Piano sonata

A piano sonata is a solo sonata for piano . This form of instrumental composition offers a framework for processing musical, often contradicting thoughts. It is usually divided into several sentences that can also be structured internally . It developed in the course of the 17th century from other musical forms as a genre for a keyboard instrument . It received its first binding form from Joseph Haydn . For more than 150 years it was one of the central forms of piano music in alternating internal and external forms. Beethoven's piano sonatas represent a high point. During the Romantic period, they changed dramatically in terms of content and form, and at the latest with the advent of atonality at the beginning of the 20th century visibly dissolved. The theoretical concept of the sonata was subsequently abstracted from some works by musicology and its simplification often does not correspond to musical reality.

The term "sonata"

The word “sonata” ( Italian “sonata”) comes from the Italian verb “sonare” (to sound) and means something like “sound piece”. In the course of music history from 1650 to the present day, musical works of various kinds have been referred to as “piano sonata”, so that no comprehensive definition is possible. In a narrower sense, the term “sonata” only includes works that meet the definitions of the classical sonata and whose first movement corresponds to the sonata form . This means:

- A major breakdown into several, with Joseph Haydn and especially Mozart mostly three movements of the form fast - slow - fast , with the characterization dramatic - lyrical or cantable, often in song form - and often dance-like or joking.

- In the first set, an internal subdivision into topics idea ( exposure ) with sometimes preceded by the generally slower introduction, modulating and varying subjects processing ( execution ), repeating ( recapitulation - mostly in the tonic , except, for example, in. KV 545) and any Coda .

- In the first movement there is often a tonal division (tonic - dominant area ) of the exposition into the main and secondary theme.

This form can only be established since Haydn and has become increasingly obsolete since the late Beethoven and at the latest with the Romantic era . From 1900 onwards mostly only the pure term or work title “Sonata” remained, which hardly corresponded to the theoretically defined term of the sonata. Works of the 20th century also bear the work title “Piano Sonata” when, like Pierre Boulez 's third piano sonata, they explicitly reject any reference to the sonata tradition.

In the 17th century, the term “ sonatina ” often referred to the introductory movements of suites , later small, more easily playable sonatas, which usually have no or only a very short development.

The term "piano"

Until about the middle of the 18th century, the piano or clavier (spelling, for example, by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach ) can in principle denote any keyboard instrument, e.g. B. the harpsichord , the clavichord and the fortepiano , but also the organ .

The musical development of the piano sonata is more dependent on the development of the keyboard instruments than in other genres. So the harpsichord does not allow a stroke, but only a registration dynamic ( terrace dynamic ); on the clavichord, on the other hand, an infinitely variable dynamic design is possible. It also allows a kind of vibrato on the once struck note with the beat , but has a rather small tone volume with a limited range .

Piano music as a term commonly used today only arises rationally in connection with the technical possibilities and sound conceptions of the fortepiano constructed by Bartolomeo Cristofori from 1698. Nevertheless, today works for harpsichord are also referred to as piano music or piano sonata.

Early days

If one does not take the piano (harpsichord), but keyboard instruments in general as a starting point, the beginning of the genre can be set to the year 1605, when the Italian Adriano Banchieri gave his organ compositions the title Sonata or Sonata .

The first works that have survived today, known as piano sonatas , come from the Italian composer Gian Pietro del Buono from Palermo . These are arrangements of the Ave Maris Stella from 1645. There followed a few works for keyboard instrument called Sonata , e.g. B. by Gregorio Strozzi from 1687.

Baroque and early classic

At the beginning of the 18th century, piano sonatas became a popular genre. Numerous composers wrote piano and harpsichord works, which they called sonata .

Baroque

An early music theoretical mention can be found in the music lexicon of Sébastien de Brossard (1703). The term sonata was largely undefined in terms of content and was often used interchangeably with terms such as Toccata , Canzona , Phantasia , and others.

The first well-known series of piano sonatas was written by the Thomaskantor Johann Kuhnau . It is about the musical performances of some biblical histories, to be played on the piano in 6 sonatas , which were published in Leipzig in 1700. These works are considered the beginning of the German piano sonata. The illustrative pieces tell different stories of the Old Testament on the keyboard instrument. Kuhnau wrote:

“… Why shouldn't one be able to deal with the same thing on the piano as on other instruments? Since not a single instrument has ever made the clavier a precedent for perfection. "

These could be cyclical forms or single sentences. Domenico Scarlatti wrote about 555 one-movement pieces at the Spanish court in which he combined baroque and classical forms, influences of Spanish folklore ( ), as well as virtuosity and sensitivity . In some of them the cycle of movements and the form of the sonata movements are anticipated. With the sonatas, of which only a few were printed during his lifetime, Scarlatti is considered an important composer of this genre. The new musical form spread quickly. Other sonata composers from the Iberian Peninsula were z. B. Father Antonio Soler or Carlos Seixas .

Both French and Italian composers largely avoided the term sonata when dealing with compositions for piano alone. François Couperin , for example , used the term ordre for his piano works, which are actually suites and consist of several successive dance movements , and Jean Philippe Rameau published his works under the title Pièces de Clavecin . In these regions, the term sonata was used more for works for melody instruments or melody instruments and basso continuo . The trio sonata is typical for this . In the extensive piano works by Johann Sebastian Bach, there are only two works for keyboard instruments with the title Sonata , BWV 963 and 964 (an arrangement of the solo violin sonata in A minor) .

Early classic

A regular and systematic composing of piano sonatas did not begin north of the Alps until the generation of Johann Sebastian Bach's sons. Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach wrote numerous piano sonatas and also made a distinction between the emerging fortepiano and the harpsichord. Bach's sons lived precisely in the age when the harpsichord was replaced by the piano.

The development of the clavichord and fortepiano enabled a profound change in composition. For the first time in their compositions for piano, the composers used the possibility of small-scale dynamic differentiation as a stylistic parameter. Of these, for example, made the Bach sons , especially Carl Philipp Emanuel and Johann Christian Bach , heavy use. The gallant and sensitive style of piano music developed.

The works of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and Joseph Haydn, who lived almost at the same time, became role models for later composers, especially for Mozart and Beethoven. Although neither the sequence of sentences nor the form were stipulated, multiple sentences became the rule. More and more often, the basic form of encircling a slow movement with two fast movements became the norm. In his sonatas, Johann Christian Bach particularly promoted the periodization within the themes in four-measure front and back notes. A mostly cantable main theme usually follows free figuration , without clearly developing a second secondary theme, which is later obligatory in classical music. In the approximately 150 sonatas by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, who is a typical representative of the “new sensitivity ”, the contrast between different musical themes is, however, worked out more sharply and with greater contrast. These are often developed in strongly figurative spinning from a common thematic core. In his mostly highly virtuoso, imaginative and sometimes harmoniously pioneering sonatas, a clear distinction between purely thematic, expressive and more playful parts is nevertheless difficult.

With his later sonatas, Giambattista Martini turns to the style of Johann Christian Bach and early Mozart. The early classical sonatas by Pietro Domenico Paradisi and Baldassare Galuppi are also worth mentioning . The works of Friedrich Wilhelm Rust are trend-setting . Georg Benda wrote 16 sonatas and 34 sonatinas.

A group of composers worked at the court of the Palatinate Elector Karl Theodor, which had a decisive influence on the development of the instrumental style in the classical era. This so-called Mannheim school included a. a. Johann Stamitz , Ignaz Holzbauer and Christian Cannabich . Her most significant achievement in relation to the piano sonata is the introduction of a distinct thematic dualism. In the best case scenario, the main subject of the sentence is opposed to a subject that is equal. In the implementation either one of the topics is preferred or both topics are treated equally. This new technique quickly found application in symphonic works. Another important innovation was the Mannheim rocket , whose dynamics turned away from the baroque terrace dynamics with a rapid crescendo run .

Classic

The piano sonata was derived in the second half of the 18th century - and this determined its respective form - from two genres: from the classical concerto or from the sonata da camera , which roughly corresponds to the baroque suite in the sequence of movements. In connection with the piano sonata, the sonata da chiesa, the second important baroque form, played a lesser role .

The entire sonata oeuvre for piano is no longer easy to survey qualitatively and quantitatively from 1770 at the latest. The sonatas by Johann Christian Bach, but also sonatas by Muzio Clementi , Joseph Martin Kraus , Georg Christoph Wagenseil and numerous others are of particular importance in terms of genre history . In addition to the two-hand works, there were also piano sonatas for four hands or two pianos (for example by Mozart, Schubert, Brahms and Francis Poulenc ) , albeit in a much smaller number . The piano sonata developed in Italy had also established itself in other countries and cultural centers.

