Salmon argument

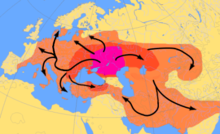

Linguists in the 19th and 20th centuries saw the salmon argument as proof that the original home of the Indo-Europeans was in northern Central Europe and not in the Eurasian steppe. It was based on the discovery that the very similar names for salmon in Germanic , Baltic and Slavic languages were rooted in a proto-Indo-European word.

The salmon argument was: The original Indo-Europeans come from where both the salmon and the common word for it occur. This only applied to the area of the Central European rivers to the Baltic Sea .

However, this derivation was based on a false assumption. The name of the original Indo-Europeans (today also: Proto-Indo-Europeans) did not initially apply to salmon ( Salmo salar ), but to subspecies of salmon or sea trout ( Salmo trutta trutta ), which are common in the rivers to the Black and Caspian Seas . In more than 100 years, around thirty scholars contributed to the salmon argument until it was refuted.

Emergence

"Salmon" in early linguistics

From the mid-19th century, philologists studied words that were similar in several Indo-European languages . They were considered to be "primordial", either as primordial Indo-European or belonging to a younger original language of the "Litu-Slawo-Germanic". Meant were the terms for sea, lion, salt or beech . The presence or absence of common words should allow conclusions to be drawn about the original home of the Indo-Europeans. The numerous hypotheses about their geographical location in northern Europe , southern Russia or the Balkans also included racial anthropological and national- chauvinistic reasons.

The comparison of languages indicated a lack of Indo-European fish names. Even a uniform Indo-European word for fish , piscis in Latin , mátsya- in Sanskrit , ichthýs in Greek and ryba in Old Slavonic , was apparently missing. Both made an origin of the Indo-Europeans from a fish-poor Eurasian steppe - or forest area plausible.

For salmon ( Salmo salar ), however, the reference works that have appeared since the 1870s contain increasingly extensive compilations of similar names in the Germanic, Baltic and Slavic languages. Their forms precluded borrowing . In 1876, the German Germanist August Fick led the series of Lithuanian lászis, lasziszas , Latvian lassis, lassens , Old Prussian lasasso , Polish łosoś and Russian losós ′ to Old Norse lax , Old High German lahs and New High German salmon . With the German dictionary of the Brothers Grimm , Old English leax was added in 1877 . The philologist Friedrich Kluge also called Scottish lax in 1882 and constructed a Gothic form * lahs .

First mention of the salmon argument

For the first time in 1883 the linguistic historian Otto Schrader delimited the location of the “Slavo-Germanenland” with an animal-geographic argument. The decisive factor is the naming of the salmon, "which, according to Brehm's animal life, only occurs in the rivers of the Baltic Sea, North Sea and the northern Arctic Sea." This seemed to have found a word about which the scholars were in agreement about the factually and linguistically almost identical distribution area. Because Schrader saw the salmon argument as limited to the West Indo-European languages, he considered it unsuitable in the discussion about the original home.

The racial anthropologist Karl Penka , who considered southern Scandinavia to be the home of the Indo-Europeans, wrote about the salmon in 1886 without any evidence: “This fish was known to the Aryan indigenous people .” Penka formally expanded the salmon argument to include the lack of salmon words: “Now the salmon is found ( Salmo salar), whose home is the Arctic Ocean and the northern parts of the Atlantic Ocean, only in the streams and rivers of Russia, which flow into the Baltic Sea and the White Sea, but by no means in the rivers that merge into the Black or Caspian Pour the sea. Nor does it occur in the rivers of Asia and in the Mediterranean Sea, which explains why no corresponding sound forms of Urarian * lakhasa have been preserved in Iranian and Indian, nor in Greek and Latin. ”Penka did not justify its reconstructed form * lakhasa .

"[The salmon words] are limited to a narrower linguistic area," Schrader replied in 1890. The linguist Johannes Schmidt also used the lack of salmon words in all other Indo-European languages against Penka: This used the northern European designation of salmon as Indo-European to the To prove the correspondence between the Indo-European and southern Swedish fauna. In 1901, however, Schrader took up Penka's formulation ex negativo : "Since the fish occurs only in those rivers which flow into the ocean and the Baltic Sea, but not in those which flow into the Mediterranean or Black Sea, it is understandable, that neither Greeks nor Romans had a peculiar name for it. "

The first editions of Kluge's Etymological Dictionary of the German Language trace the conceptual clarification. From the 1st edition in 1883 to the 5th edition in 1896, the Germanic and contemporary so-called “Slavic-Lithuanian” salmon words were designated as “originally related”. From the 6th edition in 1899 to the 8th edition completed in 1914, they were considered "related".

The early debate about the salmon argument and original home

In the 30 years after the first mention, both proponents of the northern European hypothesis and representatives of the steppe origin used the salmon argument to determine the location of the original home. The former dated a common starting word for "salmon" to the Ur-Indo-European period of the common language, the latter to a more recent, single-language phase with a West Indo-European, Germanic-Baltic-Slavic new coinage. A linguistic debate about the ancient or West Indo-European ancestral forms of the salmon words was not conducted. Tree and mammal names , terms from agriculture and cattle breeding, archaeological finds and comparisons of skulls were decisive for the Indo-European discussion of this time . The salmon argument was of secondary importance because its potential for knowledge seemed exhausted.

extension

Tocharian B "laks"

In 1908, philologists identified an extinct language in the Central Asian Tarim Basin in what is now northwestern China as Indo-European and published the first translations. The text fragments derived predominantly from the second half of the first millennium and were written in two language variants later Tocharian A and B were called. Schrader was the first to point out a new salmon word in 1911, even before a translation with this word had appeared: “But now a Tocharian laks 'fish' has also appeared recently , and it will therefore depend on future clarifications about this language whether with these Words in this context are to be used or not. ”Schrader was not yet ready to draw any conclusions from the discovery.

The discovery of Tocharian B laks "fish" proved the Indo-European character of the salmon word. Supporters of the hypothesis of the northern European original homeland saw themselves confirmed. The Indo-Europeanist Hermann Hirt wrote: "It is therefore an allegation made by O. Schrader and others, which has been refuted by the facts, that the Indo-Europeans did not pay attention to fish." Because of the introduction of agriculture and cattle breeding, it was "understandable for the Balticist Franz Specht , that in general only very prominent fish species, which must have been more widespread, can be identified as common Indo-European names. "The Celtologist Julius Pokorny concludes from the lack of salmon east of the Urals:" The Tocharians are therefore likely to come from Central or Northern Europe "The word" leads us to assume that the Tocharers originally sat on a salmon-bearing river in the vicinity of the Slavs. "The Finno-Ugric language area , in which the salmon words came from Indo-European, was excluded . Nor did the parts of Europe later settled by Indo-Europeans come into consideration, in which the salmon words came from designations rooted in pre-Indo-European such as salmo and esox, i.e. west of the Elbe, in the Mediterranean region and on the British Isles. The original name, according to John Loewenthal , "probably came up in the Oder and Vistula source areas."

