Gusle

The Gusle (also Gusla , plural Guslen ; Albanian Lahuta ) is a traditional string instrument from the Balkans . Belonging to the group of chordophone instruments, it is a lute with a bowl neck that is struck with a horsehair string with a simple bow, a more original stringed instrument of folklore and folk music. The pear-shaped sound box, ideally made of maple wood , is covered with animal skin. The head of the gusle is mostly decorated with stylized animal motifs such as ibex or horse head, but more recently also falcons, eagles or portraits of historical personalities. The ornamentation and material of the gusle originate from the pastoral culture. It is one of the oldest solo musical instruments on the Balkan Peninsula and has remained unchanged in its original form and way of playing until today ( ).

The gusle is the instrument of the epic singer of the Balkan Peninsula in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro and Serbia, who is called Guslar ( Guslari ) or Albanian Lahutar . The Guslar sings and accompanies himself on his Gusle. While the classical epics, which were formerly only passed down orally, today come from the broad written context of folk poetry, the musical component in Guslenspiel remains true to the traditional practice, in which even during today's important competitive performances, musical improvisation, comparable to the practice in jazz, in its traditional tradition has remained the dominant principle.

It was only with the writing of the epic songs by Vuk Stefanović Karadžić (from 1814) that oral poetry actually began to be written down, the repertoire of which today largely comes from this corpus and includes the classical anthology (in a Confucian sense) of oral literature in the Serbian language. These epics were not written by the Slavic and Albanian population as a medium of art, but are rather a complex medium of expression that sums up the long cultural history in great depth. In their oldest forms they come from the Middle Ages and still carry pagan- animistic ideas , which stand out so conspicuously in the folk culture of the southern Slavs. The epics add up several centuries of historical reality and spiritual needs. The gusle itself, made of maple wood, also symbolizes the mediation with the ancestral cult and is in itself the emblem of epic song as well as a symbol of national identity in its home countries.

Milman Parry and Albert Bates Lord developed the basis of the oral poetry theory in the context of the Homeric question from views on the stylistic methodology of the orally traditional folk epic, which was still strongly present at the time, among illiterate Christian and Muslim cast-iron players in Montenegro and south-west Serbia . As a result, the patriarchal regions of Yugoslavia, in which the Guslenspiel had been preserved in its original form until over the second half of the twentieth century, became an “epic laboratory”, the starting point for the investigation of poetic language and the use of substitutable “formulas” for oral poetry to a new, globally received literary direction - oral literature - provided essential impulses as well as a comparative methodology in the investigation of oral poetry in the epic literature of antiquity, in Byzantine Greek, Old English and Old French.

etymology

The word Gusle comes from the Old Slavic word "gosl" for fiber. The Old Slavic stem morpheme gǫdsli (Russian gúsli , Slovak husle , Czech housle ) is associated with guditi, or gudalo. The exact origin of the nominations of the related terms gusle, gadulka , gudok and gudalo, the latter as the name for the bow of the gusle, could, according to Walther Wünsch, shed light on a more precise assignment in the history of the development of the gusle.

In the linguistic usage of the South Slavs there is the feminine plural tantum “gusle” , which has established itself as a lexeme, as well as the older “gusli” , which can be found in the area of the central Drinalauflauf, around Arilje and throughout Montenegro. The use of the morphemes / e / and / i / can be found in the linguistic usage of one and the same speaker, alternating it can also be used in the lyrics or everyday language. The singular form “gusla” is only found in eastern Serbia, west of the Timok, around Niš, Ivanjica, and in the area of Zlatibor. Only “gusla” is used on Korčula. The term "gusle" was introduced into European literature by Alberto Fortis.

The Albanian lexeme lahuta also refers to another instrument, a kind of lute with eight strings that are plucked with quills. The Albanian lahuta , like the German lute, goes back to Arabic al-'ud zu ud (wood, instrument made of wood, zither, lute).

In Serbo-Croatian usage, the Gusle is a feminine plural tantum ( Serbo-Croatian Gusla / Gusle , Serbian - Cyrillic Гусла / Гусле ; Albanian definite lahuta , indefinite lahutë ).

Construction and parts

A gusle consists of the neck ( Držak ), the head, the vertebra ( Rukuć or Klin ) and the resonance box ( Varnjačka ).

The thick strings of the gusle are made up of up to 30 horsehair, a relatively unusual material for stringing an instrument. The horsehair tears easily, so you have to tune and play the instrument carefully. The string position of the Gusle is similar to that of the Gadulka and Lijerica .

The Gusle is constructed similarly to the Gadulka , but differs from it in that it has a narrower and considerably longer neck. Instead of the wooden resonance board, the gusle has a stretched skin.

The strings of gusle are much too far from the neck away to pushing down on the neck. The sound of the gusle is very oriental in contrast to the gadulka or the lijerica , which have a violin-like sound.

The sound body is covered with a thin animal skin, which contributes to the characteristic sound of the gusle. The gusle is bowed with a large, wooden horsehair bow , but a normal violin bow can also be used.

| German | Albanian | Bosnian | Croatian | Serbian |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gusle | lahuta | gusle | ||

| Resonance box | trupi | varljača | varjača | |

| neck | qafa | vrat | vrat | |

| head | coca | glava | glava | |

| whirl | kurriz | ključ | ||

| string | korda | strune | ||

| web | shala | konjić | ||

| arc | harku | lučac | ||

ornamentation

It is arguably the most elaborately decorated Balkan musical instrument. At the head of the bridge there is usually an animal head carved out of wood such as goat, ram or horse head, birds such as eagles or even anthropomorphic figures. The bridge itself is decorated with rich patterns, sometimes entwined with snakes carved into the wood. The individual ornaments such as the capricorn, the symbol of absolute freedom, or the emblem of the snake for the danger of evil, are motifs of popular culture in which pagan-animistic ideas find their expression.

The back of the sound box bears elaborate floral patterns such as the tree of life ornament, rosettes and braided patterns. The bows, too, are often ornamental, then mostly in the form of a coiled snake. Newer Guslen often had state emblems as a motif, especially up until the transition phase in the transition from socialist to democratic societies. In Montenegro, the type of ibex head most commonly used in the past is now being replaced by eagle or falcon symbols.

materials

Various traditional Gusle materials are 30–40 combed horsehair for the bow. The arch itself is made of well-dried hardwood, mostly branches of the cornel cherry . The resonance box and neck are cut from one piece of wood. At best, a quarter of a tree trunk is used, in which the gusle is only made from the less brittle sapwood . Among the used trees that sound wood supply, this maple is estimated, as a so-called džever javor (German Riegel maple, English: curly maple ) or belo Javorje drvo (white maple ), which from the sycamore and Bosnia, Montenegro, southwest Serbia and Albania also comes from the Greek maple . The use of bar maple (= sycamore maple) can also be found in violin making. Also in the songs in the opening lines of today's lectures the evocation Gusle, made from maple wood ( gusle moje, drvo javorovo ) , often appears. In its function as tonewood, the maple also has ritual symbolism, as it is still used as coffin material in burial rites. Pine, oak, walnut and mulberry can also be used.

In contrast to violins, the cast body is made from one piece by applying the contours of the gusle to a 10 cm thick piece of wood using a template and carving out the shape of the instrument with carpentry tools. At the depth of the resonance body, about 8 cm is desired in order to obtain the preferred sound. Classically, the length of the resonance body is equal to the length of the distance from the neck to the vertebra, i.e. about 30 cm to 30 cm. The width of the resonance body is usually a little over 20 cm and the length of the bow should be around 40 cm. Depending on the decorations on the head, Guslen usually reach overall lengths of between 65 and 90 cm.

The skin cover is stretched out at the edges of the resonance box and mostly contains a few resonance holes. Goat, sheep, rabbit and donkey fur are used as a blanket, the skin of goats is generally considered to be the best. In the classic Guslen construction, the ceiling is tensioned by wooden rivets that have been worked out in the resonance body. Nails are also used less often.

