Anti-communism

The anti-communism is a political attitude, dealing with each different weight to the theories , ideologies , the political movements and groups as well as the form of government of communism depends. In contrast to anti- Bolshevism , which was particularly directed against the establishment and spread of conditions such as those that prevailed in Soviet Russia after the October Revolution or the Soviet Union and was often anti-Semitic , the term anti-communism covers a much larger field of political meanings. Democratic anti-communism sees itself as self-protection, resistance and countermeasures against communism. On the communist side, the term is used to delegitimize opponents and class enemies .

As a historical and political phenomenon, anti-communism does not represent a uniform worldview or ideology. Crucial and detached from seemingly national identities were social and economic forces that were able to bundle their interests under the umbrella term anti-communism. In addition, there were religious convictions (e.g. Catholicism ) or political ideas or currents in opposition to communism (e.g. social democracy , liberalism and conservatism ).

History of origin

German pre-March 1815–1848

With the emergence of socialist and first communist ideas in the 19th century, political counter-movements emerged. During the so-called Vormärz between 1815 and 1848, the emerging workers' movement increasingly adopted ideas formulated in socialist terms, which aroused the fear of the destruction of the given social and political order among representatives of the bourgeoisie and aristocracy .

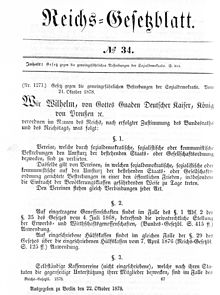

These early forms of anti-communist ideology and politics developed parallel to the founding of the first socialist parties and reached their first climax as a countermovement to the Russian Revolution of 1917. Radical currents that gave rise to armed uprisings provided bourgeois governments with a concrete cause as early as the end of the 19th century in order to combat the broad socialist labor movement as a whole with appropriate means. In France , during the suppression of the June uprising in 1848 and the victory over the Paris Commune in 1871, workers were massacred. In this way, in Thiers ' words, “civilization” was defended. In Germany, the fear of the bourgeoisie of the ' fourth estate ' and the radical sections of the labor movement largely determined its behavior during the revolution of 1848/49, and later - after the establishment of the empire - it was reflected in the socialist laws of Reich Chancellor Otto von Bismarck .

German Empire 1871–1918

See: Socialist Law

October Revolution 1917

The seizure of power by the Bolsheviks in the Russian October Revolution and the massive repression of political opponents that resulted from them led to the Russian civil war between the Red Army and the White Army , which was supported by a heterogeneous group of conservatives, democrats, moderate socialists, nationalists and monarchists. Foreign intervention forces (such as German " Freikorps " units) also took part. Already shortly after the October Revolution there was a large-scale intervention by Allied troops in order to nip the revolution in the bud if possible. In the summer of 1918, for example, there were 13,000 members of the US Army in Russia with the American North Russia Expeditionary Force and the American Expeditionary Force Siberia .

Anti-communism also played a role in Western countries. The anti-communist wave in the United States during and after World War I is known as the Red Scare . The American attorney general Alexander Mitchell Palmer fought actual and alleged communists and anarchists in the American trade union movement in the so-called Palmer Raids . In December 1919, 249 “resident aliens” were brought to Russia on board the UST Buford , including Emma Goldman . The red and white terrorism carried out by Bolsheviks and monarchists in the civil war against the other side and against the civilian population was often expanded in the reporting by atrocity propaganda by the warring parties.

Weimar Republic and the time of National Socialism

In 1919, as a reaction to the November Revolution, major industrialists founded the economic association, positioned against the political left, to promote the intellectual reconstruction forces. The lead there was Alfred Hugenberg , who regularly let large amounts of money go through this lock to the DNVP , which had been an ally of the NSDAP and the Stahlhelm since the 1920s . In this way, Hugenberg also financed the decidedly anti-Semitic völkisch-nationalist Pan-German Association that he controlled .

In 1918 the Anti-Bolshevik League was founded by the former youth leader of the center and later German national, then National Socialist Eduard Stadtler . It was headed by a “General Secretariat for the Study and Fight against Bolshevism”. Thanks to support from German industry, she received “more than ample financial resources”. At the suggestion of Hugo Stinnes , on January 10, 1919, a consortium of industrialists and bankers provided the league with coverage of 500 million marks. Its task was to bring together anti-communists, from moderate social democrats to the extreme right, in a “mass and umbrella organization”. Advertisements from the General Secretariat were also published by the central organ of the SPD, “Vorwärts”. It only had a short life and under a different name (“League for the Protection of German Culture”) was then an insignificant association in the 1920s.

