black

|

Borough black

|

||

|---|---|---|

| coat of arms | Austria map | |

|

|

||

| Basic data | ||

| Country: | Austria | |

| State : | Tyrol | |

| Political District : | black | |

| License plate : | SZ | |

| Surface: | 20.2 km² | |

| Coordinates : | 47 ° 21 ' N , 11 ° 42' E | |

| Height : | 545 m above sea level A. | |

| Residents : | 13,791 (January 1, 2020) | |

| Population density : | 683 inhabitants per km² | |

| Postal code : | 6130 | |

| Area code : | 05242 | |

| Community code : | 7 09 26 | |

| NUTS region | AT335 | |

| UN / LOCODE | AT SCZ | |

| Address of the municipal administration: |

Franz-Josef-Strasse 2 6130 Schwaz |

|

| Website: | ||

| politics | ||

| Mayor : | Hans Lintner ( ÖVP ) | |

|

Municipal Council : (2016) (21 members) |

||

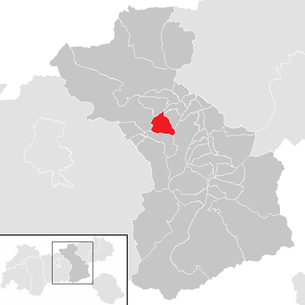

| Location of Schwaz in the Schwaz district | ||

View over Schwaz from the northeast |

||

| Source: Municipal data from Statistics Austria | ||

Schwaz is a district capital with 13,791 inhabitants (as of January 1, 2020) in the state of Tyrol in Austria . The community is located in the judicial district of Schwaz .

geography

location

The district capital Schwaz is located in the middle Lower Inn Valley about 30 km east of the provincial capital Innsbruck at the foot of the Kellerjoch ( local mountain and panoramic mountain , 2344 m ) and the Eiblschrofen .

The municipality extends over an area of 20.17 km². The settlement has been determined for centuries by the Lahnbach , which built up the local rubble cone through the transport of gravel and floods and divides the city into the market and village areas . At the same time, there is a subdivision into the geographical settlement areas of Ried, Pirchanger, Bleiberg, Ost, Sonnseite, Surheim and Falkenstein.

Neighboring communities

Buch in Tirol , Fügenberg , Gallzein , Pill , Stans , Vomp

Population development

Source: Statistics Austria

history

Early history

The area around Schwaz was already settled in the Neolithic (4000–2000 BC) and Bronze Age (from 1500 BC, finds near St. Martin). The site itself was first mentioned in a document as "Sûates" in 930/31.

Around 1170, the Fruntsbergers (later Freundsbergers) built a simple residential tower on the hill above Schwaz, which they expanded into Freundsberg Castle in the 13th century . The first bridge over the Inn was built in the 14th century .

Mining and heyday

The townscape was initially of a rural character, but after the discovery of the silver and copper deposits it soon advanced to metropolitan dimensions. As early as the Bronze Age, copper was mined in the mountains between Schwaz and Kitzbühel , which, in combination with tin , was needed for the production of bronze . At the heyday of mining in the 15th and 16th centuries, Schwaz was the largest mining metropolis in Europe with 20,000 inhabitants (around 13,000 today) and the second largest town in the Habsburg Empire after Vienna . 85 percent of the worldwide silver mining of the then known world takes place in Schwaz. With the takeover of the ore mines in Tyrol, Fugger's share in the global copper trade volume increased from 40 to 80 percent.

According to an unconfirmed legend, silver mining in the Schwaz silver mine began in 1409, when the maid Gertraud Kandlerin is said to have discovered a stone containing silver ore while grazing a bull on the Kogelmoos (area above the village). Around 1420, rich ore mines were opened on the Falkenstein for the first time, and the immigration of skilled miners from Bohemia and Saxony began. Within a few years, metal production in Schwaz became a European economic factor, and the Falkenstein became a source of silver and money for the Habsburgs. The Augsburg trading families Fugger and Paumgartner were present during the silver mining period. The doctor Paracelsus ( Philipp Aureol Theophrast Bombast von Hohenheim in Egg an der Sihl ) also visited Schwaz twice (1516 and 1533/1534) on his research trips to deal with mining diseases and probably received information from the Schwaz doctor Johannes Milchtaler.

The decline of the silver age in Schwaz began with the import of cheap silver from American opencast mines .

