Cuba's economy

| Cuba | |

|---|---|

|

|

| currency |

Cuban Peso (CUP) Convertible Peso (CUC) |

| Conversion rate | 1 CUC = 25 CUP = $ 1 |

| Trade organizations |

WTO , ALBA |

| Key figures | |

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

78.694 billion US $ (2013) |

| GDP per capita | US $ 7,020 (2013) |

| GDP by economic sector |

Agriculture : 3.6% (2012) Industry : 19.02% (2012) Services : 77.38% (2012) |

| growth | −0.9% (2016) |

| inflation rate | 5.5% (2012) |

| Employed | 5.01 million (2011)

|

| Employed persons by economic sector |

Agriculture : 19.7% (2011) Industry : 17.1% (2011) Services : 63.2% (2011) |

| Activity rate | 62.5% (2011) |

| Unemployed | 164,300 (2011) |

| Unemployment rate | 3.8% (2012) |

| Foreign trade | |

| export | US $ 6.04 billion (2011) |

| Export goods | Services, Nickel, Pharmaceutical Products, Tobacco and Tobacco Products, Sugar and Sugar Confectionery, Medical and Optical Instruments |

| Export partner | Venezuela: 37.6% (2010) PR China : 14.7% (2010) Canada : 13.9% (2010) Netherlands : 7.8% (2010) Singapore : 4.0% (2010) |

| import | US $ 13.96 billion (2011) |

| Import goods | Mineral oils, fuels, machines, vehicles, electrotechnical goods, cereals, medical and optical instruments |

| Import partner | Venezuela: 40.4% (2010) PR China: 11.5% (2010) Spain: 7.4% (2010) Brazil: 4.2% (2010) USA : 3.9% (2010) |

| Foreign trade balance | US $ −7.92 billion (2011) |

| International direct investment (FDI) | US $ 86 million (2010) |

| public finances | |

| Public debt | 34.90% of GDP (2011) |

| Government revenue | CUP 63.7 billion (2011) |

| Government spending | CUP 67.5 billion (2011) |

| Budget balance | −3.8% (2011) |

The economy of Cuba is a largely from bureaucratic - authoritarian controlled state socialist planned economy . In the case of joint ventures between Cuban state-owned companies and foreign companies, the state always holds a majority of at least 51 percent. There is also a significant private sector in the form of small self-employed people and cooperatives in a regulated number of professions. Capital investments are restricted and require government approval. The Cuban government sets a large part of the prices and determines the goods that are available to the population through the heavily subsidized rationing system .

Economic history

Economic development up to independence

When Christopher Columbus discovered the island in 1492, around 200,000 natives , Ciboney and Taínos , lived there . The Ciboney lived mainly from fishing , while the Taínos mostly cultivated cassava ( yuca ), corn and tobacco . Around 50 years later, the indigenous population had been decimated to around 4,000 due to mass murder by the conquistadors and diseases brought in by them.

The Spaniards originally subjugated the island in search of gold and silver . Because of its favorable geostrategic location and the large natural bay that is easy to defend, the port of Havana became the hub of the Spanish conquest of America and was at that time the largest economic factor in Cuba.

Tobacco cultivation began to flourish in the 17th century and sugar cane cultivation began in the second half of the 18th century . For the first time the name "Pearl of the Caribbean" came up. This was thanks to a year-long occupation of Havana by Great Britain in 1762. The British forced the opening of Cuba to their own economic interests. For the first time around 4,000 slaves arrived and were used for field work. 750,000 more, mostly West African slaves, followed in the next hundred years, turning half the island into a single sugar cane plantation.

After the French Revolution and the ensuing slave uprising in Haiti, along with the country's independence, numerous French farmers came to Cuba who brought the necessary “know-how” and capital with them in order to help sugar production to increase further. As a result, sugar exports rose exponentially. While it was around 15,000 tons in 1790, it increased by 50 times by 1868. In 1837 the first railway line in Latin America was built along the sugar plantations , ahead of the motherland Spain, and by 1840 Cuba was the largest sugar exporter in the world.

The first riots against the Spanish crown broke out in the middle of the 19th century. The descendants of Spanish civil servants and landowners, the Creoles , who were born in Cuba , protested because of high taxes and duties for the motherland. There were also slave revolts, which initially had a unifying effect between the Creoles and the Spanish crown. The slave trade was forbidden in a treaty between Spain and Great Britain as early as 1817, but it didn't really come to a standstill until 1865 with the defeat of the southerners in the American Civil War . Around 150,000 Chinese contract workers were recruited to replace them , but the economic pressure to detach the Cuban colony from the Spanish motherland increased. The Creoles initially tried to persuade Spain to reform and to achieve greater autonomy, which did not lead to success.

Nevertheless, Cuba managed to catch up with the high-income countries of Latin America by 1870.

As early as 1823, shortly after they had bought Florida from the Spaniards under military pressure, the USA tried to acquire Cuba as well, but this was not crowned with success, despite the considerable sums offered at times. Economically, however, the influence of the United States grew considerably, which soon made it Cuba's most important trading partner. While motherland Spain only imported goods worth seven million pesos in 1890 , the export value to the USA was 61 million pesos.

From independence to revolution

Until it gained formal independence in 1902, Cuba was under US military administration. The international reorientation of trade and investment relations resulted in a phase of strong economic development for Cuba. The world market price for sugar rose to a record level by 1920 and its share of Cuban exports at that time was 92 percent. When the world market price for sugar collapsed shortly afterwards, US investors had another opportunity to buy cheap prices in Cuba. Between 1911 and 1924, US investment in Cuba increased sixfold. The economic dominance of the big neighbor in the north was shown, among other things, in the fact that in 1915 a good 83 percent of imports came from the USA.

The economic crisis meant a strengthening of the trade unions and the independence movement vis-à-vis US hegemony . In 1925 the first trade union confederation was formed from 128 individual unions with around 200,000 members.

President Gerardo Machado , elected in 1924, promised “honesty, roads and schools” and had the expressway known as Carretera Central built, which connects Havana with Santiago de Cuba . After the global economic crisis broke out in 1929 , this also caused unrest in Cuba due to the collapse in exports. Machado lost trust among the Cuban middle and upper classes as well as the United States and had to go into exile in 1933 .

During Fulgencio Batista's first presidency 1940–1944, the Cuban economy experienced an upswing against the backdrop of World War II . The price of sugar soared as major European and Asian producers fell away. Between 1940 and 1944, the value of Cuba's sugar exports doubled.

Even after the end of the Second World War, the price of sugar remained high, and Cuba's economic prospects were therefore favorable. However, the subsequent presidents could not capitalize on it. There was no economic diversification . The dependency on sugar exports remained high (48 percent of Cuban exports in 1948).

In the 1950s, Cuba was economically a modern state with a lively capital, Havana. In addition to the main source of income sugar, tourism flourished. At US $ 374, per capita income was the second highest in Latin America after Venezuela . It was twice the Latin American average, but only a fifth of the US average. The infrastructure was state-of-the-art. In 1957 there was one television for every 25 residents, one telephone for every 38 residents and one car for every 40 residents. The Cuban middle and upper classes had adopted the American way of life and consumption. In addition, Cuba was now well on the way to successfully diversifying its economy away from the sugar monoculture. Tourism was considered the second “Zafra” and there was significant industry of its own.

However, the governments from the mid-1940s onwards were considered extremely corrupt, which intensified during Batista's second term in office. Havana in particular was considered to be heavily infiltrated by the US mafia , whose influence continued to spread. US companies controlled a large part of the strategically important economic sectors. There was a large income gap: the 40 percent poorest contributed 6.5 percent to national income in 1953, the 10 percent richest 39 percent, with the Latin American average being over 50 percent. In the countryside in particular, there was bitter poverty. 49 percent of the working population only found paid work ten weeks a year or less. 82 percent of them were women.

