baptist

Baptist (formerly Anabaptists or Anabaptists are called) supporters of a radikalreformatorisch - Christian movement that emerged after 1520 in the German- and Dutch-speaking parts of Europe and to the left wing of the Reformation is expected.

In German-speaking countries, Anabaptism is mostly perceived as a historical phenomenon of the Reformation period, because apart from the Mennonites, Anabaptists disappeared from German-speaking countries through persecution and assimilation pressure. But Anabaptist churches today have millions of followers around the world, with traditional Anabaptist groups such as the Amish , Old Colonial Mennonites , Old Order Mennonites , and Hutterites among the fastest growing Christian communities.

Important concepts of the Anabaptists are following Christ , the Church as brotherhood and non-violence. They base their thinking and behavior entirely on the literal interpretation of the New Testament ( sola scriptura ), which is also expressed in their understanding of the sacrament ( baptism of believers , Lord's Supper ). In addition, there are demands for freedom of belief , for separation of church and state , partly for community of goods (Hutterites) and for isolation from the world. The concepts and beliefs and practices mentioned are differently pronounced and accentuated in the individual groups of the Anabaptist movement. Overall, the Anabaptist movement was exposed to severe persecution by the authorities and the official churches , especially in the first two centuries of its existence .

Today's Anabaptists are the Mennonites , the Amish and the Hutterites . The younger Anabaptist currents include the Pietist- Anabaptist Mennonite Brethren and the Bruderhöfer . The Anabaptists in the broader sense include the Schwarzenau Brothers , the Federation of Evangelical Anabaptist Congregations (ETG, also Evangelical Baptists or New Baptists ) and the River Brethren . Although there are also individual points of contact with free churches that emerged later, such as the Baptists , these are not to be assigned to the Anabaptists in a denominational sense.

Terminology

The term Anabaptist has established itself in the German-speaking area since the middle of the 20th century as a name for the radical Reformation groups, whose most prominent feature was the rejection of infant baptism . They justified their demand for the baptism of believers with the fact that baptism presupposed an active, personal confession of faith.

The discrediting term “Anabaptist” (derived from the Greek anabaptista ) dates back to the Reformation. From the point of view of the opponents, the Anabaptists baptized people who had already been baptized as infants a second time. But since infant baptism was therefore to be regarded as unbiblical and invalid for the Baptist, the accomplished of them baptism was not in her eyes re but a Ersttaufe . The Anabaptist movement therefore rejected the term Anabaptists as pejorative from the start. In their early years they called themselves, among other things, brothers in Christ and God's church .

Already in the middle of the 18th century Johann Conrad Füßlin was of the opinion that "the hated name Anabaptists was wrongly assigned". In today's literature, the polemically charged term is mostly dispensed with and the impartial term Anabaptist is used. Sometimes the Anabaptist groups are also referred to as part of the radical Reformation.

In the English-speaking world, the term Anabaptists (literally "Anabaptists") has remained to this day in order to be able to distinguish linguistically between the Anabaptists who emerged during the Reformation and the members of the later Baptists ( Baptists , literally "Anabaptists").

Emergence

In the older Anabaptist research, a monogenesis was assumed with regard to the origin of the Anabaptist movement . According to this, the Anabaptist movement would have had its sole beginning in Reformation Zurich under former companions of Huldrych Zwingli such as Konrad Grebel , Felix Manz and Jörg Blaurock , and from there on different paths first in Switzerland and then in southern Germany and Austria and later also in the Dutch widespread in northern Germany. After 1960 the idea of a polygenesis took hold , according to which three main roots of Anabaptism can be identified:

- in the Zurich Reformation with Grebel, Manz and Balthasar Hubmaier

- in the radical Reformation around Karlstadt and Thomas Müntzer with the apocalyptic Hans Hut in Upper Germany (see e.g. the role of the Zwickau prophets )

- in the spiritualistic end-time milieu of Strasbourg, from where Anabaptism was brought into the Low German region via Melchior Hofmann .

In the meantime, the polygenetic approach has also been further developed in some points, for example by emphasizing and researching the relationships and interactions between the individual groups. Accordingly, the beginning of the Anabaptist movement, beginning with publicly disseminated criticism of infant baptism, can be set in 1521, similar to the beginning of the Reformation in 1517, without reformatory concerns already being implemented that year. In both cases, however, a movement began that gradually led to visible consequences in the years that followed.

Within a few years, the Anabaptist movement developed into an important branch of the Reformation throughout Central Europe, despite massive state and church persecution. The prerequisites for all groups of Anabaptists were similar: those described as “radical reformers” were disappointed with the progress of the Reformation . They demanded the "immediate establishment of a state-free Protestant church based on the model of the New Testament ". Their ideal was a free church based on the early Christian model, a "community of believers" based on the free will of the individual parishioners. Therefore, they rejected infant baptism , for which they understand there was no evidence in the New Testament scriptures. They baptized only those that the baptism coveted personally, and took only people in their communities, which as believers had been baptized. Other central aspects of the Anabaptist movement were, among other things , the autonomy of the congregation, the priesthood of all believers , the refusal of the oath and the symbolic understanding of the Lord's Supper. Social aspects also played a role. However, the characteristics of the various Anabaptist groups can by no means be described as uniform.

Radical beginnings in Zurich

An important branch of the Anabaptist movement emerged in Zurich , initially as an ally, later as a split from the Reformation initiated and carried out there by Zwingli: the reform of the church did not go far enough for the so-called “founding fathers” of the Anabaptist movement in the Zwingli area. They belonged to Andreas Castelberger's Bible study group. These proto-baptizers acted as catalysts of the imperative Reformation. They made themselves felt with radical actions such as breaking the fast, disrupting the preaching, and iconoclasm . At the same time, clergymen were active in some rural communities who demanded more radical measures and also supported the farmers in their social demands. Simon Stumpf in Höngg and Wilhelm Reublin in Witikon were particularly active . The question of baptism was not yet central at this point. In the course of the second Zurich disputation in autumn 1523, there was a break between the later Anabaptists and Zwingli. For a group around Simon Stumpf and Konrad Grebel, the Reformation process was not thorough enough. She demanded the immediate abolition of the fair and the removal of the pictures. However, Zwingli wanted to leave it to the city council to determine the time and the procedure for the establishment of the new order.

In the spring of 1524, the preachers in some rural communities openly called for the refusal to baptize infants. The city council of Zurich thereupon issued an order on August 11, 1524 to have all children baptized: Eß söllent ouch angentz those who have unpuffed children, let them potty, and who shouldn't do that, the 1 March silver should be added . The circle around Manz and Grebel opposed this order. The question of baptism now assumed a central position in the dispute with Zwingli. One made contact with other reformers like Karlstadt and Thomas Müntzer by letter , which was at the same time a kind of self-reflection. At the end of 1524, in the so-called two Tuesday talks between Zwingli and the circle around Grebel and Manz, another attempt at an understanding was made. The discussions were inconclusive, so Felix Mantz wanted to put his baptismal views in writing. To this end, he wrote the protest and protective letter , a letter of defense to the city council. Mantz defended himself against the accusation of rebellion and demanded a written discussion with Zwingli, in which the child baptism should be checked for its biblical justification.

On January 17, 1525, the council then invited representatives from both sides to a public disputation in the town hall of Zurich, so that both groups could justify their doctrine of baptism on the basis of the scriptures. However, the outcome in favor of Zwingli was already given. On January 18, the Zurich council issued a damning mandate against the Anabaptists. All those who refused to be baptized were urged to have their newborn children baptized immediately. Anyone who does not comply with this request within eight days will be expelled from the country. The baptismal font that was removed from the church in Zollikon was to be set up again immediately. In a second mandate on January 21, 1525, the verdict was tightened. Grebel and Mantz were forbidden from any further agitation against child baptism and teaching in their Bible schools ( special schools ) was banned, which amounted to a de facto ban against child baptism from meeting. The non- Zurich Anabaptists (among them: Reublin, Brötli , Castelberger and Hätzer ; Simon Stumpf had been expelled earlier) were asked to leave the Zurich area within eight days. The decision was final; a further disputation was excluded.

