstrasse | ||

| 40 | Swinemünder Strasse / Ramlerstrasse - Schöneberg, Hauptstrasse / Eisenacher Strasse | |||

| 42 | Seestrasse / Amrumer Strasse - Friesenstrasse / Schwiebusser Strasse | |||

| 44 | Schönhauser Allee / Gleimstraße - Neu-Tempelhof , Hohenzollern Parade / Deutscher Ring | |||

| 53 | Danziger Strasse / Weißenburger Strasse - Neukölln , Steinmetzstrasse | |||

| 54 | Nordkapstraße - Jungfernheide train station (- Siemensstadt, administration building) | |||

| 55 | Danziger Strasse / Weißenburger Strasse - Britz , town hall | |||

| SBV | III | Swinemünder Strasse / Ramlerstrasse - Schöneberg, General-Pape-Strasse | ||

| May 1, 1938 | ||||

| BVG | 12 | Gartenfeld or Siemensstadt, administration building - Neukölln, Köllnische Allee | ||

| 13 | Moabit , Wiebestraße - Klingenberg power plant | |||

| 35 | Wilhelmsruh , main street - Mariendorf , racecourse | |||

| 40 | Grünthaler Strasse / Bornholmer Strasse - Dahlem , Kronprinzenallee / Königin-Luise-Strasse | |||

| 49 | Buchholz, church - Schützenstrasse / Markgrafenstrasse | |||

| 61 | Reinickendorf-Ost, Teichstrasse - Steglitz , Stadtpark | |||

| May 26, 1950 | ||||

| BVG (East) | 46 | Nordend , tram station - Mitte , Dönhoffplatz | ||

Remarks

- ↑ 1910–1947: Kaiser-Franz-Joseph-Platz, since 1947: Bebelplatz

- ↑ since 1952: Maxim-Gorki-Theater

- ^ Since 1951: Glinkastraße

- ↑ depending on the source

- ↑ Line U6

- ↑ Line U8

- ↑ since 1994: Schloßplatz

literature

- The tram tunnel under the linden trees in Berlin . In: Deutsche Bauzeitung . No. 30, 31, 33 . Berlin 1916.

- M. Dietrich: The tram tunnel "Unter den Linden" in Berlin . In: German street and small train newspaper . 1917, p. 269-274 .

- Hans-Joachim Pohl: The linden tunnel . In: Verkehrsgeschichtliche Blätter . No. 7 , 1980.

- Rüdiger Hachtmann , Peter Strehlau: The tram tunnel Unter den Linden . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 12 , 1994.

- Ulrich Conrad: Literally “under the linden trees” . In: Tram magazine . No. 10 , 2012.

- Jürgen von Brietzke: Tunnel planning of the great Berlin tram 1905-1910. In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter. Issue 1, 2017.

Web links

- The linden tunnel . In: berliner-unterwelten.de

- Photo: Looking down the north ramp, ca.1930 at Getty Images

- Photo: Construction of the south-eastern ramp with a view of the Neue Wache , around 1916 at Getty Images

- Photo: Tunnel ramp with tram (possibly with press for opening) , approx. 1916 at Getty Images

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Rüdiger Hachtmann, Peter Strehlau: The tram tunnel “Unter den Linden” . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 12 , 1994, pp. 139-244 .

- ↑ a b c d Hans-Joachim Pohl: The Lindentunnel . In: Verkehrsgeschichtliche Blätter . No. 7 , 1980, pp. 134-136 .

- ↑ a b c The tram tunnel under the linden trees in Berlin . In: Deutsche Bauzeitung . No. 30 . Berlin April 12, 1916, p. 157-159 .

- ↑ a b c d Hans-Joachim Pohl: The Lindentunnel . In: Verkehrsgeschichtliche Blätter . No. 7 , 1980, pp. 136-140 .

- ↑ a b c d e Lindentunnel. (No longer available online.) In: berliner-unterwelten.de. Berlin Underworlds , archived from the original on April 17, 2016 ; Retrieved April 24, 2016 .

- ↑ Michael Mälicke: The Wupper Valley - pacemaker in local public transport . In: Wuppertaler Stadtwerke (ed.): The Wuppertaler suspension railway . 2nd Edition. Wuppertaler Stadtwerke, Wuppertal 1998, p. 9-22 . Without ISBN.

- ^ The tunneling under the "Linden" . In: Berliner Volks-Zeitung . Second supplement . No. 581 , December 11, 1904.

- ↑ a b Peter C. Lenke: Much discussed, but never realized transport projects: The tunnel projects of the Great Berlin Tram from 1905–1908 . In: Verkehrsgeschichtliche Blätter . No. 2 , 2004, p. 30-36 .

- ↑ The Great Berlin Tram and its Branch Lines 1902–1911 . Unchanged reprint 1982. Hans Feulner, Berlin 1911, p. 11-20 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Hans-Joachim Pohl: The Lindentunnel . In: Verkehrsgeschichtliche Blätter . No. 7 , 1980, pp. 140-146 .

- ↑ a b The tram tunnel under the lime trees in Berlin . In: Deutsche Bauzeitung . No. 31 . Berlin April 15, 1916, p. 161-164 .

