Mennonites

Mennonites are an evangelical free church that goes back to the Anabaptist movements of the Reformation . The name is derived from the theologian Menno Simons (1496–1561) , who came from Friesland . As Anabaptists, the Mennonites are historically closely linked to the Hutterites and Amish .

Persecution and legal restrictions in Europe mainly led to the emigration of Mennonites and other Anabaptists to Eastern Europe and North America between around 1715 and 1815. Despite the persecution, the Free Church in Central Europe was able to hold out continuously. Today the Mennonites are spread all over the world.

Surname

The term Mennonites was first documented in writing in 1544 in a letter from the East Frisian authorities. It goes back to the Dutch reformer Menno Simons. Simons was a Catholic theologian and converted to the radical Reformation Anabaptist movement around 1536 . Menno Simons soon assumed a leading position within the still young Anabaptist movement and had a lasting impact on the theology and history of the Reformation Anabaptists.

At the beginning, the term was mainly used from the outside to describe those North German-Dutch Anabaptists who referred to Menno Simons. Later, Anabaptists from other regions also took over the name, so that most Anabaptists are still known as Mennonites today. The term was given a special meaning as a protective name in order to circumvent the republic-wide Anabaptist mandate, which prescribed the death penalty for Anabaptists in the Roman-German Empire . In this way, princes could settle Anabaptists in their territories without formally breaking the Anabaptist mandate. Menno Simons thus (unintentionally) took on the role of the namesake of the Mennonites. However, he cannot be regarded as the founder of the movement, as the Anabaptist movement founded by Konrad Grebel and Felix Manz , among others, had existed for several years when he joined.

The Anabaptist movement itself today consists of the Mennonites, the Hutterites and the Amish . In the USA the Schwarzenau Brethren are also counted among the Anabaptists. In a denominational sense, free churches that emerged later, such as the Baptists , are not to be counted among the Anabaptists and form their own denominational groups.

Today the Mennonites are also known as Baptists (in the Netherlands as Doopsgezinde ), Old Anabaptists , Old Evangelical Baptists (in Switzerland) or as Evangelical-Mennonite Free Church . In the German-speaking countries, the description Anabaptist-Mennonite is often found .

history

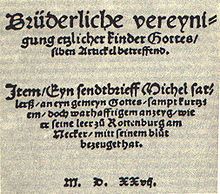

Reformation time

The history of the Mennonites begins with the Anabaptist movement, which originated in Zurich around 1525 in the context of the Swiss Reformation . As a result, this movement spread and the first Anabaptist communities also emerged in southern Germany. The Anabaptists demanded a life to follow Jesus and saw - like the reformers Luther and Zwingli - the Bible as a decisive source of Christian faith. In contrast to Luther and Zwingli, however, they came to the conclusion that baptism should only be practiced if those to be baptized consciously choose to believe ( believer's baptism ). This was rejected by both the Catholic Church and the Lutheran and Reformed reformers, who continued to adhere to infant baptism . The Anabaptists criticized the state of the established church and showed solidarity, for example, with the demands of the rebellious peasants for their own pastors to be chosen. Both the rulers and the major churches saw in the Anabaptists a threat to the authority of state and church. A comprehensive persecution of the still young movement soon began, which was also supported by the Lutheran and Reformed sides. Zwingli called on the city council of Zurich, for example, to exterminate the Anabaptists with all available means. Luther saw ghosts and heretics in the Anabaptists and advised them to be judged unheard of and irresponsible .

Even in its early years, the Anabaptist Movement itself was a pluralistic movement consisting of several directions. In addition to the more biblical-pacifist-oriented Swiss Anabaptists , the Upper German Anabaptists, some of whom were still influenced by Thomas Müntzer and Christian spiritualism , and communitarian groups such as the Hutterites also developed . Under the impression that the Anabaptist persecution was already beginning, Southwest German and Swiss Anabaptists came together in February 1527 and decided on the Schleitheim Articles , which summarized key principles such as non-violence or the model of a free church outside of state structures. In August of the same year a larger Synod of Baptism took place in Augsburg . Many of the Anabaptists who met in Augsburg were later murdered for their beliefs, which is why the synod is known to this day as the Augsburg Synod of Martyrs . In 1529 the Anabaptist mandate was finally passed , which stipulated the death penalty for the Anabaptists across the empire .

With Melchior Hofmann , the ideas of the Reformation Anabaptist movement also spread in northern Germany and the Netherlands, where they partly took over the legacy of the pre-Reformation sacramentarians . Part of the Dutch-North German Anabaptist movement , however, radicalized itself under the impression of increasing persecution and apocalyptic ideas, which led to the events in Münster . Others, like the theologian Menno Simons, who converted to the Anabaptists in 1536, emphasized the principle of Christian nonviolence. After the overthrow of the militant Anabaptists in Münster, Simons finally collected large parts of the Dutch-North German Anabaptist movement and, based on the Sermon on the Mount, formulated a consciously pacifist theology, as it was already formulated in the Schleitheim articles. Simons gained great influence within the North German-Dutch communities, so they were also named as Mennonites. Finally, the name was also used by Anabaptist communities in the Swiss-South German-French region. The new name also offered some protection; because there was no formal death penalty on him.

Further developments

In contrast to the northern Netherlands , which introduced religious tolerance among the Orange in 1579 , the Mennonites were further oppressed in most European territories, such as Switzerland and the southern Netherlands, and threatened by persecution, expulsion, torture and death. They were therefore among the first Germans to emigrate to North America, where a large number of Mennonites of European descent still live today.

