Elisabetta Gonzaga

Elisabetta Gonzaga (* 1471 in Mantua ; † January 31, 1526 in Urbino ), from the Italian noble family of Gonzaga , Marquis of Mantua, is one of the most famous women of the Italian Renaissance . Through her marriage to Guidobaldo I. da Montefeltro , Duke of Urbino (1472–1508), she became Duchess of Urbino in 1489 and was distinguished by her education, her artistry, her patronage and her unwavering attitude towards strokes of fate. Even sister-in-law of the wife of a papal nephew, she became a victim of papal power politics, twice by papal nephews - by Cesare Borgia , the son of Pope Alexander VI. and Lorenzo di Piero de 'Medici (1492–1519), the nephew of Pope Leo X. - was expelled from her duchy and had to go into exile. Nevertheless, the court in Urbino shone under their patronage through its refined cultural atmosphere, which was idealized - and immortalized - by Baldassare Castiglione in his work “ Il Libro del Cortegiano ” (The Courtman's Book), creating a model of European court culture. Since their marriage remained childless, she and her husband adopted his nephew, Francesco Maria I della Rovere , who succeeded her as Duke of Urbino in 1508 under her reign.

origin

Elisabetta Gonzaga came from the Italian ruling family of the Gonzaga, who had already taken power in Mantua in 1328 through the overthrow of the Bonacolsi family and through a persistent policy of de facto rule over the office of "Capitano del Popolo" in 1433 through imperial enfeoffment to margraves ascended from Mantua. Later (1530) they were made dukes and married to the first houses in Italy and Europe.

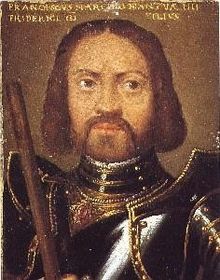

Elisabetta's father was Federico I Gonzaga , who ruled from 1478 to 1484 as the third Margrave of Mantua. In his day he was a famous condottiere who was in the service of the Dukes of Milan Gian Galeazzo Sforza (1466–1474) and Ludovico "il Moro" Sforza and who opposed the Duchy of Milan against its enemies - such as the coalitions between Pope Sixtus IV ( 1471–1484) and the Kingdom of Naples against Florence and Milan or against the then expansive policy of the Republic of Venice . At the same time, however, he was also a great art lover and patron who supplied numerous Renaissance artists with commissions.

Elisabetta's mother was Margarete Duchess of Bavaria-Munich . She was a daughter of Albrecht III. “The pious”, Duke of Bavaria-Munich (1438–1460), who was remembered for two things in particular: for the rejection of the Bohemian royal crown offered to him in 1440 and for his romantic-tragic relationship with Agnes Bernauer . His wife was Anna Duchess of Braunschweig-Grubenhagen († October 14, 1474), a daughter of Duke Erich I (1383-1427).

Elisabetta Gonzaga mainly had ancestors of German origin, as her paternal grandmother, Barbara Margravine von Brandenburg (1422–1481), came from Germany. It was not only with the dukes of Bavaria and the dukes of Braunschweig , the electors of Brandenburg and the electors of Saxony , but u. a. related via Saxony to the kings of Denmark , Norway and Sweden from the House of Oldenburg .

Despite her distinguished origins, Margarete von Bayern obviously did not quite meet the aesthetic expectations of Italian court society. Contemporary reporters describe her as small, pale, with a fat face and criticize the fact that she did not speak a word of Italian , not according to Italian fashion, but "coarsely dressed like a rich peasant woman". The portrait miniature she has preserved shows, however, that this criticism was probably not entirely justified.

Life

Childhood in the splendor of the Renaissance

Elisabetta was born in 1471 in the Palazzo of the Gonzaga family in Mantua - the capital of the margraviate of the same name - as the fourth child and second daughter of the Marquis Federico I Gonzaga. She grew up at the local court, which was located in the Palais complex in Mantua, later called “ Palazzo Ducale ”. This consisted of the “Palazzo del Capitano” from the thirteenth century, the “Magna Domus” and the fortress completed in 1406 by Bartolino da Novara († 1406/1410) - one of the most famous military architects of his time - the “Castello di San” Giorgio. ”The Gonzaga residence in Mantua was one of the most important sights in Lombardy even then .

In her childhood, Elisabetta could still see the frescoes by the painter and medalist Antonio di Puccio Pisano, called " Pisanello " (1395–1455) in the Castello di San Giorgio and in the castle chapel. She was also able to witness the decoration of the "Camera degli Sposi" in the Castello di San Giorgio - probably the most remarkable room in the whole palace - which was decorated with frescoes by the famous Italian painter Andrea Mantegna between 1465 and 1475 . These show the court of the Marquis of Mantua during the lifetime of their grandfather, Ludovico III. Gonzaga , Margrave of Mantua (1444–1478), called "il Turco" (the Turk) surrounded by his family. The art of Pisanello and Mantegna - who worked for their family for half a century, from 1459 to 1506 - was therefore an integral part of the cultural atmosphere in which Elisabetta grew up.

During her youth there was a further expansion of the palace complex, because in the years 1478 to 1484 on behalf of her father by the Tuscan architect and sculptor Luca Fancelli (* approx. 1430, † approx. 1502) another palace, called "Domus Nova" (the New house) was built on the shores of Lake Mantua. At the same time he undertook work on the Palazzo del Podestà and in 1472 - after the death of "uomo universale" (polymath) Leon Battista Alberti - his plans for the Basilica of Sant'Andrea in Mantua, which became an important model for the architecture of the Italian Renaissance has been.

The clock tower (Torre dell'Orologio) and a number of aristocratic palaces, such as the Palazzo Arrivabene, were also built by Luca Fancelli in Elisabetta's youth in the city of Mantua, which thereby lost its medieval appearance and transformed into a city of the Renaissance.

Another building project by her father involved the ruined castle of Marmirolo , the ruins of which were converted into a luxurious Renaissance villa by the famous architect Giulio Romano .

Elisabetta therefore grew up at the up-and-coming court of Mantua in a very cultivated atmosphere, where her father, a great friend of the arts, tried to surpass the regional rulers in splendor and patronage despite constant campaigns and to bind the first artists of his time to his court.

Elisabetta, however, had little opportunity to enjoy her father's company, as he was mostly absent because of his numerous campaigns and only ruled for six years. Since her mother did not seem suitable for a regency, the civil administration was in the hands of Eusebio Malatesta and the military administration was in the hands of her uncle, the condottiere Francesco Secco d'Aragona, Conte di Calcio (1423-1496), during her father's absence was the husband of her (illegitimate) aunt, Caterina Gonzaga, since 1451.

