Luther Bible

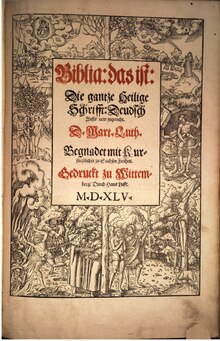

The Luther Bible (abbreviation LB ) is a translation of the Old Testament from the Old Hebrew and Aramaic languages and the New Testament from the Old Greek language into the early New High German language . This translation of the Bible was done by Martin Luther with the help of other theologians. In September 1522 a first edition of the New Testament was ready; from 1534 a German full Bible was available, to which Luther made improvements throughout his life. In 1545 the last corrections to the Biblia Deudsch were made by Luther himself .

One understands the Luther Bible on the one hand

- a book from the 16th century with Luther's translation of the Bible, which was printed in very large editions and of which there are splendid editions with hand-colored or painted woodcuts ,

and on the other hand

- a central book for German-speaking Protestantism , which has developed from Luther's Biblia Deudsch to the present day, whereby Pietism and modern biblical studies brought their concerns in a changing and preserving way.

The Evangelical Church (EKD) recommends the Luther Bible, revised in 2017, for use in church services. The 2017 version of the Luther Bible is also used in the New Apostolic Church . The Luther Bible from 1984 is used by the Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church (SELK).

In the Luther House in Eisenach , a permanent exhibition is dedicated specifically to the Luther Bible.

Characteristics of the Luther translation

This section provides an overview of the most important characteristics of the Luther Translation from its creation to the present day.

- author

- The author of the translation is Martin Luther with the support of other theologians, in particular Philipp Melanchthon .

- Date of origin and revisions

- The translated New Testament appeared in 1522, the entire Bible in 1534. Luther himself made corrections until 1545. In the centuries that followed, the spelling was repeatedly adapted to new orthographic habits, but the wording was only changed if it had become incomprehensible. After 1912, other Urtext variants were also incorporated in some cases, see item “Urtext” below.

- scope

- The Old Testament has been translated to the extent of the canon of the Hebrew Bible , the late writings of the Old Testament approximately to the extent to which they belong to the canon of the Catholic Church, and the New Testament . For the arrangement of the biblical books in the translation, see the section entitled Selection and order of the biblical books .

- Urtext

- The Masoretic text in Hebrew and Aramaic is the basis for the Old Testament ; In the revisions after 1912, corrections based on old translations or modern text conjectures were incorporated in places . The late writings of the Old Testament were translated by Luther and his collaborators from the Greek Septuagint and the Latin Vulgate ; For the 2017 revision, some new translations were made from the Septuagint .

- The text basis of the New Testament is the original Greek text of the New Testament published by Erasmus (later versions were called Textus receptus ) without the Comma Johanneum . The revised versions after 1912 are based on the older Alexandrian text of the New Testament ( Novum Testamentum Graece after Nestle and Aland ).

- Translation type

- It is a philological translation (see the article Biblical Translation ), which at the same time contains clear communicative elements due to the strong orientation towards the idiomatic of the target language German - an innovative and controversial approach at the time. The world of images is often tailored to the German reader.

- linguistic style

- For more on Luther's own linguistic style, see the section on Luther's linguistic creative achievement . After the versions of the 20th century had approximated the modern German language, the 2017 revision had the principle of staying as close as possible to Luther's linguistic style, provided that it is still understandable today.

- Commentary, references, key points

- Most editions of the Luther Bible contain section headings that do not belong to the text and references to section, verse and word parallels. Often there is an appendix with factual and verbal explanations about the biblical environment (e.g. maps, measurements, weights). Luther had "key passages" highlighted in the print with particularly important statements. For later development and the use of the key passages, see the section Biblical Use in Pietism .

The way to Biblia Deudsch from 1545

Translation of the New Testament

Submerged as “Junker Jörg”, Martin Luther began translating the New Testament from Greek at the Wartburg . Philipp Melanchthon had motivated him to do this work, probably in December 1521. After the Greek New Testament had been printed by Erasmus , humanists had tried to translate individual parts into German. Johannes Lang z. B., Luther's fellow brother and former Greek teacher in Erfurt , had a German Gospel of Matthew printed. Luther sought a more communicative translation , and he also wanted to present the New Testament as a whole to the public.

Luther's handset in the Wartburg

Luther had the Vulgate to hand at the Wartburg , or it was so present to him by heart that he no longer needed the book. Nikolaus Gerbel from Strasbourg had given him a copy of his Greek NT (Greek text after Erasmus, but without any additions). In addition, Luther also had the NT of Erasmus (2nd edition 1519) available, which offered the Greek text with annotations in two columns and a new Latin translation next to it. This edition was important for Luther because his Greek was not so good that he could have worked independently with the original text without the help of philologists such as Erasmus or Melanchthon .

Luther translates in different ways, although it cannot be clarified why he opted for one of the following options:

- He follows the Vulgate and translates the Greek text as it does.

- It follows the Vulgate against the Greek text.

- He follows the Vulgate despite the correction of Erasmus.

- It follows the translation of Erasmus against the Vulgate. This is the normal case where it deviates from the Vulgate.

- He follows the remarks in Erasmus against the Vulgate, even where Erasmus did not implement them in his translation.

- It combines various suggestions for your own design.

- He himself translates (incorrectly) from the Greek against Erasmus and against the Vulgate. Independent work on the Greek text was Luther's ideal, but under the working conditions at the Wartburg and without the advice of the experts, he was not yet able to implement it.

- He translates freely, in spirit, inspired by the comments of Erasmus.

According to the translation of the Bible, the Luther room on the Wartburg was the place “where Luther threw the secure crutches out of his hands and made his own, albeit z. T. tried awkward steps. "

The Stuttgart Vulgate, a Bible from the circle of Martin Luther

In 1995 it seemed as if the Latin Bible that Luther was using at the Wartburg had been discovered in the Württemberg State Library . This book, printed in Lyon in 1519, is full of entries from a person who dealt with Luther's translation work, has a handwriting similar to him, but (according to the current status) is not Luther himself.

The meaning of the Latin Bible

It is only part of the truth that during these weeks Luther - true to the humanist motto ad fontes - turned away from the Vulgate and turned to the original Greek text. On the other hand, he took all the examples from the Latin Bible in his letter of interpreting in 1530 . "In doing so, he made mistranslations that can only be explained if one assumes that Luther trusted the Latin text without paying attention to the Greek." This is why the influence of the Vulgate in the Luther Bible is very noticeable, which is such a legacy of the medieval Latin tradition preserved in the German-speaking area to this day.

Examples of the adoption of the Vulgate tradition against the original text

In both cases, only the revision of 2017 corrected Luther's translation, in each case with the note: "Luther translated from the Latin text."

Philippians 4,7 … καὶ ἡ εἰρήνη τοῦ θεοῦ ἡ ὑπερέχουσα πάντα νοῦν φρουρήσει τὰς καρδίας ὑμῶν καὶ τὰὰ νοήμτα μἸηα νοήμτα ὑμἸητα ντστα ὑμῶηντστα ὑμῶηντστα ὑμῶηντστστα. Vulgate: Et pax Dei, quæ exuperat omnem sensum, custodiat corda vestra, et intelligentias vestras in Christo Jesu .

LB 1545 Vnd the peace of God / which is higher / because everyone senses / warrants ewre hearts and senses in Christ Jhesu .

LB 2017 And the peace of God, which is higher than all reason, will keep your hearts and minds in Christ Jesus .

Meaning: pulpit blessing in Protestant worship.

Romans 9.5 … καὶ ἐξ ὧν ὁ Χριστὸς τὸ κατὰ σάρκα, ὁ ὢν ἐπὶ πάντων θεὸς εὐλογητὸς εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας

Vulgate:… ex quibus est Christ secundum carnem, qui est super omnia Deus benedictus in sæcula .

LB 1545 ... from which Christ compt according to the flesh / He is God above all / praised in eternity .

LB 2017 ... from which Christ comes after the flesh. God, who is above all , be praised forever .

Meaning: Important for Christology .

Examples of the reproduction of Vulgate formulations in the Luther Bible

Romans 6,4 Consepulti enim sumus cum illo per baptismum in mortem: ut quomodo Christ surrexit a mortuis per gloriam Patris, ita et nos in novitate vitæ ambulemus.

