Attention Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder

The attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder ( ADHD ) belongs to the group of behavioral and emotional disorders with onset in childhood and adolescence . It manifests itself through problems with attention , impulsivity, and self-regulation ; sometimes there is also strong physical restlessness ( hyperactivity ).

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| F90.– | Hyperkinetic disorders |

| F90.0 | Simple activity and attention disorder |

| F90.1 | Hyperkinetic conduct disorder |

| F90.8 | Other hyperkinetic disorders |

| F90.9 | Hyperkinetic disorder, unspecified |

| F98.– | Other behavioral and emotional disorders that begin in childhood and adolescence |

| F98.8 | Other specified behavioral and emotional disorders that begin in childhood and adolescence - attention disorder without hyperactivity |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The disorder used to be seen as a pure behavioral problem, whereas today it is increasingly understood as a complex developmental delay of the self-management system in the brain . ADHD can also be seen as extreme behavior that shows a smooth transition to normality. The abnormalities must be very pronounced for old age and, in most situations, have been present since childhood. Symptoms alone, however, have no disease value: an ADHD diagnosis is only justified if they also severely impair lifestyle or lead to recognizable suffering.

The worldwide incidence of ADHD among children and adolescents is estimated at around 5.3%. Today it is the most common psychiatric illness in children and adolescents. Boys are diagnosed noticeably more often than girls. Follow-up studies have shown that 40 to 80% of children diagnosed with the disorder persist into adolescence . Finally, in adulthood, impairing ADHD symptoms are still detectable in at least one third of cases (see ADHD in adults ).

As a neurobiological disorder, ADHD has largely genetic causes. Depending on the person, however, it can have very different consequences, since the individual course is also influenced by environmental factors . In most cases, those affected and their relatives are under considerable pressure: Failures in school or at work, unplanned early pregnancies, drug consumption and the development of other mental disorders have often been observed. There is also a significantly increased risk of suicides, accidents and unintentional injuries. However, these general risks do not have to be relevant in every individual case. The treatment therefore depends on the severity, the level of suffering , the respective symptoms and problems as well as the age of the person concerned.

Research into the elucidation of causes and therapy improvement has been going on for decades. Today (as of 2018) the advantages of an individually adapted treatment have been clarified; as well as the disadvantages of neglected or incorrect treatment . Signs of long-term recovery from altered brain functions through appropriate (pharmacological) treatment have already been demonstrated many times with modern imaging methods .

Names and abbreviations

In addition to ADHD, there are many alternative names and abbreviations. Some of them describe consistent clinical pictures (e.g. hyperkinetic disorder (HKS) or attention deficit / hyperactivity syndrome ), while others sometimes refer to special forms. Internationally today, ADHD is usually referred to as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or attention deficit / hyperactivity disorder (AD / HD).

The term Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) is still widely used in colloquial terms - although it is no longer used in the more recent specialist literature . The abbreviations ADS and AD (H) S are used particularly by those affected with predominantly attention deficit disorder without pronounced hyperactivity. It is intended to express that hyperactivity is not always a symptom. The terms minimal cerebral dysfunction (MCD) or hyperkinetic reaction of childhood are out of date ; the diagnosis psycho-organic syndrome (POS) is only used in Switzerland.

Spread and course

The probability of being affected by ADHD for a limited time or permanently in the course of life ( lifetime prevalence ) was estimated at around 7% in 2014, according to the analysis of dozen extensive studies. There was no evidence to support the assumption that there has been an increase in diagnoses in recent decades. Also, no methodological differences based on time or geography could be assumed for the period from 1985 to 2012. All such apparent differences appeared plausible due to methodological differences in the data acquisition.

The Robert Koch Institute determined ADHD prevalence by age group by evaluating data from the Child and Adolescent Health Survey (KiGGS). The data set comprised 14,836 girls and boys aged 3 to 17 years. In the three-year study period (2003–2006), a total of 4.8% (7.9% boys; 1.8% girls) had ADHD diagnosed by a doctor or psychologist. Another 4.9% (6.4% boys; 3.6% girls) of the participants were considered suspected ADHD cases, as their reported behavior on the inattentiveness / hyperactivity scale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) had a score of ≥7 . The following table shows how often ADHD is diagnosed in 3–17 year olds (broken down by age group and gender).

| Preschool age (3-6 years) | Primary school age (7-10 years) | Late childhood (11-13 years) | Youth (14-17 years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD frequency | 1.5% | 5.3% | 7.1% | 5.6% |

| Boys | 2.4% | 8.7% | 11.3% | 9.4% |

| girl | 0.6% | 1.9% | 3.0% | 1.8% |

The general trend is visible that the frequency of diagnosis increases sharply from preschool age through primary school age to late childhood. There it reaches a climax and decreases again in adolescence. The male sex predominates significantly - at any given time, 4-5 times more boys are diagnosed than girls. According to KiGGS, ADHD persists in 30–50% of those affected as children with certain changes in adulthood.

In the course of individual development, the symptoms usually change: Affected preschool children are usually dominated by hyperactive-impulsive behavior without a visible disturbance in attention. With increasing age, however, the attention deficits become more and more noticeable and come to the fore, while motor restlessness decreases. Attention disorder without pronounced hyperactivity is most common among adults.

Diagnostics and classification

A usable and valid ADHD diagnosis can only be made by specialists or psychologists with sufficient specialist knowledge. The basis for this are the guidelines on ADHD of the AWMF and other medical societies (see under literature ). With regard to the diagnostic conditions, these guidelines are largely based on the definitions of two classification systems:

- the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) by the WHO

- of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) of the APA .

The ADHD symptoms and characteristics are dimensionally distributed in the population and do not in themselves constitute signs of disease. In efforts to diagnose ADHD clearly and categorically, these common symptoms are therefore far less helpful than their deleterious effects on lifestyle. For diagnostics, it is therefore crucial whether there is also limited functionality, quality of life or participation in everyday life. If the abnormalities only occur in one area of life, this can be an important indicator of another mental disorder.

In summary, it can be said that ADHD is ultimately a clinical diagnosis. A specific diagnostic test does not yet exist.

Classification according to ICD

According to ICD-10

In the ICD-10, the clinical picture is listed under the main category of hyperkinetic disorders (F90). Increased importance is attached to excluding other diagnoses (see differential diagnosis ). A more precise specification can be made by putting a number after a period. The following encryptions are currently possible:

- Simple activity and attention disorder (F90.0) - criteria for inattentiveness, impulsivity, and hyperactivity are met.

- Hyperkinetic conduct disorder (F90.1) - criteria of F90.0 and conduct disorder (F91) are met at the same time.

- Other hyperkinetic disorders (F90.8) - need not meet all criteria of F90.0.

- Hyperkinetic disorder, unspecified (F90.9) - should only be used if there is any uncertainty between F90.0 and F90.1.

For the diagnosis of ADHD as a hyperkinetic disorder according to F90.0, F90.1 or F90.9, “impaired attention, overactivity and impulsivity are necessary”.

An attention disorder without hyperactivity (corresponding to the predominantly inattentive subtype in the DSM ) can not be coded in the hyperkinetic disorder category (F90). For this, the remaining category of other specified behavioral and emotional disorders with onset in childhood and adolescence - incl .: attention disorder without hyperactivity (F98.8) must be used.

The US-American version ICD-10 Clinical Modification differs in the definition of the codes F90.0 (there: predominantly inattentive type) and F90.1 (predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type) and includes a further code F90.2 (mixed type) .

Coding of the predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type in the ICD scheme

A hyperkinetic disorder in which the criteria for inattentiveness are not fully met can be coded under F90.1 or F90.8.

Other variants

Many experts also describe subclinical variants, other special forms or disorders that do not occur at home but in school. However, like the predominantly inattentive type, these were not included under the main classification F90.– of the ICD-10 in 1992, "because the empirical predictive validation is still insufficient". These can also be classified under the ICD number F98.8 or under F90.8.

According to ICD-11

The 11th revision of the ICD ( ICD-11 ) published in 2018 now lists ADHD under 6A05 (Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) , which replaces the hyperkinetic disorders category .

