Frauenkirche (Dresden, Gothic predecessor building)

The Gothic Frauenkirche in Dresden was the predecessor of the Frauenkirche by George Bähr . It was built in the 14th century and, despite its location outside the city walls, was considered the mother and main church of Dresden until the 16th century. The introduction of Protestantism in Saxony in 1539 marked a turning point in the history of the church. The service was stopped there and held exclusively in the Kreuzkirche . Services were not held again in the Frauenkirche until 1559, but opposite the more centrally located Kreuzkirche it had received the status of a village church for the poorer population.

Frauenkirche and Frauenkirchhof had a special meaning as burial places for the nobility and the upper middle class. This led to protests by the population when the dilapidated Frauenkirche was to be demolished at the beginning of the 18th century and its cemetery was to be secularized. Only when the church was in danger of collapsing could the plans for a new building under the direction of George Bähr be realized. The construction of the baroque Frauenkirche and the continued use of the Gothic church initially ran in parallel, before the old Frauenkirche had to be demolished in 1727 in order not to hinder construction progress.

Various pieces of equipment from the Gothic Frauenkirche have been preserved, including church vessels and the pulpit. A bell of the Gothic Frauenkirche still rings in the rebuilt Bährschen Frauenkirche. There, as well as in the Dresden Kreuzkirche and the city museum , gravestones and epitaphs from the Frauenkirche and the churchyard are on display.

history

prehistory

In 968 the diocese of Meissen was founded, which was subordinate to the archbishopric of Magdeburg . The missionary work of the Sorbs living in today's Saxon area began in Meissen . For this purpose, a church organization with numerous mission churches developed by the year 1000, mostly on the initiative of the bishops, but also the margraves. It is considered likely that a Meißner bishop founded the Frauenkirche in what was then Gau Nisan and also had the patronage of the church. At the beginning there were around 30 Sorbian villages on the right and left side of the Elbe, which were up to ten kilometers away from the church. With the Sorbian village settlement of Poppitz , the Frauenkirche has also had a dose of material equipment since its foundation .

As the Church of Our Lady, the Frauenkirche was dedicated to the veneration of the mother of Jesus Mary . Since churches used the Marian patronage throughout the Middle Ages, no reference to the founding time of the first Frauenkirche can be derived from it. The research assumes that the first Frauenkirche initially existed as a "mission station without a fixed Sprengel " and was located away from the center of the Burgward . In view of its missionary status, the first Frauenkirche must have been built at the end of the 10th or beginning of the 11th century. When the church ceiling was redesigned around 1580, an old year (probably 1020) was found for the “foundation” and the age was given as “in the 560th year”. A foundation of the church (around) 1020 therefore saw chroniclers of the 17th and 18th centuries as possible. According to Slavic tradition, the probably still wooden Frauenkirche was consecrated by Přibislav (probably the court chaplain of the Bohemian Duke Oldřich ) on September 8th, the feast day of the birth of Mary. The archaeologist Reinhard Spehr put the year of construction of the Frauenkirche at the time "around 1060"; His excavations in 1987 on the former Frauenkirchhof uncovered remains of graves, which presumably came from the 11th or early 12th century and suggest an older church belonging to it. Later excavations resulted in finds which were also dated to the end of the 10th century. Since there are no structural remains of the first Frauenkirche and the stone construction was still largely unknown at the time, the first Frauenkirche will have been a sacred wooden building.

In the course of the 12th century the Frauenkirche increased in wealth and importance and the surrounding settlements must have grown to such an extent that the plan for a stone church was put into practice. The wall foundations of this building that were exposed in 1987 consisted of plan slate laid in clay . Foundations made exclusively from plan slate were found in Dresden in the area of the city wall and date back to the last quarter of the 12th century. Small fragments found in the building clay of the plan walls, which can roughly be dated to the 12th century, point to the first stone Frauenkirche before 1170. It was probably built as a three-aisled basilica .

The first indirect mention of the Frauenkirche comes from the year 1240: Heinrich III. named the pastor of the parish of Dresden in his certificate for the Leipzig Katharinenkirche as a witness that year. The first direct written mention of the woman church dates from October 1, 1289, as abbot Heydolf from Klosterbergegarten before Magdeburg the Archdeacon Arnold of Nisan told in a document that he was "the priest Albert of Lobeda [...] as a priest in the [women ] Church in Dresden and its opponent Adolf imposed a ban on speaking in this church ”.

The patronage of the Frauenkirche changed several times until the 15th century. Heinrich III owned it until shortly before 1288 . ; then it passed to the Seusslitz monastery and was exchanged for the bishop of Meissen Withego II of Colditz in 1316 . In 1404, the Margrave of Meissen Wilhelm I acquired the patronage right over the Frauenkirche from Bishop Thimo von Colditz in exchange for the Kirchlehn Ebersbach and the Nikolaikirche in Freiberg .

The construction of the Frauenkirche in the 14th century

The new building of the Frauenkirche was built in the 14th century. It "was built around the Romanesque predecessor, so it surrounded it like a bell". It is uncertain whether a church consecration of the Frauenkirche dating back to 1388 refers to the consecration of the new building, but it is “not unlikely”, as excavation findings indicate a building from the late 14th century. The new building was a flat-roofed hall church with two side aisles. The basic shape of this nave , like that of the previous building, was almost square. An altar was donated to the church in 1395; minor alterations have been reported for 1452.

It is not known when the church received its sacristy extension. In 1468 stonemason Paul made a window and a keystone for the sacristy ; it received a new door and was probably vaulted in 1469. Whether this happened in the course of the construction of the sacristy cannot be clearly proven, even if the art historian Heinrich Magirius sees the work “in connection with the construction of a sacristy”.

From 1470 to 1483 the Frauenkirche was redesigned in the late Gothic style. From 1470 to 1472 the church and sacristy received roofs; at that time the church already had a turret. From 1477 to 1483 a long choir was added to the Frauenkirche , with which it reached a total length of 38 meters. The choir was soon popularly called “the high choir” and was vaulted. The art historian Cornelius Gurlitt suspected that the new late Gothic choir replaced an older one; Magirius also followed this view. However, there is no evidence of a previous choir. At the same time as the choir was built, the addition of a side chapel and possibly the construction of the sacristy will probably take place. On November 6, 1483, the new main altar was consecrated in the Frauenkirche, which was placed in the recently completed long choir.

In 1497 the Frauenkirche received a new roof turret , which Caspar Beyer made; two years later a new spindle on a gold button was installed on the tower. The Frauenkirche had the appearance that has been handed down in engravings from the 18th century, and with its central ridge turret and the hipped roofs gave the appearance of “a centralized building with a long choir attached to the east”.