Viennese Classicism

The piano sonata undoubtedly experienced its first climax in the history of the genre in the Viennese classical period . Joseph Haydn (52 sonatas), Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (18 sonatas) and Ludwig van Beethoven (32 sonatas) are considered the most important authors of piano sonatas.

How different the sequence of movements can be can be clearly seen in three piano sonatas by W. A. Mozart:

- The Sonata in E flat major KV 282 (1774) begins with a slow movement, followed by a minuet with trio (referred to by Mozart as Minuet II), and the sonata ends with a fast movement. Here the relationship to the “Sonata da Camera” is close.

- In contrast, the Sonata in D major, K. 576 (1789) is a very brilliant work, the composition of which is strongly influenced by the concert, right up to recognizable tutti solo changes.

- The Sonata in A major KV 331 (1778) begins with a six-part set of variations on a well-known song-like theme (later also used by Max Reger in his Mozart Variations op. 132). This is followed by a minuet with a trio, followed by the famous 2/4 time movement “Rondo alla turca” in A minor , whose lively coda ends in major .

Joseph Haydn

In Joseph Haydn's work, the 52 piano sonatas also play an important role as an innovative experimental field for models that were later realized in orchestral forms.

His sonatas become a unity more through harmonic contexts than through thematic relationships and opposites of the classical sonata definition. Small groups of bars are usually loosely associated with each other. The order-creating function of harmony outweighs the topic formation. Thus, in the opening bars of the first movement of the G major sonata ( Hob. XVI / 8 ), loosely strung together empty phrases, triad figures and runs can be observed as really definable themes. This exposure is held together primarily by the gradual transition from the tonic to the dominant area. The later demanded contrast between main and secondary topic cannot always be precisely delimited. Haydn's approach here corresponds more to the ideas of Heinrich Christoph Koch ("A secondary idea must always be such that it leads us back to the main performance .")

The earlier Haydn sonatas, such as the C minor Sonata No. 20, are noticeably influenced by the formal preparatory work (less by the expressiveness) of Philipp Emanuel Bach. In doing so, he still remains partly in the baroque divertimento style with a simple sequence of sentences.

With the sonatas between 1760 and 1767 he created works which - taking advantage of previously unused "extreme" positions of the instrument - alternately alternate between polyphony , chordal setting and improvisational sections. In addition to the factors mentioned, the sudden motivic contrasts, increases through motif repetitions with increased intervals , and the abrupt interruptions through pauses and fermatas refer to Philipp Emanuel Bach .

In the formally more balanced and frequently played sonatas from 1773 onwards, which pay more attention to the formation and processing of themes, the “classical Haydn” and an “early model of the sonata form” are generally seen. The topic formation here gains significantly in importance compared to the overall harmony, but can nevertheless be described as monothematic.

The sonatas from 1780 onwards were then increasingly influenced by an "individualization of expression" referring to Beethoven and by Mozart's influence, which paid more attention to consistent theme and form than to melodic variation.

Some works from the sonata group from 1790, such as the E-flat major sonata from 1794 (Hob.XVI: 52), are then characterized by an expanded harmonic diversity and more differentiated dynamics.

Although Beethoven later adopted many of the creative elements of Haydn's sonata, it would be wrong to state that Haydn's musical thinking, which is more connected to the baroque idea of the monothematic affect unit of a movement, is “typical of the sonata”.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Mozart wrote 18 sonatas that piano students and concert pianists alike loved to play. In contrast to Haydn, at least in his early sonatas, he composes rather loosely strung together, cantabolic-melodic themed groups based on Johann Christian Bach. These are mostly only linked to one another in an associative manner; even when they are carried out , no further logical consequences are often drawn apart from the sequencing of thematic elements. An example of this is the sonata KV 332, in which in the first 93 bars about six thematic structures are connected with one another without any tangible connections. These are hardly taken up in the implementation, in which new topics arise instead.

In the first sonatas from KV 279 to 284, a relatively strong connection to standardized accompanying forms such as Alberti or Murky basses and / or a formulaic drive, as well as a less rich and plastic melodic inventiveness compared to later works can be ascertained. In the works of his time in Mannheim and Paris from KV 309, however, the form becomes freer, more diverse and more informal. In the sonata in A major KV 331, which consists of a set of variations, a minuet and the well-known rondo “Alla Turca”, similar to Beethoven's piano sonata No. 12 in A flat major op. 26, no movement corresponds to the sonata form. The works now impress with an almost inexhaustible melodic ingenuity. A first break-in, almost anticipating Beethoven and Schubert, of relentless severity and tragedy occurs in the A minor Sonata KV 310.

In the later sonatas from KV 475 onwards, there is an increasing concentration on the processing of themes in the sense of Haydn as well as the influence of baroque writing styles and forms such as fugue or suite, which are probably based on Mozart's intensive examination of JS Bach and Handel . This is e.g. B. can be observed in the linear, mostly two-part movement development of KV 494/533. The dramatic C minor works KV 475 and 457, on the other hand, are similar in expression and design to Beethoven's sonatas. So have Paul Badura-Skoda and Richard Rosenberg detail on striking similarities between K. 457 and Beethoven's Pathétique op. 13 back

Ludwig van Beethoven

Beethoven's 32 piano sonatas represent a climax and turning point in the history of the piano sonata. Since their creation, they have repeatedly stimulated scientists, writers and artists to analyze and sometimes daring lyrical analogies or philosophical speculations. Beethoven explores the formal, harmonic and other limits of the sonata and piano music almost to their limits in them and increasingly overcomes them in the later sonatas. Beethoven also combines the classical and romantic eras in his piano sonatas. Hans von Bülow summarized their meaning in the following words:

"The preludes and fugues of the Well-Tempered Clavier are the Old Testament, the sonatas of Beethoven are the New Testament of the piano player."

The popular - albeit controversial - three-part division of the work differentiates between early, middle and late Beethoven (in the case of the sonatas approximately op. 2 to 22 - op. 26 to 90 - op. 101 to 111).

In the first phase, the classical demands on sonata movements and cycle formation are formulated and combined with abundant inspirations. The form of the sonata movement can be seen here most clearly. In the middle period, the will to organize the entire work organically from uniform thematic material, including musical experiments, became increasingly decisive. An individualistic will to express, which increasingly ignores the formal requirements and is based on extra-musical "poetic reproaches", increasingly overcomes the traditional forms. The late work, often described as philosophical, speculative or incomprehensible, is characterized by different, sometimes contradicting tendencies. The radicalized disregard for musical conventions and the further increased technical requirements are partially offset by reminiscences of their own early work, the inclusion of baroque forms (fugue) and a reduced, thinned-out piano setting.

Early stage

Beethoven's first sonatas are - despite all their independence - characterized by the effort to meet the requirements of the traditional canon of rules. Conventional periodizations in two-, four-, and eight-bar groups are followed quite closely. The topic formation often consists of musical basic material such as broken triads, scale movements or simple holdings , which are coupled with accompanying figures typical of the time. A stylistic reference to Haydn and Mozart cannot be ignored. Both shaped Beethoven in his youth. A comparison of the Adagio from Beethoven's Op. 2/1 with Haydn's String Quartet, Op. 64, No. 5 makes this clear. However, this already changes with the more individually designed and expanded E-flat major sonata op. 7 and op. 10/1, which for the first time consistently takes up the " dialectical theme principle".

Here Beethoven consistently uses what is later called the principle of contrasting derivation , in which different, even contradicting themes are developed from a common structural core, thus overcoming the difference between thematic arrangement and processing. What is important here is the distinct thematic dualism that Beethoven realized more and more frequently. The contrast of the first eight bars of dotted triad notes in the forte and the leading resolution in the piano proves to be the basis for the following transition, the second theme from bar 56, and the final group from bar 94. The most popular work of this phase is then that in the heroic style Pathétique (op. 13), which was thoroughly concerned with external effects. With this work, the young artist presented himself to the public for the first time as a pianist of his own works.

Middle phase

From the piano sonata No. 12 (op. 26) the sonata form is increasingly broken up, both in its external and internal structure. This already shows Op. 26, which has little in common with the structure of a sonata with the first movement, an andante with variations, and the funeral march of the third movement.

The proportions and functions of the individual movements change. The center of gravity shifts increasingly from the first movement to the finale, if only in terms of length. The previously only appended short coda is expanded into a kind of “second development”, and the boundaries between exposition and development begin to evaporate.

