Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis

| Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Studio | LucasArts | ||

| Publisher |

|

||

| Senior Developer | Hal Barwood Noah Falstein |

||

| Erstveröffent- lichung |

June 1992 | ||

| platform | IBM PC , Amiga , Macintosh , FM Towns , Microsoft Windows , Wii | ||

| Game engine | SCUMM | ||

| genre | Adventure | ||

| Game mode | Single player | ||

| control | Mouse , keyboard | ||

| medium | Floppy disk , CD-ROM , Wii Optical Disc , download | ||

| language | German (screen texts), English (voice output) | ||

| Age rating | |||

Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis Ⅰ is a computer game from the point-and-click adventure genre that was developed by LucasArts and first published in 1992. It is the seventh title to use the SCUMM game engine and scripting language . In Fate of Atlantis you explore the game world and interact with objects and figures by generating commands and solving puzzles using given verbs. There are three different campaigns available: depending on whether players choose the team path, puzzle path or action path, the further course of the game changes and the plot develops differently. Occasional action and combat sequences offer a change from normal game events, while a points system records the challenges overcome and is intended to encourage a repeat run.

Fate of Atlantis is the second game of its kind with the film character of the archaeologist Indiana Jones in the lead role. The plot is set in 1939 and revolves around the protagonist's search for the legendary, sunken city of Atlantis . Indiana Jones is accompanied on his journey around the world by his former professional colleague Sophia Hapgood, who hires herself as a medium and is in contact with an Atlantean king through a supernatural medallion. The duo are hunted in search of the lost city by the Third Reich , which seeks the power source of Atlantis for the purpose of warfare.

The story was written by designers Hal Barwood and Noah Falstein after they turned down an unused Indiana Jones film script as a proposal for a game design. Atlantis was chosen by them as MacGuffin - that is, as a plot-carrying object - because, in their opinion, the descriptions of the city in literary sources required use in a computer game. The former film scriptwriter and producer Barwood worked intensively on the Indiana Jones series and finally prevailed against the company philosophy of his employer by exposing the protagonist in the game, true to the films, to dangerous situations atypical for LucasArts. Falstein's idea to incorporate the three different game paths cost Barwood and his team an additional six months of development time and caused Fate of Atlantis to overshoot the originally planned budget by 50%. During production, techniques such as rotoscopy and dynamic music were used that were still relatively new to LucasArts.

Originally published as a floppy disk version for IBM PCs , Fate of Atlantis was later implemented on other home computers and as a so-called " Talkie " edition. This CD-ROM version with voice output and digital sound effects was also the basis for later new releases from 2009. Fate of Atlantis was highly praised by reviewers, repeatedly crowned the best adventure game of the year and honored at public awards ceremonies. Critics were particularly positive about the three ways of playing, which should appeal to the broadest possible audience. Recipients also paid special attention to the film-ready story and presentation, which is why the game was considered a worthy continuation of the previously published trilogy.

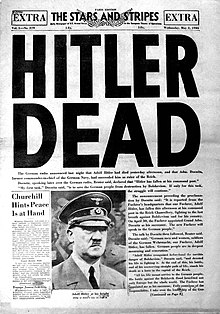

Even long after the release of Fate of Atlantis , there were rumors about a possible film implementation of the adventure; however, it was only adapted as a comic series and as an arcade-like action game. Fate of Atlantis sold over a million copies and is now widely considered a classic of its genre. Several Adventure successors were planned, but could never be brought to market: including a tie-in product for the television series The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones , and Indiana Jones and the Iron Phoenix, set after World War II , with a story to tell the Soviet secret service and a mystical revival of Adolf Hitler . Barwood's later idea for a plot about flying saucers in the 1950s had to be discarded as it was saved for the fourth feature film Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull . On the other hand, his designs for the casual game Indiana Jones and his Desktop Adventures and the action adventure Indiana Jones and the Tower of Babel made it onto the market .

Gameplay

Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis is based on SCUMM , a game engine and scripting language for point-and-click adventure games from LucasArts . The gameplay is based on exploring the two-dimensional , static environments of the game world and interacting with moving figures and objects to solve puzzles and advance the embedded storyline. It is controlled either by mouse or keyboard . Click the mouse pointer to move the character across the screen. With the help of predetermined action verbs such as “take”, “use” and “speak”, a command can be generated and executed for them. In this way, among other things, items in the inventory are combined with one another and applied to objects in the vicinity. For example, at one point in the game you use a large basket, a fishing net, a rubber balloon and a hose together to build an improvised hot air balloon , then fill it with gas at a fumarole and thus reach the next area.

In order to solve puzzles and obtain new clues and items, conversations with non-player characters often have to be conducted through a sequence of selectable questions and answers . Some of the puzzles in the game hide the environment and instead show a close-up of a mechanism that must be put into operation by arranging its individual parts correctly. Various action sequences from a bird's eye view also offer a change from normal gameplay: During a camel ride through the desert you have to avoid other travelers, ram enemy vehicles during a car chase, or adjust the direction and altitude in a hot air balloon.

Early in the action, the player is given a choice of three different game modes , each with its own cutscenes , puzzles, game elements and environments: the team path, the puzzle path and the action path. On the team path, the protagonist and character Indiana Jones - also known as Indy - is accompanied by his partner Sophia Hapgood, who gives the player advice. The puzzle path offers a wealth of complex puzzles, while the action path is heavily geared towards fistfighting. Occasionally, the player also takes control of Sophia, who evokes other reactions from her interlocutors and has her own inventory. With a few exceptions, it is always possible to save the game. In the case of saved games, a rating system, the Indy quotient, records the puzzles solved, obstacles overcome and important finds based on a score . Using a random generator , parts of the puzzles are slightly changed each time the game is played - for example, the entrance to a game environment changes to a different location and puzzles require a different combination of solutions.

What is unusual for a LucasArts title is the fact that the protagonist can die at certain points in the game. However, such dangerous situations are designed so that they can be easily recognized by the player. An example of this are many of the aforementioned fist fights, which also occur outside of the action path, but there are much less frequent. In these battle sequences, the regular display at the bottom of the screen is replaced by two bars of strength and health for the character and their opponent. During a fight, the player can direct Indy's punches to three different areas of the body (such as the head) of his opponent. After each blow, the impact force is reduced; this only increases again if there is no new attack for a while. The higher the punch, the more health points the combatant who is hit loses. If many blows are dealt in a short time, the adversary shrinks back. The player also has the option of blocking enemy attacks, evading them by stepping backwards or even fleeing. An argument ends victoriously when the opponent's health bar is empty. In most fights, a “cheat key” can be used to knock out a punch in order to win immediately - however, the player does not receive any points for the Indy quotient for this. If you have won an exchange of blows, but the character is damaged in the process, your health points will gradually regenerate until the next fight.

action

The Indiana Jones stories are set in an exaggerated version of the real world with fantastic elements. The plot of Fate of Atlantis Set in the year 1939, shortly before the outbreak of World War II . The main character is Dr. Henry Walton Jones Jr., an archaeologist and occult expert who, in addition to his professorship at Barnett College, is an Indiana Jones adventurer who searches for rare artifacts . On behalf of a visitor posing as a Mr. Smith , Indy searches the archives of his university for a mysterious, horned statue. After finding this little figure, Smith hands him some kind of key to open it and reveal a glittering metal bead from inside. Smith then draws a gun and takes flight with both artifacts, but he loses his coat. The ID in one of the pockets reveals that “Smith” is actually called Klaus Kerner and is a spy from the Third Reich . In the coat, Indy also finds an old magazine with an article about an excavation he worked on over ten years ago with a woman named Sophia Hapgood; Sophia is said to have given up her archaeological career in the meantime to become a medium .

