History of Farchants

The first written evidence of Farchant's history in Upper Bavaria is a note from the years 791 to 802 in a dispute between Count Irminher from the Tyrolean Inn Valley and Bishop Atto von Freising . In this note, Count Irminher and Bishop Atto announce that they will settle the dispute over the Farchanter Church . Archaeological finds in the area of today's Farchant municipality go back further and suggest settlement since pre-Roman times.

The history of Farchant is inextricably linked with the rule of the Principality of Freising in Werdenfelser Land , which lasted over 500 years, from 1294 to its dissolution by the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of 1803. The place then became part of Bavaria, and in the course of the administrative reforms in the Kingdom of Bavaria , with the municipal edict of 1818, today's municipality was created. With the rail connection at the end of the 19th century, a strong population growth began, which lasted until the beginning of the 21st century.

Archaeological finds

The Loisach Valley has played an important role as a traffic route between the Bavarian Alpine foothills via the Seefelder Sattel and into the Inn Valley since the Bronze Age . The copper , which is so important for bronze production in the foothills of the Alps, had to be procured from the Inn valley, which was particularly rich in copper ores in the Schwaz area . Until 1993, however, these were only theoretical considerations, because in southern Bavaria the use of Schwaz copper could only be archaeologically confirmed for one find from the Starnberg area.

The Oberammergau Emil Bierling found during a walk in September 1993 on the Spielleitenköpfl potsherds , bronze fibulae , bronze castings, iron machine and burned and unburned bones. In order to have the value of the finds checked, he sent them to the Institute for Prehistory and Protohistory at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich . The academic director at the institute, Amei Lang , examined the pieces and dated them to the more recent Hallstatt period . Was also Emil Bierling near the present-day cemetery a Pferdchenfibel, it is the Early La Tène , v approx 450-300. Assigned.

During the first excavations, a burnt offering place, parts of a Hallstatt-era bucket and numerous fibulae, ceramics and tools made of stone, bronze and iron were secured and documented. The conclusion of the excavation is that the site had to be on a traffic route between the Inn Valley and the Alpine foothills , as southern Bavarian and inner-Alpine elements are represented. Likewise, the copper ore used in the bronze objects most likely comes from the Inn valley. The excavation team assigns the horse brooch to the Celts ; this underlines that the area around Farchant can be accepted as a direct contact zone between the Celts and the Raiders .

During excavations in 2009, the excavation team found the foundation walls of two smaller cult buildings from the Hallstatt period. As well as surprisingly coarse ceramic shards from vessels from the younger Bronze Age in a pit carved into the limestone rock . These finds date back to around 1700 BC. BC to 1500 BC And thus proof that sacrifices took place 1000 years before the cult buildings were erected on the Spielleitenköpfl . The excavation team considers it rather unlikely that there was a hilltop settlement from the younger Early Bronze Age at this point. The pit can be seen as a landfill , which was created quite often in inaccessible places during this time. Nevertheless, this ensemble of finds from the Early Bronze Age, which was advanced furthest into the Alps , proves the importance of the Loisach Valley as part of an Early Bronze Age traffic route between the Alpine foothills and the Inn Valley.

Roman rule

In the Raetian war led by the Roman emperor Augustus , the general Drusus subdued in 15 BC. The Raetians and occupied the area around Farchant. In the years 195–210 BC In the 4th century BC, Emperor Septimius Severus had the mule track across the Alps, which had existed for centuries , expanded into a trade and military route, the Via Raetia . This road led via Verona - Trient - Sterzing (Vipiteno) - Matrei am Brenner (Matreio) - Wilten / Innsbruck (Veldideno) - Zirl (Teriolis) - Mittenwald (Scarbia) - Partenkirchen (Parthanum) to Augsburg (Augusta Vindelicum) . During this time the Romans improved the mule track near Farchant by building bridges and regulating the water. After its completion, this road represented the shortest connection from Rome to Augsburg and overtook the older Via Claudia Augusta as the primary transport connection between Raetia and Rome.

middle Ages

Germanization

In the 5th century, the area of today's Werdenfelser Land was still part of the western Roman province of Raetia, although the Roman ruling class had already left the province. In 526 the Ostrogoth king and ruler of Italy , Theodoric the Great, died . From this point on, the influence of power from Italy in the areas north of the Alps disappeared, so that the emerging Franconian empire under the Merovingians formally took over the rule of the former province of Raetia. In the middle of the 6th century the tribe of the Baiovarii (Bavarians ) was formed from various ethnic groups . This tribe, which was not entirely independent of the Franconian suzerainty, settled in all of today's Old Bavaria , with the exception of the border areas in the north, east and south. Around 600 AD, new Bavarian towns were finally built in the Loisach Valley , on the Roman road Via Raetia, which is still easy to drive in parts, on behalf of the Bavarian Duke Tassilo I. The area to be settled was not deserted, however, because the settlers encountered the remains of the Romanized Celtic and Rhaetian indigenous people in the Alpine valleys, who had mixed with the descendants of the Germanic mercenaries deployed on the imperial borders . The new settlements probably arose on the soil cultivated by the Romans. Farchant was also among the new local foundations and about two kilometers south of it the somewhat smaller Aschau. The settlers named their new settlement Forchheida (Föhrenheide) after the predominant landscape . Local research assumes that these new settlements were directly subordinate to the duke.

