Cancer prevention

Under prevention of cancer , including cancer prevention , cancer prevention or cancer prevention called, refers to measures or rules of conduct that the development of cancers prevented or at least intended to reduce the probability of such a disease.

Some of the measures and rules of conduct that are practiced have been scientifically proven in their effectiveness by a large number of epidemiological and retrospective studies . Other cancer preventive measures are scientifically largely undisputed, but unproven. In addition, there are some measures for cancer prevention (" quackery ") that are controversially discussed in specialist circles and that are clearly rejected by evidence-based medicine .

Cancer prevention as a task for society as a whole

According to expert estimates, around half of all cancer cases in Germany can still be traced back to lifestyle factors. These included smoking, poor nutrition, little exercise, too much alcohol and UV radiation.

According to earlier surveys, 42% of all cancers and nearly half of all cancer deaths could be estimated only by the way of life (lifestyle) avoided. Cancer is not a uniform disease, but rather a collective term for a large number of related diseases , which can differ considerably in their pathology . Corresponding differences therefore also exist for the success of preventive measures. The effect of preventive measures cannot be determined on the individual alone. This always requires the largest possible, statistically recorded populations.

Cancer prevention (also: cancer early detection) is to be distinguished from cancer prevention . Their aim is to detect cancer as early as possible in order to increase the likelihood of success in treating the disease (cancer therapy).

Ways to prevent cancer

Avoiding exposure to carcinogens is one of the main approaches to cancer prevention. Another is the consumption of cancer-protective (cancer-protecting) foods or dietary supplements . Vaccinations against certain viruses ( hepatitis B and human papillomavirus ) have been shown to significantly reduce the risk of some types of cancer.

The third version of the European Code against Cancer from 2003 lists the following seven points from the area of lifestyle.

- Refrain from tobacco consumption and, if it is not possible, refrain from smoking in the presence of non-smokers

- Avoid obesity

- daily exercise

- the increased consumption of fruits and vegetables at least five times a day and the reduction of the intake of animal fats

- limiting alcohol consumption to two drinks per day for men and one for women.

- Avoid excessive sun exposure, especially in children and adolescents

- strict compliance with the regulations for handling carcinogenic or potentially carcinogenic substances

- Avoidance or reduction of contact with endocrine disruptors .

The Harvard Report on Cancer Prevention from 1996 contains an assessment of cancer risk factors that is still largely valid today. The main risk factors are in the area of individual lifestyle.

| Risk factor | Contribution to the development of cancer | organs at risk |

| Smoke | 25 to 30% | Oral cavity, esophagus, larynx, lungs, pancreas, urinary bladder, cervix, kidney and blood |

| Diet and Obesity | 20 to 40% | Oral cavity, esophagus, larynx, pancreas, stomach, intestines, breast and prostate |

| alcohol | 3% | Oral cavity, throat, esophagus, larynx and liver |

| professional factors | 4 to 8% | Lungs and bladder |

| genetic factors | 5% | Eye, intestines, breast, ovaries, and thyroid |

| Infections | 5% | Liver, cervix, lymphatic system, hematopoietic system and stomach |

| Air pollutants | 2% | lung |

Avoid exposure to carcinogenic substances and radiation

A number of substances are able to cause cancer. These carcinogens include a large number of chemical compounds in tobacco smoke , fine dust such as asbestos or diesel soot , benzene and aflatoxins (certain mold toxins). In a broader sense, this also includes ionizing radiation and oncoviruses .

Refraining from tobacco consumption

Statistically, 25 to 30% of all cancer deaths in developed countries can be attributed to long-term tobacco smoking . Between 87 and 91% of all lung cancers in men and between 57 and 86% in women are caused by smoking cigarettes . The connections between smoking and lung cancer are now well known - not least due to the corresponding warning notices on the packaging for tobacco products. For a number of other cancers, such as the group of head and neck cancer ( oral cancer , nasopharyngeal cancer , oropharyngeal cancer , throat pharyngeal cancer , laryngeal cancer and tracheal cancer ), the link between smoking and related cancer is also clearly demonstrated. In breast cancer , epidemiological data show that smoking increases the risk of disease by about 30%. Also in colorectal cancer ( "cancer") years of tobacco use increases the risk of disease significantly.

Avoiding alcohol

There are many studies that show a clear connection about the interaction between regular alcohol consumption and the increase in the risk of cancer. In breast cancer, the threshold above which alcohol consumption causes a significantly higher risk of disease is below one to two alcoholic drinks per day. The risk increases especially for estrogen receptor positive (ER +) tumors. The type of drink, whether beer , wine or spirit , as well as the color of the wine, does not matter. The risk increases in a dose-dependent manner. The daily intake of 15 to 30 g alcohol, which corresponds to about one or two alcoholic drinks, increases the risk by a factor of 1.33 (= 33%, the confidence interval for 95% probability is 1.01 to 1.71). One-time weekly consumption increases the risk by 2% per drink and weekend consumption by 4%. Excessive drinking with four to five drinks a day increases the risk by 55%.

Avoidance of excessive ultraviolet radiation

The connection between skin cancer and years of exposure of the skin to sunlight ( sunbathing to tan the skin) has been scientifically proven. Sunburns in youth in particular significantly increase the risk of skin cancer, such as malignant melanoma . Solariums and sunbeds also increase the risk of skin cancer. Protecting the skin from excessive exposure to radiation, for example by wearing appropriate clothing, can significantly reduce the likelihood of developing skin cancer.

Canceroprotective foods and dietary supplements

Food and nutrition

Epidemiological studies are available for a number of foods which suggest a canceroprotective property. These results were confirmed for many of these foods in various animal models. In many cases, however, conclusive evidence of effectiveness in humans is not available and, for several reasons, can hardly be produced. The World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) found convincing evidence (for no food convincing ) a kanzeroprotektiven effect. For some foods a 'likely canceroprotective' effect ( probable ) is seen. This includes:

- Low-starch vegetables ( e.g. broccoli , cauliflower , zucchini , kale and spinach ) with the target: mouth , pharynx , larynx , esophagus and stomach .

