Gunnar Heinsohn

Gunnar Heinsohn (born November 21, 1943 in Gotenhafen ) is a German economist and sociologist , emeritus professor of social education at the University of Bremen and a freelance journalist . He became known to a broader public through controversial theses on population policy , demography and historical chronology .

Life

Heinsohn is the third son of Roswitha Heinsohn (1917–1992) and the submarine commander Heinrich 'Henry' Heinsohn (1910–1943), who was stationed in Gdingen , which was then occupied and known as the "Gotenhafen" . Before Gunnar was even born, he died when his submarine U 438 was sunk . In June 1944, the family came to Blankenhagen in Pomerania on the Dietrich von Doetinchems (1904–1980) estate. After fleeing in January 1945, Heinsohn and his family lived in Brodau (now part of Schashagen ) on the Baltic Sea. The family only moved to Pützchen near Bonn in 1950 .

Heinsohn studied from 1964 at the Free University of Berlin - after a few semesters Jura - journalism , sociology , psychology , history and economics and religious studies . In 1971 he obtained his diploma in sociology and in 1974 became a social science Dr. phil. PhD. From 1973 to 2009 he taught at the University of Bremen . There he took leave of absence from October 1976 to March 1978 for a research stay in the Israeli kibbutzim ( Adamit , Hasorea and Yahel ).

In 1982 Heinsohn received his doctorate in economics. From 1982 to 1993 he spent several months each year in Toronto , writing in the Robarts Research Library . In 1984, Heinsohn was appointed professor of social education at the University of Bremen. From 1993 he was the spokesman for the Institute for Comparative Genocide Research he founded ( Raphael Lemkin Institute for Xenophobia and Genocide Research ).

Heinsohn teaches property economics in the master's courses at the Management Center St. Gallen and at the Institute for Financial Services Zug, one of the five institutes of the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences , as well as war demography at the Berlin Federal Academy for Security Policy and at the NATO Defense College in Rome . He regularly publishes articles on the Axis des Guten website and in the author's magazine Swiss Month .

Fields of activity and response

A number of the approximately 900 Heinsohn publications met with a strong response in the mass media . So Why Was Auschwitz? voted third among the non-fiction books of the month by Süddeutsche Zeitung and NDR in February 1995 ; The Creation of the Gods came first on the list of the present in 1997. By contrast, Heinsohn's publications were viewed critically or even negatively by the specialist sciences. This was true occasionally for his economic work, but especially for his investigation of the relationship between witch hunt and demography or his questioning of various chronologies . His thesis on the "annihilation of wise women" by the witch hunt reached 14 editions - Franz Irsigler called it a "bestseller" - and in 2003 Walter Rummel stated that "the public image it conveyed is still predominant".

Economy

In the lexicon of economic works , which summarizes writings from the history of economics since antiquity, Heinsohn is one of two living authors in the German language with three works. In Private Property, Patriarchat, Geldwirtschaft (1984), Heinsohn replaced the thesis that money had replaced barter with the property paradigm of economic activity. Money is therefore not seen as a medium of exchange , but as a claim against the non-physical property side of the property of the issuing bank . Money is therefore a claim to property, whose emitter does not lend any goods when it is charged to make the money valuable. These therefore belong to the ownership side of his assets, which he continues to use for himself. Property, interest and money (together with Otto Steiger , 1996) say about the origin of money : “Money is invented as soon as an owner credits another owner with claims against his property, for which he promises interest and repayment and pledges part of his property . "

With the explanation of money from something intangible (property) instead of from physical goods (possession), in Heinsohn's view, interest as a main riddle of economics can also be solved; because "the question of why there is interest has not yet been solved by economics" ( Binswanger ). Since the money-creating creditor does not lend goods from the property side of his property, but creates money as a claim against his property side, he cannot suffer any loss of goods when lending. The debtor does not receive any goods (items) that he can use to produce additional goods, part of which he has to pay to the creditor as "interest on goods". The interest-bearing loss consists rather in the loss of freedom over property, which must be blocked during the credit period in order to secure the money. Only after the debt has been repaid is the property again unencumbered and can then be activated again to secure money.

This ability to activate unencumbered property to secure money (by creditors) and to secure the loan agreement through which it comes to the debtor, who has to pledge property in the amount of interest and repayment, is what Heinsohn and Steiger call property premium which is itself something incorporeal. At their job during the credit period the creditor interest and his debtor credit. In private property, patriarchy and the money economy , Heinsohn clarified his view of the connection between increased productivity and profit on the one hand, and accumulation and social inequality on the other:

- “The fulfillment of the additional property claim made in the interest claim on the debtor forces the production of more property than has temporarily come into his possession through the loan agreement. The interest demand resulting from the liquidity premium on property thus forces a surplus in production - profit. It is this interest-based profit that makes the accumulation typical of the property economy possible. "

Between 1997 and 2003, Heinsohn and Steiger (1938–2008) criticized the introduction of the euro in around thirty articles because a single currency could only function if the equity capital of the national central banks were of the same quality and the security requirements for the collateral accepted by the commercial banks were identical . Both conditions remained unfulfilled. As early as 1996, Heinsohn and Steiger described money that arises out of nowhere as “arbitrary money”. Also, “fluctuations in the value of the collateral” did not change the fact that “property that can still be encumbered and pledged is the basis for the creation of money and credit”.

This is where Bernd Senf's criticism began, because it gave the opportunity to deviate from the demand for land ownership, albeit with serious consequences. “At best, this security could be formulated as a necessary condition for the stability of money, but not as a description of reality,” he concluded.

In 1998, Nikolaus KA Läufer from the University of Konstanz dealt with the theses of the two authors in the concise paper The Heinsohn-Steiger confusion on interest, money and property . In the anthology Private Property and Money. Controversies about the approach of Heinsohn and Steiger from 1999 and 2012 with Axel Paul can be found in more detailed statements on the work of the two authors. In an event in 2000, the Money Museum of the Deutsche Bundesbank in Frankfurt confronted the core ideas of property, interest and money with the monetary theories of Aristotle , Adam Smith , Bernhard Laum and John Maynard Keynes . The courses at the Institute for Global Law and Policy at Harvard Law School are based on Gunnar Heinsohn and Otto Steiger's property economics . In a review in 2015 Ingo Sauer noted that Anglo-Saxon authors, sometimes without identifying the German-language discussions, would adapt the approach of Heinsohn and Steiger, such as David Graeber , who names the two authors in a footnote, or Felix Martin, who mentions the two authors don't seem to know. Fredmund Malik , who dealt with the transfer of the core ideas of "pioneering work" to the operational level, judged in 2016 that this approach corresponds to "the practical view of companies and especially that of the chief financial officers of commercial enterprises". The work is therefore of "inestimable practical value for effective leadership, control and design of the organizations in our complex society".

Genocide research

In 1993, on the recommendation of the French historian Léon Poliakov , Heinsohn founded Europe's first institute for comparative genocide analysis at the University of Bremen . This Raphael Lemkin Institute for Xenophobia and Genocide Research expired when Heinsohn retired in 2009. In 1997, Klaus von Münchhausen at the Lemkin Institute enforced compensation for forced laborers exploited under the Hitler regime .

In 1995, Heinsohn published Why Auschwitz? Hitler's plan and the perplexity of posterity . In it he opposed the generally accepted inexplicability of Adolf Hitler's motives in the extermination of the Jews . In view of Hitler's restoration of an “archaic right to infanticide” (internal) and the “extermination of living space” (external), Heinsohn identified the Jewish ethic of sanctity, also adopted by Christianity, as a decisive obstacle to Hitler’s world power policy. With the extermination of the Jews, this ethic should lose its bearer, while non-Jews were considered "curable". In 2014 he justified this thesis again in an English-language article that was soon to be translated into German.

