Lutherstadt Eisleben

| coat of arms | Germany map | |

|---|---|---|

|

Coordinates: 51 ° 32 ' N , 11 ° 33' E |

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Saxony-Anhalt | |

| County : | Mansfeld-Südharz | |

| Height : | 114 m above sea level NHN | |

| Area : | 143.87 km 2 | |

| Residents: | 23.003 (Dec. 31, 2019) | |

| Population density : | 160 inhabitants per km 2 | |

| Postal code : | 06295 | |

| Primaries : | 03475, 034773, 034776 | |

| License plate : | MSH, EIL, HET, ML, SGH | |

| Community key : | 15 0 87 130 | |

| LOCODE : | DE A | |

| NUTS : | DEE0A | |

| City structure: | 11 districts | |

City administration address : |

Markt 1 06295 Lutherstadt Eisleben |

|

| Website : | ||

| Mayor : | Carsten Staub (independent) | |

| Location of the city of Lutherstadt Eisleben in the district of Mansfeld-Südharz | ||

The Lutherstadt Eisleben [ ˈa͜isleːbn̩ ] is the second largest city in the district of Mansfeld-Südharz in the eastern Harz foreland in Saxony-Anhalt . It is known as the place of birth and death of Martin Luther . In honor of the city's greatest son, Eisleben has been nicknamed "Lutherstadt" since 1946. The Luther memorials in Eisleben and Wittenberg have been UNESCO World Heritage Sites since 1996 . Eisleben belongs to the Federation of Luther Cities . The Luther sites in Eisleben and Wittenberg were combined to form the Luther Memorials Foundation in Saxony-Anhalt .

Eisleben extends over an area of about 25 by 10 kilometers, as several surrounding communities have been incorporated. The largest district is Helfta with the 1999 revitalized monastery .

geography

The core city is 30 km west of Halle (Saale) in a long lowland tongue, the so-called Eisleben lowland in the south-eastern part of the district. The urban area through which the evil seven flows is dominated by agricultural land. Between Unter- and Oberrißdorf the landscape rises to the Mansfelder Platte , a low mountain plateau , the urban area covers the main part of the Platte. The southern part of the urban area is traversed by the wooded ridge of Hornburger Sattel , the southernmost district of Osterhausen is almost in the Helmetal .

Neighboring communities

Neighboring communities are Gerbstedt in the north, Lake Mansfelder Land in the east, Farnstädt and Querfurt (both Saalekreis ) in the south, and Allstedt , Bornstedt , Wimmelburg , Hergisdorf , Helbra and Klostermansfeld in the west.

City structure

In addition to the core city with the districts of Ernst-Thälmann-Siedlung and Wilhelm-Pieck-Siedlung , to which the two smaller towns Neckendorf and Oberhütte also belong, the city is divided into the following districts with the date of incorporation:

| Locality | Residents | Incorporation | The districts of Eisleben |

|---|---|---|---|

| Helfta | about 6,000 | January 1, 1960 | |

| Volkstedt | 1,271 | January 1, 2004 | |

| Rothenschirmbach | 672 | January 1, 2005 | |

| Wolferode | 1,309 | January 1, 2005 | |

| Pollen life | 1,079 | January 1, 2006 | |

| Unterrißdorf | 461 | January 1, 2006 | |

| Bischofrode | 693 | January 1, 2009 | |

| Osterhausen | 1,031 | January 1, 2009 | |

| Schmalzerode | 288 | January 1, 2009 | |

| Hedersleben | 755 | January 1, 2010 | |

| Oberrißdorf | about 200 | January 1, 2010 | |

| Burgsdorf | 196 | January 1, 2010 |

Waters

Several brooks flow in the urban area, for example the Böse Sieben in the city center . It arises as the confluence of seven streams from the Vorharz and is called evil because its floods used to be particularly devastating. The bad seven flows east to the sweet lake . Another river is the Schlenze in the north, it rises in Polleben and then flows in a north-east direction to the Saale . The Schlenze can also rise sharply during floods. The Glume, which rises south of Helbra and flows east of Eisleben into the Böse Sieben, and the Laweke, which rises in the Hedersleben district and then flows off to the east , are to be mentioned as smaller streams . The valley of the Hegebornbach south of Volkstedt is beautifully landscaped , this brook rises west of Volkstedt, then flows through the village and then flows east of Eisleben into the Glume. The most important body of water in the south is the Rohne, which begins near Bornstedt and flows through the Osterhausen district.

climate

The average air temperature in Eisleben-Helfta is 8.5 ° C, the annual precipitation 509 millimeters. It is so low that it falls into the lower twentieth of the values recorded in Germany. Lower values are registered at only 2% of the German Weather Service's measuring stations . The driest month is February, with the most rainfall in June. In June there is 1.9 times more rainfall than in February. The precipitation hardly varies and is very evenly distributed over the year. Lower seasonal fluctuations are recorded at only 7% of the measuring stations.

history

The time of the great migrations

In the 3rd to 5th centuries, the time of the migrations , Suebian tribes, fishing and warning from the Holstein, Schleswig and Mecklenburg area moved south. West of the Elbe and Saale as far as Thuringia, this path can be traced by the endings of the place names “-leben”. For example, between Haldensleben and Erfurt, around 100 towns and villages with this ending in the place name emerged. According to Hermann Großesler , the word “life” in this context means heritage or genetic material. The front part of this place name refers to the clan of the landlords.

In the 5th century, the immigrants mixed with the resident Hermundurs and belonged to the Thuringian Empire , which was ended in 531 by the Franks . Northern Thuringia was settled as a result of the defeat by Saxony. In the further course of history, Franconian kings settled Swabian, Hessian and Frisian farmers in some regions. Dormer designations such as Schwabengau , Hassegau and Friesenfeld were created .

The middle age

The moated castle at the Faulen See

In the 9th and 10th centuries, a moated castle was built on the west bank of the so-called "Lazy Lake". On November 23, 994 Eisleben is in a document of the later Emperor Otto III. named as one of six places that had previously received market privileges including coinage and customs rights. The market town, which developed at the intersection of two trade routes and under the protection of the royal moated castle, was a royal table goods in which the taxes from the surrounding villages were received.

The garlic king

In 1081, the Saxon princes in Eisleben confirmed the election of Hermann von Luxemburg (1053-1088), Count von Salm, to be the anti-king of Henry IV while he was in Italy . Hermann resided in the Eisleber moated castle and was besieged by Heinrich's troops from Friesland. Count Ernst von Mansfeld came to the rescue and defeated the Frisians. For a long time the battlefield was called Friesenstrasse, today Freestrasse. After Hermann could not collect enough support to enforce his claim to the throne until 1084, he left the city. Since a lot of garlic is said to have grown in front of the walls of the castle at that time, he was called the "king of garlic". On the north wall of the town hall there is a sandstone sculpture which, according to tradition, represents the king. Today he is an image figure in tourism advertising.