While she was still a child, Elisabetta became an orphan, as she lost her mother in 1479 at the age of eight and in 1484 - at the age of thirteen - also her father. Until her marriage in 1488/89, she therefore lived at the court of her eldest brother, Francesco II Gonzaga , who had succeeded his father Federico I as the 4th Margrave of Mantua in 1484.

Family Relations and Politics

Elisabetta grew up in Mantua in the company of her siblings, who later played a special role in her life as she had no children herself. Although Elisabetta's sisters-in-law were selected according to political criteria, they not only served to expand her social, political and cultural horizons, but as an extended family often had a very significant personal impact on their lives.

Mantua was a small principality whose existence was threatened not only by the expansion efforts of the rival Italian neighboring states - especially the strengthening Papal States and the expanding Republic of Venice - but also by the desires of the great European powers, the House of Austria and France . Family policy was therefore an indispensable part of security policy and crucial for continued survival. Her siblings were therefore used very specifically in the interests of strengthening the dynasty:

- Francesco II Gonzaga (1466–1519), Elisabetta's eldest brother, followed in 1484 as Margrave of Mantua, took on the role of father despite his 18 years with Elisabetta, which meant that she had a particularly close relationship with him throughout her life. In 1490 he married Isabella d'Este , the eldest daughter of Ercole I. d'Este , Duke of Ferrara , Modena and Reggio (1471–1505) and Eleonora of Aragon, a daughter of Ferdinand (Ferrante) I , King of Naples (1458-1494). Isabella was arguably the most brilliant lady of the Italian Renaissance, praised by contemporaries as “prima donna del mondo” because of her cultural and political influence. She developed into Elisabetta's closest friend. Both visited each other, exchanged letters and discussed the best way to tie the most interesting writers, musicians, painters, diplomats and philosophers to their courts. Elisabetta recommended her sister-in-law, when she was dissatisfied with her portrait painted by Andrea Mantegna , “because it was in no way like her” , to contact Giovanni Santi , Raphael's father , to have a true-to-life portrait made.

- Chiara Gonzaga (1464–1503), with her eldest sister, Elisabetta was particularly closely connected, as she had taken over the role of her mother. She was married to Gilbert de Bourbon, Comte de Montpensier (1443–1496) on February 24, 1481, in order to secure relations with France - which showed a massive greed for Italian territories - who married when King Charles VIII invaded in 1494 . of France in Italy, during the conquest of Florence and in 1495 during the occupation of the Kingdom of Naples, and was therefore raised to Duke of Sessa ( Sessa Aurunca ) in the province of Caserta and appointed (French) Viceroy of Naples .

- Sigismondo Gonzaga , Elisabetta's second brother, was appointed cardinal deacon with the titular church of Santa Maria Nuova ( Santa Francesca Romana ) in 1505 thanks to the joint efforts of Elisabetta Gonzaga and her bustling sister-in-law, Isabella d'Este Gonzaga , was Bishop of Mantua from 1511 to 1521, and papal in 1512 Legate in Bologna and in 1521 in the Ancona march . However, the two ladies did not succeed in helping the amiable but meaningless Sigismondo Gonzaga to the papal throne.

- Giovanni Gonzaga, Marchese di Vescovado (1474-1525), Elisabetta's third brother, was in 1494 with Laura Bentivoglio († 1523), daughter of Giovanni II. Bentivoglio , Lord of Bologna, and the Costanza Sforza from the House of Lords of Pesaro married . This was to secure relations with the Duchy of Milan, which was ruled by the Sforza. Their descendants were raised to the rank of imperial prince in 1593 and are still based in Italy today.

Duchess of Urbino

Elisabetta's marriage - like that of her siblings - was concluded for strategic reasons in order to create an alliance with the Duchy of Urbino , which was supported by the military fame and cultural importance of her father-in-law, Federico da Montefeltro , Duke of Urbino (1444-1482), had become an important factor in Italian politics.

Elisabetta married on February 11, 1489 Guidobaldo I da Montefeltro , Duke of Urbino (1482-1508), Count of Montefeltro . Elisabetta Gonzaga became Duchess of Urbino at the age of eighteen.

The reception of the new Duchess in Urbino was staged as a fairytale-like classical homage: women and children walked down the hills of Urbino with olive branches in their hands while a choir sang a cantata composed for the event. Nymphs appeared and a goddess of cheerfulness brought the congratulations of everyone present.

The Palazzo Ducale von Urbino was one of the most magnificent buildings of its time. It was spectacular not only because of its architecture, but also because of the splendid interior with precious furniture, vases made of silver, curtains made of gold fabric and silk, as well as a large library of Greek and Latin books, which her father-in-law, the great condottiere and art lover Federico da Montefeltro , Duke of Urbino, and had them decorated with splendid bindings. The secondary residence of Elisabetta, the Palazzo Ducale in Gubbio , which was built in 1477 by Francesco di Giorgio Martini for her father-in-law , was less sumptuous, but similarly furnished .

In Mantua, Elisabetta Gonzaga had acquired a considerable education in the sense of humanism , even for her time and her social circle , was artful, self-confident, open-minded and virtuous, which enabled her to manage the court of Urbino, which after the death of her mother-in-law Battista Sforza was orphaned to be brought back to life by - in the spirit of her father-in-law - she gathered poets, painters, sculptors, musicians, but also statesmen and clergymen around her to discuss questions of art, politics or social development with them to discuss. Like her husband, Duke Guidobaldo I, she became a knowledgeable patron who succeeded in renewing Urbino's reputation as a model for a court of the Italian Renaissance with a high intellectual culture.

The luck of Elisabetta was not without a shadow, however, because it turned out that Guidobaldo was a good general, a humane ruler, a great friend of classical education and a knowledgeable patron of the arts, but that he was plagued by various diseases throughout his life, and was impotent.

Relationship with the Borgia

In the life of Elisabetta, the relations with the originally Spanish family of the Borgia , who lived during the pontificate of Pope Alexander VI. In the years 1492 to 1503 Italy was in the forefront of war and politics. have a special meaning, as this was related by marriage to Elisabetta several times, but still expelled her from the Duchy of Urbino.

