Carolingian book illumination

As Carolingian book illumination which is Illumination of the 8th to the late 9th century referred to the end that the Frankish Empire was born. While the previous Merovingian illumination was purely monastic, the Carolingian originated from the courts of the Franconian kings and the residences of important bishops.

The starting point was the court school of Charlemagne at the Aachen royal palace , to which the manuscripts of the Ada group are assigned. At the same time, and probably in the same place, the palace school, whose artists were influenced by Byzantine , existed. The codices of this school are also called the group of the Vienna Coronation Gospel according to their main manuscript . Despite all the stylistic differences, both painting schools have in common the direct examination of the formal language of late antiquity as well as the effort to achieve unprecedented clarity of the side image. After the death of Charles, the center of illumination moved to Reims , Tours and Metz . While the court school dominated in the time of Charles, the works of the palace school were more popular in the later centers of book art.

The heyday of Carolingian illumination ended in the late 9th century. In the late Carolingian period a Franco-Saxon school developed , which again increasingly took up forms of the older insular book illumination , before a new era began with Ottonian book illumination from the end of the 10th century.

Basics of Carolingian book illumination

Temporal and geographical framework

The allocation of Carolingian art to an epoch is inconsistent: it is sometimes viewed as an art epoch in its own right, but more often combined with other styles from the 5th to 11th centuries as early medieval art or with Ottonian art as pre-Romanesque , sometimes also as early Romanesque Romanesque epoch included. Carolingian art was strongly tied to the respective ruling house and was limited to the Carolingian domain , i.e. to the Franconian Empire . Art regions that were outside of this area are not counted as Carolingian art. A special case is the Longobard Empire, which Charlemagne was able to conquer in 773/774, but which continued its own cultural traditions that had a strong influence on Carolingian art. Conversely, the impulses of the Carolingian Renaissance also worked in Italy, especially in Rome .

The election of Pippin the Younger as King of the Franks in 751 marks the beginning of the Carolingian royal dynasty, but an independent Carolingian art did not begin until Charlemagne, who had been the sole ruler of the Frankish Empire since 771 and was crowned emperor in 800 . The first magnificent manuscript commissioned by Karl between 781 and 783 was the Godescalc Evangelistar . After the death of Louis the Pious , the successor to Charles, the empire was divided into three parts in the Treaty of Verdun in 843, West and East Franconia and Lotharingia . Lotharingia experienced several further partitions in the following decades, in which some areas fell to the west and east of France, while others in Lorraine , Burgundy and Italy became independent kingdoms and duchies.

With the death of Ludwig the child in 911, the line of the East Franconian Carolingians became extinct. Konrad the Younger from the family of the Konradines was elected as the new king . After his death, the great Franconians and Saxons elected Heinrich I in 919 as King of East Franconia. With the transition of the royal dignity to the Saxon Liudolfinger , who were later called Ottonen, the focus of art production also shifted to Eastern Franconia, where Ottonian art developed its own distinctive character. In western France, after the death of Louis the Lazy in 987 , the royal dignity passed to Hugo Capet and thus to the Capetian dynasty . The heyday of Carolingian art ended in the entire Franconian region as early as the end of the 9th century, the later sparse and less important works mostly reverted to older traditions.

Artist and client

Whereas in the Merovingian era only monasteries were responsible for book production, the Carolingian renaissance started from the court of Charlemagne. The Godescalc Evangelistary, the Dagulf Psalter and an unadorned handwriting attest to Karl in dedicatory poems and colophons as a client. Even among the successors of Charlemagne, short-lived workshops were tied to the courts of the Carolingian emperors and kings or to the important bishops who were closely associated with the royal court. Only the monastery of Tours remained productive for decades until its destruction in 853.

Most of the liturgical books were intended for the royal court. Some of the most valuable codices served as gifts of honor, for example the Dagulf Psalter was planned as a gift from Charles to Pope Hadrian I , even if it was no longer handed over because of Hadrian's death. A third group of manuscripts was produced for the most important monasteries in the empire in order to carry the religious and cultural impulses emanating from the imperial court into the empire. The Gospels of Saint-Riquier were intended for Charles' son-in-law Angilbert , the lay abbot of Saint-Riquier , and in 827 Louis the Pious donated a Gospel ( Gospels from Soissons ) from the court school of Charlemagne of the Saint-Médard Church in Soissons . Conversely, the Touronic monastery under Abbot Vivian gave Charles the Bald the Vivian Bible in 846 , who probably donated it to Metz Cathedral in 869/870 .

Few early medieval illuminators can be identified by name. In an illustrated Terence manuscript, perhaps from Aachen, one of the three painters, Adelricus, hid his name in the gable ornament of a miniature. According to his own statements, the learned Fulda monk Brun Candidus , who had spent some time at the Aachen court school under Einhard , painted the western apse of the Ratgar basilica , consecrated in 819, above the Bonifatiussarcophagus in the Fulda monastery . He could have played an important role in the Fulda painting school in the first half of the 9th century. It is therefore hypothetical, but not improbable, that he also worked as an illuminator and illustrated Abbot Eigil's vita, which he wrote himself .