The development in the 16th and 17th centuries

In 1539, the anti-Lutheran Saxon Duke George the Bearded died . His successor, the Lutheran-minded Heinrich , introduced Protestantism in Saxony that same year . This meant a significant turning point for the Frauenkirche. The Nikolaikirche was built not far from it in the 12th century and was consecrated as a cruciform church in 1388 . It had subsequently developed into a competitor for the status of the main church of the city of Dresden, was only rebuilt after a fire in 1499 and was located within the city walls. Nevertheless, the Frauenkirche, located outside the city walls, retained its status as mother and main church until the 16th century. This ended with the introduction of the Reformation in 1539. The service in the Frauenkirche was discontinued and held exclusively in the Kreuzkirche. Apparently the council of the city of Dresden assumed that the services could be held in a city church, regardless of the fact that at that time 26 surrounding villages were part of the Frauenkirche. The church decorations in the Frauenkirche were acquired by the Annaberg and later Dresden mint masters . The altars were removed and the bells melted down. The church was initially empty, but continued to serve as a burial place.

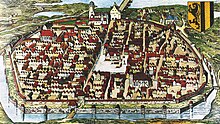

As early as 1520, Georg the Bearded had begun to build fortifications around the settlement with the Frauenkirche. However, the old city wall remained. It was not until 1546 that the construction of the Dresden fortifications began under Caspar Voigt von Wierandt , which was completed in 1556. The Frauenkirche was thereby optically integrated into the city of Dresden; the Neumarkt , which emerged in front of it towards the city center, developed into a place of lively construction activity. Not far from the Frauenkirche and its cemetery, the Mint (1556), the armory with its foundry and salt house (1559–1563) and the powder tower that shaped the townscape (1565) were built.

At that time, Dresden was a steadily growing city. By the 1550s at the latest, it became clear that the cruciform church was not large enough during church services to accommodate both the city population and the residents of the parish villages. The city council therefore decided to reopen the Frauenkirche for services. It had fallen into disrepair due to the lack of use since 1539 and therefore had to be refurbished from 1556: in 1556 the ceiling of the nave was torn down and replaced in the following year by a field ceiling , which was soon painted with biblical representations. The new two-story galleries in the nave were painted white and ash; the interior of the church was whitewashed and the stalls replaced. From 1556 to 1557, Hans Walther II created a new pulpit, which is considered a “top work of the Renaissance”. In 1556, Elector August donated three bells from the secularized Cistercian monastery of Altzella to the Frauenkirche . In 1559 the church received a new Steer organ and was finally opened to worship around Judica in the same year .

As the city church, the Frauenkirche was the place of worship for 26 parish villages in Dresden. Baptisms were only allowed in the Kreuzkirche, which had been the main church in Dresden since the Reformation. Funerals took place in the Frauenkirche and on the Frauenkirchhof. The latter had developed into a popular burial place for the bourgeoisie and the nobility after the construction of a total of 112 exclusive hereditary burial sites , so-called Schwibbögen, had been completed in 1565 .

Decay and demolition by 1727

The quarter around the Frauenkirche had already been upgraded in the 16th century with the addition of the stable yard and the Gewandhaus . At the beginning of the 18th century, the Neumarkt district continued to gain in importance, not least due to the lively construction activity of the nobility - Hôtel de Saxe (1709), Palais Brühl (1712), Palais Flemming-Sulkowski (1714). The exterior of the Frauenkirche had remained unchanged since the 15th century; the deterioration of the medieval structure could not be stopped by the 17th century at the latest. Since 1714, Friedrich August I also urged the secularization of the Frauenkirchhof, which was perceived as unsanitary, and to build a new, representative church in place of the dilapidated old Frauenkirche. Both the senior consistory and the citizens of Dresden, who had buried their dead here for generations, were opposed to the dissolution of the churchyard. On the instructions of the elector, the churchyard was closed in 1715 and reduced in size for the construction of a new regimental house.

Since 1722 at the latest, the Dresden City Council had to deal with plans for a new church. The clapper fell from the large women's church bell in 1721 and badly damaged the roof of the church. In addition, cracks had formed in the masonry. The condition of the church was so desolate that in 1722 the rib vault in the choir and the roof turret had to be removed. The bells were hung in a newly built interim bell tower north of the church.

For a new building, the ground first had to be created. The Frauenkirchhof was overcrowded with graves; there were also over 100 massive candle arches on the church and churchyard wall. In July 1724 henchmen began removing tombstones from the cemetery and breaking off the candle arches; this work continued until 1727. The senior consistory ordered that the citizens should arrange for their dead to be reburied. If this was not possible, the city council arranged for a relocation to the Johanniskirchhof .

In January 1725 the Frauenkirche, which was still used for church services, threatened to collapse. The cracks in the masonry had increased significantly since 1721. By May 1725, scaffolding and wooden supports were built inside; At the same time, the outer walls were strengthened by supports that were attached to houses opposite, despite residents' protests. From 1725, the Frauenkirchhof served as a storage facility for building materials for the new church.

The floor work for the new Frauenkirche began between the Maternihospital and the long choir of the Frauenkirche, which could continue to be used for church services. The official start of construction for the new Frauenkirche was July 3, 1726; the foundation stone was laid on August 26, 1726 and was accompanied by a service in the old Frauenkirche. It was not until the end of 1726 that construction work on the new church had progressed so far that the old church prevented further construction. Construction clerk Oderich, master builder Johann Gottfried Fehre and George Bähr reported to the city council that the demolition of the old church had to begin, “since all the basic lines [of the new building] go through the nave and main walls of the old church. ". The city council in turn sent a request to Elector Friedrich August I on December 14, 1726 that the old church building had to be torn down by spring 1727 in order not to endanger the further construction of the new church. With the approval followed the instruction of the elector to relocate the service from the old Frauenkirche to the Sophienkirche .

On February 9, 1727, the last service was held in the old Frauenkirche. On February 15, 1727 the demolition of the church officially began. The organ and the stalls were removed and the main altar was moved to the Church of St. Anne . At the time there were still so many grave monuments on the outer wall of the church that the transport bills from February 1727 recorded “30 loads of epitaph from the church in front of the Wilsdruffer Thor ”. By the end of April 1727 the church was covered and demolished. Only the west wall and the immediately adjoining church courtyard wall were initially retained “probably as a demarcation and protection for the construction site”. They were finally dismantled in August - the demolition of the old Frauenkirche was thus complete, down to the foundations.

Today's Frauenkirche takes up the choir of the old Frauenkirche. The nave of the old church is not built over. The marking of the well of the Maternihospital with a copper plate embedded in the pavement allows an orientation in interaction with the current church building, where the old church was.

Building description

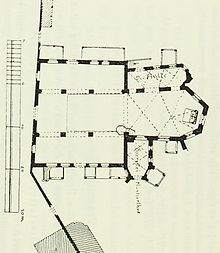

The nave of the old woman was church with an outer width of 25.40 meters and a length of 23 meters larger than the Roman predecessor. Traditional floor plans show that the surrounding walls of the nave were not parallel but shifted.

At a later time, a long choir was added to the nave, which was the width of the central nave. It ended in three sides of the octagon. To the north of the choir there was a side chapel, which, like the choir, closed off polygonally ; south of the choir, following the aisle of the nave, there was a two-story extension, which also ended in a polygonal manner. It served as a sacristy.

