torture

Torture (also torture or torture ) is the targeted infliction of psychological or physical suffering (pain, fear, massive humiliation) in order to blackmail statements, to break the will of the torture victim or to humiliate the victim. The UN Convention against Torture evaluates any act as torture, in which state violence persons “deliberately inflict, allow or tolerate severe physical or mental pain or suffering, for example in order to blackmail a statement in order to intimidate or punish” a person. Torture is a widespread practice despite worldwide ostracism. Those responsible are usually not held accountable.

Legal situation

International law provisions

Various international legal provisions contain a ban on torture.

Article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) of the United Nations states:

"Nobody should be subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment."

Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) of the Council of Europe and Article 4 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union express it in a similar way :

"Nobody should be subjected to torture or inhuman or degrading punishment or treatment."

Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment of December 10, 1984 ( UN Convention against Torture ), Part I, Article 1 (1):

“For the purposes of this Convention, the term 'torture' means any act by which a person is deliberately inflicted great physical or emotional pain or suffering, for example in order to obtain a testimony or a confession from him or a third party in order to actually do it for him or to punish an offense allegedly committed by her or a third party or to intimidate or coerce her or a third party, or for any other reason based on any kind of discrimination, when such pain or suffering is caused by a civil servant or another in person acting in an official capacity, at their instigation or with their express or tacit consent. The term does not include pain or suffering arising solely from, belonging to or associated with legally permissible sanctions. "

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights of the United Nations is not a directly applicable law. On the other hand, the European Convention on Human Rights can be sued by all citizens of the 47 states of the Council of Europe directly at the European Court of Human Rights . Since the ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon - with the exception of Great Britain and Poland - EU citizens have also had the opportunity to sue the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union before the European Court of Justice.

Further bans on torture under international law can be found in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Art. 7 IPbpR and in the United Nations Convention against Torture . The prohibition of torture is of an absolute nature, from which it is not allowed to deviate even in emergencies, cf. Art. 15 para. 2 ECHR, Art. 4 para. 2 IPbpR.

Legal situation

Germany

In the law of the Federal Republic of Germany, a prohibition of torture is constitutionally anchored in Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the Basic Law and in Article 104, Paragraph 1, Sentence 2 of the Basic Law:

" Human dignity is inviolable."

"Detained persons may not be mentally or physically ill-treated."

Since the forceful enforcement of a change of will of a person always means a violation of this person's dignity and the forced imprisonment of a person against his will for the purpose of an involuntary change of will constitutes mental abuse, the German laws that provide for such forced imprisonment may, after Germany's accession to the UN Convention against torture are no longer applied.

After all, the ban on torture is secured by various provisions of German criminal law and criminal procedure law in simple law. For example, Section 357 of the German Criminal Code prohibits superiors from tempting their employees to commit illegal acts or even to tolerate such acts . Just as § 340 StGB bodily harm in office is a criminal offense. Furthermore, statements that are blackmailed under the threat of torture cannot be used in court proceedings ( Section 136a StPO ). Also § 343 of the Criminal Code extortion of statements is a criminal offense ( malpractice ). However, torture is not a separate criminal offense.

The legality of the so-called rescue torture has not yet been clarified by the highest court and is controversial in the legal literature.

Austria

The prohibition of torture was introduced, § 312 StGB torturing or neglecting a prisoner , as well as § 312a StGB torture .

Liechtenstein

The mistreatment of prisoners is prohibited, § 312 StGB torturing or neglecting a prisoner .

Switzerland

Switzerland has ratified the UN Convention against Torture, but not implemented it. Neither torture nor mistreatment of prisoners is an explicit criminal offense in Switzerland, but of course the provisions on bodily harm and the like apply. In the cantons of Zurich ( § 148 GoG , cf. BGE 137 IV 269), St. Gallen and Appenzell Innerrhoden, civil servants enjoy relative immunity, cf. Art. 7 cAbs. 2 lit b StPO . In the event of mistreatment in police custody, a non-judicial body checks whether the immunity of the guilty police officer should be lifted or not for reasons of opportunity.

History until 1989

Holy Roman Empire and Germany

Roots in Roman Law

The historical roots of the practice of torture in the German late Middle Ages lie in Roman law . This was originally only known to torture against slaves, but since the 1st century AD in the case of majesty crimes ( crimen laesae maiestatis , i.e. high treason ) also against citizens.

The German loan word “torture” is derived from the Latin word poledrus “foal”, the name for a horse-like torture device.

There were two ways in which Roman law was imported into German law of the Middle Ages. On the one hand, it was canon law , which - with the center of the papal church in Rome - had always been based on Roman law (motto: Ecclesia vivit lege Romana , 'the church lives according to Roman law').

The second way that led to the adoption of Roman law in German medieval law was the so-called reception . In Italy, from the beginning of the 12th century, especially at the University of Bologna , based on a manuscript of a large Roman legal collection from the 6th century ( Corpus iuris civilis 'Complete Works of Secular Law') rediscovered in the 11th century, the ancient Roman law, which at the end of antiquity could look back on a thousand years of development. In the Holy Roman Empire , where secular rulers repeatedly with religious institutions and their legally trained clerics had come to terms, we now sent students to study - not existing in the kingdom - Jurisprudence at Italian universities. After completing their studies, they entered German legal practice as carriers of ideas about Roman law.

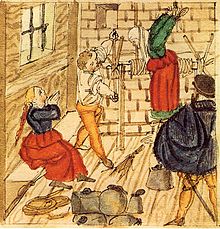

middle age

The law of the German Middle Ages was predominantly characterized by customary law - only partially recorded in writing - which developed differently in different places and times and was not scientifically and systematically justified and rationally permeated.

Before the turn of the millennium, church fathers and popes expressly rejected the use of torture, but that changed in the late medieval struggle of the church against the heretical movements of the Cathars (main group: Albigensians) and the Waldensians . In 1252 Pope Innocent IV issued his bull Ad Extirpanda . In it he called on the municipalities of northern Italy to use torture to force suspected heresy people to admit their errors "without breaking their limbs and without putting their lives in danger". This order, which was later extended to all of Italy and confirmed by later popes, was also used in the Holy Roman Empire in the ecclesiastical criminal procedure, the Inquisition , by the secular authorities obliged to do so.

According to the medieval view, a conviction could be based either on the testimony of two credible eyewitnesses or on the basis of a confession . On the other hand, mere circumstantial evidence , no matter how compellingly indicative of the guilt of the accused, or the testimony of a single witness, could not justify a conviction. This view was seen as supported by certain biblical passages such as Dtn 17.6 EU , Dtn 19.5 EU and Mt 18.16 EU .

Other names for torture were torture , torture , question in the severity or question in the sharpness or embarrassing questioning . The torture itself was not a punishment, but a measure of criminal procedural law and was intended to provide a basis for decision-making. In the Middle Ages, both physical torture and so-called white torture were practiced.

Late Middle Ages and early modern times

| Area / city | year |

|---|---|

| augsburg | 1321 |

| Strasbourg | 1322 |

| Speyer | 1322 |

| Cologne | 1322 |

| regensburg | 1338 |

| Nuremberg | 1350-1371 |

| Freiburg i. Br. | 1361 |

| Bamberg | 1381-1397 |

| Frankfurt a. M. | 2nd half of the 14th century |

| Brno (Moravia) | 1384-1390 |

| Büdingen (Wetterau) | 1391 |

| Friedberg (Wetterau) | 1395 |

| Memmingen | 1403 |

| Mergentheim | 1416 |

| Goerlitz | 1416 |

| Leipzig jury chair | 1350-1500 |

| Wroclaw | 1448-1509 |

| Oven (buda) | 1421 |

| Hamburg | 1427 |

| Munich | 1428 |

| Cham (Upper Palatinate) | 1438 |

| Vienna | 1441 |

| Constancy | 1450 |

| Osnabrück | 1459 |

| Hildesheim | 1463 |

| Schweidnitz | 1465 |

| Wurzburg | 1468 |

| Quedlinburg | 1477 |

| Basel | 1480 |

| Ellwangen | 1488 |

In secular jurisdiction , torture had been practiced in the Holy Roman Empire since the early 14th century. It developed towards the end of the Middle Ages as a means of criminal procedural law and was mostly defined as follows: An interrogation lawfully initiated by a judge using physical coercion for the purpose of researching the truth about a crime.