The first approach to this house was through her youngest sister Maddalena Gonzaga (* 1472 in Mantua, † January 8 (August 8, 1490 in Pesaro ). She was married to Giovanni Sforza (1466–1510), Lord of Pesaro and Gradara (1483–1500 and 1503–1510), but died soon after their marriage as a result of an unfortunate delivery on August 8, 1490. Almost three years later received Elisabetta's widowed brother-in-law, Giovanni Sforza, an offer he could not refuse: Lucrezia Borgia , the then only thirteen-year-old daughter of Pope Alexander VI. offered as a wife, as this needed the political support of the House of Sforza, whose main line then ruled the Duchy of Milan. Elisabetta first came into brotherhood with the Borgia family through this marriage, which was concluded in the Vatican on June 12 (February 2) 1493 . However, their unpredictability soon became apparent, as this marriage was initiated by Pope Alexander VI in 1497 due to changed political circumstances. was repealed under the pretext of alleged impotence of Giovanni. The latter retaliated by claiming that Lucrezia had committed incest with her father and brother .

However, this was not to be the only reference Elisabetta had to the house of the Borgia. Pope Alexander VI meanwhile, with the help of his son, Cesare Borgia in Viana (cardinal until 1497), he tried to bring the ecclesiastical territories alienated from local dynasties back under his direct control. At the same time, King Ludwig XII. of France (1498–1515), an advance into Italy started in 1500 Ludovico Sforza - the widowed husband of Beatrice d'Este (1475–1497) (sister of Isabella d'Este, Elisabetta's sister-in-law) - from the Duchy of Milan expelled and planned to split up with the Pope and the Republic of Venice Italy - and thus Mantua, Ferrara, Urbino and Bologna. Cesare Borgia was there by King Ludwig XII. 1498 raised to the French Duke of Valentinois (in the Dauphiné ), married in 1499 to his niece, Charlotte d'Albret (1480–1514), and in the same year appointed as his administrator in Italy.

Thanks to his spies, Elisabetta's brother, Francesco II Gonzaga, was well informed about these developments and the resulting threat to the existence of his margravate. He informed his neighbors and implored his sister Elisabetta not to travel to Rome , despite the jubilee year of the Church in 1500 , so as not to fall into the hands of the Borgia. However, Elisabetta was fearless and convinced that, in order to preserve the Duchy of Urbino and the Margraviate of Mantua, it would be tactically better not to rely on confrontation, but on friendly relations with the Borgia. She informed her brother of this in a letter dated March 21, 1500 and traveled to Rome. It speaks for her diplomatic skills that she succeeded there in winning Cesare Borgia as godfather for her nephew, the heir of the Margraviate of Mantua, Federico II Gonzaga , and thus also to bind Cesare to the Gonzaga family through a "spiritual kinship" .

Her brother Francesco II was less convinced of the trustworthiness of Cesare and decided to leave his service as general of the Republic of Venice and enter imperial service to secure his state. On September 20, 1501, he was appointed commander-in-chief of the imperial troops in Italy and authorized to recruit up to 8,000 men in the imperial territory. Outwardly, however, the alliance with the Borgia remained part of the Gonzaga's official family policy.

Another point of contact with the Borgia resulted from the threat posed by Cesare Borgia to the Duchy of Ferrara, the home of Elisabetta's sister-in-law Isabella d'Este . Here, too, Elisabetta urged that the Borgia cooperate to forestall an expulsion. Fortunately, this also corresponded to the interests of Pope Alexander VI, who endeavored to elevate his house to the rank of princely and to marry by marriage with the old dynasties of Italy. Pope Alexander therefore made the proposal to Ercole I. d'Este , the Duke of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio (1471-1505), the heir to the duchy, Alfonso I. d'Este - Elisabetta's brother-in-law - with his divorced, remarried and now widowed daughter, to marry Lucrezia Borgia.

For the Estonians - one of the oldest ruling houses in Italy - this proposal was a provocation: the heir to the duchy should marry the illegitimate daughter of a cardinal and later pope, who had already had two problematic marriages and whose reputation was due to the malicious rumor that she was "Daughter, wife and daughter-in-law of the Pope" seemed more than attacked. In view of the given balance of power and an astronomical dowry, however, this was an offer that Ercole I. d'Este could not refuse.

Lucrezia's journey from Rome to Ferrara took place in the greatest possible splendor, but because of the wintry conditions in January 1502 in small stages. Two miles from Gubbio , one of the cities of the Duchy of Urbino, Elisabetta Gonzaga welcomed Lucrezia and her entourage, whom Cesare Borgia had also joined, accompanied them as their guests into the city and placed them in the ducal palace there.

On February 18, the wedding procession arrived in Urbino, the capital of the duchy, where Duke Guidobaldo awaited Lucrezia with his entire court and brought them to the city, which was decorated with garlands and the coats of arms of Borgia, Montefeltro and the King of France Palazzo Ducale accompanied where she and her close companions were accommodated, while the hosts withdrew to another residence out of courtesy. When she left on January 20, Elisabetta decided to accompany her future sister-in-law Lucrezia on her trip to Ferrara to the wedding celebrations, out of consideration for her Estonian friends and probably also to counter the Borgia's desire for expansion through a demonstrative gesture of friendship. She took it in the litter that Pope Alexander VI. Lucrezia had given the place next to this one. Cesare Borgia, the Duke of Valentinois , however, returned to Rome for urgent business.

Elisabetta Gonzaga took part in the wedding, which was celebrated in Ferrara from February 3 to 8, 1502 with tremendous effort, with banquets, balls, theater performances, concerts, moresques and tournaments. During the festivities in Ferrara, five women were mentioned most by contemporary reporters for the elegance of their clothes: Lucrezia, Isabella, Elisabetta, her friend Emilia Pio and the Marchesa di Cotrone. The chronicler B. Capilupio paid a special compliment, who wrote, "Although Lucretia had more to do with men than the Margravine of Mantua and the Duchess of Urbino, she could not compare herself to them in an intelligent conversation" through this marriage of Alfonso I. d'Este, the brother of her sister-in-law Isabella d'Este - Elisabetta became the sister-in-law of Lucrezia Borgia for the second time. The fact that Lucrezia's brother Cesare did not take part in these festivities, as did the husband of Elisabetta, Guidobaldo I da Montefeltro and her brother, Francesco II Gonzaga, shows that despite the festivities there was a latent tension due to the threatening demeanor of Cesare Borgia. who had stayed in their capitals to be prepared for nasty surprises. It was therefore to be foreseen that this festival would by no means be the last encounter with the Borgia.

