Gothic book illumination

The Illumination Gothic came from France and England, where she used to 1160/70, while in Germany until around 1300 Romanesque remained dominant forms. Throughout the entire Gothic epoch, France, as the leading art nation, was decisive for the stylistic developments in book illumination . With the transition from the late Gothic to the Renaissance , book illumination lost its role as one of the most important art genres in the second half of the 15th century as a result of the spread of book printing .

At the turn of the 12th to the 13th century, commercial book production took on the side of monastic book production, and at the same time more and more artist personalities appeared by name. From the 14th century onwards, the master who ran a workshop with which he was active in both panel and book painting became typical . In the course of the 13th century, the high nobility replaced the clergy as the most important commissioner, making secular courtly literature a preferred subject of illumination. The most illustrated type of book remained the book of hours intended for private use .

Compared to the Romanesque period, Gothic painting is characterized by a soft, sweeping figure style and flowing folds. This tendency remained valid throughout the entire Gothic era and culminated in the so-called soft style . Other characteristic features were the use of contemporary architectural elements for the decorative arrangement of the picture fields. From the second half of the 12th century in Europe mostly red and blue found Fleuronné initials as a decoration typical form of manuscripts of the lower and middle levels of equipment use. Independent scenes, which were executed as historicized initials and drolleries at the lower edge of the picture, offered space for imaginative depictions independent of the illustrated text and made a significant contribution to the individualization of painting and the abandonment of frozen picture formulas. A naturalistic realism with perspective, spatial depth effects , light effects and realistic anatomy of the persons depicted, based on the realism of the art of the southern Netherlands , increasingly prevailed in the course of the 15th century and pointed to the Renaissance.

Basics of Gothic book illumination

Temporal and geographical framework

The Gothic is a style epoch of the West, i.e. Europe without the Byzantine culture, whose art , however, exerted a great influence on that of Western Europe. The starting point of the Gothic was France, which remained the leading European art nation until the late Gothic.

The temporal boundaries to the previous Romanesque and the subsequent Renaissance are fluid and can vary by several decades in different regions. In France, the Gothic began in book illumination around 1200 - almost four decades after the first early Gothic cathedrals were built. England was affected by this change in style around 1220, while in Germany Romanesque forms partly persisted until around 1300. Everywhere the style change in painting was preceded by that in architecture . Around 1450 the woodcut , especially in the form of the block book , competed with the lavish illumination. The rapid spread of letterpress printing and printmaking, initially mostly hand-colored afterwards, in the second half of the 15th century largely displaced book illumination, especially since copperplate engraving, a printing technique that also enabled artistically sophisticated illustrations. By the end of the 15th century, copperplate engraving had surpassed book illumination not only in terms of efficiency, but also in artistic terms: great Renaissance artists such as Master ES , Martin Schongauer , Albrecht Dürer or Hans Burgkmair the Elder devoted theirs to graphic techniques and not to book illumination greatest attention. While printmaking became a mass medium, book illumination now concentrated entirely on representative splendid codices that were still being created into the 16th century. The change in the task of illumination roughly coincided with the transition from Gothic to Renaissance.

Materials and Techniques

The introduction of paper as a writing material revolutionized the book industry fundamentally. The paper had already been invented by an official of the imperial court in China around 100 AD, had established itself in Arabia in the 12th century and reached Europe in the 13th and 14th centuries. In the 15th century it almost completely displaced parchment and made the production of books much cheaper.

Book production increased rapidly throughout the Gothic period. As the book became affordable for the broader class, so did the usual level of equipment. The representative splendor codex with opaque color painting, in exceptional cases still with gilding and on parchment, increasingly became the exception, the text illustration with glazed pen drawings or only with undemanding historicized initials the rule.

Since illustrated books have increasingly been created for private use since the 13th century, small-format manuscripts have replaced the large-format codices for monastic communities or for the liturgy.

Artist and client

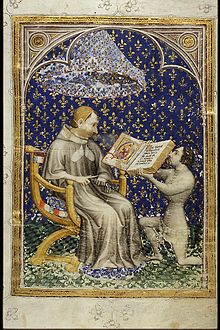

At the turn of the 12th to the 13th century, commercial book production took on the side of monastic book production. The starting point for this serious turning point were the universities , especially those of Paris and Bologna , where, however, mainly theological and legal literature arose that was relatively seldom illuminated. For book illumination, the high nobility was more important, and they came a little later as the commissioner of secular courtly literature . Noble ladies played an important role in promoting literature such as book illumination. In the 14th and especially in the 15th century, this circle expanded to include the lower and official nobility, patricians and finally rich merchants, for whom books of hours and other devotional books were primarily produced for private use. Particularly noble clients were often depicted in dedication pictures on one of the first sheets of a manuscript. With the help of such dedication pictures, the tendency towards ever closer portraits can be followed.

By the middle of the 13th century at the latest, however, the heyday of monastic scriptorias was over in all areas . With the development of commercial studios, more and more artistic personalities appear in the Gothic era. From the 14th century onwards, the master who ran a workshop with which he was active in both panel and book painting became typical . In addition, the monastic scriptoria remained productive.