- Vegetables of the Leek Allium genus ( e.g. wild garlic , onion , chives and shallot ). Place of action: stomach

- Garlic . Place of action: colon and rectum

- Fruits ( e.g. cultivated apples , pears , table grapes , raspberries and bananas ). Place of action: mouth, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, lungs and stomach.

- Foods containing folates (for example, whole grains , green leafy vegetables , beetroot , broccoli , carrots , asparagus , Brussels sprouts , tomatoes , egg yolks and nuts ). Place of action: pancreas

- Foods that contain carotenoids (such as carrots, spinach, apricots, peppers, and shrimp ). Place of action: mouth, pharynx, larynx and lungs

- Foods that contain β-carotene (for example, carrots , sweet potatoes , pumpkins , apricots , spinach , broccoli and beetroot ). Place of action: esophagus

- Foods that contain lycopene (for example, tomato , rose hip, and watermelon ). Place of action: prostate

- Foods that contain ascorbic acid (vitamin C) (for example, citrus fruits , rose hips, black currants , parsley , kale, and Brussels sprouts ). Place of action: larynx

- Foods that contain selenium (such as garlic). Place of action: prostate

The Heidelberg University Clinic points to a synergism between the bioactive substances quercetin and sulforaphane against tumor stem cells of pancreatic carcinoma and lists plant-based foods in this context . These are fruits and vegetables whose importance for general cancer prevention has already been documented.

The WCRF names nine other foods or food groups with a possible canceroprotective effect ( limited suggestive ).

Some of the recommendations are very controversial as various clinical studies have produced contradicting or even contrary results. For example, the studies known so far for selenium do not provide any indication of a positive benefit from an additional dose of selenium. Some types of cancer are obviously positively influenced, but others are influenced negatively. One study (SELECT) had to be discontinued in 2008 because no protective effect could be determined compared to the placebo . There were no statistically significant differences either with selenium or with vitamin E.

A number of epidemiological studies have shown a positive effect with an increased plasma level of β-carotene and a reduced risk of developing bronchial carcinoma (lung cancer). In intervening studies (ATBC, CARET and E3N) in which smokers were given β-carotene as a dietary supplement over a longer period of time in order to reduce the risk of cancer, they unexpectedly developed lung cancer more often than the comparison group without β-carotene. In drinkers, β-carotene increases the risk of colorectal cancer. In the “normal” population, on the other hand, taking β-carotene obviously does not lead to an increased risk of cancer, but on the contrary shows the expected cancer preventive effect. In one study, for example, the risk of colon cancer decreased by 44%.

Since 2006, all drugs containing β-carotene have had to display a warning that smokers are at increased risk of developing lung cancer.

In the EPIC study carried out in ten European countries, the eating habits, body weight , height and body fat distribution of over 519,000 - healthy participants at the start of the study - have been statistically recorded since 1992 . Since then, all new cancer and other chronic diseases in this population have been recorded and compared with the respective eating habits and lifestyle of those affected. The main nutritional findings that have been gained from the study so far are:

- Increasing fiber intake lowers the risk of colon cancer. Just increasing the daily amount of fiber from 15 to 35 g reduces the risk by 40%.

- A high consumption of meat ( red meat ) increases the risk of colon cancer, while fish consumption significantly reduces this risk. For every 100 g of red meat consumed, the risk of colon cancer increases by 49%. In the case of sausage, it even increases by 70%. In contrast, consuming 100 g of fish halves the risk of this disease.

- 80 g of fruit and vegetables per day reduce the risk of mouth, throat, larynx or esophageal cancer by 9%. This effect lasts up to a threshold of 300 g per day. Larger amounts probably cannot reduce the risk of the disease even further.

- The increased consumption of butter, margarine, processed meat and fish, combined with a low consumption of bread and fruit juices, increases the risk of breast cancer.

According to an evaluation of the EPIC study published in April 2010, the influence of diet (especially the consumption of fruit and vegetables) on the risk of cancer is obviously significantly lower than previously assumed. The effects are only marginal and statistically insignificant. The authors have calculated that for every 200 g of fruit or vegetables per day, the risk of cancer decreases by only 3%. There are indications of a positive effect for some cancers, such as renal cell carcinoma, but the number of cases there is very low.

Apples and apple juice

In animal experiments developed mice and rats , where apple juice was administered up to 50% fewer tumors than the control group without the apple juice offerings. The cloudy apple juice was more effective than the filtered one in these experiments. Probably the cause here are the procyanidins , which are contained in high concentrations in cloudy apple juice. Epidemiological studies in humans have also shown that regular consumption of one or two apples a day apparently reduces the risk of lung and colon cancer.

garlic

It has been shown in model organisms that garlic can prevent the development of colon cancer. The probably effective component is diallyl disulfide .

pomegranate

The polyphenols from pomegranate juice are particularly effective against prostate cancer , as shown not only in preclinical studies, but also in studies on prostate cancer patients in whom the cancer progressed again after primary therapy (radiation, surgery). In a study, prostate cancer patients were able to keep their PSA value, the central biomarker in prostate cancer, constant four times longer than before treatment by consuming pomegranate juice (570 mg polyphenols) daily : In the six-year follow-up phase, the PSA doubling time rose from 15 to 4 to 60 months. In a double-blind and randomized study, 104 prostate cancer patients were administered pomegranate extract after unsuccessful primary therapy (PSA relapse) and the PSA doubling period was observed. The slower the PSA value (prostate-specific antigen, the most important tumor and progression marker in prostate cancer) rises, the longer the life expectancy. In the study, the participants had on average a prostate cancer of medium aggressiveness with a Gleason score of 7. Study result: By taking pomegranate extract daily for six months, the PSA value doubled from 11.9 to 18.5 months be extended. And for 50% of the participants, this time span could even be doubled compared to the starting value at the beginning of the study. The antioxidant polyphenols from fermented pomegranate juice are particularly effective.