First documented mention as a city

In 1069 that got sex of Mansfeld , who had his family seat in Mansfeld of Emperor Henry IV. The Gaugrafenamt . Eisleben soon developed into the capital of this county. From 1121 the Counts of Mansfeld appointed a city bailiff for the city's government. It was not until 1809 that Eisleben had an independent mayor who had not been appointed by the authorities. Around 1150, the draining of the "Faulen See", a wetland on the eastern edge of the settlement area, began. Bishop Wichmann of Magdeburg had called in Frisians and Flemings for the construction of drainage ditches and dams, which were then settled in the later Nicolaiviertel. The traces can still be read today by means of many ditches and dams, for example on the Landwehr.

In the middle of the 12th century, the construction of the first city wall, which encompassed the market and the surrounding streets, began. The wall was built by the townspeople, and each craft guild was responsible for maintaining and defending a section. Guarding the gates was the responsibility of the city servants paid by the city. This wall only surrounded the market and a few surrounding streets.

In 1180 Eisleben was first mentioned as a city (civitas) with twelve councilors (consules) under the direction of the town bailiff. The townspeople had to pay taxes to the Counts of Mansfeld , and the town had lower jurisdiction. The oldest known coinage of the Eisleber coin dates back to 1183. There were two parishes, St. Andreas and St. Gotthard.

The origin of copper slate mining

Around the year 1200, a copper ore deposit was opened up for the first time on the Kupferberg in Hettstedt ; According to legend, the miners Nappian and Neucke, who are the symbolic figures of the Mansfeld mining industry to this day. At first the farmers were still digging on their own land, but it soon became a business. The mining rights ( Bergregal ) granted Emperor Friedrich II. The Mansfeld Counts in 1215; In 1364 it was confirmed by Charles IV . Mining changed the economic structure and became the basis for the wealth of both the counts and the city.

The Helfta monastery

The Cistercian Monastery of St. Maria was founded by Count Burchard I of Mansfeld in 1229 and was initially built near Mansfeld Castle. This also included the Katharinenhospital in Eisleben. In 1234, Count Burchard's widow relocated the monastery to the current desolation of Rossdorf (northwest of Eisleben, near the Katharinenhölzchen, written Rodhersdorf in 1229, last mentioned as Rostdorff in 1579), whose location close to Castle Mansfeld was of course not wisely chosen. But Rossdorf also turned out to be an unfavorable place due to the great lack of water.

In 1258, at the instigation of Abbess Gertrud von Hackeborn , the monastery was moved to Helfta , today's district of Eisleben. The abbess had bought the piece of land in Helfta from her brothers Albrecht and Ludwig, who held the castle and rule in Helfta. As early as 1284, however, the monastery was plundered by Gebhard von Querfurt.

During the unsuccessful siege of the city by the Duke of Braunschweig in 1342, the surrounding villages and thus the monastery were destroyed. Then the fifth extension of the city wall began. The monastery was moved to the edge of the city fortifications on today's monastery square in Eisleben. But this should not be the last hike of the Convention, because in 1525, which was monastery New Helfta in the Peasants' War by the rebellious peasants devastated, after which the Abbess Catherine of Watzdorf and the nuns fled first to Halle before on the orders of Emperor Charles V. were sent to Moravia to re-establish an abandoned monastery there. But already in the same year they returned to Alt-Helfta at the request of Count Hoyer , who had the monastery restored. The nuns had no permanent home there either.

The Reformation forced the introduction of Protestant worship in 1542. When all efforts to convert the women under the last abbess Walburga Reubers to Protestantism failed, the monastery was dissolved under the Protestant Count Georg von Mansfeld-Eisleben in 1546. The nuns left. The last documented mention of the monastery was dated June 19, 1542. Many farmers from the destroyed villages now settled, with the Count's permission, south of the city wall, beyond the Bad Seven (at that time still Willerbach). In the Rammtorstraße today are the typical agricultural town houses .

The monastery subsequently fell into disrepair and was used as a warehouse in GDR times. Its reconstruction began in 1998 after some initiatives under the art teacher Joachim Herrmann had campaigned for it since 1988. The Cistercian women now also run a guest house and an educational establishment .

Construction and fire in 1498

A century of steady growth followed. During the Halberstadt bishop's feud in 1362, the city fortifications proved their worth against the besiegers. The Heilig-Geist-Stift was first mentioned in documents in 1371 and in 1408 the first stone town hall was built. In 1462 the choir of the St. Nicolai Church was consecrated, which had been built on the foundation walls of the Gotthard Church. In 1433 a department store and clothing store with scales was mentioned on the market square; the location corresponds to the house Markt 22. In 1440 the town had 530 house owners and around 4,000 inhabitants. The construction of the towers for St. Petri-Pauli began in 1447, for the Nicolaikirche and the Andreaskirche in 1462.

In 1454 the city council acquired the lower courts within the Petrification from the Counts of Mansfeld as pledge for 900 Rhenish guilders. The counts could never redeem the pledge.

Martin Luther was born on November 10, 1483 in Langen Gasse ( suburb of Brückenviertel, trans aquam ), today's Lutherstrasse . The next day, Martin's Day, he was baptized in the Church of St. Petri Pauli. The Luther family only stayed in Eisleben until the spring of 1484. Through his baptism, Luther remained connected to the city throughout his life. City administration and tourism have endeavored in recent years to work out this link more intensively; this is especially true for 2017, the anniversary year of the Reformation.

A second city wall was built between 1480 and 1520. The suburbs Petriviertel (farmers), Nicolaiviertel (Frisians) and Nussbreite (miners) came into the city. In 1498, a devastating fire ravaged the city within the first ring of the wall. In addition to the many residential buildings, the town hall burned down and St. Andrew's Church was damaged. Only through a five-year tax exemption from the Mansfeld counts could a drastic migration of the population be averted.

Renaissance

The reconstruction of the old town, including the suburbs

After the devastating city fire of 1498 within the oldest city wall (Andreas- / Marktviertel), reconstruction began on August 17th, 1498, based on the privilege of the Mansfeld Counts. This initially took place comparatively quickly, with late Gothic architectural elements being used in the first phase. For the inclusion of the suburbs in the expanded wall ring and the water supply it proved to be beneficial that 1480–1566, when the Magdeburg archbishops were also administrators of Halberstadt, the Mansfeld counts for market district (Diocese of Halberstadt) and suburbs (Archbishopric of Magdeburg) only one Person as feudal lords. 1520–1540 the Reformation was carried out in several steps in Eisleben and the county of Mansfeld, including a Protestant boys' school founded under Agricola in 1525 , which became the forerunner of the Latin school (grammar school) established in accordance with the Lutheran Treaty of 1546.

The transition from late Gothic to Renaissance styles can be seen at the town hall in the old town , the Hinterort seat (1500/1589) and the furnishings in the St. Andrew's Church. Berndinus Blanckenberg (around 1470–1531), who was councilor from 1507 and city bailiff from 1518, played a special role in the reconstruction of the city; his Renaissance epitaph, created by Hans Schlegel in 1540, is in the St. Andrew's Church. In the church there is the grave tumba (1541) of Count Hoyer VI by the same artist .

After 1530, due to the crisis in the Mansfeld mining industry, construction was no longer carried out with the same intensity as in the first third of the 16th century, but the Campo Santo was built in 1538/1560, the Latin school was built in 1564, and the renaissance tower dome of the St. Paul Church, 1568 of the economic building of the Katharinenstift, 1571–1589 of the Neustadt town hall and 1585–1608 the completion of the Annenkirche .

