Luxembourgish language

| Luxembourgish (Lëtzebuergesch) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

Luxembourg | |

| speaker | 390,000 | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Official status | ||

| Official language in |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

lb |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

ltz |

|

| ISO 639-3 | ||

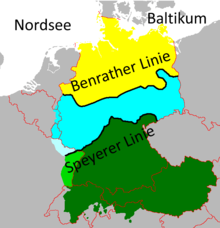

The Luxembourgish language or Luxembourgish for short [luksemburgɪʃ] (own name Lëtzebuergesch [ lətsə'buʁgiʃ ]) is the national language and one of the official languages of Luxembourg . It is a Moselle Franconian language variety of West Central German and part of the German or continental-West Germanic dialect continuum . Linguistically, Luxembourgish is a standard German dialect (see diagram). In the European Union , Luxembourgish is a minority language, but it is notOfficial language of the Union . The language code according to ISO 639 is lb or ltz . Luxembourgish is the subject of research in Luxembourg studies .

status

Luxembourgish was only made the national language in 1984 and since then has been the third official language in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg alongside French and German (written High German) . The first official spelling of Luxembourgish was introduced in 1946, but did not catch on. The current school orthography from 1976 was reformed in 1999 and again in 2019. Nevertheless, Luxembourgish is mostly only taught orally and is used less as a written school language (see diglossia ). In radio and television is Luxembourgish, the most widely used language form, less in the print media . In the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, 65% of all articles are published in (standard) German, 25% in French and only 10% in Luxembourgish. Since there are only a few television programs in Luxembourgish, most of the Luxembourgers watch programs in German or French. To this day, legal texts have not been drafted or published in Luxembourgish, only the chamber reports are partly written in this language. Luxembourgish is also not one of the official languages of the European Union .

In 2018, the center fir d'Lëtzebuerger Sprooch was established by law . Its task is to standardize and promote Luxembourgish.

Structural linguistic aspect

Luxembourgish Moselle Franconian forms a dialect continuum together with the neighboring Moselle Franconian varieties in the northern Saarland and in the Trier region , with which it partly corresponds in grammar , vocabulary , word usage and sound level . From a structural linguistic point of view, however, it does not differ fundamentally from the other West Central German varieties. Therefore it is not a language in the sense of a distance language .

Sociolinguistic aspect

In the sociolinguistic field, Luxembourgish differs somewhat from the Moselle-Franconian varieties spoken in the neighboring language areas in Germany:

- Luxembourgish is an important part of the Luxembourgish identity . A Luxembourg child learns it as their mother tongue before later learning written German, French and English at school. Nevertheless, in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, even after the French-speaking part of Luxembourg became part of Belgium, all laws were drafted and published in German and French until the end of 1944; since 1945 this has only been done in French. For many Luxembourgers, Luxembourgish has meanwhile become a symbol of the cultural and political independence of their state. This aspect is directly related to the history of Luxembourg (see below).

- Since Luxembourgish has been used increasingly as a written language in the Grand Duchy for several decades, the next development step would be the transition to an independent extended language .

Problem

The position of Luxembourgish as a Central German language variety and as an official language in an independent state sometimes triggers a dispute among linguists and laypeople as to whether it is a standard language (comparable to High German and Dutch standard language) or just a High German language variety. It is stated that Luxembourgish is more closely related to Standard German than many Upper German varieties (e.g. Alemannic - including Swiss German - or Bavarian ), which are not regarded as independent languages.

From a purely linguistic point of view, the question of whether Luxembourgish is an independent language cannot be answered clearly. In the case of closely related language varieties, there are no structural linguistic criteria that would allow a distinction between dialects and languages . The answer to this question therefore depends largely on the importance attached to sociolinguistic criteria.

For this reason, this distinction is used repeatedly and abusively politically, for example to legitimize alleged hierarchies between regional language varieties in a pseudo-scientific manner. Certain terms, such as cultural dialect, are the result of this contradiction between linguistics and politics.

Luxembourgish is considered a European minority language , but is not one of the 24 official languages of the European Union .

Geographical distribution

Luxembourgish is spoken in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg , as well as in the neighboring areas of Germany (in the southwest of the Eifel around Bitburg and in the Moselle valley around Trier ), Belgium (in the Arlon area in the province of Luxembourg and in the Burg-Reuland and Sankt Vith area in the south of the German-speaking Community Belgium ), France (parts of Lorraine ) and in the western parts of the Saarland . There is a continuous transition to the other Moselle-Franconian dialects towards the east . In the Federal Republic of Germany and the German-speaking community of Belgium, however, Luxembourgish is only regarded as a dialect of the German language .

There are different local Luxembourgish dialects: Areler , Eechternoocher , Kliärrwer , Miseler, Veiner , Weelzer etc. A cartographic overview of their distribution can be found in the Digital Luxembourg Language Atlas.

Around 300,000 people worldwide speak Luxembourgish as their mother tongue ; 250,000 of them live in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, the rest in the Belgian provinces of Luxembourg and Liège (Burg-Reuland and St. Vith), in Germany , in France and in the USA . The dialects of the Transylvanian Saxons , whose ancestors emigrated from the Moselle-Franconian area over 800 years ago , are also closely related .

Written language

Uniform and binding spelling was introduced by decree in November 1976 and reformed in 1999.

The Law on the Use of Languages of February 24, 1984 stipulates (note that the original text is in French):

Article 1: The national language of Luxembourgers is Luxembourgish.

Article 2: Legal texts and their implementing provisions are written in French.

Article 3: Administrative and legal languages: French, German or Luxembourgish can be used.

Article 4: Administrative inquiries: If an inquiry is written in Luxembourgish, French or German, the administration must, if possible, use the language of the questioner in its response.

The Latin alphabet is used for written Luxembourgish, supplemented by the letters ä, ë and é; ö and ü occur almost exclusively in words that have been adopted unchanged from written German. Some words were also taken over unchanged from the French language.

Between 2000 and 2002, the Luxembourg linguist Jérôme Lulling developed a database with 125,000 word forms for the first Luxembourg spell checker (CORTINA project).

orthography

The Luxembourg language has the umlauts ä (IPA: / æ / ), u (IPA: / y / ), ë (IPA: / ɘ / ) (formerly ö , IPA: / œ / ) and é (IPA: strong / e / ). The ë , which is characteristic of the Luxembourgish language, replaces the ö ( delabialization ), which was previously widely used ; it is circumscribed as eo (instead of oe ). The é , which comes from French, is always tense , in contrast to the German e . Just like in Swiss Standard German, there is no ß in Luxembourgish ; This is like there by a double-s ( ss , IPA: / s / ) replaced.