LB 2017 So we are buried with him through baptism into death, so that just as Christ was raised from the dead through the glory of the Father, so we too may walk in a new life .

EÜ 2016 We were buried with him through baptism into death, so that we too may walk in the reality of new life, just as Christ was raised from the dead through the glory of the Father .

Romans 12:18 Si fieri potest, quod ex vobis est , cum omnibus hominibus pacem habentes.

LB 2017 Is it possible, as much as it is up to you , have peace with all people .

EÜ 2016 As far as you can , keep peace with everyone!

Galatians 2:20 a Vivo autem, jam non ego : vivit vero in me Christ.

LB 2017 I live, but now not me , but Christ lives in me .

EÜ 2016 No longer I live , but Christ lives in me .

The September Testament 1522

On a splendid manuscript of the September Testament : see Glockendon Bible .

Luther translated very quickly. “When he returned to Wittenberg at the beginning of March 1522 , he had the finished manuscript in his luggage.” He went through this draft again with Melanchthon as a specialist in the Greek language in the following weeks. Georg Spalatin , also a connoisseur of Greek, was often asked for help with word clarifications. The numismatist Wilhelm Reiffenstein advised Melanchthon by letter on questions relating to ancient coins. (As a result of this learned exchange, Luther was able to update all coins of the New Testament with coins of his own time: Groschen , Heller , Scherflein , Silberling , Silbergroschen . These historical German coin designations are used in the Luther Bible to this day, especially since a few winged words are associated with them .)

In order to prevent reprints from the competition, the printing was prepared in secret. Lucas Cranach and Christian Döring bore the publishing risk . Luther's name did not appear on the title page. This New Testament was a high-quality folio volume and therefore relatively expensive, single-column, in Schwabacher type, with conventional picture decorations. A cycle of 11 full-page woodcuts from the Cranach workshop adorned the apocalypse. Albrecht Dürer's apocalypse cycle provided the template. Luther and Cranach designed the execution together; they were concerned with current polemical points against the papacy.

The Wittenberg Melchior Lotter was won as a printer for the company. The printing technology meant that none of the surviving copies were alike: In Lotter's workshop, three presses were in operation at the same time; The deadline pressure meant that existing sentences were broken up in order to be able to use the letters for new pages of text. (This phenomenon accompanies the Luther Bible up into the 18th century: the number of text variants increased with each reprint.)

In September 1522, “just in time for the Leipzig Book Fair ”, the New Testament was available in a high circulation of 3,000 copies. The book cost between ½ and 1½ gulden, depending on the configuration, and was sold out within three months. As early as December 1522, the second edition was printed with improved text and corrected images (December will).

Translation of the Old Testament

Luther's Hebrew handset

Luther had been learning Hebrew since around 1507, essentially as a self-taught person . This subject was still new at the universities, measured against it, Luther's language skills were good, but not sufficient to read Hebrew books without help. He used the textbooks and grammars of Johannes Reuchlin and Wolfgang Capitos , and he also knew the grammar of Moses Kimchi . In his personal possession were two Urtext editions: a small Soncino Bible (see below) and a (lost) large Hebrew Bible, as well as a Hebrew Psalter that Johannes Lang had given him.

Traces of work on the Hebrew text

Before 1519 Luther acquired a copy of the Tanach , which contained entries from two previous Jewish owners. He especially read the books of the Torah , especially the book of Moses . Most of Luther's handwritten entries are in Latin, a few in German; they deal with translation problems. However, it is difficult to see “a direct reflection of the translation work” in Luther's notes: He probably always had the handy volume with him, but his entries in it seem spontaneous and random.

But there are also examples where the trace of his translation can be traced from the notes in his Tanach edition to the print editions and even to the LB of 2017:

Isaiah 7,9b אם לא תאמינו כי לא תאמנו׃

Luther's note (p. 305v below): If you don't believe, you won't stay. Allusio believes - stays .

So he imitated a play on words from the Hebrew text (taaminu / teamenu) in German. He had rejected this translation idea before the full Bible of 1534 was printed. He opted for a free, interpretive translation.

LB 1534 Don't believe jr so you will file . Marginal gloss on this: This is what else furnemet that should file / and not exist nor have any luck .

The internal rhyming translation has returned to the last hand of the Luther Bible , and it continues to this day.

LB 2017 If you don't believe, you won't stay .

A Jewish book with a Christian translation

"Whoever wants to speak German / he does not have to use the Ebreian word way / but has to see it / ... that he can make sense / and think: Dear / how does the German man speak in such a case? If he now has the German word / which serves for this purpose / so he let go of the Ebreischen word / and speak freely the meaning out / in the best German / so he can. "

Luther lived far from the last centers of Jewish learning in the empire and, unlike other humanists, he never tried to get to know Jewish experts personally. The appreciation of the Hebrew language went hand in hand with a fundamental distrust of the rabbis because they did not recognize the Christian dimension of the Old Testament.

The reformer explained his translation decisions in the “Summaries of the Psalms and Causes of Interpreting” (1533): All in all, he wanted a fluent translation “in the best German”, but where the Hebrew wording seemed to offer a deeper meaning, he translated literally . This is more problematic than it might seem. Because Luther's Christian faith was his "divining rod" ( Franz Rosenzweig ), which determined where the Old Testament was the living word of God, "there, and only there, but there, it had to be taken literally and therefore also translated into rigid literality" . In this way, Luther's Christian interpretation permeates the entire Old Testament.

The work of the Wittenberg translation team

The Old Testament of the Luther Bible was a collective work. Luther began translating the Pentateuch with a team of experts as late as 1522 . The contribution of the Wittenberg Hebraist Matthäus Aurogallus was important . Johannes Mathesius claimed that Luther "had a number of scoops cut off" and then asked the Wittenberg butcher about the names of the individual innards - in order to be able to translate passages such as Lev 3, 6-11 LUT correctly. Initially in quick succession, one book of the Old Testament was translated and put into print: as early as October 1524, the Pentateuch, the historical and the poetic books (i.e. the entire first volume of the two-volume full Bible editions) were available.

The translation of the books of the prophets

Because of linguistic difficulties, translation work stalled when the books of the prophets were turned to; meanwhile, a translation of all books of the prophets by the Anabaptists Ludwig Hätzer and Hans Denck was published in Worms in 1527 . Luther paid ambivalent praise to this book:

“That is why I believe that no false Christian or Rottengeist can trewlich dolmetz, as it seems in the prophetenn zu Wormbs, but there was much more happened and my German almost followed. But there have been Jews there who have not shown Christ a great deal, otherwise there would be enough art and hard work. "

Luther's group of translators used the “ Worms Prophets ” as an aid, but then pushed them off the book market with their own prophet translation . An example to compare both translations:

Micha 6, 8 הגיד לך אדם מה-טוב ומה-יהוה דורש ממך כי אם-עשות משפט ואהבת חסד והצנע לכת עם-אלהיך:

Haters / Denck man it is sufficiently announced to you / what is good / and what the LORD requires of you / namely / to be right / to love mercifully / and to walk chaste before your God .

LB 1534 You have been told / man / what is good / and what the LORD feeds from you / namely / to keep God's word / and love and / and be humble for your God .

(Meaning: Mi 6.8 is a problem with every Luther Bible revision, because here Luther's translation is strongly influenced by his theology and does not do justice to Hebrew. Because the text is very well known, for example through a Bach cantata Also received the revision of 2017 Luther's formulation and added the literal translation in a footnote.)

The first complete edition in 1534

While working on the books of the prophets, the translation of the Apocrypha began. As the first apocryphal script, Luther translated the wisdom of Solomon from June 1529 to June 1530 . Luther was often sick, which is probably why his collaborators took over the translation of the Apocrypha.

The New Testament , thoroughly revised in 1529, received its final form in 1530.

In 1531 the Psalter was revised again by a team that included Luther, Philipp Melanchthon , Caspar Cruciger , Matthäus Aurogallus and Justus Jonas , possibly also the Hebraist Johann Forster . Due to his historical and philological knowledge, Melanchthon was “to a certain extent the walking lexicon of revision”. The protocol received from Georg Rörer's hand shows how the commission worked: All formulations were put to the test, and the philologists occasionally suggested changes that Luther decided on. On this occasion, Psalm 23 was given the "classical" wording.

Psalm 23,2a בנאות דשא ירביצני

Luther's handwriting: He reads me weyden ynn the win of the grass .

First printing of the Psalms 1524: He reads me because there is a lot of grass .

