fur

As fur or incense refers to clothing and accessories processed types of fur and fur of mammals , usually with very densely packed hair . Hides, furs and articles of fur have long been counted among the earliest goods in world trade. Contrary to popular belief, furs played an extremely minor role during the Great Migration, and long-distance trade only emerged after the Carolingian era due to impulses from the Islamic world. The hunt is often carried out by members of indigenous peoples and full-time trappers. The colonial expansion of the European powers in North America, Northern Europe, and Northern Asia was strongly motivated by the fur trade. Production, processing and sales were organized by furriers , guilds, markets and exhibition centers and trading companies. These were privileged by the participating cities and territorial states and supported politically and militarily. Up until the late 17th century there were decrees and dress codes in Europe that permitted certain types of fur only to certain groups of people and classes.

With industrialization, breeding became the main source of the starting product, but fur became increasingly insignificant compared to other groups of goods; that was all the more true of trapping. The trade in the skins of certain animal species , especially those threatened with extinction , has been restricted or prohibited since the 1970s due to the Washington Convention on Endangered Species and other requirements. Many animal rights activists and especially animal rights activists also reject the use of fur.

The most common animals kept for fur production are fox , polecat , mink , raccoon dog (under different names in the trade, often as "Finnraccoon"), nutria and chinchilla . Mink is the most widely kept fur animal in Denmark and fox in Finland.

The fur market has shifted significantly to Asia since the late 20th century . In 2002, the total value of fur produced in the EU was 625 million euros.

Origin of fur

Overview

The origin of the furs can be divided into:

- Hides that are a by-product of livestock and meat production (around 40% of fur production)

- The skins of animals that are hunted independently of the fur production because they act or are perceived as pests or annoyances

- Skins of fur animals hunted for their fur alone, caught or bred to be

When slaughtering livestock, lamb and sheep skins ( Persians , many different breeds of sheep), rabbits ( rabbit fur ), goats and kids , cattle and calves , horses and foals , reindeer (or pijiki) and kangaroo ( wallaby skin ) are produced .

The types of use were subject to considerable historical change. Individual sheep and rabbit breeds are specially bred for their special fur properties. These include, for example, the karakul sheep (curly Persian), the merino sheep (silky, for wool and lamb velours), the chinchilla and rex rabbit . Farm animals such as hamsters, guinea pigs, horses and donkeys or even dogs can in principle be considered as fur suppliers. In some countries and cultures, depending on the food taboo, they were and are also used as meat suppliers. The fur supplier beaver was a popular fasting food in the Middle Ages, opossum and swamp beaver ( nutria fur ) are sometimes still consumed today. Seals are a staple food for the Eskimos .

The wild catch still accounts for around 15% of the global volume. Synonymous here are in particular the furs of animals as pests or vermin are hunted. These include wild rabbits, hamsters , mole fur , New Zealand possum , marten , polecat , weasel , nutria , muskrat and raccoon . Certain types of traps are prohibited in the EU.

In 2008, the majority of the breeding fur animals was attributable to Minknerz , followed by sheep, silver fox , blue fox , raccoon dog ( sea fox fur ), chinchilla , nutria , sable and polecat. Depending on the fashion, more or less successful attempts were made to breed other fur animals (including raccoon, muskrat, skunk ). Most fur skins come from fur farms . For reasons of animal welfare, the breeding of fur animals is prohibited in Austria, Switzerland and Great Britain.

Fur hunting and trading in fur

As early as the 16th and 17th centuries, laws for the protection of various hunting animals were passed in several countries, in which certain closed seasons were set. Since the middle of the 19th century there have been additional efforts to preserve the animal world, which have found their expression in various laws. The 1911 North Pacific Fur Seal Convention for the protection of the northern fur seal and the sea otter was particularly important . In 1973 the Washington Convention on the Protection of Species, internationally known as CITES , was passed, and in 1976 it was ratified by the Federal Republic of Germany. It restricts and regulates the trade in wild animals and plants. Additional restrictions exist through the Federal Species Protection Ordinance , which came into force on January 1, 1987.

Some fur animals such as muskrat and mink have established themselves as neozoa in the European wild and in some cases displace endogenous species such as the European mink . Captive refugees from fur farming and intentional releases are controversial. Protective measures include international trade agreements that restrict the fur trade as well as shooting quotas, protected areas and closed seasons for individual species. The World Wildlife Fund accepts traditional fur hunting under well-defined conditions. This hunting management as well as the management of individual wild fur species is controversial, for example with seal hunting and muskrat control . NABU-Germany accepts the utilization of furs resulting from stock-adjusted fox hunts in Germany. Almost all spotted cats (South American wild cats, ocelots , all big cats ) and otters are no longer legally traded since the Washington Convention on Species Protection came into force in 1973 at the latest . Notwithstanding this, the trade and importation of tobacco products, skins and fur clothing are free and unlimited in the EU.

Fur farming

The keeping of fur animals is researched as an aspect of agriculture, zoology and veterinary science; the scientific accompaniment of hunting and the care of wild animals is a matter of vegetation biology and forestry. Knud Erik Heller from the University of Copenhagen, based on studies of the stress level of fur animals, advocates a hidden retreat for minks in cages, the cage size as such has little influence. The wearing properties such as the ability to keep warm and temperature control with and in furs are of great interest for behavioral research such as the manufacture of appropriate clothing.

In most states, keeping fur animals is covered by general breeding rules such as slaughtering or killing animals. According to Section 4 (1) of the Animal Welfare Act of 1972, vertebrates “may only be killed under anesthesia or otherwise, as far as this is reasonable under the circumstances, only while avoiding pain”. The execution of the killing is made dependent on appropriate knowledge and skills and is followed up within the training of the fur animal owners through recommendations for the animal welfare-friendly killing of fur animals in breeding farms. The Trapping Ordinance applies to wild-caught animals. Cross-border trade is regulated by the international Washington Convention on Endangered Species .

At the European level, with effect from December 31, 2008, it was forbidden to import or export cat and dog fur into or out of the EU countries; Cat skins have been used in particular to relieve rheumatic pain . The reason given for the ban is the lack of acceptance of the use of these emotionally distinguished pets . National regulations come into effect in Switzerland and Great Britain, for example , where there have been no fur animal holdings since the early 1990s. Commercial use is no longer worthwhile, as these wild animals must be kept in an elaborate manner. In Austria , with the regulation on the keeping of fur animals, the keeping of fur animals for commercial purposes has been prohibited since 1998. A European ban failed because of the attitude of the Scandinavians, especially Finland and Denmark, where fur farming is an important regional economic factor.

Labels of origin

Since 2008, the International Fur Trade Federation , an interest group of fur traders, has been organizing the labeling of fur with the “Origin Assured” brand. Such a label is intended to indicate that the goods come from certain animal species and from certain countries in which “regulations or standards” exist for the production of the fur. In the case of the species for which the label is awarded, a distinction is sometimes made between countries of origin and wild and breeding animals, but not between farms or companies. Since 2003 there has also been a label propagated by fur producers, which is supposed to indicate that it is “European” (quote: German fur institute) and indicates the species of animal.

Fur production

quality

The quality of a hide depends on many factors. Particularly dense and hard-wearing fur is found in fur species that live in water either entirely or temporarily. The colder the living space, the thicker and silky the hair, and winter coats are of better quality than summer coats. The skins of small carnivores have a quicker and therefore more stable leather than those of herbivores. The highest fur qualities come from the winter fur of marten-like small carnivores, such as the mink. In skinning, furs have hair densities of over 400 hairs per cm², pelts 50–400 hairs / cm², all hair densities below that are referred to as hairless skin .

Furs are subject to natural aging (temperature, exposure to light, humidity, type of tanning), depending on various external influences. For the beauty and freshness of the material, which visibly diminished over time, there was once the paraphrasing, they “bloom”.

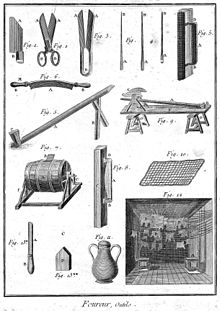

processing

Skinner process smoke or Rauwaren , suitable for the fur processing dressed animal skins. In 2009 there were 825 companies with 6850 employees in Germany. First guild ups are from the 12th and 13th centuries known. Similar to the related professions such as white tanner , bag maker , glove maker and parchment maker , skinning was considered an impure craft in the Middle Ages because of the handling of dead animals, but furriers were respected and mostly advisable.