Especially in the Upper German reform monasteries of the 15th century, nuns like Sibylla von Bondorf can often be identified as illuminators. The typical works of these "nuns paintings" are colorful, characterized by emotional expression and artistically not very demanding. It is not known whether nuns also contributed to outstanding works that were produced for women's conventions, or to what extent women were able to work in professional studios. In any case, masterful illuminations such as the Katharinental Graduale or the Wonnental Graduale were created for women's monasteries . The writer Christine de Pizan reports in 1405 in the city of women about an illuminator Anastasia, who, among other things, illuminated works by Christine and surpassed all the artists of the city of Paris in painting vine leaf ornaments to decorate books and background landscapes and who sells her works at high prices.

In the 15th century, independent workshops prevailed, which manufactured inexpensive manuscripts with simple glazed pen drawings in stock without a specific order and then advertised their publishing program. The most famous workshop of this type is that of Diebold Lauber , which can be traced back to Hagenau between 1427 and 1467 . After the rapid spread of letterpress printing and graphic book illustrations , some illuminators concentrated again on representative magnificent manuscripts. Famous artists on the threshold of the Renaissance, who emerged as panel painters and illuminators and directed high-performance workshops, were Jan van Eyck , Jean Fouquet and Andrea Mantegna . While regional peculiarities of style receded, the individual handwriting of the individual artistic personality gained in importance.

Book types

|

|

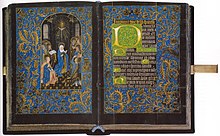

Double page from the book of hours of the Duke von Berry of the Limburg brothers (France, between 1410 and 1416).

The spectrum of illustrated texts expanded significantly in the Gothic period. Secular, courtly literature in the vernacular in particular became the subject of illustration in the late 12th century and took the place of the Latin liturgical texts. The only secular genre that was illuminated at the very highest level with a gold background and opaque paint was the chronicle . World chronicles combined historiography with lay religious literature. It is noticeable that the German heroic epic was illustrated late and then rarely and with little claim, while the chanson de geste about the deeds of Charlemagne in France , which seems to be more closely associated with historiography, was particularly lavishly furnished. Magnificent manuscripts, but without a gold background, were also created for collections of courtly epics or poetry. A famous example of such a composite manuscript is the Codex Manesse , which was created around 1300 in Zurich .

In the 13th century, illuminated factual and specialist texts appeared particularly in the university environment. In Bologna dominated legal books. The imperial or papal bulls , the most famous illustrated example of which is the golden bull of Charles IV in a commissioned work for King Wenceslaus from 1400 , also belonged to the legal system . The Sachsenspiegel by Eike von Repgow was a source of law illustrated several times for practical and not academic use .

However, the typical illustrated Gothic manuscript remained the religious book, which, in contrast to earlier times, was now primarily intended for private devotion by lay people . In the 13th century, the Psalter was primarily intended for this purpose , from which the Book of Hours later emerged, which became the most illustrated type of book. The history Bibles and the Biblia pauperum also belong to the area of lay piety . Theological treatises of the church fathers , the great scholastics and mystics , legends of saints and authors from Latin and Greek antiquity were illustrated in large numbers in the university and monastic environment .

Influences of other arts

While wall painting was groundbreaking for Romanesque book art , Gothic took up above all the suggestions of glass painting , which had a decisive influence on Gothic cathedrals. Immediately, the illumination took over the often dominating bright red and blue in the miniatures, at least as far as representative body color paintings were concerned. The adaptation of the glass painting particularly affected the pattern base of the miniatures, gilding contributed to the luminosity of the manuscripts.

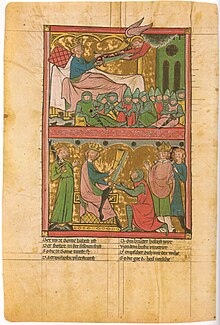

The dependence on stained glass is particularly clear in the early Gothic French Bible moralisée , which has come down to us in 14 manuscripts. Biblical scenes and their typological equivalents stand opposite each other in round fields. In addition to the arrangement, the coloring and style of Gothic medallion windows of French cathedrals are also reflected in the miniatures.

A little later, book illumination also transferred the tracery of Gothic cathedral architecture into its medium. Building sculptural forms became common as picture ornaments, which are reminiscent of the eyelashes , pinnacles , rose windows , gables , friezes and three passes, for example of the Paris Sainte-Chapelle or the great Gothic cathedrals. The bright colors in red, blue and gold could give an indication of the colored decoration of Gothic cathedrals, which can only be found in written sources, but is no longer preserved in the churches.

Style history

See also the overview of major works of Gothic book illumination

General stylistic features and developments

Stylistic characteristics that remained valid throughout the Gothic period were a soft, sweeping figure style with a supple, curvy, linear ductus, courtly elegance, elongated figures and flowing folds. Another characteristic was the use of contemporary architectural elements for the decorative structuring of the picture fields.