The first founders of the place (about half a dozen families) lived in simple log houses and ran their three-field economy exclusively south of the Spielleitenweg-Gern-Wankstraße line. The huge Loisachmoos, which merged into the Murnauer Moos , bordered north of the small village . During the construction of the railway line from Munich to Garmisch in 1889, the construction workers found around 20 row graves from around 650 in the area of today's train station in Farchant. The pagan grave supplements have been lost to this day. However, from this find it can be assumed with certainty that the first Farchant settlers were still pagans .

Christianization

Around 750 Irish and Scottish monks converted the Oberland to Christianity, with the founding of well-known monasteries in the area testifying to it: Schlehdorf and Benediktbeuern 740, Polling 757 and Scharnitz 763. It is believed that the inhabitants of Farchant and Aschau converted to Christianity during this period and built a wooden church in Forchheida . This church replaced an old cult site of the pagan local founders. Since then, the Farchanters have no longer buried their dead in row graves, but in the cemetery by the church.

First written mention

The first written mention of Farchant is a note from the years 791 to 802 in a dispute between Count Irminher from the Tyrolean Inn Valley and Bishop Atto von Freising . With this written receipt, simply called a slip of paper by the scribe Tagabert, the two agreed to avoid further arguments about the Farchanter Church in the future.

"PRO ECCLESIA QUI dicitur FORAHHEIDA notitia, qualiter IRMINHERI SEU ALII Socii EIUS QUAM plurimi QUI IN HOC CONTE TIONE CONIUCTI FUERANT CONTRA ATTONEM episcopum PRO ECCLESIA QUAE SITA EST IN LOCO NUNCUPANTE FORCHEIDA Victi atque LEGITIMATE SUPERATI REDDIDERUNT IN MANUS ATTONIS Episcopi IPSAM Ecclesiam SEU QUIQUID AD Illam Legibus PERTINERE VIDE BATUR ET STATUERUNT, UT NULLA CONTENTIO AMPLIUS EX ORTA ALIQUANDO ES IPSIS FUISSET IMPRIMIS IPSI TESTES EXTITERUNT QUI ANTE CONTRADIXIER UNT, HOC EST IRMINHERI, HRODLANDT, DEOTMAR, REGINO. DENIQUE ALII TESTES ADDUCTI SUNT QUI HOC AUDIERUNT ET VIDERUNT HOC EST. REGINHART; NIPOLUNC, KAGANHART, OADALKER, HITTO, EGO QUIDEM TAGABERTUS HANC CARTULAM SCRIPSI VISSIONE ATTONIS EPISCOPI. "

11th to 13th centuries

Around 1100 the manor in Farchant was almost exclusively in the hands of the nobility and knighthood. Most often the powerful Counts of Dießen-Andechs are mentioned as masters of people, animals and land. The monasteries of the Bavarian Oberland only slowly gained influence over the village through donations. In 1060 Count Otto von Dießen-Andechs and around 1070 Count Ambras in Tyrol with one property each, and the knight Rudolf von Ohlstadt with two properties in Farchant. Wiltrud von Hohenwart, who came from a family in the service of Andech, founded a convent near Schrobenhausen in 1081 . When it was founded, she gave away her entire fortune, including a farm from Farchant. Another Andechser service man, Bernhard von Weilheim, bequeathed a farm in Farchant to his daughter Mechthild when she entered the Wessobrunn convent .

Werdenfels Castle was built around 1200 on a rugged rock cone above the road between Garmisch and Farchant . The time when the castle was founded is controversial in castle research. However, the construction should be scheduled between the years 1180 and 1230. The client and the purpose of the original facility are also unknown.

A document from Marshal Berthold von Schiltberg from 1247 makes it clear that the majority of the residents of the village lived in serfdom. With this certificate, he renounced all claims “about the wife of Diemar zu Vorchhaim and her children” in favor of the Dießen monastery . His mother-in-law had given these subjects to the Dießen monastery.

Under Freising

In 1249, Werdenfels Castle and the Falkenstein Fortress and the surrounding area changed hands for 250 pounds of Augsburg coins . Knight Schweiker von Mindelberg sold his fortune in the upper Loisach valley to Bishop Konrad von Freising . In addition to the two castles, this included the forests and mountains between Plansee and Partnach and from the Zugspitze to the "hanging stone" near Oberau . The fishing waters of the Loisach and the Eibsee also went to the bishop. Up until this point in time, the Freising bishopric had appeared in the upper Loisach Valley through mere manorial rule. Now he advanced to judicial and administrative power, which were subordinate to three villages: Germarsgau (Garmisch), Aschau and Vorchhaidt (Farchant). A knight moved into the castle as keeper and judge.