In Asia, especially in Japan or India, this has resulted in discrimination that continues to this day (cf. Buraku and Dalit ). It is not the products, but the associated professional groups and their relatives and their families that are considered unclean.

In contrast to the tanning , the preparation of raw hides and skins into leather, which are raw skins permanent skins trimmed . For this, the fur is preserved in such a way that the hair is preserved. The trimming tried to replace perishable fats and proteins by preserving and stabilizing substances. Smooth, hard-wearing and processable fur skins are made from dried raw hides. The flesh is fleshed out and the subcutaneous connective tissue is removed, and the fur leather is specially tanned and greased. Finally, the fur skins are stretched, cleaned and smoothed into a shape suitable for further processing. Until around 1850 the furriers dressed their raw hides themselves, after which the dressing was separated from the actual skinning.

Cutting templates for a coat made of fox, silver and leather

In further steps , known as “ fur refinement ”, the skins can u. a. can also be colored, the leather side can be velouted or napped . The skins are refined into so-called "velvet fur" by shearing or plucking. Already in the early modern period a division of labor developed in which pieceworkers and table masters were employed. Later, fur semifinished products maker and furrier added for the finished fur garments. There were hardly any complex changes in the shape of the processed skins before the 18th century. With the invention of the fur sewing machine around 1872 by Joseph Priesner (also with a small motor since 1888), the processing of fur was made much easier and the fur industry expanded considerably. After the end of the training there was often a specialization of the activity in the "cutting edge" and the "sewing kürschner". For sewing with the fur sewing machine there is often another division of labor. This applies in particular to the sewing of the so-called " outlet work ", the lengthening of the skins using cutting systems.

The centers of fur processing include certain regions in Greece and Turkey. In the German-speaking area, fur processing is small, medium-sized and has a very strong regional structure, the remaining fur farms are mainly in Westphalia, Schleswig-Holstein and Lower Saxony. Germany (Federal Republic and GDR) had taken a leading position in the fur finishing industry in the sixties and seventies.

Manufacturing

How many furs are used for a single piece of fur depends on the size of the fur, the type of garment, the fashion and how elaborately the shape is designed. A straight coat 100 cm long in size 38 has an area of around 25,000 cm². Parts of fur that are not used directly, such as tails, paws or head pieces, are put together to form “panels” from which clothing is later made. The main place of "body" or panel production is Kastoria in Greece. The following shows the average usable area of the individual fur types with the fur consumption for a straight coat.

| Technical name | cm² | Piece of skins | comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muskrat | 600 | 46 | Usually dewlap (belly) and back are processed separately. |

|

| chinchilla | 420 | 64 | ||

| Feh | 350 | 80 | Usually dewlap (belly) and back are processed separately. |

|

| European red fox | 2,520 | 10 | ||

| Noble foxes blue fox , silver fox ; not the smaller arctic fox |

3,200 | 8th | By inserting leather strips that are completely or partially covered by the hair (technical terms: galonize, feather ) , the number of fur can be reduced to three or less. |

|

| Rabbit | 700 | 38 | ||

| lynx | 3,150 | 9 | Usually dewlap (belly) and the back are processed separately. |

|

| Mink , "Females" (female skins, females) | 1,000 | 28 | ||

| Mink, "Males" (male skins, males) | 1,350 | 20th | ||

| Nutria | 900 | 30th | ||

| New Zealand opossum | 880 | 32 | ||

| Persians (or Karakul ) | 1,400 | 18th | ||

| sable | 450 | 58 |

remodeling

Furs can be redesigned multiple times. Since the fur was put together from individual skins, it can be reshaped by dividing the skins again. The main motivation for a change is a change in fashion, a change in figure, a change of owner or the removal of signs of wear. During the makeover, the part can be fashionably re-colored at the same time and any color changes that may have occurred can be covered up, the hair structure can be changed by coloring or scissors. Another possibility for change is to transform it into a fur lining , a blanket or a fur plaid . However, the scope for redesign is limited by the natural aging of furs.

Fur accessories

Fur accessories include fur necklaces, muffs , fur gloves , fur stoles and boas as well as fur hats , fur boots and fur bags . Underwear and body warmers , today mainly made of elastic natural fibers such as angora wool, were also made from cat fur until the 1970s. From fur trimmed Outerwear as Schauben and Gollern of official and dignitaries carried developed today Amtstrachten and cladding modes . The heavy chauffeur and driver's coats of the 1920s became a status symbol for college students.

A change between functionality and status or symbolic content also comes into play in the so-called "fur necklaces" with elaborate heads and paws and tails left on the fur. Among other things, they go back to the Zibellini , which was widespread in the Renaissance . The way of wearing was later interpreted as a form of a flea trap and was then, as now, taken up again and again in clothing fashion without reference to flea infestation.

Stoles and boas are part of the evening wear. Its use by prostitutes brought entire types of fur such as the silver fox into disrepute. Wild-caught silver fox pelts were considered the king of furs and a status symbol of the upper class around 1900 . Shortly before World War II, the price sank from the prohibitive £ 500 to 50 to 60 shillings due to the possibility and expansion of breeding. Cheap stoles and fur boas made of silver fox became part of the "street girl uniform" and were taboo for bourgeois women who were self- sufficient .

Economical meaning

Sales and regional focus

The global annual turnover of the entire fur industry was given by the international fur trade association in 2012 at 15.1 billion US dollars, of which 4.5 billion were in the countries of the European Union . He reached a new record high. A total of around 90 million skins are processed each year, of which 28 million are mink skins and 4 million fox skins. According to the German Fur Institute, 46.9% of the fur types used today come from breeding and farming (such as chinchilla, mink, raccoon dog), 37.6% from pasture and stables (such as lamb, goat, calf) and 15, 5% from hunting and keeping (including muskrat, nutria, red fox, raccoon and New Zealand opossum).

Around 6500 fur farms in the EU have around 30,000 employees and around 164,000 in the entire European fur industry. There are regional focuses. Most of the minks are bred in Scandinavia, Italy, the Netherlands and Denmark, China, the USA and Russia. When it comes to making fur clothing, Greece, Italy, Spain and Germany play a leading role in the European Union.

Keeping fur animals and catching them in the wild enable a livelihood or additional income in remote regions with extensive agricultural use and climatic challenges. For indigenous peoples such as Eskimos and Sami , hunting, fishing and animal husbandry, and the associated trade, are still an important source of income. In North America there are around 200,000 trappers and trappers, the majority of whom work part-time. In Canada, about half of the fur hunters are from the First Nations area , fur farming plays a rather minor role due to the lack of a permanent source of food, with a few exceptions, for example at the Wikwemikong on the island of Manitoulin .

In contrast, an essential basis for fur farming in Scandinavia and Holland is the processing of several hundred thousand tons of meat and fish from the food industry as fur feed.

The growing demand for "ecologically" manufactured products has brought marketing strategies to the scene that market furs from "sustainable" hunting for wild animals. The reactions to especially Canadian initiatives such as Fur is Green or the Friendly Fur were rather restrained in Germany according to the motto Can a fur collar be eco . Among the classic environmental protection organizations that tend to be skeptical of hunting, the WWF in particular supports such approaches.

An experienced auctioneer describes the situation on the world market in 2009 as follows: “The fur trade has changed today, it is more influenced by large fur factories than by brokers and furriers. The main market has moved from Europe and North America to China and Russia. ”( Erik Neergard from Copenhagen Fur ) The international fur association IFF puts global retail sales for 2011/12 at US $ 15.6 billion, an increase of 44 percent in the last 10 years. The growth is largely based on Chinese demand of US $ 5.6 billion, tripling over the past 10 years, now outperforming European demand. The retail sales for 2013 are as follows: Asia US $ 5.6 billion (35 percent of total worldwide sales), Europe US $ 4.4 billion (28 percent), Eurasia (Russia, Turkey, Ukraine and Kazakhstan) US $ 4.3 billion (27.5 percent).

Customers and fairs

After 2000, increasing interest in Russia and China had an impact on pan-European fur retailing and the associated trade fairs. In 2009, the MEXA MOSKAU trade fair reported fur sales for Russia at around 2.5 billion US dollars. Almost half of the deliveries came from Turkey and a quarter from China. A considerable number of fur farms have sprung up there since 1990. The rest is divided between Italy, Greece and Germany. In addition to the skins obtained in their own country, Russia obtains the raw material in particular from Scandinavia and Lithuania and has been able to establish its own trade fair with MEXA MOSCOW .

