History of Iceland

The history of Iceland begins in the 3rd century AD at the earliest. Roman coins of unknown origin that were found on Iceland date from this period . So it is not possible to say with certainty when the first people reached Iceland. The coins found could for centuries as cash circulating, and only with the Vikings have arrived on the island.

First reports: The Thule myth

Older research has long assumed that Pytheas of Marseille, an astronomer, mathematician and geographer , was the first to mention the island in his travelogues . He extended his research trips to northwestern Europe probably as early as the fourth century BC . Although his reports are lost, they can be found as quotations in Strabo in part, albeit without context . Pytheas found a land he called Thule , six days' journey north of Britain , near the Arctic Ocean . In this country, he reports, the sun was over the horizon all night during the summer solstice .

However, Pytheas seems to have indicated that Thule was settled. That would exclude Iceland as there is still no archaeological evidence from this early period there. In addition, one concludes from his description that he has found mainland and not an island, and therefore it can be concluded that he really refers to parts of present-day Norway . It is also believed that northern Europe must have been colder in the time of the Pytheas than it is today, and therefore it is believed that he landed further south in Scandinavia .

According to Pytheas, the name Thule has long been used as a synonym for northern Europe.

The first settlement

Archaeological evidence

An archaeological excavation on the Westman Islands uncovered the foundation walls of a typical Norwegian longhouse beneath a layer of lava that was dated to the 7th century.

The closest archaeological evidence of human arrival in Iceland is three Roman copper coins dating from around AD 270-305. Two coins were found in the ruins of a farm from the time of the conquest of the land; H. the time of the settlement by the Vikings and their families (870–930), near Bragðavellir in Hamarsfjörður , the third found on the beach of Hvalnes in Lón . They probably come from the same hoard and are the only remains of the time of the conquest. The sites are in southeastern Iceland, where the seafarers from Europe mostly landed.

By analyzing pollen , colonization can be seen in a change in vegetation and soil profile . Such a "settlement layer " was found just under a tephra layer (volcanic ash) during excavations in Þjórsárdalur in southern Iceland and was associated with an eruption of the Vatnaöldur crater series in southern Iceland, which is part of the Bárðarbunga volcanic system . Similar ashes were found in peat bogs in Ireland and dated to 860 ± 20 AD cal.

Excavations in Reykjavík yielded numerous 14 C dates that are significantly older than the settlement date known from written records (around 780 AD). However, all samples came from wood ( birch and larch ), only one from grain (U-2674), which was of a much later date. In Herjolfsdalur in Vestmannaeyjar it was dated to 690 AD (cal.), Also with birch and larch charcoals. However, these early dates could also be traced back to the use of old wood. On closer examination it turned out that cereals that came from the same localities as the unusually early dated charcoal usually had much more recent 14 C dates. The wood used could therefore be driftwood or storage wood and therefore much older and not precisely indicate the time of use, unlike the grain, which very likely came from the last harvest. The grain was dated around 890.

Excavations have now shown early settlements from the 7th and 8th centuries on the Westman Islands. The traditional first settlement by runaway Irish slaves is evidently a founding myth.

Irish monks?

The Landnámabók refers to reports by the Irish monk Beda:

"Í aldarfarsbók þeiri, he Beda prestr heilagr gerði, he getit eylands þess, he Thile (var .: Thyle) heitir, ok á bókum he says, at liggi sex dægra sigling í norðr frá Bretlandi. Þar, sagði hann, Eigi koma dag á vetr ok Eigi nótt á sumar, þá he dagr er sem lengstr. Til þess ætla vitrir menn þat haft, at Ísland sé Thile kallat, at þat er víða á landinu, er sól skínn um nætr, þá er dagr er sem lengstr, en þat er víða um daga, er sótt sér eigi, þá er nóttól sér eigi sem long. "

“The book of the passage of time ( De temporum ratione ), written by the priest Bede the Saint, mentions the island called Thule, and books say that it is a six dœgr sea voyage north of Britain. There, he said, it wouldn't be day in winter and night in summer when the day was the longest. Understandable people therefore assume that Iceland was called Thule, because in the country the sun shines a long way at night when the day is longest, but the sun is largely invisible during the day when the night is longest is. "

It is very likely that Beda's report ultimately goes back to Pytheas . Where Pytheas himself thought his Thule was is controversial. After Pytheas, the Irish were the next to explore the North Atlantic. Saint Patrick , who came to Ireland in 432 AD , had converted some to Christianity . As missionaries , they also traveled to the northern islands and the continent. Presumably the Irish monks knew the Pytheas account of Thule and searched Iceland. At the beginning of the 8th century, the Irish reached the Faroe Islands and shortly afterwards probably Iceland.

