Liselotte of the Palatinate

painting by Hyacinthe Rigaud , ca.1713 ( Versailles Palace ). The black veil is a widow's veil, the hermelin- lined coat with golden lilies on a blue background distinguishes her as a member of the French royal family. Liselotte herself was so enraptured by the resemblance of this portrait that she had various copies made, which she sent to relatives: "... one saw his life like nothing else than Rigaud painted me".

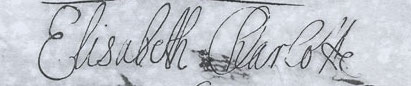

Liselotte's signature:

Elisabeth Charlotte, Princess of the Palatinate , called Liselotte of the Palatinate (born May 27, 1652 in Heidelberg , † December 8, 1722 in Saint-Cloud near Paris ), was Duchess of Orléans and sister-in-law of King Louis XIV of France. It achieved literary and historical importance primarily through its correspondence, which is of cultural and historical value due to its sometimes very blunt descriptions of French court life and is today one of the best-known German-language texts of the Baroque period .

Elisabeth Charlotte came from the Palatinate-Simmern Calvinist line of the Wittelsbach family and was a granddaughter of the Palatinate Elector Friedrich V , who, as the so-called "Winter King" of Bohemia, had triggered the Thirty Years' War , and his wife Elisabeth Stuart . Her father Karl I. Ludwig had only just before Liselotte's birth regained the Electoral Palatinate through the Peace of Westphalia , after the family had lived in exile in Holland for decades. His sister Sophie von Hannover (Sophie von der Pfalz) took Liselotte in 1659 for four years as a foster child after their parents separated; she remained her most important caregiver for life.

In 1671 she was married to the only brother of the "Sun King", Duke Philippe I of Orléans ; the marriage became very unhappy after about a decade of relative satisfaction. In 1688 the king took their marriage as an occasion for the Palatinate War of Succession , in which, to Liselotte's desperation, the Electoral Palatinate was devastated several times. And finally her previously good relationship with the king suffered from her hostility to his mistress Madame de Maintenon , who is said to have persuaded Louis XIV to persecute the Huguenots . This threefold misery, as well as Liselotte's inappropriateness in French court society, dominates their correspondence. After the king's death in 1715, her son Philippe II of Orléans became regent of France until 1723 and her situation improved, but health problems now came to the fore.

Although she only had two surviving children, she not only became the ancestor of the House of Orléans , which came to the French throne with Louis Philippe , the so-called "citizen king", from 1830 to 1848, but also became the ancestor of numerous European royal families, so she was also called the “belly of Europe”. Through her daughter, she was the grandmother of the Roman-German Emperor Franz I Stephan , the husband of Maria Theresa , and great-grandmother of the Emperors Joseph II and Leopold II and the French Queen Marie Antoinette .

Life

Germany

Elisabeth Charlotte was born on May 27, 1652 in Heidelberg. She was only called "Liselotte". Her parents were Elector Karl I. Ludwig von der Pfalz (the son of the " Winter King ") and Charlotte von Hessen-Kassel . Liselotte was a thin child when she was born, who had been given the names of his grandmother Elisabeth Stuart and his mother Charlotte by emergency baptism . She first grew up in the Reformed Protestant faith, the most widespread denomination in the Palatinate at that time.

Liselotte was a lively child who liked to run around and climb trees to nibble on cherries; she sometimes claimed that she would have preferred to be a boy, and referred to herself in her letters as " rauschenplattenknechtgen ".

The parents' marriage quickly turned into a disaster and domestic scenes were the order of the day. In 1658, Elector Karl Ludwig separated from his wife Charlotte in order to marry her former lady-in-waiting, Freiin Marie Luise von Degenfeld, on her left hand , who thus became Liselotte's stepmother. Liselotte probably perceived her as an intruder and refused her, but she loved at least some of her half-siblings, 13 Raugräfinnen and Raugrafen . With two of her half-sisters, Luise (1661–1733) and Amalie Elisabeth, called Amelise (1663–1709), she kept in lifelong correspondence. The young deceased Raugraf Karl Ludwig (1658–1688), called Karllutz , was a particular favorite of hers , she called him "Schwarzkopfel" because of his hair color and was ecstatic when he later visited her (1673) in Paris; she was very saddened by his early death.

The most important caregiver in her life was her aunt Sophie von der Pfalz , her father's youngest sister, who also lived in Heidelberg Castle with Karl Ludwig until her marriage in 1658 . After Sophie had left Heidelberg as the wife of Duke Ernst August , who later became the first Elector of Hanover, and in order to take away her mother's daughter, the Elector sent Liselotte at the age of seven to the court of Hanover , where she said she had the happiest four years of her life. Sophie finally became a kind of “surrogate mother” for Liselotte and remained her most important confidante and correspondent throughout her life. During this time they also made a total of three trips to The Hague , where Liselotte was supposed to learn a more polished behavior and met her grandmother Elisabeth Stuart , the former "winter queen" of Bohemia , who was still living there in exile. She was “very fond of” her granddaughter, although in general she did not particularly love children, and found that Liselotte resembled her family, the Stuarts : “ Schi is not leike the hous off Hesse, ... schi is leike ours. “Her relatives in The Hague also included the slightly older William of Orange-Nassau , who was her playmate and who would later become King of England. She later also remembered the birth of Sophie's son Georg Ludwig , who also became King of England. As early as 1661, Liselotte knew French so well that she got a French woman named Madame Trelon who did not understand German as governess . When Ernst August assumed the office of Prince-Bishop of Osnabrück in September 1662, Liselotte and her foster parents moved to Iburg Castle .

In 1663 the elector granted Liselotte's mother Charlotte adequate compensation, who then left the Heidelberg residence. Immediately afterwards the elector brought his daughter back to the court in Heidelberg, where she received visits from her aunt Sophie a few more times. Liselotte now received a courtly girl education, which was common at that time for royal houses, which, in addition to French lessons , dancing, "playing the spinet ", singing, handicrafts and history , consisted above all in the fact that she was regularly read from the Bible "in two languages, German and French". Her new governess, Maria Ursula Kolb von Wartenberg , called "the Kolbin", on whom she played some pranks, should also make sure that she should not be caught in "any hatred or prejudice against someone because they belong to a different religion". The last point was very unusual in its time and was based on the relatively free convictions of her father Karl Ludwig, who was a Calvinist himself , but had a Concordia church built in Mannheim for the supporters of the Calvinist (or Reformed ), Lutheran and Catholic Denomination was open. Liselotte benefited from this relatively open religious attitude throughout her life; she had already got to know the Lutheran denomination at court in Hanover and decades later she knew how to sing Lutheran chorales by heart. Before her marriage she had to convert to the Catholic faith for dynastic reasons ; But throughout her life she remained skeptical of any dogmatism and often expressed herself critically about “the priests”, even when she went to mass every day; she was always convinced of the Calvinist doctrine of predestination , every morning she read a section in the Luther Bible and criticized the cult of saints .

From her youth in Heidelberg, her first stable master and steward, Etienne Polier, became a confidante whom she took with her to France after her marriage and who remained in her service for life.

France

Marriage

For political reasons, Liselotte was married in 1671 to the brother of Louis XIV, Duke Philippe d'Orléans , known as " Monsieur " - in the Ancien Régime a title that belonged to the eldest brother of the king. As his wife, she was called “ Madame ” in France from then on . This marriage was brokered by Anna Gonzaga , a widowed sister-in-law of Elector Karl Ludwig and an old friend of Duke Philippe, who picked Liselotte from Heidelberg for Paris. The wedding by procurationem took place on November 16, 1671 in the cathedral Saint-Étienne in Metz before Bishop Georges d'Aubusson de La Feuillade , the deputy bridegroom was the Duke of Plessis-Praslin. The day before, she had already solemnly renounced her old Reformed faith and converted to the Roman Catholic faith. She first saw her husband, 12 years her senior, on November 20, 1671 in Châlons .