Vowels are pronounced long when written twice. All vowels are doubled. So the i [i] in the doubling does not become ie, as in German, but rather ii [ iː ]

phonetics

Consonants

The IPA symbol is in brackets.

| bilabial | labio-dental | dental | alveolar | post-alveolar | retroflex | palatal | velar | uvular | pha-ryngal | glottal | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | |

| Plosives | p

[ p ] |

b

[ b ] |

t [ t ] | d

[ d ] |

k

[ k ] |

G

[ g ] |

ʔ | |||||||||||||||

| Nasals | m

[ m ] |

n

[ n ] |

ng

[ ŋ ] |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Vibrants | r

[ ʀ ] |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Taps / flaps | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fricatives | f [ f ] | w

[ v ] |

s

[ s ] |

s

[ z ] |

sch

[ ʃ ] |

sch [ ʒ ] | ɕ | ʑ | ch

[ χ ] |

r

[ ʁ ] |

H

[ h ] |

|||||||||||

| lateral fricatives | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Approximants | j [ j ] | w

[ w ] |

||||||||||||||||||||

| lateral approximants | l [ l ] | |||||||||||||||||||||

Pronunciation options for the g

| Phonemes | Allophones | Occurrence | requirement | example | IPA | translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| / ɡ / | [k] | French and

German words |

At the end of the word | Drug | [dʀoːk] | drug |

| [G] | Luxembourgish and

German words |

At the beginning of the word stem | géi | [ɡəɪ̯] | go | |

| some German words | In the root word | Drugs | [ˈDʀoːɡən] | Drugs | ||

| French words | At the beginning or in the root of an a, o, u or

of a consonant |

Negative | [neɡɑˈsjəʊ̯n] | negation | ||

| / ʃ / | [ʃ] | French words | At the end of a word before a mute e | Plague | [plaːʃ] | Beach |

| / ʒ / | [ʒ] | At the beginning and in the stem before e , i or y | original | [oʀiʒiˈnæl] | original | |

| / χ / | [χ] | Luxembourgish and

German words |

At the end of the word after the front vowels | Dag | [daːχ] | Day |

| [ɕ] | At the end of the word after non-front vowels

and consonants |

bëlleg | [ˈBələɕ] | cheap | ||

| / ʁ / | [ʁ] | In the root of the word after anterior vowels | camp | [ˈLaːʁɐ] | camp | |

| [ʑ] | In the root of the word after non-front vowels

and consonants |

Available | [fɐˈfyːʑuŋ] | Available | ||

| [ j ] | In the unstressed position / eʁe / ( [əjə] ) and / eʁɐ / ( [əjɐ] ) | lay down | [ˈBələjən] | cheap

(bent) |

Vowels

| front | central | back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ung. | ger. | ung. | ger. | ung. | ger. | |

| closed | i [ i ] | ü [ y ] | [ u ] | |||

| almost closed | ||||||

| half closed | é [ e ] | ö [ ø ] | o [ o ] | |||

| medium | ë [ ə ] | |||||

| half open | e [ ɛ ] | ö

[ œ ] |

||||

| almost open | Ä

[ æ ] |

he [ ɐ ] | ||||

| open | aa

[ a ] |

a [ ɑ ] | ||||

[œ], [ø] and [y] occur only in German and French loanwords .

The e embodies [æ] and [ə].

Double vowels are pronounced long.

Diphthongs

| IPA | Notation | German equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| [iə] | ie | ie |

| [ɜɪ] | egg | äi, äj |

| [æɪ] | ai | äi, äj |

| [ɑɪ] | egg | egg |

| [uə] | ue | ue |

| [əʊ] | ou | oa (o as in open) |

| [æʊ] | ouch | uh |

| [ɑʊ] | ouch | ouch |

- The endpoints of the closing diphthongs are closer together, more like [i, u] than like [ɪ, ʊ].

- The starting points of / əɪ̯, əʊ̯ / are typically black-like [ə], but the first element of / əɪ̯ / can be more of a central front vowel [ë̞].

- The starting points of / æːɪ̯, æːʊ̯ /, / ɑɪ̯, ɑʊ̯ / and / iə̯ / and / uə̯ / are similar to the corresponding short monophthongs [æ, ɑ, i, u].

- The first elements of / æːɪ̯, æːʊ̯ / can be phonetically short in quick language or in unstressed syllables [æ].

- The centering diphthongs end in the central unrounded area [ə].

- / oɪ̯ / appears only in loan words from standard German.

- The contrasts / æːɪ̯ - ɑɪ̯ / and / æːʊ̯ - ɑʊ̯ / resulted from an earlier lexical tone contrast: the shorter / ɑɪ̯, ɑʊ̯ / were used in words with accent 1, while the lengthened / æːɪ̯, æːʊ̯ / were used in words with accent two.

- Additional phonetic diphthongs are created after the vocalization of / ʀ /. These are [iːə̯, uːə̯, oːə̯, ɛːə̯] with [iːɐ̯, uːɐ̯, oːɐ̯, ɛːɐ̯] as possible alternatives. The sequence / aːʀ / is realized just like long / aː /, unless a vowel follows within the same word.

- Loan words from standard German (such as Bad Dürkheim and Föhr) also contain [yːə̯] and [øːə̯], again with [yːɐ̯] and [øːɐ̯] as possible alternatives.

morphology

Nouns and pronouns

The grammatical case is defined in Luxembourgish as in Standard German by the article den , demonstrative and possessive pronouns , e.g. B. mäin (German: my), dësen (German: this), keen (German: none) and attributes are displayed. In Luxembourgish there are still three cases of nouns and adjectives: the accusative , which has taken over the function of the nominative , the dative and, in some expressions, the genitive . Only petrified noun phrases remain of the nominative, for example Däiwel (German: to the devil) or eiser Härgott (German: our Lord God).

