Mi'kmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also Míkmaq , Micmac or Mic-Mac ) are an Indian people who live in eastern North America . Today there are 29 Mi'kmaq First Nations in Canada , but only one federally recognized tribe in the United States , known as the Aroostock Band of Micmac . The former residential area of the Mi'kmaq included the maritime provinces of Nova Scotia , Prince Edward Island , parts of New Brunswick / Nouveau-Brunswick and the Gaspé Peninsula in Québec .

Surname

Some sources suggest that the name is meant to mean allies , but this claim is controversial. Rather, the name goes back to the fact that the Indians are friends with Nikmaq! greeted, which means my brothers , my relatives or my family . Marc Lescarbot reported in 1606 that the Indians taught the French and Basque fishermen this greeting and the French soon referred to the Mi'kmaq as Notres nikmaqs . This added an s to the plural, a tradition the British continued, giving rise to forms such as Micmacs or Mic-Macs . Other variants of the name are Migmagi , Mickmaki and Mikmakique .

The Mi'kmaq include a large number of sub-groups that were historically referred to by the French by different names due to their settlement areas - for example, they called the Mi'kmaq groups in eastern Quebec Gaspésiens de Le Clercq and Mi'kmaq groups in Nova Scotia and parts of the bordering US state of Maine as Souriquois de la Tradition jésuite or just Souriquois , which means something like "salt water people". The English name Tarrantine (Eng. Tarrantiner ) comes from the 17th century . The name in use until the 1980s was Micmac (and is partly, as is still common in ethnology ), but today it is considered colonial . Today Mi'kmaq is the accepted spelling, and it is also closer to pronunciation.

The Mi'kmaq themselves use different spellings depending on the dialect: On Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia Mi'kmaq (singular Mi'kmaw ), in New Brunswick Miigmaq (singular Miigmao ), the Gespe'gewa'gi First Nations in Québec prefer Mi 'gmaq , also Mìgmaq (singular Mìgmaw or Migmewaj ) can be found in some books . Please note that the plural in the above variants is Mi'kmaq , while the singular is Mi'kmaw and its variants.

There are various explanations for the origin of the name Mi'kmaq , but according to the Mi'kmaw Resource Guide , the name means "The Family", indicated by the first letter M and is always plural. Other similar terms, but not synonymous , are: Nikmaq - "my family", Kikmaq - "your family", Wikmaq - "his / her family". The variant Mi'kmaw has two grammatical functions: first, it is the singular of Mi'kmaq, and second, the adjective in cases where it precedes a noun, e.g. B. Mi'kmaw People , Mi'kmaw Treaties, Mi'kmaw Person (Indian) and Mi'kmaw Canoe. The word Mi'kmaq is therefore never used as an adjective.

The Mi'kmaq referred to themselves as Lnu (singular and adjectival noun, earlier: L'nu ; the plural is Lnúk , Lnu'k , Lnu'g , or Lnùg , read: "Ulnoo" or "Elnu"), literally means something like " human beings" or "the people". The Maliseet living in the south called their former enemies and later allies, the Mi'kmaq, as Matueswiskitchinuuk ("porcupine people", because they decorated their clothes with porcupine bristles), while the Beothuk on Newfoundland called them Shonack ("evil or bad people") ), as they had to defend themselves against the Mi'kmaq who were armed with French rifles and advancing their land.

language

The Míkmawísimk , Mi'gmawi'simg or L'nui'sin (in Canada today the spelling Mi'gmaq is preferred, in English Mi'kmaq is common) belongs to the Eastern Algonquin languages and is now used next to English or French spoken by around 11,000 tribesmen. They are spread over about 15 larger and a further dozen smaller reserves . The language used to be called Micmac , but today the spelling Migmaw or Mikmaw is increasingly being used in English . The Mi'kmaq use the names Míkmaq , Míkmaw or Mìgmao for their language, depending on the dialect, in addition to the names mentioned above .

The language gained a certain worldwide attention when in 2019 the then 16-year-old Emma Stevens from the province of Nova Scotia sang the Beatles song "Blackbird" in Míkmaq. The YouTube video was viewed over a million times in early 2020.

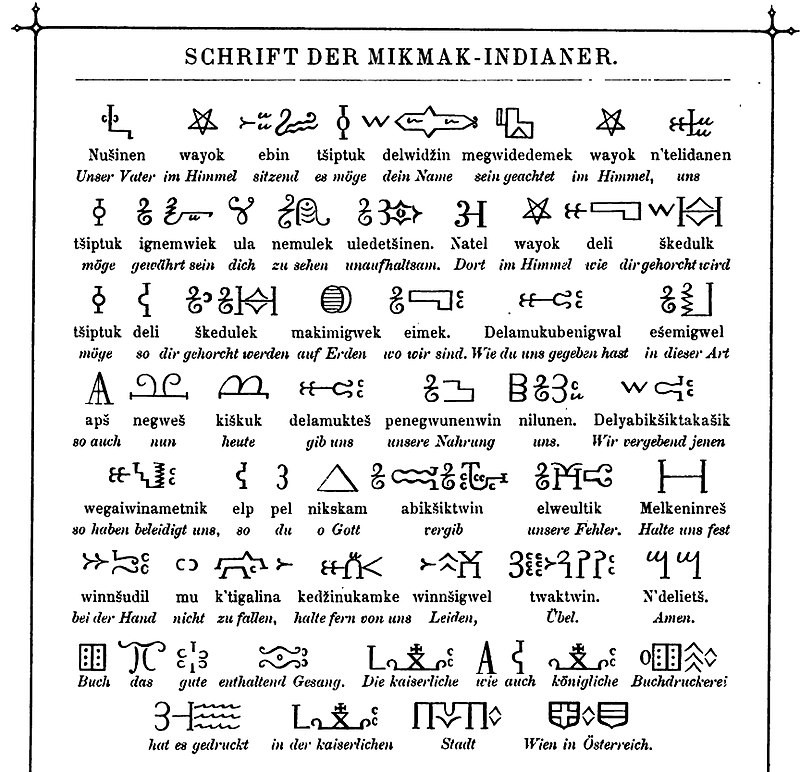

There are significant differences between the individual Mi'kmaq dialects, so that, for example, the Mi'kmaq in Quebec have problems understanding tribesmen from Nova Scotia. Due to the loss of the traditional way of life, the Mi'kmaq language plays an identity-forming role. The Mi'kmaq had no actual writing , but used symbols that they drew on birch bark or leather.

font

In the middle of the 17th century, the Catholic missionary Chrestien Le Clercq developed a hieroglyphic script consisting of over 5,000 characters as a memory aid for prayers, hymns and the catechism. It was captured on birch bark and enthusiastically accepted by the Mi'kmaq and very quickly indigenized . The writing had a decisive influence on the history of the people: It led to a far-reaching success of the Christian mission , consequently to a new cultural identity and the formation of Catholic solidities as new political organs, when the influence of British Protestant suzerainty increased.

After the writing became widely used, it was modified somewhat in 1939 by Father Pacifique de Restigouche for the translation of the Bible and used for textbooks and in the newspaper The Micmac Messenger , which appeared in the language of the indigenous people from 1908 to 1942.

residential area

In the 16th century, the Mi'kmaq settled the entire area south and east of the bay of the Saint Lawrence River , which included the maritime provinces of Canada and the Gaspé Peninsula . This stretch of land was heavily forested, flat, covered with numerous lakes and criss-crossed by many watercourses that flowed into natural harbors along the long, rugged coast. The winters were severe and the short season of growth barely allowed the cultivation of grain or crops. The extensive river system made rapid transport by canoe possible and thus contributed to the preservation of the ethnic identity of the approximately 10,000 tribesmen. The Mi'kmaq defended their tribal territory against various other tribes. They fought against the Saint Lawrence Iroquois and later against the Mohawk around the Gaspé Peninsula, while they had to deal with the Maliseet and Penobscot on their southern border, especially in the valley of the Saint John River in New Brunswick . Mi'kmaq hunters occasionally visited Anticosti Island and they even reached the Labrador coast , where they attacked the Eskimos . The occupation of Newfoundland was accompanied by the early extinction of the Beothuk , in which they played a decisive role.

Mi'kmaq tribal organization

The Mi'kma'ki (Migmagi) tribal area was divided into seven districts (they added an eighth in 1860), corresponding to hunting grounds and residential areas of individual groups (or bands) where they hunted and camped together in spring and summer. At least some of these groups had characteristic symbols, for example a salmon represented today's Listuguj Mi'gmaq First Nation of the Kespek (Gespe'gewa'gi) district in the Restigouchetal and around the Baie des Chaleurs , and the figure of a man with a bow and arrow stood for groups (bands) of the Siknikt (Signigtewa'gi) district in the Miramichi River area .

The districts Kespek (Gespe'gewa'gi), Siknikt (Signigtewa'gi) and Epekwitk aq Piktuk were grouped under the collective name Sigenigt and the districts Eskikewa'kik (Esge'gewa'gi), Sipekni'katik (Sugapune'gati) and Kespukwitk (Gespugwitg) under the collective name Gespogoitg . On the other hand, the district on Cape Breton Island, known as Onamag or Unama'kik (Unama'gi) , became the main district and seat of the Mi'kmaw Grand Council (Santé Mawiómi) and the Great Chief than any other district standing district considered. The great chief once played an important role in the tribe's decisions about war or peace, but since the mid-19th century his functions have only been ceremonial. The adjacent districts of Pigtogeoag and Esgigeoag were subordinate to Onamag and sometimes even had no chief of their own.