The salmon argument made it possible to equate the Indo-European with the Germanic settlement areas propagated by the national anthropologists and the National Socialists and the settlement of the "primitive ethnic race" in Greater Germany . Loewenthal wrote in 1927: “The Germanic peoples [...] are real Indo-Europeans. They are the only species and ethnicity that have been preserved in their purity [...] They are likely [...] advancing from the sources of the Vistula and Oder over the Danish islands to Skåne , from Skåne to have begun their historical work. ”In the Festschrift für Hirt, the editor notes that Hirt let "the apparent basic race of the Indo-Europeans find their optimal living conditions in a northern climate". The Germanist Alfred Götze , who was close to National Socialism, was an exception , who regarded the salmon word beyond West Indo-European as “further attempts at connection and interpretation” to be “not secured” .

In 1951, the Austrian archaeologist Robert Heine-Geldern's suggestion that Germanic tribes might have taken part in the eastward migration of the Tocharians and thus induced the adoption of Germanic loanwords into the Tocharian language met with a strong, mostly negative reaction , because he overlooked the fact that the Germans were more likely to be theirs Word * fisk "fish" would have passed. The Germanist Willy Krogmann found Heine-Geldern's "idea [...] without any support." The American Asian scientist Denis Sinor commented on it as "good archaeological evidence to shed light on events that, in my opinion, do not shed light on this discipline can. "

Ossetian "læsæg"

The next salmon word was discovered by a linguist in the Digorian dialect of the Ossetian language , which belongs to the Iranian branch of Indo-European and is spoken in the Caucasus . Recorded lexically for the first time in 1929, for the Norwegian Indo-Iranian Georg Morgenstierne in 1934 it “could hardly be a loan word from Russian losoś .” Morgenstierne pointed out that salmon species occur in Caucasian rivers, the Indologist Sten Konow noted the relationship with the Tocharian fish word.

The indologist Paul Thieme led læsæg back as diminutive to the Indo-Aryan migration: "Of course it may be occurring in the Caucasian in rivers, Salmo 'not the Salmo salar act, but only a trout that are the order of their similarity with that of former home still known * lakso- 'Salmo salar' for the sake of appropriately named with the deminutive * laksoqo 'smile, little salmon'. "

Krogmann recognized “a completely wrong idea” of the sea trout Salmo trutta caspius , which rises from the Caspian Sea into the Terek , which flows through the Ossetian settlement area with its tributaries . This "Caspian salmon" is the largest of the European salmonids and is widespread in southern Russia as far as the Urals. “Fish weighing more than 40 kilograms are not uncommon. [...] It would be conceivable that the name was initially created for a species of a different genus and only later applied to the Salmo salar L. , when you got to know a similar fish in it. ”In 1960, Krogmann was on the verge of conquering it of the salmon argument, but did not pursue the idea further.

Old Indian "* lākṣa", "lakṣā", "lakṣá"

Among the linguists, Thieme made the last great effort to explain the Indo-European original home with the salmon argument. He presented three ancient Indian salmon words in which the meaning of the original home still shines : to lākṣā "red lacquer " an adjective * lākṣa "salmon, red" because of the reddish salmon meat, the numeral lakṣā "100,000", initially "immense amount" because of the large flocks of salmon at spawning time, as well as the noun lakṣá " stake ", which could initially have been used among fishermen for a valuable lot of the catch. Thus, "the fact of a common Indo-European acquaintance with Salmo salar for the place of the Indo-European language community before the Aryans emigrated to the area of the Baltic Sea and Elbe."

“The bold assumption does not seem sustainable enough for such weighty conclusions”, commented the Indo-Europeanist Walter Porzig , who, however, continued to follow the Baltic Sea hypothesis. With the consent of his specialist colleagues, Manfred Mayrhofer traced the etymology of lākṣā “red lacquer” back to the Indo-European color designation * reg- “dyed, reddened ” and praised Thieme for his “wealth of ideas […] and always ingenious etymologies.” As the origin of lakṣá The Indo-European root * legh “to place ” comes into consideration, which suggests an original meaning “deposit” for lakṣá .

|

|

The ancient Egyptian tadpole hieroglyph Ḥfn "100,000", as an animal number, a parallel to the ancient Indian लक्ष lakṣā "100,000" |

Thiemes number word theory with लक्ष lakṣā "100,000" met with more approval , mostly because of the parallels in other languages. In ancient Egyptian , "100,000" is denoted by the hieroglyph of the tadpole , in Chinese the character for ant also means "10,000", in Semitic the word for cattle also means "1000". The linguistic connection remained unclear. Kluge led the reference to the numeral up to the 21st edition (1975), most recently "without etymological certainty" .

Armenian "losdi", Romansh "* locca"

After the discovery of the salmon words in Tocharian and Ossetian, the ascription of further names no longer meant a new quality in the debate about the salmon argument. Armenian losdi "salmon", first included in a dictionary in 1929, joined the salmon group in 1963. In 1976, the American anthropologist A. Richard Diebold, Jr. took up the "Romanesque" ( late folk Latin-early Romanesque) unassigned word * locca "Beizker, Schmerle ", first proposed in 1935. In doing so, he added the equivalent of French loche and the loach , which was borrowed from it into English, to the salmon words.

The middle debate about the salmon argument and original home

From 1911, the salmon words were undisputedly part of the Indo-European original language. Even after the end of National Socialism, the interpretation of the salmon argument for the original home of the Indo-Europeans remained controversial. The justification of the "Northern European hypothesis" was made easier by the discovery of salmon words in Tocharian and Ossetian at the same time, because they were documented as common language, and made more difficult because the reasons for the geographical spread of salmon words became increasingly problematic. What the spokesmen of the original Indo-European with the word "salmon" meant was unclear until 1970.

refutation

Salmon trout instead of salmon

Thieme pointed out that the salmon word in the Caucasus is not salmon but trout. For Krogmann, the name of the salmon could have been transferred to Salmo salar . In 1970 the American tocharist George Sherman Lane said: "And, in my opinion, the name in question probably did refer originally, not to the salmo salar at all, but rather to the salmo trutta caspius of the northwest Caucasus region", German : "And in my opinion, the name in question probably originally did not refer to Salmo salar at all , but to Salmo trutta caspius in the northwestern Caucasus region."