1959 to 1970

After the Cuban Revolution in 1959 , Fidel Castro and Che Guevara agreed that key social reforms should be implemented quickly. According to Castro, the revolution is “neither capitalist nor communist. Because capitalism abandons people, communism with its totalitarian ideas sacrifices its rights. ”According to the first analyzes of the revolutionaries, there was a great dependence on sugar exports, which was thought to be achieved with rapid industrialization and diversification of agriculture. Che Guevara wanted to achieve annual growth rates of 20 percent.

However, the conversion of export-oriented agriculture to growing food for local needs failed. The coordination turned out to be insufficient. At the same time, sugar production was neglected, as a result of which the harvest fell by a total of 23 percent by 1963 and sugar production by as much as 40 percent. Early revolutionary Cuba was facing its first liquidity crisis . By rationing of consumer goods Cuba's new government first tried to continue cash for planned investments provide. This rationing system introduced in Cuba in 1962 with a rationing booklet called Libreta ("allocation booklet that entitles the holder to purchase rationed goods") accompanied the Cubans until 2012.

Relations with the United States deteriorated rapidly in mid-1960, with far-reaching consequences for the economy. US-owned oil refineries refused to process oil supplied from the Soviet Union, whereupon Castro had them nationalized . The US government cut Cuba's sugar purchase quota, Cuba expropriated other US companies, whereupon the US government completely cut the sugar quota. The Soviet Union agreed to completely take over the original sugar quota. In August 1960, all large US industrial and agricultural operations were expropriated. In October of the same year purely Cuban companies followed because they allegedly had sabotaged the revolution. On October 19, the US stopped all exports to Cuba, with the exception of medicines and food. However, these exceptions were later removed. A general trade embargo came into force, which has been in force since then, with additional tightening.

By the end of 1960, all of the larger commercial enterprises in industry, agriculture, trade and banking had been expropriated . Socialism, although not yet officially proclaimed, was about to become the dominant economy.

As a result of this expropriation policy, many members of the old middle and upper classes emigrated to the USA. Although this made it easier for the Cuban government to attract potential political opponents, the wave of emigration was associated with a considerable brain drain . It is true that the official government propaganda meant that these economists, technicians and engineers could "easily be replaced with revolutionary will and willingness to make sacrifices". The nickel mine in Moa, for example, was shut down for years due to a shortage of skilled workers.

From 1964 the Soviet Union granted trade concessions and fixed prices for Cuba's sugar, which is why the sugar industry was given a higher priority again. Suddenly the focus on sugar was no longer seen as the cause of historical dependencies, but on the contrary as an opportunity to generate a corresponding national income.

Wages were standardized. He was no longer dependent on the quality and quantity of the work done. The level of qualification also hardly played a role. Material incentives were, in the spirit of Che Guevara, “capitalist”. Rather, moral stimuli should be used as work incentives. At the same time, the range of free services was expanded. For example, local transport, electricity, electricity and telephone were free. The result was a sharp drop in labor productivity and a general worsening of the supply crisis. However, there was no general absence from work and total breakdowns. This so-called “historical wage” is considered by some economists to be the forerunner of the unconditional basic income .

In agriculture, attempts were made to breed high-performance cattle suitable for the tropics. To this end, attempts were made to cross the domestic Zebu cattle with the Holstein cattle imported from the Soviet Union . This attempt turned out to be a gigantic failure, which is still having a negative effect on Cuba's meat and milk production today.

In 1965, with the founding of the Communist Party of Cuba, a theoretical discussion began. There were two main opposing positions: on the one hand, the representatives of a central administration economy in its purest form, in which the whole country is viewed as a single factory. Money-commodity relationships shouldn't play a role. The second camp advocated partial autonomy for companies, wage incentives and economic accounting . Finally the representatives of the radical planned economy prevailed. As a result, by 1968 almost all of the private businesses still in existence, mostly craftsmen, were nationalized. The subsequent extensive use of labor and a lack of cost control led Cuba into another economic crisis in the late 1960s.

The so-called " Gran Zafra " (great sugar harvest) should bring improvement in 1970 . The Cuban government had set a record target of ten million tons for this year's sugar cane harvest. Despite the fact that the entire Cuban economy was geared to meet this goal, the actual harvest fell short of the target by 1.5 million tons. Although ultimately a bumper crop was achieved, even if the actual goal was missed, this actionism caused serious damage to the Cuban economy .

Phase of the Soviet economic model

The failure of the experimental phase of the 1960s, a kind of war communism that ended with the Gran Zafra, now led to the complete takeover of the Soviet economic model . The performance principle was partially introduced again. In 1972 Cuba joined the Council for Mutual Economic Aid (Comecon - also known as Comecon). Cuba had to say goodbye to many beloved dogmas, but the "new realism" meant a sustainable economic upswing. In 1975 these measures were approved at the 1st Party Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC). Politically, the so-called “gray decade” began with the adoption of the Soviet economic model. As in the socialist brother states, open debate or criticism was not welcome and was suppressed restrictively.

From about 1976 onwards the consolidation of the measures introduced began. There was a relatively stable economic growth of around 3.5 percent annually. The aim of economic policy was also to reduce Havana's dominance in the political and social fabric of the country before the revolution and to bring the different levels of development into line with the various provinces. For this purpose, industry was expanded, especially in the provincial capitals, and infrastructure projects such as B. the Farola tackled. As part of the division of labor within the Comecon, Cuba was particularly responsible for the export of raw materials. It was also developed as a center of heavy industry . The productivity both in industry and agriculture declined steadily. It was not until the early 1980s that the per capita output of Cuban agriculture was able to reach pre-revolutionary levels again.

From 1980 the Cuban economy grew even faster. Rates averaging seven percent were achieved. With the opening of parallel markets, where Cubans could supplement their basic supplies at slightly higher than official government prices, consumer demand and the supply of goods reached an equilibrium, albeit weak, for the first time. The Cubans called them “Years of the Fat Cow” and the revolution's promise of a better life seemed to be being fulfilled for the first time. However, domestic production could not keep up with the increasing demand. More and more goods had to be imported. Falling world sugar prices also increased the foreign trade deficit , which in 1985 totaled a third of imports and led to a drastic decrease in currency reserves.

Since the growth in the past few years was not achieved through an increase in labor productivity , but on the contrary exclusively through extensive expansion of production, Cuba fell into another liquidity crisis. The disadvantages of the centrally administered Soviet-type economic model also became abundantly clear in Cuba.

Crisis before the crash

Although the first phase of Cuban socialism with its practical abolition of malnutrition, mass unemployment and large income differences on a continent where they are considered to be one of the largest in the world, and the establishment of a reasonably efficient education and health system, showed remarkable successes, at the latest it was revealed At the beginning of the 1980s the weakness in the development of all socialist states: To achieve the same results, more and more funds had to be used.

In addition, the leadership of the Soviet Union, which itself was struggling with economic problems, exerted increasing pressure to reform Havana and gradually restricted the effective subsidies granted to Cuba from the mid-1980s: As the most important measure, Moscow adapted the conditions for the barter between oil and Cuba Sugar, which had so far deviated far from the world market price in favor of Cuba. The calculated preferential price for Soviet petroleum was increased and at the same time the price for the Cuban sugar received in return was reduced. Since Cuba earned a large part of its foreign exchange income by reselling part of its imported oil on the world market, the country's economy fell into a serious crisis. The negative effect was exacerbated by the drop in oil prices and the falling dollar.

The III. The 1986 PCC congress had to deal with the effects of the current recession. The conventional practice of Soviet economic model was now "as economistic and mercantilist criticized". It was recognized that intensive, qualitative growth would be necessary to improve the country's economic performance. However, market-oriented solutions such as decentralization and operational autonomy were clearly rejected.