The seven traditional districts of Mi'kmaq country

| Tribal territory of all Mi'kmaq | Mi'kma'ki (Mi'gma'gi) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| regional group | Sigenigt | Spogoitg | |||||

| Districts (associated tribal group) | Kespek (Gespegeoag) | Siknikt (Sigenigteoag) | Epekwitk aq Piktuk (Epegoitnag and Pigtogeoag) | Unama'kik (Onamag) | Eskikewa'kik (Esgigeoag) | Sipekni'katik (Segepenegatig) | Kespukwitk (Spopoitnag) |

-

I. Sigenigt

-

- Kespek (Gespe'gewa'gi) District

-

- Gespegeoag / Gespegiag tribal group

- inhabited the district known as Kespek / Gepek ("last land") or Gespe'gewa'gi / Kespékewaq / Kespoogwitunak ("last acquired land"), which included the eponymous Gaspésie peninsula and a wide network of waterways westwards along the Maqtugweg ( the St. Lawrence River ) inland from Quebec , inhabited in the northeast and east, the Gloucester and Northumberland Counties to Mawi Poqtapeg ( Baie des Chaleurs ) and the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the Acadian peninsula , occasionally they even took hunting trips to Natigasteg ("Foreground", "prominent position", ie Anticosti Island), the Restigouche County along the Restigouche River and in the south in Northumberland County along the Miramichi River in New Brunswick (New Brunswick)

- Siknikt (Signigtewa'gi) District

-

- Sigenigteoag / Sigenitog tribal group

- inhabited the district also known as Sikniktuk / Sikniktewag / Signigtewágig or Sgnuoptijg (" Drainage -Platz") in the catchment area as well as the estuary of the Miramichi River and its tributaries, along the Petitcodiac and Nepisiguit Rivers and the Saint John River up to their confluence with the Chaleur Bay or into the Bay of Fundy on the Atlantic coast in the Albert , Kent , Queens , Saint John and Westmorland Counties of New Brunswick (New Brunswick) and Cumberland County in Nova Scotia (Nova Scotia)

- Epekwitk aq Piktuk (Epegwitg aq Pigtug) or Piktuk aqq Epekwitk district

-

- Epegoitnag / Epeggoitg tribal group

- inhabited the as Epelwik / Epekwitk (" Lies / Swims on the water") called Prince Edward Island (Prince Edward Island) in the St. Lawrence Gulf, the south coast of which is the Northumberland Strait, often they did not have their own chiefs or political representatives Mi'kmaw Grand Council and were therefore mostly politically lying west main district called Unama'kik (Unama'gi) on (Cape Breton island) Cape Breton Iceland assumed

- Pigtogeoag / Pigtog tribal group

- inhabited the area around Pictou in what is now Pictou County in northeast Nova Scotia (Nova Scotia) on the south bank of the Northumberland Strait opposite Prince Edward Island to the north, known as Piwktuk / Piktukewaq ("where gas explosions discharge" or "exploding gas")

-

-

Unama'kik (Unama'gi) - Main district and seat of the Mi'kmaw Grand Council

-

- Onamag / Onamagig tribal group

- inhabited the as Unama'kik / Unama'gi or Wunama'kik ("foggy country") called Cape Breton Island (Cape Breton Island) in Nova Scotia (Nova Scotia), on Mniku (English Chapel Island), a small island in Pitu'pa'q ("Inner Sea") or Pitu'pok ("great long salt water") called Bras d'Or Lake in the middle of Cape Breton Island was (and is today again) the seat of the Mi'kmaw Grand Council (dt. Great Council of the Mi'kmaq), the Keptinaq or Saqamaw / Sagamaw (district chief) of the main district traditionally provided the Kji 'Saqamaw or Grand Chief (great chief) in hereditary order .

-

-

II. Spogoitg

-

- Eskikewa'kik (Esge'gewa'gi) district

-

- Esgigeoag / Esgigiag tribal group

- inhabited the district known as Eskikewa'kik / Eskíkeawag or Esge'gewa'gi ("Skin Dressers Territory") along the St. Marys River and in today's Halifax , Guysborough and Antigonish counties in the east and along the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia (Nova Scotia )

- Sipekni'katik (Sugapune'gati) District

-

- Segepenegatig / Segepenegatig tribal group

- inhabited the district called Sipekne'katik / Sipeknékatikik / Sikepne'katik or Sugapune'gati ("Ground Nut Place" or "Wild Potatoe Area") in the area around the city of Truro , the adjacent Cobequid Bay and along the Annapolis River and in Annapolis Valley , lived in Colchester , Hants , Lunenburg , Kings and Annapolis Counties in west-central Nova Scotia (Nova Scotia) as well as on its north and south coast

- Kespukwitk (Gespugwitg) District

-

- Gespopoitnag / Gespogoitg tribal group

- lived in as Kespukwitk or Gespugwitg ("Land's End", roughly: "End of the World"), lived in the Annapolis Valley on the Bay of Fundy and on the Gulf of Maine in what is now Annapolis, Digby , Queens, Shelburne and Yarmouth counties in West and on the local coast of Nova Scotia (Nova Scotia) and along the Saint John River in the northeast of the bordering US state Maine , were referred to by the French as Souriquois ("salt water people, ie. Sea people")

-

After the decimation and expulsion of the Beothuk from Newfoundland by the better armed Mi'kmaq and the British, the Mi'kmaq added large parts of Newfoundland to their political and organizational system, which now included large parts of the former tribal area of the Beothuk, as the eighth and last district :

-

Taqamkuk / Ktaqmkuk district

-

- Tagamgoog / Taqamkuk tribal group

- took over large former tribal areas of the Beothuk on Newfoundland, which was now organized under the name Tagamkuk / Taqamkukewa'q / Ktagmkuk ("Land Across the Water") as the eighth and last district, lived along the Gander River and the bay of the same name and along the Exploits River , their newly acquired tribal area, also included the Bay of Islands and Port au Port Peninsula to the west

-

Sociopolitical Organization

Politically, the Mi'kmaq were a loose confederation of individual tribes made up of patrilineal clans and local groups. Most of the time, the members of a tribe were scattered across the district and only met during summer camps or during wartime. Until the young men were married, they were not allowed to keep their own dogs and had to hand over everything they had hunted to the Sagamore or the chief. If they left his group for a while, they would bring him gifts when they returned. Individual members or entire families could switch to another local group without any problems, albeit with a guilty conscience. The Sagamore had to acquire their authority through special skills. At the end of the 17th century, the French observed that chiefs assigned each family their hunting area and claimed a share of the proceeds from the skins. Through their knowledge of French, some Sagamore acted as intermediaries and thus gained advantages.

Culture

In Canada's maritime provinces, the Mi'kmaq were the dominant tribe, and it is believed that they immigrated from the north well before the 16th century. The climate barely allowed horticulture, and so they lived from hunting, fishing and collecting wild herbs and roots.

Livelihood

The traditional cycle began with the rivers freezing over. Typical for the winter were cold, ice and snow, as well as the retreat of the bears in hollow trees. During this time, the Mi'kmaq spread out into small hunting camps across the entire district and social relationships sank to a minimum. In the warmer months, the groups gathered and lived in villages. Maple syrup was harvested in the spring and some horticulture was occasionally done in the summer, but the main diet at that time was fish and seafood. The hunt for elk and deer began in autumn and when the first snow fell, the animals were easier to follow because the Mi'kmaq used snowshoes, sleds and toboggans . The word toboggan comes from the Mi'kmaq language.

According to the missionary Pierre Briard , each of the months was characterized by a predominantly occurring species of fish or game:

- The seal hunt was in January.

- In the month of February to mid-March there was the great hunt for beavers, otters, elk, bears and caribou.

- The fish started to spawn in mid-March.

- The herring came at the end of April; at the same time bustards (Canada geese), sturgeon and salmon came and then on the small islands the great search for eggs of the waterfowl followed.

- From the month of May to mid-September they were relieved of all food worries, because the cod appeared on the coast and also all sorts of fish and shellfish.

- The eels spawned in September.

- The hunt for elk and beaver began in October and November.

- In December, a fish they called Ponamo arrived that spawned under the ice.

Today the following month names are still known:

| month | Mi'kmaq name | designation |

|---|---|---|

| January | Punamujuiku's | Frostfish or Tomcod |

| February | Apuknajit | Snow blindness or bad eyes |

| March | Si'ko'ku's | spring |

| April | Penatmuiku's | Lay eggs |

| May | Tqlijuiku's | Young seals or herring fishing |

| June | Nipniku's | Summer or young foliage |

| July | Peskewiku's | Sea birds shed feathers |

| August | Kisaqewiku's | Young birds fledge |

| September | Wikumkewiku's | Moose rut |

| October | Wikewiku's | Fat tame animals |

| November | Keptkewiku's | All Saints Moon |

| December | Kesikewiku's | Chieftain's Moon (Christmas) |

The individual households were often larger than the nuclear families. In addition, the households were expanded through polygyny and the custom of bridal service , in which a young man came into the family for two or three years to work for his future father-in-law. Traditional stories often mention winter hunting groups in which two or more adult men participated, because some of the Mi'kmaq's hunting and fishing techniques required the cooperation of several men. Women sometimes transported the game over long distances to the camp. They could also be obliged to paddle the fishing canoes. To stalk large game on snowshoes with lances or arrows with stone points, one or more companions were necessary. This also applied to harpooning seals or tracking beavers in their burrows.