In defending the Weimar Republic against its enemies from the right and left, the SPD was in clear opposition to the KPD . Social Democrats responded to the accusation of social fascism raised by the communists since the mid-1920s with the counter- charge of left- wing fascism : In a speech at a Gau conference of the Reich Banner in Esslingen in 1930, the then regional functionary Kurt Schumacher insulted the communists as "red-painted double editions of the National Socialists" and "standing." Armies of Soviet Foreign Policy ”. “Fascism”, according to Karl Kautsky in 1930, was “nothing but the counterpart” of communism, “Mussolini was just Lenin's monkey.” Otto Wels and Rudolf Breitscheid described fascists and communists as “twin brothers” (1931).

For the NSDAP, anti-communism was one of its central ideologems. In his program Mein Kampf , created in 1924 and 1925, Adolf Hitler declared Marxism and Bolshevism as an attempt by the hated Judaism to achieve world domination , which must be fought by all means. In addition, geostrategic considerations about an allegedly necessary living space in the east flowed into his anti-communism. In his speech to the Industrie-Club Düsseldorf on January 26, 1932, he promised the large industrialists present that he would smash the labor movement and campaigned for support for his party. The German business leaders donated large sums of money to finance the NSDAP only after the secret meeting of February 20, 1933 .

In 1936 the Nazi regime and the Japanese military dictatorship merged to form the anti-communist anti - Comintern pact . In the following years almost all non-democratic states in Europe joined: Fascist Italy (1937), the Franco regime that had just succeeded in defeating the republic in Spain (1939), the Hungarian military dictatorship (1939), and the Bulgarian “royal dictatorship” a "Tsar" (1941), the fascist Ustasha regime in Croatia (1941), the clerical-fascist Tiso regime in Slovakia, the anti-Semitic military regime of Ion Antonescu in Romania, Finland, which cooperates with the Nazi regime, its government a coalition of bourgeois-conservative forces with the fascist Patriotic People's Movement was (1941) and occupied Denmark.

Even in the run-up to the German attack on the Soviet Union, the “Guidelines for the Treatment of Political Commissars” (1941) stipulated that Soviet prisoners of war - civil political functionaries and military political “commissioners” - were to be murdered in the knowledge of a breach of international law. This anti-communist "commissioner order" became the "symbol of the inclusion of the Wehrmacht in the National Socialist extermination policy". The vast majority of the German front-line units implemented it willingly. Wehrmacht criminals were expressly guaranteed impunity if they killed "enemy civilians". It is not known how many victims this form of National Socialist mass crime resulted in.

East-West Conflict in the 20th Century

During the Cold War, anti-communism was criticized not only by sympathizers of communism, but also by bourgeois and left-wing liberal intellectuals. Thomas Mann , 1944, for example "[could] not help seeing something superstitious and childish in the horror of the bourgeois world at the word communism, this horror from which fascism lived for so long, the basic folly of our epoch."

On the other hand, there were also numerous prominent (mostly left-wing) intellectuals and cultural workers who justified, played down or at least overlooked obvious human rights violations and crimes in communist states (for example the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre , who was temporarily involved with Maoism sympathized). In some Western countries, the communist parties also succeeded, openly or covertly (for example through front organizations such as the German Peace Union ), in prominent positions in social movements such as the peace movement and in promoting the foreign policy position of the Soviet Union. Raymond Aron called communism "opium for intellectuals", based on the well-known Marx quote about religion as the " opium of the people ".

Finally, some left-wing critics of anti-communism have argued that it is not legitimate to label the totalitarian regimes of so-called real socialism as "communist". The ruling state parties there usually referred to themselves as “communist parties” and cited Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels as the founders of the idea of communism. It is argued, however, that the real communist idea was only implemented fragmentarily in these countries, for example through the expropriation of private ownership of the means of production.