From the second half of the 12th century, red and blue fleuronné initials were mostly used throughout Europe as the typical decorative form of manuscripts of the lower and middle equipment level. In most Gothic manuscripts, the fleuronné is the only form of decoration and was then carried out by the rubricator , who was mostly identical to the scribe , especially for undemanding manuscripts . The fleuronné is particularly suitable as a reference point for the dating and localization of manuscripts.

Independent scenes, which were inserted as historicized initials and drolleries at the lower edge of the picture, offered space for imaginative depictions independent of the illustrated text and made a significant contribution to the individualization of painting and the abandonment of frozen picture formulas.

As a result of the supraregional marriage policy of the European royal houses as well as the increasing mobility of artists, a formal language developed across Europe between around 1380 and 1420, which is known as International Gothic because of its supraregional commitment . Characteristics of this style were softly flowing folds and hairstyles as well as slender figures with courtly, tight-fitting and high-belted robes. Because of the soft line of the drawing, the term "soft style" used to be used.

A typical feature of Gothic painting was to portray the figures depicted in contemporary fashion and in Gothic architecture, even if they were biblical events. As early as the 13th century, there were increasing numbers of examples of sketchbooks that no longer only adopted iconographic models from other works of art, but also represented new creations through their own studies of nature and architecture. A famous sketchbook is that of the French Villard de Honnecourt , which was written around 1235. On the threshold of the Renaissance , based on the realism of the art of the southern Netherlands , naturalistic representations dominated. Perspective, spatial depth effects, light effects and realistic anatomy of the depicted people became established in the course of the 15th century and point to the Renaissance.

After the spread of book printing , book illumination in the second half of the 15th century concentrated again on particularly splendid representational codes for high-ranking clients. In general, the distinction between book and panel painting became increasingly difficult in the course of the late Gothic period: the miniatures more and more took over the complex picture compositions of monumental painting and developed from instructive text illustration to largely autonomous image.

France

By 1200 the courtly culture and the fine arts of France had achieved a generally recognized priority position in the West and radiated across Europe. This hegemonic position was favored by a combination of various factors, including the advanced centralization of France with a strong courtly kingship, the development of a national idea and the charisma of the Paris University . In France, especially in Paris, the significant relocation of manuscript production to professional workshops of secular artists began. From the end of the 13th century these were concentrated in Paris' Rue Erembourg , today's Rue Boutebrie , not far from the copyists and the paper merchants.

The order in 1195 in Tournai resulting Psalter or Bible moralisée are highlights of the early Gothic illumination. In these manuscripts, the Romanesque design language passes into a classical phase, the characteristics of which are softly flowing, wrinkled robes and finely modeled faces and a new physicality of the figures shown.

The new style was constituted until it had developed all essential characteristics around 1250 and the high Gothic era began. Representative examples from the third quarter of the 13th century include the Psalter of Louis the Saint , the Gospel Book of the Sainte-Chapelle and the Roman de la Poire .

With Maître Honoré , a new, prominent type of artist appeared at the end of the 13th century: the court painter who worked exclusively for the king or a prince. Maître Honoré is verifiable as the first of these court painters and at the same time France's first illuminator known by name. He and his contemporaries tried to give their pictures three-dimensionality and created works that are reminiscent of sculptures and reliefs in the plastic modeling of the robes, faces and hair. An exemplary work from the workshop of Maître Honoré is the Brevarium of Philip the Beautiful , created around 1290 .

The first truly three-dimensional interior representation north of the Alps can be found around 1324–1328 in the small-format book of hours of Jeanne d'Evreux by court painter Jean Pucelle , who first introduced France to Italian Trecento art. At the same time he introduced the grisaille technique into book illumination, which was to remain very popular throughout the 14th century and was adopted by his students such as Jean le Noir . In addition, he strongly shaped the typical high Gothic framing with leaf tendrils interspersed with drolleries, which clasp the image and text mirror. Pucelle is also the first illuminator, about whom several documents and entries in colophons give information in the years 1325–1334 . It is known that he employed at least three people in his workshop.

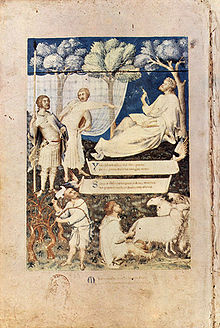

Illumination of this period was largely determined by the patronage of King Charles V , who ruled from 1364 to 1380 and is considered one of the greatest bibliophiles of the Middle Ages. By drawing foreign artists to Paris, including Jean de Bondol from Bruges and Zebo da Firenze , Karl played a major role in making Paris an international center of book illumination, which received new impulses and spread across Europe. His brothers Jean de Berry and Philipp the Bold became equally important art patrons . In the service of the Duke of Berry were André Beauneveu and Jacquemart de Hesdin , who came from the Flemish Artois , as well as the Brothers of Limburg , who between 1410 and 1416 created the most famous illustrated manuscript of the 15th century with the Duke of Berry's Book of Hours the first realistic landscape paintings of art can be found north of the Alps.

