Glienicke Castle

Glienicke Palace was the summer palace of Prince Carl of Prussia . It is located in the southwest of Berlin, on the border of Potsdam near the Glienicke Bridge in the district Wannsee of Steglitz-Zehlendorf . Administered by the Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg , the castle in the middle of the landscaped park Kleinglienicke central part of a group of buildings of architectural, artistic and cultural historically significant buildings from the first half of the 19th century, since 1990 as a World Heritage Site under the Protection of UNESCO stand.

The current classicist shape of the former manor house from 1753, with the claim of an Italian villa, goes back to conversions and extensions carried out by the architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel in 1825. After Prince Carl's death in 1883, the building became increasingly neglected. During the Second World War it was used by others as a military hospital and, after the war, briefly as an officers' mess for the Red Army . From the 1950s the castle and the adjoining outbuildings housed a sports hotel and from 1976 a folk high school. The castle has been used as a museum since the late 1980s, exhibiting Schinkel furniture and art objects, most of which came from the possession of Prince Carl. In April 2006, the first court gardening museum in Europe opened in the west wing, showing the history of the Prussian court gardeners.

history

Hofrat Mirow bought the Glienicker site

The foundation stone for the Glienicke Palace, which was redesigned in classical forms by Karl Friedrich Schinkel, was laid by the Berlin doctor and councilor Johann Jakob Mirow (1700–1776) in the middle of the 18th century. In 1747, the head of a military hospital set up in the former electoral hunting lodge Glienicke acquired an area further north of the hunting lodge, the core of today's area, and had a brick factory built there in 1751 and a manor house built there in 1753, which is already referred to as a castle in documents of the time.

After the Councilor got into financial difficulties, the property was auctioned in 1764, which Major General Wichard von Möllendorff acquired for 6,070 Reichstaler . In the course of the following decades, the estate changed hands several times in 1771, 1773 and 1782, until it was acquired in 1796 by Oberstallmeister Carl Heinrich August Graf von Lindenau, who came from Saxony and had been in Prussian service since 1786, for 23,000 Reichstaler.

Embellishment of the estate by Count Lindenau

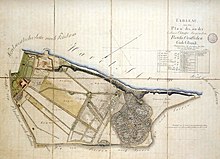

Through redesigns that dragged on until 1806, Lindenau gave the entire Glienicke property a new look, as a result of which the manor house was given a different meaning. Lindenau redesigned the area previously used and built on from a purely economic point of view by designing individual parts of the area between agricultural areas. They are shown on a plan drawing from 1805 as "English Parthia". For the first time, buildings serving aesthetics and luxury were built, such as an orangery on the site of today's Stibadium and a tea pavilion to the west, the so-called "Little Curiosity", both south of the manor house on Chaussee Berlin-Potsdam, today's Königstrasse . The horticultural and architectural decoration around the manor house upgraded the building to a stately country residence. The estate, which has now been transformed into an " ornamental farm ", also known as "ferme ornée", was used by the owner both economically and for recreation in the country.

After the defeat of Prussia by the Napoleonic army near Jena and Auerstedt in 1806, Count Lindenau got into financial difficulties. In addition to the contribution payments to France, which had to be raised by citizens and nobles alike, and the economic stagnation of Prussia, Lindenau also suffered financial losses when trying to develop the Büssow estate in Neumark, which he had acquired in 1803, into a model economy. After his release from royal service in 1807 he tried to sell the Glienicke estate, which was unsuccessful in the generally difficult situation in Prussia. An offer to sell Lindenau to Karl August Graf von Hardenberg also failed in October 1810 because the Prussian state chancellor lacked the financial means to buy it. However, he lived in the country house as a tenant in 1811 and 1812 for 400 Reichstaler a year until the merchant Rudolph Rosentreter bought it on November 18, 1812 for 20,000 Reichstaler. Rosentreter, who probably got rich through collaboration with the French army, had numerous new plantings on the site and conversions carried out on the country house, which he commissioned Karl Friedrich Schinkel to carry out. Hardenberg showed renewed interest in Glienicke during the construction work.

A country estate for Prince Hardenberg

Hardenberg had earned a great reputation for his services to the reorganization of Prussia. After the victory over Napoleon , Friedrich Wilhelm III raised him . on June 3, 1814 to the prince's rank. The State Chancellor was now in a position to acquire the Glienicke estate, which was conveniently located between the residences in Berlin and Potsdam. The ownership took place on September 22nd, 1814 for a purchase price of 25,900 Reichstalers.

In addition to renovation work on the inside and outside of the manor, Prince Hardenberg had the surrounding area of the country house redesigned from the autumn of 1816. The order was Peter Joseph Lenne , who was at that time the garden journeyman. From an "English garden party" with fruit terraces between the Landhaus, Havel and today's Königstrasse, he designed a pleasure ground , a decorative garden that was considered an "extended apartment" in the garden architecture theory of Prince Hermann von Pückler-Muskau . Further landscaping designs for the entire property were carried out by Lenné in the years that followed.

After the unexpected death of Prince Hardenberg on November 26, 1822, his son Christian Graf von Hardenberg-Reventlow and his daughter Lucie Countess von Pückler-Muskau put Glienicke up for sale. Despite numerous interested parties, the heirs waited two years until they found a suitable buyer in Prince Carl of Prussia, who knew how to appreciate the work that his father had begun and who had the financial means to continue the Glienicker estate. The property finally changed hands for 50,000 Reichstaler. After contract negotiations on March 23, 1824, the transfer of ownership took place on May 1 of that year.

Prince Carl fulfills his "dream of Italy"

With the purchase of the Glienicke estate, Prince Carl was the first son of the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III., Who owned his own property. He was followed by his older brothers Friedrich Wilhelm in 1826 with the palace and park part Charlottenhof and Wilhelm in 1833 with the Babelsberg park and in 1835 with the construction of the palace of the same name . Like Friedrich Wilhelm, Carl also showed great interest in ancient culture . This “passion for antiquity and other antiquities” aroused and encouraged the tutors of Prince Heinrich Count Menu von Minutoli as a child . The first trip to Italy in 1822 was all the more impressive for Prince Carl, when he was enthusiastic about the harmony between landscape, architecture and antiquity. When he returned with these impressions, he made the decision to realize this “dream of Italy” in his native Berlin. Carl's artistically gifted brother Friedrich Wilhelm supported the project with sketches for the design of individual buildings. The architects Karl Friedrich Schinkel and his pupil and colleague Ludwig Persius adopted some details of these proposals for their own designs. In close cooperation with the garden architect Peter Joseph Lenné, a unique, southern-looking architectural and garden landscape was created, which Prince Carl decorated with antiques from his rich collection.

With the death of Prince Carl on January 21, 1883 the heyday of the Glienicker plant ended. In his will he decreed that his son and main heir Friedrich Karl had to spend at least 30,000 marks a year on maintaining the Glienicke buildings and parks. However, this decree did not come into effect for long, as Prince Friedrich Karl died on June 15, 1885 at the age of 57 and thus only survived his father by two years. The property now passed to his only son, Friedrich Leopold , who showed little interest in the Schinkelschloss. After his marriage to Louise Sophie of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg , a sister of Empress Auguste Viktoria , he moved into the Glienicke hunting lodge , which belonged to the property, and lived there until the end of the monarchy. As a result of structural neglect, Glienicke Castle began to fall into disrepair, and as a result of the sale of antique and medieval collectibles in the 1920s, much of what Prince Carl had collected over decades was scattered around the world.