1995 Heinsohn held (on mediation of the Foreign Office ) in Kigali little more than a year after the genocide in Rwanda a lecture on German history lessons to be learned for reconciliation between perpetrator and victim-ethnicities. In 1998, Heinsohn published the first genocide dictionary . In 1999 he was five years in the board of the newly established and Routledge appearing the Journal of Genocide Research appointed. There he published the essay What Makes the Holocaust a Uniquely Unique Genocide? The Routledge History of the Holocaust called Heinsohn's approach in 2010 "perhaps a more accessible explanation, at least of the guiding ideology". Encouraged by the Minister of State for Culture and Media Michael Naumann , Heinsohn designed an institute for genocide early warning ( Genocide Watch ) in 1999 . Naumann presented the concept in January 2000 at the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust . After Naumann left office, the federal government did not pursue the initiative for long. Neil Smelser and Paul Baltes invited Heinsohn one, for the International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences entry Genocide: Historical Aspects post that appeared 2,001th

Pre-school education, population policy

At the Free University in the 1970s, Heinsohn campaigned for early childhood education to be scientifically established by anchoring it in the university. His initial optimism of being able to improve the living conditions of entire population groups through early childhood education was formulated in his 1974 study of pre-school education in civil society . However, an inventory of socialization research justified his skepticism about the educational power of children's collectives with educators who have to spare their energy for their own family life. In 1979, Heinsohn was appointed to the advisory board of the newly founded magazine Kindheit . There he published a short world history of the next generation as the 'a priori' of childhood - the creation of intergenerational relationships from tribal societies to kibbutz .

In articles in Die Zeit and the FAZ in the 2000s, Heinsohn publicly worried about the supposedly declining “population quality” in Germany: To remedy this, he argued for a time limit on social assistance for single mothers in order not to further promote this type of family . The school failure of those growing up in this way should not be masked by lowering performance standards, as is widespread in his opinion. Likewise, the disproportionately high crime rate of these children should not be excused as a problem for society, if one does not want to drive their crime rate up further. These tendencies would help to drive capable Germans out of the country and to keep a potential new elite from abroad: "Why should they strive for a Western Europe that is already Islamically declining?"

These theses were taken up, among others, by the controversial non-fiction author Thilo Sarrazin in his bestseller Germany Abolishes Itself. The echo was mostly negative: Hans Endl classified his “tone” as “inhuman and biologistic ”, and the arguments were also directed against uneducated mothers. The political scientist Naika Foroutan accused Heinsohn of “degrading utilitarianism ”, but also of a demagogic use of numbers.

Religious studies

During his stay in Israel to study the economy and education of the kibbutz , Heinsohn took up the question of the origin of a universal ban on killing, including handicapped newborns, as had been set in motion by monotheistic Judaism. In his earliest demographic monograph Theory of Family Law. Abrogation of gender roles, neglect of children, declining births , this question about the deep ethical structure of the West ( Christianity took over the Jewish commandments) remained unanswered. At the universities in Haifa , Jerusalem and Tel Aviv , Heinsohn consulted experts on the origin of the so-called golden rule: “See, I presented you today with life and good. / I call heaven and earth today to witness against you: I have set before you life and death, blessing and cursing; therefore choose life. "( Deut 30.15 to 19 EU ) But besides these were also the invisibility and omnipotence of only God's, the Sabbath prohibitions as well as the circumcision on the eighth day - the core elements of Judaism - unexplained or provided with a multitude of contradicting theories.

Heinsohn presented his proposed explanations at the invitation of the sociologist Erik Cohen in 1977 at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Heinsohn saw the aforementioned core elements as compromises between supporters and rejecters of the blood sacrifice-determined "heavenly body religions" of the Near East (including ancient Israelites ) of the Bronze Age , which the Ugarit excavator Claude Frédéric-Armand Schaeffer (1898–1982) had first drawn attention to. Heinsohn is connected to Immanuel Velikovsky . He published an article on Velikovsky's theses in the journal “Freibeuter” in 1978. This started a more in-depth debate among amateur researchers in Germany. In 1982 Christoph Marx and Heinsohn founded the Society for the Reconstruction of Human and Natural History (GRMNG) . The club disbanded in 1988, however.

For Heinsohn, the end of the Bronze Age catastrophes opened the Axial Age ( Karl Jaspers ) with its upheavals and innovations in the history of ideas, including Jewish monotheism . The invisible, almighty God grew out of the struggle of the traditionalists with the astronomical scholars of the post-catastrophe period, who were able to prove safe orbits of the dreaded planets and thus declare them to be "nothing" ( Jeremiah 10: 2f.). They became mere heavenly hosts of an invisible but almighty force that did not really need a temple for them ( Isaiah 66: 1–2). The Sabbath prohibitions - no slaughter ( Exodus 16:23 ), lighting fires (Exodus 35: 3), cooking and no distance out of sight of the dwelling (Exodus 16:29) - were directed against the activities of the previous one Day of sacrifice when the creature to be sanctified was sacrificed far from the settlement on the heights ( Tofet ). Even the farmers were banned from slaughtering their homes and given to a slaughterer so that they could not be used to continue the animal sacrifice . According to Heinsohn, the eighth day of life ( Genesis 17: 10–14) of firstborns who were sacrificed to the ancient Israelites and Phoenicians reappears in circumcision . Finally, the ban on infanticide was intended to prevent the traditional blood ceremony from continuing under the guise of “ordinary” birth control infanticide.

From his studies of Judaism, Heinsohn found an analysis of hatred of Jews , which he has been investigating to the present day. In his view, the hatred of Jews began as a conflict between ancient Israelite-Canaanite victims, who refused to let go of the excitement discharge through the ritual, and the Jewish- monotheistic critics of sacrifice , for example by Flavius Philostratos (around 165/170 - after 244) were attacked in paganism : "Long ago the Jews rose not only against the Romans, but against all of humanity"; for they exclude themselves from “the burnt offerings, prayers and thanksgiving offerings”. Heinsohn sees the conflict between the God of Abraham , who spared the son, and the son-sacrificing God of Trinitarian Christianity, the longest lasting expression of the conflict.

But not only monotheism, but also the priesthood that preceded it, with temples and blood sacrifices, is considered misunderstood: “What legal or pious fiction or what economic or social pressure this attitude (the acceptance of the priesthood and blood sacrifice in Bronze Age Mesopotamia ) produced, we will probably never know ”( Adolf Leo Oppenheim ). At this stage of high culture, Heinsohn developed the thesis that the great rituals are to be understood as healing, in which the survivors of the catastrophes play out their trauma like children and who spent defensive aggression, which could not be removed by attack or flight, in collectively approved killing, in which animals or Humans represented inorganic heavenly bodies. If the ritually healed parishioners made gestures of reparation in front of their raised corpses, this bow was ultimately aimed at the overpowering forces of nature in the form of the people and animals who represented them. The organizers of the rituals, who assumed most of the blame for the ritual killing, were thanked by the congregations by providing them as priests who were venerated like master healers.

Historical demographics

For a historically oriented population theory under the title of human production. General population theory of modern times , Heinsohn and Steiger tried in 1979 to find an explanation for the European population explosion from the late 15th century. The underlying number of births per woman with an average of 5 to 6.5 children up to the 19th and 20th centuries became - in addition to the productively superior property economy - a condition for European world domination . In their view, the reasons for the demographic turnaround were the death penalties for birth control ( abortion , sterility, infanticide and abandonment) at least since the Constitutio Criminalis Bambergensis of 1507 and the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina of 1532.

But in addition, according to Heinsohn and Steiger, gynecology was also attacked. It is significant that the speculum , a central examination instrument in gynecology, disappeared in the Renaissance , an otherwise inventive epoch, although it had been in use since ancient times as speculum magnum matricis (found in Pompeii , Mérida ), during the Middle Ages as a dioptre be. It was not invented for the second time until the beginning of the 19th century by the French surgeon Joseph Récamier (1774–1852), which Heinsohn and Steiger in Why did the speculum have to be invented twice? Picked up again in 1987.