The Hong Kong International Fur & Fashion Fair increased its exhibition area in 2010 from 27,000 m² to 38,000 m² compared to the previous year. The China Fur & Leather Fair in Beijing covered 28,000 m² in the same year, 7.7% more than in the previous year. The Frankfurt fur fair “Fur & Fashion” had shrunk considerably in recent years and was closed after 2008 in favor of “Mifur” in Milan. In Germany, part of the retail sector has changed from a fur shop to a textile supplier.

Status and power symbol

With the formation of the standing armies and the improvement of the production possibilities of the textile factories , military uniforms were widely introduced from the middle of the 17th to the 18th century, with intensive interaction with contemporary civilian fashion.

The uniform of the hussar troops set up in various European countries after the 18th century, which was derived from the Hungarian national costume , included a fur hat ( kalpak ), tight-fitting trousers and the dolman , a tied fur jacket and "overcoats".

The pekesche was a fur-trimmed overcoat of the Polish national costume. During the November uprising of 1830, it was used by the Polish freedom fighters partly out of patriotism, partly out of pragmatism, especially in the cavalry as part of the improvised uniform. After the failure of the uprising, many of them went into exile in Prussia, where the pekesche was adopted as part of the student costume in the wake of the Polish swarming at the time .

The tall, fur-trimmed grenadier caps introduced to French infantry grenadier companies at the end of the 17th century soon made fur caps a common symbol of military elites. This development reached a climax in the Grande Armée Napoleon , although there the use was mostly limited to the parade uniform. Guards and elite companies of the line troops carried the kalpak with light cavalry and artillery on horseback. Even after the final defeat of 1815, France had a style-forming influence even among its enemies: the bearskin hats were adopted by the British Guards Infantry and are still used today for representative and ceremonial occasions. The hats are made from bearskins that come from support programs for the Canadian Inuit.

In the case of the caterpillar helmet , the caterpillar helmet was often only made of fur for officers, while wool was mostly used for the crews.

The Russian ushanka (sometimes colloquially known as “Schapka”, especially in the accession area), a headgear suitable for extremely cold weather conditions, actually comes from Finland. After the winter war of 1939/40 it was adapted as a Russian military cap and distributed internationally beyond the former Warsaw Pact states. It is not only in Germany that this form of the ear flap hat has become the epitome of the Russian hat as “Ushanka”. A picture of US President Gerald Ford with a fur ushanka presented by the hosts during a visit to Russia in 1974 went around the world as a symbol of détente .

Mobutu Sese Seko , from 1965 to 1997 as President Zaires , stylized himself as a “ leopard man ” and wore a cap during public appearances, which symbolized his membership in the corresponding secret societies.

Benedict XVI caused a certain stir . with the use of fashionable accessories and iconic garments such as the Mozetta and the Camauro . The "pure white" of the ermine and weasel winter fur used for this was a symbol of flawlessness since the early Middle Ages, a mark of princely and judicial power and a component and characteristic of coronation robes and various heraldic symbols .

The use of furs and fur parts for decorations and wall hangings can be traced back to the exhibition of hunting trophies, in particular, to craft shows and exhibition objects.

history

In the early Stone Age there were hats and accessories made of fur, as well as fur lining as clothing elements. They were used in conjunction with raffia and wool.

The oldest depiction of a fur is probably a female figure carved from a tusk, around 12,000 BC. The female statuette found in the Siberian Buret wears a jacket, trousers and a hood, the notches on it are interpreted as fur, as a fur costume, as it was still worn there in modern times. Statuettes from the Siberian Malta have painted on them a similar fur clothing.

Probably the oldest surviving fur clothing is the Copper Age bearskin hat and goatskin jacket of the man from Tisenjoch, Ötzi . His shoes had fur soles and deer fur uppers, an inner shoe made of linden wickerwork and an insulation layer made of grass fibers. He wore the fur side of the jacket on the outside, which combined light and dark fur strips. The hat was made of wolf skin. A mesh of grass carried along is interpreted as an overcoat or rain protection. The trousers consist of various pieces of fur from the domestic goat, which are joined together with animal tendons in the simple overcast seam, which is still used in skinning today.

The first records of the trade in tobacco products can be found in China from around 2000 BC. Chr.

Calfskin cloak of the bog body of Kayhausen , ca. 364-350 v. Chr.

Antiquity

In ancient Greece, fur was used to mark military and civil dignitaries, for example in the Iliad. Here, however, the inherent symbolism of the living animal predominated: the Greek military leaders Agamemnon and Nestor were sometimes wrapped in lion skins, Menelaus wore a leopard skin . The simple Trojer Dolon wore a helmet trimmed with otter skin and a wolf fur coat. Less valuable hides from sheep and wild buffalo were used by the warriors as storage facilities.

In Caesar's Gallic War , the Germanic fur clothing is described as a simple wrap that partially exposes the body. Tacitus Annalen tell of a Germanic fur coat called "Reno". Occasionally, simple sheep or wolf skins were trimmed and trimmed with more valuable furs.

Trade development

Contrary to popular belief, the fur trade played an extremely minor role during the Great Migration . During the Carolingian era , furs were in poor esteem and there was no long-distance trade. Therefore, the furs were of regional origin, as the capitularies show. On the other hand, in the 8th and 9th centuries, the first fur fashion can be found in the Muslim area; the material for this was provided by Russian animal populations. Furriers first appeared in the 10th century, initially in southern Italy, Sicily, Catalonia and Castile . Fur luxury was widespread in the 11th century, and from the 12th century furriers were given a higher rank in urban societies. Towards the end of the 13th century, followers of great men were given a fur-trimmed official costume for Easter and Christmas. From the middle of the 14th century, luxury regulations ensured that certain furs were reserved for the nobility. They were not allowed to be worn by non-nobles. At the end of the 14th century the marten gained respect for Feh , in the 15th century ermine, white weasel and white lamb were at the top of women's fashion.

In the emerging early capitalism , the fur trade played a certain role for the first international companies and trading companies. Central trading locations were Novgorod and the Baltic Hanseatic cities, which brought their goods to London and Venice. In the Hanseatic League , wild animal skins from Russia and sheep and goat tobacco products from Britain and Scandinavia were negotiated throughout the Baltic Sea area. Around 1400 more than a million false skins per year should have taken this route. Conversely, it was almost the only way to acquire the coveted cloths from Western and Southern Europe. The export of lambskins was even more extensive. Heinrich Veckinchusen negotiated around 2 million raw furs between 1402 and 1411 alone. The German order sent at the end of the 14th century, nearly 100,000 pelts of Bruges , which he Venetians and Süddeutsche trailing in his wake. Many furs went from Bruges to Venice, from there hundreds of thousands of furs went to Alexandria . Jean de Trois Moulins , a particularly wealthy furrier, was one of the largest taxpayers in Paris . Barely more than ten furriers dominated the luxury market there. Jacques Coeur , the financier of the French crown, was the son of a furrier from Bourges . In the 15th century, the decline of medium fur qualities began, while the higher ones remained in demand.

The Russian colonization and conquest of Siberia , which was strongly motivated by the search for new stocks of fur animals, were based on extensive trade privileges and rights. Ivan the Terrible had given them to the Stroganov family of Russian merchants in 1558 . Alaska was opened up for the fur trade in Russian America due to a monopoly granted to the Russian-American Company by Tsar Paul I in 1799 .

In 1671, the Hudson's Bay Company held the world's first tobacco products fair at the Garlick Hill fur trading center in London. The center of the German fur trade and for a time a large part of world trade was the Brühl in Leipzig for many decades . Many tools and later production machines were obtained internationally from Germany. In particular, Russian and later American tobacco retailers contributed to Leipzig's international role as a trade fair city. The share of the industry in the tax revenue of what was then the "fur and trade fair city of Leipzig" was still 40% in 1913.

The fur trade in North America was closely linked to the demand in the European purchase markets. From the 17th century, starting in Sweden, felt hats made from beaver hair became fashionable in Europe . Its undercoat could be felted well, and beavers were not subject to the classic dress code and the high-quality hats were therefore allowed to be worn by the nobility and bourgeoisie. The hair was made into felt in a complicated, harmful process. The corresponding demand for beaver pelts was also met from North America. From the end of the 18th to the middle of the 19th century, the castor hat (lat. Castor for beaver ) was in vogue as a bourgeois symbol and forerunner of the cylinder and intensified the demand for fur.

