Reform pedagogy

Various approaches to reforming schools , teaching and general education are assigned to the term reform pedagogy , which - often referring to Comenius , Rousseau and Pestalozzi - represent pedagogy from the point of view of children . A comprehensive definition of the term is not given. Depending on the origin of the proponents, other approaches are assigned to this term and at the same time explicitly excluded from other proponents.

Concept development

The terms reform pedagogy or reform pedagogue can be found in literature as early as the 19th century , albeit still very inconsistently. For example, Jürgen Bona Meyer used the term reform pedagogy for Friedrich Froebel's pedagogy in 1863 . Two years later, the philanthropists Christian Gotthilf Salzmann and Johann Bernhard Basedow are referred to as German reform pedagogy in Karl Adolf Schmid's Encyclopedia of the Entire Education and Teaching System . Friedrich Paulsen begins the series of reform pedagogues with Wolfgang Ratke ( Ratichius ) and lets it end temporarily with the philanthropist Basedow. Rudolf Dinkler referred the term reform pedagogy in 1897 to certain educators of the 16th and 17th centuries, namely to the approaches of Johann Fischart , François Rabelais , Montaigne and Comenius . In the same year, the Herbartian Otto Willmann used the term reform pedagogy of the 18th century in a polemical differentiation from Rousseau and from philanthropism .

The term reform pedagogy for the educational movement since the turn of the century finally appeared for the first time in 1918 by the later Nazi educational scientist Ernst Krieck and was then firmly coined by Herman Nohl in his book The Pedagogical Movement in Germany and Its Theory (1933).

"Just as there was a reform pedagogy before the reform pedagogy, which is only hinted at by the figures of Comenius, Rousseau and Pestalozzi, so there is a reform pedagogy after the reform pedagogy, because the educational reform is something ongoing, which is aimed at the future and thus towards pedagogical perfection of beings remains aligned. All those who define reform pedagogy as historical and want to exclude it from the course of development are referred to the schools of reform pedagogy that currently exist and have shown their educational vitality in further development. "

In this sense, older reform pedagogy in the broader sense already includes the reform pedagogical approaches of visual and experiential education that relate to Comenius , Rousseau , Pestalozzi and philanthropism . She not only turns against the classical school system, but also against Herbartianism , which has been accused of neglecting Herbart's demands for “personal mobility” of the students and the emotional formation of original value judgments based on aesthetic examples. Therefore, of his concern to want to awaken the moral will through the formation of the intellect, only a rigid teaching scheme remained.

Reform pedagogy in the narrower sense means those attempts which at the end of the 19th century and in the first third of the 20th century turned against the alienation of life and the submissive authoritarianism of the prevailing "cramming and drill school". Instead of a didactic approach that, from today's point of view, can be seen as alienation up to and including child abuse in the education system, the reform pedagogues wanted to use a changed educational theory and learning theory to achieve a changed didactic approach that primarily focuses on the students' self-activity in action-oriented lessons . The English name is Progressive Education , the French Éducation Nouvelle . Reform pedagogy approaches after 1945 are often referred to as alternative pedagogy .

History of Reform Education

Reform pedagogy before "reform pedagogy"

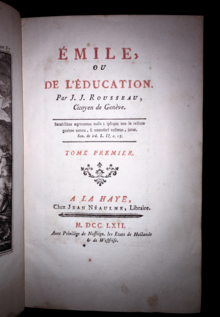

The focus of an "education from the child" was in the 17th century. in the Didactica magna by Comenius more freedom, pleasure and true research for the students. The educational novel Emile of Jean-Jacques Rousseau , a central font of enlightenment , coined the following approaches of intuition education and experiential learning just as important as Pestalozzi's main work How Gertrude teaches her children that still more the elementary education and the idea of self-activity emphasized . The aim is to lay a solid foundation that enables people to help themselves, or as the later Montessori pedagogy puts it: “Help me to do it myself.” Self-made experiences always took precedence over experiences that were merely read or listened to.