Ari Þorgilsson hinn fróði, Iceland's first historian to write in the national language, mentions the stay of Irish monks in Iceland in his Íslendingabók (The Book of Icelanders) from 1125.

At the time, in the 9th century, when the Norwegians came to Iceland, priests may have lived there, who the Norwegians called papar (priest). The word papar is a loan word from Irish : pob (b) a or pab (b) a , hermit or monk. The Irish, on the other hand, borrowed the term from Latin: papa , father. Since they did not want to live among the newly arrived " pagans ", they left the island, according to Ari. Others suspect that volcanic eruptions drove them out, or that they fled or merged with the immigrating Northmen . The Landnámabók (The Book of Settlement of Iceland) also agree that papar settled in the Siðar district when the Norwegian Ketill hinn fiflski arrived in Iceland.

The presence of Irish monks has still not been proven by archaeological finds, although a very thorough search for them has been carried out on the island of Papey, which is supposedly named after them, in the southeast of Iceland.

First Vikings in Iceland

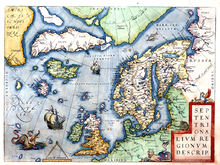

A Norwegian Viking ship with the Norwegian / Faroese Naddoddur on board got lost on the way to the Faroe Islands around 860 AD in the storm in what is now Reyðarfjörður in East Iceland. He first named the island Snæland (German: "Schneeland").

A few years later, the Swede Garðar Svavarsson wintered in Húsavík in North Iceland and named the island after himself, Garðarsholmur . A member of his ship's crew named Náttfari and two slaves, a woman and a man, ran away from him. They settled in a valley near Húsavík. But because this settlement came about by chance or because Náttfari was not elegant enough, he is nowhere regarded as the first settler. The historicity of the trips Naddodds and Garðars are, however, controversial, as it is assumed that the route to Iceland on the islands north of Scotland was known for a long time.

The third visitor is said to have been Flóki Vilgerðarson , who was looking for a settlement. After a catastrophic winter, in which his sheep starved to death from lack of hay, and another year, Flóki returned to Norway. Much later he returned to Iceland, where he lived until the end of his life. He gave Iceland its final name "Ice Land". He is said to have got the idea from the sight of drift ice from Greenland, which he saw from a mountain in the northwest.

Ingolfur Arnarson

Ingólfur Arnarson is named as the official first settler . He drove to Iceland with his foster brother Hjörleifur Hróðmarsson and their belongings, both of which could be transported, and the 870 families, because he had lost all of his country in Norway due to manslaughter lawsuits and the manpower paid for it. He reached Iceland and settled on the south coast at Ingólfshöfði near today's Skaftafell National Park . Hjörleifur continued sailing and settled near what is now Vík . He was slain by his Irish slaves, who then sailed to a group of islands off the coast. Ingólfur later killed the slaves, and because the Irish were called "Westmen" by the Vikings, he called the archipelago " Westman Islands ". He later moved his settlement to Reykjavík. It has become common to assume that Iceland was first settled by Ingólfur in 874, while in reality it is to be assumed a little earlier.

Landing time (874 to 930)

In the year 874 the first permanent settler, Ingólfur Arnarson , settled in the area of today's capital Reykjavík . As is customary with the Vikings , he wanted to settle down where the pillars of his high seat thrown into the sea had washed ashore. But his slaves only found them a few years later. He was followed by around 400 chief families from Norway , all of which are mentioned in the Landnámabók . Archaeological excavations have now shown that Vikings from Norway actually settled in this area with their Celtic slaves (especially women) in the 9th century .

The period between 870 and 930 is considered to be the era of the conquest . Most of the habitable land is said to have been distributed by then.

In the meantime, however, excavations have shown that immigrants from southwest Norway had settled on the Westman Islands earlier, i.e. in the 7th and 8th centuries . They are not mentioned in the Landnámabók.

The time of the Free State (930 to 1262)

Saga time (930 to 1030)

The Althing

Local assemblies developed soon after the conquest. In the southwest the development apparently started from the son Ingólfs Þorsteinn Ingólfsson . Over time the development found more and more supporters and resulted in a union of all gods in a single republic with a single general assembly. This required a legal framework. The Goden therefore sent the wise Úlfljótur to Norway to collect suggestions for a corresponding regulation. After three years he returned successfully. He was the first law speaker in Iceland.

But no Gode wanted to give up land for this purpose. Only one farmer near Reykjavík was found guilty of the murder of a slave and a free man, which is why he was banished and expropriated. His land bordered the Þingvallavatn . The land fell to the general public and became a new place of assembly. In 930 the first meeting of the Althing took place in Þingvellir . Significantly, the translation of the place name means: assembly level. The Althing was an annual gathering of the Goden, the country's oligarchy , which was responsible for legislation and justice. One can speak of the first parliament in Northern Europe that still exists today . It has always existed, even if it has since degenerated into almost insignificance. Similar democratic structures, it had previously only in Saxony Assembly in Marklo and earlier still in Greece of antiquity given.

