Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium

Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium ( Colonia Agrippina for short , also CCAA , German "Claudian colony and sacrificial site of the Agrippinese" , loosely translated "City of Roman law of the Agrippinese, founded under Emperor Claudius in 50 AD at the site of the altar for the imperial cult") the name of the Roman colony in the Rhineland from which today's city of Cologne developed. The CCAA was the capital of the Roman province Germania Inferior (Lower Germania ) and the headquarters of the Lower Germanic army. With the DiocletianAdministrative reform made it the capital of the Germania secunda province . Numerous evidence of the ancient city have survived to this day, including an inscription with the abbreviation CCAA on an arch of the Roman city gate, which is now in the Roman-Germanic Museum .

Historical background

(12 / 15-69 AD, Emperor 69), Sesterz

Oppidum Ubiorum , Ara Ubiorum and Apud Aram Ubiorum

The Ubii , a siedelnder in rechtsrheinischen German Field German tribe , were from the Roman general Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa during one of his governorships in Gaul (about 39/38 and about 20/19 BC.) On the left bank of the Cologne bay relocated to the Roman dominion . There they founded the Oppidum Ubiorum (civil settlement of the Ubier). For a long time it was believed that the area had been deserted after Gaius Iulius Caesar had wiped out the tribal association of the Eburones that had previously lived there in a campaign of revenge. Thomas Fischer and Marcus Trier point out, however, that according to more recent knowledge, the Eburones did not settle in the Cologne area, but further west, in the area of what is now Belgium and the Netherlands. Today it is predominantly assumed that the establishment of this Ubier settlement in the second governor period of Agrippa - i.e. around 19 BC. Chr. - is done. The Roman history of Cologne begins with this oppidum . The later Cologne was founded around 19 BC.

The Romans chose a flood-proof hill behind a Rhine island (or peninsula) that existed between the Rhine and the hill as a settlement site for the Ubier . On the eastern edge of this hill - after the oppidum had been elevated to the status of Roman Colonia - the eastern side of the Roman city wall was built. The location of this island, which has long since ceased to exist, roughly corresponds to the flood-prone part of Cologne's old town located between Heumarkt / Alter Markt and the Rhine. The arm of the Rhine, which gradually silted up from the middle of the 2nd century, was in the area of today's Alter Markt / Heumarkt; the hill west of the old market can still be seen today.

During the second governorship of Agrippa (around 20/19 BC) the expansion of the Roman road network in Gaul was undertaken. The Ubier oppidum was connected to the trunk road network by a road via Icorigium ( Jünkerath ), Beda vicus ( Bitburg ) and Augusta Treverorum ( Trier ) to Lugdunum ( Lyon ).

During the reign of Emperor Augustus (30/27 BC to 14 AD) the Ara Ubiorum ("Altar of the Ubier") was built in the urban area. This altar was possibly intended as the central sanctuary of the Greater Germanic province to be formed by the still-to-be-conquered Transrhenan Germania. The Cheruscan nobleman Segimundus , who comes from the family of Arminius , is attested in writing as a priest of the Ara for the year 9 AD . After the defeat of Publius Quinctilius Varus in the so-called " Battle in the Teutoburg Forest " in 9 AD and the recall of Germanicus in 16 AD, the large-scale plans to conquer the Germania on the right bank of the Rhine were abandoned. Nevertheless, the altar retained a certain significance, as the city appears on numerous inscriptions as Ara Ubiorum .

Between the years 9 and around 30 AD, the Cologne area was a garrison location . The Legio I Germanica (1st "Germanic" Legion) and the Legio XX Valeria Victrix (20th Valerian Legion, nicknamed "The Victorious") were stationed near the city . The place of the initial double legion camp was named Apud Aram Ubiorum ("At the Altar of the Ubier"). From 13 AD until his recall by Tiberius in 16 AD, the headquarters of Germanicus was located there in his endeavors to stabilize the Rhine border and to prepare and carry out new offensives against Germania on the right bank of the Rhine. At the death of Augustus (14 AD), the Cologne legions - who at that time were presumably staying at a summer camp in Novaesium together with the units stationed in Vetera - intended to proclaim Germanicus emperor. However, he behaved loyally to the heir to the throne Tiberius, prevented the planned imperial proclamation and appeased the mutinous soldiers with far-reaching concessions.

Around the year 30 the double legion camp was dissolved, the Legio I was relocated to Bonna , today's Bonn , the Legio XX to Novaesium , today's Neuss . From this point on, no more legions were stationed in Cologne. Cologne remained the headquarters of the Commander-in-Chief of the Lower Germanic Army (Exercitus Germaniae Inferioris) and his staff.

Rise to the Roman colony

Agrippina the Younger , daughter of Germanicus and wife of Emperor Claudius , who was born in 15 AD in the oppidum Ubiorum, later Cologne, succeeded in making Claudius the town of her birth Colonia Claudia in 50 AD Ara Agrippinensium ("city under Roman law on the site of an altar consecrated to the emperor, founded under Claudius on the initiative of Agrippina"). A colonia had far more extensive rights and privileges than an oppidum , namely Roman civil rights. With the elevation of the settlement to a Colonia, an enormous development of ancient Cologne and its further upswing began. The CCAA was thus at the top of the imperial city hierarchy, the citizens were on an equal footing with the Romans. The CCAA was in its heyday in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. AD one of the most important cities of the Roman Empire and for a long time its largest city north of the Alps. From the Roman name Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium, the names Coellen developed from the Middle Ages to the modern Cologne and from 1919 the current name Cologne (dialect: Kölle).

Also in Claudian times, the headquarters of Classis Germanica , the Roman Rhine fleet, was built not far from the CCAA . The fleet was on a hill south of the Roman city, in the Alteburg naval fort , in the area of today's Cologne-Marienburg district . This area was later called the Old Castle , after which the "Alteburger Wall" and the "Alteburger Platz" are named today. On the early Rhine island (or peninsula) in front of the fortified CCAA - between the Rhine and a tributary of the river and thus outside the city wall - there was a palaestra (sports facility) from the 1st to the middle of the 2nd century AD a water basin and from the middle of the 2nd century four three-aisled Horrea (warehouses) with a large courtyard. The settlement of this offshore island area did not take place until the medieval city expansion.

In 58 AD the city was struck by a fire of catastrophic proportions. Possibly this fire was the reason that from the middle of the first century onwards all fire-hazardous commercial operations (pottery, glassworks, blacksmiths) were banned from the core city and had to settle in the suburbs outside the fortifications.

By 70 AD (according to recent excavation results, probably around 90 AD), the city received a mighty city wall about 8 m high and 2.5 m wide. The rising masonry, which can still be partially seen in the cityscape today, comes from a building phase in the 3rd century. The area of the walled urban area was about one square kilometer (96 ha). On the arteries there were five large grave fields, the most important steles and grave goods of which can be seen in the Roman-Germanic Museum .

Year of the Four Emperors and the Batavian Uprising

With the death of Emperor Nero in 68 AD, the question of succession arose in Rome, which triggered a civil war in the empire . While in Rome Servius Sulpicius Galba, initially appointed by the Senate, was murdered by his rival Marcus Salvius Otho and the Praetorian Guard , the Rhenish legions in the CCAA proclaimed their Commander-in-Chief Aulus Vitellius as emperor; the troops in the British , Gallic, and Hispanic provinces sided with him. Vitellius marched with the majority of the Rhenish army to Italy and defeated the troops of Othos, who killed himself after the (first) battle of Bedriacum on April 14, 69 , after which Vitellius used the dagger, with which Otho is said to have killed himself, as sent a consecration gift for Mars to Colonia Agrippinensis.

There was a power vacuum at the Rhine border, which was bared by the troops. The Batavians rose in northeast Lower Germany . The CCAA, which at that time was still predominantly influenced by the Ubian population and not completely Romanized, joined them. But after the Batavians had demanded the demolition of the city walls, the CCAA switched back to the Roman side.

In the meantime the legions in the east of the empire (in the provinces of Aegyptus , Syria and Iudaea as well as on the Danube) had proclaimed Titus Flavius Vespasianus as emperor and decisively defeated the troops of Vitellius in the second battle of Bedriacum . After eight months of reign, Vitellius was overthrown, killed and thrown into the Tiber .

