Austrian German

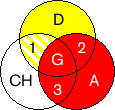

Austrian German , synonymous with Austrian high German and Austrian Standard German , is in Austria common variety of High German default language . Like the other two national standard varieties , Swiss Standard German and West German German , it emerged from the Saxon language of the office .

This replaced the previously used Upper German writing language in Austria no later than 1774 with the introduction of compulsory teaching and in a further step from 1780 with the introduction of the new official language , as Maria Theresa and her son Joseph II opposed the Bavarian- and Alemannic-speaking Austrians actually decided on a closer Upper German writing language. This happened in particular at the instigation of the Austro-Moravian writer Joseph von Sonnenfels . The approach was more pragmatic than puristic, which means that Austrian peculiarities have been retained and become part of the standard, even if, on the other hand, place names are even rewritten according to the actual pronunciation according to the rules of the Saxon law firm (e.g. Schwöchat → Schwechat , Gleinstötten → Gleinstätten ) or vice versa, the sound has been adapted to the new written language (e.g. Bavarian [ i ] to Saxon [ y ] as in Windische Pihel → Windische Bühel ).

Like the other two national standard varieties, Austrian German has a specific vocabulary ( see: List of Austrianisms ), specific idioms (e.g. Krot have to swallow ) and special features in grammar , pronunciation (both phonology and intonation) and Spelling (as far as the 1996 reform allows) and is also statistically characterized by the absence or rarer occurrence of certain elements of German used outside of Austria. The Austrian Standard German is the colloquial delineate and customary in Austria Bavarian and Alemannic dialects.

The Austrian dictionary , co-initiated by the Austrian Ministry of Education and binding for schools and offices in Austria , similar in function to the Spelling Dude, has documented the vocabulary of the German language in Austria since 1951.

General

The peculiarities of the standard Austrian language have different origins. Some terms and numerous peculiarities of pronunciation come from the dialects and regional dialects common in Austria ; others were borrowed from non-German-speaking crown lands of the Habsburg monarchy . Austrian legal and administrative terms as well as grammatical peculiarities go back to official German in the Habsburg Empire (after 1804: Austrian Empire ; after 1867: Dual Monarchy Austria-Hungary ), whose origins Joseph von Sonnenfels had significantly influenced from 1784.

In addition, an important part of the special Austrian vocabulary includes the culinary area; only 23 of these terms from the field of agriculture are protected by treaties with the European Community so that EU law does not force Austria to use foreign German-language terms.

In addition to the high-level standard variety, there are also numerous regional dialect forms in Austria , especially Bavarian and Alemannic dialects . These are used very heavily in colloquial language , but apart from the influences mentioned above, they are not directly reflected in the written language (except for dialect poets, musicians).

Austrian German shows the pluricentric property of the German language , a typical feature of rich-speaker languages that are spread across national borders. However, there are Plurizentrik the German an ongoing development and discussion process in the German language , which is open until represented the monocentric of the Germans in the 1980s ( domestic German ) and the 1952/1953 initiated concept of pluricentric language has only since been developed and refined.

That is why the term Austrian German is not without controversy, but it is used by the majority of leading linguists in Austria.

This discussion process in German studies is therefore presented below in the final section on linguistic discussion . In any case, a current linguistic overview by the German linguist Jan-Hendrik Leerkamp stated in 2003: “In research, the existence of an independent national variety of Austrian German seems to be largely recognized.” ( Jan-Hendrik Leerkamp ).

In Austria , a tourist destination with a high proportion of holidaymakers from Germany, some of the terms that originated there were regional or in certain industries when dealing with customers or in general (additionally). In language maps it can sometimes be noticed that terms skip large areas and appear in Carinthia or - which is close to Austria - South Tyrol.

historical development

18th century

In the 18th century, the old Austrian linguist Johann Siegmund Popowitsch researched the differences between the German spoken and written in the Austrian hereditary lands and other parts of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation . Popowitsch was a Slovenian from Lower Styria ; from 1753 to 1766 he was professor of the German language at the University of Vienna and an opponent of Gottsched , who standardized the German language according to the Meissen language usage . Up until the 18th century, Upper German writing was predominant in the Habsburg territories and in Catholic southern Germany , but then quickly disappeared in favor of the “Protestant” standard German, which goes back to Luther .

When he died in 1774, Popowitsch left behind an extensive box of notes from which the first Austrian dictionary should have emerged.

During the time of Maria Theresa and Joseph II , the Austrian enlightener and writer Joseph von Sonnenfels , professor at the University of Vienna , was committed to the standardization of the language and the reduction of linguistic diversity in the administration of the multiethnic state (albeit with a pragmatic, enlightening approach delimited from Gottsched's mechanical-puristic approach ). In 1784, when Joseph II tried to establish the German language as the general official language, Sonnenfels created a standard work with his book Über den Geschäftsstil: the first basic lines for budding Austrian clerks , which was authoritative at Austrian universities (especially law faculties) until 1848:

“The declared aim of the textbook was to standardize the language of the administration in such a way that it would be used uniformly throughout the large multiethnic state, so that an official who was suddenly transferred to a new place of work (a very realistic consideration) would be able to do so to continue working as before without additional training. In expressly differentiating it from the linguistic purism of a Gottsched, Sonnenfels did not focus on a uniform standard German language, but raised, through and through, pragmatically oriented, general intelligibility as the primary goal of language use by the state administration. Empty phrases and rhetorical pomposity should be eliminated as far as possible, brevity, conciseness and clear structure of the explanations were the highest maxims, whereby Sonnenfels expressly advocated not being based on an abstract ideal of linguistic purity, but instead using the vocabulary of the common language, if possible serve. With this, his influential textbook finally became an essential starting point for the general establishment of the Austrian standard variety of the German language. "

Joseph II's attempt to establish German as the sole official language (also in Hungary) failed for the time being; on the other hand, the reforms initiated by him and his mother Maria Theresa took effect in the educational system, especially in the higher educational institutions where civil servants were trained. The multilingualism was both an opportunity and a threat to the entire state, so that the civil service of the Habsburg Monarchy was consciously trained in the sense of a supranational overall state consciousness .

From March to the First World War

The civil servants thus formed their own social class and were part of the intellectual bourgeoisie in Austria . Many officials even worked as writers and thus also had an effect on the higher language usage outside the official system. The most prominent example of this is the Austrian court official and playwright Franz Grillparzer , who, however, was accused by critical contemporaries of too much ingratiation towards the ruling house because of his Habsburg dramas (including a brotherly quarrel in Habsburg , King Ottokar's luck and end ).

After the dissolution of the German Confederation in 1866 and the reorganization of the entire monarchy as Austria-Hungary in 1867, the area of tension between Austrian German and “German language purism” increasingly came to light. The 1st Orthographic Conference in Berlin in 1876 did not reach an agreement on a uniform all-German orthography. As a result, in 1879 the usual written language habits in Austria were codified as rules and vocabulary for German spelling .

Due to the common administrative body and the cultural exchange in the Austrian Empire and the dual monarchy Austria-Hungary, numerous loanwords from Czech, Hungarian, Italian, Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian etc. have been incorporated into Austrian German.

Austria since 1918

In the course of the adoption of the Austrian Federal Constitutional Law (B-VG) in 1920, the constitutional legislature at the time established the German language (without further specification) in Article 8 paragraph 1 B-VG as the official state language . The later added Art. 8 Abs. 2 B-VG also recognizes the native minority languages in Austria :

"Article 8 B-VG

(1) The German language is, without prejudice to the rights granted to linguistic minorities by federal law, the state language of the republic.

(2) The republic (federal, state and local authorities) is committed to its growing linguistic and cultural diversity, which is expressed in the autochthonous ethnic groups. Language and culture, existence and preservation of these ethnic groups are to be respected, secured and promoted. "

Today around 88% of the Austrian population have German as their mother tongue .