An international team of researchers found that these pomegranate juice polyphenols can prevent breast cancer and support breast cancer therapy. This is because they inhibit the formation of the body's own estrogens and lead to a growth inhibition of 80% in the case of estrogen receptor -positive breast cancer cells - without impairing the growth of healthy cells. Fermented pomegranate juice is twice as effective as fresh juice. The polyphenols from fermented pomegranate juice also have an effect on leukemia cells: the cells either regress into healthy cells (redifferentiation) or are driven into programmed cell death (apoptosis). In addition, the polyphenols prevent new blood vessels from forming (neoangiogenesis) - this makes it difficult for the tumor to spread.

Food Supplements (NEM)

There are many food supplements in a gray area that contain certain trace elements (such as selenium ), vitamins or antioxidants with potentially carcinogenic properties. Dietary supplements are not medicines. In contrast to drugs, which have been required to prove their effectiveness in Germany since 1978 in accordance with the Drugs Act before they can be approved, this is not the case with food supplements. They are subject to the Food, Consumer Goods and Feed Code . Proof of effectiveness does not have to be provided. The WCRF recommends that the nutritional requirements are covered exclusively by food.

Food supplements are not recommended for cancer prevention, but pharmaceutical companies have recently increasingly developed and offered food supplements with cancer-preventing effects. These include well-studied phytochemicals such as flavonoids such as taxifolin or mustard oil glycosides such as glucobrassicin .

Possible mechanisms of action of secondary plant substances

Some phytochemicals have a positive effect on carcinogenesis (tumor development) immediately after consumption :

- Antioxidants are free radical scavengers and eliminate free radicals .

- Carotenoids , polyphenols and flavonoids attach to the DNA in the cell nucleus , so that no carcinogens can bind there.

- Phenolic acids , glucosinolates and sulphides inhibit certain enzymes that catalyze the conversion of procarcinogens, such as aflatoxins or nitrosamines , into carcinogens .

- In contrast, glucosinolates, monoterpenes , sulfides and polyphenols stimulate carcinogen detoxifying enzymes .

- Phenolic acids, ellagic acid , ferulic acid and caffeic acid bind to carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and detoxify them.

- Phytosterols and saponins inhibit the proliferation of tumor cells in the colon.

Overweight or obesity

The connections between overweight or obesity (obesity) and an increased risk of certain types of cancer are documented in a large number of studies.

Breast cancer

The risk of developing breast cancer in overweight or obese postmenopausal patients is 30 to 50% higher than in normal weight patients. For diseases before menopause, however, the risk is not increased. Weight loss, especially in later life, significantly reduces the risk, while increasing body weight as an adult doubles the risk of breast cancer.

Various mechanisms are discussed as an explanatory model for the increased risk of breast cancer in the case of obesity. Overweight patients often have high levels of sex hormones, which have a strong influence on tumor growth (see main article Breast cancer # Hormonal factors ). The same applies to insulin-like growth factors , especially IGF-2. The increased mass of fat storage cells in overweight patients also facilitates the storage of carcinogenic substances in adipose tissue.

Colon cancer

There is a clear correlation between the body mass index (BMI) and the risk of developing colon cancer. This is particularly the case for tumors in the distal colon. The number of facultative precancerous colon polyps also correlates with the BMI. High values for the waist-to-hip ratio also increase the risk of colorectral cancer. The two large-scale Framingham and EPIC studies come to the same conclusion .

Prostate cancer

In prostate cancer, there is also an increased risk of obesity. At around 5% on average, however, it is relatively low. One possible cause is increased insulin levels in obese patients.

Other cancers

Being severely overweight also increases the risk of renal cell carcinoma in women.

Physical activity

For the most common types of cancer, the risk of illness can be reduced through regular physical activity (sport). The biochemical mechanisms that lead to this effect are still largely unclear. Various causes are discussed. Sport reduces the risk of cancer by reducing obesity, positively influencing the hormonal balance and counteracting inflammation.

Breast cancer

Regular physical activity can reduce the risk of breast cancer by up to 50% for women. The cause of this effect is still largely unclear. Among other things, changes in the hormone levels of circulating hormones are suspected. Increased physical activity lowers the level of estrogen in the blood in women ; this both before and after menopause. In addition to the hormonal aspects, other mechanisms or confounder effects, such as a reduction in body weight and increased immunological activity, are also discussed. The acidosis observed after anaerobic exercise may play a positive role.

Colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer is one of the best-studied cancers in terms of the influence of physical activity and the likelihood of illness. Various case-control and cohort studies have shown that the risk of this type of cancer decreases with increasing exercise. There is apparently no correlation with the physical activity of the patient in cancer of the rectum . The causes of the reduction in the likelihood of colon cancer due to increased physical activity are still largely unclear. The reduced insulin and IGF-1 levels in the blood due to physical activity may be the reason for this effect.

Bronchial carcinoma

The majority of clinical studies carried out in this area come to the conclusion that physical activity can lower the risk of lung cancer. With moderate recreational sport, the risk drops by 13%, with competitive sport by 30%. This applies to both sexes, with a slightly higher positive impact in women.

The biological mechanisms that lead to a decrease in the risk of lung cancer through physical activity are largely unclear. Various possible mechanisms are discussed, including the reduced insulin, IGF, glucose and triglyceride levels as a result of physical activity and the increased levels of high-density lipoprotein . The 'training' of the immune system , which increases the number and activity of macrophages , NK cells and cytotoxic T cells through exercise , is also discussed as an explanatory model.

Preventive vaccination

- → see main article: HPV vaccine and hepatitis B

Preventive vaccination against certain oncogenic viruses , i.e. viruses with tumor-causing properties, is one of the most effective measures to avoid certain types of cancer. Infectious pathogens and mainly oncogenic viruses are held responsible for around 5% of all cancers in Germany and the United States . These include human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B and C, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8), human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1) and the Merkel cell polyoma -Virus .