According to DSM-5

According to DSM-5 (2013), people with ADHD must show at least one of the following two behavioral patterns:

- Inattention (inattention)

- Hyperactivity-impulsivity (hyperactivity-impulsivity)

Nine possible symptoms are given for both behavior patterns:

inattention

- often fails to pay close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, work or other activities,

- often has difficulty maintaining attention while doing tasks or playing games

- often doesn't seem to listen when spoken to directly,

- often does not follow instructions completely and often fails to complete schoolwork, chores or duties in the workplace (loss of concentration; distraction),

- often has difficulties organizing tasks and activities (e.g. messy, haphazardly disorganized work; does not meet deadlines and deadlines),

- often avoids, dislikes or is reluctant to do tasks that require prolonged mental effort (e.g. participation in class; filling out forms),

- often loses items that are necessary for tasks or activities (e.g. school supplies, pens, books, tools, wallet, keys, paperwork, glasses, mobile phone),

- is often easily distracted by external stimuli or irrelevant thoughts (stimulus openness),

- is often forgetful about daily activities (e.g. running errands, paying bills, keeping appointments).

Hyperactivity-impulsivity

- often jumps with hands or feet, beats the beat with them or writhes on the seat,

- often leaves the seat in situations where it is expected to remain seated

- often runs around or climbs in unsuitable situations (in adolescents or adults, a subjective feeling of restlessness is sufficient),

- is often unable to play calmly or participate in leisure activities calmly,

- is often “on the go” or acts “as if driven” (e.g. can no longer stay quietly in one place or feels very uncomfortable, e.g. in restaurants),

- often talks too much,

- often bursts out with an answer before the question is finished or ends other people's sentences,

- struggles to wait for his / her turn (e.g. while waiting in line),

- Frequently interrupts or disturbs others (e.g. bursts into conversation, games, or other activities; uses other people's things without asking; in adults: interrupts or takes over other people's activities).

additional conditions

An ADHD diagnosis is only possible if there are a sufficient number of specific and all general conditions (see table).

| Necessary special conditions | Necessary general conditions |

|---|---|

|

|

Severity

The current severity can now also be specified:

- Mild : There are few or no symptoms in addition to those necessary to establish a diagnosis, and the symptoms result in no more than minor impairments in social, academic, or professional functioning.

- Medium : The severity of the symptoms and the functional impairment lies between "mild" and "severe".

- Severe : The number of symptoms clearly exceeds the number required for diagnosis or several symptoms are particularly pronounced or the symptoms significantly impair social, school or professional functioning

Methods of diagnosis

A diagnosis should be based on information from different sources, since a single test or just one living environment cannot cover the complete differential diagnosis. In addition to questioning the child concerned, the parents or educators and teachers, the basic diagnosis also includes a thorough psychological test diagnosis, a neurological examination and behavioral observation.

A test psychological examination should last at least one to two hours in order to ensure a thorough behavioral observation in the test situation. Concentration tests alone (such as Brickenkamp's d2 test or Esser's BP concentration test ) alone are not sufficient to make a statement about a child's ability to concentrate in everyday life. In addition, a number of other tests, e.g. B. the thinking skills (" intelligence test "). The subtests can provide information about the strengths and weaknesses and help in making a diagnosis.

In clinics or medical practices, an additional MRI is rarely performed for reasons of cost . An EEG is done to find out whether there are other diseases. In this way, especially in the case of medication, it should be excluded that epilepsy is present.

Neuropsychology

Some quantifiable characteristics for diagnosing children with ADHD are currently being discussed. Some of these can also be measured using neuropsychological test procedures . The focus of this discussion is currently on the following features:

- Limitation of working memory

- Impairment of executive functions (e.g. lack of inhibition control or ability to plan)

- Aversion to postponing rewards

- motor overactivity

- Regulation of activation and alertness , disruptions in time processing

- increased inter- and intra-individual variability in response time

- dysfunctional regulation of the willingness to make efforts with regard to goal-related behavior (short-term or distant goals)

Differential diagnostics

Mental disorders that are sometimes confused with ADHD include, in particular, chronic depressive moods ( dysthymia ), permanent and debilitating mood swings ( cyclothymia or bipolar disorder ), and borderline personality disorder .

Differentiating it from autism spectrum disorders can be difficult if the attention disorder occurs without impulsivity and hyperactivity and there are also social deficits caused by it. In Asperger's Syndrome, however , the impairments in social and emotional exchange, the special interests and the detail-oriented style of perception are more pronounced. Conversely, severe disorganization with erratic thinking and action can often be observed in ADHD, which is not typical for autism.

Other medical conditions that can cause ADHD-like symptoms and which must also be ruled out before an ADHD diagnosis can be made are: overactive thyroid gland ( hyperthyroidism ), epilepsy , lead poisoning , hearing loss , liver diseases , respiratory arrest during sleep ( sleep apnea syndrome ) , Drug interactions and consequences of traumatic brain injury .

Concomitant and secondary illnesses

A concomitant disease ( comorbidity ) is an additional existing, diagnostically definable clinical picture. In the case of conspicuous behavior (as in ADHD), further behavioral disorders can initially be considered as possible concomitant diseases. These can either be causally related to the underlying disease (ADHD) or be a secondary disease . However, they can also co-exist without an obvious connection.

Mental disorders, which statistically occur particularly frequently together with ADHD, are in the foreground in the diagnosis. Approx. 75% of the ADHD sufferers have another mental disorder, 60% have several mental comorbidities.

Conduct disorders

If a conduct disorder occurs in addition to ADHD, the combination of the two is diagnosed as a separate subtype in the ICD-10 as Hyperkinetic Conduct Disorder (F90.1): Hyperkinetic disorder associated with conduct disorder .

The category disorders of social behavior also exists as a separate category (F91), i.e. separate from ADHD. This neighboring category can, however, also be used indirectly in the ADHD diagnosis, as it divides the disorders of social behavior into different subcategories (F91.0 to F91.9). In this way, the particular personal and social circumstances of the child or young person can be better taken into account and a more accurate diagnosis can be made.

Partial service disruptions

Partial service disruptions such as B. reading and spelling disorders were found in up to 45% (mean of various studies) of those affected by ADHD. The subcategories are listed under specific developmental disorders of school skills (F.81) .

depression

Depression is at least five times more common in adolescents with ADHD than in adolescents without ADHD. If depression only sets in several years after the onset of ADHD, it is assumed that it is at least partially a result of the particular stresses and strains of ADHD. These observations highlight the urgency of diagnosing and treating ADHD as early and carefully as possible. If depression has already occurred, careful and adapted multimodal treatment can usually achieve good effectiveness against both ADHD and depression at the same time.

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety disorders occurred in many studies in up to 25% of people with ADHD. There was evidence to suggest that they reduce impulsiveness but further affect working memory. Conversely, ADHD may make the anxiety disorder less phobic. It was also found that the level of anxiety was related to the severity of the SCT symptoms.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Obsessive-compulsive disorder is about three times as common in people with ADHD (approx. 8%) than in those who are not affected (2-3%).

sleep disorders

Sleep disorders of various kinds (such as delayed sleep phase syndrome ) are a frequent accompanying problem with ADHD. They require a very careful diagnosis and appropriate, individually tailored treatment.

Subtypes

The DSM-IV from 1994 still contained a division of ADHD into three different subtypes :

- the predominantly inattentive type ,

- the predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type

- the mixed type

However, this subtyping led to a very large heterogeneity within the individual groups and did not seem useful for treatment planning. It was also shown that the individual subtype was not very stable over time and often changed over time. So developed z. B. Children with a hyperactive-impulsive type become adolescents with a mixed type and eventually grew into adults with a purely inattentive type. It has therefore been questioned whether these are really different types of ADHD or rather temporary development phases.

Because of this lack of scientific confirmation of the subtypes, the DSM-5 only speaks of different appearances (presentations) . A distinction is now made between the predominantly inattentive appearance , the predominantly hyperactive-impulsive appearance and the mixed appearance . This linguistic weakening is intended to emphasize that it is an assessment of an instantaneous state that can change over time.