Fearing that Sophia Kerner's next target could be, Indy immediately sets off for New York City to warn her and to learn more about the mysterious statue, which so far cannot be assigned to any of the known high cultures . Once there, he bursts into Sophia's pseudoscientific lecture about the culture and the fall of the legendary city of Atlantis and accuses her of cheating in front of her audience. In a rage, Sophia takes Indy back to her apartment to give him a lecture, but the two find a picture of the devastation that Kerner left behind while searching for Atlantic artifacts. Sophia is reassured that at least her most valuable piece, an Atlantic medallion in the shape of a horned head, could not be stolen because she always wears it as a necklace. She also has one of the glittering pearls, which she now identifies as the mysterious metal orichalcum from Atlantis described by the Greek philosopher Plato . Inexplicable powers are ascribed to the pearls: they acted as a source of energy for machines, and Sophia can summon the spirit of the Atlantean king Nur-Ab-Sal when she sticks a pearl of the metal into the mouth of her medallion. She explains to Indy that a Nazi scientist, Dr. Hans About man, for the purpose of warfare by orichalcum investigated and the Lost City.

Nur-Ab-Sal then telepathically contacts Sophia via the medallion and orders her to find Hermocrates : this book is the lost dialogue of Plato and is supposed to lead Indy and his partner to Atlantis with the information it contains. After several trips and discussions with Atlantis researchers and collectors, the Hermocrates can finally be found in a collection at Barnett College. The text of the dialogue corrects Plato's "tenfold mistake", an earlier translation error from Egyptian into Greek that falsified the philosopher's figures by a factor of ten. With this he determines the exact location of Atlantis in the Mediterranean , namely 300 instead of 3000 miles from Greece as described in the previously written dialogue Critias . The Hermocrates also states that you can only gain access to the lost city and its colonies with three special, engraved stone discs . At this point the player is given a choice between the team, puzzle, and action path; it influences where and how the stones can be found. Kerner and Übermann have Sophia captured on all three routes. Indy, however, finally reaches the underwater entrance of Atlantis near Thira with the three stone discs .

The three paths come together again at this point. Indy begins exploring the Lost City, which is connected to an active volcano and built in three concentric circles as described by Plato . He finds out how to use different Atlantic machines and how to make orichalcum pearls from liquid lava . With this knowledge he frees Sophia from a prison cell and penetrates with her into the center of Atlantis. Sophia's medallion leads them to the home of Nur-Ab-Sal, where the spirit of the Atlantean king takes hold of them. Only through a trick is Indy able to take the locket from Sophia and destroy it. Nur-Ab-Sal's spirit is destroyed and Sophia freed from her obsession . As they explore further, Indy and Sophia find a number of deformed and partly horned skeletons.

You will eventually reach the heart of Atlantis, a colossus that the city's residents built to make themselves gods . According to Plato's lost dialogue, they used ten orichalcum pearls at once, in the hope of controlling the water level with their newfound powers. In this way, they wanted to keep the sea level low enough to avert an impending flood . However, it is also reported how Nur-Ab-Sal is said to have made malformed creatures out of many men. Inside the Colossus , Indy accidentally activates the god machine with the stone discs, after which Kerner and Übermann invade with their soldiers. As part of the supposed Aryan master race, the National Socialists consider themselves immune to the deformities to which the Atlanteans were subject during their transformation.

Übermann wants to use Indy as a test subject for the machine, but Kerner steps onto the platform for transformation first, as he considers himself most suitable for an existence as a god. Just as Übermann is about to start up the machine, Indy mentions Plato's tenfold mistake, which convinces the doctor and Kerner to use only one instead of ten pearls. The machine then transforms Kerner into a warped, horned dwarf creature, and he burns in the lava surrounding the transformation platform. Indy is next forced to stand on the platform, but threatens Übermann to send him to Hell once he's a god. Fearing retaliation, Übermann transforms himself and feeds the machine 100 pearls. He transforms into a green, disembodied being and finally vanishes into thin air. In the end sequences with a bad outcome, one of the protagonists is subjected to the transformation with the 100 pearls; this happens when Indy failed to convince Übermann to use the machine on himself, or when Sophia was not released from her prison line or from Just-Ab-Sal's control. In the end sequence with a happy ending, Atlantis succumbs to a volcanic eruption and the hero duo can escape the city just in time. In the final scene, Indy kisses Sophia to comfort herself with the lack of evidence that they found together.

Development details

Idea and Production

After the Indiana Jones feature film trilogy came to an end, the American game developer Lucasfilm Games - which later became LucasArts - wanted to continue using the character of the archaeologist and adventurer because of its large fan base and so decided to develop a successor to Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure . At the time, however, the company's employees were busy with other adventure projects like The Secret of Monkey Island and The Dig , so filmmaker and game designer Hal Barwood was hired as a new addition. With his programming skills, he had already developed two computer games independently, but was appointed project manager of the new Indiana Jones title because of his experience as a screenwriter and producer for films such as Close Encounters of the Third Kind and The Dragon Slayer.

Originally, Barwood was commissioned with a game design based on a rejected script by filmmaker Chris Columbus for the third feature film in the series . The story would have been about Indy's search for Chinese artifacts and magical peaches in Africa, as well as the mythological Monkey King . After reading the script, however, Barwood thought the idea was subpar and felt it hadn't been rejected for nothing. He and his colleague, game designer Noah Falstein, agreed that the script wouldn't work as a game. The two developers visited the library at Skywalker Ranch , the workplace of filmmaker and Indiana Jones creator George Lucas , to look for a suitable MacGuffin for their adventure game - an object that drives the plot forward. Falstein and Barwood shortlisted the mystical sword Excalibur for this , but the idea was discarded because it would have limited the travel destinations in the game to locations in England .

While rummaging through illustrated books about unsolved secrets of the world, they finally came across a diagram in an issue of Time Life that showed the structure of Atlantis in three concentric circles. It looked like it was made for a computer game, which is why the MacGuffin chose the sunken city. Development then began in the spring of 1990. Since the myth of Atlantis is loosely based on historical sources, intensive preliminary research was carried out for the story of the game. The description of the structure of the lost city and the metal orichalcum "with a fire-like shine" was taken from the dialogues of Plato . The incorrect location of Atlantis due to Plato's tenfold error was also mentioned in real publications; for example, there is a controversial theory by scientists Angelos Galanopoulos and James Watt Mavor about such a translation error from Egyptian into Greek.

The properties of the orichalcum as an energy source and the Atlantic technology in the game were partly taken from writings of the Russian spiritualist Helena Blavatsky on the presumed power of the vril . Blavatsky associated the vril, described by the writer Edward Bulwer-Lytton in his novel The Coming Race , with a "[vibratory] force" allegedly used by the Atlanteans, "when aimed at an army [...] on a flying vehicle is attached [...] 100,000 men and elephants crumble to ashes ”. The bridge back to the Orichalcum was finally built via the American spiritual healer Edgar Cayce , who later reported on a powerful Atlantic energy source and weapon called "Flint" . Barwood then built a race between Indy and the National Socialists with the metal as MacGuffin as the starting point for the plot of the game. The pearl shape of the orichalcum , the stone disks, the content of Plato's lost dialogue and the god machine of Colossus are considered a free invention of the developers .

Barwood feared he would bore Indiana Jones fans if he postponed supernatural elements similar to the feature films to the dramatic climax at the end. That is why he divided the playing time, which is much longer than that of the films, into “rhythmic segments”, each of which goes through a development from the profane to the fantastic. The figure of Sophia Hapgood was created to enable permanent interactions for the protagonist and to resolve the story at the end through the Atlantic medallion. In order to portray Indiana Jones as authentically as possible in the game, Barwood watched the films again and again and read the Lucasfilm "Bible", which described important stages in the character's fictional life. In particular, he believed that Indy would only appear believable if he could die in the game as well. His resulting proposal to incorporate action sequences into Fate of Atlantis was reluctantly accepted by LucasArts. In contrast to the rival company Sierra , which often let its characters die unexpectedly while trying to solve a puzzle, LucasArts wanted to keep the player safe and not have previous saved games reloaded for a new attempt.

