Eastern territories of the German Empire

Mark Brandenburg , Duchy of Prussia , Brandenburg-Prussia , Kingdom of Prussia

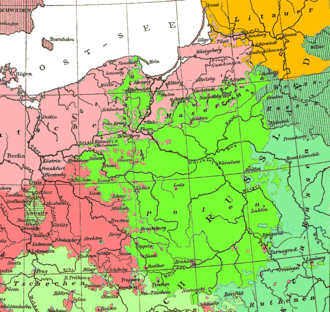

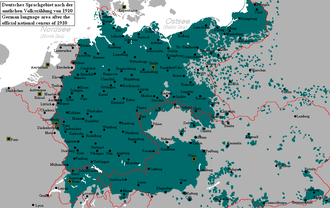

The territories east of the Oder-Neisse Line , which belonged to the territory of the German Reich on December 31, 1937 , were effectively separated from Germany after the end of the Second World War in 1945 and are now closed, are referred to as the eastern territories of the German Reich or former German eastern territories Poland and Russia belong. These areas made up about a quarter of the area, a seventh of the population and a significantly below average share of industrial production in Germany. In the People's Republic of Poland , these areas were referred to as “ Reclaimed Areas ” ( Polish Ziemie Odzyskane ) or “Western and Northern Areas” (Polish Ziemie Zachodnie i Północne ).

The eastern territories of the German Empire in the broader sense also include areas that Germany had to cede after the First World War in 1920 due to the Versailles Treaty of 1919: the major parts of the Prussian provinces of Posen and West Prussia , the former East Prussian area of Soldau and the Upper Silesian industrial area (to Poland ) as well as the Hultschiner Ländchen (to Czechoslovakia ) and Memelland (to the Allied Powers, annexed by Lithuania in 1923 ), as well as the city of Danzig as the Free City of Danzig .

Prehistory of the term "Eastern Territories"

After the annexation of areas of the Second Polish Republic as part of the partition of Poland in 1939 , the areas incorporated into the Prussian provinces of East Prussia , Silesia as well as the Reichsgaue Wartheland and Danzig-West Prussia , i.e. the areas incorporated into the national territory of the National Socialist German Reich, were officially referred to as "incorporated eastern areas" (see “ Germanization Policy ”). This term, which was valid until 1945 and is spatially differently defined, must be distinguished from the designation eastern areas of the German Reich .

Separation from Germany

History and decision making

According to the secret protocol of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact that had the Soviet Union in 1939, the Polish east of the rivers Narev , Vistula and San occupied . Even after becoming part of the anti-Hitler coalition , the Soviet Union refused to return these areas to Poland. At the Tehran Conference in 1943, Josef Stalin obtained the general approval of the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and the US President Franklin D. Roosevelt to move Poland to the west : the loss of territory in the country was to be compensated for by German territories east of the Oder . Stalin claimed the north of East Prussia with Königsberg for the Soviet Union itself. The Polish government-in-exile did not agree: It insisted on the border, as it had been agreed upon in the Peace of Riga in 1920 after the Polish-Soviet war . In the west she only aimed to acquire East Prussia, Danzig, Upper Silesia and smaller parts of Pomerania, because she considered the resettlement of the eight to ten million Germans who inhabited these areas, which would be necessary in the case of larger territorial acquisitions, to be impracticable. This attitude was shared by the Americans and the British. But even at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, Churchill and Roosevelt were unable to come to an agreement with Stalin. Although the eastern border of Poland was confirmed, as it had been determined in Tehran, in the west Poland was only vaguely promised compensation at Germany's expense.

Actual separation

After the invasion of the Red Army , Stalin created facts before the end of the war : In a decree of the Soviet-controlled State National Council of March 2, 1945, it said that all German assets in the eastern regions were "abandoned and abandoned", which is why they were confiscated. On March 14th and 20th the voivodeships of Masuria , Upper Silesia , Lower Silesia , Pomerania and Danzig were founded. On April 21, 1945, the Soviet government signed a contract with the provisional government of Poland , which it installed , in which it transferred administrative sovereignty over the areas under Soviet occupation east of the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers. On May 24, 1945, the Soviet government officially subordinated these areas to the Polish state, although on June 5, 1945 they were still understood as part of the Soviet zone of occupation. The legal scholar Susanne Hähnchen writes that, according to the Berlin Declaration, “the Allies also formally [took over] supreme governmental power for the territory of the German Reich within the borders of 1937; the eastern territories came under Soviet and then Polish administration. ”According to the historian Gerrit Dworok, these borders no longer played a role in constitutional practice.