“ Mons (ieur) didn't look ignoble , but he was very short , had pitch black hair, eyebrows and eyelids, big brown eyes, a long and rather narrow face, a big nose, a mouth that was too small and ugly teeth more feminine than man's manners per se, loved neither horses nor hunting, nothing but games, holding cercle , eating well, dancing and being dressed, in a word, everything that ladies love. ... The king loved gallantry with ladies, I do not believe that my master has been in love in his life. "

Outwardly, Elisabeth Charlotte led a glamorous life from then on and had (until his death in 1701) her own apartments in his residences, the Palais Royal in Paris, and the Saint-Cloud castle . However, the couple lived mostly at the royal court, where they had to be present for about three quarters of the year, first in the New Saint-Germain-en-Laye Palace and, after its completion in 1682, in the Versailles Palace , where they had two adjacent apartments in the main wing were available. They also had apartments in Fontainebleau Castle , where the court went in autumn for the hunting season, in which Liselotte - unlike her husband - took part with enthusiasm. She often rode with the king through the woods and fields all day long, from morning to night, without being deterred by occasional falls or sunburn. From Fontainebleau, the couple made regular detours to Montargis Castle , which belonged to Monsieur and which, according to their marriage contract, would later fall to Madame as a (hardly used) widow's seat. Liselotte had her own court of 250 people, which cost 250,000 livres annually, the duke had an even larger one.

For Philippe it was already the second marriage, his first wife Henriette died suddenly and under unexplained circumstances in 1670. He also brought two daughters into the marriage, nine-year-old Marie-Louise , with whom Liselotte was able to develop a warm, but rather sisterly relationship, and Anne Marie , who was only two years old , who had no memory of her own mother and who loved her as much as she did own child.

Liselotte and Philippe's marriage was problematic for both partners, as he was homosexual and lived it out quite openly. He led a largely independent life, together with and influenced by his chief and long-time lover, the Chevalier de Lorraine ; He also had other favorites and numerous minor affairs with younger men, which the Chevalier himself and one of his friends, Antoine Morel de Volonne, passed on to him, whom Monsieur made Liselotte's steward between 1673 and 1683 . She had no illusions about the entire situation and Morel: "He stole, he lied, he swore, was an Athée ( atheist ) and sodomite , kept school and sold boys like horses."

Philippe was reluctant to fulfill his marital duties , he didn't want to be hugged by Liselotte if possible, and even scolded her when she accidentally touched him in his sleep. After he had fathered three offspring with her - including the male heir and later regent Philippe - he finally moved out of the shared bedroom in 1676 and thus ended their sexual life together, to Liselotte's own relief and with her consent.

Liselotte had no choice but to come to terms with these conditions, and she ultimately became an unusually enlightened woman for her time, albeit in a somewhat resigned way:

"Where have you and Louisse got stuck that you know them so little? (...) whoever hate everyone who loves young guys would not be able to love 6 people here (...) there are all kinds of genres; ... ( This is followed by a list of various types of homo- and bisexuality , as well as pederasty and sodomy , editor's note ) ... Then you tell, dear Amelisse, that the world is worse than you never thought. "

Her most important biographer, the historian and Antwerp professor for French baroque literature Dirk Van der Cruysse, judges: “She was providentially placed between two completely dissimilar brothers, of whom the older made up for the fundamental inability of his younger brother through his appreciation and friendship. to love anyone other than herself. She showed her affection to both, wholeheartedly and without any ulterior motives, and accepted the overwhelming power of the one as well as the Italian inclinations of the other without complaint, as destined by fate. "

At the court of the Sun King

Liselotte got on very well with her brother-in-law Ludwig XIV. He was "... charmed that this was an extremely witty and lovely woman, that she danced well ..." (the king himself was an excellent dancer and appeared in ballets by Lully ), and he was open, humorous and refreshing amused uncomplicated nature. A friendship developed and they often went hunting together - a rather unusual occupation for a lady at the time. Her desire to go for a walk was also noticed at the French court and was initially laughed at - she even went for a walk in the park at night - but the king was delighted: “Whether Versailles has the most beautiful rides, nobody went and went for a walk but me. The King used to say: 'I am a que Vous qui jouissés des beautés de Versailles (you are the only one who enjoys the beauties of Versailles)'. In addition, she shared a love of theater of all stripes with the Sun King and was also aware that she was allowed to experience a high point of French culture:

“When I came to France, I got to know people who will probably not be around for centuries. There were Lully for the music; Beauchamp for the ballet; Corneille and Racine for tragedy; Molière for comedy; the Chamelle and the Beauval, actresses; Baron, Lafleur, Torilière and Guérin, actors. All of these people were excellent in their field ... Everything you see or hear now does not match them. "

Although she was not particularly beautiful (an important plus at the French court) and somewhat unconventional by French standards, Liselotte also made a very good impression on the courtiers and witty Parisian salon ladies . They originally had prejudices and expected a 'rough' and 'uncultivated' foreigner. Alluding to Queen Marie Thérèse of Spanish descent , who never really learned to speak French and was too good-natured for the malicious jokes of the “ precious ”, Madame de Sévigné had previously ironically mocked herself: “What a delight to have a wife again who doesn't have one Can French! ”. But after she got to know Liselotte, she noticed a “charming directness” in her and said: “I was amazed at your joke, not at your lovable joke, but at your joke of common sense ( esprit de bon sens ) ... I assure you To you that it cannot be expressed better. She is a very idiosyncratic person and very determined and certainly has taste. ” Madame de La Fayette was also positively surprised and made very similar comments about Liselotte's esprit de bon sens . The cousin of King Mademoiselle de Montpensier said: “When you come from Germany, you don't have a French way of life”, but: “She made a very good impression on us, but Monsieur didn't think so and was a little surprised. But when she gave herself up in French, that was something completely different. "When the Electress Sophie and her daughter visited her niece Liselotte in Paris and Versailles in 1679, she stated:" Liselotte ... lives very freely, and full of innocence: hers Happiness cheers up the king. I have not noticed that her power goes further than making him laugh, nor that she is trying to keep it going. "

In France, Liselotte only had two German relatives, two older aunts, with whom she had regular contact: Luise Hollandine von der Pfalz , a sister of her father and abbess of the Maubuisson monastery since 1664 , and Emilie von Hessen-Kassel , a sister of her mother, who had married the Huguenot general Henri Charles de La Trémoille , Prince of Taranto and Talmont. From her court she was mainly the Princess Catherine Charlotte of Monaco , who exercised the office of their chief chamberlain, but died in 1678, and her lady-in-waiting Lydie de Théobon-Beuvron .

children

Elisabeth Charlotte von der Pfalz and Philippe I. d'Orléans had three children together:

- Alexandre Louis d'Orléans, Duke of Valois (June 2, 1673– March 16, 1676)

- Philippe II. D'Orléans (1674–1723) ∞ Françoise Marie de Bourbon (1677–1749), a legitimate illegitimate daughter of Louis XIV.

- Elisabeth Charlotte d'Orléans (1676–1744) ∞ Leopold von Lothringen (in-laws of Maria Theresa of Austria ).

Liselotte had a warm relationship with her children and the untimely death of her eldest son Alexandre Louis at the age of less than 3 was a very hard blow for her. She cried for 6 months before the birth of her daughter, who apparently helped her over the terrible loss.

"I do not think that one can die out of excessive sadness, because otherwise I would without a doubt go on it, because what I felt in myself is impossible to describe."