Instead, in clear contrast to the perestroika introduced shortly before in the Soviet Union by the then Chairman of the State Council, Mikhail Gorbachev , the focus was on pure ideology with the reactivation of the idealistic concepts of Che Guevara and his “New Man” . The focus was on mobilizing the masses, moral appeals and campaigns to reduce bureaucracy . At the party congress, Castro announced the campaign of the so-called “rectificación de errores y tendencias negativas” (correction of errors and negative tendencies). Free farmers' markets were banned for alleged "neo-capitalist systemic disintegration", even though their share of retail sales was just one percent. Other small businesses that existed to a small extent were also greatly reduced.

As a further step, state economic control was recentralized and placed directly under the Executive Committee of the Council of Ministers . Agriculture and construction were partially militarized. Castro called for a return to "true socialist values".

Parallel to the domestic economic changes, the Castro government also changed its economic relations with non-socialist countries: in 1982 a law was passed to enable joint ventures with up to 49 percent company participation by foreign investors, which was supposed to attract capital from Canada, Western Europe and Japan. In addition, international tourism, which had been negatively associated with it since the revolution, was promoted as a new source of foreign currency from the mid-1980s. In 1986, the Cuban government also canceled servicing its foreign debt.

However, the economic goals of this “correction of errors” were clearly missed. After a minus of 3.7 percent in 1987, the production level of 1985 could be achieved again in 1989, but this could still only be achieved through purely extensive growth measures. The budget deficit rose to new record highs. Unproductive businesses had to be subsidized more. Absence from work increased and labor productivity continued to decline.

Special period in peacetime

With the collapse of the Eastern Bloc , the general conditions in Cuba deteriorated rapidly. In 1989, Cuba still handled 85% of its foreign trade with its brother states at the time. The dependence on imports was high due to subsidies.

From 1990 Cuba's foreign trade collapsed. In three years, the country lost three-quarters of its exports, nearly all of its lenders, and most of what it took to maintain its domestic economy. Even the reunified Germany did not feel bound by the contractual obligations entered into by the GDR . The local economy was highly unproductive. It specialized in the export of a few raw materials such as sugar or nickel and could not survive without imports. In addition, the USA tightened the embargo against the country with the Torricelli Act 1992.

In January 1990 Fidel Castro launched the so-called "periodo especial en tiempos de paz" (special period in peacetime), an emergency program similar to a " war economy with central command and total rationing" without major compromises in terms of a market economy . Therefore, at the PCC party congress that took place in October 1991, a dual strategy was adopted. The economy has been divided into a foreign exchange and a non-foreign exchange sector. Old foreign currency earners such as nickel mining and the newly created tourism sector were funded. Biotechnology and telecommunications also belong to the new foreign exchange sector. In order to concentrate the available resources on the old and new foreign exchange earners and to make them fit for the world market, the rest of the national production as well as the consumption of the population was radically cut down. At the same time, the US dollar was approved as a second currency by constitutional amendment in 1992 . Private property was also legal again with immediate effect in order to enable joint ventures with foreign companies.

Although minor successes could be achieved quickly in the new dollar sector, the domestic economy fell. Industrial production decreased by 80 percent by the end of 1993. Agriculture also had only 20 percent of the machines and fertilizers. Although attempts were made to keep agricultural production going by means of mass mobilization, it proved impossible to replace missing material with more human labor. As a result, the sugar harvest fell 60 percent by 1995 to its lowest level in 50 years. GDP fell 54 percent between 1990 and 1993.

Despite all the problems, Cuba's government tried to maintain the exemplary social policy. There were job guarantees to avoid mass unemployment. The free education and health system was also not affected. However, the population had to accept substantial losses in food supply, with which hunger and misery returned to Cuba. On the other hand, maintaining social standards also turned out to be counterproductive, as they created a huge budget deficit. The state provided the population with money, for which there was nothing to buy in the country. Only the black market flourished. In 1993, Cubans spent around two thirds of their income there. The US dollar was the only way to get high-quality goods, which is why it quickly developed into the secret reserve currency and the Cuban currency fell dramatically in value.

Since, on the one hand, the new foreign exchange sector was far too narrow for a sustained economic upswing and the state budget could not be burdened even more, but on the other hand, the population could not be expected to make further drastic cuts in living standards without provoking social unrest (which was the case with the Maleconazo Should come later in the summer of 1994) the approximately two million Cubans living abroad were chosen as the new source of foreign currency. Starting in 1993, ordinary Cubans were also allowed to own US dollars with no penalty and to obtain additional sources of income by means of transfers from abroad. The state skimmed off these foreign currencies through excessive prices in the "dollar stores", which were previously reserved for diplomats and foreigners. Although this was able to avert a liquidity crisis again, the state had to give up its principle of equality .

Further domestic reforms followed the US dollar as a second currency. At the end of 1993, around 200 self-employed activities in the service and small business sector were permitted. However, only family members, not employees, were allowed there. In agriculture, a large part of the oversized state farms was decentralized and transferred to new forms of ownership. The de-nationalized land was transferred to self-governing cooperatives. In the autumn of 1994, a fiscal policy was also introduced for the first time . Attempts were made to reduce the money supply and increase government revenues through higher prices, subsidy cuts and tax revenues . In addition, the free farmers' markets, which were only banned in 1986, were allowed again. In 1995, foreign joint ventures were generally licensed throughout the economy with the exception of the health, education and military sectors. The number of joint ventures increased from 10 (1987) to 374 (early 2000).

As a result of these measures, the economy stabilized. In 1996 there was a GDP growth of 7.8 percent. In the tourism sector, both the number of tourists traveling to Cuba and the gross income from tourism doubled between 1992 and 1996. It was also possible to increase nickel production through foreign investments.

After the crisis

With the increasing recovery of Cuba's economy, international observers saw Cuba as the new Caribbean tiger , the Cuban government's zeal for reform flagged. Although the so-called "periodo especial" has not officially been declared as terminated to this day, the Cuban government began practically to suspend the reforms of the domestic economy again with a resolution of the 5th Party Congress of the PCC in 1996. Instead, they concentrated exclusively on the world market. In the domestic sector, however, earlier liberalizations were withdrawn. The private sector with its small business, in which a good 40 percent of the workforce were officially or informally active, was again stalled. At least a third of the businesses either had to give up by the year 2000 due to massive tax increases or were forced into illegality. Agriculture and the sugar industry, formerly key sectors of the Cuban economy, "floated around and slowly dried up". Cuba continued to import much of its food from abroad. Using booking tricks, they also tried to present the budget deficit as “not that bad”. In 1999 it was officially just 2.4 percent of the gross domestic product.

After surviving the crisis, the focus was no longer on opening up the economy towards a market economy, but rather on “perfecting socialism”. Somewhat unexpected help came from Venezuela, where Hugo Chávez won the presidential elections in 1998 and, with the Bolivarian Revolution, began a fundamental transformation of the two-party system established there. With its internal radicalization, the Chavez government began to draw closer to Cuba. The increasing price of oil allowed Venezuela to supply Cuba with all the oil it needs. In return, Cuba sent tens of thousands of doctors, teachers and other specialists to Venezuela to support the local social missions such as Barrio Adentro or the Operación Milagro .

Ultimately, the high official growth rates since the turn of the millennium are mainly due to the high subsidies from Venezuela and the high nickel price until 2008. Economic growth barely reached the Cubans' private consumption. The gross fixed capital formation shrank between 1987 and 2007 by 47 percent. In 2006 the rate was 13.5 percent of GDP, well below the Latin American average of 20 percent and only around half that of 1989. Cuban economists consider at least double the investment rate necessary.