Europe

The Stalinist purges , in which the leadership of the CPSU around the Soviet dictator Josef Stalin executed millions of real or alleged political opponents and which culminated in the Great Terror and the Moscow Show Trials, had little effect on the perception of communism in the Western public. Even during the Second World War, western anti-communism played only a minor role because of the allied war alliance with the Soviet Union against Germany and Italy. It was not until the Cold War that anti-communism intensified in the entire western world, initially due to the rapid western expansion of the Soviet Union through massive annexations during the Second World War. After the formation of the Eastern Bloc after the end of the war, uprisings were suppressed in Soviet satellite states ( GDR 1953 , Hungary 1956 , Poland 1956 and 1980, and Czechoslovakia 1968 ). Part of the sympathy among left-wing figures in Western Europe came to an end when the “Prague Spring” was crushed with tanks in the summer of 1968 , and even further when the Soviet gulag system became popular around 1970. The writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn played a decisive role in this with his work The Archipelago Gulag .

Federal Republic of Germany

The “ fathers of the Basic Law ” wanted the Federal Republic of Germany to be understood as an anti-totalitarian state that was directed against both National Socialism and Communism. The so-called “anti- totalitarian consensus” or “anti-extremist consensus” therefore existed among the social democratic and bourgeois parties, which assumed that the state and the pillars of society were equidistant from all “totalitarianisms” or “extremisms”. Conservatism in particular, which after 1945 had to renounce its traditional skepticism towards democracy, nationalism and anti-capitalism , found ideological replacement for the positions it had abandoned in anti-communism.

Anti-communism had a tradition in the SPD. In speeches in Bremen and Kassel in May 1946, Kurt Schumacher, now head of the SPD's West Office in Hanover, took up the old accusation again and described the communists as "red-painted Nazis". This point of view met with approval within the SPD, especially since numerous members of the East German SPD had fled to the West after the forced unification of the SPD and KPD to form the SED . Among the oppositional Social Democrats who remained in the GDR there were 5,000 arrests or executions such as B. in the case of Günter Malkowski . Willy Brandt declared in 1949 that "today you cannot be a democrat without being an anti-communist." However, "anti-communism ... is not the only characteristic of the democrat."

Anti-communism represented an integrating and stabilizing consensus from the SPD to the far right in the political life of the Federal Republic and prevented political radicalization. He also helped politically implement integration into the West and remilitarization . That is why it is referred to as the “state doctrine” or “state ideology” of the Federal Republic.

The development of this consensus was facilitated by the experiences that the West Germans had made through their flight and expulsion from the former eastern territories of the German Reich , with the Soviet policy , which had been perceived as threatening since the Berlin blockade in 1948/49, and by comparing their own economic policies Performance with that of the GDR (" economic miracle "). Former National Socialists could also feel that they were being addressed, since the anti-communism of the early Federal Republic was linked to an important element of Nazi propaganda . According to the German historian Detlef Siegfried , it formed a "national-specific continuity factor" and a "placeholder for the now compromised anti-Semitism". Anti-communism diverted attention from its own guilt and coming to terms with the past and, with the Soviet Union, provided a new friend-foe scheme. In addition, the external enemy was also projected inward: political views diverging to the left were often delegitimized and persecuted as communist. The social democratic union representative Viktor Agartz , Gerhard Gleißberg , the editor-in-chief of the central organ of the SPD Vorwärts , or the SPD members of the Bundestag Alma Kettig and Arno Behrisch had to find out, but above all the members and supporters of the KPD.

Communist parties and organizations such as the KPD and the FDJ were banned in the 1950s - as was the neo-Nazi " Socialist Reich Party " - because, in the opinion of the Federal Constitutional Court, they represented efforts directed militantly against the constitutional order of the Federal Republic of Germany. Likewise, the promotion of communism through the sale of newspapers and magazines, e.g. B. banned from the GDR , which was part of the camp of the Soviet Union . In connection with the bans of the KPD (August 1956 by the Federal Constitutional Court ) and the FDJ (1951 by decision of the Federal Government of Konrad Adenauer in accordance with Article 9, Paragraph 2 of the Basic Law ), over 10,000 were in the course of the fifties and sixties according to the then applicable political criminal law People sentenced to prison and hundreds of thousands of trials against communists, including those suspected of communism. The number of 6,688 judgments passed against communists between 1951 and 1968 was almost seven times as high as the 999 judgments against Nazi perpetrators. The first Criminal Law Amendment Act passed in 1951, also known as the Blitzgesetze , allowed opponents of rearmament to be imprisoned as "threats", to be observed and to be banned from practicing and performing. More than half a million people were affected by these measures.