Characteristics of today's Austrian German

Differences to Federal German Standard German

The Austrian German differs in parts of the vocabulary, grammatical peculiarities, the spelling and also in the pronunciation from the standard German , which is codified in Germany by the Duden . The Duden denotes 0.4% of all words as Austrian. Current German developments were taken into account. Austria took part in the reform of German spelling in 1996 , but without giving up its linguistic peculiarities, which is taken into account in the Austrian dictionary in its 43rd edition.

“Austrian German was particularly described and characterized by Austrian, but also partly by German and non-German German linguistics. In its written form, it is particularly characterized by peculiarities in the vocabulary mainly as designations and more rarely also by meanings (onomasiological and semasiological peculiarities) and to a lesser extent by morphological peculiarities in the formation of forms and words including the genera of the noun, syntactic and phraseological as well pragmatic peculiarities. Orally, there are also particularities of pronunciation with sound formation and word accentuation. "

Robert Sedlaczek also affirms the position of Austrian German as a language variety:

"It goes without saying that Austrian German and German German are not two different languages. In both cases, they are varieties of the [...] pluricentric German language."

Influences of the Danube Monarchy and Yiddish

Austrian German was and is influenced by the other languages of Central Europe, especially those of the former crown lands, e.g. Czech , Hungarian , Slovenian , Italian . The influence of the Jewish bourgeoisie, especially in Vienna and Prague, as well as Eastern Jewry until 1938 is reflected in the increased use of Yiddish expressions.

Similarities with old Bavaria

Part of the vocabulary of the Austrian standard language is also anchored in the central and southern Bavarian dialects and is therefore occasionally used in the other Bavarian language areas in old Bavaria (e.g. roast beef), but other Austrian words are also unknown in Bavaria (e.g. Rescue , slap ).

Change of language layer

In the linguistic presence of Austrian German one can very often observe a change in language layers. Colloquial words and dialect terms are repeatedly incorporated into high-level sentences. Conversely, individual stressed words are expressed in high-level language for emphasis within the colloquial language.

This is not done as an ingratiation to the respective other language level, but serves a stylistic nuance and expansion of the possibility of expression. It is not a mixture, but rather shows the knowledge of the respective other language layers and their everyday meaning - mainly because the same words can often have different meanings in the other language layers.

This change of language layer can also be found very frequently in Austrian literature ( Karl Kraus : Die last Tage der Menschheit , Arthur Schnitzler etc.), in the Austrian press (less and less), but also as part of “ Burgtheaterdeutsch ”, which has long been typical Austrian standard language reference par excellence, but due to the inclusion of actors from other German language regions in the ensemble, this theater is no longer spoken throughout.

Use differences in individual forms of language

Studies have shown that in Austria forms of language are accepted in formal contexts that are unusual in Germany because they appear too informal. Joachim Grzega describes this feature of Austrian German as nonchalance . Even in written language such as newspapers, quotations with elements of colloquial language are more likely to be used, while in Federal German indirect speech with "smoothed" language is used.

Personal names

In Austria (similar to the neighboring Slavic languages), but also in Bavaria, the designation name is mostly not used for the surname, but for the combination of first and last names or just for the first name.

sequence

In some contexts in Austria, but also in Bavaria, there is a tendency to use the format (ARTICLE) SURNAME FIRST NAME. This corresponds to the general practice in Hungarian. Example: (the) Huber Mitzi and (the) Gruber Franz corresponding to (az) Orbán Viktor and (a) Petőfi Sándor .

title

Salutation using job titles, titles and academic degrees is much more common in Austria than in Germany, where such forms are handled very differently and depending on the language group. In German schools and universities, for example, academic additions to names, at least in oral communication, are considered out of date and are now generally avoided in dealings between people of different ranks (students - university professors) and between people of equal rank and are addressed as "Mr." or "Ms." followed by the surname. The addition of "Dr." to the name in the oral address is mostly restricted to doctors.

In Austria, additions to names are a matter of course in work and everyday life and the status relationships expressed as a result are part of social interaction. As in Germany, not only the name suffixes "Dr." and "Prof." are used, but also "Mag." (Pronounced "Magister"), "DI" or "Dipl.-Ing." (Pronounced "Diplomingenieur") . In schools, it is common to use addresses such as “Mr. Teacher” (elementary school) or “Mr. Professor” (secondary school), while in Germany such verbalizations of status relationships are perceived as unpleasant formulations of subservience and are used ironically, if at all. The husband's name suffixes are rarely transferred to the wife. On the other hand, it is customary to leave out the name after the title and is by no means casual or impolite. Even if additions to names are just as unlikely to be part of a name in Austria as they are in Germany, omitting them is perceived as impolite in some circles. Omitting the title when you become more familiar is also rather unusual, here you tend to switch to first name and salutation. The Bologna reform with its subsequent academic degrees such as MSc and PhD seems to result in a gradual move away from name additions in the long term.

The importance of academic titles in the address can be found in Austria as well as in other successor states of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, without prejudice to decades of socialist social order. According to Muhr, the use of titles in Austria reflects ongoing “ corporatist structures ” and socio-psychologically “a considerable degree of acceptance of government and authority”. Ehlers, on the other hand, warns against over-interpreting the use of the title, described as “fossilized”, as the sole indication of cultural or mental differences between Germany and Austria. As such a relic, the phenomenon is sometimes the subject of (self-) ironic to folkloric consideration and the resulting stereotyping.

Vocabulary in Austria

Austrian official and legal German

The so-called Austrian official German goes back in part to the Habsburg Monarchy .

In the following, Austrian expressions from the field of administration and politics are listed, along with the respective equivalent in Germany:

- the act = the act

- to leave an office = to resign from an office

- the swearing-in = the swearing

- Asylum seekers = asylum seekers

- Conditional imprisonment = probation

- keep in evidence = note

- Identical, obsolete for transcription

- Club = parliamentary group (in parliament )

- Club chairman = chairman of the parliamentary group

- Party traffic = office hours (at an authority)

- tenancy = civil servant (transfer to civil servant status)

- sequester (only in use in South Tyrol) = confiscate

- map = destroy files

- urge = urge a decision

- violated = cannot be found at the moment (got into the wrong file pile)

Likewise, expressions are used in the legal language and in Austrian legislation that e.g. B. do not occur in Germany, have a different meaning (e.g. possession) or are uncommon. Likewise, soft legal terms - often due to the adopted by the legislature terminology - for example in detail from the usual in Germany, makes the same expressions from (in Austria: damages for pain and suffering, according to the. General Civil Code in 1811 , also in the Liechtenstein Civil Code ; in Germany: Damage s replacement , Pain s money).

In general, a more frequent use of Latinisms in legal language can be observed in Austria , which is mainly due to the fact that the German Civil Code, which was created shortly before 1900, deliberately avoided the Latin legal expressions from Roman law ( pandects ) that were previously widespread in Germany or " Germanized ". Examples are expressions such as Legat (legacy), Servitut (easement), Causa (case; but in Germany means "legal reason"), Kuratel (today derogatory for guardianship) or Krida used only in Austria or more often than in Germany .

When it comes to the ranks of the Austrian Armed Forces , differences to the names in the German Armed Forces are particularly pronounced below the officer level. Examples are the ranks of corporal (Germany: Hauptgefreiter / Stabsgefreiter ), Wachtmeister (replaced the " Feldwebel " designations in Austria in 1919 ; in Germany until 1945 in artillery and cavalry , in the East German NVA until 1970 in artillery) , Vice Lieutenant (highest NCO rank, corresponding to the Oberstabsfeldwebel of the Bundeswehr) or Brigadier (D: Brigadier General ). Commanders (D: commanders of troop units) are always commanders in Austria (in D. they are commanders of fixed places (barracks, military hospitals, etc.) and vehicles (tanks, ships)). This is also reflected in other organizations, so that there is no group leader in the fire brigade as in Germany, but a group commander , and in the Red Cross there is a column commander .