Classical musical aesthetics and forms - such as B. in the popular Moonlight Sonata (op. 27 no. 2) , which bears the subtitle Sonata quasi una Fantasia - increasingly being displaced by poetic, fantastic, unconstrained ideas that anticipate romanticism.

After a few more "classically relaxed sonatas" (for example the op. 49 sonatas), the Waldstein sonata (op. 53) and the appassionata (op. 57) raise the virtuosity and individual will to express themselves to a previously unknown level. That these tendencies overstrain the conventional framework of the sonata concept is shown by the contradicting attempts of musicology to interpret the exposition of the Appassionata according to conventional "school patterns". The Appassionata is one of the most discussed works in music history. It is often viewed as Beethoven's most important sonata.

Late phase

The sonatas from op. 90 (Beethoven's last six piano sonatas) are formal and varied and contradicting the predominant musical tendencies in them.

The first and last of these sonatas (op. 90 and op. 111) have a reduced number of movements. In addition, in all sonatas, on the one hand, the tendency to reduce the pianistic means and, on the other hand, to exaggerate and overstretch them. This concerns z. B. the simplification to simple chamber music -like two-part voices in the first movement of op. 110 or to mute in recitative-like parts as in the third movement of the same work, contrasted with a further increased virtuosity and extreme overstretching in the hammer piano sonata op. 106. The "Rückerinnerung" bygone times in the simple style of the early sonatas reminiscent of Haydn (op. 109) is sometimes juxtaposed with a bitter and philosophical harmony that anticipates the music of the 20th century and is sometimes shaped by dissonances . Some things, like the A repeated over several bars in op. 110, seem bizarre and functionally incomprehensible in the pursuit of an “individual radicalization that gets rid of all conventions and considerations”. The principles of polyphonic variation and the associated recourse to baroque forms, especially the fugue , are particularly important . While these appear in op. 10/2 without a consequent development in the form of a fugato , the movements from op. 106 and 110 entitled “Fuga” represent fully valid fugues. Beethoven's fugues allow one another formal and harmonious freedoms, which in the conventional style of fugue would be considered a violation of the rules. This mixing and dissolving of formal categories prompted Thomas Mann to put the following words in the mouth of the fictional character Wendell Kretzschmar of his novel Doktor Faustus in relation to Beethoven's last piano sonata :

"... It happened that the sonata in the second movement, this enormous one, came to an end, to an end never to return. And when he says: 'The sonata', he doesn't just mean this, in C minor, but rather the sonata in general, as a genre, as a traditional art form ... "

Changes to the instrument

Around 1800 the construction of the pianos changed. For the first time, they received supports in the frame to balance the string tension . This led to an increase in the range up to what is common today. This innovation brought about a lasting expansion of the musical possibilities of expression, especially when using extreme registers. One of the earliest works to consciously exploit this new range is the so-called Waldstein Sonata by Ludwig van Beethoven. The development of the repetition mechanism by Sébastien Érard in 1821 first made a rapid sequence of strokes possible and thus the virtuoso play of Romanticism.

Virtuosity and house music

In the first decades of the 19th century, a large number of composers, some of whom are hardly known today - supported by the flourishing musical publishing industry and the emergence of salon music from 1830 - were involved in the increasing production of sonatas. In the first three decades of the 19th century, the technical level of professional pianists - partly due to the rapid structural improvements of the instrument - reached an unprecedented level.

Many pianists and composers, almost forgotten today, created the basis for the piano technique of the Romantic period with its wide-ranging passages, jumps, octave and double stops, as well as other “witchcrafts”. In the works, which were often caught up in the fashion trends of that time and whose “musical content” is now mostly judged critically, virtuosity comes to the fore. Composers who stand out from the “mass-produced goods” of the time are Johann Nepomuk Hummel with his then very popular and highly virtuoso F sharp minor sonata op. 81 ( ) and Carl Maria von Weber . Besides them there were many famous composers such as Jan Ladislav Dussek , Leopold Anton Kozeluch , Ignaz Moscheles , and Ferdinand Ries , who are known only to a few today.

At the end of the 18th and 19th centuries, it became an indispensable part of a good upbringing, especially for daughters from the upper European bourgeoisie, to have enjoyed a musical education. Mostly this included piano and singing lessons. In addition to baroque music and romantic character pieces, this also included sonatinas designed as practice pieces, e.g. B. by Clementi , Diabelli , and Kuhlau , as well as technically simpler sonatas by Haydn (Hob. 1-15), Mozart (KV 297 to 283, KV 545) and Beethoven (op. 10/1, 14, 49, 79). This created a demand for simple sonatas or sonatinas, some of which were directly tailored to the domestic music market in terms of style and technical requirements . Some of these works integrated technical tasks, which are reserved for the otherwise rather “dry” etudes , and the setting method was partly designed to give the technically less experienced pupil works that could nevertheless develop virtuoso effect during the performance .

Form discussion began in the 18th century

It is a widespread view that since the second half of the 18th century the sonata or piano sonata has followed a certain scheme with regard to the sequence or form of the movements, the formation of themes and other things. This cannot be proven on the basis of the form of the works from the 18th century. Sonatas can have one to many movements (usually no more than four), which can be composed in a variety of forms and compositional techniques. The number of topics - monothematic, thematic dualism or more than two topics - and the question of their processing versus simple sequencing cannot be answered unequivocally in reality, just as the realization or existence of the subsequently formulated parts that constitute the sonata such as exposition and development , Recapitulation, coda et cetera . The frequently rumored theory of an even, two- or four-measure periodization of the topic in front and back endings often does not correspond to reality. So z. In Haydn's G major sonata (Hob.XVI / 1), for example, the model of the four-stroke is “broken” by the inserted sixteenth- note triplet figure .

It is more likely that there is a personal or regional stylistic formal relationship between works. The works written on the Iberian Peninsula are often single-movement pieces influenced by contemporary instrumental dances. On the other hand, Italy seems to prefer the relationship to the concert as a template.

The classical-romantic sonata is a structure that was subsequently defined by theorists of the 19th and 20th centuries, primarily on the basis of Beethoven's sonatas, which postulates a regularity that did not exist in this way. It tries to summarize formal criteria and ideal content of the most diverse musical epochs despite the fundamentally different musical ways of thinking behind them.

Instead of the historically questionable sonata form definition, there are various approaches to narrowing down the genre, three of which are mentioned here:

On the one hand, it can be examined how individual types of sentences were used in music. So came z. For example, the minuet as the final movement was not only occasionally used in the piano sonata by various composers until around 1775, but was then used more and more exclusively as an internal movement, finally disappearing almost entirely from the table of movements of the piano sonata towards the end of the 18th century.

In addition, access via the musical content is possible. The form and content aspects should always be compared with the terminology. The question of what is called a sonata in a given period is vital. An isolated examination of the piano sonata is not expedient here.

Theoretical works

The term "sonata" has appeared in numerous lexicons, encyclopedias and music theory works since the beginning of the 18th century. Possibly the earliest detailed genre definition can be found in Sébastien de Brossard's "Dictionnaire de Musique" from 1703 (2nd edition 1705). Even Johann Mattheson goes into its "core melodic Science" from 1713 in detail to the genus one; he later adopted this passage unchanged in the "Perfect Capellmeister". Johann Gottfried Walther's "Musicalisches Lexikon", published in 1732, also gives a definition of the genre sonata.

All these theoretical treatments have in common that they essentially define or limit the sequence of movements and the use of the sonata in the field of instrumental music. As early as 1703, Brossard made a distinction between the “Sonata da Chiesa” and the “Sonata da Camera”, ie between the usually four-movement sonata and the suite, which consists of a free sequence of different movements.

A later, detailed definition can be found in Heinrich Christoph Koch's three-part attempt to provide instructions for composition from 1782 to 1793 and his Musical Lexicon from 1802. Koch emphasizes the central importance of a consistent musical design in the following words:

“If each part of a sonata is to contain a distinctive character, or the expression of a certain sensation, then it cannot consist of such loosely lined up individual melodic parts (note: here he calls the divertimento), [...], but one Such a part of a sonata, if it is to maintain a definite and sustained character, must consist of completely interlocking and connected melodic parts, which develop from one another in the most tangible way, so that the unity and character of the whole are preserved, and the idea, or rather the feeling of not being led astray. "

The four-movement form from the first movement in sonata form, slow movement in the aba scheme or in variation form, minuet or scherzo, as well as the fast finale (mostly as rondo ) was declared binding. The basic key relationships between the movements were also described. The first and fourth movements should be in the main key. With a minor key of the first movement, the last movement is often in the parallel major key. Like Anton Reicha later, Koch divides the first movement into two parts ("First movement, middle movement and repetition").