Especially in the 18th century, many Palatinate Mennonites emigrated to Pennsylvania , where Mennonites from the Krefeld area had founded the place Germantown (Deitscheschteddel) with other German emigrants as early as 1683 . Some of them, old-order Mennonites who drove in carriages , still speak Pennsylvania German today . Among the Mennonites who emigrated to America, the first German edition of the Martyr's Mirror was also produced .

The Anabaptists who remained in Europe lived in the country as the silent ones in the following generations . Swiss Mennonites, for example, settled in seclusion in the Emmental and in the Bernese Jura . Many also emigrated to Alsace and, to a lesser extent, the Netherlands. In cities like Zurich or Basel, the Mennonites were exterminated and driven out.

As early as the 16th century, many Dutch Anabaptists settled in Royal Prussia , which belonged to the Polish crown , where they cultivated the lowlands of the Vistula - Nogat Delta. They built dikes and canals and in this way were able to use the land for successful agriculture. As they brought economic benefits to cities and landowners, their religion was tolerated.

North Germans in particular joined these Mennonite settlers, whose Dutch and Frisian dialects gradually became more and more similar to the north-east German dialects of their new homeland. High German, instead of Dutch, was not adopted until the middle of the 18th century. However, they were only able to obtain full civil rights in the 19th century.

Differences of opinion soon arose among the Dutch and North German Mennonites, for example about how to deal with the ban , and many communities split into Waterland, Frisian and Flemish communities. Later, with the Lammists and the Sonnists, more liberal and more conservative communities emerged.

Mid-17th century, the group which formed Dompelaars (submersion), which is three times for baptism immersion demanded. Most congregations later reunited, however, when their numbers no longer increased due to increasing assimilation but declined.

Under the Swiss and Alsatian Mennonites, the Amish split off in 1693 and named themselves after their founder Jakob Ammann . Jakob Ammann stood for a stronger isolation from the world and strongly emphasized the strict observance of the community order as well as the exclusion and avoidance of those who do not adhere to the rules. Amish today live almost exclusively in North America, as the communities that remained in Europe assimilated more and more to the majority society and then either rejoined the Mennonites or transformed themselves into Mennonite communities.

The Mennonites living on the Vistula came under Prussian rule after the First Partition of Poland in 1772 , which became a problem mainly because of the Prussian military service. From 1789 many emigrated to New Russia and later from there to other parts of Russia , where they became an ethno-religious group , the Russian Mennonites. This is where the Mennonite Brethren Congregations, influenced by Pietism , came into being after 1860 .

After the introduction of Russian conscription in 1874, a third of them, especially the more conservatives, emigrated to North America, where new communities and settlements emerged , especially in Kansas and Manitoba . The two Canadian cities Steinbach and Winkler, for example, can be traced back to the Mennonite community movement Kleine Gemeinde , which originated in today's Ukraine .

In the 20th century, agricultural settlements were founded in Latin America , from 1922 in northern Mexico and from 1927 in Paraguay . From these two countries in particular, they built their own colonies from 1954 in Bolivia , from 1958 in Belize , from 1984 in Argentina , from 2015 in Peru and from 2016 in Colombia . To this day, almost all Russian mennonites in Latin America speak their West Prussian dialect Plautdietsch .

Due to the missionary work of the more liberal North American Mennonites, most of the Mennonites now live on the African continent, but almost all of them are converted Africans .

Only a few of the Russian mennonites still live in Russia today, but most of them came to Germany after 1990, which is also due to the suppression of the Mennonites under the communist rulers. As early as the 1920s and 1930s and again after 1945, several thousand Russian-German Mennonites left Russia and mostly went to Canada and Latin America. The Great Terror under Stalin in the 1930s claimed a particularly large number of lives . Many Russian-German Mennonites were arrested, mistreated, murdered or deported to labor camps, where many perished cruelly.

It is estimated that around 35,000 of the 125,000 or so Mennonites still settling in the Soviet Union at that time were killed in the years immediately prior to World War II.

Today more than 200,000 people of Russian Mennonite origin live in Germany, of whom only some have joined Mennonite communities. Nevertheless, the number of Mennonite communities founded by Germans from Russia now clearly exceeds that of the long-established ones.

time of the nationalsocialism

This section primarily describes the situation in Germany at that time, for further information see also: Free churches in the time of National Socialism

Many German Mennonites remained passive during the Nazi era . Only a few, such as Christian Neff , openly criticized or hid Jews underground, while others support National Socialism . The umbrella organization of the East and West Prussian Mennonites already showed open support for the new regime in a telegram to Hitler in September 1933 , and the umbrella organization of the North German Mennonites released the young men from the practice of refusing military service even before the introduction of compulsory military service . which in both cases clearly detached them from their pacifist roots. There was also no cooperation with the Confessing Church beyond occasional contacts. This also led to the later social scientist Johannes Harder leaving the Mennonites for several years and instead becoming involved within the Confessing Church.

The German Mennonites also did not take part in the founding of the International Mennonite Peace Committee in Amsterdam in 1936. The evacuation of the Bruderhof of the Neuhutterer in the Rhön by the SS in 1937 remained without a sign of protest by the German Mennonites. Instead, help came from Dutch Mennonites.

post war period

Immediately at the end of the war, the Mennonites living in the Prussian area were particularly affected by the expulsion . Many young North American Mennonites came to Germany as conscientious objectors (pax boys) and helped with the reconstruction. Mennonites were also instrumental in founding CARE International . Later the Mennonite Central Committee was one of the founders of the Eirene Peace Service . As a reaction to the events of the Nazi era and its own guilt, the pacifist legacy was emphasized again after the war. In 1956 , in rejection of rearmament, German Mennonites founded the German Mennonite Peace Committee .