In 1294, the Freising Bishop Emicho expanded the power of the Hochstift Freising in the Loisach Valley through purchases . The Hochstift acquired the Partenkirchen and Mittenwald markets as well as the Isar Valley and the Karwendel Mountains from the last Count of Eschenlohe . The Freising group combined their entire possessions to form the County of Werdenfels , which made it the largest sub-territory of the Hochstift Freising. In a Urbar 1315 Emicho left of Freising the rights and possessions in the county together to write, this also Farchant is mentioned. In the village stands the church of St. Andrew and the village has its own cemetery. Farchant belonged to the parish of Garmisch, which at that time stretched from Scharnitz to Oberau.

The oldest documented legal dispute of the Farchanters dates from 1392. Since ancient times they have enjoyed grazing rights in the Estergebirge behind the Fricken . The Ettal monastery , which was only half a century old but already very powerful , had a Schwaige on the Esterberg . The border disputes between Weide and Schwaige, which had been smoldering for a long time, were settled through a settlement.

Relocation of Aschau to Farchant

A significant event in the local history happened in 1494. In a detailed contract, nine manors decided to move the village of Aschau with its 13 farms to Farchant. One can only speculate about the reasons; the sinking or lack of spring water was probably responsible. It is also suspected that a kind of land consolidation was carried out with the evacuation, since many Aschauer were resident in Farchant at the same time. The place itself is mentioned between 1200 and 1300 as "Ascha" or "Aschaw". The name Aschau cannot be traced back to “ash” or “burn down”, as the oral tradition suggests, but the name can almost certainly be interpreted as “Eschenau”.

Modern times to the beginning of the 19th century

16th Century

In 1525 the peasant revolts raged in large parts of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation . Swabia in particular was the scene of the Peasants' War . The Werdenfelser Land with Farchant remained unaffected by this, as many of the required freedoms were enjoyed by the residents from ancient times. Every man in the county enjoyed free use of the forest and a share of hunting and fishing. Hard labor was also rare in Werdenfels, and the residents were able to choose their own judge. The Werdenfels farmers did not want to put all this at risk and therefore did not join the Swabian crowd.

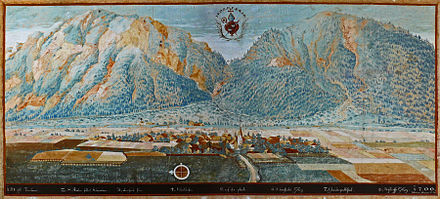

A first, more precise picture of the whole place can be seen from the tax table from 1546: The village consists of the Gothic St. Andrew's Church with a stately pointed tower and 31 houses in four districts. With 16 houses, the lower village clearly formed the focus of the place. There was a farrier and a boilermaker. 38 households suggest a population of around 200 people. After several months of struggle, a settlement was found in a border dispute between Farchant and the Bavarian town of Oberau in 1554. The Schafkopf, the Steinerne Brückl and the Fermeslain were highlighted as special border points. These three points marked the border between Werdenfels and Bavaria 250 years later.

Witch trials

At the end of the 16th century, sensational witch trials took place in the county , in which 51 people were convicted and executed as witches between 1590 and 1591 . Among these people was also a man, Simon Kembscher . A total of 127 people were accused of witchcraft during this period.

In 1583 the easily influenced Caspar Poissl von Atzenzell became the new caretaker in the county of Werdenfels. The inhabitants of the country had been very restless the years before. Plague epidemics , diseases, hailstorms that devastated the fields and dead animals terrified the general public. While the predecessor of the new caretaker was still moderating allegations of witchcraft, Poissl met open ears. When Ursula Klöck, who came from Tyrol, was accused of witchcraft by the Eibsee fisherman, the keeper had her taken to the Garmisch administrative building on September 28, 1589. Ten days later, two other women were arrested and put in dungeons. The experienced Schongau executioner and witch finder Jörg Abriel examined all three women , and the nurse Poissl wrote to his superiors about his judgment: "... all three women were found to be fiends because he really discovered the sign of the devil in them." With the embarrassing questioning pressed the nurse made confessions from the women, and another woman who was arrested in December was also suspected by questioning witnesses. The nurse then shipped the four accused to the dungeon of Werdenfels Castle. Without the permission of the Freising government, Poissl continued to torture and suspected more and more women. On December 21, one of the women committed suicide , after which the nurse held the first Maleficence Rights Day in January and sentenced the women to death . Six more days of maleficence law followed; in most cases , the convicts were burned alive by the Schongau executioner.

In the summer of 1590, the executioner's henchmen seized Rosina Krin , a mother of three children, from Farchant . She was accused of being "hung up" on a sick neighbor at night and of being in league with the devil. Under torture, she confessed to a relationship with a "tall man in a black robe" who secretly went out and in at her place. In September 1591 the entire fortune of the Krin family was taken up and valued at 59 guilders, and a little later the Krinin went the terrible walk at the stake . It is not known whether the widower had to pay the costs, but it can be assumed.