Capital of the Germania Inferior province

Under Domitian around 85/90 AD, the Lower Germanic army district was converted into the province of Germania Inferior , and the commander of the Lower Germanic army became governor of the province, the capital of which became the CCAA. The rapid growth of the city in terms of population and economic power gained even more dynamism as a result of this fact. The city quickly developed into a major economic center and a hub for trade with the Germanic territories beyond the borders of the empire. During the second and up to the middle of the third century, around 20,000 people lived in the city, around 15,000 of them inside and around 5,000 outside the city walls. The positive development of the CCAA was favored by almost two hundred years of political and military calm on the Rhine border, as well as by a number of extremely capable governors. This era only came to an end with the imperial crisis of the 3rd century .

The CCAA in the crisis of the 3rd century

Several new large Germanic associations threatened the northern borders of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century . Together with the threat from the aggressive New Persian Sāsānid Empire, the empire reached the limits of its military capabilities. Numerous usurpations and regional economic problems also weighed on. The political turmoil and economic recessions of this time also led the previously prosperous Rhenish metropolis to economic ruin.

The Imperium Galliarum , a Gallic sub-empire with Cologne as its center, existed between 260 and 274 AD. The troops of Postumus had provided a Frankish raiding party laden with loot on their way back near Cologne . The booty was divided among the soldiers. This led to a conflict with the legitimate lower emperor Saloninus , the son of Gallienus, and his Praetorian prefect Silvanus, who demanded the booty in favor of the state treasury. Thereupon Postumus had his mutinous men proclaim him Augustus and besieged Cologne, where Saloninus and his troops had fled. The city was conquered by Postumus and from then on served him as the seat of government of the Gallic part of the empire. The residence was relocated to Treveris (today's Trier ) around 271 . At the end of 273, the Roman emperor Aurelian began to recapture the west of the empire. Tetricus lost the decisive battle in March 274 near Châlons-sur-Marne. Tetricus and his son were evidently brought before Aurelian's triumphal procession in Rome in 274 (at least that is what the Historia Augusta reports ), but their lives were spared.

Late antiquity and end of Roman rule

It was not until the reign of Constantine I at the beginning of the fourth century that a certain recovery and stability seemed to have returned. In urban development, this phase is reflected in the construction of the Rhine bridge and the Divitia fort on the right bank of the Rhine . But the following phase of relative calm and stability only lasted until the middle of the century. In the autumn of 355 Cologne was besieged by the Franks , had to be surrendered in December of the same year and fell into the hands of the Teutons for ten months. The archaeological strata of the period indicate that conquest and pillage had disastrous effects and left the city in ruins. Construction work started again afterwards, but the forces and (mostly public) funds were probably only sufficient to restore what was absolutely necessary. The last news about a building measure dates back to the winter of 392/393, when Arbogast , the Magister militum of the western half of the empire, had an unspecified public building renewed in the name of Emperor Eugenius . Finally, in the fifth century, Roman culture died out and the city passed to the Ripuarians . Two rich burials in the cathedral area testify to this time.

Ancient topography and urban structure

The topography of the ancient CCAA differed from that of the inner city of Cologne today. The Roman city layout can, however, still be partially understood by the attentive observer in the cityscape. Hohe Straße (north-south), part of Schildergasse , Breite Straße , Brückenstraße, Glocken-, Sternengasse and Agrippastraße (east-west) lie above Roman roads, and many streets trace the course of the city wall.

Architectural monuments and archaeological findings

city wall

The city was protected by a city wall, the remains of which are still visible in some places. The inscription CCAA from the north gate of the cardo maximus right next to Cologne Cathedral (today in the Roman-Germanic Museum ) and the Roman tower from the 3rd century are noteworthy .

The erection of the city wall was the most extensive construction project that was ever carried out in the CCAA. It began with the elevation of the oppidum to colonia and should have been completed in less than a quarter of a century. The necessary logistical measures are an achievement in themselves. The required stones had to be brought in by water over a considerable distance, as there are no exploitable natural stone deposits in the vicinity of the city itself.

The wall was over 3.9 kilometers long and covered an area of approximately 97 hectares. It had been designed in a uniform concept, based on the topographical conditions of the site and essentially traced the contours of the flood-free plateau. Only on the east side of the colony did it descend deep into the Rheinaue. The city wall was reinforced with a total of 19 towers spaced between 77 and 158 m apart. Here, too, the eastern wall front was a special feature in that the towers were completely absent from it. Access to the interior of the city was made possible by nine city gates, each with an individual design. In front of the wall, on the three sides of the town, a ditch, which was up to 13 m wide and up to 3.30 m deep, served as an obstacle to the approach. However, it seems to have increasingly lost this function in the course of the 2nd century - as a result of the spreading development of the area outside the city wall.

The 19 towers - like the wall itself - were developed according to a uniform concept (so-called “Cologne normal type”). They rested on foundation slabs measuring 9.80 m by 9.80 m each. The rising masonry was 1.20 m to 1.30 m thick on the city side, on the field side its thickness was 2.40 m to 2.50 m. The highest proven tower height was a total of seven meters, of which 1.50 m on the Foundations were omitted.

A total of nine gates (one on the north side, three in the west, two in the south and three towards the Rhine on the east side) of different sizes and meanings were let into the city wall. The largest gates, each provided with three arches and associated gate structures, were located at the northern, western and southern ends of the Cardo Maximus and the Decumanus Maximus. Here these main axes of the inner-city road network merged into the trunk roads.

The entire fortification was built from mortared natural stone. Limestone and red sandstone were used for the representative gate systems, the rest of the stone material consisted of around 80% greywacke , 5% basalt and 3% trachyte . The remaining 12% was spread over various other rocks.

The relatively good state of preservation of the Roman city wall is primarily due to the fact that it did not fall victim to the stone robbery, which affected most Roman buildings, during the Migration Period and in the early Middle Ages. It was still used as a defensive wall and was the only protection of the medieval city of Cologne in the 11th century. Its course can still be traced very well in the modern cityscape due to the preserved fragments and the course of the streets. The city administration of Cologne has also installed metal markings at the most important points.

In today's cityscape, the course of the Roman city wall essentially corresponds to the following streets:

- From east to west: "Trankgasse" → "Komödienstraße" → "Zeughausstraße" (or "Burgmauer")

- From north to south: “St.-Apern-Straße” → “Gertrudenstraße” → “Neumarkt” → “Laachstraße” → “Clemensstraße” → “Mauritiussteinweg”

- From west to east: "Rothgerberbach" (or "Alte Mauer am Bach") → "Blaubach" → "Mühlenbach" → "Malzmühle"

Visible traces of the Roman city fortifications, following them from Cologne Cathedral in a westerly direction:

- Wall fragments in the treasury of Cologne Cathedral and in the cathedral's underground car park as well as an arch of the pedestrian gate of the Roman north gate directly at the cathedral.

- Opposite the St. Andreas Church, between "Komödienstraße" and "Burgmauer", the recessed, round staircase of a modern building is the shape of a tower on whose foundations it was built.

- The ruins of the “Lysolph Tower” and a piece of the wall are located on a traffic island at the intersection of “Komödienstraße” and “Tunisstraße”.

- "Römerbrunnen" between "Burgmauer" and "Zeughausstraße", opposite the rear front of the administrative court. The fountain was originally built exactly on the foundations of a tower, but was reconstructed slightly offset after bomb damage in World War II. The column with the Roman symbol of the she-wolf with the twins Romulus and Remus remained in its original place and marks the authentic location of the tower.

- In the area “Zeughausstrasse” / “Burgmauer”, wall fragments integrated into the facade of the armory, a little further to the west a free-standing wall section with a memorial plaque.

- So-called “Römerturm” on “Magnusstrasse”. Best preserved part of the Roman city fortifications with the ornamental decoration of a natural stone mosaic. Its good state of preservation is due to the fact that it was used as a latrine in a former Franciscan convent. The battlements were erected in 1897 and do not correspond to the Roman battlements that are about twice as wide. It is the north-western corner tower of the city fortifications, which at this point bends to the south.

- Ruins of the so-called "Helenenturm", at the intersection of "Helenenstrasse" and "St.-Apern-Strasse".

