Megalithic in Saxony-Anhalt

The Megalithic occurred during the Neolithic period almost the entire territory of Saxony-Anhalt on. About 500 large stone graves are known, of which 167 have been preserved. The plants are concentrated in several regions, with the main focus being on the Altmark and the Börde district in the north of the country. In the south there are only a few megalithic grave forms. In Saxony-Anhalt megalithic buildings were of several cultures built and used, according to the region by the Nordic megalith architecture of the Beaker culture (TBK) or by the architecture in Hesse , Lower Saxony and Westphalia -based wartberg culture were affected.

Research history

Antiquarian investigations

The first mention of megalithic stone graves in the area of Saxony-Anhalt can be found in the Dutch archeologist Jacobus Tollius , who referred to graves near Magdeburg in a letter from 1687 without giving any further details.

The first more detailed descriptions and illustrations of large stone graves go back to Johann Christoph Bekmann . In his “Historie des Fürstenthums Anhalt” , published in 1710, he goes into megalithic systems between Bernburg and Köthen and the neighboring areas, including the large stone grave Drosa and the Gehrden megalithic bed . In 1751 the “Historical Description of Chur and Mark Brandenburg” , which he had begun and completed by his great-nephew Bernhard Ludwig Bekmann , was published . In this publication, 36 large stone graves in the Altmark were described in detail for the first time and twelve of them were depicted. For the first time, there is also a subdivision of the graves into giant beds or heather beds and “grave altars” without surrounding stone circles.

The first surviving examinations of large stone graves took place at the end of the 1720s. In 1728, Governor Wilhelm Ludwig von dem Knesebeck had several graves opened in the area around Bierstedt in Altmark . However, there is only a brief report about these activities, which was written several years later and from which there is no more information than that some remains of bones and decorated shards were found in the burial chambers. The report about an excavation at the large stone grave Grimschleben 1 ("Heringsberg") near Nienburg in 1729 is more detailed. In addition to a multi-page description of the grave and the finds made in it, there is also a sketch of the burial chamber.

An important document for the Jerichower Land is a chronicle by Pastor Joachim Gottwalt Abel from Möckern , from the second half of the 18th century. He names over forty graves, of which only three still exist.

The beginning of scientific archeology

The first scientific occupation with the Altmark graves took place in the 1830s. Thanks to financial support from the Prussian authorities, Johann Friedrich Danneil , school director from Salzwedel , was able to travel across the whole of the Mark and record its inventory of graves. He carried out excavations on six graves. He was very disappointed with the finds, mostly only broken pieces and individual flint tools , and described them as "insignificant". At least they allowed him a rough chronological classification. Since he had not found any metal objects in them, he correctly concluded that they must belong to the Stone Age and are therefore older than the Bronze Age and Iron Age burial mounds .

Research in the late 19th and early 20th centuries

A new recording of all Altmark graves took place in the 1890s by Eduard Krause and Otto Schoetensack . In their report they listed 190 graves, of which only 50 existed at the time of their investigation. This number has not changed significantly; the greatest destruction had already taken place at the time of the investigations by Krause and Schoetensack. One of the last completely destroyed graves was in Kläden . As in many other places in the Altmark, its remains were used to erect a war memorial after the First World War .

Little happened in the following years. A few more descriptions followed, which were limited to parts of the Altmark, as well as some emergency excavations. An important research contribution comes from Paul Kupka , who systematically evaluated the ceramics found in the graves for the first time in the 1920s and was thus able to establish a connection between the large stone graves and the Altmark group of deep engraving ceramics , which at the time he called long grave ceramics . In 1938 and 1939, under the direction of Ulrich Fischer , excavations were carried out at three large stone graves in Leetze , although these were only described in a brief six-page report.

Research was limited to smaller areas south of the Altmark. In 1905 an excavation took place at the large stone grave Drosa. From 1896 onwards there were efforts to systematically record all graves between Haldensleben and Marienborn . The first publications on this come from Philipp Wegener and Wilhelm Blasius . In 1935, Karl Stuhlmann drew up an overall plan that was never published.

Megalithic research in the GDR

After the Second World War , there were only a few studies of large stone graves in the area of Saxony-Anhalt. While Ewald Schuldt excavated over 100 megalithic structures in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania in the 1960s, only a few in the Haldensleber Forest were explored by Friedrich Schlette and Joachim Preuss in Saxony-Anhalt .

Efforts were also made to compile a complete list of the megalithic stone graves in Saxony-Anhalt. Building on the results of Krause and Schoetensack as well as his own measurements in the Haldensleber Forest, which were carried out before the Second World War, it was initially Ernst Sprockhoff who wanted to add a volume on Saxony-Anhalt to his "Atlas of Germany's Megalithic Tombs", published between 1966 and 1975. Because of the war-related loss of his records and the division of Germany, this project failed. Further documentation of the facilities in the Haldensleber forest by E. and W. Saal, Dieter Kaufmann and Erhard Schröter served the renewed attempt at an overall representation; however, no publication came about. An additional difficulty was the fact that the graves at Marienborn were located in the restricted military area due to the division of Germany.

Research since 1990

In 1991 Hans-Jürgen Beier was able to present a list of all the megalithic stone graves in Eastern Germany for the first time in his habilitation thesis. Little happened in relation to megalithic research in the course of the 1990s. It was not until 2003 that a new inventory of the graves in the Altmark was carried out under the direction of Hartmut Bock , Barbara Fritsch and Lothar Mittag . Here, 47 known graves were systematically measured and another newly discovered. This recording was followed by an excavation project by the University of Kiel , in which the Lüdelsen 3 grave was excavated in 2007 and the Lüdelsen 6 grave under the direction of Denis Demnick from 2009 to 2010 . Another research project began in 2009 in the Haldensleber Forest. The graves that are particularly numerous here are to be explored in connection with neighboring settlements and trench works .

Grave types

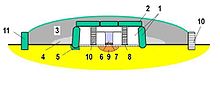

Various megalithic forms occur in Saxony-Anhalt, which are distributed differently from region to region. In the north, dolmens and the passage graves dominate . Dolmens are above-ground, originally overhanging grave complexes that have access on the narrow side. The oldest form is the ancient dolmen , which usually only have a capstone and a pair of wall stones that were built on their sides. The polygonal dolmen is similar to the Urdolmen , which also has only one capstone, but more than four wall stones standing on its smallest surface, which gives the chamber with an access a polygonal floor plan. Extended dolmens are characterized by standing stones in the form of mostly two pairs of wall stones, a maximum of two cap stones and one entrance. The largest variant is the large dolmen , which have three or more cap stones. A special form occurring in the Altmark are large dolmen with a short, diagonally bent corridor. One example of this is the Lüdelsen 3 grave, which was examined in 2007. This particular form of grave occurs in Schleswig-Holstein and Scandinavia and only occasionally in Mecklenburg and Lower Saxony.