Revised text 1531: He feeds me on a green aven .

For the complete edition , the Wittenberg translation team looked through the entire text of the Old Testament one more time in 1533, especially the Book of Moses . At the Michaelismesse in Leipzig (October 4 to 11, 1534) the complete Bible (900 unbound folio sheets ) was available for purchase, six parts, each with its own title page and its own page number: 1. Pentateuch , 2. historical books, 3. poetic books , 4. Books of the Prophets, 5. Apocrypha , 6. New Testament. It was the first Luther Bible with the coat of arms and the printing permission of the elector .

The additions to the Biblia Deudsch

In order for the reader to find their way around the Bible as easily as possible, Luther and his team of translators had put a lot of work into the prefaces and marginal glosses.

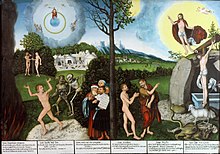

The prefaces guide the reader to read the Bible with Luther's questions ( doctrine of justification ):

- Preamble to the Old Testament: “So the Old Testament is actually to read the laws and to indicate sin / and to grind well.” By pointing out sin (e.g. through the Ten Commandments ), man recognizes his failure. According to Luther, the books of the OT contain examples of how the Israelites fail at the law.

- Preamble to the New Testament: The New Testament is all gospel , “good news / good multiples.” Christ entices, he does not threaten. " So now look at it / That you don't make a Moses out of Christ / nor a law or a textbook out of the Euangelio ... Because the Euangelium doesn't actually feed our work / that we are from there and become happy ... It encourages belief in Christ ... That We must accept his death and victory / as if we had done it ourselves. "

The explanations on the AT required specialist knowledge in various disciplines. In the “Preface by the Prophet Daniel ” z. B. The history of the Maccabees is presented to the reader in detail, since the historical seat in life is correctly recognized. (But then the reformer is overwhelmed by contemporary history: "The Bapst is clerically painted / who roars in shame in his filth ...") As an example of the many small factual explanations that the Biblia Deudsch offered the reader, here is a marginal gloss on Hi 9,9 LUT : “( Orion ) Is the bright stars around noon / that the peasants are called the Jacob's staff . The mother hen or hen / are the seven little stars. "

With all this, however, there is no true picture of the ancient Orient or the ancient world in front of the reader's eyes, but it is always Luther's own environment, which was populated by servants and maidservants, not slaves, in which familiar plants grew and pigs like In Wittenberg it was customary to eat brewing residues instead of pods from the carob tree : “And went there and went to a citizen of the same country / who was sent to watch his field of sew. And he was eager to fill his belly with tears / who ate the sewing / and no one gave them to somebody. ”( Lk 15 : 15-16 LUT )

Selection and order of the biblical books

Luther based the order of the books of the Old Testament on the Septuagint because for him this was the Christian arrangement of the Bible. What is new is that he detached those books and sections of the Septuagint that do not belong to the Jewish canon from their context and placed them as Apocrypha in an appendix to the Old Testament. But he recommended reading it. Luther's distinguishing criterion was the hebraica veritas: an authentic holy scripture of the Old Testament must therefore be written in Hebrew. This idea “can already be found in part with Hieronymus in antiquity and was also present in the Occidental Middle Ages due to the contacts with rabbis. But with the humanistic text work, the orientation to the Hebrew text acquired a new meaning. "

For the New Testament there is a consensus about which scriptures belong to the Bible. Luther by him less esteemed books (does Hebrews , Jakobus- and Jude and Revelation ) moved to the end, she has but translated and left no doubt that they of the New Testament are full valid components.

The spelling of God's name

In the Old Testament of the Luther Bible of 1545, the spelling HERR stands for YHWH , the spelling "LORD" for Adonai . In the New Testament, the spelling HERR is in 150 quotations from the OT that contain the divine name YHWH. Where in Luther's view Christ is meant, he chose the spelling LORD. However, printers handled these rules differently. (During the 2017 revision, consideration was given to reintroducing Luther's spellings. This did not happen because it would have required considerable exegetical, reformation-historical and systematic preparatory work. In modern editions of the Luther Bible, the spelling Herr is used for YHWH .)

"Eli, eli, lama asabthani?"

In the Gospels of Matthew and Mark, the last words of Jesus on the cross are given in Aramaic, transcribed in Greek. It is a quote from Psalm 22,2 LUT : אלי אלי למה עזבתני. Luther corrected both places by adding his pronunciation of the Hebrew text: “Eli, Eli, lama asabthani?” Behind this is his special veneration for the Hebrew language: “The New Testament, whether it is written in Greek, but it is full of Ebraismis and Hebrew way of speaking. That is why they said rightly: The Hebrews drink from the spring of the Born; but the Greeks from the Waterslin, which flow from the spring; but the Latin ones out of the puddles. ”( WA TR 1,525 ) The Luther Bible from 2017 follows Luther's spelling with explanatory footnotes.

Luther's Bibles in UNESCO's World Document Heritage

In 2015 UNESCO included several early writings of the Reformation in the UNESCO World Document Heritage ; including books directly related to the Bible project. They are available as digital editions (see web links):

- Personal copy of Luther's Hebrew Bible Edition , Brescia 1494, Berlin State Library - Prussian Cultural Heritage , Shelfmark: Inc. 2840.

- The Newe Testament Deutzsch, Wittenberg, Melchior Lotter , 1522, Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel , Shelfmark: Bibel-S. 4 ° 257.

- Biblia is the whole of the Holy Scriptures in German. Mart. Luth., Wittenberg, Hans Lufft , 1534, Duchess Anna Amalia Library - Classic Foundation Weimar , Shelfmark: Cl I: 58 (b and c). See Weimar Luther Bible from 1534 .

Luther's creative language performance

For Luther's own account of his translation decisions: see Letter from Interpreting .

Understandable language and biblical style

Luther's well-known statement that he wanted to “open your mouth” does not mean that his translation seemed linguistically undemanding or vulgar to contemporaries. As Birgit Stolt has shown in several works, the text signaled to the reader at the time that he was dealing with a special, holy book. For this purpose, sacred language formulas (“it came to pass”, “see”), rhythmic subdivisions and rhetorical decorative elements such as alliteration , internal rhyme and the play with vowels were used. In the course of time Luther discovered more and more language-painting formulations; the price for this is sometimes a greater distance from the basic text. That the aesthetic quality contributed to the success of his translation was also noticed by opponents like Georg Witzel : "He deudtschts after the sound." Examples:

- Psalm 46 : 4 "If the sea rage and wallet ..."

- Matthew 5:16 "So let everybody light shine for men ..."

- Luke 2,12 "You will find the child wrapped in diapers / and in a crib."

Luther used modal particles as a special means of expression in German in order to make the translated text look like living, spoken German.

The Bible was a read-aloud book, which was served by the sentence structure . It is more of a listener than a reader syntax: “Small statement units in step-by-step sequence, additively to ensure understanding.” Even inexperienced readers benefit from this. Example ( Mt 7,9-11 LUT ):

"Which one of you men / if your son asks for bread / who offers you a stone? or so he asks jn a fish / who offers jm a snake? So then jr / who jr are bad / still give your children good gifts / how much more will your Father in heaven give good things / to those who ask jn? "

This sentence structure, although archaic, is easier to understand than the following:

“Which of you men who offers his son a stone when he asks for bread? Or who, if that person asks him for a fish, offers him a snake? If you, who are bad, can still give your children good gifts, how much more will your Father in heaven give good gifts to those who ask him? "

Luther's Bible prose was a very attractive resource for Bertolt Brecht because it was easy to understand and close to the spoken language .

Pioneer of New High German?

Luther's achievement did not consist in having a decisive influence on the language system, i.e. on the grammar and the rules, since early New High German had these rules long before it did. However, he acted as a linguistic model in various types of text: edification literature, sermon texts, agitation texts, theological specialist prose, church hymns, translated texts. The very high number of copies of the Biblia Deudsch , which was extremely high at the time , provided a strong impetus for standardizing the written German language. As a result of Luther's translation of the Bible, the final “e” spread in many words in the written language of the church; see. Lutheran e .