Vaccination against hepatitis B virus can significantly reduce the likelihood of liver cell carcinoma (hepatocellular carcinoma, HCC for hepatocellular carcinoma ). In Asia and Africa, hepatocellular carcinoma caused by hepatitis B is one of the most common malignant tumors. In 1992 the World Health Organization asked all Member States to include hepatitis B vaccination in their national vaccination programs. This enabled the incidence of HCC to be reduced significantly in Taiwan . In 2006 the first vaccine against human papillomavirus (HPV) was approved. Infections with these viruses can cause tumors especially in the anogenital area ( anus and genitals ). HPV-induced cancers include cervical cancer (cervical cancer), vulvar cancer , penile cancer , and anal cancer . The high-risk HPV types 16 and 18 are responsible for around 70% of all cervical cancers worldwide.

The therapeutic vaccination ( cancer immunotherapy ), for example with Sipuleucel-T against prostate carcinoma, is not cancer prevention.

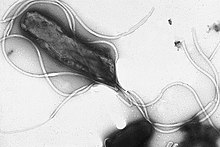

Eradication of Helicobacter pylori

→ see main article: Helicobacter pylori

The chronic infection with the rod bacterium Helicobacter pylori in the stomach is a risk factor for the development of gastric cancer and MALT lymphoma . Around half of the world's population is infected with H. pylori . Only a small fraction of these suffer from chronic gastritis , which can be the starting point for the development of gastric cancer. In total, around 500,000 people die each year from gastric cancer caused by H. pylori worldwide . The infection rate is significantly higher in developing countries than in industrialized countries. In Germany, however, around 33 million people are infected with H. pylori . The mortality from H. pylori is completely misjudged by the general public. Stomach cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide, and the vast majority of these deaths are believed to be caused by H. pylori .

The eradication of Helicobacter pylori , i.e. the complete destruction of this pathogen, is indicated according to the Maastricht guidelines of the European Helicobacter pylori Study Group (EHPSG) according to certain criteria. The therapy is usually carried out by the oral administration of two antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor . An approved vaccine is currently (2010) not yet available. If you have stomach problems, most doctors recommend therapy for the infection. The molecular biological connections between infection and carcinogenesis are still largely unclear. Some studies show a link between eating a lot of meat and the bacterial disease. Red meat in particular obviously promotes bacterial growth due to its high iron content.

Chemoprevention - medicines used to prevent cancer

The development from a normal cell to a tumor goes through various precancerous stages in which genetic changes accumulate in the cells. The aim of chemoprevention is to counteract these changes (degenerations). Synthetic substances and natural substances can be used for this. They are designed to slow down, inhibit or even reverse the precancerous processes in normal tissue or in the benign precancerous stages.

Currently (as of 2010) only the drug tamoxifen is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the prevention of breast cancer in women with an increased risk of the disease. A number of other substances are in clinical trials. These include NSAIDs ( non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs , NSAIDs) such as COX-2 inhibitors or acetylsalicylic acid ( "aspirin"). These drugs are approved for other indications , but not for chemoprevention. Studies with patients who received NSAIDs over a longer period of time - for example for the treatment of rheumatic diseases - showed a significant reduction in the risk of cancer. For breast cancer, the risk decreased by 25%, for colorectal cancer by 43%, bronchial cancer by 28% and prostate cancer by 27%. Long-term use of these drugs can be associated with significant side effects . An off-label use only in high risk patients, such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) after a ileorektalen anastomosis regarded as meaningful.

Operative cancer prevention

The prophylactic mastectomy , i.e. the preventive removal (amputation) of both breasts of a woman who has a high genetic risk ( predisposition ) of developing breast cancer, is the safest method to prevent breast cancer. The morbidity of this measure is very high. While in the United States or the Netherlands, for example, many high-risk patients opt for this form of cancer prevention, German women in the same risk group are much more reluctant. In Austria, 11 percent of high-risk patients opt for the preventive removal of both breasts.

Another operative prevention of cancer, which in high-risk patients - for example, with BRCA1 - mutation - can be carried out, the prophylactic ovariectomy , the preventive removal of both ovaries (ovarian).

The bilateral orchiectomy ( castration ) is the oldest form of therapy of prostate cancer. In principle, this intervention can also be carried out preventively. Due to the lack of testosterone, neuters can not develop prostate cancer. Due to the high morbidity, combined with psychological barriers and a lack of predispositions (no high-risk patients), bilateral orchiectomy is not used preventively.

Cancer prevention - cancer screening

The treatment of pre-cancerous tissue changes is in the border area between cancer prevention and cancer screening . For example, the removal of benign colon polyps during a colonoscopy (colonoscopy) is cancer prevention as part of a preventive examination. Colorectal carcinomas can develop from the facultative precancerous colon polyps over the years via the adenoma-carcinoma sequence . Initial studies from the Rhine-Neckar area show that colonoscopy can reduce the risk of colon cancer by up to 64 percent.

further reading

Reference books

- Harald zur Hausen and Katja Reuter: Against cancer. The story of a provocative idea , Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-498-03001-8

- DS Alberts and LM Hess: Fundamentals of Cancer Prevention. Verlag Springer, 2009, ISBN 3-540-68985-0 restricted preview in the Google book search

- HJ Senn et al: Cancer prevention. Volume 2, Verlag Springer, 2008, ISBN 3-540-69296-7 limited preview in the Google book search

- JH Bessiel: Progress in Cancer Prevention. Nova Publishers, 2008, ISBN 1-60456-327-3 limited preview in Google Book Search

- HJ Senn et al .: Tumor prevention and genetics. Volume 3, Verlag Springer, 2005, ISBN 3-540-22228-6 limited preview in the Google book search

- GA Colditz and CJ Stein: Handbook of cancer risk assessment and prevention. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2004, ISBN 0-7637-1883-1 limited preview in Google Book Search

- H. Vainio et al .: Mechanisms in carcinogenesis and cancer prevention. Verlag Springer, 2003, ISBN 3-540-43837-8 limited preview in the Google book search

- GA Colditz and DJ Hunter: Cancer prevention: the causes and prevention of cancer. Verlag Springer, 2000, ISBN 0-7923-6603-4 limited preview in the Google book search

- H. Theml: Cancer and Cancer Avoidance. Verlag CH Beck, 2005, ISBN 3-406-50880-4 limited preview in the Google book search

- H. Theml: Cancer cells do not like raspberries Anti- cancer foods. Strengthen the immune system and take targeted preventive measures. Kösel-Verlag, 2017. ISBN 978-3-466-34663-9

Regular journals on the topic of cancer prevention

- Cancer Prevention Research : monthly peer-reviewed journal of the American Association for Cancer Research

- Cancer Detection and Prevention : Bimonthly, peer-refereed journal of the International Society for Preventive Oncology

Web links

- Cancer prevention and early detection , cancer information service of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg. February 3, 2012, last accessed September 4, 2014.

