Pantheon (Rome)

The pantheon ( ancient Greek Πάνθειον (ἱερόν) or Πάνθεον , from πᾶν pān “all”, “total”, and θεός theós “God”) is an ancient building in Rome that has been consecrated as a church . As a Roman Catholic Church, the official Italian name is Santa Maria ad Martyres ( Latin: Sancta Maria ad Martyres ).

After a name form Sancta Maria Rotunda , which has been in use since the Middle Ages , the building is colloquially referred to in Rome as La Rotonda .

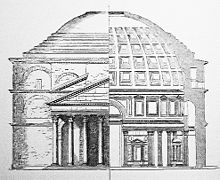

The pantheon, possibly begun under Emperor Trajan around 114 AD and completed under Emperor Hadrian between 125 AD and 128 AD, had the largest dome in the world for more than 1700 years, measured by its inner diameter, and is generally valid as one of the best preserved buildings of Roman antiquity . The Pantheon consists of two main elements: a pronaos with a rectangular floor plan and temple facade in the north and a circular, domed central building in the south. A transition area mediates between both parts of the building, the resulting gussets of the interfaces were used for stairwells.

Built on the Field of Mars , the Pantheon was probably a sanctuary dedicated to all the gods of Rome. The historian Cassius Dio reports that there were statues of Mars and Venus as well as other gods and a statue of Gaius Iulius Caesar , who was accepted as Divus Iulius among the gods . Which gods should be worshiped here is controversial, especially since it has not been fully clarified whether the pantheon was originally a temple or an imperial representative building, which, despite its elements borrowed from sacred architecture , served secular purposes.

On May 13th, probably in the year 609, the Pantheon was converted into a Christian church and consecrated to St. Mary and all Christian martyrs . Masses are celebrated here, especially on high public holidays. The church was built on July 23, 1725 by Pope Benedict XIII. elevated to title diakonia. Pope Pius XI transferred this on May 26, 1929 to the church of Sant'Apollinare alle Terme Neroniane-Alessandrine, 400 meters away . Santa Maria ad Martyres has the title of a minor basilica and is affiliated with the parish of Santa Maria in Aquiro . The building belongs to the Italian state and is maintained by the Ministry of Cultural Goods and Tourism .

The influence of the Pantheon on the history of architecture, especially in modern times, is enormous. The term pantheon is now also generally applied to a building in which important personalities are buried, which stems from the later use of the Roman pantheon.

Building history

The Pantheon is the successor to a temple that Consul Agrippa built after his victory at Actium from 27 to 25 BC. In honor of his friend and patron Augustus had built on the same site. This previous building was already designed as a round building and had roughly the same dimensions and the same orientation as the building that can be seen today. It was damaged in a fire in 80 AD and restored under Emperor Domitian . Clear traces of this measure could not be detected. There may be traces of the floor level between that of the first building and that of the current building.

In 110 the Pantheon burned down again as a result of a lightning strike. Research traditionally attributes the reconstruction to Emperor Hadrian and dates its construction to the years between 118 and 125. The most recent research results, which have not yet been discussed in detail, suggest a construction period from 114 to 119 AD based on brick stamps, i.e. a start of construction under Hadrian's predecessor Trajan . It is not clear who will be the architect of this largest and most perfect rotunda of antiquity. The assignment of the construction planning to the architect Apollodor von Damascus , the leading architect Trajans, who was responsible for numerous large buildings by this emperor, is controversial. It is unanimously assumed that Hadrian dedicated the temple.

Whether and for how long the pantheon was used for ritual purposes cannot be precisely determined due to the lack of literary sources. The historian Cassius Dio mentions that Hadrian held court there. Around the year 230 Iulius Africanus reports on "the beautiful library of the Pantheon, which I myself set up for the emperor". How the passage is to be understood is unclear. Findings that can be linked to a library are not available in the Pantheon itself. By the beginning of the 5th century at the latest, under Emperor Honorius , the temple operations must have been finally stopped. The Eastern Roman Emperor Phokas gave "the temple called the Pantheon" ( templum qui appellatur Pantheum ) in the year 608 to Pope Boniface IV. On May 13, probably in the year 609, he consecrated the Pantheon to the patronage of Sancta Maria ad Martyres , the memory of Mary and all martyrs. This is the origin of the feast of All Saints , which has been celebrated in the Western Church since 835 on November 1st . According to a medieval legend, which is probably first available in print from Pompeo Ugonio (around 1550–1614), Boniface IV had 28 truckloads with the bones of martyrs brought from the catacombs to the church.