Luther's spoken language was East Central German from the parental home ; he was familiar with Low German from his stays in Eisleben and Mansfeld . When Luther arrived in Wittenberg , Luther found a diglossia : Low German (Elbe-East German) in the simple population, East Central German around the electoral administration and the university. According to his own admission, Luther's writing language was based on the Saxon chancellery , which has absorbed southern German influences. His Bible helped the New High German to assert itself in northern Germany - which was not a concern of Luther, on the contrary. Luther's colleague Johannes Bugenhagen translated the entire Bible into Middle Low German .

Vocabulary enrichment

As a translator, Luther took part in a development of early New High German , in which everyday language words that were previously only used regionally rose to national recognition: goat (instead of goat), bank (instead of shore), vineyard (instead of Wingert). His selection criteria were theological in nature, that is, semantically, communicatively and pragmatically motivated by religion. This is shown by Oskar Reichmann's investigations into the material from the Early New High German Dictionary and the Göttingen Bible Archive.

Luther's Bible enriched the New High German vocabulary with winged words . When asked about the role of such expressions, however, the following should be noted: These examples only represent individual cases within an expression set of around 100,000 units. Many of them are also documented before Luther (cf. FWB-Online.de).

From the Biblia Deudsch to the "Luther Bible 2017"

Luther Bibles up to the 19th century

The Electoral Saxon Standard Bible

For the Weimar Luther Bible, Duke Ernst the Pious (1641): see Elector's Bible .

Since Luther constantly revised the Bible, different versions of the text were in circulation from the start. After Luther's death, the Lutheran rulers agreed to establish a canonical Bible text based on the last version authorized by Luther from 1545 (and not Georg Rörer's notes from 1546). The complicated comparison of several Bible prints resulted in the Electoral Saxon Standard Bible in 1581 ; Kurbrandenburg , the Duchy of Württemberg and Braunschweig joined them. In 1581 a printer from Frankfurt expanded the text of 1 Joh 5: 7–8 to include the Comma Johanneum ; a change that was incorporated into all Luther Bibles in the decades that followed, as it was welcome scriptural evidence of the Trinity .

Bible Use in the Denominational Age

For collecting autographs in Bibles: see Dresden Reformers' Bible .

In the time of Lutheran Orthodoxy , the Bible was read with the questions of dogmatics . Owing to frequent reprint, a relatively large number of people have now been able to afford their own Bible. You read the Bible backwards; the Brunswick bailiff Johann Cammann z. B. 28 times. The record in this regard was held by the lawyer Benedikt Carpzov (53 times). A Wittenberg resident who could recite the entire text by heart received a master's degree without studying.

Baroque musicians made texts from the Luther Bible the basis of their compositions. An example of this are the Psalms of David (1619) by Heinrich Schütz . He interpreted Luther's Bible prose using the means of the Italian madrigal .

One of the few objects that have been preserved from the personal possession of Johann Sebastian Bach is his Calov Bible (Luther Bible with the commentaries of Abraham Calov ). Like Bach, other Bible readers also made entries in their copy. Some recall "dates of birth, marriage and death, but also special events such as illness, war or catastrophes." By carrying the Bibles around in everyday life, they could become a kind of evangelical relics. Well-known is the Nürtingen Blood Bible , property of a pastor murdered by Spanish soldiers in 1634. The book reached the library of Duke Karl Eugen in 1787 with blood stains and sword marks .

The Bible prints of the Canstein Bible Institute

The Canstein Bible Institute in Halle felt compelled to save the text and to clean it up before it began to distribute Bibles in large quantities at very reasonable prices from 1714 onwards through printing in the standing composition process . Original prints from Wittenberg, which had appeared during Luther's lifetime, were obtained and a mixed text was collated from them, a “patchwork of words and terms from different levels of tradition from Luther”, but which had the advantage of having removed many of the corrupted texts carried on by the printers, almost 100 % To contain Luther's wording and also to translate as faithfully as possible. Because the Pietists read the Hebrew and Greek texts and discovered with some nervousness that Luther had taken liberties in translating. August Hermann Francke wanted an open discussion about this:

"... as high as I think the Lutheri version ... / nevertheless it does not agree with the basic text in many places / and could even be improved a lot."

The Bibles from the Canstein Bible Institute were considered the best in the 18th century.

Biblical use in Pietism

On the brethren: see Moravian slogans .

Pietism was fundamentally a Bible reading movement; Instead of the usual pericopes in Lutheran worship and teaching, biblical scriptures should be read in full (tota scriptura) . Instructions on how to properly prepare to read the Bible were the most important guidance that Pietist writers offered to their reading community. Luther's prefaces therefore disappeared from the Bibles of the Canstein Biblical Institute and were replaced by Francke's “Brief Lessons on How to Read the Holy Scriptures for His True Edification”.

Luther had already highlighted numerous verses, the core passages , in print for the purpose of guiding readers : a unique selling point among the German Bibles. This special feature of the Luther Bible was adopted in Halle, but other passages were now marked and for a different reason: timeless words that should speak directly to the reader.

The Stuttgart court preacher Johann Reinhard Hedinger published a controversial Luther Bible edition in 1704. Many years later, the verses he marked as core passages in the Bible text had a great effect, as they were largely taken over into the Luther Bible of 1912. In the sense of Württemberg pietism, core passages are Bible verses "which shine particularly brightly and powerfully into God's counsel of salvation and into heart and conscience". The context in which these sentences are used does not matter. For the Luther Bible 2017, the core inventory has been revised and reduced; the Pietistic tradition of extracting verses from the context and offering them to immediate reception was retained.

The Bible oracle was widespread in various pietistic groups, and numerous personal testimonies report how people sought personal revelation on life issues in the Bible:

- Thumbling: slide your thumb over the book block (a method often used by Philipp Jacob Spener ),

- Needles (biblical pricking): pierce the side of the book block,

only to then unintentionally open and read the Bible at the designated place.

The Bible as a house book

In the country, the Luther Bible was treated like a piece of furniture as part of the yard inventory. Alongside the hymn book, it was the most important reading material well into the 19th century. However, there was little free time available for reading. "Reading meant [...] intensive, repeated review [...] of texts that one had been familiar with since school, that had long been memorized acoustically and visually, [...] was recognition in the psychologically stabilizing comprehension."

The Bible as a school book

The textbook in Lutheran territories was traditionally not the Bible, but the Small Catechism , plus a quota of Bible verses to memorize. In 1763, Prussia tried to raise the level of teaching in the General School Regulations, also through binding textbooks, including: "The New Testament, called the prayer exercise [d. H. an NT with intervening prayers], ... comes next the Hallish [d. H. Cansteinsche] or Berlinische Bibel "(§ 20). It was important "that every child should have their own book"; if the parents were poor, the books were provided by the school but could not be taken home (§ 21). The “finished reading children” were supposed to take turns reading aloud from the Bible in a school lesson (§ 19), while the younger pupils practiced spelling in a primer. However, school attendance was sporadic in many places and the illiteracy rate was therefore high.

Luther Bibles from the 19th century to the revision of 1912

At that time, 14 different versions of the Luther Bible were in circulation because they were printed by different Bible societies. The Frankfurt Bible Society z. In 1819 B. published a version drawn up by Johann Friedrich von Meyer , corrected based on the original texts of the time. The Hamburg chief pastor Carl Mönckeberg (1807–1886) advocated a uniform and linguistically modernized text version in 1855 due to the high number of editions.

School Bibles

The number of Bible verses to be learned by heart varied in the 19th century: 150 in Saxony, 180 in Prussia, and 689 in Württemberg.

Under the influence of the revival movement , there were efforts from around 1830 to use the Bible thematically in class, despite its unsuitable language and sometimes unsuitable content. Since parts of a holy book were not allowed to appear unimportant, Prussia forbade the use of selected Bibles several times and thus remained true to its neo-orthodox-pietistic understanding of the Bible. The Bremen Bible Society developed a Luther Bible, omitting "offensive" passages (i.e. the book was desexualized and dejudaized). After initial concerns, the Bremen School Bible was introduced in Bremen in 1895, in Hamburg in 1897, and in Lübeck in 1900. Württemberg followed suit in 1901 with a biblical reader .

Traubibeln

Around 1870, earlier in Württemberg, the idea of the church congregation giving each bride and groom a special Bible that contained the form for a family chronicle spread among pastors. (This makes these books a genealogical source .) "The cheapest editions of these 'Traubibles' in good leather cord with a gold-plated cross and chalice cost 20 Sgr in a middle octave ."