- Cancer Prevention American Cancer Society (ACS)

- Cancer Prevention World Health Organization (WHO)

- Cancer Prevention National Cancer Institute (NCI)

- Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective . World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research Expert Report, 2007.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Y. M. Coyle: Lifestyle, genes, and cancer. In: Methods Mol Biol 472, 2009, pp. 25-56. PMID 19107428

- ↑ a b Islami F et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. (online) November 21, 2017

- ^ European Code Against Cancer and scientific justification. ( Memento of the original from March 25, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. July 2, 2003, accessed June 10, 2010

- ↑ Basics - Cancer Development and Metastasis: What is Cancer? , Cancer Information Service of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg. April 19, 2011, last accessed September 4, 2014

- ↑ Harvard Report on Cancer Prevention. Volume 1: Causes of human cancer. In: Cancer Causes & Control 7, 1996, pp. S3-59. PMID 9091058

- ↑ a b Heidelberg University Hospital: Cancer Prevention ( Memento from February 21, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Retrieved on June 10, 2010

- ↑ cancercode.org: Do not smoke; if you smoke, stop doing so. If you fail to stop, do not smoke in the presence of non-smokers. ( Memento of the original from April 12, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. July 2, 2003, accessed June 10, 2010

- ↑ M. Spitz: Epidemiology and risk factors for head and neck cancer. In: Semin Oncol 21, 1994, pp. 281-288. PMID 8209260

- ↑ P. Reynolds et al .: Active smoking, household passive smoking, and breast cancer: evidence from the California Teachers Study. In: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 96, 2004, pp. 29-37. PMID 14709736

- ↑ C. Nagata et al.: Tobacco smoking and breast cancer risk: an evaluation based on a systematic review of epidemiological evidence among the Japanese population. In: Jpn J Clin Oncol 36, 2006, pp. 387-394. PMID 16766567

- ^ E. Botteri et al.: Smoking and colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. In: JAMA 300, 2008, pp. 276-2778. PMID 19088354

- ^ PS Liang et al.: Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. In: Int J Cancer 124, 2009, pp. 2406-2415. PMID 19142968 (Review)

- ↑ H. Nisa et al .: Cigarette smoking, genetic polymorphisms and colorectal cancer risk: the Fukuoka Colorectal Cancer Study. (PDF; 852 kB) In: BMC Cancer 10, 2010, 274. doi: 10.1186 / 1471-2407-10-274 ( Open Access )

- ↑ Y. Li et al: Wine, liquor, beer and risk of breast cancer in a large population. In: Eur J Cancer 45, 2009, pp. 843-850. PMID 19095438

- ^ A b N. Khan et al .: Lifestyle as risk factor for cancer: Evidence from human studies. In: Cancer Lett 293, 2010, pp. 133-143. PMID 20080335 (Review)

- ↑ LS Morch include: Alcohol drinking, consumption patterns and breast cancer among Danish nurses: a cohort study. In: Eur J Public Health 17, 2007, pp. 624-629. PMID 17442702

- ↑ SA Oliveria et al .: Sun exposure and risk of melanoma. In: Arch Dis Child 91, 2006, pp. 131-138. PMID 16326797 , PMC 2082713 (free full text) (Review)

- ↑ Further bioactive substances against tumor stem cells.

- ^ A b c World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research: Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer. 2nd edition, 2007, ISBN 0-9722522-2-3 , pp. 93-94.

- ↑ SM Lippman et al .: Effect of Selenium and Vitamin E on Risk of Prostate Cancer and Other Cancers. The Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). In: JAMA 301, 2009, pp. 39-51. PMID 19066370

- ↑ The Effect of Vitamin E and Beta Carotene on the Incidence of Lung Cancer and Other Cancers in Male Smokers , in: NEJM 330, 1994, pp. 330-335. PMID 8127329

- ^ R. Goralczyk: Beta-carotene and lung cancer in smokers: review of hypotheses and status of research. In: Nutr Cancer 61, 2009, pp. 767-774. PMID 20155614 (Review)

- ↑ S. Offermann: β-carotene increases the risk of colon cancer in smokers and drinkers. In: Image of Science. May 21, 2003, accessed September 8, 2019 .

- ↑ dife.de: EPIC Potsdam study. ( Memento of the original from March 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved June 11, 2010

- ↑ S. Schelosky Less colon cancer through more fiber. ( Memento of the original from March 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. DIfE press release 2/2003, dated May 3, 2003

- ↑ Meat increases, fish lowers the risk of colon cancer. ( Memento of the original from March 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. DIfE press release 9/2005, dated June 14, 2005

- ↑ Relationship between fruit and vegetable consumption and cancer of the upper digestive tract - New results from the EPIC study. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. DIfE press release 12/2006 of July 20, 2006

- ↑ Certain diets can be linked to an increased risk of breast cancer. ( Memento of the original from January 6, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. DIfE press release of August 28, 2008

- ↑ P. Boffetta: Fruit and Vegetable Intake and Overall Cancer Risk in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). ( Memento of the original from August 19, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: J Natl Cancer Inst 102, 2010, pp. 529-537. doi: 10.1093 / jnci / djq072 PMID 20371762