Greek and sycamore maples

In cult and custom

In the folk culture of the southern Slavs, the maple generally has a higher cultic significance and sacred veneration than is the case in Central Europe. Maple trees are the bearers of pagan and animistic ideas of the tree cult among the southern Slavs , which stand out so conspicuously in the folk culture of the southern Slavs. The southern Slavs believe that the maple tree, as an emblem of the ancestor cult, is also the temporary home of the soul. Just as it is a widespread custom in many cultures to cut religious symbols into the bark of a tree, cutting cultic ornamentation into the gusle also has a spiritual function that distinguishes it as an object of cultic veneration.

Another point of importance arises from the popular belief in the forest spirits of the Vilen, who are born on trees, and are also most often seen on trees or in their vicinity, also being the souls of trees. According to popular belief, the life of the Vilen is inextricably linked to the tree in which they inhabit. If you destroy the tree, the vila loses its life. The rhetorical figure “gusle moje, drvo javorove” (“Oh my Gusle, wood of the maple tree”) serves as an idea of the “tree soul”, often sung as a mantra by the Guslaren in the first line of the song, it underlines the connection between the spiritual function of the Gusle who determined Guslar to mediate with the cult of ancestors.

The sacred character is often found in songs of the ten-syllable Serbo-Croatian folk epic , such as in the chant "Ženidba voivoda Pavla" . Here the story of a tragic honeymoon is told through images of symbolic actions and places, in which six forests have to be crossed: "three fir forests and three maple forests". In the patriarchal ten-syllable Serbo-Croatian folk epic, the evergreen firs have a sacred character as trees of life and sometimes as tragic connections to youth and especially as a symbol of a beautiful young woman; on the other hand, the maple, when used as a coffin and as a gusle, also suggests an ambiguous suggestion as an emblem of death. This ambiguity is fulfilled in the story in the journey under the trees of life and death, when the bride dies on the way to her bridegroom in one of the maple forests and proclaims in death that the bridegroom was not intended for her by fate.

The significance of animistic images of maple trees in the restoration of a patriarchal order emerges, for example, in the feudal long-lined Bugarštica Sultana Grozdana i Vlašić Mlađenj written in the Bay of Kotor in the 18th century . Here the unrealistic love affair of a Christian knight and a Turkish sultana is told in a rose garden in Constantinople, in which the janissaries hang him on a maple tree after the affair is discovered. The story culminates in the last few lines when the sultan's daughter cuts her hair in mourning and, to protect him from the sun, covers his face with it before she hangs herself on the same maple tree:

Sultana Prezdana i Vlašić Mlađenj

Brzo meni ufatite Mlađenja, mlada Vlašića,

I njega mi objesite o javoru zelenomu,

Mladoga Mlađenja!

BRZE sluge ošetaše po bijelu Carigradu,

I oni mu ufitiše Mlađenja, mlada Vlašića,

Te Careve sluge,

I Njega mi objesiše o javoru zelenomu,

A to ti mi začula Prezdana, lijepa sultana,

Lepa gospoda,

U ruke mi dofatila svilena lijepa pasa,

Ter mi brže ošetala put javora zelenoga,

Prezdana gospođa.

Tu mi bješe ugledala Mlađenja, mlada Vlašića,

A Dje mi on visi o javoru zelenomu,

Vlasicu junaku,

Ona bješe obrrezala sve svoje lijepe us kose,

Ter h bješe Stavila Mlađenju na bijelo lice,

junaku Vlasicu,

Da mu ne bi Zarko sunce bijelo lice pogdilo.

Pak se bješe uspela na javoru zelenomu,

Prezadana gospođa,

Tu se bješe zamaknula zu Mlađenja, mlada Vlašića,

Prezadana gospođa.

Tuj mlađahni visahu o javoru zelenomu.

Prezdan the Sultan's Daughter and Vlašić Mlađenj

Young Vlašić Mlađenj swiftly seize,

And hang him from the maple green

Young Mlađenj!

So swift they walked through the Imperial City,

Young Mlađenj Vlašić they did seize,

Those Sultan's vassals,

And from the maple green they hanged him,

When Prezdana fair had heard of this,

Fair Lady,

She took a lovely, silken sash,

And walked so swift toward the maple green,

The Lady Prezdana.

And Vlašić Mlađenj saw she there,

As from the maple green he hung,

Vlašić, the fine hero.

And off she cut her fine, fair hair,

And placed it over Mlađenj's face,

Heroic Vlašić's

Lest burning sun disfigure it.

And she climbed up the maple green,

The Lady Prezdana,

And there fell limp beside Young Mlađenj,

The Lady Prezdana.

So Young from maple green they hung.

Another element of the epic use of this maple emblem is found as a frequent formulaic element of a dried up maple tree ( javor suhi ) that bears yellow flowers. In the epic tradition, accusations of death by a miracle are fended off in the motif of the miracle sign of a blooming, dried up maple. With the embodiment of the maple in the ancestral cult and its use as a guslen material, this epic context of wondrous blossoming has the power to save human lives in extreme situations.

In craft and the forest industry

The wood of Greek and sycamore maple is by far the most important in Guslenbau. For example, the currently best-known Guslen instrument maker Slobodan Benderać Guslen only uses maple wood, whereby he particularly prefers high mountain origins from the Volujak Mountains on the border between Montenegro and Bosnia. As reported by the Montenegrin newspaper Vijesti, the felling of Greek maples for their own guslen needs, as well as for export to foreign sawmills that purchase tonewood for violin making, is of particular interest to the logging companies and loggers in the Kolašin region, which is due to the high prices that are sometimes paid for it, explained. As the daily reported, the police themselves had thwarted an attempt to illegally cut Greek maples in the jungle of the Biogradska gora National Park. A saber-growing trunk, known as the so-called džever javor = bar maple (or džever stablo = bar log ), is most valued. As the newspaper reported in another article, these bar maples were so popular because of their grain and suitability for musical instruments that even locations that were difficult to reach, such as in the high alpine Durmitor, were massively overused before the Second World War . Since Greek maples and mountain maples supply the most highly valued woods of the Dinarides as well as some of the most expensive European woods, the local legends say that up to 60,000 euros / m³ should be paid. Since real prices for bar maple wood are between 7,000 and 11,000 euros / m³, this is accompanied by overexploitation of the natural stocks by the local and often unemployed mountain population in Montenegro, Serbia and Bosnia.

variants

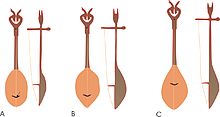

Walther Wünsch has distinguished a Serbian, Bosnian and Montenegrin Guslen type on the variants of the shape of the resonance body and the size of the Guslen. He also assigned the variants of the Dalmatian and Herzegovinian gusle to the latter.

There is no such thing as a pure type, as all forms are mixed together.

The differences between the three types can be found in the shape of the sound box, tone and type of playing:

- Serbian type - from the vicinity of Kruševc, to Kraljevo, Čаčak, to Užice and Bajina Bašta; Sound box with rhombic shape; rather small. Is played with crossed lower legs, sitting low and held between the knees. It is more of a more simply designed instrument that only produces a comparatively weak, rough, unkempt sound with little changeability.

- Bosnian type - from Višegrad to Sarajevo; similar to the Serbian type, especially in size; Sound box of deltoid shape. The main difference is the depth of the resonance body, which is mostly covered with numerous allegorical carvings due to the extremely high body.

- Montenegrin-Herzegovinian type - from Herzegovina, Bay of Kotor, Dalmatia and Montenegro; Sound box slightly rounded, pear-shaped and only flat sound box; big. Considered the best and most beautiful guy. Found in most professional guslars today. Is played in a higher sitting position with knees crossed and leaning against them. The Montenegrin type has a thinly scraped resonance box, in which a sound hole is often incorporated on the back. As a sonically best type with a bright, neat and sustaining sound.

Two-string guslen are rarely used in northwestern Bosnia, northern Dalmatia and the Lika . They were described by Matia Murko, later in western Dalmatia, as well as in Serbia in Ćuprija , in the area of Niš and Pirot , where he stated that beggars play the instrument. They are said to have been widespread in Syrmia , the Slavonska Krajina and the Batschka as Gege . The names and areas of the latter are assigned to the transition types between Gusle and Lirica . The second string produces a drone tone, the melody is played on the first string , which produces a higher tone. The two-string gusle is in principle the same as the one-string; but it is only played when lyrical songs are sung that are cheerful and danced to.

