Cervical cancer

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| C53 | Malignant neoplasm of the cervix uteri |

| C53.0 | Endocervix |

| C53.1 | Ectocervix |

| C53.8 | Cervix uteri, overlapping several parts |

| C53.9 | Cervix uteri, unspecified |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The cervical carcinoma ( Latin carcinoma cervicis uteri ), also called collum carcinoma (from Latin collum 'neck' ) or cervical cancer , is a malignant ( malignant ) tumor of the cervix (cervix uteri). It is the fourth most common malignant tumor in women worldwide. Histologically , the majority of the cases are squamous cell carcinoma . The most common cause of cervical cancer is infection with certain types of the human papillomavirus (HPV). At first, cervical cancer does not cause any pain, only occasional light spotting occurs. Only when the tumor becomes larger and disintegrates with ulcer formation does a flesh-colored, sweet-smelling vaginal discharge occur . In the early stages, the complete removal of the change by means of a conization is sufficient. At an advanced stage, the entire uterus with surrounding tissue and sometimes other organs must be removed . An examination for early detection is the Pap test . A vaccination with an HPV vaccine prevents infection by the two most common high-risk HPV types, thereby reducing the risk of developing cervical cancer.

Epidemiology

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common malignant tumor in women worldwide and the seventh most common overall. In 2012, 528,000 women worldwide fell ill, and around 266,000 died of it. In the worldwide cause of death statistics for gynecological malignancies , (invasive) cervical carcinoma in particular ranks first, with a mortality rate of over 60 percent.

frequency

The frequency ( incidence ) of cervical cancer varies significantly around the world. It is 3.6 in Finland and 45 per 100,000 women per year in Colombia . In Germany it was 13.3 per 100,000 in 2002. Higher-grade precancerous lesions of the cervix uteri are around 50 to 100 times more common. It used to be the most common genital cancer in women, but early detection tests have reduced the incidence in Central Europe to around 25 percent of all genital cancers . In contrast, the incidence of cervical cancer precursors shows an increasing trend. In Germany, cervical cancer is the eleventh most common type of cancer diagnosed . At the same time, the disease is the twelfth leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Every year over 4,700 women in Germany develop cervical cancer and around 1,500 die from it. The patient's 5-year survival rate is about 69%.

Recognition age

Cervical carcinoma is most commonly diagnosed between the ages of 45 and 55; precursors can occur in patients aged 20 to 30. The mean age at first diagnosis of cervical cancer has decreased by 14 years over the past 25 years and is currently around 52 years. The age distribution shows a peak between the ages of 35 and 54 and a further increase from the age of 65. In 2003, the incidence of the disease showed a different age distribution because the diagnosis was made significantly more often in women between the ages of 25 and 35 than in women who were over 65 years of age. The disease can also occur during pregnancy. The frequency here is 1.2 per 10,000 pregnancies.

causes

About 97% of cervical cancers are associated with the human papillomavirus (HPV). Infection with the HP viruses type 16 and type 18 is the most common. (see S3 guideline cervical cancer from 2014)

Other factors such as smoking, genital infections, long-term use of oral contraceptives , a high number of previous births (high parity ) and the suppression of the immune system are under discussion as to promoting the development of cancer in high-risk HPV infections. Other predisposing factors include the early onset of sexual intercourse, high promiscuity, as well as poor sexual hygiene in both partners and low social status .

However, some diseases are also known in some very young women without recognizable risk factors. One of the first was described as early as 1887. By intrauterine devices , the risk of cervical cancer after a large meta-analysis does not increase from 2011, but decreased.

HPV infection

The pathogens, also known as condyloma viruses, were formerly part of the Papovaviridae family . They are spherical, non-enveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses (dsDNA) (from the group of Papillomaviridae ), of which around 200 different types are known. Most of them are relatively harmless to humans, but can cause uncomfortable genital warts . Types 16 and 18 can be detected in situ in 70 percent of cervical carcinomas, cervical intraepithelial neoplasms and adenocarcinomas . They are also common in anal cancer . Types 6 and 11 are responsible for more benign (i.e., non- metastatic or invasively growing) tumors such as genital warts and are also found in other tumors such as B. in papillomas in the oropharynx . In addition to these, at least 18 other HP virus types have already been discovered in cervical tumors. According to the current state of knowledge, it cannot be ruled out that other types are also pathogenic.

In contrast to influenza viruses, for example, humans are the main or reservoir host for all of the HP virus types mentioned . The viruses have adapted to the human organism. Damage to their reservoir host has no beneficial effect for them, since they are dependent on it for their own reproduction. The cervical carcinomas caused by these viruses in the reservoir host are ultimately only side effects of the infection .

Infection with these viruses usually takes place in adolescence through contact infection or smear infection during the first sexual contact . These viruses can then remain inactive for years.

However, infection is also possible without sexual contact, for example during childbirth. In babies, HPV types 6 and 11 can very rarely lead to growths (laryngeal papillomas) on the larynx . Transmission of other types of HPV in this way seems possible. Transmission through other physical contact, such as between hands and genitals, also seems possible. Other transmission routes, such as swimming pools or contaminated toilets, are being discussed, but have not yet been proven.

If the viruses have succeeded in penetrating the basal cells ( cells in the deep cell layers of epithelia on or near the basement membrane ) of the cervix, they induce them to produce their viral genetic material, which they - like all viruses - cannot do themselves. The cells must therefore also be stimulated to divide or kept in the division state so that they can produce the viral genetic material. And it is precisely during this process that the following errors occur: The pathogen viruses switch off the control molecules of the cervical cells, which usually limit cell division or, in the event of an incorrect division process , can send the cell into programmed cell death ( apoptosis ) (p53 and pRB). Tumor formation also requires the virus genome to be incorporated into the genome of the host cell . This process occurs spontaneously (accidentally), it is not controlled enzymatically . This alone is usually not enough for tumor formation, but it promotes further damage that ultimately leads to tumor formation. As soon as the tumor cells have broken through the basement membrane, they can reach other parts of the body with the blood or lymph fluid, where they can multiply and thereby create so-called daughter tumors ( metastases ).

Normally, a healthy and strong immune system recognizes such changed cells and kills them. About 70 percent of infected patients eliminated the virus in question after two years.