Altar bibles

In the 19th century, Bible readings were read from the altar in church services, as solemn chant, later mostly spoken. The fact that the open Bible had its permanent place in the middle of the altar was classified by Wilhelm Löhe around 1860 as a popular but impractical innovation for reading. Empress Auguste Viktoria gave newly founded congregations a valuable copy signed by her for the consecration of the church. In many places, these so-called Auguste Viktoria Bibles are still on the altar today, although they are rarely read.

The old Luther text from Thomas Mann

Thomas Mann was socialized in denominational Lutheranism, which he referred to again and again. In the four-volume novel Joseph und seine Brüder (1926–1943) he used Luther's biblical prose "cautiously but unmistakably". In addition, Bible verses are quoted verbatim in prominent places; the Luther Bible "acts as the authoritative subtext for self-explanations of the text"; this of course from a humorous narrative point of view. Mann did not use the revised text from 1912 as the source, but an older version of the text and a reprint of the Biblia Deudsch ; He related this archaic sound of the Luther Bible to the Germanization of scripture (Buber / Rosenzweig) as well as to modern biblical studies and Egyptology.

The Luther Bible among Anabaptist communities in North America

The Amish community is bilingual : Pennsylvania Dutch is spoken alongside English . As holy scripture, however, the Amish traditionally read the Luther Bible in a text form from the 19th century in private and in worship. The Bibles reprinted by the Amish themselves contain the Apocrypha; a prayer from the apocryphal book of Tobias ( Tobit 8,1–8 LUT ) is said at Amish weddings. Luther German has the status of a holy language here; it is read but not actively used. Many Amish schools offer German language courses with a special focus on the grammar and vocabulary of Luther. The same goes for Old Order Mennonites .

In addition to the Froschauer Bible , the Hutterites also use the Luther Bible.

The first profound revisions of the Luther Bible

In contrast to the developing German language, the text version and grammar of the Luther Bible had hardly changed since the 16th century. And since the problem of the divergent editions of the various Bible societies had worsened and printing errors were not uncommon, it was decided to revise the Luther Bible. In the middle of the 19th century, the Bible Societies agreed to create a binding text version of the Luther Bible. In 1858 they proposed

- To keep Luther's sentence structure,

- to carefully modernize its spelling,

- explain obsolete words in a glossary and

- to put the correct translation under Luther's text in pearl script for those passages which Luther had clearly translated incorrectly .

The Eisenach conference of church leaders decided in 1863 to support this Bible revision financially, but to leave the implementation to the Bible Societies, ie not to influence the content.

Luther Bible from 1883

In 1867 the test print of the revised New Testament was published and after almost unanimous approval by the Eisenach Conference in 1868, further revisions to the text were approved. In 1870 the revision of the New Testament was completed. In 1883 the complete “Trial Bible” was published in Halle on Luther's 400th birthday. De facto, it was the result of a cooperation between Halle and Stuttgart: the revised Bible editions of the Canstein Bible Institute with the many core sections of the Württemberg Bible Society. The reactions to the Luther Bible of 1883 were generally positive. But it was not supposed to be the end product of the revision work, and linguistically it was closer to the outdated Luther wording than to the current German at the time. In addition, the revision was cautious and only a few passages of the text had been revised after the critical editions of the New Greek Testament. The reason for this was probably the fact that it was the first official text-critical version of the Luther Bible.

Luther Bible from 1892

The final text was completed in 1890 and the final revisions were completed in 1892. Work was also carried out on the Apocrypha. The result was the first "church official" revision of the Luther Bible, linguistically and also critically revised. The original text of the text version still largely corresponded to the traditional Textus receptus , but was revised much more profoundly compared to older revision work. The edition of 1892 was the first uniform revision of the Luther Bible and the product of half a century of revision work and experience on the Luther Bible.

Luther Bible from 1912

The Luther Bible of 1892 offered a modernized version of the text, but twenty years later it was still considered necessary that another revised version should be published. On behalf of the Evangelical Church Conference, the “second church official revision” of the Luther Bible followed in 1912, which was limited to a mainly linguistic modernization. New findings in biblical studies and biblical basic text research were hardly taken into account. The newly revised New Testament was published in December 1912 and the complete edition in 1913. The apocrypha were also edited. Due to the following political developments in Germany, there were no further revisions of the Luther Bible until the post-war period. Although requests for a clearer modernization were voiced, corresponding plans in the war and interwar period were not implemented.

Failed revision attempts (1921–1938) and the trial version of the New Testament from 1938

From 1921 there were new plans for a contemporary renewal of the Lutheran language , as the previous numerous revisions had led in part to linguistic deviations from the actual Biblia Deudsch of 1545. The aim was to get close to Luther's work without deviating from contemporary usage. Work on the text from the Luther Bible of 1545 began in 1928. The original text selected from the New Testament was new for the Luther Bible. For the first time they resorted exclusively to a text-critical edition of the Greek NT, namely Nestle's 13th edition of the NT Graece from 1927. The political situation in the Third Reich , however, caused a major delays in the administration of the Protestant church leadership, which is why only on Reformation Day 1937, a new Testament with psalter could be presented. However, it did not come to a planned publication in 1938 and the project was canceled. In addition, the revised manuscripts and drafts were destroyed in the bombing war.

Attempts by the National Socialists to replace the Luther Bible with a de-Judaized Bible (1939–45)

On May 6, 1939, the National Socialist group " German Christians " founded the Institute for Research into and Elimination of Jewish Influence on German Church Life ( "De-Judaization Institute" ) on the Wartburg in Eisenach engaged in evangelical theological training. The biblical goal was a revised and de-Judaized version of the Old Testament and some books and passages of the New Testament. Individual passages in the text should be checked for their “Jewish” backgrounds and teachings, modified or taken entirely. The director of the institute was Walter Grundmann , a theologian who was appointed official "Professor for New Testament and Völkische Theology" in 1938 with Hitler's approval. In his opening speech on May 6, 1939, he described the aim of the institute as follows:

- "Just as Martin Luther had to overcome internationalist Catholicism, so Protestantism must overcome Judaism today in order to understand Jesus' true message."

With his historical-critical method he was convinced that the Lukan version of the Sermon on the Mount corresponded to Jesus' true teaching and that the evangelist Matthew had falsified the teachings of Jesus with "Jewish thought". Grundmann was of the opinion that Jesus Christ wanted to fight Judaism. During the revision, a doctrine should therefore be worked out theologically in which Jesus was an “Aryan Galilean” who fought against “the Jews”. In addition, according to Grundmann's theology, the Gospel of John was “contaminated” by Gnostic teachings and some Pauline letters by Catholic teachings. The apostle Paul also falsified the "true" teaching of the Aryan Jesus . These are occasions to “cleanse” the Bible and to offer the regional churches influenced by National Socialism an adapted “translation” that should contribute to a change in the “species-appropriate” faith of German Christians. But with the beginning of the Second World War in September 1939 the idea of such a development came to a standstill. In 1945 the institute was finally closed; no de-Judaized Bibles were published in the “Third Reich” and the Luther Bible was not replaced.

The Luther Bible remained unchanged in its 1912 form until 1956.

Standard Bibles without Apocrypha after 1945

A lack of paper was the reason why the Apocrypha disappeared from the Luther Bible after 1945 . On the one hand, the printing Bible societies were dependent on donations of paper from America, "with the condition that only Bibles without annotations and without Apocrypha could be printed." This was in accordance with the principles of the British and Foreign Bible Society . On the other hand, by saving pages, more copies can of course be printed.

The Luther Bible from 1912 in the 21st century

The Luther Bible in an older text form, including the revision of 1912, is no longer protected by copyright and can therefore be reprinted in the original text or with a modified text form or redistributed in another form without permission being required. The text of these editions will continue to be reprinted, e.g. B. in illustrated editions. Various internet portals offer the text for download, and there are also apps for smartphones . Officially, the LB 1912 was still in use in the New Apostolic Church in 2000. Many Russian-German Protestants still use this edition. The publisher La Buona Novella Inc. Bible Publishing House published revised editions in 1998 and 2009, 2016 and 2017, which have the Textus receptus as the textual basis.

Luther Bible from 1956 (NT) and 1964 (AT)

In the revisions after 1912, Luther's clear mistranslations came into focus, which were attributable to his lack of knowledge of the ancient and ancient oriental world. Example:

Psalm 104, 18 הרים הגבהים ל יעלים סלעים מחסה ל שפנים ׃ LB 1545 The high mountains are the refuge of the chamois / Vnd the stone crevices of the rabbits .