Day care center is official for kindergarten (everyday language) , the terms “ day care center” and day care center , which are common in Germany, are unusual or even unknown in Austria.

In the traffic sector, a traffic light system in Austria has a completely different meaning than in Germany. The traffic light in both countries is called a traffic light system in Austria (VLSA: traffic light signal system), while the traffic light system indicates an unrestricted level crossing. In the transport is the official name hauliers for a carrier .

School system

In the school sector, after elementary school (Germany: elementary school , formerly and occasionally also elementary school in Bavaria) there are three types of secondary school, namely the new middle school , which roughly corresponds to the German secondary school, the secondary school (expiring) and the grammar school , which has different forms , which are referred to with the umbrella term Allgemeinebildende Höhere Schule (AHS). The Matura in Austria corresponds to the Abitur in Germany. Representation hours suppliert , grade entries as well as in southern Bavaria collated .

In mathematics lessons, it is not the faculty but the factorial that is calculated, the side symmetry is built instead of the vertical line and there is more talk of the rhombus instead of the rhombus . The parallelepiped replaces the spatula and the deltoid the dragon square . The tetrahedron is more common than the tetrahedron. Powers are (similar to, for example, in Czech, but obsolete in Austria) instead of the high n with the nth . The Federal German term three is completely unknown, this bill is called the final bill.

The German War becomes the Austro-Prussian War.

Month names: January, February and February

The term used in Austria for the first month of the calendar year is January . January is officially used and January is uncommon in almost all areas. Jänner corresponds to the Middle High German jenner , which in turn originated from the late or vulgar Latin form Iēnuārius .

January was widespread in the entire German-speaking area until the second half of the 18th century, but was then replaced by the form January until around 1800 - with the exception of the southern German-speaking area - which in turn is an endless variant of the Latin Iānuārius . From a New High German point of view , January is an inherited word from Middle High German (because it was integrated into the corresponding sound change processes), whereas January - also in New High German - is a Latin loan word (because it was phonologically and morphologically adapted to the New High German system, but since its borrowing has not yet gone through any significant sound change processes typical for the current form of speech).

The situation is different with the term Feber for the second month of the calendar year. Here in the German vernacular, the term was Hornung usual, but then the path of humanistic firm language from the Latin word foreign Februarius was ousted, which then as February or in the Central German and Upper German as February was a loan word.

A form corresponding to the Hornung tribe is unlikely to be found in Austria today on the basilectal and mesolectal level (and thus in local dialects and regiolects ). Shapes that correspond to February are often used . February is the standard language ; However, the older form Feber can be found in office language (e.g. on official documents) and colloquial , such as on parking tickets or entries in the Austrian passport.

Kitchen vocabulary

On the occasion of the referendum in Austria on joining the European Union in June 1994, the Mayor of Vienna Helmut Zilk had "Potato salad remains potato salad" posted on large posters with political relevance, which made the tension between " national identity - EU identity" clear on linguistic issues. In the accession treaty, Austria placed 23 names under protection in “Protocol No. 10 on the use of specifically Austrian expressions in the German language”.

Below are some examples from the Austrian kitchen language, initially the Austrian variant:

- Beiried - roast beef or rib

- Chanterelle - Chanterelle

- Egg dish (s) - scrambled eggs

- Erdapfel - Potato (both terms in Austria)

- Minced meat - minced meat

- Fisolen - green beans (both terms used in Austria)

- Germ - yeast

- Cooking salad - romaine lettuce

- Horseradish - horseradish

- Kukuruz - maize (both terms used in Austria)

- Apricot - Apricot

- Obers , Rahm (also in Germany) - cream

- Paradeiser - tomato (both terms used in Austria)

- Beetroot - beetroot

- Sour cream (also in Bavaria) - sour cream

- Semmel (also in Bavaria) - bread rolls

- Plugs (also in Bavaria) - Quark

Weight designations

For food, the term 1 deca (gram) , abbreviated dag, formerly dkg, is used instead of 10 grams (analogous to the other successor states of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, cf. in Italian the hectogram un etto = 100 g = 10 dag). For example, the order is 10 Deka extra sausage and not 100 grams of meat sausage .

The hundredweight is used in Austria and southern Bavaria for a unit of weight of 100 kg, in Germany for 100 pounds (50 kg). The terms quintals for 100 kg and pounds for half a kilogram, which are used in large parts of Germany, are unusual in Austria.

Austrian brand names

The economy also plays a role in Austrian German, where, for example, individual brand names have become Austriancisms. The brand name is used today for the tape mostly TIXO used for thin pretzel sticks Soletti for Schokoküsse Sweden bombs , for cleaning cloths Wettex , for pressure cookers Kelomat and sometimes for orange juice Cappy and apple juice for Obi .

Medical terms

In the medical field one also comes across Austrian technical terms. Austrian doctors operate an ordination (German Standard German: practice or consultation hour). A chief physician is different in Austria than in Germany: The German chief physician is called Primar (ius) in Austria ; The Austrian chief physician, on the other hand, is a controlling physician of the health insurance company, who receives notarizations for sick leave and issues permits for special prescriptions, medication and medical aids. There is also still, but no longer reassigned, the dentist . In Germany, a regular doctor is the doctor doing an internship . For numerous injuries and illnesses there are local names, not just dialect-based, such as cold and wet leaves . Instead of X-ray they say in Austria also röntgenisieren , choke is also located verkutzen , hiccups called the Austrian Schnackerl (encounter) , the gag reflex (in the throat) "it stretches me." When the Austrian speaks of the foot, as in southern Germany, the leg can be meant (analogously hand instead of arm). So when someone says they have broken their foot, in Austria they usually think of a lower leg fracture rather than something that has happened on the foot in the narrower sense.

Names of numbers, letters and characters

numbers

Numbers as nouns are generally formed on -er in Austria and are then masculine. In Austria it is called the ones , where elsewhere mostly the one is the predominant form. The use of the number two for two to clarify the difference to three in high-level announcements (e.g. at train stations) is rarely used in Austria, in contrast to Germany, with the exception of the Austrian Armed Forces, the fire brigade and the police, where instead of "two" “two” is always used in order to avoid confusion with three when listening - which, however, is usually perceived as “typically military” and takes some getting used to by outsiders. If necessary, the Bavarian variant zwoa / zwà fulfills this function in everyday life .

The ordinal number is traditionally “the seventh” instead of “seventh”. This form is not only used in Austria, but can also be found in Germany. The form "seventh" is now also common in Vienna, both in the spoken and in the written language:

"Those who cannot afford the Seventh or Eighth, but do not want to do without big city flair, move to the Third - and always live 'near the Rochusmarkt'."

Decimal fractions (example π = 3.14): Instead of “three point one four”, “three point fourteen” is spoken in Austria and southern Bavaria, and occasionally “three whole fourteen”.