First parishes

Grebel and Manz ignored the ban and continued to gather their followers to study the Bible together . On the evening of January 21, 1525, the Grebel circle met in the house of Felix Manz's mother. In the oldest chronicle of the Hutterite brothers , the Great History Book , there is an account of the course of this meeting. The chronicle reports that "fear began and came upon them" and "that their hearts were afflicted". After a prayer , the former Roman Catholic priest Jörg Blaurock from what is now Graubünden came before Konrad Grebel and asked him to baptize him. Grebel immediately complied with this request. Thereafter, at their request, Blaurock also baptized the others in the circle - including Felix Manz. This baptism is still considered to be the founding act of the Anabaptist movement. To commemorate this date, the Mennonite World Conference calls the Anabaptist congregations annually to a World Fellowship Sunday around January 21st.

The baptism of believers carried out in the circle around Grebel and Manz did not remain secret. The repression by the Zurich city council meant that Grebel, Manz and Blaurock fled to Zollikon in the Zurich area. Johannes Brötli, who had to leave Zurich after the disputation on January 17, had already taken up his temporary residence here and spread Anabaptist ideas among the population.

Immediately after his arrival, Jörg Blaurock began to preach in an evangelistic manner in the Zollikon farms . The proclamation quickly triggered a movement of penance among the inhabitants , as a result of which Blaurock baptized a large number of the awakened . Back and forth in the houses of Zollikon after the baptismal acts, the Lord's Supper was celebrated in "apostolic adornment" ( Fritz Blanke ). The fathers of the house read the New Testament texts from the Lord's Supper in the living room and handed bread and wine to the participants in their house meetings. While in “reformed” Zurich, following a council resolution, the evangelical Lord's Supper was not approved until Easter 1525, the Zollikon Anabaptists had already radically separated from the Roman Catholic tradition months earlier. After they had already opposed the decisions of the authorities through their baptisms, they now denied the state the right to decide on spiritual matters a second time with their "evangelical" Lord's Supper celebrations. Thus - according to Fritz Blanke - the first Protestant free church appeared in Zollikon in 1525.

On January 30, 1525, the Zurich council sent town servants to Zollikon and temporarily arrested those who were baptized and Anabaptists. While Felix Manz had to remain in prison until autumn 1525, the Zolliker farmers as well as Grebel, Blaurock, Brötli and Wilhelm Reublin were released. Reublin went to Waldshut , where he was able to win over pastor Balthasar Hubmaier, who had already converted to the Lutheran Reformation, and his congregation for Anabaptism. Brötli emigrated to Hallau in the canton of Schaffhausen and founded an Anabaptist congregation there that same year. Blaurock and Grebel turned to the Zurich Oberland and gained a large following there through their sermon. The success of the missionary work increased when Felix Manz joined them after his release.

Blaurock, Grebel and Manz were arrested again. Zwingli tried to persuade her to withdraw in various conversations, but neither he nor the torturers succeeded in the so-called embarrassing interrogations . While Grebel and Blaurock were released with the help of influential friends, Manz remained in custody and was drowned in the Limmat in Zurich in the first days of January 1527 .

The Anabaptists' sense of mission was strengthened by the persecutions, in which they saw confirmation of their path. They continued to teach their Anabaptist ecclesiology in the Zürcher Land and “set up the sign of baptism” - both in St. Gallen and in Eastern Switzerland. The Anabaptist movement spread to Basel as well. By publishing numerous writings, Hubmaier ensured the broad dissemination of radical Reformation ideas. Johann Groß, a pupil of Hubmaier, did missionary work as an Anabaptist emissary in the region around Bern . Reublin and Michael Sattler , who also joined the Anabaptist movement early on and later made a name for himself among other things as the author of the so-called Schleitheimer Articles , brought Anabaptism to southwest Germany. Jörg Blaurock initiated the founding of Anabaptist parishes in Graubünden and Tyrol .

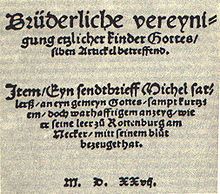

Schleitheim article

After the failure of the peasant uprising , the Anabaptist movement lost a large part of the mass base. This, as well as the increasing repression from the outside and the confusion within, were reasons for a self-reflection, which led some of the Anabaptists in the path to isolation . For the Anabaptists around Sattler and Reublin, who had found refuge in tolerant Strasbourg, this segregation led to their expulsion at the beginning of 1527, as the Strasbourg Council generally tolerated differing theological views - the trial of Thomas Saltzmann is an exception - but not civil disobedience such as the refusal to participate in the fortification work, to which all citizens were obliged, on the grounds that no government could be Christian.

On February 24, 1527, a "brotherly association" of Anabaptists met in Schleitheim (near Schaffhausen ) under the direction of Michael Sattler. At this meeting a first fully formulated programmatic confession of the Anabaptists was written. This book, the so-called Schleitheim Articles , lists the most important principles of Anabaptism in seven points:

- Baptism of believers (rejection of infant baptism)

- Church discipline ( ban in the event of misconduct)

- Breaking bread (Lord's Supper) as a sign of community

- Isolation from the "world"

- Free choice of shepherd / pastor

- Refusal of military service

- Refusal to take the oath

With the Schleitheim articles, the Social Revolutionary took a back seat to the religious component. At the same time, they were an expression of a move away from a popular church movement towards a minority free church.

The Schleitheim articles were also the subject of the synod that took place in Augsburg in August 1527 . Sattler's theses, which were defended by the Waldshut Baptist Jakob Gross , could not prevail here, however. Because many of those present at this Synod of Anabaptists were executed shortly afterwards, this meeting is also known as the Augsburg Synod of Martyrs .

Spread from 1525 to 1530

After the Swiss beginnings in 1525/26, the Anabaptist teachings spread “extremely rapidly” in Central Europe within the first five years and were perceived by many contemporary chroniclers - alongside the Lutheran and Zwinglischen - as the third “powerful” Reformation movement. There are estimates that after 1530, a third of the population in Germany was Catholic, Lutheran and Anabaptist.

As early as the spring of 1526, Anabaptists can be found in the Tyrolean Inn Valley and around the same time in the area around Horb and Rottenburg am Neckar . Jörg Ziegler, baptized by Reublin, founded the first Anabaptist congregation in 1526 in Strasbourg, where reports of the refusal of infant baptism are known as early as 1524. The first traces of the Anabaptists are also recorded for Augsburg at this time. In the summer of the same year, Anabaptist messengers evangelized in Moravia .

The expansion of Anabaptism experienced a particular boom in 1527. In the spring, Lower and Upper Austria were recorded. In southern Germany, communities in Nuremberg , Erlangen , Regensburg , Memmingen , Munich , Esslingen and Schwäbisch Gmünd emerged in the course of the year . In the same year the Anabaptist movement began to spread in Silesia. When the Anabaptists gained a foothold in Tyrol at the end of 1527, King Ferdinand wrote to the authorities there that “such a kind of fire” should be met with all determination. Anabaptist communities arose in the Duchy of Württemberg at the beginning of 1528. In mid-1528 there was an Anabaptist awakening in the Hessian town of Sorga , which radiated into the core areas of the Lutheran Reformation. It is therefore not surprising that the Diet of Speyer dealt intensively with the growth of this movement in 1529 and decided to take countermeasures. The former Lutheran messenger and later apocalyptic preacher Melchior Hofmann , who came into contact with Anabaptism in Strasbourg in 1530, proclaimed baptism in the Netherlands as a sign of the commitment of the believing soul to God and baptized 300 people in Emden . Afterwards religious refugees carried the Anabaptist teachings to Prussia and even to England . Thousands - according to the chronicler Sebastian Franck already mentioned in 1531 - accepted the baptism and covered the whole country.