Falstein had formal control over Barwood's ideas, such as the action sequences, but did not exercise this right. For meticulous players who want to completely solve a game, Falstein had developed the point system of the Indy quotient. In order to appeal to the broadest possible audience, he also suggested implementing three different ways of playing. Falstein wanted to adapt the adventure to the preferences of the individual players. Together with Barwood, he worked out a rough draft for the three paths and then left their implementation to his colleague, as he moved on to other projects. This game mechanics extended the development time by about six months to just under two years and increased the budget required by 50%, which was against the management of LucasArts. The extra effort was, among other things, a consequence of the additionally required dialogues between Indy and his partner, so that as a countermeasure overlaps - i.e. common elements - were built into the three paths and Sophia was allowed to disappear from the scene as often as possible.

Barwood took on a variety of roles during production: he revised the game designs, wrote the script, and was involved in both the artistic and programming roles in both an active and a supervisory role. He later recalled that production in the company had started at a carefree time when there were no strict guidelines and auxiliary staff could easily be called in. However, as it evolved, the company experienced the first of many management changes and began to be very careful about its finances. Over time, Barwood increasingly had to create animations and program code himself in order to meet his production goals.

Technology and design

Fate of Atlantis is the seventh game to be developed using the SCUMM system. The game designer Ron Gilbert originally designed it for his Adventure Maniac Mansion on the Commodore 64 home computer to simplify its production and gaming experience. On the one hand, he wanted to get rid of the text parser known from previous adventures , because he didn't like typing in commands for a character manually and he found it to be buggy. Gilbert wanted to make operation more intuitive by allowing the player to point the mouse directly at an object on the screen and thus interact with it. On the other hand, he did not want to program the game completely in the comparatively complicated and therefore time-consuming assembly language.

Gilbert found that the elaborate program elements such as the graphics display were as good as finished after a one-time programming, but that other parts relating to the logic and the course of the game had to be adapted repeatedly during production. That's why he created SCUMM, a simple scripting language that even an inexperienced developer could use to program game mechanics such as camera and figure movements with English text commands such as " camera-follow nurse-edna ". The second part of SCUMM consisted of development tools for creating game files such as animations and sounds. The only platform-dependent part of SCUMM is the interpreter or the runtime - the game engine SCUMM Presentation Utility ™ (SPUTM for short). The high portability of the system meant that it was used for many other LucasArts Adventures such as Fate of Atlantis , with a good 80% of the original script language components from Maniac Mansion being used. In addition to Gilbert, Aric Wilmunder, Brad P. Taylor and Vince Lee are given in Fate of Atlantis as the creators of the SCUMM system used there. Wilmunder and Taylor had taken over the SCUMM porting from the Commodore 64 to PCs; Lee contributed additional graphics and audio tools.

After completing the draft of the story, the team began devising puzzles for Fate of Atlantis . The artists around chief designer William Eaken were sometimes consulted by Barwood when it came to puzzles that had a strong visual component. One such example is a broken Atlantic robot, for which the artists had to design a kind of Rube Goldberg machine at the request of the game designer - a device that fulfills a simple task in an overcomplicated way. The artifacts and architecture of Atlantis were designed by Eaken and were intended to be reminiscent of the Minoan culture . Barwood wanted to take this up in the plot of the game and suggest that the Minoans had been inspired by the Atlanteans. His requirement for Eaken was to make things “strange” and “creepy”. The machines were supposed to make use of as yet unknown physical principles instead of magic .

By supporting the VGA computer graphics standards can in Fate of Atlantis simultaneously 256 different colors can be displayed on the screen. The artists had to share this limited palette: backgrounds and character animations were each available only about half of the 256 colors. The appearance of the Indiana Jones character in the game was modeled after his film actor Harrison Ford . For Sophia Hapgood, LucasArts Development Director Lucy Bradshaw was the model. Barwood found that the characters had always moved unnaturally stiffly in previous games and gave the animation team the task of making this graphic aspect more realistic. Ultimately, the rotoscopy method was used for this: video recordings of real actors were made in bright sunlight against a plain background . For Indy the artist Steve Purcell and for Sophia the chief animator Collette Michaud stood in front of the camera.

Then the desired individual images were extracted and digitized via a connection between the video camera and Macintosh II . With the image processing program Photoshop , the background was removed from each individual image and the color and size of the remaining figure were adjusted. Then the individual images were combined to animations on an IBM PC using the program Deluxe Paint Animator from Electronic Arts , reduced to the final pixel size of the figures and digitally repainted. As a last step, the animations were fine-tuned and choreographed in a specially created program before they were given to the programmers for integration into the game. The animators only had a limited number of memory-intensive individual images available for each movement due to the low hard drive capacity at the time.

The 95 or so game environment backgrounds of Fate of Atlantis were drawn directly with the mouse on the computer pixel by pixel in the graphics program Enhanced Deluxe Paint . Eaken sketched his ideas first on paper, then on the computer with narrow, colored lines; he then approached the final background by coloring patches of area and adding details. Already based on the line sketches, the programmers began to cover the backgrounds with a wire frame model at the same time in order to determine where the characters are allowed to move in the area. Further programming tasks were the integration of dialogues and objects. The pure artistic creation of a single background took one to two days. The biggest challenge was to make the scenes appear "spontaneous and organic". To make the backgrounds appear less computer-generated, decorative texture patterns , such as chipping and decay on a brick wall, as well as coloring from incident light were used.

Barwood changed his game designs frequently, which often resulted in a background having to be reworked dozens of times. The revisions were applied to any artist who had the time, so that in the end almost every artist had a hand on practically all backgrounds. Because of the numerous design changes, a lack of version control, and the unique elements in the backgrounds that each of the three game paths brought with it, it was often the case that an outdated version of an image was inadvertently worked on. Towards the end of development it became possible to scan a drawing on paper and convert it to a background. However, Eaken was not satisfied with the results due to pixel artifacts and decided together with his colleagues to stay with Deluxe Paint . Only in this way was it possible to achieve the specification of a realistic graphic style based on the feature films. The illustration for the product packaging of Fate of Atlantis should also be reminiscent of the Indiana Jones cinema versions, more precisely of the film posters by the artist Drew Struzan . It was drawn by Eaken in just three days after disagreements over whether to use his design or that of an outside art director.

music

Composers Clint Bajakian , Peter McConnell and Michael Land wrote the music for Fate of Atlantis . Although the Indiana Jones main theme " The Raiders March " by film composer John Williams has been arranged for various pieces, most of the music is recreated for the game. Bajakian, for whom it was one of the first projects in the computer game industry, did the lion's share of the work. McConnell described the cooperation on the individual pieces with that in a band , since many works were repeatedly exchanged between the composers. The three musicians tried to copy Williams' style, particularly adopting his use of leitmotifs and themes . Since the sound hardware of the time allowed only a few sound channels, the most prominent musical gestures had to be filtered out of Williams' orchestral arrangements for dozens of instruments and transferred to computer music .

Fate of Atlantis uses sequenced music , i.e. digitized scores that are recorded in the IBM PC version via the system loudspeaker , the FM synthesis of an AdLib or Sound Blaster sound card, or the instrument samples of a Roland MT-32 sound module be played. The music was first written for high quality sound hardware and then adapted to the aforementioned playback options. The composers concentrated on optimizing the AdLib playback, knowing that 90% of the audience at the time had compatible hardware. Fate of Atlantis uses the iMUSE music system invented by Land and McConnell , which interactively adapts the background music to the game and allows seamless transitions between individual pieces. The system was implemented to make the permanent background music in Fate of Atlantis appear as varied and not repetitive as possible.

Versions and ports

The game was first released in June 1992 in a floppy disk version for IBM PCs . An implementation for Amiga computers with less graphic color depth, remote iMUSE system, fewer compositions and a reduced number of music voices followed in autumn 1992. The best LucasArts employees were no longer responsible for this port : The Amiga was already losing at this time of market economic importance and the company developed the implementation rather out of necessity because of a contractual obligation for the European market. A version for the Atari ST home computer was also planned.

