Marco Polo

Marco Polo (* 1254 probably in Venice ; † January 8, 1324 ibid) was a Venetian trader who became known through the reports on his trip to China . He was motivated by reports from his father and uncle who had traveled to China before him. Although individual historians have repeatedly expressed doubts about the historicity of his trip to China due to incorrect information and alleged inconsistencies in the travel reports, most historians consider this to be proven.

origin

The Polos were respected citizens of Venice, but were not among the upper classes. Marco Polo himself was referred to in the archives as nobilis vir (nobleman), a title that Marco Polo was proud of. The name polo comes from the Latin Paulus and polos have been found in Venice since 971. According to an (unproven) tradition, the family originally came from Dalmatia, among other things Šibenik and Korčula were named as possible places of origin. The Polos were traders and even their great uncle Marco was active as a trader in Constantinople in 1168 and commanded a ship there. At the time of Marco Polo's birth, his father Niccolò and his uncle Maffeo (also Maffio or Matteo), about whom little is otherwise known, were on a trading trip in the east.

The journey of his father and uncle

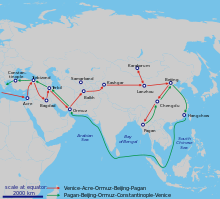

Marco Polo's father Niccolò and his uncle Maffeo set out on a trip in 1260 to sell gems on the lower reaches of the Volga . Via Constantinople they went to Soldaia (today Sudak ) in the Crimea , where Marco the Elder, the third of the Polo brothers, ran an office . Thus they traveled almost on the same route that Wilhelm von Rubruk had chosen for his mission to the east in 1253. Before the Polos left for the Mongols in Asia , the monks André de Longjumeau and Johannes de Plano Carpini had already been commissioned by Pope Innocent IV and later Wilhelm von Rubruk by order of King Ludwig IX. each started such a trip on an official mission. After their return, they each wrote their own travelogues. After their stopover, the Polos came to the area that was then ruled by the Golden Horde and stayed for about a year near Genghis Khan's grandson Berke Khan on the Volga. Subsequently, the turmoil of war that still prevailed there pushed them further and further east across the Ural River and along the Silk Road (northern branch to southern Russia) to Bukhara .

As the consequences of the war prevented them from returning, they stayed there for three years and finally joined a Persian embassy on their way to the Great Khan Kubilai . In the winter months of 1266, after traveling for a year, they arrived at the court of the Mongol ruler in Beijing (former name: Khanbaliq , Marco Polo: Kambaluk ), where they were welcomed by the Khan. He sent the Polos a so-called Païza in the form of a gold plaque on their departure , which guaranteed safe conduct and free supplies in the area of the Great Khan. In addition, they were commissioned by the Great Khan to convey a message to the Pope asking him to send oil consecrated to him from the tomb of Jesus in Jerusalem and about a hundred Christian scholars to spread the gospel among his subjects. So the Polos began their return journey to Venice, where they arrived around 1269. In the meantime, several successors had replaced the deceased Pope, and a successor election had just begun. Marco Polo's mother had also died.

Own trip

Direction of the Middle East

Pope Clement IV , who never stayed in Rome , died on November 29, 1268 in Viterbo (Italy). Due to persistent disagreement in the college of cardinals , the papal vacancy lasted until September 1271. But the Polos no longer wanted to wait for an unpredictable end to the papal election and therefore decided to return to the Great Khan even without a papal mandate or an embassy, so that the latter would not be longer to keep waiting for the fulfillment of his wishes. Before the end of the Sedis vacancy, Niccolò and Maffeo Polo set out again in 1271 and took seventeen-year-old Marco with them.

It was in Acre that he set foot in Asia for the first time. Here the three Polos explained to the local papal legate and archdeacon of Liège , Tebaldo Visconti da Piacenza, the purpose of their trip and asked him to travel on to Jerusalem , as the Mongol ruler Niccolò and Maffeo Polo had asked for on their first trip to Asia to bring him oil from the lamp of the Holy Sepulcher. With the requested permission, the Polos traveled to Jerusalem, where they could get the requested oil without any problems, and then returned to Acre. The legate now handed the travelers a letter to the Great Khan, in which it was testified that the brothers had made sincere efforts to fulfill their mission to the Pope, but that the Pope had died and that a new head of the Christian Church had still not been elected. On their subsequent journey they had already arrived on the coast of Anatolia in Laias ( İskenderun / Alexandretta) when they learned that the legate had now been elected as Pope Gregory X. , and they received a letter from the newly elected Pope, in which they were told to return to Acre immediately. Gregory X., who was in Palestine at the time of his election as a crusader , now officially commissioned the Polos as head of the church to continue their journey to the Great Khan in order to convert him to Christianity and to win them over as an ally against Islam . For this they were given two Italian monks (Brother Nicolao of Vicenza and Brother Wilhelm of Tripoli ), who were considered learned men and knowledgeable theologians , but who soon turned back on the resumed journey to Asia. Then it went via the young Polo through its colorful bazaars impressive city of Tabriz on to Saveh . After Marco Polo, the three wise men were buried here. From there, she continued her journey to the oasis city of Yazd , with by Qanaten was fed from the mountains hergeleitetem water. Marco Polo reported from this city that the silk fabrics produced there, called Jasdi , were sold by the local merchants for a good profit.

The trip then took the Polos to Kerman , where the jewelers probably traded their horses for more robust camels. Next travel stops were Rajen , a city of blacksmiths and a place where artistic steel products were manufactured, and Qamadin , the end of a route on which pepper and other spices were brought in from India . Marco Polo wrote about this now destroyed city that it was often devastated by the Tatars invading from Central Asia . The subsequent visit to the city of Hormus , today's Minab with its meanwhile silted up harbor, made a strong impression on Marco Polo, as spices, precious stones , pearls , silk fabrics and ivory were handled there.