When the Eastern Roman Emperor Konstans II visited Rome in 663, he had the gilded bronze plates of the dome cladding removed and transported to Constantinople . Pope Gregory III 735 provided a new lead roof. At an unknown point in post-ancient times, two columns on the east side of the pronaos were removed, which Pope Alexander VII had replaced with columns from the Nerotherms in the 17th century .

In 1270 a Romanesque bell tower was built over the Pronaos. In the course of the 15th and 16th centuries, the square in front of the Pantheon was cleared and leveled on behalf of several popes, so that today's Piazza della Rotonda was created. Since the 16th century the Pantheon became the church of the Holy Sepulcher of important personalities, later also of the Italian royal family. In the 17th century, Pope Urban VIII from the Barberini family had the bronze plates that clad the roof of the pronaos removed and had them mostly made into 80 cannons for the Castel Sant'Angelo , but also some for the ciborium of St. Peter's Basilica use. The population of Rome then coined the proverb Quod non fecerunt barbari, fecerunt Barberini “What the barbarians couldn't do, the Barberini did”. Instead of the 13th-century bell tower, Urban had two Bernini- designed towers built in the east and west of the pronaos. In 1883 these were torn down again.

Overall, the Pantheon is one of the best-preserved buildings from Roman antiquity, which is mainly due to its very early conversion into a church.

Building description

Agrippa's pantheon

Agrippa had his building built on the Field of Mars on the site that had previously belonged to Pompey and then to Mark Antony . In the immediate vicinity there were other construction projects he had planned and financed, such as the Agrippa thermal baths or the Saepta Iulia , a large assembly hall, the construction of which Caesar had already started. The main features of Agrippa's pantheon anticipated Hadrian's system. It had a broad rectangular pronaos of approx. 44 m × 20 m. A rotunda followed in the south. The older pronaos, the remains of which were found during excavations carried out in 1892/1893 and 1996/1997, was in the same place as the one of the successor building, but was somewhat wider. If it was previously assumed that the building of Agrippa was oriented exactly the other way around compared to the existing building of Hadrian and referred to the Augustus mausoleum to the north, the results of the excavations in the 1990s suggest that there was no reorientation of the new building under Hadrian, but Hadrian's architect followed the Augustan pantheon in this regard. This had either a ten-column front or an eight-column between protruding ante . Statues of Augustus and Agrippa were placed in the pronaos . During the excavations in the area of the rotunda, a round wall was found that enclosed the same area as the later rotunda. In contrast to the successor building, this part of the building was not roofed over. It was a circular building or open courtyard about 44 meters in diameter, surrounded by a wall about two meters high and paved with slabs of pavonazzetto (a marble from the Dokimeion quarries ), white marble and travertine . Its interior design is unclear. Cassius Dio narrates that statues of gods (he names Mars and Venus ) and a statue of Caesar were erected here.

This Agrippa building was damaged by fire in 80 and is listed among the buildings restored by Domitian. The complete redesign in Hadrianic times was preceded by a devastating fire in 110 under Trajan.

The pantheon of Hadrian times

The forecourt

To the north of the Pantheon is now the Piazza della Rotonda with the Egyptian obelisk erected there. In Hadrian's time , the street level was between 1.50 and 2.50 m below today's level. A square paved with travertine slabs led to the north entrance of the building and was bordered by porticos at right angles to the west, north and east. The halls were supported by columns made of gray granite and were based on a series of five marble steps ( Giallo antico ). The pronaos of the Pantheon was connected to the pillared halls in the west and in the east by a fountain basin made of Proennesian marble. The two statues of the river gods Tiber and Nile , which are now placed on Capitol Square , could originally have served as fountain figures here.

Due to the modern development of the area north of the Pantheon, the archaeological findings on the entire forecourt are very sparse. For example, the exact location and appearance of the northern portico remain pure speculation, as there are no findings on this. A structure that was in the center of the square can no longer be clearly identified today.

