Mountain pass

As a mountain pass or short -pass is called the transition to the view of the Talbewohners lying beyond the mountains Valley . The lowest possible passable point of a ridge , ridge or ridge between two mountain sticks or chains is suitable as a transition .

On the orographic-landscape concept

A pass as a term encompasses more than just the orographic pass height (geometric saddle point ) in the basic terrain of the mountain saddle . The area surrounding the saddle as well as the access or driveways from the respective valley locations to them, i.e. the areas and structures functionally connected to the altitude, are also included.

The pass usually also crosses a watershed at the saddle point . In addition, the word can also be found in the term valley pass , which are narrow valleys that correspond to a mountain pass in terms of their settlement and traffic geographic characteristics, but do not represent a watershed, but a valley section along a watercourse . The two terms can also merge into one another: Prototype mountain passes are characteristic of geologically young fold and chain mountains . In mountains with massive characteristics (individual island peaks), as well as in landscapes with dry valleys , in which no explicit watercourses characterize the terrain, valley pass and mountain pass often coincide. In rump landscapes and in foothills and foothills and hill regions , numerous passes are formed that are not orographically distinctive saddles or transitions that are outstanding in terms of traffic geography. Then the term is extended to pass landscape , meaning small or large-scale high altitudes between valleys of all kinds.

Apart from this, the term pass height is also used to indicate the absolute height of a pass above sea level in meters or feet, i.e. the cartographic-geometric culmination point of the transition. This does not have to coincide with the orographically lowest point, for example if it is impassable or the pass path tunnels under the actual pass height ( pass or peak tunnel ).

Geomorphology and geology

In geoscientific theory and geomorphology , depressions within a mountain ridge are generally referred to as saddle or notch , depending on whether the ridge and valley lines are U or V-shaped. The pass is the upper culmination (upper extremum) of a valley line and the minimum (lower extremum) of a ridge line. Mathematically, the saddle point is defined with the alternating sign of the radius of curvature along two characteristic axes (in this case the valley and the ridge / ridge line of the terrain profile), especially with a local level: Otherwise at least one of the two lines has a kink ( point of discontinuity in the slope ). This makes the saddle and notch two basic relief elements .

From a geological- geomorphogenetic point of view, such a depression can result from local weathering differences, e.g. B. if the rocks on both sides of the later pass have a different hardness . A rock cut can also arise from regional tectonics or from rock-mechanical or geological fault lines . Transfluence saddles go back to glacial grinding, which also mostly follows the lines given by tectonics and petrography .

In geology, the topology is called antiform when it relates to stratification within the rock.

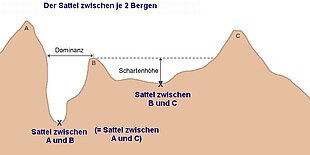

Important orographic dimensions of a summit or a summit formation (up to mountains) to the saddle / saddle that marks the deepest contour line completely surrounding it , in which there is no significant other summit, are the notch height as the difference in height and the dominance as the distance to the next higher point - not necessarily related to the same pass. They serve to quantify the terrain profile and characterize peaks.

On the transport geographic term

If a footpath or a road uses a low point of a mountain ridge as a transition between two valleys, the pass road or road pass becomes a synonym for the term pass .

The number of mountain passes in the narrower sense does not increase significantly due to the ever denser road network in the mountains. In this way, roads in the Alps were connected, which existed as ways to develop the Alps or were built for the construction of leisure facilities, power stations and high-voltage lines as well as for military reasons. In many places more horizontal connections were built; On such roads it is possible to connect two valley locations via a culmination point, but one can hardly speak of a pass. Here one speaks of Höhenstraße . Even in non-alpine regions, today's network of paths and roads is so dense, well-developed and easily accessible by motorized vehicles that the term pass is rarely used for mountain routes.

There are also passes with a subordinate watershed, such as the Kunkelspass , which leads from the Rhine via the Tamina valley back to the Rhine, the Finstermünzpass , which bypasses the Inn gorges on the Swiss-Austrian border (this is where the name of the actual valley pass, the Finstermünz gorge , goes , to the top of the pass, which connects two local side valleys; today more extensive tunneled under), or the Chaiber Pass , whose road south of the Kabul River bypasses its impassable gorges.

The history of many passes as points of concentration of paths connecting people and countries over thousands of years has been documented by excavations . Examples are ancient streets and the ancient Roman roads , and the discovery of the glacier corpse Ötzi brought a new image of high alpine crossings .