In 1976 Diebold presented three anadromous salmonids, trout fish that swim upriver to spawn and could be considered for a primordial Indo-European name * loḱsos : the salmon or sea trout Salmo trutta trutta and the two regional subspecies Salmo trutta labrax and Salmo trutta caspius . They are common in the rivers to the Black and Caspian Seas. In the course of the Indo-European expansion from the area of the Pontic steppe towards the Baltic Sea, the old salmon word for sea trout ( Salmo trutta trutta ) was transferred to the new, similar-looking fish, salmon ( Salmo salar ); the Russian form lososь covers both meanings. Wherever the Indo-Europeans encountered old-language names such as salmo or esox , they adopted them.

Reversal of the salmon argument

The many names for salmonids in the Indo-European languages arose because the speakers of the original Indo-European came across numerous fish for which they had no names because they did not know them from their original home. As a "known not, not named" German as "unknown, unnamed" it described Diebold. In 1985 he turned the salmon argument around: wherever a salmon word denoted Salmo salar , the indo-Europeans' original home could not be . In the same year, the tocharist Douglas Q. Adams headed his last essay on the subject with a play on words: "A Coda to the Salmon Argument" ; Coda means something like "tail" or "final part".

The late debate about the salmon argument and original home

The refutation of the salmon argument from 1970 onwards was made easier by the fact that the Kurgan hypothesis was a modern-based proposal for the Indo-European original home north of the Black Sea. The shift of the salmon name from Salmo salar to Salmo trutta coincided with this model. About 100 years after it was first mentioned, the salmon argument was obsolete. The etymological investigation of the salmon words has not been completed since then. As long as it is not clear how the Indo-European language area expanded, no statements can be made about the way in which the salmon word spread in the Baltic Sea area.

The salmon argument has not disappeared from Indo-European studies. Older manuals, which are compulsory in libraries, retain this assumption. New reference works mislead the named fish or avoid presenting the story of the salmon argument.

"Salmon argument"

term

Probably in analogy to the older “beech argument”, the term “salmon argument” was introduced by Mayrhofer in 1955. It is used as "the salmon argument" in the Anglo-Saxon specialist literature. The beech argument said that the beech does not occur east of a line from Königsberg (Prussia) to Odessa , but the word is of Indo-European origin and therefore the original home could not be in the Eurasian steppe landscape. One of the mistakes of this argument was the assumption that the ancient Indo-European beech word always meant the beech , although Greek φηγόϛ phēgós denoted the oak .

Involved

The debate surrounding the salmon argument began in 1883 and ended about a hundred years later. About 30 scientists took part with explanations or authoritative dictionary entries. In alphabetical order and with the years of the associated publications, they were:

Douglas Q. Adams (1985, 1997) - Émile Benveniste (1959) - A. Richard Diebold, Jr. (1976, 1985) - Robert Heine-Geldern (1951) - Hermann Hirt (1921) - Friedrich Kluge and later editor of the Etymological Dictionary of the German Language (1883-2002) - Sten Konow (1942) - Wolfgang Krause (1961) - Willy Krogmann (1960) - George Sherman Lane (1970) - Sylvain Lévi (1914) - John Loewenthal (1924, 1927) - James P. Mallory (1997, 2006) - Stuart E. Mann (1963, 1984) - Manfred Mayrhofer (1952, 1955) - Georg Morgenstierne (1934) - Karl Penka (1883) - Herbert Petersson (1921) - Julius Pokorny (1923, 1959) - Walter Porzig (1954) - Vittore Pisani (1951) - Johannes Schmidt (1890) - Otto Schrader (1883–1911) - Franz Specht (1944) - Paul Thieme (1951–1958) - Albert Joris van Windekens (1970)

- → The complete references can be found in the individual references.

The word "salmon"

The history of the development of the salmon argument was shaped by the philological research into salmon words. Even after the rebuttal of the salmon argument, aspects of linguistic-historical interactions and semantic transitions such as generalization ("salmon" to "fish") and change of meaning ("salmon" to "loach") remain unresolved.

Indo-European salmon words

Salmon words are attested in many Indo-European languages. They are of common origin, have been borrowed from one another and into neighboring non-Indo-European languages. Some attributions are controversial. Names similar to salmon words for fish that are not similar to trout occur mainly in Romance languages. An overview according to language branches, with loans and individual suggestions:

- Germanic languages

- Old Germanic * lahsaz "Lachs", Old , Middle High German lahs , New High German Lachs , Old Low German / Old Saxon lahs , Middle Low German las (s) (borrowed from it Polabian laś ), Old English leax , Middle English lax , Early New English lauxe, extinct (in the 17th century) , Old Norse , Icelandic , Swedish lax , Norwegian , Danish laks "salmon", Faroese laksur ; Mention was made of Middle Dutch las (s) , a reconstructed Gothic form * lahs and Scottish lax , although it remained unclear whether the Scottish-Gaelic language or Scots was meant. Yiddish לקס laks and its derivation lox , a general name for salmon in Jewish cuisine in the USA since the beginning of the 20th century, now common in US gastronomy for smoked salmon , arose from German salmon .

- Baltic languages

- urbaltisch * lasasā , Lithuanian , lašišà , lãšis "salmon"; Latvian lasēns , lasis "salmon" (from livisch laš ), old Prussian * lasasso (reconstructed from prescribed lalasso ). When the Baltic form as a loan word in the Baltic Finnish languages penetrated, was indogermanisch -ks- in Urbaltischen already become a sibilant, Indo -o but had not yet balt. -A- developed: Finnish , Karelian , olonetzisch , Vepsian , wotisch lohi , Estonian lõhi ; the Liv form laš was later adopted. The forms Sami luossa and Russian loch (лох) "salmon" come from Baltic Finnish . The German compound salmon trout was borrowed from its Low German form lassfare, lassför to Latvian lasvarde, lašveris and other forms, these to Lithuanian lašvaras, lašvoras.

- Slavic languages

- Proto-Slavic * lososь , Czech , Slovak losos , lower / Upper Sorbian Losos , Polish , Slovincian losos , Kashubian- losos (k) , altostslawisch , Russian , Ukrainian losos ( Cyrillic лосось ) belarusian LASOS "salmon". The South Slavic forms of Slovenian , Croatian and Serbian lósos seem to be borrowings from West and East Slavic . Old Hungarian laszos , Hungarian lazac "salmon" is borrowed from Slavic.