All three appearances represent a combination of the two behavioral patterns (inattentiveness and hyperactivity-impulsivity) with different weightings. The appearances "predominantly inattentive or predominantly hyperactive-impulsive" are characterized by the fact that the required number of individual symptoms is achieved for only one of the two behavioral patterns got to.

The ICD-11 , released in June 2018, contains the same three appearances as the DSM-5.

Timing and coordination of behavior

An overview study pointed out that ADHD patients in three main areas of timing and coordination of behavior ( timing may be conspicuously impaired), namely in the context of motor control in the perception of time and the perspectives for the future. The difficulties that most frequently arise in ADHD concern sensorimotor synchronization, differentiation of time intervals, reproduction of time intervals and long-term or short-term orientation. The timing deficits remain even if ADHD-typical deficiencies in executive functions are statistically taken into account as influencing factors. This is interpreted to mean that cognitive deficits in the area of timing behavior are an independent characteristic of ADHD.

Causes and Risk Factors

In the past, mostly psychosocial and educational environmental factors were assumed to be the cause of ADHD. Upbringing errors, parenting problems, neglect and early childhood trauma were the focus of possible reasons for and influences on the disorder. Meanwhile (as of 2016) one assumes ideas that take into account both biological factors and environmental influences.

Neurobiology

brain

A reduction in brain volume and functional deficits have repeatedly been found in a large number of core areas. In recent years (as of January 2016), research has focused in particular on the changes in large-scale neural networks that correspond to the observed disorders of the patients and the observed sub-functions in the brain. Research on the development of the deviations during the development of the brain in different ages is still (as of January 2016) in an early, initial phase.

Neurons

The pathways of the nerve fibers in the brain ( white matter ) show anatomical and functional deviations in a group comparison between those affected by ADHD and comparison persons . Since 2014 it has also been found that some of these deviations are specific to certain partial symptoms, such as attention deficit or hyperactivity. However, it is not expected that these new diagnostic methods will be used for diagnosis in the foreseeable future (as of January 2016), since the differences in brains from person to person are so great that significant deviations can only be determined between groups of people - but not among individuals.

Signal transmission

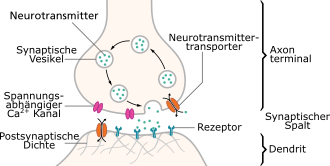

The transmission of signals between nerve cells by biochemical messenger substances ( neurotransmitters ) is impaired in ADHD. This is particularly true for dopamine transmission in the centers of reward and motivation, namely in the nucleus accumbens , nucleus caudatus and in certain core areas of the midbrain . The long-standing assumption that signal transmissions are also impaired by the neurotransmitter norepinephrine has been strongly supported by the effects of newer, very specific drugs such as guanfacine , but has not yet been conclusively clarified (as of January 2016).

Since 2014 there has been direct evidence that in ADHD, specific parts of the signal transmission by the neurotransmitter glutamate only take place in a reduced function, especially in the striatum , a brain region with central importance for motivation, emotion, cognition and movement behavior. Several genetic studies after 2000 found abnormalities in the genes that code for elements of glutamatergic signaling in people with ADHD and their families . Finally, glutamate has even been viewed by some researchers as a possible key to understanding ADHD, especially because of its close coupling with the aforementioned dopamine systems. Corresponding glutamate sub-functions were then detected relatively quickly by imaging procedures of the CNS .

Paradoxical reactions to chemical substances

Another sign of the structurally changed signal processing in the central nervous system in this group of people is the strikingly frequent paradoxical reactions (approx. 10–20% of patients). These are unexpected reactions in the opposite direction as with a normal effect, or otherwise very different reactions. These are reactions to neuroactive substances such as local anesthesia at the dentist, sedatives , caffeine , antihistamines , weaker neuroleptics and central and peripheral pain relievers . Since the causes of paradoxical reactions are at least partly genetic, it can be useful in critical situations, for example before operations, to ask whether such abnormalities may also exist in family members.

genetics

Heredity

Based on family and twin studies, the heredity for the risk of having ADHD as a child is estimated to be 70 to 80%. The heritability for the risk of being affected as an adult could not yet be reliably estimated (as of January 2016), as the methodological difficulties in recording are greater here. The tendency, however, indicates that the heredity of the risk is just as high here as it is for children.

Genes

There is agreement on the necessity of several genetic deviations, since individual genes have very special influences and none of them alone can cause such a diverse behavioral deviation as in ADHD. It is believed that at least 14 to 15 genes are important for the development of ADHD. The genetic characteristics influence the neurophysiology and chemistry in specific control loops of the brain, e.g. B. between the frontal lobe and striatum (see striato-frontal dysfunction ). Even if there are no outward changes at first, there may be a basic predisposition that can later lead to disorders such as ADHD due to further circumstances.

The genetic abnormalities that have so far been associated with ADHD are - each considered individually - not specific to ADHD. In combination with certain variants in other genes, they can also trigger other related or unrelated diseases. From this it follows that the previous knowledge (as of January 2016) does not allow predictions by genetic tests in an individual. In making a diagnosis, nothing more can be done in this regard than to consider any occurrence of ADHD in close relatives. However, this is strongly recommended for timely diagnosis and treatment.

Pollutants

Tobacco smoke

A causal relationship between an increased risk of ADHD through tobacco smoking during pregnancy (and passive smoking during childhood) has not yet been proven. There are methodological reasons for this: there can simply be too many, non-excludable, third factors involved. However, a high probability of an increased risk is beyond dispute.

lead

There is a statistical relationship between exposure to the heavy metal lead and the occurrence of ADHD, but no causal relationship has yet been proven.

PCB

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB), which are now banned worldwide, but are still widespread almost everywhere as contaminated sites, increase the risk of ADHD.

social environment

Stressful family relationships are more common in families with a child with ADHD. However, it is not possible to determine whether the family situation had an impact on the triggering or the severity of ADHD. Conversely, ADHD can also induce or exacerbate stressful family relationships, and it has been shown that diagnosis and treatment lead to a decrease in hostilities within the family.

General risk factors

Pregnancy and childbirth complications, a reduced birth weight, infections, various pollutants and diseases or injuries to the central nervous system are considered risk factors; also exposure to alcohol during pregnancy .

Need for treatment

ADHD can be roughly divided into three degrees of severity (see degrees of severity in DSM-5 ):

- In a lightly affected person, the symptoms are not so pronounced that they require treatment. She is more creative, less impulsive, and cannot concentrate as well as other people. On the other hand, she is much more aware of peripheral details. Nevertheless, it is important to inform the person concerned and their environment about ADHD at an early stage and to provide psychosocial support. This has a positive influence on the development of those affected and the problematic symptoms can be weakened.

- Moderately severely affected people need treatment and, in addition to ADHD, increasingly suffer from secondary diseases (comorbidities). However, they do not develop any conduct disorder or other social abnormalities. Under certain circumstances they take up a job for which they are mentally clearly overqualified. Without treatment, failure in school, work and personal life, as well as suicide attempts, are more likely.

- Severely affected people have disturbed social behavior and a greatly increased risk of developing addictive behavior or slipping into criminality . Without treatment, they are difficult to (re-) socialize .

With comprehensive preventive care and informing the people around you about the disorder, it may be possible to achieve that the individual symptoms are less pronounced and that those who were originally more severely affected fall into a weaker category. It should be noted, however, that the degree of severity is mainly neurobiological and can only be influenced within the framework of neuronal plasticity (adaptability) of the human brain. Meanwhile, the first imaging studies indicate that the most common medication with stimulants (primarily methylphenidate, see below) seems to be able to change the structure and function of the brain towards normalization. However, it is currently not yet clear how strong and relevant the relationship is between the measured structural and functional long-term changes in the brain and specific behavioral parameters of ADHD symptoms.

Importance of personal resources of those affected

In addition to the known problematic symptoms, people with ADHD are sometimes ascribed specific strengths and positive characteristics in the literature. These were listed by Bernd Hesslinger, for example, and compared with the deficient characteristics of the symptoms. Psychotherapy tries to promote the individual strengths of those affected.