After the brilliant celebrations in Ferrara and the demonstratively friendly dealings with her new sister-in-law, Lucrezia Borgia, now Duchess of Ferrara, Elisabetta Gonzaga traveled to Venice with Isabella d'Este and Emilia Pio, visited the sights there and also the one who lived there in exile Caterina Cornaro (1454–1510), Queen of Cyprus (1474–1489), who resided in Asolo Castle after the cession of her Kingdom of Cyprus to the Republic of Venice , where she maintained a famous court frequented by artists and writers. Elisabetta was so enthusiastic about Venice that she declared that Venice was more wonderful than Rome. At the end of March, the two sisters-in-law went to Mantua and then to Porto Mantovano .

In the meantime, a new connection between Elisabetta's family and the Borgia was developing. Since the spring of 1502, Cesare Borgia urged a marital union with the Gonzaga family by proposing that his only legitimate daughter, whom he had with his wife Charlotte d'Albret, the two-year-old Louisa Borgia (* May 17, 1500, † 1553) to marry Federico Gonzaga, Elisabetta's nephew, heir to the Margraviate of Mantua . In the early summer of 1502 a marriage contract was signed, with a royal dowry being provided. At the same time, Pope Alexander VI. - the grandfather of the infant bride - promised to raise Elisabetta's brother, Sigismondo Gonzaga, to cardinal for a fee of 25,000 ducats.

Elisabetta was related by marriage to the Borgia once more - this time through the childlike bride of her nephew.

First expulsion from Urbino

Elisabetta was convinced that through her consistent policy of alliance with the Borgia she had successfully averted any danger of annexation not only of her own Duchy of Urbino, but also of the Margraviate of Mantua and the Duchy of Estonia.

Elisabetta was enjoying the security in her family in Mantua when, at the end of June 1502, her husband, Duke Guidobaldo I, suddenly appeared breathless, in loose clothing, accompanied by only four men on horseback in Mantua. He said that Cesare Borgia, who had recently told him that he "loved him like a brother" and asked him to be allowed to march through the Duchy of Urbino with his troops, suddenly attacked Urbino on June 21st and occupied the city , whereby he himself only managed to escape with little difficulty and to bring his little nephew Francesco Maria I della Rovere to safety.

Elisabetta's policy of "appeasing" the Borgia had obviously failed because while she was unsuspecting in Mantua, everything valuable was stolen from the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino by Cesare. So disappeared in a long column of mules and wagons, loaded with chests filled with gold, silver dishes and pictures, the library famous throughout Italy, the collection of ancient works of art, the large tapestries, furniture and curtains. Cesare therefore added to his titles as Duke of Valentinois , Duke of Romagna and of Camerino also those of Duke of Urbino.

Elisabetta was desperate and wrote in a letter, “I have been robbed of a high position, my home and my wealth and now I have also lost my sister (her beloved sister Chiara had just died); who has always been like a mother to me. "

Her brother, Margrave Francesco, was also angry at this betrayal and intervened in Pavia with King Louis XII. from France - in vain - in favor of his sister. Margravine Isabella, on the other hand, continued the "family" contacts with Cesare despite outrage. Just a few days after the expropriation of her sister-in-law, Isabella intervened with Cesare to save the dowry from Elisabetta's friend Emilia Pia. However, Isabella was tempted by her passion for collecting to ask Cesare - successfully - to hand over two exquisite pieces from the stolen art collection of Urbino for her own collection, an ancient Venus and the famous "ancient" sleeping one made by the then young Michelangelo Cupid.

Divorce and marriage to Cesare Borgia?

At this time, the well-kept private secret of Guidobaldo's impotence became a political issue, as the papal court saw it as the possibility of a "diplomatic" settlement of the expulsion of the Elisabettas family from the Duchy of Urbino. Cesare therefore made an offer to Elisabetta and Guidobaldo in a strictly confidential manner: Their marriage would be annulled by the Pope - for lack of execution - Guidobaldo could be made cardinal if his duchy was renounced, and Elisabetta could be married to a French aristocrat. In the short term, the possibility of Elisabetta's marriage to Cesare Borgia was even considered! With her own calm and strength of soul, Elisabetta rejected this offer by writing that she would not leave Guidobaldo and would rather accept him as a brother than as a husband.

First exile in Venice

After the rejection of his plans, Cesare Borgia increased the pressure on Francesco Gonzaga not to grant asylum to Guidobaldo, excommunicated by the Pope, in Mantua, but to hold Elisabetta there in order to isolate Guidobaldo. In order not to endanger his own rule, Francesco asked his brother-in-law to leave Mantua. Robbed of his duchy, banned from the church and rejected by his brothers-in-law, Guidobaldo went to Venice, where he had served as a general in 1495 and where he was accepted by Elisabetta's brother, Sigismondo Gonzaga.

Elisabetta showed her character one more time, because, as her brother wrote to Cesare, neither conversations, persuasion or requests, neither fear nor threats had any effect on Elisabetta. She was determined to go into exile with her husband, otherwise the Duke's life would be in great danger. She wouldn't leave him even if it meant they'd die together. She therefore went into exile with Guidobaldo in Venice. Through frequent correspondence with her sister-in-law Isabella d'Este Gonzaga, she remained in close contact with Mantua.

Attempt to return to Urbino

In October 1502, in the increasingly hopeless mood of the exiles, unexpectedly burst into the news that the generals Cesares had conspired against him and that the population of Urbino had risen and expelled Cesare's garrison. Guidobaldo immediately went by secret routes to Urbino, where he was received with enthusiasm by the population.

Elisabetta pawned her jewelry and asked her brother Francesco to send soldiers to Guidobaldo so that he could regain control of his duchy. However, Francesco could not help because he was away from Mantua. After he had assured Cesare of his friendship in a letter in the autumn of 1502, he had cautiously gone to France to secure his rule and was there on October 26th in Lyon by King Louis XII. received benevolently.

After a short time, however, Guidobaldo's position in Urbino deteriorated, as Cesare Borgia succeeded in luring away his allies one after the other through promises. On December 7th, the situation became untenable, Guidobaldo was forced to surrender and sign an agreement with which he ceded the duchies of Urbino and Camerino to Cesare and received some fortresses as a "compensation" for this and the promise that he would not be after Would seek life.

Guidobaldo then had all the fortresses left to him demolished, since he understood that he could only rely on the people, not on fortresses that he could not defend without means. Then he disappeared from the scene for months with the help of the Counts of Pitigliano from the House of Orsini in order to avoid attacks by Cesare.