However, in some women the pathogens in question manage to overcome the immune system in a way that is not yet known. In high-risk HPV types, this is the case in about one in ten infections. In such cases, one speaks of a persistent infection if the viruses are detectable for more than 6 to 18 months. According to current knowledge, this is a prerequisite for the virus-related development of cancer. If high-risk types can still be detected in a woman 18 months after the initial diagnosis of HPV infection, the probability of developing cervical cancer is about 300 times higher for the woman than for a woman who is not (no longer) infected. The women concerned can develop cervical cancer within 10 to 20 years after infection. This connection also explains why this cancer is currently being diagnosed especially in women between the ages of 35 and 40 and has recently shown a clear trend towards younger age. It fits in with the tendency in modern societies towards earlier sexual activity and the higher average number of sexual partners.

Smoke

Smoking is an independent risk factor for the development of cervical cancer. High-risk HPV-infected smokers have a higher risk of developing the disease than high-risk HPV-infected women who have never smoked. In particular, an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma was demonstrated, not for adenocarcinoma. The risk apparently depends on the number of cigarettes smoked per day and the age at which smoking was started, and it persists even in former smokers. Carcinogenic breakdown products of tobacco smoke were found in the cervical mucosa. HPV infections persist longer in female smokers, so that more persistent infections occur here.

Other genital infections

It is suspected that an additional infection of the genital area with other sexually transmitted pathogens such as chlamydia and herpes simplex 2 can contribute to the development of cancer if an infection with high-risk HPV is already present.

Emergence

The disease is caused by changes of cells and tissue structures finally stepwise from a so-called cervical intraepithelial neoplasia ( English cervical intraepithelial neoplasia ) (CIN I-III). The dysplastic cell changes in CIN I and II are considered to be reversible. CIN III, on the other hand, is an obligatory precancerous condition . This means that more than 30 percent develop into cancer within five years. Because of the same biological behavior, high-grade dysplasia and carcinoma in situ (CIS) are grouped under CIN III .

- Cervical intraepithelial neoplasms in the histological image under the microscope

Course of the disease / symptoms

Only 2 to 8 percent of HPV-infected women develop cell changes that represent a preliminary stage for cancer, or even a subsequent carcinoma.

Cervical carcinomas usually develop completely inconspicuously and without pain. Occasionally, more or less light spotting can indicate such an occurrence. Only when the tumor becomes larger and disintegrates with ulcer formation does it come to flesh-water-colored, sweet-smelling vaginal discharge , irregular bleeding and contact bleeding during sexual intercourse .

If left untreated, the tumor grows into the urinary bladder , rectum and other structures of the small pelvis such as the ureters , damages or even destroys them and leads to sequelae such as congestion of the kidneys or lymphedema of the legs. In addition, metastases can occur in other parts of the body because tumor cells spread through the lymph vessels ( lymphogenic ) and the bloodstream ( hematogenic ) in the body and can settle and multiply elsewhere.

Pregnancy does not affect the course of the disease. There is no direct danger to the children either. However, if the child is born naturally, there may be growths on the larynx.

Investigation methods

The diagnosis of cervical cancer can only be made by histological examination of pieces of tissue. These are prepared either by a selective sampling of an in colposcopy striking area on the cervix , a conization by repeatedly striking Pap test or curettage obtained in suspected contained in the cervix channel change. In cases of proven carcinoma are for staging an X-ray examination of the lung , a sonography through the sheath , a sonography of both kidneys and the liver , a cystoscopy and rectoscopy to exclude or detection of a tumor in slump bladder or rectum necessary. From the FIGO IB2 stage, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended to determine the extent of the tumor , as this is suitable as a supplement to the palpation examination to determine the size of the tumor in the pelvis, the relationship to the neighboring organs and the depth of penetration .

pathology

The majority of all invasive cervical carcinomas are squamous cell carcinomas (80 percent), followed by adenocarcinomas (5–15 percent). The preferred place of origin is the so-called transformation zone, in which the squamous epithelium of the portio meets the columnar epithelium of the cervix. Other types of tumors, such as adenocancroids, adenosquamous, and mucoepidermoid carcinomas, are rare. As a specialty, so-called Gartner's duct carcinomas occur, also rarely. They start from Gartner's passage, a small part of the regressed Wolff's passage . Since this type of tumor develops in depth and only breaks through into the cervical canal as it progresses, the usual early detection does not help here. Sarcomas of the uterus can very rarely affect the cervix. Müller's mixed tumors , in which carcinomatous and sarcomatous components occur in the same tumor, occupy a special position . They are also more likely to affect the body of the uterus than the cervix.

Tumor typing is done by the WHO - classification , staging before surgery clinically after the FIGO classification . After surgical treatment, the stages are classified according to the pTNM classification , which includes a histological assessment by a pathologist and is indicated in the stage designation by a preceding small p . The degree of differentiation of the cancerous tissue is assessed according to the UICC (Union Internationale Contre le Cancer) .

| TNM | FIGO | criteria |

|---|---|---|

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | |

| T0 | No evidence of a tumor | |

| Tis | ("Carcinoma in situ") | No breakthrough through the basement membrane into healthy tissue, corresponds to a CIN 3 |

| T1 | I. | Cervical cancer limited to the cervix |

| 1a | IA | Visible only under the microscope, stroma invasion up to and including 5 mm (TNM below 7 mm horizontal extension, no longer defined in FIGO classification) |

| 1a1 | IA1 | Visible only under the microscope, stroma invasion up to and including 3 mm (TNM below 7 mm horizontal extension, no longer defined in FIGO classification) |

| 1a2 | IA2 | Visible only under the microscope, stroma invasion more than 3 to 5 mm inclusive (TNM below 7 mm horizontal extension, no longer defined in FIGO classification), so-called micro carcinoma |

| 1b | IB | Clinically recognizable lesions limited to the uterine cervix or subclinical lesions larger than stage IA |

| 1b1 | IB1 / 2 | Clinically recognizable lesions, smaller than 4 cm (the FIGO classification since 2019 differentiates between tumors <2 cm [FIGO IB1] and those 2 cm to <4 cm [FIGO IB2]) |

| 1b2 | IB3 | Clinically recognizable lesions, at least 4 cm |

| T2 | II | Cervical cancer that has crossed the boundary of the uterus but does not reach the pelvic wall or the lower third of the vagina |

| 2a | IIA | Infiltration of the vagina without infiltration of the parametrium |

| 2a1 | IIA1 | Infiltration of the vagina , without infiltration of the parametrium, clinically visible, not larger than 4 cm |

| 2a2 | IIA2 | Infiltration of the vagina , without infiltration of the parametrium, clinically visible, larger than 4 cm |