17th century

At the beginning of the 17th century, the village of Farchanndt consisted of the Gothic church and 43 houses, not a single one of which was completely bricked and most of them were built entirely from wood. The place now had a tavern as well as a grinding and saw mill. The four districts can still be clearly distinguished from one another. The place consisted of 50 households and had about 300 inhabitants. In 1623 a famine peaked in Farchant. For seven summers, hailstorms and thunderstorms had wiped out almost the entire grain harvest in the village. Drought and mouse-eating also contributed to constant crop failures. In order to deal with the famine, the Bishop of Freising had considerable quantities of grain bought in Lower Bavaria. The Farchanters dealt with the grain shortage in their own way: every Sunday, as long as the grain was in the fields, they wandered through the corridors with flags and bells ringing. The two lime kilns , on the other hand, were very busy . On the large construction site of the Freisinger Domberg , huge amounts of lime were required, which also came from Farchant. The main industry of Farchant in the 17th century was next to agriculture, especially rafting . In 1624 the Farchanters cut 1030 trunks of wood, which corresponds to around 90 rafts that went out to Bavaria. There were also eleven loads of charcoal and two loads of semi-finished goods.

pest

In the months of July and August of 1634 the plague reached its peak in Farchant, when eight people lost their lives to the plague at short intervals. The number of residents decreased by about 30 to 40 people from 1624 to 1640. This can only be taken as a rough estimate; how many people actually died of the bubonic plague during this period is not known.

Thirty years war

In 1632 the Thirty Years War reached the Bavarian Oberland . In order not to fall into the hands of the Swedes, the Freising Prince-Bishop Veit Adam fled first to the County of Werdenfels, which was part of the Prince-Bishopric of Freising, and later to San Candido in South Tyrol , which was also under Freising's rule. The Bishop's Chancellor , Dr. Plebst, negotiated a letter of protection with the advancing Swedes for 30,000 guilders , which was supposed to protect the Freising property. However, Kurbayern was at war with the Swedes, so that it was treason for the Bavarian Elector Maximilian . In retaliation, he attacked the royal seat of Freising on May 5, 1632 . The commander of the troops demanded even 5000 guilders arson . Only one day later, the Swedish King Gustav II Adolf quartered on the Freising Cathedral Hill and marched into Munich on May 18th . Many villages in the Oberland went up in flames in the following time, Murnau was occupied by a Swedish cavalry detachment in May 1632 and was not burned down for a pillage of 300 guilders. After Oberammergau and Eschenlohe , the Swedes plundered Ettal in June 1632 . The Werdenfelser Land was spared. The county keeper nevertheless made the road at Steinernen Brückl impassable, although the withdrawal of the Swedes was already foreseeable.

In 1646 the war of the County of Werdenfels came threateningly close again, even the Tyrolean rulers demanded that a ski jump be built at Steinernen Brückl :

"... by means of an average from one to the other through the Farchanter moss ... to create a generally useful definition work."

After many diplomatic discussions and correspondence, Tyrol , Bavaria and Freising finally agreed in November 1646 to build the ski jump at Steinernen Brückl . Construction began immediately, but had to be stopped a short time later due to the approaching winter. In 1647 the Werdenfelsers pursued the project with less zeal, since the theaters of war had receded, Werdenfels was spared again. When things got threatening again in the spring of 1648, the Freising people ordered the ski jump to be completed as soon as possible. This finally succeeded by the end of April, and the Werdenfels keeper had riflemen set up as guards at the ski jump and water was channeled into the trenches. The Thirty Years War ended on October 24, 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia , and the County of Werdenfels did not have to repel a single attack by the Swedes during the 30-year war.

War of the Spanish Succession

The county of Werdenfels was between the fronts of the Habsburgs and Wittelsbachers during the War of the Spanish Succession . The Freising Prince-Bishop Johann Franz tried to be neutral in this confrontation , and he instructed the Werdenfelser nurse to maintain a good neighborly relationship with the Tyroleans as well as with the spa Bavarians. When the conflict threatened to escalate in the Loisach Valley in 1702 , the Bavarians began again with work on a ski jump in the area around the Steinerne Brückl , this time to be able to repel possible attacks by the Austrians from the south. Shortly before Christmas, the palisade wall with a moat was completed. This hill stretched over the whole valley, only interrupted by the Loisach, and was about 1.6 km long in total.

On August 27, 1703, the so-called Battle of Steinernen Brückl took place at the hill . About 11,000 Austrian and Tyrolean troops held the Werdenfelser Land. The Bavarian troops were in retreat, and only 900 men held the position at the hill. The Bavarians had no chance against the overwhelming power of the imperial family, so that after four hours of fighting, the electoral captain Berdo with his officers and 60 soldiers had to surrender to the Austrians.