The land was also divided into four areas ( landsfjórðungar ) in 965 to simplify administration and jurisdiction. In every part of the country there were local judges for less important cases. The lack of executive power proved problematic , as unresolved legal cases often developed into feuds between powerful sexes that lasted for years . This fateful mechanism is also described in the sagas such as the Laxdæla saga .

Voyages of discovery

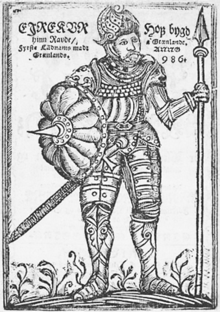

During this time the important voyages of discovery to Greenland and North America also take place , which one should rather think of as a chance hit. So did Erik the Red to leave because of some differences with other chiefs Iceland 982 and sailed from Breiðafjörður to the west, where a few years earlier sighted other Viking country and one - had made settlement attempt - but failed. Erik the Red actually succeeded in founding two settlements in Greenland with 800 supporters due to the much more favorable climatic conditions in the Middle Ages . Contact with the motherland lasted for centuries and, as far as has been proven, only ceased in the 15th century.

From Greenland probably in the year 1000 Leif Eriksson , his son, landed on the coast of North America, which he called Vinland . The settlements founded there (proven in L'Anse aux Meadows and in Point Rosee , both in Newfoundland ) could only hold out against the overwhelming power of the indigenous population for a short time.

Christianization

The year 1000 was to be of decisive importance for the people living in Iceland in other ways as well.

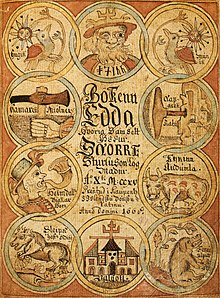

There is little reliable information about the details of the beliefs of the Icelanders before Christianization . It is assumed that the Germanic gods, also known on the mainland, were worshiped. However, tensions had arisen in the very important trade relations with Norway in recent years. One of the reasons for this was that the Norwegian ruler Ólafr Tryggvason was already converted to Christianity. And this insisted - for reasons of power politics, among other things - on the Christianization of Iceland. After much back and forth Christianity, which was already known to some extent through the Irish slaves, became at home in the country. The missionary bishop Friedrich also contributed to Christianity .

In the year 1000, finally, the decision was made at the Althing in Þingvellir that declared Christianity the state religion , alongside which the pagan gods were initially allowed to continue to be worshiped. The scene at Goðafoss has been handed down , in which the last images of gods are handed over to the river in grand gestures. It is also depicted in a stained glass window in Akureyri Cathedral .

Peace Time (1030 to 1180)

As the first Icelandic bishop Ísleifur Gissurarson was consecrated in Bremen in 1056 . Skálholt in the south of the island was chosen as the bishopric . Initially, however, ecclesiastical and secular power were mostly still united in the same hands, the chiefs had also become Christian priests at the same time. Thus the Church in Iceland did not become an independent power in the country for a long time, but was always subject to the national laws. A church tithe was introduced in 1096/97, and in 1106 the second diocese was founded in Hólar . In the years that followed, Icelanders quickly got used to Christianity and many churches were built. In addition, a number of monasteries were founded in the 12th century , which, together with the affiliated schools, had a very positive effect on popular education.

On the other hand, it had a negative effect that the church tithe also flowed to the Gods in their double function as priests and wealthy landlords, so that individual persons and genders could accumulate a great deal of power. This should cause numerous disputes from the 13th century.

Meanwhile, the Norwegian Crown continued to try to force the independent country under their rule. However, this initially failed. In 1022 a pact was concluded in which the rights and obligations of both countries were set out. It remained quiet in the country until around 1180, which is why one speaks of a time of peace.

Sturlung Period (1180 to 1262)

The next 100 years or so put an end to this quiet age. Bloody gender feuds and civil war-like conditions replaced the peaceful epoch.

The power of the Norwegian kings had increased and they found a powerful ally in the Church. The Bishop of Hólar had subordinated all church decisions in Iceland to the Archdiocese of Nidaros in Norway , and the church had an interest in finally separating secular from ecclesiastical power in Iceland and thus gaining more influence there itself. In 1237 both Icelandic bishops became vacant at the same time and they were quickly filled with two Norwegians.

The Norwegian King Håkon Håkonarson now cleverly played off individual mighty figures against each other. As in the rest of Europe at the time, it was customary for upmarket young people to go to a royal court and live there for some time in the entourage of kings or nobles in order to obtain a proper education. Håkon took a special oath of loyalty from these young Icelanders at his court and thus had his own followers in the country. The first of these youngsters was Snorri Sturluson . However, he does not seem to have taken his vows too seriously and preferred to pursue his own goals, so that he and his sons were finally murdered in Reykholt in 1241 on behalf of the Norwegian king . As early as 1238, a kind of battle between the followers of the Sturlung family and other Goden had taken place, in which the Sturlungs had largely been wiped out.