The first central perspective interiors can be found with the Boucicaut master , who can be traced back to Paris between 1405 and 1420. He and the Limburg brothers introduced the acanthus tendril as a dominant decorative motif in French illumination. The Bedford master , who worked in Paris from 1405–1465 , combined the main miniatures with the surrounding peripheral scenes as a thematic unit. Jean de Bondol did not shy away from depicting the king himself in an unidealized image and introducing the art of portraits , which approximated reality, to illumination. Together, the Limburg brothers, the Boucicaut Master, the Bedford Master and Jean Bondol mark a new, realistic style section in Gothic book illumination, which productively transformed Italian Trecento art and the International Gothic. At the same time, the Rohan master should be mentioned, who, however, took a special route and partially ignored otherwise binding conventions of French illumination.

In addition to the dominant center of Paris, only the papal residence in Avignon was able to assert itself as an independent art center in the 14th century . In the second quarter of the 15th century, however, as a result of France's defeat by England in the Hundred Years War and the resulting weakness of the kingship - the royal court also evaded the Touraine - Paris lost its dominant position as an art center in favor of the Loire region and western France, where royal courts competed with the splendor of the king and attracted important artists as court painters. Even in Paris, for example, the Bedford master was not in the service of the king, but of the English governor, the Duke of Bedford .

Immediately after the middle of the century, a new style established itself, heavily influenced by the realism of the art of the southern Netherlands . The Jouvenel master , who can be traced back to between 1447 and 1460, leads to Jean Fouquet from Tours , who in the third quarter of the 15th century became the outstanding artistic personality of France. His main works include the Etienne Chevalier's Book of Hours and the Grandes Chroniques de France . With Fouquet, French painting stood on the threshold from Gothic to Renaissance. His work is considered an independent synthesis of the French painting tradition, the early Italian Renaissance of the Quattrocento and Dutch realism. In particular, the perspective constructions, the use of light and the historical accuracy of his pictures show Fouquet to be one of the most important painters of his time.

The only illuminator of Fouquet's rank was Barthélemy d'Eyck , from the Netherlands, who illustrated the book of the loving heart for René d'Anjou between 1457 and 1470 . After Fouquet, only a few illuminators appear, including Jean Colombe in Bourges , Jean Bourdichon in Tours and Maître François in Paris.

England

Around 1220 in England the gradual transition from Romanesque to Gothic book illumination took place. The studios in the vicinity of the English court show the strongest connection to French illumination, which, however, compared to the French kings, played a minor role as a client of illuminated manuscripts. The grotesque animals and bizarre figures of the drolleries, which are largely detached from the text, are characteristic of English book illumination, especially between around 1280 and 1340. In addition to illustrations in opaque color painting with a gold background, English book illumination continued the technique of colored drawing, which was particularly widespread in the British Isles.

The Benedictine monk Matthew Paris from the monastery of St Albans stands out as an author, scribe and illuminator and belonged to King Henry III's closest circle of advisers . on. His main works are the Chronica majora , which he illustrated with partially glazed pen drawings, some of which were based on his own eyewitnesses. The Salisbury scriptorium was based on the style of St Albans. In the vicinity of the university , workshops based on the Parisian model were established in the second third of the 13th century. Here seemed William de Brailes , the more of its miniatures signed in the mid-13th century as one of the few whose names are known illuminator this time. There were also important workshops in London, where there were particularly wealthy buyers.

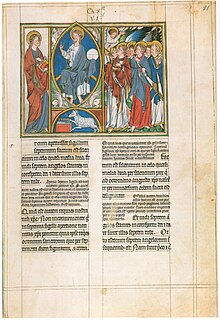

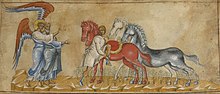

The most frequently illustrated type of book in English Gothic was the psalter, even after the book of hours had long since established itself on the continent in the 14th century. The most important psalters of English Gothic of the 13th century include the Westminster Psalter , some psalteries from Peterborough , a copy illustrated around the middle of the 13th century for a nun in Amesbury , a psalter for an abbot of Evesham who was unusually richly furnished so-called Oscott Psalter , which may have been illuminated around 1270 for the later Pope Hadrian V , and the Alphonso Psalter . The Ormesby Psalter , the Luttrell Psalter , the Gorleston Psalter , the De Lisle Psalter , the Peterborough Psalter and above all the particularly splendid Queen Mary Psalter stand out from the 14th century . In addition, Bibles and individual Bible books were among the preferred book types in English book illumination, including the illuminated apocalypse manuscripts of the 13th century, such as the Trinity College Apocalypse (around 1242-1250), the Lambeth Apocalypse (1260-1270), the Douce Apocalypse (1270-1272). Other subjects of illumination were the legends of saints and bestiaries .