- Behind the choir of the Romanesque Church of St. Apostles , the course of the wall was made recognizable by a paving marker. In the facade of the church itself there is a walled gate through which one could enter the church from the city wall.

- Wall fragments integrated into the base of a residential building in “Clemensstrasse”.

- In the area of a residential complex between “Mauritiussteinweg” and “Thieboldsgasse” there is a section of the wall and the floor plan of a former tower, which is identified by a paving marker.

- Fragment of a tower at the Greek gate, corner of “Rothgerberbach”. These are the remains of the southwest corner tower of the Roman fortifications. At this tower, the course of the city wall bends to the east.

- Tower and wall fragments in the area “Alte Mauer am Bach” / “Kaygasse”. Built over by an office building, it is still cantilevered.

- Less well-preserved wall fragments in the “Mühlenbach” area.

- The former course of the eastern city wall is highlighted by pavement markings next to the church of Klein St. Martin .

- Further remnants of the only sparsely existing east wall can be found in the cellar vault of the Brungs wine house at Marsplatz 3-5.

The Roman city wall remained in use until the medieval city expansion and the construction of the new, more extensive wall in 1180 .

"Ubiermonument" or "Port Tower"

The so-called “Ubiermonument”, also referred to in the literature as the “Port Tower”, is located on the corner of Mühlenbach and An der Malzmühle. The monument, discovered in 1965/66, is the oldest dated Roman stone building in Germany. This structure is an almost square stone tower on a foundation plate of almost 115 m², the lower edge of which is about six meters below the level of the CCAA. A foundation plinth made of three layers of tuff blocks rises above the foundation plate . The rising tufa masonry is still 6.50 m high with up to nine layers of cuboids. In view of the mass of the structure, it was necessary to consolidate the subsoil in the Rheinaue. Oak stakes were driven into the ground for this purpose. The dendrochronological investigations showed that the trees were felled in AD 4. The archaeological findings also showed that the tower had already been destroyed at the time the city wall was built. It is clearly older than the CCAA and the oppidum Ubiorum . Its function is not clear. It could be part of the city fortifications of the oppidum and / or a watchtower controlling the Roman port.

The "Ubiermonument" has been preserved and can be visited.

Streets

Facsimile of the Tabula Peutingeriana from 1887/88

The city gates opened up the street system with the streets that are still important today . The grid of the Roman streets can still be seen in the street plan of today's Cologne. Today's " Hohe Straße " developed from the Cardo maximus and the Schildergasse from the decumanus maximus . Today's Aachener Straße essentially follows the Via Belgica , which as an extension of the decumanus maximus over a. Jülich, Heerlen and Maastricht to Amiens in France. Other arterial roads from Roman times are today's Severinstrasse and, in its further course, the Bonner Strasse, which led over the Roman Rheintalstrasse to Confluentes (Koblenz) and Mogontiacum (Mainz), then the Luxemburger Strasse, which crossed the Eifel via Zülpich (Tolbiacum) to Augusta Treverorum (Trier) led (today Agrippa-Straße Cologne-Trier ) and the street " Eigelstein " - " Neusser Straße " - "Niehler Straße". It is the the Rhine along leading highway (Rheintalstraße) about Neuss (Novaesium) to Xanten ( Colonia Ulpia Traiana ).

The level of these streets was well below today's. To this day, the Cardo maximus lies under the "Hohe Straße" at a depth of around 5.5 m. During sewer work in August 2004, the torso of a Venus figure was found in the rubble of the late Roman road .

Praetorium

The praetorium served as the residence and official seat as well as the administration building of the governor of the province Germania inferior . The governor combined in his person the military supreme command of the Lower Germanic army (Exercitus Germaniae Inferioris) and the civil supreme command of the province. Its civil power encompassed both the judiciary and the executive - and - within the regional framework - the legislative power . As Legatus Augusti pro praetore ("envoy of the emperor with the rank of praetor "), the governor of a province was always a former Roman consul . He was only directly subordinate to the emperor. In order to cope with his tasks, he had an extensive administrative apparatus as well as a cohort of infantry and an Ala cavalry directly subordinate to him.

The praetorium of the CCAA was located in the ancient city directly on the eastern city wall, northeast of the forum district. It is the only administrative building of its kind in the entire area of the former Imperium Romanum , where the name praetorium as such has been handed down in inscriptions. Essentially, four different construction phases could be differentiated for the building, which has seen repeated new constructions and extensions in the course of its history:

- The origins of the Praetorium may date back to AD 14. The first structure could be derived from the principia. of the Legio XX camp or from the praetorium. (in the sense of commander's apartment) of Germanicus , who stayed in Cologne between the years 13 and 17 AD. From this time two trachyte walls with a length of 148 and 173 m running parallel at a distance of 4.20 meters could be proven.The facade facing the Rhine was subdivided by pilasters . A little to the south of it, the apse, about eight meters in diameter, was excavated from a part of the building that cannot be identified.

- A second construction phase can possibly be assigned to the time after the events of AD 69/70 . To the north of the first building, the so-called Konchenbau was built with its outbuildings. The long parallel walls of the oldest building were divided into numerous smaller rooms by installing partition walls. Other parts of the building - some with hypocausts - were added to the area between the praetorium and the city wall. Including the so-called “house on the city wall”, which was connected to the main complex of the praetorium via a pillar hall.

- The first phase of the third construction phase includes the scheduled demolition and reconstruction of large parts of the administration palace. The large-scale renovations were probably carried out under the governorship of the later "auction emperor" Didius Julianus , who, after his consulate in 175, resided in Cologne as governor of Lower Germany from around 180. A building inscription by Commodus , in which Didius Julianus is mentioned, allows the date of the renovation to be dated almost exactly to the years 184/185. Only the “house on the city wall” and the pillar hall belonging to it have been preserved from the older development. A large gallery building was created, to which various smaller components were attached in the north. In the south, the apse building from construction phase I was replaced by a large hall structure, the so-called Aula Regia or Palastaula , the apse of which was approximately 15 m in diameter. In total, the praetorium in this construction phase extended over the area of a total of four insulae and should therefore have taken up almost 40,000 m².

At an unexplained point in time, the praetorium was destroyed by a devastating fire. The discovery of a coin of Constantine , which was in the rubble and was minted between 309 and 313, indicates that the first section of the third construction phase could have lasted for 125 years. After that, destruction and reconstruction took place in the second decade of the fourth century at the earliest. A written testimony about the Praetorium is only available again for the year 355 by Ammianus Marcellinus . When Cologne was conquered by the Franks in that year, the Praetorium was also affected and possibly completely destroyed.

- The time of the reconstruction and thus the fourth and final construction phase of the Praetorium cannot be precisely defined. It may have started immediately after the liberation of Cologne from the Franks by Emperor Julian in 356. After an interruption, construction continued in the last quarter of the fourth century and finally completed in the last decade of the century. Of the older parts of the building, only the southern areas of the gallery building and the Aula Regia have been preserved. The new main building initially consisted of a large rectangular hall with the so-called Porticus Gallery in front of it on the Rhine front. At the northern and southern ends of the central building, two apsidic halls were built with ten-meter-wide arches facing west. In a later phase of the expansion, an octagonal building with a circular interior with a diameter of 11.30 m was installed in the center of the main building . The octagonal structure divided the central building into two halls of around 250 m² each.

When the new town hall was built in 1953, the praetorium area was largely excavated and archaeologically examined. The stone remains of the various construction phases have been preserved and can be viewed under the so-called “Spanish building” of the town hall.

Forum

As in every major Roman city, the center of the CCAA was the forum district at the intersection of Cardo and Decumanus maximus . The entire forum area of ancient Cologne probably comprised six insulae ("blocks of flats"). In the area of the two western insulae , the square was closed off by a large ring cryptoporticus , an underground hall system, the outer diameter of which was around 135 m. The city's sanctuary, the Ara Ubiorum , is believed to be in this underground structure . About the cryptoporticus, on the antique overflow level, probably rose a portico , one for the actual space conditioning - the Forum - open towards portico appropriate size. The forum itself probably took up the space of four insulae , two of which were to the west and two east of the Cardo Maximus .