The beaver fur trade associated with the beaver felt hats was an important driver of the development of North America. The English Hudson's Bay Company was founded in 1669 under the motto Pro Pelle Cutem specifically for the fur trade in North America , which until then had been dominated by the French. At the beginning of the 19th century there was a further intensification of the North American fur trade. The short-lived Rocky Mountain Fur Company and the American Fur Company founded by Johann Jakob Astor opened up previously remote hunting areas with so-called rendezvous (central annual exchange fairs in the Rocky Mountains) and thus achieved significantly higher profits than the traditional trading companies. The beaver populations were reduced in a short time.

Dress codes: class restrictions and gender assignments

Dress codes, from the Middle Ages to the early modern period, restricted the use of certain types of fur to the upper classes. In 1530, the Augsburg Reichstag granted peasants only unbranded, simple fur from sheep, lambs and goats . Almost every monarch after 1363 on the English throne up to and including Charles II created an “Act of Apparel”, a piece of legislation on class-specific restrictions on clothing, drinks and food. Rare and sought-after skins were reserved for the nobility and dignitaries in accordance with precisely coordinated dress codes. This concerned in particular the ermine (see ermine fur in heraldry ), sable and feud . Elements of this have been preserved in the dress code and official costumes of the British monarchy to this day.

In England, efforts were made, among other things, to make corresponding status indicators uniformly and sufficiently available for the various strata, to obtain all of them from domestic sources as far as possible and to put aside individual customs that were perceived as exaggerated. The first such regulation limited imported pelts to the royal family. A request by the Puritans in England from 1650 after the execution of Charles I, which would have severely restricted the dress code for women, was repealed, in particular due to female resistance.

In the German cities, the regional expenditure and luxury laws of the late Middle Ages were regularly adapted and renewed for the more variable use of noble cloth qualities such as velvet , silk and brocade fabrics . The cultural scientist Julia Emberley states that fur in modern times has increasingly specifically feminine connotations. The restrictions that were openly justified in the Middle Ages were therefore postponed with the increasing influence of the bourgeoisie and the Puritans on religious and ethical issues and were a direct expression of the roles and freedom granted to women. For a long time, prostitutes were banned from wearing fur. Emberley also puts the modern, organized antagonism against fur in such a context.

In 1809, in an extremely harsh winter, the first modern men's fur appeared on the streets. Because of the unusual nature of the garment, the male fur wearers were still exposed to harassment. The appearance of the fur boa around the 1820s, with the appearance of necklines, was also due to the cold. When the fashion of deep necklines ended twenty years later, the breast-warming boa also largely disappeared.

industrialization

From 1830 silk ousted top hats the beaver. New technical possibilities for fur and textile processing emerged, and renewed upheavals in the fur industry were the result. The most important of these was the invention of the fur sewing machine by Joseph Priesner around 1872, it made it possible to produce furs much more cheaply and to leave them out. Skipping means cutting the fur into small strips. These are barely visible with fine seams to form a longer, narrower strip of fur the length of the garment. The fur was now worn mainly with the hair side out. The result was fur clothing that was affordable for the bourgeoisie, and especially for bourgeois women, which quickly became popular.

German fur manufacture began in 1855, when N. Wolff offered ready-made fur for the first time in stages via Berlin, Hamburg and Holstein. He was soon followed by other fur traders who also became manufacturers. Increasingly, the furrier shops no longer only sold self-made goods and the percentage of fur in textile shops increased rapidly. By 1885 fur refinement was so advanced that longer pieces of clothing could also be made. The first Persian paletot appeared in Paris. Long coats in various types of fur were already being offered in large numbers at the Leipzig Fair in 1893.

Around 1900, fur fashion was still completely dominated by fur trimmings in addition to fur linings . Fur necklaces with elaborated heads showed an excess of shapes. Fur collars and muffs, initially mostly made of Persian , soon made of various types of fur. Among other things, ermine , opossum , suzliki , slinks and grebes found great sales. Traveling wholesalers brought them to all parts of Germany and Europe.

The actual year of birth of fur in today's style is considered to be 1900. Fur fashion turned to haute couture and at the world exhibition in Paris , parts made entirely of fur, in modern processing with the hair facing out, were shown to a greater extent. A fur coat caused a sensation, in which the hundreds of meters long outlet seams were still sewn by hand despite the already invented fur sewing machine. The working time for the journeyman was 240 hours, for the seamstresses 1400 hours. The fur sewing machine had already been invented, but still caught so much leather in the seams that it could only be used for rough work.

In the big cities of the western world, fur clothing grew rapidly with a large number of employees and subcontractors, the intermediate masters. Around 10,000 users , (fur) tailors, fur sewers , stretchers, finishers and ironers demonstrated during a strike in New York in 1938 for better working conditions. At that time there were almost 500 self-employed furriers or intermediate masters in Berlin's fur district.

From the beginning of the 20th century to the end of the 1970s, Persians became increasingly popular as large-scale clothing (jackets and coats) due to the establishment of breeding in what was then South West Africa, now Namibia . At the same time, early animal protection protests were loud, because the fur is obtained from Karakul sheep up to three days old .

time of the nationalsocialism

From 1933 to 1939, the foreign exchange necessary for the purchase of furs abroad was generally still granted within the framework of the law on the movement of goods with foreign countries of 1934. The fur procurement was still possible mainly through the smoking center in London. From the end of 1941, the Germans were encouraged to donate furs and skins in view of the lack of clothing suitable for winter during the Russian campaign . Many furriers were busy converting civilian furs into inner lining.

Wearing fur or fur-trimmed clothing was banned from Jews in German-occupied Poland from 1941 and in Germany from 1942, and appropriate clothing was removed from expellees and deportees. The poet Bertolt Brecht thematized the common enrichment of ordinary people (the “little furry collar” from Oslo) in the song of the Nazi soldier's wife . The historian Götz Aly later worked this out on the thesis of redistribution and broad participation in Hitler's people's state .

A similar mentality prevailed in the leading circles of the NSDAP. They combined with conflicts within the hierarchy about the image of women and the clothes that go with them. The propagated ideal of the German mother from the country, who did not need cosmetics, was opposed to women in leading positions, such as Magda Goebbels , who took the opportunity and took furs and jewelry from the persecuted.

Anti-Semitism and the fur trade

The German fashion industry before 1933, in particular fur trade and clothing, was based to a large extent on Jewish businesses. These became the target of anti-Semitic campaigns and writings early on, for example in the USA with Henry Ford .

In the center of the German fur trade, i.e. in Leipzig, in 1929 more than half of 794 tobacco shops were of Jewish origin. Among other things, the Leipzig writer and trained furrier Edgar Hilsenrath came from such a family.

In 1933, after the seizure of power , an official announcement appeared in the magazine “Der Rauchwarenmarkt” in May that Jewish companies had no reason to fear interference in the tobacco industry. However, the Association of German-Aryan Manufacturers of the Clothing Industry eV (ADEFA) already advertised the products of its affiliated companies in the same year: "Guaranteed Aryan". By 1936, 113 Jewish companies had emigrated from Leipzig alone.

Most had fled to the United States or the second major European fur center, London , from persecution . This has contributed to the relocation of the international center of the fur trade from Leipzig to London. Most of the companies were liquidated or " Aryanized ". Few Jewish traders, insofar as they had survived the Holocaust , returned.

Development of the fur industry after 1945

After the Second World War, the name Brühl was transferred from Leipzig to Niddastraße in Frankfurt in the fur industry . Around 80% of the total tobacco trade in Leipzig that remained after the war and the persecution of the Jews was relocated to the western zones . The German Fur Institute (DPI) as the interest group of the German fur industry also has its office in Frankfurt. The fashion of the immediate post-war period consisted mostly of remanufactured old clothing. Old furs that had escaped the "collection of wool, fur and winter items for the front" and other luxury goods were exchanged for food on the black market .

The 1st International Fur and Leather Fair in Basel in 1947 was the first of its kind after the war. From 1949 furs were presented and traded again at the newly founded tobacco goods fair in Frankfurt. Instead of heavy dust coats , lighter fur clothing appeared. So-called “ summer furs ” were created, and a lot was again occupied and trimmed. With the economic miracle, the " Persian " came into fashion. The department stores now offered cheaper versions of Persian claws and Persian pieces.