In addition to the theoretical foundations of the use of torture in the Holy Roman Empire in Roman law, practical needs in the fight against crime were added around the 14th century . The dissolution of old tribal and clan structures had led to social and local mobility, which was accompanied by an increased development of crime. Impoverished knights , wandering mercenaries , traveling scholars , wandering craftspeople, jugglers , beggars and other traveling people made the highways unsafe. Robberies and murders were the order of the day. The so-called "land-damaging people" formed a partially organized commercial and habitual criminality. It threatened trade and change and thus the foundations of prosperity, especially in the cities, for which the fight against crime became a vital necessity.

The traditional German criminal procedure law was largely unsuitable for an effective fight against crime. It was based on the idea that the reaction to an injustice committed was a matter for the person concerned and his / her family. Fighting crime was not a public task. The legal system had provided those involved with regulated forms for their dispute ( oath , judgment of God , duel ), but for a long time proceedings had only come about following a complaint by the person concerned or his clan. The principle was: "Where there is no plaintiff, there is no judge" . This principle, which still applies to German civil proceedings today, was also the basis of criminal procedure law for a long time. This type of procedure was largely unsuitable for the struggle of the state authorities against the "land-damaging people".

So they resorted to another type of procedure which had developed in the church, namely the so-called inquisition procedure (from Latin inquirere , to research). It was no longer a matter of formal evidence (by oath, judgment of God, duel - the church had forbidden the latter two pieces of evidence anyway in the fourth Lateran Council of 1215), but rather the material truth.

The evidence by two eyewitnesses did not play a significant role in practice. He could only come into play if the criminal had been observed by two witnesses and if he had been clumsy enough to let these witnesses survive. In the inquisition proceedings, for example, the accused's confession became the “queen of all evidence” and the confession was often obtained with the help of torture.

The overwhelming opinion was that torture was a necessary means of investigating the truth in criminal matters and that God would give the innocent the strength to survive the torture without a confession.

The use of torture spread throughout most of the Holy Roman Empire during the late Middle Ages and early modern times.

There were initially no legal regulations on the use of torture. This led to a largely arbitrary torture practice. In many cases it was lay judges who were not legally educated who had to decide on the torture.

Legal regulations in the 15th to 17th centuries

Arbitrary torture due to the lack of legal regulations led to lawsuits.

A program written in German law book , the order in 1436 in Schwäbisch Hall wrote Klagspiegel , castigated the abuses of the criminal justice system and tried to give the accused instructions as against incompetent and arbitrary judge, "foolish stern judge in the villages," by legal means to Could defend. Torture, the author demanded, should only be used “judiciously out of reason”.

The Reich Chamber of Commerce, established in 1495, reported to the Reichstag in Lindau in 1496/97 that it had received complaints according to which the authorities "should have condemned people to death through no fault of their own and without any right or honest cause and had them judged".

In 1498 the Reichstag of Freiburg decided to “introduce a common reformation and order in the empire, how one should proceed in Criminalibus”. Five Diets dealt with the required regulation of criminal proceedings. The Reichstag, held in Regensburg in 1532 , approved the “ Embarrassing Court Regulations of Emperor Charles V ”.

This new law regulated torture in particular. It was only allowed to be used if there were serious grounds for suspicion against the accused and if these grounds for suspicion were proven by two good witnesses or the act itself was proven by a good witness. Before deciding on the use of torture, the accused must be given an opportunity to exonerate. Even if there are established grounds for suspicion, torture may only be used if the reasons against the defendant are more serious than the reasons for his innocence. The degree of torture should depend on the severity of the suspicion. A confession made under torture may only be used if the accused confirms it at least one day later. Even then, the judge still has to check its credibility. The use of torture contrary to the provisions of the law must result in the judges being punished by their higher court.

The Embarrassing Court Order introduced a number of safeguard clauses in favor of the accused. By the standards of the time, it was progressive. But even by these standards it had gaps. Above all, it did not regulate the type and degree of torture and the conditions for its repeated use, but left all this to the "judgment of a good, reasonable judge". In this respect, it was sometimes only later territorial laws that introduced more detailed regulations, e.g. B. the Bavarian maleficent process code of 1608.

By and large, the embarrassing court order, which as imperial law only came to an end with the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 (as state law, it could also be applied later), has probably achieved its goal of more cautious use of torture. In some cities and territories it has been supplemented and partially modified in this direction by urban or territorial laws. In addition, there were differentiated teachings on torture developed by the Italian criminal law science, which had dominated the empire for a long time.

Witch trials

The embarrassing court order was almost ineffective in the mass persecution of witches in the second half of the 16th and 17th centuries. It was characteristic of these witch hunts - as well as of the mostly earlier ritual murder accusations against Jews - that one tortured so long, so violently and so often until the confessions desired by the tormentors were available. To make matters worse, those questioned in this way often adhered to the corresponding superstition themselves and were familiar with the delusions to be confessed.

The reason for disregarding the embarrassing court order in the great witch hunts was the same on the Catholic as on the Protestant side. Witchcraft is a crimen exceptum , an exceptional crime (according to the Catholic auxiliary bishop in Trier Peter Binsfeld in his infamous witchcraft tract of 1589), a crimen atrocissimum , a crime of the most terrible kind (according to the Lutheran and Saxon legal scholar Benedikt Carpzov in a crime textbook published in 1635 ) - with such crimes one does not need to observe the normal procedural rules.

In the 255 cases in which it had to conduct proceedings with reference to the witchcraft rule, the case law of the Reich Chamber of Commerce was strictly based on the Embarrassing Court Code. It rejected the exceptional crime theory and demanded that all evidence be examined for truth before torture could occur.

The Cautio Criminalis , a statement by the Jesuit Friedrich Spee against torture in witch trials (1631), paved the way for ending the practice of torture in witch trials .

Abolition of torture in the 18th century

Thought leader

There were isolated concerns about the sense and legality of torture as early as the Middle Ages. The fight against torture in intellectual history began before the Enlightenment and predominantly outside of Germany. The humanist, philosopher and theologian Juan Luis Vives , a Spanish convert to the Jews, rejected torture in a paper published in 1522 as unchristian and senseless. In the essays published shortly before 1580, the French philosopher Michel de Montaigne argues that torturing a person for a crime that is still uncertain can be found horrific and cruel and also doubts that the statements obtained under torture are reliable.

In 1602, the Reformed ( Calvinist ) pastor Anton Praetorius turned against torture in his “Thorough Report of Magic and Magicians”: “In God's word one finds nothing of torture, embarrassing interrogation and confession through violence and pain. (...) Embarrassing interrogation and torture are shameful because she is the mother of many and great lies, because they damage people's bodies so often and they perish: tortured today, dead tomorrow. "

In 1624, the Calvinist clergyman Johannes Grevius described torture as “barbaric, inhuman, unjust” . In terms of the matter - if not explicitly - the German Jesuit Friedrich Spee also pleaded against torture. Spee exercised radical criticism of the persecution of witches in his anonymously published work " Cautio Criminalis " as early as 1631 .

In 1633, the lawyer Justus Oldekop urged caution and prevention in criminal trials in the title of his Cautelarum criminalium Syllagoge practica ... (363 pages). In 1659, in his Observationes criminales practicae (478 p.), He specifically opposed the torture of "evidence" in the witch trial and in this respect speaks of "artificially invented crimes" (Quaestio Nona) as a result of the violent proceedings. In his armed pamphlets, he went far beyond the increasing criticism of the witch trial by reducing the existence of witches and consequently the legitimacy of witch trials to absurdity - as one of the earliest fighters against witch doctrine and madness.