In today's cityscape of Cologne nothing can be seen of the ancient relics of this district above ground. Even the modern streets do not match those that demarcated the forum district in ancient Cologne. The approximate area should be looked for at the intersection of “Hohe Straße” and “Gürzenichstraße” and then further east towards “Schildergasse”. In the basement of the “Schildergasse” department store at the corner of “Herzogstrasse”, a block of the forum wall was preserved and made accessible to the public.

amphitheater

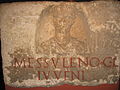

Even if the direct archaeological evidence on the basis of the corresponding building findings is still pending, the existence of at least one amphitheater in the CCAA can be assumed to be certain. Individual finds from the cityscape epigraphically prove the existence of, for example, a vivarium or the capture of 50 bears, which were presumably used to hunt animals. These inscriptions are also related to dedications to the Diana Nemesis , who was considered the patron goddess of gladiators. The picture is rounded off by the finds of two inscription stones from Deutz and from the southern burial ground, which were made in the 1950s. The first stone is a consecration stone for the Diana Nemesis , the second the gravestone of a "doctor" (trainer) of the gladiators. The inscription reads:

- D (is) M (anibus)

- Ger (manio?) Victo-

- ri doct (ori) gl (adiatorum)

- [–––] pater

- [et] Cl [–––] lu [-]

- coniu {u} x

It is therefore a gravestone dedicated to the gods of the dead (Dis Manibus) of a "doctor" (instructor) of the gladiators with the name Germanius Victor.

Also noteworthy in this context is the discovery of a tombstone for two gladiators, which can be dated to the first half of the first century AD. The lower part of the front of the stone shows two gladiators in a fighting stance and with typical clothing and equipment.

The mapping of all individual finds that are directly related to the theater plays (including relevant pictorial representations in mosaics or on tableware) suggests an amphitheater most likely in the northern outskirts of the CCAA.

- Gladiator motifs on finds from the Roman-Germanic Museum, Cologne

Temples and early Christian churches

Following the urban Roman model, there was also a capitol temple in CCAA, which was dedicated to the gods Jupiter , Juno and Minerva , in the place of which the church of St. Mary in the Capitol was built in the 11th century . This is located in the southern old town at "Marienplatz".

A Mars stamp has also come down to us. The street names "Marspfortengasse", "Obenmarspforten" and "Marsplatz" still indicate its former location. In front of the actual entrance to the Temple of Mars there was an archway, the Porta Martis. This had to be crossed to reach the temple. Hence the name "Marspfortengasse". The temple itself is likely to have stood at the position of today's Wallraf-Richartz Museum . According to tradition, a sword Gaius Julius Caesar is said to have been kept in this temple, which Gaius Julius Caesar is said to have left behind after his battle against the Eburones .

Of the late antique buildings, a central building of unknown use in front of the northwest corner of the city wall should be mentioned, whose polygonal core with a total of eight horseshoe-shaped apses was later reshaped by today's St. Gereon church . The partially exposed Roman substance, which is still up to 16.50 meters high, makes this monument one of the best-preserved Roman buildings in Cologne in its original location.

The existence of an early Christian cult area in Cologne is passed down by Ammianus Marcellinus for the year 355. It is not known where this cult room was located. As a bishopric - the first bishop known by name was Maternus - a church must have already existed in Cologne beforehand. Church buildings in the area of the cathedral can be traced back to the early Middle Ages at the latest, but the continuity of a bishop's church at this point since late antiquity cannot be ruled out.

Residential buildings

Due to the ongoing redevelopment of the city, little is known of the ancient housing developments. Nevertheless, over 36 residential buildings with mosaic floors have now been located. Large parts of two insulae were excavated south of the cathedral. The so-called peristyle house with the Dionysus mosaic, whose mosaic was integrated into the Roman-Germanic Museum , stood here on the Rhine front . It had a large peristyle with the living quarters around it. Some of the rooms had mosaic floors. There were a number of shops on the Rhine side. A second house in this insula is not quite as clearly preserved in the plan, but it had an atrium. There was also a mithraium in another house . The Insula had arcades facing the street. The second insula was west of the first. Here, too, a dense residential development could be ascertained, but the character of individual houses remains blurred due to constant renovations. Particularly noteworthy are the remains of a well-preserved candelabra wall from the first century AD (see: wall painting from Insula H / 1, room 1434 ). A house in the west of the city on Gertrudenstrasse was also relatively well preserved, and it also had well-preserved wall paintings. Here, too, a peristyle was found with the living rooms around it.

Hydraulic engineering

Water supply

From the 1st to the 3rd century, the city on the Rhine was supplied with fresh drinking water by the Eifel water pipeline . At around 95 kilometers in length, it was one of the longest aqueducts in the Roman Empire and the longest known to be north of the Alps. It is only archaeologically documented, just like the predecessor pipelines built from around 30 AD, the foothills pipeline with its individual branches (→ Roman water pipelines in Hürth ). There were also thermal baths (in the area of St. Peter / Museum Schnütgen ).

Water disposal

There were underground pipes in Cologne for sewage disposal. The wastewater was disposed of untreated in the Rhine. A longer section of the sewer pipes has been made accessible and is accessible from the Praetorium.

Thermal baths

- See also the separate article Roman thermal baths and medieval bathhouses in Cologne .

The Cologne thermal baths were proven in the early 1950s by excavations of the Roman-Germanic Museum around St. Cäcilien . However, more precise observations could only be made in 2007 during the construction work for the Cäcilium office complex on the corner of Cäcilien- and Leonard-Tietz-Strasse. Foundations of a circular building with an outside width of 18 meters and made of opus caementitium were found that were 1.20 meters wide and up to 1.70 meters high . Century and were used until the 4th century. The facility is about the size of an imperial bathing complex in Baiae . The remains of the hypocaust can still be seen on two sides. The finds are not cleared away, but remain covered under a 400 m² floor slab. The client waives the areas that are to be used accordingly. The areas of the thermal baths facing the north-south route were "deeply destroyed" during the road construction.

Rhine bridge

The first permanent bridge over the Rhine was probably built in 310 under Constantine I. The Roman bridge connected the “Divitia” fort on the right bank of the Rhine (in today's Deutz district ), which housed up to 1,000 soldiers, with the CCAA. The bridge spanned the river over a length of around 420 meters. A total of fifteen previously verified bridge piers carried the approximately ten meter wide pavement at uneven intervals. The bridge was possibly still in use in the high Middle Ages. Their end is not certain for sure. According to tradition, archbishop Bruno I (953-965) had it demolished as a preventive measure against night raids on medieval Cologne . It then took until 1822 before the city was again connected to Deutz by a bridge.

"Divitia" bridgehead fort

The Divitia bridgehead fort was located on the right bank of the Rhine, in the area of today's Cologne district of Deutz. The founding inscription of the fort was discovered in 1128 during demolition work on the fort grounds. According to her, the military camp was built under Constantine I by the Legio XXII (22nd Legion) around the year 310. It was intended to strengthen the Rhine border against the Germanic tribes, which in late antiquity were more and more common on the left bank of the Rhine. The tradition of the founding inscription has been confirmed by archaeological finds (Constantinian coins and brick stamps of the Legio XXII), and the walls of the fort have been proven by excavations in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Deutz fort is a square stone fort which, with a side length of 142.35 m, took up an area of around two hectares. It was surrounded by a 3.30 m thick wall, which was reinforced with fourteen protruding round towers. In addition, the two camps gates were flanked by two semicircular towers, the gates themselves were with portcullises reinforced. With its west side the fort bordered directly on the Rhine. The three sides of the land had a twelve-meter-wide and three-meter-deep pointed ditch as an obstacle to the approach, which was about 30 meters in front of the fort walls. Another, roughly equally wide ditch between the outer ditch and the fort has meanwhile been interpreted as Carolingian in research , but probably also belongs to the founding phase of the camp.

The fort was cut through by a main camp road that was only 5.10 m wide in a west-east direction. This road connected the two only gates of the fortification and led on the west side of the camp directly behind the west gate of the fort to the Rhine bridge to the CCAA. To the north and south of Lagerstraße there were eight barracks each, with their narrow sides facing the street, which offered space for a crew of up to 1,000 men. The four buildings in the center of the camp differed from the other buildings by their porticos facing the main street of the camp and must have served as staff and administration buildings as well as officers and non-commissioned officers' apartments. The remaining twelve barracks are believed to have housed just as many Centuries . Due to the lack of adequate horizons of destruction, it can be assumed that the fort was not affected during the Franks incursions in the second half of the 4th century. It was probably cleared according to plan at the beginning of the 5th century. It then served as the Franconian royal castle.