Persecution and Martyrdom of the Anabaptists

The persecutions and executions that began soon after the Anabaptist movement began to flourish stand in curious contradiction to the positive testimony given to the conduct of the Anabaptists themselves by their most determined opponents. Thus Zwingli wrote in his pamphlet against the Anabaptists in 1527: "Even those who tend to criticize [add .: of the Anabaptists ] will testify that their life is excellent." Heinrich Bullinger , Swiss reformer and head of the Zurich Church, confessed in his writing about the impudent fräfel (1531), condemning the Anabaptists : "They (add .: the Anabaptists ) reject greed, pride, godlessness, indecent speech and worldly immorality, drinking and gluttony." The Strasbourg reformer Wolfgang Capito formulated it in view of the Swiss Brothers in 1527 as follows: “I must openly confess that most (add .: Anabaptists ) show piety and devotion and indeed a zeal that is above any suspicion of insincerity. For what earthly gain could they hope for by enduring exile, torture and inexpressible corporal punishment. I testify before God that I cannot claim that they are somehow indifferent to earthly life for lack of wisdom, but because of the divine spirit alone they are. "The Catholic theologian Franz Agricola attested the Anabaptist movement in 1582 :" The Anabaptists, As far as external and public change is concerned, a very honorable life is felt in which no lies, deceit, swearing [...], no pride , but humility, patience, loyalty, meekness, truth [...] and all kinds of sincerity and is heard, so that one should think that they have St. Spirit of God. ”The following anecdote is also instructive in view of the contemporary assessments of the Anabaptist way of life. Caspar Zacher from Waiblingen in Württemberg was accused of being an Anabaptist in 1562. The court record, however, stated to Zacher's relief that he was a jealous man who couldn't get along with anyone and who often started arguments, including swearing, cursing and carrying arms (sic!). He could therefore not be an Anabaptist.

These selected testimonies from opposing contemporaries lead to the question of why the Anabaptists were accused of "rebellion" and therefore persecuted so vehemently by the state and the churches.

Reasons of persecution

In superficial representations, the connections between Anabaptists and the peasant revolts (from 1524) are mentioned again and again and the persecutions are justified with them. Such relationships existed. For example, Johannes Brötli and the Hallau Anabaptist community briefly connected with the rebellious farmers. The vast majority of Anabaptists distanced themselves from the “use of the sword” from the start. Konrad Grebel wrote to Thomas Müntzer five months before the Zurich congregation was founded : “Beyond that, the gospel and its followers cannot be protected by the sword, nor should they [protect] themselves, which, like us, should be protected by our brother heard you think you have to do it. Truly believing Christians are sheep among wolves, sheep for slaughter. They must be baptized through fear, distress and persecution, through suffering and death, refined in fire, […] They do not use the worldly sword, nor war, nor killing. That has completely stopped with them, unless they are still under the old law . "The Schleitheimer Articles (1527) also reject the use of weapons:" So we are now also questioning the unchristian and devilish weapons of violence when they are there Sword, harness and the like and all other uses for friends or against the enemy in the power of the word of Christ. Ir should not resist the evil. "

The main reason for the persecution of the Anabaptists was neither their way of life nor their attitude towards the actual uprising and resistance movements of the 16th century, but their fundamental attitude towards secular authorities. Since the Anabaptists refused to take the oath with reference to the Sermon on the Mount ( Mt 5,33-37 LUT ), most Anabaptists refused to take the oath of fief or obedience to the authorities that was customary at the time . Also the widespread attitude of the Anabaptists that true Christians are not allowed to act as judges, soldiers or executioners because of the Christian renunciation of violence ( Mt 5: 38-52 LUT ), and not even to exercise any public office, because ultimately every public, secular office connected with the threat or execution of any kind of violence (e.g. judicial and police punishments) made it suspect in the eyes of both the old believers (Catholic) and the Lutheran and Reformed authorities and theologians, at least in principle the overthrow of the ruling class To strive for relationships - even if most Anabaptists demonstrably led a completely passive and withdrawn life. The involvement of individual Anabaptist theologians in the Peasants' War and the Anabaptist Empire of Munster brought the whole, very heterogeneous Anabaptist movement under general suspicion .

The so-called Anabaptist mandate

The Diet of Speyer in 1529 (Speyer II) was on the one hand a milestone on the way to modern freedom of conscience. The 19 Protestant imperial estates were able to politically enforce their religious freedom of conscience. On the other hand, however, a mandate was passed calling for the death penalty against the Anabaptists under imperial law. While the Lutheran Reformation enjoyed strong support from the German princes, the Reformation Anabaptists were not represented by any of the imperial estates . The so-called Anabaptist Mandate of Speyer created the legal basis for a large-scale persecution of the Anabaptist movement; it had the following content:

- Anyone who has been rebaptized or undergone rebaptism , whether man or woman, is to be punished with death without a spiritual inquisition court having to act beforehand.

- Whoever revokes his confession to the Anabaptists and is ready to atone for his error should be pardoned. However, he must not be given the opportunity to evade constant supervision by being instructed to move to another territory and possibly relapse. Persistence in insisting on Anabaptist teachings is to be punished with death.

- Anyone who leads the Anabaptists or promotes their instructions should not be pardoned “by no means”, even if withdrawn.

- Anyone who has relapsed after a first revocation and revokes it again should no longer be pardoned. He is the full punishment.

- Those who refuse to be baptized for their newborn children also fall under the penalty of rebaptism.

- Anyone who escaped from the Anabaptists to another territory should be persecuted there and punished.

- Those of the officials who are not prepared to act strictly according to these orders must expect imperial disgrace and severe punishment.

The application of the mandate was handled very differently. Many Anabaptist congregations came under massive pressure, torture (during interrogation) and the use of the death penalty are documented from both Catholic and Protestant territories. On the other hand, numerous Evangelical Lutheran theologians rejected the strict application of the mandate, especially the imposition of the death penalty. Influential reformers such as B. Martin Bucer and Johannes Brenz , in reports, for which they were often asked by many Protestant princes and city councilors, mostly in favor of expelling unruly Anabaptists. So z. B. in the visitation regulations of the Duchy of Württemberg from 1557 expressly not referred to the imperial Anabaptist mandate, which has been renewed several times in the meantime. “Anabaptists” are divided into two groups (“Urourian or nit”), of which only the former should be expelled from the country, while the members of the second group were even tolerated with the promise of absolute restraint.

Extent of persecution

About 1000 named Anabaptists died in the 16th and 17th centuries because of their beliefs. Of these, about 800 names can be found in the Mennonite Martyrs Mirror alone . The history book of the Hutterite Brothers describes many individual fates of Anabaptist martyrs on around 670 pages. Anabaptist research assumes that the documented number of victims must be at least doubled. But even that does not describe the full extent of the persecution. Anabaptists were deprived of their property, expelled, and sold into slavery . In addition to the state authorities, the Roman Catholic Church , the Lutheran and the Reformed clergy were involved in the persecution . The persecution of the Swiss Anabaptists was particularly long-lasting. The Reformed cities of Zurich and Bern still used the galley penalty, which in most cases ended in death, in the 17th century . In 1699, the city of Bern set up a special Anabaptist Chamber to coordinate the persecution and administer the property of the Anabaptists who fled or expelled ( see the main article, History of Bernese Anabaptism ). Special Anabaptist hunters were active in order to locate and arrest the Swiss Anabaptists. As early as 1709, around 500 people are said to have been expelled from Switzerland as a result of the Bern Council with the help of the Anabaptist Chamber. Almost 25 percent of the executions in the Protestant territories of the empire took place in Electoral Saxony . As early as 1531, Philipp Melanchthon had spoken out in favor of the death penalty for rebellious Anabaptists. In the Netherlands, too, many Anabaptists were burned at the stake .

