Palatinate Wimpfen

The former royal palace in Wimpfen is 215 meters long, up to 88 meters wide and originally with three mountain tombs, the largest Hohenstaufen palace complex in Germany. It is located on a mountain spur above the Neckar in a strategically advantageous location. In the north, east and south, the Palatinate is still surrounded by an almost closed wall. Construction work began under Friedrich I. Barbarossa (1152–1190) shortly after the middle of the 12th century. Construction stopped in 1190 or 1197 at the latest. Under Frederick II (1212–1250), a second construction phase began after 1217, which was possibly continued under Henry (VII) . Most likely in 1320/22 the Palatinate was largely destroyed and after the first third of the 14th century hardly used by royalty. In the course of time it merged with the town to the west, in which the former Palatinate area now forms the so-called castle district.

location

The Königspfalz in Wimpfen was built on the ridge of the Eulenberg rising from the Neckar valley to the Kraichgau , above the Wimpfen settlement in the valley. In the north and east it was protected by the steep slope, in the south a stream formed a natural ditch.

history

Wimpfen im Tal was already a city-like, walled settlement on a Neckar crossing in Roman times . Here the Odenwald Limes began , which continued the Neckar Limes northward to the Main. The area around Wimpfen became a Franconian royal estate in the 6th century . The Bishop of Worms had a strong influence there very early on, and later also possessed it. Worms founded the pin Wimpfen , the 965 gained market rights and as the oldest preserved part the west wing of the Collegiate Church of St. Peter is considered the 11th century. The Wimpfener Stiftspropst was also Worms archdeacon for Elsenzgau and Gartachgau . In order to reclaim and secure lost old royal property, the Staufer built a palace in Wimpfen, to which the mining town adjoined to the west. The settlement of Wimpfen am Berg and the later Palatinate area dates back at least to the early eighth century.

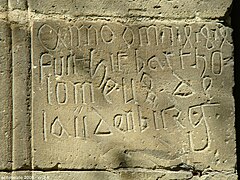

Emperor Friedrich I. Barbarossa is the presumed founder of the Palatinate; There are no written messages about the start of construction. On February 9, 1182, his stay in Wimpfen is documented. If you look at its itinerary , it should also have been drawn by Wimpfen in 1154, 1164, 1188 and 1189; he could have checked the major construction site there, or he came to the inauguration of an important building in the Palatinate, because archaeological findings have shown that major construction work took place on this area after the middle of the 12th century.

Friedrich's son, Emperor Heinrich VI. (1190–1197), was verifiably three times in Wimpfen, Emperor Friedrich II at least eight times. His rebellious son Heinrich (VII.) Submitted to him in 1235 in Wimpfen. Heinrich (VII.) Is frequently recorded in Wimpfen, a total of fourteen times. After the Hohenstaufen, Rudolph von Habsburg visited Wimpfen in 1282, his wife, Queen Anna, came in 1284, and Adolph von Nassau in 1197 . Albrecht I is recorded in 1300, 1305 and 1306; Henry VII. 1309; Ludwig the Bavarian (1314–1347) 1315, 1336 and 1346. His counter-king Friedrich the Beautiful (1314–1330) stayed in 1320 in Wimpfen. Here he issued privileges, received messengers and recruited high-ranking followers for his fight against Ludwig the Bavarian. The visits to the kings during this time may not all have taken place in the Palatinate, but some may also have taken place in the Wormser Hof or in the knight's monastery in Wimpfen im Tal.

After the fall of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, the royal palace was also the seat of the imperial governor . Konrad IV von Weinsberg served in this capacity until 1320 on the side of Ludwig of Bavaria and then on the side of the enemy. Presumably it was he who opened the Palatinate to Frederick the Beautiful in the disputes of 1320/22. At that time there was probably a strong extensive fire that ruined the Palatinate; the original Palasarkaden and the western front of the Palatine Chapel still show traces. During the excavations in 1983 and 2008, a layer of fire was discovered, overlaid by broken hollow bricks with finds from the 14th century. This fire event led to the abandonment of the Palatinate and the demolition of the palace and a keep. News makes it clear that the Palatinate was hardly used by royalty after 1333: Engelhard VII von Weinsberg , the son of Conrad IV, sold part of his conglomerate of property in 1336, probably with the keep, which was later demolished, to the city of Wimpfen. The houses in the moat mentioned in 1347 document the task of the fortification. In 1359 a canon bequeathed the “stone house” next to the palace to the Schöntal monastery . In 1365, Emperor Charles IV noticed that the meetings of the Imperial Bailiwick had not taken place in the Palas for a long time. In 1391 barns are mentioned in the Palasareal. All the news illuminates the decline of the Palatinate in the 14th century.