Some of the positive characteristics that are more often ascribed to people with ADHD include:

- Hypersensitivity , which can be expressed in a special empathy and a pronounced sense of justice,

- Openness to stimuli, which often allows you to grasp changes quickly,

- Enthusiasm that can be expressed in particular creativity and openness,

- Impulsiveness , which, correctly dosed, makes you interesting interlocutors,

- the hyper-focus , a flow -like condition that can lead to long, persevering and concentrated work on specific topics. (But also to daydreams, to neglect of external reality, to disruptive repetitions and inflexible clinging to unimportant things).

- Hyperactivity can also lead to a particular enthusiasm for competitive sports.

Such characteristics are, however, personality traits that are widespread in the population and that - detached from the context of a psychiatric disorder - are also reflected, for example, in the dimensions of the empirically proven five-factor model . Having ADHD is therefore not an essential prerequisite for developing these special skills. The connection established between specific strengths and the presence of ADHD is therefore also sharply criticized: Russell Barkley described the connections as “romanticizing a disorder to be taken seriously” and “ cherry-picking ”.

The individual strengths and potentials of ADHD sufferers can be masked depending on the severity of the disorder and its accompanying illnesses. An important sub-goal of multimodal therapy is therefore to identify and promote the individual personality resources available as well as the development and establishment of advantageous coping styles and habits (which can sometimes only be achieved through medication) .

treatment

The aim of treatment is to exploit the potential that varies from person to person, to develop social skills and to treat any accompanying disorders. The treatment should be multimodal , i.e. several treatment steps should be carried out in parallel (e.g. psychotherapy , psychosocial interventions , coaching, pharmacotherapy). The choice of treatment depends on the severity of the disorder. Therapy can usually be carried out on an outpatient basis.

Partial inpatient therapy (in a day group , a day clinic or residential home ) or inpatient therapy is necessary especially if the symptoms are particularly severe. This is especially true in the case of severe comorbid disorders (such as disorder of social behavior or partial performance weaknesses such as dyslexia or dyscalculia ), if there are insufficient resources in kindergarten or school or particularly unfavorable psychosocial conditions. Outpatient therapy that is not sufficiently successful can be continued as an inpatient or partial inpatient in a child and adolescent psychiatric facility . There, the relationships within the family can be stabilized again. For this it is mostly necessary to include the caregivers in the treatment.

Multimodal approach

The multimodal treatment can contain the following aids, which should always be tailored to the individual case. They can be used in an outpatient as well as a fully or partially inpatient setting:

- Education and counseling ( psychoeducation ) for parents, children / young people and their educators or class teachers.

- Parent training (also in groups) and help in the family (including family therapy ) to reduce possible stress in the family.

- Help in kindergarten and school (including changing groups) to reduce possible stress. School psychologists can provide special support for the child or young person as well as a change of school.

- Pharmacotherapy to support brain functions with the aim of reducing inattentiveness, impulsiveness and overactivity in school (kindergarten), family or other environments, see medication

- Cognitive therapy for children or adolescents (from school age) to reduce impulsive and unorganized task solutions ( self- instruction training) or to guide changes in behavior in the event of problems ( self-management ), see behavioral therapy .

- Learning therapy for an accompanying partial performance disorder such as dyslexia or dyscalculia .

- Recent studies suggest a positive influence of physical activity. In ADHD patients, this has a beneficial effect on behavior and the ability to learn.

- The treatment of any accompanying diseases (see: Concomitant and secondary diseases ) should be carried out as part of a specially adapted overall treatment .

information

In-depth and comprehensive information for all parties involved about ADHD is an essential part of any therapy. Concerned should have the type of disorder (ADHD is no mental illness , no nonsense and no laziness ), informed the signs (symptoms), the potential difficulties in everyday life and the available treatment options.

In addition to the medical-psychological discussion, there is information material for parents as well as for affected children and adults. In their design, these often take the type of disturbance into account (i.e. little continuous text, many drawings, etc., and since the 2000s also instructive videos, increasingly on the Internet, whereby the seriousness and interest guidance of the websites must be assessed critically).

medication

Medication is indicated in many cases for the moderately and severely affected. The aim of this treatment is to reduce the core symptoms, to improve the ability to concentrate and self-control and to reduce the suffering and everyday limitations of those affected. Studies suggest that treatment with individually tailored drugs can reduce symptoms much more effectively than psychotherapy alone. In some cases this creates the prerequisites for further therapeutic work. For the drug treatment of ADHD, stimulants are most often used, which increase the signal transmission through the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain. These include methylphenidate and amphetamine , which have been used since around the mid-1950s. About 80% of those affected respond to it.

The efficacy of methylphenidate has also been proven in those affected with a predominantly inattentive appearance (according to the DSM classification ). It's a little weaker here. If there is an effect (the majority of cases), a lower dose can be used for this expression in order to achieve the desired effect.

Methylphenidate

Methylphenidate inhibits the function of transporters for the neurotransmitters dopamine and noradrenaline . These transporters are located in the cell membrane of the signaling ( presynaptic ) nerve cell. The signaling takes place through the release of messenger substances into the synaptic gap to excite the receiving nerve cell. In the course of the distributions, there is a constant rapid resumption ( recycling ) of the transmitter back into the signaling cell. As a result of the reuptake inhibition by methylphenidate, the concentration of the neurotransmitters in the synaptic gap is increased and the signal transmission between the nerve cells is thus strengthened for a longer period of time. The effect of methylphenidate is therefore a signal amplification.

Methylphenidate has been used since 1959 and has been extensively studied in the context of its short-term effects. The effects of long-term use have not yet been fully recorded, but it is becoming clear that they are usually associated with a permanent normalization of the affected brain structures - both in anatomy and function. Nevertheless, the active ingredient should only be prescribed after careful medical examination ( indication ) and as part of an overall treatment concept.

In Germany, methylphenidate is sold under the trade names Ritalin , Medikinet , Concerta , Equasym and many others, because the product protection has expired (see generic ). All of these preparations contain the same active ingredient, but there are differences such as: B. with fillers and additives. The best-known preparation Ritalin , for example, has a different duration of action than Concerta or Medikinet retard , because with retarded drugs the active ingredient is released into the body with a time delay and continuously throughout the day. This can have different effects depending on the patient; Effect and side effects should therefore be checked in order to choose another preparation if necessary.

The adjustment to the drug is done by means of dose titration , in which the doctor first determines the necessary individual dose (usually between 5 and 20 mg MPH-HCl) and the individual duration of action (approx. 3 to 5 hours). Using observation sheets, parents, teachers or therapists , if necessary, assess the effect and then adjust the dosage. The necessary dose varies individually. The maximum dose is 1 mg per kg of body weight, but not more than 60 mg for children and 92.5 mg (MPH-HCl, corresponds to 80 mg / day MPH) for adults per day. It should only be exceeded in individual cases and according to the strictest indication. It should be noted here that there is a slight delay in growth in height and weight - on a statistical mean and possibly not due to the medication, but rather to ADHD itself, which, however, is caught up and therefore does not change the final values of growth. Failure to respond to methylphenidate can mean different things: the patient may be a non-responder to whom methylphenidate is not working, or the diagnosis has not been made correctly.

Due to the short effective time, after the end check (rebound) occur and lead to a marked increase in initial symptoms. This is explained as follows: the facilitated self-regulation by the medicinal substance suddenly disappears, which initially leads to difficulties in adapting to the previous state without medication. This effect can occur especially in children at the beginning of therapy as well as if they are taken irregularly; it usually normalizes in the course of therapy. It is recommended to largely reduce the demands placed on the child during the limited time of the rebound. It is also possible to switch to a different dosage regimen or drug. Too high a dose of methylphenidate also leads to a feeling of restlessness or inner tension, rarely also to a significant decrease in activity with fatigue and a reduced drive. These phenomena only last for the duration of the action and then recede. They can be corrected by finding the appropriate dose.