In the meantime, Elisabetta was living in Venice without news, afraid for her husband's fate and in great financial difficulties. When she was again proposed to annul her marriage and make Guidobaldo cardinal, Elisabetta declared herself ready to save his life. Cesare's actions, who on December 31, 1502, invited the rebellious generals to a reconciliation meeting in Senigallia , shows that their concern for his life was not unfounded . There he seized them through a perfidious betrayal, had them tortured and most of them murdered. This crime also found admirers for its daring. The historian - and Bishop of Nocera - Paolo Giovio (1483–1552) described it as "il bellissimo inganno di Senigallia" (the beautiful illusion of Senigallia). Elisabetta's sister-in-law, Isabella d'Este, also congratulated Cesare on the successful ruse and sent him a hundred masks for the carnival so that he could relax after the latest excitement.

Elisabetta, on the other hand, was not in the mood for carnival. She therefore considered accepting her brother Francesco's invitation to come to France as Queen Anne de Bretagne's maid of honor , since her husband had disappeared and her own life was also in danger. This did not happen, however, because in January Guidobaldo suddenly turned up in Venice to see Elisabetta - despite the danger of his life, illness and exhaustion. His arrival did not go unnoticed, as soon afterwards Pope Alexander VI. wanted to force the Venetian ambassador through admonitions and threats to extradite the banned and expelled duke. However, the Republic of Venice remained steadfast, which is why Guidobaldo was able to stay.

First return to Urbino

The possibility of a return to Urbino arose only after the death of Pope Alexander VI. and the fall of Cesare Borgia in 1504. After a brief interregnum, the bitter opponent of the Borgia, Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, was elected Pope as Julius II (1503 to 1513). This was a brother-in-law of Guidobaldos, since his brother Giovanni della Rovere , Duke of Sora and Arce (1457-1501), was married to Giovanna da Montefeltro, the eldest sister of Guidobaldos.

Elisabetta and Guidobaldo were therefore able to return to their Duchy of Urbino in 1504. Since the Palazzo Ducale had been looted by Cesare Borgia, Elisabetta tried to recover the lost works of art. She had found out that her sister-in-law Isabella had received the two works of art from Urbino from Cesare, so asked them to return them. However, the latter refused to surrender these showpieces from their collection. The human quality of the rulers of Urbino was evident in the reaction to this snub: Guidobaldo suggested that Isabella should keep the works as a gift and Elisabetta said that Isabella only needed to ask and they would have liked to give her these works.

Since Elisabetta and Guidobaldo had no children, they adopted the fourteen-year-old nephew of Duke Guidobaldo, Francesco Maria I della Rovere (1490–1538), the son of his sister Giovanna da Montefeltro and Giovanni della Rovere, Duke of Sora and Arce, in 1504 was also a nephew of Pope Julius II.

In 1506 Pope Julius II visited Urbino and again at the beginning of March 1507 with a large retinue of cardinals, other clergy and officers on the way back from Bologna - which he had just reintegrated into the Papal States - came to Urbino for one day to see there to stop on the way to Rome. After his departure, many of his entourage stayed behind.

Another chapter in relations with the Borgia ended on March 12 of the same year, when Elisabetta's “brother-in-law” - and dispossessed - Cesare Borgia was killed in action in Spain near Pamplona .

Widow and regent for her adopted son

A year later, Elisabetta lost her beloved but often sick husband on April 11, 1508, whereupon his nephew and their adopted son Francesco Maria I della Rovere took over the rule in the Duchy of Urbino under the reign of Elisabetta.

She probably contributed to the fact that her family's influence on the Duchy of Urbino was further strengthened in 1509, as she married her adopted son, the young Duke Francesco Maria I della Rovere, to her niece Eleonora Gonzaga .

Thanks to the support of his uncle, Pope Julius II, Elisabetta was able to enjoy the rise of her adopted son. He regained the rule of Senigallia , was, like his father, appointed captain general of the church in 1509 , distinguished himself in the campaigns against Ferrara and Venice and in 1512 received important rule over Pesaro from the Pope . This happy time, when Urbino was able to renew the splendor of the court during the reign of Federico da Montefeltro, ended with the death of Pope Julius II, who died on February 21, 1513.

Second expulsion from Urbino

No sooner was Giovanni de 'Medici (1475–1521) - a son of Lorenzo il Magnifico and Clarice Orsini - elected Pope as Leo X at the age of 37 (1513–1521), he felt the need, based on nepotism his predecessor to establish his family as princes in Italy. He was therefore looking for a suitable principality for his nephew, Lorenzo di Piero de 'Medici , whom he had made de facto lord of Florence in 1513.

Although the Gonzaga welcomed the Medici hospitably after their expulsion from Florence in 1494 , the Duchy of Urbino - where Elisabetta Gonzaga ruled - became the target of papal desires. A pretext was constructed - Guidobaldo's lack of military support in the battle of Marignano on September 13 and 14, 1515 - in which King Francis I of France (1515–1547) had defeated the army of the papal "Holy League" to accuse Guidobaldo .

In view of the impending sanctions, Elisabetta, the highly respected Duchess widow of Urbino, traveled to Rome with a large retinue in March 1516, lived in the palace that Pope Julius had given to the Duke of Urbino and intervened with the Pope not to commit the ingratitude and expropriate his former benefactors. As this was in vain, Elisabetta asked her brother Francesco II Gonzaga, Margrave of Mantua, to send his most experienced diplomat, Baldassare Castiglione , to Rome to change Pope Leo X's mind. However, these efforts were just as unsuccessful as the attempts of Elisabetta's nephew, Federico II Gonzaga, the heir of the Margraviate of Mantua, to ask his employer, King Francis I of France, for intercession.

In June 1516, Duke Francesco Maria I was excommunicated, declared deposed and expelled from the duchy, which was occupied by Pope Leo X with papal troops and transferred to his nephew, Lorenzo di Piero de 'Medici in September. Although this in no way came close to his grandfather of the same name Lorenzo il Magnifico (the Magnificent), however, through his daughter, Caterina de 'Medici (1519–1589), she did the job through her marriage to King Henry II (1547–1559) Queen of France in 1547 and regent for many years after 1559, a contribution to European history.

Second exile

For Elisabetta Gonzaga this meant having to flee the beloved Urbino again to go to her brother with her adoptive son Duke Francesco Maria I della Rovere, her niece Eleonora Gonzaga della Rovere and her little son Guidobaldo II della Rovere (1514–1574) to go into exile in Mantua. While Isabella d'Este Gonzaga tried to raise money from Florentine and Venetian banks to support her impoverished relatives, Elisabetta was forced to melt down even the splendid silver work made for her by Raffaello Sanzio , better known as Raffael von Urbino (1483-1520).