Since the genitive is not pronounced, the possessive sentence construction is formed with the dative, which is often paraphrased in German with " genitive paraphrase " and in English with periphrastic genitive . Rare exceptions are idioms like:

- Ufanks of the week (German: beginning of the week)

- Enn des Mounts (German: end of the month)

A peculiarity of Luxembourgish is the frequent addition of -s , -sen or -schen to the family name in front of the first name, creating a genitive case. This form is also used in German, but in an upscale way of expression.

In the case of the singular and plural, the singular is unmarked, that is, there is only one plural ending, but no singular ending. In the plural, no distinction is made between the sexes.

| Nominative | accusative | dative | |

| 1 singular | eh | mech | me (mer) |

| 2 singular | you (de) | dech | you (the) |

| 3 singular masculine | hien (en) | him (em) | |

| 3 singular neuter | hatt (et) | ||

| 3 singular feminine | si (se) | hir (he) | |

| 1 plural | me (mer) | ais / ice | |

| 2 plural | you (the) | iech | |

| 3 plural | si (se) | down (en) | |

There are three grammatical genders (genera) in Luxembourgish : male (deen, short: den) , female (déi, short: d ') and neuter (dat, short: d') . The grammatical gender in Luxembourgish is the same as that in the respective standard language from which it was adopted. Examples : d ' Gare (fr. La gare, dt. The train station), d' Bréck (fr. Le pont, dt. The bridge). As in other languages, gender does not always coincide with sex . As in German, words that end in e in German often have the female gender, such as: d'Kaz (German: the cat), d'Bei (German: the bee), d'Blumm (German: the flower ).

As in various other German dialects, the number word "Zwei" also differs in Luxembourgish depending on the gender of the following noun, e.g. B. zwee men (two men [ mask. ]), But zwou Fraen (two women [fem.]).

Nominative accusative

| Singular | Plural | ||||

| male | neutrally | Female | |||

| certainly | the | d ' | |||

| definitely stressed | deen | dat | déi | ||

| Demonstrative pronouns | den | dëst | of | ||

| indefinite article | en | closely | - | ||

| negation | keen | keng | |||

| Possessive pronouns masculine / neuter | säin | scorching | |||

| Possessive pronouns feminine / plural | hiren | here | hir | ||

dative

| Singular | Plural | |||

| male | neutrally | Female | ||

| certainly | the | of the | the | |

| definitely stressed | deem | because he | deenen | |

| Demonstrative pronouns | dësem | this | den | |

| indefinite article | tight | tighter | - | |

| negation | narrow | kenger | kengen | |

| Possessive pronouns masculine / neuter | scorching | senger | scorch | |

| Possessive pronouns feminine / plural | hirem | hirer | hiren | |

Adjectives

There are attributive and predicative adjectives in Luxembourgish .

The comparative in Luxembourgish is mostly analytical , that is, unlike in German, the adjective itself usually remains unchanged and is only supplemented by “méi” (German: more). As in German, however, the superlative is formed by the ending "-sten". Exceptions are a few irregular adjectives such as

- good, better, am beschten (German: good, better, best)

- vill, méi, am meeschten (German much, more, most)

- wéineg, manner, am mannsten (German: little, less (less), least (at least))

or expressions like:

- eng eeler lady (German: an elderly lady)

- eng gréisser company (German: a larger company)

Verbs

As in German, there are also three verb categories in Luxembourgish. Weak verbs do not change their verb stem. Strong verbs can change their verb stem in the present, past and simple subjunctive. Regular verbs end in -en . Some end in -éieren . These are absolutely regular (i.e. show no changes) and mostly come from French verbs.

auxiliary verbs

There are four auxiliary verbs in Luxembourgish. They are needed for the formation of times and the diathesis . They are hunn (have) , sinn (be) , wäerten (will) , ginn (will) . Wäerten is used for the formation of the future tense , while ginn is used for the construction of the passive and the compound subjunctive.

| indicative | indicative | Easier | imperative | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1 | hun | Has | would have | |

| 2 | hues | has | hate | called! | |

| 3 | hat | Has | would have | ||

| Plural | 1 | hunn | had | would have | |

| 2 | hutt | Has | would have | hoves! | |

| 3 | hunn | had | would have |

The past participle is gehat .

| indicative | indicative | Easier | imperative | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1 | sense | was | wier | |

| 2 | bass | waars | wiers | sief | |

| 3 | ass | was | wier | ||

| Plural | 1 | sense | were | waving | |

| 2 | sidd | wait | wiert | sieft | |

| 3 | sense | were | waving |

The past participle reads pointed .

| indicative | ||

|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1 | wäert |

| 2 | wäerts | |

| 3 | wäert | |

| Plural | 1 | evaluate |

| 2 | wäert | |

| 3 | evaluate |

The auxiliary verb wäerten only exists in the present.

| indicative | indicative | Easier | imperative | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1 | start | gouf | géif | |

| 2 | gëss | goufs | géifs | gëff | |

| 3 | god | gouf | géif | ||

| Plural | 1 | start | goufen | whistle | |

| 2 | gitt | gouft | poisoned | gitt | |

| 3 | start | goufen | whistle |

The past participle is ginn .

Regular verbs

| indicative | indicative | Composer | imperative | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1 | alaméier en | hun alamért | Alamégéif | |

| 2 | alaméier s | hues alamért | Alamé géifs | alaméier! | |

| 3 | alaméier t | huet alamért | Alamégéif | ||

| Plural | 1 | alaméier en | hunn alamért | alerting | |

| 2 | alaméier t | hutt alamért | poison alarm | alarmed! | |

| 3 | alaméier en | hunn alamért | alerting |

The perfect tense is formed with the help of the verbs sinn (to be) and hunn (to have) in the present tense. The past perfect is also formed like this, but the auxiliary verb is in the simple past. The present subjunctive is with the auxiliary beginning (are) formed in the simple subjunctive (Similar to the Germans would ). The subjunctive perfect is formed with the auxiliary verb hunn , which is in the subjunctive. The future tense is formed with the verb wäerten (to be) . Sometimes the participle corresponds to the infinitive , sometimes a -ge is added to the verb.