Careful proper medication of methylphenidate usually has no harmful adverse effects in people with ADHD. Side effects are dose-dependent, usually avoidable and transient at the start of therapy. Common side effects include decreased appetite or stomach upset, headache and, less commonly, tic disorders .

ADHD patients have an increased risk of addiction , depending on the severity . In this context, the consumption of stimulants was discussed as a potential risk for later development of addiction. In two meta-analyzes of a large number of individual studies, however, it was shown that the administration of methylphenidate does not increase the risk of later addictive behavior (analysis A) but, in contrast, even reduces it (analysis B). There is only a risk of tolerance and dependency development due to methylphenidate in the case of deliberate misuse or extremely high doses.

According to German guidelines, treatment with methylphenidate is also a therapeutic option for adults . On April 14, 2011, the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices approved for the first time an extension of the indication to adults for the treatment of a disease that has persisted since childhood.

Currently (as of January 2017) two methylphenidate- containing drugs ( Medikinet adult since April 2011 and Ritalin adult since May 2014 ) have been approved for adults. In Switzerland , methylphenidate is also paid for by health insurance for adults.

amphetamine

Treatment with amphetamine may be promising for patients who do not respond sufficiently well to methylphenidate . In Germany, the preparations Attentin (dexamphetamine hemisulfate) and Elvanse ( lisdexamfetamine ) are approved for children and adolescents from 6 years of age. These substances are considered to be just as safe and tolerable as methylphenidate.

In contrast to methylphenidate (MPH), amphetamine not only acts as a pure reuptake inhibitor, but primarily causes an increased release of norepinephrine and dopamine. This is accomplished , among other things, by reversing the working direction of transporters for noradrenaline (NET) and dopamine transporters (DAT). In contrast to the principle of reuptake inhibition (such as with methylphenidate), the transmitter level is increased independently of the activity of the nerve cell. Unlike MPH , amphetamine also inhibits monoamine oxidase (MAO) and binds strongly to TAAR1 (trace amine-associated receptor 1) . This trace amine receptor presumably strongly modulates the signal transmission of monoamines in the brain .

In Germany, amphetamines can also be prepared in pharmacies as an individual recipe. The New Formulation Form (NRF) therefore contains entries on amphetamine sulphate (juice according to NRF 22.4 or capsules according to NRF 22.5) and dexamphetamine sulphate (2.5% drops according to NRF 22.9).

Corresponding magistral formulas can also be prescribed in Switzerland or imported from abroad. Elvanse is also admitted there.

In Austria, all public pharmacies are permitted to dispense such preparations (see legal information on amphetamines ). It requires the prescription on a narcotic drug prescription. Also methamphetamine is be prescribed in Austria .

Both amphetamine and methamphetamine drugs are available in the United States .

Guanfacine

If methylphenidate or amphetamine preparations do not respond adequately or otherwise prove to be unsuitable, the second line medication is the α2-receptor agonist guanfacine (trade name Intuniv ). In particular, it promotes signal transmission in the prefrontal cortex . In its effect on ADHD, it is superior to atomoxetine (see below). Guanfacine has been approved in the US since September 2009 and throughout the EU since September 2015.

Atomoxetine

Atomoxetine is a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (trade name Strattera). However, in contrast to stimulants, the onset of action can only be assessed after a few weeks. When starting use, the dose should be increased gradually up to the so-called effective dose , which is reached when the normally expected effect has occurred.

With regard to the treatment of children and adolescents, a Rote-Hand-Brief from the manufacturer has been available since September 2005, in which, however, a significantly increased risk of favoring or triggering aggressive behavior, suicidality and suicidal acts with atomoxetine compared to placebo in children is not in adults is informed. If you have suicidal thoughts while taking the drug, stop taking it. However, extensive subsequent studies showed that neither adolescents nor adults are at an increased risk of suicide.

Atomoxetine is slightly less effective than stimulants or guanfacine, but it is well documented.

In addition to its effects in ADHD, atomoxetine can also alleviate an accompanying tic disorder .

Combination therapy

Combination therapy is not uncommon for ADHD in adults. In a 2009 study, combination therapy was present in more than 20% of the treatment periods for all drugs. Combinations were different depending on the drug. They ranged from approximately 20% of treatment periods with atomoxetine up to 53% at α 2 adrenoceptor - agonist . The most common combination in absolute terms was bupropion with a long-term stimulant.

Patient characteristics with a statistically higher incidence of combination therapy included age over 24 years, recent visit to a psychiatrist, hyperactive component of ADHD, and comorbid depression.

Other substances

In addition to or as an alternative to stimulants, guanfacine or atomoxetine, other drugs are used, in particular antidepressants . Typical indications for this are depression , anxiety disorders, or obsessive-compulsive disorder that occurred as concomitant or secondary diseases. As the sole medication, however, these drugs are ineffective or have very little effect on ADHD symptoms, with the exception of bupropion, which has a small effect here.

Examples of antidepressants used are:

- Bupropion is a selective norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor. However, the effect of this substance on ADHD symptoms is small.

- Selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) such as venlafaxine and duloxetine , which inhibit the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine into the presynapse . However, to date (as of January 2016) there are no sufficient data on the effectiveness of any of the two substances in ADHD to justify a recommendation for these patients.

- Tricyclic antidepressants like desipramine , imipramine, or doxepin . Although signs of a short-term improvement in ADHD symptoms were found for desipramine, little reason for its use was seen because of the side effects (including an increase in blood pressure and pulse rate). No ADHD-specific data are available for the other two substances.

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) such as B. fluoxetine or sertraline , which inhibit the re-uptake of serotonin in the presynapse , are possible additional medications, especially if there are accompanying signs of depression.

Other medicines for which there are insufficient data for use in ADHD:

- Modafinil is a stimulant approved for the treatment of narcolepsy that can also be used off-label in ADHD therapy . Tests over weeks have shown positive results in ADHD, but there are no studies on long-term treatment, and no further reviews were published from 2006 to 2016.

- Metadoxin (known from alcohol detoxification) has proven to be a partially effective ADHD drug in some studies with adults, but only improvements in attention occurred and only in ADHD patients with disorders primarily in the area of attention. This special effect then occurred within 3-5 hours after a single application.

Local anesthetics for ADHD

In ADHD, there may be unexpected deviations in the effectiveness of local anesthetics. See Local Anesthesia (Dentistry) # Local Anesthesia for ADHD .

psychotherapy

Psychotherapeutic treatment methods can be a useful part of multimodal therapy.

Behavior therapy

The aim of behavioral therapy measures is that those affected acquire the appropriate skills to cope with the peculiarities and problems that ADHD brings with it. However, such therapy usually does not help much before the age of about eight.

In childhood, behavioral therapy programs are geared towards providing information on ADHD and suitable help for setting up rules and order in parenting training (e.g. exercises with a token system or response costs ; help with behavior in the event of problems). Further objectives can be improving self-control (e.g. through coaching , self-instruction training or self-management therapy ) and promoting the self-esteem of children and young people.

Therapy programs have been developed for treatment that are specifically geared towards the behavior and attention of the children concerned. Operant therapy programs have proven particularly effective here. Various materials and exercises are included in an attempt to encourage appropriate behavior and attention. They mostly use plans and try to teach children about attention and strategic action. The parents, who should support and observe the various therapeutic steps as much as possible, have an important task.

The effectiveness of behavior therapy in ADHD has been proven several times, both with and without a combination of drugs. When drugs were combined with behavior therapy, a lower dosage of the drug was sufficient.

Further support measures

With school problems

If the child needs special help in the pre-school area, a visit to the pre-school or early intervention can be useful.

In the case of children who suffer from ADHD, it must be carefully checked which type of school corresponds to their ability to perform. In doing so, it should be taken into account whether they are under or over-challenged at school. In the case of massive behavioral problems, it may also be necessary to attend an integrative class or special school to receive special educational aids. Attending a home school with special educational support can be useful if attending a regular or special school is no longer possible. Here there is the possibility of intensive pedagogical support in small groups.

