Food culture in the Roman Empire

The food culture in the Roman Empire spans an epoch from the 6th century BC. BC to the 5th century AD and thus more than 1000 years. If you include the Eastern Roman Empire , you get over 2000 years. In the course of this long time the culinary customs changed considerably, first under the influence of Greek culture , then with the changing customs of the early royal era over the 500-year period of the republic up to the imperial era . In addition, the strong expansion of the Roman Empire and the incorporation of techniques and customs from the provinces influenced the food culture at times .

The food of the poor and that of the rulers differed little at first, then more and more over time and power increased. Their eating cultures were also very different.

Meals

Originally, breakfast was eaten in the morning , the ientaculum or iantaculum , in the afternoon the main meal of the day, the cena , and in the evening the vesperna .

Under the influence of Greek customs, but also due to the increasing use of imported goods, the cena became more lavish and was not taken until later in the afternoon. A second breakfast at early noon, the prandium , became common. The vesperna was omitted entirely.

In the lower classes , however, the old classification, which is more in line with the needs of physically active people, was retained.

Ientaculum (breakfast)

Originally, bread-like flat cakes made from spelled ( spelled ) were eaten with a little salt , and the wealthy also consumed eggs , cheese and honey . There was also milk and fruit . Moretum , a type of herbal quark , was also popular with bread .

Since the imperial era and the beginning of our era, there was bread made from wheat and, over time, increasingly diverse baked goods that replaced the simple flatbreads.

Prandium (lunch)

The prandium can also be viewed as a light lunch or a forked breakfast . Mostly cold dishes were eaten, such as ham, bread, olives, eggs, nuts, figs, mushrooms, cheese, fruits (dates). The prandium was more extensive than the actual breakfast, but was not of central importance to the Romans. The cena was much more important .

Cena (dinner / main meal)

In the upper class, who did not work physically, it became customary to complete all of the day's duties in the course of the morning. After the prandium , the last city errands were completed, then came the visit to the pool , and the cena started around 4 p.m. This meal often dragged on for a long time. Often a comissatio , a drinking binge, was celebrated afterwards .

In the royal times and early republic , but also later for the working classes, the cena essentially consisted of a cereal porridge , the puls (or pulmentum ). The simplest version consisted of spelled (spelled), water, salt and fat , a little more noble with oil , with maybe some vegetables . The wealthy ate their puls with eggs, cheese, and honey. Meat or fish was only added occasionally . The polenta can be seen as a descendant .

Over the course of the Republican era, the cena developed into a two-part meal consisting of a main course and a dessert with fruit and seafood . Towards the end of the republic, it was then common to divide it into three parts: starter , main course and dessert.

Even into the late Middle Ages, cena was used to describe dinner or supper. In Spain and Italy, dinner is still called a cena.

Table culture

From approx. 350 BC BC Greek customs had strongly influenced the culture of the wealthy Romans. Growing wealth also led to increasingly extensive and refined meals. The actual food was not in the foreground, on the contrary, the less nutrient-poor the dishes were, according to the opinion of the time, the more suitable they seemed to the gourmets of their time. Great importance was also attached to good digestibility and even a laxative effect.

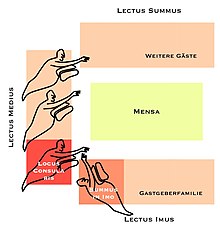

Comfortable clothes , the vestis cenatoria , were worn at the table , and meals were served in a special dining room , later called the triclinium . Here you lay at the table on a special dining sofa , the lectus triclinaris . Around the table, the canteen , three of these lecti were set up in a horseshoe shape , and a maximum of three people, before the imperial era only men, could lie per lectus . The heads were turned towards the table, the left elbow rested on a pillow and the feet were on the outside of the dining sofa. In this way a maximum of nine people could eat together at one table. The decent lady of the house or other guests as well as the entourage had to sit on chairs, slaves often even had to stand all the time. Semicircular dining sofas, called stibadium , were first used outdoors. In late antiquity , these were also used indoors.

Feet and hands were washed in front of the cena . One ate with the fingertips as well as two types of spoons , the larger ligula and the smaller cochlear with its needle-shaped handle, which also served as a skewer when eating snails and mussels , thus replacing today's fork. At the table larger pieces were cut up by a trancheur , and the smaller pieces were then taken from bowls ( acetabula and catilli ) and from plates ( catini ). After each course the fingers were washed again. Also were napkins , mappae called common than Mundtuch. Own mappae were also brought with them, in which food and small gifts, the apophoreta , could be taken home.