| 2 B | IIB | With infestation of the parametrium |

| T3 | III | Involvement of the lower third of the vagina and / or the pelvic wall and / or kidney congestion and / or kidney failure |

| 3a | IIIA | Involvement of the lower third of the vagina, no involvement of the pelvic wall |

| 3b | IIIB | Infection of the pelvic wall and / or hydronephrosis or kidney failure |

| T4 | IV | Involvement of the bladder, rectum, distant metastasis |

| 4th | IVA | Tumor infiltrates the mucous membrane of the bladder or rectum and / or crosses the small pelvis |

| 4th | IVB | Distant metastases or no assessment of distant metastases |

| Nx | No statement can be made on regional lymph node metastases . | |

| N0 | No metastases in the regional lymph nodes. | |

| N1 | Metastases in the regional lymph nodes. | |

| M0 | No distant metastases detectable. | |

| M1 | The tumor has formed distant metastases. | |

| 1a | Metastases in other lymph nodes (non-regional, e.g. para-aortic, lymph nodes). | |

| 1b | Metastases in the bones. | |

| 1c | Metastases in other organs and / or structures. |

Notes: The UICC and FIGO classifications have been aligned for the T and M stages. The FIGO does not use stage 0 (= Tis). The N stage (lymph node involvement) is only included in the UICC (TNM) classification. The following are defined as regional lymph nodes (LK):

- paracervical LN

- parametric LK

- Hypogastric LN on the internal iliac arteries

- LK to the common iliac arteries

- LK to the arteriae ilicae externae

- presacral LK

- lateral sacral LK

According to the TNM classification of the UICC, the para-aortic and inguinal LNs are not regional. If infected, there is a stage M1.

The Figo classification from 2019 now defines affected, regional lymph nodes as stage IIIC. In contrast to the TNM classification of the UICC, paraortal lymph nodes up to the left ranalis are rated as regional lymph nodes and not as distant metastases. Affected pelvic lymph nodes define stage IIIC1 and affected paraortic lymph nodes define stage IIIC2.

|

Squamous cell carcinoma ("Squamous lesion") |

Adenocarcinomas ("glandular lesions") |

Special manifestations ("Other epithelial lesion") |

|---|---|---|

|

Special variants of adenocarcinomas:

Mixed types |

Neuroendocrine carcinomas:

Undifferentiated small cell "non- endocrine " carcinomas |

treatment

The therapy of cervical cancer and its preliminary stages depends on the respective stage:

Pre-cancer treatment

A cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) I can regularly cytological and colposcopy are observed over a maximum of 24 months in the spacing of six months, when the changes in the outer portion of the cervix are easy to control. The changes can recede or develop further. The prerequisite for this is a reliable diagnosis through sampling and histological examination. CIN I inside the cervix (intracervical location, not easily observable) should soon be treated with a conization . A follow-up and thus a postponement of the treatment is also possible in the case of CIN II and III during pregnancy in order to wait for the child's viability. Outside of pregnancy, CIN II that lasts for twelve months and CIN III should have surgery.

In the case of carcinoma in situ , no further treatment is necessary after the change has been completely removed by a conization or - in the case of a completed family planning - after complete removal of the uterus ( hysterectomy ). If the removal is incomplete, there is the possibility of a new conization. A conization can also be carried out during pregnancy if there are strict indications . In the case of carcinoma in situ with complete removal of the changes caused by the conization, the pregnancy can be carried to term and the risk of premature birth is then increased. A normal birth is possible. Another colposcopic and cytological check should be carried out six weeks after the birth.

Treatment of cervical cancer

In the FIGO IA1 stage, as in the precancerous stages, a conization can be sufficient if the tumor has been completely removed and there is still a desire to have children, whereby the risk of cervical insufficiency or stenosis during pregnancy is increased. If you do not wish to have children, you should simply have the uterus removed. In the event of a rupture of the lymph vessels, additional pelvic lymph node removal is indicated.

In stages IA2, IB, IIA, and IIB, an extended hysterectomy (radical hysterectomy) and systematic pelvic , and depending on the stage, a para- aortic lymphadenectomy (removal of all lymph nodes located on the aorta ) is indicated. The Wertheim-Meigs operation has so far been used as the standard therapy. With squamous cell carcinoma, the ovaries may be preserved in young women. If there is adenocarcinoma, removal is recommended even in young women because of the higher probability of metastasis in the ovaries. Depending on the histological findings, radiation therapy or radiochemotherapy may be necessary after the operation .

The classification according to Piver, or Rutledge-Piver, differentiates five degrees of radicality of a hysterectomy in cervical cancer. It was named after the American gynecologists M. Steven Piver and Felix Rutledge.

| Piver stage | designation | Extension of the intervention |

|---|---|---|

| I. | extra fascial hysterectomy |

|

| II | modified radical hysterectomy |

Ultimately, it is an extrafascial hysterectomy with resection of the parametria medial to the ureters. |

| III | “Classic” radical hysterectomy |

|

| IV | advanced radical hysterectomy | like Piver III, but with

|

| V | - | like Piver IV, but additionally

|

As an alternative, total mesometrial resection (TMMR) with a nerve-sparing dissection technique (targeted exposure) in anatomical-embryonic developmental limits and renouncing subsequent irradiation with the same or even better survival data , laparoscopically assisted vaginal radical hysterectomy (LAVRH), are now available at centers. with nerve-sparing vaginal radical surgery and laparoscopic lymph node removal as well as laparoscopic radical hysterectomy (LRH) with complete laparoscopic dissection.

If you still want to have children in stages IA2 and IB1 with tumors <2 cm, a radical trachelectomy according to Dargent with lymphadenectomy and thus preservation of fertility can be considered if it is a squamous cell carcinoma, the lymph nodes are tumor-free and no other risk factors are present . These procedures are currently not routine, but they can offer advantages to patients by protecting the nerves responsible for urinary bladder and bowel emptying , such as avoiding re-radiation after surgery for TMMR, or preserving fertility with trachelectomy.

In stages III and IV, primary combined radiation therapy or, better still, simultaneous chemoradiation is required. With a central tumor location with bladder and / or rectal infiltration , an operation in the form of an exenteration is also possible in stage IV if the pelvic wall is tumor-free.

Treatment during pregnancy

In stage IA1 with complete removal of the changes by a conization , the pregnancy can be carried to term, as with CIN III, and the child can be born vaginally. A colposcopic and cytological check-up is necessary six weeks after the birth.