Comenius already described schools as workshops for humanity , which the philanthropists around Pestalozzi and Johann Bernhard Basedow have deepened under the keyword “ philanthropy ”. The educational writings of the Enlightenment aimed at individuality and rational action, even against tradition and a comfortable environment: "sapere aude" - "dare to use your mind" wrote Kant . The ability to think for oneself had to be learned persistently, initially under discipline to the point of being forced. So in adolescence, drills and punishments were still necessary. Only Rousseau let the educator limit himself to indirect guidance. It was not until the advances in developmental psychology that , with Rousseau, the question of what was “child-friendly” and “age-appropriate” became more pressing. The enlightenment was ambivalent with regard to the anthropological question as to whether the child was initially inherently a good soul (Rousseau) or always “radically evil” (Kant). Many later reform pedagogues tended towards Rousseau that a child only had to be able to develop itself, and emphasized the important role of cooperation in order to receive the good through social give and take. For this reason, a cohabitation of educators and children was often called for, which should not be the rule of the reasonable over the still unreasonable. The Enlightenment also spoke out in favor of constant educational experiments, so that progress towards the good could be sought in experimental schools. The Enlightenment advocated the primacy of reason and the training of the mind for self- employment; many reform pedagogues opened them up to manual activities and other things in order to avoid elitist selection and cognitive one-sidedness. They also lacked closed theories, much remained fragmentary or purely emotional in the justification of the new pedagogy.

In the 19th century, the enlightened didactics of Herbartianism prevailed in Germany for a long time . But forerunners of reform pedagogy such as Adolph Diesterweg , Karl Gottfried Scheibert and Friedrich Wilhelm Dörpfeld already criticized the strict separation between higher and lower schools and the tendency towards superficial knowledge and discipline .

Intensive period of reform pedagogy from 1890 to 1919

Around 1890, a large number of reform movements appeared more noticeably in public, advocating for the environment and home , a healthy and self-determined life , a freer society or for more beauty , naturalness and inner truthfulness in life, and almost all of which had an educational dimension. Despite all the diversity, what they had in common with reform pedagogy was that they stood up against “damage to civilization” and hoped for a “cure” for the degenerate through a new way of life. At about the same time as the youth movement , which saw young people for the first time as an independent phase of life looking for freedom and experience of nature, reform pedagogical concepts emerged that set new standards and goals for childhood and school. There was only agreement in the rejection of the old school and the old upbringing as well as the didactic orientation towards the experiences of the children instead of the subject matter or organizational aspects. Their self-activity and own choice should be at the center. The beginning is often set around 1890, when Julius Langbehn's book Rembrandt as an educator was published and the opening speech of Kaiser Wilhelm II at the school conference he convened in Berlin initiated a grammar school reform. Others did not begin until the turn of the century, including the proclamation of the century of the child by the Swedish author Ellen Key .

In Germany, in an initial turbulent phase up to 1914/18, the main concepts were:

- Arbeitsschule ( Georg Kerschensteiner ) for general and vocational training for broad sections of the population

- Rural education home ( Hermann Lietz and Gustav Wyneken ), which relies on a good learning environment and "education in the country"

- Education for tolerance and comprehensive teaching ( Berthold Otto )

- Unified school (including Johannes Tews )

- closely related to the art education movement ( Alfred Lichtwark )

- the broader youth movement .

The Bund für Schulreform , founded in 1908 - as a general German association for education and teaching - brought together reform-oriented teachers of all types of schools, representatives of school administrations, university lecturers and interested laypeople. It existed until 1933. From 1910 to 1914 the organ of the association was the magazine “ Der Säemann ”. Gertrud Bäumer , Ernst Meumann , Georg Kerschensteiner , Hugo Gaudig , William Stern and Kurt Löwenstein had a decisive influence here . At the end of December 1915, under the new name of the German Committee for Education and Teaching , the Bund became the umbrella organization for numerous associations. Peter Petersen was at the helm for a long time . Reform pedagogy, however, remained on the whole a marginal social phenomenon alongside the state and denominational school system .