- Armenian language

- Central, New Armenian Լոսդի losdi, losti "salmon trout" with -di, -ti "body"

- Iranian languages

- Digorian Ossetian læsæg (Cyrillic лӕсӕг ) "salmon trout", either an Iranian peculiar form or perhaps a very old loan word that, through the mediation of ancient Slavic tribes , could have penetrated the north-western edge of the Iranian peoples to the Alans , the forerunners of the Ossetians.

- Tocharian B

- laks "fish", with an unexplained generalization of Indo-European * loḱs- "salmon trout"

- Romance languages (only individual suggestions)

- Late Latin-Early Romanesque * locca " Bearded goby , loach", also synonymous with Italian locca , Old French loche , dialectal loque , English loach , Provencal loco (also " barber "), Spanish loche, locha, loja. A folk Latin form * lócĭca "loach" seems to fit the Lithuanian lašišà "salmon". Connections from Italian lasca “Roach, Roach”, Italian laccia “Alse” and Sardinian laccia “gudgeon” as well as Basque la kleiner “little shark” as early loans received no reaction from the professional world.

- → Audio examples in Wiktionary

Stem forms

Early suggestions for a West Indo-European stem form were * laqsi-s and * loḱ-os-, * loḱ-es-, * loḱ-s . The first suggestion for an archetype of the salmon word after the discovery of Tocharian B laks was * laḱ-i, * laḱ-os . It was adopted as * laḱs-, * laḱ-so-s in standard dictionaries .

Because the Baltic loanwords in the Baltic Finnish languages had retained the Indo-European root vowel -o- , the headings changed from Indo-European * laḱs- to * loḱs- . In the specialist literature, the stem for "salmon" has since been given with * loḱs- and similar forms, for example * lóḱs- and * loḱso-, * loḱsi- , also with a weak stem vowel * ləḱsi- , furthermore * loḱ- .

importance

Many researchers accept the word meaning “the dabbed” in Lithuanian lãšas “drop”, lašė́ti “dribble”, Latvian lā̆se “sprinkle, dab”, lãsaíns “dotted, speckled”. John Loewenthal proposed this etymology in 1924. Four explanations have not prevailed:

- "Der Springer" to Indo-European * lek- "Bend, Windung " as Latin salmo "salmon" to salire "to jump". This interpretation does not apply because salmo is of non-Indo-European origin and only Latvian lễkti "fly, run, fall" would provide a connection.

- Against “the red” in ancient Indian lākṣā “red lacquer”, it was argued that the root * reg belonging to red reads “to color”.

- "Fängling" from Indo-European * lakhos "Fang" failed because this root does not match the individual language forms.

- The suggestion “water fish” from Goidelisch loch “lake” and Finnish lahti “bay” went almost unnoticed.

Pre-Indo-European salmon words

The Indo-European languages of Western and Southern Europe probably adopted two salmon words from the ancient population. The original names are not reconstructed. Their Latin forms are esox and salmo "salmon" with the related salar "trout".

- The Celtic group around esox includes Irish éo, éu, é, iach, Old Irish eo, Kymrian ehawc, eog, Cornish ehoc, Breton eok , keûreûk "jump salmon ", literally "giant salmon " from or, accordingly, Gaulish kawaros "giant" and esox . The Celts may have adopted this word from a northern Alpine non-Indo-European people and the Basques borrowed izokin "salmon" from it. A romanizing step between "esox" and "izokin" was also suspected. Basque izokin can also be based on itz "sea" and okin "bread", for example "bread of the sea".

- The Gallic- Latin salmo passed into the Italian vocabulary as salmone and developed into French saumon , English salmon , Dutch zalm , German Salm . With the associated form salpa , which is documented on the Balearic archipelago of the Pityuses , as well as with salar "trout", Berber aslem "fish", it can be used as an old fish name for Western Europe and North Africa. There is evidence of a Berber dialect variant šâlba .

The areas of distribution of the salmo and esox groups overlap. Besides welsh eog comes samon as a loan word in front of the late Middle English, as well Sowman next ehoc the extinct Cornish. No Indo-European salmon word has been found in Celtic languages. The word border between Salm and Salmon in Germany ran between the Rhine and Elbe in the Middle Ages. Seasonal names with salmon words such as lassus "autumn salmon " have been handed down from several regions in the Salm area.

The name "salmon trout"

Today several salmonids are called " salmon trout ". In Germany, the name has been widespread since the second half of the 20th century as a trade name for a cultivated form of the rainbow trout ( Oncorhynchus mykiss, formerly: Salmo gairdneri ), which comes from North America and has been valued in Europe since the 19th century . "Salmon trout", in Low German lassför as a historically customary term and therefore used in linguistic literature, means sea trout ( Salmo trutta trutta ). The fact that brown trout ( Salmo trutta fario ) and lake trout ( Salmo trutta lacustris ) are also referred to as salmon trout due to the color of the meat contributed to a certain linguistic confusion . The subspecies of sea trout occurring in the Caucasus and around the Black and Caspian Seas are the Black Sea trout ( Salmo trutta labrax ) and the Caspian trout ( Salmo trutta caspius ). Which of these fish was called * loḱs- or similar by the native Indo-European speakers is uncertain.

literature

- Сергій Конча: Міграції індоєвропейців у висвітленні лінгвістичної палеонтології (насвикладі). In: Українознавчий альманах 7, 2012, pp. 177-181, online . German: Sergij Koncha: The migration of the Indo-Europeans in the publications on linguistic paleontology (using the example of the name of the salmon) . In: Ukrainischer Almanach 7, 2012, pp. 177–181

- Dietmar Bartz: In the name of the salmon. In: ZOÓN. Issue 4, November / December 2010, ISSN 2190-0426 , pp. 70–74, online

- Vacláv Blažek, Jindřich Čeladín, Marta Běťákova: Old Prussian Fish-names . In: Baltistica 39, 2004, ISSN 0132-6503 , pp. 107-125, here pp. 112-114, see v. lalasso

- A. Richard Diebold, Jr .: Contributions to the IE salmon problem . In: Current Progress in Historical Linguistics, Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Historical Linguistics . Amsterdam 1976, ISBN 0-7204-0533-5 , pp. 341-387 (= North-Holland Linguistic Series 31)

- A. Richard Diebold, Jr .: The Evolution of Indo-European Nomenclature for Salmonid Fish: The Case of 'Huchen' (Hucho spp.) . Washington 1985, ISBN 0-941694-24-0 (= Journal of Indo-European Studies, Monograph Series 5)

- Frank Heidermanns: Salmon. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 17, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2000, ISBN 3-11-016907-X , pp. 528-530.