Later sonata definitions divide the sonata form into three parts. In 1847, Adolf Bernhard Marx emphasized the two-part tonal nature of the exposition, the demand for thematic dualism and the importance of the thematic work. He was the first to explicitly use the term “sonata form”. and expects the sonata to integrate the individual musical thoughts in the sense of a unity of the whole in its multiplicity.

"The main and secondary movements are two opposites to each other that are intimately united in a comprehensive whole to form a higher unit."

Nevertheless, as the following quote from Gottfried Wilhelm Fink shows, the concept of the sonata continued to be controversial in science.

“In the expression Sonata (Klingstück), as in most of the designations of the types of composition, there is nothing specific that indicates the character or the form: Both have only been brought into the word over time [...] So it has absolutely no special one, only you form belonging alone. "

Romanticism and 19th century

In the late works of Beethoven in particular, the sonata , like the string quartet , was defined as a genre of “special demand” by the beginning of the 19th century at the latest. Of course, this also applies to the piano sonata .

The larger dimensions of the individual works, as well as the increased demand for "originality" compared to the classic understanding naturally brought about a quantitative reduction in production. In interaction with the symphony as the most important genre of orchestral music and the string quartet as the outstanding chamber music genre, a four-movement sequence of movements prevailed. The minuet as an internal movement became rarer; a scherzo often took its place (already with Beethoven) .

The piano sonata was subject to a strong formal and conceptual change due to the completely different aesthetics and expressiveness of Romanticism. In the late romantic period , in the late works of Franz Liszt and Alexander Scriabin , the first foundations for music and piano sonata of the 20th century were considered.

Franz Schubert

At the beginning of his career, Franz Schubert had a hard time bearing on Beethoven's “legacy” and the sonata form determined by his work.

Beethoven's sonata model, based on thematic dualism and its processing, does not correspond to Schubert internally. His musical thoughts are more expressed in series forms such as the song and variation form. Schubert's melodic structures are so rounded and complete that they are less suitable for sonata-like dissection, recombination, and processing. Schubert's achievement in the field of the sonata is shown, as Alfred Brendel thinks, in the directness of his emotions, which one should not measure against Beethoven's architectural mastery in order to devalue Schubert. Unlike Beethoven, Schubert composes like a sleepwalker.

The sonatas between 1815 and 1817 were partially unfinished. The E major sonata breaks off after it has been developed, which suggests that Schubert viewed the rest of the recapitulation as just routine work to fulfill the form, or that the sonata scheme dominated it more than the other way around. For example, KM Komma writes about the first movement of the A minor Sonata D 537, which is in some ways reminiscent of Beethoven , in which the individual sections do not merge organically but are sometimes separated from one another by general pauses :

“This movement is a single doubt about the sonata in the traditional sense, a shaking of the traditional form, rearing up and exhausted breaking down. The contrasts are not antithetical , they are not carried out dialectically. "

In the sonatas from 1817 to 1819, Schubert achieved his first successes in developing his own forms, which were not "stunted Beethoven people, but fully fledged Schubert's". Thanks to the Singspiel Das Dreimäderlhaus and the film of the same name with Karlheinz Böhm , the A major sonata in particular has become Schubert's most popular sonata. Until 1825, apart from the Wanderer Fantasy - one of Schubert's most important piano works, which brings sonata and fantasy form to a successful synthesis - there was a break in sonata creation.

In the works that followed, Schubert removes all the restrictive fetters of the tradition of the genre. The control and modulation in distant, partly mediantically related keys loosen the harmonic concept of the sonata. In the C major sonata D 840 is reached after 12 bars in A flat major and leads via B flat major and A flat major to the B minor of the subordinate movement. The recapitulation is then in B major or F major. Schubert sometimes structures entire sentences using rhythmic models rather than themes or harmonics. The first movement of the A minor sonata DV 784 is based on three rhythmic formulas assigned to the first and second theme and the transition, which are also combined with one another. The formulas of the first and second topic are used in two similar or separate forms. While D 840 was initially viewed as negative and a dead end due to its harmonic and formal structure, it is now seen as a key work for Schubert's idea of the sonata principle and his musical thinking and as a forerunner of the great sonata cycles of 1825/26.

The sonatas from 1825 onwards can be regarded as the high point of his sonatas. Here Schubert creates a harmonious, daring, wide arc. They are designed as spacious musical "stories" with a lyrical basic character. Robert Schumann praised the “heavenly lengths” in these works by Schubert. With their sudden ritardandi and breakpoints, they seem very improvisational and romantic.

Sonata and Fantasy

The term fantasy for a more freely designed, rather improvisational-rhapsodic piece of music for keyboard instruments was already popular in the baroque era. Examples of this are JS Bach's Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue or Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach's and Mozart's C minor Fantasies . From 1810 onwards, this form and designation, which corresponded to the romantic art theory, enjoyed increasing popularity, also for reasons of the hoped-for better public acceptance.

The genres Fantasy and Sonata influenced each other with increasing loss of the criteria that separated them from one another. Beethoven's sonatas op. 27 with the subtitle Sonata quasi una Fantasia , which combines elements of both genres, also had an influence . Gottfried Wilhelm Fink described this trend in 1826 in a review of Schubert's Sonata in A minor, op.42 as follows:

“Many pieces of music now have the name phantasy in which the phantasy has very little or no part, and which are only christened because the name sounds good [...] Here, conversely, a piece of music uses the name sonata to which the imagination clearly has the largest and most decisive share ... "

In Schubert's Wanderer Fantasy , both genres are then merged with one another in a forward-looking manner. The work can also be interpreted as an attempt, pointing ahead to Franz Liszt , to transfer the formal parts of the sonata main movement to the sequence of movements of the entire work. Accordingly, Allegro, Adagio, Scherzo and Finale would take over the functions of exposition, development, recapitulation and coda. Other important fantasies are Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy's Fantasia in F sharp minor, op.28, which was originally called the Scottish Sonata (Sonata écossaise) , which nevertheless has a sonata outline behind all interspersed runs and chord breaks, and Robert Schumann's Fantasie in C major, op.17, which is the sonata form in view of the many harmonious and formal freedoms can only be guessed at. In the titles of works, too, the consequences of the efforts to emancipate Beethoven's op. 27 in the direction of a “freer form” will soon be drawn: the composer calls Franz Liszt's one-movement Dante sonata a Fantasia Quasi Sonata . One also begins to redefine the key relationship in multi-movement works, so that the connection to a single main key no longer appears mandatory. With his Sonata quasi fantasia op. 6 , Felix Draeseke was one of the first to realize such a concept: the three movements are in C sharp minor , D flat major and E major .

Keeper of the classic

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy and Johannes Brahms show in their work, although they are of course in the Romantic era, both formally and expressively seen quite classical features. Brahms, for example, is continuing the Beethoven tradition of expositions.

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy was occasionally classified as an epigone who wanted to preserve tradition as a classicist for his weaker, sometimes smooth and sentimental works . This is also clear from a statement made by Schumann who, on the occasion of a review of Mendelssohn's sonatas in 1827, despite all admiration for the works, said that one should imagine the composer as:

"... snuggling up to Beethoven with his right hand, looking up at him like a saint, and guided by Carl Maria von Weber on the other hand."

A number of analogies - such as between Mendelssohn's B flat major sonata and Beethoven's hammer piano sonata - show that this image is not entirely unfounded - in his sonata work, which sometimes lacks personal traits, until he was twenty. Mendelssohn's sonatas combine virtuosity with the sphere of “domestic idyll” and a contrapuntal style that sometimes appears learned. In contrast, he is much more convincing in many of his songs without words , the freer F sharp minor Fantasia from 1834 and the Variations sérieuses , which are classified as masterpieces of the genre.

Johannes Brahms

In the course of the controversy about the progressive New German School around Franz Liszt, Brahms was stylized by the public as its “antipope” and referred to as the “true heir and successor” of Beethoven. Despite his long-overlooked progressiveness, he held on to the traditional forms and the sonata movement in principle. The three piano sonatas, which fall into his early creative period, avoid Lisztian and Chopinian virtuosity and rather draw their inspiration from folk songs. Albert Dietrich remembers :

"Then he told me in the course of the conversation that he liked to remember folk songs when composing and that the melodies then came on by themselves."