In stages IB to IIA, appropriate surgical treatment should be carried out in early pregnancy and the pregnancy should be terminated. If the pregnancy has already progressed further, an early birth of the child by caesarean section and subsequent radical hysterectomy with removal of the lymph nodes is advisable.

Treatment of relapse

The treatment of relapsed cervical cancer depends on the findings and the previous treatment. An operation for the central relapse, i.e. in the middle of the pelvis, is possible, usually in the sense of a radical hysterectomy after previous radiation treatment or exenteration after the uterus has already been removed . Non-pre-irradiated patients can receive radiation therapy. The value of chemoradiotherapy in relapse has not yet been finally clarified. For previously irradiated patients with pelvic wall recurrence, there are limited curative treatment approaches in special therapeutic procedures: surgical ( lateral extended endopelvic resection , LEER) and intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) or a combination of both (combined operative radiotherapy, CORT).

prevention

Primary prevention

The primary prevention consists in avoiding risk factors such as genital infections, multiple partners and smoking . Since 2006 it has been possible to vaccinate women against some of the cancer-causing HP viruses. The use of condoms and circumcision in men also reduce the risk of infection and thus the risk of cancer. Unlike other sexually transmitted diseases , which represent an additional risk factor, the condom does not offer reliable protection against infection.

vaccination

The first HPV vaccine was approved in 2006, Gardasil (quadrivalent vaccine = effective against the four HPV types 6, 11, 16 and 18) developed by Sanofi Pasteur MSD on the basis of research results from the German Cancer Research Center and the American National Institute of Health . In 2007, a bivalent vaccine (effective against the two HPV types 16 and 18) was approved in the European Union by the company GlaxoSmithKline under the trade name Cervarix . The high-risk HPV types 16 and 18 are responsible for around 70% of all cervical cancers in women worldwide. The papillomaviruses type 6 and 11 are primarily responsible for the development of genital warts (genital warts).

Both currently approved vaccines prevent the development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasms. An existing HPV infection cannot be treated or eliminated. Nor can the consequences of such an infection, such as cervical cancer or its precursors, be treated with vaccination. The preventive medical check-up for the early detection of cervical cancer ( Pap test ) is still recommended for vaccinated women, as the vaccination is only effective against some of the papillomaviruses.

According to a decision by the Federal Joint Committee in September 2018, all statutory health insurance companies in Germany will cover the costs of vaccinations for girls and boys between the ages of 9 and 17 years.

The extent to which a male vaccination has an impact on the prevention of cervical cancer has not yet been conclusively clarified. However, there is evidence of a positive influence on the prevention of HPV infections.

Circumcision of the man

A 2011 study of 18 circumcised and 39 uncircumcised Ugandan men showed that there was a negative statistical correlation between male circumcision and a woman's risk of becoming infected with HP virus. The lower rate of HPV infections appears to be due to the significant reduction in the area of the mucous membrane, which is more prone to the smallest injuries and infections than skin or thicker epithelia , such as on the glans of the penis . However, a meta-analysis from 2007 could not prove a connection after a literature analysis . However, there are doubts about the correctness of the latter study and thus also its statement.

Secondary prevention (early detection of cancer precursors)

The early detection of cervical cancer in the form of a screening examination is a so-called secondary prevention through the detection of the preliminary stages of a cancer through smear examinations ( Pap test ). In Germany, the minimum requirements for screening are regulated by law by the Federal Joint Committee . From the age of 20, women can have the examination once a year at the expense of the statutory health insurance . The cytological smear is taken with mirror adjustment, if possible under colposcopic control, from the portio surface and from the cervical canal (with a spatula or a small brush). If speculoscopy or colposcopy suggests a change in the macroscopic appearance, the smear test should be repeated closely. If the findings are repeatedly suspicious, the diagnosis should be expanded to include histological sampling.

In immunosuppressed women, it is advisable to have two early diagnosis examinations of the cervix per year, every two years with additional evidence of papilloma viruses.

The German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics , taking into account new studies in its current guideline on cervical cancer, recommends routinely performing a detection test for papilloma viruses in women over 30 years of age, even if the Pap test is normal. While the Pap test overlooks around half of the cancer cases or direct cancer precursors when carried out once, the combination of the Pap test and virus detection can detect almost all cancer precursors.

However, based on the study data currently available, the Federal Joint Committee has refused to include HPV testing as well as thin-layer cytology , a special cytological examination, in the early cancer detection program.

The screening programs for cervical cancer differ in the member states of the European Union with regard to the recommended time intervals, the age groups included and the organization of the screening.

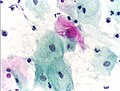

- Cytological findings and histological findings in Papanicolaou staining

In Germany, the findings are classified according to the Munich nomenclature II , while in English-speaking countries the Bethesda classification is mostly used. There is currently no internationally binding classification.

| Munich nomenclature II / Pap | Munich nomenclature II / cytological findings | recommendation | Bethesda classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. | Normal cell structure | Routine control | No evidence of intraepithelial lesion or malignancy |

| II | Clear inflammatory or degenerative changes, immature metaplasia, HPV signs without significant changes in the nucleus | Control in 1 year | No evidence of intraepithelial lesion or malignancy,

Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) (for HPV signs) |

| IIw / k

(not an official part of the Munich nomenclature II, but often used) |

Mostly inadequate smears that are not sufficient for an assessment, as well as smears with cell changes that cannot be classified as definitely abnormal, but also not as normal | Renewed smear (repeat smear = w, check smear = k) | Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US),

Minor intraepithelial lesion (with HPV signs), atypical glandular cells (AGC = Atypical glandular cells) |

| III | Severe inflammatory or degenerative change that does not allow a judgment between benign and malignant. Conspicuous gland cells that do not allow an assessment between benign and malignant; a carcinoma cannot be ruled out with certainty | Depending on the clinical findings, short-term cytological control or histological evaluation | Atypical squamous cells of unclear meaning

atypical squamous epithelial cells - higher grade intraepithelial lesions (HSIL = high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion) cannot be excluded, atypical gland cells |

| IIID | Cells of mild dysplasia or moderate dysplasia | Renewed smear examination and colposcopy in 3 months, in the case of multiple abnormal findings: histological clarification | Minor intraepithelial lesion: mild dysplasia,

higher grade intraepithelial lesion: moderate dysplasia |

| IVa | Highly altered cells, (severe) dysplasia | Renewed smear examination and colposcopy as well as histological clarification. | Higher grade intraepithelial lesion: severe dysplasia, |

| IVb | Cells of severe dysplasia or carcinoma in situ,

invasive carcinoma cannot be excluded |

Renewed smear examination and colposcopy as well as histological clarification | No equivalent |

| V | Cells of an invasive cervical cancer or other invasive tumor | Histological confirmation |

Squamous cell carcinoma , adenocarcinoma ,

other malignant neoplasm |

| 0 | Technically unusable smears (e.g. too little material or insufficient fixation) | Immediate smear control | No equivalent |

Prospect of healing

Complete spontaneous regression is possible in the precancerous stages CIN I and II. After treatment of the CIN III and carcinoma in situ, complete healing can be assumed. However, such changes may recur. The risk of this seems to be increased if HPV infection persists after conization.

