Michael Jordan

Editing of this article by new or unregistered users is currently disabled. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. If you cannot edit this article and you wish to make a change, you can submit an edit request, discuss changes on the talk page, request unprotection, log in, or create an account. |

| |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | February 17, 1963 Brooklyn, New York City |

| Nationality | USA |

| Listed height | 6 ft 6 in (1.98 m) |

| Listed weight | 216 lb (98 kg) |

| Career information | |

| College | North Carolina |

| NBA draft | 1984: 3rd overall |

| Selected by the Chicago Bulls | |

| Playing career | 1984–1993, 1995–1998, 2001–2003 |

| Position | Shooting guard |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| ACC Men's Basketball Player of the Year (1984) USBWA College Player of the Year(1984) Naismith College Player of the Year (1984) | |

| Stats at NBA.com | |

| Stats at Basketball-Reference.com | |

Michael Jeffrey Jordan (born February 17 1963) is a retired American professional basketball player. Widely considered one of the greatest basketball players of all time, he became one of the most effectively marketed athletes of his generation and was instrumental in popularizing the NBA (National Basketball Association) around the world in the 1980s and 1990s.

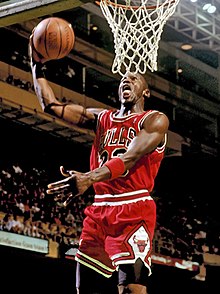

After a standout career at the University of North Carolina, Jordan joined the NBA's Chicago Bulls in 1984. He quickly emerged as one of the stars of the league, entertaining crowds with his prolific scoring. His leaping ability, illustrated by performing slam dunks from the foul line at Slam Dunk Contests, earned him the nicknames "Air Jordan" and "His Airness." He also gained a reputation as one of the best defensive players in basketball. In 1991, he won his first NBA championship with the Bulls, and followed that with titles in 1992 and 1993, securing a "three-peat". Though Jordan abruptly left the NBA in October 1993 to pursue a career in baseball, he rejoined the Bulls in 1995 and led them to three additional championships (1996, 1997, and 1998). His 1995–96 Bulls team won an NBA record 72 regular season games. Jordan retired for a second time in 1999, but he returned for two more NBA seasons as a member of the Washington Wizards from 2001 to 2003.

Jordan's individual accolades and accomplishments include five NBA MVP (Most Valuable Player) awards, ten All-NBA First Team designations, nine All-Defensive First Team honors, fourteen NBA All-Star game appearances, ten scoring titles, three stealing titles, and the 1988 NBA Defensive Player of the Year Award. He holds the NBA record for highest career regular season scoring average with 30.1 points per game, as well as averaging a record 33.4 points per game in the playoffs. In 1999, he was named the greatest North American athlete of the 20th century by ESPN, and was second to Babe Ruth on the Associated Press's list of athletes of the century.

Jordan is also noted for his product endorsements. He fueled the success of Nike's Air Jordan sneakers, which were introduced in 1985 and remain popular today. Jordan also starred in the 1996 feature film Space Jam. He is currently a part-owner and Managing Member of Basketball Operations of the Charlotte Bobcats, who reside in his home state of North Carolina.

Early years

Michael Jordan was born to James R. Jordan, Sr. and Deloris Jordan in Brooklyn, New York. His family moved to Wilmington, North Carolina, when he was seven years old.[1] Jordan attended Emsley A. Laney High School in Wilmington, where he anchored his athletic career by playing baseball, football, and basketball. He tried out for the varsity basketball team during his sophomore year, but at 5 feet 11 inches (1.80 m), he was deemed too short to play at that level. The following summer, however, he grew four inches (10 cm)[2] and trained rigorously. Upon earning a spot on the varsity roster, Jordan averaged 25 points per game over his final two seasons of high school play. As a senior, he was selected to the McDonald's All-American Team[3] after averaging a triple-double: 29.2 points, 11.6 rebounds, and 10.1 assists.[4]

In 1981, Jordan earned a basketball scholarship to the University of North Carolina, where he majored in cultural geography. As a freshman in coach Dean Smith's team-oriented system, he was named ACC Freshman of the Year as he averaged 13.4 points per game on 53.4% shooting.[5] Playing alongside All-American and future Hall of Famer James Worthy, Jordan was not initially a standout player for the North Carolina Tar Heels. However, he made the game-winning jump shot in the 1982 NCAA Championship game against Georgetown, which was led by future NBA rival Patrick Ewing.[2] Jordan later described this shot as the major turning point in his basketball career.[6] After winning the Naismith and the Wooden College Player of the Year Awards in 1984, Jordan left North Carolina one year before scheduled graduation to enter the 1984 NBA Draft. The Chicago Bulls selected Jordan with the third overall pick, after Hakeem Olajuwon (Houston Rockets) and Sam Bowie (Portland Trail Blazers). Jordan returned to North Carolina to complete his degree in 1986.[7]

Professional sports career

Early career

During his first season in the NBA,[2] Jordan averaged 28.2 points per game (ppg) on 51.5% shooting (field goal percentage).[5] He quickly became a fan favorite even in opposing arenas,[8][9][10] and appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated with the heading "A Star is Born" just over a month into his pro career.[11][12] Jordan was also voted in as an All-Star starter by the fans in his rookie season.[2] Controversy arose during the All-Star game when word surfaced that several veteran players, led by Isiah Thomas, were upset by the amount of attention Jordan was receiving. This led to a so called "freeze-out" on Jordan, where players refused to pass him the ball throughout the game.[2] The controversy left Jordan relatively unaffected when he returned to regular season play, and he would go on to be voted Rookie of the Year.[13] The Bulls finished the season 38-44,[14] and lost in the first round of the playoffs in four games to the Milwaukee Bucks.[13]