German reform pedagogy in the Weimar Republic

After the First World War, many supporters or sympathizers had come to central positions in the ministries of education and were thus able to support reform pedagogical approaches. Above all, Max Hermann Baege , Max Greil , Heinrich Schulz , Carl Heinrich Becker and Ludwig Pallat should be mentioned. School directors like Fritz Karsen or Gustav Wyneken were given the opportunity to become active in educational policy. From 1914 to 1924 university educators like Herman Nohl , Wilhelm Flitner and Erich Less set the phase of stabilization (articulation and formation) of their own reform projects. From 1924 onwards, in the third phase, the theoretical foundation, criticism and interpretation, which Less called theorising , increased.

In addition, in 1919 - following on from the Bund für Schulreform (Bund für Schulreform) and as a split from the German Philologists' Association - many reform-oriented pedagogues gathered in the Bund resolved school reformers . Until the dissolution of this alliance in 1933, his followers under the leadership of Paul Oestreich pursued the goal of converting the Weimar school compromise into decisive school reform with congresses and extensive publications, such as the series Decided School Reform or in the journal Die Neue Erziehung .

According to the new Weimar Constitution , “disposition and inclination” and not social origin should decide on education. At the Reichsschulkonferenz in 1920 , in particular the rural education centers, concepts of the unified school movement and possibilities for the introduction of work and life schools were discussed. At the same time, far-reaching steps towards a democratic, co-educational upbringing were called for ( e.g. student co-administration , children's rights ). Overall, however, the reform pedagogues remained ineffective under the political conditions of the Weimar school compromise and the still prevailing school system institutions, which had been taken over unchanged from the German Empire.

Experimental schools contributed to the discussion with new concepts such as the

- Community schools ( William Lottig in Hamburg)

- Free school community Wickersdorf ( Gustav Wyneken )

- Jena Plan School ( Peter Petersen )

- Berlin Rütli School

- Karl-Marx School in Berlin-Neukölln ( Fritz Karsen )

- School by the sea on the North Sea island of Juist ( Martin Luserke ).

The modern sex education promoted by Adolf Koch and Max Hodann remained an unsolved problem in the movement . Ellen Key openly advocated Darwinist eugenics . Gustav Wyneken was convicted of pedophile abuse in court. With the pathetically evoked comradeship in the school and the charismatic leadership position of the teachers, homoerotic addictions were sometimes justified.

From the outside, the Montessori pedagogy (school in Berlin from 1919) of the Italian pedagogue Maria Montessori and the Freinet pedagogy of the French teacher Célestin Freinet also became effective , albeit slowly . Only with a few features of holistic education does Waldorf education belong in reform education.

Political orientations

There was a strong mutual influence with various movements such as the youth movement , the women's movement , the labor movement or the art education movement . Some reform pedagogues combined a strong liberal attitude with strong social commitment (including Walter Fränzel , Theodor Litt , Gustav Wyneken ), others joined socialist educational ideas (including Hans Alfken , Otto Felix Kanitz , Fritz Karsen , Siegfried Kawerau ), and there were also ethnic representatives (including Wilhelm Schwaner ). Due to the connection between various reform pedagogues and the Völkische Movement , some of their works also contain ethnic, anti-Semitic and also eugenic and racist statements (for example by Ellen Key or Peter Petersen ).

Reform pedagogy during the Third Reich

The educational reform associations ended their work in 1933, either by banning them or by dissolving themselves. Röhrs points out that even the term reform pedagogy hardly occurs in National Socialist literature.

Large parts, especially the communist, socialist or social democratically oriented part of German-speaking reform education, was silenced by the Nazis or forced into emigration. Many representatives of Jewish or Jewish origin, as well as some resistance fighters among the reform pedagogues, died in concentration camps (including Janusz Korczak , Paula Fürst , Gertrud Urlaub , Clara Grunwald , Adolf Reichwein , Elisabeth von Thadden , Kurt Adams , Theodor Rothschild ).