There are still about 30 words that form a past tense and a simple subjunctive by changing the vowel and inserting a -t- . All auxiliary verbs (except wäerten ) and all modal verbs form a past tense and a subjunctive. Many verb forms that develop a past tense or a subjunctive are still used only rarely or not at all (see German backen -> buk or backte ).

modal verbs

As in German, there are also modal verbs in Luxembourg. They are däerfen (may) , kënnen (can) , must / miss (must) , net need (do not need, do not have to) , should (should), guess (as in the German colloquial language "he will have already done that") , wëllen (want) .

| indicative | Easier | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1 | need net | needn't |

| 2 | need net | need | |

| 3 | need net | needs | |

| Plural | 1 | need net | need net |

| 2 | needs net | needn't | |

| 3 | need net | need net |

| indicative | indicative | Easier | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1 | däerf | may | dierft |

| 2 | daerfs | may | dierfts | |

| 3 | däerf | may | dierft | |

| Plural | 1 | allowed | allowed | were allowed |

| 2 | daerft | may | dierft | |

| 3 | allowed | allowed | were allowed |

| indicative | indicative | Easier | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1 | can | can | knows |

| 2 | can | could | can | |

| 3 | can | can | knows | |

| Plural | 1 | know | could | could |

| 2 | knows | can | knows | |

| 3 | know | could | could |

| indicative | indicative | Easier | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1 | got to | have to | measures |

| 2 | got to | have to | measures | |

| 3 | got to | have to | measures | |

| Plural | 1 | to miss | had to | measured |

| 2 | have to | have to | measures | |

| 3 | to miss | had to | measured |

| indicative | indicative | Easier | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1 | should | should | should |

| 2 | shall it | ought to | ought to | |

| 3 | should | should | should | |

| Plural | 1 | should | should | should |

| 2 | should | should | should | |

| 3 | should | should | should |

| indicative | indicative | Easier | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1 | wëll | want | wéilt |

| 2 | wëlls | want it | wéilts | |

| 3 | wëll (t) | want | wéilt | |

| Plural | 1 | waves | wanted to | wéilten |

| 2 | wells | want | wéilt | |

| 3 | waves | wanted to | wéilten |

Wäerten is conjugated like the auxiliary verb .

syntax

As in German, the sentence structure ( syntax ) is characterized by the second position of the verb: Ech spille Foussball. At the summer, ech Foussball play. Gëschter hunn ech football spilled. Wéini spills you foussball? In the subordinate clause, the basic sentence order is SOV: De Mëtteg spillen ech Foussball, when et nom Iessen net méi reent.

vocabulary

Most Luxembourgish words are related to German. These words can often be found in a slightly different form in High German.

However, there are also words that do not exist in standard German but occur in other German dialects, such as B. Gromperen (potatoes).

Meanwhile, numerous words can only be found in Luxembourgish, such as B. 'squint' barely . Luxembourgish also has a very large number of idioms that cannot be found in other languages.

Finally, there are a few words that show a relationship with Dutch (e.g. Geck (Dutch: gek ) 'crazy, fool'; de Geck maachen (Dutch: gek doen ), joking, silly '). The phrase when ech lifted 'please' is remarkable .

Luxembourgish has always been shaped by strong French influences:

French influences

Although Luxembourgish is generally referred to as the Moselle-Franconian dialect, it differs considerably from the latter dialects in one respect. Over time, a large number of French words have been integrated into Luxembourgish, even basic words such as merci (thank you) or pardon (excuse) are of French origin. These influences have certainly increased considerably after Luxembourg was incorporated into Napoleon's empire and continue to this day, more than 150 years after gaining independence. Many words that have only emerged in the last 200 years are therefore of French origin.

E.g. Camion = truck / washbasin = sink / Frigo = refrigerator / Gare = train station etc.

There are two types of French-born expressions:

Those who have already naturalized:

- E.g. fëmmen = fumer = smoking / Forchette = fourchette = fork / Fotell = fauteuil = armchair / Lastique = élastique = rubber band / peck = piquer = prick, itch / prett = prêt = ready / suen = sous = money / tirrang = tiroir = Drawer / vacancy = vacances = vacation etc.

Those that come unchanged from French, but which are often stressed differently than in French:

- E.g. Accident = Accident / Cadeau = Gift / Enveloppe = Envelope / Ice cream = Ice cream / Goût = Flavor / Juice = Juice / mauve = purple / Pneu = Car tire / Chicken = Chicken / Rideau = Curtain / Valise = suitcase etc.

Furthermore, there are compound words that consist of a German and a French word. There are also a few that are formed from two words of French origin. However, all of these compound words have a German construction.

Example German - French:

- Haaptplat (main course): haapt = main / plat = dish

- Soccer terrain (soccer field): Soccer = soccer / Terrain = playing field

- Bréifboîte (letter box): Bréif = letter / Boîte = box

Example French - French

- Veloscourse (bike race): Velo = bike / course = race

- Coursevelo (racing bike)

- Comitésmember (board member): Comité = board member (French membre ) = member

Neologisms

The latest neologisms come from English from the fields of modern telecommunications and computer technology. Jérôme Lulling analyzed these neologisms in his dissertation in 2002 and examined them for mutation and semantics. He documented how the Internet through chat rooms and e-mails and mobile telephony through SMS strongly shaped Luxembourgish.

Use of Luxembourgish

The mother tongue and therefore the colloquial language of Luxembourgers is Luxembourgish. The place names are also written in Luxembourgish on the place name signs (as the second piece of information next to the French form). Family and popular documents such as invitations and leaflets are mostly in Luxembourgish, while official notices are mostly in French. The dynamic warning signs on the motorways are labeled in German (from motorways from Germany) or in French (from motorways from the French-speaking part of Belgium and France). The majority of Luxembourgish young people use the Luxembourgish language to write short messages (SMS), e-mails, etc. Local vendors in traditional shops speak Luxembourgish.

School lessons in the primary level (1st to 6th school year) are traditionally in Luxembourgish and Standard German . Literacy in Luxembourg is in standard German. French is taught from the 2nd school year, now in some schools even from the 1st school year. With the exception of the books for French, the school books are traditionally written in German. The language of instruction is therefore, strictly speaking, Standard German. In practice, however, the teaching staff often uses Luxembourgish to explain the subject matter orally.