The Mi'kmaq were skilled canoe builders. The canoe was made of birch bark, was eight to ten feet long (2.45 - 3.05 m) and was also spacious enough that a single boat could house a full household of five or six people, with all their dogs, sacks, skins, Kettles and other heavy luggage. The Mi'kmaq even sailed the open sea in a canoe that could be equipped with a sail.

As with most of the tribes in the north-eastern woodlands, the Mi'kmaq culture changed more or less strongly after the arrival of the Europeans due to European influences, in particular the missionaries, the fur trade and the Franco-English conflict.

nutrition

In addition to fish and meat, the Mi'kmaq ate various kinds of wild roots, nuts and a number of berries, which were mashed and dried into round cakes. Most of their food, however, consisted of animal meat that was consumed fresh or smoked. The fat was carefully skimmed off from a hot broth or obtained by heating on a hollowed stone and then stored in birch bark containers or in animal gall bladders. Fish and eels were roasted on skewers. Meat was cooked by frying or boiling in large wooden tubs made from hollowed trunks of fallen trees.

They didn't know bread at all. If they accepted it from the French, they preferred to bake the bread in the hot sand under a fireplace. Popular objects of exchange for skins were metal tools and dried peas, beans, and plums.

Weapons, tools and hunting methods

The Mi'kmaq used spears, bows and arrows, traps and snares when hunting. Dogs helped track down game. Camouflage clothing was used to stalk moose, which were lured during the rutting season by the imitated call of a female animal.

Salmon hunted the Mi'kmaq with barbed spears. Other fish, such as cod, trout and smelt, were caught with fishhooks or nets made from bone. Another method of fishing was weirs, where the catch was evenly distributed among the builders of the weir.

Before contact with the Europeans, the material for tools consisted of wood, stone, bones or shells, materials that were soon largely replaced by metal, just as the bow and arrow were exchanged for the musket. The Mi'kmaq women used leather and birch bark to make buckets and pots, which were intricately sewn and decorated with porcupine bristles. They were also very skilled at weaving baskets from spruce roots.

Home decor

The Mi'kmaq's conical wigwam consisted of a wooden framework covered with birch bark, fur, woven mats, and evergreen branches. It could accommodate 10 to 12 people and was mainly inhabited in winter. For the summer there was an even larger wigwam for around 20 to 24 residents. In the middle was the fireplace with a smoke outlet above it, and equipment and accessories were stored on the outside of the walls. The ground was covered with twigs, over which furs were placed to sleep. The winter camps consisted of one or more wigwams that were set up in their own hunting grounds, usually near a reliable water source. If necessary, an overturned canoe with a small fire underneath served as a shelter for some hunters. French missionaries urged the Mi'kmaq to build chapels and churches, and to build houses that they could live in all year round. Nevertheless, many stuck to their nomadic life well into the 19th century.

Clothing and jewelry

Mi'kmaq men and women dressed similarly in fringed deerskin. Men wore loincloths under their outer clothing, while women tied their robes with two belts. Leggings and moccasins were made of elk or deerskin and had straps to tie with leather or tendons. Both sexes wore their hair long. There were two different types of snowshoes, one large and suitable for use on light, loose snow, while another smaller type was used on firm, hard snow. At the time of the first contact with Europeans, both sexes walked bareheaded, but a little later they took on hats made of fur and bark, by which one could recognize gender and rank. The traditional high and pointy hat for women made of dark blue, beaded and embroidered cloth came into fashion much later.

Life cycle

birth

The Mi'kmaq woman left the wigwam when her child was born and knelt, only supported by a few older women. The newborn was washed in cold running water, swallowed bear or seal fat, and tied to an ornate cradle board . The mother breastfed her child until the age of three, and the first solid food was pre-chewed by the parents. As long as the child was breastfed, the mother prevented or ended another pregnancy.

Childhood and youth

Children were brought up early on to treat their parents and elderly people with respect. They learned by imitating them, if they made mistakes they were admonished but never beaten, but received a lot of affection and love. With boys, for example, small ceremonies were held when the first tooth broke, he took his first step or killed his first small game. When he killed his first moose, he became a man. Little girls helped their mother with the household, building the wigwam, collecting the firewood, cooking and making the clothes.

Bridal service, wedding and marriage

If a young man wanted to get married, he had to do the bridal service in the wigwam of the future father-in-law . This lasted about two years, during which he had to work, hunt and prove his skills under the guidance of the older man. During this time, sexual relations with the fiancé were strictly forbidden. When the probationary period was over, he had to provide enough game for the wedding meal. On the wedding day, the shaman and elderly family members gave long speeches to the bride and groom, and the party ended with dances.

Arranged marriages , i.e. spouses determined by their families, were still common in the 19th century. The Catholic missionaries emphasize the virtue of the Mi'kmaq women at the time, but complain about the corruption caused by the liquor trade and the rather indifferent attitude of the Indians towards divorce. The birth of illegitimate children was seen not as a blemish, but rather as a sign of fertility. Most of the time, the local group took on responsibility for orphans. The chief placed her in the household of a good hunter. The second marriage of a man or woman was rarely celebrated with a public festival.

End of life and burial

The elderly were respected and their advice was sought in meetings. Some sources report caring care for elderly parents, but others suggest that elderly people were also abandoned to death if they could not go on their family's hikes. It is also known that when a person died there was little effort to keep them alive. Some old men enjoyed preparing their own funeral feast. When a shaman diagnosed an illness that was fatal, the sick person was given nothing to eat and cold water was poured on his navel to hasten his death.

If there was a death in the family, the mourners blackened their faces and the mourning lasted for three days. Messengers were sent out to notify relatives and friends in other villages. A feast was held on the third day of mourning. Then the funeral followed and each guest took part in the grave goods . There were funerals at the Mi'kmaq on uninhabited islands, where the body was wrapped in birch bark and buried in a sitting position with all weapons, dogs and personal effects. The mourners wore their hair cut short for a year, and widows were not allowed to remarry during this period. However, when the prescribed time passed, the mourners were encouraged to forget their grief.

Religion and mythology

The original ethnic religion , mythology and also the values of the Mi'kmaq were similar to the other Algonquian religions . Accordingly, their belief was animistic , they assumed that all natural things are animated and inhabited by spirits . The worshiped Creator God was Khimintu ( Kitchi Manitu ) - the world soul and sum of the all-encompassing, divine power Mintu . With Christianization, this power was assigned the role of the devil. The important, human-shaped cultural hero Gluskap experienced less change, although he was only the subject of mythology and was not worshiped religiously, even if he was considered the creator there .

The medicine men and women ( Puoin ), magicians and mediators to the “spirit world”, who healed diseases and were able to communicate with the spirits, played a central role in the preservation of religion .

Since the successful mission that began in the 17th century, Catholicism has completely replaced the old religion. However, it is flanked by some of the old myths and ideas that at least resonate under the guise of Christianity. According to the ongoing surveys by the evangelical-fundamentalist conversion network Joshua Project , around eight percent of the Micmac still profess an ethnic religion.

Taboos

The Mi'kmaq were not completely taboo , but they avoided the meat of certain animals, such as snakes, amphibians and skunks. There were menstrual taboos, so women were not allowed to step over the legs of hunters or their weapons. Hunted game was treated with respect; beaver bones, for example, were never given to dogs or thrown into the river. Killed bears were also treated with special respect. The Mi'kmaq believed that certain animals could transform into other species. It was said of ancient elks that they went into the sea and turned into whales.

Gluskap

Gluskap changed the landscape on his travels. He gave the animals their current shape, for example he gave the beaver his tail and the frog his voice. Gluskap was a powerful warrior who taught the Mi'kmaq important skills and foretold the future. He has gone, but he will return to assist the Mi'kmaq in their hour of need. Although he plays his main role in the legend as a magician and changer , he appears in some stories together with European or Christian narrative elements.

Kinap

Kinap had supernatural powers and did wonderfully powerful deeds to the great surprise of other tribes who had mocked him. The Kinap only used its power for good deeds, in the worst case for pranks.

Puwowin

More threatening was the Puwowin, a sorcerer who worked with magic spells or potions. The Puwowin was the legendary descendant of a 17th century medicine man named Bohinne . Even today, some Mi'kmaq believe in Puwowin. Like its old model, the modern Puwowin is able to predict the future, walk on the water and save individuals or entire settlements from evil events. There are still a lot of superstitions about the power of Puwowin. He can cause harm to a person remotely with an evil desire , for example an illness, an accident or even a major blow of fate. You can find European elements in most of the Puwowin stories, but these are always adapted from the Indian point of view.