Increasing neglect and transition to state ownership

After the First World War and the end of the monarchy, Friedrich Leopold moved his residence to Lugano in 1918 , where he took numerous works of art and furniture with him. The Glienicke property, including the buildings, was initially confiscated by the new government. Against the background of the failed prince expropriation , however, it was returned to Friedrich Leopold on October 26, 1926 after the ratification of the law on the property dispute between the Prussian state and the members of the formerly ruling Prussian royal house . Just two years later, the prince tried to sell parts of the Glienicke area to a real estate company. This initially failed due to a temporary injunction on July 17, 1929 from the Prussian State, which wanted to keep the site as a park. According to the agreements in the property dispute, the state was defeated in these proceedings. The now neglected summer palace was not affected by renewed plans to sell, but parts of the inventory that were auctioned off together with items from the hunting lodge in 1930 or early 1931.

On September 13, 1931, Prince Friedrich Leopold died on his Krojanke estate in the West Prussian district of Flatow . To pay off his debts, there was a second auction of Glienicke art objects from Lugano in November 1931. The 12-year-old grandson Prince Friedrich Karl took over the inheritance . The older sons of Friedrich Leopold, Friedrich Sigismund (1891–1927) and Friedrich Karl had died before him and the third son, Friedrich Leopold jun. (1895–1959) excluded from inheritance. However, he got the right to live in Glienicke and presumably property rights to the movable inventory. With his boyfriend since his youth, Friedrich Münchgesang alias Friedrich Baron Cerrini de Montevarchi, he lived in the cavalier wing of the palace complex until they moved to the Imlau estate near Werfen in the Salzburger Land after the palace was sold in 1939 . As had already begun in Glienicke, they also sold art objects from there, some of which came from Prince Carl's time.

During the lifetime of Friedrich Leopold sen. The Dresdner Bank received a large part of the Glienicker park area as security after taking out large loans from the heavily indebted prince. In a share swap between the bank and the city of Berlin, this parking area came into the possession of the capital with an entry in the land register on April 29, 1935. The heavily neglected summer palace and the immediate vicinity, including the hunting lodge with the hunting lodge park, initially remained the property of Friedrich Karls junior. At the end of 1937 negotiations took place between the two parties about the necessary repairs to the summer palace, but these failed due to differences of opinion about the scope of the work. The 20-year-old prince initially turned down a subsequent purchase offer from the city, whereupon he was advised to either accept the offer or be expropriated. The remaining part of the park became the property of the City of Berlin on July 1, 1939. This was now the sole owner of the entire Glienicke area including all buildings. An action for damages filed by the Prince in 1986 because of the forced sale by the National Socialists fell in favor of the State of Berlin on October 14, 1987, as was the judgment in the appeal process of April 20, 1989.

At the beginning of 1940 the architect Dietrich Müller-Stüler , a great-grandson of Friedrich August Stuler , was commissioned to create office space for the Berlin city president and mayor Julius Lippert . Lippert had been using the Jägerhof, located at the northern tip of the area, as a country estate since 1935 and was interested in the purchase of the palace by the city of Berlin since 1935, especially since plans had included Königstrasse, only a few meters away - at that time Reichsstrasse No. 1 called - to be widened as a splendid connection between Potsdam and the imperial capital. Whether or to what extent renovations took place inside the building can no longer be proven, as the original files cannot be found and Lippert was dismissed from his office in July 1940. During the Second World War, probably from around 1942, the castle was changed to a hospital building and, after the capitulation, for a short time as an officers' mess for the Russian crew , who also used the upper floor as a horse stable.

In search of a suitable investor for the long overdue renovation work, the city of Berlin handed over the neglected palace complex to Berliner Sport-Toto GmbH in 1950 for use as a sports hotel. Until 1966, the maintenance and administration remained the responsibility of the Sport-Totos; then she went to the West Berlin administration of the state palaces and gardens . When the Sport-Toto gave up the sports hotel, the Heimvolkshochschule took over the rooms for school and overnight purposes from 1976 to 1986. During this time, the administration was the responsibility of the School and Youth Senator of the City of Berlin.

Todays use

Since the Heimvolkshochschule moved out and handed over to the palace administration on January 1, 1987, the building has been used as a palace museum after renewed renovation work, in which some rooms with furnishings from Prince Carl's possession can be viewed. Some of them come from various foundations and from the legacy of Prince Friedrich Leopold jun. to his partner Baron Cerrini, who in the 1970s gave the State of Berlin equipment and documents through several donations and a last will, with the proviso that they could be used in Glienicke. Baron Cerrini died on September 12, 1985. In addition to being used as a museum, the garden hall also hosts concerts on the weekends .

After German reunification and the amalgamation of the two palace administrations from East and West on January 1, 1995, the building is managed by the Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg , which also opened Europe's first court gardening museum on April 22, 2006 in some rooms of the palace . In addition to historical garden plans, measuring instruments, garden tools and contemporary furniture from a well-to-do family of court gardeners, biographies and historical documents show the diverse training of Prussian court gardeners. The tobacco pipe, the honorary citizen's letter of the city of Potsdam and a bowl with the laurel wreath on the 50th anniversary of the service of gardening director Peter Joseph Lenné , who has decisively shaped the image of the Berlin-Potsdam cultural landscape through his garden and landscape designs, are displayed in a showcase .

The Association of Friends of the Prussian Palaces and Gardens e. V. its office. The members are committed "to the preservation and restoration of the former royal palaces and gardens, which are looked after by the Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg."

architecture

The manor house

Neither views nor plans have survived of the manor house built in 1753. Since the subsequent owners are not aware of any renovation work, the possible appearance of Mirow's house is based on a drawing made by Schinkel in 1837, on which he recorded the condition of the building before the renovation in 1825. The sheet was published in the collection of architectural designs . Accordingly, the building was in the typical style of a manor house from the middle of the 18th century, two-story with a high hipped roof . A slightly protruding central projectile with a triangular gable extending into the roof emphasized the central axis on the west side. The manor house with an L-shaped floor plan and a rectangular farm building to the northeast formed a group of buildings in the shape of a "U".

Expansion through the construction of economic buildings

In addition to the beautification of the estate, Graf Lindenau had the U-shaped, north-facing group of buildings closed by building another farm building with a stable, so that a "loose square" was created. Like the manor house, the elongated building also received a hipped roof. As an extension of the new economic building, a small building was added to the east, which on later plans was called the Wagenremise. Changes to the manor house in Lindenau's time are not known. They only took place after the property was bought by the merchant Rudolph Rosentreter, who commissioned Karl Friedrich Schinkel to carry out the renovations. An expert opinion prepared for Prince Hardenberg before the purchase shows that Rosentreter “the performance of a balcon in the house, the construction of the lower floor, its new facilities, which have only just been completed […] furthermore the expansion of the driving shops, the furnishing of the lower floor Floor [...] approx. 8,000 ”has had it carried out.