New church building

At the beginning of the 17th century, the Farchanter St. Andrew's Church had an exquisite past and rich furnishings, but this was contrasted with ecclesiastical irrelevance . The church stood empty almost the whole year , the Garmisch pastor had only scheduled nine services for Farchant , the residents even had to go to Garmisch for the baptism , which led to many complaints. To improve this situation, the Farchanters tried to become their own parish. They argued and complained with the prince-bishopric and parish Garmisch for over 100 years, but this brought no improvement. On May 24, 1700, the first order of worship between the parish of Garmisch and the parish of Farchant was sealed, and for about three decades there was calm in the Farchant church dispute . In 1727, with the permission of the Bishop of Freising, the Farchanters demolished the old Gothic church and built it for 4,400 guilders in a two-year construction period according to plans by the Munich city mason Johann Mayr the Elder. J. the baroque church that still exists today .

Napoleonic Wars

In 1800 Farchant felt the Napoleonic wars, which had been going on for years , because imperial troops occupied the Werdenfelser Land. On June 12th there was fighting between the French and Austrians in Eschenlohe and Oberammergau. In the next few days the French advanced as far as the Steinerner Brückl and occupied Oberau. A general armistice prevented a further march to Farchant, which remained occupied by the imperial troops. Many reports indicate that the population was better off under the French occupation than under the imperial one with its many war peoples. The Farchanters also sympathized more with the French than with the occupiers from the nearby Tyrol.

Although there was still an armistice, 20 Tyrolean riflemen who were quartered in Farchant planned an attack on the Oberauer Wirtshaus Unterm Berg , where the French had their headquarters . However, the Tyroleans had drunk the courage for this deed in a Farchant inn. The heap advanced at dusk over the Kirchbichl into French-occupied Bavaria and smashed the windows at the Unterm Berg inn . However, a group of French had taken up position behind their backs, having noticed the advance of the Tyroleans. This skirmish ended without bloodshed, however, as the Tyroleans held up their arms and the French handed them over to an Austrian officer at the Steinerne Brückl. The French received recognition and respect from the population for this act, while the Imperial glee and ridicule descended on them.

In November 1801 the imperial troops lost a decisive battle near Hohenlinden . A little later, Bavaria left the alliance with Austria and negotiated a separate peace with France. Below the Steinernen Brückl the French concentrated a formidable force, and on December 10 they occupied the Walchensee ago Wallgau as a first Werdenfelser place. Shortly before the end of the year, the Austrians had to evacuate the county of Werdenfels, which the French finally occupied by the end of January 1802. The French occupiers stayed in the towns until April. In secret treaties with France, the Electorate of Bavaria had secured the incorporation of 15 free imperial cities, 13 imperial abbeys and six principal bishoprics. The Principality of Freising and the County of Werdenfels were among these small states. On August 20, 1802, Bavarian troops marched into Werdenfelser Land. The administration passed more and more into electoral hands, and on November 26th the Farchanters finally lost their Freising citizenship and became subjects of the elector in Munich. In the course of secularization and the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss 1803, the monasteries lost the lordship over all Farchanter estates that the Bavarian state took over.

Modern times from the beginning of the 19th century

Independent municipality

In 1811 the previous tax district was converted into a municipality and on this occasion the authorities redefined the boundaries around the place. Johann Kirchmayer was the first royal mayor in office. The final self-administration of the community resulted in the course of the administrative reforms in the Kingdom of Bavaria, the second community edict of May 17, 1818. The community was administered by a community committee, which was composed of the community leader and the community caretaker.

Beginning of tourism

From the middle of the 19th century the Werdenfelser Land attracted many summer visitors with its natural beauty. These people, called “strangers” by the locals, were primarily artists and civil servants from Munich. In Farchant , the Kuhflucht waterfalls , Esterbergalm, Krottenkopf , Reschbergwiesen and the Werdenfels castle ruins were popular sights. So wrote the gazebo in 1897 :

“[…] A wild and romantic gorge […] In it, a creek rises from a large cave-like hole in a huge bare rock wall, which plunges in seven foaming waterfalls to Thal. The cascade falls can be reached from Farchant via Mühldörfl in three quarters of an hour on a comfortable and picturesque path. "

At the end of the 19th century there was still no railroad going to Farchant. In Murnau am Staffelsee was the terminus for the railway built from Munich. The summer visitors often walked the way to Farchant from Murnau or used the post van , which was considered to be quite unreliable . For example, travelers complained about “bad roads” and “inadequate postal facilities” that consisted only of a “sad yellow post bus”. In 1889, the local rail company then expanded the line to Garmisch-Partenkirchen. Farchant also received a train station, but the hoped-for increase in the number of guests did not materialize. In order to stimulate tourism , the community had the old Mühlgasse expanded into Bahnhofsstraße and built a new inn with the “Railway Restoration Kuhflucht”. The population of Farchant saw an 80 percent increase at the turn of the century. The supply of the residents ensured the mass transport of goods by rail. Real estate trading also gained momentum in Farchant, and so villas and country houses were built on formerly agricultural land around the old town center. The former Mühlgasse expanded into a new development axis in Farchant. The aim of the Beautification Association, which was established in 1887, was to promote the flourishing tourism and to open up the town's sights. The community committee relied on tourism in the local development and gave clear rejection of the settlement of industrial companies. In 1935 the Nazi dictatorship dissolved the Beautification Association.