Occupational therapy

ADHD is often associated with motor difficulties affecting both gross and fine motor skills. Remedy can be a here occupational therapy create. Furthermore, occupational therapy can provide help in coping with everyday problems. These include u. a. learning of compensatory strategies, appropriate social behavior, as well as parenting training and advice to support the child in everyday life.

Education aids

The child and youth welfare service offers interested parents as supportive measures help with upbringing , for example parenting advice , socio-educational family help , day groups or learning therapy. The aim is to use educational methods and special support to reduce the deficits that often exist in behavior and, moreover, to improve school performance.

Parents also have the option of applying for help they choose from the regional youth welfare office. According to Section 5 of Book VIII of the Social Code, parents have the right to wish and choose with regard to the type of help offered and the provider or consultant. As a rule, it is sufficient to submit an informal application for help with education.

Parent training

By improving the parenting skills of the parents, subsequent problems in the parent-child relationship and in social behavior should be prevented or reduced. Concepts based on learning theory, such as Triple P or Strong Parents - Strong Children , have proven to be helpful, all of which assume that the positive, socially acceptable behavior of the children is strengthened and include neuropsychological findings about the brain.

Support groups

Self-help groups exist mainly as groups for relatives (mostly parent groups) or for affected adults. The support experienced in self-help groups and the exchange with people with similar problems can have a positive influence on the self-image , the ability to act and the self-efficacy expectations of those affected or their relatives.

Coaching

In coaching, in addition to the therapist and the doctor, the person concerned has a confidant available who supports him, drafts goals with him and develops strategies together with him how these goals can be achieved in everyday life. In this way, the coach works closely with the person affected and helps him implement the resolutions made and strengthen self-management. In contrast to what doctors, psycho-therapists and occupational therapists offer, coaching is not a health insurance service and is usually self-financed. A new, voluntary form of coaching has developed through digital media, such as e-mails, exchanges and advice in self-help forums and online parent coaching.

Alternative treatments

Neurofeedback training

Neurofeedback is a special form of biofeedback training in which a training person receives computer-controlled optical or acoustic feedback about changes in the EEG signals in their brain. This is, for example, an airplane on the screen that gains altitude when certain EEG signals change in a certain direction. The computer measures the EEG signals and lets the plane rise (almost in real time) if the EEG signals are changed by a certain mental concentration and this change goes in the "correct" - previously programmed direction.

The basis is the experience that - statistically speaking - certain features of the EEG are present in ADHD. From this the assumption was derived by some that changing these deviations - in the direction of normalization - through neurofeedback could benefit the patient. However, one problem here is that the EEG deviations vary greatly from patient to patient and, for example, an ADHD diagnosis is not possible on the basis of EEG results. Another problem is that the abnormalities in the brain that cause the EEG signal abnormalities are usually virtually unknown. Research on this is still (as of January 2016) at a very modest beginning.

Research into the effectiveness of neurofeedback training in ADHD initially showed improvements in symptoms. However, when it was ruled out that the expectations influenced the results ( blind study ), the effect decreased markedly or disappeared completely. When the effects of real and simulated feedback ( placebo ) were finally compared, no difference was found. Neurofeedback was therefore only effective through its general promotion of concentration and self-control, similar to appropriate training in behavioral or occupational therapy.

Elimination diet

Studies by the ADHD Research Center in Eindhoven with the University of Rotterdam showed that some children with ADHD symptoms could be successful with the elimination diet . A study with 100 participants showed a significant ( significant ) reduction in ADHD symptoms in 64% of the children treated with it . At first they only ate rice, vegetables and meat. Everything else has been removed from the menu. After the symptoms of ADHD were reduced, additional food components were added to meals in order to identify possible triggers for ADHD. In fact, only a few foods triggered ADHD, which - according to the study - should be permanently avoided.

A 2014 overview study reported that there were small - but reliable - effects with this method. However, many questions are still open, in particular the clarification of whether there are certain signs in advance that a person affected could possibly expect an improvement from this method.

Nutrient therapy

The additional intake of omega-3 fatty acids has a moderate positive effect on the symptoms of ADHD according to a survey study from 2014. There is no evidence (as of January 2016) for the possible effectiveness of an additional intake of magnesium , zinc or iron .

Controversial approaches

On the basis of the results of examinations and double-blind studies to date, other approaches can be regarded as ineffective against ADHD or as having health concerns.

A Cochrane Systematic Review in 2007 reviewed the previously published homeopathic treatments for children with ADHD. According to the study, there was no significant effect on the core symptoms of inattentiveness, hyperactivity and impulsivity, nor on accompanying symptoms such as increased anxiety. There is no evidence of the effectiveness of homeopathy in treating ADHD. Further efficacy studies should be preceded by the development of the best possible records (protocols) of the treatments. Homeopathy is therefore unsuitable as a substitute for conventional therapy and medicine is only to be viewed as a possible supplement.

Treatment with so-called AFA algae is dangerous, as these blue-green algae generally contain toxins that can cause lasting damage to both the liver and the nervous system . The Canadian Ministry of Health felt compelled to issue a corresponding report and warn against ingestion - as did the Federal Institute for Consumer Health Protection and Veterinary Medicine.

history

The German doctor Melchior Adam Weikard first described in 1775 that lack of attention can also be a medical issue . In his extensive book The Philosophical Doctor he wrote under the chapter " Lack of attention, distraction, Attentio volubilis" (Latin for inconsistent tension / attention):

“An inattentive person will never achieve thorough knowledge. He hears, reads, and studies only upbeat; will make false judgments, and misunderstand the true value and the genuine quality of things, because he does not spend sufficient time and patience to understand a thing deeply, to investigate a thing individually or piece by piece with sufficient accuracy. Such people only half know everything; they notice or explain it only halfway. "

In 1798, the Scottish doctor Alexander Crichton (1763-1856), who had studied in several German cities and probably knew Weikard's book, described attention disorders in detail.

In 1845, the Frankfurt doctor Heinrich Hoffmann described some typical ADHD behaviors in Struwwelpeter (Fidget-Philipp, Hans Look-in-the-Air). Hoffmann, however, viewed these as parenting problems and not as a mental disorder.

In 1902 the English pediatrician George Frederic Still described the disorder scientifically for the first time. He suggested that it was not a bad upbringing or unfavorable environmental conditions, but a "clinical picture of a defect in moral control without general mental handicap and without physical illness". Some of these children had "a history of serious cerebral disorder in early childhood." The actual preoccupation with the neurobiological basis of ADHD did not begin until the 1970s.

In 1908 Alfred F. Tredgold published his work Mental Deficiency (Amentia) . It is considered (like the works of Still) as the foundation work for the modern history of ADHD.

In 1932 Franz Kramer and Hans Pollnow described the hyperkinetic disease .

In 1937, Charles Bradley first used amphetamines in children with behavioral problems, and their problems improved. In 1944 Leandro Panizzon developed methylphenidate , which has a similar effect ; In 1954 the substance was brought onto the market by Ciba (now Novartis ) under the name Ritalin .

In the 1960s and 1970s, the disorder was known as Minimal Cerebral Dysfunction (MCD).

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) has listed the clinical picture hyperkinetic disorder since 1978 .

In 1970, in her work at McGill University , Virginia Douglas placed the attention deficit at the center of the disorder instead of hyperactivity. Under their influence, the DSM-III changed the name of hyperkinetic reaction of childhood to attention deficit disorder (with or without hyperactivity, ADD) in 1980 .

In 1987 the disorder was renamed in the DSM-III-R again to attention deficit / hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and this term has been retained to this day.

After the increase in ADHD diagnoses and as a result of the increase in the number of stimulants prescribing drugs in the 1990s, there was a few non-specialists of the opinion that ADHD was an "invented disease". In reality, it is a variant of normal behavior, not a medically explainable problem and therefore not a matter for the doctor. The "invention" provided a welcome "explanation" for problems in the family and school, diverted attention from educational errors and provided the health sector with a gold mine. Therefore, some journalists felt compelled to take up this view and to spread the image of a possible medical scandal in a massively effective manner. In January 2002, 86 experts from the field published an International Consensus Declaration on ADHD in which these activities were condemned in an unusually harsh manner as unfounded and harmful for all those affected.