A systematic coming to terms with the time of National Socialism and one's own guilt did not begin in Germany until the 1970s. Five years after its founding, the Working Group of Mennonite Congregations published a confession of guilt towards the war victims and Jews in 1995.

Mennonites in the GDR

After the end of the war and the expulsion, the Mennonite community work in Germany concentrated mainly on the western part. After the division of Germany, however, there were also active Mennonites in the GDR . For the most part, they were displaced persons (referred to as resettlers or new citizens in the GDR diction ) from the former German eastern areas , and some were (native) members of the previously existing community in Berlin . Not least because of the critical line of the GDR leadership, however, numerous Mennonites moved after a short time to West Berlin, West Germany or emigrated to North America. Against this background, it is difficult to name a specific number of Mennonites in the GDR. A number of 1,100 is given for 1950, which sank to only 287 by 1985, which means that the GDR Mennonites had to accept a significant loss of membership.

Against the background of the many Mennonite refugees from the GDR , the Ministry of the Interior prepared a ban on Mennonites in 1951. A corresponding draft, which would have prohibited any practice of Mennonite community life and made it punishable, had already been drawn up, but was no longer implemented after 1952.

After the construction of the wall in 1961, the connections between the GDR Mennonites and the Berlin Mennonite community in the western part of the city were broken and a separate community was formally established for the GDR area, which was recognized by the state in 1962 and for many years by Walter Janzen was supervised as a preacher. Services took place in the Protestant Pentecostal Church in Berlin and in Rostock, Halle, Erfurt and other places in Eastern Germany. The Mennonites in the GDR were ecumenically involved in the Working Group of Christian Churches in the GDR. In 1984 six Mennonites from the GDR were able to take part in the Mennonite World Conference in Strasbourg.

For further Anabaptist-Mennonite history see also the chronological table on the history of the Anabaptists and Mennonite emigration

Alignments

The Mennonites, together with the Amish and Hutterites, make up the Anabaptist denominational family. In North America, the Pietist-Anabaptist Schwarzenau Brethren are also counted among the Anabaptists.

There is a relatively wide range of orientations within the Anabaptist-Mennonite denomination. There are both liberal , pietist , evangelical and traditionalist churches. Institutionally also, in addition to the general Mennonite Mennonite Brethren Churches , the Evangelical Mennonite Conference (Small community) , the Brethren in Christ and the traditionalist Mennonites old regulations (Old Order Mennonites) and -Mennonite Old Colony Mennonites (Old Colony Mennonites) are called. The latter groups are found exclusively in North and South America.

The common bond of all these groups consists in the common history (origin from the Reformation Anabaptist movement) and common theological basic convictions (such as confessional baptism, non-violence or community autonomy). In addition, different positions have developed on many points (such as the form of baptism or the ordination of women ). Groups like the Mennonites of the old order and the old colonists Mennonites only adopt technical innovations after careful examination and if they do not endanger their communities. These traditionalists represent only a small but steadily growing part of the world-wide spread Mennonites.

With the exception of the conservative old colonial Mennonites and the Mennonites of the old order, the majority of the Mennonite congregation associations work together in international contexts such as the Mennonite World Conference, the International Committee of the Mennonite Brethren or the aid organization Mennonite Central Committee.

In the German-speaking area there are congregations and congregational associations of the general Mennonites as well as the Mennonite Brethren congregations.

distribution

The Mennonites are now spread all over the world. According to the Mennonite World Conference , there were around 2.1 million Anabaptists worldwide in 2015. Regional focuses include the mid-north of the United States and the center of Canada ( Manitoba ), Paraguay, Belize, the Congo and Ethiopia.

Germany

In Germany today there are over 40,000 Mennonites in around 200 communities. There are several Anabaptist-Mennonite community associations. To date, however, there is no central or coordinating body for the various municipal associations at national level.

The Association of Mennonite Congregations in Germany (AMG), which was founded in 1990, comprises congregations, some of whose history dates back to the Reformation. In formal terms, the AMG consists of the three autonomous regional associations, the Association of German Mennonite Communities (VDM) in northern Germany, the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Südwestdeutscher Mennonitengemeinden (ASM) in southwestern Germany and the Association of German Mennonite Communities (VdM) in southern Germany.

There is also the Working Group of Mennonite Brethren in Germany (AMBD), which was founded in 1970, as a union of the first Mennonite Brethren in Germany.

After the immigration of Russian-German Mennonites, other parishes and parish associations emerged in parallel, such as the Working Group for Spiritual Support in Mennonite Parishes (AGUM), founded in 1978, and the Bund Taufgesinnter Gemeinde (BTG) founded in 1989 . The AMG and the AGUM belong to the church Mennonites, the AMBD and the BTG to the Mennonite Brethren.