As evidence of state anti-communism in the Federal Republic of Germany , in parts of the Federal German public z. B. 1959/1960 also assessed the condemnation of several representatives of the Peace Committee of the Federal Republic of Germany by a special criminal chamber of the District Court of Düsseldorf, whose work was not assessed as an independently found lesson from the war, but as an instrument of the KPD, "which the West German Peace Committee to this end used to prepare the ground for the establishment of a communist regime in the Federal Republic ”. Those who were to be regarded as communists or friends of communists defined politically predominantly and officially and legally only anti-communists.

Anti-communism was also a motive for the attempted murder of Rudi Dutschke in April 1968 in West Berlin . The perpetrator Josef Bachmann , who traveled from Munich to kill Dutschke, shouted to Dutschke before the shots were fired, which seriously injured the victim: "You dirty communist pig!" On January 28, 1972, Federal Chancellor Willy Brandt (SPD) decided and the prime ministers of the federal states or the ruling mayors of the city-states at a conference on "questions of internal security" an agreement on how to deal with "anti-constitutional" applicants for civil servants and employees in the public service. With the provision known as the “radical decree”, professional bans for leftists were introduced in the public service. At home and abroad, this measure was perceived as undemocratic and rejected. For example, a commission of inquiry of the International Labor Organization (ILO), a specialized agency of the United Nations, came to the conclusion that this decree violated the prohibition of discrimination in employment and occupation (1987). A judgment of the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg on the case of a teacher from Lower Saxony who had been dismissed from school because of membership in the DKP (1986) was of particular importance. The court ruled that the release constituted a violation of the right to freedom of expression and association under the European Convention on Human Rights (1996).

The Federal Republic of Germany stood with "state-directed ideological campaigns against communism" as well as with the ban on the Communist Party and with the sanctioning of activities and organization within the political left, which is not categorized as loyal to the state, and is known throughout Europe under the German name "Berufsverbot" the nationalist one-party states in Spain and Portugal and the temporary military dictatorship in Greece - in the European world alone. It represented a largely rejected anti-communist special path.

Greece

During the German occupation of Greece, right-wing groups such as EDES under Napoleon Zervas , Organization X and the security battalions (tagmata asfalias) of the left-wing liberation movement ELAS under Aris Velouchiotis faced each other. After the withdrawal of the Germans, the British Army openly intervened on the side of the Greek central government on December 15, 1944 in the Battle of Athens under General Ronald Scobie on the direct instructions of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and fought against ELAS. According to the Varkiza Agreement , the right-wing royal dictatorship waged a civil war against the Democratic Army of Greece from 1946 to 1949 , supported by Great Britain until 1947 and from March 1947 by the USA under the Truman Doctrine . Countless communists and other leftists perished during the civil war and the “white terror” of the right-wing paramilitaries, as well as the mass executions and internment of tens of thousands in prison camps. In the 1950s, the executions of the prominent communists Nikos Belogiannis and Nikos Ploumbidis sparked international protests. After the murder of the left, but by no means communist, MP Grigoris Lambrakis and the student leader Sotiris Petroulas in 1963 and 1965, respectively, the colonels putsch in 1967, after which the Greek military dictatorship ruled until the parliamentary elections in 1974 .

United States

After the October Revolution in Russia in 1917, fears of communist-motivated activities arose in the USA. Strikes in 1919 fueled these fears ( “Red Fear” ).

After the end of World War II, at the beginning of the Cold War that followed the United States against the Soviet Union , the containment policy with the aim of the spread of communism and Stalinism to prevent or control purposes. In 1945 the House of Representatives set up a permanent committee for un-American activities , which summoned public figures suspected of being communists (such as the writer Bertolt Brecht ) and imposed professional bans. In 1951 a similar commission was set up in the US Senate , mainly under the influence of Senator Joseph McCarthy . After him, this time of anti-communist “witch hunts” is referred to as the McCarthy era . Artists like Charles Chaplin were no longer allowed to enter; his colleagues ( Humphrey Bogart , Lauren Bacall ) demonstrated against McCarthy. The lawsuit against the American couple Ethel and Julius Rosenberg caused a worldwide sensation in the early 1950s. You have been charged and convicted of espionage for the Soviet Union. Although they denied the allegations, both were executed on the electric chair in Sing Sing State Prison in New York on June 19, 1953, despite fierce national and international protests .