Conventional thematic dualism resigns in favor of a continuous derivation process that allows the secondary theme to emerge organically from the main theme. An example of this is the first movement of the F minor sonata, in which the main theme is gradually transferred to the secondary theme. The core motif of bars 1 and 2 is made up of dotted A-flat, G and F in thirty-second notes, and the quarter- G, in bars 8 and 9, rhythmically changed to quarters and eighth notes , and melodically widened in the intervals in bars 20 and 21 ( As - C - F - As, C - F - E - D) . The secondary theme that appears in bar 39 does not act as a contrast, but as a logical sequence prepared by variation. This is to be understood as the core of his musical technique. Arnold Schönberg later saw this Brahms approach as a future-oriented model for formal design on a purely thematic basis apart from tonal, formative elements. While this is interpreted on the one hand as the "ideal synthesis of the variation form and the sonata movement", on the other hand the "connection of the parts of the sentence as a series of variants, the sections of which still externally and formally correspond to the structure of a traditional sonata movement, but their inner musical logic and function as a whole has changed decisively through the variant technology. ”highlighted.

Compared to the first rather classically held sonata in C major, the second and third sonatas show a certain proximity to the New German School in their romantic attitude.

Typically romantic

Robert Schumann and Frédéric Chopin are still considered to be the typical and exemplary representatives of Romantic music. Nevertheless, her work shows essential approaches that refer to the music of the 20th century. Her piano work - also due to epochs - is realized more in shorter and smaller, less theoretically defined forms and titles such as Fantasy, Impromptu , Mazurka , Nocturne , Variation, Intermezzo , Romance, or non-musically inspired titles such as Nacht- / Waldstück , Phantasiestück , Children's Scenes , Singing , Arabesque , carnaval , as in the form of the sonata .

Robert Schumann

Robert Schumann's three piano sonatas, like some Schubert sonatas, lack a truly organic context due to their assembly using mostly song-like elements.

The works are more characterized by poetic reproaches and concepts ( Florestan and Eusebius ) and intellectual relationships with his wife Clara than by work aimed at thematic consistency. The "all too colorful mix of keys" that was criticized at the time is now viewed more as historically consistent harmonic progress.

"In some harmony leads dissonances are used, the subsequent resolution of which only alleviates the harshness of their impression to an experienced ear."

The forms of exposition, development and recapitulation are difficult to distinguish from one another in his sonatas. Even Schumann himself soon had doubts about the traditional function, historical justification and social position of the sonata. This is shown by his statements as a music critic, in which the increasing questionability of the genre sonata becomes clear:

“... there is no more dignified form through which they could introduce themselves to the higher criticism and make themselves pleasing, most sonatas are therefore only to be regarded as a kind of specimina, as studies of form; they are hardly born from an inner and strong urge. [...] Individual beautiful appearances of this kind will certainly come to light here and there, and they already are; but otherwise it seems that the form has passed through its life cycle ... "

Frédéric Chopin

Frédéric Chopin was often accused of not having mastered the great forms such as the piano concerto and sonata because they ran counter to his intentions. This is shown by a contemporary quote from Franz Liszt:

“He had to do violence to his genius whenever he tried to subject it to rules and regulations that were not his and did not correspond to the requirements of his mind. [...] He couldn't adapt the floating, indeterminate outline to the narrow, rigid form, which was what made his way so attractive. "

His expositions in particular (especially in the Sonata in B minor) appeared to many contemporary critics as confused and thematically “overloaded”. Musicology has now shown that this simplistic judgment is not justified.

Chopin wrote three piano sonatas which, in addition to the B minor sonata by Franz Liszt, can also be regarded as "the most pianistically and formally perfect after Beethoven". The early C minor sonata is regarded as a formally well resolved, but somewhat “academic” work of the student days, which is in the shadow of the two subsequent mature sonatas.

His second sonata in B flat minor became most popular, not least because of the funeral march (Marche funebre), which is often voiced by brass bands at funerals . In these works, Chopin treads the path towards a cyclical unity using the principle of evolving variation. Despite a modern, chromatically extended harmony, as well as the ornamentation and intricate polyphonic voice guidance typical of his style, they remain clearly structured. The side themes, sometimes very opposite in terms of their expressive content, are gradually developed from the main theme.

“Within a section, Chopin's themes sometimes appear almost static. [...] Since one theme arises from the other without any interlude or interruption, the formative power that arises from the gradual transformation of the thematic thought can be determined in Chopin's music more than anywhere else. "

Chopin often violates tonal or formal rules of the sonata movement. These “rule violations” against the “conventional sonata form” can, however, also point to a “consciously changed conception of the sonata movement” in the sense of the lines followed by Liszt and others later.

The unusual second sonata met with astonishment among some contemporaries. Robert Schumann, who had introduced Chopin to the professional world as a genius, wrote: "That he called it a sonata, one would rather be called a Caprice, if not an arrogance that he was just bringing his greatest children together." He wanted the funeral march to be replaced by an “Adagio, for example in Db”; He completely rejected the frenzied unison finale, at which Anton Rubinstein heard the "night wind sweep over the graves".

In contrast to the gloomy second sonata, the third makes a lighter impression. The beautiful, classically executed cantilena of the second theme in the Allegro maestoso, the airy eighth-note figures of the scherzo and the largo, which is reminiscent of a nocturne , contribute to this. The work ends with an intoxicating finale in rondo form, which “rhapsodically anticipates Wagner's Valkyries ride” and whose brilliant coda is reserved for the virtuoso.

Outside the German area

The focus of sonata development in the Classical and Romantic periods was mainly in the Central European countries, which were shaped by German culture and language ( German countries or German Empire , Austria-Hungary and peripheral Denmark as well as parts of today's Poland and the Czech Republic ). In countries with a high musical level of cultural independence, such as Spain, Italy and France, the piano sonata played a rather secondary role in music creation. In the latter, only isolated examples are to be mentioned, such as the programmatic sonata op. 33 The Four Ages by Charles Valentin Alkan or the E-flat minor sonata by Paul Dukas , the sonatina in f sharp - just like Maurice Ravel's “classical laws”. Minor - already carried over to the 20th century. The form of the sonata was understandably far removed from the music of Impressionism . The sonata genre does not appear in Claude Debussy's extensive piano works . In contrast, it flourished in the Scandinavian countries and Russia, which were more willing to receive German musical traditions.

In the Scandinavian region, Johann Peter Emilius Hartmann , Niels Wilhelm Gade , and Edvard Grieg should be emphasized. Hartmann's works, which were highly praised at the time, almost meet the requirements of the sonata form as a “school”. In his second sonata, drone and organ sounds referring to Northern European folk music can be heard. The strict sonata conception is broken in Gade's work in favor of a “poetic basic mood” that is expressed more in song-like forms. Gade's specifically " Nordic tone " was already emphasized by Schumann:

“… Our young musician was brought up by the poets of his fatherland, he knows and loves them all; the old fairy tales and legends accompanied him on his boys' wanderings, and Ossian's gigantic harp towered over from England's coast. "

The only sonata by the Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg, on the other hand, contradicts - despite a progressive harmony referring to Impressionism - with its string of miniature-like, sometimes “typically Nordic ” coherent thoughts, very much the “development concept” of the sonata. ( )

Russia

19th century Russian music was shaped by the struggle between “pro-western” musicians who took over German music tradition, such as Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , and self-taught people who tried to establish “national music” based on autochthonous influences, such as the group of Five floated forward. The piano sonata, as a form-conscious genre, therefore had more of a chance with the “traditionalists”. The virtuoso, but musically not very innovative sonatas by Anton Grigorjewitsch Rubinstein were popular at the time . Other works to be mentioned are Tchaikovsky's G major sonata, conceived with stirring rhythm and romantic gestures, Alexander Konstantinowitsch Glasunov's two sonatas, and Sergei Mikhailovich Lyapunov's one-movement sonata in F minor, Op. 27, which is based on Liszt. The only one that breaks new ground in terms of form and harmony Alexander Scriabin was to remain the composer.

Modern thinker

Although Franz Liszt and the early Alexander Scriabin can be assigned to the late Romantic period, because of the harmonious and formal freedoms and innovations in their late work, they can also be seen as pioneers of the music of the 20th century and a modernized form of the sonata.

Franz Liszt

In the work of Franz Liszt there are already significant factors relevant to the later "dissolution" of the piano sonata in the 20th century. The trend towards program music, which breaks the mold, should be mentioned here. Liszt claims to be "allowed to determine the forms through the content" and writes:

"With or without the consent of those who consider themselves the highest judges in matters of art, instrumental music will advance more confidently and victoriously on the path of the program."