Her younger son Philippe not only looked like her outwardly, but shared her literary, artistic and scientific interests; During his father's lifetime and shortly thereafter, the relationship with his mother was distant, as the father and his favorites influenced him and allowed him everything, while the mother criticized his debauchery. Later, however, the relationship improved and in the end they were very close, which was not exactly common in royal houses at the time.

Difficulties and tragedies

From around 1680 there were massive problems, as the Chevalier de Lorraine, the Marquis d'Effiat and other favorites of her husband incited him more and more against Liselotte and intrigued against her in order to eliminate her influence on Monsieur. She became the victim of an aggressive guerrilla war and grueling harassment, and her marital relationship was now completely shattered. Among other things, her enemies used slander to get some of her confidants, including the lady-in-waiting Lydie de Théobon-Beuvron, whom she valued, dismissed and banished from court, including her husband, the Chamberlain Count de Beuvron , and the Baron de Beauvais . After their departure, she was exposed to the intrigues of the favorites and the arbitrariness of her husband almost defenseless, especially since at the same time the relationship with the king cooled, as his mistress Madame de Maintenon gained influence and the king was less and less inclined to anger his brother by he intervened in favor of Liselotte. The intrigues led to the isolation and disappointment of Liselotte, who now withdrew more and more into her writing room. "Monsieur ... has nothing in the world in his head but his young fellows to eat and drink with them all nights and gives them unheard-of sums of money, nothing costs him nor is too expensive in front of the boy; meanwhile, his children and I hardly have what we need. "

Simultaneously with these domestic problems of Liselotte, French nobles and courtiers had formed a secret homosexual 'brotherhood' which required those who joined her to "take an oath to renounce all women"; the members are said to have carried a cross with a relief on which a man "tramples a woman in the dust" (in an unholy allusion to the Archangel Michael ). The Duke of Orléans was not a member of this brotherhood, but many of his favorites were. Indeed, some courtiers in Paris behaved scandalously and several incidents were reported in which women were sadistically tortured and a poor waffle seller was raped, castrated and killed by courtiers. When it became known that the 'Brotherhood' also included the Prince de la Roche-sur-Yon and the Comte de Vermandois , one of the king's legitimate sons with Louise de La Vallière , there was a wave of exiles in June 1682 . Louis XIV punished his own son very severely and sent him to war, where he died shortly afterwards at the age of 16. Liselotte von der Pfalz was directly affected by this incident, since Vermandois had been left to her as a ward by his mother when she entered the monastery (1674) : “The Comte de Vermandois was really in good spirits. The poor person loved me as if I were his birth mother. ... He told me his whole story. He had been horribly seduced. ”One of his 'seducers' is said to have been the Chevalier de Lorraine - her husband's lover and her avowed enemy.

Other problems arose in the following years for Liselotte, as she harbored a massive aversion to Madame de Maintenon , the last important mistress and from the end of 1683 the secret wife of Louis XIV, whom she increasingly dominated. Liselotte could not accept the social position and the lust for power of this woman, the widow of a playwright, who rose from difficult circumstances and described her in numerous letters and the like. a. with swear words like "old woman", "old witch", "old Vettel", "old Zott", "Hutzel", "Kunkunkel", " Megäre ", " Pantocrat " or as "mouse filth mixed with the peppercorns". At the instigation of the Maintenon, the Duchess's contacts with her brother-in-law were restricted to formal occasions, and if the King retired to his private apartments with some chosen relatives after the evening meal, she was no longer admitted. In 1686 she wrote to her aunt Sophie: “Where the devil can't get there, he sends an old woman, whom we all want to find out in the royal family ...” and in 1692: “What an executioner our old woman rumpompel here wanted to take away, I should probably think he was an honest man and would be happy to ask him to be ennobled ”. Since their correspondence was secretly monitored, the king and the Maintenon found out about it, of course with adverse effects on Liselotte's once good contact with Ludwig.

In addition, after 1680 - after the poison affair , in which u. a. his previous mistress Madame de Montespan was involved - underwent a change, and under the influence of the bigoted Madame de Maintenon from a former philanderer who was primarily interested in his pleasure and not infrequently crept into the apartments of Liselotte's maid of honor, into one Man transformed who suddenly preached morality, piety and religion. He therefore issued the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685 , which ended the practice of tolerance in the Edict of Nantes and triggered renewed persecution of the Huguenots , many of whom emigrated to Holland and Germany, including Liselotte's aunt Emilie von Hessen-Kassel. The emigrants were supported by the Brandenburg ambassador, Ezechiel Spanheim, with advice and action; Liselotte was very close to him because he had once been the tutor of both her father and her brother. Since Liselotte herself was originally a Reformed, i.e. Huguenot, and - in contrast to the even half Huguenot Maintenon - had only become a half-hearted Catholic - or more precisely: a woman who had a very free attitude towards religion - this was one for her problematic situation and she later wrote to her aunt Sophie: “Had this been done, as I was at Heydelberg 26 years ago, EL (= your lover, author's note) would never have wanted to persuade me to be Catholic The guilt for all this and for the bigotry of the king she primarily attributed not to himself, but to the influence of Madame de Maintenon, who she felt as hypocritically bigoted, greedy for power and corrupt, and who hated anyway:

"Our s (eliger) king ... didn't know a word about the h. font ; he had never been allowed to read it; said that if he only listened to his confessor and talked about his pater noster , everything would be fine and he would be completely godly; I often complained about it, because his intention has always been sincere and good. But he was made to believe , the old Zott and the Jesuwitter , that if he were to plague the Reformed, that would replace the scandal that he committed with the double adultery with the Montespan . That's how you betrayed the poor gentleman. I have often told these priests my opinion about it. Two of my confessors, pere Jourdan and pere de St. Pierre , agreed with me; so there were no disputes. "

At the royal court, however, the topic was taboo: “EL (your lover) are right to say that one does not talk about the agony here if one does the poor Reformed, one does not hear a single word about it. On what EL say about this, EL can surely think that I am not allowed to say anything, but the thoughts are duty-free; but i have to say that whatever IM (Her Majesty) may be saying on this, don't believe anything if it's mad. de Maintenon, nor does the Archbishop of Paris say; Only the king believes in religious matters. ”Liselotte, however, also saw the opportunities presented by the Huguenots' emigration to the Protestant countries:“ The poor Reformed ... who settled in Germany will make the French common. Mons. Colbert is supposed to have said that many are subject to kings and princes wealth, therefore wanted everyone to marry and have children: so these new subjects of the German electors and princes will become wealth. "

When the Wittelsbach line of Palatinate-Simmern expired in 1685 with the death of Liselotte's brother, Elector Karl von der Pfalz , Liselotte's brother-in-law, Ludwig XIV., Raised a claim to the Electoral Palatinate, contrary to the inheritance contract, and began the War of the Palatinate Succession . a. Heidelberg, including the palace and Mannheim, were systematically destroyed. For Liselotte, who at the same time also had to cope with the death of her beloved half-brother Karllutz , this was probably the most traumatic time of her life. She suffered a lot from the devastation of her homeland and from the fact that this officially also happened in her name: “... As soon as I had recovered a little from poor Carllutz's death, the terrible and pathetic misery in the poor Palatinate began, and What hurts me most about it is that my name is used to plunge poor people into utter misfortune ... ”. "... So I can not help but regret and weep that I have so to say the downfall of my fatherland ...".

This situation inevitably brought her into a strong inner conflict with the king and all of her surroundings, which, to make matters worse, often reacted with naive incomprehension.