Relatively few reform pedagogues came to terms with the “Third Reich” and joined the NSDAP , for example, such as Fritz Jöde , Hanns Maria Lux , Heinrich Scharrelmann , Ludwig Wunder and Otto Friedrich Bollnow . Some of the reform pedagogical schools that survived were subjected to a profound National Socialist transformation, such as the Odenwaldschule or Wickersdorf. Reform pedagogical elements were used externally through education under National Socialism : the (völkisch) community idea, the HJ / BDM camp education far from the adult world, the principle "youth leads youth" ( Baldur von Schirach ), the abandonment of teaching towards intuition and experience, the appreciation of physical education.

International reform education before 1933

Reform pedagogical impulses were also taken up and further developed outside of the German area. After the United Kingdom accounted Cecil Reddie , who had studied in Göttingen and 1882-83 PhD, the idea of the country boarding home in the Abbotsholme School ( Derbyshire ) in 1889. He knew the Herbartians Wilhelm Rein , the Hermann Lietz sent to him. He repeatedly invited well-known German educators there. Alexander S. Neill , who founded Summerhill in 1927 , was also strongly influenced by German ideas , also inspired by his German wife Lilian and Hermann Harless in Hellerau . In the USA, John Dewey took up ideas from Froebel and others since the 1880s. His student William Heard Kilpatrick followed him and specified many concepts. After 1900, the teacher Helen Parkhurst developed the Dalton Plan in close collaboration with Maria Montessori. The central figure of the Progressive Education Association became the teacher Marietta Johnson . In France Paul Robin , Edmond Demolins and Sebastien Faure created new educational reform institutions, in Belgium Ovide Decroly , in Switzerland Adolphe Ferrière and Édouard Claparède . Maria Montessori should be mentioned for Italy, the anarchist Francisco Ferrer for Spain , and Janusz Korczak for Poland . Outside Europe, Rabindranath Tagore in India and, after 1945, Paolo Freire in South America were important reform educators.

The New Education Fellowship , which was founded in 1921 on the initiative of Beatrice Ensor , Elisabeth Rotten and Adolphe Ferrière and was the international forum for reform educators, played a central role . The New Education Fellowship published the magazine " The New Era " and between 1923 and 1932 organized conferences in Montreux, Heidelberg, Locarno, Helsingör and Nice with broad international participation. In the German-speaking area, in addition to Rotten, Karl Wilker was particularly keen to expand the international working group for the renewal of education into a section. Both published the magazine “ The Age of Development ”. However, it was not officially founded until after the Heidelberg Conference in 1931 under the name of the World Association for the Renewal of Education . The board of directors included Erich Less (Chairman), Carl Heinrich Becker , Julius Gebhard , Robert Ulich and Leo Weismantel .

Development since 1945

In German-speaking countries, the reform pedagogues who were still alive after 1945 were initially unable to build on their importance in the twenties, both in the area of the rural education home movement and in psychoanalytic pedagogy ( Siegfried Bernfeld , Anna Siemsen ).

In the Soviet occupation zone , reform pedagogues such as Paul Oestreich , Heinrich Deiters , Ernst Wildangel and Erwin Marquardt were included in the rebuilding of school and popular education with their demands for the introduction of a democratic, socialist unified school. On the basis of the law passed in 1946 to democratize German schools , school reformers saw the possibility of a fresh start. In particular, following on from the unified school movement before 1933, which wanted to promote the individual talents and interests of the students and to combine theory and practice in the classroom in the sense of a working school , reform-pedagogical ideas found their way into the school system of the Soviet occupation zone and the later GDR . However, from 1950 onwards, Soviet pedagogy became decisive, but above all the leading role of the teacher and the central control should not be questioned, the democratization of the school failed to materialize.

