Klein-Glienicke Park

| Palaces and gardens of Potsdam and Berlin | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

| National territory: |

|

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | i, ii, iv |

| Reference No .: | 532 C |

| UNESCO region : | Europe and North America |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1990 (meeting December 12, 1990) |

| Extension: | 1992 and 1999 |

The Park Klein-Glienicke , colloquially called Glienicker Park , is a publicly accessible English landscape garden , which is located in the extreme southwest of Berlin in the Wannsee district of the Steglitz-Zehlendorf district. It is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Palaces and Parks of Potsdam and Berlin (Potsdam's cultural landscape). Along with Sanssouci , the New Garden , the Pfaueninsel and the Babelsberg Park, it is one of the five main parks.

The 116 hectare complex was designed as the Potsdam summer residence of Prince Carl of Prussia in the 19th century and supplemented his main residence, the Prince Carl Palace on Berlin's Wilhelmplatz . The design focus is the princely villa called Schloss Glienicke in the south of the park, now accessible as a museum. The palace , outbuildings and pleasure ground belong to the Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg . The actual park is subordinate to the district green space authority Steglitz-Zehlendorf and the Böttcherbergpark to the Berlin state forest administration .

designation

The official historical name was from 1824 " Park of Prince Carl of Prussia ", and from 1885 " Park of Prince Friedrich Leopold of Prussia ". It was not until the 20th century that geographical terms became common. The term “ Volkspark Glienicke ”, which is often misunderstood as democratic today, comes from the dictatorial era. After the city of Berlin had acquired the park in 1934, the programmatic name should make clear that the National Socialist policy of the city the park paid had. Since Glienicke Palace was not a princely residence, the entire complex cannot be described as a “ palace park ”.

Historical outline

prehistory

The church and jug-free village of Klein-Glienicke , first mentioned in 1375 in the land book of Emperor Charles IV. , Was built in the west of Glienickschen Werder on the isthmus between Griebnitzsee and Glienicker Lake . As a result of the Thirty Years War , the village became desolate. Resettlement with colonists was difficult in later decades .

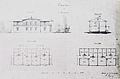

A hunting lodge was built next to the uninhabited village spot in 1682 under the Great Elector Friedrich Wilhelm . It consisted of a simple cubic residential building and two side farm buildings that formed a modest courtyard . A garden was laid out as a rectangle in the middle of the swampy floodplain of the Havel and provided with four carp ponds.

The village center was restructured by creating a four-row landscaped avenue from the castle towards the Griebnitzsee. It was flanked to the north by a newly dug canal, which connected Griebnitzsee and Glienicker Lake in a navigable way and replaced the old mouth of the Teltower Bäke . At that time the area of today's Babelsberg Park was part of the enclosed wildlife park. In the north there was a tree garden, an old vineyard (today Böttcherbergpark ) and a new vineyard, as the map by Samuel de Suchodolec tells us.

The first wooden Glienicke bridge was built as early as 1660, but it did not yet mean a direct traffic connection to Berlin , but only led to Potsdam , or via Stolpe enabled a detour to Berlin via the road connection which was later expanded to the Königsweg .

Under King Friedrich Wilhelm I , the so-called soldier king , the hunting lodge was converted into a Potsdam military hospital in 1715 for sick soldiers who had to be separated. North of the hunting lodge area, the hospital superintendent and doctor Dr. Mirow an estate. This consisted of the stately manor house built in 1753, which was already known colloquially as a castle, a small billiard house on the Jungfernsee, farm buildings, agricultural areas and a brick and lime kiln .

With the construction of Berlin-Potsdamer Chaussee in 1792, the two systems were spatially separated from each other. While the hunting lodge subsequently degenerated into a factory and then an orphanage through misuse, the manor complex to the north gradually developed into a princely park.

Beginning of the park design under Count Lindenau

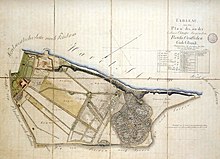

In 1796, the Prussian head stable master, Count Carl von Lindenau, took over the estate for 23,000 thalers. He had previously set up a nationally known park in Machern near Leipzig and transferred his experience there to Glienicke. A ferme ornée ( ornamental farm ) grew out of the previously purely agricultural areas , in which the fields and pastures were bordered by 16 different avenues and the first landscaped gardens.

Lindenau had various small architectures built in Glienicke, presumably by Ephraim Wolfgang Glasewald , who had created the buildings for the head stable master in Machern. The “ garden salon ” at the site of today's stibadium, which was laterally bordered by greenhouses, deserves special mention . The massive pavilion had elegant early classicist styles, its entrance portal was flanked by two sphinx figures . Nearby, a tea pavilion called “ Curiosity ” was built on the Chaussee. As a special ornament he had a reclining sphinx figure above the entrance. The billiard house Dr. Mirows had Lindenau expanded.

In addition, farm buildings were built, including a horse stable, a grain barn, a greenhouse, an arbor, the ice pit and a shooting wall. Probably the most important source of income remained the brickworks and lime kiln, which extended over a comparatively small area of about 160 × 120 meters and received a new, large brick shed. Lindenau had about 3,000 trees brought to Glienicke from Machern .

In 1802 Lindenau sold Machern and in the following years devoted himself intensively to the expansion of the Glienicker facilities. With the defeat of Prussia under the Napoleonic troops in 1806 and the stagnating Prussian economy as a result of the French occupation, Lindenau also got into economic difficulties. In 1807 he was also retired from civil service and felt compelled to sell Glienicke. But the sale of estates proved to be almost impossible at the time. After the idea of playing Glienicke in a lottery had proven to be unfeasible, Lindenau temporarily leased the stately property. At the same time he was preparing to move to his estate in Büssow (now Buszów) in Neumark .

Design of Glienicke under Prince Hardenberg

From 1810 Karl August von Hardenberg , who had just been appointed State Chancellor by the King, rented the property. Glienicke was inhabited by the most powerful politician in Prussia and his third wife Charlotte. However, Hardenberg could not make up his mind to buy it due to his constant financial bottlenecks. He had to vacate Glienicke again at the end of 1812 after the merchant Rudolf Rosentreter became the new owner for 20,000 thalers.

He invested significant funds in his new property, so he had Karl Friedrich Schinkel erect a semicircular porch in front of the south facade of the palace and set up a garden hall. Rosentreter was the first to employ Schinkel, now known as the creator of diagrams and paintings, but who had not yet come out with outstanding architecture, in Glienicke.

1814 Hardenberg was by King Friedrich Wilhelm III. raised to the hereditary prince's status and received as a gift the rulership over the office Quilitz, which was renamed Neu-Hardenberg . Hardenberg now had the necessary financial means to acquire Glienicke, whereby Rosentreter was interested in selling it and achieved 34,500 thalers for the property. In addition to his Berlin city palace on Dönhoffplatz , the Lichtenberg and Tempelberg estates , the Lietzen commandery and the Neu-Hardenberg class rule, the state chancellor now also had a summer residence near Potsdam.

Hardenberg led the Glienicker plants to their first artistic boom. Hardenberg had known Schinkel since he was transferred from Ansbach to Berlin in 1798. The latter had already carried out buildings in Quilitz around 1800 and, as a Prussian construction officer appointed in 1810, undertook a partial refurbishment of the Hardenberg city palace. In Glienicke, Schinkel continued the renovation work he had begun on the castle for Rosentreter . Hardenberg may also have worked to ensure that the then journeyman gardener Peter Josef Lenné was appointed from Bonn to Potsdam. Hardenberg brought Schinkel and Lenné together in Glienicke and thus established an extremely fruitful collaboration.

Glienicke also got its own gardener , Friedrich Schojan, who previously worked in Tempelberg. Hardenberg had numerous trees transferred from Tempelberg to decorate Glienicke. In 1816 Hardenberg commissioned Peter Joseph Lenné with a design for the Glienicker gardens. The twenty-seven-year-old Lenné had recently applied from Bonn for a job at the royal gardening director in Potsdam and had been employed as a gardener's assistant on probation. The Glienicker Garten was his first private contract. He was able to convince Hardenberg of acquiring a small Büdner position on Berlin-Potsdamer Chaussee and subsequently created a pleasure ground in the spirit of English landscape gardening between the castle , the Chaussee and the bridge keeper's house . This garden was located in a scenic spot in the Potsdam area, was clearly visible from the Chaussee and accordingly attracted a lot of attention. Due to Hardenberg's social status, this garden was of course also known to the royal family, the nobility and many public servants through visits.