Due to obsolete generators from the Soviet era, long-lasting power outages occurred regularly in large parts of Cuba. To counter this problem, emphasis was placed on lower power consumption and energy-saving light sources. Cuba increased the number of solar and wind power plants . However, this development was made more difficult by the damage caused by Hurricanes Dennis and Wilma , which affected around half of the electricity production in the affected areas. In 2007, the country said it was able to cover its national electricity needs from its own production.

In 2004 the US dollar was banned from the official Cuban economy. It was still legal to own it, but you could only pay with the so-called convertible peso (CUC). It was initially pegged to the US dollar at a 1: 1 ratio. It was also possible to stabilize the actual local currency, the peso cubano (CUP), in such a way that its value now only fluctuates between 20 and 30 pesos per convertible peso. In 2005, Cuba changed the method of calculating its gross domestic product , so that it can hardly be compared internationally. The official growth rates are therefore likely to be rated lower in reality.

Raúl Castro's term of office

After Raúl Castro temporarily took over the post of Prime Minister of Cuba from his brother Fidel in 2006 because of his serious illness, he announced numerous reforms. One of his first official acts was the abolition of the ban on the sale of computer and video technology; Cubans were now allowed to conclude cell phone contracts and check into hotels that were previously reserved exclusively for foreigners.

After Fidel Castro had recovered to some extent from his serious illness and increasingly interfered in current politics with commentary, Raul's reform policy initially seemed to have come to a standstill.

In the face of another severe liquidity crisis, triggered by the global economic and financial crisis and by the hurricane season 2008 , which caused severe damage to Cuba's infrastructure and agriculture , according to government information, more far-reaching economic reforms were announced in September 2010, some of which took place over the middle of the Reforms that came into force in the 1990s and were later partially withdrawn.

Cuba has to import a large part of its food from abroad. The waning agriculture is to be brought back into shape with the help of the leasing of state land to private farmers, higher purchase prices for agricultural products and the decentralization of decision-making processes.

Due to a huge surplus of labor in the state-owned companies, a short-term layoff of around 500,000 state employees was announced, but this was later defused. In order to catch those to be dismissed, a list of 181 professions was drawn up in which Cubans can start their own business. What was new, above all, was the possibility of employing employees who did not belong to the family, for which social security contributions would then have to be paid. However, experts criticize the list of self-employed activities as inadequate. For the most part it only includes very simple activities such as taxi drivers, shoe shine, etc. They call for the list to be expanded to include academic professions.

The main goal of the reforms is not to dismiss the numerous surplus workers in the state sector into unemployment, but instead to place them in the state-regulated private sector, with the state remaining the largest employer. The admission of employees outside of family members who have been permitted since the 1990s, however, also creates a new employer / employee relationship that was previously frowned upon in socialist Cuba. Furthermore, the excessive expenditure on social security systems is to be reduced, while social security is to be retained, for example by further restricting the flat-rate subsidization of goods via the libreta and instead introducing subsidies based on need. State-owned companies should be granted more autonomy in making business decisions. Rising labor productivity should lead to rising wages. They should be allowed to depend on the respective operating result .

By the end of 2011, the number of independent “Cuentapropistas” had risen from originally around 100,000 to over 362,355. More than 87% of them are union members. In June 2011, according to a survey by Freedom House , 41% of respondents felt that Cuba was making progress (December 2010: 15%). 30% of those questioned would also rate their own economic situation and that of their families as “good” (December 2010: 11%).

In a Council of Ministers meeting on July 1, 2011, the simplified purchase / sale of real estate and cars produced after 1959 was announced. Foreigners and locals should be treated equally in the future. The simplified used vehicle trade was decided by the Council of Ministers at the end of September 2011 and came into force on October 1, 2011.

On November 10, 2011, for the first time since the revolution, private trade in apartments was also permitted. Another new feature is the possibility of granting small loans to private individuals, such as the self-employed and private smallholders.

Economic growth estimated for 2011 at the beginning of December was 2.7 percent, below the government's expectations of 3.0 percent. It was the second worst growth in all of Latin America.

The total volume of investment in the economy increased again in 2011 for the first time since 2008 and has increased by 2.2% compared to the previous year. The gross income from tourism increased by 26%, the gross foreign exchange income by 40%.

For 2012 it was planned to give government companies the opportunity to use the services of private companies (e.g. transport and cleaning). The prices for building materials were reduced by 20 to 30% during the 8th session of parliament at the end of December 2011, at which the MPs were informed about the state of the economy and the plan for 2012 was decided in order to facilitate private renovations. In addition, subsidies for building materials are made available to poor families and victims of natural disasters. More than 1,300 of 5,000 applications across the country were approved on the first day. As of February, loans totaling Peso 20 million had been issued to over 7,000 people. In addition, since January 15th it has been possible to transfer current loans to the new system. In the period that followed, the availability of building materials has noticeably improved. The government has been able to rent vacant buildings to private service providers since January. Edible oil and mayonnaise prices were also reduced to support the private food stalls.

While the total number of new self-employed businesses grew, around 25 percent had to go out of business again, which, according to Cuban economist Omar Everleny Perez, is a very low rate.

Agricultural production grew by 8.7% in 2011. The construction sector grew by 12.9% and the manufacturing industry by 3.2%. As a result of the increased presence of small private businesses on the streets of Cuba, the importance of the Peso Nacional has increased again.

In 2012, the supply crisis from around 2008 was overcome. According to the Spiegel correspondent Jens Glüsing, the atmosphere was “more open and relaxed” and the economic upturn can be felt everywhere.

At the end of February 2012, the super-ministry for basic industry (MINBAS) was split into two new ministries, one for industry and one for energy and mining. The latter is responsible, among other things, for nickel mining, which is important for the export market, as well as for oil drilling and production in the Gulf of Mexico . In May 2012, Cuba had 1,618 private restaurants out of a total of 8,450 restaurants in the country.

At the end of March, the government reported an official unemployment rate of 2.5%. However, individual government-affiliated trade unionists estimate the actual unemployment rate at more than 25 percent. In order to further carry out the separation of state and companies, the information and communications ministry is also to be restructured.

Since September 2012 the UBPCs no longer receive subsidies from the state. Since December 1, 2012, state restaurants and cafeterias can be leased by self-employed for an initial period of ten years. Initially, the new regulation will be implemented in 200 selected businesses with one to five employees and will then be gradually expanded to 1,183 restaurants throughout the country, which corresponds to 14% of all businesses in this sector.

On December 11th, a new cooperative law came into force in Cuba, which provides for the formation of initially 200 cooperatives in the non-agricultural sector, including sectors such as transport, construction, fishing, gastronomy and house services. The production of building materials should also be carried out by cooperatives. The cooperatives obtain their means of production through lease and rent from the state, but in contrast to its own operations they are viewed as independent legal subjects and managed autonomously by their members.

According to official figures, the economy grew by 3% in 2012.

embargo

A trade, economic, and financial embargo was imposed on Cuba by the United States on February 7, 1962 after the Cuban government expropriated property from United States citizens and businesses , including the United Fruit Company and the ITT .

Briefly suspended by President Jimmy Carter in the late 1970s, it has been in force ever since. In 1992, the embargo was tightened with the Torricelli Act . The Helms-Burton Act cast the embargo, which until then had been the decision-making power of the respective US president , into force of law and also allowed the extraterritorial application of US law. For example, Cubans in exile can sue foreign companies in US courts for investing in their property expropriated by the Cuban government, even though they were not US citizens at the time. In addition, exact conditions for the transformation process of a possible post-Castro era are specified.

Experts question the amount of damage caused by the embargo as stated by the Cuban government. Cuba's economic problems are primarily due to internal development blocks. The embargo strengthens the regime, as they can blame external factors such as the blockade for the failure of their own economic policy. Other Latin American countries, even though they enjoyed unrestricted trade with the US, failed to achieve the same economic performance.