In the 14th century London became the main center of English book illumination, where the royal court now played a leading role in promoting book illumination. Westminster in particular attracted artists from a wide variety of backgrounds and shaped its own style, first the Court Style , then the Queen Mary Style . At the end of the 14th century Richard II in particular promoted book illumination. In East Anglia , important illuminated manuscripts with lively, naturalistic details were created for the Bohun family .

Around 1400 a form of International Gothic dominated England too. The numerous large-format manuscripts that were increasingly produced around this time are striking. In the 15th century, English book illumination was particularly influenced by Flemish and Lower Rhine illustrated manuscripts, which were introduced in large numbers. The illuminator Herman Scheerre, who was probably from the Lower Rhine region, played an important role in the first half of the 15th century .

The abolition of the monasteries in 1536–40 and the image hostility of the reformers in the 16th and 17th centuries resulted in heavy losses.

Netherlands

Throughout the Middle Ages, the southern Netherlands with Flanders and Brabant dominated the Dutch area economically and culturally. Parts of the southern Netherlands belonged to the French crown and had been closely linked to France as the Burgundian Netherlands since the 14th century . The French Gothic penetrated the southern Netherlands particularly strongly in the 13th century. The transition from Romanesque to Gothic took place here around 1250. The Maasland , especially the diocese of Liège, has played an important role as a mediator between French and German book art since Carolingian times . In the 14th century, Maastricht lapped the episcopal city of Liège with numerous illustrations of the Bible, the lives of saints, but also profane works. A third center was Sint-Truiden .

While Flemish book illumination in the 13th century was still completely under the influence and in the shadow of that of Paris, the great French clients of the 14th century often moved Flemish masters such as Jean de Bondol , André Beauneveu or Jacquemart de Hesdin to Paris. Presumably under Italian influence, three-dimensional space became an important topic in Dutch book illumination. The will to be more faithful to nature also had an impact on the portrayals of people. Around 1375–1420, the International Style also dominated the Netherlands.

The 15th century was the great heyday of Flemish book illumination. Now leading artists working in France came from the Netherlands , such as the Brothers of Limburg or later Barthélemy d'Eyck , but under the reigns of Philip the Good and Charles the Bold the Flemish cities also flourished to their greatest economic and cultural prosperity. Philipp in particular gathered outstanding artists such as Loyset Liédet , Willem Vrelant and Jan de Tavernier at his court in Bruges . A series of illuminated manuscripts from Valenciennes from the years 1458–1489 is attributed to Simon Marmion and shows the influences of the landscapes by Dierick Bout . The anonymous master of Mary of Burgundy heightened the illusionism of Dutch illumination by adding trompe l'oeil effects.

At that time, the influence of French art waned, and the old Dutch painting developed a distinct character of its own, the revolutionary innovation of which was painting based on observation of nature. What was unmistakably new in old Dutch painting was first shown in the fact that the medieval gold grounds were replaced by realistic landscapes as the background. The precise observation of nature also extended to the representation of the human body, whose movement and surface character were precisely reproduced, as well as to the plasticity of inanimate objects through carefully observed and effectively used light effects. The central person in the fundamental renewal of art of this time was Jan van Eyck , who possibly worked as an illuminator himself and illuminated the Turin-Milan Book of Hours .

After the death of Charles the Bold in 1477 and the fall of the House of Burgundy, the domestic market for Dutch artists suddenly dwindled. As a result, masters like Simon Bening and the master of the Dresden prayer book exported high -quality books of hours as luxury goods to all European countries. Not only did the Flemish workshops have a high standard of performance, they were also well-organized production centers capable of producing devotional books in large numbers and for a wide range of customers. The colorful and naturalistic book illumination of this Ghent-Bruges school stands on the threshold of painting of the Renaissance.

The northern Netherlands produced only a few significant Gothic manuscripts. The main center was Utrecht . From the nearby Marienweerd Premonstratensian Abbey come a Reimbibel by Jacob van Maerlant and by the hand of the same painter an illuminated manuscript Der naturen bloeme from the 14th century. In Utrecht around 1440, an anonymous master created the most splendid and imaginative example of northern book illumination with over 150 miniatures: The Book of Hours of Katharina von Kleve , which was clearly influenced by Flemish panel painting, especially by Robert Campin . The master of the Bartholomäus altar was also active as a book and panel painter in Utrecht and Cologne around 1470–1510 . The art of engraving displaced book illumination in Holland more than in the south towards the end of the 15th century. The losses caused by the Reformation iconoclasm in the 16th century make it difficult to gain an overview of northern Dutch Gothic art .

German language area

Influenced by the Gothic architecture and characterized by the jagged, sharp brittle design of garments Zackenstil forwards in German-speaking countries over the Gothic painting. It was not until 1300 that the Gothic style caught on in all German regions. Compared to France, the monastic scriptoria dominated book illumination for a longer period and commercial workshops came to the fore relatively late.