The scribe of a manuscript used a dedication poem or a colophon more often than the painters. The Godescalc Evangelistary and the Dagulf Psalter were named after the writers of the manuscripts. Both refer to themselves as Capellani , which suggests that the scriptorium of Charlemagne's court school was connected to the chancellery . In the Codex aureus of St. Emmeram , the monks Liuthard and Beringer name themselves as scribes. The smaller a scriptorium was and the lower the demands of the illumination, the more likely it is that the scribe also carried out the illumination .

The book in Carolingian times and its tradition

The book, produced in a labor-intensive process with expensive materials, was an extremely valuable luxury item. All Carolingian manuscripts are written on parchment ; the cheaper paper did not reach Europe until the 13th century. Particularly representative magnificent manuscripts, such as the Godescalc Gospels, the Gospels from Soissons , the Coronation Gospels , the Lorsch Gospels and the Bible from St. Paul were written with gold and silver ink on purple-colored parchment. Their book covers were adorned with ivory tablets, which were framed by goldsmith's work adorned with precious stones . The miniatures were dominated by opaque color painting , the - mostly colored - pen drawing was less common .

Around 8,000 manuscripts from the 8th and 9th centuries have survived. How big the book losses are due to Norman incursions , wars, iconoclasms , fires and other violent causes, to disregard or reuse of parchment as a raw material , can hardly be estimated. Preserved book directories provide information on the size of some of the largest libraries. The book inventory of the St. Gallen monastery rose from 284 to 428 in Carolingian times, the Lorsch monastery owned 590 manuscripts in the 9th century and the monastery library in Murbach 335 manuscripts. One can get an idea of the size of private libraries from wills. The 200 codices that Angilbert bequeathed to his Saint-Riquier monastery, including the Saint-Riquier Gospel Book, were probably one of the largest libraries. Eccard von Mâcon bequeathed around twenty books to his heirs. The size of Charlemagne's library, which was sold after his death in accordance with his will, is not known. All the essential tangible works and numerous illuminated manuscripts were gathered in the Aachen library, including many Roman, Greek and Byzantine books.

Most of the manuscripts were not illuminated at all, and a small part was not very sophisticated. As a rule, only the few main works of Carolingian book illumination find their way into art historical literature . Valuable magnificent manuscripts - especially when it came to liturgical books - always enjoyed preferential treatment. The most exclusive codices were not used literature, but belonged to the church treasury as liturgical implements or were mainly used for representative purposes, as the often slight signs of use suggest. Illustrations on the very durable parchment are also well protected from external influences in a closed book, and for a long time the codices were not kept on open shelves but in chests, more rarely in lockable cupboards. The illustrated manuscripts from Carolingian times have survived in relatively large numbers, and many miniatures have survived the past twelve centuries in a very good condition. Most of the surviving illuminated manuscripts have been preserved in their entirety; fragmentary records are rare. The fact that a significant number of lost illuminated manuscripts can nonetheless be reckoned with is proven by later illustrations, which are the aftermath of non-preserved original images. In some cases there are no longer existing illuminated codices: such as a “golden psalter” by Queen Hildegard from the early days of Carolingian illumination.

The easily meltable golden book covers , on the other hand, only withstood access to later times in a few cases. The ivory plates of the bindings are more often preserved, but in no case in connection with the codex which they originally decorated. The five plates of the Lorsch Gospel are now in the Vatican Museum . At least the lower ivory plate is not a Carolingian work, but a late antique original, as an inscription on its back shows. The only ivory tablets that can be dated with certainty are those of the Dagulf Psalter, which are described in detail in his dedication poem and can thus be identified with two tablets in the Louvre in Paris . Illumination was closely related to ivory carving. The small-format, easily transportable works of art played an important role as mediators of ancient and Byzantine art. In contrast, only a few fragments of the Carolingian large sculpture have survived, works of goldsmithing have survived somewhat better. In connection with book illumination, the book cover of the Codex aureus of St. Emmeram from the court school of Charles the Bald is of particular interest.

Due to the relatively good tradition, Carolingian book illumination and small sculptures are more important for art history than those of other epochs, since all other art genres from the Carolingian period are extremely poorly preserved. This applies in particular to monumental wall painting , which, as in the later Ottonian and Romanesque times, was the leading genre of Carolingian painting. It can be assumed that every church as well as the palaces were painted with frescoes ; the minimal preserved remains, however, no longer allow a clear idea of the former splendor of the pictures. Also mosaics in ancient tradition played a role; the Palatine Chapel in Aachen was adorned with a magnificent dome mosaic.

Precursors and Influences

Merovingian book illumination

The Carolingian Renaissance developed in a marked “cultural vacuum” and its center became Karl's residence in Aachen. The Merovingian Illumination , named after the Carolingians preliminary ruling dynasty in the Frankish Empire, was purely ornamental . The initials constructed with rulers and compasses as well as cover pictures with arcades and set cross are almost the only form of illustration. From the 8th century onwards, zoomorphic ornaments appeared, which became so dominant that, for example, in manuscripts from the women's monastery in Chelles, entire lines consist exclusively of letters made from animals. In contrast to the simultaneous insular illumination with rampant ornamentation, the Merovingian strove for a clear order of the sheet. One of the oldest and most productive scriptoria was that of Luxeuil Monastery , founded in 590 by the Irish monk Columban , which was destroyed in 732. The Corbie Monastery, founded in 662, developed its own distinctive style of illustration, Chelles and Laon were further centers of Merovingian book illustration. From the middle of the 8th century, this was strongly influenced by the island illumination. A gospel book from Echternach proves that Irish and Merovingian scribes and illuminators worked together in this monastery.