Economic policy

independence

After all private craft businesses were banned in 1968, in the course of the economic crisis during the special period in September 1993, 117 independent professions - called “trabajo por cuenta propia” (work for one's own account) in Cuba - were permitted and opened up a small amount of economic freedom for the Cuban population. This measure enabled the government to reduce open and covert unemployment in the country. The state was obviously no longer able to cope with the increasingly worsening shortage economy and supply crisis without resorting to private initiative.

In June 1995 the number of possible fields of activity was increased to over 180. The new self-employed significantly enlivened the sometimes extremely dreary streetscape in the cities, especially in Havana. Before that, self-employment was socially discredited and felt on the verge of legality. In 1989, only 0.7 percent of those in employment were officially self-employed. In 1995 it was already five percent. The new self-employed could set prices freely according to supply and demand . However, the government reserved the right to take action against undefined excessive prices as well as speculators and parasitism at the expense of the general public.

The supply situation and the possibilities of consumption had greatly improved due to the opening up to the population. On the other hand, the possibilities of the new private sector could not be fully used. Restrictive laws, poor legal security , arbitrariness by the authorities , low mobility of the population and other obstacles were some of the causes. In addition, a relatively low supply was offset by high demand , which led to high prices on the supply side. This in turn could only be afforded by Cubans who had a regular income from foreign exchange, for example through transfers from their relatives living abroad. As a result, the new self-employed earned a relatively high income. It is not uncommon for a self-employed person to earn in a single day what a state employee received in a month. Incidentally, this is in stark contrast to other Latin American countries, where simple traders or providers of simple services cannot be counted among the upper income class, but on the contrary often earn a lower income than the wage earners. This situation also bleeds the qualified professions to death, as self-employed people can earn a multiple of what one gets as a teacher or doctor in the civil service.

After Cuba's government had tried since the late 1990s to drastically restrict the newly emerging private sector in the face of new patrons such as Venezuela's President Hugo Chávez , the government under Raúl Castro, who took over the business of government from his sick brother Fidel in 2006, saw itself as chronic paralyzing economy, exacerbated by the global economic and financial crisis from 2007 and a hurricane season that was devastating for Cuba in 2008, forced to start a new initiative for self-employment. With a list of 181 occupations, which experts consider to be inadequate because it largely contains only simple jobs, the planned mass layoffs from the state sector are to be counteracted. Mostly, however, only previously illegal activities were legalized. What is new is that the “ Ich-AGs ” are also allowed to employ employees and do not have to be run exclusively by the owners and their family members as before. In 2013, 18 additional business areas for small private companies were approved, bringing the total to around 200. This now also includes the “ agent for private real estate” for brokering the private sale of apartments and real estate.

In order to avoid “social deformations” caused by the growing prosperity of the new self-employed and also to minimize competition with state businesses, the state tries to restrict private business activity. Private sellers of agricultural products and clothing sellers were banned from selling imported goods. With the latter group in particular, it is customary to have foreign travelers bring them informally inexpensive clothing and then sell them in Cuba for a corresponding additional charge. At the same time, in November 2013, private computer game clubs and small cinemas were banned. According to an official announcement from the government, this was "never approved". In particular, the offer of 3D films aroused great interest among the population, as nothing comparable was offered by the state. As a result, this ban met with criticism not only from the ordinary population, but also from state-affiliated Cuban bloggers.

In mid-2013 there were just under 430,000 registered self-employed people in Cuba.

Cooperatives

On December 11, 2011, a new law on cooperatives came into force in Cuba . As part of a pilot project, 200 cooperatives were set up in the non-agricultural sector; these work in areas such as transport, construction, fishing, gastronomy and house services. The production of building materials should also be able to be carried out by cooperatives, which means that in addition to services, productive activities are also part of this sector. The cooperatives can also be formed directly from the workforce of the former state-owned companies.

The cooperatives obtain their means of production through lease and rent from the state, but in contrast to its own operations they are viewed as independent legal subjects and administered by their members. First degree cooperatives can be formed by three or fewer natural persons, second degree cooperatives can be formed from two or more first degree cooperatives. According to the law, all members of the cooperative have the same rights to property of the cooperative and the same voting rights. The profits are administered and distributed by the members themselves.

The cooperatives have had to pay taxes since 2013. The income from renting local real estate is paid directly to the provincial governments. The taxes on profits of the cooperatives are lower than those of the self-employed.

The American analyst Richard Fineberg sees this as an opening of the doors for social innovations, because it would create a new economic sector that is neither capitalist nor socialist. Instead, it is democratic, productive and works at the grassroots level.

Tax policy

After the revolution of 1959, Cubans did not have to pay income tax because all taxes were included in their salaries. However, self-employment, which was permitted again from 1993, required the establishment of a tax administration. Initially, the new self-employed only had to pay comparatively low taxes , but from 1996 progressive profit taxes were introduced. Even employees with foreign exchange income, for example in the tourism sector, now had to pay taxes.

For the “new self-employed”, the tax policy that has been in place for them since 2011 is inconsistent. While some can meet their tax liability without any problems and still earn enough, others have great problems raising even the property taxes required for their self-employment. In January 2012, the Ministry of Information released software for the self-employed to help them calculate their tax expenses and manage their businesses.

Monetary policy

In 1993, at the height of the supply crisis, the Cuban government legalized the possession and use of the US dollar, which had been forbidden since 1960 and which had been officially banned until then, but had already become the common pillar of the black market, which had grown rapidly due to the shortage of goods and peso inflation was. From now until 2004, the dollar gradually became the main currency. The hard currency entered the country on the one hand through international tourists, to whom Cuba was now increasingly open, and on the other hand through funds from the USA and other countries that have now been approved and sent to relatives on the island - which by 2012 amounted to an estimated 2.6 billion dollars each Year grew. To ensure that access is as extensive as possible, the government set up state-run "foreign exchange shops" ("tiendas recaudadoras de divisas", TRD), in which goods imported via the state import monopoly are offered at high surcharges. The first “dollar stores”, the so-called “diplotiendas”, which were only permitted for foreigners and Cubans abroad, had existed as early as the late 1970s, comparable to the Intershops in the GDR and other communist states, which originally offered groceries, household goods and clothing that were originally classified as luxury were. In contrast, the mostly state-subsidized basic necessities continued to be sold in traditional shops for pesos . However, the purchasing power of the peso and the choice of goods in peso shops decreased dramatically in the course of the economic crisis. As a result, there has been a steadily growing discrepancy in the standard of living of the population between those who have access to one of the new sources of income and those who at most receive a state income that has been severely devalued by inflation or even only an old-age pension also paid out in Cuban pesos. Since then, jobs in which one could receive salary in dollars or tips from foreign tourists or business people have been highly sought after. It became normal for doctors, engineers, scientists, and other professionals to suddenly work in restaurants or as taxi drivers.

In October 2004, the government decided to replace the US dollar as the accepted means of payment in order to absorb the foreign currency that was circulating in the country and urgently needed for state imports even more effectively. It was replaced by the convertible peso , which, although not traded internationally, is pegged to the dollar and was introduced for domestic payment transactions as early as 1994. In order to generate further income, a ten percent surcharge was introduced for exchanging US dollars for convertible pesos, which is not due for other currencies. As a result, tourists are advised to enter with other currencies, such as euros , Swiss francs or pounds sterling . In some tourist areas, the euro is also directly accepted as a means of payment for many shops.