At the Potsdam Conference in the summer of 1945, Great Britain and the USA took note of these facts created by the Soviet Union with the weak reservation that the final borders should only be agreed upon in a peace treaty to be concluded . They assured Stalin, however, that in the event of appropriate negotiations they would support the Soviet claims to the area around Konigsberg . Shortly before that, in the "Statement on the Control Procedure" (the Berlin Declaration ) of June 5, 1945, they had assumed that German territory was within the 1937 borders . The victorious powers decided, in addition to the peace treaty reservation for the final drawing of borders, that an Allied Control Council should ensure a uniform occupation policy in the occupation zones . However, this did not apply to the German eastern areas: The Potsdam final declaration of August 2, 1945 stated that the areas east of the Oder-Neisse line should not be regarded as part of the Soviet occupation zone and instead should be subordinated to foreign administration. Under international law , this situation persisted until the assignment based on the Two-Plus-Four Treaty of September 12, 1990, in fact Poland and the Soviet Union incorporated the formerly German East into their national territory and thus into their administrative structures under constitutional law.

Soviet administration

Likewise, the northern part of East Prussia around Königsberg came under provisional Soviet administration. The Königsberg area (northern East Prussia) was directly integrated into the Russian republic of the USSR (RSFSR) in 1946 ; it is now called Kaliningrad Oblast and is still a Russian exclave after the collapse of the Soviet Union .

Polish administration

The southern part of East Prussia, the eastern parts of the Prussian province of Pomerania ( Hinterpommern ), the Mark Brandenburg ( East Brandenburg ) and the state of Saxony as well as the Prussian provinces of Lower and Upper Silesia were assigned to Poland for provisional administration; de facto , an annexation took place immediately after the war.

In Polish usage, in the sense of Polish research on the west, the designation regained western and northern areas or simply regained areas was coined. This refers to the partial affiliation of these territories to the Piastic Kingdom of Poland from the establishment of the state in the 10th century, as well as to Polish duchies, into which the kingdom split up after 1138. The affiliation of these territories to Poland spans a period from the early to late Middle Ages as well as their Slavic prehistory before the beginning of the German settlement in the east . East Germanic and Baltic settlements in the age of antiquity are ignored here.

Recognition of the Polish western border and all-German renunciation

All the governments of the Federal Republic of Germany up to 1990 took the position that the final declaration of the Potsdam Conference had granted neither Poland nor the Soviet Union the eastern territories in question, and that any final decision was postponed until a peace treaty was settled.

For the 1949 Bundestag election, the Social Democratic Party of Germany advertised with a poster that even ignored the Polish Corridor from 1920. In his greeting to the Silesian meeting on June 8, 1963, Willy Brandt , then Governing Mayor of West Berlin , exclaimed : “German Ostpolitik must never be carried out behind the backs of the displaced. Anyone who regards the Oder-Neisse Line as a border that is accepted by our people is lying to the Poles. "

The German Democratic Republic recognized under Soviet pressure in Görlitz border agreement with the Republic of Poland on 6 July 1950, the Oder-Neisse line as a "border of peace" and from their perspective final border between Germany and Poland. The governments of the Federal Republic of Germany did not share this point of view at the time and did not attribute any legal significance to the agreement. They also represented the continued existence of the German Reich within the borders of 1937 , according to which the eastern territories were basically to be regarded as German inland and German citizens of the interwar period and their descendants would continue to have a uniform German nationality .

In the old Federal Republic before 1990 (i.e. old federal states and Berlin (West) ), the legal status of the eastern territories formed a large part of the open German question . The Ostpolitik of the Federal Government , Bundestag and Bundesrat was aimed at revising the borders until the mid-1960s; they invoked international law and various international treaties , in particular the Hague Land Warfare Regulations and the Atlantic Charter . The new Ostpolitik of the Grand Coalition of 1966 and later strengthened the social-liberal coalition from 1969 onwards brought about a gradual change through rapprochement . With the Warsaw Treaty of 1970, the Federal Republic of Germany recognized that these areas belonged to Poland. Due to the Allies' reservation in force until 1990 on issues affecting Germany as a whole and Berlin status , the Federal Republic of Germany was not allowed to recognize the Oder-Neisse line as a German-Polish border under international law and to request repayment of the territories.

It was only in the course of German reunification in 1990 that the Eastern Territories were separated under international law by the Two-Plus-Four Treaty (transfer of territorial sovereignty to Poland or the Soviet Union / Russian Federation ) and the Oder-Neisse border was established a little later was formally confirmed by Germany in the German-Polish border treaty of November 14, 1990. The latter came into force on January 16, 1992. This brought all issues following the war to a conclusion. With the amendment of the German Basic Law of September 23, 1990, it was now stated in the preamble that "the unity [...] of Germany is complete" .