In 1947 and 1948, the fur market in the USA and Canada collapsed for the first time. Vigorous price fluctuations made it difficult to survive as a trapper, and Indian policy in the United States and Canada deprived the indigenous peoples of more and more opportunities to hunt, except for their own use. The same was true of the Soviet Union, which, like the American competition, increasingly relied on breeding farms. With the end of the Persian wave in Germany in the 1970s, there was also a reorientation towards American breeding mink. Income in western Germany rose. With the mass production by fur farms and the associated drop in prices, mink fur became more and more affordable. Persian coats and mink stoles became symbols of wealth and status. Compared to the easy-to-breed fur species, other fur animals increasingly lost their importance. The previous variety of materials disappeared. The fur fashion of the 1950s and 1960s, which was reduced to a few types of fur animals such as mink, nutria and fox, lost its appeal, and the cheaper production of what was now largely industrialized production made hunting largely insignificant.

For the population of the GDR it was said in 1967 in a specialist publication of the fur industry: "" Furs mean hierarchy. For the citizens of the GDR there is no longer any social basis to express differentiated personal and social positions through fur clothing ”. In the next paragraph, this statement was not only relativized, but actually canceled again: “Wearing beautiful, functional and fashionable fur clothing that protects against the cold and meets the need for jewelry is part of the lifestyle of socialist people. The type of clothing and its design should express the social position, the material and cultural wealth, the self-confidence and the optimism of the people ”. The extent to which the need for fur clothing was satisfied in the GDR was “not so much dependent on the amount of the purchase fund as more on the size of the goods on offer”.

Leipzig regained a certain international importance as a fur center through its auctions, which began in 1960 and not only from the GDR , especially from Russia, were auctioned. The furrier trade, which was particularly abundant around Leipzig, was also used to acquire foreign currency . Quote: "The provision of funds for the import of raw hides requires the participation of the tobacco industry in the export in order to contribute to the generation of the equivalent". Essentially only companies from the “capitalist countries” appeared at the Leipzig tobacco auctions, in particular from West Germany, the USA, Great Britain, Italy and Switzerland. The mink skins were sold exclusively at these auctions, with the exception of small quantities that were incurred between the auctions. For the west, especially the mail order business and department store chains, what the local market demanded was produced. The needs of the GDR population were preferably met with local furs, especially rabbit and sheepskin .

In the late 1960s and 1970s, critical voices against fur farming, fur fishing and the wearing of fur increased. The focus was initially on the hunt, especially on marine mammals, later the breeding conditions followed. A campaign against the nature and circumstances of the seal hunt in Newfoundland , represented in the mass media by the actress Brigitte Bardot and other celebrities such as Linda McCartney , resulted in an extensive discrediting of fur fashion. Fur-trimmed clothing and, in particular , official costumes trimmed with Persian fur went out of fashion because they were considered symbols of an outdated social order.

Anti-fur campaigns and slump in fur sales in the late 1980s

The writer Marguerite Yourcenar wrote a letter to Brigitte Bardot in 1968 . So she won the French actress for an engagement against the seal hunt in Canada. Bardot himself had posed naked in an American manufacturer's mink coats for an advertising campaign in 1969. Bardot denounced the extent and methods of the seal hunt and, among other things, burned furs at a demonstration in Paris.

Aqqaluk Lynge , President of the Inuit Circumpolar Council , made the campaign against the Newfoundland seal hunt indirectly responsible for the social problems of the Eskimos living further north in the Arctic in the early 1980s . For them, the seal hunt and the fur trade were an important economic basis and a way of life that was deeply anchored in their culture. This was largely destroyed by the general ban on importing sealskin into the European Union . In 2006, the European Parliament asked the Commission to adopt a regulation banning the import, export and sale of all harp and hooded seal products. An expert opinion was issued in 2007. In 2005, clothing made from seal skins totaling 460 tons and a value of around 68.2 million euros was imported into the Federal Republic of Germany. The separation offered by the EU between traditional fishing by indigenous peoples and commercial fishing was rejected by Canada.

The cultural and literary scholar Julia Emberley sees various campaigns as attempts to intimidate women in their self-confidence and to restrict their right to freely carry their property. Anyone who, from the fur opponents' perspective, wore fur against their better judgment had to be cruel and cold like the Cruella from Hundred and One Dalmatians . Linda McCartney created a poster in 1984 for the English anti-fur organization Lynx that plays with the ambiguity of the word bitch . A lasciviously depicted white fur wearer, a “rich bitch” (rich slut) is contrasted with a dead, bleeding “poor bitch” (a poor bitch).

Fur coats and stoles were now seen as out of date by a higher proportion of consumers. The foxtail on vehicles mocked as a farmer's Porsche was increasingly perceived as an embarrassing and provincial accessory. At the beginning of 1984 the fur turnover steadily decreased. While in 1980 sales of 3.8 billion DM were made in West Germany, in 1991 it was only 1.7 billion, in 2005 only 0.96.

Julia V. Emberley formulated a criticism of the anti-fur opponents from a feminist point of view as early as the late 1990s. The activities and arguments of the anti-fur opponents simply ran out of steam after some successes. Initially, the actual, sometimes brutal, economic effects of the fur boycotts on indigenous people were basically ignored. The anthropologist Hugh Brody spoke of a new form of imperialism . According to Emberley, slogans such as "It takes forty stupid animals to make a mink coat, but only one to wear it" were particularly applicable to white bourgeois shoppers. The actual increasingly multicultural orientation and composition of fur consumers would have been deliberately and systematically suppressed. After some time, this misogynous argument would have turned against the animal rights activists. The moral claim was felt to be self-righteous and arrogant. On the other hand, it would also have been reinterpreted in the sense of self-determination, in the feminist sense under the motto "I am worth the fact that animals die for me".

Relocation of fur consumption to Asia after 1995

This trend has been reversed since the mid-1990s , despite ongoing protests from animal rights organizations such as PETA . Regardless of this, the fur opponents still had considerable resources at their disposal. The International Fund for Animal Welfare spent over $ 3 million in 1997 on actions against the North American fur trade. In Germany, the fur industry is growing again after a significant slump. There is increasing demand for plucked or sheared furs, which were already popular in pre- and post-war fashion. While the most popular fur types back then were Seal , Sealkanin , Sealbisam , beaver, nutria and other furs refined on Seal, it is now for the first time "velvet" mink and velvet weasel and again velvet nutri and velvet bisam. Unusually combined and colored furs are increasingly being offered.

Fur and especially fur accessories have been playing an increasing role in fashion again since the late 1990s. In New Burlesque , fur and fur accessories are worn again , also with reference to the revues in the early 20th century (cf. Vaudeville ). At the same time, the image of women also changed, Riot Grrrls occupied the image of the bitch again in a positive sense.

After the turnaround in 1989, the fur industry in the GDR expected an upswing similar to that after the currency reform in the Federal Republic of Germany, and tobacco merchants reopened branches in the traditional fur city of Leipzig. The hoped-for boom did not materialize, however, the population turned to other consumer products or made up for long-missed trips to western countries. On the contrary, the packages with the discarded furs of the relatives in the west did not materialize. There was nothing more to redesign and adapt and the previously significant number of GDR furriers was reduced considerably, the branches were closed again after a few years. The situation is different in the economically liberalized Eastern Bloc, especially Russia, China and South Korea consume most of the world's fur production today. The main market, especially for processing the skins, is still in China. For the first time in the history of the Copenhagen Fur auction house of the Danish breeders' association, three of the most expensive lots were auctioned at the same time from a single supplier in September 2017, headquartered in Beijing.

Record prices were achieved at fur auctions in 2006, a price development that was stopped for the first time in 2014. Fur fashion is increasingly characterized by lighter fur products which, according to the fur designers , can be worn all year round, as well as the mix of materials with textiles. By offering small parts and as trimmings on textiles, fur became increasingly affordable for smaller incomes. With this, fur has moved very far away from the clearly luxury product and has become part of the general fashion market.

Fur as a theme of the animal welfare and animal rights movement

There are pronounced aversions and sometimes violent opposition to the wearing and production of fur. Among other things, it is criticized that the use and keeping of animals for fur production serve fashion and luxury alone and take place under conditions that are cruel to animals .

A temporary member of the Animal Liberation Front in the Netherlands committed the murder of the politician and fur lover Pim Fortuyn in 2002 , which heightened fears about increasing terrorist activities in the area.