In the Archdiocese of Salzburg it became known on April 23, 1523 that in addition to the followers of Luther there were also Anabaptists in Salzburg. It was believed that its founder was Hans Hut . A congregation of 32 Anabaptists was found. Of them three were burned, five were executed by the sword, one woman and a sixteen-year-old girl were drowned. Four days later four Anabaptists were again led to the stake, four revocators beheaded and five burned along with the meeting house, including a clergyman. The surviving Anabaptists went to Tyrol. In 1538, numerous Anabaptists expelled from Moravia were imprisoned in the dungeons of Falkenstein Castle in the Weinviertel region . The women and children were soon released, while the men in Trieste came to Habsburg galleys.

The Anabaptist researcher Wolfgang Krauss speaks of an "ecclesiocide" with regard to the extent of the martyrdom suffered by the Anabaptists.

In some territories, anti-Anabaptist laws were not consistently applied strictly. Members of the Anabaptist congregations who were not ready to revoke were expelled from the country or a tolerance was given, provided that the Anabaptists gathered in silence and refrained from missionary activities. Under the Hessian Landgrave Philipp I , a Lutheran, the death penalty was not used despite threats.

On the occasion of the Anabaptist Year 2007 , representatives of the Reformed Church of Switzerland asked the descendants of the Anabaptist movement for forgiveness. At a penance service in Stuttgart (July 2010), the Lutheran World Federation also made a comprehensive confession of guilt to representatives of the Reformation Anabaptist movement.

The different directions of the Anabaptist movement

In recent research on church history, Anabaptism is often referred to as the left wing of the Reformation or as the radical Reformation movement . Behind these terms is the attempt to give a common name to a movement from different directions. On the one hand, it becomes clear that it “deserves” a common name if one looks at the strong internal networking of the various Anabaptist communities. On the other hand, they also deserve a common name because, in addition to the strict rejection of infant baptism, they also essentially coincided in other points of view. This included the readiness to follow Jesus radically , the intended restoration of the church as a brotherhood of believers without the development of a special clerical status, the rejection of the oath, the view of the Lord's Supper as a memorial meal and the demand for the separation of state and church. In addition to the common views, different views in the field of doctrine and ethics developed in different Anabaptist circles. There have been a number of attempts to build bridges between the different camps; there was also no lack of meetings, writings, declarations of convergence and leading personalities who were struggling for unity. However, they could do little to counter the centrifugal forces within the Anabaptist movement. In addition, there were persecutions and the associated migrations, which blocked the orderly development of an Anabaptist church network. In any case, the Anabaptists rejected an office superordinate to the local congregation and the establishment of a church hierarchy for reasons of principle.

The first differentiations between the various currents of Anabaptism took place as early as the Reformation. For example, an extensive questionnaire that was used in the Duchy of Württemberg from 1536 as an aid during Anabaptist interrogations said, among other things:

"Item wölcher sect of widertouffer [he] seye if he where to munster or those in mers or appendages others?"

A distinction was made, for example, between Melchiorites (after Melchior Hofmann ), Hutterites (after Jakob Hutter ), Huterian or Huterites (after Hans Hut ), Bilgramites (after Pilgram Marbeck ) and Men (n) ists or Mennonites (after Menno Simons ). The division into Stäbler and Schwertler was also common early on. The Anabaptists themselves also distinguished themselves from one another. Balthasar Hubmaier wrote that the baptismal doctrine he advocated differs from Hut's conceptions “like heaven and earth, east and west, Christ and Belial ”. In today's Anabaptist research, four or five main currents are generally assumed.

Swiss brothers

The Swiss brothers were derived directly from the first Anabaptist community in Zurich, spread to Switzerland, the Upper Rhine, Kraichgau and the Electoral Palatinate , and particularly advocated the idea of "isolation from the world". The Amish split off from the Anabaptists and Mennonites in Switzerland and Alsace in 1693 . The congregations that still exist in Switzerland today are united in the Conference of the Mennonites of Switzerland (Old Anabaptists) . Many Mennonite communities outside of Switzerland, for example in (southern) Germany, the USA and Canada , emerged from the emigration of Swiss Mennonites.

South and Central German Anabaptists

The South German Anabaptists formed their communities in Swabia , Bavaria , Franconia and Austria and were a strongly evangelical Anabaptist group. Their theology was eschatological and partly also spiritualistic . From the Franconian Königsberg , the movement also spread to the Central German regions such as Hesse and Thuringia as far as the Harz Mountains . An important special group within the South German Anabaptist movement formed the municipalities of by Pilgram Marpeck named Marbeck circle . During the Thirty Years War, the South German Anabaptist communities were largely wiped out.

Moravian Anabaptists

Many Anabaptists emigrated to Moravia early on. The first center of the Anabaptist movement was the town of Nikolsburg , where disputes over the legitimacy of defense broke out in 1526, whereupon the early Moravian Anabaptists split up into the groups of swordsmen and pacifist stabbers . From the latter group the first communitarian Anabaptist congregation arose in Austerlitz in 1528 . A short time later, part of the Austerlitz community migrated to Auspitz and became the nucleus of the Hutterites named after Jakob Hutter . In addition to the Hutterites, there were other smaller Anabaptist groups in Moravia in the 16th century, such as the Gabriels , the Philippians , the Sabbath- keeping Sabbaths and the Austerlitz brothers, who later belonged to the Marbeck district .

The dominant tendency among the Moravian Anabaptists was soon formed by the Hutterites, who mainly consisted of Anabaptists who had fled to Moravia from South Tyrol . Until the beginning of the Thirty Years' War the Hutterite parish life flourished and numerous new brother farms could be founded. Hutterite missionaries promoted the Hutterite parish model as far as Switzerland. Important representatives such as Peter Rideman and Kaspar Braitmichel consolidated the community internally. With the Thirty Years War, however, a renewed period of persecution began, which took the Hutterites over several centuries via Slovakia, Transylvania and Russia to North America, where the Hutterites now live in over 450 colonies. To this day, the Hutterite practice of faith is characterized by community of property, non-violence , the idea of "isolation from the world" and a narrow ethic .

North German-Dutch Anabaptists

The Low German Anabaptists, also called Melchiorites , go back above all to the effectiveness of the former Lutheran messenger and later Anabaptist chiliast Melchior Hofmann . The center of his mission was the East Frisian city of Emden , in whose large church he baptized around 300 people at the beginning of June 1530 . Anabaptist groups such as the Münster Anabaptists , the Davidjorists and the Mennonites emerged from his work .

Munster Anabaptists

The Münster Anabaptists played a special role within the Anabaptist movement, and Melchior Hofmann is considered to be their indirect theological pioneer. The apocalyptic- chiliastic message of his writings fell on fertile ground with some of the Anabaptists. After the end of the world announced by Hofmann for 1533 had not occurred, Jan Matthys preached the use of the sword against the godless authorities. Under “ Anabaptist King” Jan van Leiden, the Anabaptist empire of Munster deteriorated so much that Catholic and Protestant princes destroyed it through a cruel city siege. After the decline of the Anabaptist Empire, the surviving Munster Anabaptists rose up in other Anabaptist groups or returned to the Evangelical Church. Only a minority under Jan van Batenburg tried for a short time by using force to bring about Judgment Day by exterminating the wicked.

Mennonites

The Mennonites , named after the theologian Menno Simons , developed out of the Dutch-North German Anabaptist movement originally brought into being by Melchior Hofmann . While the Melchiorites were originally shaped by apocalyptic near expectation and their communities were hierarchically structured under prophetic leaders, after 1535 a part of the movement expressly distanced itself from the Münster Anabaptists and consciously followed the tradition of the non-violent Anabaptists (" Stäbler ").