The pronaos

The pronaos in front of the rotunda in the north gives the impression of a typical Roman podium temple . It has a rectangular floor plan measuring 33.10 × 15.50 meters and is only accessible from the northern side. While today a three-step staircase extends over almost the entire north side of the Pronaos, its 1.50 meter high podium was originally only accessible via two 7.30 meter wide stairs. The north facade is structured by a column arrangement made of eight non-fluted Corinthian columns made of gray Egyptian granite by Mons Claudianus with column bases made of marble , while the other columns of the pronaos are made of red granite. The short sides are two column positions deep. The inscription on the frieze in which Agrippa is mentioned comes from Hadrianic times. A second inscription mentions a restoration of the building in 202 AD by the emperors Septimius Severus and Caracalla . The gable field above is empty today, but was probably adorned in antiquity by an eagle that held the Corona civica in its claws.

The interior of the pronaos is divided into three naves by four non-fluted Corinthian columns and is reminiscent of the typical Etruscan- Roman temple. The floor is covered with slabs of marble, granite and travertine , which form simple circular and rectangular patterns. The two side aisles end in the south with an apse , where statues of Augustus and Agrippa were probably originally placed. The south wall of the pronaos is richly decorated with marble slabs and is structured by Corinthian marble pilasters . In ancient times, the wooden beams of the roof structure were covered with bronze panels. The central nave, which is wider than the aisles, ends with a 6-meter-high bronze door , which could be the reused door from the Agrippa building. You enter the rotunda through them.

From the outside you can see that the gable roof of the pronaos extends to the height of the dome attachment point. On the narrow sides of the pronaos, the architrave , frieze and geison continue to the rotunda, the side column position ends in marble pilasters. Above the pronaos, the building has no further incrustations and is only structured by a tympanum between two cornices .

The rotunda

The most important building component of the Pantheon is a vaulted round building of 43.30 m (that is 150 Roman feet ) inside diameter and height. The load-bearing masonry consists of Opus caementicium , a cast masonry, with bricks as lost formwork, interrupted by compensation layers . The leveling layers consist of travertine and tuff in the lower area , bricks in the middle and mostly tuff in the upper area, so that the weight decreases with height. In the dome, the addition consists of light lapilli tuff . The load-bearing walls rest on a 7.50 m wide and 4.60 m deep ring-shaped foundation made of cast masonry with travertine as compensation layers. The outer facade of this rotunda is designed simply and is only structured by three cornices. Semicircular relief arches made of bricks, which absorb the enormous pressure of the dome , are clearly visible . Today there are no traces that would suggest that the facade was clad with marble slabs in ancient times .

The rotunda conveys a completely different feeling of space than the pronaos. Its typical structure of a rectangular Roman podium temple is contrasted by the circular interior, dominated by the dome, which has no model in terms of dimensions in Roman temple architecture. The original, rich furnishing of the interior with different colored stone from all parts of the Mediterranean has been preserved in its basic features to this day. The floor picks up on the design in the pronaos and is covered with a pattern of large squares and circles made of porphyry , gray granite and Giallo Antico (the coveted yellow marble from Simitthu ), which are framed by strips of pavonazzetto . The surrounding wall is divided into two decorative zones. In the lower zone, the wall is divided by seven niches and the entrance portal. Only the barrel vault above the entrance and the dome of the southern niche cut into the upper wall zone. The niches have an alternating semicircular and rectangular floor plan. They are framed by corner pillars with Corinthian capitals . Set in the niches are two fluted Corinthian columns . With the exception of the southern one, there are three aedicules in each of the remaining niches . Statues of deserving Romans from republican times were possibly placed here in antiquity . Aedicules are also faded in between the individual niches. The remaining wall parts of the lower decorative zone are covered with a geometric pattern of circular and rectangular fields made of different colored stone. At the top, the lower zone closes with a richly decorated entablature . The incrustation of the attic zone above is no longer original today, but can be reconstructed in a short section based on drawings by Baldassare Peruzzi and Raffael . It was covered with a similar but more delicate pattern to the lower zone.