Musicians , acrobats and reciters performed during a banquet . The table discussions also played a major role. The topic of such a conversation could be stimulated, for example, by the decorations on the dishes used. There was rather no dance , it was considered incompatible with the fine table manners, although this was probably violated more often in the course of a comissatio . Getting up from the dining sofa, even if only to the toilet , contradicted the table manners of the time, and observance was considered a polite art. Only a small minority of the upper class sometimes used emetics to avoid the unpleasant after-effects of the mostly extensive dining. After the main meal , sacrifices were made to the lares , the household gods, during a break . This offering usually consisted of a meat, a cake and a wine offering. The cake was mostly colored with saffron .

typical dishes

Information about different dishes and the necessary ingredients are provided by ancient written sources such as the recipe collection of Apicius, but also archaeological finds of animal bones as slaughterhouse waste and vegetable remains of edible crops. Images of dishes from Roman times have also come down to us.

On the other hand, food from then unknown parts of the world could of course not be used in Roman cuisine. For example, potatoes , tomatoes , peppers , chilli , corn , turkey , chocolate and many more were unknown to the Romans .

starter

For gustatio , also known as promulsis , there were light, appetizing dishes, with mulsum , a wine and honey mixture, being drunk. Eggs, mostly chicken eggs, sometimes also from duck, goose and rarely even from peacocks , played an essential role, as did vegetables and salads .

Usual plants for vegetables and lettuce were

- Legumes such as broad beans , chickpeas , peas, and lupins , which were mainly popular with farmers, blacksmiths, legionaries, and gladiators ; Only lentils imported from Egypt were also popular with gourmets. Garden beans as we know them today come from America and were not known then.

- Types of cabbage were often taken with vinegar , kale was cooked in saltpeter . From Mangold both the green were blade parts eaten and the thick white midrib.

- Many shrub and herb leaves , such as elder , mallow , melde , fenugreek , nettle and sorrel , were cooked to puree and eaten with strong spices .

- Sour pickled fruits and vegetables such as olives , leeks , onions , cucumbers , melons , caper sprouts and cress were called acetaria and were considered to be appetizing.

Mushrooms were also eaten as additional ingredients in starters , especially Kaiserschwamm , boletus , mushroom and truffle . Braised and salted snails , raw or cooked mussels , sea urchins and small fish were eaten. After the end of the Republic of smaller light meat dishes were served, such as the dormouse , which in special enclosures, the gliraria , bred and finally ready for slaughter in dark pottery fattened were. Smaller birds such as the fieldfare were also fattened and then offered boned and stuffed.

In the case of extensive banquets, several starter courses were usually served one after the other.

Components of the main course

In front of the mensa prima , also known as caput cenae , an intermediate course could be served, although the decoration was often more important than the actual components.

Meat dishes were served:

- Beef was unpopular in upscale kitchens because beef was a workhorse with tough, hard meat that was only edible after long cooking. Few dishes even come down to us from the calf . However, beef was apparently eaten frequently, as evidenced by the abundance of slaughterhouse waste from cattle found during archaeological excavations in Roman settlements.

- In contrast, the pig was extremely popular. All parts were consumed, whereby for today's taste rather unusual pieces such as udders or wombs of young sows that had just given birth were considered a delicacy. Wild boars have already been bred and also fattened before slaughter .

- Geese were bred and partly fattened, and geese stuffing had already been developed. The goose foie gras was particularly popular and valuable .

- Other poultry were also common. Chicken was more expensive than duck . For gourmets, capons and poulards , which were very popular, were fattened, which was also reflected in the ban on eating poulards by the consul C. Fannius in 161 BC. Chr. Nothing changed.

- Sausages , farcimen , were made from beef and pork according to a wide variety of recipes. The simple botulus , a blood sausage that was sold on the street, was particularly widespread . The most popular type of sausage was lucanica , a richly seasoned and smoked pork sausage. Similar recipes are used e.g. Some of them are still used today. Allegedly, the Portuguese linguiça can be traced back to the Roman sausage.

- For a special effect, whole pigs were stuffed with sausages and fruit, grilled in one piece, then served standing up and cut open, causing the sausages to bulge out like intestines. One such pig was called porcus Troianus (Trojan Pig).

- Hares and rabbits were bred, but the former with less success, which is why a hare was four times as expensive as a rabbit. A rabbit was considered a luxury food, and the shoulder was considered particularly noble.