Sketekemuc and others

The Mi'kmaq fear the Sketekemuc, a ghost-like being that heralds approaching death. The same category also includes the Mikemuwesu and the Pukeletemuc , dwarf-like creatures who dress and live like the Indians in ancient times , only eat meat from game and can either benefit or harm someone. Recently, they have taken on some traits of the French-Canadian lutins , playing pranks around the house or barn and riding horses that they leave behind with tightly braided mane and tails. In this case, the spirits are conjured up with holy water or palm fronds from Palm Sunday . Other mythological figures that still play a role are Kukwes , a giant cannibal, Wiklatmuj , little forest people and Jenu , northern ice giants.

Value system

The Mi'kmaq believed in a Great Spirit , a Creator who corresponded to the beliefs of many other Algonquin tribes. The French Jesuit missionaries used the Mi'kmaq name Mintu or Mntu to denote the devil (→ Mntu as devil among the Mi'kmaq ) , and chose the word Niskam for the Christian God , which means the greatest of all , Lord means. The Mi'kmaq, however, differed from the other Algonquin in their identification of the Creator with the sun. Several sources confirm this twice-daily sun worship , in which, for example, a large amount of collected furs was burned as an offering for the sun. It is hardly possible today to reconstruct the Mi'kmaq worldview in its entirety from historical sources, but there are some general guidelines that persist in the Mi'kmaq thought.

Mi'kmaq guidelines

- Life is everywhere - visible and invisible, under the ground and under the sea. Different forms of life can transform into others. Some species of animals and some people are not what they appear to be.

- The ancestors were great hunters - strong, dignified, and healthy. They were just, generous, and courageous. Their behavior should be a role model for their descendants.

- Indians have powers that are different from those of non-Indians. They can have supernatural helpers delivering messages or gifts to them. Some have Indian fortune or keskamitic , which enables them to do, find or carry out things quickly and with great reliability.

- People are the same - or should be. No one should put himself above the other, although the chiefs should be endowed with exceptional ability, generosity, courage, decency, and leadership.

- Restraint is usually better than excessiveness. Too much of anyone can be harmful; but everyone should occasionally break free and do unusual things.

However, these guidelines continue to play an important role for the Mi'kmaq in order to adapt to the changing conditions of the present.

history

16th Century

In addition to the Beothuk, the Mi'kmaq were probably the first indigenous people in North America to have contact with Europeans. The first account of them comes from John Cabot , who brought three Mi'kmaq to England in 1497. From 1501 the Mi'kmaq had regular contact with Spanish, French, British and Irish fishermen who visited the Canadian coast every summer. The fur trade began in 1519 and the Mi'kmaq showed great interest in various European goods, especially metal goods such as knives, axes and kettles.

When the French explorer Jacques Cartier anchored in Baie des Chaleurs in 1534 , his ship was surrounded by a large number of Mi'kmaq canoes whose occupants waved beaver pelts. By 1578, nearly 400 fishing boats were counted on Canada's east coast every summer. Although there were no European settlements at that time, the Mi'kmaq were afflicted by previously unknown diseases in 1564, 1570 and 1586. The first attempts at settlement by the Europeans failed due to famine and bitter cold. Meanwhile, the Mi'kmaq fur trade in France had created a new fashion. Anyone who had money bought a beaver hair hat and the new fashion quickly spread across Europe. The price of beaver pelts rose and French traders saw their opportunity for good business. The defeat of the Spanish Armada by the English fleet in 1588 was an important event because the Spaniards were no longer able to drive the other Europeans out of the New World .

17th and 18th centuries

In 1604, Samuel de Champlain built the first French settlement at the mouth of the St. Croix River . This began the French period in North America, which was to last from around 1600 to 1763. The Mi'kmaq culture was heavily influenced during the French period. The most significant changes arose from the fur trade and their involvement in the conflict between the French and the English.

In 1607 a war broke out between the Penobscot under their Sagamore Bashabes and the Mi'kmaq. Rivalry between the tribes for supremacy in the fur trade with the French in Port Royal had existed for a long time. The armed conflict, known as the Tarrantin War , lasted eight years and ended with the death of Bashabes in 1615. In the following years the Mi'kmaq were hit by a devastating epidemic, so that in 1620 only 4,000 of the formerly estimated 10,000 relatives survived. For 150 years the Mi'kmaq were embroiled in a series of wars between France and England, in which they always fought on France's side.

After the defeat of the French in the French and Indian War (1756–1763), the Mi'kmaq only had a short respite before the British colonists came. Not all Mi'kmaq made peace with the British in 1761, and there were repeated hostile clashes up to 1779. In the American War of Independence , the Mi'kmaq stood by the Americans in the hope that they would win and the French regained power Canada take over. After the war ended, English loyalists , whose life in New England had become unbearable, was granted land in Canada's maritime provinces. In 1783, 14,000 British loyalists left the young United States to settle in New Brunswick.

The British governors established Indian reservations . Chiefs continued to be elected for life, but the selection was influenced by the priests and confirmed by non-Indian officials. Land reserved for the benefit and good of a group of Indians was often later trimmed in favor of non-Indians who needed springs or water rights for commercial purposes. Much research remains to be done in the colonial and provincial archives of this period. The endeavors of the English colonists had only one aim - to control the fur trade, the monopoly of which the French had held for so long.

As the Indian land shrank and the number of fur-bearing animals decreased, the Mi'kmaq gradually became semi-settled; the women and children stayed in the settlements, while the men periodically worked outside or lived on the reservation, where they made baskets and wooden handicrafts and received social assistance from the colonial government. Some men continued to work as trappers, but most hired themselves out as loggers, hunting guides, and commercial fishermen, where they could at least use some of their traditional experience and skill.

19th century

In the middle of the 19th century, sailing ships, roads and sawmills were built in the Canadian maritime provinces. Many Mi'kmaq men also found work here, although they were often excluded from permanent jobs at sawmills and road construction. As semi-skilled workers, they worked in seasonal or periodic jobs that no one else would take for this wage, and gradually ended up in a rural proletariat . For several generations the Mi'kmaq hunted dolphins in the Straits of Canso and Fundy Bay . But when petroleum replaced dolphin oil for industrial needs, the hunt was over. The Indians participated as migrant workers in the commercial cultivation of potatoes in Maine and New Brunswick. Some worked in New England as workers in logging camps, house building or industry, but most returned regularly to the reservations because of unemployment.

20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, most of the Mi'kmaq were spread over about 60 reserves. Some hundreds and no more than a dozen Native American residents lived in others. The largest reserve was Restigouche , populated with 506 Indians according to the 1910 census. There was a Capuchin monastery here where Father Pacifique lived and worked, and the Mi'kmaq language could be learned in the convent school of the Sisters of the Holy Rosary .

Political, educational and economic changes began in the reservations around 1920. Gradually, the authorities introduced better medical care, which contributed to the rapid growth of the Mi'kmaq population, nearly doubling by 1970. From the end of the First World War until 1942 , the Indian agent in Restigouche was a doctor. The influence of the chiefs and councilors elected for two and three years under the provisions of the Federal Indian Act was small, so that most of the responsibility for the administration of the reservation lay with the Indian agents and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).

The newly opened schools on the reservations were visited only irregularly, but gradually boys and girls learned the basics of arithmetic and writing.

Many young Mi'kmaq experienced the First World War in the Canadian army and thus came into contact for the first time with Indians from other provinces of Canada. The war economy created jobs, and sport was also popular with young Mi'kmaq men. So were hockey and baseball is the national sport of the tribe. But the global economic crisis put an end to many hopes and led to high unemployment, especially among the Mi'kmaq, in the 1930s. Public money was needed to avert a famine.

The Second World War brought a short-lived prosperity and were offered the returning Mi'kmaq- veterans assistance to the construction or renovation of their homes. In the years that followed, in addition to electrification , radio and television also came to the reserves. To this end, public programs were launched to modernize the appearance of the reserves. New schools and transportation enabled the young Mi'kmaq to better prepare for college or work. Even so, the number of unemployed Indians increased and many Mi'kmaq were discriminated against so that they could only find work through government programs. It should come as no surprise that it increased the crime rate and alcoholism among Indians.

At the end of the 1940s, the Mi'kmaq were to leave the several dozen small reservations as part of a centralization program in order to move to larger settlements in Shubenacadie in central Nova Scotia and Eskasoni on Cape Breton Island . They were offered new homes and better education and earnings prospects. However, it quickly became apparent that there were hardly enough jobs in these regions. In 1951, a revised Indian law was passed, with which the tribal councils were expanded and could have more influence on their own affairs. This was part of a general policy designed to prepare the reservations for more self-determination.

Todays situation

In the 1960s, efforts to promote the Mi'kmaq through further training were finally successful. Many relatives found a new job that was well paid and in which they were also welcome. They worked building skyscrapers , just like the Mohawk did in the 1930s. By 1970 at least a third of all working men in Restigouche had worked building skyscrapers in Boston . This dangerous work at great heights was so popular with the Indians because it was compatible with their values and was well paid. Mi'kmaq women also learned new skills. The state-sponsored vocational training enabled many to qualify as nurses, teachers, secretaries or social workers. The Canadian government supported the Glooscap reserve (Nova Scotia) in 2009 with the equivalent of 680,000 euros.