First World War

From 1915 on, the lack of raw materials in Farchant became noticeable, which was caused in Germany by the First World War . Many of the children had torn clothes and were doing household and farming activities on their parents' property. At Christmas 1915, the parish had to list all the copper components of the Farchant church to the Garmisch district office and keep them ready for delivery. The municipality reported the four existing church bells to the district office in spring 1917. Two bells were then melted down for the German armaments industry. Shortly before the end of the war in 1918, the residents were able to prevent the church's copper tower roof from being torn down. A total of 21 Farchanters fell victim to the First World War.

November Revolution 1918 and Soviet Republic

Kurt Eisner proclaimed the Republic of Bavaria on the night of November 8, 1918 at the first meeting of the workers 'and soldiers' councils in Munich and declared the Wittelsbach royal family to be deposed.

“The Wittelsbach dynasty has been deposed! From now on Bavaria is a free state! "

The next day the residents of Farchant could read in the Werdenfelser Anzeiger :

“Private news says that riots have broken out in the capital. After a mass people's meeting on Theresienwiese, parades were held in the city and shops were looted. A workers and soldiers council has been formed. "

On November 12th, the first council institutions were formed with the soldiers 'council and on November 21st with the farmers' council in the Garmisch district office. Kurt Eisner was murdered on February 21, 1919 by the 22-year-old Lieutenant Count Arco on Valley with several pistol shots. The residents in Werdenfelser Land rejected the Soviet republic, and the Garmisch district office set up a vigilante group as early as 1919 . In April 1919, the Mittenwald workers' councils Böcklein and Murbäck organized a command of Red Guards with workers from the Walchensee power plant to conquer the Garmisch district. On April 23, 1919, the Red Guards met the Garmisch vigilante group on the Lahnewiesgraben southwest of Farchant. In the following shooting, the vigilante killed four Red Guards, Murbäck was seriously injured. This incident went down in local history as the "Spartakist attack".

The Garmisch district office then set up the Werdenfels Freikorps to restore orderly conditions . The 360-strong Freikorps under Colonel Franz Ritter von Epp moved to Munich at the end of April and beginning of May. The Freikorps played a key role in the violent termination of the Soviet Republic.

time of the nationalsocialism

The National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), founded in Munich in 1920, hardly appeared in public in the Garmisch district. After the Reich and Landtag elections in May 1928 , a strong growth in the Nazi movement could also be observed in Werdenfelser Land. A network of local Nazi bases succeeded in attacking all political parties in the Farchant region between 1928 and 1932. In the first few years the anti-Semitic stance of the NSDAP was an obstacle for the party, as the town, which has meanwhile benefited from increasing tourism, feared the absence of Jewish guests. The first members of the party were mostly non-residents. The NSDAP then tried successfully in the Garmisch district to put local references in front of the propaganda cart . For example, the Werdenfels Freikorps was discussed again and again in order to portray the Werdenfelsers as the “saviors from Bolshevism”.

On January 30, 1933, Reich President Paul von Hindenburg appointed the leader of the NSDAP, Adolf Hitler , as Chancellor of the German Reich . In the Reichstag election on March 5, 1933 , the NSDAP achieved 51.53 percent in Farchant, 46.21 percent in the entire Garmisch district and 43.9 percent in the German Reich. At the end of March, SA people searched the apartment of the railway secretary Fritz Wandel in Farchant for weapons. However, nothing could be found. In 1935, the National Socialists introduced street names to the community in Farchant. They replace the house numbers that have been in effect since around 1790. The Dorfgasse and today's main street was called Adolf-Hitler-Straße until 1945 .

End of war 1945 and post-war period

During the war , the Wehrmacht installed a locking bar on the historic Steinernen Brückl . In order to be able to defend this barrier better, German mountain troops began to set up eight fighting positions in mid-April 1945 . These were located north of Farchant on the foothills of the Ammer Mountains . Traces of these fighting stalls can still be seen in the landscape today. They were solidly built and provided with an earth-coated round wooden ceiling. The American 10th Panzer Division took the city of Schongau on April 27, 1945 . It was important for the Americans to get their hands on the Echelsbach Bridge , which is 15 kilometers south of the city, intact. This bridge spans the Ammer Gorge at a height of 76 m and forms an important link on the march to Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