Letters

The Austrian names of the letters J and Q differ from those in Germany and Switzerland: J = "je" (D and CH: "jot"); Q = "kwee" (in mathematics and in Germany and Switzerland: "ku"). In addition, sch in Austria is sometimes spelled “schee” or “esch” instead of “es-ze-ha”. These spelling habits correspond to those of the neighboring Slavic languages (e.g. pronunciation in Czech) and have a long tradition in Austria, such as the following quotations from the textbook "Instructions to speak, read and write the German language correctly." Year 1794 show:

“J, j (iodine, beſſer Je ). The j is softer than ch. It is mostly at the beginning of the words: yes, year, someone. The capital letter J denotes the self-vowel in un the common vowel j. "

“Q, q (Ku, beſſer Kwe ). Q is always followed by v and both letters are pronounced like kw: source, torment, comfortable. "

“Sch, ſch (Esceha, beſſer Sche ). This letter, composed of three letters ſ, c, h, has only one single sound, which is contained in a full sign: ſchaben, waſchen, der Menſch. "

In addition, it is common in Austria, but also in large parts of Switzerland and southern and western Germany, to refer to ß as a sharp S and not as Eszett. Austrians usually understand Eszett to be the sequence of letters sz and not the single letter ß. There is also a long tradition here:

“The ß (Eßzet, beſſer das sharpened Es ) reads a little bit sharper than ſ, but a little less than ſſ, and ehtehet after a stretched self or double lute, if the sour sound remains sharpened in the curve and derivative: big, the big, bigger , ſſſ, But if the ß takes the place of the ſſ, ſo must also be pronounced doubly sharpened: Hate, ugly, he eats, measures, from haſſen, eſſen, meſſen. "

Punctuation marks

The punctuation marks , and ; In Austria, in contrast to Germany and Switzerland, a comma (if in the text) and a semicolon are used. This also has a long tradition:

“The Beyſtrich (,). This sign must be followed in the shortest possible time with the voice.

The dash (;). It shows a slightly longer resting point than the Beyſtrich. "

Time

In eastern and southern Austria in particular, 2:15 p.m. is not referred to as a quarter past two , but rather as a quarter past two or, as is primarily found in Salzburg, Upper Styria and Upper Austria, as a quarter past two . Also 14:45 rarely than two forty-five , rather than three-quarters of three designated. However, the expressions "quarter three" and "three quarter three" are also widespread in the southern German, eastern central German and northeastern German language areas and are therefore not the only Austrian feature.

The variant quarter XY + 1 , half XY + 1 , three quarters XY + 1 for XY: 15 , XY: 30 and XY: 45 is still used in the other languages of the Danube Monarchy. In addition, the spelling ¼4 , ½4 and ¾4 was common in the newspapers of the Danube Monarchy :

| Ö-German | Czech | Slovenian | Hungarian | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15:15 = ¼ 4 | quarter four | čtvrt na čtyři | četrt na štiri | negyed négy |

| 15:30 = ½ 4 | half past three | půl čtvrté | pol štirih | fél négy |

| 15:45 = ¾ 4 | quarter to four | tři čtvrtě na čtyři | tričetrt na štiri | háromnegyed négy |

| 16:00 = 4 | four | čtyři hodiny | štiri | négy |

Grammatical peculiarities

Word formation (composition and fugues)

Between the elements of compound nouns ( word composition ) in Austrian German (in contrast to Federal German ) there is often a fugue such as the fugue-s , e.g. B. "Zugsverpätung" or "Schweinsbraten" (German for "Zugverspätung" or "Schweinbraten"). The fugue-S is also often used in compound participles , e.g. B. "constitutional". This fugue-S is often misinterpreted as genitive . On the other hand, the Fugen-S does not appear in some cases, contrary to the usage in Germany, e.g. B. "Advent calendar" instead of "Advent calendar", "compensation" instead of "compensation", "pain compensation" instead of "pain compensation" (the latter only legal ).

In Austrian German, apart from the fugue, there is also a fugue in other word compositions that do not occur in federal German, for example in the Austrian stopping ban (official designation in laws, etc.) compared to the official German stopping ban .

Conjugation: 2nd person plural -s

The second person plural is, as in parts of the southern German-speaking area, in the present and perfect tense with the ending -ts in order to distinguish it more clearly from the third person singular, especially if the personal pronoun is omitted (Habt s (ihr) das seen?) . Behind this -s is the personal pronoun és [eˑs], an old dual form that has been merged with the personal ending . In some parts of the Bavarian dialect area, this personal pronoun also exists as an independent word.

Modal verbs: perfect

In Austria, in the perfect formation of the modal verbs, no distinction is made between “I have not been able to” (federal German. “Able to”) and “I have not been able to do it”. The same applies to may / may , want / wanted , should / should and must / must .

Past participle: -et and -en

In the Austrian as well as southern Bavarian usage, the past participle of the once strongly conjugated verbs switch (schaul, schalten) and spalten (plays, split) is alternatively used with the historically older ending - (e) n instead of the newer ending - (e) t educated. Analogous to this, there are also these variants of the verb salt .

Examples:

- switch - switched - switched opposite switch - switched - switched . For example: The television is switched on. = The television is switched on .

- split - split - split opposite split, split, split

- salt - salted - salted versus salt - salted - salted

Conversely, in Austria the verb hauen and its derivatives such as abhauen almost exclusively use the weak conjugation with the ending -t :

- cut - cut - cut opposite cut - cut - cut or he is cut away opposite he is cut away

Furthermore, it is in Austria, the verb waving addition to the weak participle waved the strong variant waved normative more accepted than in Germany:

- waving - waving - waving opposite waving - waving - waving

The two variants have existed side by side for a long time and wunken could not be eliminated despite long-lasting school intervention, as evidenced by the mention in the school grammar of Popowitsch (1754) in comparison to today's Austrian dictionary, which waved accepted as a variant without further comment:

"Waving is a regular verb, I waved, I waved, not, I waved ."

"Wave; waved / waved ( also: waved ) "

In contrast, carries waved in for Germany by many as largely respected the Duden qualifier particularly colloquially :

"Perfect formation with" has "; 2nd participle waved, also, especially colloquial: waved "

Perfect: to have and to be in positional verbs

In Austria (as well as in German-speaking Switzerland and in the entire southern German-speaking area), “sein” is generally used as an auxiliary verb (also in high-level language) for the formation of the perfect tense of verbs that express posture, as well as for verbs of movement . The verbs concerned include, for example:

- "Sit" ( sit - was sitting , but: incarcerated (in jail) - have sat )

- "Stand" ( stand - have stood , but: confess - have stood ),

- "Lie" ( lie - I lie )

and in parts of Styria and Carinthia colloquially:

- "Sleep" ( sleep - have slept ).

This fact was already attested by Johann Siegmund Popowitsch in his school grammar from 1754:

“Lying, I was lying, I was lying jacérem ; I was lying, lying. In the Hochteutſchen you don't say , I was lying . "

“Sizen, I ſass ſedebam , you ſaßſt, he ſass; we ate, ye ate, they ate; I ſäſſe ſederem , I am geeen, ſiz. "

“Stand, you ſ stand, he stands; I ſt and, I ſt tarem , I am tand , ſteh. "

On the other hand, sleep :

“Sleep, you sleep, he sleeps; I slept, I slept, I slept. "

Past tense / imperfect tense

As in the entire dialect area south of the Speyer line (Appel / Apple line) , the past tense , also called past tense in Austria, is rather uncommon in Austrian colloquial language. “I went” or “I saw” is perceived as strange, only the verbs sein and want are used in the past tense. It is normal to say: "I went" or "I saw". In the written language, however, the past is used.

The past tense died out in the Upper German dialects in the early New High German period. One explanation for this is that in Upper German generally the final "-e" u. a. In the past tense, the result was "-te": "says-e"> "says", "buys-e"> "buys". As a result, the past and present tenses of many verbs could no longer be distinguished acoustically, which is said to have led to the simple past tense being out of use. According to another theory, the past tense was given up in favor of the synthetic subjunctive , or was superseded by it.

Furthermore, in contrast to the rest of Europe, it is common in all Alpine languages to form the main past time as a compound tense; Austrian German shares this phenomenon not only with the whole of southern Germany, but also with Czech, Slovak, Slovenian, Serbo-Croatian, French and the north of the Italian-speaking area.