Via detours to Asia

From here, the commercial travelers actually wanted to leave for China by sea, but the poor condition of the ships in Hormuz made them abandon their plans. Marco Polo reached the ruins of the city of Balkh in 1273 through the considerable detours that were now necessary . The city is said to have been destroyed by the troops of Genghis Khan . Marco Polo wrote: “There were magnificent palaces and magnificent marble villas here, but today they are ruins.” They also stopped in the city of Taluquan - Marco Polo describes the city's surroundings as “very beautiful”. He particularly likes the golden yellow rice fields, the poplar avenues and the irrigation canals. The city of Faisabad was then famous for its blue-green lapis lazuli gemstones, supposedly the finest lapis lazuli in the world.

The further journey led via the places Ischkaschim , Qala Panja , in 1274 via the city of Kashgar , located on the western edge of the sandy Taklamakan desert , along the southern route of the Silk Road branching out there to the oasis city of Nanhu . Marco Polo reports here of “ghosts who could lure a straggler away by calling him with voices that deceptively resembled those of his companions. And it was not uncommon for people to think that they were hearing various musical instruments, especially drums ”. Today the cause of such illusions is assumed to be the sand blowing through the dunes or the whistling desert wind.

In China

The city of Shazhou , today Dunhuang , was an important junction of the trade routes at that time, as the south and north routes to bypass the Taklamakan desert met again there. Marco Polo, who had now finally reached Chinese land, according to his report, saw in this important oasis city for the first time a large number of Chinese who had settled in one of the largest Buddhist centers in China at the time. The tour group then crossed the cities of Anxi , Yumen and Zhangye and arrived in 1275 in Shangdu as their actual destination. There Marco Polo met Kublai Khan , the Great Khan of the Mongols and grandson of Genghis Khan, in his summer residence. Kublai's empire then stretched from China to what is now Iraq and in the north to Russia . The three commercial travelers settled here under the care of the ruler until 1291.

As prefect of Kublai Khan

The Great Khan took a liking to the young European and appointed him prefect. As such, Marco Polo roamed China in all directions for several years. He got through the cities of Daidu and Chang'an (today: Xi'an ) to the city of Dali , where people, then and now, eat raw pork with garlic and soy sauce. According to his report, Marco Polo apparently found this to be quite “barbaric”, since he himself came from a culture that was not familiar with such eating habits. Via the city of Kunming he traveled on to Yangzhou , the seat of the regional government at the time. Harnesses for the Khan's army were made in the many craft workshops in this city . Marco Polo then reports on his arrival in his favorite city of Quinsai , today's Hangzhou . He raves about the magnificent palaces and public hot baths as well as the port, where ships from all over Asia came in and unloaded spices, pearls and precious stones. Later Japan is mentioned for the first time under the name Cipangu .

When troubled times threatened to break out, the Polos wanted to travel back to Venice. Despite their petitions, the Great Khan did not let them go, as they had become a valuable support to him. At this time, three Persian diplomats and their entourage appeared at the court of Kubilai Khan and asked for a bride for Khan Arghun of the Persian Il Khanate . The Mongol rulers appointed the seventeen-year-old princess Kochin to be married, which was to be taken to Persia. Since the overland route was too dangerous, the merchants seized this opportunity and suggested to the Great Khan that the princess and the diplomats should be safely escorted to Persia by sea . Reluctantly, he finally accepted the only promising offer and ultimately allowed them to travel home.

return

The return journey to Venice by sea began in 1291 in the port of Quanzhou , a cosmopolitan city with branches of all major religions. It took place on 14 junks with a total of 600 passengers , of which only 17 survived in the end. At the intermediate stops in Sumatra and Ceylon (today Sri Lanka ) Marco Polo described the cultures there. After 18 months of onward voyage, the ship reached the Persian port of Hormuz . Later on the Black Sea in the Trapezunt Empire , today's Trabzon , the officials there confiscated around 500 kilograms of raw silk from the seafarers that the Polos wanted to bring home.

In 1295 the travelers finally reached the Republic of Venice and are said to have initially not been recognized by their relatives. They allegedly revealed themselves by cutting open the hems of their clothing and taking out the gems they had brought with them.

After the journey

Not much is known today of his subsequent stay in Venice. What is certain is that he had three daughters, led two lawsuits over minor matters and bought a small house in the Cannaregio district near the corte del Milion . According to the contemporary and first biographer Jacopo d'Aqui , the population gave this name to Marco Polo because he kept talking about the millions of the great Khan and his own wealth.

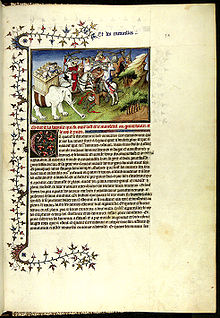

According to the chronicler and biographer Giovan Battista Ramusio , Marco Polo took part some time later as a naval commander in a naval war in which Venice had been involved with its arch-rival Genoa for years . In the naval battle of Curzola in 1298, he led a Venetian galley and was captured by Genoese, where he was held until May 1299. In the Palazzo San Giorgio used as a prison , he was allegedly urged by his fellow prisoner, Rustichello da Pisa , who is also known as the author of chivalric novels , to dictate the report of his trip to the Far East to him. The result went down in literary history as Le divisament dou monde ("The division of the world"), in French under the title Le Livre des merveilles du monde ("The book of the wonders of the world").

The “Marco Polo” was read a great deal over the next two centuries, as around 150 manuscripts have survived, including translations into other languages, e. B. into Tuscan as Libro delle meravigilie del mondo , later under the title Il Milione , or into Venetian. The Latin translation by the Dominican Francesco Pipino from Bologna, which alone is preserved in over 50 manuscripts, was most widely used . In addition, the book was evaluated by scholars of all kinds, especially geographers , who used Polo's very precise distance information for their maps. Even Christopher Columbus used this information to calculate the length of a voyage to the Indies , which he the city Quinsay said, today's Hangzhou in mainland China. But he calculated too optimistically. Columbus had an abundantly annotated copy of the travelogue Il Milione , which is now kept in a museum in Seville. The first printing took place in 1477 in Nuremberg.