On April 29, 1945, at three o'clock in the morning, units overwhelmed the sleeping bridge crew and the American troops were able to advance as far as Oberammergau . Until about 3:00 p.m. on April 29, a column of German soldiers from various parts of the army rolled through Farchant on Olympiastraße from Oberau. More and more military equipment remained on the Föhrenheide and on the northern outskirts. The soldiers tried to escape the way to the prisoner of war on foot by retreating into the surrounding mountains. In many huts and caves in the mountains around Farchant, soldiers of the Wehrmacht hid themselves for some time and asked the population for civilian clothing and food. In the afternoon, under the leadership of the German major Pössinger, a group of parliamentarians from Garmisch-Partenkirchen made their way to Oberammergau through the town. The parliamentarians wanted to offer the Americans the surrender of Garmisch-Partenkirchen and its neighboring towns. The situation in and around Garmisch-Partenkirchen was catastrophic at the end of the war, more than 10,000 wounded lay in the on- site hospitals , and the area was full of refugees from southern Germany and the eastern regions. High staff and ministers also moved into Werdenfelser Land by April 26th. To escape a bombardment, and in defiance of command situation, officers determined the armed forces to a "surrender without bloodshed due to the hopeless situation," Quote of the location elders in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Colonel Ludwig Hörl . The first Americans came into town at 5 p.m., and Pössinger and the rest of the parliamentarians were tied to the pipes of the top armor. The Americans accepted the surrender, and so Garmisch-Partenkirchen and its surroundings were saved from the planned air raids . At around 7:00 p.m., German soldiers shot at the Americans who had marched into Farchant from the road to Esterberg, and they returned fire from the southern outskirts with tanks. From 8 p.m. the troops began to search the houses in Farchant, and the next day the Mühldörfl had to be evacuated. On May 6, 1945, a German Fieseler Storch - Fi 156 aircraft had to make an emergency landing on a steep slope near the Gießenbach in the Ammer Mountains. The pilot Josef Kuhn survived unharmed and made his way through the Ammer Mountains and on to his hometown Günzburg in the turmoil after the German surrender . The Farchanter corridor name has since been "on the plane".

The population of Farchant did not see any negative behavior by the occupation forces , although some uncertainty remained. Dark skinned people were a whole new experience for many of the community's residents. At the pasture , today's old sports field, the Americans installed a repair point for tanks and motor vehicles. Girls who spoke English acted as auxiliary interpreters, while the boys were assigned to the Americans to help clear German ammunition and weapons. The supply company of the 54th Armored Infantry Battalion was housed in Farchant in the Gasthof Alten Wirt, the affiliated staff in the Gasthof Kirchmayer. Across from the old landlord, the supply company set up a baseball field on a large meadow . There were no more food deliveries to the region, so everything necessary for life had to be obtained on the black market , where valuables could only be traded on. The hungry and freezing population stole grass and hay from the barns and dug up potatoes before the harvest time. In the Farchanter School, the Americans introduced school meals, in which children who were underweight were given donated food such as cocoa, porridge or sandwiches. Like most places in Bavaria, Farchant had to take in many refugees from the Sudetenland . The people who fled with few possessions were assigned to families in Farchant. The refugees were also housed in the so-called Fliegerheim , a military barracks on the Ried . Later, the community built settlement blocks in the Föhrenheide. Many of the Sudeten Germans in Farchant then built their own homes in the Farchanter Föhrenheide in 1963 as part of the Catholic settlement scheme .

Development of the population

| year | Residents |

|---|---|

| around 600 | ≈50 |

| 1546 | ≈200 |

| 1624 | 347 |

| 1730 | 350 |

| 1840 | 360 |

| 1871 | 327 |

| 1900 | 442 |

| 1925 | 734 |

| 1939 | 1237 |

| 1950 | 1941 |

| 1961 | 2105 |

| 1970 | 2835 |

| 1987 | 3220 |

| 1995 | 3658 |

| 2000 | 3757 |

| 2005 | 3717 |

| 2010 | 3683 |

| 2015 | 3655 |

As described above, it can be assumed that the first settlers of Farchant were about half a dozen families, i.e. about 50 people. A tax table from 1546 gives a first, more precise picture of Farchant, with 38 households occurring , a population of around 200 people can be inferred. The census carried out on behalf of the government from Freising came to 64 households with 347 inhabitants in Farchant in 1624. Farchant was the fourth largest town in the county of Werdenfels. The tax table from 1730 gives interesting statistical details: In 65 houses there are exactly 71 households, or 350 inhabitants. 66 of them are described as fit for military service and 87 as taxable.

See also

Web links

literature

- Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik. Self-published, Farchant 1979.

- Heimatverein forcheida eV (Ed.): Forcheida - Contributions from the Farchanter Heimatverein. self-published, Farchant.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Amei Lang: The Iron Age cult site on the Spielleitenköpfl near Farchant. In: forcheida. Volume 4, 1995, p. 4.

- ↑ Amei Lang: The Iron Age cult site on the Spielleitenköpfl near Farchant. In: forcheida. No. 4, 1995, pp. 7-12.

- ↑ Amei Lang, Heiner Schwarzenberg: The Hallstatt-time burnt offer place on the Spielleitenköpfl near Farchant. In: forcheida. Issue 16, 2010, p. 9.

- ↑ a b c d e f Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. p. 4.

- ^ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Heimatlexikon - Römerstrasse. In: forcheida. Issue 10, 2003, p. 13.

- ^ Willy Hochholdinger: Via Raetia. (No longer available online.) In: www.goldene-landl.de. Archived from the original on October 19, 2010 ; Retrieved May 19, 2011 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Siegfried Walther: The origins of Farchant and Aschau. In: forcheida. Issue 12, 2006, pp. 3-4.

- ↑ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Heimatlexikon - row graves. In: forcheida. Issue 10, 2003, p. 13.