Hardenberg also had an art mill built to operate water features . However, the brickworks continued to operate and is likely to have spread some unrest directly adjacent to the Pleasureground . In the north of his property, Hardenberg had a family house (small apartment house) built with four residential units in 1816 , which a decade later was to take over the role of a hunter's farm.

Schinkel not only planned for Hardenberg, but since 1820 also for his son-in-law, the enthusiastic garden designer Hermann von Pückler-Muskau . Accordingly, there was an artistic connection here that influenced the design of the Glienicke park very early on. In 1822 John Adey Repton, son and most important colleague of Humphry Repton, visited Prince Pückler in Muskau . The latter also took the English guest to Glienicke, where both of them stayed for a good week. After his return to England, Repton designed a “Hardenberg Basket” for a customer, a rose bed in a wooden basket in the middle of a round flowerbed. This bed shape subsequently enjoyed some popularity and was also published by Pückler as exemplary. The garden historian Seiler thinks that Repton saw such a basket in Glienicke and used it as a model, especially since Glienicke was more advanced in gardening than Neu-Hardenberg. As a result, Glienicke went down in European garden history for the first time with the “Hardenberg Basket”.

In November 1822 Hardenberg died unexpectedly in Genoa . His son Christian Graf von Hardenberg-Reventlow planned to sell Glienicke. Apparently he wanted to sell the property to a worthy buyer, because the sales negotiations dragged on for over a year until March 1824. The buyer became Prince Carl of Prussia. How exactly it came about that the king's third-born son, who was not even married, was given his own property as the king's first son, has not yet been clarified. However, he must have been viewed as a suitable buyer for the princely property for everyone involved, the sale of which has now reached 50,000 thalers. Carl acquired a modern, economically fully functional property from Hardenberg's heirs, which was largely modernly furnished and equipped and stood out for its gardens.

Prince Carl's Park

Prince Carl acquired the facility at the age of twenty-two. Since he reached an old age, he was able to design and expand Glienicke for almost 60 years. Initially, he continued seamlessly with Hardenberg's designs. The farm was gradually reduced to the facilities necessary for personal use (dairy farming and flocks of sheep for grazing) in favor of the park. The brick and lime kiln was completely closed in 1826.

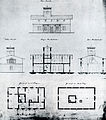

Schinkel continued to design the buildings; they were carried out by Ludwig Persius , who was also able to work with his own designs from 1836. After Persius' death in 1845, Ferdinand von Arnim took over the role of the royal court architect. After his death in 1866, Prince Carl no longer employed a major architect for the buildings. Ernst Petzholtz , a successful master mason from Potsdam, was now active.

The gardens were initially designed by Lenné and executed by court gardener Friedrich Schojan until 1853, whom Hardenberg had already brought to Glienicke. From 1853–1896 August Gieseler, who had previously worked in Muskau, was the prince's court gardener. For the part of the Ufer-Höhenweg, Prince Carl called in the landscape painter August Wilhelm Ferdinand Schirmer . Prince Pückler also influenced the Glienicke gardens. In 1834 he dedicated his " Hints on Landscape Gardening " to Prince Carl , a book on garden design that became widely known in the following years and that Carl evidently consulted several times when designing the park.

Since the middle of the century, Prince Carl seems to have only designed the park according to his own taste, but was certainly advised by Lenné until his death in 1866. However, only insufficient information is available today about the details of the park's history, as almost all of Lenné's plans and the entire correspondence between Prince Carl and Lenné have been lost.

The park reached its final expansion at the beginning of the 1860s, the last renovations and new buildings were made in the early 1870s, half a century after the park was taken over. It showed that Prince Carl also followed fashions over time and reshaped previously designed things. In addition, he also fell into an excessive respect for lush trees, no longer applied the necessary pruning, so that lines of sight were already growing during the prince's lifetime. The middle of the 19th century is seen as the ideal phase of Glienicke Park today, when the plantings of the older western parts of the park were already fully developed and the park expansion areas in the east had undergone their basic design.

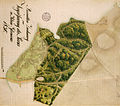

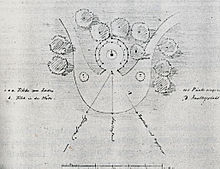

According to the few parking plans that have survived from Prince Carl's time, four planning phases can be highlighted:

- 1. A plan designed by Lenné in 1824 or 1825 and made by Schojan, which shows the original property, but has only been handed down as a black and white photo.

- 2. Two expansion plans drawn by Lenné in 1830 and 1831, which were not implemented, but which illustrate his intentions.

- 3. A map drawn by Gustav Meyer in 1845 after remeasurement for a publication on a scale of 1: 2000. This is the most accurate and detailed map of the property after the great eastward expansion. It is available in a second drawing on a scale of 1: 4,000, which should be the actual artwork.

- 4. A map from 1862 named after the lithographer “Kraatz Plan”, which has been handed down in color lithographs. It shows the park in its final dimensions, is very detailed, but not as precise as the Meyer plan. In return, however, it shows the palace complex with lion fountain and stibadium, the court gardener and machine house, casino and cloister courtyard as well as the hunting lodge with its outbuildings on four small special cards.

Glienicker Park became famous from the middle of the century. Both Gustav Meyer and Hermann Jäger felt compelled to write a section about Glienicker Park in their gardening books (see below), thereby classifying it among the most important parks of all. And Heinrich Wagener wrote in 1882: “ Klein-Glieneke, for more than fifty years the pilgrimage destination for thousands who want to build on an almost perfect union of art and nature, is one of the jewels of scenic beauty in the Brandenburg region. "

The first scientific record of the building and art inventory of the Glienicker Park took place in the course of the creation of the inventory of the architectural and art monuments of the province of Brandenburg. The art historian Rudolf Bergau traveled throughout the province from 1879–1881, which the government builder A. Körner, who finally wrote the Glienicke article, added in 1882 while Bergau was ill. Bergau and / or Körner received their information about Glienicke from Prince Carl or at least from people from the royal court during Prince Carl's lifetime. The very extensive lists of the equipment of the garden courtyard, curiosity , casino and monastery courtyard are listed below in the notes. They describe the holdings shortly before Prince Carl's death and show that the collections had grown to such an extent that the original residential use of the rooms in the curiosity and in the casino was no longer possible.

The park after the death of Prince Carl

In his will, Prince Carl stipulated that the heirs had to raise 30,000 marks annually for the maintenance of the park. His son Prince Friedrich Karl died just two years after his father in 1885. The twenty-year-old grandson Prince Friedrich Leopold thus became the heir of the facilities, with which he apparently had not developed a particularly emotional relationship. The parks were no longer accessible to interested visitors. The lack of maintenance led to the loss of the parking spaces. For example, Prince Carl created groups of bushes from hornbeam that always had to be kept in cut. They now grew up to trees that blocked the sight lines.

In 1889, Prince Friedrich Leopold had the hunting lodge and its outbuildings completely rebuilt in southern German early baroque styles by master builder Albert Geyer . The assembly was representative and had a certain courtesy, especially due to the onion dome, but was just as stylistically isolated in the Potsdam cultural landscape as was the neo-baroque palace that Prince Carl had built here from 1859 for his son Prince Friedrich Karl.

After the humanly difficult prince fell out with his family and his cousin Kaiser Wilhelm II , he retired entirely to the hunting lodge. In 1911 he had the hunting lodge garden moved with a martial-looking concrete wall, of which a small section at the Kurfürstentor is still preserved today. The Schinkelbau, now known as the “Old Castle”, the park and the outbuildings were hardly looked after. Since the park was no longer open to the public, it disappeared from the public consciousness.