In today's cityscape, some traces of the former fortification are still visible:

- the foundations of the east gate were preserved and made accessible in a small green area below the Lufthansa building

- Parts of the wall course of the camp center were marked west, north and south of the church "Alt St. Herbert" by a dark paving in today's walking horizon

- The contours of the central defense tower of the north wall on Urbanstrasse are also highlighted by separate paving

- A piece of the south wall is in the underground car park of the Lufthansa building, which is not open to the public

The surrounding area

Burial grounds

As in the entire Roman Empire, there were no burial places within the residential areas in the CCAA. The Twelve Tables law from the 5th century BC already forbade burying or burning the dead within the city ( "Hominem mortuum in urbe ne sepelito neve urito." Plate X). This requirement was observed in all Roman settlements over the centuries. Instead, the villages were surrounded by extensive cemetery grounds along their arterial roads. The CCAA also enclosed a ring of cemeteries. In the literature, a distinction is made between five different burial grounds. The earliest burials kept a distance of up to several hundred meters from the city wall. In the urban area around Cologne there are also known grave fields which, due to their location and size, belonged to villas close to the city.

Urban burial grounds

The largest extent of the grave fields was determined on the Limes road leading to Bonna with a length of three kilometers. In today's cityscape, this so-called southern burial ground corresponds to the Severinsviertel resp. the Severinstraße and the Bonner Straße . Its occupancy ranges from the early first century to the Franconian period. Almost all forms of burial are represented. Cremation graves in urns, earth pits and stone boxes prevailed until the 3rd century AD. In the course of the 3rd century, body burials replaced the cremation burial site. Body burials are laid out in wooden coffins, stone sarcophagi and lead coffins, sometimes no remains of a coffin are found. Isolated grave chambers have also been located. Among the more remarkable individual graves are the monumental tomb of Lucius Poblicius , a veteran of the Legio V Alaudae from the 1940s of the first century AD, and the grave stele of the slave trader Caius Aiacius, also from the early first century .

The burial ground of Luxemburger Strasse took up a similarly large area with a length of around 2.5 km and a width of up to 400 m. Today's “Luxemburger Straße” largely corresponds to the course of the Roman state road from the CCAA to the Augusta Treverorum . Only a few larger grave monuments were found in this grave field, otherwise all common grave types with some complex designs and lavish additions could be identified. A special feature is the archaeological evidence of central cremation sites , so-called Ustrinae .

The Aachener Straße cemetery also covered an area of more than two kilometers . Today's "Aachener Straße" corresponds in its course to that of the Roman state road that connected Cologne to the Channel coast via Iuliacum , Tongern and Bavay . Here, too, the monumental tombs are relatively rare, but two of the most spectacular individual Roman finds in Cologne's urban area come from this necropolis , with two slide-in cups .

The axis of the north-western burial ground formed a side street that could not be clearly identified and left the ancient city in a north-westerly direction. While the other CCAA burial grounds left a certain distance to the city wall, at least in the early days of their occupancy, the north-western burial ground was immediately adjacent to the city wall at the beginning of its occupancy. Around 1,200 burials are known, of which around 800 are cremation graves and 400 body graves. What is remarkable is the occupation time of the necropolis, the use of which began in the early Roman oppidum period and lasted well beyond the end of Roman rule into the 9th century. Numerous gravestones could be recovered from the area of the burial ground. The stele of the late antique officer Victorinus , who was slain by a Franconian near Divitia in the 4th century, is striking .

The Neusser Straße cemetery, located in the far north of ancient Cologne, was oriented - like the “southern burial ground” - on the course of the Limesstraße, here in the direction of Novaesium . The occupation of the burial ground began - with a few isolated exceptions - essentially only in the second half of the first century AD with the burial of military personnel. Monumental grave structures were only found sporadically. Smaller burial forms of all variations dominated the northern necropolis. Various job titles on the recovered grave steles give an impression of the economic life of the ancient city, the wide range of small finds reflects the wide range of religions practiced.

- Finds from the burial grounds of the Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium

Tomb of Poblicius

- See main article Tomb of Poblicius .

Burial chamber of Cologne-Weiden

- See main article Roman grave Cologne-Weiden .

Villae Rusticae

Within today's area of the city of Cologne, which should not be confused with the ancient administrative area of the CCAA, several Roman villas were excavated. The extensive uncovered estate of Cologne-Müngersdorf was published in a monograph by Fritz Fremersdorf as early as 1933 . The slide cup on display in the Roman-Germanic Museum in Cologne comes from the burial ground of a Roman villa in Cologne-Braunsfeld . Remains of other villas were found under the St. Pantaleon Church in Cologne as well as in Cologne-Niehl, Cologne-Rodenkirchen, Cologne-Rondorf, Cologne-Vogelsang and Cologne-Widdersdorf.

Monument protection and museum preparation

The material relics of the CCAA are ground monuments according to the law for the protection and care of monuments in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia (Monument Protection Act - DSchG) . Research and targeted collection of finds are subject to approval. Accidental finds are to be reported to the monument authorities.

Particularly meaningful archaeological finds from the Cologne city area are shown in the Roman-Germanic Museum Cologne (see main article).

Trivia

The asteroid (243440) Colonia was named after the colony.

literature

Monographs and edited works

- Wolfgang Binsfeld : From the Roman Cologne . Greven, Cologne 1966. (Series of publications by the Cologne Archaeological Society, 15).

- Werner Eck : Cologne in Roman times. History of a city under the Roman Empire. (Volume 1 of the history of the city of Cologne in 13 volumes ). Greven, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-7743-0357-6 .

- Thomas Fischer and Marcus Trier : The Roman Cologne . Bachem, Cologne 2014, ISBN 978-3-7616-2469-2 .

- Fritz Fremersdorf : The Roman grave in Weiden near Cologne. Reykers, Cologne 1957.

- Ulrich Friedhoff: The Roman cemetery on Jakobstrasse in Cologne. Zabern, Mainz 1991, (Kölner Forschungen, 8), ISBN 3-8053-1144-3 .

- Brigitte and Hartmut Galsterer : The Roman stone inscriptions from Cologne. RGM, Cologne 1975.

- Rudolf Haensch : Capita provinciarum. Governor's seat and provincial administration in the Roman Empire: Zabern, Mainz 1997, (Kölner Forschungen, 3), ISBN 3-8053-1803-0 .

- Constanze Höpken: The Roman ceramic production in Cologne. Zabern, Mainz 2005, ISBN 3-8053-3362-5 .

- Alexander Hess and Henriette Meynen (eds.): The Cologne city fortifications. Unique evidence from Roman, Middle Ages and modern times (= Fortis Colonia series of publications, Volume 3). Regionalia, Daun 2021, ISBN 978-3-95540-370-6 .

- Heinz Günter Horn : Mystery symbolism on the Cologne Dionysus mosaic. Rheinland-Verlag, Bonn 1972.

- Bernhard Irmler: Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium: Architecture and urban development. 3 vols. Munich, Technical University, dissertation 2005.

- Peter LaBaume: Colonia Agrippinensis. 2nd, improved and enlarged edition. Greven, Cologne 1960.

- Andreas Linfert et al .: Roman wall painting of the north-western provinces. RGM, Cologne 1975.

- Inge Linfert-Reich: Roman everyday life in Cologne. 2nd Edition. RGM, Cologne 1976.

- Bernd Päffgen : The excavations in St. Severin in Cologne. 3 volumes. Zabern, Mainz 1997, (Kölner Forschungen, 5), ISBN 3-8053-1251-2 .

- Gundolf Precht : Building history study of the Roman praetorium in Cologne. Rheinland Verlag, Cologne 1973, (Rheinische Ausgrabungen, 14), ISBN 3-7927-0181-2 .

- Gundolf Precht: The tomb of Lucius Poblicius. Reconstruction and construction. RGM, Cologne 1975.