The prognosis of invasive cervical cancer depends on the stage, degree of differentiation , lymph node involvement, the type of tumor and the treatment. Adenocarcinomas have a slightly worse prognosis than squamous cell carcinomas. Radiation therapy alone is also associated with a somewhat poorer prognosis compared to surgical treatment. Overall, the 5-year survival rate in Germany is around 69%, the 10-year survival rate around 65%.

| FIGO stage | 5-year survival rate in Germany |

|---|---|

| IA | approx. 93% |

| IB | approx. 92% |

| IIA | approx. 63% |

| IIB | approx. 50 % |

| III | approx. 40% |

| IV | approx. 10% |

history

In 1878 the pathologist Carl Ruge and the gynecologist Johann Veit first described cervical cancer as a disease of their own. Until then, no distinction had been made between cancer of the cervix and cancer of the uterine lining (endometrial cancer) . The German gynecologist Adolf Gusserow was the first to describe an adenocarcinoma (adenoma malignum) of the cervix in 1870. He published the findings in his work on Sarcomas of the Uterus . In 1908, the Austrian gynecologist Walther Schauenstein developed the thesis of the gradual pathogenesis of cervical cancer , which is still valid today . His work on histological examinations of atypical squamous epithelium on the portio was one of the first descriptions of surface carcinoma of the cervix.

The first removal of the uterus in cancer of the uterus by the vaginal and abdominal route was carried out in 1813 by Konrad Johann Martin Langenbeck in Kassel and in 1822 by Johann Nepomuk Sauter in Konstanz . The first scientifically based and reproducible simple removal of a cancerous uterus by means of an abdominal incision was carried out on January 30, 1878 by Wilhelm Alexander Freund in Breslau . However, the operation was still very risky at the time. On August 12, 1879, the surgeon Vincenz Czerny in Heidelberg succeeded in performing a hysterectomy through the vagina. Since the results were better than those of Freund's surgery, vaginal surgery was preferred in the period that followed.

Karl August Schuchardt carried out the first extended vaginal uterus removal in Stettin in 1893 , which was further developed in 1901 by the Viennese gynecologist Friedrich Schauta , later by Walter Stoeckel at the Charité in Berlin and Isidor Alfred Amreich in Vienna. In 1898, the Austrian gynecologist Ernst Wertheim developed a radical surgical method using an abdominal incision, which the American Joe Vincent Meigs later developed. Erich Burghardt , an Austrian gynecologist, made a significant contribution with his investigations to reduce the operative radicalism in early stages of cervical cancer, that is, to reduce the size of the operation with the same healing results. Hans Hinselmann , a German gynecologist, developed colposcopy in 1925, the first method for the early detection of cervical cancer. In 1928 the Greek doctor George Nicolas Papanicolaou developed the Pap test, another method for the early diagnosis of this tumor. Ernst Navratil , an Austrian gynecologist, made special contributions to the introduction of cytology in connection with colposcopy as an early detection method. On February 9, 1951, cervical carcinoma cells were removed from the cervix of a 31-year-old patient, which are later propagated in cell cultures and are still used for research purposes today. The cells were named HeLa cells , named after the patient . In 1971 cervical cancer screening was introduced as a program in the Federal Republic of Germany.

In 1974 Harald zur Hausen published the first reports on a possible role of papilloma viruses in cervical cancer, for which he was awarded the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine . Since the 1990s, the introduction of new surgical techniques, such as trachelectomy or total mesometrial resection of the uterus and the possibility of removing lymph nodes by means of laparoscopy , have led to greater individualization of surgical therapy for cervical cancer with partially deliberately reduced, partially improved completeness (radicality ) the surgical removal of carcinomas. The aim of this development is to avoid treatment-related problems, such as bladder or bowel problems caused by nerve damage, or the consequences of radiation therapy that has so far been common after previous surgery. In some cases, a desire to have children can even be fulfilled. In 2006, the first vaccine against some types of papillomavirus, the leading cause of cervical cancer, was approved.

literature

- Harald zur Hausen : Infections causing human cancer. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim 2006, ISBN 3-527-31056-8 .

- Manfred Kaufmann , Serban-Dan Costa , Anton Scharl (Ed.): The gynecology. 2nd, completely revised and updated edition. Springer, Berlin a. a. 2006, ISBN 3-540-25664-4 .

- Willibald Pschyrembel , Günter Strauss, Eckhard Petri (eds.): Practical gynecology. 5th, revised edition. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin a. a. 1991, ISBN 3-11-003735-1 .

- Dirk Schadendorf, Wolfgang Queißer (Ed.): Cancer early detection. General and specific aspects of secondary prevention of malignant tumors. Steinkopff, Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-7985-1392-9 .

- Heinrich Schmidt-Matthiesen , Gunther Bastert , Diethelm Wallwiener (eds.): Gynecological oncology. Diagnostics, therapy and follow-up care - based on the AGO guidelines. 7th, revised and expanded edition. Schattauer, Stuttgart a. a. 2002, ISBN 3-7945-2182-X .

- Karl-Heinrich Wulf , Heinrich Schmidt-Matthiesen, Hans Georg Bender (ed.): Clinic of gynecology and obstetrics. Volume 11: Special Gynecological Oncology. Volume 1. 4th edition. Urban and Fischer, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-437-21900-6 .

Web links

- Manual cervical cancer . ( Memento from August 13, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.03 MB) Tumor Center Munich

- 3- Guideline ' Diagnostics and Therapy of Cervical Cancer ' of the Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft e. V. and the German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics . In: AWMF online (as of 09/2014)

- 3- Guideline ' Prevention of Cervical Carcinoma' of the German Cancer Society , the German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics . In: AWMF online (as of 12/2017)

- Cervical cancer: Das Zervixkarzinom , cancer information service of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg. June 16, 2006. Last accessed September 4, 2014.