After the city fire of 1601, which destroyed, among other things, the Renaissance moated castle, the Mittelort city seat, the grammar school, the Libra and numerous town houses, no such considerable reconstruction could take place. This resulted, for example, from the sequestration of the Mansfeld Counts in 1570, the permutation recesses 1573/1579, in which the Electorate of Halberstadt and Magdeburg exchanged Eisleben with its suburbs, the burdens of the Thirty Years' War and the decline of mining and the industries dependent on it until his release of mining in 1671 by the Elector of Saxony. In addition to the existing complex administrative structures (there was also a count's administration until 1780), all of this led to an economic decline in the city, which lasted until the end of the 18th century and was also evident in the building work.

Neustadt and Reformation

In 1501 the house of the Counts of Mansfeld split into the Mansfeld-Vorderort, Mansfeld-Mittelort and Mansfeld-Hinterort families . At the beginning of the 16th century, each of these families built a city residence in Eisleben. Count Albrecht IV. (1480–1560), a member of the Hinterort branch , settled miners and ironworkers from other areas of Germany west of the old town to revitalize the mining industry and also granted this settlement town charter. They were called "New Town near Eisleben", today "Neustadt" or "Annenviertel".

The Neustädter Rathaus (town hall) was built on today's “Breiten Weg” from 1571 to 1589 , into which the regional and municipal court moved in 1848 and then the district court until 1853. This is why the house is also known as the "Old Court". In 1514, Emperor Maximilian I asked Albrecht to cancel the town charter. However, Albrecht opposed this demand and instead founded the Annenkloster mit Kirche, an Augustinian hermit monastery, where he met Luther in 1518. In 1520 the General Convention of the Augustinians decided in favor of Luther's teaching in the Annenkloster. In 1523 the monastery dissolved.

While the Counts of Mansfeld-Vorderort held fast to their Catholic faith, the representatives of the Mansfeld-Hinterort family under Gebhard VII and above all Albrecht VII , who was a close friend of Luther, joined the idea of the Reformation. In 1525 they introduced Protestant teaching and decided to found a Protestant school next to St. Andrew's Church. Yet they treated their subjects no better or worse than their Catholic relatives did. When the peasant wars , in which many dissatisfied miners from Eisleben took part, devastated large parts of the Mansfeld county, Albrecht VII had the rioting bloody and mercilessly put down. The turmoil of the wars of the Reformation sometimes even caused related Mansfelders to oppose each other on different sides. During the peasant war the Benedictine monastery in wooden cells and the Helfta monastery were also devastated, the nuns were expelled. In 1529, hundreds of ice livers died of the plague . With Count Hoyer IV. Von Mansfeld-Vorderort , one of the most influential opponents of the Reformation died in the Mansfeld region in 1540 (grave tumba in St. Andrew's Church). Luther personally tried several times to settle the disputes among the counts - especially about the Neustadt. In 1546 he came to the city for the last time. On February 16, he and Justus Jonas signed the deed of foundation for the first Latin school, today's Martin-Luther-Gymnasium . Martin Luther died in Eisleben on February 18, 1546. The house where Martin Luther died is dedicated to the memory of this event . Because of its commitment to the Reformation imposed Emperor Charles V in 1547, the imperial ban on Count Albrecht VII. However, it was canceled in 1552 again.

In 1550 another plague epidemic killed around 1,500 people. Many miners left the city, so that in 1554 some of the shafts had to be closed. Wage cuts caused civil unrest and work stoppages. In 1562 the Katharinenkirche burned down and was not rebuilt. In 1567, the Saxon Elector August closed an Eisleber printing works that had printed a pamphlet against his preachers and had the printer arrested. The numerous inheritance divisions, excessive expenses and the poor economic situation led to the bankruptcy of the Mansfeld counts in 1570. They lost the sovereignty of Saxony, which sent a supervisor to Eisleben. Due to the lack of labor in the mining industry, emigration was made a criminal offense.

The 17th and 18th centuries

City fires, plague and the Thirty Years War

The century began in 1601 with the worst fire disaster in the city's history. In the city center, the fire could spread quickly under the half-timbered houses lined up closely together. 253 residential buildings, the superintendent's office, the scale, the towers of St. Andrew's Church and the city palaces of the Counts of Mansfeld were destroyed. The social grievances from which the miners had to suffer led to the siege of the house of the mint master Ziegenhorn on the Breiten Weg on February 8, 1621 . 1000 miners demanded the end of counterfeiting. In 1626 there was another plague epidemic with hundreds of deaths. In 1628 the Thirty Years' War came to Eisleben with Wallenstein , and the town was devastated by the mercenaries of the Catholic League . As a result, mining also came to a standstill. In 1631 troops from both war camps moved through the city several times and forced quarters and provisions. When the Saxon Elector Johann Georg I signed a separate peace with Emperor Ferdinand II in 1635 , thanksgiving services were held in all churches. But already in 1636 the city was sacked by the Swedes. The raids lasted until 1644. In 1653, another city fire destroyed 166 houses, and in 1681 900 people were killed by the plague. Luther's birthplace burned down to the ground floor in the city fire of 1689.

reconstruction

In 1671, the Saxon elector allowed mining in the Mansfeld region to be “released”. This was the prerequisite for the further development and industrialization of mining. In 1691 the weighing house was rebuilt. Luther's birthplace followed in 1693 and was now used as a school for the poor and as a museum.

The house of the patrician family Rinck was rebuilt after the city fire in 1498 at the beginning of the 16th century as the city seat of the Vorderort line, from 1563 it housed the count's office and was completely rebuilt after the fire of 1689 1707. From 1716 the chancellery also performed the tasks of the Prussian part of the county of Mansfeld, which had been released from sequestration, was closed in 1780 due to the feudal fall and from 1789 was the seat of the electoral Saxon governor. On July 14, 1798, on the initiative of the government of the Electorate of Saxony, the Bergschule zu Eisleben was founded as an educational institution for technical mine officials.

19th century

Napoleonic Wars

After the defeat of Prussia in the war against France near Jena and Auerstedt in 1806, French troops occupied the city, although Eisleben had not belonged to Prussia, but to the Electorate of Saxony . In spite of posters in the city that assured "The entire Electoral Saxon state is neutral", all supplies were requisitioned. The French incorporated the former county of Mansfeld into the newly formed Kingdom of Westphalia under Napoleon's brother Jérôme .

Thus serfdom was abolished here too , and freedom of trade , the separation of powers , equal rights for Jews , the civil code and the keeping of church records were introduced. The new town was incorporated into the old town. The abolition of the old regulations enabled Jewish traders to settle in the city, who were able to inaugurate their first synagogue in Langen Gasse , today's Lutherstrasse , in 1814 .