Use of the subjunctive

In Austria, as in Germany, the indicative is used for indirect speech in everyday language . If a sentence is actually spoken in the subjunctive I, it expresses distrust in Austria.

Example: He said he was in town. In contrast: he said he was in town. - expresses that you actually don't believe it.

However, this does not apply to all media, in some the subjunctive is used as in Germany.

The subjunctive itself is used more as an unrealis . (For its formation, see the grammar section of the article Bavarian language .)

Gender (gender)

The assignment of nouns to one of the three genera varies slightly between the standard varieties of German. To illustrate the special features of the Austrian standard language, examples are given here, with the Austrian variant mentioned first:

- the bar - the bar (in Switzerland and Germany)

- das Brösel - the Brösel (in Germany with the exception of the southeast)

- das Puff - the Puff (in Germany with the exception of the southeast)

- die Schneid - der Schneid (in Switzerland and Germany with the exception of the southeast)

A different gender has also been established in some cases when adopting foreign words, examples:

- das Cola - the Cola (in Switzerland and Southeast Germany also neuter in use)

- das E-Mail - the E-Mail (in Austria and Switzerland both forms are used)

- das Keks - the biscuit (neuter in Austria)

- the service - the service (both forms are in use in Austria)

- the spray - the spray (in Germany in addition to the form in neuter in use)

In the dialects, as in the other German-speaking countries, there are numerous differences to the regional standard language, in this case the Austrian, which in some borderline cases also cause gender variations in this standard language. Examples of this are in Austria:

- the butter - the butter (also in old Bavaria)

- the radio - the radio (for the radio receiver; also in old Bavaria)

- the plate - the plate

- the onion - the onion (you can even find it in the supermarket on the price tag; also in old Bavaria)

- der Schok (o) lad '- the chocolate (corresponds to the French form le chocolat , also male; also in old Bavaria)

Numbers, especially school grades, are in the south of the German-speaking area, e.g. B. in Bavaria, Austria, Switzerland, male: the ones , the five , otherwise female: the one, the six.

Idioms, collocations

There are also differences in the use of prepositions to indicate times or places.

| Austria | Germany |

|---|---|

| buy something for five euros (also in Bavaria, pushed back in written German) |

buy something for five euros |

| " Am " as a short form for on the (colloquial; also in old Bavaria): on the mountain, at the opera ball, at the table (e.g. in "the food is at the table") | on the (coll. auf'm ) mountain, on the table |

| go on vacation (also old Bavaria) | in going on vacation |

| in going to school | also: go to school |

| at work (also southern German) | on or at work |

|

at Christmas, Easter (also in southern Bavaria) |

at (more in the south) or at (more in the north) Christmas, Easter |

When using verbs, there are differences in alternative meanings.

| Austria | Germany |

|---|---|

| to go somewhere (coll. also in Bavaria) | also: run somewhere (in Austria almost only used for "run, hurry") |

| attack (in the sense of "touch", e.g. "do not attack my cell phone") | touch (is understood as very upscale in Austria) |

| go out (e.g. "this thing won't work out"; coll. also in Bavaria) | some create something just reached (in time), go and fit (for. example, "this thing is / already fits"), rise (eg. as "not going to") |

| to lose one (e.g. "I'm missing you", "I've been losing wine since I've had it on my liver"; coll. also in Bavaria) | miss something , one is missing (e.g. I miss you, I miss you) |

| forgot something (e.g. "I forgot about your birthday") | sweat a bit , neglect (e.g. "I sweaty your birthday") |

Notation

There are some differences in the spelling even after the spelling reform . Instead readily , for example, in Austria without further preferred.

Some words are spelled differently due to pronunciation; For example, the Austrian-South German variant Geschoss (with a long o ) in contrast to the West German Geschoss or the Austrian Kücken instead of the West German Chick .

Austrian pronunciation and the sound system

The Austrian pronunciation and the sound system ( phonetics and phonology ) contain numerous national characteristics.

Allophone in Austrian German

General note on voicing plosives and fricatives

The following regularities can be determined for the voicing in Austrian German:

Initially / # CV / lose

- / b / ( e.g. the ribbon = [tas pant]),

- / d / (ex .: the roof = [tas tax]),

- / g / (ex .: the gold = [tas ko̞lt]) and

- / s / (Ex .: the sun = [ti so̞nɛ])

generally their voicing. This does not apply to / b /, / d / and / g / for some speakers from parts of Carinthia.

In the intro / VCV / the voicing is weakened or is completely lost, i.e. that is, the following sounds vary from weakly voiced to unvoiced.

- / b / (ex .: the gift ),

- / d / (ex .: the ark ),

- / g / (ex .: the scales ),

- / s / (ex .: the nose )

It follows that the distinction between ‹s› on the one hand and ‹ß› as well as ‹ss› on the other hand in Austrian German is often not made on the basis of differences in voicing, but rather on the basis of other characteristics, such as the relative length of time and the intensity the friction (envelope curve-shaped noise caused by eddies in the air flow, i.e. the characteristic that defines fricatives such as [f] or [s])

Voicing is generally lost in the final / C # / or before voiceless consonants .

Plosives

Based on the largely missing distinction in Middle Bavarian between the consonants "p" and "b", "t" and "d" and (to a lesser extent and only regionally) "k" and "g", the so-called lenization , these consonants sound the same for many speakers. The endings on -ig are usually pronounced as such (it is said, for example, Kings ik or fert ik and not as mostly common in Germany Kings I , fert I ). For the ending -ig , two separate rules were therefore defined in the spelling of 1996, which is based on the spoken language, which merge both spoken variants into one written one (both - [iç] and - [ik] result in written -ig ) .

aspiration

The aspiration of plosives, which is common in West German German, rarely or not at all occurs in Austrian German: [p] instead of [pʰ] , [t] instead of [tʰ] . Solely / k / is often realized as [kʰ] . Example: an espresso please!

Nasals

In Austrian German there is a strong tendency towards syllabic nasals and nasal plosives (in the English-language terminology nasal release ), in which the nasal part forms the syllable apex. This occurs especially with the ending -en . With nasal plosives, the rupture of the seal does not occur on the lips or tongue, but on the velum, so that the oral seal remains. The airflow therefore goes through the nose and not through the mouth as would be the case with non-nasal plosives. The place of articulation is determined by the preceding plosive or fricative. Examples of Nasalplosive: clips [ 'klupᵐ] , Ties [kra'ʋatⁿ] , Frittaten [fri'tatⁿ] . Examples of syllabic nasals: health insurance companies ['kraŋʔŋ̩ˌkʰasn̩] , monkeys [' afn̩] or ['afm̩] etc.

Liquid

Vibrants

The Vibrant / r / can be realized with the tip of the tongue [r] as well as uvular [ʀ] . Example: Rose ['roːsɛ] is equivalent to [' ʀoːsɛ] .

Lateral approximants

As with the nasals, Austrian German tends towards the syllable / l /. The articulation location of / l / is also adapted to the preceding plosive or fricative. Examples: Kugel ['kuːɡɫ̩] , apple [' apfl̩] , strudel [ʃtruːdl̩] .

Vowels

Vowels are generally more tense in Austrian German than in German German.

Schwa lute

Instead of the Schwa sounds [ə] (for / -e /) and [ɐ] (for / -er /), which are common in German German, a short [ɛ] or a short [a] , ie for <Mitte> ['mitɛ] instead of [' mɪtʰə] and for <Winter> ['ʋinta] instead of [' vɪntʰɐ] .

Loanwords

Many loan words differ in emphasis and pronunciation from use in other German-speaking areas, such as no nasalization in concrete, season (also with -ei-) pronunciation with / k / of Chemistry, China , different emphasis on Kaff ee , Mathem a tik , tab a k, Telef o n, A nis, Plat i n .