The abolition of the double currency system was an official policy goal within the framework of the “Lineamientos” (guidelines) of the economic reforms called “renewal of the socialist system” in April 2011 on the VI. Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba decided. In July 2013, President Raúl Castro reiterated the government's intention to abolish the parallel currency system, which he described as "one of the greatest obstacles to progress". In October 2013, the state media reported that the government had decided on a timetable for the gradual merging of the two parallel currencies, but without giving any concrete information on the timing or details of the planned measures. The government promised that, in contrast to the cuts made by various European countries during the euro crisis , their policy would not mean “shock therapy” or defenselessness for the population. In the first phase of the process, according to the announcement, the business sector will initially be affected by changes that are intended to create conditions for increasing efficiency, for better measurability of economic performance, as well as incentives for the export economy and import substitution. The first measures in this area were the higher participation of companies in export revenues, as the state now passed on to companies up to twelve instead of the previous one Cuban peso per US dollar for profits made in foreign trade. Only in the later course of the schedule that has now been decided will measures of the currency conversion also affect natural persons.

Economic freedom

In 2011, Cuba was ranked 177th out of 179 nations on the Index of Economic Freedom . The study found that typical imported goods were food, fuel, clothing, and machinery. The main exports were nickel, cigars, and state-sponsored labor for which the government received many times the normal salary. Due to a lack of investment, Cuba's sugar industry is no longer profitable. The island also became an importer here. Venezuela currently delivers up to 80,000 barrels of oil a day at very favorable conditions. Cuba itself produces low-quality, sulfur-containing crude oil on a small scale . The aid from Venezuela, however, allowed the Cuban government to reverse a large part of the small market economy reforms, such as permits for self-employment as a snack vendor or as a bicycle repairer. However, this changed again with the VI. PCC party conference in April 2011.

Individual branches of industry

tourism

Before the revolution in 1959, Cuba, especially Havana, was the entertainment hub for Americans and the Cuban upper class. Mafia and prostitution flourished. From 1959 international tourism collapsed completely. Initially, national, “socialist” tourism was built up. Foreign tourists did not return to the island in significant numbers until the 1980s. At that time, 200,000 to 300,000 visitors came to the island annually.

With the collapse of the Eastern Bloc around 1990, tourism took on a completely new and central role as a source of foreign currency. The number of tourists rose steadily from 1991 and reached the million mark for the first time in 1996. 90 percent came for recreational purposes and only 1 percent were business travelers. In the mid-1990s, tourism outstripped the importance of sugar , which for a long time was the main source of foreign exchange income and the mainstay of the Cuban economy. Tourism occupies a major role in the government's development plan. A senior government official even called it the “heart of the economy”. Cuba spent great resources creating new tourist facilities and renovating historical structures for use in tourism. In 1999, according to official Cuban estimates, around 1.6 million tourists visited Cuba and generated gross sales of around 1.9 billion dollars. By 2011 the number of tourists rose to over 2.7 million visitors. As in previous years, gross income from tourism this year was still below that of 2005.

In general, tourism has so far been little integrated into the Cuban domestic economy. For example, it was strictly forbidden for hotel operators to buy the food they needed at local farmers' markets. Purchasing had to be done through central government agencies. Two thirds of the gross income is needed to secure the supply. Most of the goods required for this have to be imported from abroad in exchange for foreign currency. The state has to share the rest of the profit with foreign investors. Additional income was achieved exclusively through higher numbers of tourists, i.e. again through typical socialist extensive growth. There was no improvement in services or any reduction in costs. The Cuban leadership has recognized this problem and is trying to counteract this with appropriate measures. Since 2011, farmers have been allowed to sell their production directly to hotels.

The sharp rise in tourism had far-reaching economic and social effects in the country and created a new two-tier economy and the promotion of a kind of tourist apartheid , as the separation of tourists from the population is also known. The situation was also made more difficult by the influence of the US dollar on the Cuban economy in the 1990s, which formed the basis for a parallel economy; on the one hand that of the dollar - the tourist currency - and on the other hand that of the peso. Scarce import goods (such as toilet paper or smartphones ) and even some local products, such as rum and coffee, could practically only be purchased in dollar stores, or nowadays only with the substitute currency, the peso convertible (CUC). As a result, Cubans who only work in the peso economy apart from the tourism sector and tourist flows were and are economically disadvantaged. By contrast, those with dollar (or CUC) income from tourism services began to live more comfortably. Prostitution and sex tourism revived. Numerous Cubans tried to do business with tourists semi-illegally or illegally, which is called Jineterismo in Cuba . This widened the gap between different standards of living and was at odds with the socialist tenets of Cuban society.

Agriculture

History

Agriculture before and first years after the revolution

Historically, Cuba's agriculture is one of the most important economic factors. Tobacco , sugar and coffee have played an essential role in Cuba's export economy since the beginning of colonization . Until the middle / end of the 19th century, it was characterized by slave ownership. Even after independence, it was not possible to break away from these structures in the first half of the 20th century.

In two agricultural reforms in 1959, first the large landowners and then in 1963 the medium-sized farmers were expropriated. The latter is regarded as a serious mistake, as not only “anti-revolutionary elements” were expropriated, but the peasant production and trade structure in general was also destroyed. However, the expropriated land was not distributed to new farmers, but became state property. The motto was “The more state property, the more socialism”. In 1963, 70 percent of the agricultural land was state-owned and those who worked the land were dependent wage laborers. Around a quarter of the space remained in private ownership. A forced collectivization as in other socialist countries did not exist in Cuba.

The state areas were processed in a highly mechanized manner. There was heavy use of pesticides . As a result, agricultural activities were strongly humanized, which meant a significant decrease in physically hard work. While state farms cultivated an area of up to 28,000 hectares , the proportion of private farmers steadily decreased.

With the intensive use of machines, fertilizers, pesticides, etc., the focus was more on large-scale US farms than on Soviet production methods. However, typical socialist problems soon emerged. Increases in production could only be achieved through an extensive expansion of agricultural production. You had to invest more and more capital to achieve the same result. Agriculture increasingly developed into a subsidy grave . It was not until the early 1980s that pre-revolutionary production data were reached again. Cuba thus lagged behind comparable Latin American data. In 2000, for example, productivity in rice cultivation was 25 percent lower than in the Dominican Republic . Between 1960 and 1990 around a quarter of all investments went into agriculture. Attempts were made to compensate for the weakness by importing more foodstuffs, which led to an even greater expansion of sugar cane cultivation, Cuba's main source of foreign exchange , in order to generate the necessary foreign currency . In 1989 only 43 percent of agricultural production contributed to national self-sufficiency.

Overall, after the revolution, Cuban agriculture failed to alleviate historical dependencies. Both the productive and the consumptive dependence on imports were preserved. The labor shortage in agriculture had worsened. In 1990 the rural population was only 25 percent of the total population.

In cattle breeding, attempts were made to breed high-performance cattle suitable for the tropics. To this end, attempts were made to cross the domestic Zebu cattle with the Holstein cattle imported from the Soviet Union . This attempt turned out to be a gigantic failure, which is still having a negative effect on Cuba's meat and milk production today.

After the collapse of the Eastern Bloc until the end of Fidel Castro's term in office

After the collapse of the Eastern Bloc in the early 1990s, Cuban agriculture had to completely reorient itself. However, no lessons have been learned from the previous failure. Instead of decentralizing agriculture, numerous, around 10,000 between 1989 and 1993, previously private smallholders were bought up and nationalized. The newly issued “plan alimentario” (nutrition plan) provided for the compensation of import losses through increased use of labor and new technologies. This plan completely failed. The huge areas laid out for mechanized processing could no longer be managed efficiently with the limited resources available; by 1992 they had dropped to a fifth of the pre-crisis value.

The transport losses alone - loss or rotting during transport - amounted to around a third. Another third was diverted to the black market .