Passage graves are characterized by an access to the chamber on the long side and a mostly rectangular or trapezoidal stone border around the mound.

A type of grave found in Germany only east of the Elbe are the chamberless giant beds . They have a rectangular, mostly low mound formed by megalithic blocks. There are no burial chambers or they were made with perishable material or small-sized stones. With one exception, the Gehrden Hünenbett , these facilities in Saxony-Anhalt have been destroyed.

In the Middle Elbe-Saale area, another grave type occurs: The Registered Lowered chamber grave , one as a means German Chamber designated gallery grave . It is a burial chamber that is half or fully sunk into the ground with an access on the narrow side. The Central German Chambers are similar to the gallery graves that are typical of the Hessian and Westphalian megalithics.

Very few large stone graves are known from the south and south-east of Saxony-Anhalt. Non-megalithic grave forms dominate here, but in their function as collective graves and in their shape they are strongly based on the large stone graves, whereby other materials, such as small-sized stones or wood, were used. Wall chamber graves , dry stone walls and huts for the dead are typical .

Duration

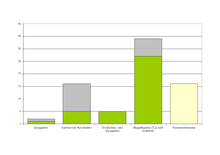

In the area of Saxony-Anhalt there are 485 systems that can be identified with certainty or with a high degree of probability as large stone graves. 167 of these have been preserved, with the degree of preservation and the state of research being very different from region to region. In addition to these secure facilities, there are also 119 field names that could refer to other large stone graves , but also to natural formations or other human legacies, such as small stone boxes or menhirs .

| Grave type | secured | supposed | receive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunken chamber graves | 3 | 5 | 6th |

| Extended dolmens | 1 | 9 | 5 |

| Large dolmen | 4th | 17th | 7th |

| Polygonal poles | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Passage graves | 22nd | 27 | 26th |

| Chamberless giant beds | 5 | 11 | 1 |

| Urdolmen | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Sunken chamber graves or wall chamber graves | 2 | 0 | |

| Large or extended dolmens | 5 | 1 | |

| Large dolmen or sunken chamber tombs | 2 | 1 | |

| Large dolmen or passage graves | 69 | 37 | |

| Large dolmen or ramp boxes | 1 | 0 | |

| Urdolmen or extended dolmens | 1 | 0 | |

| Urdolmen or stone boxes | 2 | 0 | |

| Megalithic tombs (type not determined) | 261 | 27 | 82 |

| Megalithic tombs or wall chamber tombs | 3 | 0 | |

| Megalithic tombs or stone boxes | 2 | 0 | |

| (Field name references) | (119) | - |

Regional groups

In 1991, Hans-Jürgen Beier distinguished five regional megalithic groups for the area of Saxony-Anhalt. Its subdivision was based solely on the spatial distribution of the megalithic structures. According to this, five larger concentrations of large stone graves can be made out, between which there are more or less large empty areas. These regional groups established by Beier are the Aller-Ohre group, the Altmark group, the Hercynian group, the megalithic Middle Elbe-Saale group and the East Elbe group. Within these groups, differences in the types of graves that occur can be identified, especially with increasing spatial distance.

In 2012, Barbara Fritsch and Johannes Müller presented a new regional structure that is basically similar to that of Beier's, but divides the Aller-Ohre group into the regions of Haldensleben and Magdeburg / Börde and the Hercynian group into the regions of North Harz and Halle / Naumburg . Since this new structure has not yet been worked out in more detail, the following section will focus on the structure of Beier.

The Aller-Ohre group

The Aller-Ohre group occupies a distribution area west of Magdeburg in the district of Börde . About 170 large stone graves are known from here, three concentrations can be determined. There are a particularly large number of systems in the Haldensleber Forest . Another group lies west of it between the towns of Harbke and Marienborn . A third group near Samswegen , between Wolmirstedt and Haldensleben , has been completely destroyed.

Although, in contrast to the rest of Saxony-Anhalt, only a comparatively few facilities were completely destroyed here, more precise statements on the individual grave types are still difficult, since most of the graves cannot be determined more precisely. Apparently, as in the Altmark, the passage graves dominate. Large dolmen are also more common. Several sunken chamber graves indicate relationships with the neighboring Hercynian group.

| Grave type | secured | supposed |

|---|---|---|

| Sunken chamber graves | 1 | 4th |

| Extended dolmens | - | 1 |

| Large dolmen | - | 3 |

| Passage graves | 9 | 3 |

| Large dolmen or passage graves | 21st | |

| Urdolmen or stone boxes | 1 | |

| Megalithic tombs (type not determined) | 118 | 8th |

| (Field name references) | (26) |

The Altmark Group

The Altmark group includes all graves in the Altmark area , which is divided into the Altmarkkreis Salzwedel and the Landkreis Stendal . Four subgroups can be distinguished within their distribution area: The largest is located in the west of the Altmark between the Dumme and Jeetze rivers . A second group is southeast of Salzwedel , a third northeast of Osterburg and the fourth west of Stendal .

More than 200 large stone graves are known from the Altmark area, among which the passage graves and the large dolmen dominate. In addition, there are other dolmen shapes. There are no other megalithic grave types in the Altmark. The extensive lack of older grave types, such as Urdolmen and chamberless giant beds, as well as analyzes of the ceramics found in the graves indicate that the idea of megalithic was only transported to the Altmark by immigrants from the northwest in a later phase of its development. There also seem to have been isolated influences from other regions. The large stone grave Lie is reminiscent of the “Central German Chambers” in the Hercynian area. A no longer preserved grave in Sallenthin even had similarities to the barren beds in Kujawia ( Poland ) due to its triangular enclosure .

| Grave type | secured | supposed |

|---|---|---|

| Extended dolmens | 1 | 8th |

| Large dolmen | 2 | 11 |

| Poygonaldolmen | 1 | 3 |

| Passage graves | 8th | 22nd |

| Large or extended dolmens | 5 | |

| Large dolmen or sunken chamber tombs | 1 | |

| Large dolmen or passage graves | 41 | |

| Urdolmen or extended dolmens | 1 | |

| Megalithic tombs (type not determined) | 100 | 2 |

| (Field name references) | (68) |

The Hercynian Group

The Hercynian group comprises the northern and eastern Harz foreland, the Harz and the central Saale region. The area is bordered by the Thuringian Forest in the south and the Leine and Oker rivers in the west . In the east, the distribution does not extend far beyond the Saale. The northern boundary forms a line between the Elm and the mouth of the Bode in the hall . The distribution area extends over the districts of Harz and Mansfeld-Südharz as well as parts of the Saalekreis and the Salzlandkreis.