- ↑ a b Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. S. 5.

- ^ Andreas Liebl: Considerations on the first written mention of Farchant. In: forcheida. Issue 13, 2007, pp. 3-6.

- ^ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. pp. 5-6.

- ↑ Joachim Zeune: Traces of the Past . Ed .: Heinrich Spichtinger. Adam-Verlag, Garmisch-Partenkirchen 1999, The castle of the early 13th century, p. 17 .

- ^ Werner Meyer: Castles in Upper Bavaria . Würzburg 1986.

- ^ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. pp. 6-7.

- ^ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. P. 7.

- ^ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. S. 8.

- ^ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. P. 9.

- ^ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. pp. 16-17.

- ^ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. P. 20.

- ↑ a b c Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. P. 26.

- ^ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. P. 31.

- ↑ Fritz Kuisl: The Witches of Werdenfels . Hexenwahn in Werdenfelser Land, reconstructed on the basis of the trial documents from 1589 to 1596. Adam-Verlag, Garmisch-Partenkirchen 1979, p. 6th f .

- ^ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. P. 40.

- ↑ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. P. 45.

- ↑ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. pp. 65–66.

- ^ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. P. 80.

- ↑ Josef Brandner: Around the Landl . Adam-Verlag, Garmisch-Partenkirchen 1993, 200 muskets for national defense, p. 167-168 .

- ↑ Hochstiftsliteralien von Freising . Main State Archives, Munich (Abh. 2, No. 62f).

- ↑ Josef Brandner: Around the Landl . Adam-Verlag, Garmisch-Partenkirchen 1993, The Schwedenschanze from 1648, p. 168 f .

- ↑ Josef Brandner: Around the Landl . Adam-Verlag, Garmisch-Partenkirchen 1993, Habsburg versus Wittelsbach, p. 171-172 .

- ↑ Josef Brandner: Around the Landl . Adam-Verlag, Garmisch-Partenkirchen 1993, Die Schlacht am Steinernen Brückl, p. 172-174 .

- ^ Josef Brandner: 50 years of the parish of St. Andreas. In: forcheida. Volume 5, 1996, pp. 5-16.

- ^ A b Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. S. 175.

- ^ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. P. 176–179.

- ^ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. P. 187.

- ^ H. Clément: The Bavarian community edict of May 17, 1818. A contribution to the history of the development of local self-government in Germany. Dissertation Freiburg i. B., 1934.

- ↑ Josef Brandner: Forays through the beginnings of tourism. In: forcheida. Volume 6, 1997, pp. 3-5.

- ↑ In the cow escape . In: The Gazebo . Issue 15, 1897, pp. 260 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- ↑ Josef Brandner: Forays through the beginnings of tourism. In: forcheida. No. 6, 1997, pp. 6-8.

- ↑ Josef Brandner: Pleasure for hurray patriotism and delusion. In: forcheida. Issue 11, 2004, p. 17.

- ↑ Quoted from: Stefan Schnupp: Revolution and Government Eisner . (PDF; 1.07 MB) In: House of Bavarian History (Ed.): Revolution! Bavaria 1918/19 . House of Bavarian History, Augsburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-937974-20-0 (Booklets on Bavarian History and Culture 37), pp. 12–18, here p. 12.

- ↑ a b c Alois Schwarzmueller: Garmisch-Partenkirchen in the November Revolution 1918. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on April 18, 2012 ; Retrieved January 9, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Alois Schwarzmueller: The development of the NSDAP in the Garmisch district up to 1933. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on September 9, 2011 ; Retrieved January 9, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Alois Schwarzmueller: The arbitrary and terror rule begins. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on March 4, 2016 ; Retrieved January 9, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Alois Schwarzmueller: 1933 - The beginning of the National Socialist dictatorship in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on March 4, 2016 ; Retrieved January 9, 2012 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Josef Brandner: Farchanter Heimatlexikon - street names. In: forcheida. Issue 10, 2003, p. 13.

- ^ A b c Siegfried Walther: The end of the war in Farchant in 1945. In: forcheida. Issue 14, 2008, pp. 47-49.

- ↑ a b c d Klement Jais: The end of the war in Farchant in 1945. In: forcheida. Issue 14, 2008, pp. 49-50.

- ↑ Siegfried Walther: The "Farchanter Flieger". In: forcheida. Issue 14, 2008, pp. 17-20.

- ↑ Bob Weber: Memories of Farchant 1945. In: forcheida. Issue 16, 2010, p. 48.

- ↑ Hans Leitenbauer senior: There is more to come…. In: forcheida. Volume 9, 2000, pp. 36-39.

- ↑ Hans Leitenbauer senior: Childhood experiences: Expulsion from the Sudetenland. In: forcheida. Issue 11, 2004, pp. 11-15.

- ^ A b Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. P. 65.

- ^ A b Josef Brandner: Farchanter Drei-Föhren-Chronik , Farchant, 1979. P. 138.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n GENESIS-Online. Bavarian State Office for Statistics and Data Processing, accessed on May 1, 2011 .