There are also other associations and completely independent municipalities. The communities of from Russia coming Evangelical Christians-Baptists often have a Mennonite background. The Mennonites with Russian-German roots now form the majority of the German Mennonites. The following table provides an overview of the currently existing alliances:

| Association | Number of parishes | Number of members |

|---|---|---|

| AGAPE-Gemeindewerk Mennonitische Heimatmission e. V. (AGW-MHM) | 4th | 200 |

| Association of Mennonite Brethren in Germany V. (AMBD) | 15th | 1.611 |

| Working group of Mennonite communities in Germany K. d. ö. R. (AMG) | 54 | 5,185 |

| Working group for spiritual support in Mennonite congregations (AGUM) | 19th | 5,728 |

| Brotherhood of Christian Congregations in Germany (BCD) | 66 | 20,000 |

| Association of Baptized Churches (BTG) | 26th | 6,882 |

| Independent Mennonite Brethren Congregations (not an association) | 25th | 4,800 |

| Independent Mennonite Congregations (not an association) | 13 | 445 |

| Association of Evangelical Free Churches of Mennonite Brethren in Bavaria V. (VMBB, is in connection with the AMBD) | 6th | 318 |

| WEBBplus communities (working group of the communities in Wolfsburg, Espelkamp, Bechterdissen, Bielefeld, Niedergörsdorf) |

5 | 1,600 |

| Other Mennonite congregations within the Russian-German umbrella organizations, Arbeitsgemeinschaft Evangelicaler Congregations (AeG), Working Group of Free Congregations / Service Community of Evangelical Congregations (AGFG / DeG), Association of Evangelical Christians-Baptists (VEChB) and Brotherhood of Evangelical Christians -Baptists (BEChB) |

unknown | unknown |

Most of the communities today exist in West and South-West Germany. The focus here is on the regions of Baden and Palatinate , where descendants of the Anabaptists who were expelled from Switzerland still live today. Furthermore, many Russian-German Mennonites have settled in Westphalia and Lippe . The front of the expulsion in Gdansk space communities located no longer exist today.

Austria

The Mennonite congregations in Austria are now united in the Mennonite Free Church of Austria . In order to be recognized as a church community by the Austrian state, the Austrian Mennonites joined together with other free churches in 2013 to form an umbrella organization of free churches in Austria . Anabaptist communities already existed in Tyrol and in cities such as Linz and Steyr during the Reformation, but they were later expelled. Today the community has around 400 members in 5 communities.

Switzerland

The fourteen congregations of the Conference of Mennonites in Switzerland with their 2500 members are all located in northwestern Switzerland . The largest communities are those in the Bernese Jura, in the Emmental, in Muttenz and around Neuchâtel. The Anabaptist training and conference center Bienenberg (formerly the European Mennonite Bible School) is located in Liestal . The Swiss Mennonites are also known as Old Anabaptists.

Other countries

There are currently around 2.1 million Anabaptists in 80 countries worldwide (as of 2015). Most of these (37%) live in Africa . The USA and Canada live 32%, Asia and Australia 16%, and Latin America and the Caribbean around 10%. In Europe, where the Mennonite movement originated, only about 4% of the Mennonites live today.

Mennonite alliances and churches within Europe can be found in the Netherlands, France and Luxembourg, among others.

The Mennonite congregations in the Netherlands are united in the Algemene Doopsgezinde Sociëteit (Baptism-Minded Society) .

The Mennonite communities in France and Belgium are united in the Association des Églises Évangéliques Mennonites de France . Especially in the region around Montbéliard (German Mömpelgard ) there are Mennonite communities with some of their own cemeteries. In Luxembourg there are two Mennonite congregations with around 110 members who are united in the Association Mennonite Luxembourgeoise . The Italian Mennonites are networked in the Chiesa Evangelica Mennonita Italiana and the Spanish in the Asociación de Menonitas y Hermanos en Cristo en España .

Well-known Mennonite churches in North America are the Mennonite Church Canada, founded in 2000, and the Mennonite Church USA, founded in 2002 . In addition to these, there are also Mennonite Brethren Churches , the Brethren in Christ influenced by the Tunkers and traditionalist-conservative groups such as the Old Mennonites (Old Order Mennonites) and Old Colony Mennonites . The last two groups have some things in common with the Amish. In the early years, the center of Mennonite emigration to America was primarily Pennsylvania .

With the emigration to North America and later also to Latin America, some larger Mennonite settlements and communities emerged here. The colonies of Menno , Neuland and Fernheim in Paraguay are best known today . Also significant are the settlements in Argentina (Colonia del Norte, Colonia Pampa de los Guanacos), Uruguay ( El Ombú , Gartental , Delta, Colonia Nicolich ), Brazil (Colonia Nova and Colonia Witmarsum) and Bolivia (Campo Chihuahua, Colonia Durango, Colonia Manitoba). In Mexico , Mennonites settled in the states of Chihuahua , Durango , Zacatecas, and Campeche . Mennonites mainly from Canada also settled in neighboring Belize . Some of the Mennonites settling in Latin America form completely autonomous congregations, but for the most part have come together in larger national congregations such as the Association of Mennonite Congregations of Paraguay . For many Mennonites living in South and Central America, the Low German variety Plautdietsch (in addition to High German, Spanish and some indigenous languages) is still a colloquial language.

Mennonite community associations were also formed in Africa and Asia through missions. Congo , Ethiopia and India should be mentioned in particular .

Many of the Mennonites in North and South America as well as in Europe still have a common ethnic origin, as the ancestors from German-speaking regions were predominantly Mennonites. This applies, for example, to almost all traditionally living Mennonites in America who still drive a carriage today and speak a German dialect. Mennonite communities in Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and partly also in Latin America, on the other hand, only emerged through the mission of Mennonite works from the end of the 19th century and above all after the Second World War. Many congregational associations in Europe, North America and many of the congregations in Africa and Asia that came into being through the mission often differ little in their cultural understanding or external perception from other Protestant free churches.