Only twelve large stone graves are known from this area. The actual megalithic plays a subordinate role here. Small stone boxes and pseudomegalithic structures such as wall chamber tombs are much more common. Menhirs appearing individually or in groups are also very numerous. The similarities between the Hercynian group and the regional groups in northern Saxony-Anhalt are only slight. There are stronger parallels to the megalithics of Hesse and Westphalia.

| Grave type | secured | supposed |

|---|---|---|

| Sunken chamber graves | 2 | 1 |

| Large dolmen | - | 1 |

| Urdolmen | 2 | 1 |

| Sunken chamber graves or wall chamber graves | 3 | |

| Large dolmen or sunken chamber tombs | 1 | |

| Megalithic tombs (type not determined) | 4th | - |

| Megalithic tombs or wall chamber tombs | 2 | |

| Megalithic tombs or stone boxes | 2 |

The megalithic Middle Elbe-Saale group

The megalithic Middle Elbe-Saale group covers an area about 30 km long that extends from Dessau to Magdeburg west of the Elbe. It thus includes parts of the Börde district , the Salzlandkreis , the west of Anhalt-Bitterfeld (former Köthen district ) and parts of the city of Magdeburg. There are concentrations of large stone graves in the Magdeburg area and in the area between Bernburg and Köthen .

About 30 large stone graves are known in this area, among which the passage graves and large dolmen apparently dominate. In addition, there are isolated other dolmen shapes. No other types of large stone graves have been identified. The majority of the systems, however, can no longer be determined typologically. In terms of actual megalithics, the Middle Elbe-Saale group has a lot in common with its northern neighbors. But sub- and pseudomegalithic buildings and menhirs typical of the Hercynian group also appear here frequently.

| Grave type | secured | supposed |

|---|---|---|

| Large dolmen | 2 | 2 |

| Passage graves | 4th | 1 |

| Urdolmen | 1 | - |

| Large dolmen or passage graves | 2 | |

| Large dolmen or ramp boxes | 1 | |

| Urdolmen or extended dolmens | 1 | |

| Urdolmen or stone boxes | 1 | |

| Megalithic tombs (type not determined) | 14th | 8th |

| Megalithic tombs or wall chamber tombs | 1 | |

| (Field name references) | (8th) |

The East Elbian Group

The East Elbe Group comprises an area between the towns of Burg and Dessau-Roßlau , which is bounded in the west and south by the Elbe and in the northeast by the foothills of the Fläming. This includes most of the Jerichower Land district and the areas of the Anhalt-Bitterfeld and Salzlandkreis districts north of the Elbe . A particular concentration of the systems can be seen along the rivers Ehle and Nuthe .

About sixty large stone graves have been documented from the area of the East Elbe Group, but only four of them still exist. The East Elbe group thus shows the highest degree of destruction of the regional groups. The most common grave type is the chamberless megalithic bed , which does not occur in the other regions of Saxony-Anhalt. Hunebeds represent one of the oldest types of large stone graves. It is therefore likely that the megalithic in the East Elbe area appeared much earlier than in the Altmark. Otherwise, pass graves or large dolms occur here as there. Four proven menhirs also testify to a certain influence from the Hercynian area.

| Grave type | secured | supposed |

|---|---|---|

| Passage graves | 1 | 1 |

| Chamberless giant beds | 5 | 11 |

| Large dolmen or passage graves | 5 | |

| Megalithic tombs (type not determined) | 27 | 7th |

| (Field name references) | (16) |

Cultural classification

The megalithic in Saxony-Anhalt can be combined with several archaeological cultures. The first monumental grave structures appear in the early Neolithic and are associated with the Baalberg culture (4000–3400 BC) belonging to the funnel cup complex. For the first time, the burial grounds of this culture feature large, partly round, partly trapezoidal burial mounds and grave chambers lined with stone slabs.

The first large stone graves in the true sense of the word appear in the north with the Altmark group of deep engraving ceramics (3700-3350 BC). The distribution area of this group includes the Altmark, the Magdeburger Börde with the Haldensleber forest and an area along the Elbe to Köthen in the south. Outside of Saxony-Anhalt, it is widespread in north-eastern Lower Saxony as far as Hamburg . In part at the same time as the deep-engraving ceramics culture, other cultures built or used large stone graves in their area of distribution. In the Haldensleber Forest there are both graves with deep engraving ceramics and ceramics from the Walternienburg culture (3350–3100 BC). Burials / reburials of the spherical amphora culture (3100–2650 BC) also occur on a large scale .

In the south of Saxony-Anhalt, the megalithic buildings go back mainly to the Walternienburg and Bernburg cultures (3100–2650 BC). With the large stone grave Schortewitz at least one system is known that was built by the Salzmünder culture (3400-3100 BC).

reception

Great stone graves in legends and customs

In the Altmark in particular, numerous folk tales have survived that revolve around large stone graves and other special stone monuments. Like almost everywhere else in the megalithic area, stone-throwing giants play a decisive role as builders. In some cases, these legends were reinterpreted in Christian terms, for example by replacing the giants with the devil or having a biblical reference, such as the Stöckheim large stone grave, which is considered the tomb of the giant Goliath in the legend . Sometimes the sepulkral reference was completely lost in the legends , as the graves were viewed as the baking ovens of the giants.

Some legends also refer to specific historical events , but sometimes mix very different epochs. So is a legend of a knight of Charlemagne , of the Saxony - Herzog Widukind to visit and the megalithic tombs at Leetze on sacrificing Slavs hits. Presumably the Saxons themselves were originally meant here and only in a later version of the story did they become Slavs. Real historical references can also be found in various legends from Ballerstedt , Flessau and Dahrenstedt , which relate the megalithic graves that used to exist there in connection with the battles against the pagan Slavs ("Wendekkampf"). The actual plot revolves around the dispute between Albrecht the Bear and Udo von Freckleben over the rule in the Nordmark in the 30s of the 12th century. In narrative terms, these events were mixed up with the Slav uprising of 983 .