A dome forms the ceiling of the building. It has a diameter of about 43.45 m at almost half the stitch height . Completed into a ball, it would run about half a meter below the ground. The dome's Roman concrete was mixed from light volcanic tuff and pumice stone . To save even more weight, the dome is divided into five concentric rings made up of 28 cassettes each, with the cassettes of the individual rings becoming smaller and smaller towards the top. The arrangement of the cassettes does not correspond to that of the wall below, but is slightly offset. Originally the inside of the dome was painted and each cassette had a bronze , possibly gilded star or rosette . At the apex of the dome there is a circular opening nine meters in diameter, the Opaion , which, apart from the entrance portal, is the only source of light in the interior. In order to drain off the rainwater that penetrates through this, the floor of the domed hall is slightly inclined towards the center and provided with 22 small drains at favorable points. On the outside, the wall below the dome is higher than in the interior, so that the dome - viewed from the outside - does not represent a complete hemisphere. The outside of the dome is covered with bronze panels, the ancient originals of which, however, are no longer preserved.

interpretation

The name Pantheon, which has only been proven a few times in antiquity, suggests consecration to all or at least several gods. It remains unclear exactly which deities were worshiped in the pantheon. Statues of gods erected within the sanctuary are mentioned by Cassius Dio (53, 27), but he only mentions Mars , Venus and Divus Iulius by name . One possibility would be to reconstruct the worship of all the star and week gods, including Sol , Luna , Mercurius , Jupiter and Saturnus . It is also conceivable that Agrippa planned a sanctuary for Augustus and his family, the Julian-Claudian dynasty , as well as their divine ancestors and patrons. This is supported by the installation of a statue of Caesar, Augustus' deified adoptive father, in the sanctuary mentioned by Cassius Dio. A comparable facility, the Nemrut Dağı , is known from the small Hellenistic kingdom of Kommagene , but here in connection with royal burials. Cassius Dio further reports that Augustus ordered that his statue should not be placed in the sanctuary, but outside, in the pronaos. A divine veneration of his person while he was still alive would hardly have suited the image of primus inter pares that Augustus had propagated.

A round, open courtyard, which is bordered by a wall and can be entered via a gate with a rectangular floor plan, is known as a sanctuary from Roman architectural history from the time before Augustus. It seems to be a particularly venerable old Italian building type, which is why Agrippa chose it for his monument. By adding the temple-like pronaos and its unusual size, however, it gave it a monumentality that comparable older systems had not possessed. The same approach of combining ancient Italian building forms with precious materials or monumental dimensions can also be found in other buildings from the time of Augustus, such as the Ara Pacis or the Augustus mausoleum .

When Hadrian had the Pantheon rebuilt, he decided not to have his name attached to the building and named Agrippa as the builder in the inscription on the frieze of Pronaos Agrippa. This corresponds entirely to Hadrian's policy, who was able to stage his virtuous restraint in this way. There is no reason to believe that the Hadrian pantheon did not serve basically the same purpose as its Augustan predecessor. The design of the domed central area that has now been chosen does not find any models in the temple architecture of the time. Wolfram Martini therefore put forward the thesis that Hadrian's Pantheon was originally not a sacred building, but an emperor's hall, an audience and court room, as part of an imperial forum. He draws parallels to domed halls in the imperial palace architecture, for example to the Domus Aurea Nero , but does not include Agrippa's predecessor building and its significance in his thesis. The spherical dome depicting the sky, the opaion as an opening to the stars, whose light wanders over the dome in the course of the day, as well as the seven wall niches indicate that the Hadrian pantheon was used as a temple for the celestial deities. In the new building, too, the Opaion creates a direct connection to the open sky, which was an important element in Agrippa's pantheon and which threatened to be lost when the dome was erected.

Since the late 1990s, research approaches outside of classical studies and building research have asserted that the metrics of the building followed the attempt of the New Pythagorean philosophy to integrate the sciences of the quadrivium - arithmetic , geometry , music and astronomy - into a harmonious whole. The pantheon would therefore be an image of the Pythagorean cosmos in mathematical implementation.