The roofs of the church were unusual: the ridge of the high nave roof did not run in a west-east direction, as was common in medieval churches, but in a south-north direction. The roof ridges of the choir and sacristy were lower than that of the nave, whereby the saddle roof of the choir did not connect to the hip of the nave, but to a hip running transversely to the main roof, which was lower than that of the nave, but significantly higher than that of the auxiliary buildings. It can be assumed that the roof turret sat in the middle of the ridge of the nave roof, so the “additional roof” must have been located to the south, i.e. neither in direct connection with the choir axis nor in direct connection with the south aisle. Magirius suspected that the roof covered part of the sacristy extension or the long choir, but described the roof representation, which has been handed down several times, as "strange" and "strange".

The longhouse

Cornelius Gurlitt wrote in 1902 that the nave was "probably of Romanesque origin"; Only excavations from 1987 revealed that the church was built in the 14th century around the foundation walls of the Romanesque predecessor building.

The interior of the three-aisled nave was 23 meters wide and 20 meters long. Both side aisles were separated from the main nave by three arcade arches each, which stood on two pillars . At the western and eastern ends, the arcades rested on templates . The pillars were rectangular according to the traditional ground plan. However, half a workpiece of an octagonal pillar has been preserved, so that the floor plan drawings may only show the base shape of the pillar. Such pillar formations have been handed down in Saxony from around 1400, for example in the Jakobikirche in Chemnitz and the Frauenkirche in Meißen .

The interior of the nave was not vaulted, and since there were no buttresses, no vaulting was planned. Instead , the nave was given a field ceiling in 1557 , which was painted and had columns through which worshipers could follow the service even in the attic if it was overcrowded.

The nave was lit in the south by five basket-arched windows , which Magirius estimated as post-medieval. In the north there were three stylistically identical windows. The nave was accessed via three portals: on the south side of the church a pointed arch portal led from the churchyard into the main building, there was another gate on the north side of the church and a third one from the western side of the street.

To the northwest of the hall church was a staircase. Little is known about the side chapel, which adjoined the north aisle to the east, especially since a pictorial representation of the north side of the church and the traditional floor plans of the building contradict one another. Magirius suspected that the side chapel "should have been hardly older than the late Gothic long choir".

The long choir

To the east of the hall church there was a late Gothic choir, which was as wide as the nave. Its construction began in 1477, according to an inscription on the choir, and was completed in 1483. Before 1596 the choir was vaulted and painted. It was 15 meters long, so that the church got a total length of around 38 meters. The basic form of the choir was irregular according to Bähr's drawings, but regular with Johann Gottfried Michaelis . Gurlitt estimated that the Bährian representation might be more correct .

Gurlitt speculated that the new choir replaced an older choir system. With regard to the unusual additional roof between the main roof and the choir roof, Magirius pointed out that the long choir may have been attached to an older and significantly shorter choir. According to traditional building bills, the roof structure was built in 1472, so that an older choir is not unlikely.

The long choir had three-lane pointed arch windows. It was entered from the churchyard through a small pointed arch portal on the south side; The entrance to the sacristy was also on the south side, but further west than the entrance from the churchyard. At this point was the pulpit, which could be entered directly from the sacristy via a staircase. The main altar of the church was placed in the long choir.

Various workpieces from the late Gothic choir were reused for the new Bähr building and recovered when the Frauenkirche was cleared in 1993.

The sacristy extension

The sacristy annex was on the east side of the south aisle and the south side of the choir. It had two floors. On the first floor, as in the rest of the church, there were tombs and the church regalia was stored here. The first floor was used by funeral societies and guilds to store the shrouds and equipment.

It is said that the sacristy received a new door in 1468. It is uncertain whether the so-called “coin gate” was the sacristy door or the large long house gate on the south side. The mint gate was donated by the electoral mint society and bore their coat of arms. The Münzergesellschaft had also been given a burial place at the sacristy and donated a larger than life stone crucifix to the church, which was attached to a pillar of the sacristy building. Three parts of the body of the Christ figure were found in 1994 when the Frauenkirche was cleared.

In 1468 stonemason Paul made a new window and a keystone for the sacristy. The following year it was domed by a Master Thomas. Master Claus made larger vaults probably for the sacristy in 1470.

A master Claus worked for the bishops of Meissen in the 1480s and 1490s, including at Albrechtsburg . The assumption of an identity between this master Claus and the master builder employed at the Frauenkirche is “tempting” for Magirius. The upper floor windows of the extension had curtain arches and the buttresses of the extension had curved covers. Magirius saw in it elements "which reveal a stylistic origin from the area around the Albrechtsburg Arnold von Westfalen , a building that had been in progress since 1471." A stylistic dependence of the sacristy on the Albrechtsburg would mean that the sacristy was not built earlier than 1471 can. Magirius therefore suspected that the sacristy, which has been handed down in sources from the 1460s, was an older, more modest building that is connected to the additional roof in the west of the long choir. He dated the possible successor building to "around 1500" and thus as younger than the long choir. This has no stylistic similarities with the sacristy, which can be explained by the earlier date of origin.

The sacristy was renewed in 1703: the windows were enlarged and a new door to the churchyard "to make those clergy more comfortable" was broken out.

Furnishing

Altars

In 1366 Hans Münzmeister donated a Michaelis altar to the church, which received renewed dedications in 1395 and 1459. Another altar is mentioned for 1394, which was consecrated to the Trinity. In 1395 Margrave Wilhelm von Meißen furnished an altar which was consecrated to the apostles Philip and James "and all twelve messengers". At that time the Frauenkirche had seven altars, including one in the chapel of the "charnel house" on the Frauenkirchhof. A new main altar of the church dates from 1483, the altar consecration took place on November 6th 1483 by Auxiliary Bishop Andreas von Cerigo . The existence of another altar of the church, also consecrated by Andreas von Cerigo, is recorded for the year 1489. It may have been placed in the side chapel.

The last main altar in the church was donated in 1584 by the brothers Heinrich and Adolf von Krosigk. He was also the epitaph for her brother, Court Marshal Hans Georg, who died in 1581. The altar was made of white Pirna sandstone and, next to the memorial for the dead, bore the inscription: “With divine grace to our Lord Christ Himmelfarth in 1584, this altar was made by me, Christoph Walther von Breslaw , sculptor and borrower here, his age 50 years. "

In the lower area of the altar there was a depiction of the Lord's Supper, side reliefs of the birth and resurrection of Christ and above that a crucifixion scene. The Last Judgment was presented. The altar was completed by a representation of the Holy Spirit as a dove, flanked by angels. The representations were accompanied by verses from the Bible. Michaelis stated in 1714: "All of this is clean and artificially hewn / just as the scriptures and sayings are carved on it".