Redesign of the exterior and interior

Prince Hardenberg had Schinkel continue the renovation work that had already begun under Rosentreter, so that the country house on the south side got a new look. As on the west side, the central part was also emphasized on the south front, but much more expansive. Schinkel put a semicircular extension in front of the ground floor , which corresponded to an apsidal niche slightly drawn into the building on the upper floor , creating an almost circular balcony.

|

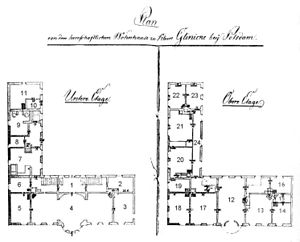

Floor plan (with key index) from 1817 Ground |

There were also structural changes inside. In order to achieve more room height, the ground floor was lowered by around 63 cm, as was the underpinning of the foundations. By removing transverse walls, a three-part hall was created on the ground floor of the south wing, to which various rooms were connected. As can be seen from a key plan drawn up in 1817, the green room and a girls' room were to the east , the Rothe room and a bathroom on the west side . In the west wing were the utility rooms such as the kitchen, pantry, laundry room and a service room . Two stairways in the vestibule on the north side of the south wing led to the upper floor. In the middle was the Blue Hall that ran across the entire depth of the building . The Prince's apartment with living room, green bedroom, secret cabinet and valet's room adjoined it on the east side . On the west side the princess had her rooms with anteroom, green corner room, pink cabinet and adjoining in the west wing the dark green room with cloakroom, the blue room, the small green room and the small red room. Due to a lack of space, guests and servants had to be accommodated in the adjacent utility building to the east, which later became the court ladies' wing, which was also converted for these purposes. Since there are no floor plans, details of the room layout are not known. The construction work was completed in the winter of 1816, but the subsequent owner was to start again nine years later. Again Karl Friedrich Schinkel received the order for a complete redesign of the building ensemble.

From the country house to the classical castle

After purchasing the property, Prince Carl initially lived in the country house without any structural changes. In January 1825, however, plans for renovation were already in place, which Ludwig Persius drew based on Schinkel's information. Drafts also drawn up by Persius for the redesign of the former farm building in the east, the so-called court ladies' wing, which had been changed under Hardenberg, followed in March 1825. The renovation work began in the spring of the following year and was completed in the summer of 1827.

Modification by Karl Friedrich Schinkel

Schinkel designed a summer palace for Prince Carl in the classicism style , essentially redesigning the outer facade and the building dimensions. He changed the floor plan of the group of buildings by shortening the court ladies' wing by a third of its length and connecting it to the main house, so that the garden courtyard inside the building complex opened further to the east towards the landscaped park. Schinkel removed the high hipped roof and covered the now gently sloping sheet zinc roof with a surrounding parapet , which he decorated at the corners with bowls and vases made of sanded cast zinc . The newly applied plaster was given the appearance of stone blocks through the scratched joints.

Schinkel gave the semicircular balcony extension from the time of Prince Hardenberg, built only ten years earlier, a stricter shape. He made it rectangular with two pillars and closed wall tongues on the sides. He replaced the apsidal niche above with three tall French windows between slightly protruding, fluted pillars and a cornice that ends at the top . The west facade got a similar appearance with a semblance of risalit . Schinkel let another balcony, which offered a good view of the pleasure ground and which could be entered from the corner room furnished for Prince Carl, run around the south-west corner. In order to loosen up the long horizontal of the south-facing parapet, a tower terrace was added to the roof. The cubic shape matched the architecture of the castle building and emphasized the middle section in a simple way.

The main entrance remained unchanged, accessible almost hidden from the garden courtyard. On the doorstep, brass letters on a white marble slab greeted the guest with the word SALVE. To liven up the austere facade, Schinkel placed a cast iron pergola , which he ran along the outer walls on the courtyard side, and with this design cited the Roman senator and writer Pliny the Elder. J. In letters to his friends Gallus and Apollonaris, he had described his villas Tuscum in the Apennines and Laurentinum south of Ostia on the Mediterranean. In addition to engravings of Greco-Roman buildings, Schinkel, in collaboration with Lenné, also found inspiration for his designs in Pliny’s villa descriptions, which not only influenced Glienicke, but later also the plans for Charlottenhof and the Roman baths in Sanssouci Park . Reconstruction drawings of the Tuscum and Laurentinum, which Schinkel made in 1833 based on the Pliny text, were published in the Architectural Album in 1841 .

The situation in Glienicke can be found in Tuscum, whose main entrance was a small, hidden door, accessible via a colonnade that framed the garden area. Helmuth Graf von Moltke , who lived temporarily in the Kavalier building as Prince Carl's adjutant , wrote in a letter to his future wife Marie in 1841: “The courtyard into which my windows look is wonderfully pretty. On a carpet of grass like green velvet a petite fountain rises, and all around is attracting a veranda with passion flower and Aristolochien is thickly clothed. "The facades had with Prince Carl spoils decorate, under the direction of the sculptor Christian Daniel Rauch purely decorative aspects were built into the outer walls. The floor was covered with corrugated cast iron plates with cross-joint division. Schinkel designed the pergola entrance simply with pillars and crossbars. Persius later rebuilt it like a temple. A mural painted by Julius Schoppe in 1827 , Pegasus washed and soaked by nymphs, adorned the south-western corner of the courtyard over an open fireplace. The painter used the painting of the tomb of the Nasonians from around 160 AD on the Via Flaminia near Rome as a model. The wall painting was destroyed by the neglect of the castle building in later times.

Remodeling inside

|

Floor plan around 1826 Ground floor |

Only sparse sources are available about the reconstruction of the interior of the palace at the time of Prince Carl. Information about the structural changes made by Schinkel is provided by a floor plan of the upper and lower floors, probably created around 1826, which can be used for comparison with the so-called key plan from 1817. In comparison, the floor plans do not reveal any significant changes in the interior of the castle. In addition to a few wall openings for connecting doors, some rooms were given a slightly different floor plan because new walls were drawn in or existing ones moved. These small conversions were mainly carried out in the west wing, whose utility rooms were then used as guest rooms, presumably for court cavaliers. The bathroom was spatially preserved. The kitchen was moved to the northern part of the court ladies' wing, which housed rooms for the secretaire, adjutant and cavalier in the south . A staircase in the middle of the wing led to the upper floor to the rooms, which probably occupied the servants. A billiards table was set up in the eastern area of the three-part garden room . The room bordering the hall to the east bears the name of a lady-in-waiting and the room adjoining it to the north is Jungfer.

On the upper floor, the Blue Hall, now called the Red Hall , was given a little more living space after the apsidal niche that extended into the room had been removed. The valet's room (key plan room 16) got a staircase to the attic and the former bedroom of Prince Hardenberg (key plan room 14) got a small balcony exit. In addition, the north wall to the Secret Cabinet behind it was broken through, so that a bed niche was created that now belongs to the bedroom. Prince Carl moved into the former rooms of Princess Hardenberg on the west side, while his wife Princess Marie lived in the Prince's smaller apartment to the east in exchange.