Use as a burial site

From the Renaissance onwards , the Pantheon, in its function as a church, became the burial place of important artistic personalities, among others for:

- the painter Raffael (1483–1520)

- the architect Baldassare Peruzzi (1481–1536)

- the painter Perino del Vaga (1501–1547)

- the painter Giovanni da Udine (1487–1564)

- the painter Taddeo Zuccari (1529–1566)

- the painter Annibale Carracci (1560–1609)

- the composer Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713)

Raphael was buried in an ancient Roman sarcophagus to which a distich by Pietro Bembo was attached. Other people also found their final resting place in the Pantheon, for example Raphael's fiancée Maria Bibbiena, and the heart of Cardinal Ercole Consalvi was buried here. After the unification of Italy the building then served as grave lay the first two Italian kings Victor Emmanuel II. And Umberto I. Also Margherita of Savoy , wife of Umberto I, has its tomb in the Pantheon. The last Italian King Viktor Emanuel III, who died in exile . the pantheon was denied as a resting place because of its dubious role played during the time of fascism .

In contrast to the other churches in Rome, which belong to the respective religious community - i.e. in the vast majority of cases the Catholic Church - the Pantheon (like the Church of Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri ) is owned by the Italian state.

Aftermath

The pantheon as an architectural model

Buildings based on the architecture of the Pantheon, such as the Temple of Zeus Asklepios in the Asklepieion of Pergamon, built under Hadrian, were built in ancient times .

From the early modern period, the influence of the pantheon on architectural history became particularly strong. It became the prototype for countless domed structures from the Renaissance to the 20th century, for example:

- the Villa La Rotonda near Vicenza, architect: Andrea Palladio , around 1590

- the St. Peter's Basilica in Rome: Michelangelo and Giacomo della Porta, 1560-1600

- the Invalides in Paris, architect: Jules Hardouin-Mansart , around 1690

- the monastery church of St. Blasien in the Black Forest, architect: Pierre Michel d'Ixnard , 1772

- the Sainte-Geneviève church (later the Panthéon ) in Paris, architect: Jacques-Germain Soufflot , around 1780

- the Capitol in Washington (with steel dome), architect: William Thornton , around 1800

- the Church of St. Stephan in Karlsruhe, architect: Friedrich Weinbrenner , around 1810

- the Rotunda of the University of Virginia , architect: Thomas Jefferson , around 1820

- the Old Museum in Berlin, architect: Karl Friedrich Schinkel , around 1830

- the Church of St. Petrus in Gesmold, architect: Emanuel Bruno Quaet-Faslem , 1836

- the Berlin Cathedral , architect: Julius Raschdorff , around 1900.

- the Oberdischinger village church "Swabian Pantheon"

Its strict spatial program was also a model for revolutionary architecture towards the end of the 18th century. The Great Hall in Berlin planned by Albert Speer also shows clear references to the Pantheon.

La Rotonda by Andrea Palladio near Vicenza

The " Rotunda " of the University of Virginia

The dome of the rotunda in the Altes Museum in Berlin

Kerek templom ("round church") in Balatonfüred , Hungary

Dome with angels and saints, St. Peter Church (Gesmold)

St. Hedwig's Cathedral in Berlin

Centennial Hall in Wroclaw (Breslau), Poland

Baldwin Auditorium (1927) at Duke University , USA

The pantheon as namesake

Due to its later use as a Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the building also gave its name to other burial places of nationally important people, such as the aforementioned Panthéon in Paris, the Pantheon of the Spanish Kings in the Escorial or the Pantheon in Tbilisi .

Technical specifications

- Dome inside diameter (ø): 43.45 m

- Dome shell thickness (KSD): 1.35 m

- KSD to ø: 1:32

- Dome material: concrete (Opus caementicium)

- Floor plan: rotunda

- Ring wall thickness (RD): 5.93 m

- RD to ø: 1: 7.3

- Diameter Opaion (DO): 8.95 m

- DO at ø: 1: 4.9

organ

The organ was built during the restoration work from 1925 to 1933 by the organ building company Tamburini. The instrument has 8 manual registers , which can be registered on two manual works, and 2 pedal registers. The actions are electric. The restoration of the organ, which became necessary due to the dampness of the building, was also carried out in 2003 by the Tamburini company.

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Coupling: I / I (super-octave coupling), II / I (also as sub-octave coupling), I / P, II / P

photos

See also

- List of Roman domes

- List of the largest domes of their time

- List of Cardinal Deacons of Santa Maria ad Martyres

literature

- Kjeld De Fine Licht: The Rotunda in Rome. A study of Hadrian's Pantheon . Copenhagen 1968.