The anti-communist hysteria of the McCarthy era ended in the mid-1950s. In terms of foreign policy, the United States remained bogged down in the Cold War. The Kennedy government reacted internally to the construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961 with relief because it defused the Berlin crisis ; outwardly, however, the president condemned the sealing off of West Berlin . In his famous speech in front of the Schöneberg Town Hall on June 26, 1963 (" I am a Berliner "), he declared that the true face of communism was shown in Berlin:

“There are some in Europe and elsewhere who say we can work with the communists. Let them come to Berlin. And there are also a few who say that while it is true that communism is an evil system, it allows them to achieve economic progress. Let them come to Berlin. [The last sentence in the original German] "

When Cuba (after the overthrow of the dictator Batista in Cuba by the guerrilla Fidel Castro ) became increasingly communist after 1959, the Kennedy government reacted irreconcilably. The CIA hired contract killers, some of whom came from American Mafia circles , to murder Castro ( Operation Mongoose ). Although the United States had committed itself in the Rio Pact not to interfere in the internal affairs of the American partner states, in April 1961 a group of anti-communist Cuban exiles led by the CIA attempted to land in Cuba. However, this Bay of Pigs invasion failed miserably. Ten days later, in a public address, President Kennedy denied all secret operations, but reiterated the strictly anti-communist orientation of his government and warned against the further spread of communism:

“Everywhere in the world we are facing a monolithic and ruthless conspiracy that primarily increases its sphere of influence with covert actions - with infiltration instead of invasion, with subversion instead of elections, with intimidation instead of free choice, with guerrillas by night instead of armies during the day . It is a system that has amassed enormous human and material resources to build a tight-knit, highly efficient machine that combines military, diplomatic, intelligence, economic, scientific and political operations. "

The stationing of Soviet nuclear weapons and medium-range missiles in Cuba the following year triggered the Cuban Missile Crisis . In a televised address on October 22, Kennedy threatened nuclear war if the missiles were not withdrawn. This crisis brought the world to the brink of a third world war . The Soviet Union withdrew its missiles from Cuba, the USA later its medium-range missiles from Turkey.

Latin America

Anti-communism was also a key driver of US policy towards Latin America in the second half of the 20th century. During the Cold War , the US feared an expansion of communism ( domino theory ) and, in some cases, overthrew democratically elected governments on the American continent that were viewed as left-wing or unfriendly to US interests. These included the coup in Guatemala in 1954, the coup in Chile in 1973 and support for the insurgents in the Nicaraguan Contra War . In some cases, democratically elected governments were overthrown by coups or staged revolutions that were by no means communist, but rather bourgeois - such as the government of Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala through the CIA operation PBSUCCESS , because this 1954 land reform to the detriment of United Fruit Company had performed.

In 1973 the democratically elected President of Chile, the socialist Salvador Allende , was overthrown by a coup by the right-wing military, followed by a military dictatorship. In the 1970s and 1980s, a large part of the countries of Central and South America was finally ruled by right-wing military dictatorships that were supported and promoted by the USA because of their anti-communist orientation. Washington accepted the massive human rights violations by the regime with approval or even unofficially endorsed them. (see also Dirty War )

In Argentina, for example, there was a pronounced traditional anti-communism based on a combination of Catholicism , Hispanic nationalism and mostly pronounced anti-Semitic features. During the Second World War, large parts of society, especially the military, the church and the elites, advocated an alliance with the Axis powers . This attitude was particularly pronounced among the bestselling author Julio Meinvielle and among the GOU military around Colonel Juan Perón . The refusal to enter the Jewish refugees of the Holocaust and the simultaneous transport of a wave of Nazi war criminals from all over Europe to Argentina, who in the eyes of many churchmen and for Peronism should form an anti-communist elite in Argentina, were characterized by massive anti-communist attitudes. The Tercera Posición , the Peronist "Third Position", pursued an ideology "beyond plutocratic capitalism and Soviet communism , which in its basic features was only too similar to European fascism." (Theo Bruns) Against this background and in anticipation of a third world war soon after the liberation of Europe from National Socialism , the political elite in Argentina developed ideas of Argentina as a third world power. Anti-communism also played a central role in the particularly cruel persecution during the so-called process of the national reorganization of the military from 1976 to 1983. Up to 30,000 people were secretly kidnapped, tortured and murdered as real or alleged left resistance fighters ( subversives ), with anti-communism providing one of the central motives.