- James P. Mallory, Douglas Q. Adams: Salmon . In: Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture . London 1997, ISBN 1-884964-98-2 , p. 497

Web links

Links to audio samples for salmon words in different languages includes:

Individual evidence

In order to find references more quickly, to be able to use dictionaries with different editions or to clarify the context of the position, the keyword with the abbreviation s. V. specified. The following are cited in abbreviated form:

| Abbreviation | Full title |

|---|---|

| Diebold, Contributions | A. Richard Diebold, Jr .: Contributions to the IE salmon problem . In: Current Progress in Historical Linguistics, Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Historical Linguistics . Amsterdam 1976, ISBN 0-7204-0533-5 , pp. 341-387 (= North-Holland Linguistic Series 31) |

| Diebold, Huchen | A. Richard Diebold, Jr .: The Evolution of Indo-European Nomenclature for Salmonid Fish: The Case of 'Huchen' (Hucho spp.) . Washington 1985, ISBN 0-941694-24-0 (= Journal of Indo-European Studies, Monograph Series 5) |

| Smart | Friedrich Kluge : Etymological Dictionary of the German Language , 1st to 8th edition, Strasbourg 1883 to 1915, 9th to 24th edition, Berlin 1921 to 2002 |

| Schrader, Comparative Languages | Otto Schrader : Comparison of languages and prehistory. Linguistic-historical contributions to the study of Indo-European antiquity . Alle Jena, 1st edition 1883, 2nd edition 1890, 3rd edition 1906 |

| Schrader, Reallexikon | Otto Schrader : Real Lexicon of Indo-European antiquity. Basics of a cultural and peoples history of ancient Europe . 1st edition Strasbourg 1901, 2nd edition, edited by Alfons Nehring, Berlin, Leipzig, 1917–1929 |

| ZVS | Journal for comparative linguistic research ,also known as Kuhn's journal after its founder Adalbert Kuhn . As is customary in more recent Indo-European literature, the traditional abbreviation KZ has been replaced by ZVS ; since 1988 under the title Historical Linguistic Research |

- ↑ Schrader, Comparative Languages . 1st edition, p. 84

- ↑ Overview in Schrader, Sprachvergleichung. 3rd ed., Pp. 85-100

- ↑ Karl Penka: ariacae Origen. Linguistic-ethnological research on the oldest history of the Aryan peoples and languages. Vienna, Teschen 1883

- ↑ Ernst Krause: Tuisko-Land, the Aryan tribes and gods original home. Explanations of the legends of the Vedas, Edda, Iliad and Odyssey. Glogau 1891

- ↑ Johannes Schmidt: The original home of the Indo-Europeans and the European number system. In: Treatises of the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin, Phil.-Hist. Class, Berlin 1890, p. 13. See also Paul Kretschmer: Introduction to the history of the Greek language. 1st ed. 1896, 2nd unv. Göttingen 1970, p. 108

- ^ Schrader: Reallexikon. 1st edition, see v. fish

- ↑ Compilation of Schrader views: Reallexikon. 1st ed., Pp. 878-896, see v. Original home

- ↑ August Fick: Comparative Dictionary of Indo-European Languages , 2nd Volume, Göttingen ³1876, pp. 651, 765

- ^ Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm: German Dictionary , Volume 12, Leipzig 1885, Sp. 30, s. Salmon. The delivery dates from 1877, see Volume 33, Bibliography, Stuttgart / Leipzig 1971, p. 1074

- ↑ Kluge, 1st ed. 1883, s. V. Salmon. The delivery dates from 1882, according to Adolph Russell: Gesammt-Verlags-Katalog des Deutschen Buchhandels, an image of German intellectual work and culture. Volume 9, Strasbourg 1881/82, p. 1218

- ^ Schrader: Comparative languages. 1st edition, p. 85

- ^ Karl Penka: The origin of the Aryans. Teschen, Vienna 1886, p. 46 f.

- ^ Schrader: Comparative languages. 2nd ed., P. 165

- ↑ Johannes Schmidt: The original home of the Indo-Europeans and the European number system. In: Treatises of the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin, phil.-hist. Class, Berlin 1890, p. 20

- ^ Schrader: Reallexikon. 1st ed., P. 494, see v. salmon

- ↑ Kluge, 1st ed. 1883 to 8th ed. 1915, all s. Salmon. The 8th edition was completed "in the late year 1914", there S. X.

- ^ Paul Kretschmer: Introduction to the history of the Greek language. 1st edition, Göttingen 1896, quoted by Willy Krogmann: The salmon argument. In: ZVS 76 (1960), p. 161

- ^ Emil Sieg, Wilhelm Siegling: Tocharisch, the language of the Indoskythen. Preliminary remarks on a previously unknown Indo-European literary language. In: Meeting reports of the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences 36 (1908), pp. 915–934.

- ↑ Otto Schrader: The Indo-Europeans . Leipzig 1911 (= Wissenschaft und Bildung 77), p. 158 f., Also p. 10 and p. 33. In the second edition, which was heavily revised after Schrader's death, the reference to the Tocharian salmon word is no longer included; see Otto Schrader: Die Indogermanen , revised by Hans Krahe, Leipzig 1935. Lothar Kilian said that Schrader did not know the Tocharian word; in: To the origin of the Indo-Europeans, Bonn 1983, p. 38, ISBN 3-7749-2035-4 ; See also: De l'origine des Indo-Européens, Editions du Labyrinthe, Paris 2000, p. 51, ISBN 2-86980-029-0 . For Wolfgang Krause: On the name of the salmon, in: Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, Philological-historical class 1961, p. 83, and Albert Joris van Windekens, L'origine directe et indirecte de thokarien B laks “poisson” , in : Journal of the Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft 120 (1970), p. 305, is the discoverer Sylvain Lévi, Remarques sur les formes grammaticales de quelques textes en tokharien I , in: Mémoires de la Société de linguistique de Paris 18 (1912-1914) p 1-33, 381-423, here p. 389 (1914). Like Schrader, however, Krause uses the phrase that the salmon word has "appeared". Whether Schrader knew the Tocharian salmon word through correspondence with an editor of the fragments has not been researched; He learned the Tocharian words for salt and sowing from Sieg and Siegling ( Indo-Europeans, p. 160).

- ↑ Otto Schrader: The Indo-Europeans . Leipzig 1911 (= Science and Education 77), p. 10 f.

- ↑ Herman Hirt: Etymology of the New High German Language. 2nd edition 1921, reprint Munich 1968, p. 186

- ↑ Franz Specht: The Origin of the Indo-European Declination. Göttingen 1944, p. 30

- ↑ Julius Pokorny: The position of the Tocharian in the circle of the Indo-European languages. In: Reports of the Research Institute for the East and the Orient, 3 (1923), p. 50 f.