However, according to the authors' further argument, the death penalty on birth control from 1507 came around two decades too late for the onset of the population explosion. As John Hatcher noted, the roots of this phenomenon were between 1475 and 1485. For chronological reasons, a different process is possible. In 1484 Heinrich Kramer caused the Pope to publish the bull Summis desiderantes affectibus , the so-called "witch bull", the death penalty for "very many people of both sexes [...] who perish and cause the births of women [...] that the [...] ] Women [...] not received ”, as Heinrich Kramer alias Institoris commented. The legal commentary on the witch bull, the Malleus Maleficarum ( witch's hammer ) from 1487, makes it clear that in addition to all the magic that has always been forbidden, something new has been added. It was about a "sevenfold witchcraft", the individual procedures of which consistently "infect the act of love and conception in the womb with various bewitches". These birth control procedures should be explicitly pursued "apart from the multiple harms that they [the witches] cause to animals and crops".

The birth control bans from the witch bull and witch hammer have been assessed by Heinsohn and Steiger since 1979 as a model of population policy for the death penalties of the secular laws of 1507 and 1532 or as a driving factor behind the demographic change between 1475 and 1485.

Heinsohn did not deny the various other motives that embedded themselves in the witch hunt and that were cited by his critics. He countered them, above all Wolfgang Behringer , Gerd Schwerhoff and Gerhard Schormann as well as Walter Rummel , Franz Irsigler and Robert Jütte , that they did not take into account the express punishment of birth control maleficia as the new and historically powerful central document on witch persecution. The dispute over the monograph was soon also conducted in the media - especially in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung - especially since the work was quickly received by a broad public. Heinsohn and Steiger responded with feminism, professional witch research, legal history, and sexology. Answer to our critics to the first reactions of the professional world in the third edition of their book. John M. Riddle emphasized that in the 15th and 16th centuries the transmission of knowledge was broken: “The chain of knowledge transmission broke, and the chain of lay knowledge was largely interrupted […]. The authors of the Renaissance knew less about birth control than their medieval, Islamic and ancient predecessors ”. After reading The Destruction of Wise Women , he summed up another story of birth control: “In 1985 the sociologist Gunnar Heinsohn and the economist Otto Steiger, both from the University of Bremen, came to an amazing conclusion: the scientific revolution, the economic motives for The increase and the simultaneous suppression of witchcraft marked the destruction of wise women ”. According to Riddle, Heinsohn and Steiger “were the first to understand that the reaction of the leading authorities - political, academic and ecclesiastical leaders - was to be understood as a warning of low birth rates. The leading men blamed the 'secrets of women'. And they tried to eradicate this female knowledge by suppressing the art of witchcraft ”.

In 1999, with their essay Birth Control: The Political-Economic Rationale behind Jean Bodin's demonomania from their point of view , Heinsohn and Steiger rearranged Jean Bodin . Its justification for the witch hunt does not follow any mental derangement, but turns out to be a population policy guide for the punishment of birth control.

Other historians, in contrast to Heinsohn, saw the growing population as a problem for precisely these authorities. In addition, the number of midwives among the victims, the number of which has now been set much lower - Gerd Schwerhoff only assumes 40,000 to 60,000 deaths, previously numbers of up to nine million victims - was rather low and the reverse was emphasized Willingness of the "wise men" to cooperate in the persecution of those suspected of witchcraft. In addition, it was rather ruled out that the early modern state had such extensive possibilities at its disposal. The inconsistency and volatility of the persecutions in the European states and in North America speak against an overarching plan. In addition, there is little of contraception in the trial files.

War demographics

In 2003 Heinsohn published Sons and World Power. Terror in the rise and fall of nations . For Gaston Bouthoul's finding that there is a strong imbalance between career-seeking young men and available social positions, Heinsohn determined that the youth bulge required for this was at least 30% of the 15 to 29-year-olds compared to the male Total population. In 2003, he outlined the potential that will break out in the “ Arab Spring ” from 2011 on, especially for the Arab region, including the Palestinian territories . An extensive debate arose around the theses in the book , in which Reiner Klingholz ( Do young men make war? ) Turned against them, while sociologists working with Uwe Wagschal joined them with their own investigations. Klingholz criticized the lack of "statistical basis for the theory of the war-prone overhang of young men". He traced Heinsohn's thesis back to a study by the CIA from 1995, objected that the thesis did not seem to apply to countries like Brazil or Botswana , and countered it with the findings of the Berlin demographer Steffen Kröhnert , which were only published after Heinsohn's book . For Kröhnert, among other factors that triggered the war, including the lack of prospects among young people, the lack of education and the prolonged rule of encrusted dictatorships were among the causes of war. In addition, there is the “denationalization” of the wars ( Herfried Münkler ). In addition, the following applies: “The number of wars and armed conflicts has been around 6 to 7 disputes per billion people on earth for decades.” If the “surplus of young people” was even over 21%, statistically speaking, the probability of war fell; Kröhnert attributes this to the fact that the 15 to 24-year-olds are often parents again themselves, which means that there is hardly any “youth surplus”. Yet “most of the countries involved in conflict are poor and poorly developed. It is therefore conceivable that the risk of war is only related to economic (under) development, which in turn is associated with high birth rates. "Youth surpluses" over 21 percent [...] can only arise in countries with previously high birth rates, in which the number of children within a short period of time have fallen significantly ”, he concedes that the youth share could be a“ demographic stress factor ”,“ which can contribute to the outbreak of violence if the state does not offer its people any economic development opportunities. ”It remains unclear whether it is“ merely an expression of the level of social development is what favors wars ”.

The philosopher Peter Sloterdijk , who described Heinsohn as “a highly stimulating scholar who repeatedly transcends the narrower disciplines for scientific benefit”, described Heinsohn's book Sons and World Power as “required reading for politicians and columnists”. In 2005 the Federal Intelligence Service invited Heinsohn to give a lecture How will the world develop? - Crisis situation in [sic!] 2020 . After his essay Babies win wars , the City Forum of London asked him to give a lecture to NATO commanders on demography and war . In a second lecture held there, he analyzed the conflicts in Afghanistan and Pakistan from the fact that for decades there had been more than six children per woman's life.

These and other publications accused Heinsohn of being "NATO's demographer" in the New Left Review . From 2009 to 2012, Heinsohn gave lectures on the interaction between war demography and martial law at the Federal Academy for Security Policy , and since 2012 he has been teaching at the NATO Defense College in Rome, among other things, that interventions by Western states will decline because - statistically speaking - they endanger only sons or even only children would to fight third or fourth brothers.

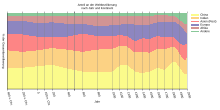

To estimate the number of victims and the duration of conflicts driven by a surplus of young men, he developed a “war index” in 2011, which measures the ratio between 15 to 19 year olds who enter into a struggle for life and 55 to 59 year olds who retire approach. With an index of 6 (examples Afghanistan, Gaza or Uganda ; for comparison Germany 0.66), there are 600 young men for every 100 retirees. With index values of 3 to 6, tensions ranging from increasing violent crime to armed conflicts are likely. However, the war index is not a sufficient explanation for violence; rather, an index between 3 and 7 as well as economic development are required, ultimately “so relatively well-trained, nourished and medically cared for young people”. The dynamics behind the First World War or Europe's pacification after the Second World War could, according to Heinsohn, be better explained in this way. Conversely, war fatigue can also be seen in individual cases as a decrease in the number of children. In addition, his approach offers a partial explanation for the "global migration" and some of its consequences.

The professor emeritus for politics and economics Mohssen Massarrat criticized in the Frankfurter Rundschau that the population development in Bangladesh , China and Brazil did not match Heinsohn's theory. In addition, he described Heinsohn's postulate that international aid organizations should stop promoting “child production” in crisis areas and developing countries as “ cynical ”.