In fact, today (2008) no Mi'kmaq reserve is characterized by special and visible prosperity, but this does not differ significantly from neighboring non-Indian communities of comparable size. The Indian houses look uniform and the small gardens are neglected. Many old huts have been left standing, and with the constant fluctuation of the population between the reserves and cities, there are many vacant apartments. Electricity is available on all major reservations, although some Indians hold onto their old kerosene lamp. Good roads are rare, the provincial government does not want to maintain them and the federal bureaucracy reacts very slowly to grievances.

This is what a typical Mi'kmaq reservation looks like today: a main road, a church, a school, a community center, an agency building or a tribal government office, a veterans hall, grocery stores, a water pipe and a canal system. In the reserves there are considerable differences among the inhabitants in terms of language, education and religiosity. Until the 20th century, the Mi'kmaq language was a mandatory mark of ethnic identity. But there are very few people who speak Micmac exclusively and the proportion of non-speakers is constantly growing. In some reserves, everyone under the age of 20 learns English as their first language. In Restigouche the tribal language is still the most important language for young people, but there too, television and English-speaking schools will soon limit the language skills of the young generation.

At the beginning of the 1960s, the federal government built schools on the reservations. In the reservation school in Restigouche, which was run by Catholic sisters and secular teachers, there were also classes for non-Indian children from neighboring communities, many of whom only spoke French. Most of the Mi'kmaq are still Roman Catholics and the major holidays are celebrated with appropriate ceremonies, especially the day of the patron saint, Saint Anne, on July 26th. But secularization and tourism influenced even this Micmac national holiday , and some of the young people are critical of the church today.

Political organization and representation of the Mi'kmaq in Canada and the USA

Mi'kmaq First Nations

Today (as of March 2013) there are several First Nations of the Mi'kmaq in Canada as well as a federally recognized tribe in the USA, which, taking into account the historical seven (later eight) districts, can be assigned to the following tribal groups :

Segepenegatig (District: Sipekne'katik, Sipeknékatikik - middle Nova Scotia )

- Millbrook First Nation , Wékopekwitk , We'kopekwitk or Wagobagitik - "End of the Water's Flow", corrupted by Acadians about Cobequid . It denotes the region around the eponymous Cobequid Bay and the administrative center, today's city of Truro , south of the Salmon River in Colchester County . Reserves: Millbrook # 27 (8 km east of Truro), Beaver Lake # 17 (78.4 km southeast of Kjipuktuk - "Great Harbor", i.e. Halifax , Sheet Harbor # 36 (91.2 km northeast of Halifax), Truro # 27A (bordering the southern city limits of Truro), Truro # 27B, Truro # 27C, Cole Harbor # 30 (9.6 km east of Halifax) The population is 1,345.

- Shubenacadie First Nation , formerly also known as L'nu Si'puk (Indian Brook First Nation) , Sipekníkatik or Sipeknékatikik - "wild potato area". Shubenacadie is the second largest First Nation in Nova Scotia and is located approximately 30 miles south of Truro with its administrative headquarters in Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia. Reservations: Shubenacadie # 13 (20 miles north of Halifax), Indian Brook # 14 (29 km southwest of Truro), Pennal # 19 (67 km northwest of Halifax), and New Ross # 20 (40 miles northwest of Halifax). The population is 2,502 people.

- Annapolis Valley First Nation . Kampalijek , the reservations of the First Nation are in the Annapolis Valley in the southwest of Nova Scotia, lived along the Annapolis River ( Taooopskik - "the river runs out between rocks"), first language is Canadian English , administrative seat: Cambridge Station, King's County, Nova Scotia, Reserves: Cambridge # 32 (88 km northwest of Halifax), St. Croix # 34 (46.4 km northwest of Halifax), more than half of the tribe members live outside the reservations, population: 270)

- Glooscap First Nation (named after the cultural hero Gluskap (Glooscap), Pesikitk - "place where meat is sliced and dried", until 2001 known as Horton First Nation , their reservation is in the Annapolis Valley , administrative headquarters: Hantsport, Nova Scotia, already opposite Land was allocated to them in 1800, and when the Annapolis Valley First Nation was also formed in 1880, there were 160 mi'kmaq in two settlements about 30 km away (one near Hantsport, the other near Berwick); soon, however, those felt close Hantsport (now Glooscap 1st Nation) disadvantaged, so that the two parishes separated in June 1984, and the Glooscap First Nation became the thirteenth Mi'kmaw Band in Nova Scotia, reservation: Glooscap # 35 (68.8 km northwest of Halifax) , Headquarters: Hantsport, Nova Scotia, Population (2008): 304)

Esgigeoag (also Esgigiag , district: Eskikewa'kik, Eskíkeawag, Esge'gewa'gi - East of Nova Scotia )

- Paqtnkek Mi'kmaw Nation ( Paq'tnkek or Paqtnkek - "by the bay", formerly also known as Afton Mi'kmaq First Nation , the First Nation is in Antigonish County 24 km east of Antigonish in northeast Nova Scotia, administrative seat: Afton Station, Antigonish County, Nova Scotia, Reserves: Pomquet - Paq'tnkek # 23 (15 miles east of Antigonish), Franklin Manor # 22 (20 miles southwest of Amherst), Summerside # 38 (11 miles east of Antigonish), population: 552)

Gespopoitnag (also Gespogoitg , District: Kespukwitk - west of Nova Scotia and parts of the bordering US state of Maine , were referred to by the French as Souriquois - "salt water men")

- Acadia First Nation ( Malikiaq , Administrative Headquarters : Yarmouth , Nova Scotia, Reserves: Gold River # 21 (60.8 km west of Halifax), Medway # 11 (108.8 km southwest of Halifax), Ponhook Lake # 10 (115.2 km west of Halifax) km southwest of Halifax), Wildcat # 12 (111 km southwest of Halifax), Yarmouth # 33 (3.2 km east of Yarmouth), 90% of the tribe live outside the reservations, population: 1,452)

- Aroostook Band of Micmacs ( Ulustuk , abbreviated from W'alustuk ( Welàstekw or Wolastoq - "beautiful or shiny river"), the Maliseet name for the Saint John River , which is why they were also called W'olastiquiyik ( Welastekwíyek - "Volk am beautiful (shiny) river ”), were officially recognized in November 1991 as the only group of Mi'kmaq at the federal level as a tribe by the USA ( Pastunkeywa'kik / Pastung or Bostoonkawaach / Bostoon , abolished from Boston ) (so-called federally recognized tribe ), most of the tribe members live in today's cities of Caribou , Houlton , Presque Isle and other communities in northeast Maine, because the tribe has widely scattered parcels of land, but does not have its own reservation, administrative headquarters: Presque Isle , Aroostook County , Maine, USA, population: approx. 1,100)

- Bear River First Nation ( L'setkuk , L'sitkuk , Ls'tgug , pronounced: 'elsetkook' - "flowing along by high rocks" or "water that cuts through" is the name for the Bear River (or Elsetkook ), earlier Also known as L'sitkuk band or sometimes as Muin Sipu , today increasingly also L'setkuk First Nation, it is located in the Annapolis Valley between the cities of Annapolis Royal and Digby. In earlier times, L'sitkuk was due to its strategic location - connected old water trade routes the Atlantic coast with the inland -, a central gathering and trading point for the Mi'kmaq, it was also an important meeting point of the Wabanaki Confederation , a political-cultural alliance between the Penobscot (Penawapskewi) , Passamaquoddy (Pestomuhkati) , Maliseet ( Wolastoqiyik) , Abenaki and Mi'kmaq, Reserves: Administrative Headquarters: Bear River, NS, Reserves: Bear River # 6 (17.6 km southeast of Digby), Bear River # 6A (9.6 km southeast of Annapolis Royal), Bear River # 6B (6.4 km southeast from Annapolis Royal), population: 322)

Piktuk aqq Epekwitk (also known as Epegwitg aq Pigtug )

-

Pigtogeog (also Pigtog , District: Piwktuk , Piktukewaq - Pictou County in northeastern Nova Scotia across from Prince Edward Island)

- Pictou Landing First Nation ( Puksaqtéknékatik , Puksaqte'kne'katik , live near Pictou ( Piktuk - "exploding gas"), on the south bank of the Northumberland Strait in Pictou County, Nova Scotia. Reservations: Fisher's Grant # 24 (9.6 km north of New Glasgow), Fisher's Grant # 24G (2 miles southeast of Pictou Landing), Boat Harbor # 37 (5 miles north of New Glasgow), Merigomish Harbor # 31 (8 miles east of New Glasgow), Franklin Manor # 22 (20 miles southeast of Amherst, sharing this with the Paqtnkek Mi'kmaw Nation), administrative seat: Trenton , Nova Scotia, population: 636)

-

Epegoitnag (also Epeggoitg , district: Epelwik, Epekwitk - Prince Edward Island )

- Lennox Island First Nation ( L'nui Mnikuk , reserve: Lennox Island (24 km north of Summerside , PEI), administrative headquarters: Lennox Island Island, PEI, population: 700 (of which approx. 437 in the reserve))

- Abegweit First Nation ( Epekwitk , Administrative Headquarters: Scotchfort, PEI, Reserves: Morell # 2 (38.4 km northeast of Charlottetown), Rocky Point # 3 (south of the Port of Charlottetown , PEI), Scotchfort # 4 (15 miles northeast of Charlottetown ), Population: 396)