Fish were only served late , and they remained more expensive than the simpler types of meat. In fresh and salt water ponds which was fish breeding attempts, but some fish could not be fattened in captivity. One of the most popular of these was the mullus , the red mullet . At times it was considered the epitome of luxury, but above all because its scales turn bright red when they die. This is why these fish were sometimes slowly killed at the table, there is even a recipe where this is done in garum , i.e. in the sauce. With the beginning of the imperial era, however, this suddenly fell out of fashion, which is why the mullus could be shown in the feast of the Trimalchio as a mark of an upstart who bores his guests with the old-fashioned presentation of dying fish.

There were no side dishes in the modern sense, but bread has been consumed in all classes since the appearance of wheat . Only the poorest, who did not have access to an oven, had to continue to eat pulse . The bread quickly became extremely popular, the variety was great, and from 270 AD there were public bakeries in Rome.

To everyone and everything was as sauce component which garum , also liquamen called eaten. This was a sauce made from salted fish, especially mackerel innards , in a lengthy thermal process. In the course of two to three months, the protein-containing fish components were enzymatically dissolved almost completely by the heat of the sun . The brine was sieved, the liquid traded as garum and the residue under the name of alec . The production of garum was forbidden due to the odor development in the city. Sealed in small amphorae , garum was shipped across the empire and completely replaced the salt inland. Today a similar fish sauce is still used in Thailand and Vietnam .

Spices , especially pepper , but also hundreds of other types, were largely imported and used extensively. Another very popular spice was the silphium ; since it could not be grown, it eventually died out due to over-harvesting of the wild stocks. The natural taste of vegetables or meat was completely masked with garum and rich seasoning. It was considered the pinnacle of culinary art when gourmets could not guess the ingredients based on their appearance, smell or taste.

Desserts ( mensa secunda )

When it comes to fruit, grapes were particularly popular , although in the Roman Empire a distinction was made between wine and table grapes and raisins were made. In addition, figs and dates played an important role, pomegranates were eaten in many varieties, quinces , various apple varieties and apricots were bred.

The cold mussels and oysters, which were originally also served as desserts, gradually became part of the starters. Mussels have been grown on a large scale.

Cakes then played a bigger role, mostly honey-soaked and made from wheat. There were also some kinds of nuts , especially walnuts and hazelnuts or legumes, which were thrown at popular amusements like sweets today.

Pliny the Elder (23 to 79 AD) reports in his natural history that the caterpillar of a butterfly called Cossus ( willow borer ) was eaten in Roman times. Beetle larvae bred on flour and wine were also considered a popular delicacy among the Roman nobility.

Drinks and drinking habits

Except for water , which has existed since about 300 BC. Was to be had in good quality everywhere in Rome and that was drunk warm or snow-cooled, there was mulsum , a mixture of wine and honey, as well as wine itself, which was usually drunk diluted with water. The wine was often very strongly adulterated, so there were recipes on how to make white wine from red wine and vice versa. There was also a forerunner of mulled wine, conditum paradoxum , a mixture of wine, honey, pepper , bay leaf , dates , mastic and saffron , which was drunk hot, possibly boiled several times or also cold.

The most famous non-alcoholic drink of the Roman citizens and especially the legionaries was the posca . It was vinegar water .

But there was also - as a sign of absolute luxury - ice-cold wine. For this you needed a so-called snow cellar . Here, a considerable amount of snow was compressed and stored in large pits. Grass, straw, earth and linen cloths were used as insulating materials. The pressure partially turned the snow into ice . Even in the hot season, snow was brought to Rome from the mountains on pack animals. This effort ensured that the ice water was more expensive than the wine itself (Weeber, p. 26).

At a comissatio , a drinking king was always chosen who was allowed to determine the mixing ratio of water and wine as well as the amount to be drunk by everyone present. He could also request poems and other lectures from the participants . During the table, drinking vessels could be passed around and toasts made. By giving the vessel to a specific person, it was possible to express one's special appreciation.

Beautiful young cupbearers mixed the drinks and brought them to the guests. These wore wreaths, originally probably to protect them from headaches and other negative effects of the copious consumption of alcohol, later also simply as jewelry.

Food procurement

The feeding of Rome was a great organizational effort, which required numerous administrative staff.

Rome did not mainly use the surrounding area for food production, but imported the food of its inhabitants to a large extent from other countries. For example, cereals were sometimes grown, harvested, processed and sold in their own country, while the already known cultivation of the Roman-Greek culture was used and improved. How productive the harvest was, depended on the fertility of the soil and the climate of the growing area. However, the surrounding land was by no means enough to feed a million citizens, so grain was imported from Egypt, North Africa and Sicily.

Furthermore, the food supply was not always guaranteed because it was susceptible to robbery. Attempts were also made to keep transport routes short, as transport was expensive and slow.