- ↑ Julius (= John) Loewenthal: Thalatta, investigations into the older history of the Indo-Europeans. In: Words and Things 10 (1927), p. 141

- ↑ Introductory: Cornelia Schmitz-Berning: Vocabulary of National Socialism. Berlin 1998, see v. Aryans

- ↑ Julius (= John) Loewenthal: Thalatta, investigations into the older history of the Indo-Europeans. In: Words and Things 10 (1927), p. 178

- ↑ Helmut Arntz: Herman Hirt and the home of the Indo-Europeans. In: Helmut Arntz (Hrsg.): Germanic and Indo-Germanic, Festschrift for Herman Hirt. Volume 2, Heidelberg 1936, p. 26. Arntz cited an article by Hirt from 1894.

- ^ Alfred Götze (Ed.): Trübners German Dictionary. Volume 4 (1943), p. 329, see v. Salmon. Cf. Wenke Mückel: Trübners German Dictionary (Volume 1–4) - a dictionary from the time of National Socialism. A lexicographical analysis of the first four volumes (published 1939–1943). Tübingen 2005 (= Lexicographica, Series Major Volume 125). For more on Götze's affinity for the Nazis, see pp. 70–72. The 11. and 12./13. Editions of Kluge's Etymological Dictionary (1934 and 1943) also do not mention the salmon argument. Götze's silence about this was not mentioned in the literature.

- ↑ Robert Heine-Geldern: The Tocharer Problem and the Pontic Migration. In: Saeculum II (1951), p. 247

- ↑ Paul Thieme: The home of the Indo-European common language. In: Academy of Sciences and Literature, treatises of the humanities and social sciences class 1953 No. 11, Wiesbaden 1954, p. 551. Anders Manfred Mayrhofer, in: Studies on Indo-European Basic Language, Issue 4 (1952), p. 46

- ↑ Willy Krogmann: The salmon argument. In: ZVS 76 (1960), p. 171

- ↑ "une bonne documentation archéologique pour jeter une lumière sur des évènements qu'à mon avis cette discipline ne peut éclairir", Denis Sinor: Introduction à l'étude de l'Eurasie centrale , Wiesbaden 1963, p. 223

- ^ Vsevolod Miller: Ossetian-Russian-German Dictionary , Volume 2, Leningrad 1929, p. 766

- ^ "[...] can scarcely be a loan-word from Russian losoś", Georg Morgenstierne. In: Norsk Tidskrift for Sprakvidenskap 6 (1934), p. 120, quoted from Paul Thieme: The home of the Indo-European common language. In: Academy of Sciences and Literature, treatises of the humanities and social sciences class 1953 No. 11, Wiesbaden 1954, p. 557. Émile Benveniste: Études saw “no reason” (“aucune raison”) for the origin from another language sur la langue ossète. Paris 1959, p. 125

- ↑ Sten Konow, in: Norsk Tidskrift for Sprakvidenskap 13 (1942) 214, quoted from Paul Thieme: The home of the Indo-European common language. In: Academy of Sciences and Literature, Treatises of the humanities and social sciences class 1953 No. 11, Wiesbaden 1954, p. 557. In addition Harold Water Bailey: Analecta Indoscythica I In: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 26 (1953), p 95, quoted from Émile Benveniste: Études sur la langue ossète. Paris 1959, p. 125, note 1

- ↑ Paul Thieme: The home of the Indo-European common language. In: Academy of Sciences and Literature, treatises of the humanities and social sciences class 1953 No. 11, Wiesbaden 1954, p. 557

- ↑ Willy Krogmann: The salmon argument. In: ZVS 76 (1960), p. 166

- ↑ Willy Krogmann: The salmon argument. In: ZVS 76 (1960), p. 167 f.

- ^ Paul Thieme: The salmon in India. In: ZVS 69 (1951) pp. 209-216. Ders .: The home of the Indo-European common language. In: Academy of Sciences and Literature, treatises of the humanities and social sciences class 1953 No. 11, Wiesbaden 1954, pp. 535–614. Ders .: The Indo-European Language. In: Scientific American , October 1958, p. 74.

- ^ Paul Thieme: The salmon in India. In: ZVS 69 (1951) pp. 209-212

- ^ Paul Thieme: The salmon in India. In: ZVS 69 (1951) p. 215

- ↑ Walter Porzig: The structure of the Indo-European language area. Heidelberg 1954, p. 184

- ↑ Manfred Mayrhofer: Old Indian lakṣā. The methods of an etymology . In: Journal of the Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft 105 (1955), pp. 175-183. For semantic reasons, Thiemes’s proposal is undoubtedly acceptable, “undoubtedly acceptable”, but not for etymological reasons, said Vacláv Blažek and others: Old Prussian Fish-names. In: Baltistica 39 (2004), pp. 112-114. Thiemes' lacquer hypothesis is mentioned in Thomas W. Gamkrelidse, Wjatscheslaw W. Iwanow: The early history of the Indo-European languages. In: Spectrum of Science, Dossier: Languages, 2006, pp. 50–57, online

- ↑ Willy Krogmann: The salmon argument. In: ZVS 76 (1960), p. 173

- ↑ Willy Krogmann: The salmon argument. In: ZVS 76 (1960), p. 173 f. Vacláv Blažek, among others, also agrees: Old Prussian Fish-names. In: Baltistica 39 (2004), pp. 112-114. Only the Italian Indo-Europeanist Vittore Pisani found the approach “out of the question”, “non […] nemmeno da discutere” , Vittore Pisani, in: Paideia 6 (1951), p. 184, quoted from Paul Thieme: The home of the Indo-European common language. In: Academy of Sciences and Literature, treatises of the humanities and social sciences class 1953 No. 11, Wiesbaden 1954, p. 553 note 4.

- ↑ Kluge, 17th edition 1957 to 21st edition 1975, all s. salmon

- ↑ The losdi containing Volume 3 of hrachia adjarian (Hrač'ya Ačaṙyan): Hajerēn armatakan baṙaran . (Armenian etymological root dictionary), Yerevan 1926 ff was completed 1929th

- ↑ a b c d Diebold, Contributions , p. 368

- ^ Wilhelm Meyer-Lübke: Romanesque etymological dictionary. 3rd edition, Heidelberg 1935, p. 413, see v. lŏcca

- ↑ George Sherman Lane: Tocharian. Indo-European and Non-Indo-European Relationships. In: Indo-European and Indo-Europeans. Papers presented at the Third Indo-European Conference at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia 1970, p. 83

- ^ Diebold, Contributions , p. 361

- ↑ Diebold, Huchen , p. 8

- ↑ a b Diebold, Huchen , p. 32

- ↑ a b Diebold, Huchen , p. 50

- ↑ Douglas Q. Adams: PIE * lokso-, (anadromous) brown trout 'and * kokso-, groin' and their descendants in Tocharian: A coda to the salmon argument. In: Indogermanische Forschungen 90 (1985), pp. 72-78. Adams rejected Diebold's inversion of the salmon argument because from the lack of terms it could not be concluded that they do not exist.