As a seriously ill man, Marco Polo wrote his will shortly before his death in early January 1324, which has been preserved. This shows that soon after his release in 1299 and his return from Genoa in Venice , he married Donata Badoer , the daughter of the merchant Vidal Badoer , and later became the father of three daughters named Fantina, Bellela and Moreta, both of whom first married in 1324. He leaves a gold plaque and orders the release of his Mongolian slave Piedro Tartarino .

Marco Polo's house was roughly at the right-angled meeting of the Rio di San Giovanni Crisòstomo and the Rio di San Lio, probably on Corte seconda del Milion 5845-5847 or where the Teatro Malibran is now . It burned down in 1596.

All we know of his father Niccolò Polo is that he died around 1300, and only one will of his uncle Maffeo is known from 1310, which documents the donation of three gold tablets by the Great Khan on their first trip.

death

Marco Polo died in 1324. Since critics already considered his stories to be untrue at that time, he was finally asked by priests, friends and relatives to finally renounce the lies for the sake of his soul. According to the report of the chronicler Jacopo d'Aqui , however, Marco Polo is said to have replied on his deathbed: "I did not tell half of what I saw!"

Allegedly, after his death, Marco Polo was buried in the Benedictine church of San Lorenzo (Venice), where his father was also buried. These tombs are said to have been lost when the church was rebuilt between 1580 and 1616. According to other sources, he was buried in the now defunct Church of San Sebastiano . His legacy was worth more than 70 kilograms of gold.

His trip to China on land and back at sea, which Rustichello had written down for him, and the discoveries he described in the process, made a decisive contribution to the later discoveries in the 15th and 16th centuries and thus also to the world. as we experience it today. For this, Marco Polo continues to be recognized in today's world.

Appreciations

The lunar crater Marco Polo is named after him, as has the asteroid (29457) Marcopolo since 2002 .

Marco Polo was depicted on the obverse of the Italian 1000 lire banknote issued by the Banca d'Italia between 1982 and 1991.

Results of the Marco Polo research

Manuscripts

Little is known about Marco Polo himself, but there are around 150 manuscripts of his travelogue. The Scot Henry Yule alone was able to prove 78 manuscripts. Of these, 41 were written in Latin, 21 in Italian, ten in French and four in German. It is assumed by many researchers that Polo did not write down his own experiences in prison himself, but at most had notes that he dictated to Rustichello da Pisa. The comparative research led to the result that a manuscript in Old French is very close to the original version. This refers to the French manuscript which the Geographical Society of Paris published in 1824 and which has since been referred to as the "Geographical Text". In this regard, a Franco-Italian text and the Latin “Zelada manuscript”, both of which are also considered to be very close to the original version, are of further special interest to the researchers. There is as yet no agreement that of these three earliest manuscripts one is closest to the original version.

According to Barbara Wehr , Professor of French and Italian Linguistics at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz , the prevailing view that Marco Polo dictated his travelogue to Rustichello da Pisa and that the language of the original text was Old French may need to be corrected. In their opinion, there is a strand of the text tradition with the Latin version by Francesco Pipino da Bologna that shows no traces of the French version of Rustichello da Pisa. She concludes from this that Rustichello da Pisa only interfered with the text transmission at a later date and that there was an original text that came directly from the pen of Marco Polo and was written in Old Venetian .

Credibility of his reports

The question of whether Marco Polo really was in China has preoccupied researchers and scientists for centuries, for there is only indirect evidence of his stay in China; he himself is not mentioned by name anywhere. The latter can, however, be related to the fact that his Mongolian or Chinese name is unknown. Marco Polo's presentation of his own importance appears to some historians to be exaggerated in certain aspects.

Initially, in 1978 , John W. Haeger only questioned Marco Polo's stay in southern China with critical comments, although he considered it possible that he had met Kublai Khan after all. In 1995, Frances Wood , historian and curator of the Chinese collections at the British Library , rekindled the discussion. She advocates the thesis that Marco Polo only wrote down stories from other travelers to China in his travel report, but was not there himself. She justifies this statement with the fact that Marco Polo's travelogues do not mention essential peculiarities of Chinese culture. Nevertheless, it is mainly thanks to him that a brisk traffic developed between West and East. Wood's remarks were discussed differently in the professional world, but essentially negatively.

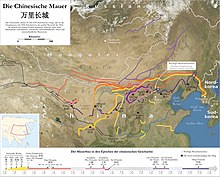

Wood sees an outstanding example for the justification of her thesis in the fact that Marco Polo does not mention the Great Wall of China . This had astonished Athanasius Kircher as early as 1667 . The anonymous editor of Thomas Astley's New general collection of voyages and travels then expressed doubts about Polo's presence on site because of this failure to mention it . In polo research, however, no importance is attached to this argument, but rather it is pointed out that, according to the results of research by Arthur Waldron, the Great Wall in its complex, which has since become world-famous, was only created through its expansion centuries later during the Ming dynasty , during the older fortifications, which already existed in Polo's time, did not play a prominent role even in the Mongolian and Chinese tradition of that time. The Mongols, ruling at the time of Marco Polo, had conquered China shortly before, overcoming the version of the Great Wall of China at the time, and their cavalry was geared towards war of movement and not towards static fortifications. It therefore seems logical that this structure was neglected during the rule of the Mongols. In addition, the wall lay mainly in the north and west on the edge of the empire, and at that time there was no reason for very few visitors to visit the remains of the wall that were still there.