Onamag (also Onamagig , district: Wunama'kik, Unamákik, Unamáki, Oonamaagik - Cape Breton Island )

- Waycobah First Nation ( Wékoqmáq , We'koqma'q - "head of the waters", the First Nation is located on Cape Breton Island , adjacent to the village of Whycocomagh, on the west bank of Bras d'Or Lake , Nova Scotia, administrative seat: Whycocomagh , Nova Scotia, Reserves: Whycocomagh # 2 (70.4 km west of Sydney ), We'koqma'q (20% of IR Malagawatch # 4, 62.4 km southwest of Sydney), population: 961)

- Wagmatcook First Nation ( Wagmitkuk , Waqam'tgug , Wagmatcook - "clean wave" or "where water flows clean", a reference to the Wagmatcook River (also known as the "Middle River") and the Bras D'Or Lake, the First Nation located about nine km southwest of Baddeck , which is on the west bank of Bras d'Or Lake, in the center of Cape Breton Island and is perhaps the oldest permanent Mi'kmaq settlement in Nova Scotia, administrative headquarters: Wagmatcook, NS, reservations: Wagmatcook # 1 (51.2 km west of Sydney), Margaree # 25 (68.8 km northwest of Sydney), Malagawatch # 4 (shared by 5 First Nations, therefore 20% each, 62.4 km southwest of Sydney) , Population: 782)

- Eskasoni First Nation ( Eskisoqnik or We'kwistoqnik - “where the fir trees are plentiful”, administrative seat: Eskasoni, Nova Scotia, the First Nation lies along the banks of the Bras d'Or Lake in the east of Cape Breton Island, Eskasoni First Nation represents the largest group of active Mi'kmaq speakers, reservations: Eskasoni # 3, Eskasoni # 3A (both 40 km southwest of Sydney), Malagawatch # 4 (20% of the reservation, 62.4 km southwest of Sydney), population: 4,163 )

- Membertou First Nation (named after the Grand Chief Maupeltuk (better known as Membertou , 1510–1611), the First Nation is only 3 km from the city center of the administrative center of Sydney, Nova Scotia, but within the city limits, so Membertou is a so-called . urban First nation community (urban First nation) until 1916, the reserve was (officially: Kings Road reserve) just off the Kings Road in Sydney harbor, administrative Office: Sydney, NS, reserves: Membertou # 28B (1,6 km south of Sydney), Caribou Marsh # 29 (8 km southwest of Sydney), Sydney # 28A (1.6 km northeast of Sydney), Malagawatch # 4 (20% of the reserve, 62.4 km southwest of Sydney), population: 1,373)

- Potlotek First Nation (formerly Chapel Island (= Potlotek) First Nation , also called Pastukopajitkewe'kati - "Sea Cow Place", another name of Potlotek (Chapel Island), their reservation borders on Pitu'pa'q ("Inneres Meer ", or Pitu'pok -" salt water ", the Bras D'Or Lake), Potlotek (Chapel Island) itself is approx. 270 m away from the settlement of the same name, on Chapel Island (also Mniku) was and is the Wed 'kmaq Grand Council (Great Council of the Mi'kmaq), in July / August the pilgrimage of St. Ann, the patroness of the Mi'kmaq, takes place on the otherwise uninhabited island, administrative seat: Chapel Island, Nova Scotia, reservations: Chapel Island # 5 (68.8 km southwest of Sydney), Malagawatch # 4 (20% of the reserve, 62.4 km southwest of Sydney), population: 691)

Sigenigteoag (also Sigenitog , district: Siknikt, Sikniktuk, Sikniktewag, Signigtewágig, Sgnuoptijg - in the catchment area of the Miramichi River and the Atlantic coast in New Brunswick )

- Esgenoôpetitj First Nation ( Eskinuopitijk , Eskɨnuopitijk , Esgenoopetitj , often still known under the former name Burnt Church First Nation , the name Burnt Church - "burned church" comes from the fact that during the wars between the British and the French , the Mi'kmaq numerous academics ( as the French called themselves) and the British then burned the church down as part of a campaign to destroy the settlements in 1758, administrative headquarters: Burnt Church, NB, reservations: Burnt Church # 14 (32 km northeast of Chatham , a district of Miramichi ), Tabusintac # 9 (40 km northeast of Chatham, NB), Pokemouche # 13 (64 km east of Bathurst (Nepisiguit) , at the mouth of the Nepisiguit River in the Chaleur Bay , population: 1,773)

- Elsipogtog First Nation ( Elsipogtog or L'sipuktuk - "River of Fire"), the area was also known as the "fortress of the Sikniktuk district" and the hunting and living area of the Mi'kmaq clan Alguimou (L'kimu), sometimes also as Mesgiig Oelnei , Meski'k Walney or Pekwotapaq , the different Mi'kmaq names for Big Cove, hence formerly called Big Cove Band , administrative headquarters: Elsipogtog First Nation (Big Cove), NB, reservations: Richibucto # 15 (8 km southwest from Rexton, NB, on the Richibucto River , formerly: "Big Cove Reserve", now mostly called "Elsipogtog" or "L'sipuktuk"), Soegao # 35 (5 km west of Moncton , NB) Population: 3,139)

- Buctouche First Nation (also Puktusk ili Tjipogtotjg , also Council of Buctouche Mi'kmaq Band , today's First Nation is located in Kent County in eastern New Brunswick, approx. 3.2 km southwest of its administrative seat Buctouche, NB, population (12/1999 ): 89)

- Eel Ground First Nation ( Natuaqanek , Natoageneg , Natuaqaneg , the reservations of the First Nation are along the Miramichi River in the north of New Brunswick in the direct vicinity of the city of Miramichi , administrative headquarters: Eel Ground, NB, reservations: Eel Ground # 2 (4.8 km west of Newcastle , NB), Big Hole Tract # 8 (20.8 km west of Newcastle NB), Renous # 12 (southern half of the reserve, 27.2 km west of Newcastle NB, population: 989)

- Fort Folly First Nation (until the mid-20th century they lived in Fort Folly IR # 27 (now: "Former Mi'kmaq Reserve at Beaumont" or "Former Fort Folly Reserve") on the east bank of the Petitcodiac River (called Petkootkweak ) near the The village of Beaumont, the area of the former reserve and the river basin of the Memramcook River was once an important settlement area of the Mi'kmaq and known as Kwesawék Amlamkuk - "the delta where the multicolored rivers meet", the First Nation now lives in a reserve that is approx .Located13 km west of Sackville , NB and approximately 40 km east of Moncton , NB, administrative headquarters: Dorchester , NB, reservation: Fort Folly # 1 (1.6 km southeast of Dorchester, NB), population: 124)

- Indian Island First Nation ( Lnui Menikuk or Elno Minigo , today's First Nation is in Kent County in eastern New Brunswick, reservation: Indian Island # 28 (8 km northeast of Rexton, NB), administrative seat: Indian Island, NB, population: 180)

- Metepenagiag Mi'kmaq Nation (until 2001 known as Red Bank First Nation , the reservations of the First Nation are located in the catchment area of the Miramichi River with the center Red Bank ( Metepnákiaq or Metepenagiag - "Where Spirits Live" called) at the mouth of the Little Southwest Miramichi River into the northwest Miramichi River , approximately 25 northwest of Miramichi, NB, Administrative Headquarters: Red Bank, NB, Reserves: Red Bank # 4 (14 miles west of Newcastle, NB), Red Bank # 7 (15 miles west of Newcastle, NB), Big Hole Tract # 8 (20.8 km west of Newcastle, NB), Point # 1 (the northern half of the reserve, 19.2 km west of Newcastle, NB), population: 650)

Gespegeoag (also Gespegiag , district: Gepeg, Kespek - "last land", Kespékewaq , Kespoogwitunak , Gespe'gewa'gi - "last acquired land", i.e. the Gaspésie and westwards along the St. Lawrence River ( called Maqtugweg ) a wide one Network of waterways inland from Québec , in the east to Chaleur Bay (called Mawi Poqtapeg , occasionally hunted on Natigasteg - "foreground", "prominent position" ( Anticosti Island ) and in the south to the Miramichi River in New Brunswick )

- Gesgapegiag First Nation (also Micmacs of Gesgapegiag , the First Nation is located approx. 56 km east of Restigouche, Québec, between the First Nations of Listuguj and Gespeg, on the Rivière Cascapédia , the current settlement was officially built in 1850, but the Mi ' kmaq had lived along the Rivière Cascapédia for centuries and the area around the present settlement Gesgapegiag was a very important part of the traditional tribal area of the district of Gespe'gewa'gi, this group named itself after the Rivière Cascapédia as Keskapekiaq , Gesgapegiag - "da where the river widens "," mighty stream "," great river ", administrative seat: Maria (also: Gesgapegiag) , Québec, population: 1,417)

- La Nation Micmac de Gespeg (also Première Nation de Gespeg or Micmac Nation of Gespeg , the First Nation is a so-called landless First Nation , therefore around three fifths of the relatives live in the town of Gespeg on the south coast of the Gaspé Bay, two fifths in Montréal , once their tribal territory stretched from Gaspé Bay to York and Dartmouth , they also roamed to the north of the Gaspé Peninsula, including the area around the present-day city of Percé , administrative center: Fontenelle, Québec, population: 656)