Diet in the Army

A Roman soldier's menu depended on whether he was on a campaign or, as most of the time, in a garrison. In the fixed military camps, due to the functioning organization of the army, the supply of food was generally comparatively good and varied. It can be proven in various contexts that the staple food was supplemented with meat or fish, for example. In the Argentovaria army camp in what is now Alsace, numerous foods can be archaeobotanically proven due to the high level of soil moisture ; These included locally grown nuts, fruits, vegetables and herbs as well as imported products such as pomegranates and olives. However, the basis of the diet seems to have been bread, which was mainly made from millet, barley, spelled and wheat. Scientific studies have also made it clear that the foods often show deficiencies such as pests and parasites. Among the drinks, Posca was particularly important, a mixture of water and vinegar that was widely used as a cheap and refreshing alternative to wine in the Roman Empire.

For higher posts like centurions a clearly higher standard of nutrition was recognizable than for common soldiers. In general, the composition and quality of the food served by Roman soldiers also strongly depended on geographic factors such as the climate and natural conditions of the place of deployment, the distance to Rome and the long-distance trade routes and the quality of the local infrastructure. However, complaints about nutrition in the army are not recorded in the ancient sources. General campaigns represented a special case, on which food shortages could also prevail due to the special circumstances.

At least part of the soldiers' food was taken care of by the administration of their respective troops, for which part of the wages was withheld. Whether the annona militaris , the supply of the army, was already centralized under the Praefectus annonae at the beginning of the Roman Empire , or whether it was organized decentrally by the troop commanders and governors, is the subject of an intensive research debate.

Hunger in the Roman Empire

Hunger in the Roman Empire was omnipresent and, in case of doubt, could even ensure that the Roman Empire could not wage wars, as there was not enough food to supply the army.

Furthermore, hunger increased the dissatisfaction of the Roman population, which could ultimately lead to greater uprisings being mobilized.

In order to counteract this, the goals of the Romans were rationalized: some groups of the population were temporarily expelled from Rome in order to ensure that the Romans were fed. These populations included gladiators, slaves, and strangers.

There was constant struggle for survival in the lower classes. This can be determined, for example, on the basis of the average grain consumption with the measured values of modern times: 50 liters of grain per month would correspond to a nutritional value of between 3000 and 5000 kilocalories per day for medium-heavy activities and would therefore meet the current expectations of adequate nutrition.

Ancient sources, on the other hand, report that the average consumption of grain was between 27 and 45 liters, which, based on the calorie consumption alone, reflects an inadequate to sober amount of calories per day.

swell

- Apicius: De re coquinaria . About the culinary art. Lat./Dt. Ed., Trans. and commented by Robert Maier. Reclam, Stuttgart 1991. ISBN 3-15-008710-4 .

- Apicius: The Romans' cookbook, a selection peppered with literary delicacies. De re coquinaria. Translated by Elisabeth Alföldi-Rosenbaum . Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf 1999. ISBN 3-538-07094-6 .

-

Petronius : Cena Trimalchionis. Banquet at Trimalchio. Lat./Dt. dtv, (Ed. K. Müller / W. Ehlers) Munich 2nd edition 1978. ISBN 3-423-09148-7 .

(The satirical portrayal of eating in the house of a nouveau riche from the Roman Empire) - Marcus Porcius Cato : From agriculture - fragments. De agri cultura. Lat./Dt. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf 2000. ISBN 3-7608-1723-8 .

literature

-

Siegfried Lauffer (Ed.): Diokletian's price edict. Vol VIII. De Gruyter, Berlin 1971.

(Information on the relative value of various foods and everyday goods) - Andrew Dalby , Sally Grainger: Kitchen Secrets of Antiquity . Stürtz, Würzburg 1996. ISBN 3-8003-0672-7 .

- Jacques André: Eating and Drinking in Ancient Rome. Reclam, Stuttgart 2013. ISBN 978-3-15-010922-9 .

- Ulrich Fellmeth : Bread and Politics. Food, table luxury and hunger in ancient Rome. Metzler, Stuttgart 2001. ISBN 3-476-01806-7 .

- Gudrun Gerlach: At table with the ancient Romans. Theiss, Stuttgart 2001. ISBN 3-8062-1353-4 .

- Hans P. von Peschke, Werner Feldmann: Cookbook of the Romans. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2003. ISBN 3-491-96075-4 .

- Elke Stein-Hölkeskamp : The Roman banquet . Beck, Munich 2005. ISBN 3-406-52890-2 .

- Karl-Wilhelm Weeber : Luxury in ancient Rome. The indulgence, the sweet poison… Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2015. ISBN 978-3-8053-4868-3 .

- Frank Kolb : Ancient Rome: History and Archäelogie 2nd edition May 1st 2010. ISBN 978-3-406-53607-6

- Frank Kolb : The ancient Rome: History of the city in antiquity first published in 1995 ISBN 978-3-406-46988-6

- Michael Kuhn : The Taste of the World Empire - Introduction to Roman Cuisine. Ammianus-Verlag 2018, ISBN 978-3-945025-60-4

Web links

- Book tips and recipes to cook at home. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on October 6, 2007 ; Retrieved June 18, 2014 .

- Extensive presentation of Roman cuisine, meals, nutrition of the legions, grain, etc. v. m.

- Diocletian's price edict (all information received is in German, the weight and volume units are explained)

- The Latin text de agri cultura

- Comprehensive website on Greco-Roman nutrition, kitchen technology, the ancient triclinium and its equipment

- Table culture

- Table culture in antiquity, grain cultivation , grain trade (last visited on December 10, 2017)

- Nutrition in the Roman Empire (last visited on December 10, 2017)

- Roman food customs and early Christianity

Individual evidence

- ^ Bernhard Schnell et al. (Hrsg.): Vocabularius Ex quo: Tradition historical edition. Tübingen 1988-1989, C 317.

- ^ Hermann Grotefend : Pocket book of the calculation of the time of the German Middle Ages and the modern times. 10th ed., Ed. by Theodor Ulrich, Hannover 1960, p. 23.

- ↑ Desirée Bea Cimbollek, Ralf Krause, Thomas S. Linke: Try what is crawling there. The practical insect food guide. Berlin 2014 (eBook).

- ↑ To use drinking bowls.

- ^ Kolb, Frank .: The ancient Rome: History and archeology . Orig.-issued edition. Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-53607-6 , pp. 48 .

- ↑ M. Weiß: Grain cultivation and harvest in Roman-Greek antiquity. Retrieved December 13, 2017 .

- ↑ M. Weiß: Grain trade in Roman-Greek antiquity. Retrieved December 13, 2017 .

- ↑ Ingo Henneberg: www.die-roemer-online.de --- The forum all about the "Romans". Retrieved December 13, 2017 .

- ^ Gabriele Wesch-Klein : Social aspects of the Roman army in the imperial period (= Heidelberg ancient historical contributions and epigraphic studies . Volume 28). Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-515-07300-0 , p. 37 f. and p. 201.

- ↑ See Patricia Vandorpe: Plant macro remains from the 1st and 2nd Cent. AD in Roman Oedenburg / Biesheim-Kunheim (F). Methodological aspects and insights into local nutrition, agricultural practices, import and the natural environment. Dissertation, University of Basel 2010 ( online ).

- ↑ Danielle Gourevitch: Diet. In: Yann Le Bohec (Ed.): The Encyclopedia of the Roman Army. Volume 1, Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester 2015, p. 327 f.

- ^ Friedrich Wotke : Posca. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume XXII, 1, Stuttgart 1953, Col. 420 f.

- ↑ See for example WJ Kuijper, H. Turner: Diet of a Roman centurion at Alphen aan den Rijn, the Netherlands, in the first century AD. In: Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. Volume 73, Numbers 1-4, pp. 187-204 ( doi: 10.1016 / 0034-6667 (92) 90057-N ).

- ↑ Danielle Gourevitch: Diet. In: Yann Le Bohec (Ed.): The Encyclopedia of the Roman Army. Volume 1, Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester 2015, p. 327 f.

- ↑ Michael A. Speidel : Pay and economic situation of the Roman soldiers. In: The same: Army and rule in the Roman Empire of the High Imperial Era (= Mavors. Volume 16). Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-515-09364-4 , 407-437, here p. 417.

- ↑ The early existence of a central supply organization is mainly represented by José Remesal. On the other hand, for example Werner Eck : The praefectus annonae : A super minister in the Roman Empire? Army supply and praefectura annonae : not one major administration, but two separate administrative worlds. In: Xantener reports . Volume 14, 2006, pp. 49-57.

- ^ Kolb, Frank .: The ancient Rome: History and archeology . Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-53607-6 , pp. 69 .

- ^ Kolb, Frank .: Rome: the history of the city in antiquity . 2nd revised edition CH Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 978-3-406-46988-6 , p. 454 .

- ^ Kolb, Frank .: Rome: the history of the city in antiquity . 2nd revised edition No. 454 . CH Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 978-3-406-46988-6 .