“… Every night, as soon as I fall asleep a little, it seems to me that I am at Heydelberg or Manheim and you see all the devastation, and then I drive up in a sleepy state and cannot fall asleep again in two whole hours; Then I remember how everything was in my time, in what state it is now, yes, in what state I myself am, and then I can't refrain from flening (flenning = crying, author's note) ...; And what's more, you don't feel bad that I'm sad about it, but I can't let it go ... "

Her husband Philippe generously distributed the spoils of war that fell on him (the so-called Orleans money) to his favorites, in particular to the Chevalier de Lorraine.

In 1692 Liselotte had to experience that her powerlessness extended to her own children: Louis XIV married her son Philippe against her will to Françoise-Marie de Bourbon , one of his illegitimate but legitimate daughters, whom he had with Madame de Montespan . The king also married his other "bastards from double adultery" within his family, because they could not have been brought to foreign courts, hardly even to the high nobility in France, and marrying them "under class" he saw as unworthy of him on. Liselotte and the courtiers found this marriage a mesalliance and humiliation. Therefore, she reacted with indignation and anger. Various chroniclers report that she no longer had her emotions under control, burst into tears of desperation in front of the whole court, and Saint-Simon writes that she slapped her son in front of the whole court for having consented to the marriage. The wedding took place on February 18, 1692. The king gave his daughter a pension of 50,000 Écus and precious stones worth 200,000 Écus, but the dowry of two million promised in the marriage contract is said to never have been paid. This forced marriage did not turn out to be a happy one either, and Philippe would cheat his wife to the end of his life with other women.

In 1693 Elisabeth Charlotte fell ill with life-threatening pox ( smallpox ). For fear of infection, the king and almost the entire court fled. She defied the instructions and ideas of contemporary doctors and survived the disease, but kept a pockmarked face. She did not get upset about it, because she had always considered herself ugly anyway (in excessive exaggeration, as earlier portraits by Mignard and Largillière, among others, show) and had no interest in beauty care or make-up. Possibly as a further consequence of the disease, it also increased so much from 1694 onwards that it hindered her walks. Even so, she continued to hunt, but only mounted horses that were big and strong enough to support her weight. The external change can also be clearly seen in the portraits that have been preserved, e.g. For example, in a painting by Antoine Dieu of the wedding of the Duke of Burgundy to Marie Adelaide of Savoy on December 7, 1697, where on the right behind Monsieur a fat Liselotte stands, surrounded by ladies-in-waiting and her son.

In September 1700, she complained to her aunt Sophie: "Being a Madame is a great craft, if I could sell it like the batches here in the country, I would have already carried it for sale". Sophie, who herself grew up in comparatively modest circumstances in exile in Holland, commented on her niece's lamentations in 1688 in a letter to her (rather poor) half-brother Karllutz: “Madame also has her worries, but in the position she is in She has enough to comfort herself with. ”When Sophie was declared heir to the British throne by the Act of Settlement in the spring of 1701 , Liselotte (who would have had priority if she had not become Catholic) commented on this on May 15 in a letter to her half-sister Louise: “I would rather be elector than king in England. The English humor and their parliament are not my thing at all, treat ma aunt better than me; she will also know how to deal with them better than I would have. "

widow

Late period of Louis XIV.

When Monsieur died unexpectedly on June 9, 1701, he only left debts, and Liselotte wisely renounced the common property. In his will, which was published publicly in the Mercure gallant and the Gazette d'Amsterdam , he did not mention them with a single word. Liselotte burned the love letters he had exchanged with his lovers with her own hands, so that they would not fall into the hands of the notaries: "... in the boxes I looked up all the letters, so the boys wrote to him, and burned them unread so that they didn't get into others would like to come. ”She wrote to her aunt Sophie:“ I must confess that I was much more saddened than I am if Monsieur s (eelig) did not anger me so much officien (ie 'evil services') with him The king would have always had so many worthless boys rather than me… ”Her attitude towards the deceased's mignons was no longer prudish, but rather serene: When she was reported in 1702, the Earl of Albemarle , lover of the English who had just died King Wilhelm III. from Orange , almost died of heartache, she remarked dryly: "We have not seen such friendships here with my lord ..."

Shortly after the death of her husband, there was also an attempt at reconciliation between Liselotte and Madame de Maintenon and the king. She said frankly to him: "If I hadn't loved you, then I would not have hated Madame de Maintenon so much, precisely because I believed she was robbing me of your favor." On this occasion, Maintenon was not ashamed to intercept Liselotte's letters to pull out of the sleeve, which were brimming with abuse of the mistress, and to read them with relish. The harmony between the two women did not last very long either, and Liselotte was “more tolerated than loved” after her initial benevolence. Except on official occasions, she was only rarely admitted to the innermost circle around the king. She was punished with contempt above all by Maria Adelaide of Savoy , Monsieur's granddaughter from the first marriage and granddaughter-in-law of the king, who was a spoiled child, but an outspoken favorite of the monarch and his mistress.

After Monsieur's death, Liselotte lived in his former apartment in Versailles and took part in visits to the court in Marly or Fontainebleau , where she also had her own apartments. At least she was allowed to take part in the court hunts, in which she and the king no longer sat on horseback, but together in a carriage , from which they shot, chased dogs or raised falcons. From then on Lieselotte avoided the Palais Royal and St. Cloud Castle until 1715 in order not to be a burden to her son and his wife. She did not value her somewhat remote widow's residence, Montargis Castle , and rarely went to it; but she kept it in case the King should tire of her presence at Versailles, which the Maintenon endeavored to work towards:

"... She (Madame de Maintenon) brusquises me every day, lets me take away the bowls I want to eat at the king's table in front of my nose; when i go to her, she looks at me through an axel and says nothing to me or laughs at me with her ladies; The old woman orders that express, hoping I would get angry and amport myself so that they could say they couldn't live with me and send me to Montargis. But I notice the farce, so just laugh at everything you start and don't complain, don't say a word; but to confess the truth, so I lead a miserable life here, but my part is settled, I let everything go as it goes and amuse myself as best I can, think: the old one is not immortal and everything ends in the world; They won't get me out of here except through death. That makes her despair with malice ... The woman is horribly hated in Paris, she is not allowed to show herself there in public, I think she would be stoned ... "

Régence

In the autumn of 1715, after the death of Louis XIV, who at least said goodbye to Liselotte with noble compliments, the Régence began and her son Philippe II. D'Orléans was named for the still underage King Louis XV. Regent of France. Liselotte was again the first lady in the state. It had been at least officially once before, after the death of Maria Anna of Bavaria on April 20, 1690, the wife of the Great Dauphin Ludwig , until the marriage of Dauphin Ludwig (Duke of Burgundy) to Maria Adelaide of Savoy on December 7th 1697.

The court at Versailles dissolved until the new king came of age, as the deceased had ordered, and Liselotte was soon able to return to her beloved Saint-Cloud, where she from then on spent seven months of the year, with her old ladies-in-waiting keeping her company : the "Marschallin" Louise-Françoise de Clérambault and the German Eleonore von Rathsamshausen born. from Venningen . She didn’t like to spend the winter because of the bad Parisian air from the smoke from many chimneys (and “because in the morning you can only smell empty night chairs and chamber pot”) as well as bad memories of her marriage in the Palais Royal, where you too Son resided: “Unfortunately I have to go back to morose Paris, where I have little rest. But one must do one's duty; I am in the Parisian grace that it would sadden you if I should no longer live there; must therefore sacrifice several months to the good people. They deserve (it) from me, prefer me to their born princes and princesses; They curse you and give me blessings when I drive through town. I also love the Parisians, they are good people. I love it myself that I hate your air and home so much. "

Although she had made it her policy not to interfere in politics, only a month after the king's death she successfully campaigned for the release of Huguenots who had been sent to the galleys for many years because of their beliefs . 184 people, including many preachers, were released; two years later she managed to get 30 galley prisoners released again.