The legendary motif of the “Petrified Bride” can also be found in the Altmark. The legends tell of an unhappy bride who would rather turn to stone than marry the man she was supposed to be. The origin of this legendary motif is likely to have been the pre-Christian custom of holding weddings in certain holy places, such as stones. On the other hand, the bride's complaint was a long-practiced wedding ritual with which the house spirits were to be deceived.

Legends have also been formed about the frequently occurring, partly naturally created, partly artificial gutters and bowls on stones ( bowl stones ). Depending on the shape, the depressions were viewed as the prints of giant hands or as the hoof prints of horses or the devil. Grooves were interpreted as traces of straps or chains. The custom of the “butter stones” is also documented for the Altmark. The small bowls are spread with butter, either to win a magical ointment or to fix an offering for ghost beings.

Destruction of large stone graves

Occasional destruction of large stone graves can possibly be traced back to the time of Christianization . In the Altmark, for example, boulders were built into many cemetery walls. A large monolith was also built into the former main portal of the 12th century church in Jeetze . However, it can no longer be proven whether all these stones actually come from destroyed large stone graves. But there are also examples of careful handling of the old facilities in the course of Christianization, for example the Winterfeld large stone grave , which was integrated into the rectory of the newly built church in the 13th century.

Destruction on a larger scale did not take place until the 19th century, after the Prussian agricultural reforms of 1807 and 1811 led to a reallocation and enlargement of the previously dismembered arable land. In the Altmark, Johann Friedrich Danneil did not only endeavor in the 1830s and 40s to document, but also to preserve the large stone graves there. With the support of the state director of the Altmark, Wilhelm von der Schulenburg , he managed to raise funds for the purchase of some systems. Nevertheless, two thirds of the graves documented by him were destroyed in the following years. Elsewhere, however, there was no significant effort to preserve the large stone graves. Of the more than forty graves described by Joachim Gottwald Abel in the 18th century in what was then the district of Jerichow I, all but three were destroyed in the 19th century. By contrast, two thirds of the large stone graves near Haldensleben have been preserved due to their forest location.

In addition to the increase in arable land, the main reason for the destruction of the graves was the extraction of building material. So their stones were mainly used for the construction of roads and the construction of railway lines. After the First World War, war memorials were also erected in the Altmark from individually standing, large stones. In one case, however, the use of stones from a large stone grave already in the process of being destroyed is also guaranteed.

In the last hundred years, the number of large stone graves in Saxony-Anhalt has practically not decreased. However, some plants suffered considerable damage. The Ristedt large stone grave was almost completely destroyed in the 1960s or later. There is only one stone left. In the 1990s, a stonemason company tried to steal a capstone from the large stone grave in Nesenitz , but this was prevented by local residents.

Tourist use

Many large stone graves have now been made accessible to tourism by means of hiking trails and information boards. In the Haldensleber forest, for example, there is the “grave path”, via which almost all of the more than eighty graves located there can be reached. In the area around Bernburg, nine graves are grouped together to form the “Latdorf Stone Age Landscape”. These are three large stone graves ( Heringsberg , Bierberg , Steinerne Hütte ) and six burial mounds , including the Schneiderberg in Baalberge , the eponymous site of the Baalberg culture. The large stone grave in Langeneichstädt has been part of the " Himmelswege " tourist trail since 2005 . This also includes the State Museum of Prehistory in Halle, the Goseck district moat and the Nebra Arche , an experience center near the place where the Nebra Sky Disc was found . In the State Museum for Prehistory, the original of the menhir stele found in the grave of Langeneichstädt is on display. Most recently, the megalithic graves near Lüdelsen, two of which were excavated between 2007 and 2010, were integrated into a hiking trail on the history of the place.

See also

literature

Complete overview

- Hans-Jürgen Beier : The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. Contributions to the prehistory and early history of Central Europe 1. Wilkau-Haßlau 1991, ISBN 978-3-930036-00-4 .

- Ulrich Fischer : The Stone Age graves in the Saale region. Studies on Neolithic and Early Bronze Age grave and burial forms in Saxony-Thuringia. Verlag Walter de Gruyter & Co., Berlin 1956, ISBN 978-3-11-005286-2 .

- Barbara Fritsch : Megalithic graves in Saxony-Anhalt. In: Harald Meller (Ed.): Early and Middle Neolithic. Catalog for the permanent exhibition in the State Museum of Prehistory. Halle (Saale), in press.

- Barbara Fritsch et al .: Density Centers and Local Groups - A Map of the Great Stone Graves of Central and Northern Europe. In: www.jungsteinsite.de. October 20, 2010 ( PDF; 1.6 MB , XLS; 1.4 MB ).

- Barbara Fritsch, Johannes Müller : Great stone graves in Saxony-Anhalt. In: Hans-Jürgen Beier (Ed.): Finding and Understanding. Festschrift for Thomas Weber on his sixtieth birthday. Contributions to the prehistory and early history of Central Europe 66. Langenweißbach 2012, ISBN 978-3-941171-67-1 , pp. 121-133 ( online ).

- Britta Schulze-Thulin : Large stone graves and menhirs. Saxony-Anhalt • Thuringia • Saxony. Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Halle (Saale) 2007, ISBN 978-3-89812-428-7 .

Aller-Ohre group

- Wilhelm Blasius : Prehistoric monuments between Helmstedt, Harbke and Marienborn. Braunschweig 1901 ( online ).

- Wilhelm Blasius: The megalithic grave monuments at Neuhaldensleben. In: 12th annual report of the Association for Natural Science in Braunschweig. 1902, pp. 95-153 ( online ).

- Barbara Fritsch et al .: Origin, function and relation to the landscape of large stone graves, earthworks and settlements of the funnel cup cultures in the Haldensleben-Hundigsburg region. Preparatory work and first results. In: Harald Meller (ed.): Dug up - cooperation projects in Saxony-Anhalt. Conference from 17 to 20 May 2009 in the State Museum for Prehistory Halle (Saale) (= Archeology in Saxony-Anhalt. Special volume 16). State Office for Monument Preservation and Archeology Saxony-Anhalt and State Museum for Prehistory, Halle (Saale) 2012, ISBN 978-3-939414-63-6 , pp. 57–64.