This shift in emphasis becomes clear in the title of his Dante sonata , to which he gives the addition Fantasia quasi Sonata based on Beethoven's op. 27 . Based on Beethoven's principle of “contrasting derivation”, monothematic compositional principles that contradict the dialectical sonata principle become decisive. Virtuosity becomes a means of variation and formal integration of experimental material. Liszt's progressiveness as an early pioneer of atonality was only recognized late. Almost twenty years before Tristan Wagner, who changed the musical world, indicated revolutionary harmonic changes, especially in Liszt's piano works. Other composers continued on this path until the sonata form was broken.

The B minor sonata ( ) is a good example of this, because its innovations have greatly influenced composers such as César Franck and Alexander Scriabin. With his great sonata from 1853, Liszt tried to give the movements that merged into one another the large form of a sonata main movement with a broad coda. Science has devoted an abundance of different shape analyzes to this sonata. Even the contemporary Louis Köhler certified it "despite the deviation from the well-known sonata form" that it was "structured in such a way that its bottom plan in the main lines shows parallels with those of a sonata". The connection between one-movement and multi-movement is emphasized, as is the pursuit of cyclical unity across works. Often attempts are made to describe the work with the definition of a “synthesis of sonata movement and sonata cycle”.

List of important composers of piano sonatas in the 19th century

- Beethoven, Ludwig van (1770–1827; 32 sonatas)

- Brahms, Johannes (1833–1897; 3 sonatas)

- Burgmüller, Norbert (1810–1836; 1 sonata)

- Chopin, Frédéric (1810–1849; 3 sonatas)

- Clementi, Muzio (1752–1832; 72 sonatas)

- Draeseke, Felix (1835–1913; 1 sonata)

- Kalkbrenner, Friedrich (1785–1849; 15 sonatas)

- Herz, Henri (1803–1888; 1 sonata)

- Hummel, Johann Nepomuk (1778–1837; 4 sonatas and 1 sonatina)

- Liszt, Franz (1811–1886; 1 sonata)

- Lyapunow, Sergei Michailowitsch (1859–1924, 1 sonata and 1 sonatina)

- Reubke, Julius (1834-1858; 1 sonata)

- Schubert, Franz (1797–1828; 11 completed sonatas)

- Schumann, Robert (1810–1856; 3 sonatas, Fantasy in C major op. 17 can also be counted among the sonatas )

- Thalberg, Sigismund (1812–1871; 1 sonata)

- Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich (1840–1893; 2 sonatas)

- Weber, Carl Maria von (1786–1826; 4 sonatas)

20th century

The piano sonatas, like the music of the 20th century, are generally characterized by three tendencies:

- The abandonment of tonality in favor of free tonality, atonality , as well as twelve-tone and row technique.

- The preservation of any tonality in bitonality , own tonality concepts, or the neoclassical recourse to traditional design means.

- The abandonment or conscious continuation or reactivation of traditional structuring principles and forms.

Alexander Scriabin

In the ten piano sonatas of Scriabin (apart from two early works) , the formal and harmonic development from late Romanticism to atonality and the associated dissolution of the sonata form can be observed particularly well. This path began with works that are still very reminiscent of Chopin and occasionally Liszt and that show the influence of Richard Wagner . It continued through an extreme harmonic alteration to free and atonal works and also shows a formal process of dissolution.

Already in the first sonata there is a “community of substances that braces all movements together through a characteristic three-tone motif ” as well as a “ Nachtristanian alteration harmony”. In the first three sonatas, despite the improvisational character of the music through many ritardandi, fermatas , general pauses, and tonally difficult to determine sound impressions, there is still musical logic due to topic transformations and their development / connection, as well as a rudimentary functional harmonic bond. In the third sonata , despite the four movements in the large formal structure, the individual sections no longer have the thematic dualistic or harmonic functions following the sonata principle, but are rather to be understood as the development of the themes from a "primordial cell", which can also occur contrapuntally, simultaneously. The cyclical amalgamation of movements based on special intervals, such as the upward leap in fourths in the 3rd and 4th sonatas , or whole fourth chords ( promethical / mystical chord ), is becoming increasingly important than conventional theme formation.

The sonata form becomes more and more an empty shell, and from the 5th sonata onwards , one movement is achieved. Five themes form the basis of a development that extends the sonata form. For the last time, Scriabin has set changing omens here, albeit frequently. The metric which z. B. in the first 48 bars of op. 53 changes between 2/4, 5/8, and 6/8 and is also polymetric, can no longer have a formative effect.

Sonatas 6 to 10 then create shape through the concentration on certain “sound centers” and rhythmic forms, and thus - in preparation for the serial technique - complete the final end or change in the sonata form.

Atonality

In atonality or twelve-tone music, the sonata finally loses its formative power, which was inextricably linked with the tonality and the functional harmonic meaning of the chords (especially tonic and dominant). This brought Theodor W. Adorno follows expressed:

“The meaning of the classic sonata reprise is inseparable from the modulation scheme of the exposition and the harmonic deviations in the development. [...] The main difficulty of a twelve-tone sonata movement lies in the contradiction between the principles of twelve-tone technique and the concept of the dynamic, which constitutes the sonata idea. [...] Just as it (note: the twelve-tone technique) devalues the terms melos and theme, it excludes the actually dynamic form categories, development, transition, development. "

Nevertheless, Arnold Schönberg and his “students” dealt intensively with the sonata problem and created works in this genre. Atonal are z. B. Ferruccio Busonis Sonatina seconda, , Ernst Kreneks third Klaviersonate which applies despite twelve-tone traditional set of construction techniques, or Eisler op Klaviersonate. 1,.

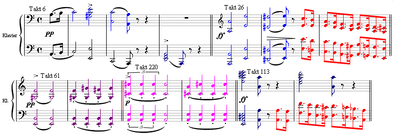

In Eisler's 3rd Piano Sonata (see illustration), the twelve-tone row runs in the upper part of the right hand, followed by the reversal of Cancer (without the tones 8 and 9) in the lower part, and later the original figure in the left hand. Due to the theme as an essential form-forming element, the paradox of a sonata form without tonal structure seems possible.

The American Charles Ives takes a less academic approach to the sonata problem and in the three-page sonata and his piano sonatas 1 and 2 syncretistically combines classical forms, standard cadences , Beethoven quotations from the 5th symphony and the hammer piano sonata , ragtime , chorales, poly- and atonality , and cluster . This can be understood as both an homage to and a satirization of “sacred traditions of European musical tradition”. Ives himself writes about the title of his second sonata:

"A group of four pieces, called a sonata for want of a more exact name, as the form, perhaps substance, does not justify it."

Extended tonality

The multiple movements and a certain formal reference to works of the 19th century can be found primarily in composers who are still working tonally and with a rather conservative musical aesthetic or tonal language - measured against the respective time - such as Stravinsky , Hindemith , Prokofiev or Béla Bartók . However, following the anti-romantic sense of time of the 1920s, the “heroic-monumental” term of the sonata was mostly avoided and more objective and diminutive terms such as sonatina , small sonata or simply piano piece were used .

The access to traditional forms in the course of neoclassicism and neo-baroque , albeit alienated by modern means, plays an essential role . Examples of this are Prokofiev's sonatas 3 and 5, which use a hard and clear style to avoid romanticism and are based on the classical model. In his three sonatas, Paul Hindemith also takes into account his own concept of tonality created in the “Instruction for Tonsatz”, as well as the formal criteria of the sonata, and Béla Bartók tries in his sonata from 1926 to meet the requirements of the sonata form through the construction of rhythmic elements. By Sergei Rachmaninov two monumental, post-romantic piano sonatas (1907 and 1913) come. Composers like Max Reger and his successors, such as Joseph Haas , Julius Weismann and Hermann Schroeder , prove to be “keepers” of classical and romantic form and musical content in their sonatas and sonatinas.

After 1945

With the serial composition technique that dominated in the first two decades after the Second World War, the piano sonata sank to an almost meaningless form. It is doubtful that works like Pierre Boulez 's three atonal sonatas can still be called sonatas in view of his statements that “these pre-classical and classical forms are the greatest absurdity in contemporary history”. The same applies to the 16 sonatas Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano by John Cage . In his three-movement Sonata per Pianoforte from 1959, Hans Werner Henze constructed interrelationships across movements by transforming the basic motif material. Henze writes:

“Perhaps it is true that structures like the sonata no longer have any constructive meaning. With the abandonment of functional harmony, it is in any case called into question. Despite the extinction of some of their typical elements of life, typical design factors have remained, tensions continue to exist, and new polarities have been invented and can be further invented ... "

In this sense, Friedrich Goldmann's Piano Sonata (1987) is significant, as it explicitly turns the friction between the traditional form model and the radically contradicting sound material into an independent level of experience. Piano sonatas are still rarely represented in contemporary music, but some composers even write entire cycles of piano works, but mostly programmatic titles are used (e.g. Moritz Eggert : Hämmerklavier ) or composers opt for the more liberal term piano piece . Important representatives of this genre are Karlheinz Stockhausen and Wolfgang Rihm , and it is not uncommon for them to fall back on classic sonata models and reinterpret these forms. In his Jazz Sonata for Piano (1998) , Eduard Pütz created a combination of classical form and stylistic features of jazz .