- ↑ a b c d The tram tunnel under the lime trees in Berlin . In: Deutsche Bauzeitung . No. 33 . Berlin April 22, 1916, p. 173-176 .

- ↑ Berliner Straßenbahn-Betriebs-GmbH (Ed.): Service instructions for tram operation in the tunnel under Kaiser-Franz-Joseph-Platz (so-called Linden tunnel) . April 1, 1925, p. 1–10 ( berliner-verkehrsseiten.de [PDF; accessed on February 14, 2016]).

- ↑ a b c d Ulrich Conrad: Literally “under the lime trees” . In: Tram magazine . No. 10 . Berlin 2012, p. 72-75 .

- ^ Christian Winck: The tram in the Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf district . VBN Verlag B. Neddermeyer, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-933254-30-6 , pp. 4-19 .

- ^ W. Lesser: Sheet pile walls for excavations next to existing buildings. In: Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung , Berlin, No. 53, July 1, 1916, pp. 366–367 Online web archive ( Memento from April 24, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ A b Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the Berlin tram 1902–1945. 18th episode . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 8 , 1965, p. 113-115 .

- ↑ a b c Hans-Joachim Pohl: The Lindentunnel . In: Verkehrsgeschichtliche Blätter . No. 7 , 1980, pp. 146-149 .

- ^ Tietze: Conversion and extension of the State Opera in Berlin. II. The construction work ( Memento from April 24, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) In: Zeitschrift für Bauwesen . Verlag Guido Hackebeil Berlin / Leipzig, July 1928, pp. 167–182.

- ^ A b c Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the Berlin tram 1902–1945. 6th episode . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 6 , 1967, p. 77 .

- ^ A b Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the Berlin tram 1902–1945. 7th episode . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 7 , 1964, pp. 89-90 .

- ^ A b Hans-Joachim Pohl: The linden tunnel . In: Verkehrsgeschichtliche Blätter . No. 7 , 1980, pp. 149-150 .

- ^ A b c Jürgen Meyer-Kronthaler: Lindentunnel - a new chapter . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 2 , 2005, p. 19-20 .

- ↑ Uwe Aulich: Lindentunnel: Wargin's move is delayed . In: Berliner Zeitung . September 29, 1998 ( berliner-zeitung.de [accessed April 24, 2016]).

- ↑ The Lindentunnel. (No longer available online.) In: Berlin Story. Wieland Giebel, archived from the original on May 8, 2016 ; Retrieved April 30, 2012 .

- ↑ Uwe Aulich: Lindentunnel is now a scenery warehouse . In: Berliner Zeitung . September 20, 2002 ( berliner-zeitung.de [accessed April 24, 2016]).

- ↑ Construction site slalom run Unter den Linden . In: Der Tagesspiegel . January 14, 2006 ( tagesspiegel.de [accessed April 24, 2016]).

- ↑ Printed matter 17/13171. (PDF) Berlin House of Representatives, March 26, 2014, accessed on April 6, 2014 .

- ↑ Printed matter 17/13711. (PDF) Berlin House of Representatives, May 14, 2014, accessed on May 29, 2014 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n The Great Berlin Tram and its Branch Lines 1902–1911 . Berlin 1911, p. 88-108 .

- ^ A b Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the Berlin tram 1902–1945. 5th episode . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 5 , 1964, pp. 61-62 .

- ^ A b Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the Berlin tram 1902–1945. 10th episode . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 10 , 1964, pp. 134-135 .

- ^ A b c Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the Berlin tram 1902–1945. 19th episode . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 9 , 1965, pp. 124-125 .

- ^ A b c Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the Berlin tram 1902–1945. 23rd episode . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 1 , 1966, p. 13-14 .

- ^ A b c d Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the Berlin tram 1902–1945. 24th episode . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 2 , 1966, p. 26-27 .

- ^ A b Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the Berlin tram 1902–1945. 25th episode . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 3 , 1966, pp. 41-42 .

- ^ A b c d Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the Berlin tram 1902–1945. 32nd episode . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 11 , 1966, pp. 165-166 .

- ^ A b Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the Berlin tram 1902–1945. 34th episode . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 2 , 1967, p. 35-36 .

- ^ A b Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the Berlin tram 1902–1945. 66th episode . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 11 , 1969, p. 202 .

- ^ A b Heinz Jung: The Berlin Electric Trams AG . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 11 , 1965, pp. 146-150 .

- ^ Hans-Joachim Pohl: The urban trams in Berlin. History of a municipal transport company . In: Verkehrsgeschichtliche Blätter . No. 5 , 1983, pp. 98-106 .

- ^ Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the Berlin tram 1902–1945. 20th episode . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 10 , 1965, p. 140-141 .

- ^ Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the Berlin tram 1902–1945. 30th episode . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 9 , 1966, pp. 129-130 .

- ^ Heinz Jung, Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the Berlin tram 1902–1945. 39th episode . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 7 , 1967, p. 129-130 .

- ^ Wolfgang Kramer: Line chronicle of the Berlin tram 1945–1993 . Ed .: Working Group Berlin Local Transport. Berlin 2001, p. 95-96 .