The fall of the Hohenzollern monarchy in 1918 and the later transfer of the castles to state administration did not affect Glienicke. As the property of a branch line of the formerly ruling royal family, it remained the property of the prince. However, he moved to the Villa Favorita in Lugano , which meant that the Glienicke grounds were even less well maintained. On October 1, 1920, the Gutsviertel Klein-Glienicke-Forst, which bordered the Potsdam city area, was incorporated into Greater Berlin , where it became part of the 10th administrative district “Zehlendorf” .

Prince Friedrich Leopold took numerous works of art from the “Old Castle” and the Pleasureground to Switzerland, where he sold them to repay debts. At the beginning of 1931 he had the remaining Glienick art holdings auctioned at a major auction in Berlin. The associated catalog is accordingly an important source for furnishing buildings and gardens.

He had already started selling parts of the park beforehand. The Prussian state bought the Böttcherbergpark in 1924. From 1928 a development plan for the Böttcherberg has been preserved in a very simple parceling out, but luckily it was not implemented. The once famous park was in danger of being destroyed in these years. According to Julier, the prince intended to sell the entire park extension area from 1841 as building land, which the Prussian state forbade him. The state demanded permanent preservation as a park, whereupon the prince filed claims for damages against the state. Due to the prince's death, the litigation was not pursued by the princely family.

In a certain way, however, the prince's heart hung on Glienicke, because there he had on the occasion of the death of his son Prince Friedrich Karl jun. , who died in the war in 1917, had a family burial site built. He had chosen the height above the Großer Wiesengrund, west of the Roman Bank, as the place. A circular depression was excavated in which the graves were arranged radially along the lining walls. Prince Friedrich Leopold found his final resting place here in 1931, his wife († 1959), who was completely estranged from him , refused to be buried next to him. The burial site, which is still occupied today, does not impair the historical park in its simplicity, but it has not enriched it either.

In 1934/35 the city of Berlin acquired the Glienicker facilities with the exception of the palace and the pleasure ground . Previously, at the instigation of State Commissioner Julius Lippert, pressure had been exerted on the guardian of the minor heir to sell and the purchase price had been made available by confiscating the property of Herbert Gutmann . Only the roughly triangular area between the gardener's house, farm yard and rotunda remained for the princely family. The park has now been made accessible to the public and was given the name "Volkspark Glienicke", with which Lippert wanted to make it clear that, in a sense, he had given the people a gift. The reference to National Socialist politics was underlined by the fact that the opening ceremony was held on the occasion of the Fuehrer's birthday .

However, Lippert reserved the Jägerhof and its surroundings for hunted pleasure . The interior of the Jägerhof was converted into a modern hunting lodge and expanded to match the style. Above the Jägerhof, the large hunting parachute was removed and a bastion with historical guns was built in its place , from which Lippert could, as it were, enjoy a view of the general . With the exception of the so-called hermitage, all historical wooden architecture in the park has been removed and the billet bridges have been replaced with modern squared timber structures. Apparently damaged was repaired . The Devil's Bridge was, so to speak, completed and thus robbed of its sentimental character. Cuts were also made in the path system.

When the art historian Johannes Sievers was working on the volume “Buildings for Prince Karl” published in 1942 in the series “Karl Friedrich Schinkel's Lifetime Achievement” in the 1930s , he found a largely looted complex in Glienicke. He recognized the total work of art and also documented the works of the architects and artists who worked here after Schinkel. Sievers' observations are the first fundamental scientific work on Glienicke and are an important source today, as extensive destruction began in the following.

After Heinrich Sahm's resignation, Julius Lippert also took over the office of Lord Mayor of Berlin under the title of City President . He chose Glienicke as the future official residence or official residence. In addition, the south-western part of the park should serve as a garden, which still belonged to the princely family. This part was acquired by the city of Berlin in 1938/39. Until then , Prince Friedrich Leopold junior, who was still living in the Schinkel Castle . then led the remaining works of art to Gut Imlau in the Salzburger Land, where he retired.

The castle should now by Dietrich Müller-Stüler be expanded to the town Presidential official residence, for which it did not, probably because Lippert due to an intrigue Albert Speer lost his position in July 1940th It is no longer possible to understand exactly what construction work was carried out. Destructive construction work in those years saw the demolition of half of the greenhouses, which had to give way to a tennis court.

The artistic value of the park was completely misunderstood at the time. During the expansion of Berlin-Potsdamer Chaussee in the course of Reichsstrasse 1 , large amounts of overburden were produced. For the sake of simplicity, a considerable part of this earth was dumped into the hunting lodge garden and the pleasure ground. The artistically designed park areas turned into banal green spaces on which new paths connected the remaining buildings over the shortest possible distance. In addition, the Berlin-Potsdamer Chaussee between the parks was extended from 11 to 13 meters wide to 29 meters at the expense of the Jagdschlossgarten.

During the war, the castle served as a hospital. At the end of the war, German units finally gathered on the island of Wannsee and blew up all bridges in order to fight a senseless final battle with the Red Army, which had already advanced to Zehlendorf. This caused considerable damage to the woods on the shore zone, and the casino was destroyed to the ground. All other buildings also received significant damage from artillery fighting. At the beginning of the Soviet occupation, it was used briefly by the military, with the upper floor of the Schinkelschloss being used as a horse stable and the rooms suffering further damage. The Glienicke buildings were then looted by metal thieves and further destroyed by vandalism.

Restoration of the Glienicke facilities

After mental games in the early post-war period to develop Glienicker Park into an important West Berlin sports facility on the border with the Soviet Zone / GDR and thus to completely destroy it, a rethink began to preserve the work of Schinkel and his students. The castle was outwardly substantially restored by Schinkel intention 1950-1952, was disturbed by which the garden court in his view, however, the relations Hofdamenflügel gutted and extended. The large horse stable in the cavalier wing was divided into small rooms. The castle was now used as a recreational home for athletes. In 1952 the park was placed under landscape protection, an important step towards permanent conservation.

The outbuildings were successively repaired. The casino stood for years without a roof and was then rebuilt in 1963 using the foundation walls. Architectural details of the buildings that were not rebuilt were stored in a lapidarium (lapis = Latin for the stone) in the base of the water tower. The park area, which had belonged to the princely family until 1939, was, as in the pre-war period, not open to the public and therefore not in the public eye.

On January 1, 1966, the Pleasure Grounds were placed under the administration of the State Palaces and Gardens of Berlin . While locks Director Margarete Kühn fully committed to the reconstruction of the Charlottenburg Palace was used, straightened her successor (1969) in the Official Martin Sperlich increasingly his gaze on the Glienicke plants that he did not as garden art and as a collection of Schinkel's buildings in the countryside knew . In the surveying engineer Michael Seiler he found the specialist interested in Glienicke Park, who created the scientific basis for restoring the garden and who finally presented his dissertation in 1986 on the entire history of Glienicke gardens.

As early as 1978, a department for garden monument maintenance was set up at the Senator for Building and Housing. The garden architect and historian Klaus von Krosigk took over the management and built up the department for a functional specialist authority. The thus institutionally developed Berlin garden monument preservation placed its second focus on the Glienicker facilities in addition to the Berlin zoo . In the following, spectacular garden archaeological excavations took place in the area of the Pleasureground and in the hunting lodge garden . Based on the excavation results, which were combined with the critical evaluation of the historical park plans, an authentic restoration could be carried out, which received international attention in specialist circles.

The Schinkel year 1981 brought a further boost in public interest and public funding, so that the buildings could be supplemented in important details and a reconstruction of the orangery could be carried out. In 1982 the official entry was made as a monument or garden monument for the entire complex. While the Berlin Wall caused damage to the Glienick facilities through the demolition of Swiss houses and the restoration, it indirectly enabled the Berlin-Potsdamer Chaussee to be dismantled to almost its original dimensions. This would hardly have been possible after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

In the meantime, Sperlich had made contact with the partner of Prince Friedrich Leopold Jr., Friedrich Baron Cerrini de Montevarchi, who died in 1959. In his will he bequeathed the Glienicke works of art brought to Imlau to the palace administration, including the “ Journal about Glienicke ”, an invaluable source . Cerrini died in 1985; for example, Sperlich's successor as castle director Jürgen Julier was able to open the castle, which had been used by the folk high school until then , as a castle museum for the 750th anniversary of Berlin in 1987 . At the same time, an exhibition on this park area and the recently restored gardens could be visited for the first time in the outbuildings of the hunting lodge that were newly occupied by the Heimvolkshochschule. Shortly beforehand, an exhibition on the Glienicke hunting lodge had been prepared for the event in the Haus am Waldsee .