Functionality and types of play

The functioning of the gusle is a simple and natural one that adapts to the physiological structure of the human body. The bow technique of the right hand is not for dynamics, but balanced, the bow strokes the gusle in a less balanced non legato. When playing, the gusle is held between the knees while sitting or placed on the thighs. Often the lower part of the shins is also crossed, so that the sound body is held between the lower legs and one has a very comfortable playing posture.

The individual fingers of the left hand snap from the flank against the fretboard-free gusle and shorten the gusle string only in the air without pressing the string down. The grip technique thus preserves an old Slavonic-West Asian technique. Since the individual fingers are not trained, a series of tones arise that arise from the natural course of the striking fingers. The individual tone is not sharply outlined, clearly and unambiguously localized, but irrational, undetectable, an immaterial component of larger units. For the Guslaren, the individual tone is not important as an independent element in the classical musical sense, but he grasps it in its functional meaning within the melody line. Therefore an exact intonation does not play a role, as does the intonation fluctuations in the voice. Both are not based on lack of music, but are in the interest of the epic characteristics.

The singer only switches on independent instrument play during the prelude, after-play and interlude. The prelude also includes tuning the string to the pitch of the singing voice, followed by playing the fingers freely. This instrumental introduction serves to make the player's fingers supple and to put the singer and the listener in a heroic mood through figurative increases and faster play. Usually the singer does not start with his epic straight away, but introduces his story with a short narrative formula.

Sound system

The tone system of the Gusle was first noted by Gustav Becking in 1933 and Walther Wünsch in 1937.

Later, Béla Bartók also made a note of the sound recordings from the Perry Lord collection at Harvard.

Becking and Wünsch set up a system of five pitches that are functionally related to one another within the range of a fourth . The first level is the rest or exit tone, after which the gusle is tuned, but which is rarely used. The second stage, the finalis , corresponds to the first stage, the lowest note, in the interval of a major second . The third stage, the secondary finals, which is a small second apart from the final, leads from quiet recitation to emphasis or vice versa. The highest note, called "heroic" by Becking, forms a fourth with the first degree. In addition to these five levels, the Guslar uses various intermediate levels that cannot be precisely noted and serve to achieve different effects. Only in rare cases does the singer raise his voice to a height above the tone of the heroic level; likewise it seldom falls under the initial tone.

The five notes of the gusle are played with four finger grips without the thumb. The grips of the fingers on the string are not changed during the entire game and singing (at least in the classical technique), the tones generated with the fingers thus always remain the same during the game. The hand always holds the gusle below the vertebra, the fingers grip the string from this position, which is the most natural and comfortable position during the performance. The placement of the finger stops on the string are not marked, nor do the tones show rational whole and semitones.

All notes are used during the recitation, but only four of them are main notes, while the ring finger always has a subordinate function. The effect of irrational tones in Guslenspiel appears to listeners trained in European music as the effect of a detuned musical instrument; These irrational tones, on the other hand, are closely coordinated with the epic lecture and necessarily belong to the epic style of the Guslar. Any adaptation of the scales of irrational tones that have emerged from folk tradition by replacing intervals with diatonic scales degrades the character of the instrument performance. Only in the classical lecture does it remain a recitation of heroic content ( Robert Lachmann described such a diatonic modification as a degradation of the epic singer to a “village oratory”).

The tone system is thus fundamentally different from that of classical European music; all four intervals and five tones used for singing do not appear in European music. However, only minor shifts in the boundary are required to transform them into a series of whole and semitones and thereby align them with the modern system. Today, musically trained guslars also use chromatic scales individually.

The different physiological conditions of grasping for the individual fingers have an effect on the uneven arrangement of the tones. The singing adapts to the sound system, which is completely irrational from the standpoint of acoustics, the number of vibrations and string lengths. Overall, a pre-medieval system has been preserved in practice, especially with the Montenegrin Guslaren, whose playing style is assumed to be identical to today's practice by Gustav Becking and a thousand years ago.

The mood of the Montenegrin gusle is relatively high. The open string corresponds to a bowed c that is too high. The tone picked by the index finger is about 3/4 tone higher on d. The middle finger lies directly next to the first, which means that the next tone is an it that is too low. The ring finger, according to its different gripping movement, leaves a small space between the second and the fourth finger. He divides an e too low. The little finger touches the string approximately on the tone f.

This results in the ladder c - d - es - e - f. The spaces in whole tones are 3/4 - 1/3 - 1/2 - 2/3. Because it is grasped by the awkward ring finger, e has particularly fluctuating intonation. The important intervals are df and es-f, which correspond to a fairly pure minor third and too large a whole tone.

The musical function of the tones is irreversible in the Guslen system. The open string (c) is important in the instrumental preludes, interludes and re-enactments. In singing, however, it is only occasionally used as the lower level of the Fianlis, and without any particular characteristics. The next higher tone, d, as the second tone of the ladder picked up by the index finger, is the most common and the actual fundamental tone. It forms the finalis of by far most of the cadences, is the tone of the simple narrative, of calm, from which the large-scale increases begin and to which even the most excited parts always return. If d is played as the character tone in the verse, then this verse is played piano.

Individual cadences are ended on the es above (middle finger), the secondary finals. Becking calls this tone the cant tone. What D presents with calm expression is more emphatically, more excited, in any case louder, and consistently comparatively in mezzo forte. Verses that are determined with es are often alternated with d-verse, which often results in long series of pairs of opposites of normal tone and exaggerated tone.

e the tone of the ring finger is a dependent fill tone between the neighboring fingers that has no face of its own and never appears in the final. In contrast, f is the target and jump tone of all increases that culminate in it. The persistence and sustainability of the excitement depend on the duration of how long f the determining tone remains. However, he does not form cadences, they always fade away. f is the loudest, the Forteton in Guslenspiel. Piano never appears with an f. As a so-called “heroic tone”, all heroic passages are represented by f.

Musical use and singing

The function of the gusle is not only to support the singing, but also to deliver a prelude and interludes. The short overture is known to all oriental music, which adjusts both the audience and the singer to the spirit of the coming epic-recitative lecture. The interludes are usually short and are intended to emphasize the metric separations, mostly between two verses and give the singer time to breathe. During the lecture, the singing voice is highly tense and adjusted (“voice adjustment”). It is a feature of magical evocation that has found its way into church services as well as secular songs. In this as in other relationships, the epic recitation as performed by Balkan guslaren goes back to ritual chanting (or teamim ). Other common elements are the close connection of the musical structure to the text, the strict limitation to a few melodic turns and cadences, and in particular that only one presenter, epic singer or priest enchants a large group of listeners (Walther Wünsch speaks of "the audience in to influence the heroic sense of education "). The basic and original situation of the orally transmitted South Slavic epic are the unity of singing and at the same time making music Guslar and his respective audience, whose people are connected to him through inner participation. The Guslar has largely improvisational freedom in the form of reporting and narration, in the conduct of the action. At the same time, he adapts the respective design of the epic material to the preferred areas of interest of his audience and thus enriches their imagination. He often lingers on details, spins out parables, inserts thoughts, episodes, descriptions and reflections in order to delay the solution of the story for hours for the audience listening intently. For example, former guslars interrupted the song performance themselves at a special climax, which was then resumed the next day (e.g. with Avdo Medjedović). The traditional illiterate Guslar did not know songs, but only materials, stylistic tricks, standard expressions and typical formulas, which he arranges and rearranges as required and as a memory aid are elementary aids of epic song. This classical basic form of the Balkan hero song is best preserved in the Dinaric-Montenegrin hero song. It is a recitative singing of a very limited range, in which singing and declamation form an artistic unit and both are subordinate to the actual purpose of the hero song.

When the hero song is performed, the instrument melody coincides with the singing throughout. Voice and gusle therefore make music in unison. The function of the accompanying gusle is to hold the pitch; therefore the instrumental part is in principle identical with the singing. The tone system itself results from the natural fingering technique of the left hand. An exact intonation is not aimed for; Like the text design, the musical form also leaves room for creative improvisation. The special playing technique results in slight deviations. The epic, which can have a duration of up to two hours or more, is made up of ten-syllable non-rhyming verses. Each syllable corresponds to an embellished or non-embellished single tone on the gusle.