This " disappearance " of politically unpopular, mostly left-wing people in " dirty wars " ("Guerra Sucia") became one of the trademarks of the military rule underpinned with anti-communist ideology in many Latin American countries, which is why the name Desaparecidos (the disappeared) for these murdered people originated.

Japan

In 1900, the Ordinance and Police Act ( 治安 警察 法 , chian-keisatsu-hō ) was enacted, which was directed directly against trade unions and workers' organizations in general. Because of this law, the Communist Party of Japan was banned shortly after it was founded. This law was followed in 1925 by the Law on the Maintenance of Public Security , which was directed against left-wing extremists, especially socialists, communists and anarchists. In pursuit of these as a thought crime trends indicated that served Tokubetsu Kōtō Keisatsu - also known as thought police.

After the end of the war, these bans were lifted again by the Allied occupation authorities ( SCAP / GHQ ) under General Douglas MacArthur and parties such as the Communist Party of Japan were allowed again. However, in 1950, the Red Purge was used to purge it. Members of the party and sympathizers were removed from public office and fired from private companies. The purges were not stopped until the end of the occupation through the peace treaty of San Francisco .

literature

- History of origin

- Ulrich Mählert , Jörg Baberowski et al. (Eds.): Yearbook for Historical Research on Communism 2011 (focus: anti-communism), construction, Berlin 2011, ISSN 0944-629X

- time of the nationalsocialism

- Kurt Pätzold : Anti-communism and anti-Bolshevism as instruments of war preparation and war policy . In: Norbert Frei / Hermann Kling (ed.): The National Socialist War . Campus, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-593-34360-6 , pp. 122-136

- Walter Laqueur : Anti-Comintern , in: Survey - A Journal of Soviet and East European Studies , No. 48, July 1963, pp. 145-162

- Cold War period

- Manfred Berg: Black civil rights and liberal anti-communism. The NAACP in the McCarthy era. In: VfZ , Miszelle 51 (2003), issue 3, pp. 363–384 ( issue archive )

- Alexander von Brünneck : Political Justice against Communists in the Federal Republic of Germany 1949–1968 , Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1978, ISBN 3-518-10944-8 (At the same time dissertation at the University of Frankfurt am Main , Faculty 01 - Law, 1976)

- Stefan Creuzberger and Dierk Hoffmann (eds.): "Spiritual Danger" and "Immunization of Society". Anti-Communism and Political Culture in the Early Federal Republic . Oldenbourg, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-486-78104-5 .

- Rolf Gössner : The forgotten victims of the Cold War justice. Displacement in the West - Settlement with the East? , Structure, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-7466-8026-3

- Werner Hofmann : Stalinism and Anti-Communism. On the sociology of the East-West conflict, Frankfurt a. M. 1967

- Klaus Körner : The red danger. Anti-communist propaganda in the Federal Republic of 1950–2000. Konkret, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-89458-215-4

- Jan Korte : Instrument anti-communism. Special case of the Federal Republic. Dietz, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-320-02173-3

- Gesine Schwan : Anti-Communism and Anti-Americanism in Germany. Continuity and change after 1945 . Nomos, Baden-Baden 1999, ISBN 3-7890-6020-8

- Walther Amann: Justice injustice in the Cold War. The criminalization of the West German peace movement in the Düsseldorf trial in 1959/60. PapyRossa, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-89438-341-0 (= PapyRossa-Hochschulschriften , Volume 64)

- Wolfgang Wippermann : Holy hunt: A history of ideology of anti-communism . Rotbuch, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-86789-147-9

- Claudia Wörmann, Die Ostpolitik and the inwardly and outwardly directed transformation of the anti-communist enemy image, in: Egbert Jahn / Volker Rittberger (eds.), Die Ostpolitik der BRD. Drive forces, resistances, consequences, Opladen 1974, pp. 123-134

- Memory politics

- Jan Korte: Federal German Past Policy and Anti-Communism , in: Yearbook for Research on the History of the Labor Movement , Issue I / 1008, NDZ, Berlin 2002ff, ISSN 1610-093X .

Movie

- Enemies of the State - Cold War and Old Nazis Director: Daniel Burkholz , Sybille Fezer (Germany, 2018, 72 min.)

Web links

- Literature on the keyword anti-communism in the catalog of the German National Library

- Wolfgang Buschfort : anti-communism and anti-national socialism, confusion of the terms magazine freedom and law. Quarterly magazine for militant democracy and resistance to dictatorship, 2012/1 + 2

- Bernd Faulenbach : Anti-Communism , in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte , May 3, 2017.