After the unification of the German states , the palace and park complexes of the Potsdam cultural landscape could be included in the UNESCO World Heritage List on January 1, 1991 , which had already been requested but was not possible due to the border barriers. When the Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg (SPSG) was established in 1995 , Glienicke was permanently designated as the palace museum and so far the only court gardening museum. In 2000, the SPSG was able to take over the gardens of the Pleasureground and the castle area, which had been managed by the district office until then , but the park remained with the district office. Since 1992, the park has also been part of the EU bird sanctuary Westlicher Düppeler Forst .

Prince Carl and his collections

Prince Carl was the middle of the royal couple's seven children. Queen Luise rated Carl, born in 1801, as her most beautiful child. The sculptor Christian Rauch described him in 1815 as “ a very amiable fellow, handsome and lively, with a lot of masculine grace. “Up until his thirties, Carl was a sporty, active and attractive man, but his face quickly withered.

As a child, Carl is portrayed as always in a good mood and funny. Exuberance, courage in “Toberey” with his older brothers, a desire for jokes and humor seem to have been Carl's striking characteristics. His traditional letters, too, testify to wit and a desire for occasional silliness. However, this found its limit in class differences. He made it clear to his teachers accordingly that it was not they but he who had to give instructions. From the middle of the century, Carl's humor seems to have increasingly waned in the face of political developments. Politically, Prince Carl never understood jokes.

At the time of his mother's death , he was eight years old and was raised for ten years by Heinrich Menu von Minutoli , who had a strong influence on the boy. Minutoli particularly promoted Carl's interest in antiquities and antiques and helped him to get a good general education. He later brokered the acquisition of the famous Goslarer Kaiserstuhl for Prince Carl .

Prince Carl spent most of his childhood on the ground floor of the Prinzessinnenpalais in Berlin . The prince laid out the first horticultural beds and plantings in the walled garden facing the opera house . As a child, he gained his first experience with gardening and expanded the knowledge he acquired during his youth.

A striking trait of Prince Carl's personality was his passion for collecting, which he had developed with minerals as a child. The prince later collected ancient art and the classicist sculpture of his time, Byzantine and medieval art, Renaissance and Baroque art, East Asian art, weapons, guns and hunting gear, carriages and boats, yes, Seiler pointed out that even the countless erratic boulders with which Carl decorated his park, also represented a kind of collection, especially since he brought them from Westphalia.

The young Prince Carl had a pronounced self-confidence that was paired with a pronounced sense of class and loved socializing at an early age. For example, when he was fourteen, he invited Schinkel to dinner twenty years his senior and discussed his project for a national cathedral with him. At a young age, Carl had such an engaging character that he immediately won the affection of Prince Pückler at the Aachen Congress in 1818 . But a mostly purpose-related friendliness has been handed down to Carl's social interaction. There are only indications in the family correspondence on the prince's border legal activities. The verdict on Carl in a much-quoted sentence that Friedrich Wilhelm IV. Coined about the four brothers in 1858 is particularly charmless: " If we had been born the sons of a simple civil servant, I would have become an architect, Wilhelm Sergeant, Carl would have been sent to prison come and Albrecht became a drinker. "

As the king's third-born son, Carl's professional function was that of a senior military man, with which he did not identify as strongly as his older brother Wilhelm . In contrast to this, who had the reputation of a liberal in the family , Carl was the political confidante of his eldest brother, the later King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. Both were united in a restorative policy with which all democratic developments should be prevented. Accordingly, Carl's political model was the court of St. Petersburg , where his sister Charlotte had resided since 1817. She first invited Carl to St. Petersburg in 1820, where he found a court and government that he would have wished for Prussia. There he was also able to study modern landscape gardens, with the Pavlovsk park particularly fascinating him.

Carl shared a penchant for everything English with Charlotte. Since Prince Carl, in addition to his park mania and his love of hunting, had a penchant for fashionable news and had developed a particularly pronounced Anglophilia in these passions , his nickname "Sir Charles Glienicke" developed in the royal family at that time, with which he occasionally signed letters . But Carl and Charlotte were in agreement in their rejection of British politics. Carl never traveled to England and only knew the famous English landscape gardens from publications. In 1825 Carl's brother-in-law Nikolai unexpectedly became Tsar, with which Charlotte, as Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna, was able to make her family happy with truly imperial gifts. Carl also received valuable gifts, some of which he was able to block in the Glienicker facilities. St. Petersburg remained Carl's favorite travel destination until Charlotte's death in 1860.

On September 15, 1822, the king, accompanied by Prince Wilhelm and the twenty-one-year-old Prince Carl, began a trip to Italy, which also included a visit to the Verona Congress , but otherwise took place incognito. The crown prince was denied the coveted trip. This was Carl's first big trip and shaped him accordingly. It led him from Xanthen on the Lower Rhine up the entire course of the river and on through Switzerland , where he had his first high mountain experience.

At the congress in Verona, Carl must inevitably have met State Chancellor von Hardenberg, the head of the Prussian delegation, not knowing that he would die unexpectedly on November 26th, thereby enabling the prince to acquire Glienicke. The king's entourage also included Alexander von Humboldt , who occasionally acted as cicerone for the royal rulers. The journey continued via Venice to Rome and on to Naples , where they spent four weeks in mild winter weather and visited the excavation sites of Pompeii and Herculaneum .

The return journey was also rich in cultural experiences and led via Florence , Pisa , Genoa , Milan , Trieste and then again over the Alps to Innsbruck , Salzburg , Prague , Dresden , so that on February 1, 1823, they returned to Berlin . This trip probably influenced Carl more than he was aware. In a slightly arrogant tone, faced with the difficulties of the journey through the technically backward country, he wrote to his father the remarkable sentence that, in order not to lose one's liking for Italy , one should not look at the country for oneself, but study it in pictures and books. And with the Pleasureground and its buildings, Carl created a piece of Italy from second hand, so to speak . It was not until the early 1840s that Carl made a few trips to Italy again, now accompanied by the family. These trips were also used to contact art dealers and purchase works of art.

At the end of 1826, Prince Carl got engaged to Princess Marie of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach . The Ordenspalais in Berlin was made available to him for the purpose of founding a household, which was completely redesigned in the following two years according to Schinkel's plans and moved into at Christmas 1828. Expansion and renovation work on the castle has now also been accelerated in Glienicke . After the May 26, 1827 Schloss Charlottenburg celebrated wedding Marie was on June 5 by the king to the strains of military music as a new (co-) owner of Glienicke introduced . To what extent the princess, who had no influence whatsoever on the Glienicke gardens, at least helped to determine the interior design of the palace , which was completed in 1827 , is unknown.

Although the marriage between Princess Marie and Prince Carl was a love affair, both relationships were short-lived. The marriage lasted nearly fifty years until Marie's death, but both spouses lived a life of their own long before the children's adolescence . The princess Marie, dissatisfied with this situation, was soon given the not particularly sympathetic nickname " Mother Wistfulness " in the royal family . Only in old age did the two find each other again.

Hunting was a very great passion of the prince . He pursued this passion all his life and reintroduced parforce hunting in Prussia . Hunting grounds in Glienicke were therefore no decoration. Prince Carl's historical collection of hunting gear was not in Glienicke, but in the city palace and is now in the Grunewald hunting lodge . It is still unknown where and how the prince presented hunting trophies in Glienicke. It can be assumed that he did this in an effective way and not arranged it en masse on the walls like his son in the Dreilinden hunting lodge .