In Austria the phoneme / s /, which is reproduced as <s> in German orthography, is almost consistently pronounced voiceless. This sometimes leads to confusion among Austrian phrasebook readers who use examples like “S as in sun” to explain voiced pronunciation.

Furthermore, many Austrians do not speak the "st" and "sp" in some Latin, Greek, French or English words as "scht-" or "schp-", but as "st-" and "sp-", e.g. B. Standard, statistics, specific (but for example: special always spoken with "schp-"). Spurt is often used with English pronunciation. Loan words from French such as Chance are almost always pronounced in French.

In the control o r , a difference to the federal German inspector is also marked in spelling.

Often the pronunciation examples given here are not limited to Austria, but can also be found in southern Germany (especially Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg) (e.g. the quoted pronunciation of chemistry , China , telephone ).

In Austria, brand names are usually adopted in their original pronunciation. "Germanizations" like in Germany with Michelin or Colgate rarely take place.

Reception abroad

A study published in 2006 by the Austrian linguist Jutta Ransmayr among German teachers and students in the United Kingdom , France , the Czech Republic and Hungary showed that the Austrian language variant is considered a dialect . As a result, Austrian German is seen by teachers in Western Europe as “second-rate, old-fashioned or faulty” , while it is still taught in Central European countries such as the Czech Republic. Cause of both phenomena is loud Ransmayr that the last language export of Austria at the time of kuk occurred -Monarchie. In 2010 the German publisher Langenscheidt published a 1,440-page “Austrian English Dictionary” for the first time, which also contains around 2,000 Austrianisms.

Linguistic discussion

There is an ongoing development and discussion process on the question of pluricentric language in German studies, which until the 1980s was characterized by a "monocentric conception" (" internal German ") and has only developed and refined the concept of the pluricentric language since then. That is why the term Austrian German is not undisputed, but is represented and supported by the majority of leading linguists in Austria, although there are also critical expert opinions on this in Germany and a few in Austria.

In the following, the ongoing discussion and its leading representatives are presented, in the spirit of the Viennese Germanist Wiesinger :

“Both extreme points of view, which one could describe as Austrian-national and German-integrative, do not do justice to the actual Austrian language situation. In view of these divergences, what is necessary is a sober, factual relationship to the German language, which is also valid in Austria, in its specific variety as Austrian German. "

Viewpoints of Austrian Linguists

Within Austria, the following linguists in particular pursue the discourse on the term Austrian German (ÖD), whereby the standpoints range from the rejection of any independence of the Austrian linguistic usage to the attempt to define one's own "Austrian language", so that Leerkamp chooses the safe middle ground and writes: " In research, the existence of an independent national variety of Austrian German seems to be widely recognized. "

- Austrian linguists - Pro ÖD

- For the term Austrian German and its correct use in German studies , the following are (or were) in particular:

- Jakob Ebner, Adalbert Stifter Institute of the State of Upper Austria, Linz

- Hermann Möcker, Institute for Austrian Studies; Austrian dictionary

- Rudolf Muhr , Karl Franzens University Graz , Institute for German Studies

- Rudolf de Cillia, University of Vienna , Institute for Linguistics

- Wolfgang Pollak , University of Vienna, Institute for Romance Studies, died in 1995

- Richard Schrodt, University of Vienna, Institute for German Studies; Austrian member of the Council for German Spelling

- Ruth Wodak, University of Vienna, Institute for Linguistics

The majority of the linguists mentioned took part in the international conference “Austrian German” at the Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz from May 22nd to 24th, 1995. The extensive publication Austrian German (cited in the introductory part) is from the contributions of this conference . Linguistic, social-psychological and language-political aspects of a national variant of German. (Ed. Muhr - Schrodt - Wiesinger, Vienna, 1995), as well as a joint resolution to the Austrian Federal Ministry for Education and Cultural Affairs. In addition, numerous books and publications on Austrian German have appeared, in particular:

- Austrian German and other national varieties of pluricentric languages in Europe. (Ed. Muhr - Schrodt, Vienna 1997, materials and manuals on Austrian German and German as a foreign language 3 ).

- Austrian German (Robert Sedlaczek, Verlag C. Ueberreuter, 2004).

- The status of Austrian German at non-German speaking universities. An empirical study (Jutta Ransmayr, Peter Lang Verlagsgruppe, Frankfurt am Main, 2006)

- Austrian Linguists - Critical to ÖD

- Critical to the term Austrian German as an independent national variety were expressed:

- Heinz-Dieter Pohl , University of Klagenfurt , Institute for Linguistics and Computational Linguistics: For example in his article Austrian Identity and Austrian German for the Carinthian Yearbook for Politics 1999 , in which he strongly links his linguistic positions with the question of the Austrian nation and identity. The later publications show a change in position and a clearer recognition of Austrian German as a standard variety, albeit not as a purely national standard variety, but rather as a subgroup of the southern German standard variety. He therefore announced a newer (summarizing) publication on this question in 2007, since, according to him, his criticism of Austrian German does not refer to the Austrian national variety as such, but to ideological interpretations of Austrian language usage. He strongly advocates a conscious use of the Austrian language, but rejects the concept of an Austrian “language” favored by Muhr.

- Hermann Scheuringer, University of Regensburg

- Ingo Reiffenstein, University of Salzburg , emer. Professor of older German language and literature

There are also reviews of Austrian German in article form.

See also

literature

- Dictionaries

- Christiane M. Pabst (Red.), Magdalena Eybl (Mitarb.) Et al .: Austrian Dictionary . Published on behalf of the Federal Ministry for Education, Science and Research . Complete edition with the official regulations. 43rd, updated edition, öbv , Vienna 2018, ISBN 978-3-209-10546-2 (with the spelling changes, based on the proposals of the Council for German Spelling 2017).

- Jakob Ebner : Austrian German. Dictionary of contemporary language in Austria . Ed .: Duden. 5th, completely revised and enlarged edition. Dudenverlag, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-411-04985-1 (previously in the 4th edition, 2009, as: How do you say in Austria? Dictionary of Austrian German, ISBN 978-3-411-04984-4 ) .

- Ulrich Ammon , Hans Bickel , Alexandra N. Lenz (Hrsg.): German dictionary of variants . The standard language in Austria, Switzerland, Germany, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, East Belgium and South Tyrol as well as Romania, Namibia and Mennonite settlements . 2nd, completely revised and expanded edition. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-11-024543-1 .

- Oswald Panagl , Peter Gerlich (Hrsg.): Dictionary of political language in Austria. öbv, Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-209-05952-9 .

- Langenscheidt editors: Langenscheidt Austrian English dictionary English-German / German-English . Langenscheidt, Berlin 2010, ISBN 3-468-11391-9 .

For dictionaries with the main focus on dialects, see German dialects in Austria and the sub-articles.

- Single publications

- Ulrich Ammon: The German language in Germany, Austria and Switzerland: The problem of national varieties. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1995.

- Michael Clyne: The Austrian national variety of German in a changing international context. (1993).

- Birte Kellermeier-Rehbein: Pluricentric. Introduction to the national varieties of German. Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-503-15550-7 .

- Jan-Hendrik Leerkamp: The Austrian variety of the German language , LINSE (Linguistik-Server Essen), 2003 ( PDF, 29 pages ).

- Rudolf Muhr , Richard Schrodt (Ed.): Austrian German and other national varieties of pluricentric languages in Europe. Vienna 1997.

- Heinz-Dieter Pohl : Austrian Identity and Austrian German . In: Kärntner Jahrbuch für Politik 1999 : pp. 71–103.