The World Association for the Renewal of Education was re-established on the initiative of Elisabeth Rotten under the direction of Franz Hilker . Among the employees was Hermann Röhrs . The current President is Gerd-Bodo von Carlsburg , Vice-President Uta-Christine Härle.

In contrast, Montessori and Waldorf education were able to re-establish themselves. More recent approaches from non-German-speaking areas such as the democratic Summerhill school , on the other hand, were hardly taken up. Only with the 1968 movement did the earlier approaches come into their own again. Alexander Sutherland Neill achieved his first major book success with The anti-authoritarian education . As alternative education today, among others, which are Freinet pedagogy that Deschoolings concept and the anti-pedagogy called, with respective associated alternative schools ( alternative school , free alternative school , free school , democratic school ).

Overall, some reform-pedagogical ideas have penetrated the state school system: This applies to the cooperation between kindergarten and school, early language learning, age-independent and interdisciplinary teaching, weekly planning, the abolition of staying seated and all-day school. The extent to which reform and alternative pedagogical approaches can really be integrated into mainstream schools is controversial within reform and alternative education (see also Laborschule Bielefeld , Oberstufen-Kolleg Bielefeld and Glockseeschule ). But the u. a. Open teaching concept, represented by Hans Brügelmann and Falko Peschel , in which the individual learning projects of the children are decisive for what happens in the classroom.

Internationally, on the other hand , the teaching and learning model based on the ideas of Comenius , Rousseau , Pestalozzi and Montessori of “ traffic education from the child ”, with which the didactician Siegbert A. Warwitz reformed traffic education since the 1970s, has obviously established itself . The "traffic education of the needs of traffic" and the "accident avoidance", which were customary up to then, regarded the child as an unfinished adult and the traffic instruction as an adaptation of behavior to the official traffic rules.

Guiding principles and currents

In the historical perspective and in the current presence, the following are among other things referred to as educational reform movements:

- Compulsory schooling based on pedagogy from the child

- Teacher education movement

- School garden or allotment garden movement

- Philanthropic Movement

- Visual education

- Experiential education

- Pestalozzi pedagogy

- Kindergarten movement

- Community college movement

- the concept of self-activity

- Art education movement , youth music movement

- Occupational education (associated with the concepts of the work School , College Degree , production school )

- the concept of " learning by doing " (learning by doing)

- Learning through teaching (constructivist method by Jean-Pol Martin )

- School community movement (Free School Community)

- Freinet pedagogy , founded by Célestin Freinet in France in 1920

- Country Education Movement

- Laboratory school , project school , private tutor school

- Concepts such as project learning , project work , project teaching , learning laboratory

- School farm movement

- Co-education movement

- Community school , comprehensive school , comprehensive school

- Waldorf Education

- Montessori pedagogy

- Mannheim school system

- Children's rights movement , the concept of the children's republic

- Humanities education

- Forest education , forest kindergarten

- Leisure education

- Anti-authoritarian education , democratic school , children's shop

- Alternative education , alternative school

- Basic rules of positive child-rearing according to Oscar Schellbach

- partly also anti-educational approaches

Reform pedagogical attitude in the past and present

According to Sebastian Idel / Heiner Ulrich (2017), no distinction is made in the academic discussion “between reform pedagogy as a historically past form and reform pedagogical initiatives of the present.” Nevertheless, Idel / Ulrich emphasize five elements of the reform pedagogical stance as an educational code (ibid., P. 11): (1) romantic conception of the child as a creative, not alienated being; (2) relationship between child and parent on a partnership level; (3) Designing the school as a living space: via a family-like way of life and a rich school life; (4) Technical knowledge is to be adapted as far as possible to the child's understanding; (5) School content should be relevant to the subject, developed together with the students and conveyed in a project-oriented manner.