LB 1964 The high mountains give refuge to the ibex and the fissures to the rock badger .

The Novum Testamentum Graece as a scholarly text edition is the basis of the important modern Bible translations worldwide and is also the basis for all revision levels of the Luther Bible after 1912.

In 1956 the revision of the New Testament was completed, the Old Testament remained identical to the edition from 1912/13. In 1964 the revision of the Old Testament followed. In 1970 the revision of the Apocrypha (linguistic, not content) was completed.

Luther Bible from 1975

In the 1975 revision , the principle was that formulations that were not understandable to the average Bible reader should be changed. So the winged phrase “ do not put your light under a bushel ” (Matthew 5:15) was deleted, because the bushel as a measure of grain is unknown today. Instead, it was now called "Eimer", which brought the name "Eimertestament" to the first edition of the 1975 translation. “The fate of this attempt was sealed in public.” However, this criticism of an unfortunate individual translation does not match the peculiarity of the 1975 Bible.

According to the thesis of Fritz Tschirch , who shaped the revision work as a Germanist, the special sentence structure of the Luther Bible had already been modernized by Luther himself and was therefore not inviolable; the sentence constructions should be consistently adapted to the upscale, lively contemporary language during the revision. The implementation of this program affected the text more deeply than any previous revision, especially since well-known Bible texts were also modernized in this way. The result was the "most communicative Luther Bible since 1545". But it was not convincing either as a classic of German literature or as a Bible in modern German. As early as 1977, the EKD Council decided to withdraw around 120 radical changes to the text.

Luther Bible from 1984

The staff of the 1984 revision discovered Luther's rhetorically effective sentence structure as a special translation achievement. The 1975 revision had converted many of Luther's longer sentences into two or three shorter sentences, but it did not make the content easier to understand. The inconsistency of the 1984 revision was also its strength: the wording of known texts was not touched, but in many other places the Luther text was rigorously adopted.

The Luther Bible from 1984 comes from a time when many Protestant congregations celebrated services in a new form. At that time there was a desire not to use the mixed text of the liturgical books in the words of institution , but to be able to celebrate the Lord's Supper directly with the open Bible. But so that the text sounded familiar, 1 Cor 11:24 was given a wording that could only be based on the old Coptic translation:

1 Corinthians 11:24 b

Text according to NT Graece (NA28) τοῦτό μού ἐστιν τὸ σῶμα τὸ ὑπὲρ ὑμῶν ·

LB 1545 to 1956 (based on the Textus Receptus ): This is my body / which is broken for you .

LB 1984: This is my body that is given for you .

LB 2017 (based on the NT Graece ): This is my body for you .

The revised New Testament was accepted for use in 1984, was successful, and ended the long-standing crisis over the Bible revision. The text form of the Old Testament in the Luther Bible from 1984 corresponded (with small corrections in 1975) to the state of research from 1964.

Influence of Liberal Theology on Revision

In the Luther Bible of 1984 there are unusual interpretations and text changes in some places when the text is revised. These refer, for example, to a choice of words that is as gender-neutral as possible or a subtle representation of the wrath of God .

First forms of gender-neutral language

In the LB 1984 a “gender-neutral” formulation was chosen for certain Bible texts for the first time, which later also became accepted in other translations and revisions. A good example is 1 Corinthians.

1 Corinthians 16:13

Text according to NT Graece (NA28): Γρηγορεῖτε, στήκετε ἐν τῇ πίστει, ἀνδρίζεσθε , κραταιοῦσθε.

LB 1545 Watch, stand in faith, be male , and be strong!

LB 1984 to 2017 Wachet, stand in faith, be brave and be strong!

The text passage is identical to the later revision from 2017, which dealt more intensively with questions of gender-neutral translation and is known in certain circles for its “feminist traits” and translations. Literally speaking, “ courageous ” must be called a mistranslation, since the original text uses the word “ ἀνδρίζεσθε ”, which literally means: “Act like men”. Luther translated it in a similar way. The meaning of the textual statement can, however, mean courageous action, as it was also translated communicatively and dealt with in theology. However, many (evangelical) Christians who prefer philologically accurate translations criticize this choice of words.

The weakening of the biblical motif of the "angry God"

In Psalm 94 an unusual change was made in the revision.

Psalm 94: 1

Text according to the Biblia Hebraica: אֵל־ נְקָמֹ֥ות יְהוָ֑ה אֵ֖ל נְקָמֹ֣ות הֹופִֽיַע׃

LB 1545 to 1975 LORD God who is vengeance / God / who is vengeance / appear

LB 1984 Lord, you God of retribution , you God of retribution , appear!

(LB 2009 God of Retribution , Lord, you God of Retribution , appear! ) *

LB 2017 Lord, you God, who is vengeance , you God, who is vengeance , appear!

* The LB 2009 ( NeueLuther ) is not a church revision of the Luther Bible, but a private edition of the LB 1912, which is in the public domain .

Psalm 94: 1 is a deep intervention in the biblical text and its theological interpretation. This happened against the background of liberal theology , which, under the influence of Friedrich Schleiermacher, does not see the doctrine of the wrath of God as beneficial for Christians. The Hebrew word “נְקָמָה” literally means “ revenge ”, which today leads to critical statements by evangelical Christians, as they often prefer translations that are as formal and philological as possible. The NeueLuther (or Luther Bible from 2009 ), a privately distributed revision of the now public domain LB 1912, adopts this choice of words and therefore reads very similarly to LB 1984, although it is mainly used by evangelical circles. With the motif More Luther , a withdrawal of “unnecessary” linguistic modernization, this change was withdrawn in the 2017 revision.

Spelling of Biblical Names

On the occasion of the 1984 revision, the spelling of biblical names was also reorganized. The 1975 revision adopted the ecumenical spelling of biblical proper names; The 1984 Luther Bible again offered the traditional form for many names: Nazareth instead of Nazareth , Capernaum instead of Capernaum , Ezekiel instead of Ezekiel , Job instead of Job .

Follow-up revision from 1999

In 1999, on the occasion of the changeover to the new spelling, minor changes were made to the Luther Bible. The most important is the extensive replacement of "woman" by "woman", following the example of the evangelical agendas . In addition, the name " Palestine " has been replaced by "The land of the Bible" on the maps .

Luther Bible from 2017

What began in 2010 as a "review" developed into a revision of the entire Bible text. For the first time since 1912, the Luther Bible was revised from a single source and based on uniform criteria. The translation should primarily be checked against the original texts. However, as the client, the EKD Council wanted to prevent the exegetes from creating a “New Wittenberg Bible”, comparable to the new Zurich Bible . That is why they were given "to maintain the special profile of this theology and church, piety and culture formative Germanization". The procedure chosen for the revision differed from the revision of the standard translation, which took place around the same time.

- Around 50 exegetes each examined a biblical scripture or scripture group in the text version from 1984 verse by verse.

- In one of six teams of exegetes, each for a biblical group of scriptures (corresponding to the six parts of the first complete edition from 1534), their proposed changes were collected, discussed and further developed.

- A steering committee set up by the EKD Council headed by Former Bishop Christoph Kähler decided on the proposed changes with a majority. This committee was supposed to ensure the consistency and the familiar sound of the Luther Bible. The translation decisions of the Zurich Bible 2006 and the standard translation were compared across the board. The exegetes were able to criticize a decision of the steering committee, then a new discussion took place. The final editorial team included: Professors Martin Karrer (New Testament Coordinator), Christoph Levin (Old Testament Coordinator), Martin Rösel (Apocryphal Coordinator), Corinna Dahlgrün (Practical Theology: Liturgy), Werner Röcke (German Studies: Early New High German). The EKD sent: Johannes Friedrich , Gerrit Noltensmeier and Thies Gundlach . The German Bible Society was represented by Hannelore Jahr and Annette Graeber. Jürgen-Peter Lesch was the managing director.

-

The EKD Council was kept informed about the progress of the work and any difficulties that arose.