- Cervical cancer early detection: a smear provides security - early detection of cancer precursors and early treatment , Cancer Information Service of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg. May 11, 2010. Last accessed September 4, 2014.

- Information and education about cervical cancer and HPV from ZERVITA

- Information on cervical cancer from the Center for Cancer Registry Data at the Robert Koch Institute

Individual evidence

- ↑ F. Marra, K. Cloutier et al. a .: Effectiveness and cost effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccine: a systematic review. In: Pharmacoeconomics . Volume 27, Number 2, 2009, pp. 127-147, ISSN 1170-7690 . PMID 19254046 . (Review).

- ↑ Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide in 2012.Retrieved August 22, 2014

- ↑ a b c d e f g M. Streich: The cervical carcinoma: aspects relevant to practice. Prevention, diagnostics, therapy. In: Der Gynäkologe Volume 6, 2005, S, 23-25

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n 2k guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of cervical carcinoma ( memento from September 17, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) of the Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft e. V. and the German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics

- ↑ a b c M. W. Beckmann, G. Mehlhorn u. a .: Progress in therapy for primary cervical cancer (PDF) In: Dtsch Arztebl Volume 102, 2005, A-979

- ↑ V. Zylka-Menhorn: HPV vaccination: The study was extended world. In: Dtsch Arztebl Volume 106, Number 23, 2009, A-1185

- ^ German Cancer Society : New Cancer Diseases in Germany in 2004.

- ↑ a b Data on cervical cancer (cervical cancer) from the Robert Koch Institute (2014)

- ↑ JS Smith, J. Green et al. a .: Cervical cancer and use of hormonal contraceptives: a systematic review. In: Lancet. Volume 361, Number 9364, April 2003, pp. 1159-1167, ISSN 0140-6736 . PMID 12686037 . (Review).

- ↑ International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer: Cervical cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data for 16,573 women with cervical cancer and 35,509 women without cervical cancer from 24 epidemiological studies. In: Lancet. Volume 370, Number 9599, November 2007, pp. 1609-1621, ISSN 1474-547X . doi: 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (07) 61684-5 . PMID 17993361 . (Review).

- ^ A. Berrington de González, S. Sweetland, J. Green: Comparison of risk factors for squamous cell and adenocarcinomas of the cervix: a meta-analysis. In: British Journal of Cancer . Volume 90, Number 9, May 2004, pp. 1787-1791, ISSN 0007-0920 . doi: 10.1038 / sj.bjc.6601764 . PMID 15150591 . PMC 2409738 (free full text).

- ↑ CT Eckardt: A case of cervical carcinoma in a nineteen-year-old virgin. In: Arch Gynecol Obstet. Volume 30, 1887, pp. 471-478, doi: 10.1007 / BF01976292

- ^ X. Castellsagué, M. Díaz u. a .: Intrauterine device use, cervical infection with human papillomavirus, and risk of cervical cancer: a pooled analysis of 26 epidemiological studies. In: The Lancet Oncology . Volume 12, Number 11, October 2011, pp. 1023-1031, ISSN 1474-5488 . doi: 10.1016 / S1470-2045 (11) 70223-6 . PMID 21917519 .

- ↑ M. Hüsler, U. Lauper: Infect prophylaxis in pregnancy In: Gynäkologie Volume 5, 2006, pp. 6–12

- ↑ C. Sonnex, S. Strauss, JJ Gray: Detection of human papillomavirus DNA on the fingers of patients with genital warts. In: Sexually transmitted infections. Volume 75, Number 5, October 1999, pp. 317-319, ISSN 1368-4973 . PMID 10616355 . PMC 1758241 (free full text).

- ^ MA van Ham, JM Bakkers u. a .: comparison of two commercial assays for detection of human papillomavirus (HPV) in cervical scrape specimens: validation of the Roche AMPLICOR HPV test as a means to screen for HPV genotypes associated with a higher risk of cervical disorders. In: Journal of Clinical Microbiology. Volume 43, Number 6, June 2005, pp. 2662-2667, ISSN 0095-1137 . doi: 10.1128 / JCM.43.6.2662-2667.2005 . PMID 15956381 . PMC 1151918 (free full text).

- ↑ AS Kapeu, T. Luostarinen u. a .: Is smoking an independent risk factor for invasive cervical cancer? A nested case-control study within Nordic biobanks. In: American Journal of Epidemiology. Volume 169, Number 4, February 2009, pp. 480-488, ISSN 1476-6256 . doi: 10.1093 / aje / kwn354 . PMID 19074773 .

- ↑ International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer, P. Appleby et al. a .: Carcinoma of the cervix and tobacco smoking: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 13,541 women with carcinoma of the cervix and 23,017 women without carcinoma of the cervix from 23 epidemiological studies. In: International Journal of Cancer. Volume 118, Number 6, March 2006, pp. 1481-1495, ISSN 0020-7136 . doi: 10.1002 / ijc.21493 . PMID 16206285 .

- ↑ WI Al-Daraji, JH Smith: Infection and cervical neoplasia: facts and fiction. In: International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. Volume 2, Number 1, 2009, pp. 48-64, ISSN 1936-2625 . PMID 18830380 . PMC 2491386 (free full text).

- ↑ JS Smith, C. Bosetti et al. a .: Chlamydia trachomatis and invasive cervical cancer: a pooled analysis of the IARC multicentric case-control study. In: International Journal of Cancer. Volume 111, Number 3, September 2004, pp. 431-439, ISSN 0020-7136 . doi: 10.1002 / ijc.20257 . PMID 15221973 .

- ↑ a b W. Pschyrembel , G. Strauss, Eckhard Petri : Practical gynecology. 5th edition, Walter de Gruyter Verlag, 1991, 74–152, ISBN 3-11-003735-1

- ↑ O. Reich: Is the early Kohabitarche a risk factor for cervical cancer? In: Gynäkol Obstetric Rundsch Volume 45, 2005, pp. 251-256 doi: 10.1159 / 000087143

- ↑ JD Wright, K. Rosenblum et al. a .: Cervical sarcomas: an analysis of incidence and outcome. In: Gynecologic oncology. Volume 99, Number 2, November 2005, pp. 348-351, ISSN 0090-8258 . doi: 10.1016 / j.ygyno.2005.06.021 . PMID 16051326 .