However, she did not feel the relieved sigh of relief that went through the country after the 72-year rule of the “Sun King”; she “was unable to decipher the signs of the times; she saw nothing but the decline and decline of morality, where in reality a new society was born, lively, irreverent, eager to move and live freely, curious about the joys of the senses and the adventures of the spirit ”. For example, she strictly refused to receive visitors who were not properly dressed in courtly robes: “Because the ladies cannot resolve to put on body pieces and to lace up ... over time they will pay dearly for their laziness; because compt once again a queen, you will all have to be dressed like before this day, which will be an agony for you ”; - “You don't know what the farm was.” “There is no farm in all of France. The Maintenon invented that first; for, as you have seen that the king does not want to declare you before the queen, she has ( prevented) the young dauphine from keeping a court, as (o) in her chamber, where there is neither rank nor dignity; yes, the princes and the dauphines had to wait for this lady at her toilet and at the table on the pretext that it was a game. "

Most of all, they were worried about the intrigues and conspiracies against their son. She loathed its foreign minister and later prime minister, Father Guillaume Dubois (cardinal from 1721); She mistrusted the economist and chief financial controller John Law , who caused a currency devaluation and speculative bubble ( Mississippi bubble ): "I wanted Laws to come to Plocksberg with his art and system and never come to France." As a spiritual advisor she valued two staunch supporters of the Enlightenment : Archbishop François Fénelon, who fell out of favor under Louis XIV, and her temporary confessor, Abbé de Saint-Pierre . Etienne de Polier de Bottens, a Huguenot who had followed her from Heidelberg to France, also played a special role as confidante and spiritual advisor. The Duke of Saint-Simon , friend of the regent and member of his Regency Council, described the period of the reign in detail in his famous memoirs. Liselotte, long a marginal figure at court, as the regent's mother, was suddenly a point of contact for many. However, she by no means appreciated this role change:

“... Freylich I like to be here (in Saint-Cloud) , because I can rest there; In Paris one neither rest nor rest, and if I am to say it in good Palatinate, then I am called too badly to Paris; he brings you a placet, the other plagues you to speak before him (for him) ; this one demands an audience, the other wants an answer; Sum, I can't stand the way I'm tormented there, it's worse than never, I drove away with joy, and one is quite astonished that I am not entirely charmed by these hudleyen, and I confess that I am completely is unbearable. ... "

“… What leads me most into the shows, operas and comedies is to do the visits. When I'm not fun, I don't like to speak, and I am at rest in my lies. If I don't like the spectacle, I sleep; sleep is so gentle with the music. ... "

However, Liselotte was definitely interested in opera and theater and followed their development over decades, and was also able to recite long passages by heart. She was very well read, as evidenced by many of her letters, and had a library of more than 3,000 volumes, including not only all the popular French and German novels and plays of the day ( Voltaire dedicated his tragedy Oedipe to her ), but also most of the classic ones Greek and Latin authors (in German and French translation), Luther Bibles, maps with copperplate engravings, travel reports from all over the world as well as the classics of natural history and medicine and even mathematical works. She amassed an extensive coin collection, mainly of antique gold coins (the 12,000 copies her father had inherited in Kassel, not her father), she owned 30 books on coin studies and corresponded with Spanheim and other numismatists. She also bought three of the recently invented microscopes with which she examined insects and other things. So she spent her days not only at court gatherings and writing letters, but also reading and researching. Her son inherited her collections as well as his father's art collection, but the little-interested grandson Louis d'Orléans was to dissolve them and scatter them to the wind.

In June 1722 she visited Versailles for the last time, where the 12-year-old king had just moved with his 4-year-old Spanish bride Maria Anna Viktoria ; In the dying room of Louis XIV she came to tears: "So I have to admit that I can't get used to seeing nothing but children everywhere and nowhere the great king whom I loved so dearly."

Liselotte von der Pfalz, Duchess of Orléans, died on the morning of December 8, 1722 at 3:30 a.m. at Saint-Cloud Castle. Her son mourned her deeply, but only a year later he was to follow her to the tomb of Saint-Denis . He did not take part in the memorial mass on March 18, 1723. In the funeral sermon she was described as follows:

- “… I don't know anyone who was so proud and generous and yet by no means haughty; I don't know anyone who was so engaging and amiable and yet by no means slack and powerless; a special mixture of Germanic size and French sociability made itself known, demanded admiration. Everything about her was dignity, but graceful dignity. Everything natural, unsophisticated and not practiced. She felt what she was and she let the others feel it. But she felt it without arrogance and let the others feel it without contempt. "

Saint-Simon found them:

- "... strong, courageous, thoroughly German, open and downright, good and benevolent, noble and great in all her demeanor, but incredibly petty as to the respect she deserves ..."

The letters

Liselottes' numerous letters established her fame. In total, she is said to have written an estimated 60,000 letters, 2/3 in German and 1/3 in French , of which about 5000 have survived, about 850 of them in French. With this she surpasses the second great letter writer and contemporary witness of her epoch, the Marquise de Sévigné with her approximately 1200 received letters.

The letters deal with all areas of life, they contain vivid descriptions of court life with relentless openness and often in a mocking, satirical tone, as well as numerous reminiscences of her childhood and youth in Germany, the latest court gossip from all over Europe, which she often comments on in witty comments, reflections on literature and theater, about God and the world; The letters always fascinate with their linguistic freshness. Every day Liselotte sought relief by writing long letters to her relatives in Germany. The constant exchange became a cure for her inner melancholy and sadness , to which she was exposed due to her depressing life experiences. Maintaining the German language, also by reading books, meant a piece of home and identity for her in a foreign country.

Your German letters are next to dialect sprinkles with numerous French words and z. Partly mixed whole passages in French, e.g. B. when she replays conversations with Louis XIV, with her husband Philippe or other people. Johannes Kramer describes her letters as "the best-studied example of the use of the Alamode language in private letters between members of the high nobility" Liselotte tended to use coarse formulations, which was not unusual in letters from princely persons of the 16th and 17th centuries, but she did Helmuth Kiesel's view had gone extraordinarily far in this, to which a psychological disposition, the frivolous tone in the Palais Royal and perhaps also the Luther 's polemics, which she was familiar, had contributed; in any case, their tone differed greatly from the preciousness of the Parisian salons of their time, and also from the naturalness of the German bourgeois lettering style of the 18th century, as shaped by Christian Fürchtegott Gellert . She liked to make striking comparisons and often interwoven proverbs or appropriate sentences from plays. Her favorite saying (and life's motto) is often quoted: "What cannot be changed, let go as it goes."

Unlike Madame de Sévigné, she did not write for the public of a small circle, but only to the respective correspondent, in concrete response to their last letter, which explains the almost unbridled spontaneity and unrestricted intimacy of the style. She didn't want to write a high style , not even romanesque , but natural, coulant, without façon , above all without ceremonial ado: writing comfortably is better than correct . The letters often appear to have no disposition and are subject to spontaneous ideas, whereby they make the reader a living companion ( WL Holland ).

Most of the letters received are addressed to her aunt Sophie von Hannover , who wrote them twice a week. The strong personality of this aunt offered her support in all difficult life situations; Liselotte had also shaped the atmosphere of the Welfenhof with her scientific and literary interest, her religious tolerance thinking and the preservation of morality and concepts of virtue with all due consideration for human inadequacies, for life. After Sophie's death in 1714, she complained: “This dear Electress was (elig) all my consolation in all the disparaging things, when it happened to me so often; whom i il s. (Blessed of your loved ones) complained and wrote against received from her, I was consoled against utterly consoled. "Sophie, however, who had been of a cooler and more calculating nature than her emotional niece, had commented on their letters:" Madame writes very long, but there is not usually a lot of important information to be found ... "

Liselotte's half-sister Luise subsequently became an inadequate replacement for the revered and admired aunt . She had also written regularly to her half-sister Amalie Elisabeth (Ameliese; 1663–1709). She also remained in lifelong contact with her Hanoverian governess Anna Katharina von Offen , the chief stewardess of the Electress Sophie, and with her husband, the chief stable master Christian Friedrich von Harling .