On the part of many animal rights activists , the keeping and slaughter of animals and the trapping of animals in animal traps for fur production are generally rejected, as is the circumstances with individual types of fur. So that is livestock in some fur farms as not appropriate to the species or animal cruelty considered. The predators kept there would be kept in cages that are far too small under hygienically unreasonable conditions and would therefore develop behavioral disorders and suffer physical damage. The keeping of fur animals in Germany is based on the "Expert opinion on animal-friendly keeping and killing of fur animals" from 1986 and recommendations of the Council of Europe from 1999. This recommendation from 1999 has already found its way into national law and is included in the Code of Practice of the European Fur Farmers Association ( EFBA). In contrast, a study published in 2001 by the Scientific Committee on Animal Health and Animal Welfare of the EU compiled information on keeping eight common fur species. The high mortality rate in young animals and behavioral problems in female mink were particularly criticized. The breeding goals are not so much tameness or adaptation to captivity, but especially the quality of the fur. In addition to the further training of the keepers, it was recommended that the breeding goals be more focused on reducing anxiety and aggression as well as more focus on the animals' natural play and exploration behavior.

A uniform European regulation has not yet come about. Stricter requirements from some EU countries could not be generally enforced either across the EU or abroad. In 2005, the German Animal Welfare and Farm Animal Husbandry Ordinance was adapted accordingly, with the aim of gradually improving the keeping conditions for fur animals in Germany.

Fundamental criticism of the term "use" of animals comes from the environment of the animal rights movement . According to Tom Regan, it emphasizes an autonomy or the right to comparable interests of higher animals, including humans. Animal rights demands generally go far beyond animal welfare. The use of fur in particular is criticized for the fact that the killing of the animals serves to satisfy a human need for luxury items that is unjustified according to Helmut F. Kaplan .

Actions by animal rights organizations such as PETA became known . Anti-fur militants such as the Animal Liberation Front carried out illegal actions. This includes stalking and harassment, the throwing of cakes and color attacks on fur wearers and fur clothing, destruction of fur clothing, attacks on department store branches and burglary or arson in fur farms and the release of animals kept there . In the case of the Cloppenburgs , a family in the fur business was desecrated. There was also controversy in connection with the Wiener Neustädter animal welfare process in 2011.

Perception and interpretation

As a rule, every clothing that a person wears is motivated in several ways. A piece of clothing should protect, but at the same time look beautiful and highlight the wearer. It is often simply not possible to decide which of the reasons should be rated more strongly. Noble furs are one of those goods that go beyond what is necessary and are particularly in demand because of their rarity or their higher production costs. For wild-caught pelts, it can be said that products from abroad were almost always valued more highly than local products.

Leather is often associated with savagery and unrestrained behavior. Fur, on the other hand, expresses and shows intimacy. Both literarily and in psychology, the special role is thematized, among other things, by Venus in Pelz , a novella by Leopold von Sacher-Masoch , a classic of erotic literature , published in 1870 . The image of a woman wrapped only in furs is the leitmotif of the hero of the novel and was inspired by a depiction of Venus by Titian . The biographical novel Frau im Pelz describes a wide variety of images and roles of women under National Socialism, again under the leitmotif of the fur coat. The model was the Swiss journalist, Gestapo agent and block elder in the Ravensbrück concentration camp Carmen Mory . In the Freudian interpretation, fur stands for the (hairy) pubic area.

In modern art, Meret Oppenheim's Le Déjeuner en Fourrure (Breakfast in Fur, a Fur-Covered Coffee Cup) from 1936 is a major work of Surrealism . The iconic work of object art thematizes and alienates everyday perceptions such as the sensual effect of fur. Oppenheimer had previously decorated bracelets with fur and, at the suggestion of a friend, included the coffee cup. She became famous with the object.

Beyond the pure clothing purpose, certain furs and fur accessories have served as symbols of power and status up to and including sexual fetish since ancient times .

They play an important role in legends about shape and coat changers , in carnival costumes , in literature and in subcultures (see Furry ). The symbolic role was often more important than the practical utility, for example as protection against the cold. In contrast to many Native Americans, European immigrants preferred to wear furs with the less warming but more attractive fur side on the outside.

The research examined the emergence and role of fashions, but also the meaning of gender roles, colonial projections and introjections, the numerous roles of ethnic groups, as well as the economic meaning or those at the drawing level. The symbolic and iconographic role is a topic of fashion and art history as well as of ethnology and folklore as well as historical studies.

literature

Craftsmanship

- Heinrich Schirmer: The technique of skinning. The standard work of fur processing. Verlag Arthur Heber u. Co., Leipzig 1928.

- Kurt Nestler: Tobacco and fur trade . Dr. Max Jänecke Verlagbuchhandlung, Leipzig 1929.

- Friedrich Malm and August Dietzsch: The art of the furrier. A manual of professional knowledge and technical ability. Fachbuchverlag, Leipzig 1951.

- Bruno Wallmeyer: Fur-bearing animals . Fur-Bearing Animals. Handbook for the tobacco industry, Georg Kurt Schauer , Frankfurt 1951.

- Vocational training committee of the central association of the furrier trade (ed.): Der Kürschner. Technical and textbook for the furrier trade . Bachen, Cologne 1953.

- Collective of authors: tobacco product manufacture and fur clothing . Fachbuchverlag, Leipzig 1970.

- Christian Franke, Johanna Kroll: Jury Fränkel's Rauchwarenhandbuch 1988/89 . Rifra-Verlag, Murrhardt 1988.

- Helmut Lang : fur. From simple fur to high-quality clothing. 1992, ISBN 3-87150-314-2 .

history

- Emil Brass , From the Realm of Furs . Volume 1: History of the tobacco trade. Volume 2: Natural history of fur animals. (In 1 volume), with numerous illustrations and tables, Bln., Verlag der Pelzwaren-Zeitung, 1911.

- Ruth Turner Wilcox: The mode in furs; the history of furred costume of the world from the earliest times to the present . New York 1951.

- Alexander Tuma: The History of Skinning . Publisher Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1967.

- Elizabeth Ewing: Fur in dress . London 1981.

- Walter Fellmann : The Leipziger Brühl . Fachbuchverlag, Leipzig 1989, ISBN 3-343-00506-1 .

- Julia Emberley: The Cultural Politics of Fur . Montréal et Kingston, McCill et Queen's University Press, 1998.

Critical

- Karin Hutter u. Günther Peter: Pelz makes you cold, On the sell-out of wild fur animals , Echo Göttingen, 1989, ISBN 3-926914-02-5 .

- Henk Lambertz, Horst Güntheroth, Rainer Köthe: The penitentiary of animals. About life and death in fur farms , 1983 Verlag Gruner and Jahr AG & Co.

- Edmund Haferbeck: Fur farming. The pointless dying. Current questions - factual answers. , 1990 Echo Verlag.

- tier-im-fokus.ch (TIF): Fur animals , info dossier, 2009.

Web links

- Ann M. Carlos (University of Colorado), Frank D. Lewis (Queen's University): The Economic History of the Fur Trade: 1670 to 1870 ( Memento of January 13, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- German fur institute

- Swiss fur trade association

- Implementation of the Fur Declaration Ordinance - Information page of the Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office in Switzerland

- Austrian Chamber of Commerce: Federation of Furriers

- International Fur Trade Federation

- Fur criticism of the German Animal Welfare Association ( Memento from October 12, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- Zurich animal welfare site against fur clothing

- Fur criticism at the association against animal factories (Austria)

- Modetheorie.de Extensive bibliography and portal on fashion theory with a large number of original texts on fashion such as fur

Individual evidence

- ↑ Richard Hennig : The European fur trade in the older periods of history , in: Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte 23 (1930) 1-25 and Bruno Schier : ways and forms of the oldest fur trade in Europe , Frankfurt 1951. Table of contents .

- ↑ The Socio-Economic Impact of International Fur Farming , p. 1 (PDF) ( Memento of March 11, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Origin and production of fur ( memento of the original from March 25, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Gloss on dealing with the subject in Hairy Morals ( Memento from June 7, 2008 in the Internet Archive ), Die Welt from October 15, 2003, by Dirk Maxeiner and Michael Miersch.

- ^ Christian Franke / Johanna Kroll: Jury Fränkel's Rauchwaren-Handbuch 1988/89 , 10th revised and supplemented new edition, Rifra-Verlag Murrhardt.

- ↑ a b c d Fashion & Beauty Fashion Trends Can you wear fur today? ( Memento of December 10, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Anne Petersen, BRIGITTE 01/2006, December 20, 2005.

- ↑ a b Can a fur collar be eco? World online . February 14, 2008.

- ↑ Mogens Bildsøe, Knud Erik Heller, Leif Lau Jeppesen Effects of immobility stress and food restriction on stereotypies in low and high stereotyping female ranch mink Behavioral Processes, Volume 25, Issue 2-3, December 1991, pp. 179-189, doi: 10.1016 / 0376-6357 (91) 90020-Z

- ↑ thermal properties of Furht Hammel - American Journal of Physiology, 1955 - On Physiological Society.