- ↑ a b c H. Schmidt-Matthiesen, G. Bastert, D. Wallwiener: Gynecological oncology - diagnostics, therapy and aftercare based on the AGO guidelines. 10th edition 2002, Schattauer Verlag, 105, ISBN 3-7945-2182-X

- ↑ a b C. Wittekind (editor): TNM. Classification of malignant tumors. Eighth edition. Wiley-VCH Verlag 2017. ISBN 978-3-527-34280-8

- ↑ L.-C. Horn, K. Schierle, D. Schmidt, U. Ulrich: New TNM / FIGO staging system for cervical and endometrial carcinoma as well as malignant Müllerian mixed tumors (MMMT) of the uterus. In: obstetric women's health. Volume 69, 2009, pp. 1078-1081, doi: 10.1055 / s-0029-1240644

- ↑ L.-C. Horn, K. Schierle, D. Schmidt, U. Ulrich, A. Liebmann, C. Wittekind: Updated TNM / FIGO staging system for cervical and endometrial carcinoma and malignant mixed tumors (MMMT) of the uterus. Facts and background. In: The Pathologist. Volume 32, Number 3, May 2011, pp. 239-243, ISSN 1432-1963 . doi: 10.1007 / s00292-010-1273-6 . PMID 20084383 . (Review).

- ^ A b H. Schmidt-Matthiesen , H. Kühnle: Preneoplasias and neoplasias of the cervix uteri. In: KH Wulf, H. Schmidt-Matthiesen: Clinic for gynecology and obstetrics. Volume 11, Special Gynecological Oncology I. 3rd edition. Urban and Schwarzenberg, 1991, ISBN 3-541-15113-7 , pp. 131-206

- ↑ MS Piver, F. Rutledge, JP Smith: Five classes of extended hysterectomy for women with cervical cancer. In: Obstetrics and gynecology. Volume 44, Number 2, August 1974, pp. 265-272, ISSN 0029-7844 . PMID 4417035 .

- ↑ M. Höckel: Total Mesometrial Resection: A New Radicality Principle in the Surgical Therapy of Cervical Carcinoma. Oncologist 12: 901-907, 2006, doi: 10.1007 / s00761-006-1110-y

- ↑ Höckel M, Horn LC, Manthey N, Braumann UD, Wolf U, Teichmann G, Frauenschläger K, Dornhöfer N, Einenkel J. Resection of the embryologically defined uterovaginal (Müllerian) compartment and pelvic control in patients with cervical cancer: a prospective analysis . Lancet Oncol. 10 (7): 683-92, 2009, doi: 10.1016 / S1470-2045 (09) 70100-7 .

- ↑ M. Possover : Technical modification of the nerve-sparing laparoscopy-assisted vaginal radical hysterectomy type 3 for better reproducibility of this procedure. In: Gynecologic oncology. Volume 90, Number 2, August 2003, pp. 245-247, ISSN 0090-8258 . PMID 12893183 .

- ^ M. Possover : Options for laparoscopic surgery in cervical carcinomas. In: European Journal of Gynecological Oncology. Volume 24, Number 6, 2003, pp. 471-472, ISSN 0392-2936 . PMID 14658583 . (Review).

- ↑ D. Dargent , JL Brun et al. a .: La trachélectomie élargie (TE). An alternative à l'hystérectomie radicale dans le traitement des cancers infiltrants dévellopés sur la face extern du col utérine. In: J Obstet Gynecol Volume 2, 1994, pp. 285-292.

- ↑ Manual Cervical Carcinoma ( Memento from October 27, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF) of the Munich Tumor Center, 2004, pp. 73–77.

- ↑ a b c 2 + IDA guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and therapy of HPV infection and pre-invasive lesions of the female genitals of the German Cancer Society. V. , the German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics , the Professional Association of Gynecologists , the German Society for Pathology , the German Society for Urology , the German Cancer Society , the German STD Society and the women's self-help after cancer. In: AWMF online (as of 06/2008)

- ↑ LE Manhart, LA Koutsky: Do condoms prevent genital HPV infection, external genital warts, or cervical neoplasia? A meta-analysis. In: Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Volume 29, Number 11, November 2002, pp. 725-735, ISSN 0148-5717 . PMID 12438912 .

- ↑ GBA resolution HPV vaccination for young people becomes health insurance ( Memento from June 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) GBA resolution HPV vaccination for young people becomes health insurance

- ^ RP Insinga, EJ Dasbach u. a .: Cost-effectiveness of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in Mexico: a transmission dynamic model-based evaluation. In: Vaccine. Volume 26, Number 1, December 2007, pp. 128-139, ISSN 0264-410X . doi: 10.1016 / j.vaccine.2007.10.056 . PMID 18055075 .

- ^ DR Lowy, IH Frazer: Chapter 16: Prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines. In: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs. Number 31, 2003, pp. 111-116, ISSN 1052-6773 . PMID 12807954 . (Review).

- ↑ MJ Wawer, AA Tobian et al. a .: Effect of circumcision of HIV-negative men on transmission of human papillomavirus to HIV-negative women: a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. In: Lancet. Volume 377, Number 9761, January 2011, pp. 209-218, ISSN 1474-547X . doi: 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (10) 61967-8 . PMID 21216000 . PMC 3119044 (free full text).

- ^ X. Castellsagué, FX Bosch, N. Muñoz: The male role in cervical cancer. (PDF) In: Salud pública de México. Volume 45 Suppl 3, 2003, pp. S345-S353, ISSN 0036-3634 . PMID 14746027 .

- ^ C. Rivet: Circumcision and Cervical Cancer - Is there a link? (PDF; 87 kB) In: Canadian Family Physician .

- ↑ BY Hernandez, LR Wilkens u. a .: Circumcision and human papillomavirus infection in men: a site-specific comparison. In: The Journal of Infectious Diseases. Volume 197, Number 6, March 2008, pp. 787-794, ISSN 0022-1899 . doi: 10.1086 / 528379 . PMID 18284369 . PMC 2596734 (free full text).

- ↑ CM Nielson, MK Schiaffino et al. a .: Associations between male anogenital human papillomavirus infection and circumcision by anatomic site sampled and lifetime number of female sex partners. In: The Journal of Infectious Diseases. Volume 199, Number 1, January 2009, pp. 7-13, ISSN 0022-1899 . doi: 10.1086 / 595567 . PMID 19086813 .