Individual evidence

- ^ Gerhard Göhler / Klaus Roth: Communism . In: Dieter Nohlen (Hrsg.): Dictionary State and Politics . Licensed edition for the Federal Agency for Civic Education , Bonn 1993, ISBN 3-89331-102-5 , p. 291.

- ^ Kurt Marko: Anti-Communism. In: Claus Dieter Kernig (Hrsg.): Soviet system and democratic society. A comparative encyclopedia . Vol. 1: Image theory to the dictatorship of the proletariat . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau / Basel / Vienna 1966, col. 238.

- ^ A b Ernst Jünger , Friedrich Hielscher . Letters 1927–1985, edited and commented by Ina Schmidt and Stefan Breuer, Stuttgart 2005, p. 331.

- ^ Matthias von Hellfeld , European files. History of a Continent, Munich 2006.

- ↑ Gerhard Schulz, Germany since the First World War: 1918–1945, Göttingen 1982, p. 70.

- ^ Björn Laser, Kulturbolschewismus !: On the discourse semantics of the “total crisis” 1929–1933, Frankfurt a. M. [u. a.] 2008, p. 65.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz: The fight against National Socialism before 1933 , in: Federal Center for Political Education (Ed.), Information on Political Education , Issue 243 (2003), online .

- ↑ Willy Albrecht, Kurt Schumacher, Bonn 1985, p. 25.

- ↑ Mike Schmeitzner: Kurt Schumacher's concept of totalitarianism , in: ders. (Ed.): Criticism of totalitarianism from the left. German Discourses in the 20th Century , Göttingen 2004, pp. 249–282, here p. 255.

- ^ Wolfgang Wippermann : Antibolschewismus. In: Wolfgang Benz , Hermann Graml and Hermann Weiß (eds.): Encyclopedia of National Socialism . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1997, p. 364.

- ^ Henry A. Turner : The big entrepreneurs and the rise of Hitler. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 1985, pp. 260-268.

- ^ Agilolf Keßelring, The North Atlantic Alliance and Finland 1949–1961. Patterns of perception and politics in the Cold War , Munich 2009, p. 165.

- ^ Claudia Prinz, Der Antikominternpakt , German Historical Museum , October 15, 2015.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz (Ed.), Handbook of Antisemitism. Anti-Semitism in Past and Present, Vol. 4, Events, Decrees, Controversies, Berlin / Boston 2011, p. 224.

- ^ Bernward Dörner, Mass Violence and Destruction. The war against the Soviet Union as a genocidal intervention, in: Wolfgang Benz (Ed.), Prejudice and Genocide: ideological premises of genocide, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2010, pp. 100–118, here pp. 100 f.

- ↑ Th. Mann, fate and task , 1944, quoted from Klaus Schröter , Thomas Mann , rororo rm 93, p. 182; see also GW XII, 934, EV, 234.

- ↑ Ralf Dahrendorf , Temptations of Unfreedom , Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 978-3-406-57378-1 .

- ^ Theo Schiller: Conservatism . In: Dieter Nohlen (Ed.): Lexicon of Politics, Vol. 1: Political Theories . directmedia, Berlin 2004, p. 666.

- ↑ Mike Schmeitzner : Criticism of totalitarianism from the left. German Discourses in the 20th Century , Göttingen 2007, p. 255.

- ↑ Half-lazy solution: The grand coalition improves the victim pensions for victims of the GDR regime after severe criticism . In: Focus 24/2007, p. 51.

- ^ Helga Grebing : History of ideas of socialism in Germany, part II. In: the same (ed.): History of social ideas in Germany: Socialism - Catholic social teaching - Protestant social ethics. A manual. 2nd edition, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2005, p. 384.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte, Vol. 5: Federal Republic of Germany and GDR 1949–1990. CH Beck, Munich 2008, pp. 15 and 236; Volker Möhle / Christian Rabe: Conscientious objectors in the FRG. An empirical-analytical study on the motivation of conscientious objectors in the years 1957–1971 . Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1972, p. 131.

- ↑ Karl Dietrich Bracher , quoted from: Hans Karl Rupp (Ed.): Die other BRD. History and Perspectives , Marburg (Lahn), p. 17; so also: Hans-Gerd Jaschke : Disputable Democracy and Internal Security. Basics, practice and criticism. Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1991, p. 94.