Marco Polo's report on his return journey accompanying a Mongolian princess, who was chosen as the wife of the Khan of the Persian Il-Khanate, considers Frances Wood to be a takeover from a still unknown text. The Chinese historian Yang Zhi Jiu , on the other hand, found a source and described it several times that corresponds closely with Marco Polo's information about the trip, but does not mention the three Polos. It is an internal instruction by Kublai Khan, which is recorded in the Yongle Dadian , the largest Chinese medieval encyclopedia, which was not completed until the beginning of the 15th century. This instruction also gives the names of the three emissaries of the Persian Khan who traveled with the princess.

Another source also contains a brief reference to the return journey of the Polos, without, however, mentioning it: The Persian historian Raschīd ad-Dīn speaks in his work Jami 'at-tawarich ("The Universal History"), which he wrote at the beginning of the 14th century Century, briefly about the arrival of the embassy in Abhar near Qazvin in Iran and gives the name of the only surviving envoy.

Both sources were only created after Marco Polo's stay in China, so they could not have been known to him when he was writing his book, but they fully correspond to his statements, especially with regard to the names of the ambassadors and their fate. Yang evaluates this exact correspondence as evidence of Marco Polo's presence in the Middle Kingdom and ascribes the failure to mention the travelers to their relative insignificance on the part of the writers of the sources.

John H. Pryor of the University of Sydney sees another argument for their credibility in connection with the return trip of the Polos: He points out that the information in Marco Polo's book with regard to the stay at different return travel locations corresponds to the conditions that the wind cycles of the Monsoons dictate the travelers on such a sea route by sailing ship. Marco Polo himself did not know about these wind cycles and circulations in the South China Sea , the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean, neither does he mention them in his book and therefore cannot have taken them from anywhere after Pryor. Only with what we know today can it be inferred in retrospect that the wind conditions in the return area of the Polos inevitably made these stopovers necessary.

Hans Ulrich Vogel from the University of Tübingen argues that the precision with which Marco Polo describes the Chinese salt monopoly, the tax revenues based on it and the paper money system of the Yuan dynasty does not even come close to being found in any other non-Chinese source. Marco Polo must therefore have had far more than the fleeting knowledge of a traveler, but must in fact have relied on knowledge and contacts with the government acquired over many years. A pure compilation and copying of existing sources should therefore be regarded as extremely unlikely.

Film adaptations

- 1938: The Adventures of Marco Polo ( The Adventures of Marco Polo ) with Gary Cooper as Marco Polo, directed by Archie Mayo

- 1961: Marco Polo ; Feature film, France / Italy, Rory Calhoun as Marco Polo, directors: Hugo Fregonese , Piero Pierotti , Cheh Chang

- 1965: In the kingdom of Kublai Khan ( La fabuleuse aventure de Marco Polo ) - very free version with Horst Buchholz as Marco Polo, directed by Denys de La Patellière , Noël Howard

- 1982: Marco Polo ; four-part TV film, Ken Marshall as Marco Polo, director: Giuliano Montaldo

- 2006: Marco Polo ; TV-Movie, USA, Ian Somerhalder as Marco Polo, director: Kevin Connor

- 2014: Marco Polo ; TV series on Netflix

Critical text editions

-

Franco-Italian version F , preserved in the manuscript Paris, BN fr. 1116

- Luigi Foscolo Benedetto, Marco Polo, Il Milione. Prima edizione integrale (= Comitato geografico nazionale italiano. Volume 3). L. S. Olschki, Florence 1928. Until today in connection with the same, La tradizione manoscritta del “Milione” di Marco Polo. Erasmo, Turin 1962, essential for any text-critical engagement with Polo's work.

- Gabriella Ronchi, Marco Polo, Milione. Le divisament dou monde. Il Milione nelle redazioni tuscany e franco-italiana. with a foreword by Cesare Segre, Mondadori, Milan 1982. Revised edition of Benedetto's edition of version F and the Tuscan version TA.

- Text-critically obsolete, but still noteworthy because of the comment (Yule) or research history (Roux):

- Henry Yule, Henri Cordier: The Book of Ser Marco Polo the Venetian concerning the kingdoms and marvels of the East. Translated and edited, with notes, by Colonel Sir Henry Yule. Third edition, revised throughout in the light of recent discoveries by Henri Cordier. 2 volumes, John Murray, London 1903; Henri Cordier: Ser Marco Polo. Notes and addenda to Sir Henry Yule's edition, containing the results of recent research and discovery. John Murray, London 1920.

- Jean Baptiste Gaspard Roux de Rochelle: Voyages de Marco Polo. Première partie. Introduction, texts, glossaire et variants. In: Recueil de voyages et de mémoires, publié par la Société de geographie. Volume I, Éverat, Paris 1824, pp. IX-LIV (Introduction), pp. 1–288 (texts), pp. 289–296 (Table des chapitres), pp. 503–531 (Glossaire des mots hors d'usage ), Pp. 533–552 (Variantes et table comparatif des noms propres et des noms de lieux)

-

French version , Sigle Fg (after Benedetto) or Fr (after Ménard), also called Grégoire text, 18 manuscripts.

- Philippe Ménard (editor-in-chief) a. a .: Marco Polo, Le devisement du monde. 5 volumes (= Textes littéraires français volume 533, 552, 568, 575, 586). Droz, Geneva 2001-2006, ISBN 2-600-00479-3 , ISBN 2-600-00671-0 , ISBN 2-600-00859-4 , ISBN 2-600-00920-5 , ISBN 2-600-01059- 9 . Relevant critical edition based on the manuscript B1 (London, British Library, Royal 19 DI) as the basic manuscript , with extensive variants and commentary.

- Individual manuscripts:

- A2 : François Avril u. a .: The book of miracles. Manuscript Français 2810 of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. 2 volumes, Facsimile-Verlag, Lucerne 1995–1996.

- A4 : Jean-François Kosta-Théfaine: Étude et édition du manuscrit de New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, M 723, f. 71-107, You devisement du monde de Marco Polo . Thèse, Université de Paris IV-Sorbonne, Paris 2002.