Finally Norway put the Icelanders under pressure with a trade boycott , and so it came about that in 1262 the Old Treaty (Icelandic: gamli sáttmáli ) was drawn up and the Duke Gissur, appointed by Norway, took over power in the country.

Norwegian rule (1262 to 1380)

Although this was actually stated differently in the treaty, the Norwegian krone intervened very quickly in Icelandic life, jurisdiction and administration. First, in 1271 with the Jónsbók , a code of law, the Icelandic jurisdiction was replaced by the Norwegian. The Althing was disempowered as quickly as possible , the gods were replaced by territorially closed administrative districts, and the country was ruled by one or, for a time, several Norwegian governors .

From 1354 the king even leased the land to his followers, who could exploit it at will.

At the same time, the power of the church grew . In 1275 the Bishop of Skálholt , Árni Þórlaksson , introduced his own canon law . The church tenth flowed from now on to the church itself, from 1297 onwards all goods on which churches were built became the property of the mother church, so that the mother church was able to amass considerable wealth and land over the centuries. In the 16th century, she even owned almost half of Iceland's landed property. Often foreigners were appointed as bishops from Rome or Norway , acting more for their own benefit than for the benefit of the Icelanders.

The 14th century can also be described as a century of disasters in Iceland. In 1341 the volcano Hekla erupted so violently that numerous farms had to be abandoned and agriculture in some cases no longer yielded any income; the result was famine. As in the rest of Europe, a major epidemic spread here .

Danish rule (1380 to 1944)

From the 14th to the 18th century

politics

From 1397 to 1448 Iceland was part of the Kalmar Union , an association of the Scandinavian kingdoms of Norway, Sweden and Denmark under Danish rule. In 1662, almost simultaneously with Louis XIV of France, the Danish King Friedrich III. an absolutism . The Icelanders had to sign their recognition of the absolute monarchy and thus lost their last independent rights.

On the other hand, the protection of the Danes did not go too far. In 1627, the Westman Islands and some coastal towns were sacked by Algerian pirates ; about 300 women and young people were abducted and sold into slavery, of which only about a third could be bought back. Since Algeria was part of the Ottoman Empire at the time, the raid is referred to as Tyrkjaránið in Icelandic historiography .

trade

After the Norwegians had a trading monopoly with Iceland up to the 14th century , the English and Danes also got on board in the 15th century. Even the German Hanseatic League played along. This can also be explained by the fact that the Icelanders had discovered an interesting new export good: fish. Since a change in the climate in the late Middle Ages had made agriculture less profitable, they had looked for new food options and discovered that the coasts around the island were very rich in various types of fish.

Whereas in earlier centuries mainly the English and the Hanseatic League had dominated the trading scene with Iceland, at the beginning of the 17th century the Danes assured themselves the monopoly over this trade. That was bad for the Icelanders. Even everyday goods became scarce and, for many, unaffordable. In the 17th century, Icelandic export goods included fish products, wool, sheep meat, feathers and down, fox skins, knitwear (gloves and stockings) and sulfur. The Danish royal family was very interested in hunting falcons .

Emergency and improvement approaches, emigration

At the beginning of the 15th century, another plague epidemic had killed around 25,000 people.

And the plight of the population continued to increase so that in a census at the beginning of the 18th century there were around 4,000 farms abandoned. A smallpox epidemic in 1707 also killed another 18,000 of the debilitated people, so that the population had shrunk to around 30,000.

Finally, the Danish king also realized that this had to be remedied - not least because he was losing money himself. The trade monopoly was subsequently relaxed somewhat; However, it did not really open up until after the Laki disaster in the 1780s. After the eruption of the Laki crater in 1783 and 1784, discussions were held in Iceland and at the Danish court about completely evacuating the island and relocating its inhabitants to the Danish West Jutland , which was technically impossible at the time. The ash rain and enormous gas emissions during the eight-month volcanic eruption in the Grímsvötn system had darkened the sun, produced dry fog and poisoned the vegetation. Large parts of the livestock died. There was a famine, and the natural disaster (known by the Icelandic name Móðuharðindin ) killed around 10,000 Icelanders (about a fifth of the population at the time).

Around the middle of the century, the Icelandic Skúli Magnússon tried to build up a domestic industry by founding manufactories . But again he was so boycotted by the Danish merchants that he had to give up 15 years later and his Icelandic partnership was taken over by the Danes.