Her weekly (French) letters to her daughter, the Duchess of Lorraine, burned in a fire on January 4, 1719 in the castle of Lunéville , the country residence of the Lorraine dukes. In the later period, the wife of the British heir to the throne and later King George II , Caroline von Brandenburg-Ansbach , also became an important correspondent, although they never met; she had grown up as an orphan with Electress Sophie's daughter Sophie Charlotte of Prussia and in 1705 Sophie married her grandson Georg. From her Liselotte learned all the details about the family quarrel at the English court. She also wrote regularly with the sister of George II and granddaughter of the Electress Sophie, the Prussian Queen Sophie Dorothea . Numerous letters to other relatives and acquaintances have also been received, including to Anton Ulrich von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel and his librarian Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz , who had previously been in the service of Ernst August and Sophie for a long time.

Her most frank letters are those which she did not send by post, but which she was able to give to travelers to Germany. In letters like this she doesn’t mince her words and vent her heart when Monsieur’s favorites in the Palais Royal tyrannize her or the Maintenon. She knew that the Black Chamber opened its letters to copy critical passages and translate them; hence, she sometimes even incorporated derisive remarks addressed directly to the government, particularly to its favorite enemy, Foreign Secretary Colbert de Torcy .

She describes her stylistic principles in a letter to her half-sister Ameliese: “Just continue, always naturally and without writing façon! Because I can't take compliments at all. God wish you could write me something so that I could make me laugh! ... The stupidest people in the world can keep a compliment and write, but talking about everything and having a coulant style is rarer than you might think ... "She disliked the pompous baroque style that has become fashionable:" Me I think everything in Germany has changed so much in the 50th year that I'm in France that it precompenses me like another world. I've seen letters ... so I struggle to understand. In my day it was thought to be written when the phrases were briefly understood and you said a lot in a few words, but now you think it's nice when you put a lot of words around them, they mean nothing. I do not care, but thank God all those with whom I correspond have not accepted this disgusting fashion; I couldn't have answered ... "

To characterize the nature of her correspondence, she uses the term “chat”: for the duration of a letter (which usually consisted of 15 to 30 folded sheets of gold-edged, which she described with large, energetic handwriting), she lingered in her mind those she liked, but who lived far away to talk to them casually. Her biographer Dirk Van der Cruysse says: "Had Madame lived in our time, she would have spent her days on the phone." But thanks to her letters, we have a unique panorama of court life in the Baroque period and a vivid picture of her personality (and many others ) preserved. Their descriptions are often less precise, but far more colorful and humorous than those of the Marquis de Dangeau , whose court diary and memoir made him the official chronicler of the reign of Louis XIV. Nevertheless she wrote without literary ambitions and not for posterity either: “I write as I speak; because I am too natural to write before I think about it. ”After answering, she burned the letters she received herself, and assumed that the same thing happened to her letters; Fortunately, just under a tenth escaped this.

Quotes

"... I've been ugly all my life, so I couldn't take the liberty of looking at my bearcat monkey face in the mirror, so it's no wonder that I haven't looked at myself often."

“I have not found (my daughter) changed much, but her master (husband) is abhorrent. Before this he was with the most beautiful colors, and now he is completely reddish brown and thicker than my son; I can say that I have so fat and fat children that I am myself. "

"... If it is true that you will become a virgin again if you have not slept with a man for long years, then I must have become a virgin again, because at the age of 17 my lord and I did not sleep with each other, but we liked, umb Knowing it will not fall into the hands of the gentlemen Tartars . The Tartars have to hold more of the feeling than of the face in the 5 senses because they prefer old women to young women. ... "

"... How I (as a child) in the Hague with IL (= your lovers, what is meant is the later English King Wilhelm III of Orange ) and met verlöff met verlöff ( Low German : with all due respect ) in my hembt shit, I thought I didn't want to that he would cut such a great figure one day; if only his big hits are not sealed like I sealed the game back then; but if it were to happen and peace would come about as a result, I would really want to be satisfied ... "

"... For it has been known to me all my life to be a woman, and to be elector, forbid me to tell the truth, better be aware than to be madame; but if god's sake didn't know it, it is unnecessary to think about it ... "

“I would prefer to be a rich ruling imperial count with his freedom, rather than an enfant (king's child of France) , because we are nothing but crowned slaves; I would be suffocated if I hadn't said this ... "

"... that makes me bleed heartily, and if you still think I'm sick that I'm sad about it, ..."

"... I believe that Mons. de Louvois burns in that world because of the Palatinate; he was terribly cruel, nothing could complain ... "

"... As EL now describe the teutsche court to me, I would find a big change in it; I think more of German sincerity than of magnificence and I am quite happy to hear that such is lost in fatherland. It is easy to see what the luxe chases away the good-heartedness from; you cannot be magnificant without money, and if you ask so much about money you become interested, and once you become interested you seek out all the means to get something, which then breaks down falsehood, lies and deceit, which then faith and sincerity quite chased away. ... "

“… I have no ambition, I don't want to rule anything, I wouldn't find any pleasure in it. This is some (own) thing for french women ; no kitchen maid here believes that she has insufficient understanding to rule the whole kingdom and that she is being done the greatest injustice in the world not to consult her. All of that made me feel very sorry about ambition; for I find such a hideous ridicul in this that I dread it. ... "

"... There are a lot of royal persons, if one was brought up badly and spoiled in their youth, only learned their grandeur for them, but not because they are only people like others and are to be valued in front of nothing with all their grandeur, if they are have no good temper and strive for virtue. I once read in a book that they are compared to pigs with gold collars. That struck me and made me laugh, but that's not bad. ... "

“… I cannot live without doing nothing; arbeyten I can still go crazy, chatting at all times would be unbearable for me ... I can't read all the time either, my brain is too confused ... writing amuses me and gives my sad thoughts distraction. So I will not interrupt any of my correspondence, and whatever you may say, dear Louise, I will write to you all on Thursdays and Saturdays and to my dear Princess of Wallis on Tuesdays and Fridays. I love writing be a arzeney before me; for she writes so well and so pleasantly misses that it is a real pleasure to read and answer IL writing; that diverts me more than the spectacular ... My smallest letter, as I write in the whole week, is to the queen in Spain ... and it gives me more trouble than all the other letters ... I stay on compliments must answer, which I have never been able to take ... It could easily be that the Princesses of Wallis could be content to have my silly letters only once a week and to write only once; But that doesn't suit me at all, so I'll continue as I've done so far. ... "

"... This morning I find out that old Maintenon died, yesterday evening between 4 and 5 o'clock. It would be very lucky if it happened 30 years ago. ... "

“… Believe me, dear Louise! The only difference between the Christian religions is that of priests, whatever they may be, Catholic, Reformed or Lutheran, they all have ambitions and all Christians want to make each other hate because of the religion, so that they may be needed and they may rule over the people . But true Christians, god done the grace to love him and virtue, do not turn to the priesthood, they follow God's word as well as they understand it, and the order of the churches in which they find themselves leave that Constraint the priests, superstition the mob and serve their god in their hearts and seek not to offend anyone. This is as far as God is concerned, on the whole you have no hatred of your negatives, whatever religion he may be, seek to serve him wherever you can and surrender entirely to divine providence. ... "

“... If one were not persuaded that everything was planned and not to end, one would have to live in constant agony and always think that one had to reproach oneself for something; but as soon as one sees that God Almighty has foreseen everything and nothing history, as what has been ordained by God for so long and at all times, one must be patient in everything and one can be satisfied with oneself at all times, if, what one does, in good opinion history; the rest is not with us. ... "

reception

In 1788, some longer excerpts from the letters appeared for the first time - under unexplained circumstances - initially in a French translation, then a few years later in the German original, under the title Anecdotes from the French Court, especially from the times of Ludewig XIV. And the Duc Regent . During the French Revolution , it was believed that Liselotte was a key witness to the depravity and frivolity of the Ancien Régime . This chronique scandaleuse was all the more popular in Germany when the editors of the letters succeeded in portraying the author as an upright and morally-minded German princess in the midst of the depraved and frivolous French court life, especially since she herself always demonstrated her German nature to the French courtiers had turned out. In her aversion to the French way of life (and cuisine!), In her enthusiasm for everything German (and especially Palatinate), she not only followed personal preferences, but also followed the pattern of anti-French criticism of Alamode in German literature of the 17th century. Even after 40 years in France, when she wrote “with us” she always meant her old home.