In May 1993, the so-called " Talkie " edition was finally published on CD-ROM for IBM PCs with voice output and new, digital sound effects . Hal Barwood was no longer involved in the studio recordings for the setting, as he was now working on another project. Instead, the dialogue director Tamlynn Barra was responsible for this. For the new edition, around 8,000 lines of text for around 40 characters were recorded over a period of around four weeks, with actors from the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists being selected. In July 1993 a version for Macintosh computers was released on floppy disk and CD-ROM . The sound was completely revised for this implementation. In August 1993 the publisher Victor Musical Industries or Victor Entertainment - a subsidiary of JVC - brought Fate of Atlantis with voice output for the Japanese computer system FM Towns on the market. The company planned to release the Talkie edition for the Sega Mega-CD console in November 1993 , but ultimately abandoned those plans.

The " Talkie " edition was later incorporated into the Wii version of the 2009 action adventure game Indiana Jones and the Staff of Kings as bonus material . From the same year it was also offered on the Internet sales platform Steam as a port for the Microsoft Windows and Mac OS X operating systems . The Wii and Steam versions contain both on-screen text and voice output and use the MIDI industry standard for the playback of electronic musical instruments for the pieces of music. Since October 2014, GOG.com has also been selling a downloadable version without digital rights management that works on Microsoft Windows, Mac OS X and Linux .

Translation and localization

The game was adapted for the local market by the journalist Boris Schneider-Johne , who at the time worked for LucasArts' German sales partner Softgold . Although he had translated several adventures by LucasArts on their own in German, it was for Fate of Atlantis with Heinrich Lenhardt , asked two colleagues and Torsten Oppermann aside as the company did not want to focus only on a single translator. Schneider-Johne had also taken care of the programming and mastering of the German versions on previous projects . At Fate of Atlantis, however, he only worked on the German screen texts. It was Schneider-Johne's last computer game project for the time being, as he gave up his translation work in favor of his position as editor-in-chief of PC Player magazine “for reasons of the journalist's ethos ”. While the translation was still in progress, the LucasArts boss at the time prohibited him from accessing the game's source code for security reasons .

The localization of the LucasArts Adventures included not only the pure text translation but also further adjustments for the German market. In Germany, for example, according to Section 86a of the Criminal Code (StGB), the use of symbols of unconstitutional organizations such as the swastika is a criminal offense. The so-called social adequacy clause of Section 86 (3) StGB excludes the dissemination of such propaganda material from punishment if the use is, for example, part of a work of art; however, the clause was hardly taken up in the case law in the 1990s in connection with computer games. As a result, depictions of swastikas were tolerated in the Indiana Jones feature film series, but in computer games there was a risk of criminal prosecution or confiscation of the product. The additional risk of indexing for reasons of youth protection , which was similar to a sales ban, gave game publishers good reasons to remove swastikas from German language versions as a precaution. Still with Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: For the graphic adventure , Schneider-Johne had to paint over a number of swastikas in the game with Deluxe Paint to make black squares. In Fate of Atlantis, on the other hand, there was only one swastika to remove from Klaus Kerner's ID card for the German version.

reception

| Comparison of sales figures for earlier LucasArts Adventures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| game | Sales figures | |||

|

> 250,000

|

||||

|

> 500,000

|

||||

|

> 100,000

|

||||

|

≈ 25,000

|

||||

|

Indy 4

|

> 1,000,000

|

|||

|

≈ 80,000

|

||||

|

1,000,000

|

||||

|

300,000

|

||||

Sales figures and audience

The computer game history book Rogue Leaders: The Story of LucasArts describes Fate of Atlantis as a "best seller". It was LucasArts' most successful release, selling over a million units, surpassing the previous successes of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure and The Secret of Monkey Island . According to Noah Falstein, large parts of the adventure game community in the 1980s and 1990s were women, and LucasArts in particular tried to reach this segment of the audience. Using the feedback cards that came with the games, the company was able to determine that around 30% of the players in Fate of Atlantis were women, outperforming most previous LucasArts titles. Falstein also attributed this success to the fact that female gamers were able to control the character of Sophia Hapgood at times long before computer game heroines became more widespread.

Gaming experience

| reviews | |||

| publication | Rating | ||

| IBM PC | Amiga | macintosh | |

| PC joker | 90% | k. A. | k. A. |

| Current software market | 11/12 | 9/12 | 11/12 |

| Power play | 94% | 72% | k. A. |

| PC review | 9/10 | k. A. | k. A. |

| The One Amiga | k. A. | 88% | k. A. |

| CU Amiga | k. A. | 90% | k. A. |

| Amiga joker | k. A. | 91% | k. A. |

| Amiga format | k. A. | 92% | k. A. |

| Amiga Games | k. A. | 85% | k. A. |

| Amiga Computing | k. A. | 88% | k. A. |

| Play time | 92% | 76% | k. A. |

| Dragon Magazine | k. A. | k. A. | 5/5 |

| PC player | 89% | k. A. | k. A. |

mystery

At the time, critics expressed themselves positively in print magazines about the diskette version of Fate of Atlantis for IBM PCs: Carsten Borgmeier from PC Joker called the puzzles in comparison to the ones in LucasArts' direct predecessor Monkey Island 2: LeChuck's Revenge “essentially life-like more logical ". Knut Gollert also took up this comparison in the Power Play and found the game to be the “best Lucasfilm adventure” because of the “[puzzles] that can be solved after some thought”. Charles Ardai from Computer Gaming World rated the "interlocking puzzles" with several changes of location as "essential for the structure of the game", but found this fact "pleasant", since traveling with simple clicks on a means of transport will be made possible. Ardai was less enthusiastic about the "infinite number of retries" when the player fails at a puzzle. He admitted that this was "convenient" to avoid loading older scores, but it made "psychologically no sense" - there had to be "a better, or at least less obvious, way" that the player would not solve when solving puzzles to make use of previous scores. He also criticized the, in his opinion, too high number of labyrinths and “pixel hunts”, in which you have to find objects in very small image areas with the mouse pointer.

In his review for Play Time , Thomas Borovskis described Fate of Atlantis as a “game for sophisticated tinkerers”, which differs in terms of difficulty “by a few classes from what is currently usual”. Paul Presley of the PC review, however, said it was like most LucasArts adventures "a little too easy to play through". Fate of Atlantis is not too short, it confronts the player "just never really [...] with an enormous challenge", that is, problems "that leave you at a loss for weeks". The puzzles are also "sometimes a bit [...] lateral thinking , with some extremely questionable solutions [that one would never see in a film]". However, these irregularities would be balanced out by the various possible solutions to many puzzles. For his review in QuestBusters: The Adventurers' Journal , Russ Ceccola praised the puzzles as "quite creative and definitely fair"; the problems are “varied” and leave the player “with a strong feeling” that they have “achieved something”.

service

Borgmeier cited the "problem-free" point-and-click control, which, according to Guido Alt from the magazine Aktueller Software Markt, "contributes to the fun of the game" as a "slightly revised user guidance [...]." Ardai was of the opinion that this type of operation was conducive to the flow of the game and that it "simplifies most interactions so far" that "they can be carried out with a minimum of effort". He described the lack of certain command verbs and a “certain stylization of interaction” as a striking feature, ie a simplification of a complex chain of actions into a short, more abstract command. However, no text parser is perfect, and the present one enables at least a “gaming experience with little frustration”. Gollert noted that "clicking on objects as small as a pixel" occasionally caused problems, but that was not particularly significant.