Insular book illumination

Up until the Carolingian Renaissance, the British Isles were the refuge of Roman-early Christian tradition, which, however, by mixing with Celtic and Germanic elements had produced an independent insular style , whose sometimes violently expressive, ornament-preferring and strictly two-dimensional character ultimately resulted in its anti-naturalism antiquated form language. Only in exceptional cases did the insular book illuminations retain classic design elements, such as the Codex Amiatinus (southern England, around 700) and the Codex Aureus of Stockholm (Canterbury, mid-8th century).

The European continent was strongly influenced by the island monastic culture as a result of the iro-Scottish mission , which originated in Ireland and southern England . In the whole of France, Germany and Italy, Irish monks founded monasteries, the " Schottenklöster ", in the 6th and 7th centuries . These included Annegray , Luxeuil, St. Gallen , Fulda , Würzburg , Sankt Emmeram in Regensburg , Trier , Echternach and Bobbio . A second Anglo-Saxon missionary thrust followed in the 8th and 9th centuries. Numerous illuminated manuscripts reached the mainland via this route, and their writing and ornamentation had a strong influence on the respective regional formal languages. While book production in Ireland and England largely came to a standstill from the end of the 8th century due to the raids of the Vikings , book illuminations continued to emerge on the continent for a few decades in the island tradition. In addition to the works of the Carolingian court schools, this branch of tradition remained alive and shaped the Franco-Saxon school in the second half of the 9th century , but the court schools also adopted elements of island illumination, especially the initial page.

Antiques reception

The recourse to antiquity was the main characteristic of Carolingian art. The programmatic adaptation of ancient art was consistently based on the late Roman Empire and fitted into the basic idea, known as renovatio imperii romani , of claiming the legacy of the Roman Empire in all areas. The arts were an integral part of the intellectual currents of the Carolingian Renaissance .

The study of original works, especially in Rome, was of great importance for the reception of ancient art. For the artists and scholars of the north, who did not know Italy firsthand, works of late antique book illumination played an important mediating role, because apart from the small sculptures only the book made it directly to the workshops and libraries north of the Alps. There is evidence that the scriptorium in Tours also used ancient originals as models. Figures from the Vergilius Vaticanus , which was in the possession of the Touronic library, were copied and can be found in the Bibles. Other ancient manuscripts in the possession of the important library were the Cotton Genesis and the Leo Bible from the 5th century. Many lost illustrated books of late antiquity can only be made accessible today through Carolingian copies.

Byzantium

In addition to the original works, Byzantine book illumination conveyed the ancient legacy that had been productively continued there in a largely unbroken tradition. However, the Byzantine iconoclasm , which suppressed the religious cult of images between 726 and 843 and caused a wave of image destruction, marked an important break in the continuity of tradition. With the exarchate of Ravenna , Byzantium had an important bridgehead in the west until the 8th century. Artists who had fled Byzantium to avoid persecution because of the ban on images also promoted Roman art. Charlemagne drew artists to his court from Byzantine Italy, who created the works of the palace school.

Italy

Italy was not only important as a mediator of Classical and Byzantine art. Rome experienced a particularly pronounced renovatio movement that was related to the Carolingian renaissance in the Frankish Empire. Due to its role as the protector of the papacy , the Frankish Empire was closely connected to Rome, which despite its decline since the migration period was still considered the caput mundi, the head of the world. In the years 774, 780/781 and on the occasion of his coronation as emperor in 800, Charlemagne himself stayed in Rome for a long time.

Since he had conquered the Longobard Empire in 774 , rich currents of culture flowed north from there. The illuminations of the court school of Charlemagne show similarities with Longobard works and even the idea of commissioning magnificent manuscripts, which was new for the Franconian kings, could go back to models at the Longobard court in Pavia .

Development of Carolingian book illumination

For chronological development and topographical distribution, see the overview of the main works of Carolingian book illumination .

There is no uniform Carolingian style. Instead, three branches have developed that go back to very different schools of painting. Two court painting schools were active at the Aachen court of Charlemagne around 800 and are known as the "court school" and "palace school" respectively. On this basis, distinctive workshop styles developed, especially in Reims, Metz and Tours, which rarely remained productive for more than two decades and were heavily dependent on the respective tradition of the scriptorium, the size and quality of the existing library and the personality of a donor . A third style, largely independent of the court schools , continued insular book illumination as a Franco-Saxon school and dominated book illumination since the end of the 9th century.

Both courtly painting schools have in common the direct examination of the formal language of late antiquity as well as the effort to achieve unprecedented clarity of the side image. While island and Merovingian book illumination was characterized by abstract braided patterns and schematic animal ornaments, Carolingian art took up classic ornaments again with the egg stick pattern , palmette , vine tendril and acanthus . In figurative painting, the artists sought a comprehensible representation of the anatomy and physiology, the three-dimensionality of bodies and spaces as well as light effects on surfaces. The element of probability in particular overcame the previous schools, whose portrayals, unlike their abstract pictures, were "unsatisfactory, if not to say ridiculous".