- ↑ Hermann and Gerda Weber: Life according to the “left principle”. Memories from five decades . Ch.links, Berlin 2006, p. 54.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte, Vol. 5: Federal Republic of Germany and GDR 1949–1990. CH Beck, Munich 2008, p. 22 ff., 157 and 245.

- ↑ Detlef Siegfried: Time is on my side: Consumption and politics in the West German youth culture of the 1960s , Göttingen 2006, p. 187.

- ↑ Stephan Buchloh: "Perverse, harmful to young people, subversive". Censorship in the Adenauer era as a mirror of the social climate , Frankfurt am Main / New York 2002, p. 301.

- ↑ Federal Gazette No. 124 of June 30, 1951.

- ↑ Numbers and a. Alexander von Brünneck, FaM 1979, but without evidence, somewhat more recently also Rolf Gössner, Berlin 1998, p. 26.

- ↑ Josef Foschepoth : The role and importance of the KPD in the German-German system conflict , in: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaft 56 (2008), issue 11, pp. 889–909, here p. 902.

- ↑ Half a million public enemies , taz from October 19, 2012.

- ↑ See Heinrich Hannover, die Republik vorgericht, Berlin 2005, quotation on p. 78.

- ^ New Germany of December 24, 2009.

- ↑ All information in this section: Friedbert Mühldorfer, Radikalerlass , in: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns , June 16, 2014. Accessed November 23, 2016.

- ↑ Detlef Siegfried, Time is on my side: Consumption and Politics in West German Youth Culture in the 1960s, Göttingen 2006, p. 187.

- ^ Manfred Görtemaker : History of the Federal Republic of Germany. From the foundation to the present . CH Beck, Munich 1999, p. 363 f.

- ^ "There are some who say, in Europe and elsewhere, we can work with the Communists. Let them come to Berlin. And there are even a few who say that it is true that communism is an evil system, but it permits us to make economic progress. Let them come to Berlin. “ John F. Kennedy: Ich bin ein Berliner (" I am a 'Berliner' "), delivered June 26, 1963, West Berlin on the website americanrhetoric.com, accessed on November 30, 2013.

- ^ "We are opposed around the world by a monolithic and ruthless conspiracy that relies primarily on covert means for expanding its sphere of influence - on infiltration instead of invasion, on subversion instead of elections, on intimidation instead of free choice, on guerrillas by night instead of armies by day. It is a system which has conscripted vast human and material resources into the building of a tightly knit, highly efficient machine that combines military, diplomatic, intelligence, economic, scientific and political operations. " John F. Kennedy:" Address "The President and the Press "Before the American Newspaper Publishers Association, New York City.," April 27, 1961. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley on the American Presidency Project website , accessed November 30, 2013; Stephen G. Rabe: The Most Dangerous Area in the World. John F. Kennedy Confronts the Communist Revolution in Latin America . University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1999, p. 127.

- ^ Jorge G. Castaneda: Latin America's Left Turn. In: Foreign Affairs . 2006, archived from the original on October 7, 2008 ; accessed on March 9, 2018 .

- ^ Benjamin Schwarz: Dirty Hands. The success of US policy in El Salvador - preventing a guerrilla victory - was based on 40,000 political murders. Book review on William M. LeoGrande: Our own Backyard. The United States in Central America 1977-1992. 1998, December 1998.

- ↑ Peter Kornbluh : CIA Acknowledges Ties to Pinochet's Repression , September 19, 2000

- ^ Argentine Military believed US gave go-agead for Dirty War. National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book, 73 - Part II, CIA Confidential Documents, published 2002

- ^ Uki Goñi : Odessa. The true story. Escape aid for Nazi war criminals. Berlin / Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-935936-40-0 . See also the overview by the Goñi translator Theo Bruns, in: Ila 298 ( online ).

- ^ Theo Bruns: Mass exodus of Nazi war criminals to Argentina. The largest escape aid operation in criminal history. In: ila 299 ( online ).

- ^ Uki Goñi : Odessa. The true story. Escape aid for Nazi war criminals. Berlin / Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-935936-40-0 .

- ^ Matthias Reichelt : "Finally have peace and quiet". A documentary about the blind spot in the FRG: »The enemies of the state - Cold War and old Nazis« , new Germany, February 3, 2020