- Listuguj Mi'gmag Government (also Listuguj Mi'gmaq First Nation or Première Nation de Listuguj , often just Listukuj Míkmaq , call themselves Gespe'gewaq - "The People of the Last Land", the Listuguj settlement(English pronunciation: ' lis tu guch ') surrounded by the mountains of the Appalachians lies in the southwest of the Gaspésie in Québec, in the south it isborderedby the Restigouche River , which also forms the border with the province of New Brunswick, until 1745 their settlement, thencalled Tigog , was located , on the south bank of the Restigouche at Sugarloaf Mountain, on the site of today's Atholville, New Brunswick, their former tribal area comprised the large catchment area and the tidal delta of the Restigouche up to the Chaleur Bay (Mawi Poqtapeg) , they called the river 'Listuguj' - "Divides the country like the five fingers in a hand" (meaning the Restigouche and its five tributaries near the mouth: the Kedgwick River, Matapédia, Patapédia and the Upsalquitch), hence they were formerly known as Restigouche River Micmac or Mickmakis de rivière Ristigouche , language: Listugujewa'tuet dialect of Mi'gmaw, Canadian English and Canadian French, administrative headquarters: Listuguj, Québec, population: 3,690, of which approx. 1,610 live outside the reserve)

- Eel River Bar First Nation ( Oqpíkanjik , Ugpi'ganjig , also Council of Eel River Bar , administrative headquarters: Eel River Bar, NB, reservations: Eel River # 3 (3.2 km south of Dalhousie, NB), Moose Meadows # 4 ( 20 miles south of Dalhousie, NB), Indian Ranch (1.5 miles south of Dalhousie, NB), population: 690)

- Pabineau First Nation (also: Première Nation de Pabineau , call themselves Oinpegitjoig L'Noeigati , also known as Kékwapskuk or Ge'goapsgog , the Pabineau reserve # 11 is 8 km south of Bathurst) , NB, population: 286)

Tagamgoog (also Taqamkukewa'q , district: Taqamkuk , Ktaqamkuk - "Land Across the Water" - southern Newfoundland )

- Miawpukek First Nation ( Miawpukek Mi'kamawey Mawi'omi , Miawpukwek - "Middle River", also known as Mi'kmaq of Taqmkuk ( Newfoundland ) , formerly known as Conne River Micmac , said they were close to the Pi'tow'ke or Pi'tawkewaq ("upriver", from the Mi'kmaq: Pi'tow'ke waq na nin - "We come from the country upriver", Beothuk ) related, in addition to Beothuk they also have Innu , Abenaki and Europeans (probably Acadians ) as ancestors, lived and live along the south coast of Newfoundland, administrative seat: Conne River, NL, reservation: Samiajij Miawpukek (Conne River), approx. 224 km south of Gander, 16.66 km², population: 2,928)

-

Qalipu Mi'kmaq First Nation ( Qalipu - " caribou ", pronounced: 'hal-lay-boo', often also called Qalipu Mi'kmaq First Nation Band (QMFNB) , as the First Nation consists of nine bands (or First Nations) , each of which represents a ward (district / administrative seat of the respective band) for the election of the band council (tribal council) , administrative seat: Corner Brook, NL, population: 23,853)

- Elmastogoeg First Nations (until 2003 Benoit First Nation ( Penwa 'Mawi-Amskwesewey L'nue'kati ) or Benoits Cove First Nations , until 1980 part of the St. George Indian Band, the communities of the First Nation are located in the southwest of Port au Port Peninsula (Payun Aqq Payunji'j), NL, its name is derived from Elmastukwek , the name of the Bay of Islands , administrative seat (district): Degrau, NL)

- Corner Brook Indian Band (Administrative Headquarters (borough): Corner Brook, NL)

- Flat Bay Mi'kmaq Band (formerly called Flat Bay Indian Band , administrative seat (district): Flat Bay, NL)

- Gander Bay Indian Band (lived and live on Gander Bay and along the Gander River ( called Akilasiye'wa'kik ) and Gander Lake (called Akiilasiye'wa'kik Qospem ) in the middle of Newfoundland, administrative seat (district): Gander Bay , NL, Population (2009): 315 (of which 150 outside the settlement))

- Glenwood Mi'kmaq First Nations (the town of Glenwood on the Gander River ( Akilasiye'wa'kik called) is about 24 km west of Gander in northeast Newfoundland , hunted along the Gander River and on Gander Lake ( Akiilasiye'wa'kik Qospem called), as well as between Glenwood and Gander Bay via the system of rivers of the Miawpukek Reserve in Conne River. lives in the middle of Newfoundland, administrative seat (district): Glenwood, NL)

- Port au Port Indian Band ( Pukt aq Pukt Kwe'sawe'k or PoPayun Aqq Payunji'j Mi'kmaq - "Inhabitants of the Port au Port Peninsula ( Payun Aqq Payunji'j called)", now live on the west coast of Newfoundland, administrative center (District): Port au Port, NL)

- Sple'tk First Nation (SFN) (formerly Exploits Indian Band ) made their living from elk and caribou hunting and fishing - especially salmon - along the Exploits River and on Red Indian Lake (named after the Red Indians who previously settled here Beothuk ) in Newfoundland, administrative seat (district): Grand Falls-Windsor , NL, population: 1,600)

- St. George's Indian Band (lived in the Codroy River Valley ( Miawpukwek - "Middle River"), along the St. George's River (called Nujio'qon (i) ik ) and around the Bay St. George between the Bay of Islands and Port aux Basques ( called Siinalk ) on the southwest coast of Newfoundland , called themselves Noywa'mkisk after the Bay of St. George , but mostly today Nujio'qonik - "where the sand is blown up by the wind", administrative seat (district) : St. George's (Nujio'qon), NL, population: approx. 2,200)

- Indian Head First Nations ( Ilnu Wunji Mi'kamawey Mawi'omi , formerly: Stephenville / Stephenville Crossing Band , administrative seat (district): Stephenville Crossing, NL)

Tribal Councils of the Mi'kmaq

Confederacy of Mainland Mi'kmaq (CMM)

- Annapolis Valley First Nation

- Bear River First Nation

- Glooscap First Nation

- Millbrook First Nation

- Pictou Landing First Nation

- Paqtnkek Mi'kmaw Nation

Mawiw Council

- Esgenoôpetitj First Nation (also: Burnt Church First Nation)

- Elsipogtog First Nation

Mi'gmawei Mawiomi Secretariat (MMS)

- Gesgapegiag First Nation

- La Nation Micmac de Gespeg

- Listuguj Mi'gmag Government - also member of the Gespe'gewaq Mi'gmaq Resource Council (GMRC)

Mi'kmaq Confederacy of PEI

- Lennox Island First Nation

- Far away First Nation

North Shore Micmac District Council and Union of New Brunswick Indians

- Buctouche First Nation

- Eel Ground First Nation

- Fort Folly First Nation

- Indian Island First Nation

- Metepenagiag Mi'kmaq Nation

- Eel River Bar First Nation - also member of the Gespe'gewaq Mi'gmaq Resource Council (GMRC)

- Pabineau First Nation - also member of the Gespe'gewaq Mi'gmaq Resource Council (GMRC)

Union of Nova Scotia Indians (UNSI)

- Acadia First Nation

- Shubenacadie First Nation

- Waycobah First Nation

- Wagmatcook First Nation

- Eskasoni First Nation

- Membertou First Nation

- Potlotek First Nation

Independent First Nations

- Miawpukek First Nation

- Qalipu Mi'kmaq First Nation

- Aroostook Band of Micmacs

Demographics

In 1616 , Father Biard estimated the Mi'kmaq population to be over 4,000. But he noted elsewhere that there would have been a great loss in the 16th century. Fishermen had infected the Mi'kmaq with European diseases to which they could not resist. By pleurisy , tonsillitis and watch about three-quarters of the Mi'kmaq were exterminated. Smallpox , wars and alcoholism led to a further decline in the Indian population, which presumably reached its lowest level in the mid-17th century. There was a slight recovery during the 19th century and the population appears to have remained almost stable. There was a noticeable increase in the 20th century. The average growth from 1965 to 1970 was around 2.5% annually. Today (as of March 2013) there are again over 57,000 Mi'kmaq officially recognized by the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development in Canada as Status Indians (according to the Indian Act ) and more than 1,100 officially recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the USA as Indians recognized Mi'kmaq. However, there are also several thousand Non Status Indians with Mi'kmaq ancestors who have not officially registered with the recognized First Nations , have lost their legal title as Status Indians or officially as Métis or even as descendants of the Acadians , French settlers, apply, as they usually no longer speak their tribal language, but Acadian French .

| year | population | proof |

|---|---|---|

| 1500 | 10,000 | estimate |

| 1600 | 4,000 | estimate |

| 1700 | 2,000 | estimate |

| 1750 | 3,000 | estimate |

| 1800 | 3,100 | estimate |

| 1900 | 4,000 | count |

| 1940 | 5,000 | count |

| 1960 | 6,000 | count |

| 1972 | 9,800 | count |

| 2000 | 20,000 | estimate |

reception

The French television series The Adventures of a Lady (Les Aventuriers du Nouveau-Monde) was mainly about the fact that a negotiator should win the Mi'kmaq as an ally of the British during the Seven Years' War. The series aired in 1987.