- ↑ Fruit and vegetables (hardly) protect against cancer. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt from April 7, 2010

- ^ WC Willett: Fruits, vegetables, and cancer prevention: turmoil in the produce section. In: J Natl Cancer Inst 102, 2010, pp. 510-511. PMID 20371763

- ^ TC Koch et al.: Prevention of colon carcinogenesis by apple juice in vivo: impact of juice constituents and obesity. In: Mol Nutr Food Res 53, 2009, pp. 1289-1302. PMID 19753605 (Review)

- ↑ C. Fähndrich: Effect of apple juice on colon carcinogenesis and its modulation by growth factors in animal experiments. Dissertation, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, 2005

- ↑ M. Fix: "An Apple A Day" - why apples never get cancer. (PDF; 3.6 MB) In: Insight 1, 2009, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ C. Gerhauser: Cancer chemopreventive potential of apples apple, juice, and apple components. In: Planta Med 74, 2008, pp. 1608-1624. PMID 18855307 (Review)

- ↑ JA Milner: Preclinical perspectives on garlic and cancer. In: J Nutr 136, 2006, pp. 827S-831S. PMID 16484574

- ↑ JS Yang et al: Diallyl disulfide inhibits WEHI-3 leukemia cells in vivo. In: Anticancer Res 26, 2006, pp. 219-225. PMID 16475702

- ↑ JA Milner: A historical perspective on garlic and cancer. In: J Nutr 131, 2001, pp. 1027S-1031S. PMID 11238810

- ↑ Lansky EP et al .: Possible synergistic prostate cancer suppression by anatomically discrete pomegranate fractions Investigational New Drugs . (2005) 7: 13-18. PMID 15528976

- ↑ Lansky EP et al .: Pomegranate (Punica granatum) pure chemicals show possible synergistic inhibition of human PC-3 prostate cancer cell invasion across Matrigel Investigational New Drugs. (2005) 23: 121-122. PMID 15744587

- ↑ Pantuck AJ et al .: Long term follow up of phase 2 study of pomegranate juice for men with prostate cancer shows durable prolongation of PSA doubling time In: The Journal of Urology . (2009) 181: 295.

- ↑ Paller CJ et al .: A phase II study of pomegranate extract for men with rising prostate-specific antigen following primary therapy ASCO Annual Meeting 2011, Poster Discussion Session

- ↑ Lansky EP et al .: Pomegranate (Punica granatum) pure chemicals show possible synergistic inhibition of human PC-3 prostate cancer cell invasion across Matrigel Investigational New Drugs. (2005) 23: 121-122. PMID 15744587

- ↑ Kim ND et al .: Chemopreventive and adjuvant therapeutic potential of pomegranate (Punica granatum) for human breast cancer Breast Cancer Res Treat . (2002) 71 (3): 203-17. PMID 12002340

- ↑ Kawaii S & Lansky EP: Differentiation-promoting activity of pomegranate (Punica granatum) fruit extracts in HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells Journal of Medicinal Food. (2004) 7: 13-18. PMID 15117547

- ↑ Federal Institute for Risk Assessment : Dietary Supplements. Retrieved February 25, 2010

- ↑ Vitamins, trace elements and cancer: (Not) a plus for health? , Cancer Information Service of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg. Dated November 3, 2011. Retrieved September 4, 2014

- ↑ Focus September 17, 2010 Plant matter conquers health market ( Memento from October 21, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Pressetext.de August 14, 2006

- ↑ C. Müller: How food can protect. ( Memento of July 5, 2004 in the Internet Archive ) In: UGB-Forum 1, 1999, pp. 14-17.

- ↑ a b C. M. Friedenreich: Review of anthropometric factors and breast cancer risk. In: Eur J Cancer Prev 10, 2001, pp. 15-32. PMID 11263588 (Review)

- ↑ a b Weight control and physical activity. In: IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Cancer-Preventive Agents. World Health Organization and IARC (editors), Volume 6, IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention, 2002, ISBN 92-832-3006-X

- ↑ MC Boutron-Rualt et al .: Energy intake, body mass index, physical activity and the colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. In: Nutr Cancer 39, 2001, pp. 50-57. PMID 11588902

- ^ AI Neugut et al.: Obesity and colorectal adenomatous polyps. In: J Natl Cancer Inst 83, 1991, pp 359-361. PMID 1995919

- ↑ K. Shinchi et al: Obesity and adenomatous polyps of the sigmoid colon. In: Jpn J Cancer Res 85, 1994, pp. 479-484. PMID 8014105

- ↑ AL Davidow et al: Recurrent adenomatous polyps and body mass index. In: Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 5, 1996, pp. 313-315. PMID 8722224

- ↑ E. Giovannucci include: Physical activity, obesity and risk of colorectal adenoma in women (United States). In: Cancer Causes Control 7, 1996, pp. 253-263. PMID 8740738

- ↑ CL Bird et al .: Obesity, weight gain, large weight changes and adenomatous polyps of the left colon and rectum. In: Am J Epidemiol 147, 1998, pp. 670-680. PMID 9554606

- ↑ S. Kono et al: Obesity, weight gain and risk of colon adenomas in Japanese men. In: Jpn J cancer Res 90, 1999, pp. 801-811. PMID 10543250

- ↑ A. Lukanova et al.: Body mass index and cancer. Results from the northern Sweden health and disease cohort. In: Int J Cancer 118, 2006, pp. 458-466. PMID 16049963

- ^ RJ MacInnis et al: Body size and composition and colon cancer risk in men. In: Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13, 2004, pp. 553-559. PMID 15066919

- ^ RJ MacInnis et al: Body size and composition and colon cancer risk in men. In: Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13, 2004, pp. 553-559. PMID 15066919

- ↑ LL Moore et al .: BMI and waist circumference as predictors of lifetime colon cancer risk in Framingham Study adults. In: Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 28, 2004, pp. 559-567. PMID 14770200

- ↑ T. Pischon et al .: Body size and risk of colon and rectal cancer in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC). In: J Natl Cancer Inst 98, 2006, pp. 920-931.