In the period from 1420 to 1827, 2,571 tons of silver and 190,999 tons of copper were mined.

In 1558 Georg Rösch von Geroldshausen wrote the following rhyme about the "mother of all mines" :

Swatz is all perckhwerck muater of it

nert sych ayn even gross

schart Whether treyssygh Taussent, I was right

Of men, women, yungh and old.

Transfer into New High German :

Schwaz is the mother of all mines.

A very large crowd [of people] thirty thousand feed on it

, if I am right [I remember correctly]

men, women, young and old.

Reformation and Counter Reformation

From 1521 the Swiss Protestant theologian Jacob Strauss (1480–1530) worked as a preacher in Hall and Schwaz and had a large audience. In his Reformation sermons he criticized Catholic teachings and condemned interest and usury. The bishop of Brixen was able to cause that he had to flee Tyrol, even though a majority had become Protestant. Only the Franciscan monastery formed the last Catholic bulwark in the place. In the parish church of the Assumption of Mary, on the other hand, the wooden partition also created a religious division: on the one hand, citizens celebrated the Latin mass, on the other, miners celebrated the German Lutheran service .

In 1525 the miners joined the peasant revolts, which were suppressed and condemned by the German reformer Martin Luther . After that, the non-violent Anabaptist movement became very popular. Jakob Hutter (1500–1536) was one of the charismatic leaders, and he moved through the Pustertal , where he founded several Anabaptist churches that practiced the baptism of confession and community of property . As " heretics " they were persecuted by both Protestants and Catholics. Around 500 Anabaptists were executed in Schwaz, Rattenberg and Brixlegg , and others were expelled from the country.

In 1532 the evangelical singer and poet Hans Sachs (1494–1576) founded a master singing school in Schwaz .

With the beginning of the Counter Reformation from 1575, the Catholic creed became mandatory again; those who wanted to remain evangelical had to live their faith in secret or emigrate. It was not until Emperor Joseph II's 1781 patent of tolerance that Protestant congregations could be re-established. Protestant Christians from the Zillertal were still forced into exile in 1837 . In 2017, only about 230 Protestant Christians lived in Schwaz, who made up 0.7 percent of the population.

19th century

After the decline of mining and the destruction of large parts of the place in the Napoleonic Wars , an upswing was initiated in the 19th century by the following institutions:

- 1819 District High School

- 1830 Establishment of a production facility for tobacco products (closed in 2005; demolished, shopping center)

- 1837 District court opened

- 1858 station

- 1871 commercial advanced training school

- 1876 old people's home

- 1889 first Schwaz swimming pool

- 1897 first electricity connections

- 1898/99 Establishment of the Franz Joseph Hospital

- 1900 business school

On September 16, 1899, Schwaz was elevated to the status of a city by Emperor Franz Joseph I by resolution of April 28 . This late elevation is due to the fact that Schwaz never had a city wall despite and because of its size . For the same reason, at the time of the silver mining under Emperor Maximilian I, the mint was not on site, but in the fortified hall , about 17 kilometers west of Schwaz.

20th century

Until the First World War , Schwaz was a garrison town of the Austro-Hungarian Army ; in 1914 the III. Battalion of the Salzburg Infantry Regiment Archduke Rainer No. 59 .

On July 10, 1999, there was a rock fall from the Eiblschrofen. After that, the movement of the mountain has been for many years means placed GPS - sensors measured. Armored bars and a dam were built to protect settlement areas. The silver forest is now a biotope and recreation area.

In 2017 Schwaz was awarded the honorary title of “ European Reformation City ” by the Community of Evangelical Churches in Europe .

In August 2017 Schwaz was the second Tyrolean municipality to be awarded the title “ Fair Trade City ”.

Culture and sights

- Parish church Maria Himmelfahrt : The city parish church, a four-aisled hall church built in 1460 , was expanded in 1502 and is now the largest hall church in Tyrol. The citizens sat on the left, the miners on the right, separated by a wooden wall. A special feature of this church are the two bell towers, one of which is around 400 years younger. It was built in 1911 after the older one in the upper third showed a critical inclination and was threatened with collapse when the bell rang.

- Parish Church of St. Barbara (1984/85)

- The Franciscan monastery in Schwaz with its cloister, which is well worth seeing with its Gothic wall painting, was inaugurated in 1515.