A few verses from the epic "Mijat, der Hajduke" can serve as an example of the theme of the songs:

The mountains who pulled Hajduk Mijat ,

after the green mountains he departed,

he seeks protection from Ljubović, the Beg .

Black earth saturates his hunger

And he quenches his thirst with ripe flowers,

Until the hero has gathered the crowd.

Epic talk

In the tradition handed down

The Guslen lecture has not changed over the centuries. For the Guslar, the tenor register is practically always required in the performance of the epic oratorio (to this day only a few women have become known as Guslars). Great oral poets like Filip Višnjić or Tešan Podrugović were able to move their listeners to tears with their special talent, as Leopold Ranke noted. This was mainly achieved through the ability to convey the national feel and spirit of the epics. The coordination of communication between Guslar and the audience is achieved in the Guslen lecture through the narration of a historical highlight in the collective use of epic language, in which well-known formulas from a wide range of simple elements of the genetic history are mixed with several moral concepts of biblical, feudal or patriarchal origin be achieved.

To this day it is customary for the audience to accompany certain lines or melodies by acclamation. A typical symbolic act in the Guslen lecture is that the Guslar before and often after his game, the Gusle reaches the audience like a sacred object and bows to them. The audience tries at concerts also often by a shouting addition of a certain Epic or Epic to a particular shape.

Observations by modern, Western European listeners also prove that the Guslaren's lecture creates and should create a special impression. Gabriella Schubert reports that she often observed how tears in the audience were in their eyes and that she left a lasting impression.

According to Schubert, the mode of action is controlled by several factors:

- Epic forms convey monumentality in themselves. With a raised voice, in festive clothing and in a solemn, ritualized attitude and mood, the epic singer addresses his audience.

- In the hero song, memories of fateful historical events and historical personalities are deepened into a prototypical heroic image of man.

- The suggestiveness of the presentation results from the combination of spoken song and accompaniment. Chanting and the content presented as well as the associated mood of the presentation, between solemn and melancholy as well as dramatic and charged with tension, resembles the declamatory prayer of clergy of the Orthodox Church.

- The singer sits upright with his head raised and his gaze directed into the distance or above. In this context, Walter Wünsch speaks of the "Montenegrin-Dinaric Herrenguslar" .

Schubert reports that she was told in 1988 by the fifty-year-old Guslaren Vojislav Janković from Drušići near Cetinje in Montenegro that a Guslar can only report impressively on heroes and heroic deeds if he himself assumes a proud, heroic stance. He mentally penetrates the world of the heroes he sung about and makes contact with them in order to draw inspiration for his lecture. He experienced the heroic deeds sung about by him and suffered the tragic fates associated with them.

Modern development

To this day the gusle dominates as a solo instrument, which is cultivated in numerous folklore clubs and is often only learned by self-taught people. Guslen are also taught in music schools in Serbia. There have been seldom attempts to combine the gusle with classical music such as the string quartet . Most successful was the work … hold me, neighbor, in this Storm… by Aleksandra Vrebalov with the Kronos Quartet , which was commissioned by Carnegie Hall . Other young musicians are also trying to establish the gusle in the world music scene. Including the multi-instrumentalist Slobodan Trkulja who, for example, integrated the gusle into an arrangement in the piece Svadbarska (German wedding song), as it was performed live with the band Balkanopolis at the 2010 EXPO in Shanghai.

After Bojana Peković won the Serbian version of Who's got Talent as a female guslar in 2012 , in which she continued to incorporate her instrument into modern arrangements in addition to classic Serbian epic Guslen songs, as a young woman she was able to meet the neo-traditional currents in Guslen folklore with Gusle , as well as the supposedly nationalist-minded folklore rejecting pro-western urban population groups to wrest a discourse in the gender context of traditional music. A further development in Bojana Peković's Guslenspiel took place through the integration of the Gusle into chamber music arrangements with the cellist Aleksandar Jakovljevic and the harmonist Nikola Peković. In this combination, they achieved second place in the world music category at the annual Castelfidardo Accordion Festival . At the end of October 2015, Bojana and her brother Nikola released their first CD with a modern recording of Gusle on the Serbian major label PGP-RTS. In addition to the setting of a poem by Jovan Jovanović Zmaj, there is also a poem written by Matija Bećković for the occasion.

Ivana Žigon as a dramaturge and director at the National Theater in Belgrade, used the Gusle in an exposed musical and scenic work on the big stage. In doing so, she probably combined the gusle with ballet for the first time in the repertoire, with Guslarin Bojana Peković in Njegoš nebom osijan , Žigon's musical and scenic work on the occasion of the bicentenary of the birth of Petar II. Petrović-Njegoš , not only the ballet pieces of the oratorio, but also accompanied the intermediate scenes in an untypically lyrical way. With the traditionally patriotic intonation of the oratorio, in which the gusle also accompanied little innovative choreographic ideas, the feature section of the performance denied artistic relevance.

In Stojite Galije Carske, another dramaturgical work by Ivana Žigon on the occasion of the centenary of the beginning of the First World War , Bojana Peković again embodied the national figure of Serbia as Guslarin. More than the previous work on Njegoš nebom osijan , Stojite Galije Carske became a great success for Žigon, which both the audience and the feature pages were inclined and in which Bojana Peković in the role of the national figure of Serbia was given a large part of the attention. Žigon received for this direction at the Moscow film and theater festival "Золотой витязь" (Golden Knight) in the presence of the Moscow Patriarch Kyrill I by the director Nikita Michalkow (who as Tsar Nicholas II was involved in the work as an actor) Direction award presented. From this work by Žigon, an interlude was dedicated to the memory of the Russian nurse Darja Aleksandrovna Korobkina and published as a separate musical and scenic interpretation by the soprano Marijana Šovran and the Guslarin Bojana Peković.

The American Graecist Milman Parry and other literary and ancient scholars as well as ethnologists of the twentieth century owed a large part of the research results on oral poetry theory to this typical lecture of epic art of singing as part of historical awareness, including on events in modern history . For example, the events of the Sarajevo assassination attempt in 1961 were presented to ethnological field researchers by young Yugoslavs in rural areas of Bosnia, and even recordings of the Sarajevski atentat recorded by Radoman Zarubica from the Zagreb label Jugoton were still popular in 1961.

In socialist Yugoslavia, the Guslaren leaned thematically on the guidelines of the real socialist “class society”, in that the leading nomenclature, such as the then communist president Josip Broz Tito, was celebrated in a striking way (including Titov put u Indiju dt. Tito's trip to India ). There were also incidents from the partisan war ( Ranjenik na Sutjesci or Po Stazama Krvavijem - Sutjeska - Guslar Branko Perović), or for a Yugoslav Guslar such an unusual topoi as the Kennedy assassination in Dallas ( Smrt u Dalasu ), which only passed on in the meantime Issues of the Turkish wars could "displace".

history

Origin and Distribution

Byzantine-Islamic mediation

Like the lutes Kopuz and Barbat , the gusle belongs to the instruments of the 1st millennium AD, whose home is Central Asia , and comes from the large mass of the older Near Eastern neck lutes, which are also common in Persian and Indian musical culture . At the time of the Slavs' invasion of the Balkan Peninsula and under the influence of Islamic culture in the 10th century AD, the gusle came to Europe as one of the exported cultural assets of the Orient . The horsehair playing string and the primitive bow , which conserves the second stage of development of the bow, speak for the oriental-Asian origin . The covering of the bowl-shaped body with animal skin also corresponds to Asian custom. Another mediation about Byzantium and the Byzantine Lyra led to the emergence of the Gusle, which was spread to all countries of the Balkan Peninsula.