The Upper Rhine and Lake Constance areas as well as the Lower Rhine cultural area were the first to adopt the new style elements coming from France. Especially Alsace , where Strasbourg was the undisputed center of German Gothic in the 13th century, played a central role in Franco-German cultural exchange. Lorraine , where Metz was an important producer of books of hours, and the Maasland around Liège also played an important mediating role . South of Lake Constance, in Zurich , the Manessische Liederhandschrift was created between 1300 and 1340 with 137 poet pictures, which is also of paramount importance as a text witness to the Middle High German minnesang . In the region between Konstanz and Zurich, other outstanding codices were created in the first half of the 14th century, including two manuscripts each with the world chronicle of Rudolf von Ems in connection with Karl des Stricker or the Katharinentaler Graduale .

Important early Gothic works were two Franco-Flemish influenced graduals illuminated by Johann von Valkenburg in Cologne in 1299 . After 1400, Cologne, one of the largest cities in Europe and a university city since 1388 , again became a center of book art. Stefan Lochner was not only active as a panel painter, but also as an illuminator.

In the course of the 14th century, the Gothic style gradually reached eastern regions: First, Austrian monastery scripts appeared in St. Florian , Kremsmünster , Admont , Seitenstetten , Lilienfeld , Zwettl and Klosterneuburg , which were influenced by Italy and gradually turned into a realistic style around 1330 arrived. In Vienna, Albrecht III. around 1380 a courtly illuminator's workshop, which was active until the middle of the 15th century. After a break of a few years, book illumination revived under Emperor Maximilian I , reached new heights and carried out the style change to the Renaissance. At the same time, under Maximilian, book printing and printmaking gained in importance, for example through the printed edition of Theuerdank .

In the second half of the 14th century, Bohemia also experienced its splendid climax through courtly book illumination at the court of the Luxembourgers under Emperor Charles IV and King Wenceslaus . Prague had developed into the political and cultural center of the imperial empire and had the first German university since 1348 . The Wenceslas Workshop in particular produced highlights of Gothic book illumination between 1387 and 1405, including the six-volume Wenceslas Bible , the Golden Bull and a Willehalm manuscript.

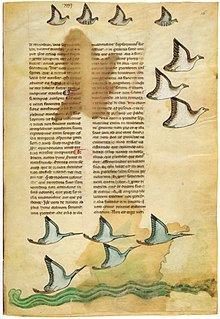

Italy

For longer than in other European countries, Italian book illumination was shaped by Byzantine influence, which remained dominant in both the east-facing Venice and southern Italy . Among the notable works in the Byzantine tradition is the epistolar of Giovanni da Gaibana from Padua, dated 1259 . In the early 13th century, German influences, especially through the Hohenstaufen , had reached southern Italy. Famous factual texts illustrated for the Staufer are the treatise De arte venandi cum avibus (On the art of hunting with birds), which was illustrated with natural studies of birds of prey, and De balneis puteolanis from the second half of the 13th century. Especially the Falk book shows that over Sicily and the Islamic Arts acted on the southern Italian book illumination. In the course of the Trecento and Quattrocento , more and more cities developed into art centers that promoted art as a means of representation and competed to attract the best artists. While at the beginning of the 14th century the French influence still determined Italian illumination, in the 14th century independent styles and individual artistic personalities increasingly emerged in the various regions. The relationship between monumental and book painting increased continuously during this time and miniature art increasingly adopted the composition schemes of large-format painting. Italian literature, which was in its prime, made it necessary to find new illustration schemes. In the course of the 14th century, more and more vernacular works such as Dante's Divine Comedy or the Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio became the focus of interest and were often illustrated.

In Rome and the monasteries of Lazio , the ancient legacy was overwhelming and for a long time prevented the productive reception of the Gothic language of form. With the relocation of the papal seat to Avignon , France , this most important client fell out between 1309 and 1377.

The centers of Italian illumination, however, became the northern Italian cities of Milan and Pavia , ruled by the Visconti , where French influence was predominant. At the court of the Visconti, who were dynastically connected to Burgundy, primarily courtly chivalric novels such as Tristan or Lancelot were written . One of the outstanding illuminators towards the end of the 14th century was Giovannino de 'Grassi , who illustrated , among other things, an office and a breviarum Ambrosianum for Gian Galeazzo Visconti . Other painters in the service of the Visconti were Belbello da Pavia and Michelino da Besozzo .

In Bologna , an independent book illumination developed in the vicinity of the local university , the first well-known representatives of which were Oderisio da Gubbio and Niccolò di Giacomo , celebrated by Dante . The university also produced new types of books, especially legal books were illuminated for the famous law faculty, but also texts by classical authors.

In central Italy , a more lifelike, more folk style of illustration prevailed in the middle-class environment, as embodied by Domenico Lenzi from Florence around the middle of the 14th century. The earliest reception of Giotto's spatial conception of images can be found in the miniatures of Pacino di Bonaguida . One of the most original artists is Bernardo Daddi , whose main work is the Biadaiolo . The Florentine illuminators often dispensed with any decorative ornament and concentrated entirely on pure text illustration. Originally from Siena , Simone Martini mainly created monumental paintings, but was also active as a miniaturist, for example on behalf of Petrarch , for whom he painted the frontispiece of the Codex Ambrosianus around 1340 .