In September 1993 there was another agricultural reform. The cultivation areas were divided into smaller units and leased indefinitely to self-managed cooperatives , so-called “Unidades Básicas de Producción Cooperativa” (UBPC). The main aim was to increase productivity, open up to new producers, raise the standard of living in rural areas and adapt the size of the farms to the reduced resource-technical possibilities. They wanted to increase food production significantly. The members of the cooperatives formally became owners of the lands they cultivated. They were given the right to self-determination about the purchase of means of production and personal decisions. In reality, however, it was a hybrid system consisting of a state-owned company and an independent cooperative. The state retained the right to intervene. According to criteria that were not precisely defined, the state could decide to dissolve a UBPC on the basis of interests defined by the government. In addition, the state had the right to issue instructions about the agricultural crops to be grown and retained its price monopoly. Until October 1994, the cooperatives had to sell their entire harvest to state buyers at the lowest prices. After that, the situation improved slightly: With the reintroduction of the farmers' markets, which were banned in 1986, it was possible to sell excess production there at free prices.

Because of the constant state intervention and the de facto non-existent entrepreneurial freedom, the UBPCs developed unsatisfactorily. At the end of 1999 more than half of the cooperatives were unable to cover their costs and were dependent on subsidies or bank loans. On the one hand, for example, there were high prices for replacing production resources from the state and state services; on the other, there were extremely low state purchase prices for the harvest. In addition, the majority of the heads of the cooperatives employed lack the necessary business management knowledge to manage such an agricultural operation. Neither could the urban population - Cuba has a high degree of urbanization - be won over to work in agriculture.

After Raúl Castro took office

In 2008, 51 percent of the arable land in Cuba was fallow or poorly managed. Numerous bureaucratic obstacles to the state-controlled planned economy and the omnipresent lack of spare parts and fuel make life difficult for farmers. The self-covering of food needs could result in a considerable release of the foreign currency funds previously tied up by food imports. Cuban agriculture is now considered to be "probably the most unproductive in the region". In 2010, the import quota was between 70 and 80 percent of the food consumed in Cuba.

Raúl Castro declared the increase in agricultural production to be the main task. In order to use the untapped potential, the government decided to lease previously unused land to private farmers. At the time of the VI. At the party congress of the Communist Party in April 2011, around 1.1 million hectares, a good sixth of the total agricultural area, had been given to 143,000 people and a few cooperatives. In February 2012 it was 1.6 million hectares. The number of people employed in agriculture has increased from 250,000 to 420,000. The total arable area in Cuba is 6.6 million hectares, of which 3.0 million are cultivated.

Significant structural problems remain, however, which cast doubt on the short-term success of these measures. On the one hand, the new farmers lack long-term prospects. The leases only run for a period of ten years. There is also a lack of markets for purchasing inputs such as fertilizers , herbicides , means of transport and breeding animals . In addition, there is a lack of know-how, 70 percent of the new farmers had no experience whatsoever in agricultural production and had no capital for investments.

According to the Cuban government, agriculture should not be made more productive through higher mechanization , because this would require expensive imports of corresponding agricultural machinery and spare parts as well as fuel, instead one relies on classic draft animals such as ox , which are also not available in the desired extent .

Since the end of 2011, private smallholders have had the opportunity to take out loans from state banks. In addition, state and cooperative farms are allowed to sell their products directly to tourist facilities such as hotels without state intermediaries. The prices for this can be freely negotiated between the parties.

Both Cuban experts and private farmers consider the measures taken by the government to be insufficient to help agriculture out of the crisis in the long term. Instead of selective measures, structural reforms would have to take place. For example, it is not clear why only state-owned companies are allowed to sell their crops directly to hotels, but not private farmers. Furthermore, the state monopoly on distribution is criticized as ineffective. Since agricultural production companies have to sell around 80 percent of their production at fixed lowest prices to state distributors, many private farmers would mostly only produce for their own needs. Nevertheless, they produce on 24 percent of the area, the state-affiliated cooperatives cultivate around 70 percent, a good 57 percent of the food. In December 2011, the extension of the law from 2008, which allows private individuals to lease state land for a certain period of time in order to farm on it, was made and now provides that farmers lease up to 67 hectares of land for 25 years and have theirs on it Can build houses. In addition, farmers can now open commercial accounts that make it easier for them to trade with the government.

In 2011, agricultural production grew by 8.7%. While the production of tubers and roots decreased by 2.5%, banana production increased by 17.2%, vegetable production by 5.4%, corn production by 9.1%, bean production by 66.1% and rice production by 43.7% compared to the previous year. Citrus production decreased by 23.3%. Meat production increased by 6%. A total of 459,700 tons of rice, 248,900 tons of corn and 72,900 tons of beans were harvested in Cuba in 2011. The urban agriculture plan was exceeded by 105% in 2011. 1,052,000 tons of vegetables were harvested. Production of 1,055,000 tons is planned for 2012. Nevertheless, despite all the liberalization, Cuba's agriculture produced less food itself in 2012 than five years earlier, in 2007. Only the cultivation of rice and beans could be increased significantly compared to this year. In 2011 consumer prices for food rose by 20 percent.

A $ 200 million loan agreement was signed with Brazil in August 2012. The loan is to be paid out in three tranches in 2012 and 2013 and is used to purchase agricultural equipment from Brazil in order to improve the food supply from domestic production in Cuba.

In September of the same year, a greater independence of the agricultural cooperatives (UBPCs) was decided. At the same time, these companies will have to forego state subsidies in the future, which is likely to mean the end of a large part of these often inefficiently working companies. In 1994 there were still 2519 of these cooperatives, by 2012 the number had dropped to 1989. At that time they were working a good 1.77 million hectares, which corresponds to 28 percent of the agricultural area in Cuba. 23 percent of the area managed by the cooperatives lay fallow. 57 percent of the companies have economic difficulties and 16 percent are almost no longer viable.

Individual cultivation products

sugar

Cuba used to be the most important sugar producer and exporter in the world. In 1989 over eight million tons of sugar were produced. However, this amount fell to around 3.5 million tons in 1994 and 1995, a negative record. Due to chronic underfunding and natural disasters, Cuba's sugar production decreased dramatically. In 2002 more than half of the sugar mills were closed. Their number fell from 155 to 61. 60 percent of the area previously designated for sugar cane was also allocated to other agricultural crops. Cuba's sugar production of 1.1 million tons (2010) was the lowest since 1905.

At the end of September 2011, Cuba's Council of Ministers decided to dissolve the sugar ministry, which was created in 1964 and whose tasks are to be taken over by a new state holding company . Another five unprofitable of the 61 sugar factories ("centrales") that had been unprofitable by then should also close. These measures are intended to help make the sugar sector profitable again and thus generate export earnings in foreign currency. At the beginning of 2012, the sugar industry was opened to foreign direct investment. A contract was signed with the Brazilian company Odebrecht that they should run the sugar factory "5 de Septiembre" near Cienfuegos for ten years . In the 2010–2011 season, yields rose to 1.2 million tons for the first time in years. In the 2011/12 season, yields increased by 17% to 1.4 million tons.

tobacco

After Greece, Cuba has the second largest cultivation area for tobacco and the world's lowest yield per area. In 2011, tobacco was grown on an area of 16,400 hectares. Tobacco production in Cuba has remained roughly the same since the late 1990s. Cuban cigars are world famous, and almost all of their production is exported. The center of Cuban tobacco production is the province of Pinar del Río. In 2000, tobacco was the third largest source of foreign currency for Cuba after sugar and tourism. The volume of Cuban cigar exports grew by 9% in 2011 compared to the previous year and amounted to US $ 401 million. The two main types of tobacco grown in Cuba are Corojo and Criollo .

Tubers and plantains

The category called “Vianda” in Cuban Spanish includes energy-containing crops such as yuca , malanga , potatoes and plantains . A total of 229,900 hectares are used for the cultivation of these products (2010).