In September the news reached her that Lorenzo di Piero de 'Medici had been officially appointed Duke of Urbino.

Pope Leo X was not yet satisfied with this success. A clever move had to be found to drive the overthrown ducal family from Mantua and at the same time to prevent the Gonzaga from turning away from the service of the church and entering into imperial service. To this end, Leo X appointed Elisabetta's nephew, the barely twenty-year-old heir of the Margraviate of Mantua Federico II Gonzaga, as General Captain of the Church, but asked him to expel Elisabetta and her family from Mantua. Despite the intensive efforts of Elisabetta and Castiglione, Federico II did not want to renounce this honorable office, so forced Francesco Maria I to leave Mantua and seek refuge in the Republic of Venice.

Despite this recent setback, Elisabetta did not lose heart, but supported the plans of her adoptive son Francesco Maria I to recapture his Duchy of Urbino by force. He marched into Tuscany with a small troop in February 1517 , but at the same time wrote a letter to the College of Cardinals in which he laid out his rights to the duchy and the illegality of expropriation. Although he was condemned as a "rebel against the Holy Church", he was able to prove himself in several skirmishes with papal troops, which led to negotiations and a settlement. As compensation he was to get back 100,000 scudi , the artillery and the precious library of Federico da Montefeltro - but not the Duchy of Urbino.

For Elisabetta this meant living in exile in Mantua for more years under difficult financial circumstances. She found some consolation in the fact that this enabled her to live in close contact with her brother and sister-in-law Isabella d'Este.

Hope to return to Urbino

The year 1519 brought about important changes for Elisabetta through a series of deaths: Her beloved brother Margrave Francesco II Gonzaga died on March 29, 1519. He was not only loved by his children, by Elisabetta and by his widow Isabella d'Este, but also mourned by Lucrezia Borgia , who was previously said to have more than friendly feelings for Elisabetta's brother. The margraviate of Mantua passed on to Elisabetta's nephew Federico II Gonzaga (1500–1540).

However, three months later, Lucrezia Borgia was also dying after her eighth birth. Contrary to initial skepticism, she had fulfilled her task as Duchess in an exemplary manner, went to confession every day and died on June 24, 1519 in Belriguardo as a member of the third order in the habit of the Franciscans .

Another death aroused far less pity on Elisabetta: On May 4, 1519, Lorenzo di Piero de 'Medici, the usurper of the Duchy of Urbino, died at the age of 26 in Careggi’s Villa Medici . He died just a few days after his wife Madelaine de la Tour d'Auvergne (* 1495, † April 28, 1519) and two weeks after the birth of his daughter - Caterina de 'Medici (1519–1589) who served as Queen of France and Regent should go down in history.

The death of the usurper increased the expectation that this could result in a return for Elisabetta and her family to Urbino. Therefore Castiglione was immediately sent as envoy to Pope Leo X in Rome. This with the order to achieve the return to Urbino via a dynastic connection between the Medici and the della Rovere: The newly born Caterina de 'Medici was to be married to the five-year-old great-nephew of Elisabettas, Guidobaldo II. Della Rovere . Pope Leo X remained unmoved: He had other plans for his niece and also for the Duchy of Urbino: It was incorporated into the Papal States. San Leo and Montefeltro , however, were ceded to his relatives in Florence.

Second return to Urbino

After this setback, Elisabetta could not have suspected that a change for the better would take place a little later. At the beginning of December 1521, the news of the death of Pope Leo X reached Venice. Francesco Maria gathered an army and with the support of his cousin Federico II, after a brief siege, recaptured his duchy from the papal garrison. Shortly after the election of the new Pope, Hadrian VI. (1522–1523) Elisabetta also returned to Urbino after 5 years of absence, which was officially transferred back to her adoptive son in the spring of 1522. The exemplary and ascetic Pope Hadrian VI. died after a year, on September 14, 1523, as some suspected, of poison.

A new hope arose for Elisabetta: her brother Cardinal Sigismondo Gonzaga , who had already been considered a “papabile” (promising candidate for the Pope) when the predecessor was elected, could be elected Pope this time. However, Sigismondo was now tired and ill and his influence made the choice of another candidate possible. It was Cardinal Giulio de 'Medici who ruled as Pope Clement VII from 1523 to 1534.

In Urbino this news was received with great disappointment and alarm, because instead of Elisabetta's brother a member of the very family had been elected that was responsible for the second expulsion of Elisabetta and her family. It turned out, however, that there was no risk of another expulsion from Urbino.

Again regent and death

Due to the numerous absences of her adoptive son, Elisabetta was very often again regent of the Duchy of Urbino, where the subjects were grateful for the wisdom and kindness of the regent after the mismanagement of Lorenzo di Piero de 'Medici, who had ruled from Florence by governors. In summer she resided in the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino, but in winter because of the milder climate in Pesaro.

When her brother Cardinal Sigismondo Gonzaga died in 1525, Elisabetta was so weak that her nephew, Federico II Gonzaga asked Emilia Pio to bring her the news carefully so as not to endanger her health. Elisabetta was the last survivor of the family of her generation. Her sister-in-law Isabella d'Este, however, saw this death as an opportunity to make her twenty-year-old son Ercole Gonzaga (1505–1563) a cardinal, so intervened personally with the Pope in Rome and in 1527 actually had success.

Elisabetta had grown old and weak in the meantime and needed long breaks in which she talked about the past times in the company of Emilia Pia, the only one left of her old friends. The faithful Baldassare Castiglione had already been appointed nuncio to Emperor Charles V in Madrid by the Pope in 1524 . She finally died on January 31, 1526, in the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino, but far from her family, as her adoptive son was with his family in northern Italy to do military service there.

She was spared the Sacco di Roma , the sack of Rome by imperial troops, in which two of her nephews faced each other: Federico II. Gonzaga was commander of the papal league, while another nephew, Charles III. de Bourbon-Montpensier , the " Connetable of Bourbon", commanded the imperial troops, which - after his death, out of control and without pay - invaded Rome on May 6, 1527 and plundered for days. Everyone who had known her suspected that an era was coming to an end with her. Even Pope Clement VII from the Medici family, who was responsible for her second expulsion, regretted the loss of Elisabetta, as she was "donna rara et de singular virtu alli tempi nostri ..." ("one of the rare women who was one of our Time unique virtue ”). Baldassare Castiglione, who himself was near the end of his days, wrote from Spain: “ Essa molto piú che tutti gli altri valeva ed io ad essa molto piú che tutti gli altri era tenuto… ” (German: “She was worth much more than everyone else and I valued her much more than anyone else ”).