- Gundolf Precht: The Roman fort and the former Benedictine monastery church of St. Heribert in Cologne-Deutz. OV, Cologne 1988.

- Matthias Riedel: Cologne, a Roman economic center. Greven, Cologne 1982, ISBN 3-7743-0196-4 .

- Hermann Schmitz: Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium. Verlag Der Löwe, Cologne 1956, (publications by the Cologne History Association, 18)

- Helmut Schoppa : Roman gods monuments in Cologne. Reykers, Cologne 1959.

- Uwe Süßenbach: The city wall of Roman Cologne. Greven, Cologne 1981, ISBN 3-7743-0187-5 .

- Renate Thomas: Roman wall painting in Cologne. Zabern, Mainz 1993, (Kölner Forschungen, 6), ISBN 3-8053-1351-9 .

- Dela von Boeselager : Graves with glass finds on Luxemburger Strasse. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-7861-2528-0 .

- Gerta Wolff: The Roman-Germanic Cologne. Guide to the museum and city. 6th revised edition. Bachem, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-7616-1370-9 .

Essays (selection)

- Heike Gregarek: Rediviva. Stone recycling in ancient Cologne. In: Heinz-Günter Horn et al. (Ed.): From the beginning. Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. Zabern, Mainz 2005, (Writings on the preservation of soil monuments in North Rhine-Westphalia, 8), ISBN 3-8053-3467-2 , pp. 139-145.

- Klaus Grewe : De aquis Coloniae. Water for the Roman Cologne. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. History in the heart of Europe. Zabern, Mainz 1990, ISBN 3-8053-1138-9 , pp. 196-201.

- Hansgerd Hellenkemper : Archeology in Cologne. In: Heinz-Günter Horn et al. (Ed.): From the beginning. Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. Zabern, Mainz 2005. (Writings on the preservation of soil monuments in North Rhine-Westphalia, 8), ISBN 3-8053-3467-2 , pp. 63–73.

- Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Archeology in Cologne. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): A country makes history . Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. Zabern, Mainz 1995, ISBN 3-8053-1793-X , pp. 79-90.

- Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Archeology and soil monument preservation in Cologne. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. History in the heart of Europe. Zabern, Mainz 1990, ISBN 3-8053-1138-9 , pp. 68-74.

- Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Archaeological research in Cologne since 1980. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Hrsg.): Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. History in the heart of Europe. Zabern, Mainz 1990, ISBN 3-8053-1138-9 , pp. 75-88.

- Hansgerd Hellenkemper, Dela von Boeselager, Klaus Grewe and others: Cologne. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): The Romans in North Rhine-Westphalia . Licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , pp. 459-521.

- Maximilian Ihm : Agrippinenses . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume I, 1, Stuttgart 1893, Col. 900 f.

- Sabine Leih: Under a craftsman's house. A Roman cellar on Insula 39. In: Heinz-Günter Horn et al. (Ed.): From the beginning. Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. Zabern, Mainz 2005, (Writings on the preservation of soil monuments in North Rhine-Westphalia, 8), ISBN 3-8053-3467-2 , pp. 415-416.

- Frederike Naumann-Steckner: Aphrodite from the high street in Cologne. In: Heinz-Günter Horn et al. (Ed.): From the beginning. Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. Zabern, Mainz 2005, (Writings on the preservation of soil monuments in North Rhine-Westphalia, 8), ISBN 3-8053-3467-2 , pp. 400–403.

- Friederike Naumann-Steckner , with contributions by Berthold Bell, Jürgen Hammerstaedt , Susanne Rühling, Anthony Spiri, Olga Sutkowsks and Marcus Trier : Lyra, Tibiae, Cymbala ... Music in the Roman Cologne (exhibition catalog Römisch-Germanisches Museum July 19 to November 3, 2013 , Small writings of the Roman-Germanic Museum of the City of Cologne) , LUTHE Druck und Medienservice, Cologne 2013, ISBN 978-3-922727-83-5 .

- Stefan Neu: Roman graves in Cologne. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): A country makes history. Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. Zabern, Mainz 1995, ISBN 3-8053-1793-X , pp. 265-268.

- Stefan Neu: The discovery of Achilles - in Cologne. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): A country makes history. Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. Zabern, Mainz 1995, ISBN 3-8053-1793-X , pp. 269-273.

- Stefan Neu: Roman reliefs on the banks of the Rhine in Cologne. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. History in the heart of Europe. Zabern, Mainz 1990, ISBN 3-8053-1138-9 , pp. 202-208.

- Alfred Schäfer and Marcus Trier: A port gate in Roman Cologne . In: Der Limes 2, 2012 / Issue 2. News sheet of the German Limes Commission. Pp. 20-23. ( online pdf )

- Burghart Schmidt: The timber for the Roman ports in Xanten and Cologne. An interpretation of the dendrochronological dating. In: Heinz-Günter Horn et al. (Ed.): From the beginning. Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. Zabern, Mainz 2005, (Writings on the preservation of soil monuments in North Rhine-Westphalia, 8), ISBN 3-8053-3467-2 , pp. 201-207.

- Renate Thomas : Roman wall painting finds from the excavations on the Breite Strasse in Cologne. In: Heinz-Günter Horn et al. (Ed.): From the beginning. Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. Zabern, Mainz 2005, (Writings on the preservation of soil monuments in North Rhine-Westphalia, 8), ISBN 3-8053-3467-2 , pp. 395–398.

- Renate Thomas: The Roman bronze horse from the villa suburbana on Barbarossaplatz in Cologne. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): A country makes history. Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. Zabern, Mainz 1995, ISBN 3-8053-1793-X , pp. 274-275.

- Renate Thomas: Roman wall painting in Cologne. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. History in the heart of Europe. Zabern, Mainz 1990, ISBN 3-8053-1138-9 , pp. 209-215.

- Marcus Trier: Archeology in Cologne canals. In the footsteps of Rudolf Schultze and Carl Steuerungagel. In: Heinz-Günter Horn et al. (Ed.): From the beginning. Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. Zabern, Mainz 2005, (Writings on the preservation of soil monuments in North Rhine-Westphalia, 8), ISBN 3-8053-3467-2 , pp. 161–168.

Essays (selection of the most important series)

Research results on the archeology and history of Roman Cologne were and are regularly represented in the following series of publications:

- Archeology in the Rhineland, previously excavations in the Rhineland . Annual reports of the Rhineland Regional Association / Rhenish Office for Land Monument Preservation. Theiss, Stuttgart.

- Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission . Since 1904. Zabern, Mainz.

- Bonn yearbooks . Since 1842. Habelt, Bonn.

- Germania . Bulletin of the Roman-Germanic Commission of the German Archaeological Institute. Since 1917. Zabern, Mainz.

- Yearbook of the Cologne History Association. Since 1912. SH, Cologne.

- Cologne yearbook for prehistory and early history. Published by the Roman-Germanic Museum and the Cologne Archaeological Society. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1955–1992.

Web links

- Oliver Meißner: A brief history of the city of Cologne on the commercial pages of cologneweb.com, accessed on January 13, 2013

- Roman Cologne and monuments of Roman Cologne on the private website of Günter Lehnen, accessed on January 13, 2013

- Jona Lendering: Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium (Cologne) . In: Livius.org (English), accessed on January 13, 2013

- Official website of the Roman-Germanic Museum , accessed on January 13, 2013

- colonia3d - Animated 3D model of the CCAA, website of the Cologne International School of Design and the Ministry for Schools, Science and Research of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia, accessed on January 13, 2013

- Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium, Cologne in the archaeological database Arachne of the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), accessed on January 13, 2013

Remarks

- ↑ Coordinates 50 ° 56 '29.1 " N , 6 ° 57' 23.8" E

- ↑ Coordinates 50 ° 56 ′ 29.1 ″ N , 6 ° 57 ′ 17 ″ E

- ↑ Coordinates 50 ° 56 '28.9 " N , 6 ° 57' 11.5" E

- ↑ Coordinates 50 ° 56 '28.7 " N , 6 ° 57' 4.4" E

- ↑ Coordinates 50 ° 56 '28.6 " N , 6 ° 57' 4.7" E

- ↑ Approximately at 50 ° 56 ′ 28.5 ″ N , 6 ° 57 ′ 2 ″ E

- ↑ Approximately at 50 ° 56 '27.8 " N , 6 ° 55' 30" E

- ↑ Coordinates 50 ° 56 '27.3 " N , 6 ° 56' 48" E

- ↑ Approximately at 50 ° 56 '23.7 " N , 6 ° 56' 46.7" E

- ↑ Approximately at 50 ° 56 '11.5 " N , 6 ° 56" 44.2 " E

- ↑ Approximately at 50 ° 55 '49.5 " N , 6 ° 56" 52 " E

- ↑ Approximately at 50 ° 55 '51.5 " N , 6 ° 57' 4.5" E

- ↑ Approximately at 50 ° 56 ′ 8 ″ N , 6 ° 57 ′ 33 ″ E

Individual evidence

- ↑ Johannes Heinrichs : Civitas Ubiorum. Studies on the history of the Ubier and their area. Habilitation thesis Cologne 1996.