Principles

The Mennonites share the four solos with the other Reformation churches ( through scripture , faith , grace, and Christ alone ). As a result, essential characteristics are the baptism of believers , the rejection of the oath and military service , community autonomy , the priesthood of all believers and the demand for the separation of state and church . The Bible is decisive for faith and life . The Sermon on the Mount plays a central role in the Mennonite understanding of faith .

The Sermon on the Mount and the Epistle of James also explain the Mennonite commitment to peace and non-violence . The connection between ethics and ecclesiology is characteristic of Mennonite theology. The Mennonites are traditionally assigned to the peace churches . Many Mennonites are diaconal in political crisis areas.

Their history explains the advocacy of freedom of belief and conscience . The Mennonites have consciously united as a free church outside of state structures and, like other free churches, see themselves as a voluntary church . They emphasize the individual's freedom of choice and reject predestination as it is particularly represented in Calvinism .

There are no sacraments in the sense of healing acts. Instead, baptism and the Lord's Supper are understood as covenant signs. The Lord's Supper is understood symbolically.

There are different positions today, for example on the ordination of women , the acceptance of homosexuality and divorces . Progressive and conservative directions have developed here.

The following points (among others) can be mentioned as principles of Anabaptist-Mennonite theology and practice:

- Conversion : A conscious choice to believe comes before baptism. According to Jn 3,1-23 EU, conversion means the conscious turning away from life under the power of sin and turning to God

- Baptism of faith : Baptism is an expression of the conscious decision of the individual to follow Jesus. Infant baptisms are rejected and not practiced. Individual decision to follow Jesus. Baptism can be practiced by immersion, dousing, or sprinkling. Some Mennonite congregations also baptize outside of the churches in lakes or rivers. Baptism classes are usually held before baptism . Baptism is always a public confession of conversion and rebirth towards God and man. Baptism seals conversion.

- Child blessing : Instead of child baptism, a child blessing is optionally possible with reference to Mt 19 : 13-15 EU . The practice of blessing children was already described in a letter from the Anabaptist reformer Balthasar Hubmaier to Johannes Oekolampad on January 16, 1525. Also Pilgram Marpeck mentioned the ceremony 1,531th

- Lord's Supper : The Lord's Supper is celebrated as a memorial meal among the baptized believers. It is intended to commemorate the sufferings and death of Christ. At the same time, the communal aspect of the Lord's Supper should be emphasized. Bread and wine are understood as symbols, transubstantiation is rejected. In some communities the washing of the feet before the sacrament is still common.

- Lay minister : The priesthood of all believers is practiced. Accordingly, lay preachers are often active in Mennonite congregations in addition to trained theologians .

- Municipal Discipline : Dealing with sins, after Mt 18.15 to 17 EU leading up to the ban from the community. By confessing sin , sinners can be accepted back into the church. In the discussion about the ban in the 17th century, conservative and liberal positions developed.

- Oath : According to Mt 5,33-37 EU the Mennonites reject the swearing of oaths .

- Peace : The peace aspect, which goes back to the Sermon on the Mount Mt 5 EU , is of great importance , even if defenselessness has historically not always been respected.

The Schleitheim Articles, adopted on February 24, 1527, are among the earliest creeds . Other creeds emerged later, such as the Dordrecht Confession of 1632, which originated in the Netherlands and was later adopted by many Mennonite communities and churches. With them the Mennonite congregations tried again and again to formulate a common creed. These confessions are not decisive for the belief of the individual.

See also Confessions of the Anabaptists

practice

The way of life and religious practice in the individual parishes sometimes differ greatly from one another. What they all have in common is the Anabaptist tradition.

The organization of the services is not tied to any fixed liturgy . However, the sermon is always at the center of an Anabaptist-Mennonite worship service . The churches or prayer houses are designed as simple sermon churches with a central pulpit . The sermon can be given by trained pastors as well as lay preachers. Singing together plays a major role, and the music can be modern as well as traditional. According to the Reformed understanding, the Lord's Supper is practiced as a memorial meal . Instead of a central altar, there is a communion table in Mennonite churches . In connection with the Lord's Supper, the washing of the feet is also practiced in some communities . Baptism can be performed by complete immersion, dousing (affusion), or sprinkling (aspersion). Services take place in prayer houses, churches or in private homes. In addition to the church services, smaller groups often meet in private house groups . Titles are not used among themselves.

The community is democratic. Decisions are made by the community assembly. The elders (church leaders or church councils), preachers or pastors and deacons are also elected from among their number . The communities are financed exclusively through voluntary donations and membership fees.

A certain simplicity in the lifestyle is also characteristic. Some Orthodox groups, such as those in America , Russia or Kyrgyzstan, live at a distance from the surrounding society, are skeptical of modern technology and gather on Sundays as house congregations in private houses instead of churches. These groups are close to the Amish in many ways. Most Mennonites, however, live modern and cosmopolitan.

Mennonites are often involved in diakonia and social projects. Peace policy engagement plays a major role to this day. The German Mennonite Peace Committee was founded in Germany in 1956 . Internationally, Mennonites work in the Christian Peacemaker Teams founded together with other peace churches . In addition, aid organizations such as the Mennonite Central Committee , the Mennonite Aid or the Mennonite Disaster Service ( Mennonite Disaster Service ) were founded to support those in need, regardless of their religion . Mennonites also work in fair trade through the Ten Thousand Villages project . Aid projects are supported by volunteers from the Christian Services (Mennonite Voluntary Service) .

structure

The Mennonite congregations and churches have a congregational structure, which means that the individual congregations are autonomous. At the regional, national and international level, however, the Mennonites have often come together to form working groups and associations. The local community still plays the decisive role in the Mennonites' self-image. The leadership of a church is usually in the hands of elders, preachers, and deacons.