According to Walter Wünsche , the Gusle emerged from the medieval Byzantine instrumentation. As an old form of European string instruments, which applies to both the way of playing and the shape of the instrument, there are no literary and iconographic sources that could tell more about the origin of the instrument. As an instrument, the gusle is not versatile and its direct function in the accompaniment of the epic song has hardly given rise to the notationless tradition in the field of the farmers and shepherds of Montenegro in an epic world that was alive in a special social and historical situation to put the musical instrument in the foreground or to report on its origin. It is only a symbol for a small area in south-east Europe, where it is considered an old, but not primitive, instrument. According to Wünsch, based on the results of Alois Schmaus , and thus also identical to Svetozar Koljević's theory on the origin of epic folk poetry in Deseterac, the Guslenepik is younger than medieval court art, for which Wünsch sees the possibility of medieval epic art being scaled down World of the Peasants and Shepherds (Albert Bates Lord sees this contrary and assumes that the Deseterac poetry of the Guslen bards and the fifteen-line long poem of the Bugarštice were cultivated in parallel). Wünsch also assumes that the medieval minstrel taught the shepherds and peasants his art and also gave them the gusle. In particular, this suitability of the Gusle for the epic accompaniment can be derived from their construction material and shape. The sound quality of stroking the horsehair cover of the bow over the playing string of the gusle made of the same material is particularly suitable for undertoning long recitations. Together with its own voice, a homogeneous sound is created.

Both the design and the playing tradition refer to their origins in the "poet's fiddle" of the Arab Bedouin Rabābah , from which the Tuareg Imzad and the Ethiopian Masinko are believed to have descended. The Arabic and Balkan practice of recitative singing is linked in a striking similarity in the form and use of the respective instruments Rabābah and Gusle . The fiddle was therefore probably originally worn by migrating peoples from Central Asia to the Balkans and has been handed down in its original game practice, while the Arabs modified it for their own needs.

From the lyrical character of the poetry that is recited for the Rabābah , its use differs from the epic chants that are accompanied by the gusle . In today's typical urban playing practice of the Rabābah, the use of the middle finger, which, in contrast, forms one of the main tones in Guslen playing, is dispensed with in playing instruments . Due to the urban adaptation of the instrument, which originated from a former village milieu, the use of the middle finger in the Rabābah was eliminated before the 10th century, which, according to Robert Lachmann , can be assumed to be the last point in time for complete agreement between Rabābah and Gusle.

Literary and pictorial traditions

Although there were reports of musicians among the Southern Slavs by the Byzantines from the first half of the 7th century, the first written evidence of the use of the gusle is only available from the early 14th century. In the reign of Stefan Uroš III. Milutins reported to Teodosije about epic chants of classical ancient materials and the use of drums and guslen at the court of the Serbian king.

In the centuries that followed, the ten-syllable Serbian epic folk chants essentially integrated the stories about the battle of Kosovo into a practically coherent folk epic . With Serbian bards, this genre spread across the Central Dinaric countries to Hungary and Poland. Serbian gusla players themselves became known by name in the early modern period. The Hungarian lute player Tinódi reported that Dimitrije Karaman was the best among them. This form of instrument playing was then commonly referred to as “Serbian style” (in the 17th century as modi et styli Sarbaci .) Also the most important epic work of the Bugarštice genre, the forerunner of the ten-syllable folk epic, Makro Kraljević and his brother Andrijaš. which appears in a story by the Croatian poet Petar Hektorović in 1555 , this rhapsody by the fisherman Paskoje Debelja is referred to as a song in the so-called “Serbian manner”.

The first pictorial representations of the Gusle and the Guslenspiel can be recorded at the beginning of the 15th century. In the Kalenić monastery , in the lunette of the biforium on the northern outer conche of the monastery church, there is a bas-relief depicting the centaur Cheiron , who instead of a lyre plays either the gusle or the rebec . A human figure of a seated cast iron player can be found as a woodcut on the door of the Slepče monastery near Bitola in Macedonia. It is also dated to the 15th century.

A representation of a guslar playing a gusle is depicted on the icon of the life of St. Luke in the Morača monastery . Its creation dates from 1672–1673.

Regions of the Balkan heroic epic

The possibility of a common historical basis for the epic of south-eastern European Slavicism is conceivable, but the individual epics of the various Slavic peoples differ significantly. In addition to the significance of the historical experience in the Balkans, the hero song is bound to the landscape. The epic landscape forces people in the mountain forests or plateaus to form a union in the sense of a clan or a family status. The landscape forms the epic man and his ethnic life. According to Walter Wünsch, the need or the justification of a heroic song is necessary as a national and communal educational tool for people who, under certain conditions, live within a particularly creative environment. This means that the epic in the Balkans has been alive the longest where the building battle - either against economic interests outside the power or against the forces of nature - forces a common defense. This determines the sociological and economic shape of the people in the epic landscape. As a characteristic of the preservation instinct and close blood relationship, they form an essential marker for the ethnic affiliation in which the epic song not only takes on aesthetic purposes, but primarily an educational and ethical task in the preservation of tradition and ethnicity, as well as the individual tribes in the fight against a hostile one Encourage the environment. The epic tradition was only able to assert itself for a long time in a pastoral culture of the clans of the mountainous countries, since state order in peasant cultures in fertile lowlands replaced the clan with village peasantry and the epic did not survive there as part of the folk tradition. For Montenegro, Wünsch emphasized the unity of the landscape and the lifestyle of the people as the reason for the continued existence of the art of hero song at Gusle up to the present day.

In general, the gusle is played from its center in the Montenegrin-Dinaric area in northern Albania , Kosovo , south-west Serbia , south-central Dalmatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina as well as occasionally in central - west Bulgaria . The heartland of the Gusle game like the trochaic ten-syllable folk epic ( deseterac ) were the former patriarchal tribal areas of the Dinaric highlands of Herzegovina, Montenegro and northern Albania. This folk epic experienced its heyday in the illiterate world of the shepherds as well as the outlaws between the 16th and 19th centuries. Even until the first half of the 20th century, illiterate Guslen players found themselves in authentic form in the more backward regions of the Hochkarst.

Montenegro as the heartland of archaic song traditions

Specific natural conditions such as the historical circumstances had caused the isolation of the Montenegrin highlands for centuries and the slow evolution of the local culture. The clan formed the basic cell of society, which Vuk Karadžić illustrated: no city, no market, there is nothing in the whole country . Traces of feudalism had persisted in this region until the middle of the 19th century, until the end of the herd animal husbandry continued to be the general economic basis of the population. In addition to the natural spatial foundations, this was a direct function of the never-ending wars and was reflected as an ethnological manifestation in the heroic image of the Montenegrins . Oral transmission was linked to the fixed canon of tradition, which favored its long continuation and minimal change. Findings about the ancestors were imprinted in the memory over several generations. Montenegro developed into a "treasure trove" of very archaic folkloric forms.

The first major modernization took place in the 1870s after the Berlin Congress, but the transition from an agricultural to an industrial society took place until the Second World War. Schools were first introduced at that time, and free schooling began in 1907. At the beginning of the 20th century, only 15% of the Montenegrins were added to the urban population, whereby the term city is to be seen with strong reservations. The predominant part of the isolated mountainous country adhered to its archaic social order until well over the middle of the 20th century, when large sections of the population remained illiterate. The gusle not only had an elevated symbolic position in the patriarchal Montenegrin village society, it was, in addition to the rifle, its cultural characteristic, which was practically not missing in any house:

"Đe se gusle u kuću je čuju, tu je mrtva i kuća i ljudi"

"Where the gusle cannot be heard in a house, the house and the person are dead."

First Petar Perunović Perun , who like many other well-known Guslaren of Yugoslavia came from the Nahija Banjani or the Katunska Nahija (like Branko Perović ), in the old Herzegovina ( Stara Hercegovina ) and the old Montenegro ( Stara Crna Gora ), who was the first Montenegrin Guslar had a formal school education and was also a primary school teacher, modernized the traditional epic lecture through his classical music education acquired at a music school, in which he used modern elements of Western European musical voice training for the first time.