Jordan's second season was cut short by a broken foot which caused him to miss 64 games. Despite Jordan's injury and a 30–52 record,[14] the Bulls made the playoffs. Jordan recovered in time to participate in the playoffs and performed well upon his return. Against a 1985–86 Boston Celtics team that is often considered one of the greatest in NBA history,[15] Jordan put on a record-setting performance, scoring a playoff record 63 points in game 2.[16] The Celtics, however, managed to sweep the series.[13]

Jordan recovered completely by the 1986-87 season, and had one of the most prolific scoring seasons in NBA history. He became the only player other than Wilt Chamberlain to score 3,000 points in a season, averaging a league high 37.1 points on 48.2% shooting.[5] Despite his scoring success, Magic Johnson was awarded the league's Most Valuable Player. The Bulls reached 40 wins,[14] and advanced to the playoffs for the third consecutive year. However, they were again swept by the Celtics in three games.[13]

Mid-career: Pistons roadblock

Jordan led the league in scoring again in the 1987–88 season, averaging 35.0 ppg on 53.5% shooting,[5] and won his first league MVP award. He was also named the defensive player of the year, a rarity for a guard, as he averaged 1.6 blocks and a league high 3.16 steals per game.[17] The Bulls finished 50–32,[14] and made it past the first round of the playoffs for the first time in Jordan's career, as they defeated the Cleveland Cavaliers in five games.[18] However, the Bulls then lost in five games to the more experienced Detroit Pistons,[13] who were led by Isiah Thomas and a group of physical big men known as the "Bad Boys".

In the 1988-89 season, Jordan again led the league in scoring, averaging 32.5 ppg on 53.8% shooting from the field.[5] The Bulls finished with a 47–35 record,[14] and advanced to the Eastern Conference Finals, defeating the Knicks and Cavaliers along the way. The Cavaliers series contained a career highlight for Jordan when he hit a series winning shot over Craig Ehlo in the closing moments of the fifth and deciding game of the series. However the Pistons again defeated the Bulls, this time in six games,[13] by utilizing their "Jordan Rules" method of guarding Jordan, which consisted of double and triple teaming him every time he touched the ball.[2]

The Bulls entered the 1989-90 season as a team on the rise. With their core group of Jordan and young improving players like Scottie Pippen and Horace Grant, they were becoming a more cohesive team under the guidance of new coach Phil Jackson. Jordan averaged a league leading 33.6 ppg on 52.6% shooting,[5] and led the Bulls to a 55–27 record.[14] They again advanced to the Eastern Conference Finals beating the Bucks and Philadelphia 76ers en route. However, despite pushing the series to seven games, the Bulls lost to the Pistons for the third consecutive season.[13]

First three-peat

In the 1990–91 season, Jordan, motivated by the team's narrow defeat against the Pistons a year earlier, finally bought into Jackson and assistant coach Tex Winter's triangle offense after years of resistance.[19] That year, he won his second MVP award after averaging 31.5 ppg, 6.0 rebounds per game (rpg), and 5.5 assists per game (apg) for the regular season.[5] The Bulls finished in first place for the first time in 16 years and set a franchise record with 61 wins in the regular season.[14] With Scottie Pippen developing into an All-Star, the Bulls elevated their play to another level. The Bulls defeated the New York Knicks and the Philadelphia 76ers in the opening two rounds of the playoffs. They advanced to Eastern Conference Finals where their rival, the Detroit Pistons, awaited them. However, this time when the Pistons employed their "Jordan Rules" defense of doubling and triple teaming Jordan, he picked them apart with passing. Finally, the Bulls beat the Detroit Pistons in a surprising sweep.[20][21] In an unusual ending to the fourth and final game, Isaiah Thomas led the Pistons off the court when there was still time remaining on the clock, choosing to forfeit the game instead of shaking hands with the Bulls.[22]

The Bulls advanced to the NBA Finals where they beat Magic Johnson and the Los Angeles Lakers four games to one. The Bulls compiled an outstanding 15–2 record during the playoffs.[23] Perhaps the best known moment of the series came in Game 2 when, attempting a dunk, Jordan avoided a potential Sam Perkins block by switching the ball from his right hand to his left in mid-air to lay the shot in.[24] Jordan won his first NBA Finals MVP award unanimously,[25] and cried while holding the NBA Finals trophy.[26]

Jordan and the Bulls continued their dominance in the 1991–92 season, establishing a 67–15 record, the best in franchise history.[14] Jordan won his second consecutive MVP award with a 30.1/6.4/6.1 season.[17] After winning a physical 7-game series over the burgeoning New York Knicks in the second round of the playoffs and finishing off the Cleveland Cavaliers in the Conference Finals in 6 games, the Bulls met Clyde Drexler and the Portland Trail Blazers in the Finals. The media, hoping to recreate a Magic-Bird rivalry, highlighted the similarities between "Air" Jordan and Clyde "The Glide" during the pre-Finals hype. In the first game of the Finals, Jordan scored a Finals record 35 points in the first half, including a record matching six three-point field goals.[27] After the sixth three-pointer, he jogged down the court shrugging as he looked courtside. Marv Albert, who broadcast the game, later stated that it was as if Jordan was saying, "I can't believe I'm doing this."[28] The Bulls went on to win game one, and defeat the Blazers in six games. Jordan was named Finals MVP for the second year in a row [25] and finished the series averaging 35.8 ppg, 4.8 rpg, and 6.5 apg, while shooting 53% from the floor.[25] Drexler finished with averages of 24.8 ppg, 7.5 rpg, and 5.3 apg,[29] but only shot 41% from the floor.

In 1992-93, despite a 32.6/6.7/5.5 campaign,[17] Jordan's streak of consecutive MVP seasons ended as he lost the award to his friend Charles Barkley. Fittingly, Jordan and the Bulls met Barkley and his Phoenix Suns in the 1993 NBA Finals, in a match-up dubbed by the media as "Altitude vs. Attitude".[30] The Bulls captured their third consecutive NBA championship on a game-winning shot by John Paxson and a last-second block by Horace Grant, but Jordan was once again Chicago's catalyst. He averaged a Finals-record 41.0 ppg during the six-game series,[31] and became the first player in NBA history to win three straight Finals MVP awards.[25] With his third Finals triumph, Jordan capped off a seven-year run where he attained seven scoring titles and three championships, but there were signs that Jordan was tiring of his massive celebrity and all of the non-basketball hassles in his life.