Cultural meaning

The city of Urbino ( province of Pesaro and Urbino ) was since the reign of the parents of Elisabetta's husband, Federico da Montefeltro , Duke of Urbino (1444-1482) and his wife Battista Sforza a cultural center, at whose court Piero della Francesca , Francesco di Giorgio Martini and Giovanni Santi, Raphael's father worked, one of the most important libraries and the world-famous Palazzo Ducale was built by Luciano Laurana . The cultural significance therefore far exceeded the modest size of the duchy and the city (today around 16,000 inhabitants).

This tradition lived on under Elisabetta Gonzaga and Guidobaldo I. da Montefeltro, Federico's son and his wife, the Urbino once again the most elegant and refined court in Italy, and the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino the preferred meeting place for intellectuals and cultural workers and for the forum of cultured des courtly conversation.

A - probably idealized - image of this intellectual "salon" by Elisabetta can be found in the most famous work of Count Baldassare Castiglione (* December 6, 1478, † February 2, 1529), " Il Libro del Cortegiano " (The Court Man's Book). It describes conversations that took place in 1507 in connection with the visit of Pope Julius II to Urbino for four days in the Palazzo Ducale of Urbino under the patronage of Elisabetta Gonzaga.

Castiglione deals with the question of what qualities an ideal courtier should have in the form of dialogues that he puts in the mouths of a number of important personalities of aristocratic origin with a political, military or spiritual background. At the same time he paints an idealized picture of refined courtly ways of life, which he relocates to Elisabetta's court in Urbino, which appears as the epitome of lost ideals, as a place of cheerful joy and high philosophy from an earlier, happier, halcyon time.

It is noteworthy that Castiglione let these conversations take place under the leadership of women. As Duchess, Elisabetta Gonzaga was the patroness of the talks, adored by all. However, she left their leadership to her witty sister-in-law, Emilia Pio da Montefeltro, the wife of Antonio da Montefeltro, Conte di Cantiano († 1508), an illegitimate half-brother of Elisabetta's husband.

A look at the participants in these conversations mentioned by Castiglione shows the breadth of the intellectual and political environment in which Elisabetta moved and at the same time the special attraction that she exerted on important contemporaries.

- Pietro Bembo (1470–1547), philosopher, poet, passionate admirer of Lucrezia Borgia - to whom he dedicated his work “Gli Asolani” on love - lived at the court of Urbino from 1506 to 1512 and said of Elisabetta: “I have many excellent ones and seen and heard of noble women who were equally famous for certain qualities, but in her alone among women all virtues were united. I have never seen or heard of anyone who was her equal, and I know very few who even came close to her. ”He ended his days in pious renunciation as a cardinal of the Catholic Church .

- Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena (1470–1520) an Italian writer and poet (including the important comedy "la Calandria") was secretary to Pope Leo X , later a cardinal , who eventually became an old papa (Eng: about the other) because of his power Pope).

- Alfonso Ariosto (1475–1525), to whom the first volume of the Hofmann's book was dedicated after Elisabetta's death, was a cousin of the more famous Ludovico Ariosto (1474–1533). It was through him that Castiglione received the suggestion to write this book, but it was originally to Franz Duke of Angouleme - later King Francis I of France.

- Gasparo Pallavicino Marchese di Cortemaggiore (1485–1511), friend of Castiglione, Castiglione suggested to him to discuss questions of exemplary behavior.

- Ludovico da Canossa , a nobleman from Verona , Bishop of Tricarico , later Bishop of Bayeux , envoy of King Francis I of France in Venice (1476–1532)

- Cesare Gonzaga († 1512 in Bologna), general, diplomat and poet, cousin of Castiglione.

- Ottaviano Fregoso (* 1470 in Genoa, † 1524 in Ischia ), a nephew of her husband (son of Gentile da Montefeltro , an illegitimate sister of Guidobaldo), who spent many years in exile in Urbino, defended this city in vain against Cesare Borgia, 1513 after Genoa returned and took over the rule there as Doge , but eventually died in Ischia as a prisoner of the Marquis Fernando Francesco d'Avalos di Pescara - the husband of the famous poetess Vittoria Colonna .

- Federico Fregoso (* c. 1480 in Genoa, † 1541 in Gubbio), the brother of Ottaviano, fought as an admiral against the famous corsair Khair ad-Din Barbarossa off Tunis and off the island of Djerba , was later Archbishop of Salerno and Cardinal - and Close ties to Elisabetta as Bishop of Gubbio (1508–1541).

- Bernardo Accolti, called "l'Unico Aretino" (1465–1536), a well-known poet and courtier of his time, and last but not least:

- Baldassare Castiglione Count of Novilara himself, who was related to Elisabetta Gonzaga through his mother, Luigia Gonzaga, as a courtier , writer and diplomat , had been in the service of the Gonzaga in Mantua since 1499, was Mantuan envoy at the court of Urbino from 1504, there until Stayed in 1512 to join Francesco Maria I della Rovere and Elisabetta as ambassadors in Rome. He ended his career from 1527 to 1529 as papal nuncio (ambassador) to Emperor Charles V in Madrid , where he died.

It is noteworthy that the two most important social guides of the Renaissance, Il Principe (The Prince) by Niccolò Machiavelli - the guide to the unscrupulous development of power of the prince - and Il Libro del Cortegiano (The Book of the Hofmann) by Baldassare Castiglione - the guide for the exemplary Hofmann - almost at the same time - around 1510. Elisabetta Gonzaga experienced both theories firsthand: on the one hand as a victim of her “brother-in-law” Cesare Borgia, who served Machiavelli as the model of the ruler, and on the other hand as the heroine of her cousin Castiglione, to whom she served as a model of a refined court culture.

Both works were "bestsellers" of their time and quickly found acceptance at European courts. "Der Hofmann" was already available in Spanish in 1534, in French in 1538 and in English in 1552. A German translation appeared in 1565. By 1600 there were no fewer than fifty-seven editions.