- B4 (Paris, BN fr. 5649): Pierre Yves Badel: La Description du monde: édition, traduction et présentation (= Lettres gothiques. Volume 4551). Livre de Poche, Paris 1997.

- C1 : Anja Overbeck: Literary scripts in Eastern France: Edition and linguistic analysis of a French manuscript of the travelogue by Marco Polo, Stockholm, Kungliga Biblioteket, Cod. Holm. M. 304. Kliomedia, Trier 2003.

- C1 : Nils Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld: Le livre de Marco Polo. Fac-simile d'un manuscrit du XIVe siècle conservé à la Bibliothèque Royale de Stockholm. Imprimerie Centrale, Stockholm 1882.

- Text-critically outdated, but still noteworthy in the comments:

- Guillaume Pauthier: Le livre de Marco Polo , Librairie de Firmin Didot, Fils et C ie , 1865, 2 volumes (digitized volumes 1 and 2 on Google Books), based on the manuscript A1 (BN fr. 5631) using A2 (BN fr. 2810) and B4 (BN fr. 5649).

- Antoine Henry Joseph Charignon: Le livre de Marco Polo… Rédigé En Français Sous La Dictée De L'Auteur En 1295 Par Rusticien De Pise, Revu Et Corrigé, Par Marco Polo Lui-Même, En 1307, Publié Par G. Pauthier en 1867, traduit en français modern et annoté d'après les sources chinoises. 3 volumes, A. Nachbaur, Peking 1924–1928: not a critical edition, but a new French translation of the text by Pauthier with the addition of passages not contained there according to Ramusio (R), worth considering in the notes expanded according to Chinese sources.

-

Tuscan version TA (also called "Ottimo" text after one of the manuscripts), based on the Franco-Italian model, preserved in 5 manuscripts and in a Latin translation LT (see there), to be distinguished from a later Tuscan adaptation TB based on by VA, has been preserved in six manuscripts and, in turn, was the model of a Latin and German version VG preserved in five manuscripts.

- Valeria Bertolucci Pizzorussa: Marco Polo, Milione. Version toscana del Trecento. 2nd, improved edition, Adelphi, Milan 1982.

- Gabriella Ronchi 1982, see above under the Franco-Italian version

- Ruggero M. Ruggieri: Marco Polo, Il Milione. Introduzione, edizione del testo toscano ("Ottimo"), note illustrative, esegetiche, linguistiche, repertori onomatici e lessicali (= Biblioteca dell '"Archivum Romanicum". Volume I, 200). Olschki, Florence 1986.

-

Venetian version VA , one complete (VA3) and three incomplete (VA1, VA2, V5) manuscripts, as well as a complete manuscript from the Ginori Lisci private archive in Florence (VA4), which has now been lost

- VA3 (basic handwriting ): Alvaro Barbieri, Alvise Andreose: Il Milione veneto: ms. CM 211 della Biblioteca civica di Padova . Marsilia, Venice 1999, ISBN 88-317-7353-4 .

- VA1 : Alvaro Barbieri: La prima attestazione della versione VA del Milione (ms. 3999 della Biblioteca Casanatense di Roma). Edizione del testo. In: Critica del testo. Volume 4,3, 2001, pp. 493-526; Alviese Andreose: La prima attestazione della versione VA del Milione (ms. 3999 della Biblioteca Casanatense di Roma). Studio linguistico. In: Critica del testo. Volume 5,3, 2002, pp. 653-666

- VA1 : Mario Pelaez: Un nuovo testo veneto del “Milione” di Marco Polo. In: Studi romanzi. Volume 4, 1906, pp. 5-65, superseded by Barbieri 2001.

-

Venetian version VB , two complete (Vb, Vl), one incomplete (fV) manuscript:

- Pamela Gennari, “Milione”, Redazione VB : edizione critica commentata. Diss.Università Ca 'Foscari, Venice 2010 (digital publication: PDF )

-

Venetian version V , Berlin State Library, Hamilton 424, closely related to the Latin version Z

- Samuela Simion: Il Milione secondo la lezione del manoscritto Hamilton 424 della Staatsbibliothek di Berlino. Edizione critica . Dissertation, Università Ca 'Foscari, Venice 2009; Revised version of the introduction: this., Note di storia bibliografica sul manoscritto Hamilton 424 della Staatsbibliothek di Berlino. In: Quaderni Veneti. Volume 47-48, 2008, pp. 99-125.

-

Latin version Z , preserved in the manuscript Toledo, Biblioteca Capitular, Zelada 49.20

- Alvaro Barbieri: Marco Polo, Milione. Redazione latina del manoscritto Z. Versione italiana a fronte. Fondazione Pietro Bembo, Milan; Ugo Guanda, Parma; 1998, ISBN 88-8246-064-9 .

-

Latin version P by Francesco Pipino da Bologna , over 60 manuscripts and numerous early prints, not yet critically edited

- Justin V. Prášek: Marka Pavlova z Benátek Milion: Dle jediného rukopisu spolu s přislušnym základem latinskym . Česká akademie věd a umění, Prague 1902. Gives the text of the manuscript Naples, Biblioteca Nazionale, Vindob. lat. 3273, with variants from two Prague manuscripts (Knihovna Pražské Metropolitní Kapituyí, G 21 and G 28) and the print from Antwerp 1484/85

- Manuscripts and older prints:

- Duke August Library Wolfenbüttel , Cod. Guelf. Weissenb. 40, fol. 7ff .: digitized version of the Wolfenbüttel digital library

- Andreas Müller von Greiffenhagen: Marci Pauli Veneti… De Regionibus Orientalibus Libri III. Cum Codice Manuscripto Bibliothecae Electoralis Brandenburgicae collati, exque eo adiectis Notis plurimum tum suppleti tum illustrati…. Georg Schulz, Berlin-Cölln 1671 (using the manuscript Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, lat. Qu. 70): digitized at the Munich digitization center, digitized at Google Books.