In 1791 a new, anonymously edited selection of letters appeared under the title Confessions of Princess Elisabeth Charlotte of Orleans . The good, honest, German woman - without all the pampered and creeping court sensibilities, without all the crookedness and ambiguity of the heart - was portrayed as the representative of the old German, honest times of earlier centuries, to which the German courts had to return when a revolution should be prevented in Germany. The Duchess of Orléans thus became a figure of considerable cultural patriotic importance.

Friedrich Karl Julius Schütz published a new selection in 1820, he too emphasized the “strong contrast between the truly old German simplicity, loyalty, honesty and efficiency ... to the glamor, opulence, etiquette and gallantry, such as the unlimited intriguing spirit and the the whole, systematically developed frivolity and hypocrisy of this court, for a full half a century ... “In contrast to the anonymous publisher of the Confessions of 1791, however, Schütz appeared to be so far removed from that moral corruption that all anti-court declamations by the liberals deprived of any authorization; But not all German writers of his time shared this view, as can be read in Georg Büchner's Hessian Landbote .

“In the further course of the 19th century the letters lost their immediate political relevance, but because of their cultural and historical significance and their German-style usability, they found committed editors and a broad audience.” Also Wolfgang Menzel , who wrote a volume of letters to his half-sister Louise in 1843 published, saw in the Duchess the simple German woman and the most open soul in the world , who "only had to watch too much moral corruption ... understandable that she sometimes expresses herself about it in the crudest words" . From then on, the letters were gladly used in the anti-French demeanor of increasing German nationalism. Liselotte was stylized as a martyr of the French court and elevated to a national cult figure, for example in Paul Heyse's play Elisabeth Charlotte from 1864. Theodor Schott and Eduard Bodemann also struck the same note . However, the historicism also recognized the enormous cultural and historical value of the letters, and extensive editing activities began in the editions of Bodemann and Wilhelm Ludwig Holland .

Fashion (palatine)

The so-called palatine is named after Liselotte von der Pfalz , a short cape or turn-down collar trimmed with fur, which women use to protect the cleavage and neck from the cold in winter . Originally, she was laughed at at the French court because of her "old" sable that she wore when she arrived from Heidelberg, but since she was very popular with the king in the 1670s, she was loved by the ladies in the unusually cold winter of 1676 imitated. This is how a women's fashion accessory that has been valued for centuries was created.

When Liselotte wanted to put on her old sable again in November 1718 to see a performance of Voltaire's Oedipe , to which she was dedicated, she found that it had been eaten away by clothes moths . But she took the opportunity to examine the moths under the microscope the next day.

- Doubtful portraits of Liselotte von der Pfalz

family

origin

expenditure

- Annedore Haberl (Ed.): Liselotte of the Palatinate. Letters. Hanser, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-446-18794-4 .

- Hannelore Helfer (ed.): Liselotte von der Pfalz in her Harling letters. Hahnsche Buchhandlung, Hannover 2007, ISBN 978-3-7752-6126-5 .

- Hans F. Helmolt (Ed.): Letters from Duchess Elisabeth Charlotte of Orleans. Leipzig 1924.

- Heinz Herz (Ed.): Letters from Duchess Elisabeth Charlotte von Orléans to her siblings. Leipzig 1972.

- Helmuth Kiesel (Ed.): Letters from Liselotte from the Palatinate. Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-458-32128-4 .

- Carl Künzel (ed.): The letters of Liselotte of the Palatinate, Duchess of Orleans. Langewiesche-Brandt, Ebenhausen near Munich 1912.

- Hans Pleschinski (ed.): Liselotte from the Palatinate. Your letters. Read by Christa Berndt. Kunstmann, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-88897-371-6 .

literature

- Dirk Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft. Liselotte of the Palatinate. A German princess at the court of the Sun King. From the French by Inge Leipold. 7th edition, Piper, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-492-22141-6 .

- Peter Fuchs: Elisabeth Charlotte. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 4, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1959, ISBN 3-428-00185-0 , pp. 448-451 ( digitized version ).

- Arlette Lebigre: Liselotte from the Palatinate. A Wittelsbacherin at the court of Ludwig XIV. Claassen, Düsseldorf 1988, ISBN 3-453-04623-4 (reprint Heyne, Munich 1991).

- Sigrun Paas (Ed.): Liselotte from the Palatinate. Madame at the court of the Sun King. HVA, Heidelberg 1996, ISBN 3-8253-7100-X (catalog for the exhibition in Heidelberg Castle).

- Marita A. Panzer: Wittelsbach women. Princely daughters of a European dynasty. Pustet, Regensburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-7917-2419-5 , pp. 108-121.

- Ilona Christa Scheidle: Writing is my biggest occupation. Elisabeth Charlotte von der Pfalz, Duchess of Orléans (1652–1722) . In: Dies .: Heidelberg women who made history. Munich 2006, ISBN 978-3-7205-2850-4 , pp. 27-39.

- Mareike Böth: Narrative ways of the self. Body practices in Liselotte's letters from the Palatinate (1652–1722) (= self-testimony of modern times. Volume 24). Böhlau, Cologne / Vienna / Weimar 2015, ISBN 978-3-412-22459-2 .

Drama and film

- 1932: Liselott 'von der Pfalz - Singspiel by Richard Keßler , music by Eduard Künneke , performed 2004/2005 in Heidelberg

- 1935: Liselotte von der Pfalz - UFA film, director and screenplay: Carl Froelich , literary source: Rudolf Presber (1868–1935)

Actors were Dorothea Wieck (Mme. De Maintenon), Hans Stüwe (Duke of Orléans), Renate Müller ( Liselotte von der Pfalz), Maria Meissner (Marquise de la Vallière), Maria Krahn (Elector Karl Ludwig's wife), Eugen Klöpfer (Elector Karl Ludwig von der Pfalz), Hilde Hildebrand (Princess de Montespan), Michael Bohnen (King Ludwig XIV. ), Else Ehser (Maria Theresia) - 1966: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Director: Kurt Hoffmann

Actors were Heidelinde Weis (Liselotte von der Pfalz), Harald Leipnitz (Duke of Orléans), Karin Hübner (Princess Palatine), Hans Caninenberg (King Ludwig XIV.), Erwin Linder (Elector Karl Ludwig von der Pfalz), Gunnar Möller (Duke of Courland), Robert Dietl (Lorraine), Joachim Teege (Abbé), Else Quecke (Frau von Bienenfeld), Karla Chadimová (Paulette).

Web links

- Literature by and about Liselotte von der Pfalz in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Liselotte von der Pfalz in the German Digital Library

- Liselotte von der Pfalz in the Internet Archive

- Liselotte of the Palatinate. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations).