- ↑ Body measurements and colon cancer risk - New results from the EPIC study. ( Memento of the original from September 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. DIfE press release 11/2006, dated July 5, 2006

- ^ RJ MacInnis and DR English: Body size and composition and prostate cancer risk, systematic review and meta-regression analysis. In: Cancer Causes Control 17, 2006, pp. 989-1003. PMID 16933050

- ^ ME Wright et al: Prospective study of adiposity and weight change in relation to prostate cancer incidence and mortality. In: Cancer 109, 2007, pp. 675-684. PMID 17211863

- ^ AW Hsing et al.: Prostate cancer risk and serum levels of insulin and leptin, a population based study. In: J Natl Cancer Inst 93, 2001, pp. 783-789. PMID 11353789

- ↑ CS Mantzoros et al .: Insulin-like growth factor 1 in relation to prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. In: Br J Cancer 76, 1997, pp. 1115-1118. PMID 9365156 , PMC 2228109 (free full text)

- ↑ New results from the EPIC study: being very overweight increases the risk of kidney cancer in women. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. DIfE press release 12/2005, dated August 14, 2005

- ^ A b F. Schubert: Many cancer cases are preventable: How to protect yourself. (PDF; 3.9 MB) In: Einblick German Cancer Research Center (Ed.), 1, 2010, pp. 21–24.

- ↑ a b K. Smallbne et al .: Episodic, transient systemic acidosis delays evolution of the malignant phenotype: Possible mechanism for cancer prevention by increased physical activity. In: Biology Direct 5, 2010, 22. doi: 10.1186 / 1745-6150-5-22 PMID 20406440 ( Open Access )

- ^ J. Kruk: Lifetime physical activity and the risk of breast cancer: a case-control study. In: Cancer Detect Prev 31, 2007, pp. 18-28. PMID 17296272

- ↑ G. Jasienska et al .: Habitual physical activity and estradiol levels in women of reproductive age. In: Eur J Cancer Prev 15, 2006, pp. 439-445. PMID 16912573

- ↑ A. McTiernan et al .: Effect of exercise on serum estrogens in postmenopausal women, a 12-month randomized trial. In: Cancer Res 64, 2004, pp. 2923-2928. PMID 15087413

- ^ SR Cummings et al.: Prevention of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: approaches to estimating and reducing risk. In: J Natl Cancer Inst 101, 2009, pp. 384-398. PMID 19276457 PMC 2720698 (free full text)

- ↑ JA Cauley et al: The epidemiology of serum sex hormones in postmenopausal women. In: Am J Epidemiol 129, 1989, pp. 1120-1131. PMID 2729251

- ^ ME Nelson et al: Hormone and bone mineral status in endurancetrained and sedentary postmenopausal women. In: J Clin Endocrinol Metab 66, 1988, pp. 927-933. PMID 3360900

- ↑ CM Friedenreich and MR Orenstein: Physical activity and cancer prevention: etiologic evidence and biological mechanisms. In: J Nutr 132, 2002, pp. 3456S-3464S. PMID 12421870

- ^ S. Suzuki et al.: Effect of physical activity on breast cancer risk: findings of the Japan collaborative cohort study. In: Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17, 2008, pp. 3396-3401. PMID 19029398

- ↑ L. Bernstein et al .: Physical exercise and reduced risk of breast cancer in young women. In: J Natl Cancer Inst 86, 1994, pp. 1403-1408. PMID 8072034

- ^ M. Slattery: Physical activity and colorectal cancer. In: Sports Med 34, 2004, pp. 239-252. PMID 15049716

- ^ M. Slattery: Physical activity and colorectal cancer. In: Am J Epidemiol 158, 2003, pp. 214-224. PMID 12882943

- ↑ BA Calton et al .: Physical activity and the risk of colon cancer among women, a prospective cohort study (United States). In: Int J Cancer 119, 2006, pp. 385-291. PMID 16489545

- ^ SC Larsson et al: Physical activity, obesity and risk of colon and rectal cancer in a cohort of Swedish men. In: Eur J Cancer 42, 2006, pp. 2590-2597. PMID 16914307

- ↑ C. Friedenreich et al .: Physical activity and risk of colon and rectal cancers, the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. In: Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15, 2006, pp. 2398-2407. PMID 17164362

- ↑ KJ Lee et al: Physical activity and risk of colorectal cancer in Japanese men and women, the Japan Public Health Center-based prospective study. In: Cancer Causes Control 18, 2007, pp. 199-209. PMID 17206529

- ↑ R. Kaaks et al .: Serum C-peptide, insulin-like growth factor (IGF) -I, IGF-binding proteins, and colorectal cancer risk in women. In: J Natl Cancer Inst 92, 2000, pp. 1592-1600. PMID 11018095

- ↑ J. Ma et al .: Prospective study of colorectal cancer risk in men and plasma levels of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) -I and IGF-binding proteins-3. In: J Natl Cancer Inst 91, 1999, pp. 620-625. PMID 10203281

- ^ P. Sinner et al .: The association of physical activity with lung cancer incidence in a cohort of older women. The Iowa women's health study. In: Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15, 2006, pp. 2359-2363. PMID 17164357

- ↑ CM Alfano et al .: Physical activity in relation to all-site and lung cancer incidence and mortality in current and former smokers. In: Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13, 2004, pp. 2233-2241. PMID 15598785

- ↑ H. Bak et al .: Physical activity and risk for lung cancer in a Danish cohort. In: Int J Cancer 116, 2005, pp. 439-445. PMID 15800940

- ↑ K. Steindorf et al .: Physical activity and lung cancer risk in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition cohort. In: Int J Cancer 119, 2006, pp. 2389-2397. PMID 16894558

- ↑ CM Friedenreich: Physical activity and cancer prevention: from observacional to intervention research. In: Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 10, 2001, pp. 287-301. PMID 11319168