History, chronology

Heinsohn distrusts some of the dating methods and relies largely on stratigraphic research. He demanded that scientific dating procedures should only be used in blind tests, in which the experts received no information about the test materials and had to publish widely differing results. As early as 1987 he postulated - at the time opposed to the biblical chronology advocated by Immanuel Velikovsky himself - that for the course of human history it is not layers of ice, tree rings , astronomical constellations or the usual dates of coins and rulers, but only the sequence of cultural layers found in archaeological sites Must have priority. In contrast to Heinsohn's approach, it is otherwise not assumed in archeology that two layers that are directly on top of each other at an excavation site must also follow one another in time. Entire epochs can be left out in the sequence of layers because the excavated area was not inhabited at the time, because layers have eroded or because layers have been removed, for example in order to obtain a flat surface for new buildings. For example, excavations and surveys in Uruk have shown that in some places layers of temporally distant epochs are directly adjacent to one another, while in other places finds from other epochs lie in between. The chronologies of the Middle East and the Eastern Mediterranean are being researched further within the framework of the international ARCANE project, this “has revealed growing discrepancies between the results of C14 datings and those of empirical chronologies based on archaeological sequences, the former being usually much higher than the latter would suggest. It appears that these discrepancies are of different magnitude according to various areas. ”In addition to stratigraphic dating, dating methods that Heinsohn rejects, such as C 14, tree rings and written sources, are used as a basis.

Antiquity: Kaldu and Sumer, Mitanni, Medes and Achaemenids, Hyksos

In particular, Heinsohn was concerned with the supposed untraceability of Chaldea , which was considered the cradle of high culture and mathematics by Jews (such as Flavius Josephus ) and Greeks ( Abydenus , Alexander Polyhistor or Apollodor ) well into the 19th century . After all, according to the ancient orientalist Dietz-Otto Edzard in the Real Lexicon of Assyriology and Near Eastern Archeology , the Chaldeans ( Kaldu ) lived in “88 strong, walled” and in 820 small towns in “up to two thirds of Babylonia”. “[Nevertheless] no material is known about the language of the K [aldu]” and “We have so far no idea about the religion of the K [aldu]”.

But in the Chaldea region - with identical city names such as Borsippa or Uruk - the land “Sumer” was discovered, which is now considered the cradle of high culture and mathematics. It was unknown until 1869, when the ancient orientalist Jules Oppert was the first to call it that: “I have used this name [Sumer] since 1869”, as he himself wrote in 1875. He dated the biblical land of Shinar about 1500 years before Chaldea via "the time of Abraham". In its own script, however, Sumer does not mean “Sumer”, but “Kalam”. Since the Ur- III Sumerian strata were found only two strata groups under the Hellenistic , they would also fit archaeologically to a Chaldean kalam. When Chaldea was reinstated in its material inheritance, the name Sumer would be omitted, which Heinsohn did not want to express with the book title The Sumerians existed . Heinsohn's theses about the Sumerians had no influence on Assyriology or its specialty Sumerology. For example, in the real dictionary of Assyriology under the headings “Sumer, Sumerian” and “Sumer, history”, not a single one of Heinsohn's theses is adopted or discussed as a possibility. Heinsohn is also not mentioned in Dietz Otto Edzard's, History of Mesopotamia. Jules Oppert discovered the term Sumer in Akkadian cuneiform texts that had only been deciphered a few years earlier. It is a meanwhile naturalized foreign name for language and country from which the popular name Sumerer in German is derived, just like the German word Greek, from the Latin Graeci.

In addition to Chaldäa, Heinsohn also defended the Medes empire that coincided with him , which was the first large Indo-Aryan empire of horse breeders to be in the history books until the mid-1980s, but since then, according to Robert Rollinger , has been disproved: “Until about 20 years ago the existence of a Median 'great empire' that immediately followed the fall of Assyria and ruled large parts of the Middle East for about half a century, until the alleged vassal of the last Medieval king Astyages, Cyrus II , conquered his overlord and inherited his empire as confirmed historical fact. [...] The image of the formation of the Median empire offered by the classical tradition - primarily from Herodotus - may be considered refuted by the Neo-Assyrian sources and may not claim historical credibility ”. In the area of the Medes one finds another empire of Indo-Aryan horse breeders, dated 800 years earlier, who are known as Mitanni , but were also unknown until 1885. Since Mitanni strata were found only two strata groups among those of Hellenism, Heinsohn identified the Mitanni as Medes.

Just as isolated as with the Chaldeans and Medes, Heinsohn remained with his defense of the Achaemenid Empire, to which since 1990 only the Iranian core areas have been granted, but the imperial dimensions represented up to then have been denied. Since Alexander the Great brought Hellenism to Asia through the victory over the Achaemenids , Heinsohn proposed that the layers directly under the Hellenistic excavation layers be assigned to the empire of the Achaemenids. He considers the Assyrians and Babylonians with their rich architectural layers, originally dated up to 1500 years earlier via Abraham's Bible date, to be the inhabitants of the Achaemenid region, richest after Herodotus, with the satrapies Athura and Babiru. However, Ev Cochrane contradicted his equation of Hammurabi and Darius . Heinsohn defended the imperial dimensions of the Achaemenid Empire and thus also the metropolis of its Indian satrapy. He identified their capital Mujika (under King Musikanos ), conquered by Alexander's general Krateros and not yet found, with Mohenjo-Daro , which was dated 1500 years earlier. According to Heinsohn, this goes back to the original chronological anchoring with Abraham.

In 1991 the Sixth International Egyptologists' Congress invited Heinsohn to present his Declaration of the Hyksos (17th / 16th century BC). Their reuse of cuneiform writing and certain weapons ( scimitar ) of the old Akkadians, which were chronologically around 600 years before them, has always been known . Since archaeological layers of the Mitanni - Medes for Heinsohn - follow layers of the Hyksos just as directly as in other sites on those of the Old Akkadians, Heinsohn suggested equating the two.

On the history of Israel in biblical literature

Against the removal of the ancient Israelite kings from the 11th to 7th centuries BC Heinsohn objected that the missing archaeological evidence had just been looked for in the wrong place. If one were to use the Amarna letters of the Mitanni period (dated to the 14th century), there are two names there, the Apiru [Habiru] princes Jishua and Dadua, which are similar to those of the Hebrew princes Jischai and his son David . While David and his Hebrews fought Jebu people in the 11th century in order to get hold of Jerusalem, the Jerusalem prince Abdi-Chepa asked in Amarna in the 14th century for help against attacking Apiru: “On closer inspection, certain details of the biblical narrative are Almost identical to the descriptions of the Apiru gangs in the Amarna letters, ”also conceded Israel Finkelstein and Neil A. Silberman , but in their view the biblical David story took place“ four hundred years later in the same region ”(p. 46). When other Israeli archaeologists excavate capitals in Jerusalem and assign them to David's palace, Finkelstein believed that these were from the 7th / 6th centuries. Century the Medes date.

Late antiquity, early Middle Ages

Since 2011, Heinsohn has been pursuing the question of why, in his opinion, there is no archaeological site that has consistently provided artifacts from the turn of the century to around 1000 . One is sure to be in a continuum over time periods of around 300 years for construction layers, which are, however, placed in very different chronological terms, namely either in the three centuries up to 300, the time between 300 and 600 or the time between 700 and 1000. Theirs is at the same time effective material culture similar and the sites would mostly show Roman coins, which would be assigned to the time from approx. 1 to 235 according to the current chronology based on the dates of the rule of the Roman emperors .

This work ended the cooperation with Heribert Illig and led to Heinsohn's departure from the editorial team of Zeitensprünge . Since then, Heinsohn has defended the existence of Charlemagne against Illig . However, Heinsohn postulated that Karl was not a medieval figure, because his buildings - such as the Palatinate in Ingelheim - are in the form and technology of Roman villas of the 1st / 2nd centuries. Century are not easy to distinguish. Heinsohn did not mean that Karl was dated too late - he argued against the fact that the upper part of the villa was directly connected to the Ottonian 10th century, which should be considered certain - but that the Roman period was too early.