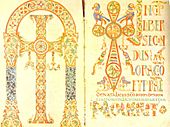

The clear order of book illumination was only part of the Carolingian reformation of the book industry. It formed a conceptual unit with the careful editing of sample editions of the biblical books and the development of a uniform, clear script, the Carolingian minuscule . In addition, the entire canon of ancient writings appeared - especially as a decorative and structural element, such as the uncial and the semi- uncial .

Types of illustrated books and iconographic motifs

The combination of text and image made the book particularly important as an instrument for spreading the renovatio idea in the empire. The gospel book was at the center of the reform efforts for a uniform regulation of the liturgy . The psalter was the first type of prayer book. From around the middle of the 9th century, the spectrum of books to be illustrated expanded to include the full Bible and the sacramentary . The execution of these liturgical books was expressly entrusted in the Admonitio Generalis by 789 only to experienced hands, perfectae aetatis homines .

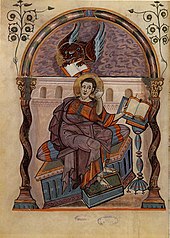

The main decorations of the evangelists were depictions of the four evangelists . The Maiestas Domini , the image of Christ enthroned, appears rarely at the beginning, while images of Mary and other saints hardly ever appear during the entire Carolingian era. In 794 the Synod of Frankfurt had dealt with the Byzantine iconoclasm and banned the worship of images , but assigned painting to the task of instruction and instruction. The Libri Carolini , the author of which was probably Theodulf von Orléans , is considered the official statement of the circle around Charlemagne in this sense . An early Maiestas Domini depiction appears in the Godescalc Gospel in 781/783, a few years before this position was determined. After a Franconian synod loosened the regulations in 825, the range of subjects worth depicting expanded, especially in the schools of Metz and Tours. Since the middle of the 9th century, the motif of the Maiestas Domini was a central motif, especially in the Touronic Gospels and Bibles, and now, together with the evangelist pictures, belonged to a fixed iconological cycle of illustrations. The motif of the fountain of life appears for the first time in the Godescalc Gospel Book , which is repeated in the Soissons Gospel Book. Another new motif was the adoration of the Lamb . An integral part of the Gospels are canon tables with arcade frames. Characteristic of the court school of Charlemagne were throne architectures that are missing in the works of the palace school and the schools of Reims and Tours. The illuminators adopted the initial page from the island illumination .

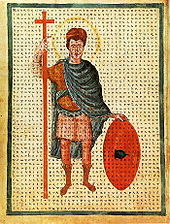

A central motif since the time of Louis the Pious has been the image of the ruler, which appears mainly in manuscripts from Tours. With regard to the programmatic appropriation of the Roman heritage in the sense of a renewal and thus the legitimation of Carolingian rule, this motif was of particular importance. By comparing the images with descriptions in contemporary literature, such as Einhard's Vita Karoli Magni and Thegans Gesta Hludowici, it can be concluded that these are typological portraits in the spirit and modeled on Roman rulers, enriched with naturalistic, portrait-like elements. The sacred meaning of the imperial office is thematized in almost all Carolingian images of rulers, which accordingly appear especially in liturgical books. Often the hand of God appears over the rulers. The sacred connotation becomes clearest in a depiction of the nimble , cross-bearing Louis the Pious as an illustration of De laudibus sanctae crucis by Rabanus Maurus .

In addition to the liturgical books, relatively few secular books were illustrated, among which copies of late antique constellation cycles played a special role. An Aratea manuscript from around 830-840 protrudes from these and was later copied several times. The Bernese Physiologus (Reims, around 825–850) is the most important of a series of illustrated manuscripts from the Physiologus' theory of nature . An important textbook for the Middle Ages was Boëthius ' De institutione arithmetica libri II, which was illuminated for Charles the Bald in Tours in the 840s. Among the illustrated works of classical literature are especially manuscripts with comedies by Terence , which were mentioned around 825 in Lotharingia or in the second half of the 9th century in Reims, as well as a manuscript with poems by Prudentius , possibly from the Reichenau monastery and in the last Third of the 9th century was illustrated.

Everyday scenes are particularly numerous embedded in psalm illustrations , for example in the Utrecht, the Stuttgart and the Golden Psalter of St. Gallen . Other books, such as a martyrology by Wandalbert von Prüm (Reichenau, third quarter of the 9th century) occasionally contain monthly pictures with the farming activities in the course of the year, dedication pictures or depictions of writing monks. Historiography and legal texts have not yet played a role in Carolingian book illumination . Folk-language literature was only codified in a few exceptional cases and was nowhere near as valued as would have been a prerequisite for illumination . This applies even to demanding Bible poetry such as Otfried's Gospel Book.

Illumination at the time of Charlemagne

The Merovingian book culture, which was monastic and strongly influenced by insular book illustration, initially continued unaffected by the change of the Franconian ruling dynasty. This changed suddenly at the end of the 8th century when Charlemagne (reigned 768–814) gathered the most important figures of his time at his court in Aachen to reform the entire intellectual life. After his trip to Italy in 780/781, Karl appointed the British Alcuin to be the head of the court school, whom he met in Parma and who had previously directed the school in York . Other scholars at Charles 'court were Petrus Diaconus or Theodulf von Orléans , who also taught Charles' children and young nobles at court. Many of these scholars were sent to important places in the Frankish Empire as abbots or bishops after a few years, because the idea of renewal was connected with the will that the spiritual achievements of the court should radiate to the entire gigantic empire. Theodulf was called Bishop of Orléans , Alcuin in 796 Bishop of Tours. Einhard took over the management of the court school for him.