Buildings

Hall

The Palas , a representative hall building, was the central building of the Palatinate. From the rising masonry only the northern and eastern wall is up to the ceiling of the upper floor received. The east wall - at the same time the west wall of the Palatine Chapel - runs three meters to the south beyond the line of the southern chapel wall and forms a corner at the end. The foundations of the south wall run more than four meters further south, so that an indentation was created in the southeast corner of the building, perhaps the space for a staircase construction. In 2007 the Alt-Wimpfen association excavated a foundation in the basement of the 19 Burgviertel building west of the hall; Adjacent finds date it to soon after 1150. It was most likely the previously undiscovered foundation of the west wall. The hall was about 36 meters long and 16.70 meters wide.

In the preserved north wall you can see the three arcade windows of the hall with their fourteen arcades on the upper floor, through which you can see the Neckar valley. The arches made of smooth wedges rest on warriors , each supported by two squat columns. The pillars , mostly with a disk cube capitals , are mostly without decoration underneath the simple shaft ring and have Attic bases . On the ground floor there are four light slots below the arcades.

To the west of the arcades sits a large round arched biforium with a circumferential bar profile and a central column that corresponds to the arcade columns up to its length. This window lit a room next to the hall. A little further to the west there were two arched entrances with the same profile as the biforium on the upper floor. The door leaves were hinged on the inside, unlike the two doors on the first floor. Here the western door is higher than the eastern one, which on the facade of Romanesque buildings indicates an exterior staircase. The north side of the hall with these two doors on the ground floor was probably protected by a kennel . During the excavations in 2007, the western section of the wall with the interlocking for a wall that ran to the east was discovered. It is not unlikely that the palas had an additional floor, as the original wall height of the building is not known. The second door upstairs might lead to a staircase. According to Ludwig Hildebrandt and Nicolai Knauer, the Palas was built shortly after the middle of the 12th century within the still existing surrounding wall of an older fortification . The construction was completed by the 1170s at the latest.

At the same time as the palace, a donjon was built on the southwest corner of the Palatinate, which secured the endangered western flank and part of the southern flank. Its foundations were found in the 1980s during the renovation of the Mayor Elsässer House that is located there today.

Palatine Chapel

After 1160, the palatine chapel adjoining the palas consisted of a rectangular nave with a semicircular apse adjoining it to the east as the end of the choir . It was dedicated to St. Nicholas of Myra . The entrance portal was on the south side. Here and on the north side there were three arched windows and a biforium. The lower part of the north wall had only simple slits of light. The two biforas in the western part of the chapel brought light to the gallery , from which a door led to the upper floor of the palas. King Ludwig the Bavarian gave the chapel to the Benedictine monastery in Sinsheim in 1333 . Presumably during this time, a rectangular Gothic choir with an attached sacristy was built instead of the Romanesque choir with a semicircular apse .

Even before the Thirty Years' War the chapel when it was finished - and warehouse used during the war moved temporarily Capuchin and then she again served as a warehouse. The building was sold to citizens of Wimpfen in 1833, who used it from 1837 after it had been converted into a three-storey residential building with stables. Two further entrances had been broken into the south wall and five rectangular windows each into the two upper floors. Except for one window and the biforium in the north wall, the old windows were destroyed.

From 1909 to 1911 the chapel was restored to its old condition, with the choir being rebuilt in its Gothic form. The rectangular windows have been removed; the new arched windows and the biforium on the south side were given their shape after the preserved windows on the north side. The south side of the chapel is clad with sandstone blocks . The wall is structured by slightly protruding pilaster strips that merge into a round arch frieze above the window . The half-columns of the two biforas with base, shaft and capital provide important clues for dating. The prehistorian S. Frey determined the consecration of the Palatinate Chapel on June 14, 1192 based on the patronage function. A church history museum is now located in the former palatine chapel.

North wall shared with Palas

Romanesque house

Opposite the Palatine Chapel is the Romanesque House , the original condition of which has been greatly changed: in 1525 it was rebuilt by the Erer family. The coat of arms of this bourgeois family from Heilbronn - who provided a mayor there several times - adorns the northwest corner of the house. The upper floor was renewed around 1765 in half-timbered construction , with the building being divided in the middle.