List of important composers of piano sonatas in the 20th century

- Barber, Samuel (1910–1981; 1 sonata)

- Bartók, Béla (1881–1945; 1 sonata)

- Bax, Arnold (1883–1953; 4 sonatas)

- Berg, Alban (1885–1935; 1 sonata)

- Blacher, Boris (1903–1975; 1 sonata)

- Bohnke, Emil (1888–1928; 1 sonata)

- Boulez, Pierre (1925-2016; 3 sonatas)

- Bridge, Frank (1879–1941; 1 sonata)

- Cage, John (1912–1992; Sonatas and Interludes)

- Chatschaturian, Aram (1903–1978; 1 sonata and 1 sonatina)

- Copland, Aaron (1900–1990; 1 sonata)

- Eisler, Hanns (1898–1962; 3 sonatas)

- Enescu, George (1881–1955; 2 sonatas)

- Frommel, Gerhard (1906–1984; 7 sonatas)

- Ginastera, Alberto (1916–1983; 3 sonatas)

- Goldmann, Friedrich (1941–2009; 1 sonata)

- Haas, Joseph (1879–1960; 3 sonatas)

- Henze, Hans Werner (1926–2012; 1 sonata)

- Hindemith, Paul (1895–1963; 3 sonatas)

- Ives, Charles (1874–1954; 2 sonatas)

- Martinů, Bohuslav (1890–1959; 1 sonata)

- Jolivet, André (1905–1974; 1 sonata)

- Kabalewski, Dmitri (1904–1987; 3 sonatas)

- Karg-Elert, Sigfrid (1877–1933; 3 sonatas)

- Kochan, Günter (1930–2009; 1 sonata)

- Krenek, Ernst (1900–1991; 7 sonatas)

- Medtner, Nikolai (1880–1951; 14 sonatas)

- Milhaud, Darius (1892–1974; 2 sonatas)

- Ornstein, Leo (1892–2002; 5 sonatas)

- Pepping, Ernst (1901–1981; 4 sonatas)

- Pütz, Eduard (1911–2000; Jazz Sonata, Jazz Sonatina)

- Prokofjew, Sergei (1891–1953; 9 sonatas)

- Rachmaninow, Sergei (1873–1943; 2 sonatas)

- Shostakovich, Dmitri (1906–1975; 2 sonatas)

- Schroeder, Hermann (1904–1984; 3 sonatas, 3 sonatinas)

- Scriabin, Alexander (1872–1915; 10 sonatas)

- Sorabji, Kaikhosru Shapurji (1892–1988; 6 sonatas)

- Stravinsky, Igor (1882–1971; 2 sonatas)

- Szymanowski, Karol (1882–1937; 3 sonatas)

- Tippett, Michael (1905–1998; 4 sonatas)

- Ullmann, Viktor (1898–1944; 7 sonatas)

- Valen, Fartein (1887–1952; 2 sonatas)

See also

literature

General

- Dietrich Kämper: The piano sonata after Beethoven - From Schubert to Scriabin . Scientific Book Society, 1987, ISBN 3-534-01794-3

- Thomas Schmidt-Beste: The Sonata. History - forms - analyzes . Bärenreiter, 2006, ISBN 3-7618-1155-1

- Stefan Schaub: The sonata form in Mozart and Beethoven (audio CD). Naxos, 2004, ISBN 3-89816-134-X

- Wolfgang Jacobi: The Sonata . Buch & Media, 2003, ISBN 3-86520-018-4

- Karl G. Fellerer, Franz Giegling: Das Musikwerk , Volume 15 (Edition of the 1970s), Volume 21 (Edition 2005) - The Solo Sonata. Laaber-Verlag, 2005, ISBN 3-89007-624-6

- Klaus Wolters: Handbook of piano literature for two hands Atlantis, 1977, ISBN 3-7611-0291-7

- Reinhard Wigand: Form analysis of piano and chamber music works from the Baroque, Classical and Romantic periods . Publishing house Dr. Kovac, 2000, ISBN 3-8300-0135-5

- Fred Ritzel: The development of the sonata form in the music theoretical literature of the 18th and 19th centuries . Breitkopf u. Härtel, 1968

- Matthias Hermann: Sonata movement form 1 . Pfau-Verlag, 2002, ISBN 3-89727-174-5

Baroque and early classic

- Maria Bieler: Binary movement, sonata, concert - Johann Christian Bach's piano sonatas op. V in the mirror of baroque formal principles and their adaptation by Mozart . Bärenreiter, Kassel, 2002, ISBN 3-7618-1562-X

- Wolfgang Horn: Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach's early piano sonatas - a study of the form of the first movements together with a critical examination of the sources . Verlag der Musikalienhandlung Wagner, Hamburg 1988, ISBN 3-88979-039-9

- Maria Biesold: Domenico Scarlatti - The hour of birth of modern piano playing . ISBN 3-9802019-2-9

Brahms

- Gero Ehlert: Architectonics of Passions - A Study on the Piano Sonatas by Johannes Brahms . Bärenreiter, Kassel 2005, ISBN 3-7618-1812-2

Beethoven

- Paul Badura-Skoda and Jörg Demus: The piano sonatas by Ludwig van Beethoven . FA Brockhaus, Leipzig, 1970, ISBN 3-7653-0118-3

- Edwin Fischer: Ludwig van Beethoven's piano sonatas - a companion for students and enthusiasts. Insel-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1956

- Maximilian Hohenegger: Beethoven's Sonate appassionata op. 57 in the light of various analysis methods . Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-631-44234-3

- Joachim Kaiser: Beethoven's 32 piano sonatas and their interpreters . Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-596-23601-0

- Siegfried Mauser: Beethoven's Piano Sonatas - A musical guide . CH Beck, 2001, ISBN 3-406-41873-2

- Richard Rosenberg: Ludwig van Beethoven's piano sonatas - studies on form and performance . Volume 2. Urs Graf-Verlag, 1957

- Jürgen Uhde : Beethoven's piano sonatas 16–32. Reclam, Ditzingen 2000, ISBN 3-15-010151-4 .

- Udo Zilkens: Beethoven's finals in the piano sonatas . Tonger Musikverlag, 1994, ISBN 3-920950-03-8

Chopin

- Ursula Dammeier-Kirpal: The sonata movement with Frédéric Chopin . Breitkopf & Härtel, 1986, ISBN 3-7651-0060-9

Haydn

- Bettina Wackernagel: Joseph Haydn's Early Piano Sonatas - Their Relationship to Piano Music in the Middle of the 18th Century . Schneider, Tutzing 1975, ISBN 3-7952-0160-8

- Federico Celestini: The early piano sonatas by Joseph Haydn - A comparative study . Schneider, 2004, ISBN 3-7952-1168-9

- Uwe Höll: Studies on the sonata movement in Joseph Haydn's piano sonatas . Schneider, 1984, ISBN 3-7952-0425-9

Franz Liszt

- Michael Heinemann : Franz Liszt - Piano Sonata in B minor. Fink, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-7705-2782-8 .