Characteristic of the early Mennonites was, among other things, their strict pacifism and the refusal to take the oath. In the first few years of their existence, they were particularly widespread in the Netherlands (including Flanders ), in East Frisia and on the Lower Rhine . Many later moved to the Danzig area . In some cases, urban communities such as in Altona and Friedrichstadt also emerged .

From around 1789 to 1860, a significant part of the Mennonites from the Danzig area and the Vistula Delta emigrated to the Ukraine , which was then part of the Russian Empire and later to other parts of the Russian Empire. These German-speaking ( Plautdietsch ) Mennonites multiplied strongly in Russia.

In the years after 1874 the more conservative part, around a third, emigrated to the USA and Canada . After the victory of the communists in 1917, further waves of emigration followed, especially in the 1920s to Canada and at the end of World War II with the retreat of the German army to the west and from there mostly to North and South America.

In the 1920s, the most conservative element of the Russian mennonites in Canada emigrated, mainly to Mexico, as well as to Paraguay and later to other Latin American countries. Most of the Mennonites of Dutch-North German descent (over 250,000 people) now live in Latin America.

Due to mission projects, especially more liberal North American Mennonites, there are now large Mennonite congregations in Asia and especially in Africa. Of the populated continents, Africa was home to the most Anabaptists in 2015, namely (736,801), followed by North America (682,559), Asia (430,9793), Central and South America (199,912), Europe (64,610) and Australia (334). The numbers refer to baptized members, children and adolescents, as well as young adults who have not yet decided to be baptized, are not counted.

The majority of the Mennonite communities established in southern Germany and Alsace go back to the Anabaptists who were expelled from Switzerland. Since the 1990s, many people of Russian-Mennonite origin have come to Germany with the Russian-German resettlers. Most of them did not join existing Mennonite congregations , but founded their own Mennonite or Baptist congregations ( Evangelical Christians -Baptists ) or joined a wide variety of free churches, so that today you can find Christians of Russian-Mennonite origin in almost every larger free church in Germany. In addition to Russian mennonites from the former Soviet Union, there are a few thousand Mennonites expelled from West Prussia after 1945 who originally speak the same dialect as the Russian mennonites, and a smaller number of Russian-Mennonite returnees from Latin America.

Another pacifist Anabaptist group that still existed in northern Germany in the 17th century were the David Jorists .

Tabular overview

The following table gives a rough overview of the leading personalities and the doctrinal emphases of the above-mentioned Anabaptist groups. It is based on an overview provided by Dieter Götz Lichdi and, as a supplement, draws a line between the historical Anabaptist groups and today's Anabaptist communities. It should be noted that today there are also a large number of Anabaptist communities without direct genealogy to the historical Anabaptist groups of the Reformation (as in many Mennonite churches in Africa and Asia).

| Anabaptist group | Leading personalities | Teaching focus | Relation to the following reformers | Today's assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swiss brothers | Konrad Grebel, Felix Manz, Jörg Blaurock, Michael Sattler, Wilhelm Reublin | Biblicism, humanism, asceticism, the Reformation as the restoration of the New Testament early church | Ulrich Zwingli, Erasmus of Rotterdam, Waldensian (?) | Mennonites / Anabaptists in Switzerland, southern Germany and France as well as in America (partly as Amish and Mennonites of old order ) |

| South and Central German Anabaptists | Hans Denck, Hans Hut, Pilgram Marbeck, Balthasar Hubmaier | Apocalyptic, spiritualism, evangelical radicalism, anti-clericalism, sanctification | Thomas Müntzer, Ulrich Zwingli, Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt | partly Mennonites, but mostly wiped out during the Thirty Years War |

| Hutterite / Moravian Anabaptists | Jakob Hutter, Peter Riedemann, Peter Walpot | Biblicism, Reformation as the restoration of the New Testament early church, community of property | Ulrich Zwingli, Erasmus from Rotterdam (?) | Hutterites in North America |

| Low German Anabaptists | Melchior Hofmann, Jan Matthijs, Obbe Philips, Dirk Philips, Menno Simons | Spiritualism, apocalyptic, the “pure” church, oligarchy of elders, christological monophysitism | Andreas Bodenstein from Karlstadt, Martin Luther | Mennonites / Baptism-minded / Mennonite Brethren Congregations in the Netherlands, Northern Germany and North, Central and South America ( Russian Mennonites ) |

Further differentiations

The division of the Anabaptist movement into four or five directions can only be vague in view of the variety of convictions and forces at work in it. Heinold Fast , following on from the religious historian Ernst Troeltsch and the Anabaptist researcher John Howard Yoder , proposed another scheme to differentiate between the various movements within the “left wing of the Reformation”. This scheme, which is mainly based on leading personalities of both the Anabaptists and the broader Radical Reformation, distinguishes Anabaptists , spiritualists , enthusiasts and anti-Trinitarians .

The group of actual Anabaptists is then associated with the following names (in alphabetical order):

- Kaspar Braitmichel , Konrad Grebel , Balthasar Hubmaier , Hans Hut , Anneken Jans , Felix Manz , Pilgram Marbeck , Dirk Philips , Michael Sattler , Leupold Scharnschlager , Leonhard Schiemer , Menno Simons and Ulrich Stadler

The spiritualists are represented by the following names:

The following are listed as enthusiasts :

- Melchior Hofmann , Andreas Karlstadt , Thomas Müntzer , ( Obbe Philips ) and Bernhard Rothmann .

For the anti-Trinitarians within the radical Reformation:

presence

For more information on the current Anabaptist denominations see: Mennonites , Hutterites, and Amish

According to the Mennonite World Conference , there were around 1.6 million Anabaptists worldwide in 2009. The number includes Mennonites along with the Brethren in Christ and related church communities.

In 2009, Anabaptists in Europe only made up about four percent of the world's Anabaptist community. Larger Mennonite community associations exist in Germany, Switzerland, France and the Netherlands, among others.

There are almost 300,000 Amish today, plus around 60,000 to 80,000 old-order Mennonites who live similarly to the Amish. The number of Hutterites is given as 40,000 to 50,000 people. Both Amish and Hutterites now live almost exclusively in North America. In North, Central and South America there are around 300,000 Russian mennonites , some of whom still live very traditionally today, similar to the Amish and Mennonites of the old order. In North America, the Bruderhöfer , the radical Pietist Anabaptist Schwarzenau brothers and the followers of Samuel Heinrich Fröhlich are also included among the Anabaptists.

Today there are around 700,000 traditional Anabaptists who hold on to the German language in the form of their respective dialects ( Pennsylvania German , Plautdietsch , Hutterer German , Bern German , Lower Alemannic Alsatian ). High German is used for the Bible and in worship. The number of these traditional Anabaptists is increasing relatively quickly, as very large families are still the rule today.

In July 2010, the General Assembly of the Lutheran World Federation formulated a confession of guilt towards the Anabaptists and asked Mennonite Christians for forgiveness for the brutal persecution in the 16th and 17th centuries. Nevertheless, Lutheran pastors are ordained to this day based on the Augsburg Confession , written by Philipp Melanchthon , in which the Anabaptists are condemned, among other things, for their nonviolence (Article 16 expressly mentions the rejection and condemnation of the pacifist Anabaptists) .

Movie

- Commune of the Blessed in the Lexicon of International Film ( FRG 2005), director: Klaus Stanjek

- In life and beyond life ( Switzerland 2005), directed by Peter von Gunten

- Executioner ( Austria 2005), directed by Simon Aebi

- The Radicals ( USA 1990), directed by Raul V. Carrera, English with subtitles, runs from time to time on Bible TV

- Ursula ( GDR / Switzerland 1978), director: Egon Günther

- King of the Last Days ( BRD 1993), directed by Tom Toelle

literature

- Hans Joachim Hillerbrand: Bibliography of Anabaptism, 1520–1630 . Gütersloh 1962.

- Detailed references in: Goertz (1980), pp. 209-219 and Stayer (TRE 2001), pp. 615-617.