- The Episcopal Grammar School Paulinum emerged from a grammar school founded in Brixen in the 19th century and was re-established in Schwaz in 1926 due to repression by fascist Italy .

- Freundsberg Castle of the Lords of Frundsberg on a hill 170 m above the town. The Schwaz City Museum is housed in the tower of the castle. It shows, among other things, the development of the city and mining in Schwaz. The Fruntspergfähnlein meets monthly in the knight's hall .

- The Fuggerhaus was built around 1525 as the residence of the Augsburg trading family. From here, Anton Fugger temporarily led his empire. Today the house is the seat of the tertiary school sisters.

- The trading house is a late Gothic town house that was built from 1500–1509 by the two trades Hans and Jörg Stöckl. The large building includes a three-story arcaded courtyard and is now used as the town hall.

- The Franz-Josef-Straße is the former main road and is now a pedestrian zone. Despite the fire of 1809, it looks like a closed street. At the end of the street is the Baroque Tannenberg-Enzenberg Palace .

- The Museum der Völker shows art objects from distant cultures. Ethnographic exhibits from Africa and Asia are on display.

- The Schwaz silver mine is located at the eastern end of the city. The Sigismund-Fürstelauf Erbstollen, which was opened in 1491, was opened to visitors in 1989/90. A mine train drives 800 m into the tunnel.

- The Zeiss Planetarium Schwaz is one of the world's most modern small planetariums. Since 2001 it has been imparting knowledge about the world of stars to visitors from the region and neighboring countries. In 2006 it was equipped with the new FullDome technology in order to be able to show modern 3D films.

Regular events

- The Salva Guardia zu Schwaz , an association first mentioned in 1686, which accompanies the Holy of Holies in processions, was recognized by UNESCO in 2013 as an intangible cultural heritage in Austria under the name Sacramentsgarden in Tyrol .

- Starting in 1993, the Outreach Festival and the Outreach Academy take place in Schwaz every year.

- The Austria-wide renowned festival for new music Klangspuren has been held annually in Schwaz since 1994 and is located in the Museumsquartier in Vienna.

- Regular special exhibitions with ethnographic collections, modern non-European art and photo exhibitions in the Museum der Völker.

Sports

- Skiing : TU Schwaz Skiing Section , Schwaz Ski Club

- Baseball : Tigers Schwaz

- Basketball : Silverminers Schwaz

- Archery : BSC Schwaz-Vomp

- Handball : ULZ Sparkasse Schwaz

- Soccer : SC Schwaz

- American Football : AFC Hammers Schwaz

- Airsoft : ASVT Airsoft Sport Verein Tirol

- Pekiti Tirsia Kali : Pekiti Tirsia Kali Schwaz

- Badminton : TU Schwaz Badminton Section

- Tennis : TC Schwaz

- Recreational sports : Hobby Club Schwaz

Town twinning

-

Mindelheim , a small German town with around 14,000 inhabitants in Upper Swabia , has been Schwaz's twin town since 1990.

Mindelheim , a small German town with around 14,000 inhabitants in Upper Swabia , has been Schwaz's twin town since 1990. -

Bourg-de-Péage is located in the Drôme department in south-eastern France between Grenoble and Marseille.

Bourg-de-Péage is located in the Drôme department in south-eastern France between Grenoble and Marseille. -

East Grinstead is a small town in southwest England with a population of about 25,000 in West Sussex .

East Grinstead is a small town in southwest England with a population of about 25,000 in West Sussex . -

Sant Feliu de Guíxols on the Costa Brava in Spain with about 22,000 inhabitants.

Sant Feliu de Guíxols on the Costa Brava in Spain with about 22,000 inhabitants. -

Tramin is the South Tyrolean partner village of Schwaz.

Tramin is the South Tyrolean partner village of Schwaz. -

Verbania on Lake Maggiore is another Italian town with around 31,000 inhabitants.

Verbania on Lake Maggiore is another Italian town with around 31,000 inhabitants. -

Satu Mare , a Romanian city with about 115,000 inhabitants.

Satu Mare , a Romanian city with about 115,000 inhabitants. -

Trento , or the Trient-Argentario district with around 13,000 inhabitants.