Around 800, two very different groups of magnificent manuscripts for liturgical use in the large monasteries and at the bishops' seats were created at Karl's court. The two groups of manuscripts are referred to either as the “Ada group” or “Group of the Viennese coronation gospel” or as the “court school” or “palace school of Charlemagne”, respectively, after outstanding works. The illustrated texts of both groups of works are closely related, while the illustrations themselves have no stylistic points of contact. The relationship between the two painting schools has therefore long been controversial. For the group of the Vienna coronation evangelist, a different client than Charlemagne was discussed again and again, but the evidence suggests a localization at the Aachen court.

The Ada group or court school

The first magnificent manuscript that Karl commissioned between 781 and 783, i.e. immediately after his trip to Rome, was the Godescalc Evangelistary named after his scribe . It is possible that this work was not yet created in Aachen, but in the royal palace of Worms . The large initial page, decorative letters and part of the ornamentation come from the island, but nothing is reminiscent of Merovingian book illumination. The novelty of the illumination are the decorative elements taken from antiquity, the plastic-figurative motifs and the font used. The full-page miniatures - Christ enthroned, the four evangelists and the fountain of life - strive for real corporeality and a logical connection to the depicted space and thus set the style for the following works by the court school. The text was written in gold and silver inks on purple-stained parchment.

The manuscripts of the Ada group from the court school, which can be safely located in Aachen, have in common the deliberate examination of the ancient heritage and a consistent pictorial program. They are presumably based primarily on late antique models from Ravenna . In addition to magnificent arcades imitating architectural motifs or precious stone-adorned picture frames and insularly-influenced decorative initial pages, the furnishings include large evangelist pictures, which have varied a basic type many times since the Ada manuscript . For the first time since Roman times, the figures with clearly contoured internal drawings are given back physicality, the space three-dimensionality through swelling, rich robes. A certain horror vacui , the fear of emptiness, is common to the pictures , so sweeping throne landscapes fill the sheets with the evangelist pictures .

The first part of the Ada manuscript and a gospel book from Saint-Martin-des-Champs were created around 790 . It was followed by the named also after his clerk, before 795 written Dagulf Psalter , which was given after the dedication poem by Charles himself in order and as a gift for Pope Hadrian I was determined. At the end of the 8th century, the Gospels of Saint-Riquier and the Harley Gospels in London can be added, around 800 the Gospels from Soissons and the second part of the Ada manuscript and around 810 the Lorsch Gospels . A fragment of a Gospel book in London closes the series of illustrated manuscripts from the court school. After the death of Charlemagne, it apparently dissolved. As decisive as its influence was up to then, it seems to have left little mark on book illumination in the following decades. Aftermath can be proven in Fulda, Mainz, Salzburg and in the vicinity of Saint-Denis as well as some north-east Franconian scriptoria.

The group of the Vienna Coronation Gospel or Palace School

A second group of manuscripts, probably also located in Aachen, but clearly deviating from the illustrations of the court school, is more in the Hellenistic-Byzantine tradition and is grouped around the Vienna coronation gospel , which was produced around 800. According to legend, Otto III found. the splendid manuscript at the opening of Charlemagne's tomb in 1000. Since then, the most artistically important manuscript of this group of works has been part of the imperial insignia , and the German kings swore the coronation oath on the gospel. In contrast to the court school, the manuscripts belong to the group of the Viennese coronation gospel of a palace school of Charlemagne. Four other manuscripts belong to it: The Treasury Gospels , the Xanten Gospels and a Gospel from Aachen, all of which can be dated to the beginning of the 9th century.

The manuscripts of the group of the Vienna Coronation Gospels have no forerunners in their time in Northern Europe. The effortless virtuosity with which the late antique forms were realized must have been learned by the artists in Byzantium, perhaps also in Italy. In comparison with the Ada group at the court school, they lack the horror vacui in particular . The evangelist figures, moved by dynamic curves, are depicted in the postures of ancient philosophers. Their powerfully modeled bodies, airy and light-flooded landscapes as well as mythological personifications and other classical motifs give the works of this group the atmospheric and illusionistic character of the Hellenistic painting style.

During Karl's lifetime, the palace school seems to have been a relatively isolated special case of book illumination, which stood in the shadow of the court school. After Karl's death, however, it was this painting school that exerted a much stronger influence on Carolingian illumination than the Ada group.

Illumination in the time of Louis the Pious

After the death of Charles, court art under Ludwig the Pious (reign 814–840) shifted to Reims, where in the 820s and early 830s under Archbishop Ebo the dynamically moving image conception of the Viennese coronation gospel was received. Before he was called to Reims in 816, Ebo was considered the “librarian of the Aachen court” and brought the legacy of the Carolingian Renaissance with him. The Reims artists, rooted in a different painting tradition, transformed the already lively style of the palace school into an expressive drawing style with nervous, swirling lines and ecstatically excited figures. The sketchy pictures with the dense, jagged lines show the greatest possible distance from the calm picture structure of the Aachen court school. In Reims and in the nearby Hautvillers Abbey , the Ebo Gospels and perhaps the extraordinary Utrecht Psalter, illustrated with non-colored pen and ink drawings, as well as the Bern Physiologus and the Blois Gospel were created as main works around 825 . The 166 depictions of the Utrecht Psalter show, in addition to paraphrasing illustrations of the Psalms, numerous scenes from everyday life.