- Peter Hoover: Baptism by Fire. The radical life of the Anabaptists - a provocation . Down to Earth, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-935992-23-7

swell

- Baptist writings

- Felix Mantz: Protestation and protective letter. Zurich 1524/1525.

- Konrad Grebel: Letter to Thomas Münster. Zurich 1524.

- Balthasar Hubmaier: From the Christian baptism of believers. 1525.

- Balthasar Hubmaier: We spoke to Balthasar Huebmörs von Fridberg, Doctors, on Mayster Vlrichs Zwinglens zu Zürich's little christening book from Kindertauf. 1526.

- Balthasar Hubmaier: A form ze baptisms in the water that create in faith. D. Balthasar Hübmair von Budberg. 1527.

- Hans Hut: From the secret of baptism, baide of zaichens and essence, a beginning of a right, true Christian life. 1527.

- Hans Denck: From the were nice etc. 1527.

- Pilgram Marbeck: Clare responsibility for all articles (so now floated by erroneous geysters in writing and verbally) because of the ceremonies of the New Testament ... 1531.

- Peter Riedemann: Accountability of our religion, emptiness and faith, from the brothers as the Hutterites are called. 1540-1541

- Melchior Hoffmann: prophecy usz holy divine written. Of the troubles of this last time. From the heavy hand and tightness of god above all godless being. Of the future of the Turkish Thirannen and all of his appendages. 1529.

- Bernd Rothmann: Confessions of both Sacraments, Doepe vnde Nachtmaele, the Praedicanten tho Munster. 1533.

- Menno Simons: Dat fundament des christelyken empty doer Menno Simons op dat alder corste schreuen. 1539-1540.

- Source collections

- Sources on the history of the Anabaptists. (QGWT)

- Sources on the history of the Anabaptists. (QGT)

- Sources on the history of the Anabaptists in Switzerland. (QGTS)

- Writings against the Anabaptists

- Ulrich Zwingli: About Doctor Balthazars Touffbüchlin, waarhaffte, founded antwurt. Zurich 1525.

- Ulrich Zwingli: About the Touff. From the wide touff and from the children's touff. Zurich 1525.

- Ulrich Zwingli: In catabaptistarum strophas elenchus. Zurich 1527.

- Konrad Schmid: A Christian guess at real hope in God and a warning of the defiant rebellion that God abwyset to the Christian Amplüt zu Grünigen. Zurich 1527.

- Karl Brennwald, Johannes Oecolampadius: instruction of the re-baptism, of the superiority, and of the Eyd, on Carlins N. widertauffers artickel. Basel 1527.

- Martin Luther: A letter from DM Luther from the sneaks and preachers , Wittenberg 1532.

- Jean Calvin: Brieve Instruction pour poor tous bons fideles contre les Erreurs de la secte commune des Anabaptistes. Geneva 1544.

- Heinrich Bullinger The negative origin, Fürgang, Sects, Wäsen, noblemen and common jrer empty articles, also jre foundations and whys are sinful and set up their own churches , Zurich 1560.

- Philipp Melanchthon: Lessons Philip. Melancholy. Against the lesson of the adversaries translated from Latin by Just. Jona. Wittenberg 1528.

Studies

- Fritz Blanke : Brothers in Christ, the history of the oldest Anabaptist community (Zollikon 1525). Zurich 1955, Winterthur 2003, ISBN 3-89490-501-8 .

- Claus-Peter Clasen: The Anabaptists in the Duchy of Württemberg and in neighboring dominions. Stuttgart 1965.

- Claus-Peter Clasen: Anabaptism: a Social History, 1525-1618 Switzerland, Austria, Moravia, South and Central Germany. Ithaca 1972.

- Hans-Jürgen Goertz : The Anabaptists. History and interpretation. Munich 1980, ISBN 3-406-07909-1 .

- Samuel Henri Geiser : The baptismal congregations in the context of general church history. Courgenay 1971.

- Barbara Kink: The Anabaptists in the Landsberg Regional Court 1527/28. St. Ottilien 1997, ISBN 3-88096-887-X .

- Franklin H. Littell : The Anabaptists' Self-Image. 1966.

- Marlies Mattern: Life on the sidelines, women and men in Anabaptism, 1525–1550, a study on everyday history. Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-631-33331-5 .

- Werner O. Packull : The Hutterites in Tyrol. Early Anabaptism in Switzerland, Tyrol and Moravia. Innsbruck 2000, ISBN 3-7030-0351-0 .

- James M. Stayer : The German Peasants' War and Anabaptists community of goods. Montreal 1991, ISBN 0-7735-1182-2 .

- Andrea Strübind : More zealous than Zwingli. The early Anabaptist movement in Switzerland. Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-428-10653-9 .

- Frank-Michael Boeger: The Christian communist movement of the Anabaptists from the beginnings in Zurich in 1525 to the global ethical and moral significance and necessity in our time. Königslutter 2004.

- Karl-Hermann Kauffmann: Michael Sattler - a martyr of Jesus Christ of the Anabaptist movement. Life story including the Schleitheim article Brosamen-Verlag Albstadt, 2010, ISBN 978-3-00-032755-1

Articles and collective publications

-

Harold S. Bender : The Anabaptist Vision. In: Church History. 13/1 (1944), pp. 3-24, and In: Mennonite Quarterly Review. April 1944, XVIII, pp. 67-88. (online at: mcusa-archives.org )

- German translation: The Anabaptist model. In: Guy F. Hershberger (Ed.): Das Anäufertum. Heritage and commitment (= The Churches of the World . Series B. Volume II), Stuttgart 1963, pp. 31–54.

- Richard van Dülmen (ed.): The Anabaptist Empire at Münster 1534–1535 (documents). Munich 1974, ISBN 3-423-04150-1 .

- Heinold Fast (Ed.): The left wing of the Reformation (= classic of Protestantism, vol. 4), Bremen 1962.

- JF Gerhard Goeters : The prehistory of the Anabaptism in Zurich. In: Luise Abramowski, JF Gerhard Goeters; Ernst Bizer (ed.): Studies on the history and theology of the Reformation. Neukirchen-Vluyn 1969, pp. 239-281.

- Hans-Jürgen Goertz (Ed.): Controversial Anabaptists, 1525–1975. New research. Göttingen 1975, ISBN 3-525-55354-4 .

- Hans-Jürgen Goertz (Ed.): Radical Reformers. 21 biographical sketches from Thomas Müntzer to Paracelsus. Munich 1978, ISBN 3-406-06783-2 .

- Guy F. Hershberger (Ed.): The Anabaptism. Heritage and commitment (= Die Kirchen der Welt. Series B. Volume II), Stuttgart 1963 (Engl. The Recovery of the Anabaptist Vision . Scottdale 1957)

- Urs B. Leu, Christian Scheidegger (eds.): The Zurich Anabaptists 1525–1700. Zurich 2007, ISBN 978-3-290-17426-2 .

- Rosa Micus: Balthasar Hubmaier, the Jews and the Anabaptists. About Hubmaier's work in Regensburg and Waldshut. In: Negotiations of the historical association for Upper Palatinate and Regensburg. Vol. 160, 2020, ISSN 0342-2518 , pp. 137-152.

- James M. Stayer, Werner O. Packull; Klaus Deppermann: From Monogenesis to Polygenesis. The historical discussion of Anabaptist origins. In: Mennonite Quarterly Review. 49: 83-121 (1975).

Lexicon entries

- James M. Stayer: Baptist . In: Theological Real Encyclopedia (TRE). Volume 32, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2001, ISBN 3-11-016712-3 , pp. 597-617.

- Hans-Jürgen Goertz: Anabaptist communities (17th to 20th century) . In: Theological Real Encyclopedia (TRE). Volume 32, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2001, ISBN 3-11-016712-3 , pp. 618–623.