Trento , or the Trient-Argentario district with around 13,000 inhabitants.

coat of arms

| Blazon : "Under of red and silver twice divided shield main silver a black hammer and chisel ." | |

| Justification of the coat of arms: The diagonally crossed mallets and irons symbolize the long and great mining past of the city, the Austrian colors (the Austrian binding shield ) in the shield head refer to the former importance as the largest Tyrolean mining town and at the same time the largest silver mine in all of Europe. Older versions of the coat of arms show sticks and irons with handles in natural colors. |

Personalities

Honorary citizen

- Ernst Brandl (1919–1997), biochemist and university professor

- Walter Waizer (1914–1998), managing director

- 2017: Günther Berghofer (* 1938), entrepreneur

sons and daughters of the town

- Georg Scherer (1540–1605), preacher of the Counter Reformation

- Edmund Zoz (1653–1706), Cistercian Abbot

- Johann Karl von Reslfeld (1658–1735), baroque painter

- Christoph Anton Mayr (≈1720–1771), Rococo church painter

- Corbinian Gärtner (1751–1824), Benedictine, university professor, lawyer and historian

- Eberhard Zobel (1757–1837), Benedictine, painter, art collector and teacher

- Maria Anna Moser (1758–1838), painter

- Johann Michael Albaneder (1762–1824), sculptor, embosser and ceramist

- Alois Lergetporer (1786–1851), Mayor of Salzburg 1831–47

- Johann Endfelder (1791–1862), painter

- Albert Jäger (1801–1891), Benedictine, historian, politician

- Joseph Wopfner (1843–1927), landscape painter

- Alfons Siber (1860–1919), painter and restorer

- Franz Haider (1860–1947), sculptor and art teacher

- Josef Andergassen (1861–1929), cabinet maker, altar builder and sculptor

- Franz Kobald (1866–1933), sculptor

- Max Angerer (1877–1955), painter

- Jakob Rappel (1877–1942), goldsmith

- Theodor Scheffauer (1878–1923), politician ( CSP )

- Emanuel Raffeiner (1881–1923), painter

- Toni Kirchmayr (1887–1965), painter and restorer

- Johannes Messner (1891–1984), theologian and legal scholar

- Joseph Messner (1893–1969), musician and composer, cathedral conductor of Salzburg

- Karl Severin Unterberger (1893–1984), sculptor and painter

- Josef Prantl (1895–1951), composer and music director in Bludenz

- Carl Rieder (1898–1980), painter, draftsman and created church windows, frescoes and sgraffiti

- Oswald Marchesani (1900–1952), ophthalmologist and university professor

- Josef Ausserhofer , pharmacist and writer

- Sepp Baumgartner (1901–1987), sculptor

- Wilhelm Angerer (1904–1982), photographer

- Fred Hochschwarzer (1914–1990), painter

- Fritz Eller (1927–2018), Austrian-German architect and architecture professor

- Adolf Laimböck (1933–2018), German actor

- Hartwig Karl Unterberger (1934–2019), painter and sculptor

- Gert Chesi (* 1940), photographer, author and journalist

- Traudl Hecher (* 1943), ski racer

- Margarethe Heubacher-Sentobe (* 1945), architect

- Hans Köchler (* 1948), philosopher

- Günther Maria Garzaner (1951–2015), writer

- Wolfgang Lechner (* 1953), journalist

- Markus Egg (* 1954), historian and associate university professor

- Harry Prünster (* 1956), comedian

- Johannes Schneider (* 1956), Franciscan, theologian

- Beate Palfrader (* 1958), politician (ÖVP)

- Armin Kogler (* 1959), ski jumper

- Erich Rinner (* 1960), solo trumpeter

- Elisabeth Kirchler (* 1963), ski racer

- Johannes Rosenberger (* 1965), film producer

- Martin Leutgeb (* 1966), actor

- Doris Danler (* 1966), diplomat

- Franz Hackl (* 1967), jazz musician and instrument maker, organizer of the Outreach Festival & Academy

- Daniela Knapp (* 1972), camerawoman

- Martin Höllwarth (* 1974), ski jumper

- Christoph Gruber (* 1976), ski racer

- Johannes Aigner (* 1981), soccer player

- Rainer Eitzinger (* 1983), tennis player

- Anna Braun (* 1984), natural track tobogganist

- Tobias Angerer (* 1990), natural track tobogganist

- Stephanie Brunner (* 1994), ski racer

Associated with Schwaz

- Hans Schlaffer († 1528), Anabaptist reformer, executed in Schwaz

- Hans Maler zu Schwaz (1480–1529), important portrait painter of the Renaissance