Gambling controversy

During the Bulls' playoff run in 1993 controversy arose when Jordan was seen gambling in Atlantic City the night before a game against the New York Knicks.[32] In that same year he admitted to having to cover $57,000 in gambling losses,[33] and author Richard Esquinas wrote a book claiming he had won $1.25 million in gambling money from Jordan on the golf course.[33] In 2005 Jordan talked to Ed Bradley of the CBS evening show 60 Minutes about his gambling and admitted that he made some reckless decisions. Regarding his gambling Jordan stated, "Yeah, I’ve gotten myself into situations where I would not walk away and I’ve pushed the envelope. Is that compulsive? Yeah, it depends on how you look at it. If you’re willing to jeopardize your livelihood and your family, then yeah."[34] When Bradley asked him if his gambling ever got to the level where it jeopardized his livelihood or family Jordan replied, "No."[34]

First retirement

On October 6, 1993, Jordan announced his retirement, citing a loss in his desire to play the game. Jordan later stated that the murder of his father earlier in the year shaped his decision.[35] James R. Jordan, Sr. was murdered on July 23, 1993, at a highway rest area in Lumberton, North Carolina, by two teenagers, Daniel Green and Larry Martin Demery. The assailants were traced from calls they made on James Jordan's cellular phone,[36] caught, convicted and sentenced to life in prison. Jordan was very close to his father; he had observed his father's proclivity to stick out his tongue while absorbed in work, and adopted it as his own signature, which was on display each time he drove to the basket.[2] In 1998 Jordan founded a Chicago area Boys & Girls Club and dedicated it to his father.[37][38]

Those close to Jordan claimed that he had been considering retirement as early as the summer of 1992, and that the added exhaustion due to the Dream Team run in the 1992 Olympics solidified Jordan's burned-out feelings about the game and his ever-growing celebrity status. Jordan's announcement sent shock waves throughout the NBA and appeared on the front pages of newspapers around the world.[39]

Jordan then further surprised the sports world by signing a minor league baseball contract with the Chicago White Sox. He reported to spring training and was assigned to the team's minor league system on March 31, 1994.[40] Jordan has stated this decision was made to pursue the dream of his late father, who had always envisioned his son as a major league baseball player.[41] The White Sox were another team owned by Bulls owner Jerry Reinsdorf, who continued to honor Jordan's basketball contract during the years he played baseball.[42] He had an unspectacular professional baseball career for the Birmingham Barons, a Chicago White Sox farm team, batting .202 with 3 HR, 51 RBI, 30 SB (tied for fifth in Southern League), 11 errors and 6 assists.[40] He led the club with 11 bases loaded RBI and 25 RBI with runners in scoring position and two outs.[40] He also appeared for the Scottsdale Scorpions in the 1994 Arizona Fall League.

"I'm back": return to the NBA

In the 1993–94 season, the Jordan-less Bulls notched a 55–27 record,[14] and lost to the Knicks in the second round of the playoffs. But the 1994–95 version of the Bulls was a shell of the championship squad of just two years earlier. Struggling at mid-season to ensure a spot in the playoffs, Chicago needed a lift and it came in early 1995, when Michael Jordan called up Bulls guard B.J. Armstrong to go out for breakfast - a meal that led to an impromptu shoot-around, and eventually to Jordan's return to the NBA, playing for the Bulls.[43]

On March 18, 1995, Jordan announced his return to the NBA through a two-word press release: "I'm back."[2] The next day, Jordan donned jersey number 45 (his number with the Barons), as his familiar 23 had been retired in his honor following his first retirement. He took the court with the Bulls to face the Indiana Pacers in Indianapolis, scoring 19 points in a Bulls loss.[44]

Although Jordan had not played in an NBA game in a year and a half, he played well upon his return, which included a game-winning jump shot (against Atlanta in his fourth game back), and a 55-point game against the Knicks on March 29, 1995.[13] The Bulls made the playoffs and advanced to the Eastern Conference Semi-finals against the Orlando Magic. At the end of the first game of the series, Orlando's Nick Anderson commented that "[h]e didn't look like the old Michael Jordan,"[45] after which Jordan returned to wearing his old number (23). Jordan averaged 31.5 points per game in that series, but Orlando prevailed in six games.

Second three-peat

Freshly motivated by the playoff defeat, Jordan trained aggressively for the 1995–96 season. Strengthened by the addition of rebounder specialist Dennis Rodman, the Bulls dominated the league, starting the season 41–3,[46] and eventually finishing with the best regular season record in NBA history of 72–10. [47] Jordan led the league in scoring with 30.4 ppg,[48] and won the league's regular season and All-Star Game MVP awards.[2] In the playoffs, the Bulls lost only three games in four series, defeating the Seattle SuperSonics in the NBA Finals to win the championship. Jordan was named Finals MVP for a record fourth time,[25] surpassing Magic Johnson three Finals MVP awards.

In the 1996–97 season the Bulls started out 69-11, but narrowly missed out on a second consecutive 70 win season by losing their final two games to finish 69–13.[49] However, this year Jordan was bested by Karl Malone for the NBA MVP Award. The team again advanced to the Finals, where they faced Malone and the Utah Jazz. The series against the Jazz featured two of the more memorable clutch moments of Jordan's career. He won Game 1 for the Bulls with a buzzer-beating jump shot. In Game 5, with the series tied 2–2, Jordan played despite being feverish and dehydrated from a stomach virus. In what is known as the "flu game", Jordan scored 38 points including the game-deciding three-pointer with less than a minute remaining.[50] The Bulls won 90-88 and went on to win the series in six games.[49] For the fifth time in as many Finals appearances, Jordan received the Finals MVP award.[25]

Jordan and the Bulls compiled a 62–20 record in the 1997–98 season.[14] Jordan led the league with 28.7 points per game,[17] securing his fifth regular-season MVP award, plus honors for All-NBA First Team, First Defensive Team and the All-Star Game MVP.[2] The Bulls captured the Eastern Conference Championship for a third straight season and moved on to once again face the Jazz in the Finals.