In the secondary level (7th to 13th school year) this practice is continued up to the 9th grade. The language of instruction - with the exception of language and mathematics lessons - is High German or Luxembourgish. In the classical lyceum, the language of instruction is mostly French from the 10th grade onwards; in the technical lyceum, standard German remains the predominant language of instruction. In a curriculum established by the Ministry of Education ( Ministère de l'Éducation nationale et de la Formation professionnelle , MEN for short), each subject is assigned a language of instruction. These also change from level to level (classic lyceum or technical lyceum). In secondary education, Luxembourgish would be used less in class than in primary school, although this depends on the school and the teachers. Luxembourgish as a subject is on the curriculum up to the 7th school year; In the following years, this is often used to clarify individual issues.

In Parliament has until the Second World War, High German and French spoken. After the war, the native Luxembourgish took the place of High German. Today French is used by MPs, u. a. because of the livestream transmission via the Astra satellite, only rarely used; only for example when quoting legal texts or for protocol reasons.

Due to the small, specifically Luxembourgish vocabulary, speakers often resort to German or French loanwords when using different languages . This fact is often cited as a criterion for the “non-linguistic character” of Luxembourgish; but it is a matter of a natural readiness for adaptation which is characteristic of all languages (cf. the high number of Latin, Greek, French and English elements in German, which are documented for all epochs of linguistic history).

Fiction exists in (standard) German, Luxembourgish and French.

Luxembourgish is also making its way into everyday public life. A few decades ago, for example, the announcements in the Luxembourg City train station were changed from French – German to Luxembourgish – French (also on the trains); German is only used as the third announcement language on trains to and from Germany.

history

For Luxembourgers, Lëtzebuergesch is one of their strongest national symbols. The language is inextricably linked with the fate of Luxembourg, although a national consciousness did not emerge until late, i. H. developed only from the 20th century. This has to do with the history of the country on the one hand, and the current situation in Luxembourg on the other.

The last division of Luxembourg

During the Revolutionary Wars, Luxembourg fell again to France in 1794/95. After Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo (June 1815), the future fate of the country was decided at the Congress of Vienna . While the other areas of the former Austrian Netherlands as well as the Principality of Liège , parts of the Duchy of Bouillon and the Principality of Stablo-Malmedy (→ future Belgium ) were united with the northern Netherlands to form the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, the Luxembourg area became a new state with the Designation Grand Duchy raised and henceforth ruled in personal union by the Dutch King Wilhelm I. In addition, this Grand Duchy was integrated into the German Confederation so that Prussia could exercise garrison law in the fortress city of Luxembourg . At the Congress of Vienna, the Bitburger Land, which had previously belonged to Luxembourg rule (essentially the Bitburg district as it existed until 1970), was separated and incorporated into the newly founded Prussian Rhine Province.

In 1830, most of the Luxembourgers took part in the Belgian Revolution against the arbitrary rule of the Dutch king. At that time, the country comprised what is now Luxembourg and what is now the Belgian " Province de Luxembourg ". The majority of the population wanted to belong to the newly created, liberal Kingdom of Belgium. The Dutch king, however, asserted his property claims in Luxembourg, so that after years of struggle and international negotiations with the conclusion of the London Conference (1838-1839), the Romance (French-speaking) western half was ceded to Belgium and the rest in personal union with the Netherlands as well remained in the German Confederation. In principle, the division was supposed to run along the German-French language border, which meant that the Luxembourg region was rid of its bilingualism.

A special case was the Areler Land , which, despite its German- or Luxembourgish-speaking population, was annexed to Belgium because France insisted during the negotiations that the strategically important road from Longwy (F) via Arlon and Bastnach to Liège or Brussels to " neutral “Belgian state and not to the rest of the Grand Duchy, which still belonged to the German Confederation (until 1866). Apart from that, Arlon had been the "provisional capital" of the province of Luxembourg from 1830 to 1839, as the Prussian military ensured that the city-Luxembourgers remained loyal to their Grand Duke Wilhelm I in the capital of the Grand Duchy.

- Literature: Edouard M. Kayser , Somewhere between Vienna and London… - The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg from 1815 to 1867. Verlag St. Paulus, Luxembourg 1990 (translated from French).

Only now could Luxembourgish develop into a national symbol, as it now encompassed the whole country.

However, a national consciousness emerged rather hesitantly. Luxembourgish-German was the language of the people at this time. By the end of the 19th century there were also some MPs who campaigned for a merger with Belgium. Without this division, the Luxembourg dialect might have been displaced in favor of French, as the majority of the West Luxembourg population had Romance dialects or French as their mother tongue.

1848 to 1918

In the country's first constitution (1848), Luxembourgish was not mentioned; there was freedom of choice between German and French for official language use. In December 1896, the Chamber of Deputies rejected a proposal by C. M. Spoo to recognize Luxembourgish as an independent language.

It was only with the discovery of iron ore and the industrialization of the south that steel companies emerged, which helped the state to prosper for the first time. This upswing boosted the pride of the population and they began to feel like a nation in their own right. The occupation by German troops in World War I (1914–1918) reinforced this feeling again and finally created the desire for national independence.

The second World War

Until the Second World War , Lëtzebuergesch was the mother tongue and colloquial language of the Luxembourgers. This changed during the occupation in World War II, when the Gauleiter Gustav Simon tried, on behalf of Hitler , to voluntarily integrate the Luxembourgers into the German Reich as "part of the German national body" . For this purpose, all French words and designations were Germanized in order to reduce the influence of French language and culture. The use of the Lëtzebuergeschen was not prohibited, but all public rallies, letters and documents had to be written in the High German official language, and only the High German official language was taught in schools. French first and last names were Germanized ( e.g. the name Louis became Ludwig, etc. ). These measures led to discontent among the population, but only with the native language Lëtzebuergesch could one express one's aversion to the occupation regime.

In a civil status survey on October 10, 1941, Luxembourgers were asked about their nationality , their mother tongue ("Dialects (dialects), e.g. Luxembourgish, Low German, are not considered a mother tongue") and ethnicity . The result of this survey was intended to make their German origins clear to the Luxembourgers in order to better integrate them into the German Empire . However, random checks showed that the result did not correspond to the expectations of the occupiers, so the referendum was canceled and the apparent resistance of the population strengthened.