- ^ R. Ballard-Barbash et al: Physical activity across the cancer continuum: review of existing knowledge and innovative designs for future research. In: Cancer 95, 2002, pp. 1134-1143. PMID 12209701

- ↑ JA Woods et al .: Effects of the exercise on the immune response to cancer. In: Med Sci Sports Exerc. 26, 1994, pp. 1109-1115. PMID 7808244

- ↑ JA Woods et al .: Exercise and cellular innate immune function. In: Med Sci Sports Exerc 31, 1999, pp. 57-66. PMID 9927011

- ^ BK Pedersen et al.: NK cell response to physical activity: possible mechanism of action. In: Med Sci Sports Exerc 26, 1994, pp. 140-146. PMID 8164530

- ^ A. Nomura et al .: Prospective study of pulmonary function and lung cancer. In: Am Rev Respir Dis 144, 1991, pp. 307-311. PMID 1859052

- ↑ A. Tardon include: Leisure-time physical activity and lung cancer, a meta-analysis. In: Cancer Causes Control 16, 2005, pp. 389-397. PMID 15953981 , PMC 1255936 (free full text)

- ↑ krebsatlas.de: Infectious pathogens. ( Memento of the original from July 31, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. November 6, 2007, accessed February 27, 2010

- ↑ who.int: New and Under-utilized Vaccines Implementation (NUVI): Hepatitis B. Accessed June 11, 2010

- ↑ MG Chang et al: Decreased Incidence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Hepatitis B Vaccinees: A 20-Year Follow-up Study. In: J Natl Cancer Inst 101, 2009, pp. 1348-1355. PMID 19759364

- ↑ MH Chang: Cancer prevention by vaccination against hepatitis B. In: Recent Results Cancer Res 181, 2009, pp. 85-94. PMID 19213561

- ^ YH and DS Chen: Hepatitis B vaccination in children: The Taiwan experience. In: Pathol Biol (Paris) 2010 [Epub ahead of print] PMID 20116181

- ↑ ML Gillison et al. a .: HPV prophylactic vaccines and the potential prevention of noncervical cancers in both men and women. In: Cancer 113, 2008, pp. 3036-3046. doi: 10.1002 / cncr.23764 PMID 18980286 (Review)

- ↑ J. Torrs et al.: A comprehensive review of the natural history of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. In: Arch Med Res 31, 2000, pp. 431-469. PMID 11179581 (Review)

- ↑ Helicobacter pylori. In: ZCT 1, 2008

- ↑ C. Pfaff: gastric germ Helicobacter pylori for the development of gastric cancer more important than assumed. In: Bild der Wissenschaft (Online) from September 13, 2003

- ↑ P. Malfertheiner et al .: Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection - The Maastricht 2-2000 Consensus Report. ( Memento of the original from August 6, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 322 kB) In: Aliment Pharmacol Ther 16, 2002, pp. 167-180. PMID 11860399

- ↑ P. Malfertheiner et al .: Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. In: Gut 56, 2007, pp. 772–781. PMID 17170018 , PMC 1954853 (free full text)

- ↑ Risk factors and triggers: How does stomach cancer develop? March 30, 2006. Retrieved June 11, 2010

- ↑ C. Gerhäuser: Chemoprevention of cancer. ( Memento of the original from September 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 1.0 MB) In: Forum DKG 4, 2007, pp. 5–9.

- ↑ J. Cuzick include: Overview of the main outcomes in breast cancer prevention trials. In: The Lancet 361, 2003, pp. 296-300. PMID 12559863

- ↑ GA Doherty and FE Murray: Cyclooxygenase as a target for chemoprevention in colorectal cancer: lost cause or a concept coming of age? In: Expert Opin Ther Targets 13, 2009, pp. 209-218. PMID 19236238 (Review)

- ^ DA Corley et al.: Protective association of aspirin / NSAIDs and esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. In: Gastroenterology 124, 2003, pp. 47-56. PMID 12512029 (Review)

- ↑ JA Baron: Epidemiology of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cancer. In: Prog Exp Tumor Res 37, 2003, pp. 1-24. PMID 12795046 (Review)

- ^ WH Wang et al.: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and the risk of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. In: J Natl Cancer Inst 95, 2003, pp. 1784-1791. PMID 14652240 (Review)

- ↑ RE Harris: Inflammopharmacology. 17, 2009, pp. 55-67. PMID 19340409 (Review)

- ^ T. Gottstein and H. Koop: Prevention of gastrointestinal tumors. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 1.4 MB) In: Forum DKG 2/2004 pp. 40–45.

- ↑ H. Meijers-Heiboer et al .: Breast cancer after prophylactic bilateral mastectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. In: N Engl J Med 345, 2001, pp. 159-164. PMID 11463009

- ↑ LC Hartmann et al .: Efficacy of Bilateral Prophylactic Mastectomy in Women with a Family History of Breast Cancer. In: N Engl J Med 340, 1999, pp. 77-84. PMID 9887158

- ↑ K. Kast et al.: Clinical management of familial breast cancer - a coverage study of the health insurance companies. In: Ärzteblatt Sachsen 2, 2006, pp. 73–76.

- ^ Prophylactic mastectomy. ( Memento of the original from October 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Ärztewoche Online 18, 2004

- ↑ KA Metcalfe: Oophorectomy for breast cancer prevention in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. In: Womens Health (Lond Engl) 5, 2009, pp. 63-68. PMID 19102642 (Review)

- ↑ A. Russo et al.: Hereditary ovarian cancer. In: Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 69, 2009, pp. 28-44. PMID 18656380 (Review)

- ↑ RB Then, among other things: Strategies for ovarian cancer prevention. In: Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 34, 2007, pp. 667-686. PMID 18061863 (Review)

- ↑ Cancer information service of the DKFZ: Prostate cancer, therapy method: hormonal therapy. dated July 31, 2008, accessed June 13, 2010

- ^ About Cancer Prevention Research. Retrieved June 10, 2010

- ^ International Society for Preventive Oncology. Retrieved June 10, 2010