Mozart

- Richard Rosenberg: Mozart's piano sonatas - shape and style analysis . Hofmeister, 1972, ISBN 3-87350-001-9

- Wolfgang Burde: Studies on Mozart's Piano Sonatas - Forming Principles and Form Types . Tubingen, 1970

Schubert

- Hans Költzsch: Franz Schubert in his piano sonatas . Olms, Hildesheim 2002, ISBN 3-487-05964-9

- Andreas Krause: Franz Schubert's piano sonatas - form, genre, aesthetics . Bärenreiter, Kassel 1992, ISBN 3-7618-1046-6

- Arthur Godel: Schubert's last three piano sonatas (D 958 - 960) - history of origin, draft and fair copy, as well as work analysis . Koerner, Baden-Baden 1985, ISBN 3-87320-569-6

Schumann

- Markus Waldura: Monomotivism, sequence and sonata form in Robert Schumann's work . SDV Saarländische Druckerei und Verlag, 1990, ISBN 3-925036-49-0

Scriabin

- Martin Münch : The piano sonatas and late preludes of Alexander Scriabin - interrelationships between harmony and melody . Kuhn, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-928864-97-1

- Hanns Steger: The way of the piano sonata with Alexander Scriabin . Wollenweber, 1979, ISBN 3-922407-00-5

20th century

- Dieter Schulte-Bunert: The German Piano Sonata of the Twentieth Century - A Form Investigation of the German Piano Sonatas of the Twenties . Cologne 1963

Web links

General

About individual composers or works

- Erik Reischl: On Beethoven's piano sonatas

- Schubert's Sonata D 840: Analysis and Interpretation (fragmentary)

- Udo-Rainer Follert: Felix Draeseke, Piano Sonata in C #, Op. 6 (Sonata quasi Fantasia)

- Herbert Henck: Charles Edward Ives (1874–1954) - Piano Sonata No. 2: Concord, Mass., 1840-1860

- Thomas Phleps: "From home behind the red lightning bolts ..." - Hanns Eisler's Third Sonata for piano ( Memento from June 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ^ Carl Dahlhaus: The idea of absolute music . Kassel 1987, p. 109

- ↑ Udo Zilkens: Beethoven's finals in the piano sonatas - general structures and individual design . P. 12

- ^ Dietrich Kämper: The piano sonata after Beethoven - from Schubert to Scriabin . P. 2

- ↑ Pierre Boulez: Clues . P. 257: "... these pre-classical or classical forms are the greatest absurdity that can be found in contemporary music."

- ↑ Note: Scarlatti's sonatas expressly name the instrument with the title Essercizi per Gravicembalo . The sonatas by Scarlatti , the Bach sons and other composers of the time are still played either on harpsichord or piano.

- ^ Siegfried Mauser: Beethoven's piano sonatas . 2001, p. 8

- ↑ Hans Fischer, The Sonata . In: Musical forms in historical series . Volume 18, Berlin, p. 13; quoted from Erik Reischl: Beethoven's piano sonata op.2 no.3 - “The double sonata” - A historical and formal investigation .

- ↑ Note: The American harpsichordist and Scarlatti specialist Ralph Kirkpatrick gives reasons that speak in favor of combining two, more rarely three, movements into a cycle. In the foreword to D. Scarlatti - 200 Sonata per clavicembalo - Parte seconda, Györgi Balla takes the view: “The sonata pairs that follow approximately after K. 100 are (in contrast to some Scarlatti sonatas actually consisting of several movements) not a real polygon. The parts of the paired sonatas are more loosely connected than the movements of the multi-part sonatas. "

- ^ Siegfried Mauser: Beethoven's piano sonatas : page 12

- ^ Siegfried Mauser: Beethoven's piano sonatas . CH Beck, 2001, p. 13

- ↑ Wolfgang Horn: Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach's early piano sonatas - a study of the form of the first movements together with a critical examination of the sources . Verlag der Musikalienhandlung Wagner, Hamburg 1988, pp. 17 ff., 60-62, 197-199

- ^ Siegfried Mauser: Beethoven's piano sonatas , CH Beck, 2001, pp. 13 and 14

- ^ Klaus Wolters: Handbook of piano literature for two hands . 1977, pp. 211 to 223

- ^ Klaus Wolters: Handbook of piano literature for two hands . 1977, p. 234: “He only used his piano work, so to speak, as a 'workshop model' for his symphonic works, as a preliminary stage, in complete contrast to Ph. Em. Bach, who from the beginning decidedly designed the piano. Here we quote an apt sentence by Oskar Brie, who wrote in 1898: 'Haydn learned more on the piano than he gave him. He transferred the contemporary piano forms to the orchestra and thus pointed the way to the symphony. '"

- ↑ Clemens Kühn: Form theory of music . 1987, pp. 135 and 136

- ↑ Heinrich Christoph Koch: Attempting a Guide to Composition, Volume II, 1782–1793, p. 101; quoted from Siegfried Mauser: Beethoven's piano sonatas . P. 7

- ^ Dietrich Kämper: The Piano Sonata after Beethoven - From Schubert to Scriabin . 1987, p. 2

- ↑ Ludwig Finscher: Joseph Haydn and his time . Laaber, 2002, pp. 429-431

- ^ Uwe Höll: Studies on the sonata movement in Joseph Haydn's piano sonatas . 1984, p. 110 ff.

- ↑ a b Clemens Kühn: Form theory of music . P. 138

- ↑ Ludwig Finscher: Joseph Haydn and his time . Laaber, 2002, p. 440

- ^ Siegfried Mauser: Beethoven's piano sonatas . P. 14 and 15

- ↑ Clemens Kühn: Form theory of music . Pp. 71 to 74

- ↑ Wolfgang Burde: Studies on Mozart's Piano Sonatas - Formative Principles and Form Types . 1970, p. 25 ff.

- ^ Klaus Wolters: Handbook of piano literature for two hands . Pp. 253 and 254

- ^ Paul Badura-Skoda: The piano sonatas by Ludwig van Beethoven . P. 62 and 62

- ^ Richard Rosenberg: Ludwig van Beethoven's piano sonatas . P. 114

- ^ Dietrich Kämper: The piano sonata after Beethoven - From Schubert to Scriabin , foreword

- ↑ An example: “To this day, Beethoven's piano music is still the gospel of a highly idealized, human breath-drenched and confessional musical art.” From Hans Schnoor: History of Music . 1954, p. 273

- ↑ An example: “Does the Weltgeist, without the knowledge of the producing subject, actually form eschatological music here ...?” From: Jürgen Uhde: Beethoven's Piano Music III, Sonatas 16-32, op.111, C minor

- ↑ Thomas Mann : Doctor Faustus . P. 86

- ^ Klaus Wolters: Handbook of piano literature for two hands. P. 271

- ^ Alfred Brendel : Reflecting on Music . 1982, p. 85

- ↑ Kurt Honolka: Knaur's history of music - From the beginnings to the classical . P. 433

- ↑ Maximilian Hohenegger: Beethoven's Sonata appassionata op 57 in the light of various analysis methods . Peter Lang Frankfurt 1992, p. 92

- ↑ Note: This three-way division goes back to Beethoven's first biographer, Johann Aloys Schlosser . She was then used by many others, such as B. Franz Liszt , who categorized Beethoven's creative phases with the following words: l'adolescent, l'homme, le dieu , taken up.

- ^ Siegfried Mauser: Beethoven's piano sonatas . P. 18

- ^ Klaus Wolters: Handbook of piano literature for two hands . P. 272

- ↑ Martin Geck : Ludwig van Beethoven, Rowohlt, 1996, Reinbek bei Hamburg, 1996, p. 103 ff.

- ↑ Kurt Honolka: Knaur's history of music - From the beginnings to the classical . Droemersche Verlagsanstalt, Munich 1979, p. 434

- ^ Richard Rosenberg: Ludwig van Beethoven's piano sonatas . Pp. 10 to 23

- ↑ Arnold Schmitz: Two principles - their importance for topic and sentence structure . 1923, pp. 38 and 96

- ↑ Udo Zilkens: Beethoven's final movements in the piano sonatas - General structures and individual design . 1994, p. 14

- ↑ Maximilian Hohenegger: Beethoven's Sonata appassionata op. 57 in the light of various analysis methods . 1991, pp. 24 to 30, and the table on page 38

- ↑ a b Udo Zilkens: Beethoven's finals in the piano sonatas . Pp. 128, 130, and 230

- ^ Paul Badura-Skoda: The piano sonatas by Ludwig van Beethoven . P. 169

- ^ Siegfried Mauser: Beethoven's piano sonatas . P. 124

- ↑ Thomas Mann: Doctor Faustus , ed. V. Peter de Mendelssohn. Collected works, Frankfurt edition 1980, chap. VIII, p. 78

- ↑ Salon music . ( Memento of the original from February 19, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF) State Institute for Music Research of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- ^ William S. Newman, The Sonata since Beethoven . 1969, p. 177

- ^ Klaus Wolters: Handbook of piano literature for two hands . Pp. 296 to 303

- ^ Dietrich Kämper: The piano sonata after Beethoven . P. 52 ff.

- ↑ Clemens Kühn: Form theory of music . dtv, 1987, pp. 124 and 125

- ↑ Heinrich Christoph Koch: Attempt at a guide to composition . Part 1 from 1782, Part 2 from 1787, Part 3 from 1793

- ^ Koch: Sonata . In: Musical Lexicon , koelnklavier.de

- ↑ Heinrich Christoph Koch: Attempt at a guide to composition ; quoted from Siegfried Mauser: Beethoven's piano sonatas . P. 10

- ^ Anton Reicha: Complete textbook of musical composition , 1832