The importance of such concentration points changed in the course of history due to the increasing technical possibilities. The Gotthard Pass was only able to exploit its shortness of connection after a hanging bridge construction ( Twärren Bridge ) that horses could walk on had made the rock walls of the Schöllenen Gorge in the northern access passable. Geographically, this point had little to do with the actually favorable low point of the transition over the Alps, but it was crucial in terms of traffic. On the other hand, the Septimer pass in Graubünden had already been expanded into a small road around 1400 and still lost all importance after other roads could also be built. With the acceleration due to the construction of driveways, entire valley communities lost their livelihood on many routes, which were often shorter for mule- haulers. But also important passes with routes have been replaced by other traffic-related innovations, such as the Splügen Pass , when the transalpine railways were built, or the Lötschberg , where a pass lost its role in long-distance traffic due to the construction of a top tunnel and is now hardly recognized as a historical trade route is imaginable.

Names for mountain crossings

There are numerous oronymics that reflect the landscape of a cut. A settlement or field name with such words consistently indicates a landmark - at least in historical local pedestrian traffic - relevant pass crossing: especially in the mountains, completely impassable passes are mostly unnamed: until the end of the 18th century, mountains were only climbed in exceptional cases and were before all an obstacle on the way to the other side that one preferred to avoid. "Going over the mountain or the mountains" always referred to the most efficient passage, the pass. Prominent examples of this are Arlberg and Lötschberg . In the Walser language , mountain still means a pass crossing and the area on both sides ( Hochtannberg ) . In the case of extensive high valleys accessible from both sides, the alpine region gave its name ( Oberalppass , Schwägalp ) . In fact, it is assumed that many mountain names actually go back to the top of the pass, as can be seen prototypically on the Tauern . The name of the Alps themselves, the etymology of which is unclear, could also be derived from this.

The word pass itself comes from the Latin passus , the 'step', passare '[over-, passing-] to go', which also includes passage , pass , passenger or the passport . These words show the close relationship in meaning to the traffic-relevant term. The word is Italian passo , Spanish paso (cf. El Paso , but not French) as native as English pass .

Originally - and still in vernacular today - well-known passports do not have a generic word, they are called St. Bernhard, Splügen , Umbrail , Brenner, Wechsel (sic), Semmering , Loibl / Ljubelj . The appended "-pass" is used in writing to differentiate between, for example, pass settlements (such as the town of Semmering ), and leads to incorrect duplication of terms ( Furkajoch , Predilpass , Prekowa-Höhe - 'Pass-Pass') when copying from other languages . A special case is prefixed in Salzburg: Pass Thurn , Pass Strub (also Talpass Pass Lueg ; formed accordingly: Pass Lunghin , Graubünden).

Other names for mountain passes in German are:

- Mountain : z. B. Arlberg , Lötschberg , Seebergsattel (duplication)

- Bichl, Bühel ' Hügel ': z. B. Präbichl

- Corner, Eck, Egg (generally 'terrain edge'): z. B. Scheidegg , Perfalleck , Goldfinch Corner (Harz)

- Neck: e.g. B. Neck

- Height : z. B. Bielerhöhe

- Joch (Jöchl, Jöchle, Jöchli) : e.g. B. Stilfser Joch , Timmelsjoch

- Gap , e.g. B. Birnlücke , Wallücke (Wiehengebirge)

- Saddle : z. B. Kreuzbergsattel , Perchauer Sattel

- Scharte (often, mostly only accessible on foot)

- Scheid, Gscheid (cf. Wasserscheide , second 'Gescheide'): z. B. Preiner Gscheid , Scheidegg

- Tor, Törl : Hochtor , Fuscher Törl , Drusator ; Low German Döhre z. B. at the Teutoburg Forest

- Change

In other languages (according to Abc):

- Italian bocchetta (B ta ) 'saddle'

- Ladin col (from Latin collis 'hill, hill', see mountain name Col di Lana : collum 'neck; mountain pass, transition'): Italian colle , French col 'saddle', but English col 'saddle'

- Norwegian fjellet (determined to be fjell 'mountain')

- Ladin forc- ('furrow', a mountain cut): Italian forcella (Forc la ) , also dialectal forcola , Rhaeto-Romanic fuorcla ; z. B. Forcola di Livigno , Passo della Forcella , Col de la Forclaz , taken over in German Furkapass , Furkajoch , Furkelpass (the latter all have double names)