In the novel Pet Sematary by Stephen King a burial place of the Mi'kmaq in the northeastern United States plays a central role and the Mi'kmaq are mentioned in the book.

In the novel, from hard wood from Annie Proulx history also plays a central role in a Mi'kmaq family and their life in the midst of colonization.

See also

- First Nations

- First Nations history

- List of North American Indian tribes

- Rita Joe and Gail Tremblay (two modern Mi'kmaq writers)

literature

- Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians . Vol. 15. Northeast. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC 1978, ISBN 0-16-004575-4 .

- Harald EL Prins: The Mi'kmaq: Resistance, Accommodation, and Cultural Survival (Case Studies in Cultural Anthropology). Thomson Learning, 1996, ISBN 0-03-053427-5 .

- Stephen A. Davis: Mi'kmaq: Peoples of the Maritimes. Nimbus Publishing (CN), 1998, ISBN 1-55109-180-1 .

- Daniel N. Paul: We Were Not the Savages: A Mi'kmaq Perspective on the Collision Between European and Native American Civilizations. Fernwood Pub., 2000, ISBN 1-55266-039-7 .

- William C. Wicken: Mi'kmaq Treaties on Trial: History, Land, and Donald Marshall Junior. University of Toronto Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8020-7665-3 .

- Ruth Holmes Whitehead: The Old Man Told Us: Excerpts from Mi'kmaq History 1500-1950. Nimbus Pub, 2004, ISBN 0-921054-83-1 .

- Rita Joe , Lesley Choyce: The Mi'kmaq Anthology. Nimbus Publishing (CN), 2005, ISBN 1-895900-04-2 .

Web links

- Micmac History

- Mi'kmaq ( English, French ) In: The Canadian Encyclopedia .

- Nova Scotia Museum

- Mi'kmaq Dictionary Online

- Mi'kmaq, Website Mi'kmaq and Maliseet Cultural Objects

- Mi'kmaw Pronunciations for Teaching About the Mi'kmaq , Pronunciation

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ethnologue - Micmac

- ^ Anne-Christine Hornborg: Mi'kmaq Landscapes. From Animism to Sacred Ecology. (= Vitality of Indigenous Religions Series). Ashgate Publishing, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7546-6371-3 , p. 3.

- ↑ Emmanuel N. Metallic: The Metallic Mìgmaq-English Reference Dictionary. Pu Laval, 2005, ISBN 2-7637-8015-6 .

- ^ Daniel N. Paul: We Were Not the Savages. Collision Between European and Native American Civilizations. 3. Edition. Fernwood Pub, 2007, ISBN 978-1-55266-209-0 , p. 10.

- ^ Spelling of Mi'kmaq , Nova Scotia Museum website

- ↑ The Mi'kmaw Resource Guide. Retrieved August 21, 2019 .

- ^ The Nova Scotia Museum's Míkmaq Portraits database

- ↑ https://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/blackbird-cover-101.html

- ↑ https://atlantic.ctvnews.ca/it-s-really-cool-paul-mccartney-praises-mi-kmaw-teen-s-blackbird-cover-1.4449170

- ↑ Christian F. Feest (ed.): Cultures of the North American Indians. Könemann, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-8290-0500-8 , pp. 144-145.

- ↑ a b Christian F. Feest: Animated Worlds - The Religions of the Indians of North America. (= Small Library of Religions. Volume 9). Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 1998, ISBN 3-451-23849-7 , pp. 192–193.

- ↑ search.library.wisc.edu

- ↑ a b c d e f g Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians . Vol. 15: Northeast. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC 1978, ISBN 0-16-004575-4 , Chapter: Micmac, pp. 109ff.

- ↑ When the French arrived (late 16th century), the Mi'kmaq began to expand westward along the Gaspésie Peninsula and the St. Lawrence River to the tribal areas of the Mohawk , hence they called the conquered peninsula Kespek or Gespe'gewa 'gi ("last purchased land")

- ↑ a b Micmac - Religion and Expressive Culture . In: everyculture.com, accessed December 25, 2015.

- ↑ [https://legacy.joshuaproject.net/people-profile.php?peo3=13708&rog3=CA] for Canada and [https://legacy.joshuaproject.net/people-profile.php?peo3=13708&rog3=US] for the United States, accessed August 23, 2019.

- ↑ a b Dickshovel.com

- ↑ Big earners in the reservation

- ^ Homepage of the Millbrook First Nation

- ^ Homepage of the Shubenacadie First Nation

- ↑ homepage Annapalis Valley First Nation

- ^ Homepage of the Glooscap First Nation

- ^ Homepage of the Horton First Nation (now: Glooscap First Nation) ( Memento from August 27, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ homepage Paqtnkek Mi'kmaw Nation

- ^ Homepage of the Afton Mi'kmaq First Nation (now: Paqtnkek Mi'kmaw Nation) ( Memento from March 25, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Homepage of the Acadia First Nation

- ↑ Homepage of the Aroostook Band of Micmacs

- ↑ Homepage of the Bear River First Nation (also L'setkuk or Muin Sipu) ( Memento from October 15, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Micmac Dictionary

- ↑ Mi'kmaq Place Names ( Memento from May 10, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 180 kB)

- ^ Homepage of the Pictou Landing First Nation

- ^ Homepage of the Lennox Island Nation

- ^ Homepage of the Abegweit First Nation

- ↑ Unama'ki - First Nation Communities

- ↑ Homepage of the Waycobah First Nation ( Memento from January 15, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ website of the Wagmatcook First Nation

- ↑ website of the Eskasoni First Nation

- ^ Homepage of the Membertou First Nation

- ↑ homepage Potlotek First Nation

- ↑ homepage Esgenoôpetitj First Nation (Burnt Church First Nation ( Memento of 13 May 2014 Internet Archive )

- ↑ website of the Elsipogtog First Nation (formerly Big Cove Band) ( Memento of 9 June 2012 at the Internet Archive )

- ^ Homepage of the Eel Ground School

- ↑ Homepage of the Fort Folly First Nation ( Memento from January 1, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Canada's historic Places - Former Mi'kmaq Reserve at Beaumont (Former Fort Folly Reserve)

- ^ Homepage of the Indian Island First Nation

- ↑ website of Metepenagiag First Nation ( Memento of 17 April 2013, Internet Archive )

- ↑ When the French arrived (late 16th century), the Mi'kmaq began to expand westward along the Gaspé Peninsula and the St. Lawrence River to the tribal areas of the Mohawk , hence they called the conquered peninsula Kespek or Gespe'gewa 'gi ("last purchased land")

- ^ Relationship to our Territory ( Memento from April 16, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Speaking About Our Land - Gesgapegiag

- ↑ Homepage of the Nation de Gespeg (also Micmac Nation of Gespeq)

- ↑ Speaking About Our Land - Gespeg

- ↑ homepage of Listuguj Mi'gmag Government

- ↑ Speaking About Our Land - Listuguj

- ↑ homepage Pabineau First Nation

- ↑ Homepage of the Miawpukek First Nation (Miawpukek Mi'kamawey Mawi'omi)

- ^ Rita Joe: Song of Rita Joe. University of Nebraska Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8032-7594-3 , Autobiography of a Mi'kmaq Poet, p. 130.

- ↑ Homepage of the Qalipu Mi'kmaq First Nation (also: Qalipu Mi'kmaq First Nation Band (QMFNB))

- ^ Government of Canada Announces the Creation of the Qalipu Mi'kmaq First Nation Band. ( Memento from July 26, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) by Reuters

- ^ Homepage of the Benoit First Nation (now: Elmastogoeg First Nation), a band of the Qalipu Mi'kmaq First Nation

- ↑ MI'KMA'KI PLACENAMES

- ↑ Homepage of the Flat Bay Mi'kmaq Band, a band of the Qalipu Mi'kmaq First Nation ( Memento from December 17, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Homepage of the Glenwood Mi'kmaq First Nations, a band of the Qalipu Mi'kmaq First Nation ( Memento from July 19, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Homepage of the Sple'tk First Nation (SFN), a band of the Qalipu Mi'kmaq First Nation ( Memento from March 8, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Homepage of St. George's Indian Band, a band of the Qalipu Mi'kmaq First Nation

- ↑ as "Middle River" the Mi'kmaq refer to several rivers depending on the dialect: the Wagmatook River as well as the Codroy River and Conne River

- ↑ N0YWAMKISK (Where The Sand Blows) - Bay St. George Regional Indian Band Council

- ↑ Information on the Indian Head First Nations, a band of the Qalipu Mi'kmaq First Nation

- ↑ Website of the Confederacy of Mainland Mi'kmaq (CMM)

- ↑ the Mawiw Council website ( Memento of 17 May 2014 for Internet Archive )

- ↑ Website of the Mi'gmawei Mawiomi Secretariat (MMS)

- ↑ Website of the Gespe'gewaq Mi'gmaq Resource Council (GMRC)

- ^ Website of the Mi'kmaq Confederacy of PEI

- ↑ North Shore Micmac District Council website

- ^ Website of the Union of New Brunswick Indians ( Memento from May 3, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- ^ Website of the Union of Nova Scotia Indians (UNSI)