- Wolfgang Pollak : What do Austrians think of their German? A linguistic and sociosemiotic analysis of the linguistic identity of Austrians. (1992, Vienna, Austrian Society for Semiotics / Institute for Sociosemiotic Studies.)

- Gregor Retti: Austrianism in dictionaries. To the internal and external code of Austrian German. Phil. Diss. Innsbruck 1999.

- Richard Reutner: The dispute over words. Notes on Austrian German in the 18th century. In: Austria in History and Literature 4, 2001, pp. 240–249.

- Robert Sedlaczek : The Austrian German. Ueberreuter, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-8000-7075-8 .

- Peter Wiesinger : The German language in Austria. An introduction. In: Wiesinger (Ed.): The Austrian German. Writings on the German language. Volume 12, Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Graz 1988.

- Peter Wiesinger: Austrian German in the present and history. 3rd edition, Lit Verlag, Vienna / Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-8258-9143-5 .

- Astrid Wintersberger: Austrian-German Dictionary. Residenz Verlag, 1995, ISBN 3-7017-0963-7 .

- Ruth Wodak : We are not Duden-Land . In: Wiener Journal, June 1994, pp. 26-27.

- Edited volumes and publication series

- Rudolf Muhr, Richard Schrodt, Peter Wiesinger (Eds.): Austrian German - Linguistic, social-psychological and language-political aspects of a national variant of German (PDF, 407 pages) , Vienna, 1995, Verlag Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky (contributions from international linguists - Conference “Austrian German” at the Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz from May 22nd to 24th, 1995).

- - Richard Schrodt: The concept of language between grammar and pragmatics: What is Austrian German? 1995.

- Austrian German series - language of the present. Rudolf Muhr, Richard Schrodt (Eds.), Peter Lang Publishing Group:

- Volume 3, Heidemarie Markhardt: Austrian German within the EU. 2005, ISBN 3-631-53084-6 .

- Volume 7, Heidemarie Markhardt: Dictionary of Austrian legal, economic and administrative terminology . 2006, ISBN 3-631-55247-5 .

- Volume 8, Jutta Ransmayr: The status of Austrian German at non-German-speaking universities. An empirical study. 2006, ISBN 978-3-631-55242-1 .

- Volume 10, Rudolf Muhr, Manfred Sellner a. a .: Ten years of research into Austrian German: 1995–2005. A balance sheet. 2006.

media

- Austrian German on the radio. A series of programs in cooperation with Radio Helsinki May 17 - June 28, 2008. Online: radio.oedeutsch.at , Austrian German Research Center, Karl-Franzens-University Graz.

Web links

- Online dictionaries

- Dictionary German – Austrian , as well as the Austrian dictionary derived from it

- Lexicon dialect of the Austrians 1811

- (Upper) Austrian-German dictionary from the University of Linz

- The Austrian Folk Dictionary

- materials

- Jakob Ebner : Duden - Austrian German - An introduction by Jakob Ebner with a foreword by the Duden editorial team, Mannheim, in spring 2008 (52 pages pdf; 651 kB), accessed on November 14, 2009

- Heinz Dieter Pohl: On Austrian German , Small Culinary Lexicon

- Robert Sedlaczek : Homepage of the book Das Österreichische Deutsch , weekly column in the Wiener Zeitung

- Online pronunciation collection to listen to

- SpeechDatWeb: Online pronunciation database. Research Center for Austrian German, Graz

- Other web links

- What language has to do with identity on ORF

- Austrians are all bilingual on ORF

- German for residents: only retreat battles

- On the (language of) Carinthian and Austrian cuisine

Individual evidence

- Entry on Austrian German in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

- ↑ On the definition and linguistic demarcation in particular: Rudolf Muhr, Richard Schrodt, Peter Wiesinger (Eds.): Austrian German - Linguistic, social-psychological and linguistic aspects of a national variant of German (PDF, 407 pages; 1.3 MB) , Verlag Hölder- Pichler-Tempsky, Vienna 1995. Note: This publication is the result of the contributions to the “Austrian German” conference , which took place with international linguists at the Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz from May 22nd to 24th, 1995.

- ↑ This internal relationship of the standard varieties of the German language can be compared with the relationship between French and its geographically close varieties such as Belgian French or Swiss French (where there are differences in pronunciation as well as vocabulary variations, best known for the numerals 70 and 90 as well as in Switzerland also with the number 80), even if France pursues a rigid language policy with the Académie française .

- ↑ See Peter von Polenz: German Language History from the Late Middle Ages to the Present , Vol. 3, Walter de Gruyter, 2000, ISBN 3-11-014344-5 , p. 419 ff .: The Germanist Elise Riesel, who emigrated from Vienna in 1934, began in In accordance with international linguistic developments, from 1953 the term “national variant” was applied to Austria, Germany and Switzerland. In West Germany, Heinz Kloss suggested the “pluricentrist language” approach from 1952, which in turn had taken over the term from the US sociolinguist William A. Stewart.

- ↑ The Australian linguist Michael Clyne from the University of Melbourne was an international leader in the development of the concept of “pluricentric language” , cf. Michael Clyne: Language and Society in the German Speaking Countries. (1984) and Michael Clyne: Pluricentric languages. Differing norms in different nations. (Berlin / New York 1992) and especially Michael Clyne: The Austrian National Variety of German in a Changing International Context. 1993.

- ↑ In Germany itself, the Germanist Ulrich Ammon in particular has published on this question, cf. u. a. Ulrich Ammon: The German language in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. The problem of national varieties. Berlin / New York 1995.

-

↑ On the question of the definition of terms for Austrian German cf. Hans Moser: West Austria and the Codification of “Austrian German” (1995): “The term 'Austrian German' can be defined in two ways: either as the totality of all those linguistic forms of expression that claim nationwide validity and the standard language in Austria differ from that of other German states or regions (Schibboleth definition) or as the totality of language forms that belong to the standard (somewhere) in Austria or are close to it, with or without equivalents outside of Austria. ”

The Austrian dictionary follows this definition, not that. - ^ A b Jan-Hendrik Leerkamp: The Austrian Variety of the German Language , LINSE - Linguistik-Server, Essen 2003 (PDF, 29 pages) , p. 9.

- ↑ A. Bach: History of the German language. §§ 173, 174 importance of firm language: In addition to the firm languages and the language of Luther's writings remained the Upper Saxon home space for hosting the nascent NHG standard language long of importance ... The Meissen was the guiding principle from the spoken, even more for that. Written German.

- ^ Robert Sedlaczek: The Austrian German. Verlag C. Ueberreuter, 2004 ( introductory chapter PDF ).

- ↑ Peter Stachel (Austrian Academy of Sciences): A state that perished from a speech defect. The "multilingualism" of the Habsburg Empire and its effects. (PDF; 288 kB) In: Johannes Feichtinger, Peter Stachel (Hrsg.): The tissue of culture. Cultural studies analyzes of the history and identity of Austria in modern times. Studienverlag, Innsbruck 2001.

- ^ Hermann Lewi: The Austrian Standard German. Attempt to expose its most salient errors and flawed peculiarities. Bermann and Altmann, Vienna 1875.

- ↑ See Peter Wiesinger: Das Österreichische Deutsch , 1988, as well as in a row u. a. Leerkamp 2003.

- ↑ "Austrians are all bilingual" orf.at of March 16, 2016.

- ^ A b Peter Wiesinger: The Austrian German in discussion. 1995.

- ^ Robert Sedlaczek: Das Österreichische Deutsch 8, ISBN 3-8000-7075-8 .

- ^ Friedrich Torberg : The aunt Jolesch .