- ↑ EU MEMO / 06/436, Brussels, November 20, 2006, Questions and Answers on the proposal to ban cat and dog fur in the EU

- ↑ a b c Research Paper 01/15 ( Memento of December 31, 2006 in the Internet Archive ), October 19, 2001, Fur Farming (Prohibition) (Scotland) Bill, summary of the Scottish Parliament on fur farming in Europe.

- ↑ http://www.ffs.fi/wps/wcm/resources/file/eb57e644c00ee84/WEB_FFS_SKTL_ENG.pdf GenealogieToter Link | url = http: //www.ffs.fi/wps/wcm/resources/file/eb57e644c00ee84 /WEB_FFS_SKTL_ENG.pdf | date = 2018-12 | archivebot = 2018-12-01 22:12:21 InternetArchiveBot}} (Link not available) Fur Farming in Finland - a countryside success story, image brochure of the Finnish Fur Breeders' Association (FFBA ).

- ↑ Approved OA ™ Fur Production. IFTF, archived from the original on June 7, 2009 ; Retrieved June 30, 2013 .

- ↑ European name label of fur associations strengthens consumer position. (No longer available online.) German Pelz Institute, archived from the original on May 6, 2014 ; Retrieved June 30, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Heinrich Dathe, Berlin; Paul Schöps, Leipzig with the assistance of 11 specialist scientists: Pelztieratlas , VEB Gustav Fischer Verlag Jena, 1986, p. 17.

- ^ Heinrich Lange, Albert Regge: History of the dressers, furriers and cap makers in Germany . German Clothing Workers' Association (ed.), Berlin 1930, p. 82.

- ↑ Summary of the processing steps on the website of the German Furrier Guilds ( Memento from May 30, 2000 in the Internet Archive ), accessed in March 2009.

- ↑ draft Guliya Baykieva.

- ↑ Without mentioning the author: The production process in the Kürschnergewerbe , Kürschner Zeitung, No. 28, Verlag Alexander Duncker, Leipzig, October 1, 1933, pp. 598–600.

- ^ A b c d Walter Fellmann: Der Leipziger Brühl , 1989, VEB Fachbuchverlag, Leipzig.

- ↑ Paul Larisch , Josef Schmid: The furrier craft . Self-published, Paris without year (first edition, part I 1903), p. 32.

- ↑ a b Lena Fleuchaus: The fur industry is slowly warming up . Haut (e) Couture The fur trade in Germany is recovering despite some resistance , in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, December 7, 2006.

- ^ A b Philipp Zitzlsperger: Dürer's fur and the right in the picture - clothing science as a method of art history , Akademie Verlag GmbH, 2008, ISBN 3-05-004522-1 .

- ^ A b Francis Weiss : Up and down . In: Winckelmann Pelzmarkt , Winckelmann Verlag KG, Frankfurt / Main, issue 317, January 2, 1976, p. 1.

- ↑ IFTF - International Fur Trade Federation, Press Releases: "Global fur trade now worth $ 15 billion US ($ 4.5bn EU, $ 10.6 non EU)" ( Memento of the original from April 15, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Since October 2013 IFF - International Fur Association. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

- ↑ a b c d Back in Style : The Fur Trade , Kate Gailbreath, December 24, 2006 in The New York Times .

- ^ The Socio-Economic Impact of International Fur Farming ( Memento of February 17, 2004 in the Internet Archive ). Brochure of the International Fur Trade Organization (IFTF) on the international fur industry, as of September 2003.

- ↑ Claudia Notzke: Aboriginal Peoples and Natural Resources Canada . Captus Press, 1994.

- ↑ International Fur Trade Federation, Importance of the European Fur Industry ( Memento of October 15, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 458 kB).

- ↑ Fur is Green campaign in Canada under Nothing to fear but fur itself , Nathalie Atkinson, National Post , October 31, 2008.

- ↑ Bolette Frydendal Jeppesen: The Last Hammer Stroke , in “Kopenhagen Fur News”, September 2009, p. 8 (English) ISSN 1901-7316

- ↑ Without the author's details: Worldwide fur sales are stronger than ever with growing demand . In: Pelzmarkt June 1913. Deutscher Pelzverband e. V., Frankfurt am Main, p. 2. Primary source: IFTF International Fur Trade Association.

- ↑ a b c d BFAI short study of fur clothing in Russia “en vogue” Date: June 2, 2006 Imports continue to dominate the market / trade fair “Mecha” again with a joint German booth → http://www.bfai.de/fdb GenealogieToter Link | url = http: //www.bfai.de/fdb | date = 2018-12 | archivebot = 2018-12-01 22:12:21 InternetArchiveBot}} (link not available).

- ^ Pelzmarkt , Deutscher Pelzverband e. V., April 2010, p. 2.

- ↑ Copenhagen Fur News , Kopenhagen Fur, April 2010, p. 8.

- ↑ Animal rights activists of the Guard at Fell . By Johannes Leithäuser. In FAZ. September 2, 2008.

- ^ Stern September 9, 2006, Benedict XVI. The Pope's new clothes , by Claudia Pientka.

- ↑ Josef Winiger: The clothing of the ice cream man and more recent findings at the beginning of weaving north of the Alps. In The Man in the Ice: New Finds and Results / K. Spindler… [et al.] (Eds.), By Konrad Spindler, Frank Höpfel, Werner Platzer, contributors Konrad Spindler, Frank Höpfel Springer, 1995, ISBN 3-211 -82626-2 , p. 119 ff.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The oldest known fur clothing . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Vol. XVII / New Series 1966 No. 2, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin a. a., p. 71 (Note: According to the article there was a press release at the time, according to which an excavation from the same epoch in northern Russia shows the fur clothing even better.)

- ↑ Der Fellmantel , website of the South Tyrolean Archaeological Museum, as of 2008.

- ↑ Goedecker-Ciolek, R .: Chapter on the production technology of clothing and equipment. In: Markus Egg , Konrad Spindler : The glacier mummy from the end of the Stone Age from the Ötztal Alps. In: Yearbook of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum 39/2, 1992, pp. 101-106.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan, Bochum: On the history of the tobacco trade in antiquity and the Middle Ages and the development of the Russian-Asian region from 16.-18. Century. Inaugural dissertation to obtain the doctoral degree, University of Cologne, 1940, p. 5. Table of contents . Primary source E. Speck: Handelsgeschichte des Altertums , Leipzig 1900, 2 volumes, volume I, p. 117.

- ↑ a b Vocational training committee of the Central Association of the Furrier Handicraft (ed.): Der Kürschner , JP Bachem publishing house in Cologne, 1953.

- ↑ ditto in song 10.

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and rough goods . XXI. Tape. Verlag Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1950. p. 35.

- ↑ Essentially based on: Lexikon des Mittelalters , Art. Pelze , Vol. VI, Sp. 1866–1868.

- ↑ JF Crean, Hats and the Fur Trade in: The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science , Vol. 28, No. 3 (Aug 1962), pp. 373-386, p. 379.

- ↑ Dietmar Kuegler, Freedom in the wilderness - Trappers, Mountain Men, fur traders - The American fur trade , Publishing House for American Studies , Wyk 1989, ISBN 3-924696-33-0 . (Methods, personalities and companies in the fur trade).

- ↑ A possible reference is Job 2: 4, where the devil is quoted as “skin for skin; and everything a man has he leaves for his life ”, another interpretation is“ fur for fur ”or simply“ for fur we risk our skin ”.

- ^ Shepard Krech: The Ecological Indian: Myth and History. Publisher: W Norton & Co Ltd; October 21, 1999, ISBN 0-393-04755-5 .

- ^ A b Frances Elizabeth Baldwin: Sumptuary legislation and personal regulation in England , reprint u. a. American print. ISBN 0-404-61233-4 .

- ↑ Medieval clothing and textiles, Volume 2, Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Gale R. Owen-Crocker, by Robin Netherton, Gale R. Owen-Crocker, Boydell Press, 2006, ISBN 1-84383-203-8 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Julia V. Emberley : IBTauris Venus and Furs: the Cultural Politics of Fur , 1998.

- ↑ Did you know? . In: All about fur , Rhenania Verlag, Koblenz December 1912, p. 64.

- ^ Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story, Berlin 1941 Volume 3 . Copy of the original manuscript, p. 179 (→ table of contents) .

- ^ Francis Weiss : From Adam to Madam . From the original manuscript part 2 (of 2), (approx. 1980 / 1990s), in the manuscript p. (English).