In addition to the imperial court, the large imperial monasteries and bishops' residences with powerful scriptorias gradually appeared again. From 796 until his death in 804, Alcuin, previously the religious and cultural advisor to Charlemagne, was delegated as abbot to St. Martin in Tours in order to bring the idea of renewal to this important city of the Frankish Empire. The scriptorium flourished under Alcuin, who was critical of images, but the manuscripts lacked illustrations at first and can only be verified on a larger scale under his successors. In the picture dispute, Alkuin was obviously rather critical of figurative representations, so that the Bibles of his time were only adorned with remarkable canon tables, like the Alcuin Bible .

Under Archbishop Drogo (823–855), an illegitimate son of Charlemagne, the Metz school followed up with the court school of Charlemagne. The Drogo sacramentary , created around 842, is the main work of this studio, of whose work an astronomical-computistic textbook has been preserved. The original achievement of the Metz school is the historicized initial , that is, the ornamental letter populated with scenic representations, which was to become the most intrinsic element of all medieval illumination.

The court schools of Charles the Bald and Emperor Lothar

After the division of the Franconian Empire in the Treaty of Verdun in 843, Carolingian book illumination reached its peak in the vicinity of the now West Franconian King Charles the Bald (reign 840–877, Emperor 875–877). Head of the court school of Charles, sometimes referred to as the school of Corbie because of the importance of the Corbie Abbey for the book art of the epoch , was Johannes Scotus Eriugena , who, as an art theorist, pioneered the aesthetic conception of the entire Middle Ages. The monastery in Tours assumed a leading role in illumination under the abbots Adalhard (834–843) and Vivian (844–851). From around 840 onwards, huge illustrated full Bibles were created which were intended, among other things, for the founding of monasteries, including the Moutier-Grandval Bible around 840 and the Vivian Bible around 846 . After the peace agreement between Charles and his brother in 849, the monastery was also in close contact with Emperor Lothar I. With the Lothar Gospels , the Tours School reached its artistic climax. The Tours workshop was under the direct and strong influence of the Reims School. The Tours scriptorium was the only one in the entire Carolingian era that remained productive for several generations, but its heyday came to an abrupt end when it was destroyed by the Normans in 853.

If Tours was to be regarded as the location of the court school of Charles the Bald, then after the destruction of the monastery, St. Denis near Paris probably took over this role, where Charles the Bald became a lay abbot in 867 . Some particularly richly decorated manuscripts date from the period after 850, including a psalter (after 869) and a sacramentary fragment . The most splendid manuscripts are the Codex aureus of St. Emmeram , which was illuminated around 870 on behalf of Charles the Bald, and the Bible of St. Paul, written in gold ink on a purple background around the same time, with 24 full-page miniatures and 36 decorative initial pages.

The court school of Kaiser Lothar was probably located in Aachen. It resumed the style of Charlemagne's palace school and apparently had close contact with the Reims scriptorium, as the Gospels from Kleve show.

Illumination outside the court schools

While the most important book illustrations were created at the Carolingian courts or in abbeys and bishops' residences closely connected to the court, many monastery studios maintained their own traditions. Some of these were characterized by insular book illumination or they continued the Merovingian style. In some cases there were independent services. The book art of the Corbie monastery had already played an important role in book illumination in Merovingian times, and the writing of the monastery is considered the basis of the Carolingian minuscule. A psalter from Corbie (around 800) is noteworthy, the figure initials of which cannot be associated with either courtly Carolingian or insular book illumination and which points to Romanesque book illumination . The richly decorated Psalter of Montpellier , which was probably intended for a member of the Bavarian ducal family, was written in the Mondsee Monastery as early as 788 .

A special case are the Bibles and Gospels, which were written in the first quarter of the 9th century under Bishop Theodulf in Orléans. Theodulf was next to Alcuin the leading theologian at the court of Charlemagne and probably the author of the Libri Carolini . He was even more critical of images than Alcuin, and so the codices from his scriptorium are lavishly designed purple-colored manuscripts written with gold and silver inks, but their painterly ornamentation is limited to canon tables. A gospel book from the Fleury monastery , which belonged to the diocese of Orléans, contains 15 canon tables and only a miniature with the symbols of the evangelists .

The painting school of Fulda was apparently one of the few in the succession of the Aachen court school. This dependence becomes clear in the Fulda Gospel Book in Würzburg from the middle of the 9th century. In addition, it borrowed from Greek models, for example, the nimbled figure of Louis the Pious in a copy of de laudibus sanctae crucis by Rabanus Maurus as a pictorial poem is completely surrounded by the text and thus refers to depictions of Constantine the Great . Rabanus Maurus, a student of Alcuin, was abbot of the Fulda monastery until 842.