After Napoleon's defeat in the Battle of Leipzig in 1813, Westphalian rule ended in Mansfeld. The Westphalian coats of arms were replaced by Prussian eagles. Eisleben took part in the Wars of Liberation by founding a voluntary pioneer battalion under the command of the Mining Captain of Veltheim (1785–1839).

restoration

In 1815 the former county of Mansfeld was incorporated into the Kingdom of Prussia as a result of the Congress of Vienna . The municipality of Eisleben belonged from 1816 to the Mansfelder Seekreis , which had its district seat in the city. In 1817 a new building was built for the Luther school in the courtyard of Martin Luther's birthplace. The city received its first post office in 1825 as the so-called Land-Fußbothen-Post next to the Petrikirche. In 1826 the Eisleber teachers' seminar was founded on the site behind the Petrikirche. In 1910 it was given a new building in the upper city park, which today houses the Martin Luther Gymnasium . The seminar existed until 1926 and used the Luther School as a practice school. In 1827, with the expansion of the Halleschen Chaussee between the Heilig-Geist-Tor and the Landwehr, the fortification of the Eisleber streets began. In 1835 the new city hospital was completed. In 1847 a famine led to social unrest, which the authorities put down through the use of the military. Because the prayer room had become too small for the steadily growing Jewish community, the building was rebuilt and the now expanded Eisleber synagogue was inaugurated in 1850 .

The industrial revolution

In 1852 the five Mansfeld mining companies merged and formed the Mansfeld copper-slate-building union . In 1858 the last remains of the city fortifications were demolished. In 1863 work began on the Halle-Kassel railway line . The first section to Halle was put into operation in 1865. After the closure of the Ober and Mittelhütte, mining began in the west of the city in 1870 in the Krughütte and the Kupferrohhütte . The first cable car in Europe was built in 1871 between the Martinsschacht and the Krughütte . It was used to transport ore and spoil . On the occasion of the 400th birthday of the reformer, the Luther monument created by Rudolf Siemering was erected and inaugurated on the market square in 1883 .

In 1892, the water of the Salty Lake began to penetrate the mining shafts below, which meanwhile reached below the city center. To save them, the lake was pumped out from 1893 and disappeared from the map. As a result, there was also threatening subsidence in the city of Eisleben. By 1898, more than 440 houses had been damaged as a result, and many had to be demolished. The damage and the renovation measures can still be seen on numerous houses today. The damage to the shafts forced mass layoffs. Together with the resentment about the slow and unjust compensation for the mountain damage, there was ultimately unrest among the population. In 1896, the Mansfeld copper-slate-building union made 500,000 marks available to compensate the house owners.

The 20th century

Between 1908 and the GDR district reform in 1950, Eisleben was a separate urban district .

Upswing and First World War

The century began with the commissioning of the first section of an electric tram in Eisleben. On June 12, 1900, the 700th anniversary of the mining industry was celebrated with a large parade in the presence of Emperor Wilhelm II and his wife. Due to the flourishing mining industry, the general prosperity of the city increased in the period before the First World War. The population rose to over 25,000, and Eisleben became a district-free city and thus left the Mansfeld lake district . New public facilities were: a new building for the mountain school (1903), a new hospital (1904), sewer system and municipal sewage treatment plant, the new upper secondary school on Stadtgraben (today's primary school "Geschwister Scholl"), the new girls' elementary school in Katharinenstrasse (1911) , the new building of the teachers' college (1911) and the regional history museum (1913). In 1909, the miners won the right to form trade union associations.

In the First World War fell after official figures, 575 residents of the city.

Weimar Republic

In the elections to the Prussian state parliament on February 20, 1921, the parties of the left in the central German industrial area received a majority. For fear of a communist takeover, police units of the Prussian police, newly organized by Wilhelm Abegg , were sent to Hettstedt and Eisleben on March 19, 1921 in order to maintain control over the factories. In the course of the March fighting in central Germany , around 100 workers were killed.

Since 1931 the copper production was subsidized by the state in order to prevent the closure of the Mansfeld operations, on which the region was largely economically dependent.

Period of National Socialism and World War II

On February 12, 1933, numerous people were seriously injured and four were killed when an SA troop attacked the office of the KPD sub-district leadership at Breiten Weg 30 (during the GDR era, “Street of the Victims of Fascism”). Since then one speaks of the ice liver Blood Sunday .

On November 9, 1938, the night of the pogrom , members of the SA and SS in plain clothes broke into the synagogue and destroyed the prayer room. Jews were mistreated, Jewish property was destroyed.

As everywhere in Germany, the Jews were discriminated against, so that many left the city or even the country. In 1938, 42 Jews were named in the city, at least 21 of whom were murdered in the Shoah .

The best-known National Socialists were the later lieutenant general of the Waffen-SS Ludolf von Alvensleben and the later SS-Standartenführer and camp commandant of the Majdanek concentration camp Hermann Florstedt .

In addition to political opponents, clergymen also resisted the Nazi regime, according to Pastor Johannes Noack from the Confessing Church , who was sentenced to prison for "state agitation", as a result of which he died in 1942. In the Second World War were 913 residents of the city.

Until the end of the war, the city remained almost untouched by the war, although it was in the midst of not insignificant mining and industrial operations. All schools and hospitals served as military hospitals for thousands of wounded soldiers. The American armed forces reached the town of Eisleben while bypassing the Harz fortress on April 13, 1945 and surrendered without a fight. Units of the 1st US Army immediately set up a prisoner-of-war camp on the north and east sides of the heap of the Hermannschacht near Helfta. German soldiers and civilians were interned in the open air on an area of around 80,000 m². At times there were 90,000 prisoners here, of whom 2,000 to 3,000 died, mainly from the inhuman conditions. The camp was disbanded on May 23, 1945, and the prisoners were taken to other cities. The remains of the deceased have not been found to this day. On May 20, 1995, a prisoner of war memorial was erected and inaugurated in Helfta in memory of these people.

post war period

On July 2, 1945, the Soviet army marched into Eisleben. Due to the 1st London Zone Protocol of 1944 and the decisions of the Yalta Conference , it became part of the Soviet zone of occupation . As a greeting, Eisleber communists put a Lenin monument on the plan. On August 1, 1945 - in front of a full house with 714 seats - the curtains of the Eisleben Citizens' Theater were raised; it was the first German post-war theater. It was founded and managed by Ralph Wiener , the pseudonym for Felix Ecke

In 1946, on the 400th anniversary of Martin Luther's death, the city was given the name "Lutherstadt". On March 22, 1949, more than 2,000 residents demonstrated for the unity of Germany. In 1950 Eisleben celebrated the 750th anniversary of the Mansfeld mining industry in the presence of the President of the GDR Wilhelm Pieck . The great circle created in 1950 was dissolved and the circles Eisleben and Hettstedt were formed. From 1951 the city area was expanded to include the Ernst-Thälmann-Siedlung and the Wilhelm-Pieck-Siedlung. In 1963, the progress shaft, the last copper slate shaft in Eisleben, was closed. The mining era in the Mansfeld Mulde finally came to an end by 1969. The Mansfeld Combine was transformed into a production facility for tools and consumer goods. At the same time, the mining and metallurgical engineering school was developed into an engineering school for electrical engineering and mechanical engineering.

In order to create space for a department store, the remaining keep of the old moated castle was blown up on the corner between Freistrasse and Schlossplatz . Between 1973 and 1975 subsidence occurred again in the urban area, especially in the area of the sieve heat. Prefabricated buildings with 640 apartments were built on Sonnenweg and the Old Cemetery.