- Dieter Kaufmann: Haldensleben Forest. In: Joachim Herrmann (Hrsg.): Archeology in the German Democratic Republic. Monuments and finds. Volume 2. Urania Verlag, Leipzig / Jena / Berlin 1989, pp. 406-408.

- Stefanie Klooss, Wiebke Kierleis: The charred plant remains from the multi-period trenching Hundisburg-Olbetal near Haldensleben, Bördekreis, Saxony-Anhalt. In: Martin Hinz, Johannes Müller (eds.): Settlement, trench works, large stone grave. Studies on the society, economy and environment of the funnel cup groups in northern Central Europe (= early monumentality and social differentiation. Volume 2). Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Bonn 2012, ISBN 978-3-7749-3813-7 , pp. 377-382 ( online ).

- Joachim Preuß : excavation of megalithic graves in the Haldensleben forest In: annual journal of the district museum Haldensleben. Volume 11, 1970, pp. 5-15.

- Joachim Preuß: excavation of megalithic graves in the Haldensleben forest - preliminary report. In: excavations and finds. Volume 15, 1970, pp. 20-24.

- Joachim Preuss: Megalithic graves with ancient deep engraving ceramics in the Haldensleben forest. In: Neolithic Studies II. Scientific contributions from the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1973, pp. 127–208.

- Joachim Preuß: The restoration of a megalithic grave in the Haldensleben forest In: Annual journal of the district museum Haldensleben. Volume 17, 1976, pp. 16-25.

- Joachim Preuß: Restoration of large stone graves In: Joachim Hermann (Hrsg.): Archaeological monuments and environmental design (= publications of the ZIAGA. Volume 9). Berlin 1978, pp. 193-197.

- Joachim Preuss: The Altmark group of deep engraving ceramics (= publications of the State Museum for Prehistory in Halle. Volume 33). German Science Publishing House, Berlin 1980.

- Bruno Rahmlow: Investigations into the inventory of the large stone graves in the district area. In: Annual journal of the district museum Haldensleben. Vol. 1, 1960, pp. 26-33.

- Bruno Rahmlow: Addendum to the investigations into the inventory of the large stone graves in the district area. In: Annual journal of the district museum Haldensleben. Vol. 2, 1961, p. 99.

- Bruno Rahmlow: Investigations into the inventory of the large stone graves in the district of Haldensleben - 2nd supplement. In: Annual journal of the district museum Haldensleben. Vol. 12, 1971, pp. 5-7.

- Christoph Rinne: rescue excavation in a megalithic grave on the edge of the Haldensleber forest. Alt-Haldensleben Fpl. 34, Borde district. In: Martin Hinz, Johannes Müller (eds.): Settlement, trench works, large stone grave. Studies on the society, economy and environment of the funnel cup groups in northern Central Europe (= early monumentality and social differentiation. Volume 2). Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Bonn 2012, ISBN 978-3-7749-3813-7 , pp. 383-388 ( PDF; 0.8 MB ).

- Christoph Rinne: The megalithic graves in the Haldensleber forest (= early monumentality and social differentiation. Volume 17). Habelt, Bonn 2019, ISBN 978-3-7749-4201-1 .

- Christoph Rinne, Matthias Lindemann: Origin, function and relation to the landscape of large stone graves, earthworks and settlements of the funnel cup culture in the Haldensleben-Hundisburg region. In: Annual journal of the museums of the district of Börde. Vol. 50 (17), 2010, pp. 21-39.

- Christoph Rinne, Johannes Müller: Trench works and large stone graves in a border region. First results of the Haldensleben-Hundisburg project. In: Martin Hinz, Johannes Müller (Hrsg.): Settlement Grabenwerk Großsteingrab. Early Monumentality and Social Differentiation. Volume 2, Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Bonn 2012, ISBN 978-3-7749-3813-7 , pp. 347-375 ( online ).

- Friedrich Schlette : Investigation of large stone graves in the Haldensleben forest. In: excavations and finds. Vol. 5, 1960, pp. 16-19.

- Friedrich Schlette: The investigation of a large stone grave group in the Bebertal, Haldensleben forest. In: Annual publication for Central German prehistory. Vol. 46, 1962, 137-181.

- Kay Schmütz: Conception and implementation of monumentality at the Küsterberg megalithic grave in the Haldensleber Forest. In: Harald Meller (ed.): 3300 BC - mysterious stone age dead and their world. Nünnerich-Asmus, Mainz 2013, ISBN 978-3-943904-33-8 , pp. 132-134.

- Kay Schmütz: The development of two concepts? Large stone graves and trench works near Haldensleben-Hundisburg (= early monumentality and social differentiation. Volume 12). Habelt, Bonn 2016, ISBN 978-3-7749-4051-2 .

- Karl Stuhlmann: Floor plan drawings and some site plans of the barrows near Neuhaldensleben. Neuhaldensleben 1934.

- Philipp Wegener: Contributions to the knowledge of the Stone Age in the area of the ears. In: Monday newspaper of the Magdeburgische Zeitung. 1896, pp. 299-343.

- Philipp Wegener: On the prehistory of Neuhaldensleben and the surrounding area. In: History sheets for the city and state of Magdeburg. Vol. 31, 1896, pp. 347-362.

Altmark Group

- Johann Christoph Bekmann , Bernhard Ludwig Bekmann : Historical description of the Chur and Mark Brandenburg according to their origin, inhabitants, natural characteristics, waters, landscapes, towns, clerical donors etc. […]. Vol. 1, Berlin 1751 ( online version ).

- Wilhelm Blasius: Guide to the megalithic grave monuments in the western part of the Salzwedel district. In: Thirty-first annual report of the Altmark Association for Patriotic History and Industry. Issue 2, 1904, pp. 95–114 ( PDF; 8.1 MB ).

- Hartmut Bock, Barbara Fritsch, Lothar Mittag: Great stone graves of the Altmark. State Office for Monument Preservation and Archeology Saxony-Anhalt and State Museum for Prehistory, Halle (Saale) 2006, ISBN 978-3-8062-2091-9 .

- Johann Friedrich Danneil : Grave monuments from pre-Christian times. Division of the various grave monuments from pagan times in the Altmark. In: First annual report of the Altmark Association for Patriotic History and Industry. 1838, pp. 31-57 ( PDF; 4.6 MB ).

- Johann Friedrich Danneil: Special evidence of the barrows in the Altmark. In: Sixth annual report of the Altmark Association for Patriotic History and Industry. 1843, pp. 86-122 ( PDF; 5.5 MB ).