After Alberto Fortis from the Dalmatian hinterland published Guslen chants by the Morlaken , an exonym for the Slavic population of the Dinaric High Karst in Venetian Dalmatia, in his Viaggio in Dalmazia , these chants soon became an intellectual sensation in enlightened Europe, which had a romantic weakness for such popular poetry. Goethe got to know Forti's version of Hasanaginica in 1774/75 as a song from Morlackic and his own translation became anonymous as the lamentation of the women of Hasan Aga. Published in 1778 in Herder's Volkslieder as originating from Morlackian. Traces of this “sentimental Morlackism” intellectuals towards the epic poetry of the Southern Slavs were found in Rebecca West ( Black Lamb and Gray Falcon ) and especially in Milman Parry's Homer research in the twentieth century . The ethnologist and geographer Jovan Cvijić devoted a detailed profile study that has become an ethnological standard to the psychological dimension of the pagan ideals of life among the mountain dwellers of the Dinarides, which was also determined by the epic tradition , which since its first French edition (1917) to this day also the humanities debate in the The problem area of the Western Balkan willingness to use violence. The poetic idealization of the Dinaric folk epic experienced a late political idealization in which Cvijić defined the "Yugoslav ideal man" in the so-called Dinaric type ( Dinarski tip ) as a particularly well-fortified, freedom-loving mountain dweller who existed in his unadulterated tradition as the bearer of the Yugoslav ideology. In the inner workings and the psychological characterization of the heroes in the particularly extensive epics of Starac Milija and their portrayal of impulsiveness, Cvijić found a suitable illustration of the theory in the epic Milijas Ženidba Maksima Crnojevića .

"Epic laboratory" of Homer research

Musicological and literary-historical branches of knowledge were sustainably enriched through the investigation of both the musical function of the gusle in the narration of epics and the type and development of orally handed down verses in the genre of Serbo-Croatian epics. The Guslaren were also at the beginning, which led to the realization that the medieval development of European literature arose from the legacy of the literature of classical antiquity and the oral literary currents of the Middle Ages. The orally traditional heroic epic is a common literary heritage that is spread over large regions from Europe to Asia Minor and the Middle East to Central Asia and China

While the musicological investigation was long overshadowed by the literary historical preoccupation with the South Slavic heroic epic, current references focus on the musicological direction, especially with regard to music-pedagogical and folklore-preserving orientations of cultural and educational institutions in the respective countries.

In the 20th century, the South Slavic epic became a central study object for oral poetry, especially at the research institutions in Berlin, Prague and especially at Harvard, but also in the musicological sense and the function of the gusle as one of the oldest string instruments still in use. In 1912 and 1913, when researching the Guslars' songs, Matija Murko began recording the Guslars on the gramophone in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 1928, Gerhard Gesemann recorded the Guslaren Tanasije Vučić in the sound cabinet of the Prussian State Library, who had become famous for his victory at the second Guslaren singing competition in Yugoslavia. These recordings were deciphered phonologically in 1933 by Roman Ossipowitsch Jakobson in the verse of Desterac in the Serbo-Croatian hero song, and musically by Gustav Becking.

From views on the stylistic methodology and formulaic language technique of the orally transmitted Serbian-Croatian hero epic accompanied with the Gusle, essential conclusions in the literary history research on the Homeric question were gained. In particular, Milman Parry and Albert Lord collected the last original evidence of mostly illiterate Gusla players in Yugoslavia in the 1930s. The “Millman Parry Archive” was created from the sound recordings of these research trips at Harvard University , the most important sound recordings collection of South Slavic heroic songs, which Béla Bartók transcribed for the first time in 1940–1942 .

While the discovery of the Guslaren was one of the great unanswered riddles in literary history for the European literary and antiquity scene of the 19th century, the observation and analysis of their recitation and language technique was an essential aid in clarifying the authorship of ancient epics such as the Iliad and Odyssey . The English archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans also observed the Guslaren during the Herzegovinian uprising in 1875.

Folk history and language testimony

As an accompanying instrument for epic singing, the gusle has an essential meaning in the tradition of oral literature , the beginnings of which on the Balkan Peninsula go back to Homer's epics. The oral poetry of the Southern Slavs existed in three different literary contexts, in predominantly rural regions of the Balkans: in littoral Dalmatia with its rich Renaissance literature , with a strong Italian influence; in Serbia, where medieval literature continued into the eighteenth century; in Montenegro, where Russian literature, specifically that of the Russian monasteries, was influential, at least in a small circle of the elite. Even the earliest written versions of the epic song in the sixteenth century, however, show an already developed stylistic form that suggests that oral poetry was written earlier. Albert Bates Lord hypothetically names as early an origin as the time of the differentiation of the southern Slavs from eastern and western Slavs. While the renaissance literature in Dalmatia in its elitist form as an extension of the Italian Renaissance had no influence on the tradition of oral poetry, on the other hand the Dalmatian poets showed their knowledge of traditional folk poetry, as in Ivan Gundulić's Osman , without, however, the meter of the epics or to imitate the language. In the eighteenth century, art and folk poetry began to influence and flow into one another. In contrast, folk poetry practiced by illiterate singers in Montenegro survived into the twentieth century, with the remoteness of the Montenegrin highlands preserving such oral literary and song traditions until the early 1960s.

"Преживели после Косовског боја, повлачећи се у природне тврђаве Херцеговачко - Црногорске планине, понели су са собом ову кодирану поруку а гусле су биле и остале тај спајајући елемент, који је поруку сачувао, пренео и окупио ... У недостатку споменика од гвожђа и камена, гусле су те које преносе јединствено укрштање елемената словенске митологије, хришологије, хришигигиг ј "

“The survivors after the battle on the Blackbird Field, when they withdrew into the natural fortress of the Herzegovinian-Montenegrin mountains, took a coded message with them and the Gusle was and is this connecting element that kept, transmitted and collected this message ... in the absence of monuments made of iron and stone, the Gusle was and is the one that transmits the unique combination of elements of Slavic mythology, Christian belief and historical events. "

In the tradition of the epics, according to the historian Milorad Ekmečić, in a culture like the Serbian, which existed for a long time as an occupied society without schools and books, the most essential element of a national historical consciousness can be found: They are the most successful artistic achievement of their time, a The source of the clearest expression of the vernacular, and above all they are the oral tradition of the history of a people with a society scattered over various hostile empires ...

The Australian historian Christopher Clark , who on the occasion of the 100th outbreak of the First World War, published a widely acclaimed publication on the causes of the war in Die Schlafwandler , emphasizes the Guslen songs in the context of the meaning of tradition within Serbian folk history: These songs created an amazingly close bond between poetry, history and identity in the villages, towns and markets. Clark notes that the songs that ... were sung to the single-stringed Gusla, in which singers and listeners of new experienced the great archetypal moments of Serbian history, a typical phenomenon of Serbian culture and mark of the struggle for freedom from any foreign rule, in which a fictional one Serbia projected into a mythical past ... to be brought back to life.

A literary illustration can be found in Ivo Andric's novel The Bridge over the Drina , in which a Guslar, symbol of resistance, keeps memories alive. Even modern authors have emphasized this immediate effect of historical retrospect in the peculiar encounter in the Guslenspiel, such as the American poeta laureatus Charles Simic : After a while the poem and the archaic instrument from another world began to reach me and everyone else. Our anonymous poetic ancestor knew exactly what he was doing. This stubborn roar with the sublime lyrics of the poem touched the most primal point of our psyche. The old wounds were open again.

In the sociocultural context, the gusle and the epics presented with it, especially among the Serbs, assumed the function of a cultural weapon that had been filtered out as an essential part of their culture since the national rebirth of slavery by Islam in the 19th century. The importance of the writing of the orally transmitted poetry by Vuk Karađić into the recently reformed Cyrillic alphabet lay in the monumentalization of folk literature, which, according to Tomislav Longinović, constantly overwhelms the present as a vision of the past and directs the future backwards.

Even after the liberation from the Ottoman yoke (1816), the discourse about foreign rule and the ruled remained a fundamental motivation for the Guslar people. As an agnostic vision, the Guslarians in the epics combined a ritual catharsis of the collective burden, in which the injured but at the same time heroic people continued to sing. Thus, the endless repetition of the ritual sacrifice of the dead in the battle on the blackbird field was born into these epics , which, even after redemption from Islamic dominance, prepared the male population precisely to continue realizing this death in life for the country. Basically, this version of the narrative of patriarchal notions of dominance and submission persisted in rural patriarchal layers of the Dinaric Highlands, while more educated urban layers saw the epics as a source of pride and identity.