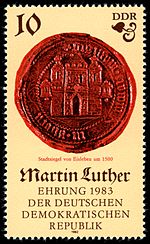

The celebration of Luther's 500th birthday in 1983 was long and lavishly prepared and celebrated with guests from 36 countries. The GDR Post Office (November 9, 1982 and October 18, 1983) and the Federal Post Office (October 13, 1983) issued special stamps on this occasion. The Luther sites had been restored and the facades of the houses on the market renewed.

In autumn 1989 demonstrations for democracy and social change took place in Eisleben as well. Eisleben has been part of the state of Saxony-Anhalt since German Unity Day on October 3, 1990. In 1994 the district of Hettstedt and the district of Eisleben were merged to form the district of Mansfelder Land with the Eisleben administrative center. The Luther houses have been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1997. In the course of the district reform in 2007, Eisleben lost its status as a district town to Sangerhausen.

On May 25, 2009, the city received the title “ Place of Diversity ” awarded by the federal government .

In 2016 Eisleben was awarded the honorary title of “ Reformation City of Europe ” by the Community of Protestant Churches in Europe .

Population development

The population has been decreasing continuously since the mid-1960s due to emigration and declining birth rates, although the urban area has been steadily enlarged by incorporations. The expiry of copper slate mining in the Mansfeld Mulde area at the end of the 1960s and its relocation to the Sangerhausen district played an important role.

|

|

as of December 31, except 1964–1981: census

Religions

In 2011, 10.8% of the ice liver belonged to the Evangelical Lutheran and 4.6% to the Roman Catholic Church .

- Roman Catholic (St. Gertrud, Helfta Monastery )

- Evangelical (St. Andreas - Nikolai - Petri-Pauli, St. Annen)

- Eisleben has been the seat of the superintendent of the Evangelical Church District Eisleben-Sömmerda since 2010 , which includes all Protestant parishes in the district of Mansfeld-Südharz and large parts of the Kyffhäuserkreis and the district of Sömmerda in Thuringia.

politics

City council

Eisleben's city council is composed of 35 councilors; In addition, the full-time mayor is a member of the city council. After the local elections on May 26, 2019 there are four parliamentary groups:

| Party / list | CDU , FDP | Left , PARTY | SPD , Greens , FFW, FBM | AfD | Bgm. | total |

| Seats | 13 | 8th | 8th | 6th | 1 | 36 (36 +1 ) |

Mayor

Jutta Fischer was elected mayor on March 26, 2006 as a non-party candidate of the SPD with 51% of the vote. From January 1, 2009, according to the amended Municipal Constitutional Act, she was allowed to bear the title of Lord Mayor. On December 2, 2012, she was re-elected in the second ballot with 64.0% of the vote and immediately afterwards asked to join the SPD. In the 2019 elections, the non-party candidate Carsten Staub, supported by the CDU, won. He received 67.6% in the runoff election and took office on April 27, 2020. Due to the drop in population to less than 25,000, he only bears the title of mayor.

coat of arms

| Blazon : "An open silver flight in blue ." | |

| Reasons for the coat of arms: The coat of arms reminds of the affiliation of the city of Eisleben to the county of Mansfeld . The two wings were the helmet decorations in the coat of arms of the Altmansfeld counts, which, together with the helmet, have appeared in the shield as the city coat of arms since the beginning of the 16th century . From the middle of the 17th century, the helmet with the wings was placed over the shield. In the shield itself only the two wings that are known to this day remain. |

flag

The approval of the flag of Lutherstadt Eisleben was granted on February 27, 2009 by the district.

The flag is blue-white (1: 1) striped (horizontal shape: stripes running horizontally, lengthways shape: stripes running vertically).

Town twinning

- Raismes , Nord department, France, since 1962

- Herne , North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany since 1990

- Memmingen , Bavaria, Germany since 1990

- Weinheim , Baden-Württemberg, Germany since 1990

Culture and sights

theatre

The Eisleben Theater was founded on July 13, 1945 as the first German post-war theater and has been operating as the State Theater of Saxony-Anhalt since 1990 . Due to a massive reduction in funding by the state of Saxony-Anhalt, which is linked to additional conditions, the Eisleben Theater will in future concentrate on cultural mediation as the Mansfeld-Südharz cultural work. At the end of 2018, the state government corrected the cuts in grants somewhat - probably also as a result of protests. For 2019 to 2023 there is a little more than five percent in money. In addition, the state assumes higher personnel costs insofar as they are caused by wage increases.

Museums

- Martin Luther's birthplace is a town house from the mid-15th century, in which Martin Luther was born on November 10, 1483. The city set up a memorial for Martin Luther and the Reformation there in 1693. This makes Luther's birthplace one of the oldest museums in German-speaking countries. In 1817, on the occasion of the 300th anniversary of the Reformation, a separate building was built on the adjacent site to house the Luther school. Both buildings have belonged to the Luther Memorials Foundation in Saxony-Anhalt since 1997 . In 2007 they were supplemented by a connecting building and an entrance building on the opposite side of the street.

- The Luther school, a foundation of the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III , belongs to the building complex of the birth house.

- Martin Luther's house where he died is a late Gothic patrician house and was built around 1500.

Churches

- St. Petri-Pauli is a three-aisled hall church and was first mentioned in a document in 1333. The tower in front of it was built in 1447–1513. The tower dome in its current form dates from 1562. Luther was baptized there on November 11, 1483, one day after his birth.

- The St. Andrew's Church is a late Gothic hall church with a three-aisled choir on a Romanesque previous building. Martin Luther gave his last four sermons there in 1546.

- St. Anne's Church , foundation stone laid in 1514, with Augustinian hermit monastery and rectory from 1670.

- St. Nicolai Church, first half of the 15th century

- The Old Gertrudiskirche was built in Eisleben in 1865 as the first Catholic church after the Reformation. After the church became too small, it was replaced by a new building on Klosterplatz. The old church was sold and used as a gym.

- The Catholic St. Gertrud Church, consecrated in 1916, is the replacement building for the Old Gertrudiskirche .

- Helfta Monastery

- The former synagogue in Eisleben was inaugurated in 1814 and rebuilt in 1850. It was desecrated in 1938. It has been restored since 2001.

graveyards

- The Kronenfriedhof , in the style of a Camposanto , was inaugurated in 1533 as a hereditary burial place for wealthy Eisleber families.

- The Soviet cemeteries are resting places for 124 prisoners of war and displaced civilians.

Monuments

The city's cultural monuments are in the list of cultural monuments in Lutherstadt Eisleben .

- The Luther monument was created by Rudolf Siemering in 1883 and is on the market square.

- The Lenin monument was created in 1926 by the Russian sculptor Matwei Maniser and was in Pushkin until 1942 . It was brought to Eisleben for metal extraction by the Wehrmacht, but it was not melted down. So it was able to be set up in a prominent place in Eisleben after the war. After the Peaceful Revolution, it was removed in 1991; after restoration, it is now on loan to the German Historical Museum in Berlin.

- The comrade Martin, also called "Bergmannsroland", is the symbol of the legal independence of the new from the old town of Eisleben. It can be assigned to the Roland statues in Saxony-Anhalt.

- The Carl-Eitz-Stein was erected in honor of the pedagogue and acoustician.

- The memorial trees are two rows of linden trees that were planted on March 17, 1864 for the 50th anniversary of the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig .

- The marathon runner (1911) by the sculptor Max Kruse is reminiscent of the teachers' seminar that was in Eisleben from 1826 to 1926.

- The gate of the warning in the city park was designed by the sculptor Richard Horn in memory of the victims of the First World War and inaugurated in 1932.

- The Friedrich Koenig monument commemorates the Eisleber inventor of the high-speed press Friedrich Koenig and was created in 1891 by the sculptor Fritz Schaper .

- The Ernst Leuschner Memorial was created in 1903 by the sculptor Carl Seffner in memory of the head of the mountain and hut, Ernst Leuschner (1826–1898) .

- According to the inscription Ante 1843 (= before 1843 ), the Plümicke -Stein surveying monument on the city terraces, formerly the mountain school garden, was possibly used as an adjustment table for the Markscheider training at the Eisleben mountain school.

Secular buildings

- The town hall in the old town was built between 1508 and 1532.

- City palace of the Mansfeld counts

- Count's Mint, Renaissance building

- The old grammar school was built between 1563 and 1564 as a "noble Latin school". After the city fire in 1601, it was rebuilt in 1604. The sacred song writer Martin Rinckart worked there from 1610 to 1611. In 1883 the now Royal Prussian High School moved to the new school building on Schlossplatz.

- The old superintendent was built on three floors at the beginning of the 16th century. Under Johannes Agricola , Magister Islebeius, it was a boys' school in 1525. In 1546, after the Luther Treaty, it was also known as the “Fürnehme Latinschule”. In 1601 a fire caused severe damage, but the remarkable late Gothic portal was preserved.

- Old scales

- Old Vicariate

- The old mountain school is a baroque building that originally housed the Katharinenstift hospital. From 1817 to 1844, the Eisleber mountain school, founded in 1798, was located in the house.

- The town hall of Neustadt (Eisleben) (Old Court) was built between 1571 and 1589.

- The Mohrenapotheke was set up in 1817 in the former supervisor's house in Saxony .

- Million dollar bridge

- The house of the manager of the Katharinenstiftgut was built in 1723 in baroque style with a magnificent gable, mansard roof and stucco house entrance.

- The district court of Eisleben was built in 1913.

Regular events

- The Eisleber Wiesenmarkt , the largest folk festival in Central Germany, takes place every third weekend in September and goes back to the approval by Emperor Charles V for holding a cattle and ox market in 1521. Furthermore, the spring meadow takes place every year.

- Culture night in the Helfta monastery

dialect

Lutherstadt Eisleben is located in an area in which the Mansfäller dialect is spoken. This border dialect between the Thuringian and Upper Saxon regions can also be heard with variations in the surrounding villages. The core town of Eisleben lies within Mansfeld in the dialect of actually Mansfeld . As a special feature, the vowels in the city are slightly purer than in the surrounding area. There used to be slightly different pronunciations in the individual districts of Eisleben. In particular, the dialects of the old town and the new town were distinguishable.

Characteristic for the real Mansfeld are u. a. the sound shifts from o to u ( Uhstern instead of Easter), ei to ä ( paths instead of legs), e to i ( they instead of very) and äu to ai ( baime instead of trees). In the literature, an example sentence of the actually Mansfeldian in Eisleben is mentioned: Jch here uff dean one ear jar niche me (I can no longer hear anything in one ear).

In the localities of Lutherstadt Eisleben, the real Mansfeld is also mainly at home. In contrast to the core city, however, there is a slightly coarser pronunciation. As early as 1886 it was noted that the dialect of the region was being increasingly falsified and forgotten.

The dialect has recently gained regional fame through the Eisleber comedy duo Elsterglanz , who perform skits in the city's dialect. Two movies have even been made.

Sports

- The Mansfelder SV Eisleben is a sports club from Lutherstadt Eisleben. The sports facility is the municipal sports field with a capacity of 5000 spectators, with two grass and one artificial turf and a covered grandstand.

- The KAV Mansfelder Land is a club from the city and competed in the 1st Wrestling League from 2013 to 2015.

Economy and Infrastructure

traffic

Road traffic

In Eisleben, the eastern section of federal highway 80 ends at the intersection with the B180 . In a westerly direction, the former B80 runs as the L151 via Sangerhausen to Nordhausen. Eisleben is affected by the federal highway 180 coming from the direction of Aschersleben / Hettstedt and leading to Querfurt / Naumburg . The junction "Eisleben" of the federal highway 38 is located south of the city .

Rail transport

At the town's train station, built in 1865 near Rathenaustraße, the RE9 / RE19 Halle – Leinefelde (–Kassel) and the RB75 Halle – Lutherstadt Eisleben stop every hour on the Halle – Kassel line . With a view to the Reformation anniversary in 2017, the building has been renovated since December 2015 by a private cooperative founded in 2013 . Whoever wants to become a member must pay a share of at least 200 euros. Additional funds come from the Sachsen-Anhalt local transport service , Abellio Rail Mitteldeutschland and the city. It is the only train station in Saxony-Anhalt to date that has been renovated by a cooperative.

Bus transport

The public transport system is, among other things by the PLUSBUS of the country's network of Saxony-Anhalt provided. The following connections lead from Lutherstadt Eisleben:

- Line 410: Lutherstadt Eisleben ↔ Volkstedt ↔ Siersleben ↔ Hettstedt ↔ Aschersleben

- Line 420: Lutherstadt Eisleben ↔ Benndorf ↔ Klostermansfeld ↔ Mansfeld ↔ Hettstedt

- Line 700: Lutherstadt Eisleben ↔ Bischofrode ↔ Rothenschirmbach ↔ Querfurt

The urban and regional bus transport is carried out by Verkehrsgesellschaft Südharz mbH. The city's central bus station, which was extensively rebuilt from 2013, is located on Klosterplatz.

Educational institutions

- Martin-Luther-Gymnasium Eisleben

- Katharinenschule (1960–1994 POS John Schehr)

- Thomas Müntzer School (primary school)

- Primary school on Schlossplatz

- Torgartenstrasse primary school

- Primary school Geschwister-Scholl

- Mansfeld-Südharz vocational school

Former educational institutions

- Royal Teachers' College

- Eisleben mountain school later Eisleben engineering school

- Gymnasium on Bergmannsallee (now part of the Martin Luther Gymnasium)

- Grave school (now part of the Katharinenschule)

- Secondary school at Rühlemannplatz

Personalities

literature

- Ursel Lauenroth: Lutherstadt Eisleben. Photo documents between 1945 and 1989 (= When the chimneys were still smoking. - At that time edition in our city ). Leipziger Verlagsgesellschaft, Verl. Für Kulturgeschichte und Kunst, Leipzig 2005, ISBN 3-910143-76-8 .

- Marion Ebruy, Klaus Foth: City guide Eisleben. A thousand-year-old city on foot. Mansfeld Heimatverein, Eisleben 2002, ISBN 3-00-010617-0 .

- Sabine Bree: Lutherstadt Eisleben. City-guide. Verlag Communication and Techniques, Thedinghausen 1996, ISBN 3-9804949-0-X .

- Burkhard Zemlin: City Guide Lutherstadt Eisleben. Photographs by Reinhard Feldrapp . Verlag Gondrom, Bindlach 1996, ISBN 3-8112-0833-0 .