The great Italian poet Ludovico Ariosto (1474–1533) also honored Elisabetta Gonzaga by describing a pantheon of beautiful and famous women in his hero Rinaldo's castle in his main work, the verse epic Orlando furioso ( The maddening Roland ), where in addition to the statues of hers Sisters-in-law - Lucretia Borgia and Isabella d'Este also the one of Elisabetta Gonzaga.

marriage

Elisabetta Gonzaga married in Mantua on February 11, 1489 Guidobaldo I da Montefeltro (1472–1508), 2nd Duke of Urbino, Count of Montefeltro, Count of Massa Trabaria, Lord of Casteldurante a. Mercatello sul Metauro, as well as Lord and Papal Vicar of San Leo , Cantiano, Pergola , Sassocorvato, Lunano, Montelucco, Fossombrone , Macerata Feltria, Maiolo, Sartiano, Torricella, Libiano, Rocchi, Maiano, Caioletto, Monte Benedetto, Pereto, Scavolino, San Donato, Ungrigno, Pagno, Pennabilli, Maciano, Pietrarubbia, Monte Santa Maria etc. etc. etc. The couple had no children, whereby the Duchy of Urbino and the associated territories passed to their adoptive son Francesco Maria I della Rovere .

literature

- Maria Luisa Mariotti Masi: Elisabetta Gonzaga Duchessa di Urbino nello splendore e negli intrighi del Rinascimento . Grupo Ugo Mursia Editore, Milano 1983, ISBN 88-425-1977-4

- Kate Simon: The Gonzaga - A ruling family of the Renaissance . Translated from the American by Evelyn Voss. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1991.

- Giuseppe Coniglio: I Gonzaga . dall'Oglio, editore, 1967

- Conte Pompeo Litta: Famiglie Celebri Italiane . Milano 1834.

- Volker Reinhardt (Ed.): The great families of Italy (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 485). Kröner, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-520-48501-X .

- Casimir von Chledowski: The court of Ferrara . Georg Müller Verlag, Munich 1919

- David Englander: Culture and Belief in Europe, 1450–1600: An Anthology of Sources . Blackwell Publishing, 1990, ISBN 0-631-16991-1

Web links

- Elizabetta Gonzaga at the Brooklyn Museum 'Dinner Party' database of notable women.

- genealogy.euweb.cz

Individual evidence

- ↑ Blasonnement: d'argent, à la croix pattée de gueules cantonnée de quatre aigles de sable au vol abaissé; sur le tout écartelé, au premier et au quatrième de gueules au lion à la queue fourchée d'argent armé et lampassé d'or, couronné et colleté du même, au deuxième et au troisième fascé d'or et de sable

- ↑ See Brooklyn Museum

- ↑ David Englander, p. 77, footnote.

- ↑ Detlev Schwennike: European family tables , new series. Verlag JA Stargardt, Marburg 1980, Volume I, Plate 84

- ↑ Kate Simon: "The Gonzaga" - A ruling family of the Renaissance . Translation from the American. Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 1991, ISBN 3-462-02110-9 , p. 71

- ^ Maria Luisa Mariotti Masi: Elisabetta Gonzaga Duchessa di Urbino nello splendore e negli intrighi del Rinascimento . Grupo Ugo Mursia Editore, Milano 1983, ISBN 88-425-1977-4

- ↑ Wilhelmo Braghinolli, Luca Fancelli, scultore, architetto e idraulico del secolo XV, Milano 1876

- ↑ Wilhelmo Braghinolli, Luca Fancelli in Archivio Storico Lombardo, Anno III, pp 611-628.

- ^ Giuseppe Coniglio: I Gonzaga . dall'Oglio, editore, 1967

- ↑ genealogy.euweb.cz

- ↑ Beverly Loise Brown: The image art at the courts of Italy . In: Faces of the Renaissance - masterpieces of Italian portrait art . Hirmerverlag, Germany, ISBN 978-3-7774-3581-7 , p. 45

- ↑ Kate Simon. Op. cit. P. 228

- ↑ [http.//www.genealogy.euweb cz / gonzaga / gonzaga2html # G1]

- ↑ Kate Simon. Op. cit. P. 101

- ↑ Ferdinand Gregorovius op. Cit. P. 60

- ↑ Kate Simon. Op. cit. P. 171

- ^ F. Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia (translation from German). Successori le Monnier, Firenze 1874, in the appendix Document No. XX, p. 350

- ↑ Kate Simon. Op. cit. P. 172

- ^ Giuseppe Coniglio: I Gonzaga , from the series "Grandi famiglie". dall'Oglio, editore, 1967, p. 174

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: Lucretia Borgia and their time . Wunderkammer Verlag, Neu-Isenburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-941245-04-4 , p. 220

- ↑ Casimir von Chledowski: The court of Ferrara . Georg Müller Verlag, Munich 1919, p. 174

- ^ F. Gregorovius: Lucrezia Borgia (translation from German). Successori le Monnier, Firenze 1874, p. 223

- ↑ Casimir von Chledowski: The court of Ferrara . Georg Müller Verlag, Munich 1919, pp. 181/182

- ↑ Maria Luisa Mariotti Masi: op.Cit. P. 168.

- ↑ Maria Luisa Mariotti Masi: op.Cit. P. 170.

- ↑ a b c d e Kate Simon. Op. cit. P. 173

- ↑ Maria Luisa Mariotti Masi: op.Cit. P. 172.

- ↑ Maria Luisa Mariotti Masi: op.Cit. P. 175.

- ↑ Maria Luisa Mariotti Masi: op.Cit. S 179/80

- ↑ Giuseppe Coniglio op.Cit. P. 178

- ↑ Maria Luisa Mariotti Masi: op.Cit. P. 188.

- ↑ Kate Simon. Op. cit. P. 175

- ↑ See Cambridge Companion to Raphael page 29

- ↑ a b c Maria Luisa Mariotti Masi: op.cit. P. 301.

- ↑ Maria Luisa Mariotti Masi op cit. P. 303

- ↑ Maria Luisa Mariotti Masi op cit. P. 307

- ^ Maria Luisa Mariotti Masi: op.cit. P. 311

- ^ Baldassar Castiglione "Il Libro del Cortegiano", Collana "Grandi classici della letteratura Italiana", Fabbri editori, 2001

- ↑ Ferdinand Gregorovius op. Cit. P. 281.

- ↑ Kate Simon; op. cit. P. 229.

- ↑ Casimir von Chledowski op. Cit. P. 217

- ↑ sardimpex.com

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gonzaga, Elisabetta |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Gonzaga da Montefeltro, Elisabetta |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Duchess of Urbino |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1471 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Mantua |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 31, 1526 |

| Place of death | Urbino |