Prince Carl made a special quirk with a court carrot . It was a black-skinned court employee who was named "Achmed" and who, in an exotic-looking oriental costume, served as a distinguishing mark for the royal court. Carl was the only Prussian prince who resorted to this 18th century fashion. When the first was replaced by a new Moor , this was again given the name "Achmed", which does not necessarily indicate any great princely interest in his personality.

Prince Carl had always had a keen interest in architecture, albeit without designing himself like his older brother Friedrich Wilhelm. He studied architecture on his travels and developed the building requirements in discussions with his architects. At the cloister courtyard, Carl said that it was created according to his statements without even a draft sketch. The defining architectural artist in Glienicke, however, was Schinkel, whose career and work development Carl followed from his youth. The prince had a respectful relationship with Schinkel, while with Persius, v. Arnim and Petzholtz - as far as journal entries and correspondence show - a more submissive deal was maintained.

“ Schinkel did not remain in such a personal relationship with any of his creations, long after his actual work was mainly completed there, as with Glienicke, who in a certain sense was never finished due to the expansion of his collections, which is why his advice is always welcome appeared. That this was the case was certainly not at least due to the personality of the princely builder, who was filled with genuine enthusiasm for art and who had been able to put the best men who were active in the field of art in Berlin at the service of his work. Glienicke emerged from this collaboration between builders and artists, the only one of its kind as the summer residence of a princely collector and art lover during the 19th century . "

But since Prince Carl was interested in architecture, he did not persist in Schinkel's architectural language after Schinkel's death. Rather, he turned to new architectural fashions, such as the neo-renaissance. The new baroque style of the hunting lodge building from 1859 is very remarkable in this regard. The fact that the palace designed by Schinkel and the outbuildings remained almost unchanged from the outside shows the respect that Prince Carl had for Schinkel's work.

Carl's extremely intensive park designs and his passion for collecting were on the one hand a balance to his professional obligations, on the other hand they were a compensation for his own political insignificance. Prince Carl's art collections and their installation in the park were certainly also an attempt to enhance their own temporally limited and historically insignificant life span by placing them in a larger, more or less timeless setting in Glienicke.

Helmut Börsch-Supan pointed out in 1987 that Carl's inclination was the antiquarian and not the artistic. On closer inspection, there is no actual art collection. Paintings were acquired as an opportunity, not on schedule. In addition, the purchased paintings were mostly common goods , while the contemporary art, which was important at the time, such as paintings by Caspar David Friedrich , Karl Blechen or Adolph von Menzel, was apparently completely disregarded. This is remarkable in view of the purchases made by the king and crown prince for the palaces and the museum in Berlin, which opened in 1830 .

Prince Carl also did not acquire any modern sculptures, rather repetitions of sculptures that had already been created for other locations were set up. For example, the figures of Tieck for the tea room in the Berlin Palace or Dankberg's boy for the frog fountain in Sanssouci. Here the collector apparently lacked a deeper understanding of art. Perhaps this corresponds to Carl's great musicality. The prince liked to talk to her. However, there are only indications of extremely fashionable music, such as by Lanner , Donizetti or Strauss . The portrait of Prince Carl, so lovingly portrayed by his biographer Countess Rothkirch in 1982, as a " connoisseur and protector of the beautiful " certainly only affects part of his personality. Nevertheless, with the creation of the Klein-Glienicke park, Prince Carl wrote a small chapter in European garden history.

Use of the facility at the time of Prince Carl (1824–1883)

You are well informed about the use of the park by the Princely Lords thanks to the “ Journal about Glienicke ”, which the Court Marshal (1824–1850 Kurd von Schöning , 1850–1867 Franz von Lucchesini) had to keep daily. This diary not only recorded the daily activities of the princely couple (the children were employed by educators), but also kept a record of all table settings for the accounting of the princely apanage . Accordingly, Prince Carl's social interaction has been handed down in detail. As a result, it is known that breakfast was often eaten in the garden, while dinner was generally served in the castle . The tea (the evening meal) was taken - if the weather allowed it - in a different place in the garden or park every evening. The large number of tea places is explained by the need to experience the park every day late in the afternoon or in the evening from as different perspectives as possible. A large number of servants made this luxury possible.

While the Pleasureground was only explored on foot, the park was largely visited by carriage. Princess Marie almost only made trips. Guests were also shown the park by means of carriage rides. The trips were supplemented by promenades at various points, for example to see the waterfall on the Devil's Bridge. Prince Carl, on the other hand, was mostly on horseback in the park. No Potsdam park owner devoted so much to garden design. Sometimes he inspected the park work every day so that he could always incorporate new ideas about the design when implementing the plans, and occasionally even lend a hand himself.

Initially, the park was not accessible to interested strangers. A historical plaque from the main gate that still existed in Glienicke in 1939 indicated that Carl had forbidden public access to the property on May 7, 1824 . Later, probably only after the park was expanded in 1840 and the entire property was fenced in, the park could be viewed on foot by interested visitors after reporting to one of the gatehouses. It was up to the guards to decide who they let in. In the absence of the princely family, recognizable by the non-hoisted flag on the castle , the pleasure ground , parts of the castle and the outbuildings could also be viewed after reporting to the castellan ( inspector ) . The princely family now saw itself as a style-forming element for the common people . In the end, the garden and park seem to have been practically open to the public. In 1882, at least, Wagener reports no access restrictions, recommends his readers to “see for yourself” what he describes and reports that Glienicke is the “ pilgrimage destination for thousands ” who wanted to build on the connection between art and nature.

The outbuildings of the park (gatehouses, court gardeners' and machine houses, sailors' house, hunter's yard, sub-foresters' houses) all had an enclosed commercial property and were not accessible to strangers. The historical fencing of the commercial properties consisted of wooden picket fences . The park boundaries were also made up of continuous, finely proportioned estaquets based on Persius' design, which prevented unintentional penetration by humans and animals.

The first of May marked the beginning of the summer season for the princely couple, when Glienicke was bought. As soon as the prince's court had moved into the castle , the prince's flag was hoisted and, in the event of intermittent absences, it was brought down again. Important holidays in Glienicke were after the couple's wedding anniversary on May 26th, the birthday of the prince (June 29th), that of his sister Charlotte (July 13th) and her husband Tsar Nikolai I (July 6th) and that of his father King Friedrich Wilhelm III. (3rd August). On public holidays, the princely miniature fleet cruised on the Jungfernsee, the masts (frigate dummy) and the castle were flagged, salutes were shot and, at dusk, flames were lit in the shells on the buildings. Illuminations with “ Bengali flames ” are also mentioned later . Such was also done when guests of state paid their respects to the prince or when the king and high-ranking guests went by ship to the Pfaueninsel or returned from there. Then the waterfall was "released".

Every year on October 18, the anniversary of the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig was celebrated with a bonfire on the Böttcherberg. In the run-up to the annual move to the Berlin City Palace, an extensive inspection of the park from the carriage with the court gardener, the court marshal and the inspector took place at the end of October, on which the autumn plantings to be carried out during the absence were ordered. The season in Glienicke ended with the Hubertus hunt on November 3rd. In the winter half-year, trips to Glienicke were only occasionally made and combined with the coordination of the park design.

During state visits it was protocol-wise to pay the attendance to Prince Carl, Glienicke was accordingly well known among the European nobility. Whether in the early days of Carl's possession the Queen of the Netherlands or in later years the Shah of Persia, many crowned heads visited Glienicke. In addition to the Tsar couple, who were closely related to Prince Carl, the visit by Queen Victoria was the highest-ranking visit that Glienicker Park received in this regard. The Journal noted this visit on August 14, 1858 quite succinctly: “ Around 6 o'clock, Her Majesty made the Queen of England, with her husband Prince Albert , the Prince of Prussia along with the Princess and Prince Fried. Wilh. with wife visit and a promenade through the garden, castle, curiosity, casino and cloister courtyard. "

Historical descriptions of Glienicke Park from the time of Prince Carl can be found in the early tourist literature by Samuel Heinrich Spiker (1833), Anonymos (1839), Anonymos (1846), Ludwig Rellstab (1854), August Kopisch (1854), and Karl Ludwig Häberlin (1855) and Robert Springer (1878). In 1882 the regional historian Heinrich Wagener described the history and shape of the Glienicke plants in great detail. Helmuth von Moltke sent a short but characteristic description (see below) to his bride when he was adjutant in Glienicke in 1841.