- Gerlinde Schlenker (Red.): 1000 years of market, coin and customs law Lutherstadt Eisleben. Ed. By the city administration, Eisleben 1994, OCLC 180482314 .

- Hermann Großler : Documented history of Eisleben up to the end of the twelfth century (= Dingsda booklet ). Dingsda-Verlag, Querfurt 1992, ISBN 3-928498-17-7 (reprint [of the edition] Verlag der Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses, Halle 1875. Ed. By Joachim Jahns) ( limited preview in Google book search).

- Hermann Großler: From the individual courtyard to the urban district. A look at the development of the city of Eisleben (= Dingsda booklet ). Dingsda-Verlag, Querfurt 1992, ISBN 3-928498-18-5 (= reprint [of the edition] Hendel, Halle as 1910. Ed. By Joachim Jahns).

- Hermann Großler: How the City of Eisleben became. A contribution to local history. First to fifth parts (in one volume). Self-published by Ernst Schneider, Eisleben 1905.

- Individual impressions in the Mansfeld sheets. XIX. Vol (1905), OCLC 833398762 , pp. [1] -56; 2nd part, XX. Vol (1906), OCLC 833398775 , pp. [57] -134; 3rd part, XXI. (1907) OCLC 833398778 , pp. 136-180; 4th part, XXII. (1908) OCLC 833398791 , pp. 182-204; 5th part, XXIII. Vol. (1909) OCLC 833398795 , pp. 206-262.

Web links

- City administration website

- Link catalog on ice life at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

Individual evidence

- ↑ State Statistical Office Saxony-Anhalt, population of the municipalities - as of December 31, 2019 (PDF) (update) ( help ).

- ↑ German UNESCO Commission e. V .: World Heritage List. In: unesco.de, accessed on August 6, 2016.

- ^ Neckendorf. ( Memento from January 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) In: Homepage of Lutherstadt Eisleben.

- ↑ Oberhütte. ( Memento from September 26, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) In: Homepage of Lutherstadt Eisleben.

- ↑ Federal Statistical Office (Ed.): Municipalities 1994 and their changes since 01.01.1948 in the new federal states . Metzler-Poeschel, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8246-0321-7 .

- ↑ StBA: Changes in the municipalities in Germany, see 2004 (XLS; 224 kB; file is not accessible), accessed on August 8, 2016.

- ↑ StBA: Changes in the municipalities in Germany, see 2005 (XLS; 364 kB; file is not accessible), accessed on August 8, 2016.

- ↑ StBA: Changes in the municipalities of Germany, see 2006 (XLS; 95 kB; file is not accessible), accessed on August 8, 2016.

- ↑ StBA: Area changes on January 1 , 2009 , accessed on August 8, 2016.

- ↑ StBA: Area changes from January 1 to December 31, 2010 , accessed on August 8, 2016.

- ^ German Weather Service: normal period 1961–1990.

- ^ A b Kurt Lindner: Lutherstadt Eisleben. Center of the Mansfeld copper slate building. A historical overview from the first evidence of human settlement to the end of the 20th century. 3 volumes. Edited by the city council of Eisleben. Eisleben 1983 ff., DNB 551122048 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Marion Ebruy, Klaus Foth: Stadtführer Eisleben. A thousand-year-old city on foot. Edited by the Mansfelder Heimatverein e. V. Mansfelder Heimatverein, Eisleben 2002, ISBN 3-00-010617-0 .

- ↑ "and still has an alley to ice - [/] live, last [from] the name that it is called the Friesische Strasse Vicus Frisonum, by the common people the Freystrasse." Cyriacus Spangenberg : Mansfeldische Chronik. Andreas Petri, Wittenberg 1572, OCLC 257556940 , p. 223 a and b , the name itself p. 223 b , line 1 f. ( limited preview in Google Book Search); see. the mention in the division of inheritance of the Counts of Mansfeld 1420: p. 359 a , line 20 (chapter 310 [!]; limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Burkhard Zemlin: City Guide Lutherstadt Eisleben. Photographs by Reinhard Feldrapp. Gondrom Verlag, Bindlach 1996, ISBN 3-8112-0833-0 .

- ^ Brothers Grimm (ed.): German legends. Second part, Nicolaische Buchhandlung, Berlin 1818, OCLC 832242388 , p. 185 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ^ Hermann Großler (after Brothers Grimm): Legends of the county of Mansfeld and its immediate surroundings. Self-published by O. Mähnert, Eisleben 1880, OCLC 6820612 , p. 2 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ Bernd Feicke: The Counts of Mansfeld as lords of Eisleben. The pledge of the lower courts in 1454 to the city council. In: Harz-Zeitschrift. 61 (= 142), 2009, ISSN 0073-0882 , pp. 141-154.

- ^ Eckart Klaus Roloff : Luther, the savior. In: Rheinischer Merkur . No. 44/2007, p. 19 (cultural report about Eisleben).

- ^ Hermann Großler: The Becoming of the City of Eisleben. Part 5. In: Mansfeld leaves. (23) 1909, OCLC 833398795 , pp. 67-124, here: App. 1, pp. 119-122.

- ^ Thomas laundry: The water supply of the city of Eisleben. Of wells, tunnels and pipelines. T. Laundry, Eisleben 2002, DNB 965779734 ; 2nd Edition. Eisleben 2006. - Ders .: The fortifications of the city of Eisleben. An attempt at reconstruction. T. Laundry, Eisleben 2000, DNB 965871061 ; 2., completely revised Edition, Ed. B. Ibid. 2007, OCLC 1078726234 ; Through new imprint. 2010 ibid.

- ↑ Bernd Feicke: Blanckenberg, Berndinus. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 30, Bautz, Nordhausen 2009, ISBN 978-3-88309-478-6 , Sp. 124-130.

- ^ Thomas laundry: The shape of the city of Eisleben. Reconstruction of the structural condition from the beginning of the 15th century to the great city fire of 1601. T. Laundry, Eisleben 2007.

- ↑ Bernd Feicke: The permutation recesses at the end of the 16th century in the county of Mansfeld. In: Journal for local research. Issue 17. Halle 2008, pp. 19–24.

- ^ Walter Mück: The Mansfeld copper slate mining and its legal historical development. Volume 2: Document book of the Mansfeld mining industry. Self-published, Eisleben 1910, OCLC 174647726 , p. VIII Note 1 (reference to Hermann Brassert : Bergordnung der Preußischen Lande. Cologne 1858; with reference to the document 153 dealt with there, in which the Mansfeld Bergordnung. [October 28] 1673; limited preview in Google Book search), for the date cf. Pp. 344, 614.

- ↑ a b c The Counts of Mansfeld .

- ^ Birk Karsten Ecke: The Counts of Mansfeld and their rule ( Memento from June 24, 2019 in the Internet Archive ). In: harz-saale.de. December 9, 2012, accessed August 8, 2016.

- ^ Eisleben before the year 1000 ( memento from December 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on August 8, 2016; and Eisleben from 994 to the Reformation ( Memento from May 21, 2010 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on August 8, 2016.