When the old Frauenkirche was demolished in 1727, the altar was moved to the Annenkirche in the same year . The main altarpiece had probably been replaced by a pulpit at the time. Baroque figures and reliefs were also added. After the fire in the Annenkirche in 1760, the altar is no longer recorded in the files of the Annenkirche and it is not known when the altar was moved from the Annenkirche. However, after 1760 it was re-installed in the Matthäuskirche in Friedrichstadt , although it was only partially preserved: only columns, consoles, the entablature on the upper floor and the cranked main cornice with lions' heads and tendrils in the frieze remained from the original Frauenkirchen altar. The altar was about 820 centimeters high due to a newly placed halo; a height of 734 centimeters has been handed down for the original altar. In 1882 the altar was changed again.

When Dresden was bombed in February 1945, the Matthäuskirche was badly damaged. The altar, which was also damaged, was finally demolished in the post-war period.

pulpit

In 1556 and 1557, Hans Walther II created the pulpit of the Frauenkirche, which was painted by Augustus Cordus . The wooden sound cover of the pulpit had not been preserved as early as 1714. At that time Michaelis wrote that the pulpit cover of the church was made of stone, but was "replaced by a new ceiling by Holtz and sculptor work / on which on top the image of the suns / along with other decorations / below on the same ceiling salvation. Spirit can be seen in the form of a dove / is also white and gold ground. "

The pulpit was located on the southern triumphal arch between the nave and the choir and was accessible from the sacristy via a stone staircase. A life-size alabaster crucifix hung over the pulpit entrance .

A description of the Frauenkirch pulpit has been handed down from 1714:

"Next, the Cantzel, built of white Pirnic stones / with beautiful carved and ground Biblical histories / as there is first of all the tree of knowledge / around which the snake is wound / worbeyed a small table: God created man for eternal life." Then Adam and Eve between them the dead, behind them the angel with the bare sword, darbey: Through the envy of the devil, death came into the world, Sap. 2. Then / Christ at Creutz on one side the baptism of Christ at the Jordan, with the inscription: This is my dear son etc. on the other John pointing to Christ: Darbey these words: See, this is God's Lamb etc. The whole Werck rests on a statue of an angel carved out of solid stone / who holds a tablet in his right hand / on it one reads: Blessed are those who hear God's word and keep it. "

The art historian Walter Hentschel , who had dealt intensively with the Walther family of sculptors , stated in 1966 that the pulpit of the Bischofswerda Cross Church "is most likely identical to the pulpit of the old Dresden Frauenkirche created by Hans Walther in 1556" and remarked elsewhere that that "the identity [of both pulpits] can hardly be doubted". Magirius agreed with Hentschel's opinion in 2002 and described the identity of both pulpits as "very likely". Gurlitt saw a stylistic similarity between the pulpit and works by Hans Walther.

The pulpit of the Frauenkirche was dismantled when the church was demolished in 1727 and initially stored in one of the buttress arches of the old Annenkirchhof . The pulpit of the Kreuzkirche came from the castle chapel in Stolpen to Bischofswerda in 1814 . A relocation of the Frauenkirch pulpit to the Stolpen Castle Chapel has not been proven, but is possible.

Gurlitt wrote that the Bischofswerda pulpit "[belongs] to the expansion of Stolpen Castle under Elector August". Hentschel also emphasized that the Bischofswerda pulpit was built in the middle of the 16th century. Unlike Gurlitt, however, Hentschel considered it "unlikely that the not very large castle chapel had such a stately pulpit, the rich plastic ornamentation of which would not have corresponded to the thrifty spirit of Elector August".

The Bischofswerda pulpit differs in three details from the description in Michaelis: On the right edge it has a relief with the resurrection of Christ, which Michaelis does not name. Hentschel suspected that the representation in the Frauenkirche was covered by the council gallery next to it. The baptism of Christ described in Michaelis is missing on the Bischofswerda pulpit; the angel carrying the Bischofswerda pulpit does not carry a tablet, but an open book. It cannot be ruled out that the pulpit was redesigned at a later date. Since it is recorded that Elector August should have donated a pulpit to the Stolpen Palace Chapel in 1567, an identity of the Bischofswerda pulpit with the Stolpen pulpit cannot be ruled out; this would at least be a close copy of the Frauenkirch pulpit.

organ

From 1557 to 1559, Master Lorentz Steer made an organ for 245 guilders . It was repaired by Jeorge Kretzmar in 1568. In 1622 the church received a new organ from Tobias Weller , which he had built from 1619. It was probably on the west gallery. The cost was 1000 guilders. The organ front was probably painted by Sigismund Bergk and in 1714 showed the birth of Jesus and the adoration of the kings on the inside "very clean and large". In 1653 Weller expanded the organ, which was renovated in 1680 by court organ maker Andreas Tamitius . In 1711, court organ maker Johann Heinrich Gräber re- leathered the wind chests .

Disposition of the Frauenkirchen organ in 1714:

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Secondary register: Zimbelstern , tremulant , pedal coupler , manual coupler

Remarks

When the old Frauenkirche was gradually demolished, the Weller organ was vacant. It was finally divided, 9 registers were donated to the church of the village of Plauen in 1745 . City organ builder (and later court organ builder) Tobias Schramm (1701–1771) used these to build the organ for the church in Plauen. From the other 11 registers, Johann Christoph Leibner created an inexpensive organ, which the Loschwitz community purchased and which was consecrated in the Loschwitz church in 1753 .

Both organs no longer exist: the organ, consecrated in the Loschwitz church in 1753, was replaced by a Jehmlich organ in 1899 . The organ, consecrated in Plauen in 1746, was destroyed in 1813 during the Battle of Dresden .

Bells

In 1472 the old Frauenkirche received its first roof turret, on which bells were attached in the following year, so it is said about the year 1473: “Kumoller has to do with the bells. Master Lenhart seems to have cast this. ”Caspar Beyer created a new roof turret, which existed until 1722, in 1497. The wooden turret was octagonal and covered with slate. At the top it had four bay windows, on which four gilded tower buttons with star ends were attached. The cock of the church tower was replaced in 1699 by a flag with the Dresden coat of arms.

A new bell is mentioned in 1517. Around 1530, Nickel von Zwickau hung up a new church bell. These bells were melted down after the church was closed during the Reformation in 1539.

It was not until 1556 that Elector August donated three bells to the church from the secularized Altzella monastery . They were hung in the roof turret in 1557. In addition to the three bells, a fourth bell was added in 1619, which Johann Hilliger cast. It was the biggest bell of the peal.

In 1722 the dilapidated roof turret of the Frauenkirche was torn down and the bells hung on a bell tower in the churchyard, which was only demolished in 1735. The two smallest of the three former monastery bells were given to Johann Gottfried Weinhold in 1732 , who melted them down and made new bells for the Bährsche Frauenkirche. The bell, cast by Hilliger in 1619, was melted down in 1917 for armament purposes .

The third monastery bell came from the Frauenkirche to the institutional church of the Hubertusburg State Institution in 1925 , as it did not sound like the new Frauenkirchbells that were cast in 1925. In 1940 it was included in the D-bell list and was one of the bells "whose permanent preservation was advocated because of their high or historical value [...]". The bell passed into the possession of the parish of Wermsdorf after 1945 and was taken over by the parish of Dittmannsdorf in 1960 . In Dittmannsdorf it was the middle bell of the village church bell. In 1998 the bell came back to Dresden and was hung on a bell carrier on the building site of the Frauenkirche. Here she rang the bell for devotions and services. Since 2003 it has been part of the eight-part Frauenkirchen bells as the “Maria” memorial bell.

| Casting year | Caster | Height in cm | Ø in cm | Inscription, jewelry | origin | Whereabouts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1489 | Oswald Hilliger ? | 39.0 | 45.0 | “The silver one”, inscription: “Afe Maria Gracia, plena, Dominus thekum Mader myserikortie”, year mcccc lxxxix | Altzella | Melted down in 1734 |

| 13th century | not handed down | 63.7 | 70.8 | had a sugar loaf shape, with no inscription | Altzella | Melted down in 1734 |

| 1518 | Martin Hilliger ? | 69.0 | 84.6 | "Afe Maria Gracia, plena, Dominus thekum Mader myserikortie mccccc xviii jar", sparse decoration | Altzella | Part of the Frauenkirchen bells |

| 1619 | Johann Hilliger | 84.0 | 111.0 | The Hillger coat of arms with the inscription “Johann Hilger f. MDCXIX ”, on the edge of the bell the inscription“ Laudo Deum verum plebem voco congrego clerum defunctos ploro cor suscito festa decoro. ”Underneath an eagle in tendrils | Dresden | Melted down in 1917 for armament purposes |

Further equipment and church decorations

- Painting of the church

Paint residues on traditional arched workpieces of the nave show that the church was probably painted gray on the inside and had white joints in the Middle Ages. Michaelis wrote in 1714 that the nave had two-story galleries made of wood with gray-white marbling; parts of the choir were also marbled. The field ceiling of the nave from 1557 was painted by Andreas Bretschneider among others until the end of the 16th century; The individual biblical scenes from the Old and New Testament were donated and the names of the donors or their coats of arms were noted on the pictures. Like the field ceiling, the council gallery in the south aisle was decorated with scenes from the Bible.

The vaults of the long choir were painted in 1596. The ceiling was decorated with drawings of the Saxon provincial coats of arms , above the altar there was the Agnus Dei in one curve, while in the other curve “the Passion of Christ / as hands / feet / and heart / with the thorns crone and third nails can be seen [was] ”.

- Windows and candlesticks

Little is known about the window decorations. In 1626, the jeweler Michael Ayrer donated a glass votive tablet to the church . The so-called "Ayrersche Wappenscheibe" was inserted in the window to the southeast of the altar and after the demolition of the church returned to the property of the donor family. It has been preserved in private ownership in Berlin to this day.

The room was lit by a 24-armed chandelier that hung in the middle of the choir. It was made in Nuremberg in 1667 and later hung in the choir in the new Bähr building.

- Church utensils

Several vessels have been preserved from the old Frauenkirche. A gold-plated silver chalice was donated by Elector August in 1558, according to the inscription on the foot edge. It is a late Gothic mass chalice from the pre-Reformation period, which was repaired for Lutheran worship in 1558. Two other chalices also come from the Gothic period.

A silver, gold-plated communion jug has also been preserved, donated to the Frauenkirche in 1637 by Zacharias Heroldt. It bears the master's mark of the Dresden silversmith Michael Botza.

- Baptismal font

The old Frauenkirche has had no baptismal font since the Reformation, as baptisms were only carried out in the Kreuzkirche. There are no references to a baptismal font before the Reformation.

meaning

Church and churchyard as burial places

For contemporaries, the Frauenkirche was primarily important as a burial place. Originally only clergymen were allowed to be buried in it, but from the 16th century onwards, founders as well as nobles and citizens were also allowed to be buried. Among others, Johannes Cellarius , Christian Schiebling , Christophorus Bulaeus , Heinrich Schütz and Andreas Herold were buried in the church . Around 1714 the walls and floor of the Frauenkirche were still covered with epitaphs, of which only a few have survived.

In addition to the Frauenkirche, the Frauenkirchhof served as a burial place. It is the oldest known burial place on Dresden soil ; the earliest grave finds are dated to around 1100. The churchyard was one of the few burial places in the city, could no longer be extended due to increasing renovation in the 16th century and was therefore soon too small for the dead of the city. Because of this, the graves had to be relocated at short intervals. The excavated bones found a new place in the " charnel house " in the churchyard in underground vaults. The ossuary was consecrated in 1514 by Bishop Johannes von Meißen . The brotherhood of stonemasons and masons donated an St. Anne's altar to the ossuary chapel on this occasion. A wooden statue of Saint Anne has probably been preserved from the Anne's altar in the ossuary. In 1558 the ossuary was removed above ground, whereby the underground vaults were preserved. They were still to be found in 1714 "completely filled with bones and kept with an iron door".

The nobility preferred the Frauenkirche as an exclusive burial place, but its capacity was soon exhausted. From 1561 to 1562 the master mason Voitt Grohe erected candle arches on the church wall and later on the entire cemetery wall. By 1565, the churchyard received over 100 hereditary burial sites - chapel-like structures called Schwibbogen, with their own crypts - which made it a great burial place for the wealthy bourgeoisie and nobility. The Schwibbogen owners included the elector Oberfeldzeugmeister Caspar Voigt von Wierandt , in whose crypt the Saxon Chancellor Nikolaus Krell , who was executed in 1601, found his final resting place, the sculptor and Dresden Mayor Hans Walther and Chamber Master Hans Harrer . Some of the candle arches were lavishly furnished and the vaults painted, such as the family funeral of Centurio Wiebel by the painter Samuel Bottschildt . The large number of artistically valuable epitaphs prompted the Kirchner of the Frauenkirche Johann Gottfried Michaelis to write his Dreßdnische Inscriptiones und Epitaphia in 1714 , in which he recorded all 1351 grave monuments and inscriptions from the Frauenkirche and churchyard. Mainly simple grave slabs have survived, which were used as stone material for the new Frauenkirch building and were salvaged when the church was cleared in 1994.

Otto Richter summarized the importance of the church as a burial place in 1895: "All in all, the Frauenkirche and its surroundings formed a true museum of venerable works of art and historical memories." Magirius emphasized the different levels on which the Frauenkirche is still important as a burial place today: " While for Michaelis the […] still legible inscriptions on monuments were the focus of interest, the art historians of the 20th century were primarily interested in the artistically valuable grave monuments, while the archaeologists of the present were primarily interested in the forms and rites of burial. "

Change of meaning as a mother and city church

The Frauenkirche, which was probably founded shortly after 1000, is considered the oldest church in Dresden's Elbe Valley. In the Middle Ages it was the parish church for a vast parish: the entire eastern Elbe valley up to the southern slopes was parish into the Frauenkirche; She was responsible for the entire Gau Nisan except for Dohna and owned a Dos with the village of Poppitz , which she had been given as a gift when it was founded. A competing church was only built with the Nikolaikirche (from 1388 Kreuzkirche ), the church of a merchant settlement that was probably built shortly after 1100 and was 400 meters away from the Frauenkirche. As long-distance traders, its inhabitants were under royal protection and therefore had a higher social status than the Sorbs who visited the Frauenkirche. Despite its own congregation, the Nikolaikirche became a branch church of the older Frauenkirche and remained so when it received the status of a city church around 1150 with the expansion of the merchant settlement. The Frauenkirche was entitled to parish and burial rights.

The importance of the Frauenkirche for the Dresden area decreased, the more the importance of the city of Dresden and thus its city church increased; the cruciform church also had the status of a place of pilgrimage due to various relics . As early as 1400, the pastor moved from the rectory of the Frauenkirche to that of the Kreuzkirche. The Kreuzkirche, supported by the Elector, was the town church of the citizens and the Frauenkirche, supported by the town council, was the country church of the farmers of the surrounding area. After it was rebuilt from 1499 to 1516, the Kreuzkirche was far superior to the medieval Frauenkirche in terms of construction and furnishings - the Frauenkirche, however, retained its importance as a burial place. With the Reformation in 1539 the Frauenkirche finally lost its status as the main church of the city to the Kreuzkirche.

From 1539 to 1559, no more services were held in the Frauenkirche. The right to baptize passed to the Kreuzkirche. It was not until 1549 that the Frauenkirche was incorporated into the city and received the status of a second city church. The village of Poppitz, originally donated to the Frauenkirche, became the property of the city in 1550 despite the protest of the city pastor. Due to the structural and spatial inadequacies, ten of the original 26 villages were parished out of the Frauenkirche by 1714. The following 26 villages were originally parish in the Frauenkirche:

- Bannewitz

- Blowjoke

- Boderitz

- Coschütz

- Cunnersdorf ( parish to Plauen in 1670 )

- Dolzschen

- Gruna

- Kaitz ( parish to Leubnitz in 1670 )

- Pestilence

- Laubegast ( parish to Leuben in 1670 )

- Löbtau (half)

- Loschwitz (from 1706 own Loschwitz church )

- Mockritz

- Kleinnaundorf

- Naußlitz

- Nöthnitz (parish to Leubnitz in 1670)

- Prohlis (parish to Leubnitz in 1670)

- Vorwerk Räcknitz

- Reick (half; parish off to Leubnitz in 1670)

- Roßthal

- Seidnitz (parish to Leuben in 1670)

- Chasing

- Striesen

- Tolkewitz (parish to Leuben in 1670)

- Wachwitz (from 1706 part of Loschwitz)

- Vorwerk Zschertnitz

With the new building of the church by George Bähr, the subordinate position of the Evangelical Frauenkirche in the church constitution of Dresden did not change. It was not until 1878 that it was raised to the status of an independent parish church, into which parts of the inner old town and the Pirnaische Vorstadt were parish. In 1926 it was not she, but the Sophienkirche , which was elevated to the status of the Evangelical Cathedral of Saxony as a former court church. Both churches were destroyed in 1945. The Frauenkirche, which has since been rebuilt, has no permanent congregation to this day.

literature

- Karlheinz Blaschke : The Frauenkirche in Dresden's church history. In: Dresdner Geschichtsverein e. V. (Ed.): Dresden Frauenkirche. History - destruction - reconstruction . Dresdner Hefte, Vol. 10, No. 32, 3rd edition 1994, pp. 43-47.

- Cornelius Gurlitt : The Frauenkirche . In: Cornelius Gurlitt (arrangement): Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony . 21st issue: City of Dresden. CC Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1900, pp. 41–79.

- Gitta Kristine Hennig: The course of construction activity at the Frauenkirche in the years 1724–1727 . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. Yearbook on its history and its archaeological reconstruction . Volume 1. Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 1995, pp. 86-110.

- Walter Hentschel : Dresden sculptor of the 16th and 17th centuries. Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 1966.

- Manfred Kobuch : The beginnings of the Dresden Frauenkirche . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-7400-1189-0 , pp. 47-52.

- Heinrich Magirius : The Dresden Frauenkirche by George Bähr . Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-87157-211-X , pp. 11–32.

- Heinrich Magirius: The church "Our Dear Women" in Dresden - the predecessor of the Frauenkirche George Bährs . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-7400-1189-0 , pp. 53-70.

- Johann Gottfried Michaelis : Dreßdnish Inscriptiones and Epitaphia. Which monuments of those who rest in God are buried here in and outside of the Church to Our Lady… . Schwencke, Alt-Dresden 1714, foreword.

- Otto Richter : The Frauenkirchhof, Dresden's oldest burial place . In: Dresdner Geschichtsblätter , No. 2, 1894, pp. 124-134.

- Reinhard Spehr : excavations in the Frauenkirche of Nisan / Dresden . In: Judith Oexle (ed.): Early churches in Saxony. Results of archaeological and architectural studies . Konrad Theiss, Stuttgart 1994, pp. 206-217.

- City Museum Dresden , Foundation Frauenkirche Dresden (Ed.): The Frauenkirche zu Dresden. Becoming - effect - reconstruction. Exhibition catalog . Sandstein, Dresden 2005, pp. 11-27.

- Rainer Thümmel , Karl-Heinz Lötzsch : The ringing of the bells of the Dresden Frauenkirche in the past, present and future . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2000 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2000, ISBN 3-7400-1122-X , pp. 243-255.

Web links

References and comments

- ^ Walter Schlesinger : Church history of Saxony in the Middle Ages. Volume 1: From the beginning of church proclamation to the end of the investiture dispute . Böhlau, Cologne 1962, p. 147.

- ↑ Manfred Kobuch : The beginnings of the Dresden Frauenkirche . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, p. 47.

- ^ Heinrich Magirius : The Dresden Frauenkirche by George Bähr . Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, Berlin 2005, p. 12.

- ^ Karlheinz Blaschke : The Frauenkirche in the Dresden church history . In: Dresdner Geschichtsverein e. V. (Ed.): Dresden Frauenkirche. History - destruction - reconstruction . Dresdner Hefte, Vol. 10, No. 32, 3rd edition 1994, p. 43.

- ^ Walter Schlesinger: Church history of Saxony in the Middle Ages. Volume 1: From the beginning of church proclamation to the end of the investiture dispute . Böhlau, Cologne 1962, p. 198.

- ↑ Anton Weck : The Chur-Princely Saxon widely-called Residentz and Haupt-Vestung Dresden description and presentation . Joh. Hoffmann, Nürnberg 1680, p. 245: “ The time of the foundation was not recorded by the ancestors; and the like report brought to posterity / so that one could decrease the actual age / but one has for almost several 90th years / when the church was ground on the ceiling / from a year = number of old people report after / removed that already at the same time in the 560th year. "

- ↑ Anton Weck: The Chur-Princely Saxon widely-called Residentz and Haupt-Vestung Dresden description and presentation . Joh. Hoffmann, Nuremberg 1680, p. 13: “So it is certain / that Dresden was already well known for quite a time before the 1000th year after the birth of Christ / in mass Dresserus in its cities = Chronicki and other authors, but especially from the Pirnischen Münche / Johann Lindnern / an = and stated that Dresden at the time of Kayser Heinrich des Voglers / and Kayser Ottens / was a patch / alda it was a Taberne or Schenckstädt / and a fortified Uberfarth on the Elbe / but is / what Ietzo mentioned / other form not to be understood as from the old Dresden / because New Dresden suffered damage very often after around the year 1020 as old Dresden before / and also at that time from the water / from the Elbe streams / damage. "

- ^ Johann Gottfried Michaelis : Dreßdnische Inscriptiones und Epitaphia . Schwencke, Alt-Dresden 1714, [p. 19/678] .: “ Only here it is difficult to determine / if this church at Sanct Marien or our dear women made the first start / or who was the foundation of it /. It would be desirable that complete news of this would not have been withdrawn from us at the same time as the farewell of their papists by the blessed Lutheran Reformation: So one could inform a well-meaning reader with better reasons about the foundation and funders. But it is probable that it may have already stood around the one thousand and twentieth year. Because at that time the people because of great water damage, which they often suffered in Alt-Dreßden from the Elbe / started to build this side of the Elbe, because the land was higher here / than in Alt-Dreßden. If one can trust the saying of old people / who once lived / when the ceiling of the church was newly ground and at that time a year was found; so the year given above must be correct. "

- ↑ a b c d e Reinhard Spehr : Excavations in the Frauenkirche of Nisan / Dresden . In: Judith Oexle (ed.): Early churches in Saxony. Results of archaeological and architectural studies . Konrad Theiss, Stuttgart 1994, p. 211.

- ^ Society for the Promotion of the Reconstruction of the Frauenkirche Dresden eV (Ed .; Authors: Dr. Claus Fischer, Dr. Hans-Joachim Jäger, Dr. Manfred Kobusch): The Dresden Frauenkirche. From the beginning to the present. Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-00-021620-6 , p. 12: “ Around 1000 […] Surrounded by a cemetery with Christian burials since the end of the 10th century, the church is consecrated to the Virgin Mary (ecclesia Beate Virginis) . "

- ↑ Manfred Kobuch: The beginnings of the Dresden Frauenkirche . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, p. 52.

- ↑ a b Reinhard Spehr: Excavations in the Frauenkirche of Nisan / Dresden . In: Judith Oexle (ed.): Early churches in Saxony. Results of archaeological and architectural studies . Konrad Theiss, Stuttgart 1994, p. 212.

- ^ Karl Friedrich von Posern-Klett (Ed.): Document book of the city of Leipzig and its monasteries. Volume 2 (= Codex diplomaticus Saxoniae regiae (CDS) II 9). Giesecke & Devrient, Leipzig 1870, No. 13.

- ↑ See Harald Schieckel (edit.): Regesta of the documents of the Saxon main archive in Dresden . Volume 1., 948-1300. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1960, p. 351.

- ↑ Manfred Kobuch: The beginnings of the Dresden Frauenkirche . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, p. 48.

- ^ Johann Gottfried Michaelis: Dreßdnische Inscriptiones und Epitaphia . Schwencke, Alt-Dresden 1714, [p. 20/678].

- ↑ a b Cornelius Gurlitt: The Frauenkirche . In: Cornelius Gurlitt (arrangement): Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. 21st issue: City of Dresden . CC Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1900, p. 41.

- ^ Heinrich Magirius: The Dresden Frauenkirche by George Bähr . Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, Berlin 2005, p. 19.

- ^ A b Heinrich Magirius: The Dresden Frauenkirche by George Bähr . Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, Berlin 2005, p. 21.

- ^ A b c Johann Gottfried Michaelis: Dreßdnish Inscriptiones and Epitaphia . Schwencke, Alt-Dresden 1714, [p. 24/678].

- ↑ a b c Heinrich Magirius: The church “Our Dear Women” in Dresden - the predecessor of the Frauenkirche George Bährs . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, p. 58.

- ↑ Cornelius Gurlitt: The Frauenkirche . In: Cornelius Gurlitt (arrangement): Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. 21st issue: City of Dresden . CC Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1900, p. 44.

- ↑ a b c Heinrich Magirius: The church “Our Dear Women” in Dresden - the predecessor of the Frauenkirche George Bährs . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, p. 67.

- ↑ Gitta Kristine Hennig: The course of construction activity at the Frauenkirche in the years 1724–1727 . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. Yearbook on its history and its archaeological reconstruction . Volume 1. Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 1995, p. 93, FN. 30th

- ↑ Gitta Kristine Hennig: The course of construction activity at the Frauenkirche in the years 1724–1727 . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. Yearbook on its history and its archaeological reconstruction . Volume 1. Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 1995, p. 94.

- ↑ a b Gitta Kristine Hennig: The course of construction activity at the Frauenkirche in the years 1724–1727 . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. Yearbook on its history and its archaeological reconstruction . Volume 1. Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 1995, p. 103.

- ↑ Gitta Kristine Hennig: The course of construction activity at the Frauenkirche in the years 1724–1727 . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. Yearbook on its history and its archaeological reconstruction . Volume 1. Schnell and Steiner, Regensburg 1995, p. 104.

- ↑ See Spehr 1994, p. 212. Magirius (2002, p. 54) gives the width as 25.50 meters.

- ↑ The reconstruction of the exterior and interior of the church is possible using contemporary engravings and descriptions. Further data could be obtained through archaeological excavations. However, in some cases it is not possible to make clear statements due to contradicting information in contemporary works.

- ↑ Heinrich Magirius: The Church "Our Dear Women" in Dresden - The predecessor of the Frauenkirche George Bährs . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, p. 57.

- ^ Heinrich Magirius: The Dresden Frauenkirche by George Bähr . Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, Berlin 2005, p. 16.

- ↑ a b Heinrich Magirius: The Church “Our Dear Women” in Dresden - The predecessor of the Frauenkirche George Bährs . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, p. 54.

- ↑ a b Heinrich Magirius: The Church “Our Dear Women” in Dresden - The predecessor of the Frauenkirche George Bährs . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, p. 56.

- ↑ Heinrich Magirius: The Church "Our Dear Women" in Dresden - The predecessor of the Frauenkirche George Bährs . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, p. 57; Johann Gottfried Michaelis: Dreßdnish Inscriptiones and Epitaphia . Schwencke, Alt-Dresden 1714, [p. 24/678].

- ↑ a b c d e Cornelius Gurlitt: The Frauenkirche . In: Cornelius Gurlitt (arrangement): Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. 21st issue: City of Dresden . CC Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1900, p. 42.