- Jacob Strauss (1480–1530), Protestant preacher and reformer from 1521 in Schwaz

- Johannes Milchtaler (16th century), doctor and medical writer from Schwaz

- Hans Sachs (1494–1576), founder of the Mastersingers School in Schwaz

- Cordula Wöhler (1845–1916), Catholic writer and poet, lived in Schwaz for over 30 years and is buried there

- Ludwig Penz (1876–1918), sculptor

- Max Bär (1903–1944), resistance fighter

literature

- Wolfgang Suppan : Schwaz in Tyrol. In: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon . Online edition, Vienna 2002 ff., ISBN 3-7001-3077-5 ; Print edition: Volume 4, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-7001-3046-5 .

Web links

- 70926 - Schwaz. Community data, Statistics Austria .

- Panorama map of the Karwendel silver region

- History of the Schwaz silver mine

- The Silberberg. When the world's first modern financial center emerged in the Tyrolean Inn Valley. (No longer available online.) In: zdf.de. ZDFinfo , May 25, 2015, archived from the original on July 13, 2015 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ A look at the community of Schwaz . Statistics Austria. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ↑ Pronunciation: [ s̠wates̠ ], roughly between “Suátes” and “Shuátesch” in modern script.

- ↑ Martin Bitschnau , Hannes Obermair : Tiroler Urkundenbuch, II. Department: The documents on the history of the Inn, Eisack and Pustertal valleys . tape 1 : By 1140 . Universitätsverlag Wagner, Innsbruck 2009, ISBN 978-3-7030-0469-8 , p. 104-105 .

- ↑ Schwaz - the city of culture. In: schwaz.at, accessed on October 23, 2017.

- ↑ Alexander Sarlay: Copper for the world. In: netzwerktirol.at, accessed on January 20, 2020.

- ^ Richard Ehrenberg : The age of the Fugger. Money capital and credit transactions in the 16th century. Volume 1: The Money Powers of the 16th Century. Gustav Fischer, Jena 1896; Reprint: Georg Olms, Hildesheim u. a. 1922; Digitized: ibid. 1990, ISBN 3-487-40062-6 ( preview in Google book search).

- ↑ Georg Burckhard: A until now unknown medical writer of the 16th century (Dr. Johannes Milchtaler from Schwaz). In: Sudhoff's archive . Volume 4, Issue 1 (May 1911), ISSN 2191-3889 , pp. 20-30, JSTOR 20772894 .

- ^ History. In: silberbergwerk.at, accessed on October 23, 2017.

- ↑ a b Uli Jung: Reformation City Schwaz. Austria. Miners, Anabaptists and Hutterites. In: reformation-cities.org/cities, accessed on February 28, 2018.

- ↑ Viktoria Waldegger: Chronicle. Schwaz escaped catastrophe 20 years ago. In 1999, huge pieces of rock fell from the Schwazer Eiblschrofen into the valley. 300 people had to be evacuated for weeks. The mountain is still in motion today, but the residents feel safe thanks to the protective structures. In: tirol.orf.at, July 9, 2019, accessed on July 19, 2019.

- ↑ Pflanzgarten u. Silberwald. In: schwaz.at, accessed on July 19, 2019.

- ↑ 100th European city of the Reformation: Schwaz in Tirol. In: reformation-cities.org, December 20, 2017, accessed on February 12, 2020.

- ↑ Schwaz becomes a fair trade city. In: Kommunal.at, August 30, 2017, accessed on May 28, 2019.

- ↑ Hobby Club Schwaz (fitness, outdoor activities, hobby football). In: hcschwaz.at, accessed on February 12, 2020.

- ↑ Ernst Brandl and the Penicillin V. In: Tiroler Tageszeitung . May 31, 2019, accessed June 13, 2019.

- ^ Roderick Miller: Kematen Forced Labor Camp (Messerschmitt Tunnels). In: Frank Falla Archive, accessed June 13, 2019.

- ^ Günther Berghofer honorary citizen of the city of Schwaz. In: adler-lacke.com, September 22, 2017, accessed on June 13, 2019.