-

^ Government districts of Dessau and Halle (= Handbook of German Art Monuments. Part: Saxony-Anhalt. Volume 2; [Dehio]). Arranged by Ute Bednarz. German Kunstverlag, Berlin / Munich 1999, ISBN 3-422-03065-4 , p. 467;

Bernd Feicke: On the political history of the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss circuit 1803 and its results for Saxony and Prussia in the eastern Harz with special reference to 1780 incorporated county Mansfeld ... In: Contributions to Regional us Landeskultur Saxony-Anhalt (conference on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the Imperial Diet-circuit at 12 April 2003 in Quedlinburg). Issue 29. Landesheimatbund Sachsen-Anhalt, Halle 2004, ISBN 3-928466-60-7 , pp. 4–29, here: pp. 6–14. - ↑ Stefan König: The potash cable car between Eisleben and Unterrißdorf ( Memento from August 8, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: kupferspuren.artwork-agentur.de, accessed August 8, 2016; originally: Association of Mansfeld Miners and Hutsmen e. V .: From the association's communications. Communication No. 92, 2/2008.

- ^ Förderverein Eisleber Synagoge e. V. In: synagoge-eisleben.de, accessed on August 8, 2016.

- ↑ Federal Archives : Memorial Book - Victims of Persecution of the Jews under the National Socialist Tyranny in Germany 1933–1945 . 2007; Here data for 24 Jewish residents of Eisleben: Search in the directory of names (search for place of residence Eisleben). In: bundesarchiv.de/gedenkbuch, as of February 28, 2020, accessed on May 29, 2017.

- ↑ The International Institute for Holocaust Research: Train rides into sinking. Database on the deportations during the Shoah (Holocaust). In: Yad Vashem . International Holocaust Memorial. The Holocaust Martyrs 'and Heroes' Remembrance Authority; here: search for personal names, place of residence: Eisleben. In: yadvashem.org, accessed August 8, 2016 (lists 15 people).

- ↑ Peter Lindner: Hermann Florstedt, SS leader and concentration camp commandant. An image of life in the family's horizon. Gursky, Halle (Saale) 1997, ISBN 3-929389-19-3 .

- ↑ Stefanie Endlich, Nora Goldenbogen, Beatrix Herlemann , Monika Kahl, Regina Scheer : Memorials for the victims of National Socialism. A documentation. Volume II: Federal states of Berlin, Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Saxony-Anhalt, Saxony, Thuringia. Edited by the Federal Agency for Civic Education . Bonn 1999, ISBN 3-89331-391-5 , p. 528 f.

- ↑ Birk Karsten Ecke: The prisoner-of-war camp at Helfta near Eisleben and the end of the Second World War in Eisleben ( memento from September 30, 2019 in the Internet Archive ). In: harz-saale.de. December 8, 2012, accessed August 8, 2016.

- ↑ Robby Zeitfuchs, Volker Schirmer: Zeitzeugen. The Harz in April 1945. R. Zeitfuchs / Verlag Books on Demand, Güntersberge 2000, ISBN 3-89811-654-9 .

- ^ Eckart Klaus Roloff : Luther, the savior. In: Rheinischer Merkur . No. 44, 2007, p. 19 (cultural report about Eisleben).

- ↑ Ralph Wiener : Small city, big. On the history of the first German post-war theater. Schäfer Druck & Verlag, Langenbogen 2007, ISBN 978-3-938642-21-4 .

- ↑ D. h. the former desert of Siebenhitze .

- ↑ City portrait in CPCE project site on Lutherstadt Eisleben: Lutherstadt Eisleben. Germany. "Hence I am". In: reformation-cities.org, accessed on October 6, 2017.

- ↑ State Statistical Office of Saxony-Anhalt: Lutherstadt Eisleben - District of Mansfeld-Südharz. Population status (since 1964) and population movements ( Memento from August 28, 2018 in the Internet Archive ). Updated: July 27, 2016. In: statistik.sachsen-anhalt.de, accessed on August 8, 2016.

- ↑ StBA: Changes in the municipalities of Germany, see 2007 (XLS; 369 kB; file is not accessible), accessed on August 8, 2016.

- ↑ Gerhard Knitzschke: the rise and fall of the Mansfeld Mont estate in the 19th and 20th centuries. (PDF; 805 kB) In: druckruckzuck.de. January 25, 2016, accessed on December 8, 2019 (version of September 3, 2017).

- ^ Database census 2011, Eisleben, Lutherstadt, age + gender.

- ↑ 2011 census. Population of the Eisleben community, Lutherstadt on May 9, 2011. Published by the State Statistical Office of Saxony-Anhalt, Halle (Saale) 2013, p. 9 ( statistik.sachsen-anhalt.de ( memento from April 2, 2018 on the Internet Archive ) [PDF; 581 kB; accessed on May 28, 2017]).

- ↑ a b State Statistical Office Saxony-Anhalt: Election results for the 2019 municipal council elections ( online [accessed on October 16, 2019]).

- ^ Members of the city council. In: eisleben.eu, accessed on October 16, 2019.

- ↑ State Statistical Office of Saxony-Anhalt: Elections to the Lord Mayor. Main and runoff election results ( memento of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). Updated: November 11, 2013. In: statistik.sachsen-anhalt.de, accessed on August 8, 2016.

- ↑ Wolfram Bahn, Ronald Dähnert: Jutta Fischer remains mayor. ( Memento from July 7, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) In: Mitteldeutsche Zeitung . December 2, 2012, accessed August 8, 2016.

- ↑ https://www.wochenspiegel-web.de/wisl_s-cms/_wochenspiegel/7399/Mansfelder_Land/62046/Neuer_Buergermeister_fuer_die_Lutherstadt_Eisleben.html

- ^ Official journal of the district ( Memento of February 24, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). No. 3/2009, p. 16 (PDF; 2.5 MB), accessed on August 8, 2016.

- ↑ Kulturwerk Mansfeld-Südharz: Goals. In: theater-eisleben.de. Archived from the original on March 24, 2016 ; accessed on February 24, 2016 .

- ↑ Hendrik Lasch: Roll backwards for the good. Saxony-Anhalt is softening earlier cuts in theaters. In: New Germany . 2nd / 3rd March 2019, p. 11.

- ↑ Our Mansfeld region. Heimatblatt for Eisleben and Hettstedt. January 1957, ZDB -ID 521691-6 , p. 3 ff.

- ↑ a b c House sign on the building.

- ↑ Torsten Hampel: If they, then who not? In: Der Tagesspiegel . October 12, 2013, accessed May 29, 2020.

- ↑ a b c d Richard Jecht : Limits and internal structure of the Mansfeld dialect: With a map. Pp. 11-13. Collection of the ULB Halle ( online ). Goerlitz 1986.

- ↑ Hendrik Lasch: Citizens prepare a large train station for Luther. A cooperative in Eisleben ensures that rail travelers are welcomed more dignified for the Reformation anniversary in 2017 than they are today. In: new Germany . 9/10 January 2016, p. 16.

- ↑ Detlef Liedmann: Bahnhofsgenossenschaft: Model from Lutherstadt is a model for other cities. In: MZ.de. November 15, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2018 .

- ↑ Ronald Dähnert: Eisleber Busbahnhof Renovation begins on Klosterplatz. In: MZ.de . February 26, 2013, accessed May 24, 2018 .