- ↑ Caesar: De Bello Gallico. 6, 29-44 .

- ^ Thomas Fischer and Marcus Trier: The Roman Cologne. Bachem, Cologne 2014, ISBN 978-3-7616-2469-2 , p. 41. In addition, the tribe of the Eburones has not been completely exterminated, but "only" has been greatly reduced.

- ↑ Werner Eck : Caesar, the Eburonen and the Civitas of the Ubier. In: Ders .: Cologne in Roman times. History of a city under the Roman Empire. (Volume 1 of the history of the city of Cologne in 13 volumes ). Greven, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-7743-0357-6 , pp. 31-45.

- ↑ Werner Eck: Agrippa and the Ubier as an alliance partner of Rome. In: Ders .: Cologne in Roman times. History of a city under the Roman Empire. (Volume 1 of the history of the city of Cologne in 13 volumes ). Greven, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-7743-0357-6 , pp. 46-62.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. I, 57.2.

- ↑ Martin Kemkes : The Limes. Rome's border with the barbarians. Thorbecke, 2nd, revised edition. Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2006, ISBN 3-7995-3401-6 , p. 46.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. I, 39.1.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. I, 31.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales. I, 34-37.

- ↑ Werner Eck: The Augustan policy of Germania and the beginning of Roman Cologne. In: Ders .: Cologne in Roman times. History of a city under the Roman Empire. (Volume 1 of the history of the city of Cologne in 13 volumes ). Greven, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-7743-0357-6 , pp. 63-126.

- ^ A b c Jürgen Kunow: The military history of Lower Germany. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): The Romans in North Rhine-Westphalia . Licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , pp. 27-109.

- ^ Tacitus: Annales XII, 27.

- ^ Tacitus, Annales XIII, 57

- ↑ Werner Eck: The foundation of the Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium. In: Ders .: Cologne in Roman times. History of a city under the Roman Empire. (Volume 1 of the history of the city of Cologne in 13 volumes ). Greven, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-7743-0357-6 , pp. 127-177.

- ^ A b c Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Cologne. Story. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): The Romans in North Rhine-Westphalia . Licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , pp. 459–473.

- ^ Suetonius: Vitellius. 7.8.

- ^ Suetonius, Vitellius

- ^ Tacitus: Historiae. IV, 44-68.

- ↑ Werner Eck: The CCAA in the crisis years 68-70. In: Ders .: Cologne in Roman times. History of a city under the Roman Empire. (Volume 1 of the history of the city of Cologne in 13 volumes ). Greven, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-7743-0357-6 , pp. 178-210.

- ↑ Werner Eck: The CCAA as the provincial capital and the representatives of state power. In: Ders .: Cologne in Roman times. History of a city under the Roman Empire. (Volume 1 of the history of the city of Cologne in 13 volumes ). Greven, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-7743-0357-6 , pp. 242-272.

- ↑ Werner Eck: A city blooms. The CCAA from the Flavians to Trajan (70–98). In: Ders .: Cologne in Roman times. History of a city under the Roman Empire. (Volume 1 of the history of the city of Cologne in 13 volumes ). Greven, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-7743-0357-6 , pp. 211–241.

- ↑ Werner Eck: Internal security is falling apart. The outbreak of the crisis (222–260). In: Ders .: Cologne in Roman times. History of a city under the Roman Empire. (Volume 1 of the history of the city of Cologne in 13 volumes ). Greven, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-7743-0357-6 , pp. 547-564.

- ↑ Werner Eck: A Gallic sub-empire with Cologne as its center (260-274). In: Ders .: Cologne in Roman times. History of a city under the Roman Empire. (Volume 1 of the history of the city of Cologne in 13 volumes ). Greven, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-7743-0357-6 , pp. 565-585.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus 15.8.

- ↑ CIL 13, 08262 : [Salvis domini] s et Imperatoribus nost / [ris Fl (avio) Theodo] sio Fl (avio) Arcadio et Fl (avio) Eugenio / [vetustat] e conlabsam (!) Iussu viri cl (arissimi) / [et inl (ustris) Arboga] stis comitis et instantia v (iri) c (larissimi) / [co] mitis domesticorum ei (us) / [a fundament] is ex integro opere faciun / [dam cura] vit magister pr ( ivatae?) Aelius. Also Epigraphic Database Heidelberg (EDH) .

- ↑ Werner Eck: Overcoming the crisis. Cologne until the usurpation of Silvanus (284–355). In: Ders .: Cologne in Roman times. History of a city under the Roman Empire. (Volume 1 of the history of the city of Cologne in 13 volumes ). Greven, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-7743-0357-6 , pp. 586-627.

- ↑ Werner Eck: A Roman city goes out. The Franks as new masters (355 - middle of the 5th century. ), In: Ders .: Cologne in Roman times. History of a city under the Roman Empire. (Volume 1 of the history of the city of Cologne in 13 volumes ). Greven, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-7743-0357-6 , pp. 652-692.

- ↑ Werner Eck: The space and its natural requirements. In: Ders .: Cologne in Roman times. History of a city under the Roman Empire. (Volume 1 of the history of the city of Cologne in 13 volumes ). Greven, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-7743-0357-6 , pp. 10-30.

- ↑ Werner Eck: Rome is building a city. The establishment of the Ara Romae et Augusti and the “oppidum Ubiorum” as the center of the province of Germania. In: Ders .: Cologne in Roman times. History of a city under the Roman Empire. (Volume 1 of the history of the city of Cologne in 13 volumes ). Greven, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-7743-0357-6 , pp. 77-101.

- ^ Arnold Stelzmann, Robert Frohn: Illustrated history of the city of Cologne. 11th edition. Bachem, Cologne 1990, p. 46.

- ^ Uwe Süßenbach: The city wall of the Roman Cologne. Greven, Cologne 1981, ISBN 3-7743-0187-5 .

- ^ Hansgerd Hellenkemper : Cologne. Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium. The city walls of the colony. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): The Romans in North Rhine-Westphalia. Licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , pp. 463-466.

- ↑ The Roman city wall of the CCAA ( Memento from December 16, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) on the website of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Fortress Köln e. V.

- ↑ Website of the restaurant with a historical section

- ↑ Uwe Süssenbach: The city wall of Roman Cologne. Greven, Cologne 1981, ISBN 3-7743-0187-5 .

- ^ Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Cologne. Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium. Harbor tower. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): The Romans in North Rhine-Westphalia . Licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , p. 462f. Article “ Ubiermonument ” in KölnWiki.

- ↑ a b Bernhard Irmler: CCAA. Architecture and urban development. Cologne Yearbook Volume 38 (2005).

- ↑ Ursula Bracker-Wester: The Ubiermonument in Cologne. A building according to Gaulish / Germanic dimensions. Gymnasium, magazine for culture of antiquity and humanistic education, volume 87. Winter, Heidelberg 1980, pp. 496-576.

- ↑ CIL 13, 8170 : Dis Conser | vatorib (us) Q (uintus) Tar | quitius Catul | lus leg (atus) Aug (usti) cuiu [s] | cura praeto [r] | ium in ruina [m co] | nlapsum ad [no] | vam faciem [est] | restitut [um] “To the preserving gods, Quintus Tarquitius Catulus, legate of the emperor, through whose care the praetorium, which had fallen in ruins, has been restored in a new form”.