Post-war until today

The experiences of the Second World War, and in particular the compulsive “Germanization” of all French in Luxembourg, encouraged the increased acceptance of French expressions in the Luxembourgish language and established the Lëtzebuergesche as a national symbol of the Luxembourgers. An attempt made after the liberation of 1944 to spellually decouple Luxembourgish from the official German language by introducing a phonetic spelling Luxembourgeoise Officielle (OLO) and thus to make it an independent national language outwardly, failed. Insofar as Luxembourgish was used as the written language in books and periodicals, the traditional spelling variants used in the 19th and early 20th centuries, mainly for lyrical and epic literature, were used, which more or less closely follow the as Written language based on familiar standard German. The Luxembourg government took this tendency into account by giving up the unpopular OLO in 1976 and introducing a Luxembourg school orthography that was again based more closely on High German writing conventions, including "typical" German language characteristics such as upper and lower case.

With the recruitment of Italian (around the turn of the century) and Portuguese (1960s) citizens as migrant workers , the emergence of the banking system and the policy of cross-border commuters since the early 1990s, Luxembourg increasingly became a country of immigration and a multiethnic society (around 39% of foreign origin ), in which many languages are spoken. In addition to Lëtzebuergesch, French in particular serves as the lingua franca for understanding between autochthons and migrants in Luxembourg.

In order to preserve the Luxembourg identity, Luxembourgers are becoming more and more aware of the cultural significance of their language. Luxembourgish is increasingly promoted by the state and in the mass media . The new media are contributing to the fact that young people are also increasingly writing in Luxembourgish (e.g. in text messages or in social networks). According to a study by Eurobarometer 2005, 73% of local Luxembourgers said they speak Luxembourgish as their mother tongue.

A Luxembourgish peculiarity is that in some shops in the country it is advertised that they also speak Luxembourgish, especially since in many shops almost exclusively cross-border commuters from Belgium and France work and they only communicate in their native French. Nevertheless, the Luxembourgers are still aware of the patriotic importance of their language during the occupation in World War II. The statehood of the Luxembourgers also means that they are reluctant to have their Luxembourgish language referred to as a German dialect ( cultural dialect ).

Press and media

The television and radio programs of RTL Lëtzebuerg, which can be received nationwide in Luxembourg, as well as the radio programs Radio ARA , DNR , radio 100.7 and Eldoradio broadcast in Luxembourgish and thus contribute to the standardization and further development of the language.

The press , e.g. For example, the daily newspapers Zeitung vum Lëtzebuerger Vollek , Luxemburger Wort , Tageblatt , Lëtzebuerger Journal , Lëtzebuerg Privat or Point 24 (German-French-Portuguese free newspaper) predominantly use German as a written language, but also contain articles in French (approx. 16%) and Luxembourgish (approx. 2%). The latter is particularly popular for comments and glosses, local news, family ads, and advertising; French is particularly common in the economic and cultural sections. The largest of these newspapers are sold in abundance, especially in the German states of Rhineland-Palatinate and Saarland. There are also four much smaller French-language newspapers, the weekly Le Jeudi and the daily newspapers La Voix du Luxembourg, Le Quotidien and L'Essentiel (free newspaper). Their primary target groups are migrants who have a good command of French as their mother tongue or foreign language, but who have little or no command of German or Luxembourgish, as well as readers in neighboring francophone countries. The RTL Lëtzebuerg news portal, on the other hand, is mostly in Luxembourgish . In the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, 85% of all articles in the print media are published in German, 12% in French and only 3% in Luxembourgish. After the liberation in 1944, the newspaper d'Unio'n published by the previous resistance movement ("Resistance") was temporarily published in Luxembourgish; In 1948, however, it ceased publication (the successor period that resulted from the merger of the Unio'n with the Obermosel-Zeitung is the predominantly German-language Lëtzebuerger Journal ). Since then, this attempt at a newspaper that is now completely edited in the national language has not yet been repeated, as the Luxembourg media have to fall back on foreign press services and the loss of time for translating an agency report into Luxembourgish and the associated costs make such an undertaking almost impossible.

Language examples

Universal Declaration of Human Rights , Article 1:

- All men can fräi a mat deer changed Dignitéit to the selwechte right op d'Welt. Jiddereen huet säi understanding a säi Gewësse krut an should act on a narrow Geescht vu Bridderlechkeet those other géintiwwer.

-

All people are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should meet one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Moien (Luxembourgish: "Hello") in the Justus Lipsius building during the European Presidency of Luxembourg

Moien (Luxembourgish: "Hello") in the Justus Lipsius building during the European Presidency of Luxembourg

| Luxembourgish | Standard German | French |

|---|---|---|

| moien | good morning Good Day | bonjour |

| äddi | goodbye | Adieu |

| when ech lifted | Sorry | s'il vous plaît |

| merci | thank you | merci |

| Lëtzebuerg | Luxembourg, Lützelburg | Luxembourg |

| jo | Yes | oui |

| nee (n) | No | non |

| dacks | often | souvent |

| perfect | clean | propre |

| Prabbli, Präbbeli | umbrella | parapluia |

| Forschett | fork | fourchette |

| He can | children | enfants |

| Strooss | Street | rue |

| Informatioun | information | information |

| Pabeier | paper | paper |

| Nanzeg | Nancy, Nanzig | Nancy |

| Parai | Paris | Paris |

| Bréissel | Brussels | Bruxelles |

Words that are important for linguistic classification and define the position of Luxembourgish in the Rhenish subject :

| Luxembourgish | Standard German | Location in the Rhenish Fan | north / south Word pair |

|---|---|---|---|

| eh | I | south of the Uerdinger line | ik / i |

| do | do | south of the Benrath line | maken / do |

| Duerf (south lux.) , Dooref (north lux.) | Village | south of the Bad Honnefer line | Dorp / village |

| tëschent (south lux.) , zwëschent (north lux.) | between | on the Linz line | tussen / between |

| op | on | north of the Bad Hönninger line | op / on |

| Kuerf | basket | north of the Boppard line | Korf / basket |

| dat | the | north of the St. Goarer line | dat / that |

| Apel | Apple | north of the Speyer line | Apple |

Standard German in Luxembourg

The standard German used in Luxembourg ("Luxemburger Hochdeutsch") differs in some concise terms from standard German in Germany; there are also differences in grammar. In Luxembourg High German, for example, there are the following terms:

| Luxembourgish Standard German | Standard German |

|---|---|

| amenaging (from French aménager ) | (comparable to) furnish, renovate |

| Manifestation (from French la manifestation ) | event |

| to organize something (from French organizer ) | do something |

| 24 on 24 ( 24 op 24 ) | Around the clock |

| 7 on 7 ( 7 op 7 ) | Every day |

| Round point | Roundabout |

| someones m call (see. lux. close uruffen ) | someones s call |

| Establish protocol | to file charges |

| three times nothing (from French trois fois rien and lux. dräi mol Näischt ) | nothing at all |

| (for certain place names :) on (the) place name (e.g. "on (the) Bridel") | in place name (e.g. "in Bridel") |

Further evidence for the written use of Standard German in Luxembourg can also be found in the German dictionary of variants . In particular, newspaper texts from the German-speaking press in Luxembourg and, in some cases, Luxembourg websites served as sources of evidence.