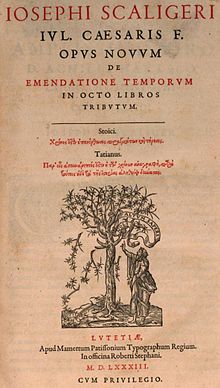

The fall of Rome was also discussed again, as, according to Heinsohn, there are extensive traces of catastrophe in all three 300-year blocks (in the 230s, 530s and 930s). According to Heinsohn's conclusion, it was likely to have been a single, but comprehensive, catastrophe, which is reflected in layers of earth and rubble at many excavation sites. The current chronology is relatively young. Only Joseph Justus Scaliger (1540-1609) was the first in his work de Opus emendatione Tempore set up a chronology, all ancient chronologies have tried to integrate. However, Heinsohn sees no intention to forgery in the extended chronicle, like Illig, but believes he recognizes the cause in the said catastrophe, which took place around 930.

Publications

Works (selection)

- Preschool Education and Capitalism. A sociological investigation of the causes, system-changing possibilities and implementation difficulties of reform efforts in the preschool education of capitalist Germany , Frankfurt am Main 1971.

- with Barbara MC Knieper: Theory of Kindergarten and Play Education. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1975 ( es 809). ISBN 3-518-00809-9 .

- with Rolf Knieper's theory of family law. Abrogation of gender roles, child neglect, decline in birth rates. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1976 ( edition suhrkamp 747). ISBN 3-518-00747-5 .

- with Rolf Knieper and Otto Steiger : Human Production. General population theory of the modern age. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1979. ISBN 3-518-10914-6 .

- as editor: The Kibbutz Model. Inventory of an alternative economy and way of life after seven decades. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1982 (es 998). ISBN 3-518-10998-7 .

- Private property, patriarchy, monetary economy, social-theoretical reconstruction of antiquity . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1984 (Suhrkamp pocket book science 455). ISBN 3-518-28055-4 .

- with Otto Steiger : The annihilation of wise women. Contributions to the theory and history of population and childhood. March, Herbstein 1985. ISBN 3-88880-057-9 (14th edition, with a detailed, updated epilogue to the fourth, extended new edition: March — Area, Erftstadt 2005. ISBN 3-89996-340-7 .)

- What is anti-Semitism? The origin of monotheism and hatred of Jews . Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main, 1988. ISBN 3-8218-0418-1 .

- The Sumerians did not exist. From the phantom empires of the textbooks to the real sequence of epochs in the "cradle of civilization" of southern Mesopotamia; Presentation of the problems and suggestions for their solution in a chronological overview. Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main 1988. ISBN 3-8218-0411-4 .

- with Heribert Illig : When did the pharaohs live? Archaeological and technological foundations for rewriting the history of Egypt and the rest of the world. Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main, 1990. ISBN 3-8218-0422-X . (Third, corrected edition: Mantis, Graefelfing 1999. ISBN 3-928852-20-5 .)

- How old is the human race? Stratigraphic foundation of paleoanthropology and prehistoric times. Mantis, Graefelfing, 1991. ISBN 3-928852-25-6 . (Fourth, corrected edition: Mantis, Graefelfing 2004, 6th edition 2009. ISBN 3-928852-25-6 .)

- Who ruled in the Indus Valley? The rediscovered empires of the Medes and Persians. Mantis, Graefelfing, 1993. ISBN 3-928852-07-8 (2nd edition 1997).

- Why Auschwitz? Hitler's plan and the perplexity of posterity. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg, 1995. ISBN 3-499-13626-0 .

- Property, interest and money. Unsolved puzzles of economics. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1996. ISBN 3-89518-494-2 . (Seventh edition: Metropolis, Marburg 2010. ISBN 978-3-89518-844-2 .)

- Beginning and end of the climate madness . Management Zentrum St. Gallen, St. Gallen 1996, second extended edition 1997, as well as in: Leviathan 4 (1996) 445–455.

- The creation of the gods. The sacrifice as the origin of religion. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg, 1997. ISBN 3-498-02937-1 , 2nd, revised edition, 2012.

- Lexicon of Genocides. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg, 1998. ISBN 3-499-22338-4 .

- Sons and world power. Terror in the rise and fall of nations. Orell Füssli, Zurich 2003. ISBN 3-280-06008-7 . (Second, expanded edition 2006; as a paperback from Piper, Munich – Zurich 2008. ISBN 978-3-492-25124-2 , online , PDF, 3.6 MB)

- with Otto Steiger: Property Economics . Metropolis, Marburg 2006. ISBN 3-89518-534-5 , second, revised edition 2008.

- with Otto Steiger, ed. Frank Decker : Ownership Economics. On the Foundations of Interest, Money, Markets, Business Cycles and Economic Development . Routledge, New York 2012. ISBN 978-0-415-64546-1 .

- Competition for the clever. Competence, Education and the Welfare of Nations , Orell Füssli, Zurich 2019. ISBN 978-3280057070

Media contributions

- Foreigners are the solution ... , in: Focus, July 26, 2010.

- America urgently needs more immigrants , in: Die Welt, June 7, 2015.

Honors

The New Direction: The Foundation for European Reform , initiated by Margaret Thatcher in 2010, presented the "Liberty Award" for its "contribution to an open-minded and honest political debate" at the Fondation Universitaire Heinsohn in Brussels on June 15, 2016 . In addition to his merits on democracy and economy, the focus was also on his services to the German-Polish relationship.

literature

- Florin Diacu: The lost millennium. History's timetables under siege , Alfred A. Knopf Canada, Toronto 2005, ISBN 0-676-97657-3 (Second edition. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2011, ISBN 978-1-4214-0287-1 ).

- Jan Beaufort, Frank Decker (Ed.): “Property, Interest and Money” after 20 years. Festschrift for Gunnar Heinsohn , Metropolis, Marburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-7316-1228-5 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Gunnar Heinsohn in the catalog of the German National Library

- Market of Illusions: How Credit Lost Its Credit , ZDF, November 30, 2008 (59:29 min); Peter Sloterdijk on property, interest and money : 56: 15–57: 06 min.

- The Philosophical Quartet: Halftime of the Crisis , contribution on ZDF from 2009.

- Is Europe threatened with a third world war? , Contribution on ZDF from 2009.

- Rush to Europe , Spiegel TV, 2011

- Nachtstudio , ZDF, 2010, Interview by Volker Panzer with Gunnar Heinsohn, 2011 (on the ban on infanticide, the emergence of Judaism and the Holocaust, questioning of chronology and the theory of disasters, property economics and the debt crisis, "youth bubble", loss of innovative strength, immigration and the welfare state)

Remarks

- ^ Entry Heinrich Heinsohn on: German U-Boats 1935–1945 (ubootarchiv.de).

- ↑ Dagmar Hartung-von Doetinchem and Ulf Heinsohn, Roswitha, Henry and their three sons , Berlin 2010, p. 135.

- ^ Jürgen Plieninger: Review of the Lexicon of Genocides , in: Informationsmittel für Libraries 7 (1999).

- ^ Profile and post list of Gunnar Heinsohn on the Axis of the Good .

- ↑ No. 35, 4th quarter 1997.

- ↑ Heinsohn, Otto Steiger: The destruction of wise women. Contributions to the theory and history of population and childhood . March, autumn 1985.

- ↑ Gunther Franz, Franz Irsigler (ed.): Methods and concepts of historical witch research , Trier, Paulinus 1998, p. 23.

- ↑ Walter Rummel: Wise Women as Victims? in: Gudrun Gersmann , Katrin Moeller, Jürgen-Michael Schmidt: Lexicon for the history of witch persecution , at historicum.net , December 2003. Accessed on September 27, 2014.