The Bulls returned to Utah for game 6 on June 14, 1998 leading the series 3-2. In Game 6, Jordan executed a series of plays, considered to be one of the greatest clutch performance in NBA Finals history.[51] With the Bulls trailing 86-83 with 40 seconds remaining, coach Jackson called a timeout. Jordan received the inbounds pass, drove to the basket, and hit a layup over several Jazz defenders.[51] The Jazz brought the ball upcourt and passed the ball to forward Karl Malone, who was set up in the low post and was being guarded by Rodman. Malone jostled with Rodman and caught the pass, but Jordan cut behind him and swatted the ball out of his hands for a steal.[51] Jordan then slowly dribbled upcourt and paused at the top of the key, eying his defender, Jazz guard Bryon Russell. With fewer than 10 seconds remaining, Jordan started to dribble right, crossed over to his left and as Russell slipped, Jordan released a shot that would be rebroadcast innumerable times in years to come. As the shot found the net, announcer Bob Costas shouted "Chicago with the lead!"[52] After a desperation three-point shot by John Stockton missed, Jordan and the Bulls claimed their sixth NBA championship, and secured a second three-peat. Once again, Jordan was voted the Finals' MVP,[25] having led all scorers by averaging more than 30 points per game, including 45 in the deciding Game 6.[53] Jordan's six Finals MVPs is a record; Shaquille O'Neal, Magic Johnson, and Tim Duncan are tied for second place with three apiece.

Second retirement

Jordan's Game 6 performance seemed to be a perfect ending to his career. With Phil Jackson's contract expiring, the pending departures of Scottie Pippen (who stated his desire to be traded during the season) and Dennis Rodman (who would sign with the Los Angeles Lakers as a free agent) looming, and being in the latter stages of an owner-induced lockout of NBA players, Jordan retired for the second time on January 13, 1999.

On January 19, 2000, Jordan returned to the NBA not as a player, but as part owner and President of Basketball Operations for the Washington Wizards.[54] His responsibilities with the club were to be comprehensive, as he was in charge of all aspects of the team, including personnel decisions. Opinions of Jordan as a basketball executive were mixed.[55][56] He managed to purge the team of several highly-paid, unpopular players (such as, forward Juwan Howard and point guard Rod Strickland),[57][58] but many feel his lasting legacy as GM of the Wizards will be his selection of high school prospect Kwame Brown with the first pick in the 2001 NBA Draft, a player who has not lived up to expectations.[55][59]

Despite his January 1999 claim that he was "99.9% certain" that he would never play another NBA game,[60] in summer of 2001 Jordan expressed interest in making another comeback, this time with his new team. Inspired by the comeback of NHL star (and Jordan's friend) Mario Lemieux the previous winter,[61] Jordan spent much of the spring and summer of 2001 in training, holding several invitation-only camps for NBA players in Chicago. In addition, Jordan hired his old Chicago Bulls head coach, Doug Collins, as Washington's coach for the upcoming season, a decision that many saw as foreshadowing another Jordan return.

Washington Wizards comeback

On September 25, 2001 Jordan announced his return to professional play with the Wizards, indicating his intention to donate his salary as a player to a relief effort for the victims of the September 11, 2001 attacks.[62][63] In an injury-plagued 2001–02 season, he led the team in scoring (22.9 ppg), assists (5.2 apg), and steals (1.42 spg).[2] However, injuries ended Jordan's season after only 60 games, the fewest he had played in a regular season since a broken foot cut short his season in 1985–86.[5]

Playing in his 14th and final NBA All-Star Game in 2003, Jordan passed Kareem Abdul-Jabbar as the all-time leading scorer in All-Star game history. That year, Jordan was the only Washington player to play in all 82 games, starting in 67 of them. He averaged 20.0 points, 6.1 rebounds, 3.8 assists, and 1.5 steals per game.[2] He also shot 45% from the field, and 82% from the free throw line.[2] Even though he turned 40 during the season, he scored 20 or more points 42 times, 30 or more points nine times, and 40 or more points three times.[13] On February 21, 2003, Jordan became the first 40-year-old to tally 40 points in an NBA game. [64] During his stint with the Wizards, all Jordan home games at the MCI Center and nearly all his road games, were sold out and Wizards were the most-watched team in the NBA, averaging 20,173 fans a game at home and 19,311 on the road. However, neither of Jordan's final two seasons resulted in a playoff appearance for the Wizards, and Jordan was often unsatisfied with the play of those around him.[65][66] At several points he openly criticized his teammates to the media, citing their lack of focus and intensity.[65][66]

With the recognition that 2002-03 would be Jordan's final season, tributes were paid to him in nearly every arena in the NBA. In his final game at his old home court, the United Center in Chicago, Jordan received a prolonged standing ovation. The Miami Heat retired the #23 jersey on April 11, 2003, even though he never played for the team.[67] At the 2003 All-Star Game, Vince Carter gave up his starting spot at shooting guard to Jordan, and the halftime ceremony was dedicated to Jordan's career. Jordan's final NBA game was on April 16, 2003 in Philadelphia. Having sat out for much of the fourth quarter, Jordan re-entered the game in the final minutes, after the Philadelphia crowd started chanting "We want Mike!" with 1:44 remaining. Jordan sank his last two free throws, and then exited to a standing ovation.[68]

Olympic career

| Olympic medal record | ||

|---|---|---|

| Men's basketball | ||

| 1984 Los Angeles | Team | |

| 1992 Barcelona | Team | |

Jordan played on two Olympic gold medal-winning American basketball teams. As a college player he participated, and won the gold, in the 1984 Summer Olympics. Jordan led the team in scoring averaging 17.1 ppg for the tournament.[69] In the 1992 Summer Olympics he was a member of the star-studded squad that included Magic Johnson, Larry Bird, and David Robinson and was dubbed the "Dream Team". Playing limited minutes due to the frequent blowouts, Jordan averaged 12.7 ppg, finishing fourth on the team in scoring.[70] The team cruised to the gold medal, restoring America to the top of the basketball world. Jordan, Ewing and fellow Dream Team member Chris Mullin are the only American men's basketball players to win Olympic gold as amateurs (all in 1984) and professionals.