In 1990 the working group of Mennonite congregations was founded in Germany, which coordinates the work of many Mennonite congregations in Germany. There is also the working group of Mennonite Brethren Congregations and the Federation of Baptist Congregations. In Switzerland there is the Conference of the Mennonites of Switzerland and in Austria the Mennonite Free Church of Austria.

Internationally, 100 Mennonite churches and working groups around the world are united in the Mennonite World Conference . At the European level, the Mennonite-European Regional Conference takes place every six years . Mennonite Brethren Congregations have been networked with one another on an international level since 1990 in the International Committee of Mennonite Brethren (ICOMB) .

Ecumenism

Most Mennonites feel connected to other Christians . Accordingly, Mennonites work together with other Protestant free churches, for example in the Association of Evangelical Free Churches (in Germany), in the Association of Evangelical Free Churches and Congregations in Switzerland and in the Union of Free Churches in Austria . Many local congregations are members of the Evangelical Alliance . The Working Group of Mennonite Congregations in Germany represents the German Mennonites in the Working Group of Christian Churches in Germany . Internationally, many Mennonite churches are also members of the World Council of Churches .

At the end of the 20th century, several interdenominational dialogues took place with other Christian communities and churches. These include the Mennonite-Lutheran Dialogue and the Mennonite-Catholic Dialogue. Between 1989 and 1992 a first Mennonite-Baptist dialogue took place with representatives of the Baptist World Federation and the Mennonite World Conference. In 2011 and 2012, there was also the first bilateral dialogue between Mennonites and the Seventh-day Adventists that emerged in the 19th century .

However, there are also conservative Mennonites who reject cooperation with other churches and congregations and instead emphasize the autonomy of the individual congregation.

Catholic Church

Between 1998 and 2003, several official meetings between representatives of the Mennonite World Conference and the Vatican took place under the heading Towards a Healing of Memories . They were the first official meetings between the two churches since the 16th century.

Evangelical regional churches

There have been several dialogues with Lutheran and Reformed churches since the end of the 20th century. In Germany, for example, the first talks with representatives of the Lutheran regional churches took place between 1989 and 1992. Between 2006 and 2009, a dialogue process took place in Switzerland under the heading Christ is our peace with the Federation of Swiss Evangelical Churches . An international Lutheran-Mennonite study commission also met until 2009. In the same year the Council of the Lutheran World Federation expressed deep regrets and sorrow for the injustice committed and asked the Mennonites for forgiveness. In July 2010, the General Assembly of the Lutheran World Federation in Stuttgart agreed to this declaration and, standing or kneeling, apologized for the brutal persecution in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Nevertheless, there are always irritations. In the discussion on the legitimacy of violence in May 2011, the EKD Council Chairman Nikolaus Schneider accused the peace churches, and in particular the Mennonites, of “running away”. The Augsburg Confession , which condemns the Anabaptists for their nonviolence and legitimized the persecution of the early Anabaptists in Protestant territories, is still a valid confession of the Evangelical Church in Germany . In 1992, the VELKD declared that the rejection of the peace churches in the Augsburg Confession did not affect the Mennonites today "to the same extent" as the Anabaptists of the Reformation period.

Quaker

Relations with the Quakers who emerged in the 17th century are traditionally good, even if the intensity has fluctuated greatly. At the first meeting of the two denominations in the Dutch-North German area, verbal riots occurred in some cases. From the beginning there were also strong conversion movements between the two groups. This led, among other things, to a continuing conflict among historians as to whether the 13 Krefeld families who emigrated to Pennsylvania under the leadership of the German Quaker Franz Daniel Pastorius were Quaker or Mennonite. In some cases there were also non-denominational partnerships, jointly drafted documents as well as jointly used meeting houses. The persecution of both groups also accelerated cooperation. With theological topics such as peace work, emphasis on the laity, understanding of the sacrament and rejection of oath and military service, there are points of contact to this day.

Known Mennonites (selection)

- Menno Simons (1496–1561), Frisian pastor and namesake

- Jacob Izaaksoon van Ruisdael (1628–1682), Dutch landscape painter from Haarlem

- Johann Eimann (1764–1847), German colonist and notary

- Jan ten Doornkaat Koolman (1773–1851), Frisian merchant and liquor manufacturer from the north

- Henry Voth (1855–1931), American pastor and missionary to the Cheyenne , Arapaho, and Hopi ; one of the greatest connoisseurs of the Hopi and its language.

- Annie Clemmer Funk (1874–1912), American Mennonite missionary in India

- Wilhelmine Siefkes (1890–1984), Low German teacher and writer from Leer

- John Howard Yoder (1927–1997), American Mennonite theologian and ethicist

- Anni Dyck (* 1931), German Mennonite missionary and writer

- George W. Peters (1907–1988), Russian-German Mennonite missiologist

- Vincent Harding (1931–2014), American civil rights activist and historian

- Rudy Wiebe (* 1934), Canadian writer of Russian-German origin

- Howard Zehr (* 1944), American sociologist and professor of restorative justice

- Robbert Adrianus Veen (* 1956), Dutch Mennonite theologian

- Fernando Enns (* 1964), German-Brazilian Mennonite theologian, member of the WCC central committee

- Abraham Fast , Mennonite theologian

- Heinold Fast (1929–2015), German Mennonite theologian and Anabaptist researcher

- John Paul Lederach (* 1955), American Mennonite sociologist, peace researcher and professor of international peacebuilding