- ↑ Dietmar Herz and Veronika Weinberger: Lexicon of economic works , economics and finance, Düsseldorf 2006, pp. 186–190. - It is about: Gunnar Heinsohn with Rolf Knieper and Otto Steiger : People production. General population theory of the modern age , Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1979; Gunnar Heinsohn: private property, patriarchy, money economy , Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1984; Gunnar Heinsohn, Otto Steiger: Property, Interest and Money. Unsolved riddles in economics , Rowohlt, Reinbek 1996, seventh edition: Metropolis, Marburg 2010.

- ↑ This lecture at the University of Frankfurt from 2019 offers an understandable presentation .

- ^ Heinsohn and Steiger: Property, interest and money , p. 247.

- ↑ Hans Christoph Binswanger after Peter Müller: A few percent dispute: He was hated and loved, allowed and forbidden. A little history of interest , in: Die Zeit , February 17, 2003.

- ^ Heinsohn: Private property, patriarchy and money economy , p. 233.

- ↑ The main articles are here: Gunnar Heinsohn, Otto Steiger: The Euro Debate: A Weak Bank Means a Weak Euro , in: The Wall Street Journal Europe, July 1, 1997; this .: Three Achilles heels of the euro: Deficiencies in the new monetary order in Europe , in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung No. 50, March 2, 1999; This: The Eurosystem and the Art of Central Banking , in: Studi economici 76 (2002) 5–30.

- ^ Heinsohn and Steiger: Property, interest and money , p. 441.

- ^ Heinsohn and Steiger: Property, interest and money , p. 229.

- ↑ Bernd Senf: The Copernican turn in the economy? An appreciation and criticism of the book "Property, Interest and Money" by Gunnar Heinsohn and Otto Steiger, in: Zeitschrift für Sozialökonomie (1999), p. 16.

- ↑ Nikolaus KA Läufer: The Heinsohn-Steiger confusion on interest, money and property (PDF) , June 26, 1998.

- ^ Karl Betz, Tobias Roy (ed.): Private property and money. Controversies around the approach of Heinsohn and Steiger , Metropolis, Marburg 1999.

- ↑ Axel Paul: The society of money. Draft of a monetary theory of modernity , Springer-Verlag, second expanded edition 2012, esp. P. 164ff.

- ↑ Again on March 9, 2014 in Cash Development and Cash Demand (PDF) ( Memento of the original from September 24, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , ed. from the Deutsche Bundesbank .

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn & Otto Steiger, The Paradigm of Property, Interest and Money and its Application to European Economic Problems .

- ^ David Graeber: Debt. The First 5,000 Years , Melville House, New York, p. 396, in German: Debt. The first 5000 years , Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2012.

- ^ Felix Martin: Money. The Unauthorized Biography , Bodley Head, London 2013.

- ↑ Fredmund Malik: Property Economics Corporate Management, in: Jan Beaufort, Frank Decker (Ed.): “Property, Interest and Money” after 20 years: Festschrift for Gunnar Heinsohn , Metropolis, Marburg 2016, 199-225, here: p. 200.

- ↑ On property economics, Malik explains: “Their knowledge enables managers to better understand the complexity and dynamics of their organization…. It is particularly helpful to discover and understand the long-established deflationary developments and thus also to navigate properly. ”(Fredmund Malik: Property economics corporate management , in: Jan Beaufort, Frank Decker (ed.): “ Property, interest and money ” after 20 years: Festschrift for Gunnar Heinsohn , Metropolis, Marburg 2016, 199-225, here: p. 223).

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn: What do Hitler's work slaves cost today? , in: Die Zeit, October 31, 1997, and this: A righteous man? What Stuart Eizenstat hides in his book about the Jewish forced laborers , in: Literarian Welt (supplement for Die Welt ), June 14, 2003, p. 5.

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn: Hitler's Motive for the Holocaust , in: Wolfgang Bialas, Lothar Fritze (Ed.): Nazi Ideology and Ethics , Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Cambridge 2014, pp. 103–126, and ders .: Hitler's Holocaust Motive , in : Wolfgang Bialas, Lothar Fritze (eds.): Ideology and Moral of National Socialism , Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014, pp. 109–128.

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn: Post-Genocidal Reconciliation in Rwanda: Are there Lessons from Germany? , Series of publications by the Raphael Lemkin Institute for Xenophobia and Genocide Research, Bremen 1997.

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn: What Makes the Holocaust a Uniquely Unique Genocide? (PDF) , in: Journal of Genocide Research 2,3 (2000) 411-430.

- ↑ Saul S. Friedman : Conclusion , in: Jonathan C. Friedman (ed.): The Routledge History of the Holocaust , Routledge, London – New York 2010, pp. 507-510, here: p. 509.

- ^ Naumann's lecture at the Stockholm International Forum .

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn: Genocide: Historical Aspects , in: International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Elsevier Science, Amsterdam et al. 2001, pp. 6153-6159.

- ↑ See his study Pre-School Education - Sociological Study on the Structure of a 'Central Pre-School Education ' , in: Pressedienst Wissenschaft der FU Berlin, No. 2, 1972, which he wrote together with Jens Beiderwieden.

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn: Pre-school education in civil society , S. Fischer, Frankfurt 1974.

- ↑ See Gunnar Heinsohn, Rolf Knieper: Infant education as wage labor , in: Elke Finkbeiner, Marei Hartlaub, Gabriele Kallmeyer (ed.): Reading book for educators , vol. 1, Lexika Verlag, Grafenau 1975, pp. 171-175, and Gunnar Heinsohn, Barbara MC Knieper: Theory of kindergarten and play education , Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1975.

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn: The 'a priori' of childhood - the bringing about of generational relationships from the tribal societies to the kibbutz , in: Childhood. Journal for research into psychological development 2,4 (1980) 301–323.

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn: Finis Germaniae? Reflections on the demographic causes of revolutions, wars and political defeats . zeit.de, February 6, 2008; same: limit social assistance to five years . faz.net March 15, 2010; both quoted from Andreas Kemper : Sarrazin's German-language sources . In: Michael Haller, Martin Niggeschmidt (Hrsg.): The myth of the decline of intelligence: From Galton to Sarrazin: The thought patterns and thinking errors of eugenics . Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2012, p. 62 f.

- ^ Andreas Kemper: Sarrazin's German-language sources . In: Michael Haller, Martin Niggeschmidt (Hrsg.): The myth of the decline of intelligence: From Galton to Sarrazin: The thought patterns and thinking errors of eugenics . Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2012, p. 62 f.

- ^ Benno Schirrmeister: Steep theses against the unemployed. "Agitation has become socially acceptable" , in: Die Tageszeitung , April 6, 2010.

- ↑ Naika Fouroutan: The calculations are demagogic , in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, September 16 of 2010.

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn: Pre-school education in the kibbutz , in: M. Monika Niermann (Ed.): Dictionary of pre-school education, vol. 1, source and Meyer (UTB), Heidelberg 1979, pp. 152–154; ders. (Ed.): The kibbutz model. Inventory of an alternative economy and way of life after seven decades, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1982.

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn, Rolf Knieper: Theory of Family Law. Abrogation of gender roles, child neglect, declining birth rates , Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1974.

- ^ Scott Cohen: A Portrait of Erik Cohen .

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn: The Origin of Monotheism and the Prohibition of Killing , lecture at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem, May 31, 1977.

- ^ Article Claude-Frédéric-Armand Schaeffer , in: Encyclopedia Britannica .

- ↑ “Our investigation has shown that the successive faults that introduced and ended the epochs of the 3rd and 2nd millennia were not brought about by human hands. On the contrary: Compared to the extent of these all-encompassing crises and their far-reaching consequences, the exploits of military conquerors and the attacks of political leaders seem downright futile ”(translated from Claude Frédéric-Armand Schaeffer: Stratigraphie comparée et chronologie de l'Asie Occidentale (IIIe et IIe millénaires ) , Oxford University Press, London 1948, p. 565).