After retiring as a player

After his third retirement, Jordan assumed that he would be able to return to his front office position of Director of Basketball Operations with the Wizards. However, his previous tenure in the Wizards' front office had produced the aforementioned mixed results and may have also influenced the trade of Richard "Rip" Hamilton for Jerry Stackhouse (although Jordan was not technically Director of Basketball Operations in 2002).[55] On May 7, 2003, Wizards owner Abe Pollin fired Jordan as Washington's president of basketball operations.[55] Jordan later stated that he felt betrayed by the situation, and that if he knew he would be fired upon retiring he never would have come back to play for the Wizards.[34]

Jordan kept busy over the next few years by staying in shape, playing golf in celebrity charity tournaments, spending time with his family in Chicago, promoting his Jordan Brand clothing line, and riding motorcycles.[71] Since 2004, Jordan has owned a professional closed-course motorcycle roadracing team that competes in the premier Superbike class sanctioned by the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA).[72] On June 15, 2006, Jordan became a part-owner of the Charlotte Bobcats and was named "Managing Member of Basketball Operations." He is the largest individual owner of the team after majority owner Robert L. Johnson.[73] Despite Jordan's previous success as an endorser, he has made a conscious effort to not be included in the teams' marketing campaigns while with Charlotte.[74]

Player profile

Jordan was a shooting guard who was also capable of playing small forward. Jordan was known throughout his career for being a clutch performer. He decided numerous games with last-second plays (e.g. The Shot) and performed well under adverse circumstances (e.g. Flu Game). His competitiveness was visible in his prolific trash-talk,[75][76] and his solid work ethic.[77][78]

Jordan featured a versatile offensive game, he was capable of aggressively slashing to the basket and drawing fouls from his opponents at a high rate; his 8,772 free throw attempts are 9th all time.[79] Jordan could also post up his opponents and score with his trademark fadeaway jumpshot that used his jumping ability to "fade away" from block attempts. According to Hubie Brown, this move alone made him nearly unstoppable.[80] Jordan's 5.2 assists per game[5] indicate his willingness to defer to his teammates. In later years, he extended his shooting range to become a three-point threat, rising from a low 9 / 52 rate (.173) in his rookie year into a stellar 111 / 260 (.427) shooter in the 1996-97 season.[5] Jordan was also a good rebounder (6.2 per game)[5] for a guard.

On defense, Jordan's contributions were equally impressive. His 2,514 steals are second all-time behind John Stockton.[81] In addition he set records for blocked shots by a guard,[82] and combined this with his ball-thieving ability to become a standout defensive player. Jerry West often stated that he was more impressed with Jordan's defensive contributions than his offensive ones.[83]

Legacy

- "By acclamation, Michael Jordan is the greatest basketball player of all time."

- —introductory line of Jordan's nba.com/history biography[2]

- "There's Michael Jordan and then there is the rest of us."

Michael Jordan's basketball talent was clear from his rookie season.[8][10] In his first game in Madison Square Garden against the New York Knicks, Jordan received a prolonged standing ovation, a rarity for a player in an opposing team's arena.[10] After Jordan scored a playoff-record 63 points against the Boston Celtics in 1986, Celtics star Larry Bird described him as "God disguised as Michael Jordan."[16]

Jordan led the NBA in scoring in 10 seasons and tied Wilt Chamberlain's record of seven consecutive scoring titles. He was also a fixture on the NBA All-Defensive Team, making the roster nine times. Jordan also holds the top career and playoff scoring averages of 30.1 and 33.4 points per game,[2] respectively. By 1998, the season of his Finals-winning shot against the Jazz, he was well known throughout the league as a clutch performer. In the regular season, Jordan was the Bulls' primary threat in the final seconds of a close game and in the playoffs, Jordan would always demand the ball at crunch time. Jordan's total of 5,987 points in the playoffs is the highest in NBA history.[84] He retired with 32,292 points,[85] placing him third on the NBA's all-time scoring list behind Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Karl Malone.[85]

With five regular-season MVPs, six Finals MVPs, and three All-Star MVPs, Jordan is perhaps the most decorated player ever to play in the NBA. Jordan finished among the top three in regular-season MVP voting a record 10 times, and was named one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History in 1996.

Many of Jordan's contemporaries label Jordan as the greatest men's professional basketball player of all time.[83] An ESPN survey of journalists, athletes and other sports figures ranked Jordan the greatest North American athlete of the 20th century, above icons such as Babe Ruth and Muhammad Ali.[86] Jordan placed second to Babe Ruth in the Associated Press's list of 20th century athletes.[87] Jordan has also appeared on the front cover of Sports Illustrated a record 49 times.[88]

Jordan's athletic leaping ability, highlighted in his back-to-back slam dunk contest championships in 1987 and 1988, is credited by many with having influenced a generation of young players.[89][90][91] Several current NBA All-Stars have stated that they considered Jordan their role model while growing up, including Lebron James,[92] and Dwyane Wade.[93] In addition, commentators have dubbed a number of next-generation players "the next Michael Jordan" upon their entry to the NBA, including Grant Hill, Kobe Bryant, LeBron James, Vince Carter, and Dwyane Wade.[94][95][96] Although Jordan was a well-rounded player, his "Air Jordan" image is also often credited with inadvertently decreasing the jump shooting skills, defense, and fundamentals of young players.[90] A fact which Jordan himself has lamented in the past, "I think it was the exposure of Michael Jordan; the marketing of Michael Jordan. Everything was marketed towards the things that people wanted to see, which was scoring and dunking. That Michael Jordan still played defense and an all-around game, but it was never really publicized."[90] Although Jordan has done much to increase the status of the game, some of his impact on the game's popularity in America appears to be fleeting.[97][98] Television ratings in particular appeared to increase only during his time in the league and have subsequently lowered each time he left the game.[97][98]