Presley praised SCUMM as "one of the most popular and user-friendly systems that has ever appeared in a computer game". It is superior to comparable point-and-click engines in that "Lucasfilm does not [rely on it all the time and certainly does not shy away from [e] adapting, changing or omitting it for certain sections of the game". Ceccola liked the specific interfaces for more complicated puzzles like the Atlantic robot, which he said "[worked] pretty well" and "[helped] move the plot forward." He also found the controls in the action sequences “not too difficult”; it is "even fun to learn". Presley noted that these sections "harmonize so well with the rest of the game, you barely notice you're suddenly using a completely different set of controls." The action sequences would separate the scenes from each other and "[occur] just often enough to offer plenty of variety in the game". He also commented amicably on LucasArts' decision not to let the player skip these sections, which gives the feeling that they are "part of the story".

Replayability

The feedback on the three game paths was very positive. Hartley, Patricia Lesser and their son Kirk pointed out in Dragon Magazine that this feature guaranteed replayability and was one of the most appealing aspects of the game. They called the team path the "most fun" option. Ardai found that Fate of Atlantis contained "far more than an ordinary game" through the three paths and that the campaigns were "more than lip service to the goal of interactivity". He was enthusiastic about the “extraordinary effort” with which the developers “would have [created] a game that adapts to the interests of the individual player”. He concluded: "[Never] before has a game paid so much attention to the needs of the player." Ceccola found this "flexibility" to be "refreshing"; it makes "the game worth every penny".

Presley, Ardai and also David Upchurch from The One Amiga were a little disappointed that the three paths merge again in Atlantis and that the climax of the story takes place in all variants. A continuation of the differences in the plot to the end would have increased the motivation to play again. In his review for CU Amiga , Tony Gill noted, “Although paths cross in key positions, there are many occasions when you have to solve completely different puzzles. For this reason, you can really play the game more than once and treat yourself to a second helping of fun. ”Ardai gave the Indy quotient an amicable assessment: although he suspected that only a few players would try to achieve a perfect score, it was nevertheless Credit to LucasArts for the fact that the option exists in the first place. Presley liked the random number generator, which slightly adapts certain elements of the puzzle with each run, so that the feel of the game changes a little each time.

Staging

history

The story of Fate of Atlantis earned a lot of praise . Ardai praised the setting as an "appropriate mix of seriousness, silliness, sincere science and mystical hocus-pocus". He thought the story was "strong enough [...] to hold its own against each of the Indy films". In contrast to Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The graphic adventure , which contained a lot of well-known things because of the original film, offers Fate of Atlantis "suspense and a true urge to discover [...] in large doses". It is the first time that players get the chance to discover a new Indiana Jones story together with the characters. One could also "easily imagine [the game] being filmed and released as the fourth Indiana Jones film". According to Alt, Fate of Atlantis even provided "material for three films". The game is a "worthy continuation of the [series]"; "Even a film couldn't be better". Ceccola believed the game would make the best motion picture of the series if George Lucas could convince actor Harrison Ford to re-appear. Gill thought that the story could come word for word from an Indiana Jones film, and Hans Ippisch also wrote in the Amiga Games that it would "make an excellent film".

Presley contradicted this, who despite the "film-ready presentation [...] identified a little too much unnecessary travel" in the game as an obstacle to a theatrical implementation. Stevie Kennedy described his only point of criticism in Amiga Computing that the protagonist and also the player were too clear about the further course of the plot - although Fate of Atlantis is neither predictable nor boring, it could be "a little too much when [ read one] a riddle book and not a computer novel ”. Andy Nuttal from Amiga Format wrote that the plot was "pretty linear" compared to the one in Monkey Island 2 , although despite this minor criticism he did not advise against buying it. The story is "littered with elements that are really funny".

Gollert described the humor as "subtle" and no longer comparable to "the sometimes rough slapstick from Monkey Island 2 ". His colleague Richard Eisenmenger jumped to his side and described the joke as "much more stylish", whereby in particular "[t] he sayings by Harrison Ford [...] came across as perfect". Both reviewers also praised the snappy conversations between Indy and Sophia. Borgmeier also attributed an "enormous entertainment value" and a major contribution to "the dense atmosphere" to the "refreshing" and "peppery" dialogues. Presley lamented the characterization of Indiana Jones; the protagonist of Fate of Atlantis reminds with his tendency to "make a fool of himself [...] more of a Saturday morning cartoon character". Although the same is true for the other characters, they are only unsuitable for a movie, but perfect for a game. Alt, however, praised the personality of the protagonist: Indiana Jones acts “in the game exactly as he was portrayed in the films”. “An involuntary caricature of the character” was “thankfully avoided”. Antje Hink from Aktueller Software Markt and Ippisch were impressed by the “good German translation”, which “just oozes with humor”.

graphic

Borgmeier found the graphics “huge” and spoke of “beautifully drawn figures” and “no less beautiful backgrounds”. Alt wrote that with the "technical realization [... better] than ever before with any other program from Lucasfilm". “Graphically, they have once again outdone themselves”, and each screen is “a treat in itself”. He added: "Enriched by perspectives and intercuts , as we know them from the cinema, a real ' cinemascope feeling' arises here ." Gollert and Eisenmenger called the graphics "[dreamlike]" and "superb", the latter adding that "Every minimal scene [...] is packed into a huge graphic scenario" and the game offers "smooth [,] flicker-free animations".

Ardai wrote that the settings were "as lush and exotic as one could wish for." Each environment is presented with “distinctive background drawings and detailed foreground animations”, with “many […] locations […] several screens wide” and showing “exceptionally smooth scrolling”. He criticized, however, that “most places, as picturesque as they may be, only have a few screens” - this is acceptable for a film, but less so for a game whose goal is to interact with the environment. In addition, "various figures are still (literally) missing the finishing touches".

Ceccola, on the other hand, found that the characters looked good and moved fluidly, even though they were "[in some scenes] not as detailed as the background". He emphasized that the interactivity of the opening credits and the opening sequence meant that the game started more interestingly than almost any other before and was staged like a film from the start. This “unique approach” can also be seen in the “film-like scenes that seem to come directly from the head of a cameraman” up to the “credits that are played over the last scene”. There are “a number of cinematic settings” that appear “realistic”, although the animated cutscenes are “fun to watch” and “show the artistry of the designers and animators”. Several reviewers, including Alt and Ceccola, were impressed by how the screen initially remains completely dark when entering a dark cave in the game and then gradually brightens until outlines can be seen - similar to the adaptation of the human eye is the case.

sound

Borgmeier wrote that the music and the sound effects were "the finest". Alt was of the opinion that the game offers a “perfect adaptation of the title theme, as well as the music that fits the situation”. According to Eisenmenger, the sound “fits in stylishly with the current environment”. He praised: "The music [...] has film music standard - in composition as well as in the arrangement." The "melodic film music [...] accentuates the entire game [...] without being annoying". The iMUSE system received special praise . For Ceccola “it completes the feeling of playing a film”. Presley found that the transitions between the pieces of music when switching to another screen were significantly less noticeable than in Monkey Island 2 and that the system therefore “worked much better”. He advised players to get a Roland sound module in order to get the "immense pleasure" of listening to the cover story. Ardai was disappointed in the diskette version with the "remarkable lack of sound effects " that the "opulent soundtrack [does not compensate for]". A voice output for the dialogues is "sorely missed", and one "wishes after a few hours of reading [, ...] that at least a little of it was recorded". Ceccola also recommended LucasArts to record a voice output in the case of a CD version, as it would "dramatically improve the game". For Thomas Brenner from PC Games , the lack of digital sound effects was the game's only weak point.

Later publications

Amiga

The Amiga implementation was harshly criticized for its technical inadequacies. In Play Time, for example, Ippisch generally complained about a clear time delay between a mouse click and the system's reaction; the character also literally sneaks across the screen. Gollert criticized the fact that the slow speed “put the crown on everything” and that players without a turbo card that increases the computing power would have to reckon with reaction times of at least three seconds. Upchurch criticized the slow game play in busy scenes, such as a marketplace with many characters. The game was delivered on 11 floppy disks. In this context, Gill called a hard drive as an alternative to a floppy disk drive "a necessity, not a luxury". Upchurch ruled out a second floppy disk drive as a further possibility, because even then it was necessary to change floppy disks three or four times when loading, which "does not make life particularly bearable".