See also

- Aesthetic education

- Democratic education

- Art therapy

- Child orientation

- School association view over the fence as a contemporary continuation

literature

Introductions and manuals

- Wolfgang Keim , Ulrich Schwerdt (Ed.): Handbook of Reform Education in Germany (1890-1933). Part 1: Social contexts, central ideas and discourses. Part 2: Fields of practice and educational action situations. Frankfurt am Main et al. 2013, ISBN 978-3-631-62396-1 .

- Hermann Röhrs (ed.): The reform pedagogy. Origin and course from an international perspective. 6th, revised and supplemented edition. UTB, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8252-8215-5 .

- Willy Potthoff : Introduction to Reform Education. From classic to current reform pedagogy. 3. Edition. Freiburg 2000, ISBN 3-925416-23-4 .

- Irene Blechle: discoverer of university education. The university reformers Ernst Bernheim 1950–1942 and Hans Schmidkunz 1863–1934. 1st edition. Shaker Verlag, 2002, ISBN 3-8265-9943-8 .

- Friedrich Koch : The dawn of pedagogy. Worlds in your head: Bettelheim, Freinet, Geheeb, Korczak, Montessori, Neill, Petersen, Zulliger. Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-434-53026-6 .

- Dietrich Benner , Herwart Kemper : Theory and history of reform pedagogy. 3 volumes. Beltz, Weinheim / Basel 2003, ISBN 3-8252-8240-6 .

- Ehrenhard Skiera: Reform Education in Past and Present. A critical introduction. Munich 2003, ISBN 3-486-27413-9 .

- Hein Retter (ed.): Reform pedagogy. New approaches - findings - controversies. Klinkhardt, Bad Heilbrunn 2004.

- Jürgen Oelkers : Reform pedagogy - a critical dogma story. 4th fully revised and expanded edition. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 2005, ISBN 3-7799-1525-1 .

- Till-Sebastian Idel, Heiner Ulrich (Hrsg.): Handbook of reform pedagogy. Beltz, Weinheim / Basel 2017, ISBN 978-3-407-83190-3 .

Special literature: Reform pedagogy in the current debate

- Matthias Hofmann : Alternative schools - alternatives to school. Klemm u. Oelschläger, Ulm 2015, ISBN 978-3-86281-086-4 .

- Matthias Hofmann: Past and present of independent alternative schools. An introduction. Ulm 2013, ISBN 978-3-86281-057-4 .

- Damian Miller, Jürgen Oelkers (eds.): Reform pedagogy after the Odenwald school - what next? Beltz, Weinheim / Basel 2014, ISBN 978-3-7799-2929-1 .

- T. Schulze: Good reasons for reform pedagogy - then and now. In: U. Herrmann, S. Schlüter (ed.): Reform pedagogy - a critical-constructive visualization. Klinkhardt, Bad Heilbrunn 2011.

- Hans Brügelmann : Without personal attention, education degenerates into technology. The blanket criticism of reform pedagogy is wrong. In: Pedagogy. 62nd vol., Vol. 7-8, 2010.

- Hein Retter : Classical Reform Education in Current Discourse. Jena 2010, ISBN 978-3-941854-27-7 .

Special literature: subjects, people, schools

subjects

- Jürgen Oelkers: Eros and domination. The dark sides of reform pedagogy. Beltz, Weinheim / Basel 2011, ISBN 978-3-407-85937-2 .

- Winfried Böhm , Waltraud Harth-Peter, Karel Rýdl, Gabriele Weigand, Michael Winkler (eds.): Snow from the past century. New Aspects of Reform Education. Ergon Publishing House. Würzburg 1994, ISBN 3-928034-46-4 .

- Siegbert A. Warwitz : Traffic education from the child. Perceive-play-think-act. 6th edition. Schneider-Verlag, Baltmannsweiler 2009, ISBN 978-3-8340-0563-2 .

- Ralf Koerrenz : Reform Education. Studies on the philosophy of education. Jena 2004, ISBN 3-934601-99-5 .