In 1657 a dissertation was written at the University of Strasbourg under the theology professor Jakob Schaller with the title: "Paradox of torture, which may not be used in a Christian state". In 1681, the French Augustin Nicolas proposed in a letter to the French King Louis XIV to abolish torture as a model for all Christian princes, but in vain. The French philosopher and writer Pierre Bayle , a proponent of the idea of tolerance , fought against torture in a paper published in 1686. In 1705 the enlightening German lawyer and legal philosopher Christian Thomasius accepted a doctoral thesis entitled: "On the necessary banishment of torture from the courts of Christendom".

The French political scientist Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu in 1748, the French enlightenment philosopher Voltaire and in 1764 the Italian lawyer Cesare Beccaria continued to express themselves as opponents of torture .

Decrees to abolish it

|

Abolition of torture

|

|

| Area / city | year |

|---|---|

| Prussia | 1740 |

| Baden-Durlach | 1767 |

| Mecklenburg | 1769 |

| Braunschweig | 1770 |

| Saxony | 1770 |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 1770 |

| Oldenburg | 1771 |

| Austria | 1776 |

| Bayer. Palatinate | 1779 |

| Pomerania | 1785 |

| Saxony-Meiningen | 1786 |

| Osnabrück | 1787/88 |

| Bamberg | 1795 |

| Anhalt-Bernburg | 1801 |

| Bavaria | 1806 |

| Württemberg | 1809 |

| Saxe-Weimar | 1819 |

| Hanover | 1822 |

| Bremen | 1824 |

| Coburg-Gotha | 1828 |

Gradually in the 18th century the resistance of the authorities and their lawyers to the abolition of torture collapsed. Friedrich Wilhelm I . abolished the witch trials in Prussia de facto on December 13, 1714 by stipulating that every sentence for the execution of torture and every death sentence after a witch trial had to be confirmed personally by him. Since this confirmation never took place, there were no more witch trials in Prussia.

Just a few days after taking office, the Prussian King Frederick the Great had the “torture” expressly abolished in a cabinet order dated June 3, 1740, with three exceptions, however: high treason, treason and “major” murders with many perpetrators or victims. In 1754/1755 these restrictions were also removed without such an exceptional case having occurred. Friedrich's thinking was strongly influenced by Bayle's philosophy of tolerance. A few decades later, other territories followed in the empire, as the overview on the right shows.

In Austria, where the Constitutio Criminalis Theresiana was still in force in 1768 , in which the then usual torture methods were bindingly regulated, also in order to limit their use, torture was abolished on January 2, 1776 by a decree of Maria Theresa . Torture was no longer included in the Josephine Criminal Law , which came into force on January 1, 1787 .

The development in the rest of Europe was similar. In 1815 torture was abolished in the Papal States. It was last abolished in 1851 in the Swiss canton of Glarus , where one of the last executions for witchcraft in Europe was carried out on Anna Göldi in 1782 .

The real reason for the abolition of torture in the 18th century was, as Michel Foucault explains in " Surveillance and Punishment ", not primarily an enlightened humanism, but rather pragmatic considerations: torture brings quick confessions, but usually does not serve them Finding the truth, since the tortured person naturally has to say and say what the torturer wants to hear or expects. Torture was seen as a hindrance to fighting crime at the time.

The question of evidence

The abolition of torture did not solve the problem that was important for the general public and the judges: How was it to be achieved that the guilty would be punished while the innocent were acquitted? At first, instead of the abolition of torture, attempts were made to practice harassment in order to obtain confessions. The accused were beaten, which was not a traditional means of torture. One tried endless interrogations, persuasions or threats, the imposition of disobedience or lies, and the deprivation of food in prison. These solutions were not legally convincing or humane.

Now that the confession had played out its role as queen of all evidence, the question of the value of circumstantial evidence arose . For example, people were reluctant to impose the death penalty on circumstantial evidence. Textbooks emerged with theories about the circumstantial evidence; one subdivided into preceding, simultaneous and subsequent indications, into necessary and accidental, immediate and indirect, simple and compound, near and distant. The uncertainty of the legal scholars was still reflected in the legislation of the 19th century. Only gradually did it become apparent that it was pointless to force the formation of judicial convictions into a corset of legal regulations, but that the solution was to recognize the principle of free judicial assessment of evidence . This principle was then adopted in the Reich Penal Procedure Code in 1877. Even today it is still valid in the unchanged wording as Section 261 of the German Code of Criminal Procedure: "The court decides on the result of the taking of evidence according to its free conviction, drawn from the epitome of the hearing."

In his basic book on criminal law in the sense of the Enlightenment of 1764 Dei delitti e delle pene (on crimes and punishments) Cesare Beccaria rejects torture. Either the accused is guilty or he is not guilty, Beccaria argues: If he is guilty, that will show evidence and the perpetrator will be brought to his due sentence; if he is innocent, an innocent person would have been tortured. The legal philosopher counters the argument that torture serves to establish the truth with the words:

- “As if you could test the truth with pain, as if the truth were sitting in the muscles and tendons of the poor, tortured guy. With this method, the robust will be set free and the weak will be judged. These are the inconveniences of this supposed truth test, worthy of only a cannibal. "

Historization of torture from the 20th century

After torture was legally abolished almost everywhere in German areas in the 18th and 19th centuries, a process of historicization began - especially since the beginning of the 20th century - i.e. a changed perception of torture from a more clarified distance. Torture was increasingly viewed as a now outdated element of the past. It was also seen as a measure that had since been overcome and that was now gradually losing its threat potential.

At the same time, the subject of torture penetrated the fields of science, literature and entertainment. Scientific work began to deal with the topic. Richard Wrede wrote in 1898: "There were terrible aberrations in the human spirit." Franz Helbing also declared torture as "a word that we utter today with horror and that we regard as the barbarism of the past."

The first museums and exhibitions on torture were established and became a popular attraction. An example of this is "the historical and world-famous collection of torture devices from the Imperial Castle of Nuremberg, including the famous Iron Maiden, from the holdings of the honorable Earl of Shrewsbury and Talbot", which was shown in New York in 1893. The museum of local history opened in 1926 in the witch mayor's house in Lemgo is also part of this development.

Torture also finds its way into literature. In addition to different considerations on the subject, the assessment of torture as an element of the past also stands here. In the novel Der Zauberberg , published in 1924 , Thomas Mann puts the words in his protagonist Hans Castorp's mouth: "Torture was abolished, although the examining magistrates still had their practice of making the accused tired."

This statement - made here only by a character from a novel - refers to a different aspect in the context of the historicization process: although classic torture was now forbidden by law and was considered obsolete, updated forms of torture continued to exist in the 20th century. With terms such as soul torture, psychological effects were now brought into focus. The practice of the police at this time was also in the context of modern torture: "On the guard, the policemen in many cases also beat innocent citizens with fists, sometimes even with sabers, and tied and gagged them like felons." Against this background, in At that time also the "protection from the policeman" became a popular phrase.

Ultimately, in addition to the historicization process, through which classical torture was increasingly viewed as a traditional element of bygone times, there are updated forms of torture that already point to the persistence of torture in the 20th century and beyond.

Legal history of torture

Torture in the Holy Roman Empire was believed by the vast majority of contemporaries to be lawful. It was based on publicly proclaimed papal bulls , imperial privileges and solemn Reichstag resolutions; therefore one can speak of a legal history of torture . The torture still practiced by many dictatorial and authoritarian regimes in our era is unlawful, which is why these regimes regularly deny the use of torture methods. There is only one injustice story of torture left today .

National Socialism

In the 20th century, cruel interrogation methods were again permitted and used during the Nazi era . In official German , torture was referred to as a " tightened interrogation method ". On May 28, 1936, Reinhard Heydrich issued a secret order to the state police stations , according to which "the use of more stringent interrogation methods must under no circumstances be put on record". The interrogation files of tortured accused are to be kept under lock and key by the head of the respective state police station.

GDR

In the Soviet-occupied zone , various types of torture were practiced by Soviet occupation forces, in particular water torture . There was torture of various degrees of severity in the GDR . Until 1953 - the death of Stalin and the official abolition of torture in the Soviet Union - "the rule, not the exception". Torture through beatings, permanent isolation and systematic sleep deprivation was used until 1989.