Extent of the eastern territories

definition

In detail, the eastern areas include the Prussian territories:

- the province of East Prussia : 36,966 km²

- the province of Upper Silesia and the province of Lower Silesia without their part to the west of the Neisse (now part of Saxony) around Görlitz : 34,529 km²

- the province of Pomerania east of the Oder (historical Western Pomerania ) as well as Stettin and the mouth of the Oder: 31,301 km²

- the administrative district of Frankfurt of the province of Brandenburg without its part to the west of the Oder and Neisse: 11,329 km²

- as well as the part of the state of Saxony east of the Neisse around the city of Reichenau i. Saxony : 142 km²

The Prussian border mark Posen-West Prussia (the remaining areas of the province of Posen and West Prussia that remained with Germany in 1919 ) with an area of 7,695 km² was divided among its three neighboring provinces in 1938 and is included in the above figures. The total extent of the eastern areas is 114,267 km² (the difference to 114,269 km² is due to rounding), which corresponded to about a quarter of Germany within the borders of 1937.

In 1939, around 9,620,800 people lived in the eastern regions of the German Reich (45,600 of them were without German citizenship). Of these accounted for

- East Prussia: 2,488,100 inhabitants (including 15,100 without German citizenship),

- Silesia : 4,592,700 inhabitants (of which 16,200 without German citizenship; figures for Zittau's population included),

- Pomerania : 1,895,200 inhabitants (11,500 of them without German citizenship),

- East Brandenburg : 644,800 inhabitants (2,800 of them without German citizenship).

Important cities in the east of Germany were, among others, Breslau (1925: 614,000 inhabitants), Königsberg i. Pr. (Russian: Kaliningrad , 294,000), Stettin (270,000), Hindenburg OS / Zabrze (132,000) and Gleiwitz (109,000).

Extended definition

In the opinion of some politicians, analogous to the uniform expulsion area according to the Federal Expellees Act , the regions are also assigned to the German eastern areas (not just the Reich) that were part of the German Reich or Austria-Hungary until around 1918 or 1919, and to the German in the interwar period Reich or the Republic of Austria bordered and again belonged to German territory from 1938/39 to 1945 . Many Germans lived here according to their self-identification, language and culture, for whom the term Volksdeutsche was often used and most of them did not have German or Austrian citizenship.

The following areas, which were part of the German Reich until 1919 , had a predominant or high proportion of the German population until the end of the 1940s:

- Memel region (until 1919 as Prussian Lithuania part of the province of East Prussia )

- Province of West Prussia (1939-45 largely forming the Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia )

- Free City of Danzig (until 1919 part of the Province of West Prussia)

- Poznan Province (the historical landscape of Greater Poland )

The following Habsburg-influenced areas , which were part of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy until 1918 , had a predominant or high German population until the end of the 1940s:

- Sudetenland (before 1938 no unit, but parts of the Habsburg crown lands Bohemia , Moravia and Silesia , 1918/19 claimed in vain by German Austria ; later mostly Reichsgau Sudetenland , today part of the Czech Republic )

- Settlement areas of the Danube Swabians in today's Hungary , Croatia and Serbia ( Vojvodina )

- Settlement areas of the Carpathian Germans in today's Slovakia and the Carpathian Ukraine

- Settlement areas of the Transylvanian Saxons , the Banat Swabians and parts of the Bukowina Germans in today's Romania

- Settlement areas of the Galician Germans and parts of the Bukowina Germans in today's Ukraine and Poland

- the Gottschee in today's Slovenia

- South Tyrol , now part of Italy , see option in South Tyrol .

Flight and displacement

The population of the eastern territories of the German Reich was almost completely exchanged between 1944 and 1949 as a result of the flight from the Red Army and the expulsion of the Germans as well as the resettlement of Poles, Ukrainians, Lemks and Russians. Some of the newly settled had been expelled: Between 1.4 and 1.9 million Poles came as a result of Poland's shift to the west from the areas occupied by the Soviet Union east of the Curzon Line. As part of the Vistula campaign in 1947, Ukrainians and Lemks were also forcibly relocated from south-eastern Poland to the former German areas.

The number of German expellees from the eastern regions of the empire (Prussia) alone amounted to:

- East Prussia to 1,890,000,

- Silesia to 3,210,000,

- East Pomerania to 1,470,000 and

- East Brandenburg to 410,000 people.