In 2017 the storm at sea ( Matth. 8:24 ) turns into a tremor in the sea, exactly according to the Greek text . No other Bible translates like this; the change was long controversial in the commission. (Painting by James Tissot , Brooklyn Museum )

In 2017 the storm at sea ( Matth. 8:24 ) turns into a tremor in the sea, exactly according to the Greek text . No other Bible translates like this; the change was long controversial in the commission. (Painting by James Tissot , Brooklyn Museum )

Appreciation of the Apocrypha

The most important task was the production of a reliable text for the Apocrypha , most of which had been available as translations from the Vulgate until then. This had also led to a different chapter and verse counting from the EÜ . This scientifically and ecumenically unsatisfactory state was ended with the 2017 revision. The books Judit , Tobias , Jesus Sirach , the 1st book of the Maccabees , the pieces on Esther and the Manasseh prayer were newly translated from Greek, using a language approximating Luther German, so that the Apocrypha fit stylistically with the rest of the Bible . Overall, the 2017 revision deviates about 44% of the verses from the 1984 version; most of the changes are found in the apocrypha.

More Luther

“In the 16th century, Luther's language was modern. Today it is unusual. It hits a nerve of religion when religion means the encounter with the extraordinary. Many readers… are particularly impressed by this extraordinary sound of speech. Of course, this means that in order to do Luther overall justice, we need modern translations in addition to the Luther Bible ... ”( Martin Karrer )

The revision reversed many linguistic modernizations of the 1984 edition. This makes the text, especially in Paul's letters , more difficult to understand. That was accepted. The Luther Bible is regarded as a cultural asset and a unifying bond of evangelical Christianity; but it is not a Bible that should be the most suitable translation for all milieus, age groups and situations. The editors from 1984 had made this claim.

In some places the 2017 revision even returns to Luther's wording from 1545. This is mostly due to a paradigm shift in Old Testament exegesis: where the Masoretic text is difficult to understand, the exegesis of the 20th century liked to produce a supposedly better text through conjecture or it had switched to the Greek translation. Today, on the other hand, people trust the Masoretic text more and translate what is there. Since Luther did the same thing in his day, the 2017 Luther Bible contains “more Luther” again.

Translated more consistently from the original text editions

All revisions since 1912 agreed that the Luther Bible should be based on the best scholarly Urtext editions; in the implementation, however, they were reluctant to make changes to known texts. Here the revision from 2017 is clearer than the NT Graece . An example from the Sermon on the Mount :

Matthew 6,1a

NT Graece: Προσέχετε [δὲ] τὴν δικαιοσύνην ὑμῶν μὴ ποιεῖν ἔμπροσθεν τῶν ἀνθρώπων πρὸς τὸ θεαθῆναι αὐτοῖς

Textus receptus : προσεχετε την ελεημοσυνην υμων μη ποιειν εμπροσθεν των ανθρωπων προς το θεαθηναι αυτοις

LB 1545 Pay attention to alms / the one who does not give for the people / the one who is seen by them.

LB 1912 Pay attention to your alms that you do not give them in front of the people so that you will be seen by them.

LB 1984 Take care of your piety that you do not practice it in front of people to be seen by them.

LB 2017 But be careful that you do not practice your righteousness in front of people in order to be seen by them.

“Righteousness of God” in Romans

Luther learned his doctrine of justification from Paul , but his positions are not completely congruent with Paul's. Today this is the consensus of Protestant and Catholic exegetes. In Luther's translation of the Romans , Paul's argumentation is in some places almost overlaid with Lutheran theology. “You can call that awesome and you can call it wrong. In any case, it does not offer a philologically clean translation of the Bible. ”Nevertheless, the Luther Bible of 2017 brings Luther's interpretive translation in the main text and the translation required by the Greek original text in footnotes: Romans 1.17 LUT ; Romans 2,13 LUT ; Romans 3:21 LUT ; Romans 3,28 LUT .

A language that is becoming more just for women and Jews

With a view to their use in worship and teaching, it was also examined how women are discussed in the Luther Bible and what image of the Jewish religion this Bible paints.

Changes to anti-Judaism statements

The most important change can be found in Romans , where Paul faces the problem that the majority of Israel rejects Christ. Here the revision returned to a formulation by Luther.

Romans 11.15 εἰ γὰρ ἡ ἀποβολὴ αὐτῶν καταλλαγὴ κόσμου, τίς ἡ πρόσλημψις εἰ μὴ ζωὴ ἐκ νεκρῶν;

LB 1545 Because if the world is ever lost / what would it be different / because the life of the dead take?

LB 1912 to 1984 For if their rejection is the reconciliation of the world, what will their acceptance be but life from the dead!

LB 2017 For if their loss is the reconciliation of the world, what will their acceptance be but life from the dead!

Influence of feminist theology

The Luther Bible 2017 changed some passages where Luther chose discriminatory formulations for women, which the revisers felt were not required by the original text, or where a gender-neutral choice of words seemed appropriate to them. An example from the creation story :

Genesis 2:18 לא־טוב היות האדם לבדו אעשה־לו עזר כנגדו ׃

LB 1545 (And the LORD God spoke) It is not good that man should be alone / I want to make him an assistant / who should be .

LB 1984 It is not good that man should be alone; I want him a helpmate do meet for him .

LB 2017 It is not good that the person should be alone; I want to make him a help that suits him .

The 1984 footnote became the main text in 2017.

Further changes to the traditional text do not go beyond what z. B. can also be found in the revised standard translation or the Zurich Bible , e.g. B. Junia (not Junias), "famous among the apostles" (Romans 16: 7) and the phrase "brothers and sisters" instead of "brothers" wherever in the Acts of the Apostles and in the letters of the New Testament according to the understanding of the text Exegetes the whole community is meant. But “fathers” did not become “ancestors” and “sons” only became “children” if Luther had already translated that way.

Romans 16: 7

Text to NT Graece (NA28): Ἀνδρόνικον καὶ ἀσπάσασθε Ἰουνίαν τοὺς συγγενεῖς μου καὶ συναιχμαλώτους μου, οἵτινές εἰσιν ἐπίσημοι ἐν τοῖς ἀποστόλοις, οἳ καὶ πρὸ ἐμοῦ γέγοναν ἐν Χριστῷ.

LB 1545 Greet Andronicus and Junias , my friends and fellow prisoners, who are famous apostles and have been before me in Christ.

LB 1984 Greet Andronicus and Junias , my relatives and fellow prisoners, who are famous among the apostles and have been with Christ before.

LB 2017 Greet Andronicus and Junia , my relatives and fellow prisoners, who are famous among the apostles and were in Christ before me.

1 Thessalonians 5:14

Text by NT Graece (NA28): Παρακαλοῦμεν δὲ ὑμᾶς, ἀδελφοί , νουθετεῖτε τοὺς ἀτάκτους, παραμυθεῖσθε τοὺς ὀλιγοψύχους, ἀντέχεσθε τῶν ἀσθενῶν, μακροθυμεῖτε πρὸς πάντας.

LB 1545 But we admonish you, dear brothers , admonish the naughty, comfort the faint-hearted, bear the weak, be patient with everyone.

LB 1984 But we admonish you, dear brothers : Correct the disorderly, comfort the faint-hearted, bear the weak, be patient with everyone.

Lb 2017 But we admonish you: reprove the negligent, comfort the faint-hearted, bear the weak, be patient with everyone.

The new Luther Bible in the anniversary year 2017

On September 16, 2015 , the EKD paid tribute to the completion of the revision with a reception at the Wartburg ; the German Bible Society was entrusted with the production and distribution of the new Bible.

The book designers Cornelia Feyll and Friedrich Forssman developed the new appearance of the Luther Bible 2017 .

The book was officially handed over to the congregations in a festive service on October 30, 2016 in the Georgenkirche in Eisenach with the participation of the EKD Council Chairman Heinrich Bedford-Strohm and the EKD Reformation Ambassador Margot Käßmann . Specifically, this meant that several regional churches gave their congregations new altar Bibles for Reformation Day .

The full text is available as a free app for the mobile platforms iOS and Android . This offer was initially limited to October 31, 2017, but is now unlimited.

Reviews

“Finally pulled away the gray veil,” praised Stefan Lüddemann in the Neue Osnabrücker Zeitung ; What is meant are: the "dampening improvements" with which earlier revisions brought the Luther Bible closer to the contemporary language. The opinion that the Luther Bible of 2017 has greater linguistic power than the previous version is generally shared. Christoph Arens ( KNA ) invites you to discover “language treasures” in this book.