Historical publications of the buildings can be found in Schinkel's “ Collection of Architectural Designs ” ( castle and casino ), in the “ Architectural Album ” (rotunda, court gardener and machine house, greenhouses, sailor house, Villa Schöningen and Stibadium) and in the “ Architectural Sketchbook ” (Obertor- and wildlife park gatekeeper house, main gate gatekeeper house, Griebnitztor gatekeeper house, Unterforsterei Klein-Glienicke, canary bird house, hunting lodges and Swiss houses). Remarkably, there are no publications by Löwenfontäne, Neugierde , Jägerhof and the Klosterhof. The published park plans are a less attractive lithograph from around 1845 on a scale of 1: 5,000 and a very attractive color lithograph from around 1862 on a scale of 1: 2,500, the so-called Kraatz plan.

Glienicker Park has never been systematically depicted in images, such as a series of lithographed watercolors by Carl Graeb created for Babelsberger Park . Strangely enough, Prince Carl seems to have had little interest here. In 1843 and 1854 he put together a portfolio of already existing prints for the publication of his park, such as the sheets from the “Collection of Architectural Drafts”, the color lithographs from Haun to Schirmer and the unattractive lithographic park plan from 1845.

At the time of Prince Carl, only the pleasure ground has been documented photographically: the photographer Robert Scholz took a series of photos around 1875, perhaps on the occasion of the 50th anniversary celebration in 1874, showing the garden in a largely overgrown condition. There are no photos of the park at that time. When Johannes Sievers and his son Wolfgang documented the park and buildings in the 1930s, the wooden architecture had already disappeared and the park areas had become completely overgrown.

Park structure and design since the last expansion

Humphry Repton , probably the most influential English landscape designer of his time, formulated the design principles of the classic English landscape garden at the end of the 18th century. Accordingly, the flower garden was created directly at the house, to which the pleasure ground , the house garden, was connected. Both were separated from the actual park by fences, walls or invisible fences (quasi invisible fences or ditches), since livestock and game roamed freely in the park, which would have bitten the flowers and ornamental shrubs in the garden.

In Glienicke, the flower garden has a special form of the garden courtyard. The pleasure ground extends between the castle and Glienicke bridge. The park is divided into the part of the Großer Wiesengrund, which today occupies about the middle of the facility, to the west is the part of the Ufer-Höhenweg, which continues in the north in the Jägerhof area. In the northeast are the steep slopes of a mountain park called the "Carpathians". To the south of this and to the east of the Großer Wiesengrund there is a section dominated by valleys with a woody character. South of Berlin-Potsdamer Chaussee are the Böttcherberg-Park with the framing Schweizerhaus area and the Jagdschlossgarten. The naming of most parts of the park is historical. Only the Ufer-Höhenweg, the large Wiesengrund, the Jägerhof-Partie and the Waldtäler-Partie are auxiliary terms, as it has not been passed down how the princely lords called these parts.

A characteristic of Lennésch park design are the very numerous and seemingly surprising lines of sight both within the park and into the Potsdam cultural landscape. The constant interlocking of meadow spaces to open up a maximum of visual relationships is typical of Lenné's garden art. Figural beds, lively ponds and mountainous park areas are typical of Prince Pückler's garden art. Prince Carl combined both in Glienicke, with the western parts of the park clearly showing Lenné's handwriting.

In the 19th century, the Glienicker Park was opened up via the so-called Drive , which begins at the Mitteltor (now an inconspicuous staircase access on Königstraße) . So the visitor first drove past the large boulder with the purchase date May 1, 1824 and the Großer Wiesengrund. He then passed the castle pond and the farm yard and finally reached the open side of the garden courtyard, through which he entered the castle .

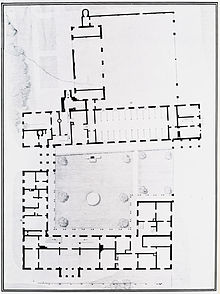

The garden courtyard

The garden courtyard is enclosed in a U-shape in the south by the palace and the court ladies' wing, and in the north it is bordered by the cavalier wing. It only opens to the east, which has been restricted since the court ladies' wing was extended in 1952. In the past, the view from the courtyard to the east was directed across the castle pond to the Großer Wiesengrund, suggesting a large expanse of the park. Since the view of the meadow has not yet been completely cleared, this is currently difficult to understand.

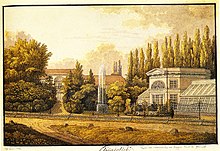

The courtyard was turned into the actual flower garden of Glienicke. Five round and two kidney-shaped cake beds, which had a pergola with a surrounding pergola as well as potted and potted plants, or they were decorated with rich flowers. Two water features were a sonic attraction. The ancient reliefs or fragments, which were gradually acquired at the time and finally even more numerous than today, offered an almost inexhaustible level of study.

In front of the hedge on the cavalier wing is a fountain with a crowning cast by the Ildefonso group as a quote from a corresponding facility in Weimar , the home of the prince's wife. Schinkel designed decorative terracotta tubs for laurel or orange trees on the steps to the side of the fountain. On the garden courtyard depiction by Schirmer there are strangely lined up small clay pots. Potted plants are placed in front of the hedge, which respond rhythmically to the pillars of the pergola. The center of the garden courtyard is marked by a fountain basin in which a Renaissance bowl fountain from 1562 had been located since at least 1837, which was later sold by Prince Carl's heirs.

The garden courtyard is, so to speak, the heart of the Glienicker Park. Schinkel clarifies this in the explanation of the publication in the “Collection of Architectural Designs”: “ The floor plan shows the disposition of the whole, where a courtyard, surrounded by castles and stables, arranged like a garden, surrounded by beautiful arcades constructed of iron, with fountains and Decorated bronze statues form a main part of the apartment, which, in contrast to the view of this interior, secrets of the courtyard, directs its windows to the distant view of the beautiful area and creates double enjoyment. "

Driveway

Of all Potsdam summer residences, Glienicke has the most unusual development. The castle was not accessed via an external facade, but through the garden pergola, which led to the hidden house entrance. After Schinkel's renovation, access to this pergola was a simple pillar construction that was difficult to identify as a castle entrance. You drove up to this pillar in a carriage and covered the rest of the way on foot. In the publication in his “Collection of Architectural Designs”, Schinkel depicted a front door right next to the pergola entrance, but this was not implemented because it would have led to confusion among strangers regarding the correct access.

Strangely enough, the actual focal point for those approaching is not on the castle , but on the cavalier wing, which protrudes far beyond the garden courtyard to the east, as Schinkel extended the existing building in this direction. Here is the vine arbor (see below) and above it, sculpture casts are set up in front of a wall field in a bright turquoise color for the long-distance effect. The "Felicitas Publica" from the Munich Max Joseph monument to Christian Daniel Rauchs is flanked by the figures of Odysseus and Iphigenia from Friedrich Tieck's Berlin tea salon cycle . A zinc cast of the head of the then famous "Athena Hope" was attached to the corner.

In order to accentuate the access to the castle , the simple pillars on the pergola were replaced by the propylon (portal structure) that still exists today when the court ladies' wing was added . This consists of sandstone with decorative elements made of zinc art cast. It was crowned by a cast of the Achilles statuette from Friedrich Tieck's Berlin tea salon cycle.

To the side of the propylon (as on the Stibadium) there are angular, half-height sandstone walls with cast zinc vases and benches on which the princely family could expect the right of way for particularly prominent guests or less prominent guests to be welcomed by the princely couple. The complex is also distinguished by the small stone mosaic paving with the prince's intertwined C monogram. The propylon was architecturally free until the court ladies' wing was extended to the north in 1952. In Prince Carl's time, people walked through the propylon directly into the pergola.