See also

literature

General descriptions and grammars

- Josy Braun et al. (in collaboration with Projet Moien!): Grammaire de la langue luxembourgeoise . Ministère de l'Éducation nationale et de la Formation professionnelle, Luxembourg 2005, ISBN 2-495-00025-8 .

- Robert Bruch: Foundation of a history of Luxembourgish , Luxembourg (Publications scientifiques et littéraires du Ministère de l'Éducation nationale) 1953, Volume I: The Luxembourgish in the West Franconian district. Luxembourg (Publications scientifiques et littéraires du Ministère de l'Éducation nationale) 1954, Volume II.

- Robert Bruch: Précis populaire de grammaire luxembourgeoise. Luxembourg grammar in popular outline (= contributions to Luxembourg linguistic and folklore, No. 10). 3e éd., Rev. by Léon Senninger. Section de linguistique de l'Institut Grand-Ducal, Luxembourg 1973.

- Germaine Goetzinger et al .: Lëtzebuergesch: a language goes its way: from “onst Däitsch” to “eis Sprooch”. [Exhibition] Center National de Literature, Maison Servais, Mersch, Luxembourg, October 2000 - March 2001. Center National de Literature, Mersch, Luxembourg 2000.

- Fernand Hoffmann : Languages in Luxembourg: Linguistic and literary-historical description of a triglossia situation (= German language in Europe and overseas, Volume 6). Wiesbaden 1979, ISBN 3-515-02985-0 .

- R [udolf] E. Keller : Luxemburgish. In: German Dialects. Phonology & Morphology, with selected texts. Manchester University Press, Manchester 1961, pp. 248-298.

- Claudine Moulin , Damaris Nübling (Ed.): Perspectives of a linguistic Luxembourg studies. Studies on diachrony and synchrony. University Press Winter, Heidelberg 2006.

- Gerald Newton (Ed.): Luxembourg and Lëtzebuergesch: Language and Communication at the Crossroads of Europe. Oxford 1996, ISBN 0-19-824016-3 .

- Caroline L. Rieger: Luxembourgish. In: Janet Duke (Ed.): EuroComGerm. Learn to read Germanic languages. Volume 2: Less commonly learned Germanic languages. Afrikaans, Faroese, Frisian, Yenish, Yiddish, Limburgish, Luxembourgish, Low German, Nynorsk. Shaker, Düren 2019, ISBN 978-3-8440-6412-4 , pp. 187-224.

- François Schanen: Parlons Luxembourgeois. Langue et culture linguistique d'un petit pays au coeur de l'Europe . L'Harmattan, Paris 2004, ISBN 2-7475-6289-1 .

- François Schanen, Jacqui Zimmer: 1,2,3 Lëtzebuergesch Grammaire. Volume 1: Le groupe verbal , Volume 2: Le groupe nominal , Volume 3: L'orthographe . Éditions Schortgen, Esch-sur-Alzette 2005-2006.

- François Schanen, Jacqui Zimmer: Lëtzebuergesch Grammaire Luxembourgeoise . Nei Versioun on a narrow volume, 480 rows. Éditions Schortgen, Esch-sur-Alzette 2012, ISBN 978-2-87953-146-5 .

- Lëtzebuergesch: Quo Vadis? Actes du cycle de conférences . Edited by Projet Moien! Sproochenhaus Wëlwerwolz. Mamer, Wilwerwiltz 2004, ISBN 2-87996-855-0 (in three languages, lb, de, fr).

- Emissions luxembourgeoises “I talk to Lëtzebuergesch - Je parle aussi le luxembourgeois” / Traditions luxembourgeoises “I know how Lëtzebuerg - Je connais aussi le Luxembourg” . Edited by ASTI (Association de Soutien aux Travailleurs Immigrés). asbl, Luxembourg, ISBN 2-9599978-5-9 (bilingual lb, fr).

Partial aspects

- Guy Berg: "I wëlle bleiwe wat mir sin". Sociolinguistic and language typological considerations on Luxembourgish multilingualism (= German Linguistics Series; Volume 140). Tübingen 1993, ISBN 3-484-31140-1 .

- A. Bertrang: grammar of the Arel dialect. Brussels 1921.

- Peter Gilles: Dialect adjustment in Lëtzebuergeschen: for the phonetic-phonological focus of a national language (= Phonai. Volume 44). M. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1999.

- Jérôme Lulling : La créativité lexicale en luxembourgeois. Doctorate, Université Paul Valéry Montpellier III, 2002.

- François Schanen: Recherches sur la syntaxe du luxembourgeois de Schengen: l'énoncé verbal . Thèse Paris IV. 1980.

- Mémorial du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg: Arrêté Ministériel portant fixation d'un système officiel d'orthographe . Règlement grand-ducal du 5 juin 1946, Mémorial A n ° 40 de 1946. Legilux.

- Mémorial du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg: Réforme du système officiel d'orthographe luxembourgeoise . Règlement grand-ducal du 30 juillet 1999. Mémorial A n ° 112 de 1999. Legilux.

Textbooks

- Gilbert Sondag, Josiane Kartheiser, Henry Wickens: Parler Luxembourgeois / Esou Schwaetze mir / Living Luxembourgish . Editions Le Phare, Esch-sur-Alzette 1996.

- Lëtzebuergesch fir all Dag, part 1: Lessons 1–8, textbook and workbook. Published by the Center de Langues Luxembourg, Unterrechtsministaer Lëtzebuerg. Edition 2000, ISBN 978-2-495-00016-1 , ISBN 978-2-495-00015-4 .