-

Latin version LT , Paris, BN lat. 3195, according to Benedetto contaminated the older Tuscan version (TA) with the Latin one from Pipino (P)

- Printed by Jean Baptiste Gaspard Roux de Rochelle: Peregrinatio Marci Pauli, Ex Manuscripto Bibliothecae Regiae, n ° 3195 f °. In: Recueil de voyages et de mémoires, publié par la Société de geographie. Volume I, Éverat, Paris 1824, pp. 299–502.

-

Italian version D : Giovanni Battista Ramusio: I viaggi di Marco Polo. originated using various Latin (Z, P) and Italian (VB) or Italian influenced sources, not critically edited

- Posthumous first edition: Secondo volume delle navigationi et viaggi nel quale si contengono l'Historia delle cose dei Tartari, et diuersi fatti de loro imperatori; descritta da m. Marco Polo gentilhuomo venetiano, et da Hayton Armeno. Varie descrittioni diuersi autori…. Giunta, Venice 1559 (various reprints, inter alia, ibid. 1583: digitized at Google Books ).

- Marica Milanesi: Giovanni Battista Ramusio, Navigationi e viaggi. Volume III, Einaudi, Turin 1980, pp. 9-297

-

German version VG , also referred to as DI , after the Tuscan version TB, preserved in three manuscripts (Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, cgm 252 and 696; Neustadt an der Aisch, church library 28) and two early prints (Creussner, Nuremberg 1477; Sorg, Augsburg 1481), not critically edited

- Here is the puch of the noble knight and landtfarer Marcho polo. Friedrich Creußner, Nuremberg 1477: Digitization in the Munich Digitization Center

-

German version VG3

- Nicole Steidl: Marco Polo's “Heydnian Chronicle”. The Central German version of the “Divisament dou monde” based on the Admont manuscript Cod. 504. Dissertation, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, 2008; Shaker-Verlag, Aachen 2010.

- Edurard Horst von Tscharner: The Central German Marco Polo after the Admonter handwriting (= German texts of the Middle Ages. Volume 40). Berlin 1935.

Modern translations

- Elise Guignard: Marco Polo, Il Milione. The wonders of the world. Translation from old French sources and afterword . Manesse, Zurich 1983, ISBN 3-7175-1646-9 ; Reprinted by Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt a. M./Leipzig 2009 (= island taschenbuch . Volume 2981), ISBN 978-3-458-34681-4 (based on the Franco-Italian version F in the edition by Benedetto, supplemented in brackets by those passages from the Latin version Z, which Benedetto mentions in the notes)

-

Henry Yule : The Book of Ser Marco Polo, the Venetian, concerning the kingdoms and marvels of the East. in 3 issues and an additional volume:

- Newly translated and edited, with notes. 2 volumes, John Murray, London 1871 (online version in the Internet Archive: Vol. I , Vol. II ).

- Second edition, revised. John Murray, London 1875 (online version in the Internet Archives: Vol. I , Vol. II ).

- Third edition, revised throughout in the light of recent discoveries by Henri Cordier. John Murray, London 1903 (online version in Internet Archives: Vol. I , Vol. II ).

- Henri Cordier: Ser Marco Polo. Notes and addenda to Sir Henry Yule's edition, containing the results of recent research and discovery. John Murray, London 1920 (online version in the Internet Archive: [1] ).

literature

- Laurence Bergreen: Marco Polo. From Venice to Xanadu. Quercus, London 2009, ISBN 978-1-84724-767-4 .

- Detlef Brennecke (ed.): The description of the world. The journey from Venice to China 1271 - 1295 (= The 100 most important discoverers. ) 3rd edition, Erdmann, Wiesbaden 2016, ISBN 978-3-86539-848-2 .

- Alfons Gabriel : Marco Polo in Persia. Typographische Anstalt publishing house, Vienna 1963.

- John W. Haeger: Marco Polo in China? Problems with internal evidence. In: The bulletin of Sung and Yüan studies. No. 14, 1978, pp. 22-30.

- Henry Hersch Hart: Venetian Adventurer. Marco Polo's time, life and report. Schünemann, Bremen 1959.

- Stephen G. Haw: Marco Polo's China: A Venetian in the realm of Khubilai Khan (= Routledge Studies in the Early History of Asia. Volume 3). Routledge, London 2006, ISBN 0-415-34850-1 .

- Dietmar Henze: Marco Polo . In: Encyclopedia of the explorers and explorers of the earth . Volume 4, Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, Graz 2000, ISBN 3-201-01710-8 , pp. 164–387.

- Katja Lembke , Eugenio Martera, Patrizia Pietrogrande (eds.): Marco Polo. From Venice to China (book accompanying the exhibition from September 23, 2011 - February 26, 2012 in the Lower Saxony State Museum in Hanover) Wienand, Cologne 2011, ISBN 978-3-86832-084-8 .

- Philippe Menard: Marco Polo. The story of a legendary journey Primus, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-89678-812-2 .

- AC Moule & Paul Pelliot : Marco Polo. The Description of the World. Routledge, London 1938 Digitized

- Marina Münkler : Marco Polo. Life and legend (= CH Beck Wissen Bd. 2097). Beck, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-43297-2 limited preview in the Google book search

- Marina Münkler: Experience of the foreign. The description of East Asia in the eyewitness accounts of the 13th and 14th centuries. Akademie-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-05003-529-1 , Berlin 2000, p. 102 ff. Limited preview in the Google book search

- G. Orlandini: Marco Polo e la sua famiglia , Venice 1926 (excerpt from the Archivio Veneto-Tridentino, Volume 9)

- Anja Overbeck: Literary scripts in Eastern France. Edition and linguistic analysis of a French manuscript of Marco Polo's travelogue (Stockholm, Kungliga Biblioteket, Cod. Holm. M 304), Kliomedia, Trier 2003 ISBN 3-89890-063-0

- Igor de Rachewiltz: Marco Polo Went to China. In: Central Asian Studies. Volume 27, 1997, pp. 34-92.