Since the princely couple mainly stayed in the pergola on the daily passages to the carriage, the cavalier wing was the actual view side of the garden courtyard. Accordingly, particularly expressive spoils , such as theater masks ( personae ) , were built into the facade of the wing .

veranda

The pergola, known as the veranda in the 19th century , consisted of four wings on the east, west and south sides of the courtyard and was supplemented on the north side of the garden courtyard by a hedge path in front of the horse stable in the cavalier wing. In the first wing the bowl fountain of the garden courtyard was the focus, in the second the column-flanked entrance to the ladies' wing, in the third wing the chimney with mural and in the fourth wing the entrance to the cavalier wing in the adjutant's arbor is the last focal point.

There is no axial line of sight on the main entrance, which is just in front of the fireplace, it is exceptionally hidden and only emphasized by the size of the portal and the " SALVE " in the doorstep. The pergola is covered with Aristolochia macrophylla and Passiflora , which gives it an exotic, southern character. Schirmer's picture at least temporarily points to Lonicera branding.

The pergola was initially made of iron, had a painted wooden ceiling and cast iron floor panels. In 1863 it was replaced by a cast iron construction with sheet metal covering. The structure of the new pergola - erected at the same time as the hunting lodge was being converted - corresponded to the old one, but it was more delicate and decorated. It is possible that there were also various decorative parts made of artificial zinc. Nothing has been handed down about a colored version or possibly partial gilding of the construction. This pergola was removed after 1945 and replaced by a wooden structure with an unhistorical wired glass covering that was closer to the original pergola.

The section of the pergola to the west of the main entrance to the castle was to be glazed in a mobile manner and then served as an additional winter garden-like space. There was a marble fireplace with a mural "Pegasus washed and soaked by nymphs" above, which Julius Schoppe had painted in 1827 (neither of which survived).

Carl probably received the inspiration for the painting from Alois Hirt's "Picture Book for Mythology, Archeology and Art", published in 1805. There the illustration is commented: “ The painting taken from the tomb of the Nasons, where the three nymphs wash the winged horse, Pegasus, is no less graceful . Like the Nereids , the upper body of the three naiads is shown naked, which brings them closer to the formation of the gods of love and the graces. "

The tomb of the Nasonians on Via Flaminia outside Rome from around AD 160 had been published since the beginning of the 18th century and enjoyed a certain popularity in art circles. But what the reason for the winged horse of immortality - a descendant of Poseidon and Medusa - was Glienicke's at this point has not yet been explained. To the side of the chimney were benches set into the wall, the wooden seats of which rested on cast-iron console feet with a Schinkel stamp.

The garden courtyard was used to display the ancient reliefs that Carl had acquired through the art trade. The complex saw itself not as a castle, but as an Italian villa, during the construction of which one came across ancient finds. The mostly marble relief spoils were arranged in the plaster in a decorative rather than archaeological way in the back wall of the pergola. Many of the fragments were inserted only in the last decade of the prince's life. After the trip to Italy in 1874, 33 boxes with antiques arrived in Glienicke. The tablets that are still present indicate that Prince Friedrich Karl also brought some antiques with him as a souvenir, including a piece from Troy, which the engraver noted as “Troga” - apparently in an effort to obtain high German orthography. The spolia arrangements were changed by lengthening the court ladies' wing and removing its entrance portal. Glienicke's antiques that still existed after 1945 have been cataloged in a scientific catalog.

Vine arbor and adjutant peristyle

Vine arbor and adjutant peristyle are the architectural links between the garden courtyard and the pleasure ground or the park. At the right of way in front of the cavalier wing is the vine arbor , which is also covered with Vitis vinifera . On the back wall of the arbor there were benches painted with oil paint, the shape of which probably went back to Schinkel, but has not been preserved. Later, according to the shape around the middle of the century, three niches were chiselled into the back wall, which were provided with ornate frames in marble. Replicas of children's figures were displayed in them.

On the narrow eastern side of the cavalier wing, the entrance to the castellan's ( inspector's ) apartment is accentuated by a porch flanked by herms. Originally this portal only had a metal canopy. To the side of the portal there were benches designed by Persius according to Schinkel's instructions in 1831, which can be seen in the painting of the right of way with red hunters (see above) but are not preserved. In connection with the benches on the propylon, there were numerous seating options in the area of the castle entrance.

On the opposite side of the garden courtyard, the adjutant's peristyle with a terrace above mediates to the pleasure ground between the pergola and the cavalier wing staircase entrance. The architecture, made up of twelve pillars or pillar templates, was simply but incorrectly called peristyle by Schinkel , later the term “adjutant's arbor” is occasionally used, although the structure as such cannot be used because it primarily served as a covered passage for the servants between the kitchen on the ground floor of the cavalier wing and the castle .

The terrace above could only be reached via the two French doors of one of the two adjutants' rooms in the cavalier wing and was accordingly named “adjutants terrace”. From here you have a remarkably beautiful view of both the garden courtyard and the pleasure ground . Today the terrace has only temporary railings. The shape of the historical lattice corresponded to the lattice that Schinkel designed at the same time for the dome casing of the (Old) Museum in Berlin.

The terrace in front of the peristyle in the direction of the Pleasureground with small colored stone paving acted as the actual tea place . The Mercury Fountain is located here on the south wall and opposite it, under the Renaissance decorative arch, there was a neo-renaissance bench that was still stored in the lapidary. The figure of the standing Mercury is not an ancient marble sculpture, but rather a reworked French sculpture from the 18th century. Very close in a niche in the west facade of the castle , a modern copy of the Venus Italica by Antonio Canova continues the antique program.

Occasionally, the antiquities program was duplicated during the continuous development. In 1852 the employees of Glienicke gave the prince couple for their silver wedding anniversary - certainly as requested - a cast of the resting Mercury from Herculaneum , one of the most popular life-size bronze figures of Roman antiquity since the excavation in 1758. As a result, the garden courtyard was bordered on both sides by figures of that ancient god, who is therefore to be regarded as the patron saint of Glienicke. Mercury , the messenger of the gods , had an ambivalent character in antiquity: as the patron god of traffic, travelers and shepherds, but also merchants, art dealers and thieves as well as rhetoric, gymnastics and magic.

The pleasure ground

The Pleasureground , created from 1816 on, is an early work by Lenné and at the same time one of his masterpieces. The Pleasureground appears to have a natural model of the terrain, but was completely artificially and artistically modeled by Lenné. The previously existing flat Büdnerstelle and the four fruit and wine terraces to the north, to which the avenue plantings of Lindenau were connected, can no longer be seen.

As a house garden, there are water features, three-dimensional works of art and cake beds, as well as some beds in geometric shapes, which were probably influenced by Prince Pückler. Numerous, originally cast-iron water pipes run through the Pleasureground , which not only serve for the water features, but also for the intensive irrigation of the plantations.

The pleasure ground is separated from the park by buildings. A wire shed fence runs along Berlin-Potsdamer Chaussee, an invisible fence towards the Uferchaussee and the casino's lower pergola . The historical access was via the garden hall of the palace , the adjutant arbor, the little gate at the stibadium, the two gates of the casino pergola and the cloister courtyard. Today's access from the driveway is not historical.

Beds and container plants

In the garden courtyard and in the pleasure ground there are elliptical and round cake beds with terracotta palmettes that are characteristic of Glienicke . The originals of the border stones were found in the cellar of curiosity , so that a faithful restoration was possible. Ten basic types were found in numerous variations. The beds are walled underground, which enabled specific irrigation. In addition, the beds were filled with loose substrate, which enabled the plants - which were occasionally placed in pots - to be changed quickly after they had started to wither. The large number of beds required large quantities of flowering plants to be kept throughout the season. In the midst of these plantations, cannas sometimes add an exotic touch.