- Christoph Grau: Pantheon Project . Textem, Hamburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-941613-30-0 .

- Doris and Gottfried Gruben : The door of the Pantheon . In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute. Roman department . Volume 104, 1997, pp. 3-74.

- Andreas Grüner: The Pantheon and its role models . In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute. Roman department . Volume 111, 2004, pp. 495-512.

- Gerd Heene: Pantheon construction site. Planning, construction, logistics. Bau + Technik, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-7640-0448-7 .

- Wolf-Dieter Heilmeyer : Apollodorus of Damascus, the architect of the Pantheon . In: Yearbook of the German Archaeological Institute . Volume 90, 1975, pp. 316-347, ISSN 0070-4415 .

- Wolf-Dieter Heilmeyer, Ellen Schraudolph, Hildegard Wiewelhove: The glory of the Pantheon . Antikensammlung Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 1992, ISBN 3-88609-276-3 .

- Heinz-Otto Lamprecht: Opus caementitium. Construction technology of the Romans. Römisch-Germanisches Museum, Cologne, 5th edition. Beton-Verlag, Düsseldorf 2001, ISBN 3-7640-0350-2 .

- Tod A. Marder, Mark Wilson Jones: The Pantheon: From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press, New York 2015.

- Wolfram Martini : Hadrian's Pantheon in Rome. The building and its interpretation (= meeting reports of the Scientific Society at the JW Goethe University Frankfurt am Main. Volume XLIV, number 1). Steiner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-515-08859-6 .

- Rainer Norten: The pantheon idea around 1800: Investigations into the appearance of the rotunda in the old and new building tasks in the age of classicism in Germany , Berlin 1986, DNB 861235215 (dissertation TU Berlin 1986, 315 pages).

- Jürgen Rasch: The dome in Roman architecture. Development, design, construction . In: Architectura . Volume 15, 1985, pp. 117-139.

- Norbert Reiss: The Roman Pantheon: a psychoanalytical walk through the concept of sublimation, the promise of salvation and the sublime. Berlin 1990, DNB 947038566 (dissertation FU Berlin 1991).

- Lambert Rosenbusch (Ed.): Pantheon. Second Scientific Meeting. Helms, Schwerin 2002, ISBN 3-935749-12-0 English .

- Gert Sperling: The Pantheon in Rome. Image and measure of the cosmos. Ars Una, Neuried 1999, ISBN 3-89391-854-X .

- A four-legged spider to close the dome . In: FAZ , October 4, 2007, on the reconstruction of the structural engineering (Heene book).

- Dierk Thode: Studies on load transfer in late antique domed buildings (= studies on building research. Number 9). Koldewey Society, Darmstadt 1975, DNB 760439206 Dissertation TH Darmstadt, 1975).

Web links

- Pantheon project of the Kármán Center of the University of Bern, Bibliography, Sections based on digital Laser Scanning Data etc. (English)

- Pantheon in the Arachne archaeological database

- The pantheon . die-roemer-online.de, short presentation

- The Roman Pantheon: The Triumph of Concrete . on the cement of the Pantheon

- Pantheon: historical information and photos (English, Italian)

photos

- Pantheon, Rome Virtual panoramas and photo gallery (Italian, English, French)

- Italy, Rome, Pantheon Virtual Tour with map and compass effect by Tolomeus (English)

- Pantheon Rome Virtual Tour, 360 ° IPIX PANORAMA

- Pantheon in ancient views and literary evidence

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gert Sperling: The Pantheon in Rome, image and measure of the cosmos. Foreword VII-XVI and introduction pp. 1–12.

- ^ Diocese of Rome

- ↑ http://www.polomusealelazio.beniculturali.it/index.php?it/232/pantheon Homepage of the Ministry of Cultural Property and Tourism

- ↑ Doris and Gottfried Gruben : The door of the Pantheon. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute. Roman department. Volume 104, 1997, pp. 3-74, here: p. 59; the “Domitian” (?) level illustrated by Luca Beltrami: Il Pantheon: La struttura organica della cupola e del sottostante tamburo, le fondazioni della rotonda, dell 'avancorpo, e del portico, avanzi degli edifici anteriori alle costruzioni adrianee. Relazione delle indagini eseguite dal R. Ministero della Pubblica Istruzione negli anni 1892–93, coi rilievi e disegni dell 'architetto Pier Olinto Armanini. Milan 1898, p. 48, fig. 15 ( PDF ).