Changes by Ludwig Persius

As the successor to Karl Friedrich Schinkel, who died in 1841, Ludwig Persius took over the construction work in Glienicke. While Schinkel was still alive, at the end of the 1830s, minor decorations were planned for the palace building, but they were never implemented. Only the pillars and wall tongues of the balcony porch on the south side were clad with ornamental panels made of cast zinc. The ornamental design shows a band of acanthus volutes and putti with rural motifs on each medallion . The Berlin foundry Moritz Geiß carried out the work according to Persius , as noted under a catalog picture of the zinc casting company. Despite the reference to the architect, the authorship of the design is questioned by other sources, which refer to Schinkel or Christian Daniel Rauch . The redesign of the pergola entrance by Persius is definitely documented. In 1840 the simple entrance to the garden courtyard was given a four-column Doric portico in the style of a small propylon , which emphasized the entrance area in a more representative manner . A circumferential frieze made of cast zinc between the architrave and the triangular gable shows erots from Greek mythology and was created in the Geiß foundry based on a design by Schinkel. A lost today Akroter figure of Achilles by Christian Daniel Rauch crowned the roof ridge. Persius placed a rectangular stone bench next to the temple. The bench cheeks are each decorated with a hybrid creature with griffin feet, volute craters made of cast zinc adorn the high backrests.

In 1844 Persius increased the court ladies' wing. With a surrounding parapet, he adapted the roof area to the front view of the main building. In the mezzanine windows he placed lion supports as central pillars as an antique building decoration. They are zinc cast replicas of a Roman table support - a hinged metal stand on which a table top could be placed. Other minor changes to the palace building, such as individual walling up of ground floor windows, cannot be precisely dated. They probably took place in connection with renovations inside the castle. This also applies to the shallow niche on the west wing of the castle with a replica of Venus Italica. The original by Antonio Canova is in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence. The Glienicke figure can be traced back to 1938 and was later replaced by a new copy.

With the changes made to the palace building by Persius, the construction news ended during Prince Carl's lifetime. Information about the period after 1845 is hardly available or incomplete and mostly relates to other buildings in the Glienicke area. From 1859 onwards, Carl's interests increasingly focused on the renovation of the Glienicke hunting lodge , which was acquired in the same year and which is adjacent to the southeast on the other side of Königstraße.

Refurbishment measures in the 1950s and continued use

The dilapidation of the Glienicke buildings, which continued to increase for decades after the death of Prince Carl, only led to major renovation measures between 1950 and 1952 after the Second World War, so that the entire palace complex could be used as a dormitory for athletes with funds from the football toto. The central building of the palace, which was intended for lounges, remained largely unchanged with the Schinkel's room layouts. However, the remains of the original equipment details such as window and door frames, parquet floors and wall plaster were irretrievably removed and only restored in the style of Schinkel. The destruction of remnants of old building fabric was a not infrequently practiced procedure in the 1950s, the reasons for which can be found in the general reconstruction phase, which very often left neither time, interest nor opportunities for intensive investigations.

The renovation and spatial design of the side wings, in which the bedrooms were housed, were carried out from a pragmatic point of view. The court ladies' wing was completely gutted, a basement and extended to the north for the installation of a staircase in the upper floor. The small propylon erected by Persius at the entrance to the garden courtyard came to stand in front of the ladies' wing and has been the main entrance to the interior of the castle ever since. The cast iron pergola was replaced by one made of wood, which resembles the Schinkel form. Floor mosaics in front of the east-facing entrance door with the ligated mirror monogram "C" under the royal crown and St. John's crosses refer to the prince's first name and master's degree. Inside, the reception room, from which a hallway leads to the vestibule, administration rooms, a kitchen and the building services are accommodated. As a result of the renovations, the Schinkel's room and building proportions as well as the view from the garden courtyard to the east into the park were lost to this day.

The rooms of the castle museum

As for the renovation of the interior of the palace at the time of Prince Carl, there are just as sparse sources on its furnishings. References are limited to photographs taken by the architecture and art historian Johannes Sievers during inventory surveys in the late 1930s and 1940s and around 1950. They show the neglected condition of the castle rooms, but also some details of the furnishings.

The new furnishing of the castle after the renovation measures in the 1950s corresponded to the taste of the time, especially since the original pieces were no longer available. Already during an inventory in 1942, still during the war, Sievers noted: "No file, no letter has survived informing us about the type of furnishing of the castle and Schinkel's involvement in it [...]." However, copies of two of Schinkel-designed corner sofas returned to their original place in the 1950s. They are shown as immovable pieces of equipment in the floor plan drawn up in 1826 and were in the White Salon of the Prince Carl Apartment.

vestibule

After the few equipment details documented in photos by Sievers, the walls of the vestibule, the staircases and the steps in front of the stairs on the upper floor were painted white. Depending on the size of the area, they were divided into one or more rectangular fields by dark blue and cherry red lines, the ceiling of which was decorated as a flat triangle with acroteria at the tips or similar ornamentation. This wall design, reminiscent of simple Roman painting in its formal language , was reconstructed in the 1990s. A plaster medallion with the portrait of Princess Marie on the upper floor of the western staircase has been preserved. The relief set into the wall with a diameter of 53 cm was created by the sculptor Christian Daniel Rauch . The inscription PRINCESS CARL VON PRUSSEN V. CH. RAUCH on the outer edge names Marie and the leading Berlin sculptor since 1815.

Garden room

The Schinkel design of the entrance area to the garden room on the ground floor, which is two steps lower, has also been preserved from the time of Prince Carl. The double-leaf oak door is from a shrine with a straight fall of white marble and porphyry columns with white bases and composite capitals framed. Directly opposite the entrance area is the balcony porch with the three-leaf French door that leads to the pleasure ground. The space in the porch is interrupted towards the hall by two fluted Doric marble columns. In the middle of the garden room, the floor designed by Schinkel has been preserved, to which the architect gave a pattern of square, triangular and round shaped white and brown-red stone slabs. A stone inlay formerly inlaid in color in the middle field shows only the outlines of a winged woman with a water jug on an area of almost one square meter. There are no more room decorations that could reflect the furnishings in the 19th century. The originally three-part garden hall has been expanded to 123 m² by adding the rooms adjoining to the west and east. The walls are now painted white and the floor, with the exception of the remaining part, is covered with strip parquet.

Red hall

There is also only a few clues about the former design of the rooms on the upper floor. The Red Room was suitable as a banquet hall of the summer residence with a width of about six meters and a length of about ten meters only for smaller festivities. For the large receptions, Prince Carl used the more representative halls of his Berlin city palace on Wilhelmplatz. Schinkel had planned an approx. 30 cm high wooden panel made of mahogany as a wall decoration and above it a wall surface structured by painted, framed fields, which closed off the upper wall zone with a surrounding frieze of circles and rectangles.

The rooms, which were certainly furnished with objects in the style of classicism during Schinkel's time, underwent a change in the contemporary taste of historicism in the second half of the 19th century during Prince Carl's lifetime . A redesign of the red hall, which extends across the upper floor , is evident from a note by the court marshal on April 27, 1872: SKH inspected the buildings made during the winter […], and the very best of them examined the upper salon, which had been completely restored . A detail of the refurbishment is documented by a photo taken around 1950 that shows a fireplace with a mirror in the Neo- Rococo style . In addition, from the publication of the art historian Rudolf Bergau, “Inventory of Architectural and Art Monuments in the Province of Brandenburg” from 1885, it emerges that a clock in Boullework was part of the later furnishings of the Red Hall . Boulle furniture, baroque silver vases and Sèvres porcelain to decorate the adjoining apartments of the prince couple are also noted .