- Michael Knoll: Dewey, Kilpatrick and "progressive" upbringing. Critical studies on project pedagogy. Klinkhardt, Bad Heilbrunn 2011, ISBN 978-3-7815-1789-9 .

- Norbert Collmar, Ralf Koerrenz (ed.): The religion of the reform pedagogues. A work book. Weinheim 1994.

People and schools

- Ullrich Amlung, Dietmar Haubfleisch, Jörg-W. Link, Hanno Schmitt (Ed.): Overcoming the old school. Reform educational experimental schools between the German Empire and National Socialism. (= Socio-historical studies on reform pedagogy and adult education. 15). Frankfurt 1993, ISBN 3-7638-0185-5 .

- Dietmar Haubfleisch: Berlin reform pedagogy in the Weimar Republic. Overview, research results and perspectives. In: Hermann Röhrs, Andreas Pehnke (Ed.): The reform of the education system in the East-West dialogue. History, tasks, problems. (= Greifswald studies on educational science. 1). Frankfurt am Main et al. 1994, pp. 117-132. (New edition: Marburg 1998: http://archiv.ub.uni-marburg.de/sonst/1998/0013.html )

- Dietmar Haubfleisch: Scharfenberg Island School Farm . Microanalysis of the educational reality of reform pedagogy in a democratic experimental school in Berlin during the Weimar Republic. (= Studies on educational reform. 40). Frankfurt et al. 2001, ISBN 3-631-34724-3 .

- Martin Näf: Paul and Edith Geheeb -Cassirer. Founder of the Odenwald School and the Ecole d'Humanité. German, Swiss and International Reform Education 1910–1961 . Beltz, Weinheim / Basel 2006, ISBN 3-407-32071-X .

- Manfred Berger : Clara Grunwald . Pioneer of Montessori education. Frankfurt am Main 2000, ISBN 3-86099-294-5 .

- Michael Knoll (Ed.), Kurt Hahn : Reform with a sense of proportion. Selected writings by a politician and educator. with a foreword by Hartmut v. Hentig. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1998.

- Jörg-W. Link: Reform education between Weimar, World War I and the economic miracle. Educational ambivalences of the rural school reformer Wilhelm Kircher (1898-1968) (= studies on culture and education. 2). Hildesheim 1999.

- Andreas Pehnke : I belong in the children's party! The Chemnitz social and reform pedagogue Fritz Müller (1887–1968): marginalized in dictatorships - forgotten and rediscovered in democracies. Sax-Verlag, Beucha (near Leipzig) 2000.

- Andreas Pehnke (Ed.): “Reform pedagogy from a pupil's point of view ” Documents from a spectacular Chemnitz school experiment in the Weimar Republic. Schneider-Verlag, Hohengehren 2002.

- Adrian Klenner: Reform pedagogy in concrete terms: life and work of the teacher Carl Friedrich Wagner - a reform pedagogue at the Hamburg experimental school Telemannstrasse 10. (= Hamburg series of publications on school and teaching history. Volume 10). Kovač, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-8300-1018-4 .

- Helga Jung-Paarmann: Reform pedagogy in practice - history of the Bielefeld upper level college. Volume 1: 1969-1982. Bielefeld 2010, ISBN 978-3-921912-52-2 .

- Ellen Schwitalski: Become who you are. Pioneers of the Odenwald School . The Odenwald School in the German Empire and the Weimar Republic. transcript, Bielefeld 2005.

- Ralf Koerrenz: School model: Jena plan. Basics of a reform pedagogical program. Paderborn 2011, ISBN 978-3-506-77228-2 .

- Ralf Koerrenz: Country education homes in the Weimar Republic. Alfred Andreesen's determination of the function of the Hermann Lietz schools in the context of the years from 1919 to 1933. Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-631-44639-X .

- Inge Hansen-Schaberg : Minna Specht - A Socialist in the Rural Education Movement (1918–1951) . Frankfurt et al. 1992.