- ^ Lise M. Hetland: Dating the Pantheon. In: Journal of Roman Archeology. 20, 2007, pp. 95-112; see. Geneviève Lüscher : The emperor's new bricks. In: The time . Number 52/2006; Rejecting Mary T. Boatwright: Hadrian and the Agrippa Inscription of the Pantheon. In: Thorsten Opper (ed.): Hadrian. Art, Politics and Economy. British Museum, London 2013, pp. 19–30. Lothar Haselberger and Doris Gruben, for example, calculate that construction will start 114/115; Lothar Haselberger: Deciphering an ancient work plan. In: Spectrum of Science. August 1995, p. 296 f .; Doris Gruben, Gottfried Gruben : The door of the Pantheon. In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Roman Department. Volume 104, 1997, pp. 3-74.

- ^ Wolf-Dieter Heilmeyer : Apollodorus of Damascus, the architect of the Pantheon. In: Yearbook of the German Archaeological Institute . Volume 90, 1975, pp. 316-347; supportive Lothar Haselberger: A gable crack in the vestibule of the Pantheon. The cracks in the works in front of the Augustus mausoleum. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologische Institut, Roman Department, Volume 101, 1994, pp. 279–309, here pp. 296–298; on the other hand, skeptical about Christoph Höcker : Apollodorus [14]. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 1, Metzler, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-476-01471-1 ..

- ↑ Cassius Dio 69 (68), 7.1.

- ↑ Papyrus Oxyrhynchus III 412: ἐν ῾Ρώμῃ πρὸς ταῖς ᾿Αλεξάνδρου θερμαῖς ἐν τῇ ἐν Πανθείῳ βιβλιοθήκῃ τῇ καῷλη ἣν αότΣτ in the Roman pantheon καheλη ἣν αότΣη set up in the pantheon of the Alexander κheτατατατατῷτ in the κheτατατατα σ in the pantheon of the κheτατατατα στΣη of the κheτατατα όν αότἣτ in the panthe of Alexander have "( digitized version ).

- ↑ It is possible that Iulius Africanus only wrote more generally about the "Pantheon Complex" renewed by Severus Alexander , which included not only the inscribed work on the Pantheon itself, but also renovations of the baths of Nero , which then bore the name of Alexander; for problems with older literature see Jürgen Hammerstaedt : Julius Africanus and his activity in the 18th Kestos (P.Oxy. 412 col. II). In: Martin Wallraff , Laura Mecella (ed.): The Kestoi of Julius Africanus and their tradition (= texts and studies on the history of early Christian literature . Volume 165). De Gruyter, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-021958-6 , pp. 53–70, here: pp. 66–68.

- ↑ Liber pontificalis 69.2 (I 317.2 / 4 Duchesne ) ( digitized version ).

- ↑ For the consecration on May 13, see Theodor Klauser : Das Roman Capitulare Evangeliorum. Texts and studies on its oldest history (= sources and research on liturgy history . Volume 28). 2nd Edition. Aschendorff, Münster 1972, p. 73; for a dating to the year 613 see Sible De Blaauw: The Pantheon as a Christian Temple. In: Ulrich Real, Martina Jordan-Ruwe (Ed.): Image and formal language of late antique art. Hugo Brandenburg for his 65th birthday (= Boreas. Munster contributions to archeology. Volume 17). Münster 1994, pp. 13-26 ( online ); for a dating to the year 609 with a discussion of older approaches see Martin Wallraff : Pantheon und Allerheiligen. In: Yearbook for Antiquity and Christianity . Volume 47, 2004, pp. 128-143; here: p. 139 with note 55 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Martin Wallraff: Pantheon and All Saints. In: Yearbook for Antiquity and Christianity. Volume 47, 2004, pp. 128-143.

- ↑ Pompeo Ugonio: Historia delle stationi di Roma che si la Celebrano Lent. Rome 1588, fol. 313 ( Google Books ).