The transition to Ottonian art

After the death of Charles the Bald in 877, the fine arts began a sterile period that lasted around a hundred years. Illumination lived on only in the monasteries - mostly on a comparatively modest level - the courts of the Carolingian rulers no longer played a role. With the shift in the balance of power, the East Franconian monasteries became increasingly important. In particular, the initial style of the St. Gallen monastery, but also the illuminations of the Fulda and Corvey monasteries , played an intermediary role for Ottonian book illumination . Other monastic centers of the East Franconian Empire were the scriptoria in Lorsch, Regensburg , Würzburg, Mondsee , Reichenau , Mainz and Salzburg . Especially the monasteries near the Alps were in close artistic exchange with northern Italy .

In what is now northern France, increasingly since the second half of the 9th century, the Franco-Saxon (meaning: Frankish-Anglo-Saxon) school developed, whose book decoration was largely limited to ornamentation and again resorted to insular illumination. The Staint-Amand monastery played a pioneering role , alongside the abbeys of St. Vaast in Arras , Saint-Omer and St. Bertin . An early example of this style is a psalter from Saint-Omer written in the second quarter of the 9th century for Ludwig the German . The most important manuscript of the Franco-Saxon school is the Second Bible of Charles the Bald , which was written between 871 and 873 in the Saint-Amand monastery.

It was not until around 970 that, under the changed auspices of the now Saxon dynasty, a new, completely different style of illumination began. In analogy to the Carolingian art, Ottonian art is also referred to as the “ Ottonian Renaissance ”, but it did not revert directly to ancient models. Rather, influenced by Byzantine art, this referred to Carolingian book illumination. Ottonian book illumination developed its own distinctive, homogeneous formal language, but it began with adaptations of Carolingian works. In the late 10th century, the Maiestas Domini of the Lorsch Gospels was copied exactly, albeit reduced, on the Reichenau in the Petershausen Sacramentary and in the Gero Codex .

literature

- Kunibert Bering: Art of the Early Middle Ages (Art Epochs, Volume 2). Reclam, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-15-018169-0

-

Bernhard Bischoff : Catalog of the mainland manuscripts of the ninth century (with the exception of the wisigothic)

- Part 1: Aachen - Lambach. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1998, ISBN 3-447-03196-4

- Part 2: Laon - Paderborn. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-447-04750-X

- Bernhard Bischoff: Manuscripts and Libraries in the Age of Charlemagne , translated and edited by Michael Gorman (= Cambridge Studies in Palaeography and Codicology 1), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1994, ISBN 0-521-38346-3

- Peter van den Brink, Sarvenaz Ayooghi (ed.): Charlemagne - Charlemagne. Karl's art. Catalog of the special exhibition Karls Kunst from June 20 to September 21, 2014 in the Center Charlemagne , Aachen. Sandstein, Dresden 2014, ISBN 978-3-95498-093-2 (on the book painting passim)

- Hermann Fillitz : Propylaea Art History , Volume 5: The Middle Ages 1 . Propylaen-Verlag, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-549-05105-0

- Ernst Günther Grimme: The History of Occidental Illumination. DuMont, Cologne 3rd edition 1988, ISBN 3-7701-1076-5 (chapter Carolingian Renaissance , pp. 34-57).

- Hans Holländer : The emergence of Europe. In: Bels style history. Study edition, Volume 2, edited by Christoph Wetzel , Belser, Stuttgart 1993, pp. 153–384 (on book painting pp. 241–255).

- Christine Jakobi-Mirwald: The medieval book. Function and equipment . Reclam, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-15-018315-4 (chapter Karolinger and Ottonen , pp. 237-249).

- Wilhelm Koehler : The Carolingian miniatures . Three volumes, Deutscher Verein für Kunstwissenschaft (monuments of German art), formerly Verlag Bruno Cassirer, Berlin 1930–1960, continued by Florentine Mütherich , volumes 4–8, Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, later Reichert Verlag, Wiesbaden 1971–2013

- Johannes Laudage , Lars Hageneier, Yvonne Leiverkus: The time of the Carolingians. Primus-Verlag, Darmstadt 2006, ISBN 3-89678-556-7

- Lexicon of the Middle Ages : Illumination . 1983, Volume 2, Col. 837-893 (contributions by K. Bierbrauer, Ø. Hjort, O. Mazal, D. Thoss, G. Dogaer, J. Backhouse, G. Dalli Regoli, H. Künzl).

- Florentine Mütherich , Joachim E. Gaehde: Carolingian book painting . Prestel, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-7913-0395-3

- Florentine Mütherich: The renewal of book illumination at the court of Charlemagne , in: 799. Art and culture of the Carolingian period. Vol. 3: Contributions to the catalog of the exhibition Paderborn 1999. Handbook on the history of the Carolingian era. Mainz 1999, ISBN 3-8053-2456-1 , pp. 560-609

- Christoph Stiegemann, Matthias Wemhoff : 799. Art and culture of the Carolingian period. Charles the Great and Pope Leo III. in Paderborn. Vol. 1 and 2: Catalog of the exhibition Paderborn 1999. Vol. 3: Contributions to the catalog of the exhibition Paderborn 1999. Handbook on the history of the Carolingian era. Mainz 1999, ISBN 3-8053-2456-1

- Ingo F. Walther, Norbert Wolf: Masterpieces of book illumination. Taschen, Cologne u. a. 2005, ISBN 3-8228-4747-X

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Ehrenfried Kluckert: Romanesque painting , in: Romanik. Architecture, sculpture, painting , ed. v. Rolf Tomann, p. 383. Tandem Verlag, o.O. 2007.