- JF Gerhard Goeters: Anabaptists. In: Heinz Brunotte, Otto Weber (ed.): Evangelisches Kirchenlexikon. Ecclesiastical-theological concise dictionary. Göttingen 1958, S./Sp. 1812-1815.

- Hanspeter Jecker: Baptist. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Harold S. Bender, Robert Friedmann, Walter Klaassen: Anabaptism . In: Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online

Fiction

- Luther Blissett , Ulrich Hartmann: Q . Novel. Munich 2002, ISBN 3-492-04218-X .

- Georg Brun: The Augsburg Anabaptists. Historical detective novel. 2004, ISBN 3-7466-1425-2 .

- Friedrich Dürrenmatt : The Anabaptists. A comedy in two parts. 1967 (most recently: Zurich 1998, ISBN 3-257-23050-8 ).

- Alfred Fankhauser : The Brothers of the Flame. Zurich 1925 (most recently: Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-518-40269-2 ).

- Gottfried Keller : Ursula . In: Ders .: Zurich Novellas . 1878 (most recently: Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-618-68040-6 , pp. 654-717).

- Friedrich Reck-Malleczewen : Bockelson. Story of a mass madness. Berlin 1937.

- Nicholas Salaman: The Garden of Earthly Delights. A novel from the time of the Anabaptists. Diogenes, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-257-06073-4 .

- Robert Schneider : Kristus. Novel. Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-351-03013-4 .

- Rosemarie Schuder : The enlightened. From poor Lazarus to Munster in Westphalia. Berlin 1968 (last: Rostock 2004, ISBN 3-89954-054-9 ).

- Katharina Zimmermann : The castle. Novel. Bern 2001, ISBN 3-7296-0321-3 .

Web links

- Hans-Jürgen Goertz: Anabaptist / Anabaptist movements. In: Mennonite Lexicon . Volume 5 (MennLex 5).

- Astrid von Schlachta : Anabaptist communities: The Hutterites. In: European History Online . ed. from the Institute for European History (Mainz) , April 27, 2011 .

- Peter von Gunten: In life and beyond. CINOV Filmproduktion, 2005, archived from the original on February 14, 2005 (documentary).

- Peter Hoover: The Secret of the Strength: What Would the Anabaptists Tell This Generation? (pdf, 758 kB) God's Word, January 28, 2006, accessed on May 12, 2018 .

- Carsten Fischer: The Anabaptists in Münster (1534/35) - law and constitution of a chiliastic theocracy -. In: forum historiae iuris. August 12, 2004, archived from the original on September 11, 2017 .

- Rolf Christoph Strasser: Die Zürcher Anabapters 1525. Verlag der Evangelische Fernbibliothek, Wetzikon, 2006, accessed on May 12, 2018 .

- Rolf Strasser: Münster-Anabaptist 1534–1535: The short-lived Anabaptist city-state in Westphalia and its catastrophic end. EFB text archive, August 22, 2011 .

- Anabaptist story. In: taeufergeschichte.net. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016 .

- The Anabaptists. Down to Earth Verlag, archived from the original on January 11, 2016 (texts, books and links).

- The Anabaptists' attempt to establish the kingdom of God in Munster. Gk Religion Jgst 11 of the Lessing School Bochum, archived from the original on March 29, 2004 (school project).

- Baptist Museum. Museum village of Niedersulz

Individual references and comments

- ↑ This term goes back to Roland H. Bainton: The Left Wing of the Reformation. In: The Journal of Religion. Vol. 21, No. 2-1941, pp. 124-134. Compare with Heinold Fast (Ed.): The left wing of the Reformation. Bremen 1962.

- ↑ Harold S. Bender: The Anabaptist Vision. Mennonite Church USA Historical Committee and Archives / Herald Press, 1944, archived from the original on June 24, 2014 ; accessed on May 12, 2018 .

- ↑ Stayer: Anabaptist. (TRE) (2001), p. 597.

- ^ Johann Conrad Füßlin: Additions to the explanation of the stories of the Schweitzerland ; Zurich 1741–1753, Vol. I – V, here: Vol. II 69, quoted from Clarence Bauman: Nonviolence in Anabaptism. An investigation into the theological ethics of Upper German Anabaptism during the Reformation. (Studies in the History of Christian Thought, Vol. III). Leiden 1968, p. XIII, note 4.

- ↑ So the edition series "Sources for the History of the Anabaptists" was renamed after two volumes in "Sources for the History of the Anabaptists".

- ↑ See Stayer, Packull, Deppermann: From Monogenesis to Polygenesis . 1975.

- ↑ See Goertz (1980), p. 12f.

- ↑ James M. Stayer: Anabaptist Research. In: Mennonite Lexicon . Volume 5 (MennLex 5).

- ^ Franz Graf-Stuhlhofer : 500 years of the Anabaptist Movement - it began around 1521. In: Allianz-Spiegel No. 134, March 2021, p. 17f, as well as Graf-Stuhlhofer: When baptisms were still a serious crime , in: Wiener Zeitung from 22. May 2021.

- ^ Goeters: Anabaptists. 1958, p. 1812.

- ↑ QGTS , Vol. 1, No. 12, p. 11.

- ↑ Leu / Scheidegger (2007), p. 29f.

- ↑ Blanke (1955), pp. 20f.

- ↑ Leu / Scheidegger (2007), p. 43f.

- ↑ See Strübind: The Disputation of January 1525. 2004, pp. 337–351.

- ↑ World Community Sunday January 27, 2013 (PDF; 101 kB) Mennonite World Conference, accessed on July 14, 2013 .

- ^ Fritz Blanke: Brothers in Christ. The history of the oldest Anabaptist community. Zurich 1955.

- ↑ On Jörg Blaurock as an evangelist see JA Moore: Der stark Jörg. Kassel 1955.

- ^ Fritz Blanke: Anabaptism and Reformation. In: Guy F. Hershberger (Ed.): Das Anäufertum. Legacy and Commitment. Stuttgart 1963, p. 59f.

- ↑ Since 1523, only Protestant sermons were allowed. The Lord's Supper was celebrated in the Zurich churches according to the Roman Catholic rite until Easter 1525 - but without the words of change provided for in the liturgy ; see Fritz Blanke: Anabaptism and Reformation. In: Guy F. Hershberger (Ed.): Das Anäufertum. Legacy and Commitment. Stuttgart 1963, p. 59f.

- ^ Fritz Blanke: Anabaptism and Reformation. In: Guy F. Hershberger (Ed.): The Anabaptism. Legacy and Commitment. Stuttgart 1963, p. 60.

- ↑ John H. Yoder: The Legacy of Michael Sattler . Scottdale 1973, pp. 29f.

- ↑ See Haas (1975).

- ↑ Klaus Deppermann: Melchior Hoffman. Social unrest and apocalyptic visions in the age of the Reformation. Göttingen 1979, p. 160.

- ↑ Goertz (1980), pp. 20ff.

- ↑ Goertz (1980), p. 23.

- ↑ Eduard Widmoser: The Anabaptism in the Tyrolean lowlands. Innsbruck 1948, p. 14.

-

↑ For example by Sebastian Franck in his so-called Turkish Chronicle : "In our times three main faiths have risen, which have large followers, as Lutheran, Zwinglisch and Anabaptist." Quoted from Alexander Nicoladoni: Johannes Bünderlin and the Upper Austrian Anabaptist communities in the years 1525 -1531. Berlin 1893, p. 123.

Gottfried Herrmann: Luther's rejection of the Anabaptists. (pdf, 450 kB) Seminar paper on ecclesiastical history at the Kirchliche Hochschule Leipzig, March 1975, pp. 1–27 , accessed on July 21, 2018 (the author has been a lecturer in ecclesiastical history at the Luth. Theol. Seminar Leipzig since 1989). - ^ Veit-Jakobus Dieterich: Martin Luther . Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-423-34914-7 , pp. 108 .