- ^ RS Van Howe: Human papillomavirus and circumcision: a meta-analysis. In: The Journal of Infection. Volume 54, Number 5, May 2007, pp. 490-496, ISSN 1532-2742 . doi: 10.1016 / j.jinf.2006.08.005 . PMID 16997378 .

- ^ X. Castellsagué, G. Albero et al. a .: HPV and circumcision: a biased, inaccurate and misleading meta-analysis. In: The Journal of Infection. Volume 55, Number 1, July 2007, pp. 91-93, ISSN 1532-2742 . doi: 10.1016 / j.jinf.2007.02.009 . PMID 17433445 .

- ↑ Guidelines of the Federal Committee of Doctors and Health Insurance Companies on the early detection of cancer ("Cancer Early Detection Guidelines"). (PDF; 336 kB)

- ↑ KU Petry, D. Scheffel u. a .: Cellular immunodeficiency enhances the progression of human papillomavirus-associated cervical lesions. In: International Journal of Cancer. Volume 57, Number 6, June 1994, pp. 836-840, ISSN 0020-7136 . PMID 7911455 .

- ↑ A. Warpakowski: cervical cancer screening: When the HPV test is useful. In: Dtsch Arztebl Volume 105, 2008, A-2541 (PDF)

- ↑ Link to the guideline “Prevention, Diagnostics and Therapy…” (PDF)

- ↑ G. Ronco, P. Giorgi-Rossi et al. a .: Results at recruitment from a randomized controlled trial comparing human papillomavirus testing alone with conventional cytology as the primary cervical cancer screening test. In: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Volume 100, Number 7, April 2008, pp. 492-501, ISSN 1460-2105 . doi: 10.1093 / jnci / djn065 . PMID 18364502 .

- ↑ MH Mayrand, E. Duarte-Franco and a .: Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. In: The New England Journal of Medicine . Volume 357, Number 16, October 2007, pp. 1579-1588, ISSN 1533-4406 . doi: 10.1056 / NEJMoa071430 . PMID 17942871 .

- ↑ KU Petry, S. Menton u. a .: Inclusion of HPV testing in routine cervical cancer screening for women above 29 years in Germany: results for 8466 patients. In: British Journal of Cancer . Volume 88, Number 10, May 2003, pp. 1570-1577, ISSN 0007-0920 . doi: 10.1038 / sj.bjc.6600918 . PMID 12771924 . PMC 2377109 (free full text).

- ↑ a b c Frank W, Konta B, Peters-Engel C: PAP test for screening for cervical carcinoma (PDF; 363 kB) DAHTA @ DIMDI , 2005

- ↑ U. Schenck: finding reproduction in cytology: Munich nomenclature II and Bethesda System 1991. In: U. Schenck (ed.): Papers band of 13 training session for Clinical Cytology Munich 1995. pp 224-233.

- ↑ a b B. S. Apgar, L. Zoschnick, TC Wright: The 2001 Bethesda System terminology. In: American family physician. Volume 68, Number 10, November 2003, pp. 1992-1998, ISSN 0002-838X . PMID 14655809 . (Review).

- ↑ a b Working group “Guideline cervical smear”: Guideline for the procedure in the case of suspicious and positive cytological smear of the cervix uteri. Retrieved October 8, 2019 .

- ↑ Recommendations of ZERVITA - Information and education about cervical cancer and HPV ( Memento from January 31, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 5 kB)

- ↑ K. Bodner, B. Bodner-Adler a. a .: Is therapeutic conization sufficient to eliminate a high-risk HPV infection of the uterine cervix? A clinicopathological analysis. In: Anticancer Research . Volume 22, Number 6B, 2002 Nov-Dec, pp. 3733-3736, ISSN 0250-7005 . PMID 12552985 .

- ↑ Y. Nagai, T. Maehama et al. a .: Persistence of human papillomavirus infection after therapeutic conization for CIN 3: is it an alarm for disease recurrence? In: Gynecologic oncology. Volume 79, Number 2, November 2000, pp. 294-299, ISSN 0090-8258 . doi: 10.1006 / gyno.2000.5952 . PMID 11063660 .

- ↑ Survival C53: cervical carcinoma ( Memento from January 31, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 143 kB) of the Munich Tumor Register (2007)

- ↑ A. Gusserow: Ueber Sarcome des Uterus In: Arch Gynecol Obstet. Volume 1, 1870, pp. 240-251, doi: 10.1007 / BF01814006

- ^ WA Freund: A new method of extirpation of the whole uterus. In: Berliner Klin Wochenschrift 1878, pp. 417-418.

- ^ WA Freund: A new method of extirpation of the whole uterus. Collection of clinical lectures. In: R. Volkmann (ed.): Connection with German clinicians. Volume 41, 1878, Breitkopf und Härtel Verlag, Leipzig, pp. 911-924.

- ↑ B. Credé: A new method of extirpation of the uterus. In: Arch Gynecol Obstet. Volume 14, 1879, pp. 430-437, doi: 10.1007 / BF01690793

- ^ Spiegelberg: Another case of papillary hydropic cervical sarcoma and extirpation according to Freund. In: Arch Gynecol Obstet Volume 15, 1880, pp. 437-447, doi: 10.1007 / BF01687155

- ^ J. Zander: Milestones in Gynecology and Obstetrics. In: H. Ludwig, K. Thomsen (Eds.): Proceedings of the XIth World Congress of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Berlin, 1985. Springer Verlag, Heidelberg, 1986, pp. 3-24, ISBN 3-540-15559-7

- ^ H. Dietel: 75 years of the Northwest German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics 1909 to 1984. (PDF)

- ↑ H. Ludwig: The founding of the German Society for Gynecology (1885) ( Memento from October 16, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF) In: Frauenarzt Volume 46, 2005, pp. 928-932 (PDF; 749 kB)

- ^ M. Possover , S. Kamprath, A. Schneider: The historical development of radical vaginal operation of cervix carcinoma. In: Zentralbl Gynakol. Volume 119, 1997, pp. 353-358, PMID 9340975

- ↑ O. cheesemaker, FA Iklé: Atlas of gynecological surgery. Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgart, 1965, pp. 263-307.

- ^ T. Sharrer: HeLa Herself. In: The Scientist Volume 20, 2006, p. 22

- ^ H. zur Hausen: Papilloma viruses as cancer pathogens. ( Memento from October 15, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF) In: Obstsh Frauenheilk. Volume 58, 1998, pp. 291-296. doi: 10.1055 / s-2007-1022461