- ^ Salcia Landmann : The classic jokes of the Jews , Ullstein, Berlin 1997: There were so many languages in the Danube Monarchy that nobody could speak them all. Fortunately, there were Yiddish-speaking Jews throughout the vast empire. So Yiddish finally became a kind of lingua franca for all those who - like the officers - had to change their domicile frequently. (P. 15)

- ↑ Ada (Atlas of everyday German language), University of Augsburg: Fugenelemente Rinderbraten / Rindsbraten

- ^ Ada (Atlas of everyday German language), University of Augsburg: Ambulance / Rescue

- ^ Ada (Atlas of everyday German language), University of Augsburg: Flat tire on the bicycle

- ↑ Joachim Grzega: Nonchalance as a feature of Austrian German. In: mother tongue. 113 (2003): pp. 242-254.

- ^ Klaas-Hinrich Ehlers: Salutation in primary school. On the recent development of addressing behavior in Germany. Journal for German Linguistics, 37 (2) - Sep 1, 2009

- ^ Klaas-Hinrich Ehlers: On the address with titles in Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic. Results of a questionnaire survey. In: bridges. Germanistic Yearbook Czech Republic - Slovakia 2004 , NF. 12, pp. 85-115

- ↑ Reinhard Dippelreither: Oh, this Austrian !: A cheerful and entertaining look at the language of our neighbors. Foreign speaker, Conrad-Stein-Verlag

- ↑ Thomas Wagner: Servus, Mr. Magister. University globalization overtakes Austria. Deutschlandfunk, Campus and Career 2007, (online)

- ^ Klaas-Hinrich Ehlers: On the address with titles in Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic. Results of a questionnaire survey. In: bridges. Germanistic Yearbook Czech Republic - Slovakia 2004 , NF. 12: 85-115

- ^ Rudolf Muhr: Pragmatic Differences in German-Language Communication - Austria: Germany. In: ders. (Ed.): International works on Austrian German and its neighbors-language references. Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky, Vienna 1993, pp. 26–38

- ↑ Ephraim Kishon: Viennese Waltz title. (on-line)

- ↑ Miriam Bandar: Mr. Hofrat and Mrs. Magister. manager magazin online, 2008

- ↑ Christoph Weissenböck: Title-horny Austria - When the forgotten “Magister” becomes a stumbling block for applications in the Alpine republic. Career blog Svenja Hofert, 2010. (online)

- ↑ A comprehensive description of the terms of law, administration and economy as well as other public sectors can be found in Markhardt 2006.

- ↑ Kluge's Etymological Dictionary of the German Language states: As early as the early New High German period, the late Latin variant Ienuarius was taken over into the form January , which is still valid today in terms of landscape.

- ↑ Potato Salad and Jam War. Austrian German and language policy in the EU. (PDF) A conversation between the Viennese linguist Rudolf de Cillia and Monika Obrist in January 2010. In: Gleanings. Website of the South Tyrolean Cultural Institute , accessed on December 7, 2019.

- ↑ Protocol No. 10 on the use of specifically Austrian expressions in the German language within the European Union, Annex. 1 (= Federal Law Gazette No. 45/1995 , p. 2544), as amended in the Federal Legal Information System (RIS).

- ↑ “Austrian German” only exists in the EU in culinary terms. Book is dedicated to the 23 officially anchored expressions. In: Der Standard , February 12, 2005, accessed on December 7, 2019. With regard to: Heidemarie Markhardt: The Austrian German within the framework of the EU (= Austrian German - language of the present; Volume 3). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 978-3-631-53084-9 .

- ^ Rudolf de Cillia : "Victory in the Jam War". Protocol No. 10 ten years later. In: Alwin Fill, Georg Marko, David Newby et al. (Ed.): Linguists (don't) only talk about it. Essays in Honor of Bernhard Kettemann. Stauffenberg, Tübingen 2006, ISBN 978-3-86057-635-9 , pp. 123-139 (PDF; in: Austrian German as a language of instruction and education, FWF project (P 23913 – G18). University of Vienna , accessed on 7 December 2019).

- ↑ Entry "seventh, seventh, seventh" at duden.de , accessed on April 20, 2019.

- ^ Wien-Landstrasse: The district around the Rochusmarkt. In: DiePresse.com. July 3, 2015, accessed December 31, 2017 .

- ↑ a b c d e Instruction to speak, read and write the German language correctly. Grätz, in the publishing house of the official bourgeois bookbinders, and printed with Leykam'ſchen fonts. 1794.

- ↑ Designation "ß" . In: Atlas of everyday German language. Université de Liège and University of Salzburg, January 9, 2011. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- ↑ Werner König: dtv-Atlas German language. 15th edition. Munich 2005, p. 232 f.

- ^ A b c d e Johann Siegmund Val. Popowitsch: The necessary beginnings of the German language art for the use of the Austrian schools. Vienna 1754. To be found with the two Grundt brothers, middle-class bookbinders. P. 380

- ↑ waving in the dictionary

- ↑ Werner König, dtv-Atlas German language , Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1998 (12), p. 162.

- ^ Robert Sedlaczek: Das Österreichische Deutsch , 446, ISBN 3-8000-7075-8 .

- ↑ The whole section is based on the presentation in Ulrich Ammon et al .: German dictionary of variants. The standard language in Austria, Switzerland and Germany as well as in Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, East Belgium and South Tyrol. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2004

- ↑ Cola in the Duden

- ↑ E-Mail in Duden

- ↑ Biscuit in Duden

- ↑ Service in the Duden

- ↑ Zwee, zwou, zwoa - the black ones, own rules also apply to numerals

- ↑ See Joachim Grzega: Observations on German-Austrian divergences in Anglicisms , in mother tongue 110 (2000): pp. 238–248.

- ↑ Jutta Ransmayr: The status of Austrian German at non-German-speaking universities. An empirical study. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 2006, ISBN 978-3-631-55242-1 .

- ^ Austrian English dictionary

- ↑ The assignment of pro and contra positions of Austrian linguists to Austrian German (ÖD) as a national variety can be found in particular with Richard Schrodt: National variants, areale differences and the “substandard”: An den Quellen des Österreichischen Deutschen , 1997. Die This classification is also quoted and adopted by the ÖD critic Pohl himself in his contribution to the Carinthian Yearbook for Politics 1999 . Likewise, the German linguist Leerkamp makes a similar classification in the article from 2003 mentioned above (Strictly speaking, however, there should be an increase after “Pro”, namely the category “Öst. Sprachwissensch. Per independent language Austrian ”. However, this is actually about individual opinions that have not yet found acceptance in the scientific community).

- ↑ See the list of publications by Jakob Ebner ( Memento from May 5, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) according to the German Institute of the University of Vienna.

- ↑ On Muhr's point of view, cf. In addition to his numerous publications, in particular the Austrian German research group he set up at the German Institute of the Karl Franzens University in Graz ( Memento from February 5, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Wolfgang Pollak: What do Austrians think of their German? A linguistic and sociosemiotic analysis of the linguistic identity of Austrians. (1992, Vienna, Austrian Society for Semiotics / Institute for Sociosemiotic Studies)

- ^ Richard Schrodt: The concept of language between grammar and pragmatics: What is Austrian German? 1995. Quote: "In this sense, there can be no doubt that Austrian German must be seen as an independent variety of an overall language 'German'."

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Ruth Wodak: We are not Duden-Land. (1994).

- ^ Heinz Dieter Pohl: Review of the book by Jutta Ransmayr .

- ↑ Heinz-Dieter Pohl: Review of the book Das Österreichische Deutsch - How we differ from our big neighbor by Robert Sedlaczek .

- ^ Institute for German Studies, University of Vienna .

- ↑ Martin Putz: "Austrian German" as a foreign language? Critical considerations , in: GFL-Journal (German As a Foreign Language, among other things supported by the German Goethe Institute), Edition 3 from 2002, pp. 48–76.