- ↑ Winfred P. Lehmann: The current direction of Indo-European research. Budapest 1992, p. 26

- ↑ " Armenian losdi , salmon ', Ossetian læsæg , salmon'," John Carpenter: fish. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd ed., Volume 9, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin - New York 1995, p. 121. "But it was later observed that the salmon are also found in the rivers of southern Russia", Robert Stephen Paul Beekes: Comparative Indo- European linguistics. An Introduction. Amsterdam 1995, p. 48

- ↑ "The question cannot be dealt with in more detail here". Frank Heidermanns: Salmon. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd ed., Volume 17, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin - New York 2000, p. 529

- ↑ Manfred Mayrhofer: Old Indian laksa. The methods of an etymology. In: Journal of the German Oriental Society 105 (1955), p. 180

- ↑ Cf. Douglas Q. Adams: PIE * lokso-, (anadromous) brown trout 'and * kokso-' groin 'and their descendants in Tocharian: A coda to the salmon argument. In: Indogermanische Forschungen 90 (1985), pp. 72-78

- ^ Günter Neumann, Heinrich Beck: Beech. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA) . 2nd Edition. Volume 4, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin - New York 1981, p. 56 f .; Winfred P. Lehmann: The current direction of Indo-European research. Budapest 1992, p. 25

- ↑ This compilation of spellings is based on Vacláv Blažek et al .: Old Prussian Fish-names . In: Baltistica 39 (2004), pp. 107-125, esp. 112-114. Supplements are documented individually. See also the compilation in Diebold, Contributions , pp. 350–353.

- ^ John A. Simpson: Oxford English Dictionary . 2nd edition Oxford 1989, s. lax sb.1

- ↑ George Vaughan Chichester Young, Cynthia R. Clewer: Føroysk-ensk orðabók. Peel (Isle of Man) 1985, v. laksur

- ↑ Diebold, Contributions , p. 351, but without lemma in the Middelnederlandsch Woordenboek and in the Woordenboek of the Nederlandsche Taal

- ↑ Kluge, 1st to 5th ed. 1883–1894, all s. salmon

- ↑ Kluge, 1st to 10th ed. 1883–1924, all s. salmon

- ^ John A. Simpson: Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd edition Oxford 1989, s. lox sb.2. - Ron Rosenbaum: A Lox on Your House. How Smoked Salmon Sold Its Soul and Lost Its Flavor. In: New Republic, January 29, 2013, online , accessed January 29, 2013

- ↑ Johann Sehwers : Linguistic-cultural-historical studies mainly on the German influence in Latvian. Wiesbaden 1953, reprint of the 1st edition Leipzig 1936, p. 69. Also Jānis Rīteris: Lietuviškai-latviškas žodynas (Lithuanian-Latvian dictionary). Riga 1929 and Beniaminas Serejskis: Lietuviškai-rusiškas žodynas (Lithuanian-Russian dictionary). Kaunas 1933, quoted from Ernst Fraenkel: Lithuanian Etymological Dictionary. Heidelberg 1962, vol. 1 p. 341 f., S. V. lašiša. For the Lithuanian forms, see Jonas Baronas: Rusu̜ lietuviu̜ žodynas (Russian-Lithuanian dictionary). Kaunas 1932, Nachdr. Nendeln 1968, also Adalbert Bezzenberger: Lithuanian research. Contributions to the knowledge of the language and folklore of the Lithuanians. Göttingen 1882 and Hermann Frischbier: Prussian dictionary. Vol. 1 p. 202, all quoted from Jonas Kruopas: Lietuviu̜ kalbos žodynas (Dictionary of the Lithuanian Language), Volume 7, Vilnius 1966, p. 171 f., S. V. lašvaras, lašvoras. See also: Stuart E. Mann: An Indo-European comparative dictionary. Hamburg 1984-87, Volume 1, Col. 662, see v. lāḱūs.

- ↑ see Bogumił Šwjela : German-Lower Sorbian Pocket Dictionary. Bautzen 1953, see v. salmon

- ↑ Witczak considers an Iranian descent from Hungarian lazac to Ossetian læsæg to be possible, see Krzysztof Tomasz Witczak: Romańska nazwa śliza (* locca) w indoeuropejskiej perspektywie (The Romance name of the loach (* locca) in an Indo-European perspective) . In: Studia romanica et linguistica thorunensia, Volume 4 (2004), p. 136

- ↑ Stuart E. Mann, Armenian and Indo-European historical phonology, London 1963, quoted in Diebold, Contributions , p. 354. Cf. also Stuart E. Mann: An Indo-European comparative dictionary. Hamburg 1984-87, Volume 1, Col. 661, see v. laḱǝsos. Critical to expressiveness George Sherman Lane: Tocharian. Indo-European and Non-Indo-European Relationships. In: Indo-European and Indo-Europeans. Papers presented at the Third Indo-European Conference at the University of Pennsylvania , Philadelphia 1970, p. 85. Krzysztof Tomasz Witczak: Romańska nazwa śliza (* locca) w indoeuropejskiej perspektywie (The Romance name of the loach (* locca) from an Indo-European perspective) . In: Studia romanica et linguistica thorunensia, Volume 4 (2004), p. 134, sees Armenian * loc'- , not * los- as a connection to Indo-European * lóḱs-, but uses it on p. 137 as evidence for the root vowelism - O-.