- Sebastian Engelmann: Pedagogy of Social Freedom - An Introduction to the Thinking of Minna Specht. Paderborn, 2018, ISBN 978-3-506-72849-4 .

Web links

- School association 'view over the fence'

- Research and study archive, collection of documents on the three phases of modern reform pedagogy, educational reform and educational theory development

- the server for reform education

- World Federation for the Renewal of Education (with publications of theses on reform pedagogy and reviews)

- German Society for Democracy Education

- Education server South Tyrol , documentation on reform pedagogy

- Hager, Maik: Reform Education. Definition of terms, history and people (www.geschichte-erforschen.de).

Individual evidence

- ^ Jürgen Bona Meyer: Confession of religion and school. A historical account. 1863, p. 74.

- ^ Encyclopedia of all education and instruction. Volume 4, 1865, p. 325.

- ↑ Friedrich Paulsen: History of the learned instruction in German schools and universities: from the end of the Middle Ages to the present. 1885, p. 485.

- ↑ Rudolf Dinkler: The concept of naturalness in the first stages of its historical development. Mainly among the reform pedagogues of the 16th and 17th centuries. 1897.

- ↑ Otto Willmann: Historical Pedagogy. In: EHP. 3, 1897, pp. 705-709.

- ^ Franz Reinhard Müller: David Williams' reform efforts in the field of education. 1898 (Diss. Leipzig)

- ^ Heinz-Elmar Tenorth : Reform pedagogy. Another attempt to understand an amazing phenomenon. In: Journal for Pedagogy. 1994, No. 6, pp. 587ff.

- ^ Hermann Röhrs : Reform pedagogy and internal educational reform. 1998, p. 241.

- ^ Johann Amos Comenius: Great didactics. 1992, p. 1.

- ↑ Heinrich Pestalozzi: How Gertrud teaches her children: an attempt to give the mothers instructions to teach their children themselves, in letters. Bad Schwartau 2006, ISBN 978-3-86672-024-4 .

- ^ Comenius: Great didactics. 1970, p. 59.

- ↑ Jürgen Oelkers: The reform pedagogy BEFORE the "reform pedagogy". In: Reform pedagogy: a critical history of dogmas. 2005, p. 26 ff.

- ↑ Herwig Blankertz: The history of education: from the Enlightenment to the present . 1982, ISBN 978-3-88178-055-1 , pp. 214 .

- ^ Wolfgang R. Krabbe: Life reform / self reform . In: D. Krebs, J. Reulecke (Ed.): Handbook of German Reform Movements 1880-1933 . Peter Hammer, Wuppertal 1998, ISBN 3-87294-787-7 , p. 73 f .

- ^ Jürgen Oelkers : Reform pedagogy. A critical story of dogma. 2005, p. 27.

- ↑ Wolfgang Scheibe : The educational reform movement 1900-1932. 1999.

- ^ A b Hermann Röhrs: Reform pedagogy and internal educational reform. 1998, p. 39.

- ^ Jürgen Oelkers: Reform pedagogy: a critical dogma story. 2005, p. 183.

- ↑ Jürgen Oelkers: Eros and rule. The dark sides of reform pedagogy. Basel 2011.

- ^ Hermann Röhrs , Reform Pedagogy and Internal Educational Reform , 1998, p. 68.

- ↑ Dennis Shirley: Reform Education in National Socialism: The Odenwald School 1910 to 1945. 2010.

- ^ Hermann Röhrs, Reform Pedagogy and Internal Educational Reform. P. 448.

- ↑ Silence, stutter, clarify. In: The time. March 18, 2010, p. 72.

- ^ Siegbert A. Warwitz: Traffic education from the child. Perceive-play-think-act. 6th edition. Schneider-Verlag, Baltmannsweiler 2009.

- ↑ Till-Sebastian Idel, Heiner Ulrich: Introduction . In: Handbook of Reform Education . Beltz, Weinheim, Basel 2017, ISBN 978-3-407-83190-3 , p. 8 .