A total of 6,987,000 Germans had to leave their ancestral home. Almost seven million of them fled to West Germany and the GDR area .

It is estimated that around two million Germans have died as a result of flight and displacement, especially in East Prussia, Pomerania and East Brandenburg. Today around 400,000 Germans still live in the eastern regions, mainly in Upper Silesia . They were discriminated against until the fall of the communist regime . After 1990, many municipalities in Upper Silesia received mayors of German origin, and German schools were also built there - mostly thanks to German funding. In January 2005 the Polish Sejm passed a minority law, according to which bilingual place-name signs can be set up in around 20 municipalities in Upper Silesia with more than 20% German-speaking population and German can be introduced as an auxiliary administrative language.

Economic and social consequences

The eastern areas were dominated by agriculture . Exceptions were the big cities like Königsberg and Breslau as well as the Upper Silesian coal mining area . With the eastern areas Germany lost around a quarter of its agricultural area. Industrial production was until the end well below the Reichs average; While the net production value in the entire Reich was 494 Reichsmarks in 1936, it was 229 in the eastern regions. The social historian Hans-Ulrich Wehler estimates that the loss of these regions through the associated reduction in regional disparities has benefited the economic performance of both German states over the long term. For the Soviet occupation zone and the later GDR, the loss of industrial Silesia and the mouth of the Oder with the important port of Stettin initially meant a considerable economic burden. The economic relations of the companies had to be largely realigned. The Rostock port, selected as a replacement for Stettin, was not only much smaller, it was also not on a navigable river and first had to be expanded into an ocean-going port.

The "destruction of the East German aristocratic world ", which accompanied the loss of the eastern territories and which, as the East Elbe Junker, dominated politics and society in the empire for a long time and still played an inglorious role during the fall of the Weimar Republic , is described by Wehler as an "enormous structural benefit for the development of the Federal Republic ”. In a similar way, the historian Manfred Görtemaker points out that the loss of the eastern territories of the Federal Republic in the agricultural sector saves the tension between the east German estate economy and the family economy , as it was in western and southern Germany , and thus a serious structural deficit of the German Reich stayed.

See also

- Working group of East German family researchers

- Church tracing service

- CEEC

- Polish western thought

- Reichsgau (section "Integrated Eastern Territories (Poland)")

- Association of displaced persons

- Category: List (displaced persons)

literature

- Dieter Blumenwitz : I think of Germany. Answers to the German question. Bavarian State Center for Political Education , Munich 1989, 3 parts (2 volumes, 1 map part).

- Herbert Kraus : The international legal status of the German eastern territories within the imperial borders according to the status of December 31, 1937 , published. von sn, 1962 (177 pages).

- Manfred Raether: Poland's German Past. Schöneck, 2004, ISBN 3-00-012451-9 (new edition as an e-book).

- Fritz Faust: The Potsdam Agreement and its significance under international law. 4., rework. Edition, Metzner, 1969 (420 pages).

Web links

- Official record regarding the designation of the Oder-Neisse areas in official German usage, December 11, 1974 (PDF; 138 kB)

- Jörg-Dieter Gauger : Former German Eastern Territories , Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung - Summary of the programmatic stance of the CDU / CSU (1945–1990)

- Former Eastern Territories (all place names) - Directory of all historical German and current local-language place names that formerly belonged to Germany

- Germans & Poles: “Overview of the places from 1945-2004” , Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg RBB

Individual evidence

- ↑ Cf. Uwe Andersen , Wichard Woyke (ed.): Concise dictionary of the political system of the Federal Republic of Germany , 2nd edition, licensed edition for the Federal Agency for Civic Education , Bonn, Springer, Wiesbaden 1995, p. 548 f. ; Patrick Lehn, Pictures of Germany. Historical school atlases between 1871 and 1990. Ein Handbuch , Böhlau, Cologne 2008, p. 493 ; Otto Kimminich , German Constitutional History , 2nd edition, Baden-Baden 1987, p. 640 ff.

- ↑ a b Werner Abelshauser : German Economic History since 1945. Beck, Munich 2004, p. 62.

- ^ Page with examples from the Reichsgesetzblatt 1941 Part I, table of contents, p. 4 , digitized at alex.onb.ac.at.

- ↑ Oliver Dörr: The incorporation as a fact of state succession , Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1995, p. 344.

- ^ Gerhard L. Weinberg : A world in arms. The global history of World War II , Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1995, p. 669.