- ↑ CIL 13, 8260 : Imp (erator) Caesar [M (arcus) Aurelius Com] | modus Anton [inus Aug (ustus) Pius Sar (maticus)] | [Ge] rman (icus) maxim [us Brittannicus (?)] | [praetor (ium?) in] cen [dio consumpt (um)] | [–––] MM [––– portic] u | [sumpt] u (?) f [i] sci res [tituit sub Di] dio | [July] ano le [g (ato) Aug (usti) pr (o) pr (aetore)] “Emperor Caesar Marcus Aurelius Commodus Antoninus Augustus, the pious, victor over the Sarmatians, greatest victor over the Teutons, victor over the Britons , has rebuilt the praetorium, which was destroyed by fire (?), with the portico at the expense of the imperial treasury under Didius Julianus, the legate of Augustus with the rank of praetor. "

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus: Res Gestae 15; 5.2-31. Res Gestae, Liber XV online, lat. And engl.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus: Res Gestae 15.8. Res Gestae, Liber XV online, lat. And engl.

- ^ Gundolf Precht: Building history study of the Roman praetorium in Cologne. Rheinland Verlag, Cologne 1973. (Rhenish excavations, 14), ISBN 3-7927-0181-2 .

- ^ Felix Schäfer: The praetorium in Cologne and other governor palaces in the Roman Empire . Dissertation, online publication on the website of the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Cologne.

- ^ Hansgerd Hellenkemper: Cologne. Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium. Forum. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): The Romans in North Rhine-Westphalia . Licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , p. 469.

- ^ Bernhard Irmler: Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium: Architecture and urban development. Munich, Techn. Univ., Diss., 2005.

- ↑ CIL 13, 8174 (with illustration).

- ↑ CIL 13, 12048 (with illustration).

- ↑ Wolfgang Binsfeld: Two new inscriptions on the Cologne amphitheater. In: Bonner Jahrbücher , 160. Butzon & Bercker, Kevelaer 1960, pp. 161–167, panels 26–30.

- ^ AE 1962, 107 : Dian (a) e | Nemesi | Aur (elius) | Avitus | tr (aex) d (edit) l (ibens) l (aetus) m (erito .

- ^ AE 1962, 108 .

- ^ AE 1941, 87 : Aquilo C (ai) et | M (arci) Versulati | um l (ibertus) | h (ic) s (itus) e (st) pp (atroni) f (aciendum) c (uraverunt) | et Murano l (iberto) (transl .: "To Aquilus, Caius and Marcus freed. Here he is buried. His cartridge had (the tombstone) made. And for the freed Muranus."). RGM, island 121.

- ^ Gerta Wolff: The Roman-Germanic Cologne. Guide to the museum and city. (6th edition) JP Bachem Verlag, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-7616-1370-9 , pp. 233-234.

- ^ Dela von Boeselager: Cologne. Residential district (building equipment): mosaics. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): The Romans in North Rhine-Westphalia . Licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , pp. 475–478.

- ↑ Thomas: Roman wall painting in Cologne , Appendix 1 (plan of the two insulae near the cathedral; p. 323, fig. 138. Plan of the house on Gertrudenstrasse.)

- ^ Waldemar Haberey : The Roman water pipes to Cologne. The technology of supplying water to an ancient city . Rheinland-Verlag, Bonn 1972, ISBN 3-7927-0146-4 .

- ^ Klaus Grewe : De aquis Coloniae. Water for the Roman Cologne. In: Heinz-Günte Horn (Ed.): Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. History in the heart of Europe. Zabern, Mainz 1990, ISBN 3-8053-1138-9 , pp. 196-201.

- ↑ Marcus Trier : Archeology in Cologne canals. In the footsteps of Rudolf Schultze and Carl Steuerungagel. In: Heinz-Günter Horn et al. (Ed.): From the beginning. Archeology in North Rhine-Westphalia. Zabern, Mainz 2005, (Writings on the preservation of soil monuments in North Rhine-Westphalia, 8), ISBN 3-8053-3467-2 , pp. 161–168.

- ^ Doris Lindemann: Baths for Cologne. From the Roman thermal baths to modern sports and leisure pools. KölnBäder, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-00-024261-8 .

- ↑ Kölner Stadtanzeiger from 17./18. November 2007.

- ^ Panegyrici Latini VII in: Wilhelm Adolph Baehrens: XII Panegyrici latini post Aemilium Baehrensium iterum . Teubner, Leipzig 1911.

- ↑ Gerta Wolff. The Roman-Germanic Cologne. Guide to the museum and city. 5th expanded and completely revised edition. P. 263.Bachem, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-7616-1370-9 .

- ^ Egon Schallmayer: Documents on the Roman Rhine Bridge in Cologne in the archive of the Saalburg Museum. Saalburg-Jahrbuch, Vol. 50. 2000 (2001), pp. 205-211.

- ↑ Maureen Carroll-Spillecke: The Roman military camp Divitia in Cologne-Deutz. In: Kölner Jahrbuch, Volume 26 (1993), pp. 321–444. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1994.

- ↑ Gerta Wolff: The Deutzer Kastell. In: This: The Roman-Germanic Cologne. Guide to the museum and city. 5th expanded and completely revised edition. Pp. 260-262. Bachem, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-7616-1370-9 .

- ^ Gundolf Precht: Cologne-Deutz. Roman fort. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): The Romans in North Rhine-Westphalia. Licensed edition of the 1987 edition, pp. 513-516. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 8502 , missing.

- ^ Fritz Fremersdorf in A. Marschall, K. J. Narr, R. v. Uslar (ed.): The prehistoric and early historical settlement of the Bergisches Land. P. 159ff. Schmidt, Neustadt 1954.

- ↑ Table 10 of the Twelve Tables Law; Latin text in the Bibliotheca Augustana ; German translation (PDF; 90 kB) .

- ↑ Bernd Paeffgen: The excavations in St. Severin in Cologne. 3 volumes. Zabern, Mainz 1997. (Kölner Forschungen, 5), ISBN 3-8053-1251-2 .

- ↑ Ulrich Friedhoff: The Roman cemetery on Jakobstrasse in Cologne. Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1144-3 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 8274 (with illustration).

- ^ Peter La Baume: Finding the Poblicius grave monument in Cologne. In: Gymnasium 78, 1971, pp. 373-387.

- ^ Gundolf Precht: The tomb of Lucius Poblicius. Reconstruction and construction. 2nd Edition. Roman-Germanic Museum, Cologne 1979.

- ^ Fritz Fremersdorf : The Roman grave in Weiden near Cologne. Reykers, Cologne 1957.

- ^ Fritz Fremersdorf: The Roman manor Cologne-Müngersdorf. De Gruyter, Berlin and Leipzig 1933 (= Roman-Germanic research, 6).

- ↑ Otto Doppelfeld: The diatret glass from the grave district of the Roman estate of Cologne-Braunsfeld. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1961 (= series of publications by the Archaeological Society of Cologne, 5).

- ^ Sebastian Ristow : The excavations of St. Pantaleon in Cologne. Archeology and history from Roman to Carolingian-Ottonian times. Habelt, Bonn 2009, ISBN 978-3-7749-3585-3 .

- ^ Elisabeth M. Spiegel: Surroundings of the CCAA: manors. In: Heinz-Günter Horn (Ed.): The Romans in North Rhine-Westphalia. Licensed edition of the 1987 edition. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-59-7 , pp. 501–508.

- ↑ Michael Gechter and Jürgen Kunow : On the rural settlement of the Rhineland in Roman times . Bonner Jahrbücher 186, 1986, pp. 377–396.

- ↑ Michael Gechter and Jürgen Kunow: On the rural settlement of the Rhineland from the 1st century BC. by the 5th century AD First Millennium Papers, British Archaeological Papers International Series 401 (1988) pp 109-128.

- ↑ Jürgen Kunow: The rural settlement in the southern part of Lower Germany. In: Helmut Bender and Hartmut Wolff (eds.): Rural settlement and agriculture in the Rhine-Danube provinces of the Roman Empire . Passauer Universitätsschriften zur Archäologie 2, Espelkamp 1994, pp. 141–197, Fig. 10.1-21.

- ↑ Law for the protection and care of monuments in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia (Monument Protection Act - DSchG)

Coordinates: 50 ° 56 ' N , 6 ° 57' E