During the renovation in the 1990s, the hall was painted a monochrome red wall, a white ceiling and coffered parquet. The now lost chimney front in neo-rococo style on the east wall was exchanged for a classical one made of white marble in 1951. It dates from the Schinkel period and was originally built into the court ladies' wing. A 14-armed, fire-gilded tire chandelier with glass hangings, as well as a round mahogany table with a central column and three convex curved feet, is based on a Schinkel design from 1830. Schinkel designed another rectangular mahogany table on the west wall in 1828 for the palace on Wilhelmplatz. The top with maple inlays rests on two baluster-shaped, half-fluted legs that are supported by convex-concave curved feet. The feet, decorated with ornaments made of oil-gilded lead, are connected to one another by a turned, gilded crossbar. The ornamental design with palmettes , acanthus and pine cones at the end of the crossbar have adopted motifs from ancient times.

The museum table decoration shows a crater vase made around 1825 by the Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur Berlin (KPM) with gold-colored ornamentation and two motifs in the style of Pompeian painting. Two adjacent candelabra belonged to the original furnishings of Glienicke Palace. The 78 cm high candlesticks made of fire-gilded bronze were manufactured around 1837 in the Paris factory by Pierre Philippe Thomire , who made similar-looking models for the Versailles Grand Trianon and Pillnitz Palace in Dresden, among others . The Glienicke candelabra have a triangular, concave curved plinth. Three griffin feet attached to it carry a fluted ball and the fluted shaft that rests on it, tapering towards the top and decorated with stylized acanthus leaves at the ends. For the candles there is a holder in the middle and five outward swinging arms with decorative acanthus leaves.

Only a few pieces of the diverse silver work have returned to Glienicke. A long-lost silver wedding service created in 1827 for the wedding of Prince Carl to Marie von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach included a centerpiece based on the model of the Warwick vase on the north wall of the hall . The Berlin court goldsmith Johann George Hossauer created the silver work based on a design by Karl Friedrich Schinkel, who was modeled on the well-known marble bowl from the 1st century AD, which the archaeologist Gavin Hamilton in 1771 near Tivoli in the ruins of the Villa Adriana of the Roman Emperor Hadrian found.

In 1828 the silver centerpiece was shown at the Berlin Academy Exhibition when it was already in the possession of Prince Carl. The centerpiece can still be traced back to Glienicke until 1939, but was replaced by Prince Friedrich Leopold junior after the Second World War. sold. In 2008, twenty items from the wedding service were repurchased from the SPSG . Schinkel and Hossauer designed the Warwick vase like the original with motifs from the Bacchus mythology. Deviating from this, they closed the handle bowl with a lid crowned with a pine cone and placed the vessel on a conical base supported by four winged griffin feet, which they decorated with vine leaves and four sculptural panther figures. Large-format portraits and a bust with the image of the 30-year-old Prince Carl commemorate the former landlord and some of his family members. The work of the sculptor Julius Simony , a pupil of Gottfried Schadow , is dated to around 1832 because it was shown at the academy exhibition in Berlin that same year. Simony used a portrait painted by Franz Krüger around 1831 as a model . A painting by Kruger from 1852 shows Prince Carl at the age of 51. In the uniform of a general of the infantry, he is decorated with the Order of the Black Eagle , the Order of the Red Eagle , the Royal House Order and the Cross of the Order of St. John . Krüger probably added the Johanniterkreuz at a later date, as Prince Carl was not appointed master master until 1853. A painting by Julius Schoppe from 1838 shows the 30-year-old Princess Marie in a romantic garden landscape and a painting by Jan Baptist van der Hulst from around 1830 shows Prince Carl's youngest sister, Luise of Prussia , who married Friedrich von Oranien-Nassau in 1825 . Carl von Steuben portrayed her husband as early as 1815 at the age of about 18. On Prussian uniform he wears the Dutch Military Wilhelm Order, the Iron Cross on a black ribbon and the Black Eagle Order, which was awarded to him in 1815 for his services to Prussia in the fight against the Napoleonic occupation. The largest painting in the Red Hall is an equestrian painting by Antonio Schrader . It shows the Prussian king and father of Prince Carl, Friedrich Wilhelm III. , during the Wars of Liberation and in a pose similar to the one Jacques-Louis David Bonaparte portrayed when crossing the Alps on the Great Saint Bernhard . The skyline of Berlin can be seen in the background under a dark sky.

Green Salon

The former apartment of Princess Marie is adjacent to the Red Hall to the east. The Green Salon and the adjoining Green Bedroom were her only private rooms in Glienicke Palace. There was nothing left of the furniture from the Schinkel era by the end of the 1930s. A photo from 1938 in the Green Salon can only prove a fireplace front that is now lost and decorated with gilded strips and pearl bars . The wall above was decorated with a stencil painting with stylized acantus volutes .

During the restoration in the 1990s, the former living room was painted in a single color in the color of Schweinfurt green and a floor covered with coffered parquet. Today's museum equipment with Schinkel furniture includes a tire chandelier made in 1830 with bronze ornamentation and glass hangings, which is similar to the chandelier in the Red Salon . Two black-lacquered upholstered chairs and an upholstered armchair in the Sheraton style with gold-plated low cut, gold-plated lead ornaments and yellow cloth coverings are remnants of a suite from 1828 that originally stood in Princess Marie's living room in the Berlin palace on Wilhelmplatz. Schinkel found the inspiration for the chair model on his trip to England in 1826 in Landsdowne House in London's Berkeley Square (Westminster). A chaise longue in the style of a Greek Kline probably also comes from the living room of the Berlin Palais . The black lacquered lounger with pink cloth covering and gold-plated lead ornamentation at the foot end and the curved headboard was a popular piece of furniture for the elegantly furnished “lady's boudoir” in the late 18th century.

A mahogany side table, also made according to English influence, and designed for card games comes from Glienicke Castle. Round and rectangular shelves the size of playing cards can be folded out on the 28.5 × 28.5 cm plate, which rests on a 78 cm high hexagonal column. Another small side table shows medallions with motifs of Berlin buildings and the casino in Glienicker Park on a round porcelain plate made by KPM, framed with gold-colored arabesques . A mahogany table with a square top that can be opened to enlarge the table surface originally stood in the Berlin City Palace . It came to the Doorn house in 1919 , Wilhelm II's exile in the Netherlands . Porcelain from the possession of Prince Carl, manufactured by KPM, is on display in a rosewood showcase made around 1825/30 with inlays. In addition to plates with floral decorations from 1820 and 1845, two plates show Glienicke motifs. They were probably made between 1870 and 1889, because on one of the gold-rimmed plates the Glienicke hunting lodge is still depicted in the French Baroque style, i.e. before the renovation in 1889, the other was painted with the view of Glienicke Palace and the lion fountain. On the showcase is a so-called Redensche crater vase with Berlin motifs, also made by KPM around 1820 . Works by contemporary artists from the 19th century hang on the walls. These are paintings with Glienicke motifs by Johannes Joseph Destrée , Eduard Gaertner and Julius Schoppe, a still life by the later director of the KPM, Gottfried Wilhelm Völcker , and portraits of Princess Marie by Julius Schoppe and Queen Luise by Johann Heinrich Schröder .

bedroom

The former turquoise-colored bedroom of Princess Marie underwent an unfavorable structural change in 1889. Prince Friedrich Leopold Sr. had the north wall with the bed niche drawn in the plan from approx. 1826 and a chimney standing across the corner to the left removed so that the room went through the entire depth of the building. By walling up a window on the north side of the garden courtyard, the elongated room only got daylight through a window in the south wall. In the 1950s, the room was subdivided again by inserting partition walls, but without taking the bed niche into account. This is how the room arrangement was created again as in the time of Prince Hardenberg.