Federal Republic

When practiced on some convicted terrorists left incommunicado accusations of torture was raised, the contact ban law , however, was in 1978 by the Federal Constitutional Court found unconstitutional.

Chile during the military dictatorship 1973–1988

After the military couped against the socialist president of Chile, Salvador Allende on September 11, 1973 , it installed a brutal dictatorship. Soon the commander-in-chief of the army, Augusto Pinochet , was the undisputed leader. On the day of the coup, the military dissolved almost all democratic institutions and began to systematically wipe out their political opponents. Before the murder of the mostly secretly arrested ( Desaparecidos ) people, it was customary to torture them in order to extract information from them. At least 27,000 people were tortured over almost 17 years.

Testimony of a woman captured in October 1975 in the Arica Regiment in La Serena :

“I was five months pregnant when I was captured. [...] Electric torture on the back, vagina and anus; the nails of fingers and toes were pulled; blows many times to the neck with batons and rifle butts; fake executions, they didn't kill me but I had to listen to the bullets go in right next to me; I was forced to take medication; they injected me with Pentothal with the warning that under hypnosis I would be telling the truth; Trapped on the floor with legs apart, rats and spiders were inserted into my vagina and anus, I felt them bite me, I woke up in my own blood; they forced two prison doctors to have sex with me, both of whom refused, and the three of us were beaten up; I've been taken to places where I've been raped countless times over and over, sometimes having to swallow the rapists' semen, or getting their ejaculate smeared on my face and all over; they made me eat excrement while punching and kicking me on my back, head, and hip; I received electric shocks countless times ... "

History since 1990

While torture continues to be widespread in many non-democratic countries despite international ostracism, the rule of law pretends to not allow torture under any circumstances.

Current discussions deal again with the question of the use of torture and / or "tough interrogation methods", including in connection with the fight against terrorism .

Germany

In the Federal Republic of Germany , any impairment of the free decision-making and the exercise of will of an accused by abuse is prohibited by law (see above).

Individual occurrences

The Federal Republic of Germany has been convicted in the past by the European Court of Human Rights for violations of the UN Convention against Torture .

In the Vera Stein case , the plaintiff was awarded € 75,000 in damages because the Federal Republic of Germany had not adequately prosecuted a torture case. In another case, the Federal Republic of Germany was convicted of forcibly administering an emetic .

In 2004 it became public that during basic training in the Bundeswehr repair battalion 7 in Coesfeld, recruits were tortured in simulated hostage-taking by being tied up and hosed down with water. The soldiers were also mistreated with electric batons and blows in the neck. A total of 12 cases became known. Disciplinary investigations were carried out against 30 to 40 trainers. The then Defense Minister Peter Struck announced that the entire Bundeswehr would be checked for further incidents.

Jan Philipp Reemtsma is one of the most prominent critics of torture , who describes it as a breach of civilization.

The Daschner trial, discussion about the "rescue torture"

In Germany, triggered by the kidnapping of the Frankfurt banker's son Jakob von Metzler , a discussion took place about the term “ rescue torture” in connection with the absolute prohibition of torture.

Initial situation, question

In autumn 2002, the then Frankfurt Police Deputy President Wolfgang Daschner ordered that the suspect in the Metzler, Magnus Gäfgen kidnapping case, be threatened with "massive infliction of pain" and, if necessary, carried out. Even after this threat of torture, Magnus Gäfgen revealed the whereabouts of the victim, who had already been killed.

As early as 1996, important theses, which the proponents of the use of torture to “ avert danger ” asserted in favor of Deputy Police President Daschner, were developed by constitutional lawyer and legal philosopher Winfried Brugger . He tried to justify the obligation to use torture for the purpose of averting danger on the basis of a fictional terrorist case inspired by the sociologist Niklas Luhmann in terms of legal philosophy, fundamental rights dogmatics and police law. Brugger himself later consistently spoke out against the "rescue torture".

Legal evaluation

The use of torture is not permitted in Germany because the European Convention on Human Rights ratified by Germany , the Basic Law and the Code of Criminal Procedure contain a clear prohibition of torture (see above).

It is also argued that the Frankfurt police's threat of pain violated human dignity , which also exists for suspects. It is therefore unconstitutional . The protection of human dignity is absolute in the Basic Law, i. That is, it should not be weighed against other rights, not even against the right to life or the human dignity of third parties, as otherwise the object formula would be violated. It prohibits the state from making a person an object of state action.

In recent years, however, in the legal debate (especially on bioethics ) there have been an increasing number of voices that advocate the consideration or gradation of the principle of human dignity and thus no longer categorically reject torture. However, according to consequentialist considerations, there are arguments against weighing human lives.

According to the regulations of police and regulatory law, statements may not be blackmailed even for the purpose of hazard prevention (example Hesse, Section 52 (2) HSOG). There are comparable regulations in other federal states. Occasionally, to justify “special interrogation methods”, reference is made to the legal regulations on self-defense and state of emergency ( §§ 32 ff. StGB, § 228 , § 904 BGB ) or the legality based on a “supra- legal state of emergency” is asserted. The prohibition of torture in the European Convention on Human Rights according to Art. 15, Paragraph 2 also provides for a ban on torture in emergencies, from which "under no circumstances may"

The further happening

In the criminal trial against Magnus Gäfgen, the statements made under threat of torture could not be used (§ 136a StPO). Police Vice-President Wolfgang Daschner, who ordered the threat of torture, and the police officer Ortwin Ennigkeit, who issued the threat, were tried before the Frankfurt Regional Court for coercion in a particularly serious case. On December 20, 2004, both of them were given a final suspended sentence.

It is thus judicially established that the threat of violence was also illegal and punishable in this case. The reason for the conviction was, however, despite partly different media reports, only a lack of necessity of the possible self-defense. The court left open the question of whether such acts of torture can be justified abstractly as self-defense.

On the other hand, the large chamber of the European Court of Human Rights ruled on June 1, 2010 that the threat of torture was inhumane treatment within the meaning of the European Convention on Human Rights and is prohibited without exception. The penalties against Daschner and Ennigkeit could not be regarded as an appropriate reaction to a violation of Art. 3 ECHR despite attenuating circumstances and would be disproportionate in view of the violation of one of the core rights of the Convention. Based on this, the Regional Court of Frankfurt Gäfgen awarded a compensation of 3,000 euros from the State of Hesse in August 2011. The Frankfurt Higher Regional Court confirmed this decision in 2012.

Austria

In Austria too, individual cases of abuse by the police are repeatedly uncovered.

The Bakary J.

In April 2006, after a failed deportation, the Gambier Bakary J. was brought to an empty warehouse in Vienna by four WEGA officers and was badly mistreated. It took 6 years for the officers to be dismissed, after having only been transferred to the office after being sentenced to a conditional sentence.

The 35-minute film Void was released in 2012 about the incident - with the names of both the victim and the tormentor changed. On 11/12 February 2017, Die Presse and ORF reported on the appearance of the free online book How it happened - An experience report from my point of view by Bakary Jassey , with an introduction by Reinhard Kreissl (legal sociologist) and forewords by Heinz Patzelt (lawyer, Amnesty International), who had researched this case early and Alfred J. Noll (lawyer, editor). Bakary (* 1973, left his home country Gambia in 1996) originally described his experience from April 2006 until his release in August 2006 in English; the book contains an edited translation by friends into German.

France

Police violence and assaults have been an issue in France for decades. Amnesty International has followed around 30 cases of violent abuse by the French police over a period of 14 years. The new report from 2012 documented 18 cases, including five cases of fatal use of firearms and another five cases of death in police custody. The police are extremely brutal when it comes to establishing personal details. Typical are blows with fists or clubs that lead to broken noses, eye injuries, bruises and other injuries. In many cases the abused report having been insulted in a racist way.