Ippisch examined the technical background of this problem: he spoke of "[h] errlich confused [n] filing tactics" with the files, through which "[o] without any recognizable logic [...] between the individual disks" is jumped back and forth. The criticism of the artistic aspect of the graphics, however, was largely good. Only Gollert called the game "graphically gracious" because it shines "with incomparable colorlessness even for Amiga standards". Ippisch, on the other hand, remarked that the graphics were "well done" even with fewer than 32 colors displayed at the same time. Upchurch found the implementation graphically “appealing”, albeit “a bit pixelated” and “washed out”. Borgmeier wrote in the Amiga Joker that with the porting you would get "quality [...] served by the pound" and "every single detail is right". Gollert described the game on the Amiga as "musically mushy". Kennedy was also of the opinion that the pieces could “get on your nerves after a while”. Ippisch, however, called the sound “acceptably well done”. Borgmeier particularly praised the translation, which, according to him, avoided copying previous errors from the PC version.

" Talkie " edition

The additions to the “ Talkie ” edition on CD-ROM received a lot of praise. For Ardai, this revised publication, in contrast to many other CD versions from this time, bore a "quality stamp". Fate of Atlantis on CD would make it difficult to revert to the floppy disk version or even to non-speech games at all. The spoken texts and digital sound effects underline how "first class" the game is. He paid tribute to the cast of the dubbing and called Doug Lee, the Indiana Jones spokesman, a "real Harrison Ford vocal double". In addition, the voice output increases the humor and improves the characterization of minor characters who originally appeared “flat”. Heinrich Lenhardt from PC Player thought it was "[s] a shame that [ss] [...] Ford does not lend the PC-Indy the voice". But even without the “celebrity factor”, LucasArts delivered a “professional [...] setting”, which means a “big atmosphere bonus”.

Both Lenhardt and Brenner assessed positively that the " Talkie " edition hardly takes up any space on the hard drive. Ardai also benefited from the elimination of the "tiresome copy protection mechanism" for the CD version (at that time, due to the limited use of CD burners, such a system was only necessary for easily copied disk games). Only reading data in the middle of a sentence, which would result in a "[S] tottern" in the voice output, was "regrettable" for Ardai. The enclosure of a solution Help greeted Lenhardt as "most welcome". The Computer Gaming World summarized the CD version as a “nice approximation to an Indiana Jones film”, which is comparable to the transition from silent to sound film. Michael Anton wrote in Current Software Market that the Macintosh implementation based on the “ Talkie ” edition “does not need to hide from the PC model”, as well as that “the graphics and sound [come across] are excellent”. .

Awards and retrospective evaluation

Fate of Atlantis is widely regarded as the best Indiana Jones computer game of all time as well as a classic of the adventure genre and is considered one of the most popular titles by LucasArts. Even when the game was first published, reviewers gave the game numerous publication-specific prizes: Play Time the “Super Hit”, the PC Joker the “Joker Hit”, Current Software Market the “ASM Hit” and the “Game of the Month” Power Play was given the rating "particularly recommendable" and the Amiga Games the " Amiga Games Award". Journalists and readers of various publications such as PC Games , Game Bytes , and Power Play crowned it the best adventure game of the year. Also, it was Fate of Atlantis publicly recognized with awards: in the Golden Joystick Awards 1992 as "licensed Best computer game," the Industry Dinner ( INDIN ) as "Best RPG / Adventure" and at the European Computer Trade Show Awards 1993 as "Best computer game" . At the seventh International Computer Game Developers Conference in 1993, Hal Barwood and Noah Falstein, among others, were awarded pins by their industrial colleagues to honor their contribution to the development of an extraordinary computer game. In a 1996 list of the 150 best games of all time in the Computer Gaming World , Fate of Atlantis was ranked 93rd. Two years later, PC Gamer named it 41st of the 50 best games.

Successors and adaptations

Adventures

Already in the credits of Fate of Atlantis a possible successor is suggested, in which a younger Indy should appear. This meant the game Young Indiana Jones at the World's Fair , an idea by Brian Moriarty, the creator of the fantasy adventure Loom . According to Moriarty, the storyline of this educational game developed for Lucas Learning was "entirely based on historical facts". The story was about the invention of the machine gun - breaker mechanism for double-decker aircraft in the First World War . The project was a tie-in product for the history educational television series The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones , but like the television production, it was ultimately discontinued. William Eaken mentioned in an interview that "a lot of people didn't like [the game] very much" and that he had heard "horror stories" about it.

Next, Joe Pinney as project manager and Hal Barwood as story consultant came up with the story Indiana Jones and the Iron Phoenix Ⅱ . Barwood had the idea of having Nazis hiding in Bolivia after World War II look for an artifact with which they could bring their leader Adolf Hitler back to life. The action was set in 1947 and dealt with Indy's search for the Philosopher's Stone , in which his paths crossed with the Soviet secret agent and " Nazi hunter " Nadia Kirov. Although information about the course and the termination of the project contradict each other, problems are consistently reported that prevented the successful completion of Iron Phoenix . Pinney is said to have left LucasArts quite suddenly at an early stage of development, so that his colleagues Aric Wilmunder and Bill Stoneham had to take over the project management. Wilmunder was responsible for developing the story into a design document with specific game environments and cutscenes, with which the actual production could then begin.

Soon after, however, Wilmunder was informed by his superiors that in addition to his role as project manager for Iron Phoenix, he should also work on the problematic space adventure The Dig . Meanwhile, there was tension among the Iron Phoenix artists . The chief animator Anson Jew should make the characters more than twice as large as in previous LucasArts games; However, he had only a very limited number of colors available, since a larger palette would have meant a reduction in the colors for the realistic backgrounds drawn by Stoneham. This resulted in a cartoon- like Art Deco style for the characters, which Jew described as a kind of stopgap solution after his demands for greater depth of color had been rejected. In the meantime, LucasArts began working with an external software developer for the first time in the company's history . A company from the Canadian Montreal was awarded the contract because it is one game project on LucasArts financing tax subsidies promised, so you hinwegsah about the lack of development experience of this team. Wilmunder later recalled "several warning signals", for example, the Canadian studio had not delivered any animations to LucasArts and the external employees were partly working on other projects, as was evident during control visits.

When the collaboration with the developer in Canada ended after six to eight months, Wilmunder concentrated more and more on The Dig . After that, Iron Phoenix experimented with video recordings of actors in connection with Stoneham's backgrounds in order to create a "cross between adventure game and real cinema". After 15 months of development, the game was finally presented at the European Computer Trade Show . When the German partners of LucasArts found out how strongly the game treated the topic of neo-Nazism , they expressed great concerns about the marketability in Germany. Since the German sales market for adventure games was now generating higher revenues than in the United States , it was feared that the development costs of Iron Phoenix would ultimately exceed the lower sales and the project was stopped. Barwood later commented negatively on the plot: "If we had thought more about the story beforehand, I would have noticed that she was tactless, so I don't regret her loss." Wilmunder also admitted that his superiors' decision was understandable and he would rather have delivered no product than a bad product. The comic artist Lee Marrs later processed Iron Phoenix into a four-part series for Dark Horse , which appeared monthly from December 1994 to March 1995.

Barwood mentioned another sequel game called Indiana Jones and the Spear of Destiny , which he attributed to Wilmunder. It was also planned as an external development by a small Canadian studio, but was discontinued due to a lack of project management . Statements by Wilmunder and other developers contradict this and instead associate this anecdote with Iron Phoenix . It can therefore be assumed that Spear of Destiny with its story about the Holy Lance has always existed exclusively as the Dark Horse comic series published in 1995. Wilmunder only stated that he had later thought about a precursor to the second movie Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, which was to deal with the recovery of the remains of Nurhaci and Indy's first meeting with his young sidekick "Shorty".