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: The History of Furrier , Verlag Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1967.

- ↑ signed Jea .: 1900 - The year of birth of fur fashion . In: Hermelin, XL. Vol. 2/1970, Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Frankfurt, Leipzig a. a., p. 34.

- ^ Jean Heinrich Heiderich: The Leipziger Kürschnergewerbe . Inaugural dissertation at the philosophical faculty of the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität zu Heidelberg, Heidelberg, 1897, p. 101.

- ↑ Editor Die Pelzwirtschaft : The importance of the Berlin fur industry . The fur industry, trade journal for the tobacco trade. January 1, 1965, p. 70.

- ↑ a b Dr. Paul Schöps, Leipzig: The way to the fur city. From documents and personal experience , in "Die Pelzwirtschaft", Verlag Die Pelzwirtschaft, Berlin, January 1, 1965 (anniversary edition for the 60th anniversary), pp. 16–34.

- ↑ a b Irene Guenther: Chic ?. Fashioning Women in the Third Reich , Oxford, Berg Publishers 2004, ISBN 1-85973-717-X .

- ^ Frank, Niklas: Meine deutsche Mutter , Munich, C. Bertelsmann Verlag, 2005.

- ^ See also Almut Junker: Frankfurt Macht Mode 1933–1945 , book accompanying the exhibition of the same name from March 18 to July 25, 1999, Historisches Museum Frankfurt am Main.

- ↑ see Wikisource, Henry Ford, The International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem / Chapter 16.

- ↑ Manfred Unger, Hubert Lang: Jews in Leipzig - A documentation for the exhibition on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the fascist pogrom night in the exhibition center of the Karl Marx University of Leipzig from November 5 to December 17, 1988 , editor Council of the Leipzig District, Dept. Culture. P. 151.

- ↑ Manfred Unger, Hubert Lang: Jews in Leipzig , pp. 16-17.

- ^ A. Ginzel: The tobacco industry after the Second World War in the fur industry . Volume XIX New Series, 1968/1969, No. 6, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps. P. 7.

- ^ The Frankfurt trade fair until 1950. JHS, archived from the original on October 8, 2011 ; Retrieved March 15, 2009 .

- ↑ Editor: Mink clothing - the hit for over ten years. In: Pelz International . Issue 4, Rhenania-Fachverlag, Koblenz, April 1984, p. 34.

- ↑ The American mink has been bred in the USA since around 1900. With the European variety "this would never have been possible".

- ↑ Horst Keil: The trade in raw fur hides in the GDR . Central control center for information and documentation of the Institute for Recording and Buying Agricultural Products, Berlin (Ed.) 1967, pp. 12-13. → Table of contents .

- ↑ Harald Lachmann: Rhapsody in mink with hammer blow . In: Supplement to the Leipziger Volkszeitung, 25./26. February 1989, p. 9.

- ↑ a b collective of authors: tobacco goods production and fur clothing , VEB Fachbuchverlag Leipzig, chapter aim of the tobacco industry in the GDR , 1970, pp. 24, 52.

- ↑ Horst Keil: The trade in raw fur fur . Institute for the collection and purchase of agricultural products, Berlin 1967, pp. 48, 49.

- ↑ The advertisements show (to this day) celebrities in a mink coat, without any attribution and the simple question What becomes a legend most? , see. Advertising: the Best One-Liners , Time online, January 2, 1978.

- ↑ Richard Leakey : Wildlife - A Life for the Elephants . S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-10-043208-8 , p. 13.

- ↑ Lucy Jones: Greenland takes up the fight for Inuit hunters , The Guardian , October 13, 1999.

- ↑ {{Web archive | url = http: //www.inuit.org/index.asp? Lang = eng & num = 280 | wayback = 20070720220543 | text = - | archiv-bot = 2018-12-01 22:12:21 InternetArchiveBot }} (Link not available) Statement by the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ІСС) on Paul McCartney's fur boycott.

- ^ Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Animal Health and Welfare on a request from the Commission on the Animal Welfare aspects of the killing and skinning of seals . The EFSA Journal (2007) 610, 1-12.

- ↑ Parliament No. 18–19 / April 28, 2008 Michael Klein: Import ban on seal skins .

- ↑ EU votes for a full ban on seal products, Injustice is served: EU Council favors political expediency over science and law ( Memento of April 22, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), press release of the Fur Institute of Canada , Ottawa, March 27, 2009.

- ↑ Walter Langenberger: The fur development of the last few years . In. The fur industry No. 3, March 1989, p. 32.

- ^ Hugh Brody: Living Arctic: Hunters of the Canadian North , ISBN 0-571-15096-9 University of Washington Printing, August 1990.

- ↑ Stern December 18, 2005 Is fur wearable again? , by Cathrin Dobelmann / Jochen Siemens / Katrin Wilkens.

- ↑ a b Christiane Binder and Nadja Pastega: Trophy of Prosperity (PDF; 761 kB), Facts January 12, 2006.

- ^ Pelzmarkt : Auction report Copenhagen Fur June 16-22 , 2010 , August 2010, Deutscher Pelzverband e. V., Frankfurt / Main, p. 2.

- ↑ If the author is not stated: Copenhagen Fur 5th to 13th September 2017 . In: Pelzmarkt, Newsletter of the German Fur Association , September 2017, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ On the nightmare to enjoy the lust for fur , Die Welt , November 2006, by Inga Griese.

- ↑ Pelz, brochure “Carrying Fur - A Question of Conscience” (PDF; 224 kB) from the German Animal Welfare Association, early 1990s.

- ^ Documentation of actions of the Animal Liberation Front

- ↑ Janet Louise Parker: Jihad Vegan. ( Memento of July 14, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) at: newcriminologist.com , June 20, 2005.

- ↑ a b SÜDWESTRUNDFUNK, Report Mainz, January 8, 2007, suffering for luxury: Why fur animals can continue to be tortured in Germany , Thomas Reutter.

- ↑ European Commission Health & Consumer Protection Directorate-General, Directorate C - Scientific Opinions, Report of the scientific committee on Animal health and Animal Welfare, December 12/13 2001.

- ↑ Ordinance of the Federal Ministry for Consumer Protection, Food and Agriculture , Second Ordinance amending the Animal Welfare and Farm Animal Husbandry Ordinance , Berlin, June 10, 2005.

- ↑ Martin Balluch: Continuity of Consciousness , Guthmann-Peterson, Vienna 2005.

- ↑ Tom Regan: The Case for Animal Rights , University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles 1983.

- ^ Peter Singer: Practical Ethics , Reclam, Stuttgart 1984.

- ^ Animal rights, an interdisciplinary challenge , published by the Interdisciplinary Working Group on Animal Ethics Heidelberg (IAT, a student initiative), Heidelberg 2007, Harald Fischer Verlag.

- ↑ Helmut F. Kaplan: funeral feast . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1993, p. 29.

- ↑ Pelzgegner shows remorse , August 7, 2009 - MAINZ, by Silvia Dott, Allgemeine Zeitung.

- ↑ June 13, 2006 Berlin State Security investigates animal rights activists, group desecrated grave , accessed on animal-health-online February 2009.

- ^ Franz Kiener: clothing fashion and people . Ernst Reinhardt Verlag, Munich and Basel, 1956, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Moshe Newiasky: The Russian fur and leather industry . Inaugural dissertation of the Philosophical-Historical Department of the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Basel, Kaunas 1927, p. 61.

- ↑ Lukas Hartmann : Woman in fur. Life and death of Carmen Mory. Novel. Nagel & Kimche, Zurich 1999, ISBN 3-312-00250-8 .

- ↑ Culture theory, by Ortrud Gutjahr, in Königshausen & Neumann, 2005, ISBN 3-8260-3067-2 .

- ↑ Meret Oppenheim - retrospective: with very little, much. 210 colored illustrations. Edited by Therese Bhattacharya-Stettler, Matthias Frehner. Hatje Cantz Verlag, hardback, 359 pages, ISBN 3-7757-1746-3 .

- ↑ Valerie Steele : Fetish. Fashion, sex and power . New York 1996.

- ^ Patrizia Gentile, Jane Nicholas: Contesting Bodies and Nation in Canadian History . University of Toronto Press, 2013.

- ^ Indian giving: economies of power in Indian-white exchanges, Native Americans of the Northeast: Culture, History, & the Contemporary, by author David Murray, Verlag Univ. of Massachusetts Press, 2000, ISBN 1-55849-244-5 .