The Selmouni / France case

At the end of November 1991, Ahmed Selmouni, a Moroccan-Dutch national, was arrested in Paris on suspicion of drug smuggling and taken to the Bobigny police station . From the first interrogation, he was subjected to physical abuse, which subsequently increased in severity. His physical condition was repeatedly examined and recorded by doctors. After a few days in the Fleury-Mérogis remand prison , the examining doctor found that the time when the approximately two dozen bruises, swellings and abrasions he recorded at Selmouni correlated with the police station, but that the injuries would all "heal well" . Selmouni also confirmed that he was receiving pain medication.

In early December 1992, Selmouni was sentenced to 15 years imprisonment and lifelong banishment from French territory for drug offenses. In addition, a joint fine of 20 million francs (≈ 3.05 million €) was imposed on him and his co-defendants. The length of imprisonment was later reduced to 13 years, an appeal was dismissed.

At the end of December 1992, Selmouni submitted a complaint to the European Commission on Human Rights , according to which the French state had massively violated his rights under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) . France was facing him

- the prohibition of torture ( Art. 3 ECHR), and

- the right to a fair trial before an impartial court ( Art. 6 Para. 1 ECHR)

violated. In November 1996 the commission found the complaint admissible and unanimously supported Selmouni's allegations in its investigation report. In the subsequent hearing, the European Court of Human Rights came to largely the same view. Together, Selmouni were awarded a little over 600,000 francs (≈ 93,500 €) in compensation for pain and suffering plus reimbursement of costs.

The court found that the police officers involved were exceptionally guilty and demanded severe punishment regardless of "the extent to which they were dangerous". But as serious as the allegations are, the judgment continues, given the fact that the alleged sexual abuse could not be proven and given the previous impunity of the officials and their conduct files, the Court considers a reduction in the imprisonment imposed to be appropriate. who are also to be suspended on probation. Which disciplinary measures should be taken is at the discretion of the respective superiors.

Israel

In 1999, Amnesty International reported that handcuffing in painful positions, sleep deprivation and violent shaking were still allowed. A 2009 report by the UN Committee against Torture reported allegations of torture in facility 1391 , a secret prison that was closed in 2006 . In total, the committee reported around 600 complaints about torture methods in Israel between 2001 and 2006 (i.e. during and shortly after the Second Intifada ) and called on Israel to investigate the allegations. This stated that the allegations had already been examined and refuted. An October 2011 report by the Israel Public Committee against Torture and the Physicians for Human Rights medical organization speaks of ill-treatment and torture of detainees by security personnel. He also accused Israeli doctors of covering up real medical reports of injuries caused during interrogation. It cites “countless cases where individuals testify to injuries inflicted on them during detention or interrogation; which the medical report from the hospital or prison staff did not mention ”. The report is based on 100 cases of Palestinian prisoners brought before the committee since 2007.

Italy

The Italian authorities deported at least 45 people to Libya on June 22, 2005 , where they could face serious human rights violations such as torture.

With regard to the situation in Italy, Amnesty International reported on excessive use of force and mistreatment, including torture, by officers with police powers and prison staff. Several people died in custody under controversial circumstances. Hundreds of people were victims of human rights violations during large-scale police operations .

As part of the G8 summit in Genoa in 2001 and the associated demonstrations by globalization critics, many demonstrators were brought to the notorious Bolzaneto prison to be interrogated there. Numerous arrested persons subsequently reported severe abuse and torture , including during the Bolzaneto trial .

The Italian public debated whether torture could be legitimate under certain circumstances. A few days before an amendment to the penal code was passed, the Lega Nord tabled an amendment stating that torture or the threat of torture would only be punishable if it was repeated. It has been argued that torture, or the threat of it, may be a legitimate means of terrorism.

Palestinian Territories

Nasser Suleiman, director of the maximum security prison in Gaza City, told Spiegel that detainees on remand were being tortured. This is done, for example, by tearing out toenails or hanging on the arms for hours . The results of the investigation often lead to the death penalty.

Spain

Franco dictatorship and transition to democracy

The background to today's, sometimes problematic, human rights situation in Spain is the time of the Franco dictatorship (until 1975). The transition from Franquism to democracy did not break with the dictatorial system, which also meant that torturers were not released from the police force and that there was no prosecution for the serious human rights violations during the dictatorship.

During the transition to democracy (span. Transición ) there was strong activity by the Basque terrorist organization ETA against the institutions of the Spanish state. The state's reaction to this was extraordinarily harsh for a democracy. In many cases, statements continued to be blackmailed through torture, and terror suspects were often severely mistreated out of revenge. There were repeated deaths in the police barracks and prisons. In the 1980s, a state terrorist group ( GAL ) was set up, which for many years fought the ETA with torture and murder. This era is known in Spain as the Dirty War (span. Guerra sucia ).

For torture, political murder and severe mistreatment by police and military personnel up to the 1980s, there is ample evidence and also final convictions up to the highest levels of government (generals, ministers, etc.). At that time Spain was already a democratic country and a member of the EU and NATO .

Todays situation

In Spain there is repeated abuse and torture (span. Tortura ) by officers with police powers (National Police, Guardia Civil, etc.). The victims are often women, refugees and members of minorities, so that Amnesty International assumes in many cases sexist, xenophobic or political motives. The existence or the extent of torture is politically highly controversial and is discussed controversially again and again.

The inconsistent prosecution of assaults and the very mild punishments in relation to the offenses are repeatedly criticized. The UN Human Rights Committee criticizes the fact that convicted torturers from the ranks of the security forces are "often pardoned, released early or simply not served their sentence." In 2012, the European Court of Human Rights sentenced Spain to pay compensation to the former editor-in-chief of a Basque daily newspaper, as allegations of torture had not been investigated.

The possibility of non-contact detention in Spain is widely criticized: the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture , the UN Human Rights Committee , the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT) as well as Amnesty International and other human rights organizations regularly criticize special legal provisions that allow detention under a contact ban (span. prisión incomunicada ). These conditions of detention are referred to as a "torture-promoting practice" because of the complete defenselessness of the accused. Intensive interrogation by the Civil Guard or the National Police takes place, but the accused does not have the right to a lawyer or an examination by an independent doctor. These conditions of detention apply for up to five days and the appearance at the judge usually only takes place after this time. Since 2003, it has been possible to extend the contact ban for another eight days. Detainees regularly raise allegations of torture, ill-treatment and extorted testimony during this period. In numerous cases, doctors were able to detect clear traces of physical violence after the contact was blocked. In 2006, the Basque Parliament passed a resolution with an absolute majority calling on the Spanish government to “recognize the existence of torture and its use in some cases in a systematic way.” The Spanish judiciary repeatedly has members of the police and the military for torture convicted of prisoners.

According to Amnesty International, between 1995 and 2002 there were at least 320 cases of racially motivated attacks on people from 17 countries, including Morocco , Colombia and Nigeria . Victims who report ill-treatment are often faced with counterclaims from police officers. Fear, lack of legal support, inaction and bias on the part of the authorities mean that many victims fail to report assaults. Police officers with a criminal record or those who are under investigation are not suspended from duty, but are even supported by political authorities. On the other hand, police officers who campaigned for the protection of human rights have been punished. For example , disciplinary action was taken against three officials who had drawn attention to irregularities in the arrest and deportation of Moroccan children in Ceuta in 1998 .

United States

Postwar CIA Activities

The American historian Alfred McCoy documents in his book Torture and Let Torture. 50 years of torture research and practice by the CIA and the US military, the research and application of torture methods by the CIA . These were also carried out in the Federal Republic of Germany after the Second World War. The result of these activities was, among other things, the so-called Kubark manual .

"War on Terror" from 2001

According to the American historian Alfred W. McCoy , the following human rights violations by US authorities and the military took place in the course of the " War on Terror " from 2001 to 2004:

- Iraqi "security detainees" have been subjected to harsh interrogation and, often, torture.

- 1,100 "high profile" prisoners were interrogated under systematic torture in Guantánamo and Bagram .

- 150 terror suspects were illegally transferred through extraordinary rendition to countries notorious for the brutality of their security apparatus.

- 68 prisoners died under questionable circumstances.