Only parts of the north and south walls and perhaps also the east wall of the ground floor have been preserved and probably the barrel vaulted cellar. The walls are about eighty centimeters thick and the base is almost square with sides of 9.50 and 8.40 meters. The partially preserved Facilities surprised: The semicircular arched entrance with its revolving bar profile corresponds exactly to the two doors obtained in the upper floor of the palace . The central column of a biforium in the south wall has an Attic base with corner leaves , the octagonal shaft has a zigzag pattern and the capital is richly decorated. This lavishly decorated column was certainly made in the second half of the 12th century ; it is now in the museum in the stone house . Fritz Arens interprets the Romanesque House as a former castle man's seat .

Red Tower

The Red Tower is a preserved keep that was built on the eastern tip of the Palatinate. It is 23 meters high and has a footprint of around ten by ten meters. Three construction phases can be recognized by the different stones in the outer wall. The lower area is clad with high quality sandstone humpback blocks that have been carefully placed. The edge of the cuboid is narrow, the bosses are left rough and of very different heights. These features date the tower base to the second half of the 12th century. The entrance is on the north side at a height of 6.90 meters. It can be reached from the battlements via a bridge or from the ground via a ladder.

The arches above the entrance and the niche next to it are constructed from large arch stones. On the entrance front, the mirrors of the sandstone blocks are smoothed from the door threshold to three layers of stone above the door arch. This area probably had a wooden porch that may have been covered. Above this section, the building material changes to large blocks of tuff , some of which are also embossed, whereby the bosses appear less coarse; in addition, an increase in the edge impact width can be seen. Both tendencies point to the first quarter of the 13th century. The tower has a wall thickness between 2.70 and 3.20 meters, so that there is a space of around four by four meters inside. The entrance floor is also clad with smooth sandstone blocks up to a height of around three meters. Where the outer shell of the masonry changes from sandstone to tuff stone, the inner shell was clad with coarse shell limestone . This dividing line even runs through the chimney on the east wall, the shell of which is made of sandstone at the bottom and tuff at the top. Two half-columns in front of the back wall, with a simple, disc-cube capital typical of the 12th century, support the cheeks and fighters . The large niche in the west wall with an oculus probably does not belong in the original building concept, as it penetrates easily into the south wall. The niche is lined with sandstone, but its vaulting with a flat arch that protrudes into the upper section of the building points to the 13th century. The access to the lavatory bends several times and ends on the east side of the tower in a beehive-shaped bay , which comes from the second construction phase. A few meters below the bay is the opening for the original drainage through a tube running in the wall.

Work on the Red Tower was probably started in the late 1170s or in the 1180s and stopped with the death of Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa in 1190, but no later than 1197, with the death of Henry VI, and only resumed in 1217 after the Hohenstaufen rule was regained.

In the late Middle Ages , the tower was raised by four meters using shell limestone. The corners of this area are beveled, and the openings are no longer vents, but loopholes . The tower burned down in 1645, only the massive masonry remained. During the Second World War , the two lower floors were used as air raid shelters . The wooden balcony in front of the high access door was reconstructed in 1976. Today the tower is home to an exhibition on life in medieval Wimpfen, which is open during the summer months on weekends and public holidays. The tower's observation deck can also be climbed at these times .

Stone house

The stone house built after 1217 was the largest residential building in the Palatinate. It was built over the pre-Staufer enclosing wall and connected to the north-east corner of the Zwinger by a wall. There are indications that a residential tower from the Pre-Hohenstaufen era still stood on its east side when it was built. In the stone house of original input is received, one with a round arch and jambs featured portal of red sandstone near the southeast corner. Below its threshold you can see part of the masonry from the foundation; originally you came into the house at ground level. In manorial buildings at that time the ground floor was mostly used for economic purposes. The living area on the upper floor was reached via a separate staircase, which presumably led to a wooden porch near the stone house. A hooked console made of red sandstone on the southeast corner and the severed western counterpart make this likely. The door to the upper floor was perhaps in the place of the five-meter-wide seven-part window that was built in around 1400, or perhaps in the area of the small rectangular window next door, as the masonry reveal of an opening can be seen there. The arched biforium on the south side and some windows on the north and west sides of the building date from the time it was built. The lintel , walls, ledge and the rectangular support in the biforium are each monolith made of yellow and red sandstone. In the east wall of the north-east corner of the building, a round-arched door has been preserved, which undoubtedly led to the battlement. The chimney cheeks protruding from the wall on the upper floor date from the same period. The six arched slotted windows on the ground floor on the north side are widened in a funnel shape inwards and outwards. Different materials and the strange placement speak for different times of creation. In the area of the gable there was a round-arched door on the north and south side, with a balcony in front of it. All other openings in the stone house and the staggered gable come from a later period.