- François Schanen: Lëtzebuergesch Sproocherubriken . Éditions Schortgen, Esch-sur-Alzette 2013, ISBN 978-2-87953-174-8 .

phrasebook

- Joscha Remus : Lëtzebuergesch word for word (= gibberish, volume 104). Reise Know-How Verlag, Bielefeld 1997, ISBN 3-89416-310-0 .

- Jacqui Zimmer, François Schanen: Wéi heescht dat? ça veut dire quoi? What is that supposed to mean? - 5000 phrases pour apprendre le luxembourgeois. Editions Schortgen, Esch-sur-Alzette 2015, ISBN 978-99959-36-19-8 .

Dictionaries

- Luxembourgish dictionary. On behalf of the Grand Ducal Luxembourg Government ed. from the dictionary commission (...). Volumes I – V. Luxembourg 1950–1977 .

- JF Gangler: Lexicon of the Luxembourg colloquial language (...) with high German and French translation and explanation (...). V. Hoffman, Luxembourg 1847 .

- Dictionary of Luxembourgish dialect. M. Huss, Luxembourg 1906.

- Liette Derrmann-Loutsch: German-Luxembourgish dictionary. Éditions Saint-Paul, Luxembourg 2004, ISBN 2-87963-464-4

- Myriam Welschbillig, François Schanen , Jérôme Lulling : Luxdico German: Luxemburgish <> German dictionary. Éditions Schortgen, Luxembourg 2008, Luxdico German .

Web links

grammar

Introductions to orthography

- Introduction to Luxembourgish orthography - Lulling / Schanen (pdf) (1.20 MB)

- Mir léiere Lëtzebuergesch schreiwen ( Memento from August 16, 2002 in the Internet Archive ) (“We learn to write Luxembourgish”)

Reading samples

- Parliamentary minutes of meetings

- Text sample: Max and Moritz in Luxembourgish

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Luxembourgish. United Nations - Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, November 12, 1998, accessed November 4, 2012 .

- Online dictionary 6000 Wierder 6000 words - translate from Luxembourgish, French, German, English, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish and Italian to any of the other languages

More information about the language

- Luxembourg - A linguistic puzzle (from the Luxembourg Tourist Office)

- Eis Sprooch - De Website iwwer d'Lẽtzebuerger Sprooch. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on February 5, 2008 ; Retrieved November 4, 2012 (sources for distribution, use, structure and literature).

- Réforme du système officiel d'orthographe luxembourgeoise - The "Official Journal" with official spelling provisions

- Linguistic description of Luxembourgish with grammar, in Spanish

- Linguistica Luxemburgensia : Website with information on Luxembourgish and the language situation in the Grand Duchy.

- BiblioLux : Bibliography on Luxembourg linguistics (University of Trier, Research Center for Languages and Literatures of Luxembourg (FSL) )

- Grammatical information system for the Luxembourg verbs

- Lëtzebuerger Online Dictionnaire - Translations Luxembourgish ↔ German, French, English and Portuguese

Interviews and statements

- SMS language Luxembourgish Jérôme Lulling in an interview with Fabienne Pirsch. Télécran No. 31 (7/2005)

- Luxembourgish is a creative language Jérôme Lulling Interview in Mariekalenner / PANORAMA (1/2005)

- Audio Interview Projet Cortina with Jérôme Lulling on Radio 100komma7 (2/2003)

- Danger or chance for Luxembourgish? Pierre Mousel and Jérôme Lulling in the magazine "d'Land" (2002)

- Luxembourgish at the University of Trier Interview Lulling Trierischer Volksfreund (03/2001)

- Dream language Luxembourgish? Letter to the editor Jérôme Lulling d'WORT (01/2006)

Correction software

- Spellchecker.lu - Free correction software for Luxembourgish

- Spellchecker CORTINA - First spellchecker for Luxembourgish (Jérôme Lulling / Pierre Mousel)

- www.dico.lu - dictionnaire luxembourgeois français

Research centers

- Laboratoire de linguistique et de littératures luxembourgeoises (Universitéit Lëtzebuerg, LU)

- Luxembourg Studies: Research Center for Languages and Literatures of Luxembourg

- Institut Grand-Ducal Section de Linguistique, d'Ethnologie et d'Onomastique

- Center for Luxembourg Studies (The University of Sheffield, GB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Birgit Pfaus-Ravida: Interview with Fernand Fehlen, Peter Gilles. ( Memento from March 1, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ New Luxembourg spelling. In: Luxemburger Wort of November 15, 2019.

- ↑ Luc Marteling becomes the first director of the "Zenter fir d'Lëtzebuerger Sprooch" . In: Luxemburger Wort of June 21, 2019.

- ↑ Digital Luxembourgish Language Atlas

- ^ Mémorial : Official Gazette of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg B - No 68 (PDF); July 30, 1999 added A - No 112 (PDF)

- ↑ Law on the Use of Languages of February 24, 1984 ( Memento of February 12, 2006 in the Internet Archive ; PDF; 178 kB)

- ^ German-Luxembourgish dictionary, Glosbe. Retrieved May 7, 2020 .

- ^ A b Peter Gilles, Jürgen Trouvain: Luxembourgish . In: Journal of the International Phonetic Association . tape 43 , no. 1 , April 2013, ISSN 0025-1003 , p. 67-74 , doi : 10.1017 / S0025100312000278 ( cambridge.org [accessed May 7, 2020]).

- ↑ Verbs ending in -éieren. In: Luxogramm - Grammatical Information System for Luxembourgish. Laboratoire de linguistique et de littératures luxembourgeoises, Université du Luxembourg, accessed on May 7, 2020 (German, French, ltz).

- ↑ auxiliary verbs. In: Luxogramm - Grammatical Information System for Luxembourgish. Retrieved on May 7, 2020 (German, French, ltz).

- ↑ Verbs with the past tense. In: Luxogramm - Grammatical Information System for Luxembourgish. Retrieved on May 7, 2020 (German, French, ltz).

- ↑ modal verbs. In: Luxogramm - Grammatical Information System for Luxembourgish. Retrieved on May 7, 2020 (German, French, ltz).

- ↑ infolux.uni.lu

- ↑ infolux.uni.lu

- ↑ Chambre des Députés - Luxembourg

- ↑ See the annual literature bibliography ( Memento of November 7, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ RTL Lëtzebuerg