From the 1870s onwards, numerous Icelanders emigrated to North America. In 1874 a single ship brought over 350 Icelanders to Nova Scotia , Canada. Most settled in Markland, where a census was taken in 1876. Many of them also settled in Manitoba , for example in the area of today's Hecla-Grindstone Provincial Park in Lake Winnipeg . There New Iceland was born .

religion

In 1536 Christian III. Denmark enforced the Evangelical Lutheran denomination for his country, Norway and the Faroe Islands . He benefited from this, as he was now the head of the church himself and was thus able to dispose of the wealth and goods of the church.

When the bishopric of Skálholt became vacant, the king appointed a Protestant who ensured the rapid spread of the Protestant denomination. However, the Catholic bishop Jón Arason on Hólar opposed this . He even initiated a Counter Reformation . However, he could not last long and was executed in Skálholt in 1550 with two of his sons. Since then, Catholicism has not played a major role in Iceland.

After Christian IV's decree against witchcraft , alleged witches and magicians were persecuted in Iceland, which Jón Guðmundsson the Wise narrowly escaped.

From the 19th century to independence

First attempts at independence

The first half of the 19th century proved to be a difficult time for Icelanders.

In 1800 the Danes completely abolished the powerless Althing ( Alþingi ). The bishopric in Hólar was dissolved and that moved from Skálholt to Reykjavík . In addition, the Napoleonic wars had the effect that shipping traffic was reduced. This triggered another shortage situation in the country.

In the Peace of Kiel Norway fell to Sweden , Iceland stayed with Denmark .

Icelanders who had studied in Copenhagen brought the ideas of nationalism , which were very widespread in mainland Europe at the time, to Iceland in the first half of the century , which quickly gained a foothold there. Reykjavík became the intellectual center of the country, and so the rise of Iceland as an independent nation was combined with the rise of the city. The intellectual center of the political independence movement remained in Copenhagen. Jónas Hallgrímsson, one of the founders of the magazine " Fjölnir " campaigned with other intellectuals in his articles for the renaissance of the ancient thing in Thingvellir, but was defeated by the pragmatist Jón Sigurðsson (1811–1879), who was more concerned with modernization and who was himself for Reykjavík.

King Christian VIII proposed the establishment of a special advisory assembly in Iceland in 1840, and in 1845 the newly established parliament, the Althing, was constituted in Reykjavík. However, it had no political power, only advisory function towards the Danish throne. Nevertheless, from now on Reykjavík was the capital of the country.

Jón Sigurðsson became the leader in the struggle for Iceland's independence . In 1848 he had to come to terms with the fact that although the constitutional monarchy was introduced in Denmark , Iceland did not become independent despite massive demands. In 1854 the Danish trade monopoly was lifted. In 1873 Iceland celebrated the thousandth anniversary of the land grab . In 1874 the Althing received limited legislative rights. The country now had its own constitution , but still no executive branch of its own .

In 1882 women had limited voting rights when they participated in local elections. In 1882, the king agreed to change the restrictions so that widows and other unmarried women who headed a farm household or otherwise ran an independent household were given the right to vote and stand for election in local elections.

The country at the turn of the century

Iceland experienced a rapid upswing: industrial companies were founded, fishing was expanded, schools, hospitals and roads were built. With a decreasing demand for labor in agriculture, the rural exodus began. On the other hand, the population had almost doubled in 100 years (from 47,000 in 1801 to 79,000 in 1901).

In 1904 a referendum ruled that an Icelander should fill the ministerial post for Iceland in Denmark and represent his country externally. The first such minister was Hannes Hafstein . He introduced the telegraph in Iceland, which gave it a connection to the modern age. On June 26, 1905 at 10:38 p.m. the first radio telegram from Cornwall arrived. A submarine cable was laid the following year.

Iceland's Olympic history began in 1908 .

In 1915, relatively early on, women were given the right to vote and to stand as a candidate . However, according to this law, women and servants had a voting age of 40 years. This age limit should decrease annually by one year until it reaches 25 years. This law was then ratified by the Danish King on June 19, 1915. As in certain other countries, the introduction of women's suffrage in Iceland did not cause any violent reactions. In 1920 universal suffrage for people aged 25 and over was introduced.

Prohibition also came into force in Iceland in 1915 .

On December 1, 1918, the Union Treaty with Denmark was signed. This ushered in the Islands independence from Denmark, which has since only loosely by Real Union with Denmark under Christian X was connected. The contract was set up for 25 years, after which a referendum was to be held on complete independence.

Educational aspirations

The Icelandic tradition and with it literature had already flourished again in the 19th century. In the course of Romanticism and its predilection for bygone eras, the sagas were revisited . Numerous writers made a name for themselves, including Magnús Stephensen and Jónas Hallgrímsson .

In 1907 compulsory schooling was introduced and the University of Iceland ( Háskóli Íslands ) was founded in Reykjavík in 1911 .