- Hans-Wilm Schütte: How far did Marco Polo get? Ostasien-Verlag, Gossenberg 2008, ISBN 978-3-940527-04-2 .

- Hans Ulrich Vogel: Marco Polo was in China: new evidence from curencies, salts and revenues (= Monies, markets and finance in East Asia. Volume 2). Brill, Leiden u. a. 2013, ISBN 978-90-04-23193-1 .

- Frances Wood: Marco Polo didn't get to China . Secker & Warburg, London 1995, ISBN 3-492-03886-7 .

- Yang Zhijiu 杨志 玖: Make Boluo zai Zhongguo马可波罗 在 中国 [= Marco Polo in China]. Tianjin 1999, ISBN 7-310-01276-3 .

- Alvise Zorzi : Marco Polo - a biography. Claassen, Hildesheim 1992, ISBN 3-546-00011-0 . (Italian original edition, Milan 1982)

Fiction

- Italo Calvino : The invisible cities, newly translated by Burkhart Kroeber, Hanser, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-446-20828-5 - fictional dialogue between Marco Polo and Kublai Kahn.

- Willi Meinck , Hans Mau: The strange adventures of Marco Polo (= Marco Polo. Volume 1). 1st edition, Kinderbuchverlag, Berlin 1955.

- Willi Meinck, Hans Mau: The strange travels of Marco Polo = The strange travels of Marco Polo (= Marco Polo. Volume 2). 1st edition, children's book publisher, Berlin 1956.

- Oliver Plaschka : Marco Polo: To the end of the world. Droemer, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-426-28138-3 .

bibliography

- Nota Bibliografica. In: Vito Bianchi: Marco Polo. Storia del mercante che capì la Cina. Laterza, Rome 2007, ISBN 978-88-420-8420-4 , pp. 331-351.

Documentation

- Marco Polo - Explorer or Liar? . Terra X , on: ZDF from June 7, 2015.

- Marco Polo Reloaded - followed by Bradley Mayhew - presented by SWR and Arte in 2011.

Web links

- Literature by and about Marco Polo in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Marco Polo in the German Digital Library

- Publications on Marco Polo in the Opac of the Regesta Imperii

- Carlo Errera: POLO, Marco. In: Enciclopedie on line. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 1935.

- Johannes Paul : Marco Polo: Ins Reich des Groß-Khan , biography from: Adventurous Journey through Life - Seven biographical essays , page 15-66, Wilhelm Köhler Verlag, Minden, 1954

- Igor de Rachewiltz: F. Wood's Did Marco Polo Go To China? - A Critical Appraisal by I. de Rachewiltz ( Memento of April 22, 2000 in the Internet Archive ) at rspas.anu.edu.au (Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies)

- Marco Polo - the first great travel reporter ( Memento from February 6, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- Itineraries of the polos

- Hans Ulrich Vogel: Suspicion of plagiarism against Marco Polo invalidated on Spektrum.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ Laurence Bergreen: Marco Polo: From Venice to Xanadu. Alfred A. Knopf, New York 2007. For the year of birth 1254 see p. 25. For the date of death, p. 340. January 8 is the date of the will that was signed by the doctor and notary Giovanni Giustiniani, but not by himself provided with its sign (tabellionato). Maybe he was too weak to be signed and died soon after.

- ^ Igor de Rachewiltz: F. Wood's Did Marco Polo Go To China? A Critical Appraisal , Australian National University ePrint, September 28, 2004 ( online version ).

- ^ Christopher I. Beckwith : Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present . Princeton University Press 2009, ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2 , p. 416 ( excerpt in Google book search). Denis Twitchett, Herbert Franke: The Cambridge History of China: Alien regimes and border states, 907-1368 . Cambridge University Press 1994, ISBN 0-521-24331-9 , p. 463 ( excerpt in Google book search).

- ↑ Bergreen, Marco Polo, Knopf 2007, p. 25

- ↑ Laurence Bergreen, Marco Polo, Knopf 2007, p. 24

- ↑ Laurence Bergreen: Marco Polo , Knopf 2007, p. 24. “Although complete agreement on the origins of the family is lacking, one tradition suggests that the Polos migrated from the Dalmatian town of Sebenico to the Venetian lagoon in 1033. At various times , Sebenico was ruled by Hungarians and Croatians, and it would later join the Venetian empire. Another tradition holds that Marco Polo was born on Curzola , the island where he would later be captured by the Genoese, while a third asserts that Polos had been entrenched in the Venetian lagoon prior to all these events. " ( Excerpt (Google) )

- ^ Johannes de Plano Carpini: Liber Tartarorum. and Ystoria Mongolorum quos nos Tartaros appelamus ; Wilhelm von Rubruk: Itinerarium Willelmi de Rubruc (in the form of a letter to the French king)

- ^ Elise Guignard: Marco Polo, Il Milione. The wonders of the world. Frankfurt a. M. / Leipzig 2009, Chapter IX, p. 15.

- ^ Elise Guignard: Marco Polo, Il Milione. The wonders of the world. Frankfurt a. M. / Leipzig 2009, Chapter XI, p. 17.

- ^ Elise Guignard: Marco Polo, Il Milione. The wonders of the world. Frankfurt a. M. / Leipzig 2009, Appendix Geographical Names , p. 430.

- ^ Elise Guignard: Marco Polo, Il Milione. The wonders of the world. Frankfurt a. M. / Leipzig 2009, Chapter XIII, p. 18.

- ↑ a b c d TV documentary (ZDF, 1996) by Hans-Christian Huf "The fantastic journeys of Marco Polo"

- ^ International Columbus Exhibition in Genoa 1951 . In: Universitas . tape 6 , no. 2 , 1951, p. 825-827 .

- ↑ The tradition of names varies. Rustichello appears, for example, as “Rustico da Pisa” in Marco Polo's Travels. Translated into German from the Tuscan 'Ottimo' version from 1309 by Ullrich Köppen. Frankfurt 1983, p. 19.