- About 36 senior al-Qaeda detainees remained in CIA custody for years and were systematically and persistently tortured.

- Twenty-six prisoners were murdered during interrogation, at least four of them by the CIA.

It was not until 2014 that a report by the United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence became known, according to which the CIA used considerably more and considerably more brutal torture methods in interviews and in no case any information was obtained through torture that was not already known through other methods. The CIA had lied systematically and repeatedly about both of these aspects since the first debates.

The report of the Senate Committee was published on December 9, 2014.

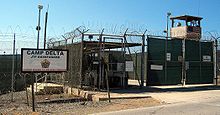

Guantanamo prison camp

President George W. Bush stressed that he had never ordered torture and never would because it was against the values of the United States. Bush's remarks are confirmed by a published note dated February 7, 2002, in which the President expressly ordered that prisoners be treated humanely and in accordance with the Geneva Convention. In his book Decision Points , however, he wrote personally the waterboarding of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed to have arranged.

On December 2, 2002, US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld , who was no longer in office , approved certain controversial methods of interrogation of suspected members of al-Qaeda and Afghan Taliban militants held in the Guantanamo detention center in Cuba. He followed a memorandum from his chief lawyer William J. Haynes , who had approved 14 interrogation methods for Guantánamo. These included light physical abuse “that did not lead to injury”, remaining in painful positions, interrogations lasting up to 20 hours, isolation of prisoners for up to 30 days, confinement in the dark and standing for hours.

Much of these methods, which contradict international law, were banned again seven weeks later by Rumsfeld himself. In an order dated April 16, 2003, compliance with the requirements of the Geneva Conventions is expressly required. However, certain "tough" interrogation methods such as solitary confinement or aggressive questioning could be used with the approval of the United States Department of Defense .

The United States has repeatedly been accused of violating the Geneva Conventions in Guantánamo, which the Pentagon confirmed in 2004 in the following cases:

- Interrogators threatened an inmate with persecuting his family

- Tape up the mouth of a prisoner for quoting verses from the Koran

- Smearing the face of an inmate stating that the liquid was menstrual blood

- Chaining prisoners in a fetal position

- Misrepresentation of interrogators as Foreign Ministry employees

- Koran abuse

On October 4, 2007, secret memoranda of the US Department of Justice, which were written in May 2005, were published in the New York Times . In them, the following interrogation methods of the CIA are considered to be lawful:

- Blows to the head

- Naked in cold prison cells for several hours

- Sleep deprivation for several days and nights due to the exposure to loud rock music

- Shackles the prisoner in uncomfortable positions for several hours

- Waterboarding : The inmate is tied to a board, a damp cloth is placed on his head and water is poured over him. The emerging gag reflex gives him the impression that he is drowning.

The methods may also be used in combination. President Bush defended the methods mentioned in a speech.

Abu Ghraib and Bagram

After the end of official hostilities of the third Gulf War that came Abu Ghraib prison in April 2004 in the headlines. The CBS television station reported on torture, abuse and humiliation of prisoners by US soldiers. The case has preoccupied the US judiciary since then.

Among other things, the main culprit Charles Graner was sentenced to 10 years in prison. Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice officially apologized to the Iraqis: "We are very sorry for what happened to these people." The spokesman for the US Forces in Iraq, General Mark Kimmitt , officially apologized for the "shameful incidents". See also Abu Ghraib torture scandal .

Amnesty International reports of deaths at the US air force base in Bagram , Afghanistan , which indicate torture.

Military Commissions Act

The Military Commissions Act , which was adopted on 28 September 2006 by the Senate, it expressly allows so-called unlawful combatants (unlawful enemy combatants) certain "sharp interrogation practices" suspend. In the opinion of human rights organizations and the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture Manfred Nowak , this is to be seen as torture. Information extorted under torture may also be used in military courts. In the opinion of commentators, the United States is thus easing the ban on torture in the Geneva Conventions . Above all, according to the law, foreigners who are declared by the authorities as "unlawful enemy combatants" can be convicted by military tribunals without a legal hearing - without disclosure of evidence.

The passing of the law was received with indignation by large parts of the American public and was widely viewed as a breach of the constitution. In a comment on TV station MSNBC , the law was described as the " Beginning of the end of America ." The New York Times wrote, "And it [the law] is eroding the foundations of the judicial system in ways that all Americans should find threatening " (And it chips away at the foundations of the judicial system in ways that all Americans should find threatening .)

Obama administration

According to the secret documents published by the Obama administration, torture was precisely regulated in CIA manuals and legally legitimized by legal advisers to the government.

General David Petraeus has spoken out against the torture of captured terrorists. Violations of the Geneva Convention would never pay off militarily or politically. In order to rule out that a state torture practice with legal legitimation can be repeated, the formation of a torture commission is required. The Guardian has linked him to the torture centers in Iraq .

Current allegations are directed at the conditions of detention of Chelsea Manning , who is charged with the possible disclosure of videos and documents to WikiLeaks . Manning's supporters made a complaint to Manfred Nowak , the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture , in December 2010 . Its office said it was investigating the complaint, while the US Department of Defense denied the allegations. Nowak's successor, Juan E. Méndez , was denied a confidential meeting with Manning on several occasions, which she publicly complained about in July 2011.

Iraq

Saddam Hussein's regime

Torture was a common practice of the regime in Saddam Hussein- era Iraq .

Most of the victims of torture were people who were in political opposition to the government in Baghdad. Members of the security forces who were suspected of belonging to the opposition and Shiites were also tortured. As Latif Yahya reported in his biography I Was Saddam's Son , torture was also practiced simply for fun or to get a woman.

Methods of torture included punching and electric shocks, eyes gouging. In many cases, the victims were also inflicted with burns from burning cigarettes that were put out on the body. Victims reported having their fingernails pulled or their hands pierced by electric drills. Sexual violence was also part of the repertoire of torturers in Iraq. This ranged from threats of rape to anal rape with objects.

Amnesty International reported at the time:

“The Iraqi people have suffered for years from the human rights abuses inflicted by their government: systematic torture, extrajudicial executions, ' disappearances ', arbitrary arrests, evictions and unfair trials. [...] Both the most brutal physical and psychological torture is widespread in Iraq and is systematically used on political prisoners. "

Torture under the current Iraqi government

The current Iraqi government is also accused of using torture methods against its opponents. On July 3, 2005, the British Observer reported that Iraqi secret forces had been tortured against terror suspects. According to the Observer, the research also revealed that there is a secret network of torture centers in Iraq to which human rights organizations have no access. Interrogations in the prison camps used beatings, burns, hanging on arms, sexual abuse and electric shock. Such human rights violations had even been committed in the Iraqi Interior Ministry. There is cooperation between “official” and “unofficial” prison camps, and there is evidence of illegal shooting of prisoners by the police. The UK Foreign Office said the allegations were being taken "very seriously". The abuse of prisoners was "unacceptable" and was raised at the highest level with the Iraqi authorities.

Egypt

Egypt is repeatedly accused of systematic torture by government agencies on a large scale, so that even the extradition of people to Egypt is considered problematic. Amnesty International reports of torture and killings which are the order of the day and which are not punished. Responsible for these human rights violations is the then head of the secret service and later Vice-President of Egypt, Omar Suleiman, who is said to have personally tortured and issued orders to murder prisoners.

The NADIM center in Cairo is trying to document torture in Egypt. There were 40 deaths as a result of torture between June 2004 and June 2005. In the summer of 2004, alleged employees of the Egyptian health authority confiscated patient files during a surprise "inspection visit" and threatened to close it because the center was supposedly not only pursuing "medical" goals.

The blogger Noha Atef has been able to uncover concrete cases of torture and name the perpetrators through publications on the Internet since 2006.