Today's furniture includes an upholstered mahogany armchair and a mahogany chair with wickerwork, the only adornments of which are the slender, baluster-shaped turned front legs - a characteristic feature of Schinkel's chair models. The simple, bourgeois furnishings come from the Glienicke Palace and show the sometimes simple furnishing style of the summer palace, which, in contrast to the city palace, hardly had to serve representative purposes. A dressing table with a mirrored back wall from 1820 and a sofa with mahogany veneer from around 1830 from the destroyed Berlin City Palace are kept in an equally simple form. Both pieces of furniture are attributed to Schinkel. The walls are decorated with paintings with Italian landscapes by Konstantin Cretius , Ferdinand Konrad Bellermann , Julius Helfft , Heinrich Adam , Carl Ludwig Rundt and Carl Wilhelm Götzloff, as well as a view of Glienicke, seen from the Potsdam New Garden , by Karl Wilhelm Pohlke .

White salon

The former apartment of Prince Carl adjoins the Red Salon to the west, beginning with the White Salon, also known as the marble room . The Schinkel's interior design could be most accurately reconstructed using photos. Like the original, the copies of the corner sofas drawn in the floor plan from around 1826 were given a white lacquered wooden frame, seat upholstery that almost reached the floor and an upholstered back with red fabric cover. Gold-colored borders running horizontally on the front give the impression of two seat cushions lying on top of each other. Two round tables with volute feet replace the square marble tables with a central column originally designed by Schinkel. On the wall surfaces made of white stucco marble, the gold-colored stripes are repeated through vertical lines in the wall corners and in a surrounding frieze in the upper wall zone as well as on the profiled door walls and the entablature above. Other wall decorations are plaster busts on consoles in front of rosette-shaped wall niches. The busts depict Princess Marie, the garden architect Peter Joseph Lenné and Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Models were modeled on the sculptor Christian Daniel Rauch.

In addition, the original furnishing of the room probably included armchairs on castors with an unusually low back, snail-shaped volute armrests and baluster-shaped front legs. The four massive Schinkel armchairs are assigned to the White Salon because of their white paintwork and are parts of the auction mass from 1930/31. Until they are on display again after restoration on loan from the Kunstgewerbemuseum der Staatliche Museen Berlin in Glienicke, they will be replaced by two armchairs that Schinkel designed in 1828 for the reception room, the so-called reception room , of Princess Marie in the Berlin Palais on Wilhelmplatz. Schinkel designed the oil-gilded beechwood chairs with gold-colored fabric cover with narrow armrests and attached upholstery. They rest on scrolling volutes that enclose a rosette with a floral ornament. A similar ornamentation can be found in the side seat borders made of cast metal. The basic shape of this armchair goes back to a type of chair that was depicted on a frieze in Herculaneum and was published in the archaeological work Antichità di Ercolano in the 18th century. Schinkel also designed other grand armchairs in this style, only with sphinxes as armrests, for the reception hall in the Palais on Wilhelmplatz as well as the tea room and the star room in the Berlin City Palace. A lampshell made of milk glass was also made according to a Schinkel design around 1825/1830. The bowl is framed with an ornamental frame made of gold-plated cast zinc and has eight candlestick arms swinging outwards.

Blue corner room

The blue corner room to the west was the library and study of Prince Carl. Wall surfaces originally in a shade of blue and a circumferential frieze with a floral pattern could be determined from remains on a photo taken around 1950 for this room. The furniture probably included a simple, four-door bookcase, the door glazing of which was divided by three rungs and had an almost square glare field in each of the lowest door zones. A dark brown stencil painting made of lines, leaves and rosettes on the surrounding cornice can also be found on maple armchairs. Due to the identical ornamentation, the pieces of furniture recorded in photos are assigned to this room as they belong together. The whereabouts of the Schinkel furniture designed around 1828 is unknown.

The only pieces of furniture in the inventory of Glienicke Castle based on a design by Schinkel are two upholstered chairs made of mahogany with a yellow fabric cover. In addition to the baluster-shaped turned front legs, the chairs are adorned below the half-length back upholstery with a wooden lattice ornamentation of rosettes with finials and acanthus leaves that almost extends to the seat. The most elegant seating furniture designed by Schinkel is an armchair with an English influence. It comes from a set that was designed in 1828 for the living room and study of the prince in the Palais on Wilhelmplatz. Schinkel used rosewood for the first time here, rosewood which became fashionable during the English Regency period . He designed the graceful chair on castors with a low seat on fluted front legs, narrow, round upholstered armrests supported by delicate polished brass balusters, and a back with a narrow, wooden headboard and a crossbar with rose ornamentation. The original covering made of cherry red cloth could be discovered and rewoven under later renewed covers.

A cast iron replica of the famous and often copied Warwick vase stands on a mahogany-veneered wooden pedestal with a three-tier curved base on the south wall . From Charlottenburg Palace and the inventory of Friedrich Wilhelm III. comes a mahogany sofa in the Biedermeier style with a yellow-colored fabric cover and a matching mahogany table. A few books from Prince Carl's previously well-stocked library and personal items are on display in a small bookcase that comes from the estate of the art historian Sievers. One of these is an inkwell, which was made from the hoof of the hunting horse Agathon , who died in 1854 and which stood in the prince's stables for over twenty years from 1828. The hollowed out hoof is closed by a brass lid. A crowning fork of branches with the ligated mirror monogram "C" under the Prussian crown in the middle served to place a pen holder. An engraving on the front of the hoof reminds of the hunting horse : AGATHON born 8 / 4.22 † 29 / 10.54 . A picture painted by Franz Krüger on the north wall of the Blue Corner Room shows the prince's favorite horse. Further paintings adorn the walls with portraits of Prince Carl by the artists Nikolaus Lauer and Christian Tangermann as well as Glienicke views by Adalbert Lompeck and Julius Schoppe. Constantin Schroeter painted the long-time servant Mohr Achmed, who was first mentioned in 1828 as Prince Carl's servant .

Workspace

Like the library, Princess Hardenberg's former Pink Cabinet also served as a study for Prince Carl. Nothing is known of the original decoration and furnishings, as is the case with the bedroom that followed, already in the west wing, and the servants' rooms adjoining it, in which the court gardener museum is now located.