- ↑ See Gunnar Heinsohn: Theory of the prohibition of killing and monotheism among the Israelites as well as the genesis, enforcement and world-historical role of Christian family and reproductive morals , in: Joachim Müller, Bettina Wassmann (ed.): L'invitation au voyage zu Alfred Sohn-Rethel (Festschrift for Alfred Sohn-Rethel on his 80th birthday) , Wassmann University Bookstore, Bremen 1979, issue No. 7; Gunnar Heinsohn: Monotheism and anti-Semitism - forever inexplicable? in: Rainer Erb , Michael Schmidt (ed.): Anti-Semitism and Jewish history. Studies in honor of Herbert A. Strauss , Wissenschaftlicher Autorverlag, Berlin 1987, pp. 409–447.

- ↑ Most recently The hatred of Jews in the United Nations is excessive , in: WeltN24, 23 September 2016.

- ↑ See Menachem Stern : Greek and Latin Authors on Jews and Judaism , Vol. 1: From Herodotus to Plutarch , The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Jerusalem 1976, p. 341.

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn: What is anti-Semitism? The origin of monotheism and hatred of Jews , Eichborn, Frankfurt 1988; ders .: What is Judaism? Ancient Israelitism / Christianity and Jewish Monotheism: Difference and Conflict , in: Zeitschrift für Religions- und Geistesgeschichte 43,4 (1991) 333–344.

- ^ "What legal or pious fiction or what economic or social pressure conditioned this attitude [the acceptance of priest-kingship and blood-sacrifice in Bronze Age Mesopotamia] we shall probably never know". Quoted from Adolf Leo Oppenheim: Ancient Mesopotamia (PDF) , revised edition, University of Chicago Press, 1977, p. 97.

- ↑ In addition: Gunnar Heinsohn: The Rise of Blood Sacrifice and Priest-Kingship in Mesopotamia: A “Cosmic Decree”? , in: Religion. A journal of religion and religions 22 (1992) 309-334; ders .: The creation of the gods: The sacrifice as the origin of religion , Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1997; New edition by Mantis, Graefelfing 2012; English since 2013 as: The Creation of the Gods , at q-mag.org .

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn, Rolf Knieper, Otto Steiger: People production. General population theory of the modern age , Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1979, second edition 1982.

- ↑ On this already Magnus Hirschfeld : Sex and crime , ed. JR Spinner, Vienna 1930, p. 8.

- ↑ Ornella Moscucci: The Science of Woman. Gynaecology and Gender in England, 1800-1929 , Cambridge University Press, 1990, p. 112.

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn, Otto Steiger: Why did the speculum have to be invented twice? , in: Critical Justice. Quarterly journal for law and politics 20.2 (1987) 200-207.

- ^ John Hatcher : Plague, Population and the English Economy 1348-1530 , Macmillan, London 1977, p. 63.

- ↑ Jakob Sprenger, Heinrich Institoris: Malleus Maleficarum. The Hexenhammer [1487], ed. JWR Schmidt, H. Barsdorf, Berlin 1906, reprint: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1974, three volumes, here: Vol. I, p. XXXVII.

- ↑ Sprenger, Institoris: Malleus Maleficarum , Vol. I, p. 107.

- ↑ For example Gunnar Heinsohn, Otto Steiger: Jean Bodin, the 'universal genius of the modern age' or: the true master thinker - nine theses on population theory , in: European Demographic Information Bulletin 10.3 (1979) 97-108; Gunnar Heinsohn, Rolf Knieper, Otto Steiger: Human production. General Population Theory of the Modern Age , pp. 55–58; Gunnar Heinsohn, Otto Steiger: The annihilation of wise women. Contributions to the theory and history of population and childhood , March, Herbstein 1985.

- ↑ Wolfgang Behringer: The threat of the damaging spell. About the rules of scientific work. An answer to Heinsohn and Steiger , in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, October 7, 1987.

- ↑ Gerd Schwerhoff, who reviewed the work ( Geschichtsdidaktik 11 (1986) 95-97, on this the reply of the authors ibid., Pp. 420-422 and again Schwerhoff: Reply to the anti-criticism of G. Heinsohn / O. Steiger , ibid P. 422 f.) Summarized in witchcraft, gender and regional history , in: Gisela Wilbertz , Gerd Schwerhoff, Jürgen Scheffler (eds.): Witch persecution and regional history. Die Grafschaft Lippe in comparison , Bielefeld 1994, pp. 325–353, the criticism from witch trial research together (pp. 336–338).

- ^ Review by Gerhard Schormann, in: Der Staat 25 (1986) 635 f.

- ↑ Walter Rummel: "Wise" women and "wise" men in the fight against witchcraft: The refutation of a modern fable , in: Christoph Dipper , Lutz Klinkhammer , Alexander Nützenadel (ed.): European social history. Festschrift for Wolfgang Schieder , Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2000, pp. 353–375.

- ↑ Franz Irsigler et al .: Hexenwahn. Fear of the Modern Era, volume accompanying the exhibition in the German Historical Museum Berlin, Wolfratshausen 2002, p. 13.

- ^ Robert Jütte: The persistence of the knowledge of contraception in folk culture. Social and medical-historical notes on the thesis of the 'annihilation of wise women' , in: Medizinhistorisches Journal 24 (1989) 214-231.

- ↑ Wolfgang Behringer: The reason of magic. The persecution of witches as a topic of European history , in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, August 19, 1987, and the same: The threat of harmful magic. From the rules of scientific work. An answer to Heinsohn and Steiger , in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, October 7, 1987; Heide Wunder : The complex connections between the persecution of witches , in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, November 12, 1987.

- ↑ This happened in the third expanded edition: The destruction of wise women. Witch persecution, children's worlds, population science, human production. Contributions to the theory and history of population and childhood. With a detailed, updated and expanded afterword as well as a register for the new edition , third extended edition, Munich 1985, pp. 369–427.

- ^ After John M. Riddle: Contraception and Abortion from the Ancient World to the Renaissance , Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1992, p. 157.

- ↑ John M. Riddle: Eve's Herbs. A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West , Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1997, p. 167.

- ↑ John M. Riddle: The great witch hunt and the suppression of birth control: The theory of Heinsohn and Steiger from the perspective of a historian , in the appendix by: Gunnar Heinsohn, Otto Steiger: The destruction of the wise women , March Area, Erftstadt-Lechenich 2005, p. 472 f.

- ^ Jean Bodin: De la demonomanie des sorciers , J. de Puys, Paris 1580; Reprinted by Olms, Hildesheim 1988.

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn, Otto Steiger: Birth Control: The Political-Economic Rationale behind Jean Bodin's Demonomanie , in: History of Political Economy, 31.3 (1999) 423-448.

- ^ Gerd Schwerhoff: From everyday suspicion to mass persecution. Recent German research on early modern witchcraft in: History in Science and Education 46 (1995) 359–380, here: p. 362ff.

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn: Sons and World Power. Terror in the Rise and Fall of Nations , Orell and Füssli, Zurich 2003.

- ↑ Gaston Bouthoul: Traité de polémologie. Sociologie des guerres , 1970, Payot, Paris 1991, et al .: Child murder for reasons of state. The war as a settlement in terms of population policy , Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1972.

- ↑ Sons and World Power. Terror in the rise and fall of nations , Orell and Füssli, Zurich 2003, pp. 32, 42, 125, 148, 157.

- ↑ a b Reiner Klingholz: Do young men make war? , in: Die Zeit, February 26, 2004.

- ↑ Uwe Wagschal , Thomas Metz , Nicolas Schwank : A 'demographic peace?' The influence of population factors on internal and international conflicts. In: Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 18.3 (2008) 353–383.

- ^ Steffen Kröhnert: Youth and the danger of war. What influence do demographic changes have on the development of conflicts? (PDF) , Berlin 2004, p. 7.

- ^ Steffen Kröhnert: Youth and the danger of war. What influence do demographic changes have on the development of conflicts? Berlin 2004, p. 12.

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn: War against Islamism. Gunnar Heinsohn does not give an offensive action by the West a chance , in: Handelsblatt , November 8, 2015.

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn: Afghanistan, Russia, and the War Index , in: The Weekly Standard, August 10, 2017.