In 1511 the stone house was owned by the Werrich family, their coat of arms with a fiddle as a coat of arms can be seen next to that of the city of Wimpfen on a wall painting inside. The large cellar was created around 1600. The building was used to store supplies well into the 20th century. Today it's a museum.

On July 12, 2009 a Staufer stele was inaugurated near the stone house .

Candle arch gate

The Schwibbogentor (also Hohenstaufentor ) with its gate tower was the gateway to the high medieval Palatinate (around 1200), the southern entrance to the Imperial Palatinate. In front of the gate there was a drawbridge over the moat . With a clear width of more than three meters, the gate, which is above average, is vaulted by a flat arch with the original crown height of 3.70 meters. Apart from the profiled fighter plates and the bases , the arch and garment stones are smooth. In the modern conversion of the Burgviertel into a residential area, the street level was lowered to the south and the lining wall of the moat (today's main street ) was broken, so that the floor of the southern gate opening is now about two meters lower than before. On the side pillars you can see the old base stones that mark the original level. The tower has no access at ground level, as this was once done from the battlements (today from the neighboring building).

The first floor of the gate tower protrudes over a profiled cornice supported by consoles , while the second and third floors are set back a few centimeters. To below the ledge here the largely set in layers just under rubble of the curtain wall embedded in the masonry of the tower. Above the ledge, the corner connection of the storey walls consists of blocks. The tower was later raised by the third floor; here the corner stone blocks are made differently, some are embossed .

The windows visible on the south side do not belong to the original inventory. They replace older windows, some of which were also added later. Instead of the arched neo-Romanesque windows on the first and second floors, simple rectangles appear in a picture from 1967, identical to those on the third floor. The original slot windows on the second floor that were recognizable at the time were destroyed. Only one of the walls on the first floor seems to come from the original inventory.

On the north side of the tower you can see the original condition, although all openings are walled up. On the first floor you can see a funnel-shaped widened round arched slot window. Next to it begins an approximately two-meter-wide section of wall protruding from the wall, which extends to the ceiling height of the second floor. It belongs to the original state, because it stands on the same cornice supported by consoles as the first floor. The wall section is the back of a fireplace . Its chimney is made of tuff , as is the interior staircase leading to the second floor. The tuff stone used and an oculus west of the chimney suggest that the gate tower was built during the second phase of the Red Tower's construction. It is likely that there was an older gate system, but the question of its location and appearance can no longer be clarified.

Blue tower

Bad Wimpfen's landmark, the 58-meter-high Blue Tower , was built as the third keep after 1217. It stands on the west side on the highest point of the Palatinate. The originally higher space was removed by about three meters in the middle of the 19th century. The now partially exposed foundation was clad with small shell limestone. The approximately three meter thick masonry of the tower with an outer shell made of large shell limestone blocks therefore only begins about three meters above today's ground level. Sandstone was only used for the walls of the arched entrance on the east side and for the toilet bay on the south side. The pincer holes visible on the larger blocks date this construction phase to the 13th century, because the pincer was only used as a lifting tool from 1210/20 onwards. The design of the bay window with its small oculus is almost identical to that of the bay window on the Red Tower.

In the upper area, the stone format changes to small cuboids. They come from the restoration of the tower in 1851/52 after the devastating fire of 1848. At that time, the tower also received its present-day appearance with a ground-level entrance, the neo-Gothic corner turrets , the pointed arch frieze and the spire . The blue shade of the slate covering probably led to the current name Blue Tower ; previously the tower was only known as the high tower . It soon became apparent that the superstructure was too heavy. In 1870 the walls were stopped from diverging with the help of iron clips. The base of the tower was reinforced, the access to the lavatory walled up and in 1907 the tower was secured with four large iron ring anchors . In 1922 the roof was renovated, and in 1944 three concrete ceilings were installed inside for air protection reasons. In 1971, the outer walls were stabilized by injecting around 300 tons of cement mortar , which presumably flowed into the canals of decomposed wooden anchors from the time of construction and not into the "intermediate shell masonry filled with almost unbonded rubble" (B. Cichy, 1972), because in 1870 it persisted the observation of August von Lorent the "infill masonry made of small stones with a lot of mortar". The iron anchors have been removed. The masonry renovation was followed in 1978 by a roof renovation.

In 1984 another fire caused by lightning struck the tower again completely. The nine hundredweight tower bell fell on a lower floor and the tower helmet collapsed. In 1984/85 the tower was restored; A fire-proof and rubble-proof concrete cup was pulled in to secure the tower house. The new tower bell was a gift from the Bachert bell foundry .

In spring 2014, the tower was again extensively renovated, as the masonry in the lower tower area had an increasing number of offsets. A tensioning frame made of wood and steel was placed around the body of the tower as a kind of corset to clamp the walls together and then stabilize the masonry.