- ↑ Klaus Deppermann: Melchior Hoffman. Social unrest and apocalyptic visions in the age of the Reformation . Göttingen 1979, pp. 158-159.

-

↑ Martin Rothkegel: Expansion and persecution of the Anabaptists in Silesia in the years 1527–1548 (= Archive for Silesian Church History . No. No. 61 ). 2003, ISSN 0066-6491 , p. 149-209 . Siegfried Wollgast: Morphology of Silesian Religiousness in the Early Modern Era: Socinianism and Anabaptism. In: Würzburger medical history reports, ISSN 0177-5227 , 22, 2003, pp. 419–448.

- ↑ Klaus Deppermann: Melchior Hoffman. Social unrest and apocalyptic visions in the age of the Reformation . Göttingen 1979, p. 275.

- ↑ For the dates given here, see Wolfgang Schäfele: The missionary consciousness and work of the Anabaptists. Represented on Upper German sources. Neukirchen-Vluyn 1966, p. 34f.

- ↑ Quoted (and translated) from SM Jackson: Selected Works of Huldreich Zwingli. Philadelphia 1901, p. 127.

- Jump up ↑ Heinrich Bullinger: The origin of the rebuilt. fol. 15v.

- ↑ Quoted from CA Cornelius: Geschichte des Münsterischen Aufruhrs. 2nd Edition. Leipzig 1860, p. 52.

- ^ Franz Agricola: First evangelical trial against all sorts of cruel errors of the Anabaptists. 1586; quoted from Karl Rembert: The Anabaptists in the Duchy of Jülich. Berlin 1899, p. 564.

- ↑ Gustav Dossert (ed.): Sources for the history of the Anabaptists. Volume I: Duchy of Württemberg. Leipzig 1930, p. 210ff.

- ↑ A collection of other opponents' testimonies can be found in Harold S. Bender: The Anabaptist model. In: The Anabaptism. Legacy and Commitment. Stuttgart 1963, pp. 45ff.

- ^ Letter from Konrad Grebel to Thomas Müntzer (Zurich, September 5, 1524); engl. ( Memento of September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ); viewed on January 24, 2010. - This letter did not reach Müntzer.

- ↑ Schleitheim Article (Schleitheimer Anabaptist Confession) 2. Website of the Schleitheim Museum, p. 14 , accessed on May 13, 2018 (The quote comes from Article VI ( From the sword ).).

- ↑ Lars Jentzsch: The doctrines of the Swiss Anabaptists. In: täufergeschichte.net. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015 ; accessed on May 13, 2018 .

- ↑ Cf. the formulations in numerous church ordinances of the 16th century, for example the church ordinance Pfalz-Zweibrücken 1557, in: Emil Sehling (initial): The Protestant church ordinances of the 16th century. Volume 18: Rhineland-Palatinate I. p. 136.

- ↑ Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger: Introduction to the Early Modern Age . Website of the history seminar of the University of Münster.

- ↑ Wikibooks: History of the origin of the Hutterites

- ↑ Emil Sehling (Greetings): The Evangelical Church Regulations of the 16th Century. Volume 16: Baden-Württemberg. II, pp. 335f.

- ↑ See excerpt from the Martyr's mirror ; English; accessed on February 22, 2009.

- ↑ Martyrs . In: Christian Hege , Christian Neff (Ed.): Mennonitisches Lexikon , Volume III . Self-published, Karlsruhe 1958, p. 47 .

- ↑ Rudolf Wolkan (Ed.): History book of the Hutterite Brothers ; Vienna 1923. In the preceding register of the book there is a chronological compilation of the fates of the Anabaptists described on p. XXXII ff. on page 182ff there is a tablet of the martyrs from 1527 to 1544.

- ^ Mennonite Lexicon , Volume IV, 1967.

- ↑ Gottfried Seebass, Irene Dingel, Christine Kress (eds.): The Reformation and their outsiders. Collected essays and lectures . Brill 1997, p. 281 .

- ^ Gerhard Florey: History of the Salzburg Protestants and their emigration 1731/32. (Studies and texts on church history and history, 1; Vol. 2). 2nd Edition. Böhlau, Vienna et al. 1986, ISBN 3-205-08188-9 , pp. 49-50.

- ↑ Wolfgang Krauss: Don't let anyone in? or do we cancel the manure concession after 350 years? On the deep structure of Mennonite identity at the beginning of the 3rd millennium. (pdf, 92 kB) Down to Earth Verlag, October 23, 2004, p. 3 , archived from the original on September 19, 2011 ; accessed on May 12, 2018 (Krauss speaks of "Ekklesiozid" (= church murder) in parallel to "genocide" (= genocide).).

- ↑ Gottfried Seebass, Irene Dingel, Christine Kress (eds.): The Reformation and their outsiders. Collected essays and lectures . Brill 1997, p. 281 .

- ↑ Homepage

- ↑ Reinhard Bingener: Reconciliation after 500 years. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , July 24, 2010, accessed on May 13, 2018.

- ↑ This designation goes back to an essay by Roland Herbert Bainton published in 1941 ( The Left Wing of the Reformation. In: Journal of Religion No. 21, 1941, pp. 124-134). In the German-speaking world, she was best known for the Anabaptist story written by Heinold Fast ( The Left Wing of the Reformation , Bremen 1962).

- ↑ Quoted from Päivi Räisänen: Heretics in the village. Visitation procedures, the fight against Anabaptists and local patterns of action in early modern Württemberg. UVK, Konstanz 2011, ISBN 978-3-86764-255-2 , p. 339.

- ↑ Quoted from Urs B. Leu, Christian Scheidegger (Hrsg.): Das Schleitheimer Confession 1527. Introduction, facsimile, translation and commentary. Achius, Zug 2004, ISBN 3-905351-10-2 , p. 12.

- ↑ The difference lies in the assessment of the Mennonites. While the Mennonites see themselves as direct descendants of the Swiss brothers and Menno Simons “only” as a leading figure in this direction in the Dutch and northern German area Quelle? , others consider the Mennonites to be a completely independent movement, which after the catastrophe in Münster gathered other Anabaptist tendencies (including the Swiss brothers) and integrated them for a longer period of time.

- ^ Paul Wappler: The Anabaptist Movement in Thuringia from 1526-1584 . Ed .: Association for Thuringian History and Archeology. Publishing house by Gustav Fischer, 1913.

- ^ Jan J. Kiewiet: Pilgram Marbeck. Kassel 1958, p. 54ff.

- ↑ World Mennonite Membership Distribution at GAMEO.

- ↑ Dieter Götz Lichdi: The Mennonites in the past and present. From the Anabaptist movement to the worldwide free church. Großburgwedel 2004, p. 452.

- ↑ Heinold Fast: The left wing of the Reformation. Bremen 1962, pp. IX - XXXV.

- ↑ Heinold Fast: The left wing of the Reformation. Bremen 1962, p. 318: “The confession of Obbe Philips is not the testimony of faith of a fanatic, but that of a spiritualist. It doesn't really belong here ... "

- ^ Ferne Burkhardt: New global map locates 1.6 million Anabaptists. Mennonite World Conference, archived from the original on October 29, 2012 ; accessed on May 12, 2018 .

- ↑ L. Jentsch: Amish. Anabaptististory.net, archived from the original on September 24, 2015 ; accessed on May 23, 2018 .

- ↑ L. Jentsch: Hutterer. Anabaptististory.net, archived from the original on September 24, 2015 ; accessed on May 23, 2018 .

-

^ LWF General Assembly asks Mennonites for forgiveness. Lutheran World Federation, Eleventh Assembly, July 22, 2010, archived from the original on March 20, 2012 ; accessed on May 13, 2018 . After Previous Persecution: Lutherans Reconcile with Mennonites. In: Tagesschau . July 22, 2010, archived from the original on July 25, 2010 ; accessed on May 13, 2018 .

- ↑ Ecumenical expert: The Lutherans' request for forgiveness is a historical act