- Denis Demnick: Visibility analyzes using the example of megalithic graves from the Altmark . In: Hans-Jürgen Beier et al. (Ed.): Neolithic monuments and Neolithic societies. Varia neolithica VI (= contributions to the prehistory and early history of Central Europe. Volume 56). Verlag Beier & Beran, Langenweißbach 2009, ISBN 978-3-941171-28-2 , pp. 145-156.

- Denis Demnick et al .: The Großdolmen Lüdelsen 3 in the western Altmark (Saxony-Anhalt). Building history, rituals and landscape reconstruction. In: www.jungsteinsite.de - Article from December 15, 2008 ( PDF; 4.65 MB ).

- Denis Demnick et al .: The large stone grave Lüdelsen 3 in the western Altmark (Saxony-Anhalt). Preliminary report on the 2007 excavation and the pollen profile in the Beetzendorfer Bruch. With contributions by A. Beyer, J.-P. Brozio, E. Erkul, H. Kroll, and E. Tafel. In: Annual publication for Central German prehistory. Vol. 92, 2008 (2011), pp. 231-308.

- Denis Demnick et al .: Determining the use of space. - Great stone graves of the Altmark. In: Archeology in Germany. Issue 4/2009, 2009, pp. 34–39.

- Sarah Diers, Denis Demnick: Megalithic landscape in the western Altmark: Middle Neolithic settlement patterns of a small region with large stone complexes . In: Harald Meller (ed.): Dug up - cooperation projects in Saxony-Anhalt. Conference from 17 to 20 May 2009 in the State Museum for Prehistory Halle (Saale) (= Archeology in Saxony-Anhalt. Special volume 16). State Office for Monument Preservation and Archeology Saxony-Anhalt and State Museum for Prehistory, Halle (Saale) 2012, ISBN 978-3-939414-63-6 , pp. 49–56.

- Sarah Diers: et al .: Altmark megalithic landscape - a new project on megalithic graves and settlement patterns in the Altmark. In: Hans-Jürgen Beier et al. (Ed.): Neolithic monuments and Neolithic societies. Varia neolithica VI (= contributions to the prehistory and early history of Central Europe. Volume 56). Verlag Beier & Beran, Langenweißbach 2009, ISBN 978-3-941171-28-2 , pp. 65-71.

- Sarah Diers et al .: The Western Altmark versus Flintbek - palaeoecological research on two megalithic regions. In: Journal of Archaeological Science. Volume 41, 2014, pp. 185-198 ( online ).

- Ulrich Fischer: Investigations of large stone graves in the Altmark. In: 53rd annual report of the Altmark Association for Patriotic History in Salzwedel. 1939, pp. 3-8.

- Hans-Ulrich Kelch: Mysterious pans. In: Hartmut Bock (Ed.): Cities - Villages - Friedhöfe. Archeology in the Altmark 2: From the High Middle Ages to the modern age (= contributions to the cultural history of the Altmark and its peripheral areas, Volume 8). Oschersleben 2002, ISBN 3-935358-36-9 , pp. 458-469.

- Eduard Krause, Otto Schoetensack : The megalithic graves (stone chamber graves) of Germany. I. Altmark. In: Journal of Ethnology. Vol. 25, 1893, pp. 105-170, Plates V-XIII ( PDF; 39.0 MB ).

- Lothar Mittag: Fabulous stones. Large stone graves, special stones and stone crosses in the Altmark world of legends. Johann-Friedrich-Danneil-Museum Salzwedel, Spröda 2006, ISBN 3-00-020624-8 .

- Julius Müller : The uncovering of a barrow. In: Thirty-third annual report of the Altmark Association for Patriotic History in Salzwedel. 1906, pp. 127–128 ( PDF; 8.7 MB ).

- Joachim Preuss : The Altmark group of deep engraving ceramics. Publications of the State Museum for Prehistory in Halle 33. Berlin 1980.

- Joachim Preuss: Johann Friedrich Danneil and the great stone graves of the Altmark. In: Ethnographic-Archaeological Journal. Vol. 24, 1983, pp. 649-667.

- K. Schwarz: On the prehistoric settlement of the land on the Speckgrabenniederung in the Stendal district. In: Annual publication for Central German prehistory. Vol. 33, 1949, pp. 58-85.

- G. Wetzel: The Neolithic settlement of the Altmark. In: Annual publication for Central German prehistory. Vol. 50, 1966, pp. 33-60.

Hercynian group

- Adelheid Bach, Sabine Birkenbeil: Collective graves of the Bernburg culture in the Middle Elbe-Saale area. Weimar Monographs on Prehistory and Early History 23. Weimar 1989, pp. 66–79.

- Hermann Behrens : Large burial mounds, large stone graves and large stones in the lower Saale area. Bernburg 1963.

- Hermann Behrens: Western European influences in the Central German Neolithic. In: excavations and finds. Vol. 10, pp. 16-20.

- Ulrich Fischer: To the Neolithic collective graves in Hesse and Thuringia. In: Nassau Annals. Vol. 79, 1968, pp. 1-21.

- Ulrich Fischer: On the megalithic of the Hercynian mountain threshold. In: Jysk Arkaeologisk Selskabs skrifter. Vol. 11, 1973, pp. 51-61.

- Ulrich Fischer: View from the Hessian valley on Walternienburg-Bernburg. In: Annual publication for Central German prehistory. Vol. 63, 1981, pp. 89-97.

- Detlef W. Müller: burial chamber of the Central German type with menhir from Langeneichstädt, district of Querfurt. In: excavations and finds. Vol. 33, 1988, pp. 192-199.

- Detlef W. Müller: Neolithic stone chamber grave at the Eichstädter Warte near Langeneichstädt, Querfurt district. In: Querfurter Heimatkalender 1989/90. 1989, pp. 66-74.

- Detlef W. Müller, Heribert Stahlhofen: Two collective graves of the Bernburg culture from the northern Harz foreland. In: Annual publication for Central German prehistory. Vol. 63, 1981, pp. 27-65.

Megalithic Middle Elbe Saale Group

- Caspar Abel : Teutsche and Saxon antiquities, the Teutschen, and Saxony, ancient history, and ancestors, names, origins, and fatherland, trains, and wars ... From the best writings and legal documents ... presented and ... explained, but specialty the high tribe, the royal ... house of Braunschweig-Lüneburg, executed until our time ... including a Lower Saxon clock-old Chronick that has never been printed. Part 2, Braunschweig 1730 ( online version ).