The second World War

During the First World War one had rather benefited from deliveries of wool and fish. There was a boom in Iceland in the 1920s; but also the world economic crisis of the 30s could be felt.

On September 1, 1939, the Second World War began with the German invasion of Poland . From April 9, 1940, the Wehrmacht occupied Denmark and Norway in the Weser Exercise Company .

The British occupied Iceland on May 10, 1940, in violation of its neutrality and under the pretext of protecting it from German occupation. The USA took over the occupation of Iceland from July 7, 1941 to relieve the British Navy and Army - six months before they officially entered the war .

The British and US Americans advanced Iceland's economic development, not least by creating numerous jobs in the construction of British and American naval and army facilities.

After the Icelanders had expressed according to the Union Treaty in a referendum in May 1944 for the independence of the Speaker of Parliament announced on 17 June 1944 in Thingvellir before thousands of people the republic, as in the first article of the new constitution has been written to the subsequently Sveinn Björnsson was sworn in as the first president.

On November 10, 1944, the Icelandic ship Goðafoss was sunk by the German submarine U-300 with a torpedo. It sank in Faxaflói Bay within 7 minutes . 24 people drowned; 18 Icelanders and one British were able to save themselves. The wreck of the Goðafoss was apparently found in 2016 off the coast near Garður at a depth of around 40 meters under a layer of sand.

The German journalist Alfred Joachim Fischer first reported on the unclear attitude of the Icelandic authorities to the Holocaust in 1957.

Independent Republic of Iceland (since 1944)

Political developments

Iceland and the world

Iceland quickly made a name for itself in world politics: after the recommendation of admission to the United Nations by Resolution 8 of the UN Security Council , it joined the international community on November 19, 1946, the OECD in 1948 and was one of the founding members in 1949 of NATO and the Council of Europe . The country also joined the Nordic Council in 1952 . It never had an army of its own, but in 1951, after much discussion, approved a US military base in Iceland.

In 1986 a summit meeting between US President Ronald Reagan and Soviet Prime Minister Mikhail Gorbachev took place in the Höfði house in Reykjavík .

In 1991 Iceland became the first country to recognize the sovereignty of Estonia , Latvia and Lithuania .

From 1980 to 1996 Iceland had Vigdís Finnbogadóttir, the world's first democratically elected female president.

The "Cod Wars"

There were repeated disputes over the rich fishing grounds around Iceland, especially with Great Britain . This intensified in the years 1952 and 1958 to the so-called cod war , as the Icelanders first expanded the fishing zone around the island from three to four nautical miles (1952) and finally in 1958 to twelve nautical miles due to overfishing due to international competition . The latter was accepted by all countries except England. Three years and some almost bloody clashes later, however, the English also had to be satisfied with it. In 1972 the dispute broke out again, and this time Germany did not want to accept the expansion of the zone to 50 nautical miles. In 1976, when Iceland expanded to 200 nautical miles , it even temporarily broke diplomatic relations with Great Britain after violent clashes. Finally, the European Union expanded its own fishing zones to the same extent. Since then, Iceland has indisputably the sole right to use the fishing grounds within its 200-mile zone.

Effects of the financial crisis (from 2008)

From around 2002 until the outbreak of the international financial crisis in 2007 , three major Icelandic banks ( Glitnir , Landsbanki and Kaupthing Bank ) borrowed enormous sums of money on foreign capital markets. Shortly before the collapse of these three banks in October 2008, they had liabilities on their books that were roughly ten times the gross domestic product of Iceland.

German banks - above all the Deutsche Bank , DZ Bank , DekaBank , numerous Landesbanken and the state development bank KfW - were involved in billion-dollar transactions and in the end posted horrific losses. The head of the Icelandic central bank was involved in the activities of the big banks; the Icelandic government appointed the Norwegian Svein Harald Øygard as his successor in February 2009. The Icelandic krona exchange rate fell sharply during the crisis . The then Icelandic government under Prime Minister Geir Haarde brought large parts of the financial sector - including the three big banks Glitnir, Landsbankinn and Kaupþing - under state control.

Since then there has been open thought about Iceland joining the European Union and the subsequent introduction of the euro as a currency.

The social democratic party Allianz (Samfylkingin) ended the ruling coalition with the liberal Independence Party (Sjálfsstæðisflokkur) on January 26, 2009 . From February 2, 2009, a minority government consisting of the Left-Green Movement and the Alliance, chaired by Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir as Prime Minister, took over the affairs of state, which was supported by the Progress Party . The Icelandic public had expressed their dissatisfaction with the situation and the government with regular demonstrations and thus contributed to the change of government.