- Karl Friesen (* 1958), German-Canadian ice hockey goalkeeper

- David Neufeld (* 1970), German Mennonite publisher and founder of Neufeld Verlag

- Brendan Fehr (* 1977), Canadian actor

- James Reimer (* 1988), Canadian ice hockey goalkeeper

Coming from a Mennonite family:

- Jacob Ovens (1685 - around 1728), German dike builder and impostor

- Hugo Conwentz (1855–1922), German botanist, founder of European nature conservation

- Hermann Sudermann (1857–1928), German writer and playwright

- Willibrord Verkade (1868–1946), Dutch-German Benedictine monk and member of the Beuron art school

- Johan Huizinga (1872–1945), Dutch historian

- Johannes Reimer (* 1955), Russian-German theologian and professor of missiology

- David Bergen (born 1957), Canadian writer

- Jeff Hostetler (born 1961), American football player

- Lena Klassen (* 1971), Russian-German writer

- Ann Voskamp (* 1973), Canadian psychologist, farmer, family woman and bestselling author

- Floyd Landis (* 1975), American cyclist

literature

- Carsten Brandt: Language and usage of the Mennonites in Mexico. (= Series of publications by the Commission for East German Folklore in the German Society for Folklore, Vol. 61) Elwert, Marburg 1992, ISBN 3-7708-0995-5 .

- Lutherisches Kirchenamt (ed.): Report on the dialogue velkd / Mennonites 1989 to 1992 (texts from VELKD 53/1993) , Hanover: Lutherisches Kirchenamt 1993 (online at pkgodzik.de) .

- Fernando Enns (Hrsg.): Healing of memories - Liberated to the common future. Mennonites in dialogue. Reports and texts of ecumenical discussions on a national and international level. Otto Lembeck, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-87476-547-3 / Bonifatius, Paderborn 2008, ISBN 978-3-89710-393-1 .

- Diether G. Lichdi: The Mennonites in the past and present. From the Anabaptist movement to the worldwide free church. 2nd Edition. Weisenheim 2004, ISBN 3-88744-402-7 .

- Harry Loewen (ed.): Why I am Mennonite. Kümpers, Hamburg 1996, ISBN 3-930435-06-3 .

- Wilhelm Mannhardt: The freedom of defense of the old Prussian Mennonites. A historical discussion . Self-published by the Old Prussian Mennonite Congregations, Marienburg 1863. (Google eBook)

- Mennonite Lexicon .

- Alfred Neufeld: What we believe together. Anabaptist-Mennonite Beliefs. Neufeld Verlag , Schwarzenfeld 2008, ISBN 978-3-937896-68-7 .

- Phyllis Pellman Good, Merle Good: 20 Most Asked Questions about the Amish & Mennonites. Good Books, Intercourse / PA 1995, ISBN 1-56148-185-8 .

- Horst Penner , Horst Gerlach: Worldwide brotherhood. A Mennonite history book . 5th edition. Weierhof 1995.

- Walter Quiring, Helen Bartel: When their time was fulfilled. 150 years of probation in Russia. Modern Press, Saskatoon 1974.

- John Thiessen: Studies on the vocabulary of the Canadian Mennonites. (= German dialect geography, vol. 64) Elwert, Marburg 1963.

- Jan Christoph Wiechmann: What? Facebook? The Mennonites have their origin at Zwingli. They radically reject modern life. A community visit in Bolivia , Das Magazin , Tamedia , Zurich, December 13, 2014.

- JC Wenger: How the Mennonites came about . CMVB (Christliche Missions-Verlag-Buchhandlung), 3rd edition 2012, ISBN 978-3-86701-801-2

Web links

- Working group of Mennonite communities in Germany

- Working group of Mennonite Brethren in Germany

- Association of baptismal congregations

- Conference of the Mennonites of Switzerland

- Mennonite Free Church Austria

- Religious historical portal on the history of the Mennonites and other communities of the Anabaptist spectrum

- About German-speaking Mennonites in Paraguay

- Link catalog on the topic of Mennonites at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Collection of material about the Anabaptist movement and the rejection of the Lutheran confessional writings directed against it on the occasion of the Lutheran-Mennonite talks in Germany 1989–1992 compiled by OKR Peter Godzik (texts from VELKD No. 54/1993), Lutherisches Kirchenamt, Hannover 1993. (online on pkgodzik.de) (PDF; 314 kB)

Individual evidence

- ^ History of the Anabaptists / Mennonites. (No longer available online.) Mennonitischer Geschichtsverein e. V., archived from the original on June 24, 2011 ; Retrieved April 24, 2011 .

- ↑ Clarence Baumann: Nonviolence as a hallmark of the community . In: Hans-Jürgen Goertz (Ed.): The Mennonites . Evangelisches Verlagswerk, Stuttgart 1971, p. 129 .

- ↑ Horst Penner: Worldwide Brotherhood - Mennonite History Book. Weierhof 1984

- ^ History of the Anabaptists / Mennonites. (No longer available online.) Mennonitischer Geschichtsverein e. V., archived from the original on June 24, 2011 ; Retrieved April 24, 2011 .

- ↑ Jan Christoph Wiechmann: Life like in the 17th century - Mennonites in Bolivia - The terrible idyll. They don't know about the wars in the world or about the internet. In Bolivia the Mennonites live their godly life as in the 17th century. Whoever does not obey will be beaten. Stern, December 17, 2014

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Goertz: Mennonites. In: Mennonite Lexicon . Volume 5 (MennLex 5).