Controversy over ADHD

Risks of non-treatment or incorrect treatment

The current state of research on causes , treatment options and the lasting effects of untreated ADHD on life history are not always sufficiently known outside of specialist circles. As a result, misinformation and non-factual arguments on the subject remain widespread. Fears about the medication with methylphenidate (Ritalin) are often taken up and in particular the side effects and an alleged change in personality are emphasized. Parents who decide to take Ritalin are more or less directly accused of making it easy for themselves and refusing to bring up their children and harming their child. The resulting insecurity of the parents of the children concerned (and those affected themselves) often leads to the refusal of drug treatment or to a delayed and half-hearted drug therapy. Under certain circumstances, this also creates conflicts between the parents, who then also work against each other on this point.

ADHD children, for whom treatment without medication is obviously not sufficient to reduce the level of suffering to a tolerable level, are exposed to the increased risks of social isolation, emotional or physical abuse, school difficulties or dropouts, the development of additional disorders and increasing developmental delays exposed. Untreated sufferers also have a disproportionately high tendency to abuse alcohol and nicotine, generally increasingly to legal and illegal addictive substances (drugs as so-called dysfunctional self-medication), to risky sexual behavior and more frequent unplanned pregnancies and parenthood in teenage years. In road traffic, their increased risk of accidents is another problem.

Over- and underdiagnosis

Because of the sharp increase in ADHD diagnoses since the 1990s, there have been many concerns that the diagnosis will be made too often. However, a specific investigation of this question from 2007 could not find any evidence for this.

In the area of adults, an analysis of extensive data from 1976 to 2013 revealed in 2014 that many of those affected, who would have had great advantages from treatment, had received no diagnosis and therefore no treatment.

Commercial sites

In 2012, 61.03 million were defined daily doses ( Defined Daily Dose, DDD) drugs prescribed for drug treatment of ADHD - from 59.11 million DDD (in 2011) and 59.35 million DDD (2010). For comparison: In 2012, 1,323.86 million DDD antidepressants and 82.76 million DDD psychotropic drugs were prescribed for the treatment of dementia .

In particular, the prescriptions for methylphenidate increased from 1.3 million DDD in 1995 to 13.5 million DDD (2000) and 33 million DDD (2005) to 55 million DDD (2009). Since then the increase has leveled off and stabilized in the following years at 58 million DDD (2010 and 2011) and 60 million DDD (in 2012). In 2011, methylphenidate was prescribed to just under 336,000 people.

The stimulants methylphenidate and amphetamine, which are mainly used for drug treatment , are patent-free and free of additional protection certificates and are available as inexpensive generics or pharmacy formulations. Atomoxetine , on the other hand, is protected exclusively for Eli Lilly and Company until 2017 and is therefore more expensive than the corresponding medication with stimulants. According to information from the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians from December 2005, ADHD treatment in the maximum permissible atomoxetine dosage cost around 4.3 times as much as the corresponding therapy with non-delayed methylphenidate.

literature

Current guidelines

- ADHD in children, adolescents and adults . S3 guideline for all ages, AWMF , leading specialist societies: DGKJP , DGPPN and DGSPJ , May 2, 2018, valid until May 1, 2022 ( online ).

Introductions

- Russell A. Barkley (Ed.): The Great Parenting Guide to ADHD. Verlag Hans Huber, Bern 2010, ISBN 3-456-84916-8 .

- Hans-Christoph Steinhausen a. a. (Ed.): Handbook ADHD - Basics, Clinic, Therapy and Course . Kohlhammer 2009. ISBN 978-3-17-022744-6 .

- Manfred Döpfner , Tobias Banaschewski: Attention Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). In: Franz Petermann (Ed.): Textbook of clinical child psychology. 7., revised. and exp. Edition Hogrefe 2013, ISBN 978-3-8017-2447-4 , pp. 271-290.

- Kai G. Kahl u. a .: Practical manual ADHD: Diagnostics and therapy for all ages . 2., revised. and exp. Ed., Georg Thieme Verlag 2012, ISBN 3-13-156762-7 .

- Johanna Krause and Klaus-Henning Krause : ADHD in adulthood. Symptoms - differential diagnosis - therapy . 4th complete act. and exp. Edition. Schattauer, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-7945-2782-3 .

Psychoanalytic Theory

- Evelyn Heinemann, Hans Hopf: AD (H) S: Symptoms - Psychodynamics - Case Studies - Psychoanalytic Theory and Therapy. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart: 2006, ISBN 978-3170190825 .

history

- Russell A. Barkley: History of ADHD , in: ders. (Ed.): Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Fourth Edition. A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment . Guilford Publications, New York 2014, ISBN 1-4625-1785-4 , pp. 3-50, preview Google Books .

- Aribert Rothenberger , Klaus-Jürgen Neumärker: The history of science of ADHD - Kramer-Pollnow in the mirror of the times. Steinkopff, Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-7985-1552-2 .

For teachers

- Caterina Gawrilow, Lena Guderjahn u. a .: Trouble-free lessons despite ADHD: Train self-regulation with students - a teacher's manual. 2nd act. Edition. Ernst Reinhard Verlag 2018, ISBN 978-3-497-02823-8 .

Web links

- Ursula Peters: adhs attention deficit / hyperactivity syndrome ... what does that mean? (pdf, 1.1 MB) Federal Center for Health Education , November 2014 .

- Russell A. Barkley et al .: On Media Coverage of ADHD - Joint Statement by International Scholars. (pdf, 116 kB) German translation by Michael Townson. In: Central adhs network. September 2005, archived from the original on November 15, 2018 .

- Statement on "Attention Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)" - long version. (pdf; 1 MB; short version: pdf; 501 kB) German Medical Association , August 26, 2005.

- ADHD information portal of the central ADHD network of the University Hospital Cologne

- Swiss specialist association ADHD

Individual evidence

- ↑ Thomas Brown: ADHD in Children and Adults - A New View . Hogrefe, 2018, ISBN 978-3-456-85854-8 , see Introduction and Chapter 2 ( amazonaws.com [PDF]).

- ↑ Ludger Tebartz van Elst : Autism and ADHD: Between norm variant, personality disorder and neuropsychiatric illness . 1st edition. Kohlhammer Verlag, 2016, ISBN 978-3-17-028687-0 .

- ↑ Stephen V. Faraone et al .: Attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder . In: Nature Reviews Disease Primers . August 6, 2015, For prevalence see "Epidemiology", doi : 10.1038 / nrdp.2015.20 ( sebastiaandovis.com [PDF]).

- ^ Opinion on "Attention Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) ". Long version (PDF; 1.0 MB). German Medical Association , 2005, accessed on January 3, 2017 (p. 5: boys affected more often than girls; p. 36: persistence in adolescence; p. 42: persistence in adulthood.)

- ↑ More teenage pregnancies in ADHD. In: German Midwives Journal. 2017, accessed September 18, 2019 .

- ↑ ADHD in childhood reduces future prospects . Medscape Germany (2012). Long-term study by Klein et al.

- ↑ Editor Deutsches Ärzteblatt (2019): Increased risk of death in ADHD from suicides, accidents and other injuries. Deutscher Ärzteverlag, accessed on September 18, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d ADHD in children, adolescents and adults . S3 guidelines for all age groups (long version), May 2018. Chapter 1.2.1. (How should the individual treatment option be selected?), Chapter 2.5 and 2.13, p. 86f.

- ^ A b T.J. Spencer, A. Brown, LJ Seidman, EM Valera, N. Makris, A. Lomedico, SV Faraone, J. Biederman: Effect of psychostimulants on brain structure and function in ADHD: a qualitative literature review of magnetic resonance imaging -based neuroimaging studies. In: The Journal of clinical psychiatry. Volume 74, number 9, September 2013, pp. 902-917, doi: 10.4088 / JCP.12r08287 , PMID 24107764 , PMC 3801446 (free full text) (review).