Yuca is grown on 89,000 hectares (2010). It comes from the Latin American region and is grown in almost every country in the region. Cuba is the second largest producer in the Caribbean with an annual production of 399,400 tons (2010). In 1999, production per hectare was the lowest of all Caribbean countries, but has since increased from 2.5 to 4.24 tons per hectare (2010). Most of the Yuca production is intended for direct consumption in the household without further processing. A small part of the Yuca harvest is processed into sorbitol in a factory in Florida (central Cuba ) .

The per capita consumption of potatoes is 25 kg per year. They are mainly eaten in the form of french fries . The cultivation area is 6300 hectares and the yield 167,300 tons, mainly of the Désirée variety. The cultivation areas are mainly in western Cuba. Seed potatoes are partly produced locally and partly (approx. 40,000 t per year) imported from Canada and the Netherlands. Meanwhile, Cuba is also growing soy with the help of Brazilian experts.

rice

Rice is mainly grown on the west coast. Two harvests a year are common there. The majority of the rice farms are state-owned or owned by cooperatives. In 2011 rice was grown on an area of 177,500 hectares, the yield was 459,700 tons. Cuba is a large rice importer; imports reach over 400,000 t per year, which corresponds to around 60% of demand. Rice production is limited by the lack of water, artificial fertilizers and modern agricultural technology. The harvest volume per hectare is below the average for the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean .

In 2011, Cuba and Vietnam completed a technology transfer program that aims to increase the rice harvest by 14% annually by 2015. For this purpose 100 hectares of land are being prepared in Pinar del Río. A research station in this province is experimenting with 13 different rice varieties. A total of 100,000 hectares of land will be used for the project. Currently, the varieties Inca LP5 and Inca LP7, bred in Cuba, are predominant. Within this project, a yield of 4.7 tons per hectare was achieved in 2011.

Citrus fruits

Oranges account for 60% of production and grapefruit for 36% . In citrus production, the first foreign investment in Cuba's agriculture was officially registered in 1991: the participation of an Israeli company in a production and processing plant in Jagüey Grande , about 140 km east of Havana. The products are mainly sold in Europe under the name "Cubanita".

In 2011, citrus fruits were grown on 1,600 hectares, the yield was 237,300 tons.

coffee

Coffee is mainly grown in the mountains and hills of the eastern Cuban provinces of Santiago de Cuba and Guantánamo. In the 2011/12 season, 7,100 tons of coffee beans were harvested in Cuba, 24% more than in the previous year, when the historically lowest coffee harvest was recorded at 6,000 tons. According to official reports, 85% of the beans are of high quality.

In 1959, in the year of the revolution, coffee production was still around 60,000 tons. Since then it has steadily decreased. Analysts estimate that ten to twenty percent of the harvest, despite the increase in purchase prices in recent years, does not end up in official channels, but is diverted to the black market, where far higher prices can be achieved. Between 2010 and 2011, Cuba had to import 18,000 tons of coffee for internal consumption. Coffee is currently mixed with “Chícharos”, a Cuban type of pea , for subsidized sales via the Libreta .

Energy industry

Although most of the fuels needed to generate energy have to be imported, Cuba is a country with a very high energy consumption due to a lack of efficiency. In the late 1980s, Cuba's per capita energy consumption was the fourth highest in Latin America and, for example, twice as high as in the USA or three times as high as in France . In the crisis years of the 1990s, consumption rose by a further quarter.

Until 1990, the country was almost entirely dependent on oil imports from the Soviet Union. The lack of supplies after the collapse of the Soviet Union plunged power generation in Cuba into a crisis. The state now has twelve conveyor systems of its own. In 2009, Cuba covered around half of its oil needs itself. New oil deposits, including in the Gulf of Mexico , are being developed with Canadian and Chinese companies; Companies from Spain , Norway , India , Malaysia , Vietnam and Venezuela received concessions . Foreign investment is around $ 1.5 billion. In 2012, the most costly test drillings to date took place; the various foreign partners were unable to find any commercially exploitable deposits. The "Camilo Cienfuegos" oil refinery in the city of Cienfuegos on the south coast, which was shut down in 1995, was put back into operation in 2007 with the help of Venezuela. By 2014, their capacity is to be increased from 65,000 to 150,000 barrels per day. By 2016, Cuba wants to be able to cover 90% of national gasoline consumption with its own production.

Cuba began a first program of renewable energy sources in the 1980s, the importance of which increased during the period of the greatest economic crisis in the 1990s. As a result of the generous oil deliveries from Venezuela, however, the balance turned back in favor of fossil fuels. In 2012, the share of renewable energy sources in electricity generation was only 3.8%, a very low figure even in regional comparison. According to government plans (as of 2012), the proportion should increase to 16.5% by 2020. According to a study from the 1990s, up to 60% of Cuban's energy needs could be met from biomass .

In 2012, 9,624 solar panels, 8,677 wind turbines, 6,447 solar heating, 554 biogas and 173 hydropower plants were in operation in Cuba . At the end of 2017, Cuba had 34 photovoltaic parks with an installed capacity of almost 90 MW.

Photovoltaics are mainly used to provide a decentralized power supply in remote areas, e.g. B. for health centers and schools. In 2011, Cuba generated more electricity with lower fuel consumption than in previous years. A grid maintenance and restoration plan was also drawn up to improve power availability and prevent blackouts. 92,000 power networks were installed, so 20,000 low-voltage areas could be switched off. In addition, 75,000 new connections were installed and a new payment system was introduced for the state sector. In 2012, Cuba produced 18,431.5 GWh of electrical energy.

Nuclear energy

Several projects have started, e.g. B. the Juraguá nuclear power plant , but none of these power plants were put into operation.

statistics

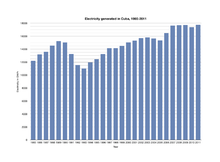

- Electricity - production: 17,754.1 GWh (2011)

- Electricity - installed power plant capacity: 5,913.9 megawatts (2011)

- Electricity - gross production by source (2011):

- fossil fuels: 87.8% (14,771.8 GWh)

- of which energy generators (diesel or petrol): 24.8% (3,659.1 GWh)

- Gas turbines: 11.6% (2,055 GWh)

- Renewable energies: 0.7% (117.7 GWh)

- of which hydropower: 84.3% (99.2 GWh)

- of which solar and wind: 15.7% (18.5 GWh)

- fossil fuels: 87.8% (14,771.8 GWh)

- Primary energy production - production by source (2010):

- Petroleum: 3,024,800 tons

- Natural gas: 1,072,500 m³

- Hydro power: 96.6 GWh

- Wood: 114,100 m³

- Sugar cane products: 3,488,400 tons

- of which bagasse: 3,027,300 tons

- Secondary energy production - production by source (2010):

- fossil fuels: 5,003,200 tons

- Charcoal: 67,700 tons

- denatured alcohol: 187,900 hl

- processed gas: 210,200 m³

- Share of primary energy to secondary energy production: 47.6% / 52.4% (2011)

- Degree of electrification: 97.7% (2011)

- Electricity - Consumption: 17,396 GWh (2010)

- Private households: 6,667 GWh

- Industry: 4612 GWh

- Agriculture: 278 GWh

- Transport sector: 251 GWh

- Trade: 241 GWh

- Construction sector: 73 GWh

- others: 2505 GWh

- Losses: 2768 GWh

- Electricity - export: 0 kWh (2012)

- Electricity - import: 0 kWh (2012)

Industry

Cuba's biotechnological and pharmaceutical industry is currently booming , making it one of the leaders in the world market and growing in importance for the Cuban economy. Among other things, vaccines against various viral or bacterial pathogens are exported and promises are made to subject anti- cancer drugs to extensive clinical tests .

Cuban vaccines may be used. a. shipped to Russia, China, India, Pakistan and Latin American countries.

International trade