There were and still are some figurative or geometrically designed beds, which set an artificial accent in the landscaped Pleasureground . These were framed with Buxus and therefore required a lot of care. Such beds can be found in front of the west facade of the palace , in front of the terrace of the stibadium, at the casino (Artemisbeet) and in oak leaf form on the side of the lion fountain. Most striking is the lily bed, which is located directly below the windows of Carl's bedroom in the central projection of the west facade of the castle . As a heraldic sign, it points to Carl's younger sister Louise , who was married to Prince Friedrich of the Netherlands and was particularly involved with flower bulb consignments in Glienicke. According to the Kraatz plan of 1862, some of the simple cake beds had been expanded to form beautiful geometric beds in the later 19th century, for example in front of the lion fountain and on Curiosity .

There are terraces in front of the west and east sides of the castle . Here citrus trees have been placed in pots since Hardenberg's time. This orangery (citrus collection) was valuable at the time, which is also evident from the fact that Christian von Hardenberg-Reventlow had stipulated in the purchase agreement in 1824 that he could choose four small and four large orange trees and two lemon trees.

In the area of the garden courtyard and the palace terraces and probably also at the casino , additional, non-winter-hardy potted plants were set up during the summer season, and they were moved to the orangery building in the winter months . As far narrated, it was not about palm trees, but - in addition to citrus - to Mediterranean and exotic flowering plants such as plumbago , Agapanthus and the decorative shells and Aloe . What is also striking is the extensive lack of rose plantings, which are an important feature on Pfaueninsel and Babelsberg, for example.

Flower bed at the rotunda with palmette tongues and fritillary plants

Lion fountain

Since the castle did not have a base in the form of a basement, Schinkel planned a high terrace wall that would have visually set the building apart from the garden. With this plan he also published the building in his "Collection of Architectural Drafts". Carl, however, came up with the idea of a new fountain system, especially since the old cast iron fountain bowl from Hardenberg's time in front of the garden salon was too modest for him as a water feature and was used a second time at the casino . After a steam engine was purchased and installed, a large well system was planned from around 1836. In the planning, Carl included the two large Medici bronze lions that his sister Charlotte had given him for his 30th birthday in 1831. The lions were casts of two bronze lions on the Palace Bridge in St. Petersburg. Since the publication of Pushkin's poem "The Bronze Horseman" in 1833, the Petersburg Lions enjoyed a certain degree of popularity.

On October 23, 1837, a meeting between Prince Carl, Schinkel, Persius and Lenné took place in Glienicke “ about the basin and the fountain in front of the greenhouse [...] and how the bronze lions would be best placed. “Schinkel then designed the new fountain system and a new greenhouse. Persius completed the final artwork on November 19th. On it, the lion figures are still shown on rectangular bases. Schinkel designed the pedestals with columns later.

The greenhouse design envisaged a five-part system consisting of three gabled plastered buildings and two fully glazed greenhouses in between. Sievers found this design so remarkable that he paid tribute to it in detail and also published enlarged sections. He characterized the building as " elegant " and as " a [building] idea of great success ." But this building design was never realized. In its place, Persius built the stibadium in 1840.

The new system was built in the axis of the south facade of the castle and included the old quarry stone lining wall. A gently descending flight of stairs led to the fountain from the terrace, which led to a terrace path encircling the basin in a semicircle, probably colored asphalt. The latter was backed by a balustrade with vase and figure attachments. The four terracotta figures from around 1855 were allegories of trade, science, art and the military as the cornerstone of the state structure, which were probably also seasonal allegories. The latter allegory has been lost, the rest of the children's figures are fragmented and placed in the castle . Its creator was probably the Rauch student Alexander Gilli , who worked as a court sculptor for Glienicke.

The side of the complex is flanked by two high plinths made up of four bundled Doric columns each, on which the lions are placed in fully gilded mounts. The bases consist of cast zinc hollow bodies and sheets around a load-bearing iron frame. Like the reliefs on the pillars of the palace balcony, the details of the propylon and the stibadium, they were products of Moritz Geiß's zinc casting factory , which processed the inexpensive and very finely chiselable material propagated by Schinkel and Peter Beuth in the best quality. Such decorative frames can also be found at the casino , which were painted with paint, to which sand was added, so that the illusion of sandstone was created. On May 26, 1838, the Geiß company issued its invoice for the delivery and assembly of the zinc castings. This should have completed the system.

On June 2, 1838, the fountains jumped for the first time on the occasion of a visit by the Russian Tsar couple. This was a big event, as so far water fountains have only been operated by steam power in the Potsdam park landscape and in a modest setting in Charlottenhof and it would be six years before the fountains would also jump in Sanssouci.

The shape of the water feature of the Glienicker main fountain varied over time. First, a Triton figure blew a simple jet of water into the air. Later they switched to heron bush and bell shapes. The lion figures also spewed water jets, and a water veil was created by the overflow of the grooved pool edge.

The lion fountain became a kind of symbol of the Glienicker park, especially as it had the strongest effect in the direction of Berlin-Potsdamer Chaussee and was known to almost everyone. The view from the Chaussee is the most frequently depicted motif among the numerous Glienicke Park Vedutas. It is noteworthy that this not a way, but only a line of sight was shown, an axis that begins with the Tortenbeet and fountain basin and staircase to the central projection of the castle with the low over the balcony pulled down awning and flagged mast on the Belvedere - Essay leads.

In accordance with its structural structure, the lion fountain had to be repaired several times. After the Second World War, the facility was completely ruined. During the reconstruction carried out between 1960 and 1964, the aboveground components had to be largely renewed. Fifty years later, the facility again showed considerable structural defects. The renovation, which could no longer be postponed due to tree damage, was tackled in 2009. After the start of construction, there were more serious construction defects than previously recognizable. Nevertheless, thanks to sponsorship funds raised by the SPSG, the facility was inaugurated again in 2010.

Suspended staircase and small stone mosaic paving

At the side, parallel to the lion fountain, the staircase from the castle terrace leads to the lower garden area. It is a flat staircase under a simple, sloped iron mesh treillage according to a design by Persius. The sphinx figures set up at the foot of the stairs and the not precisely fitting steps still come from the early classicist greenhouse with garden salon , which Lindenau had built after 1796 instead of today's Stibadium.

In front of the eastern staircase of the lion fountain, one of the few remaining small stone mosaic pavements refers to the Theeplatz under the royal linden tree that was once next to it. The latter was one of the most impressive individual trees on the property that had to be felled in the 1980s. The now-old linden trees, on the other hand, which are now standing on the other side of the mosaic in a bizarre oblique shape, were young at the time.

Small stone mosaic pavement came into fashion in the mid-19th century. White, gray, red and black small stone blocks were laid in geometrically patterned, carpet-like coverings. In Glienicke, such pavements have been preserved in the propylon , around the casino , on the stairs of the Roman bank in the park, on the adjutant's arbor and on the lion fountain, but there were certainly considerably more that have been lost because of the delicate structure. For example, small stone paving is to be assumed for the sloping platforms of the staircase.

But not all the optically highlighted terraces were adorned with small stone paving stones. Asphalting became fashionable at the same time as the carpet-like paving. The asphalt, which was precious at the time, was colored and clearly imitated a stone slab cladding. Such asphalting has been verified in Glienicke for the terrace of the stibadium (see below) and the terrace path around the lion fountain. Due to the difficulty of repairing the asphalt, none has survived today. Today the surfaces are tiled with clay tiles.

Stibadium

The Stibadium was the main tea place of the Pleasureground with a grandiose view of Potsdam and the lion fountain at the time. The name is a quote from a description of the villa by Pliny the Elder. J. , who described a particularly attractive resting place as the Stibadium . The Glienicker Stibadium bears no resemblance to the architecture described by Pliny. The Glienicke lords did not use this name either, but spoke of the Roman Bank . The building was built in 1840 according to a design by Persius, who created a major work among his ornamental architecture and published it under the name Stibadium .

It is a half- Tholos architecture with a wooden half-conical roof, which is painted on the underside with a program of twelve gods. But since it is fourteen fields, are the classic twelve Olympian gods nor Bacchus and Amphitrite beige sets. A zinc cast kore designed by August Kiß originally served as a garden-side support . It was later replaced by a fully three-dimensional marble repetition of the "Felicitas Publica" (Public Welfare) from Christian Daniel Rauch's Munich Max Joseph Monument.