An early parliamentary election took place on April 25, 2009 , in which the coalition of the social democratic alliance and the left-green movement won an absolute majority. Prime Minister Sigurðardóttir said she wanted to push Iceland's accession to the EU. After the Icelandic parliament had voted in favor of an application for membership, the application to join the EU was submitted on July 23, 2009. Accession negotiations started on July 27, 2010. After the parliamentary elections in 2013 , the new conservative and EU-skeptical government led by Prime Minister Gunnlaugsson decided to suspend negotiations for an indefinite period. Further early parliamentary elections were held on October 29, 2016 and October 28, 2017 .

Other important events and developments

In 1955, the writer Halldór Laxness received the Nobel Prize for Literature and made modern Icelandic literature known to the world. In 1972 the legendary World Chess Championship match between Boris Spasski and Bobby Fischer took place in Reykjavík and ended with a clear victory for the American.

Some major volcanic eruptions have occurred since World War II : In 1963, the island of Surtsey, part of the Westman Islands, was created by an undersea volcanic eruption. In 1973, the Eldfell eruption devastated Heimaey Island , also one of the Westman Islands. In 1996, after an eruption under the Grímsvötn in Vatnajökull, an unusually strong glacier run took place on Skeiðarásander and destroyed parts of the ring road. After the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull in 2010 , air traffic in large parts of northern and central Europe had to be suspended for several days in mid-April 2010 due to the volcanic ash that had escaped, which was an unprecedented disruption to air traffic in Europe as a result of a natural event.

In 1977, six defendants in the Guðmundur and Geirfinnur case , which is considered the "most spectacular criminal case" in Iceland, were sentenced to long prison terms. 44 years later, the convicts were acquitted by the Hæstiréttur , the Supreme Court of Iceland, because their confessions had been obtained under pressure and using torture methods. At the beginning of 2020, the acquitted or their family members received compensation totaling 815 million Icelandic kronor (around six million euros) from the state treasury.

Since the Second World War, the country has developed rapidly into a modern industrial nation that has a good reputation, especially in the high-tech sector . The rural exodus continued, however, so that two thirds of all Icelanders now live in the capital region around Reykjavík .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Margrét Hermanns-Audardóttir: The Early Settlement of Iceland. Results based on excavations of a Merovingian and Viking farm site at herjólfsdalur in the westman islands, iceland . In: Norwegian Archaeological Review 24.1, 1991, pp. 1-9 (there, pp. 10-33, also a detailed discussion of the results by various scientists).

- ^ VA Hall, JR Pilcher, FG McCormac: Tephra dated lowland landscape history of the north of Ireland, AD 750–1150 . In: New Phytologist 125, 1993, pp. 193-202.

- ^ E. Nordahl: Reykjavík from the archaeological point of view . Uppsala 1988.

- ↑ Margrét Hermann-Audardóttir: Islands tidiga bosättning (= Studia Aracheologica Universitatis Umensis , Volume 1). Umeå 1989 (Dissertation, abstract in: Margrét Hermanns-Audardóttir: The Early Settlement of Iceland. Results based on excavations of a Merovingian and Viking farm site at herjólfsdalur in the westman islands, iceland . In: Norwegian Archaeological Review 24,1, 1991, Pp. 1-9).

- ^ Arny E. Sveinbjörnsdóttir, Jan Heinemeier, Gardar Gudmundsson: 14 C-dating of the settlement of Iceland . In: Radiocarbon , 46/1, 2004, pp. 387-394.

- ↑ For the term dœgr see navigation aids

- ↑ His writing Περὶ ὀκεανοῦ ( Perì okeanoũ ) is lost and only passed on in foreign quotations.

- ↑ The tradition is bad. The late quotes are mostly from opponents. Even the ancient geographers were unsure of Thule's alleged location. The first to identify Thule with Iceland was the Irish monk Dicuil 825. After that, the equation Thule = Iceland was common in the Middle Ages. Adam of Bremen took it over in his church history chap. 4, 36.

- ↑ Uwe Schnall: Navigation of the Vikings . Hamburg 1975. p. 140.

- ↑ S. Sunna Ebenesersdóttir et al .: Ancient genomes from Iceland reveal the making of a human population . In: Science 360 (6392), 2018, pp. 1028-1032. doi : 10.1126 / science.aar2625 . Online (researchgate, English) . In cooperation with DeCODE Genetics .

- ↑ DNA study reveals fate of Irish women taken by Vikings as slaves to Iceland , irishtimes.com , June 6, 2018, accessed June 7, 2019.

- ↑ See A second Viking settlement discovered in America Spektrum.de from April 5, 2016

- ↑ Recent studies have come to the conclusion that the old contract in its traditional version is a fake from the 15th century. Patricia Pires Boulhosa: Gamli sáttmáli. Tilurð and tilgangur. Reykjavík 2006.