The small room houses leftover pieces of porcelain, silver tableware, glass vessels and watercolors from Prince Carl's possession. The watercolors from around 1830 to 1835 are by Franz Krüger and show detailed drawn carriages and sleighs that Prince Carl used on his travels in Russia or that belonged in large numbers to his vehicle fleet. KPM adopted the watercolor series as a template for dessert plates, of which only a few can be shown in Glienicke Palace because most of the porcelain was lost in the 1931 auction. This includes a series of motif plates designed by KPM between 1825 and 1828 based on its own templates, of which only three plates with views of the casino, the castle and the castle courtyard in Glienicke have survived, as well as two plates from a KPM series with depictions of plants according to Pierre -Joseph Redouté from 1823 to 1837.

Of the table glasses and glass carafes, only a few individual pieces have survived. Depending on the intended use, they have beaker, bowl or funnel-shaped glass, some with a gold rim and baluster-shaped shaft, others with eight-sided faceted walls. As the most striking feature and decoration on all glass parts, a gold-plated deep cut with either the simple monogram or the ligated mirror monogram "C" under the Prussian royal crown indicates the former owner Prince Carl. The monograms can also be found on silver work from Johann George Hossauer's workshop, but also deviating from an owner's mark designed by Schinkel with an eagle in the circle of the chain of the Black Eagle Order under the Prussian royal crown. Hossauer, who in 1826 by Friedrich Wilhelm III. was awarded the title of Goldsmith His Majesty the King , was one of the most famous goldsmiths of his time and worked closely with Schinkel. His silver work was shaped by the styles of the baroque . Of the many works he made for Prince Carl, there are only two sugar cans, two silver bowls, four brandy tumblers, a candlestick with a fire hat, a kettle with réchaud , a presentation bowl , three wine coasters and a wine cooler from the period between 1820 in addition to the Warwick vase and issued in 1864. Also on display is a court marshal's baton, which was used for ceremonies at receptions and whose silver parts Hossauer designed: a long silver tip with a steel ball at the lower end of the polished wooden staff and a silver pommel on the opposite side with a riveted Prussian eagle wearing a crown and in his Catching the Cross of the Black Eagle Order. The Collar of the Order encloses the pear-shaped knob.

Corridor on the upper floor of the west wing

The elongated hallway on the east side of the west wing, from which the rooms of the Court Gardener Museum can be entered today, is equipped with portraits of Prussian court gardeners, including members of the Salzmann, Nietner , Sello , Fintelmann and the Garden artist Peter Joseph Lenné belong.

The once colorful design of the hallway in the 19th century can again be proven by excerpts from photos taken in 1937. Then the decoration of the west wall in the lower area consisted of a half a meter high paper wallpaper, which simulated a marbled wooden panel divided into fields, and above it a panoramic wallpaper with Italian landscapes, the individual motifs of which were divided by arbor posts. The manufacturer of this hand-printed wallpaper Les Vues d'Italie from 1818 was the French manufacturer Zuber & Cie. from Rixheim in Alsace , the creative artist Pierre-Antoine Mongin. The opposite side of the window facing the garden courtyard was clad with painted or wallpapered wall blocks and the ceiling was given an arbor roof. According to Schinkel's specifications, Julius Schoppe designed the north wall at the end of the hallway with a panoramic view of the island of Capri. The overall picture suggested an arcade with wide views of Italian landscapes on one side and, on the other, from the real windows, the view of the Italian-style garden courtyard with its decorations from antiquity.

The design of individual rooms with landscape wallpaper was very modern since the beginning of the 19th century. In addition to the educational properties, the large-scale landscape pictures created the illusion of being in a foreign country or distant continent. The sensations of a viewer are described by Jean-Jacques Rousseau , who perceived panoramic images as “a feast for the eyes” “from which an indefinable touch of magic and supernatural emanates that stimulates the mind and the senses. You forget the world, you forget yourself, you no longer know where you are. "

Outbuildings

Cavalier wing

The farm building with horse stable built in 1796 under Count Lindenau in the north was extended to the east in 1828 and a full storey was added. According to Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Ludwig Persius drew the plans for the renovation. Adapted to the Italianizing style of the castle, a building was created in the style of simple southern houses with a gently sloping, protruding hipped roof made of zinc sheet, window openings with shutters and a flat-roofed pergola with massive pillars at the southwest end, which connects the cavalier wing with the castle. As on the palace building, Prince Carl had the south side of the garden courtyard decorated with spoilers from ancient times, the decorative arrangement of which was carried out by the sculptor Christian Daniel Rauch.

In the middle of the south facade, a bronze copy of the Ildefonso group of the original was placed in the Museo del Prado in Madrid . The interpretation of the two young men with laurel wreaths is still controversial today. According to Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Orestes and Pylades were current interpretations at the time, and sleep and death according to Lessing . Made by the Gräflich Einsiedelschen Eisengießerei in Lauchhammer , the group of sculptures has been cast several times and placed in various locations, including in the Charlottenhof section of the Sanssouci Park. Schinkel and Persius designed the eastern part of the south facade, which extends beyond the building line of the castle, with a stone bench in a vine arbor. The bench with stepped sidewalls can be found until 1937, but is no longer there today. Above that, figure casts decorate the upper floor. In the middle is the Felicitas Publica , the original of which was created by Christian Daniel Rauch for the Max Joseph Monument in Munich. It is flanked by statuettes of Iphigenia and Odysseus . They are works from the workshop of the sculptor Christian Friedrich Tieck . The corner of the building is adorned with a cast zinc head of Athena .

The naming "Kavalierflügel" or "Kavaliergebäude" is misleading, as this designation suggests a purely residential building. In fact, it was designed from the start as a residential, farm and stable building. The entrance on the eastern narrow side led to the upper floor and a servants' apartment on the ground floor. This was followed by a horse stable with 24 boxes and a kitchen and washrooms in the western third. The upper floor had an apartment for the inspector in the east , servants' rooms, granaries and utility rooms in the middle. On the west side there were rooms for the stable master, cooks and two guest rooms. Two rooms, from which the roof of the pergola could be used as a terrace, served as accommodation for Prince Carl's personal adjutants, who were at times Count von Moltke and Prince zu Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen . From 1832 the adjutants' rooms could be reached directly via a second flight of stairs, which one entered via the pergola architecture. Further small alterations to the interior were carried out in 1872 by the Potsdam master builder Ernst Petzholtz , who replaced the wooden supporting structure from the Schinkel era with a cast-iron one in the horse stable. The floor, which was probably still paved with yellowish-red bricks by Count Lindenau, was given a new covering made of clinker bricks.

After Prince Carl's death, the Cavalier Wing, like all the buildings in the park, fell into disrepair. Over the decades, the castle building was repaired and used by various institutions at the same time. During renewed renovation work in 1988/89, the cast-iron supporting structure, which was clad in the 1950s, and the floor were exposed. The former horse stable has been used for events since March 2006.