Spain and Portugal

Up to the high Middle Ages, Spain and Portugal were influenced by the Moorish , Christian art remained largely isolated from developments in the rest of Europe. In the middle of the 13th century, however, the Reconquista brought the Iberian Peninsula back into Christian power, with the exception of Granada . As a result, the art of the four kingdoms of Catalonia-Aragon , Castile-León , Portugal and Navarre slowly opened up to European influences. Since the 13th century, artists from France, the Netherlands and Italy have come to the Castilian court in Madrid and the Catalan trading metropolis of Barcelona . The Kingdom of Mallorca was particularly open to French and Italian influences until the mid-14th century .

Among the outstanding works of book illumination of the 13th century include for Alfonso X recorded and illuminated Cantigas de Santa Maria and the Libro de los juegos .

Illumination played a subordinate role within Scandinavian art and was of a modest level. The relatively small number of wealthy monasteries, important schools and people who are able to read and write contributed significantly to this marginal role of book art. Stylistically she was influenced by Anglo-Saxon and German art, but retained the formal language of earlier eras for longer. Illumination of the 13th century is largely limited to archaic historicizing initials in the Romanesque style. It was not until around 1300 that Gothic forms prevailed under English influence. At the same time, many northern European book illuminations throughout the Middle Ages show a provincial folklore. Law books occupy a prominent position among the illustrated Scandinavian codices.

Jewish illumination from the Gothic period

A special case of Gothic painting is the Jewish book illumination of Hebrew manuscripts, which on the one hand was part of the regional art landscape and blended into the contemporary style of the respective country, on the other hand it had similarities throughout Europe and thus stood out from the local schools.

In Europe, Jewish book illumination has only appeared with figurative representations since the 13th century, whereas originally it was entirely limited to ornament. The liturgical Jewish Bibles used in the synagogue were basically in the form of scrolls and were always unadorned. The illustrated religious books were intended for private use, primarily the Hebrew Bible with the Torah , the Pentateuch , the Prophets and the Ketuvim . Other Jewish texts that were frequently illustrated were the Haggada , the Ketubba marriage contract, and the writings of Maimonides and Rashi .

The book art of the Sephardi in Spain and the Jews in Provence was strongly influenced by oriental decoration systems and reached its peak in the 14th century. Characteristic were full-page illustrations and the display of the cult devices of the monastery tent in gold color. Typical of the few surviving Jewish Bibles from the Iberian Peninsula is the combination of European Gothic with Muslim ornamentation. This applies, for example, to the particularly magnificent Catalan Farchi Bible (1366–1382) by Elisha ben Abraham Crescas. With the expulsion of Jews from France in 1394 and 1492 from Spain , where many Jewish communities had already been smashed in 1391, and then from Portugal, this cultural flowering in these countries ended abruptly.

literature

- K. Beer brewer, Ø. Hjort, O. Mazal, D. Thoss, G. Dogaer, J. Backhouse, G. Dalli Regoli, H. Künzl: Illumination . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 2, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1983, ISBN 3-7608-8902-6 , Sp. 837-893.

- Ernst Günther Grimme: The History of Occidental Illumination . 3. Edition. Cologne, DuMont 1988. ISBN 3-7701-1076-5 .

- Christine Jakobi-Mirwald: The medieval book. Function and equipment . Stuttgart, Reclam 2004. ISBN 978-3-15-018315-1 , ( Reclam's Universal Library 18315), (especially chapter: Gothic book painting pp. 263-272).

- Ehrenfried Kluckert: Gothic painting. Panel, wall and book painting. In: Rolf Toman (Ed.) - Gotik. Architecture, sculpture, painting . Special edition. Ullmann & Könemann 2007, ISBN 978-3-8331-3511-8 , pp. 386–467, (Illumination pp. 460–467).

- Otto Mazal : Book Art of the Gothic . Academic printing and Verlagsanstalt, Graz 1975, ISBN 3-201-00949-0 , ( Book art through the ages . 1).

- Bernd Nicolai: Gothic . Reclam, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-15-018171-3 , ( Art Epochs . 4) ( Reclams Universal Library . 18171).

- Otto Pächt : Illumination of the Middle Ages. An introduction. Edited by Dagmar Thoss. 5th edition. Prestel, Munich 2004. ISBN 978-3-7913-2455-5 .

- Ingo F. Walther / Norbert Wolf: Codices illustres. The most beautiful illuminated manuscripts in the world. Masterpieces of book illumination. 400 to 1600 . Taschen, Cologne et al. 2005, ISBN 3-8228-4747-X .

- Margit Krenn, Christoph Winterer: With brush and quill pen, history of medieval book painting, WBG, Darmstadt, 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-648-7

Web links

- Digital version of the Wonnentaler Graduale: Badische Landesbibliothek Karlsruhe, UH 1

- Late medieval illuminated manuscripts from the Bibliotheca Palatina , Heidelberg University Library

Individual references and signatures of the manuscripts mentioned

- ↑ a b Den Haag, Museum Meermanno-Vesteenianum, Ms 10 B 23. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 222–223.