- ↑ NN: Special History of Iceland . In: John Green, Thomas Astley (ed.): General history of travel on water and on land or collection of all travel descriptions . 19. Vol. Verlag Arkstee and Merkus, Leipzig 1769, p. 50 . Digitized

- ↑ The Icelandic Memorial Society of Nova Scotia still exists there today ( website of the society , accessed on June 19, 2020)

- ↑ Jón Rögnvaldsson's Survey of Icelandic Farms and Population in Mooseland (Markland) February 1878 , accessed June 19, 2020.

- ↑ Passenger List of the SS St. Patrick, 1874 , accessed June 19, 2020.

- ↑ Gunnar Karlsson p. 34.

- ↑ Lovsammling off Iceland XI (1863) S. 628th

- ↑ - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. Retrieved October 3, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 193.

- ↑ Caroline Daley, Melanie Nolan (Eds.): Suffrage and Beyond. International Feminist Perspectives. New York University Press New York 1994, p. 349.

- ↑ June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, Katherine Holden: International Encyclopedia of Women's Suffrage. ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-57607-064-6 , p. 127.

- ↑ Caroline Daley, Melanie Nolan (Eds.): Suffrage and Beyond. International Feminist Perspectives. New York University Press New York 1994, p. 350.

- ↑ Karl-Michael Reineck: General State Doctrine and German State Law. 15th edition, 2007, para. 62 (p. 58)

- ↑ Burkhard Schöbener, Matthias Knauff: General Theory of the State. 2nd edition, CH Beck, Munich 2013, § 6, para. 47 (p. 270)

- ↑ The British occupation of Iceland in World War II (PDF; 255 kB), in: Nordeuropaforum 1/2008 (18 pp.)

- ^ Svein Harald Øygard (2020): In the Combat Zone of Finance - an insider's account of the financial crisis . Lid publishing, ISBN 978-1-91255-565-9 , review here .

- ^ Spiegel Online October 7, 2008: Emergency Act against the Financial Crisis. Iceland takes total bank control

- ↑ derstandard.at: EU holds prospect of Iceland joining bankrupt

- ↑ Morgunblaðið, February 2, 2009

- ↑ FAZ.net : Iceland's parliament applies for EU membership on July 23, 2009.

- ^ DerStandard.at: Accession negotiations with Iceland decided

- ↑ Iceland turns away from the EU. May 22, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2013 .

- ^ All found innocent in Guðmundur and Geirfinns case, 44 years after the supposed crimes were committed. In: icelandmonitor.mbl.is. September 27, 2018, accessed June 11, 2020 .

- ^ Compensation Awarded in Guðmundur and Geirfinnur Case. In: icelandreview.com. February 10, 2020, accessed on June 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Jens Willhart, Christine Sadler: Iceland. Michael Müller, Erlangen 2003, p. 86

literature

- Sveinbjörn Rafnsson, Torsten Capelle : Iceland. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 15, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2000, ISBN 3-11-016649-6 , pp. 524-534. ( available for a fee via GAO , De Gruyter Online)

- Jón R. Hjálmarsson: The History of Iceland from Settlement to the Present, Forlagið , Reykjavík 2009, ISBN 978-9979-53-522-5 .

- Vilborg Auður Ísleifsdóttir: The introduction of the Reformation in Iceland 1537–1565. Frankfurt am Main 1996.

- Guðni Thorlacius Jóhannesson: The History of Iceland , Greenwood, Santa Barbara, Ca. 2013, ISBN 978-0-313-37620-7 .

- Jón Jóhannesson: A History of the Old Icelandic Commonwealth. University of Manitoba Press, 1974.

- Gunnar Karlsson: Iceland's 1100 years. The history of a marginal society , Hurst, London 2000, ISBN 1-85065-414-X .

- Gunnar Karlsson: Den islandske renæssance. In: Anette Lassen (ed.): Det norrøne og det nationale. Conference 17./18. March 2006 in Reykjavík. Reykjavík 2008, pp. 29-39.

- Gunnar Karlsson: A Compact History of Iceland , Mál og menning, Reykjavík 2010, ISBN 978-9979-3-3155-1 .

- Sigurður Líndal: A Little History of Iceland . Translated from the Icelandic by Marion Lerner. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-518-46265-2 .

- Esbjörn Rosenblad / Rakel Sigurðardóttir-Rosenblad: Iceland from the past to the present, Mál og Menning, Reykjavík 1999, ISBN 9979-3-1900-3 .

- Klaus Schroeter: Development of a Society. Feud and alliance among the Vikings . Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-496-02543-3 .

- Jens Willardt, Christine Sadler: Island, 8th edition, Michael Müller Verlag , Erlangen 2018, pp. 104–129, ISBN 978-3-95654-397-5 .

- Bernard Hennequin, L'Islande, le Groenland, Les Féroé Aujourd'hui. les éditions ja 1990, ISBN 2-86950-163-3 .