Physical and psychological consequential damage

Torture can cause emotional and physical complaints in those affected. One of the greatest complications of torture is physical pain caused by injuries. However, there is also pain with a psychosomatic background, which is a physical expression of the trauma . The torture survivors suffer from headaches , insomnia , back pain, and shoulder and neck tension. The stressful state can aggravate physical illnesses such as high blood pressure or diabetes mellitus . Traumatized people often suffer from stomach complaints and eating disorders , women after gender-specific violence from abdominal complaints and menstrual disorders. The physical and psychological complaints can be alleviated with medication. In the case of chronic or complex trauma, psychotherapeutic treatment should be used.

Individual questions

Torture research

When modern scientists study torture, it is usually to find medical evidence of specific types of torture. In 1982, Danish doctors investigated the question of whether burns caused by heat differ from burns caused by electric current dermatologically . They demonstrated in anesthetized pigs that the difference is significant and provided a simple diagnostic method to detect electro-torture.

Historians dealt with the course of torture scenarios in the Middle Ages, but also with questions of the interpretation of ancient scriptures. A “critical study” published in 1877 on the question of whether Galileo confessed to Galilei after torture caused a sensation. The Hamburg chemist Emil Wohlwill came to the conclusion that Galileo had actually been subjected to the "rigorous examination" (esame rigoroso), contrary to popular belief.

Torture and racism

The documentary "Lynching America", written by the Equal Justice Initiative, shows that despite the 13th amendment to the Constitution passed in December 1865, there was a "second slavery" in the USA. The documentary shows lynching of blacks as "public torture": "Lynching was cruel and a form of public torture that traumatized black people across the country while state and federal authorities largely tolerated it. " The lynchings are also characterized as terrorist: "Terror lynching reached its peak between 1880 and 1940 and resulted in the deaths of African American men, women and children who were forced to helplessly endure the fear, humiliation and barbarism of this widespread phenomenon."

Psychology of the perpetrator

In some experiments, psychology tested the willingness to do cruelty to other people by submitting one's own conscience to obedience, etc. a. with the Milgram experiment .

In the Stanford Prison Experiment , healthy, normal students were placed in the position of prison guards and prisoners, which resulted in abuse within a few days.

In a recent article, the psychologist Philip Zimbardo of the University of California, Berkeley , examines perpetrator psychology: Under what conditions do ordinary people become torturous sadists? Among other things, he gives the following ten-point "recipe":

- Give the person a justification for what they did. For example an ideology, "national security", the life of a child.

- Arrange for a contractual agreement, in writing or orally, in which the person undertakes to conduct the desired behavior.

- Give everyone involved meaningful roles that are filled with positive values (e.g. teacher, student, police officer).

- Give out rules that make sense in and of themselves, but which should also be followed in situations where they are pointless and cruel.

- Change the interpretation of the crime: Don't talk about victims being tortured, talk about helping them do the right thing.

- Create opportunities to diffuse responsibility : In the event of a bad outcome, the perpetrator should not be punished (but the superior, the person carrying out the work, etc.).

- Start small: With slight, negligible pain. ("A small electric shock of 15 volts.")

- Gradually and imperceptibly increase the torture. ("It's only 30 volts more.")

- Slowly and gradually change the influence you exert on the perpetrator from “reasonable and just” to “unreasonable and brutal”.

- Increase the cost of denial, for example by not accepting common ways of objection.

Zimbardo's thesis and an interpretation of the Milgram experiment is that under such framework conditions most people are ready to torture and harm other people.

Political-Sociological Aspects

A political sociological and historical study by Marnia Lazreg Torture and the Twilight of the Empire. From Algiers to Baghdad advocates the thesis that imperial powers, contrary to their own perception, (again) take up torture in the face of defeat.

Torture methods

According to the UN Convention against Torture, torture methods can be :

- Electric shock

- anal or vaginal rape (with various objects, blindfolded, immobilized by shackles, by several people)

- Constrained postures ( penalization , goal standing , kneeling, sitting, hanging, shackling, especially over long periods of time, e.g. by means of " hogties ", disciplinary stools )

- Beatings (including bastinades , whipping , beatings on the whipping box , "Telefono", beatings by several people)

- Hanging ( strappado , " parrot swing ", pole hanging )

- Starting from burns , mutilation by the hair, nails, skin, tongue, ears, genitalia, and limbs, belt cutting

- Tooth torture (e.g. knocking out teeth, drilling into the tooth root )

- Forced examinations (gynecological, gastroenterological, routine control of the body orifices)

- Bamboo torture

Furthermore:

- pharmacological torture ( drug abuse , forced medication)

- massive humiliation (eating excrement, drinking urine, masturbating in public)

- Interrogation torture

- Forced labor exhaustion

- Food deprivation

In white torture , the torture methods leave no obvious traces on the victims. White torture includes:

- Sensory deprivation (withdrawal of stimuli), e.g. B. In the dark in a camera silens

- sleep deprivation

- Mock executions

- tickle

- Waterboarding

- Noise torture

- Toilet ban

- Oxygen deficiency ("submarino", masks)

- Solitary confinement

- Causing nausea (through artificially produced kinetosis )

Organizations Against Torture

International government organizations (selection):

- UN Special Rapporteur on Torture

- UN Committee against Torture

- UN Subcommittee on the Prevention of Torture

- European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

International non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (selection):

National non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (selection):

- Committee for the Prevention of Torture (Russia)

- Public Committee Against Torture in Israel

- Treatment center for torture victims , Berlin

- REFUGIO Munich

literature

story

- Franz Helbing: The ordeal. History of criminal torture of all times and peoples. Completely reworked and supplemented by Max Bauer, Berlin 1926 (reprint Scientia-Verlag, Aalen 1973, ISBN 3-511-00937-5 )

- Edward Peters: Torture. History of the awkward questioning . European Publishing House, Hamburg 1991, ISBN 3-434-50004-9 .

- Mathias Schmoeckel: Humanity and State Reason. The abolition of torture in Europe and the development of common criminal procedure and evidence law since the high Middle Ages . Böhlau, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-412-09799-3 . Comprehensive presentation of the abandonment of torture as a logical consequence of an evolving modern understanding of the state and the judiciary.

- Lars Richter: The history of torture and execution from antiquity to the present , Tosa, Vienna 2001, ISBN 3-85492-365-1 .

- Torture tools and their application 1769. Constitutio Criminalis Theresiana, Reprint-Verlag-Leipzig, 2003, ISBN 3-8262-2002-1 .

- Dieter Baldauf: The torture. A German legal history . Böhlau, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-412-14604-8 . A well-understandable, nonetheless scientifically sound presentation of the legal history of torture, including numerous other references, which is also easy to understand for laypeople in legal history.

- Robert Zagolla: In the Name of Truth - Torture in Germany from the Middle Ages to today . be.bra, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-89809-067-1 . Serious presentation of developments in Germany from the origins to the current discussion; debunks numerous myths.

- Daniel Burger: Thrown into the tower. - Prisons and torture chambers on castles in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. In: Burgenbau im late Mittelalter II, ed. from the Wartburg Society for Research into Castles and Palaces in conjunction with the Germanic National Museum (= Research on Castles and Palaces, Vol. 12), Berlin and Munich (Deutscher Kunstverlag) 2009, pp. 221–236. ISBN 978-3-422-06895-7 .

- Wolfgang Rother : Crime, Torture and the Death Penalty. Philosophical arguments of the Enlightenment . With a preface by Carla Del Ponte . Schwabe, Basel 2010, ISBN 978-3-7965-2661-9

- Torture in witch research , Historicum.net

- Torture - Made in USA , ARTE documentary 2010/2011.

- Friedrich Merzbacher : The witch trials in Franconia. 1957 (= series of publications on Bavarian national history. Volume 56); 2nd, extended edition: CH Beck, Munich 1970, ISBN 3-406-01982-X , pp. 138–155.

Current situation

- Peter Koch / Reimar Oltmanns: Human dignity - torture in our time. Goldmann, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-442-11231-1 .

-

Horst Herrmann : The torture. An encyclopedia of horror . Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-8218-3951-1 .

The most comprehensive documentation of torture methods and devices from past and present to date. - Alfred W. McCoy : Torture and Let Torture. 50 years of torture research and practice by the CIA and the US military . Zweiausendeins, Frankfurt 2005, ISBN 3-86150-729-3 .