- ^ A b c Johanna Krause and Klaus-Henning Krause : ADHD in adulthood. 4th complete act. and exp. Edition. Schattauer, 2014, ISBN 978-3-7945-2782-3 , pp. 5 f . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ GV Polanczyk, EC Willcutt, GA Salum, C. Kieling, LA Rohde: ADHD prevalence estimates across three Decades: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. In: International journal of epidemiology. Volume 43, number 2, April 2014, pp. 434-442, doi: 10.1093 / ije / dyt261 , PMID 24464188 (free full text) (review).

- ^ R. Goodman: The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note . In: Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines . 38, No. 5, July 1997, pp. 581-586. PMID 9255702 .

- ↑ Recognize - Assess - Act: On the Health of Children and Young People in Germany (2008). (PDF) Chapter 2.8 on ADHD, p. 57. (No longer available online.) Robert Koch Institute , archived from the original on December 11, 2013 ; accessed on February 24, 2014 . ISBN 978-3-89606-109-6 .

- ↑ R. Schlack et al. (2007): The prevalence of attention deficit / hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents in Germany. (PDF) (No longer available online.) Robert Koch Institute , archived from the original on February 24, 2014 ; accessed on February 24, 2014 .

- ↑ Erik G. Willcutt: The prevalence of DSM -IV attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review . In: Neurotherapeutics . 9, No. 3, July 2012, pp. 490-9. doi : 10.1007 / s13311-012-0135-8 . PMID 22976615 . PMC 3441936 (free full text).

- ^ Opinion on "Attention Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) ". Long version (PDF; 1.0 MB). German Medical Association , 2005. Chapter 3: Diagnostics and differential diagnostics of ADHD

- ↑ a b c d e Codes in the ICD-10 (according to DIMDI ):

- ↑ a b Hyperkinetic disorder in the ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders (WHO): Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines (p. 206ff) and Diagnostic criteria for research (p.188f)

- ^ ICD-10 Clinical Modification. Chapter 5, Section F90: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorders. (English: Wikisource).

- ↑ Hanna Christiansen, Bernd Röhrle (Chapter 14): Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy . Ed .: H.-U. Wittchen, J. Hoyer. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, 2011, ISBN 978-3-642-13017-5 , Chapter 14: Mental disorders of childhood and adolescence , p. 214 (Table 14.2).

- ↑ Helmut Remschmidt u. a. (Ed.): Multiaxial classification scheme for mental disorders of children and adolescents according to ICD-10 of the WHO. 5th edition. Huber 2006, ISBN 3-456-84284-8 , p. 33 ff.

- ^ Helmut Remschmidt: Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. A practical introduction. 6th edition. Thieme 2011, p. 157.

- ↑ a b c Guidelines for the diagnosis and therapy of mental disorders in infants, children and adolescents. 2nd revised edition. Deutscher Ärzte Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-7691-0421-8 .

- ↑ a b ICD-11 Implementation Version - who.int, accessed June 2018.

- ↑ a b c APA (2015): Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5 . Hogrefe, 2014, ISBN 978-3-8017-2599-0 , disorders of neural and mental development, p. 77-87 (section on ADHD criteria) .

- ^ Silvia Schneider, Jürgen Margraf: Textbook of behavior therapy: disorders in childhood and adolescence. Springer Medizin Verlag, Heidelberg 2009, pp. 412-428.

- ↑ RM Alderson, LJ Kasper, KL Hudec, CH Patros: Attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and working memory in adults: a meta-analytic review. In: Neuropsychology. Volume 27, Number 3, May 2013, pp. 287-302, doi: 10.1037 / a0032371 , PMID 23688211 (review).

- ↑ a b c Tobias Banaschewski et al. (2017): Attention Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder: A Current Inventory . March 3, 2017, See Stw. Neuropsychologie, doi : 10.3238 / arztebl.2017.0149 ( aerzteblatt.de [PDF]).

- ^ A b SJ Kooij, S. Bejerot, A. Blackwell, H. Caci, M. Casas-Brugué, PJ Carpentier, D. Edvinsson, J. Fayyad, K. Foeken, M. Fitzgerald, V. Gaillac, Y. Ginsberg , C. Henry, J. Krause, MB Lensing, I. Manor, H. Niederhofer, C. Nunes-Filipe, MD Ohlmeier, P. Oswald, S. Pallanti, A. Pehlivanidis, JA Ramos-Quiroga, M. Rastam, D. Ryffel-Rawak, S. Stes, P. Asherson: European consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD: The European Network Adult ADHD. In: BMC psychiatry. Volume 10, 2010, p. 67, doi: 10.1186 / 1471-244X-10-67 , PMID 20815868 , PMC 2942810 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ Fritz-Georg Lehnhardt, Astrid Gawronski, Kathleen Pfeiffer, Hanna Kockler et al .: Diagnostics and differential diagnosis of Asperger's syndrome in adulthood , p. 7 (PDF; approx. 487 kB).

- ^ JP Gentile, R. Atiq, PM Gillig: Adult ADHD: Diagnosis, Differential Diagnosis, and Medication Management. In: Psychiatry (Edgmont (Pa.: Township)). Volume 3, Number 8, August 2006, pp. 25-30, PMID 20963192 , PMC 2957278 (free full text).

- ↑ RE Post, SL Kurlansik: Diagnosis and management of adult attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder. In: American family physician. Volume 85, Number 9, May 2012, pp. 890-896, PMID 22612184 (free full text).

- ↑ George J. DuPaul et al. (2013): Comorbidity of LD and ADHD: implications of DSM-5 for assessment and treatment. doi: 10.1177 / 0022219412464351 , PMID 23144063 (Review).

- ↑ a b W. B. Daviss (2008): A review of co-morbid depression in pediatric ADHD: etiology, phenomenology, and treatment. doi: 10.1089 / cap.2008.032 , PMC 2699665 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ David B. Schatz, Anthony Rostain (2006):ADHD with comorbid anxiety: a review of the current literature( Memento of October 11, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF). doi: 10.1177 / 1087054706286698 (Review).

- ↑ Timothy E. Wilens (2010): Understanding attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder from childhood to adulthood. PMC 3724232 (free full text). doi: 10.3810 / pgm.2010.09.2206 (Review).

- ↑ Silvia Brem u. a. (2014): The neurobiological link between OCD and ADHD. In: Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorders. Volume 6, number 3, pp. 175-202, doi: 10.1007 / s12402-014-0146-x , PMC 4148591 (free full text) (review).

- ^ AS Walters, R. Silvestri, M. Zucconi, R. Chandrashekariah, E. Konofal: Review of the possible relationship and hypothetical links between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and the simple sleep related movement disorders, parasomnias, hypersomnias, and circadian rhythm disorders. In: Journal of clinical sleep medicine: JCSM: official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Volume 4, Number 6, December 2008, pp. 591-600, PMID 19110891 , PMC 2603539 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ A. Hvolby: Associations of sleep disturbance with ADHD: implications for treatment. In: Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorders. Volume 7, number 1, March 2015, pp. 1-18, doi: 10.1007 / s12402-014-0151-0 , PMID 25127644 , PMC 4340974 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ Christiane Desman et al. a. (2005): How valid are the ADHD subtypes? ( Memento from June 28, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF). doi: 10.1026 / 0942-5403.14.4.244 .

- ↑ Erik G. Willcutt et al .: Validity of DSM-IV attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder symptom dimensions and subtypes . In: Journal of abnormal psychology . tape 121 , no. 4 , April 10, 2013, p. 991-1010 , doi : 10.1037 / a0027347 , PMC 3622557 (free full text).

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : Attention-Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) - DSM-5 Criteria for ADHD . (Constantly updated; contains lists of individual symptoms).

- ↑ Valdas Noreika, Christine M. Falter, Katya Rubia: Timing deficits in attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Evidence from neurocognitive and neuroimaging studies . In: Neuropsychologia . tape 51 , no. 2 , 2013, p. 235–266 , doi : 10.1016 / j.neuropsychologia.2012.09.036 ( elsevier.com [accessed November 14, 2019]).