- ↑ compare the entries for Oct. 21 and Nov. 1, 1492 in the logbook of the 1st trip In: Robert H. Fuson (Hrsg.): Das Logbuch des Christoph Columbus Lübbe, Bergisch Bladbach 1989, ISBN 3-404-64089- 6 , pp. 156, 170.

- ↑ Robert H. Fuson (ed.): The log book of Christopher Columbus. P. 60.

- ↑ a b Tucci, Marco Polo, in: Lexikon des Mittelalters , Metzler, 1999, Volume 7, Sp. 71/72

- ^ Testament of Marco Polo, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana ; Cod. Lat. V 58.59, collection. 2437, c. 33 (ed. By E. A. Cicogna, Delle Iscrizioni Veneziane III, Venice 1824 ff., 492)

- ^ Marcello Brusegan : I Palazzi di Venezia . Roma 2007, p. 299

- ^ Marina Münkler: Marco Polo. Life and legend ( an introduction to the complexity, complexity and difficulty of Marco Polo research ), C. H. Beck Wissen, Munich 1998, ISBN 978-3-406-43297-2 , p. 97.

- ↑ Marina Münkler: Experience of the Stranger. The description of East Asia in the eyewitness accounts of the 13th and 14th centuries. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-05-003529-3 , p. 265 ( limited preview in the Google book search); quoted by her from Benedetto's edition of Milione (S. CXCIV)

- ^ Antonio Manno: The Treasures of Venice (Rizzoli Art Guide). Rizzoli International Publications, New York 2004, ISBN 978-0-8478-2630-8 , p. 254.

- ↑ Minor Planet Circ. 45343

- ↑ The world traveler and his book , on gaebler.info

- ↑ Marco Polo: “The wonders of the world” , on deutschlandfunk.de, accessed on July 5, 2019

- ↑ a b Barbara Wehr: Portrait , on staff.uni-mainz.de

- ↑ http://www.chinapur.de/html/namen_auf_chinesisch.html , accessed December 29, 2010.

- ↑ See for example Francis Woodman Cleaves: A Chinese source bearing on Marco Polo's departure from China and a Persian source on his arrival in Persia. In: Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. Volume 36, Cambridge Mass 1976, pp. 181-203, here: p. 191.

- ^ John W. Haeger : Marco Polo in China? Problems with internal evidence. In: The bulletin of Sung and Yüan studies. No. 14, 1978, pp. 22-30. ( as a PDF file ( Memento from June 10, 2011 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ Frances Wood: Did Marco Polo go to China? London 1995. (German edition: Frances Wood: Marco Polo did not get to China . Piper, 1995, ISBN 3-492-03886-7 ).

- ↑ Frances Wood (see literature), pp. 190 f.

- ↑ See, for example, the work of Igor de Rachewiltz, Laurence Bergreen or Yang Zhi Jiu, see literature .

- ↑ Athanasius Kircher: China monumentis… illustrata. Amsterdam 1667, p. 90a ( digitized at Google Books ): “vehementer miror, Paulum Venetum nullam murorum Sinensis Imperii, per quos necessario transire debebat, mentionem fecisse” (“I am extremely surprised that the Venetian Polo built the walls of the Chinese Empire at all not mentioned, which he had to cross on his way ")

- ^ "Had our Venetian really been on the Spot, with those Advantages he had of informing himself, how is it possible he could have made not the least Mention of the Great Wall: the most remarkable Thing in all China or perhaps in the whole World ? ", Quoted from Folker Reichert, Chinas Große Mauer , in: Ulrich Müller, Werner Wunderlich, Ruth Weichselbaumer (Eds.), Burgen, Länder, Orte , UVK, Konstanz 2007 (= Mythen des Mittelalters, 5), p. 189– 200, p. 195

- ^ Arthur Waldron, The problem of the Great Wall of China. In: Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 43, 2, pp. 643-663 (1983); ders., The Great Wall of China: from History to Myth. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge u. a. 1990, ISBN 0-521-42707-X .

- ^ Igor de Rachewiltz: F. Wood's Did Marco Polo Go To China? A critical appraisal. ePrint of the Australian National University, September 28, 2004 ( online ), points 4 & 5

- ↑ For example here: Chih-chiu Yang, Yung-chi Ho: Marco Polo Quits China. In: Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 9 (1945), p. 51. It should be noted that the current spelling of his name in Pinyin is different than in 1945.

- ↑ Yang Zhi Jiu: Makeboluo zai Zhongguo. = Marco Polo in China. 1999, chapter 15.

- ↑ In his book "Makeboluo zai Zhongguo" (see literature ) Yang has attached a photocopy of this excerpt

- ↑ cf. Francis Woodman Cleaves' article in Note 20 in the Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies .

- ↑ cf. also de Rachelwitz, point 8 of his reply to Wood, in: F. Wood's Did Marco Polo Go To China? - A Critical Appraisal by I. de Rachewiltz ( Memento from April 22, 2000 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ John H. Pryor: Marco Polo's return voyage from China: Its implication for 'The Marco Polo debate'. In: Geraldine Barnes, Gabrielle Singleton: Travel and Travelers from Bede to Dampier. Cambridge 2005, pp. 125–157, here: pp. 148–157, chapter "The return voyage"

- ↑ Marco Polo was not a swindler - he really did go to China . In: University of Tübingen , Alpha Galileo, April 16, 2012. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved on May 25, 2012.

- ↑ Marco Polo New in the cinema. Film details on page

- ↑ Marco Polo Film Lexicon from TV SPIELFILM

- ↑ Review by E. Léonard , Bibliothèque de l'École des chartes, Volume 87, 1926, pp. 398-399

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Polo, Marco |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Venetian trader, traveler, writer and explorer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1254 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Venice , Italy |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 8, 1324 |

| Place of death | Venice , Italy |