- ↑ a b c d Vienna, Austrian National Library , Cod. 652. Literature: Mütherich / Gaede, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Rome, Vallicelliana .

- ↑ a b Rom, Vaticana , Vat. Lat. 3868. Literature: 799. Art and culture of the Carolingian period , Volume 2, pp. 719–722.

- ↑ Vita Aegil II c. 17, 131-137

- ↑ Christine Ineichen-Eder, artistic and literary activity of Candidus-Brun von Fulda. In: Fuldaer Geschichtsblätter 56, 1980, pp. 201-217, here p. 201; P. 209f .; see. the critical edition by Gereon Becht-Jördens, pp. XXIX-XL; the illustrations ibid. p. 31; P. 39; P. 42. The only manuscript from which the Jesuit Christoph Brouwer edited the text in his Sidera illustrium et sanctorum virorum , published in Mainz in 1616 , and from which he published reproductions of three illustrations in his Antiquitatum Fuldensium libri IV copperplate reproductions published in Antwerp in 1612 , was probably during lost during the Thirty Years' War with the Fulda library.

- ↑ Fillitz, p. 25.

- ↑ Walther / Wolf, p. 98.

- ↑ Jakobi-Mirwald, pp. 149f.

- ↑ Pierre Riché : Die Welt der Karolinger , p. 249. Reclam, Stuttgart 1981. The number is based on the knowledge of the 1960s.

- ↑ a b Pierre Riché: The world of the Carolingians , p. 251ff. Reclam, Stuttgart 1981.

- ↑ Lexicon of Book Art and Bibliophilia , ed. v. Karl Klaus Walther, p. 47. Weltbild, Munich 1995.

- ↑ a b Pierre Riché: Die Karolinger , p. 393. dtv, Munich 1991.

- ↑ Grimme, p. 34.

- ↑ Jakobi-Mirwald, p. 215ff.

- ↑ a b Mütherich 1999, p. 564.

- ↑ a b Mütherich 1999, p. 561.

- ↑ Bering, pp. 219f.

- ↑ Magnus Backes, Regine Dölling: The Birth of Europe , p. 96ff. Naturalis Verlag, Munich undated

- ^ A b Erwin Panofsky : The Renaissance of European Art , p. 58.Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1990.

- ^ Erwin Panofsky: The Renaissance of European Art , p. 60.Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1990.

- ↑ a b Jakobi-Mirwald, p. 239.

- ↑ a b Bering, p. 137.

- ↑ Bering, pp. 110f.

- ^ John Mitchell: Charlemagne, Rome and the legacy of the Lombards , in: 799. Art and culture of the Carolingian period , Volume 2, p. 104.

- ^ Erwin Panofsky: The Renaissance of European Art , p. 62.Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1990.

- ↑ Capitularia regum Francorum 1. Ed. By Georg Heinrich Pertz. Monumenta Germaniae Historica 3, Leges in folio 1. Hanover 1835, unaltered reprint Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-7772-6505-5 , pp. 53–62 No. 22. [Also available as an online edition ]

- ↑ a b c d Holländer, p. 248.

- ↑ a b c d Holländer, p. 249.

- ↑ a b Holländer, p. 253.

- ↑ Laudage, pp. 92f.

- ↑ Bamberg, State Library , Msc.Class.5. Literature: 799. Art and Culture of the Carolingian Period, Volume 2, pp. 725–727.

- ^ Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale , Lat. 7899. Literature: Mütherich / Gaehde, pp. 26-27.

- ↑ Bern, Burgerbibliothek , Cod. 264. Literature: Mütherich / Gaehde, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Rom, Vaticana, Reg. Lat. 438. Literature: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Liturgy and Devotion in the Middle Ages , pp. 82–83. Published by the Archbishop's Diocesan Museum in Cologne. Belser, Stuttgart and Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-7630-5780-3

- ↑ So u. a. Fillitz, p. 22.

- ↑ Jakobi-Mirwald, p. 238.

- ↑ Lexicon of the Middle Ages , Col. 842.

- ^ London, British Library, Cotton Clausius BV

- ^ Brescia, Biblioteca Queriniana , Ms. E. II. 9.

- ↑ Grimme, p. 45.

- ^ Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Lat. 265.

- ↑ Monza, Bibl. Capitolare, Co. GI

- ↑ Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional , Cod. 3307. Literature: Mütherich / Gaehde, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Bering, p. 134.

- ↑ Amiens, Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms. 18. Literature: Fillitz, p. 34; 799. Art and Culture of the Carolingian Period, Volume 2, pp. 811–812.

- ^ Paris Bibliothèque Nationale, Lat. 9380 (so-called Theodulf Bible from Orléans ); Manuscript in Le Puy, Cathedral Treasury; Gospels from Tours, Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms. 22; Evangeliar from Fleury, Bern, Burgerbibliothek, Cod. 348. Literature: Bering, p. 135f.

- ↑ Bern, Burgerbibliothek, Cod. 348. Literature: Mütherich / Gaehde, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Würzburg, University Library, Mp. Theol. fol. 66

- ↑ Grimme, p. 53.

- ↑ Lorsch Gospels .

- ^ Erwin Panofsky: The Renaissance of European Art . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1990, pp. 64-65.