Personal life

Jordan is the fourth of five children. He has two older brothers, Larry Jordan and James R. Jordan, Jr., one older sister, Deloris, and a younger sister, Roslyn. Jordan's brother James R. Jordan, Jr. retired as the Command Sergeant Major of the 35th Signal Brigade of the XVIII Airborne Corps in the U.S. Army.[99] He married Juanita Jordan in September 1989, and they have two sons, Jeffrey Michael and Marcus James, and a daughter, Jasmine. Michael and Juanita filed for divorce on January 4 2002, citing irreconcilable differences, but reconciled shortly thereafter. They filed for divorce again on December 29 2006 commenting that the decision was made "mutually and amicably".[100][101]

On July 21, 2006, a Cook County, Illinois judge determined that Jordan did not owe a former lover, Karla Knafel, $5 million.[102] Knafel claimed Jordan promised her that amount for remaining silent and agreeing not to file a paternity suit after Knafel learned she was pregnant in 1991. A DNA test showed Jordan was not the father of the child.[102]

As of 2007, Jordan lives in Highland Park, Illinois,[100] and both of his sons attend Loyola Academy, a private Roman Catholic high school located in Wilmette, Illinois.[103] Jeffrey is a member of the 2007 Graduating Class, while Marcus is a member of the 2009 class.

Media figure and business interests

Jordan is one of the most marketed sports figures in history. He has been a major spokesman for such brands as Nike, Coca-Cola, Chevrolet, Gatorade, McDonald's, Ball Park Franks, Rayovac, Wheaties, Hanes, and MCI.[104] Jordan has had a long relationship with Gatorade, appearing in over 20 commercials for the company since 1991, including the "Like Mike" commercials in which a song was sung by children wishing to be like Jordan.[104][105]

Nike created a signature shoe for him, called the Air Jordan. One of Jordan's more popular commercials for the shoe involved Spike Lee playing the part of Mars Blackmon. In the commercials Lee, as Blackmon, attempted to find the source of Jordan's abilities and became convinced that "it's gotta be the shoes."[104] The hype and demand for the shoes even brought on a spate of "shoe-jackings" where people were robbed of their sneakers at gunpoint. Subsequently Nike spun off the Jordan line into its own company named appropriately the "Jordan Brand." The company features an impressive list of athletes and celebrities as endorsers.[106][107] The brand has also sponsored college sports programs such as those of North Carolina, Cincinnati, Cal, St. John's, Georgetown, and North Carolina A & T.

Jordan also has been connected with the Looney Tunes cartoon characters. A Nike commercial shown during the 1993 Super Bowl XXVII featured Jordan and Bugs Bunny playing basketball against a group of Martian characters. The Super Bowl commercial inspired the 1996 live action/animated movie Space Jam, which starred Michael and Bugs in a fictional story set during his first retirement. They have subsequently appeared together in several commercials for MCI.

Jordan's income from the endorsements is estimated to be several hundred million dollars. In addition, when Jordan's power at the ticket gates was at its highest point the Bulls regularly sold out every game they played in, whether home or away.[108] Due to this, Jordan set records in player salary by signing annual contracts worth in excess of $30 million US dollars per season.[109]

Career achievements

Jordan won numerous awards and set many records during his career. The following are some of his achievements:[2][110][111]

Awards

- 14 time All-Star

- Olympic Gold Medal Winner—1984, 1992

- Five time MVP—1988, 1991, 1992, 1996, 1998

- Rookie of the Year—1984

- Defensive Player of the Year—1988

- 11 times All-NBA—10 times first team, 1 time second team

- Sports Illustrated "Sportsman of the Year"—1991

- Named one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History in 1996

Records

- Most scoring titles—10

- Highest career scoring average—30.1

- Highest career scoring average playoffs—33.4

- Most consecutive games scoring in double figures—866

- Highest single series scoring average NBA Finals—41.0 (1993)

- Most NBA Finals MVP awards (6)

See also

References

- ^ Sachare, Alex. The Chicago Bulls Encyclopedia. Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1999. p. 172-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Michael Jordan, nba.com/history, accessed January 15, 2007.

- ^ Williams, Lena. PLUS: BASKETBALL; "A McDonald's Game For Girls, Too", The New York Times, December 7, 2001, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Sportscenter, ESPN, air date February 2, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Michael Jordan entry, databasebasketball.com, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ qtd. in Lazenby, Roland. "Michelangelo: Portrait of a Champion." Michael Jordan: The Ultimate Career Tribute. Bannockburn, IL: H&S Media, 1999. p. 128.

- ^ Michael Jordan, britannica.com, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ a b Gross, Jane. "Jordan Makes People Wonder: Is He the New Dr. J?", The New York Times, October 21, 1984, accessed March 7, 2007.

- ^ Goldpaper, Sam. "Jordan dazzles crowd at Garden", The New York Times, October 19, 1984, accessed March 7, 2007

- ^ a b c Johnson, Roy S. "Jordan-Led Bulls Romp Before 19,252", The New York Times, November 9, 1984, accessed March 7, 2007.

- ^ SI cover search December 10, 1984, sportsillustrated.com, accessed March 9, 2007.

- ^ Chicago Bulls 1984-85 Game Log and Scores, databasebasketball.com, accessed March 10, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Michael Jordan bio, nba.com, accessed January 20, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chicago Bulls, databasebasketball.com, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Top 10 Teams in NBA History, nba.com/history, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ a b God Disguised as Michael Jordan, nba.com/history, accessed January 17, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Michael Jordan statistics, nba.com/history, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Chicago Bulls 1987-88 Game Log and Scores, databasebasketball.com, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Early NBA career, allmichaeljordan.com, accessed 8 March, 2007.