Others

As early as the early 1990s, it became known that Fate of Atlantis was being prepared as the script for the fourth part of the Indiana Jones film series during development . So it was planned to publish the game and the film as complementary products and LucasArts pushed ahead with discussions about a film adaptation. Harrison Ford feared at the time, however, too much with the role of Indiana Jones to be identified and was not prepared to occur in another film in the series. Because of this, raising capital eventually became impossible and production had to stop. In a press conference for the fourth movie Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull , George Lucas confirmed that a film adaptation of Fate of Atlantis had been considered. As a reason for the failure of the project, he stated that the script of the game did not offer enough material for a film adaptation.

Also during the development of Fate of Atlantis , the cartoonists William Messner-Loebs and Dan Barry began adapting the story for a Dark Horse series, which was initially titled Indiana Jones and the Keys to Atlantis . The one arcade game resembling Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis: The Action Game from developer Attention to detail was almost simultaneously released with the Adventure counterpart and is based loosely on the plot. Heinrich Lenhardt described it as the "worst Indy game of all time" and as "even more stupid, even nastier, even worse all round" than its predecessor, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Action Game, produced by US Gold .

Years later, Barwood ventured into a casual game : he designed an adventure game with action and puzzle elements in which you control the character from a bird's eye view . Designed as a window application for Microsoft Windows, it is divided into short game segments of around 30 minutes in length. The special thing about it is that a random number generator generates a new game from a series of predefined elements each time you restart the game. The story was originally set in a post-apocalyptic future, but at the behest of LucasArts' marketing team, Barwood had to adapt its concept using the Indy license, as Indiana Jones and his Desktop Adventures promised higher sales. The plan didn't work out, however, as critics placed higher expectations of LucasArts in terms of graphics and sound and therefore panned the game.

A few years later, three-dimensional action adventure games grew in popularity, so Barwood was interested in developing a game in this genre. He wanted to use a story about flying saucers set in America in the 1950s , but had to discard the idea as it was withheld by Lucasfilm for Kingdom of the Crystal Skull . Instead, Barwood eventually designed the action adventure Indiana Jones and the Tower of Babel , in which he had the opportunity to reinstall Sophia Hapgood. From his first draft of the plot, he adopted the Soviets as antagonists, since he felt that the Nazis had been used too often as Indy's opponents.

literature

- About Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis

- Judith Lucero: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis Handbook. LucasArts Entertainment Company , San Rafael, California 1992 ( online ).

- Judith Lucero: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis IBM Reference Card. LucasArts Entertainment Company, San Rafael, California 1992 ( online ).

- Judith Lucero: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis: The Hint Book. LucasArts Entertainment Company, San Rafael, California 1992 ( online ).

- Referenced works

- Atlantis: The Eternal Quest. In: Pat Daniels, Anne Horan (ed.): Mystic Places (= Mysteries of the Unknown. 1). Time-Life Books, Morristown, New Jersey 1987, ISBN 0-8094-6312-1 , pp. 14-36 ( online ).

- Paradise Lost. In: Pat Daniels, Anne Horan (ed.): Mystic Places (= Mysteries of the Unknown. 1). Time-Life Books, Morristown, New Jersey 1987, ISBN 0-8094-6312-1 , pp. 6-13 ( online ).

- L. Sprague de Camp : Lost Continents: The Atlantis Theme in History, Science, and Literature. Gnome Press, New York 1954.

- Ignatius Donnelly : Atlantis: The Antediluvian World. Harper & Brothers , New York 1882 ( online ).

- Benjamin Jowett : Critias, or The Island of Atlantis. In: Charmides and Other Dialogues (= The Dialogues of Plato. 4). Hearst's International Library , New York 1914, pp. 377-398 ( online ).

- Benjamin Jowett : Timaeus. In: Charmides and Other Dialogues (= The Dialogues of Plato. 4). Hearst's International Library , New York 1914, pp. 363-377 ( online ).

- Otto Muck : Atlantis: The world before the flood. Walter-Verlag , Olten / Freiburg im Breisgau 1956 ( online ).

- Charles Pellegrino: Unearthing Atlantis: An Archaeological Odyssey. Random House , New York 1991, ISBN 0-394-57550-4 .

- Dorothy B. Vitaliano: Legends of the Earth: Their Geologic Origins. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1973, ISBN 0-253-14750-6 .

Web links

- Official LucasArts website ( Memento from December 23, 1996 in the Internet Archive )

- Official Indiana Jones page ( Memento of 14 March 2007 at the Internet Archive , English)

- Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis at MobyGames (English)

- Retro circle - discussion of the game

- GameStar interview with translator Boris Schneider-Johne

Remarks

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g Judith Lucero: Credits . In: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis Handbook . LucasArts Entertainment Company , 1992, pp. 14-15 ( steamstatic.com [PDF]).

- ↑ a b c Daemon Hatfield: Interview: SCUMM of the Earth . In: IGN . IGN Entertainment. May 15, 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- ↑ a b Judith Lucero: This is how it is played . In: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis Handbook . LucasArts Entertainment Company , 1992, pp. 3-5 ( steamstatic.com [PDF]).

- ^ A b c d Judith Lucero: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis IBM Reference Card . LucasArts Entertainment Company , 1992, pp. 1 ( archive.org [PDF]).

- ^ Judith Lucero: The Wits Path: Hints - Thera . In: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis: The Hint Book . LucasArts Entertainment Company , 1992, pp. 34 ( archive.org ).

- ↑ a b c Judith Lucero: Special controls . In: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis Handbook . LucasArts Entertainment Company , 1992, pp. 7-11 ( steamstatic.com [PDF]).

- ↑ a b c d Judith Lucero: The ways . In: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis Handbook . LucasArts Entertainment Company , 1992, pp. 7 ( steamstatic.com [PDF]).

- ^ Judith Lucero: Before the Paths Diverge: Hints - Azores . In: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis: The Hint Book . LucasArts Entertainment Company , 1992, pp. 11 ( archive.org ).

- ^ A b c Andy Nuttal: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . In: Amiga format . No. 43 . Future Publishing , February 1993, p. 72-73 ( archive.org ).

- ^ Judith Lucero: More game options . In: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis Handbook . LucasArts Entertainment Company , 1992, pp. 11 ( steamstatic.com [PDF]).

- ^ Judith Lucero: The Indy Quotient (IQ) . In: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis Handbook . LucasArts Entertainment Company , 1992, pp. 12 ( steamstatic.com [PDF]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Paul Presley: Indiana Jones & the Fate of Atlantis Review . In: PC review . No. 11 . EMAP Images, September 1992, p. 40-44 ( archive.org ).

- ^ Judith Lucero: Our Philosophy . In: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis Handbook . LucasArts Entertainment Company , 1992, pp. 13 ( steamstatic.com [PDF]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Mike Bevan: The Making of Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . In: Retro Gamer Magazine . No. 51 . Imagine Publishing, 2008, p. 44–49 ( archive.org [PDF]).

- ^ Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis on the back of the packaging . LucasArts Entertainment Company , June 1992 ( archive.org ).

- ^ Robert Siegel, Melissa Block: Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade (Of Lost Mail) . National Public Radio . December 17, 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- ↑ a b c d e f David Upchurch: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . In: The One Amiga . No. 52 . EMAP Images, January 1993, p. 54-57 ( archive.org ).