- English gap 'gap', mountaineering language

- Italian giogo 'yoke'

- Latin porta 'gate', often about Spanish puerta , Catalan port (in the Pyrenees), French Port de Lers , also in the Porta Westfalica and as a gate landscape

- Old Slavic prědělъ (to dělъ , mountain (back), mountain range '): Polish Predeal ; German Predilpass , Pretalsattel (doubled), also in the mountain name Pretulalpe

- Slavic sedlo 'saddle' in most languages up to Russian Gora Sedlo ('mountain saddle') in Kamchatka

- norwegian veg [en] 'way'

- Italian valico 'pass, transition' (to valicare ' to cross, walk')

- slovenian vrh 'mountain'

- Scottish Gaelic bealach : z. B. Bealach na Bà 'Cattle Pass'.

Passes and yokes as weather dividers

Passes and yokes are not only important for road traffic , orography and mountain climbers , but also for meteorology . Because mountain ranges often coincide with weather divisions , so that when crossing the pass - especially on the main Alpine ridge - you can come from sunshine directly into heavy rain or even a snowstorm.

Many such high alpine locations are known to mountaineers; some of them have been given distinctive names such as "Lucke" (e.g. Birnlücke in the Hohe Tauern). In the Dachstein massif there is the “Windlegerscharte” due to turbulent weather changes, and the “ Maloja wind” west of St. Moritz is feared or desired by glider pilots , depending on which side they are crossing the Alps . Another example is the designation wind hole for the Schneeernerscharte on the German-Austrian border.

See also

- Alpine passes in Valais in Roman times

- Erzgebirge passes

- List of Alpine passes

- List of mountain passes in France

- List of Alpine passes in Italy

- List of passports in Austria

- List of passports in Switzerland

- List of mountain passes in Namibia

- List of plateaus and mountain passes in Iceland

- Passports in New Zealand

literature

- Gustav Fochler-Hauke (ed.): General geography. (= Fischer Lexicon. Volume 14). Fischer, Frankfurt 1959, DNB 456624228 .

- Adrian Scheidegger : Systematic Geomorphology . Springer-Verlag, Vienna / New York 1987, ISBN 3-211-82001-9 .

- CURVES. Delius Klasing Verlag.

- Volume 1: Martigny - Nice. Route des Grandes Alpes. 2015, ISBN 978-3-667-10368-0 .

- Volume 2: Borders - Along the Swiss - Italian border. 2016, ISBN 978-3-7688-3859-7

- Volume 3: Northern Italy: Lombardy, Veneto, South Tyrol. 2013, ISBN 978-3-7688-3658-6 .

- Volume 4: Pyrenees. 2014, ISBN 978-3-7688-3783-5 .

- Volume 5: Austria: From Reutte to Trieste. 2014, ISBN 978-3-7688-3918-1 .

- Berthold Steinhilber, Eugen E. Hüsler: Passport Pictures: Landscapes of the Alpine Passes - The illustrated book with photographs of a World Press Photo Award winner about roads, pilgrim paths, tunnels and exciting texts about crossing the Alps. Frederking & Thaler Verlag, 4th edition 2017, ISBN 978-3-95416-120-1 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ cf. about Herbert Louis, Klaus Fischer: General Geomorphology - picture part. (= Textbook of general geography . Volume 1). 4th edition. Verlag Walter de Gruyter, 1979, ISBN 3-11-007103-7 , Fig. 125 Transfluence pass and map terrace in the Radstätter Tauern, Eastern Alps. P. 127 f ( limited preview in Google Book Search) - pictures of typical glacier passes before and after too.

- ^ A b Heinz Pohl: Mountain names in Austria. (Excerpts from the extensive written work of the etymologist) - Entries partly in the text, partly in the examples.

- ^ Heiz Pohl: Mountain names , section Artificial or learned names.

- ↑ Slovenian prekopa , piercing, transition '; after Heiz Pohl: mountain names

- ↑ The same goes for the Mandlingpass , slaw. * Monьnika to * monĭ- / * moń- 'neck, saddle'; after Heiz Pohl: mountain names .

- ↑ Otto Lanser: Pass names in the Alps. (PDF) In: Publications of the Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum. 31, pp. 493-500 (1951).