The return to Luther's language did not convince everyone. Example: 1 Corinthians 13.1 to 13 LUT "and had the love does not" - an obsolete formulation ( genitivus partitivus ) , but was the steering committee at heart. For Bernhard Lang ( Neue Zürcher Zeitung ), the Luther Bible from 2017 has "largely a museum character". The German Lutherans thus used their Bible language, which has become a special language. Karl-Heinz Göttert criticizes the balancing of the revision between philological accuracy and the familiar sound of the Luther Bible: "With a certain arbitrariness, people sometimes let Luther be, sometimes agreed that the philologists were right."

Michael Rohde finds the revised Luther Bible to be both powerful and pastoral, and although it is a wealth to use many Bible translations in a congregation, this edition is particularly suitable for reading together. The high-quality book design also contributes to this.

Some evangelical critics, on the other hand, complain that the churches are unsettled by the amount of text changes, many of which are unnecessary or strange; The factual and verbal explanations in the appendix, whose authors can be recognized as Old and New Testament scholars with a university background, are rejected (as in 1984). The conservative evangelical theologian and publicist Lothar Gassmann speaks of a “feminist falsification” and describes the 2017 edition as “not recommended for believing Bible readers”. In his Christian magazine The Narrow Path he writes:

- “All in all, unfortunately, one has to say that the biblical-critical ideology, which the Evangelical Church in Germany as a whole and the processing team in particular follows, has left bad and offensive traces in the 2017 Luther Bible. [...] The arbitrary treatment of the Reformer's Bible, characterized by a lack of reverence for God's Word, also shows a general attitude: The Evangelical Church in Germany, which has drifted far from the biblical faith, is also following the spiritual legacy of the Reformation Generally around. Luther is faked in speeches, but his real concern has long been betrayed and buried. One celebrates '500 years of the Reformation', but one is busy removing the last traces of the Reformer's positive spiritual legacy [...] "

In accordance with his conservative Protestant values, Gassmann also criticizes the Evangelical-Catholic ecumenism and thus the revaluation of the Apocrypha in the LB 2017.

The reviewer of the SELK judges that the explanations on baptism and the Lord's Supper in the appendix do not correspond to the statements of the Lutheran confessions.

The Seventh-day Adventist reviewer believes that the Luther Bible from 2017 translates more faithfully overall; he does not see a “feminist tendency”.

Fundamental objection comes from the Reformed side: “Another building block of Luther's homage and a missed opportunity to update the concerns of the Reformation.” Strictly speaking, the criticism is directed against the fact that so much expertise was brought into the revision of a historical Bible instead of to submit a high quality new translation for the Reformation year.

Current sales figures

- Luther Bibles of the German Bible Society 2006–2016: 1.8 million copies

- Luther Bible 2017 from the start of sales (October 19, 2016) to the end of 2016: over 307,000 copies; For comparison: from the start of sales in Advent 2016 to March 2017, around 120,000 copies of the revised standard translation were sold.

Subsequent corrections

The Luther Bible published in the year of the Reformation contained misinformation from the field of numismatics in the additions : a table on the "value of the coins mentioned in the New Testament" (p. 318) with the incorrect relation 1 denarius = 64 aces, which as a consequential error leads to largely incorrect, the figures in this table, which were inflated by a factor of 4, and correspondingly unrealistic assumptions about the purchasing power of the population at the time. In addition (p. 317) the weight of a drachm was given as 14 g of silver. 2018 was corrected: 1 denarius = 16 aces, 1 drachma weighs 4 g.

Influence on other Bible translations

The first Protestant Bible translations into the English language

William Tyndale (1494–1536) was the first English reformer and Bible translator to use the Greek text as the basis for his work. The publication of the September Testament encouraged him to translate the Bible into English himself. For the translation of the New Testament into English he used the Greek NT of Erasmus, the Vulgate as well as Luther's December Testament. Much like Luther's translation on the Wartburg, a complex picture emerges if one asks which of his three sources he prefers in each individual case and why. He learned German and read Luther's New Testament before starting to print his New Testament in 1525. His work had a major influence on later English Bible translations, including the King James Bible (1611). The use of the December will is evident in Tyndale's prefaces and marginal glosses, as well as in the order of the biblical books .

The later Bible translator Miles Coverdale (1488–1569) was also influenced by the Luther Bible when translating some books of the Old Testament, which were then included in the Coverdale Bible (1535) and Matthew's Bible (1537).

The translation of the Torah by Moses Mendelssohn

Moses Mendelssohn translated the books of the Torah into High German in 1783, written with Hebrew letters in Rashi script , in order to be able to offer Jewish readers with little knowledge of Hebrew a stylistically appealing and precise (but not literal) translation in the Jewish tradition. He made positive reference to the Luther translation. To compare both translations, a text example in the transcription by Annette M. Boeckler ( Genesis 2: 18.22-24 LUT ):

The Eternal Being, God, also said: “It is not good that man should remain alone. I want to make him a helper who is around him. ” […] The eternal being, God, formed this rib, which he had taken from man, into a woman and brought it to man. The human said, this time it is bone from my legs and flesh from my flesh. This should be called "male", because she was taken from the male. That is why the man leaves his father and mother and clings to his wife, and they become like one flesh.

Evangelical Bibles

Some Bibles from the area of Protestant Free Churches were created in contrast to the Luther Bible. They are aimed at a readership that is familiar with Luther's language but wants a Bible that is more accurately translated or more communicative. It remains an aesthetic fascination; the translators are constantly in conversation with the Luther text. Example:

Psalm 23: 4 גם כי־אלך בגיא צלמות לא־אירא רע כי־אתה עמדי שבטך ומשענתך המה ינחמני ׃

- LB 2017 And if I have already hiked in the dark valley, I fear no misfortune; because you are with me, your stick and staff comfort me h.

- Elberfeld Bible : Even when I wander in the valley of the shadow of death, I fear no harm, because you are with me; your stick and your staff , they comfort me .

- New Life Bible : Even when I walk through the dark valley of death, I am not afraid, because you are by my side. Your stick and staff protect and comfort me.

Where a modern translation does not (any longer) expect such a readership, it sounds significantly different:

- Hope for everyone : Even if it goes through dark valleys, I fear no misfortune, because you, Lord, are with me. Your staff gives me protection and comfort .

- Good news Bible : And I also have to go through the dark valley - I fear no disaster! You, Lord, are with me; you protect me and you guide me , that gives me courage.

- New evangelistic translation : Even on the way through the darkest valley I am not afraid, for you are with me. Your staff and your shepherd's staff , they comfort and encourage me.

Catholic Bibles

For Catholic Bibles of the 16th century: see Correction Bibles .

The Luther Bible was placed on the index after the Council of Trent ( biblical ban ), and it remained there until the Romanus Index was abolished . Before the Second Vatican Council , there were several Catholic Bible translations that officially had nothing to do with Luther, but they were subtle: They “risked furtive glances and were not allowed to admit who helped them to find a good expression”.

The ecumenically responsible single translation

The uniform translation (EÜ) is also influenced by Luther. Psalms and the New Testament were translated jointly by Protestant and Catholic exegetes; At that time there was hope that the standard translation could develop into the common Bible for all German-speaking Christians. In order to increase acceptance among Protestant readers, the EÜ took on well-known formulations from the Luther Bible, e.g. B. Ps 124,8 LUT : "Our help is in the name of the Lord ..."

- The revised standard translation from 2016

The revision of the EÜ wanted u. a. Avoid contemporary linguistic fashions. The Luther Bible became a treasure trove for classical formulations. In doing so, they did not shy away from archaisms that were difficult to understand, such as “laborious” in the outdated meaning “troubled by effort” instead of today's “laboriousness”. Although the Roman instruction Liturgiam authenticam (2001) in No. 40 stated that “one must do everything possible not to adopt a vocabulary or a style which the Catholic people could confuse with the language used by non-Catholic ecclesiastical communities […] , ”The revised ES contains“ more Luther ”than the unrevised one. Examples:

Psalm 8,5a : מה־אנוש כי־ תזכרנו

EÜ unrevised: What is the person that you think of him ?

EU revised: What is man that you think of him ?

Psalm 26: 8a יהוה אהבתי מעון ביתך

EÜ unrevised: Lord, I love the place where your temple is .

IE revised: Lord, I love the place of your house .

Psalm 145:16 פותח את־ידך ומשביע לכל־חי רצון ׃

EÜ unrevised: You open your hand and satisfy every living thing, with your favor .

EÜ revised: You're doing your hand on and satisfy every living thing with favor .

Matthew 4,4 οὐκ ἐπ 'ἄρτῳ μόνῳ ζήσεται ὁ ἄνθρωπος