- Johann Christoph Bekmann: History of the Principality of Anhalt From its old inhabitants and some old monuments that were still available / Natural Bütigkeit / Division / Rivers / Towns / Patches and villages / Fürstl. Highness / Stories of the Prince. People / religious acts / princely ministries, aristocratic families / scholars / and other bourgeois class noble people. 1st - 4th Part, Zerbst 1710 ( online version ).

- Gerd Böttcher: Great stone graves in the urban area of Magdeburg. In: Magdeburg leaves. 1987, pp. 76-81.

- Wilhelm Albert von Brunn: Knowledge and care of the ground monuments in Anhalt. In: Annual publication for Central German prehistory. Vol. 41/42, 1958, pp. 28-71.

- Fabian Gall: Stone Age Landscape Latdorf (= small booklets on archeology in Saxony-Anhalt. Volume 1). State Office for Monument Preservation and Archeology Saxony-Anhalt and State Museum for Prehistory, Halle (Saale) 2003, ISBN 978-3-910010-70-3 .

- O. Gorges, Hans Seelmann: The giant room on the Bruchberge near Drosa (Kr. Koethen). In: Annual publication for the prehistory of the Saxon-Thuringian countries. Vol. 4, 1905, pp. 33-43.

- Walter Götze-Geuz : Prehistoric graves in the district of Cöthen. Coethen 1913.

- Martin Jahn : The first excavation of the megalithic grave of Wulfen in Anhalt. In: Mannus . Vol. 17, 1925, pp. 110-111.

- Hans-Joachim Krenzke: Magdeburg cemeteries and burial places. State capital Magdeburg, City Planning Office Magdeburg, Magdeburg 1998 ( PDF; 6.28 MB ).

- Hans Lies: On the Neolithic settlement intensity in the Magdeburg area. In: Annual publication for Central German prehistory. Vol. 58, 1974, pp. 57-111.

- F. Lüth: The Schortewitzer Heidenberg and the time of the Anhalt megalithic graves. In: Acta praehistorica et archaeologica. Vol. 20, 1988, pp. 61-74.

- Brigitte Schiefer: The Schortewitz Heidenberg and its position in the Central German Neolithic. Unpubl. Master's thesis, Halle (Saale) 2002.

- W. Schulz: Jacobus Tollius and the megalithic graves near Magdeburg. In: Annual publication for Central German prehistory. Vol. 43, 1959, pp. 121-126.

- R. Schulze: The younger Stone Age in the Koethener Land. Dessau 1930.

East Elbian group

- Ernst Herms: The megalithic graves of the district of Jerichow I. In: Festschrift of the Magdeburg Museum for Natural and Local History for the 10th Conference on Prehistory , Magdeburg 1928, pp. 243–262.

Others

- Hermann Behrens: The Walternienburg and Bernburg ceramic styles and the Walternienburg-Bernburg culture. In: Annual publication for Central German prehistory. Vol. 63, 1981, pp. 11-16.

- Hermann Behrens: The Neolithic Age in the Middle Elbe-Saale area. Berlin 1973.

- Hans-Jürgen Beier: The grave and burial customs of the Walternienburg and Bernburg culture. Halle (Saale) 1984.

- Hans-Jürgen Beier: The spherical amphora culture in the Middle Elbe-Saale area and in the Altmark. Berlin 1988, ISBN 978-3-326-00339-9 .

- Barbara Fritsch et al .: Density Centers and Local Groups - A Map of the Great Stone Graves of Central and Northern Europe. In: www.jungsteinsite.de - Article from October 20, 2010 ( PDF; 1.6 MB / XLS; 1.4 MB ).

- Alexander Häusler: On the grave and burial customs of the Walternienburg-Bernburg culture. In: Annual journal for Central German Prehistory. Vol. 63, 1981, pp. 75-87.

- Paul Kupka : The roots of Central German Stone Age pottery. In: Contributions to the history, regional and folklore of the Altmark. Vol. 4, Issue 7, 1921, 364-384.

- Paul Kupka: The central German passage graves and the pottery of their time. In: Contributions to the history, regional and folklore of the Altmark. Vol. 4, Issue 8, 1924, pp. 429-443.

- Paul Kupka: Remarks on the timing of our more recent stone ages. In: Contributions to the history, regional and folklore of the Altmark. Vol. 5, Issue 2, 1926, 61-81.

- F. Lüth: To the central German collective graves. In: Hammaburg. NF Vol. 9, 1989, pp. 41-52.

- Johannes Müller: Sociochronological studies on the Young and Late Neolithic in the Middle Elbe-Saale area (4100–2700 BC). A socio-historical interpretation of prehistoric sources. Publishing house Marie Leidorf, Rahden / Westf. 2001, ISBN 978-3-89646-503-0 .

- Waldtraut Schrickel : Western European elements in the Neolithic and the Early Bronze Age of Central Germany. Part 1: Text. Leipzig 1957.

- Waldtraut Schrickel: Western European elements in the Neolithic and the Early Bronze Age of Central Germany. Part 2: Catalog. Leipzig 1957.

- Waldtraut Schrickel: Western European elements in the Neolithic grave construction of Central Germany and the gallery graves of West Germany and their inventories. Bonn 1966, ISBN 978-3-7749-0575-7 .

- Waldtraut Schrickel: Catalog of the Central German graves with Western European elements and the gallery graves of Western Germany. Bonn 1966.

Web links

- Great stone graves and megalithic structures - Saxony-Anhalt

- Megalithic tombs and menhirs in Saxony-Anhalt

Individual evidence

- ^ Schulz: Jacobus Tollius and the large stone graves near Magdeburg. 1959.

- ↑ Bekmann: History of the Principality of Anhalt. 1710, pp. 25-27, plate 1.

- ↑ Bekmann / Bekmann: Historical description of the Chur and Mark Brandenburg. 1751.

- ↑ Bekmann / Bekmann: Historical description of the Chur and Mark Brandenburg. 1751, pp. 347-351.

- ↑ Hartmut Bock, Barbara Fritsch, Lothar Mittag: Großsteingraves der Altmark. 2006: Great stone graves of the Altmark. 2006, p. 14.

- ^ Abel: Teutsche and Saxon Antiquities. Part 2, 1730, pp. 487-492.

- ↑ a b Herms: The megalithic graves of the district of Jerichow I. 1928.

- ↑ A detailed summary of Danneil's research can be found in Preuß: Johann Friedrich Danneil and the great stone graves of the Altmark. 1983.