- ^ Chicago Bulls 1990-91 Game Log and Scores, databasebasketball.com, accessed March 7, 2007

- ^ Brown, Clifton. BASKETBALL; "Bulls Brush Aside Pistons for Eastern Title", The New York Times, May 28, 1991, accessed March 8, 2007

- ^ Isiah Thomas: Leader of the Bad Boys, nba.com, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Chicago Bulls 1990–91 Game Log and Scores, databasebasketball.com, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Wilbon, Michael. Great Shot! Jordan's Best Amazingly Goes One Better, Washington Post, June 7, 1991, accessed March 7, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g Finals Most Valuable Player, nba.com/history, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Schwartz, Larry [1], espn.com, accessed March 9, 2007

- ^ Jordan Blazes Away From Long Range, nba.com, accessed March 9, 2007.

- ^ A Stroll Down Memory Lane, nba.com/history, accessed February 23, 2007.

- ^ Clyde Drexler bio, nba.com, accessed February 10, 2007.

- ^ Michael Jordan/Charles Barkley "Attitude vs. Altitude" - Nike Inc. 1993, sportsposterwarehouse.com, accessed January 15, 2007.

- ^ Paxson's Trey Propels Bulls Into NBA History, nba.com/history, accessed January 20, 2007.

- ^ Anderson, Dave. "Sports of The Times; Jordan's Atlantic City Caper", The New York Times, May 27, 1993, accessed March 5, 2007

- ^ a b Thomas, Monifa. "Jordan on gambling: 'Very embarrassing'", Chicago Sun-Times, October 21, 2005, accessed January 17, 2007.

- ^ a b c Michael Jordan Still Flying High, cbsnews.com, August 20, 2006, accessed January 15, 2007.

- ^ Berkow, Ira. "A Humbled Jordan Learns New Truths", The New York Times, April 11, 1994, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Mitchell, Alison. THE NATION; "So Many Criminals Trip Themselves Up", The New York Times, August 22, 1993, accessed February 24, 2007.

- ^ Walsh, Edward. "On the City's West Side, Jordan's Legacy Is Hope", Washington Post, January 14, 1998, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Michael Jordan, family attend groundbreaking ceremony for James Jordan Center, Jet Magazine, April 14, 1995, available at findarticles.com, accessed January 15, 2007.

- ^ Thompson, Ian and Ted Rodgers. Europe loses a role model; even in countries where basketball is a minor pursuit, Jordan;s profile looms large - includes related article on Jordan's stature in Japan, The Sporting News, October 18, 1983, available at findarticles.com, accessed March 7, 2007.

- ^ a b c Birmingham Barons career, mjordan23.com, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Michael Jordan A Tribute, sportillustrated.cnn.com, accessed March 7, 2007

- ^ Araton, Harvey. BASKETBALL; "Jordan Keeping the Basketball World in Suspense", The New York Times, accessed March 8, 2007

- ^ A short trip through Michael Jordan's life, max23.de, acccessed March 15, 2007.

- ^ "Michael Jordan returns to Bulls in overtime loss to Indiana Pacers - Chicago Bulls", Jet Magazine, April 3, 1995, available on findarticles.com, accessed January 15, 2007.

- ^ Lawrence, Mitch. Memories of MJ's first two acts, espn.com, September 10, 1999, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Chicago Bulls 1995-96 Game Log and Scores, databasebasketball.com, accessed January 20, 2007.

- ^ Top 10 Teams in NBA History, nba.com/history, accessed 6 March 2007.

- ^ 1995-96 Chicago Bulls, nba.com/history, accessed January 15, 2007.

- ^ a b Chicago Bulls 1996-97 Game Log and Scores, databasebasketball.com, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Burns, Marty. 23 to remember, sportsillustrated.cnn.com, January 16, 1999, accessed February 23, 2007.

- ^ a b c Greatest Finals Moments, nba.com, accessed February 6, 2007.

- ^ The Jordan Phenomenon, pbs.org, June 15, 1998, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Ryan, Jeff. History of the NBA Finals Chicago Bulls vs. Utah Jazz - 1998, hollywoodsportsbook.com, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard, Jordan Sheds Uniform for Suit as a Wizards Owner, January 20, 2000, accessed March 11, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Pollin's decision to cut ties leaves Jordan livid, espn.com, May 7, 2003, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Brady, Erik. "Wizards show Jordan the door", usatoday.com, May 7, 2003, accessed February 23, 2007.

- ^ Associated Press. Making his move, sportsillustrated.cnn.com, February 22, 2001, accessed February 23, 2007.

- ^ Matthews, Marcus. Losing never looked so good for Wizards, usatoday.com, March 1, 2001, accessed February 23, 2007.

- ^ Wilbon, Michael. "So Long, Kwame, Thanks for Nothing+, The Washington Post, July 16, 2005, accessed February 23, 2007.

- ^ Schwartz, Larry. Michael Jordan transcends hoops, espn.com, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Associated Press. Jordan watched Lemieux's comeback very closely, espn.go.com, October 2, 2001, accessed March 7, 2007

- ^ Pollin Establishes Education Fund, nba.com, September 9, 2002, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ News Summary, The New York Times, September 26, 2001, accessed March 7, 2007.

- ^ Jordan Pours in History-Making 43, nba.com, February 21, 2003, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ a b Maaddi, Rob. Collins feels Jordan's pain, The Associated Press, November 29, 2001, accessed March 11, 2007.

- ^ a b Associated Press. Bad chemistry left MJ unable to win in Washington, April 2, 2003, accessed March 11, 2007.

- ^ Retire Jordan's 23, sportsillustrated.cnn.com, April 11th, 2003, accessed March 8th, 2007.

- ^ Sixers Prevail in Jordan's Final Game, nba.com, April 16, 2003, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Games of the XXIIIrd Olympiad -- 1984, usabasketball.com, accessed March 12, 2007.

- ^ Dupree, David. Is this U.S. roster the new Dream Team?, USA Today, August 18, 2006, accessed March 11, 2007.

- ^ Grass, Ray. "Michael Jordan is now riding superbikes", deseretnews.com, June 22, 2006, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Clarke, Dorina. AMA SB: Michael Jordan's Team, motorcycle-usa.com, March 5, 2004, accessed February 26, 2007.

- ^ Michael Jordan to Become Part Owner of the Charlotte Bobcats, nba.com, June 15, 2006, accessed January 15, 2007.

- ^ Associated Press. Jordan writes state of Bobcats letter to fans, espn.com, June 15, 2006, accessed February 21, 2007.

- ^ DeCourcy, Mike. "A suspension for talking trash? Mamma mia!" sportingnews.com, July 21, 2006, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Zillgitt, Jeff. "Pregame talk amounts to taking out the trash", usatoday.com, February 2, 2006, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Jackson, Phil. "Michael and Me", Inside Stuff, June/July 1998, available at nba.com, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Donnelly, Sally B. "Great Leapin' Lizards! Michael Jordan Can't Actually Fly, But", Time Magazine, January 9, 1989, accessed March 7, 2007.

- ^ Career Leaders for Free Throw Attempts, basketball-reference.com, January 16, 2007.

- ^ Brown, Hubie. Hubie Brown on Jordan, nba.com, accessed January 15, 2007 .

- ^ Career Leaders for Steals, basketball-reference.com, accessed February 23, 2007.

- ^ What Does He Do for an Encore?, Hoop Magazine, December 1987, available at nba.com, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ a b Michael Jordan: A tribute: Praise from his peers, NBA's 50 greatest sing MJ's praises, sportsillustrated.cnn.com, February 1, 1999, accessed January 15, 2007.

- ^ All-Time Playoffs Individual Career Leaders, nba.com, accessed 5 March 2007.

- ^ a b Career Points, databasebasketball.com, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Top N. American athletes of the century, espn.com, accessed March 15, 2007.

- ^ Associated Press, Top 100 athletes of the 20th century, USA Today, December 21, 1999, accessed March 15, 2007.

- ^ Gagliano, Rick. Magazine of the Week Sports Illustrated, dtmagazine.com, November 28, 1983, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Michael Jordan, encarta.msn.com, accessed March 6, 2007

- ^ a b c Hubbard, Jan. Michael Jordan interview, Hoop Magazine, April 1997, via nba.com, accessed March 6, 2007

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Curry. "In An Orbit All His Own", Sports Illustrated, November 9, 1987, accessed March 6, 2007

- ^ James says he'll decide his future soon, Associated Press, April 16, 2003.

- ^ Steve Ginsbrug, Wade scoffs at Jordan comparisons, Reuters, June 21, 2006.

- ^ Stein, Mark. Kobe, Hill deal with being the next Michael, espn.com, October 29, 2001, accessed March 6, 2007

- ^ Isidore, Chris. The next 'next Jordan', money.cnn.com, June 23, 2006, accessed March 6, 2007

- ^ Araton, Harvey. "Sports of The Times; Will James Be the Next Jordan or the Next Carter?" The New York Times, December 28, 2005, accessed March 6, 2007

- ^ a b Rovell, Darren. NBA could cash in if TV ratings soar with Jordan, espn.com, September 23, 2001, accessed March 10, 2007.

- ^ a b Lewis Helfand, The NBA After Jordan: Is There Hope? , askmen.com, accessed March 10, 2007.

- ^ Michael Jordan's big brother ends Army career, freerepublic.com, May 16, 2006, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ a b Associated Press. Jordan, wife end marriage 'mutually, amicably', espn.com, December 30, 2006, accessed January 15, 2007.

- ^ Michael Jordan, Wife to Divorce After 17 Years, people.com, December 30, 2006, accessed January 15, 2007.

- ^ a b Associated Press. "Judge says Jordan not obligated to pay ex-lover", usatoday.com, June 12, 2003, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Associated Press. Heir Jordan out to prove he can play like Mike, msnbc.com, July 9, 2005, accessed January 15, 2007.

- ^ a b c Rovell, Darren. "Jordan's 10 greatest commercials ever", espn.com, February 17, 2003, accessed on January 16, 2007.

- ^ Vancil, Mark. "Michael Jordan: Phenomenon", Hoop Magazine, December, 1991, accessed March 7, 2007

- ^ "Michael Jordan", forbes.com, accessed February 23, 2007.

- ^ Team Jordan, nike.com, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Rovell, Darren. "Cashing in on the ultimate cash cow", espn.com, April 15, 2003, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ "Michael Jordan signs deal with Bulls worth more than $30 million", Jet Magazine, September 15, 1997, available online at findarticles.com, accessed January 16, 2007.

- ^ Jordan's Streak Crashes and Burns at Indy, nba.com, December 27, 2002, accessed March 3, 2007.

- ^ Cover of December 23, 1991 issue of Sports Illustrated CNNSI.com, December 23, 1991, accessed January 16, 2007.

External links

- Michael Jordan

- 1963 births

- African American basketball players

- Basketball players at the 1984 Summer Olympics

- Basketball players at the 1992 Summer Olympics

- NBA's MVP prize winners

- Birmingham Barons players

- Chicago Bulls players

- Living people

- McDonald's High School All-Americans

- Minor league baseball players

- National Basketball Association executives

- NBA Defensive Player of the Year Award winners

- NBA Slam Dunk Contest champions

- North Carolina Tar Heels men's basketball players

- Olympic gold medalists for the United States

- Omega Psi Phi brothers

- People from Brooklyn

- People from Wilmington, North Carolina

- People from Chicago

- Sportspeople of multiple sports

- Washington Wizards players

- ACC Athlete of the Year

- Arizona Fall League

- American sportspeople