- ↑ Dieter Blumenwitz : Oder-Neisse Line . In: Werner Weidenfeld , Karl-Rudolf Korte (ed.): Handbook on German Unity 1949–1989–1999 . Campus, Frankfurt am Main / New York 1999, p. 586.

- ↑ Norman Davies : In the Heart of Europe. History of Poland. CH Beck, Munich 2006, p. 73.

- ↑ Dieter Blumenwitz: Oder-Neisse Line . In: Werner Weidenfeld, Karl-Rudolf Korte (ed.): Handbook on German Unity 1949–1989–1999 . Campus, Frankfurt am Main / New York 1999, p. 586 f.

- ^ Alfred Grosser: History of Germany since 1945 , dtv, Munich 1987, pp. 55–57.

- ↑ Jochen Abr. Frowein : The development of the legal situation in Germany from 1945 to reunification in 1990 , in: Ernst Benda , Werner Maihofer , Hans-Jochen Vogel (ed.): Handbook of Constitutional Law of the Federal Republic of Germany , 2nd edition, de Gruyter, Berlin 1994, p 19–34, here p. 21, marginal no. 5.

- ↑ Susanne Hähnchen: Legal History. From Roman antiquity to modern times , 5th edition, CF Müller, Heidelberg 2016, p. 405, marginal no. 879.

- ↑ a b Gerrit Dworok: "Historikerstreit" und Nationwardung. Origin and interpretation of a Federal Republican conflict . Böhlau, Vienna 2015, ISBN 978-3-412-50238-6 , p. 117 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Henning Köhler : Germany on the way to itself. A history of the century . Hohenheim-Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, p. 440.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler : The long way to the west . German history II. From the “Third Reich” to reunification , CH Beck, Munich 2014, p. 117.

- ^ Wolfgang Benz : Germany under Allied occupation 1945–1949 . In: Gebhardt. Handbook of German History , Vol. 22, 10. neubearb. Ed., Stuttgart 2009, p. 55 ff.

- ^ Andreas Kossert : Back then in East Prussia. The fall of a German province , DVA, Munich 2008, pp. 140, 147.

- ↑ Berhard Kempen : The German-Polish border after the peace settlement of the two-plus-four treaty (= Cologne writings on law and state , volume 1), Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-631-31975-4 , P. 261; Thomas Urban: In heaps behind Oder and Neisse , in: Parliament No. 33–34 of August 11, 2014.

- ↑ See Robert Brier, The Polish “West Thought” after the Second World War 1944–1950 (PDF; 808 kB), Digital Eastern European Library: History 3 (2003).

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: The long way to the west. German history from the “Third Reich” to reunification , Vol. 2, 4th edition, Beck, Munich 2002, p. 151 .

- ↑ Preussische Allgemeine Zeitung , No. 13, April 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Change through ingratiation" ( Rudolf Seiters )

- ^ Ingo von Münch , Staatsrecht, Völkerrecht, Europarecht: Festschrift for Hans-Jürgen Schlochauer on his 75th birthday on March 28, 1981 , Walter de Gruyter, 1981, ISBN 3-11-008118-0 , ISBN 978-3-11-008118 -3 , p. 31 ff.

- ^ Rudolf Laun (Ed.), International Law and Diplomacy , Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, Cologne 1963, p. 11 f.

- ↑ See Joachim Bentzien, The international legal barriers of national sovereignty in the 21st century , Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2007, pp. 68 f. , 71 with further references.

- ↑ Bernhard Kempen, The Distomo case: Greek reparations claims against the Federal Republic of Germany , in: Hans-Joachim Cremer , Thomas Giegerich , Dagmar Richter, Andreas Zimmermann (ed.): Tradition and cosmopolitanism of law. Festschrift for Helmut Steinberger , Springer, Berlin [a. a.] 2002, pp. 179-195, here p. 193 .

- ↑ Due to the border changes carried out in 1938 when the province of Posen-West Prussia was dissolved , the territorial status of 1939 for Silesia, Pomerania and Brandenburg differs from the one existing in 1937.

- ^ Walter Ziegler : Refugees and Displaced Persons , Historisches Lexikon Bayerns , September 6, 2011, accessed on June 14, 2018.

- ↑ Jochen Oltmer: Migration. Forced migrations after the Second World War

- ^ Schlossbauverein Burg an der Wupper eV: The Memorial of the German East ( Memento from October 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society. Vol. 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949. Beck, Munich 2003, p. 946.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society. Vol. 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949. Beck, Munich 2003, p. 956.

- ^ Manfred Görtemaker: History of the Federal Republic of Germany. From the foundation to the present , CH Beck, Munich 1999, p. 165.