On the tower, which can be visited, lived until November 2017 since the late Middle Ages continuously a watchman . From 1974 until the fire in 1984, the writer couple Heinz and Vera Münchow lived in the tower-keeper's apartment with their three children . Blanca Knodel, who has been doing this job since 1996, is one of the few towers in Germany today. The two other active keepers do their duty on the tower of the St. Lamberti Church in Münster and in the Paul Gerhardt Church in Lübben (Spreewald) . In order to be able to enjoy the beautiful view from the tower, 134 steps have to be climbed up to the tower house, from which a further 33 steps lead to the 32 meter high viewing platform . Due to extensive renovation measures, Ms. Knodel had to move out of the tower-keeper's apartment temporarily in November 2018, probably by 2020.

Palatinate Wall

In the north and south-east of the Palatinate, large parts of the walling have been preserved, while to the west there are practically no visible remains of the Palatinate wall. To the north towards the Neckar, the Palatinate Wall also forms the north wall of the Hohenstaufen buildings (stone house, palas), to the east on the mountain spur at the Red Tower the walling merges into a system of staggered defensive walls, in the south-eastern part between the Red Tower and Hohenstaufentor the wall forms many times the south wall of the attached (younger) buildings.

A memorial plaque for Richard Weitbrecht (1851–1911), writer and pastor in Wimpfen, is embedded in the outside of the Palatinate wall.

literature

- Rudolf Kautzsch : The art monuments in Wimpfen am Neckar . 4th, corrected edition. Alt-Wimpfen, Wimpfen am Neckar 1925

- Fritz Arens : The Königspfalz Wimpfen . German publishing house for art history, Berlin 1967

- Fritz Arens: The Palas of the Wimpfener Königspfalz. New findings on the floor plan . In: Journal of the German Association for Art Science XXIV , 1970, pp. 3–12.

- Bodo Cichy : The structural renovation of the Blue Tower in Bad Wimpfen . In: Preservation of monuments in Baden-Württemberg , 1st year 1972, issue 2, pp. 34–37. ( PDF )

- Günther Haberhauer : Regia Wimpina. Contributions to the history of Wimpfen. Volume 4: Special volume on the reconstruction of the Blue Tower. Association "Alt Wimpfen" e. V., Bad Wimpfen 1985

- Fritz Arens, Reinhold Bührlen : Wimpfen - history and art monuments. Association Alt Wimpfen, Bad Wimpfen 1991

- Günther Binding : German royal palaces. From Charlemagne to Frederick II (765–1250). Scientific book company / Primus-Verlag, Darmstadt 1996, ISBN 3-89678-016-6

- Jürgen Kaiser : Königspfalz Bad Wimpfen . Verlag Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 2000 (Small Art Guide, 2427)

- Ludwig H. Hildebrandt , Nicolai Knauer : Beginning and end of the Kaiserpfalz Wimpfen - additions to the current state of research. In: Kraichgau. Contributions to landscape and local research. Episode 21, 2009.

- Günther Haberhauer, Hans-Heinz Hartmann : New archaeological findings on the building history of the Königspfalz Wimpfen. In: Kraichgau. Contributions to landscape and local research. Episode 21, 2009.

- Thomas Biller : The Palatinate Wimpfen . Schnell und Steiner publishing house, Regensburg 2010 (castles, palaces and fortifications in Central Europe, vol. 24)

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hildebrandt / Knauer p. 193.

- ↑ Haberhauer / Hartmann pp. 17–33.

- ↑ Hildebrandt / Knauer p. 202.

- ^ Stephan Frey: The Nikolauskapelle der Kaiserpfalz Bad Wimpfen. Studies on patronage and dating. An interdisciplinary research approach. Akademische Verlagsgemeinschaft München, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-86306-755-7

- ↑ Hildebrandt / Knauer p. 202

- ↑ Red Tower on the website of the city of Bad Wimpfen

- ↑ Bad Wimpfen 2009 on stauferstelen.net. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ↑ Arens 1967, p. 127, fig. 82 and plate 6.

- ↑ Hildebrandt / Knauer p. 180.

- ↑ Lived tradition: tower keeper on the blue tower of the former imperial palace Bad Wimpfen am Neckar, press release of the city of Bad Wimpfen from February 9, 2015, accessed on August 19, 2015

- ↑ How the Blue Tower in Bad Wimpfen is saved Heilbronn Voice, September 21, 2018

Coordinates: 49 ° 13 '49.4 " N , 9 ° 9' 47.3" E