- ↑ Michaelis stated the dimensions of the church in 1714 as 65 cubits long, 41 cubits, 5 inches wide and 17 cubits high from floor to ceiling. Cf. Johann Gottfried Michaelis: Dreßdnish Inscriptiones and Epitaphia . Schwencke, Alt-Dresden 1714, [p. 24/678].

- ↑ Torsten Remus: Findings list of the stone found in 1993 during the archaeological clearing of rubble and reused in the new baroque building of the Frauenkirche . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus Successor, Weimar 2002, pp. 71–81.

- ↑ a b c d Johann Gottfried Michaelis: Dreßdnish Inscriptiones and Epitaphia . Schwencke, Alt-Dresden 1714, [p. 29/678].

- ^ Michaelis [p. 33/678] referred to the Münzertor as the large gate on the south side.

- ↑ a b c d Heinrich Magirius: The church “Our Dear Women” in Dresden - the predecessor of the Frauenkirche George Bährs . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, p. 70.

- ↑ a b Heinrich Magirius: The Church “Our Dear Women” in Dresden - The predecessor of the Frauenkirche George Bährs . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, p. 59.

- ↑ Heinrich Magirius: The Church "Our Dear Women" in Dresden - The predecessor of the Frauenkirche George Bährs . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, p. 55.

- ↑ Heinrich Magirius: The Church "Our Dear Women" in Dresden - The predecessor of the Frauenkirche George Bährs . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, p. 60.

- ^ A b Johann Gottfried Michaelis: Dreßdnische Inscriptiones und Epitaphia . Schwencke, Alt-Dresden 1714, [p. 21/678].

- ↑ a b Heinrich Magirius: The Church “Our Dear Women” in Dresden - The predecessor of the Frauenkirche George Bährs . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, p. 61.

- ↑ Cornelius Gurlitt: The Frauenkirche . In: Cornelius Gurlitt (arrangement): Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. 21st issue: City of Dresden . CC Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1900, p. 45.

- ↑ a b c d Johann Gottfried Michaelis: Dreßdnish Inscriptiones and Epitaphia . Schwencke, Alt-Dresden 1714, [p. 28/678].

- ↑ Cornelius Gurlitt: The Frauenkirche . In: Cornelius Gurlitt (arrangement): Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. 21st issue: City of Dresden . CC Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1900, p. 47.

- ↑ a b Heinrich Magirius: The Church “Our Dear Women” in Dresden - The predecessor of the Frauenkirche George Bährs . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2002, p. 68.

- ^ Walter Hentschel: Dresden sculptors of the 16th and 17th centuries . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 1966, p. 46.

- ↑ a b Walter Hentschel: Dresden sculptors of the 16th and 17th centuries . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 1966, p. 123.

- ↑ a b Cornelius Gurlitt (arr.): Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. 31. Issue: Official team of Bautzen, 1st part . CC Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1908, p. 29.

- ^ Richard Steche (arrangement): Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. 1. Booklet: Official Authority Pirna . CC Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1882, p. 89.

- ^ A b Heinrich Magirius: The Dresden Frauenkirche by George Bähr . Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, Berlin 2005, p. 28.

- ↑ General Artist Lexicon (AKL). The visual artists of all times and peoples. Volume 9 . KG Saur, Munich 1994, p. 432.

- ^ Johann Gottfried Michaelis: Dreßdnische Inscriptiones und Epitaphia . Schwencke, Alt-Dresden 1714, [p. 30-31 / 678].

- ^ Paul Dittrich: Between Hofmühle and Heidenschanze. On the history of the Dresden suburbs Plauen and Coschütz. 2nd, revised edition, Verlag Adolf Urban, Dresden, 1941, p. 31 with footnote 41.

- ^ Friedrich Wilhelm Pohle: Chronicle of Loschwitz . Verlag Christian Teich, Dresden 1883, p. 143.

- ^ Johann Gottfried Michaelis: Dreßdnische Inscriptiones und Epitaphia . Schwencke, Alt-Dresden 1714, [p. 33/678].

- ^ Johann Gottfried Michaelis: Dreßdnische Inscriptiones und Epitaphia . Schwencke, Alt-Dresden 1714, [p. 34/678].

- ^ Rainer Thümmel, Karl-Heinz Lötzsch: The ringing of the bells of the Dresden Frauenkirche in the past, present and future . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2000 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 2000, p. 245.

- ↑ Cornelius Gurlitt: The Frauenkirche . In: Cornelius Gurlitt (arrangement): Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. 21st issue: City of Dresden . CC Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1900, p. 45.

- ↑ Cornelius Gurlitt: The Frauenkirche . In: Cornelius Gurlitt (arrangement): Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. 21st issue: City of Dresden . CC Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1900, p. 50. See also Michaelis [33/678].

- ^ Johann Gottfried Michaelis: Dreßdnische Inscriptiones und Epitaphia . Schwencke, Alt-Dresden 1714, [p. 31/678].

- ^ Johann Gottfried Michaelis: Dreßdnische Inscriptiones und Epitaphia . Schwencke, Alt-Dresden 1714, [p. 31-32 / 678].

- ↑ Matthias Weiss: The Ayrersche coat of arms from the old Frauenkirche in Dresden. Swiss glass art in Saxony . In: The Dresden Frauenkirche. 2002 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus Successor, Weimar 2002, pp. 82–109.

- ↑ Stadtmuseum Dresden, Frauenkirche Dresden Foundation (ed.): The Frauenkirche zu Dresden. Becoming - effect - reconstruction . Exhibition catalog. Sandstein, Dresden 2005, pp. 19-20.

- ↑ Otto Richter: The Frauenkirchhof, Dresden's oldest burial place . In: Dresdner Geschichtsblätter , No. 2, 1894, p. 125.

- ^ Johann Gottfried Michaelis: Dreßdnische Inscriptiones und Epitaphia. Schwencke, Alt-Dresden 1714, [p. 23/678].

- ↑ Otto Richter: The Frauenkirchhof, Dresden's oldest burial place . In: Dresdner Geschichtsblätter , No. 2, 1894, 130.

- ↑ a b Karlheinz Blaschke: The Frauenkirche in Dresden Church History . In: Dresdner Geschichtsverein e. V. (Ed.): Dresden Frauenkirche. History - destruction - reconstruction . Dresdner Hefte, Vol. 10, No. 32, 3rd edition 1994, p. 44.

- ^ Karlheinz Blaschke: The Frauenkirche in the Dresden church history . In: Dresdner Geschichtsverein e. V. (Ed.): Dresden Frauenkirche. History - destruction - reconstruction . Dresdner Hefte, Vol. 10, No. 32, 3rd edition 1994, p. 46.

- ^ Johann Gottfried Michaelis: Dreßdnische Inscriptiones und Epitaphia . Schwencke, Alt-Dresden 1714, [p. 26/678].

- ↑ The unnumbered preface is counted according to the page number of the online edition of the SLUB Dresden .