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Klaus Kerner: Tell me, did you find a lock for my key? […] What are you waiting for? Open it up. [...] Marcus Brody: My God, Indy, a small metal bead. "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Indiana Jones: Klaus Kerner, how? Marcus Brody: Good God, Indy, the man is an agent from the Third Reich! What does a SPY do with a FAKE STATUE? "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Marcus Brody: Look what our friend still had with him, an old edition of Bild der Archeologie, and there you are in ICELAND. Indiana Jones: Yeah ... dig supervisor on the Jastro Expedition, my first real job. Marcus Brody: Who is this woman? Indiana Jones: Sophia Hapgood. She was my assistant, a spoiled rich brat from Boston who rebelled against her parents. Marcus Brody: Where is she now? Indiana Jones: She gave up archeology to become a MEDIUM. "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Indiana Jones: Come on, Sophia, give me the collar! Sophia Hapgood: I can't. For ten years I NEVER gave it away and now I can no longer force myself to do it. "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Indiana Jones: I've never seen this style, but it was OLD. […] Marcus Brody: Indy, Kerner found YOU, what if he finds YOU? We should warn this woman. Indiana Jones: You are right. And I want to know more about this statue! "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computerspiele , 1992: “Sophia Hapgood: Here, my friends, ATLANTIS is as it could have looked in its heyday, glorious, wealthy, socially and technically advanced beyond our wildest dreams! […] Whatever happened, panic must have gripped Atlantis' citizens on the terrible day that proud Atlantis sank into the waves ... or maybe it was a volcanic eruption, and even TODAY something could still be found. [...] ... I can present you NUR-AB-SAL, the great Atlantic god of ... Indiana Jones: Fraud! "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Sophia Hapgood: Come on, Mister. I need to talk to you a few bars. […] OH NO! Indiana Jones: Crap! Kerner was here first! "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Sophia Hapgood: Kerner missed the main prize… Indiana Jones: What? Sophia Hapgood: ... my collar. "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: Hermocrates: ... and it is said that the residents neither owned nor needed horses. Orichalcum , the metal that glitters like fire, was their replacement. They poured it into little pearls and used them like we did coins, statues paid to do the work like magic.

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Sophia Hapgood: Pay close attention. This pearl is made of ORICHALCUM , the mysterious metal that Plato first mentioned. I now put it in the mouth of the medallion. [sic] Did you see that? Indiana Jones: Yeah. Creepy. Did you pay your electricity bill? Sophia Hapgood: That was Nur-Ab-Sal. His spirit is near! "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computerspiele , 1992: "Sophia Hapgood: Listen to this: ... 'Germans claim victory in the worldwide race to split the uranium atom." 'Scientist Dr. Hans Übermann announces plans to develop new energy sources for the Third Reich. ' Indiana Jones: So? Practical results are years away. Sophia Hapgood: Of course. That's why they're looking for the POWER OF ATLANTIS. "

- ↑ Eugenio Caponetti, Armetta Francesco, Delia Chillura Martino, Maria Luisa Saladino, Stefano Ridolfi, Gabriella Chirco, Mario Berrettoni, Paolo Conti, Nicolò Bruno, Sebastiano Tusa: First discovery of orichalcum ingots from the remains of a 6th century BC shipwreck near Gela ( Sicily) seabed . In: Mediterranean Archeology and Archaeometry . tape 17 , no. 2 , April 2017, ISSN 1108-9628 , p. 11-18 , doi : 10.5281 / zenodo.581716 .

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Sophia Hapgood: Pssst! ... I am receiving something! Nur-Ab-Sal SPEAKS ... he asks us ... what ... a book ... yes ... to find the LOST DIALOGUE PLATOS! "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: "Indiana Jones: I think BARNETT COLLEGE owns the Ashkenazy / Dunlop / Pearce / Sprague / Ward collection!"

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: Hermocrates: In shame I hereby revoke Critias [sic] time and place. When translated into Greek, he was wrong by a factor of 10. Instead of 3,000 miles, Atlantis can also be 30,000 miles away, or just 300 miles off our coast. It is also possible that the kingdom fell 100,000 years ago or only 1,000 years ago.

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Indiana Jones: Didn't you notice Plato's error by a factor of 10? Sophia Hapgood: Well, he mixed up his numbers a bit, why should that be so important? Indiana Jones: So Plato's mistake also affects distances. Sophia Hapgood: Yes, and? Indiana Jones: If Plato is right, Atlantis is in the MEDITERRANEAN. Sophia Hapgood: You mean: 300 miles from Greece instead of 3000. Indiana Jones: Yes! The cradle of civilization. Sophia Hapgood: You could be right. He once told me he came from the middle of the world - Mediterranea. That is the Latin expression for the Mediterranean. "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold computer games , 1992: Hermocrates: Gates of the kingdom only opened with the help of special stones. At the outposts a sunstone was enough [...] In the large colony a moonstone was needed [...] To reach Atlantis, a world stone was added [...]

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Alain Trottier: I also know where you can find an ENTRANCE that leads directly to the Lost City. […] He is on the island of THIRA, south of Greece. […] You read about the Small Colony in Plato's Dialog, right? [...] I am convinced THIRA is the SMALL COLONY ... and I think it is the entrance at the same time. "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Indiana Jones: Either Atlantis is a little smaller than we thought, or we are looking at a model! Sophia Hapgood: set up exactly as Plato described it, in three concentric circles. "

- ↑ Michael Anton: The search for Atlantis . In: Current Software Market Special . 17 (special edition). Tronic-Verlag, 1992, p. 16 ( archive.org ).

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Nur-Ab-Sal: The woman who once WAS is now THE KING WHO WILL BE ETERNAL! So speak to me in awe. "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Indiana Jones: Bones never grow that way naturally. Where do you think they come from ... Mars? ... straight from hell? "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: Hermocrates: ... when the water rose around their city, the kings tried to stop fate. Since mortals would never rule the sea, they built a Colossus that would make them gods through Orichalcum , ten pearls at a time. Nur-Ab-Sal was such a king. It was he, say the Egyptians, who forced men into the Colossus and made them monsters of nature when the celestial spheres were well aligned according to his direction.

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Sophia Hapgood: What have you been up to now, Indy? Indiana Jones: I think I turned it on. Dr. Hans Übermann: You see, Kerner? I knew Jones would still be useful to us! Indiana Jones: Kerner! That's why it smelled like rats here. "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Indiana Jones: Didn't you notice those deformed bones? Dr. Hans Übermann: Failed experiments. […] Indiana Jones: Maybe they were all too human like you. Dr. Hans Übermann: You mean sub-people! You were destroyed by your own physical flaws as you bathed in the enormous power of this machine. Klaus Kerner: Fortunately, we don't have any such flaws. "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Indiana Jones: Great. Send me a postcard from Valhalla. [...] Dr. Hans Übermann: You can't go now. We will start the experiment. […] And we still need a first guinea pig… […] Well, if you would kindly step on the platform… Klaus Kerner: NO! [...] If someone becomes God here, it will be me! "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Dr. Hans Übermann: Plato suggested ten pearls. Let's try that. Indiana Jones: Stop! What about Plato's [sic] TENFOLD ERROR? […] Almost all of Plato's numbers were wrong by a factor of ten. [...] Klaus Kerner: He could be right. We should divide by ten. Try ONE pearl. "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Dr. Hans Übermann: Move! Before my people here force you! […] Indiana Jones: I hope for you that [sic] this doesn't work out. [...] As soon as I am a god, I will send you to hell. [...] Ever heard of God's wrath? [...] Dr. Hans Übermann: You are planning something against me, despite my generosity. […] Stand aside, Jones! […]… ONE HUNDRED PEARLS! Look forward to my revenge! "

- ^ Hal Barwood: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . Softgold Computer Games , 1992: “Indiana Jones: You know, a lot of my discoveries really sound like mythical stories, even to me. But this time at least I have proof. Sophia Hapgood: Well ... but maybe not ... [...] What was that for? Indiana Jones: To ease the pain. "

- ↑ a b c d e Hal Barwood: Afterword . In: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis . No. 1 . Dark Horse Comics , January 1991, p. 28-29 ( archive.org ).

- ↑ Chris Capel: LucasArts' Secret History: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis - Plato's Lost Trivia . The International House of Mojo. September 1, 2008. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Mishan, Eddie: Interview with Hal Barwood . The Indy Experience. October 10, 2004.

- ↑ a b c d e f Hans Frank: Interview: Hal Barwood . Adventure meeting. July 18, 2007. Archived from the original on May 27, 2008. Retrieved March 25, 2010.