- ↑ a b c Walther / Wolf, p. 35.

- ↑ a b Chantilly, Musée Condé , Ms. 9. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 142–145.

- ↑ Nicolai, p. 50.

- ↑ Jakobi-Mirwald, p. 263.

- ↑ The invention of paper is attributed to Cai Lun

- ^ Brussels, Royal Library, Ms. 9242. Literature: Walther, p. 467.

- ↑ Jakobi-Mirwald, p. 156f.

- ^ Karl-Georg Pfändtner: Illumination (late Middle Ages) . In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria (accessed April 8, 2018)

- ↑ a b Zurich, Swiss National Museum, LM 26117. Literature: Walther, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Karlsruhe, Badische Landesbibliothek, Cod. UH 1.

- ↑ Christine de Pizan: The book of the city of women. Edited by Margarete Zimmermann. dtv klassik, Munich 1990, p. 116.

- ↑ a b c Chantilly, Musée Condé, Ms. 65. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 280–285.

- ↑ a b c Heidelberg, University Library , Cod. Pal. germ. 848. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 196-199.

- ↑ a b Vienna, Austrian National Library , Cod. 338.

- ^ Paris, Bibliothèque nationale , Ms. fr. 19093.

- ^ Vienna, Austrian National Library, Codex Vindobonensis 2554. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 157–159.

- ↑ LexMa, Col. 855.

- ↑ Kluckert, p. 460.

- ^ Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, lat. 10525. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, lat. 8892.

- ^ Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, fr. 2186.

- ^ Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, lat. 1023. Literature: Walther / Wolf, p. 466.

- ^ New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art , The Cloisters. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 208-211.

- ↑ Including the Belleville Hours, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, lat. 10483-10484. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 206-207.

- ↑ Chantilly, Musée Condé. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 320–323.

- ↑ Chantilly, Musée Condé, London, British Library , Add. 37421; New York, Metropolitan Museum; Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, lat. 1416; Paris, Louvre, Departement des Arts graphiques, RF 1679, MI 1093; Paris, Musée Marmottan ; Upton House, Lord Bearsted (National Trust). Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 320–323.

- ^ Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, fr. 6465. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 342-345.

- ^ Vienna, Austrian National Library, Codex Vindobonensis 2597. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 354–355.

- ^ A b Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Douce 180. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 186–187.

- ↑ a b London, British Library, Ms. Royal 2. B. VII.

- ↑ London, British Library, Ms. Royal Ms. 2 A.

- ^ Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum ; London, Society of Antiquaries (Lindsey Psalter).

- ↑ Oxford, All Souls College , Ms. 6.

- ^ London, British Library, Ms. Add. 44874.

- ^ London, British Library, Ms. Add. 50000. Literature: Walther / Wolf, p. 465.

- ^ London, British Library, Ms. Add. 24686.

- ^ Oxford, Bodleian Library , Ms. Douce 366.

- ^ London, British Library, Ms. Add. 42130. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 286-287.

- ^ London, British Library, Ms. Add. 49622.

- ↑ London, British Library, Arundel Ms. 83. pt II. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Brussels, Royal Library, Ms. 9961–62.

- ^ Cambridge, Trinity College Library, Ms. R. 16.2. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 166–167.

- ↑ London, Lambeth Palace , Ms. 209. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 182-183.

- ↑ Berlin, State Library , mgq 42.

- ↑ Turin, Museo Civico, Ms. 47. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 239–241.

- ^ New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, M. 493. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 372–373.

- ↑ Groningen, University Library , Ms. 405.

- ^ Leiden, University Library , BPL 14 A.

- ↑ New York, Pierpont Morgan Library , M 917 and 945. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 310-311.

- ↑ Berlin, State Library, Mgf. 623.

- ↑ a b Vienna, Austrian National Library, Cod. 2759–64. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 242–247.

- ↑ St. Gallen, Vadiana , Cod. 302; Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 192–193. Berlin, State Library, Mgf. 623. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 194-195.

- ↑ Bonn, University Library , Cod. 384; Cologne, Diocesan Museum .

- ^ Vienna, Austrian National Library, Cod. Ser. n.2643.

- ↑ a b Rome, Vaticana , Cod. Pal. lat 1071. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 172-173.

- ^ Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana .

- ↑ Padua, Seminario.

- ^ Rome, Biblioteca Angelica .

- ^ Paris, Bibliothèque nationale.

- ↑ Milan, Biblioteca Trivulziana, Cod. 2262.

- ^ El Escorial, Biblioteca de San Lorenzo , Ms.TI1. Literature: Walther / Wolf, pp. 188-189.

- ↑ Miriam Magall: A short history of Jewish art. Cologne, DuMont 1984. p. 219.

- ^ Letchworth, Collection of Rabbi DS Sassoon, Ms. 368.