The Slav peasant population, who remained on the verge of national developments, continued to see hope in the epics to free themselves from their backwardness.

With the outbreak of the Balkan Wars, many of the soldiers of the Serbian army, who came from the rural milieu, took their Gusle with them to the battlefields against the Ottomans. The Gusle thus returned to the context of historical events. During the First World War, not only later well-known Guslars like Petar Perunović Perun played as soldiers in the breaks in the fighting for the soldiers in the trenches during the Battle of Cer , Battle of the Kolubara , Battle of Kajmakčalan , Veternik in the Battle of Dobro Polje , accompanied Guslen players even the withdrawal of the Serbian army via Albania to Greece. Petar Perunović Perun, who was still playing for the soldiers on the Salonika Front, was summoned to the United States for the recruitment of Serbs abroad, where he was among others in front of the physicists Nikola Tesla and Mihailo Pupin with the Gusle for supporting the Entente in Macedonia advertised. The soldiers led the Guslen to war and brought them back home with the wounded after the expulsion. In the Ethnographic Museum Belgrade you can find guslen that were worn by the Serbian troops in the Balkan Wars and World War I. A special historical instrument is the gusle of an invalid, which he had made from a soldier's helmet in the French military base Bizerta in Algeria and which can be found today in the Belgrade Ethnographic Museum as a special historical exhibit from the First World War. The gusle was supposed to strengthen the soldiers' morale. Guslaren like Petar Perunović played on the front lines themselves. Even Tesla, who heard Perunović in New York in 1916, was emotionally moved by the epic lecture Stari Vujadin by Perun and, after the latter had finished the lecture, said: The gusle is the greatest power to conquer the soul of a Serb . Another important Serbian emigrant, Pupin, cultivated his memories of the epic power of the Guslen lectures and ordered a bas-relief with the subject of Guslar Filip Višnjić, a replica of which he later bequeathed to the grammar school in Bijelina to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Višnjić's death.

In Montenegro, epic creativity also experienced multiple echoes within Guslen's art through the historical events of the First World War and in particular through the events of the Battle of Mojkovac . Hadži Radovan Bečirović Trebješki, who volunteered to take part in the Battle of Mojkovac fought between the Montenegrins and the Austro-Hungarian army in the snow-covered valley of the Tara on Christmas Day 1916, also created the main dramaturgical and expressive work in the modern Guslen epic in the theme of the First World War forms the Serbian-Montenegrin national epic in the 20th century ( Bitka na Mojkovcu , 1927). Bečirović had started his epic-poetic confrontation as an Austro-Hungarian prisoner in 1917 in the Nađmeđer camp in what is now Slovakia, but was already familiar with the Gusle in his earliest biography. Through Bečirović, the epic ten silver of the Southern Slavs experienced a change in the form of a rhyme addition, which all predecessors had avoided.

The epics on Gusle also shaped leading political and social classes in Montenegro and Serbia after the Second World War: Milovan Djilas , Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić also publicly showed their affinity for the Guslenspiel. Prince Njegoš, who wrote poetry in the Serbian vernacular in Desterac, described in the national epic Bergkranz (1847) in the words of Bishop Stefan a function of the Gusle as the "bearer" of historical messages, which can still be found in later generations; the chants of the Guslaren should stimulate action to be immortalized in the "immortality" of an epic:

If man attains an honest name on earth,

his being born then wasn't at all in vain.

But without his honest name - what is he?

Generation which was made to be sung,

muses will vie for many centuries

to weave for you garlands worthy of you.

Your example will teach gusle singers

how one should speak of immortality!

Social function

It serves primarily as an accompaniment to the epic song of the South Slavic Guslaren and, along with the rifle, was a sacred symbol of all freedom fighters in the Dinaric mountains .

Before the liberation of the southern Slavs and Bulgarians from Ottoman rule, the gusle had two main functions:

- Glorification, reinforcement and preservation of the traditional “epic type of human being” in an environment alien and hostile to this type

- Keeping the thought of the necessary liberation struggle alive.

Today, after the liberation, the hero song no longer has to call for the struggle for freedom. The modernization of the traditional, strongly patriarchal society also led to a different attitude to the song and its performance. So it is no longer played in front of relatives, which means that the art of performing has to be completely adjusted to the impression of a general listener and has to adapt to their aesthetic views and artistic demands. Because of this, today's heroic songs often deal with national themes.

The gusle had a prominent function in the social environment of the Balkan pasture farming . Especially in the most backward high regions of the southeast Dinarides between the Maglić, Durmitor and the Prokletije / Bjeshket e Nemuna, d. H. from eastern Herzegovina via Montenegro to northern Albania. In the strictly patriarchal societies of the highland inhabitants, the gusle was exclusively a men's instrument, young women were urged to kiss a guslar's hand when a guslar appeared in the house and it has been reported many times that women in Montenegro used to sing about a (male) Heroes had to stand. Compared to Zorka Milich, who interviewed 100-year-old women in Montenegro, Ljubica, a Montenegrin who was estimated to be between 112 and 115 years old, told how common the game of guslens once was in the deprived mountains: We always had a lot of guests, men who were sitting around eating and drank. They played the gusle and sang. We loved to listen to them. I can still remember some of the songs. The young people don't care about these old things. I'm sorry It is important to maintain our traditions. Too much blood was shed for it. Suffered too much. The country wouldn't be called the Black Mountain if it wasn't black. It is soaked in blood, in poverty in death. We don't know anything about comfortable living. We never had one .

Due to the similar socio-cultural context is the ratio of the Albanians in northern Albania the circulation area of the rhapsodists (rapsode) of Lahuta. Mostly they were given within the family environment for visitors or for family celebrations as a tribute to the guests. We sang these songs mostly in the winter nights when we gathered in the guest rooms where the "burrat kreshnjake" (brave men) stayed and gathered, but also in the mountain pastures and in the mountains where we wandered with the herds that were in the Shadows from oaks or near springs of mountain pastures of Daberdol, Kushetice and others .

The main themes of the various epics known as kange te mocme (old songs), kange trimash (heroic songs ), kange kreshnikesh (songs of the border warriors ), kange te Mujit e Halilit (songs of Muji and Halili), are battles for pasture land and its defense, battles with Monsters, theft from young women of the enemy. A pre-Ottoman origin from the choice of topic has been suggested. Gjergj Fishta's (1871–1940) famous work Lahuta e Malcís , which is about the Albanians' struggle for freedom, is in the tradition of heroic songs .

At the beginning of the 1980s, the number of epic singers (rapsode) has decreased drastically, at the same time the number of mastered song texts has thinned out significantly. The main reason emphasized is the competition of new song types, with radio and television stations removing Lahuta lectures from their programs.

Religious message

In its older forms, the ornamentation of the gusle was entrusted to it as a carrier of messages that were important for the collective, regardless of the songs that were played. The original Guslen are characterized by pagan symbols, the newer ones by a mixture of pagan symbols that are often rooted in national history.

The gusle should not only be heard, it should also be seen through its elaborate decorations. Guslar events are still offered today as visual art, with great attention being paid to the external design of the lecture.

The pagan ideas use the register of animal representations as well as mythological beings. Here it is the decorations of the head with horse, ibex, ram, snake, falcon, eagle and horse. In the magical and mythical way of thinking of the southern Slavs, these animals are chthonic marks and in the imagination they are filled with the realm of the dead and contact between this world and the next. From the representation of the chthonic animals as ornaments, it is assumed that the songs that are sung with the accompaniment of the Gusle relate to life after death and are intended to establish ritual connections to the dead ancestors. At the beginning of the 20th century, the image program was expanded to include the figures of national history, and Matija Murko mentioned depictions of Serbian kings and emperors such as Tsar Dušan, King Peter I of Yugoslavia, Miloš Obilić or Kraljević Marko during his research trips from 1930–1932.