- ↑ Esther Loosse: Between leaving and exclusion. Exclusion and distancing from evangelical congregations of Russian-German emigrants . Kassel University Press, Kassel 2011, ISBN 978-3-86219-184-0 , pp. 57-59 .

- ↑ Hermann Heidebrecht: Do not be afraid, you little flock . Christlicher Missions-Verlag, Bielefeld 1999, ISBN 3-932308-14-X , p. 71 .

- ↑ On September 10, 1933, the Conference of East and West Prussian Mennonites wrote to Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler that they felt “with deep gratitude the tremendous elevation that God has given our people through your efforts, and that they, for their part, also offer joyful cooperation in the construction of our fatherland the forces of the Gospel, true to the motto of our fathers: No one can lay any other foundation than that which is laid, which is Jesus Christ ”. See Gerhard Rempel: Mennoniten und der Holocaust , pp. 87-133.

- ↑ James Irvin Lichti : Rhönbruderhof. In: Mennonite Lexicon . Volume 5 (MennLex 5).

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Goertz: Third Reich. In: Mennonite Lexicon . Volume 5 (MennLex 5).

- ↑ Diether Götz Lichdi: The Mennonites in the past and present. From the Anabaptist movement to the worldwide free church . Weisenheim 2004, ISBN 3-88744-402-7 , pp. 199 .

- ↑ Harold S. Bender, Diether Götz Lichdi, John Thiessen: Germany . In: Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online

- ↑ Imanuel Baumann: When the draft for a ban on Mennonites in the GDR was already drawn up . In: Hans-Jürgen Goertz and Marion Kobelt-Groch (eds.): Mennonite history sheets 2016 . Mennonite History Association, 2016, ISSN 0342-1171 , p. 61-79 .

- ^ Hubert Kirchner: Free churches and denominational minority churches . Evangelische Verlagsanstalt Berlin, (East) Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-374-00018-5 , p. 21-33 .

- ↑ Germany. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, accessed March 17, 2015 .

- ^ MWC World Directory 2015 Statistics. Mennonite World Conference, accessed April 24, 2016 .

- ^ Institute for the Study of Global Anabaptism. Goshen College: Institute for the Study of Global Anabaptism, accessed April 24, 2016 .

- ↑ As ecclesiastical Mennonites those established Mennonite congregations are described who did not join the reform movement of the Mennonite Brethren in the Ukraine after 1860. The expression refers to the fact that the established congregations mostly met in church buildings, whereas the newly formed Mennonite Brethren congregations mostly met in private houses or later in meeting houses. See: Cornelius Krahn and Walter W. Sawatsky: Kirchliche Mennoniten . In: Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online

- ↑ Germany. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, accessed March 17, 2015 .

- ↑ Working group of Mennonite communities: Mennonites in Germany ( Memento from April 28, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Germany (Mennonite communities and organizations). Mennonite Lexicon, accessed March 17, 2015 .

- ↑ 13 parishes with 2300 members

- ↑ This happens in contrast to the new Anabaptists , as Christians and congregations of the Evangelical Anabaptist congregations are also called.

- ^ MWC World Directory 2015 Statistics. Mennonite World Conference, accessed April 24, 2016 .

- ^ Mennonite, Brethren in Christ & Related Churches World Membership 2009

- ↑ Uruguayan Mennonite Congregation (in German and Spanish) ( Memento from December 10, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Jan Christoph Wiechmann: What? Facebook? The Mennonites have their origin at Zwingli. They radically reject modern life. A visit to the community in Bolivia ( Memento from July 6, 2015 in the Internet Archive ), Das Magazin , Tamedia , Zurich, December 13, 2014

- ^ Mennonites and Music. Third Way Café, accessed September 2, 2011 .

- ^ About MWC. Mennonite World Conference, archived from the original on September 27, 2011 ; Retrieved February 15, 2012 .

- ↑ The MERK in brief. (No longer available online.) Mennonite-European Regional Conference 2012, archived from the original on August 21, 2011 ; Retrieved September 12, 2011 .

- ^ The Lutheran-Mennonite Conversation in the Federal Republic of Germany 1989–1992. (PDF; 248 kB) online at pkgodzik.de, accessed on May 15, 2011 .

- ↑ Living as a Christian in Today's World: Adventists and Mennonites in Conversation 2011–2012. (PDF; 157 kB) Mennonite World Conference, accessed on October 27, 2013 .

- ^ Working group of Mennonite congregations: Dialog

- ^ LWF Council unanimously approves declaration asking forgiveness from Mennonites. Mennonews.de, accessed on February 12, 2010 .

- ↑ Healing of Memories - Reconciliation in Christ. (PDF; 2.5 MB) United Evangelical Lutheran Church of Germany (VELKD), accessed on September 6, 2012 .

- ^ Reconciliation after 500 years. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ), accessed on September 6, 2012 .

- ↑ One cannot make peace with such enemies. Welt Online, accessed September 6, 2012 .

- ↑ Fernando Enns: Healing of memories - Liberated to the common future. Mennonites in dialogue . Verlag Otto Lembeck, 2008, ISBN 978-3-87476-547-3 , p. 146 .

- ↑ Fernando Enns: Healing of memories - Liberated to the common future. Mennonites in dialogue . Verlag Otto Lembeck, 2008, ISBN 978-3-87476-547-3 , p. 173 .

- ↑ Olaf Radicke: rp-online: "Krefeld Protest Against Slavery". The Independent Friend, accessed February 12, 2010 .

- ↑ Introduction to Quakerism / Mennonite Contacts on Wikibooks