- ↑ Cf. Martin Wallraff: Pantheon and Allerheiligen. In: Yearbook for Antiquity and Christianity. Volume 47, 2004, pp. 128-143; here: p. 141 with note 63.

- ↑ Liber Pontificalis 78.3 (I 343.14 / 15 Duchesne) ( digitized version ); Paulus Deacon , Historia Langobardorum 5:11.

- ↑ Liber Pontificalis 92.12 (I 419.17 / 18 Duchesne) ( digitized version ).

- ↑ For the relevant inscription, which is now placed in the pronaos of the Pantheon, see Fine Licht: The Rotunda in Rome. P. 240. 312 note 10.

- ↑ Saepta Iulia .

- ↑ On Agrippa's Pantheon : Eugenio La Rocca: Agrippa's Pantheon and Its Origin. In: Tod A. Marder, Mark Wilson Jones (Ed.): The Pantheon. From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press 2015, pp. 49-78 ( online ).

- ↑ Cassius Dio 53,27,1-2.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 66:24.

- ↑ Chronograph from 354 , chron. 1.146 ( online )

- ↑ Orosius , Historiae adversum paganos 7,12,5; Hieronymus , chronikon 195 e.

- ^ Martini: Hadrian's Pantheon in Rome . P. 13 f.

- ↑ CIL 6, 896 : M (arcus) Agrippa L (uci) f (ilius) co (n) s (ul) tertium fecit "Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, consul for the third time, built (it)."

- ↑ CIL 6, 896 , line 2 ff. […] Pantheum vetustate corruptum cum omni cultu restituerunt.

- ^ Fine light: The Rotunda in Rome. P. 45 f.

- ↑ Gottfried Gruben : The door of the Pantheon . Gruben is based on an older reconstruction of the Augustan building, according to which the Pantheon was entered from the south via a semicircular courtyard in the area of the later rotunda and a rectangular cella was located in the area of the later pronaos. However, his thesis about a possible reuse of the bronze doors remains applicable to the current reconstruction of the Agrippa building; see. on this Lise M. Hetland: New Perspectives on the Dating of the Pantheon. In: Tod A. Marder, Mark Wilson Jones (Ed.): The Pantheon. From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press 2015, pp. 79-98 ( online ).

- ^ Giangiacomo Martines: Four The Conception and Construction of Drum and Dome. In: Tod A. Marder, Mark Wilson Jones (Ed.): The Pantheon. From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press 2015, pp. 99–131, here p. 102 ( online ).

- ^ Filippo Coarelli : Rome. An archaeological guide. Verlag von Zabern, Mainz 2000, ISBN 3-8053-2685-8 , pp. 55–109, here: p. 282.

- ^ Duncan Garwood, Abigail Hole: Rome . 4th edition. 2012, ISBN 978-3-8297-2258-2 , pp. 80 .

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, for example, uses the term pantheum in his Naturalis historia , e.g. B. 36, 38: Agrippae Pantheum decoravit Diogenes Atheniensis; in columnis templi eius Caryatides probantur inter pauca operum, sicut in fastigio posita signa, sed propter altitudinem loci minus celebrata “Diogenes of Athens furnished the pantheon of Agrippa; his caryatids on the pillars of the temple are judged as rare works of art, as are the portraits that are placed on the gable, but these are praised to a lesser extent due to the high location of this place. "

- ^ Martini: Hadrian's Pantheon in Rome . P. 39 f.

- ↑ Grüner: The Pantheon and its models .

- ^ Wolfram Martini: Hadrian's Pantheon in Rome .

- ^ Gert Sperling: The “Quadrivium” in the Pantheon of Rome. In: Kim Williams, Michael J. Ostwald (Eds.): Nexus II: Architecture and Mathematics. Edizioni dell'Erba, Fucecchio (Florence) 1998, pp. 127-142.

- ↑ Siegfried Winkler: The quote in architecture using the example of the pantheon reception. Dissertation Göttingen 2016, available as a PDF on [1] , last accessed on June 29, 2019.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Rasch: The dome in Roman architecture. Development, design, construction .

- ↑ Information on the organ (PDF; 4.9 MB) pfarre.kirche.at, p. 142

Coordinates: 41 ° 53 ′ 55 " N , 12 ° 28 ′ 37" E