Political history

As a symbolic instrument, the gusle assumed an increasing political function, especially during nationalist movements in the 19th and 20th centuries. This statement was already valid in Serbia for the wars of liberation under Karađorđe and for the government of Miloš Obrenović, who played gusle himself. This becomes clear in the revolutionary national movements in the age of Serbian Romanticism, especially in the poems of Prince-Bishop Petar II. Petrović Njegoš. In the early epic poem Njegoš, "Nova pjesna crnogorska o vojni Rusah i Turaka, početoj u 1828 godu" ( "New Montenegrin song of the War between the Russians and the Turks, Begun in 1828" ), which is already linked to the world of literature , the romantic cult of Gusle in association with Serbian nationalism in the wars of liberation from the Turks by invoking Gusle and Vila emphasized in the first lines :.

Nova pjesna crnogorska

B'jelo vilo, moja divno drugo,

svedi, drugo, sve u Gusli glase,

tvoje glase au Gusli jasne,

da ih čuje bunk razumije,

razumije drago aku mu je.

Srbalj brate, ova pjesna za te,

ti češ čuti, ti je razumjeti

ponajprije od ostalih svije.

New Montenegrin song

White vila, my wondrous comrade,

bring together, comrade, all voices into the gusle,

your clear voices into the gusle,

that he who understands may listen,

understands if it pleases him.

Brother Serbs, this song is for you,

you will listen, you will understand

first of all others.

The political design concerned both the appearance of the gusle and the content of the songs performed at the gusle. The Guslen ornaments also increased in type and extent, and additional medallions and heraldic symbols mean that some Guslen soon look like mobile " iconostases ". After the Second World War, Guslen were decorated with decorations of the Yugoslav Partisans and the coat of arms of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. In 1961, for example, Tito received a stone gusle depicting the events of the Battle of the Sutjeska . This still represents one of the special exhibits in the Museum of the History of Yugoslavia . The exhibition site in the Old Museum is in the immediate vicinity of Tito's mausoleum in the House of Flowers ( Kuća cveča ).

As a symbol of legitimation for power in the name of the people, the gusle became important among leading rulers in socialist Yugoslavia and Albania. Milovan Djilas , once the third man in the cadre of officials of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, used to play Gusle and Tito, as President, not only liked to listen to Guslen players, he also invited them, for example, to the state visit of Egyptian President Nasser to a lecture at the Tjentište Memorial Complex on the Sutjeska one where he had asked for a song to Bajo Plivljanin.

The former Albanian communist leader Enver Hoxha also used Albanian folklore to demonstrate closeness to the people. Several Lahuta songs were also dedicated to Hoxha, such as in the anthology Gesund may you be, Enver Hoxha (Enver Hoxha tungjatjeta) the Guslen songs Enver Hoxha led us (Enver Hoxha na ka pri), and about Enver is also talked about above (Per Enverin malet kuvendjne).

Song corpus

Writing

The writing of the South Slavic Epic Chants can be set for the end of the 15th century at the earliest. A fragment of a Bugarštice was noted in 1497 in the Italian city of Giaoia del Colle on the occasion of the visit of the Queen of Naples Isabella Del Balzo on May 31, 1497 by the Italian court poet Rogeri di Pacienzia in the epic court poem Lo Balzino . It was performed there by a colony of Slavic emigrants to dance and music on the occasion of the Queen's visit and is part of the group of the so-called despot epics, a corpus of the post-Kosovo cycles, in which the historical event of Janos Hunyadi's capture by Đurađ Branković was thematized:

Fifty years later, in 1555, the Croatian poet Petar Hektorović made the most important epic work of the Bugarštice genre with an inscription in the so-called "Serbian manner" by the fisherman Paskoje Debelja during a boat trip on the island of Hvar . Makro Kraljević and his brother Andrijaš is the classic tale of fratricide .

A compatriot of Hektorovićs, Andrija Kačić Miošić (1704–1760), a Franciscan, published a history book in Venice in 1756 in Venice under the title Razgovor ugodni naroda slovinskoga , which was disguised as a collection of epics. The book became so popular that a second edition followed in 1759 and Kačić himself planned a third. After Kačić's book was distributed in all Croatian countries including the western regions of Slovenia, it soon reached Bohemia and Slovakia. It was spread over Serbia and Macedonia only two years after the publication of the second edition to the Holy Mount Athos.

Kačić's idea was to use ten-syllable verses for the simple Slavic rural population, who otherwise had no access to scholarly books due to their lack of education, for the first time a book about history written in a Slavic language in its own idiom as a hymn book with songs written in ten-syllable verses to write. Kačić saw himself as a historian, but his work is now generally seen as that of a poet. However, of the 100+ just published in the second edition in Kačić's book, only three were folk epics, while some of the songs contained parts of folk epics such as the Hasanaginice, a Muslim family drama from the Imotski area .

A German became the first to write down a large collection of Bugarštice, which was already widespread in the 18th century. In elaborate Cyrillic Habsburg script he had written down ten-syllable epic and heroic folk songs in Slavonia in the so-called "Erlanger Manuscript" around 1720, but was only able to do so without distinguishing between stressed and unstressed consonants and often without individual words in Serbo-Croatian to be able to distinguish correctly. The first well-known ten-syllable poem of the southern Slavs that was received internationally was Die Frau des Hasan Aga ( Hasanaginica ), which in a German translation of "Asan-Aginice" recorded in Italian by Alberto Fortis in Dalmatia in 1774 by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe 1775 in Johann Gottfried Herder's Volkslieder was published. The Goethe translation was soon translated into English by Walter Scott , Prosper Mérimée into French and Alexander Pushkin into Russian.

In the enthusiasm for folk songwriting at the time, which saw Ossian significance in the Serbo-Croatian epics , with an often associated romantic enthusiasm for the ethnographic and political conditions of the Balkans, it is also understandable that the European literary scene appeared on the first publications by Vuk Stefanović Karađić's collection of Serbian-Croatian oral epic poetry from 1814 reacted so extremely benevolently.

Vuk Karađić's collection

When Karađić's collection was first published in print, Jakob Grimm , the most important German comparative folk song researcher at the time , compared Serbian and German heroic songs and emphasized the pure and noble language for the former, recommending Serbo-Croatian to German students of Slavic languages for reading to learn the "excellent songs". He convinced Therese Albertine Louise von Jacob, a young woman who spoke a little Russian and was a great admirer of Goethe, to translate some of the songs into German. Their translation, Folk Songs of the Serbs (1825) immediately became a minor literary classic. In addition to Germany, the Serbian folk songs were received intensively in France and England, in France by Prosper Mérimée, in England by journalism that dealt with the embodiment of the national character of the songs in the context of political and military questions of the Middle East and in particular with the Homeric meaning of the Serbian-Croatian Oral Poetry as a Subject of International Scholarship. To this day, this collection represents the main part of the South Slav epic epic and the largest collection of folk songs in European literature. For Geoffrey NW Locke, The Epic Poetry of Serbia is the richest oral epic material in any single European language . Peter Levi , poet, literary historian, critic and former professor of poetry at Oxford University confirms that:

“They are one of the most powerful and unrecognized verse rivers in Europe. They carry their own taste in their native mountains, the strength of their troubled times and the moral greatness of an orally conveyed type of poetry that is justifiably called heroic. "

structure

Vuk Karadzić divided the corpus of the oldest Serbian folk songs into three periods:

- the corpus of epics that were written before the Blackbird Field Battle (epics relating to events in the time of Tsar Stefan Uroš IV. Dušan and in particular the non-historical Marko Kraljević cycle)

- the historical epics of the Amselfeldschlacht , which make up the central part of the epic folk songs (Lazar cycle)

- the epics that were written shortly after the Battle of the Blackbird and deal with the despots.

With the liberation struggle from Ottoman rule, epics on outlaws ( Hajduken and Uskoken cycle) as well as descriptions of battles emerged ( Mali Radojica - Little Radojica, Mijat Tomić , Boj na Mišaru - Battle of the Mišar, etc.)

Well-known epic songs are, for example, the heroic songs:

- from the pre-Kosovo cycle: ( Zidanje Skadra - the building of Skadar / Shkodra, Ženidba Dušanova - Dušan's wedding, etc.)

- to prince Marko ( Prince Marko and Falke , Prince Marko and Mina of Kostur , Prince Marko and Musa Kesedžija et al.)