- Works by Liselotte von der Pfalz in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Liselotte von der Pfalz , Virtual Library - History of the Electoral Palatinate, Institute for Franconian-Palatinate History and Regional Studies at Heidelberg University

- Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz - digital , Heidelberg University Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ Sigrun Paas: The 'bear-cat monkey face' of Liselotte von der Pfalz in her portraits. In: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King. Universitätsverlag C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, pp. 65-93; here p. 92.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 229.

- ^ Sigrun Paas: The 'bear-cat monkey face' of Liselotte von der Pfalz in her portraits , in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Press C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, pp. 65–93: here pp. 65–67 .

- ↑ Sigrun Paas (Ed.): Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Press C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, pp. 33–34

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 66f

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 64

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 39-61

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 103f.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 251-254, here: 252. Also pp. 349-350

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 52-58, pp. 56-58, pp. 67-68.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 68-73

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 92

- ↑ Sigrun Paas (Ed.): Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Press C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, pp. 52–59

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 76-81, p. 89.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 77.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 79.

- ↑ To Georg: Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 82-83.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 90.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 88ff.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 94-95

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 98-99

- ↑ Sigrun Paas (Ed.): Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Press C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, pp. 33–34

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 84-85

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 99

- ↑ In a letter to Electress Sophie dated May 23, 1709, she describes a conversation with her confessor, who wanted to "convert" her to the veneration of saints.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 96-97

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 116.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 141.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 139-140.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 142-145.

- ↑ Liselotte said, of course, that he was almost certainly never in love with a woman, with men he was (author's note).

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Madame sein ist ein ellendes Handwerck , 3rd edition 1997. pp. 143 and pp. 208–209, sources on pp. 676 and 679. (Van der Cruisse provides the quotation incompletely at both of the text passages mentioned. The two Excerpts have been added together here).

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 153-158.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 203ff., 209.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 453.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 156.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 155.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 219.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 153-202.

- ↑ The memoirs of the Duke of Saint-Simon . Ullstein, Frankfurt-M. 1977, ISBN 3-550-07360-7 , Vol. 1, p. 285

- ↑ Gilette Ziegler (ed.): The court of Ludwig XIV. In eyewitness reports , dtv 1981, pp. 64–83 and p. 193

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 175-180.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 180.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 180.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 200.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 199-200.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 198-200.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Madame sein ist ein ellendes Handwerck , 3rd edition 1997. p. 206, source on p. 679

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Madame sein ist ein ellendes Handwerck , edition 1990, p. 216

- ↑ Quotation from a letter from the Grande Mademoiselle in: Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 146.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 208-216, also p. 218.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 215.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 204.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 214.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Madame sein ist ein ellendes Handwerck , 3rd edition 1997. p. 206, source on p. 679

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 217.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 217.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 147-148.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 215 (Sophie to Karl Ludwig, November 9, 1679).

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 292.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 226 ff

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 226

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 287-300.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Madame is a great craft, pp. 292–296.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 289-299.

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 109 (letter to Electress Sophie dated March 7, 1696)

- ↑ Gilette Ziegler (ed.): The court of Ludwig XIV. In eyewitness reports , dtv 1981, pp. 192–199, here: p. 195

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 189.

- ^ Gilette Ziegler (ed.): The court of Ludwig XIV. In eyewitness reports , dtv 1981, pp. 194-195

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 186-188.

- ↑ Gilette Ziegler (ed.): The court of Ludwig XIV. In eyewitness reports , dtv 1981, p. 192

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 188-191.

- ↑ Gilette Ziegler (ed.): The court of Ludwig XIV. In eyewitness reports , dtv 1981, pp. 196–197

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 191.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 191.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 301, 307-308.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 308, pp. 445-452 (especially 450), p. 606.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 335

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 91

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 445-451.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 324-331.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 336.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 335-336.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 334-335.

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz , ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt / M., 1981, p. 222.

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz , ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt / M., 1981, p. 127f. (Letter of October 10, 1699 to the Electress Sophie).

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz , ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt / M., 1981, p. 127 (letter of September 23, 1699 to the Electress Sophie).

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 72 (letter of March 20, 1689 to Duchess Sophie).

- ^ In a letter of March 20, 1689 to her aunt Sophie von Hannover. Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 364.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 354-356, pp. 358-368.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 364–365, P. 688 (Notes)

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 367.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 382-388.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 384-385.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 385.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 385.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 386.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 397, p. 404 and p. 419 (Ezechiel Spanheim).

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 404-405, here 404.

- ↑ see file: Mariage de Louis de France, duc de Bourgogne.jpg

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 436

- ↑ Sophie's letter to Raugraf Karllutz of June 4, 1688, E. Bodemann (ed.), Letters from Electress Sophie von Hannover to the Raugräfinnen and Raugrafen zu Pfalz , 1888, p. 74

- ↑ With humor is meant the "capricious changeability" of English politics.

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 132

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 454.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 452-453.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 457.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 458.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 463.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 445-452.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 449.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 447.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 452.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 459, 460.

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 164f.

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 237 (letter to her half-sister Louise dated November 28, 1720)

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 579-581.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 336 and p. 581.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 584.

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 230 (letter to her half-sister Louise)

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 231 (letter to her half-sister Louise dated May 23, 1720)

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 233 (letter to her half-sister Louise dated July 11, 1720)

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 211.

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 218.

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . Pp. 519-535.

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 255 (letter to Herr von Harling dated July 4, 1722)

- ↑ Helmuth Kiesel (Ed.): Letters of Liselotte von der Pfalz , p. 10

- ^ Johannes Kramer: The French in Germany. An introduction. Stuttgart 1992. p. 65.

- ↑ Helmuth Kiesel, in: Letters of Liselotte von der Pfalz , 1981, introduction, p. 25.

- ^ Letter to her half-sister Raugräfin Louise dated July 24, 1714, WL Holland, Briefe, Bd. II, 401–402

- ^ Letter from Sophie to Caroline of Wales dated August 16, 1687, E. Bodemann (ed.), Letters from Electress Sophie von Hannover to the Raugräfinnen and Raugrafen zu Pfalz , 1888, p. 59

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 514.

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 123 (letter to her half-sister Ameliese dated February 6, 1699)

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, pp. 249f. (Letter to Herr von Harling dated June 22, 1721)

- ↑ Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft . P. 513.

- ↑ Sigrun Paas: The 'bear-cat monkey face' of Liselotte von der Pfalz in her portraits , in: Liselotte von der Pfalz - Madame at the court of the Sun King , University Publishing House C. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, p. 65

- ^ WL Holland, Letters from Duchess Elisabeth Charlotte von Orléans , Stuttgart / Tübingen 1867-1881, Volume III (of 6 volumes), pp. 188-189

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 105.

- ^ Eduard Bodemann (Ed.): From the letters of the Duchess Elisabeth Charlotte von Orléans to the Electress Sophie von Hannover. Hanover 1891. Volume I, page 100

- ^ WL Holland, Letters from Duchess Elisabeth Charlotte von Orléans , Stuttgart / Tübingen 1867-1881, Volume I (of 6 volumes), p. 225

- ^ Eduard Bodemann (Ed.): From the letters of the Duchess Elisabeth Charlotte von Orléans to the Electress Sophie von Hannover. Hanover 1891. Volume II, pages 253-254

- ^ Eduard Bodemann (Ed.): From the letters of the Duchess Elisabeth Charlotte von Orléans to the Electress Sophie von Hannover. Hanover 1891. Volume I, page 101

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 164.

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 91.

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 224.

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 226.

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 240ff.

- ^ Letters from Liselotte von der Pfalz, ed. v. Helmuth Kiesel, Insel Verlag, 1981, p. 218.