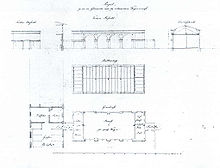

Remise and tower

The building from the time of Count Lindenau, referred to as a carriage shed on old construction plans, had to be demolished because of the eastward extension of the farm building or the cavalier wing. As a replacement, Ludwig Persius drew up drafts for a new coach house in 1828 according to Schinkel's information and set it to the north, at right angles to the western part of the cavalier building. The single-storey car hall got a flat sloping roof made of zinc sheet. On the east-facing front, four arcades with wooden gates led into the Remisenhalle, which, according to Persius' design drawing, offered space for twelve carriages. Two rooms were attached to the north of the hall, which served as a peat enclosure and a wooden stable . An oven connected to the outside. On the south side was a saddle and harness room. From here a passage led to the horse stables in the cavalier building. Schinkel had the Remisenhof enclosed in the north with a wall and in the east with a lattice fence.

A figure of Neptune in the center of the lattice facing the courtyard was only put up on June 23, 1838 and was a birthday present from Friedrich Wilhelm III. to his son. It is a second version of the Neptune figure, which the Rauch student Ernst Rietschel created for a fountain in Nordhausen . The water basin in the form of a shell comes from a marble colonnade in Sanssouci Park, which was built according to plans by Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff from 1751 to 1762, but was demolished again in 1797 . Prince Carl had another shell set up below the south-facing pergola of the casino.

In order to loosen up and revitalize the group of buildings by means of a vertical structure, Persius created plans for a tower according to Schinkel's information. A five-story tower with narrow, high-rectangular window openings and a belvedere on the top floor was built between the coach house and the cavalier building . The flat tent roof made of zinc sheet was given an antique finish on the edge by means of antefixes . The tower could be entered through an entrance in the north and one from the washroom in the western part of the cavalier building. Major renovations were carried out during Prince Carl's lifetime. Ernst Petzholtz, who increased the tower by one storey in 1871/1872, received the order for the planning and execution. The remise was also increased, which he also lengthened by an arcade arch and a basement. The tower kept the narrow window slits and opened again on the sixth floor with Serlian windows to a belvedere. Likewise, the now flat gable roof was given antique-looking architectural decoration through acroteria in palmette ornamentation. After decades of neglect, the dilapidated shed was demolished in the 1950s and only the basement was rebuilt. Another one-story building was added at right angles, which instead of the wall forms the end of the courtyard to the north. The Remise has been used for catering since 1986.

literature

- Administration of the State Palaces and Gardens Berlin (Ed.): Glienicke Palace . Hartmann Brothers, Berlin 1987.

- Foundation Prussian Palaces and Gardens Berlin-Brandenburg (ed.): Ludwig Persius - architect of the king - architecture under Friedrich Wilhelm IV. 1st edition. Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2003, ISBN 3-7954-1586-1 .

- General management of the Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg (ed.): Ludwig Persius - Baukunst under Friedrich Wilhelm IV. - Architectural guide . 2nd corrected edition. Rudolf Otto, Berlin 2003.

- Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg (Ed.): Glienicke Palace and Park . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin / Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-422-04022-9 .

Web links

- Glienicke Castle . Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg

- Entries in the Berlin State Monument List

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Louis Schneider: The electoral hunting lodge at Glienicke . In: Communications of the Society for the History of Potsdam , meeting on September 30, 1862, Potsdam 1864

- ^ A b Michael Seiler: The history of the creation of the landscape garden Klein-Glienicke. In: Administration of the State Palaces and Gardens Berlin: Glienicke Palace . Pp. 111, 112

- ↑ a b Michael Seiler: The development history of the landscape garden Klein-Glienicke 1796-1883 . Diss. Hamburg 1986, pp. 30-40

- ^ Michael Seiler: The history of the development of the landscape garden Klein-Glienicke 1796-1883 . Diss. Hamburg 1986, p. 51 f

- ↑ Hermann Fürst von Pückler-Muskau: Hints about landscape gardening . Fifth section, Park and Gardens, Stuttgart 1834, p. 52

- ↑ Foundation Prussian Palaces and Gardens Berlin-Brandenburg, retired garden director. D. Prof. Dr. Michael Seiler. Lecture on Glienicke on September 3, 2006 in Glienicke Castle.

- ^ From: Letter from Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm to his former tutor Friedrich Delbrück from December 6, 1810. In: Johannes Sievers: Buildings for Prince Karl of Prussia (Schinkel's life's work) . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin 1942, p. 3

- ↑ Prince Carl's will. In: Johannes Sievers: Buildings for Prince Karl of Prussia (Schinkel's life's work) . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin 1942, p. 165

- ↑ Jörg Kirschstein: Prince compensation ( Memento from March 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) . In: Website of the House of Hohenzollern

- ↑ a b Jürgen Julier: Glienicke in the 20th century . In: Administration of the State Palaces and Gardens Berlin: Glienicke Palace . Pp. 185-186

- ^ Malve Countess von Rothkirch: Prince Carl of Prussia, connoisseur and protector of the beautiful 1801–1883 . Osnabrück 1981, p. 237

- ^ Friends of the Prussian Palaces and Gardens e. V. , accessed on September 23, 2015.

- ↑ Jürgen Julier: The castle. Building history before 1824 . In: Administration of the State Palaces and Gardens Berlin: Glienicke Palace . P. 9

- ↑ Quoted from Seiler. From: Michael Seiler: The development history of the landscape garden Klein-Glienicke 1796–1883 . Diss. Hamburg 1986, p. 43

- ^ From: Letter from July 1841 from Helmuth von Moltke . In: Administration of the State Palaces and Gardens Berlin: Glienicke Palace . P. 321

- ↑ Moritz Geiß: Zinc cast ornaments based on drawings by Schinkel, Stüler, Strack, Persius ... in precise illustrations according to the scale for use by architects, builders and all those who are devoted to ornamentation . Issue 13, plate 4, Berlin 1863

- ↑ Johannes Sievers: Buildings for Prince Carl of Prussia (Schinkel's life's work) . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin 1942, p. 47

- ^ From: Journal , Glienicke 1872. In: Administration of State Palaces and Gardens Berlin: Glienicke Palace . P. 23

- ^ Winfried Baer: Furniture from the Prinz-Carl-Palais on Wilhelmplatz . In: Administration of the State Palaces and Gardens Berlin: Glienicke Palace . Cat.-No. 566, p. 520

- ^ Winfried Baer: Furniture from the Prinz-Carl-Palais on Wilhelmplatz . In: Administration of the State Palaces and Gardens Berlin: Glienicke Palace . Cat.-No. 567, p. 521

- ^ Administration of the State Palaces and Gardens of Berlin: Glienicke Palace . Cat.-No. 563, p. 519

- ↑ a b Administration of the State Palaces and Gardens: Glienicke Palace . Cat.-No. 565, p. 520

- ^ Winfried Baer: Johann George Hossauer, goldsmith of Prince Carl . In: Administration of the State Palaces and Gardens Berlin: Glienicke Palace . P. 231

- ↑ Johannes Sievers: Buildings for Prince Carl of Prussia (Schinkel's life's work). Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin 1942, p. 39 ff

- ^ Francois Robichon: From Panoramas to Panoramic Wallpapers . In: Odile Nouvel-Kammerer: French Scenic Wallpaper 1795-1865 . Flammarion, Paris 2000, p. 165

- ↑ General Directorate of the Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg: Buildings and sculptures in Sanssouci Park , p. 75

Coordinates: 52 ° 24 ′ 51 ″ N , 13 ° 5 ′ 43 ″ E