- ↑ Peter Sloterdijk: Text on the Philosophical Quartet ( Memento from September 24, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) from October 26, 2009, at archive.org.

- ^ Peter Sloterdijk, in: Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger, August 1, 2006.

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn: Babies win wars , in: The Wall Street Journal, March 6, 2006.

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn: Demography and War (PDF), lecture manuscript.

- ↑ Clark Whelton: A Demographic Theory of War , in: The Weekly Standard, October 5, 2007.

- ^ Göran Therborn: NATO's demographer , in: New Left Review (March-April 2009).

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn: How many deaths there will be in Syria , in: Focus , June 11, 2012.

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn: Civil War Index of the Arab uprisings ; ders .: Outsider, lightning rod. Demography: Why the uprisings in Arabia are often directed against Israel , in: Jüdische Allgemeine , February 24, 2011.

- ↑ Interview with Gunnar Heinsohn at rbb , September 2015.

- ↑ a b Interview: Ijoma Mangold and Adam Soboczynski: Population development: What to do with young men? In: Interview with Gunnar Heinsohn. Time online, November 21, 2015, accessed November 21, 2015 .

- ↑ Why a two-state solution doesn't guarantee peace in the Middle East , in: Washington Examiner, February 17, 2017.

- ↑ In detail in Gunnar Heinsohn: Social War Theories: Demographic Factors , in: Thomas Jäger, Rasmus Beckmann (Ed.): Handbuch Kriegstheorien , VS Verlag / Springer Fachmedien, Wiesbaden 2011, pp. 72–95.

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn: Demographic framework conditions of European security , in: J. Frank, W. Matyas (ed.): Strategy and Security 2014: Europe’s Security Culture in Transition , Böhlau, Vienna a. a. 2014, pp. 205-218. In essay form, Heinsohn and Gavrilo Princip's brothers expressed himself in: Swiss Month No. 1019, September 2014.

- ↑ The consequences of global migration , in: Cicero , October 28, 2016.

- ↑ Mohssen Massarrat: The mothers are to blame for wars , in: Frankfurter Rundschau , January 31, 2007.

- ↑ Most recently Gunnar Heinsohn: Archaeological strata versus Baillie's tree-rings: proposal for an experiment (PDF) , September 2014.

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn: Withdrawal of support for Velikovsky's date of the Amarna period , in: Bulletin of the Society for the Reconstruction of Human and Natural History 3, 4 (1987) 13-18.

- ↑ Uwe Finkbeiner, Von Zeugenbergen and Geisterschichten, in: H. Kühne et al. Vanishing point Uruk. Archaeological unit from methodological diversity, Fs Nissen, Leidorf 1999, ISBN 3-89646-386-1 , pp. 125–31

- ^ Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean .

- ↑ Dietz Otto Edzard: Kaldu (Chaldäer) , in: Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Aräologie , Vol. 5, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1980, pp. 293-296, here: pp. 293, 291, 294.

- ↑ Jules Oppert: Études Sumériennes (Premier Article) , in: Journal Asiatique 5 (1875), p. 551.

- ↑ Jules Oppert: Études Sumériennes , in Journal Asiatique 5 (1875), p. 277.

- ^ Anton Deimel : Sumerian-Akkadian Glossary , Pontificii Instituti Biblici, Rome 1934, p. 141.

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn: The Sumerians did not exist , 1988, second edition: Mantis, Graefelfing 2007; ders .: Empires Lost and Found: Stratigraphy and the Search for the Great Powers of the Past , in: The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies, May 2006.

- ^ MP Streck (ed.): Reallexikon der Assyriologie, Volume 13, ISBN 978-3-11-030715-3 , pp. 290-300

- ^ History of Mesopotamia. From the Sumerians to Alexander the Great, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-51664-5

- ↑ MP Streck (ed.): Reallexikon der Assyriologie, Volume 13, ISBN 978-3-11-030715-3 , pp. 290-94

- ↑ Robert Rollinger : The phantom of the Medischen 'Großreichs' and the Behistun inscription , in: Edward Dabrowa (Ed.): Ancient Iran and its Neighbors. Studies in Honor of Prof. Józef Wolski on Occasion of his 95th Birthday , Jagiellonian University Press, Krakau 2005, p. 1/3.

- ^ In addition, AK Grayson: Mitanni , in: Arthur Cotterell (Ed.): The Penguin Encyclopedia of Ancient Civilizations , London 1980, p. 109.

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn: Cyaxares: Media's Great King in Egypt, Assyria and Iran , in: The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies June of 2006.

- ^ First Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg: The Quest for an Elusive Empire , in: Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg, A. Kuhrt (ed.): Achaemenid History IV. Center and Periphery , Brill, Leiden 1990.

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn: Assyrian kings equal to Persian rulers! The Assyria finds confirm the Achaemenid Empire , Mantis, Graefelfing 1996.

- ^ Heinsohn's Ancient "History" ( Memento from September 25, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), in: Aeon 5,4 (1999) 57-74 (PDF).

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn: Who ruled in the Indus Valley? , Mantis, Graefelfing 1997.

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn: Who Were the Hyksos? Can Archeology and Stratigraphy Provide a Solution to the 'Enigma of World History?' , in: S. Curto, S. Donadoni, AM Donadoni Roveri, B. Alberton (Eds.): Sesto Congresso Internazionale di Egittologia. Atti. , Vol. II, Turin, 1993, pp. 207-219 ( online ).

- ^ Already Gunnar Heinsohn, Heribert Illig: When did the pharaohs live? Archaeological and technological foundations for rewriting the history of Egypt and the rest of the world , Mantis, Graefelfing 1990, sixth edition 2010, pp. 266 ff., 352 ff.

- ↑ About Israel Finkelstein , Neil A. Silberman : David and Solomon: Archaeologists decipher a myth. Beck, Munich 2006.

- ^ Israel Finkelstein, Neil A. Silberman: David and Solomon: Archaeologists decipher a myth. Beck, Munich 2006, p. 45.

- ↑ About Eilat Mazar : Did I Find King David's Palace? , in: Biblical Archeology Review 32.1 (2006) 16-27, 70.

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn: Does Asia's 300 to 600 chronological gap apply to the whole earth? , in: Zeitensprünge 23,1 (2011) 164–193.

- ↑ Lecture Heinsohn: How did so many 1st-3rd century Roman elements make it into the 8th-10th century Viking Age? during the First International Conference on Truso. Viking Globalization: Truso from the perspective of Baltic commercial centers, Elbląg, The Old Town Hall, 18th - 19th May 2015 .

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn: Charlemagne's correct place in history , on: q-mag.org, April 2014.

- ↑ On the archeology of the imperial palace Ingelheim cf. Palatinate of the Carolingians , at: kaiserpfalz-ingelheim.de .

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn: Rome's imperial stratigraphy belongs to the 8th-10th century period , on: q-mag.org, June 2014.

- ↑ digitized version

- ^ Art. Opus de Emendatione Tempore , Encyclopedia Britannica .

- ↑ Andrea Riggio: E se il mondo fosse più giovane di qualche secolo? , in: Storia in Rete (Oct.-Dec. 2016) 66-71.

- ↑ Review by Ulrich Busch .

- ^ William J. Luther: Book Review: G. Heinsohn and O. Steiger's' Ownership Economics: On the Foundations of Interest, Money, Markets, Business Cycles and Economic Development, F. Decker (Ed) (October 9, 2013) ( review ), doi : 10.2139 / ssrn.2338198 .

- ^ Liberty Award New Direction for Achievements in liberal democracy and market economics .

- ↑ New Direction presents the Liberty Award to Gunnar Heinsohn for excellent work in furthering Polish-German relations , EU Agenda, undated and Prof. Heinsohn laureatem Nagrody Wolności , Pomorza Czas, June 21, 2016.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Heinsohn, Gunnar |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German sociologist, economist and civilization theorist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 21, 1943 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Gotenhafen |