- Cecilia Menjivar, Nestor Rodriguez (Eds.): When States Kill: Latin America, the US, and Technologies of Terror (Paperback), Texas University Press, Austin 2005. Table of Contents

- Marnia Lazreg: Torture and the Twilight of the Empire. From Algiers to Baghdad , Princeton UP, Princeton, NJ / Oxford 2008, ISBN 0-691-13135-X .

Historical-sociological and psychological study to answer the question why torture is justified in one of all people on terror . - Manfred Nowak : Torture: The everydayness of the incomprehensible. Kremayr & Scheriau, 2012, ISBN 978-3-218-00833-4 .

Discussion about torture

- Winfried Brugger: From the unconditional prohibition of torture to the conditional right to torture? In: JZ 2000, pp. 165-173.

- Jan Philipp Reemtsma : Torture under the rule of law? Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-936096-55-4 .

- Gerhard Beestermöller (ed.): Return of the torture. The rule of law in the twilight? Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-54112-7 .

- Frank Meier: Is the prohibition of torture absolute? Ethical problems of police coercive measures between respect and protection of human dignity. Mentis, Münster 2016, ISBN 978-3-95743-043-4 . Anthology on the legal and social science aspects of the torture discussion in Germany.

- Björn Beutler: Torture for interrogation purposes is punishable. With special consideration of constitutional and international law. Peter Lang, Frankfurt a. M. 2006, ISBN 3-631-55723-X .

- Alexander Stein: The prohibition of torture in international and national law. Considering its enforcement tools and its absolute character. Publishing house Dr. Kovac, Hamburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-8300-3199-4 .

- Shane O'Mara: Why Torture Doesn't Work: The Neuroscience of Interrogation. Harvard University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0-674-74390-8 .

Victim of torture

- Angelika Birck, Christian Pross, Johan Lansen (eds.): The Unspeakable - Working with Traumatized People in the Treatment Center for Torture Victims Berlin. Berlin 2002.

- Urs M. Fiechtner , Stefan Drößler, Pascal Bercher, Johannes Schlichenmaier (eds.): Defense of human dignity. The work of the Treatment Center for Torture Victims Ulm (BFU). 2nd edition, Volume 5, Chain Break Edition, Ulm / Stuttgart / Aachen 2015.

definition

- Amnesty International Section Switzerland: What is Torture?

- Torture definition according to Angelika Birck (* November 16, 1971; † June 7, 2004) from the Treatment Center for Torture Victims Berlin, July 9, 2004.

- Entry in Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

Different aspects

- Torture experts - The secret methods of the CIA , on GoogleVideo (Documentation of the SWR from July 9, 2007)

- Torture in the Rule of Law - The Federal Republic after the Jakob von Metzler kidnapping case - student paper prepared as an e-book, University of Gießen, 2004

- KUBARK manual, German (PDF; 448 kB) and English (PDF file; 437 kB)

- Daniela Haas: Torture and Trauma. Therapeutic approaches for those affected. BIS-Verlag, Oldenburg 1999 (= diploma thesis, University of Oldenburg, 1997)

- Christian Bommarius: Resistance to Torture. Ex-US military prosecutor honored by lawyers' association. In: Berliner Zeitung . November 16, 2009, accessed June 10, 2015 .

- ID control: Calculated pain, column, evolver.at , February 2005

- "Operation nasal tube". UN investigators are investigating new allegations from Guantánamo - and are prevented by the US. In: The time . No. 48, November 24, 2005.

- The prohibition of torture. A clear rule and a paradoxical practice. , Deutschlandradio , December 29, 2005, by Dieter Rulff, also as an mp3 file

- Zypries for using torture confessions. ( Memento from August 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Netzeitung , January 25, 2006

- Jan Philipp Reemtsma : The grimace of torture. Cicero , March 2006

- Torture transnational? Depictions of violence in American and German television thrillers. Article by Christoph Classen with film clips on Zeitgeschichte-online

- "Waterboarding for 9/11 Chief Planners - Severe and Persistent Damage". Interview with Gisela Scheef-Maier, psychotherapist at the Treatment Center for Victims of Torture . T-Online, April 2014.

Documentaries

- Taxi to Hell (2007)

- Standard Operating Procedure (2008)

See also

- Operation Condor (US intelligence services in South America (1970s))

- Action of Christians for the Abolition of Torture ACAT Germany

Web links

- Panel discussion “May the state torture?” With Winfried Brugger and Bernhard Schlink, HFR 4/2002

- Herbert Lackner : In the antechambers of Hell. The startling diary of the UN anti-torture commissioner Manfred Nowak. In: profile from February 29, 2012

Individual evidence

- ↑ Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the “Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment” ; Retrieved January 3, 2014

- ↑ Amnesty report shows: Torture is common in many countries. Retrieved July 10, 2020 .

- ↑ Steven Miles, Telma Alencar, Brittney Crock Bauerly: Punishing physicians who torture: a work in progress . In: Torture: quarterly journal on rehabilitation of torture victims and prevention of torture . tape 20 , January 1, 2010, p. 23–31 ( researchgate.net [accessed July 10, 2020]).

- ↑ Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment of December 10, 1984. (PDF; 67 KB) In: BGBl. 1990 II p. 246. Retrieved on May 9, 2019 .

- ↑ The legality of rescue torture affirming, for example, Kühl, Kristian : Strafrecht Allgemeine Teil, 7th edition 2012, p. 191 ff.

- ↑ BGE 137 IV 269 . Case Law (DFR). January 19, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ↑ Joachim Lehrmann : For and against the madness. Witch persecution in the Hildesheim Monastery. , and "A contender against the witch craze". Lower Saxony's unknown early scout (Justus Oldekop). Lehrte 2003, ISBN 978-3-9803642-3-2 , pp. 194-239.

- ↑ Thomas Weitin: Truth and Violence. The Torture Discourse in Europe and the USA. transcript Verlag, Bielefeld 2010, ISBN 978-3-8376-1009-3 .

- ↑ Karsten Altenhain, Nicola Willenberg: The history of torture since its abolition . V&R unipress GmbH. 2011. ISBN 3-89971-863-1 (p. 28)

- ↑ Cesare Beccaria: Dei delitti e delle pene , with an afterword by Voltaire , 1764

- ↑ Richard Wrede, Corporal punishment for all peoples from the earliest times to the end [!] Of the nineteenth century. Cultural history studies, Ndr. D. Edition 1898, Frankfurt a. M. 1970, p. 2.

- ↑ Franz Helbing, The Torture. History of torture in criminal proceedings of all peoples and times, 2 vol., Ndr. D. Edition Gross-Lichterfelde-Ost 1910, Augsburg 1999, vol. 1, p. 1 and Vol. 2, p. 256.

- ↑ Quoted from: Robert Zagolla, In the Name of Truth. Torture in Germany from the Middle Ages to Today, Berlin 2006, p. 111.

- ↑ Robert Zagolla, In the Name of Truth. Torture in Germany from the Middle Ages to the Present, Berlin 2006, p. 121.

- ↑ Michael Eggestein and Lothar Schirmer : Administration under National Socialism. Publishing house for training and studies in the Elefanten Press, Berlin 1987, p. 115 ff

- ↑ Cf. Karl Wilhelm Fricke: The GDR State Security. Development, structures and fields of action . Cologne 1989, pp. 135-136.

- ↑ Peter Wensierski, DER SPIEGEL: Stasi secret prison - DER SPIEGEL - history. Retrieved June 3, 2020 .

- ↑ Final report of the Comisión Nacional de Prisón Política y Tortura , 2005, p. 243 ( PDF ( Memento of February 6, 2009 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ www.wsws.org

- ^ ZDF.de - Torture in the Bundeswehr ( Memento from December 10, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ www.123recht.net

- ↑ Winfried Brugger: May the state torture as an exception? In: Der Staat 35 (1996), pp. 67–97 .

- ↑ Niklas Luhmann: Are there still indispensable norms in our society? Müller, Heidelberg 1993, ISBN 3-8114-6393-4 .