- ↑ Wolfgang Krause: On the name of the salmon. In: Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, philological-historical class 1961, p. 98. Kluge s. V. Salmon in the 23rd and 24th edition (1995, 2002) læsæg for "probably borrowed or not belonging". The borrowing theory is Blažek as "improbable", "unlikely", Vacláv Blažek et al .: Old Prussian Fish-names. In: Baltistica 39 (2004), p. 113

- ↑ Revista portuguesa [19] 23, p. 128, quoted from Wilhelm Meyer-Lübke: Romanisches etymologisches Woerterbuch. 3rd edition, Heidelberg 1935, p. 413, see v. lŏcca

- ^ Charles Frédéric Franceson: New Spanish-German and German-Spanish dictionary. 3rd edition, Volume 1, Leipzig 1862, see v. locha, loche, loja

- ↑ Krzysztof Tomasz Witzak: Romańska nazwa śliza (* locca) w indoeuropejskiej perspektywie (The Romance name of the loach (* locca) in an Indo-European perspective) . In: Studia romanica et linguistica thorunensia, Volume 4 (2004), pp. 131-137, summary p. 137

- ^ Stuart E. Mann: An Indo-European comparative dictionary. Hamburg 1984-87, Volume 1, Col. 661, see v. laḱǝsos

- ^ Stuart E. Mann: The cradle of the "Indo-Europeans": Linguistic evidence. In: Man 43 (1943), pp. 74-85. German under the title: The original home of the Indo-Europeans. In: Anton Scherer: The original home of the Indo-Europeans. Darmstadt 1968, pp. 224–255, here p. 232. Italian laccia already with Johann Christian August Heyse: Concise dictionary of the German language. Volume 2, Magdeburg 1849, p. 2, see v. salmon

- ^ Wiktionary s. V. salmon

- ↑ August Fick: Comparative Dictionary of Indo-European Languages. 4th ed., Volume 1, Göttingen 1890, p. 531

- ^ Schrader, Reallexikon. 1st ed., P. 495, see v. Salmon.

- ↑ Herbert Petersson: Studies on the Indo-European Heteroklisie. In: Skrifter av vetenskaps-societeten i Lund, Volume 1, Lund 1921, p. 20

- ↑ Alois Walde: Comparative dictionary of the Indo-European languages. Volume 2, Berlin and Leipzig 1927, p. 380 f., S. V. laḱs-, as well as Julius Pokorny: Indo-European Etymological Dictionary. Volume 1, 1st edition 1959, p. 653, see v. laḱ-

- ↑ A. Senn: The relations of the Baltic to the Slavic and Germanic. In: ZVS 70 (1954), p. 179. In addition Willy Krogmann: The salmon argument. In: ZVS 76 (1960), p. 177

- ↑ James P. Mallory: The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European world. Oxford 2006, p. 146; cf. * loksos in Robert Stephen Paul Beekes: Comparative Indo-european linguistics. An introduction. Amsterdam 1995, p. 48

- ↑ Vacláv Blažek u a. .: Old Prussian Fish-names. In: Baltistica 39 (2004), p. 113, citing James P. Mallory, Douglas Q. Adams: Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture. London 1997, p. 497

- ^ Frank Heidermanns : Salmon. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd ed. Volume 17, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin - New York 2000, p. 528

- ↑ Krzysztof Tomasz Witczak: Romańska nazwa śliza (* locca) w indoeuropejskiej perspektywie (The Romance name of the loach (* locca) in an Indo-European perspective). In: Studia romanica et linguistica thorunensia, Volume 4 (2004), p. 137

- ↑ Julius Pokorny: Indo-European Etymological Dictionary , Volume 1, 1st edition 1959, p. 653, see v. lak-

- ↑ John Loewenthal: Ahd. Lahs. In: ZVS 52 (1924), p. 98

- ↑ Julius Pokorny: Indo-European etymological dictionary. Bern, Tübingen 1959 ff., P. 673; first from August Fick: Comparative Dictionary of Indo-European Languages. 1st part, 4th edition, Göttingen 1890, see v. laqsi-s

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Krause: On the name of the salmon. In: Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, philological-historical class 1961, p. 97

- ↑ So Kluge, 20th ed. 1967 to 24th ed. 2002, all s. V. Salmon. On the other hand, Diebold, Contributions , p. 358

- ^ Paul Thieme: The salmon in India. In: ZVS 69 (1951) p. 209

- ↑ Paul Thieme: The home of the Indo-European common language. In: Academy of Sciences and Literature, treatises of the humanities and social sciences class 1953 No. 11, Wiesbaden 1954, p. 558 note 1

- ↑ Wolfgang Krause: On the name of the salmon. In: Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, philological-historical class 1961, p. 93

- ↑ Kerttu Mäntylä: Salmon. In: Orbis 19 (1970), p. 172 f .; Mäntylä describes Loch as “Celtic”.

- ↑ but Kluge, z. B. 24th edition, v. Salmon, references

- ^ Heinrich Wagner: On the Indo-European salmon problem. In: Journal of Celtic Philology. Volume 32 (1972), p. 75. First, Schrader, Reallexikon , 1st edition, p. 494, see v. Salmon. See also Louis H. Gray: On the etymology of certain celtic words for salmon. In: American Journal of Philology. Volume 49 (1928), pp. 343-347, as well as Julius Pokorny: The position of the Tocharian in the circle of the Indo-European languages. In: Reports of the Research Institute for the East and the Orient. Volume 3 (1923), p. 50 f., Note 2. On Pokorny's skepticism, Old Irish bratán "salmon" to brat "robbery", and on Gray's suggestions see Wolfgang Krause: Zum Namen des Lachses . In: Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, philological-historical class 1961, p. 95

- ^ R. Larry Trask: Etymological Dictionary of Basque . Ed .: Max W. Wheeler. University of Sussex, Falmer, UK 2008, p. 236 ( archived PDF ( memento of June 7, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) [accessed on September 17, 2013]).

- ↑ John P. Lindstroth: Arrani, Arrain, Arrai. En torno al protovasco Arrani y sus derivaciones lingüísticas. In: Fontes linguae vasconum. Studia et documenta. Volume 30 (1998), p. 403

- ^ Heinrich Wagner: On the Indo-European salmon problem. In: Journal of Celtic Philology. Volume 32 (1972), p. 75. Cf. Julius Pokorny: The position of the Tocharian in the circle of the Indo-European languages. In: Reports of the Research Institute for the East and the Orient , 3 (1923), p. 51

- ↑ Edmond Destaing: Dictionnaire français-berbère (dialecte of Beni-Snous). Paris 1914, p. 282 f., Quoted from Heinrich Wagner: On the Indo-European salmon problem. In: Journal of Celtic Philology. Volume 32 (1972), p. 76

- ↑ Diebold, Contributions , p. 351. In Diebold, however, Scottish lax is missing , see above.

- ↑ Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm: German Dictionary, Volume 14, Sp. 1697 f., S. V. Salm

- ↑ Diebold, Huchen , pp. 4, 16 ff.

- ^ Johann Friedrich Schütze: Holsteinisches Idiotikon. Volume 3, Hamburg 1802, p. 14

- ↑ Fishbase s. V. Salmon trout .

- ↑ Diebold, Huchen , p. 30