- ↑ Krause / Schoetensack: The megalithic graves (stone chamber graves) of Germany. I. Altmark. 1893.

- ↑ a b Hartmut Bock, Barbara Fritsch, Lothar Mittag: Großsteingräber der Altmark. 2006: Great stone graves of the Altmark. 2006, pp. 186-191.

- ↑ Kupka: The roots of Central German Stone Age pottery. 1921; Kupka: Remarks on the timing of our more recent stone ages. 1926.

- ^ Fischer: Large stone grave investigations in the Altmark. 1939.

- ↑ Gorges / Seelmann: The giant room on the Bruchberge near Drosa (Kr. Köthen). 1905.

- ↑ Wegener: Contributions to the knowledge of the Stone Age in the area of the ears. 1896; Wegener: On the prehistory of Neuhaldensleben and the surrounding area. 1896.

- ↑ Blasius: The megalithic grave monuments near Neuhaldensleben .. 1901; Blasius: Prehistoric monuments between Helmstedt, Harbke and Marienborn. 1901.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, p. 33.

- ^ Schlette: The investigation of a large stone grave group in the Bebertal, Haldensleben forest. 1962.

- ^ Preuss: Megalithic graves with ancient deep engraving ceramics in the Haldensleben forest. 1973.

- ^ Fritsch / Müller: Great stone graves in Saxony-Anhalt. 2012, p. 121.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, part 2.

- ↑ Hartmut Bock, Barbara Fritsch, Lothar Mittag: Großsteingraves der Altmark. 2006: Great stone graves of the Altmark. 2006.

- ↑ Demnick et al .: The Großdolmen Lüdelsen 3 in the western Altmark (Saxony-Anhalt). 2008; Demnick et al .: The large stone grave Lüdelsen 3 in the western Altmark (Saxony-Anhalt). 2011.

- ↑ a b State Museum of Prehistory - Find of the Month, May 2011: May: Hiking between megalithic tombs - the new archaeological-historical hiking trail in Lüdelsen .

- ↑ Origin, function and relation to the landscape of large stone graves, trench works and settlements of the funnel cup cultures in the Haldensleben-Hundisburg region .

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, pp. 84-86.

- ↑ Demnick et al .: The Großdolmen Lüdelsen 3 in the western Altmark (Saxony-Anhalt). 2008.

- ^ Fritsch / Müller: Great stone graves in Saxony-Anhalt. 2012, p. 123.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, pp. 86-88.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, pp. 79-84.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, pp. 88-90.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, pp. 79, 101-107.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, pp. 40–41, supplemented and corrected according to Hartmut Bock, Barbara Fritsch, Lothar Mittag: Großsteingräber der Altmark. 2006: Great stone graves of the Altmark. 2006.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, p. 115.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, pp. 145-170.

- ^ Fritsch / Müller: Great stone graves in Saxony-Anhalt. 2012, pp. 122–123.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, pp. 156-160.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, pp. 160-161.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, p. 155.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, pp. 146-148.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, pp. 148-150; Preuss: The Altmark group of deep engraving ceramics. 1980, p. 90.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, p. 146, supplemented and corrected from Hartmut Bock, Barbara Fritsch, Lothar Mittag: Großsteingräber der Altmark. 2006: Great stone graves of the Altmark. 2006.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, p. 166.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, pp. 166-170.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, p. 167.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, p. 163.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, pp. 163-165.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, p. 162.

- ↑ a b Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, p. 152.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, pp. 153-154.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, pp. 171-172.

- ^ Preuss: The Altmark group of deep engraving ceramics. 1980. Map 1.

- ^ Fritsch / Müller: Great stone graves in Saxony-Anhalt. 2012, pp. 127–128.

- ↑ Demnick et al .: The large stone grave Lüdelsen 3 in the western Altmark (Saxony-Anhalt). 2011.

- ↑ Beier: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest. 1991, pp. 177-178; Fritsch / Müller: Great stone graves in Saxony-Anhalt. 2012, p. 128.

- ^ Slate: The Schortewitzer Heidenberg and its position in the Central German Neolithic. 2002.

- ↑ Noon: Legendary Stones. 2006, p. 7.

- ↑ Noon: Legendary Stones. 2006, pp. 7-8.

- ↑ Noon: Legendary Stones. 2006, p. 34.

- ↑ Noon: Legendary Stones. 2006, p. 8.

- ↑ Noon: Legendary Stones. 2006, pp. 8, 39-40.

- ↑ Noon: Legendary Stones. 2006, pp. 8-9, 51-52.

- ↑ Noon: Legendary Stones. 2006, pp. 9-10.

- ↑ Noon: Legendary Stones. 2006, p. 10.

- ↑ Hartmut Bock, Barbara Fritsch, Lothar Mittag: Großsteingraves der Altmark. 2006: Great stone graves of the Altmark. 2006, p 185; Midday: fabulous stones. 2006, p. 10.

- ↑ Hartmut Bock, Barbara Fritsch, Lothar Mittag: Großsteingraves der Altmark. 2006: Great stone graves of the Altmark. 2006, p. 19.

- ↑ Hartmut Bock, Barbara Fritsch, Lothar Mittag: Großsteingraves der Altmark. 2006: Great stone graves of the Altmark. 2006, pp. 18-19.

- ^ Preuss: Johann Friedrich Danneil and the great stone graves of the Altmark. 1983.

- ↑ Rahmlow: Investigations into the inventory of the large stone graves in the district area. 1960; Rahmlow: Addendum to the investigations into the inventory of the large stone graves in the district. 1961; Rahmlow: Investigations into the inventory of the large stone graves in the district of Haldensleben - 2nd addendum. 1971.

- ↑ Hartmut Bock, Barbara Fritsch, Lothar Mittag: Großsteingraves der Altmark. 2006: Great stone graves of the Altmark. 2006, pp. 19, 43.

- ↑ The destroyed large stone grave Ristedt near Salzwedel .

- ↑ Hartmut Bock, Barbara Fritsch, Lothar Mittag: Großsteingraves der Altmark. 2006: Great stone graves of the Altmark. 2006, pp. 21, 136.

- ↑ The barrows in the Haldensleber forest. regio-md.de, accessed on April 28, 2020 .

- ^ Gall: Stone Age Landscape Latdorf. 2003.

- ↑ Himmelswege - the new tourism route in Saxony-Anhalt ( Memento of the original from December 21, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .