Ship's cat

Ship's cat (also on- board cat , more rarely boat cat ; male form: ship's cat , on- board cat ) is the name for a house cat that travels on a ship or barge, decimating pests such as rats and mice in storage rooms and galleys and / or as a mascot for entertainment Serves distraction for the crew.

Until around the 1970s, cats were often found on war and merchant ships. Today the captain determines whether the presence of a ship's cat on his ship is desirable and can be tolerated.

In connection with particularly well-known ships, people or events in history, ship cats were mentioned or depicted in writing and thus became known. In the travel literature one finds their description especially in the 18th and 19th centuries and children's books about ship cats thematically combine animal history and travel adventures.

Origins and early mention

A genetic study of mitochondrial DNA from cats suggests that house cats were domesticated in the Middle East about 9,000 years ago and then spread through marine and terrestrial trade routes. It is assumed that there could have been catfish on Egyptian and Phoenician ships, but this has not yet been confirmed by specialist Egyptological literature. Graphic representations show that in Egypt cats - despite their special position as venerable or even sacred animals - were used on boats to hunt waterfowl, but these are "family cats" and not "ship cats" in the true sense.

On Portuguese ships there were cats and dogs . Vasco da Gama reported in 1503 that he had traveled back from India for several months. The ships were fully loaded with merchandise, but the crew ran out of food. To survive, the two dogs and the two cats on board were slaughtered and eaten.

The Spaniards also usually carried cats with them on their voyages and when the Mayflower crossed in 1620 there was at least one cat on board.

Domestic cats spread to Europe in part via shipping lines in the Mediterranean, and geneticists attribute the relative genetic homogeneity of today's domestic cats in Europe and the Middle East to the cats on these ships.

According to genetic analyzes, the American Maine Coon cat has Scandinavian forest cats ( skogkatt ) among its ancestors. Vikings have been shown to keep this species of cats, and it is believed that they may have got to America on their ships.

That it used to be widespread, cats to curb rat and mouse populations whose uncontrolled proliferation brought hygienic and nutritious technical disadvantages in the maritime use, the spread is the term ship's cat in the vocabulary of many nations, a war - and Merchant Marine had : skibskat ( Danish ), ship's cat ( English ), chat du bord or chat de navire ( French ), 船 の 猫 ( Japanese ), gato de navio ( Portuguese ) etc.

Decrees, edicts, regulations

Various decrees, edicts and regulations allow an assessment of the importance of ship cats in the corresponding centuries.

In the Black Book of the Admiralty , a rule book for all matters relating to shipping, which goes back to the old French texts of the Rôles d'Oléron (around 1160 to 1286), according to Bluhm, there is the statement that ship owners had to be liable for goods damaged by rats if there was no cat on board the affected merchant ship.

The Scottish King Alexander II issued a decree in the 13th century after a stranded ship remained in the possession of the owner for so long and could not be regarded as an abandoned, released shipwreck as long as there was a living man, a living dog or a living cat found, whereby on-board dogs and ship cats were of particular importance with regard to the right of ownership of the ship owner.

Jean-Baptiste Colbert , French statesman and founder of mercantilism , insisted in the 17th century that commercial contracts should mention that there were two cats on board - otherwise the ship would not be fit for travel.

The Austro-Hungarian Navy had "official ship cats" whose keeping on board was covered by their own budget.

For reasons of hygiene and rabies prevention , the Royal Navy banned cats from ships in 1975, thereby ending a centuries-old tradition.

Superstition

As with the house cat on land, there was also superstition at sea with regard to the ship cat , which mainly revolved around its role as a team mascot and good luck charm . In addition to the examples listed here, there are other anecdotes and references to superstition at Bluhm.

- A cat on board was seen as a good luck charm and was therefore "as sacred as the bull in Egypt". John Locke tells of an incident in which a ship's cat fell into the sea and a boat with half a dozen men was abandoned to rescue her while the ship stopped in motion. Locke also suspected that a crew member who went overboard would have made less fuss.

- This may be related to the superstition that a ship's cat that went overboard and was not rescued was able to cause a storm that would damage the ship and the careless crew.

- Likewise, deliberate mistreatment of the ship's cat leads to misfortune for the crew.

- The cat's routes were also given importance: if it moved towards a seaman, it “brought” him luck; if she moved away from him, luck took her with her again; if it crossed his path and moved away from him, he was probably doomed.

- In the Royal Navy, a black cat on board was considered a lucky charm ; two black cats, however, brought bad luck .

- It is said from Wales that there should be storms when a ship's cat stretches and stretches so that its front paws touch before the ship , coming from the Bristol Channel , reaches Lundy .

- According to rumored stories, a ship's cat who voluntarily left her ship seemed to mean the imminent sinking of that ship.

Mentions of ship cats

Mention before the 18th century is rare. Bluhm attributes the fact that no ship's cats are mentioned in the official records of Christopher Columbus , for example, to the fact that cats were already so natural on ships at this time that their mention would have been trivial. The omission of Trim (see below) in Matthew Flinders' official reports could be based on similar reasoning .

In the following, stories of well-known ships and special events are summarized in which ship cats were perceived as exposed and mentioned in writing and thus also became known.

15th century

The cat in the junk

When a junk loaded with porcelain and ceramics , which sank in the South China Sea off Hội An around 1450 , was recovered and examined in 1996, skeletal remains of rats were found in the hull and the skull of one in the rear section, where the galley was Cat. According to Detlef Bluhm's assumption, this find is likely to be the earliest direct archaeological evidence of a ship's cat.

18th century

The ship's cat that saved Peter Bull's life

In his book Hamburg stories (1916), Otto Beneke reports on a ship's cat that saved the life of pilot Peter Bull from Cuxhaven in 1736 . The three-master of the skipper Franzen had run into a sandbank in the Elbe estuary near Neuwerk . The crew blamed the pilot for the accident and pulled out their knives. The level-headed captain was able to prevent the murder, but there was no room for the pilot in the lifeboat. This tied himself to the capstan and confided in the sea. At the last moment the ship's cat jumped on his head and clutched his hair. After hours the spill drifted near the Kugelbake at Döse and Bull saw two men on the dike, but could not make himself noticeable to them because of exhaustion. But the cat managed to do this with its ever louder meowing. After the rescue, Peter Bull kept the cat with him until it died.

Cats on the ships under James Cook

Since Johann Reinhold Forster had a reputation as a scientist, he received in 1772 the offer of the British Admiralty , Captain James Cook to accompany on his second circumnavigation. Forster ensured that his only 17-year-old son, who would later become a natural scientist and travel writer Georg Forster , was allowed to come along as a draftsman.

Georg Forster made notes from the period from 1772 to 1775, in which he describes the cats of the Resolution and the escort ship, the HMS Adventure , who were on this trip: In Dusky Bay , New Zealand , the familiarity of the smaller birds was evidence of this Forster, " that this part of the country has probably not yet suffered any change in people ". Then he reports on the consequences: “ But in a few days it [the innocent audacity of the birds] became very detrimental and pernicious for them, because a cat from our ship had not found out so soon that this was such a wonderful opportunity for a wonderful meal hey, when she really went for a walk in the wood every morning, and caused a terrible defeat among the little birds, which were not wary of such a deceitful enemy because they suspected nothing wrong of him. "

There must have been a whole cat population on Cook's ships, because about 20 cats were given to the natives on Otaheite and some of these animals were also given away on Ulietea and Huaheine .

Forster reports that the curiosity and attention that the islanders showed the ship's cats went so far that several cats were stolen on Tonga . Two or three of the thieves were caught and flogged.

Pandora's cat

The HMS Pandora was dispatched by the British Admiralty under the command of Captain Edward Edwards in 1790 to capture the mutineers of the Bounty . On the way back, the frigate ran into a coral reef on August 29, 1791 and had a leak. Crew members who had survived the sinking returned to the Pandora the next day by boat under the direction of Captain George Passmore , of which only the upper deck and masts protruded from the water. What could still be salvaged were the upper part of the bridle bar , parts of the rigging , the chain of the lightning rod - and the ship's cat that had saved itself on the spreader . The further fate of Pandora's ship's cat is unknown.

In a painting that William Tobin is attributed and possibly a sketch of a midshipman of Pandora , George Reynolds, based, you can admire the ship's cat of Pandora discover the detail.

19th century

Probably the best known and most literarily honored ship's cat at the beginning of this century was the tomcat Trim.

At the end of the 19th century, ship cats - for example on American warships - have been extensively documented.

Trim

Trim, a black tomcat with white paws, chest and chin, was born on the research ship HMS Reliance in 1799 and became a companion and friend of the ship's commander and explorer Matthew Flinders (1774-1814).

In his book A Voyage to Terra Australis , Flinders makes no mention of his ship hangover, but as early as December 1809 Flinders had written A Biographical Tribute to the Memory of Trim , which was only found in 1973 in the archives of London's National Marine Museum. This contemporary-historical document is considered to be "unique" in its detailed description (see below).

Trim showed himself to be very adventurous and playful from the beginning, whereby he went overboard as a young animal in a harbor, but was able to stay afloat until a rope was held out to him, which he climbed with ease. Due to his trustworthiness, he quickly became the favorite of the team, at whose meals he took part and asked for something from each plate in turn, whereby he was mostly just as discreet as it was skillful - and grew into a stately tomcat.

With Flinder's travels from 1801 to 1803 to map the coast of Australia , Trim became the first domestic cat to be known to circumnavigate Australia by ship. On these mapping trips Trim shared his special friendship not only with Flinders, but also with the Aboriginal Bungaree (1775-1830), who was on board as translator and negotiator, and William, the steward of the junior officers' mess. In the storage rooms on board, the tomcat proved himself to be a skilful and relentless pied piper and he also instilled the necessary respect with the dogs on board the HMS Investigator with claws and teeth. If you follow Flinder's story, Trim was only comfortable at sea. When staying in the country, such as in a guest house in Deptford near London , Flinders soon had to pick up his cat again because he had caused a mess there.

On the night of August 17, 1803, the HMS Porpoise ran aground at the Wreck Reefs and the crew had to wait two months for rescue ships. Even during this difficult time Trim behaved in an exemplary manner, and when the majority of the crew members decided to continue on a larger ship to China , Trim Flinders followed the East Indiaman Cumberland , who next docked on the island of Mauritius . There the entire team was taken to prison under the pretext of espionage: France and England had once again become opponents in the coalition wars, which the Cumberland team did not know. Trim didn't like this imprisonment and kept sneaking out of prison. When the prisoners were transferred to the Maison Despeaux, Flinders agreed, assuming "that this would not offend His Excellency the French Governor of Mauritius," when a French woman offered him to take Trim in as her little daughter's playmate .

But within two weeks Trim was gone. Even a reward of "ten Spanish dollars" in the island newspaper was unsuccessful. Flinder's guess was "that this extraordinary, trusting animal had been cooked and eaten by a hungry black slave."

Flinders failed to keep his promise to erect an epitaph for his ship's tomcat and friend Trim , but in 1996 a Trim bronze sculpture was made by John Cornwell, which is at the Mitchel Library in Sydney; the library café was also named after Trim. In addition, there is a statue of Flinders together with Trim in Flinders birth town Donington (Lincolnshire) and a life-size bronze sculpture showing Flinders surveying with Trim was unveiled on July 19, 2014 by Prince William at Australia House in London. The sculpture is now in Euston Station in North London, the area where Flinder's grave is believed to be. Another statue was unveiled in Port Lincoln in 2017 by South Australian Governor Hieu Van Le .

Trim has also been described several times in literature.

Bouchiq

Jacques Boucher de Perthes , the customs inspector and in this capacity also the commanding officer of a small squadron of sloops for the coast guard, documents in his biography from 1861 the story of Bouchiq, the Voltigeur's on- board cat , and refers to their log books . The Voltigeur was at that time the parade ship not only the squadron, but the entire Breton coast guard and "could even the Argo gouged".

Bouchiq was before the launch of voltigeurs brought as little kitten on the ship and became a favorite of the crew. When the old captain disembarked after 10 years, the second mate who did not like the cat became the new captain and at the first opportunity he threw the cat overboard at night. The crew heard the process, but nobody saw that Bouchiq could save himself and then secretly climbed back on board. The next morning, the team celebrated the "resurrection" of Bouchiq, who was enthroned in the crow's nest . But the new captain was determined to get rid of the cat and, amid the protests of the crew, abandoned Bouchiq on a deserted beach 20 miles from Tréguier's home port .

In a nautical competition that followed soon after, in which another victory was expected, the Voltigeur only came fourth. It was assumed that the cause was minor problems that were repaired, but the Voltigeur could no longer be maneuvered as it used to. The rigging and ballast were also changed, and finally a priest who had been in Rome was even brought in, but all without success. When the captain was at the end of his game, he called a team meeting. An old sailor, who had been silent until now, finally said what the crew thought: The Voltigeur would “buck” because the cat, with whom she had been with “since she was born”, had disappeared. In order to refute the old man's statement, the captain called him an old fool, but the crew stood behind the old man and "bucked" for days at work, just like their ship.

Finally the captain gave in: Bouchiq should be brought back on board, but he did not know where to find her. The old man told him that Bouchiq was experienced and that she had definitely found her way back to her home port. The captain voiced his doubts about the cat's intelligence, but again the crew agreed with the old man.

Again the captain tried to assert himself and decided that a Bouchiq-like cat could be found for the Voltigeur . And for the third time the old man opposed: You can't deceive a ship as easily as a person. The voltigeur only wanted Bouchiq, otherwise a disaster would happen.

While the Voltigeur was anchored in Roscoff , Bouchiq had indeed found his way to Tréguier after adventure and injury, where everyone knew the Voltigeur's cat . Her condition, the lonely return and her plaintive meowing in the harbor while searching for her ship could only mean one thing: the Voltigeur had sunk , the crew had drowned and only the animal had been able to save itself as the only survivor on a plank on the bank. The supposed widows and orphans ran through the town weeping and wailing.

The next day and the day after that there was no sign of life from the Voltigeur . On the third day they were preparing to read mass for the dead when Bouchiq hurried in long sentences towards the port; half an hour later the voltigeur entered there. As soon as the ship had touched the quay wall, Bouchiq jumped on board to the cheers of the crew - and even of the captain, who now seemed convinced.

From that day on everything was as it was before: the ship won every race and even later, at the age of 15, Bouchiq was still as lively as on his first day on the Voltigeur .

Nansen

Nansen was the ship's cat on the Belgica , which was used for the Belgian Antarctic expedition from 1897-1899 under the direction of Adrien de Gerlache de Gomery . It had been brought on board by the cabin boy Johan Koren and was named after the polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen . The second officer was Roald Amundsen , who was still unknown at the time, and noted in his diary that Nansen crept around the deck, especially at night, and was very skilled at catching flying fish . Ship cat Nansen died on June 22, 1898 in Antarctica.

Peter

Peter was the ship's cat of Helgoland , a fishing steamer with which the German expedition to the Arctic Ocean in 1898 Spitsbergen rounded. Theodor Lerner , who had organized the trip under the direction of the zoologists Fritz Römer and Fritz Schaudinn , reports that Peter came on board as a "gift of love from a tender hand" when he left Germany. The abundant consumption of reindeer, bear and seal meat made it a splendid specimen. During a storm he was hit by an overcoming sea and thrown overboard in a high arc. The crew had already given him up when a new sea carried him back on board minutes later, where he hastily climbed onto the roof of the wheelhouse.

20th Century - The time before World War II

At the beginning of the 20th century, ship cats were mostly mentioned in connection with adventurous expeditions or with actions of the navy during the First World War . During the First World War in particular, it was common to photograph the ship's cat (s) in the barrel of one of the ship's cannons.

Kiddo

Kiddo had got on the airship America as a stowaway before it took off on October 15, 1910 from Atlantic City (New Jersey) to attempt an Atlantic crossing . The "airship cat" was initially unpleasantly surprised by its situation and mewed incessantly, so that the crew and chief engineer Melvin Vaniman wanted to get rid of it. For this purpose, the radio operator of America made the first radio message sent from an airship to a ground station: "Roy, come and pick up this goddamn cat." They tried to rappel Kiddo in a sack from the airship to a motorboat, but because of that Swell did not succeed. Kiddo stayed aboard the airship, settled in, and was apparently more accurate than the barometer at predicting bad weather .

When the machines of America began to fail after 71½ hours and about 475 nautical miles east of the coast of Maryland and the Royal Mail Ship Trent was discovered, the small crew gave up the airship and they switched to lifeboats. The fact that the American journalist, researcher and aviator Walter Wellman (1858–1934), who planned and carried out this daring experiment with the America , "took" a cat with him, which then also scratched people in the boat during the rescue injured, was dealt with in two newspaper articles - one serious, the other humorous.

Since Kiddo's short career as a "ship's cat" came to an end, she was henceforth looked after by Edith Wellman Ainsworth, the daughter of Walter Wellman.

nigger

Nigger was Robert Falcon Scott's (1868–1912) black cat on his Terra Nova expedition (1910–1913). The little tomcat must have sneaked on board before June 1910, when the Terra Nova was still at anchor in London , and became the crew's mascot. Nigger fell overboard at least twice, but always got rescued.

Petty Officer Frank Browning made him his own little hammock with a blanket and pillow that niggers learned to use too. It is reported that niggers were sleeping in that hammock when Admiral Sir Richard Poore, Commander of the Royal Navy's Australia Station, came aboard the Terra Nova for an inspection . When Sir Poore tried to wake the cat, nigger ignored the distinguished visitor. After a quick look he yawned, stretched and closed his eyes again - which should have amused the admiral very much.

Weddell seals were shot in the Antarctic to feed the crew, and niggers developed a great fondness for bubblers , which he usually ate so much that he vomited - whereupon he ate even more bubblers.

Nigger never saw the end of the trip. On the way back the ship got caught in a storm in the English Channel and nigger was washed into the sea by a wave. A boat was lowered, but the Terra Nova's hangover could no longer be found.

Lisbeth

Lisbeth was the ship's cat of the steamer Mainz of the Zeppelin study expedition to Spitzbergen in the summer of 1910. The white cat with its two lively babies was the “symbol of cheerful domesticity and comfort on board”. The boys got their daily bowl of milk from Prince Heinrich of Prussia , the brother of the German Emperor Wilhelm II. To the chagrin of the zoologist Otto von Zedlitz and Trützschler, on their nocturnal forays, Lisbeth ate his bird preparations, especially the rare and valuable snipe birds, sandpipers and ptarmigan.

Jenny

Jenny was the ship's cat of the RMS Titanic , who is mentioned in the records of several survivors of the fateful maiden voyage (April 10-14, 1912). She was originally the ship's cat of the Titanic's sister ship , the RMS Olympic , which collided with the British cruiser HMS Hawke in September 1911 .

A week before the Titanic left Southampton , Jenny had a litter of kittens. They mostly stayed in the kitchen of the Titanic , where they were fed by the staff with kitchen waste. Stewardess Violet Jessop later wrote in her memoir, "The cat had her family close to Jim, the kitchen boy whose approval she always sought and who always showed her warm affection."

The popular story that a stoker (or kitchen boy) named Jim Mulholland saw Jenny bring her boys ashore one by one in Southampton down the gangway (which kept him from starting his work on the Titanic ), has proven to be incorrect.

Jenny and her boys stayed on board and went down with the Titanic on April 14, 1912 .

Nigeraurak

Nigeraurak ( the little black one ) was the ship's cat on the HMCS Karluk during the Karluk expedition (1913-1914) led by Vilhjálmur Stefánsson , which wanted to explore the areas west of the Queen Elizabeth Islands . The kitten was not yet a year old and was adopted by the stoker Fred Maurer (1893–1923), who considered it his property.

The youngest member of the expedition was the Yupik girl Mugpi from Point Barrow (later Ruth Makpii Ipalok; 1911-2008). Since Mugpi's way of playing with the cat was a bit rougher, she had a lifelong scar on her chin caused by Nigeraurak's claws.

When the Karluk, surrounded by ice, leaked and sank on January 11, 1914, Nigeraurak was evacuated in a sack, as orders had been given to save the animals too. Nigeraurak survived the march across the pack ice of the Beaufort Sea and seven months of hardship on Wrangel Island . After the shipwrecked were rescued in September 1914, she stayed with Maurer and eventually survived him. She became the mother of many black and white kittens, all named Karluk.

Emmy

Emmy was the ship's cat on the Royal Mail Ship Empress of Ireland . She was an orange tabby cat who never missed a trip. But on May 28, 1914, Emmy disembarked the ship. The crew could not lure them back in time and the Empress of Ireland left port without them. Emmy was reportedly last seen on the roof of a shed at Pier 27, where she is said to have watched her ship leave Quebec City .

Early the next morning, the Empress of Ireland collided in the fog with the SS Storstad in the mouth of the St. Lawrence River and sank quickly thereupon, killing more than 1000 people.

Mrs. Chippy

Mrs. Chippy was the cat on board the Endurance , Sir Ernest Shackleton's ship on his Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition (1914–1917). When the ship caught in the pack ice had to be abandoned in early 1915, Shackleton had the sled dogs and Mrs. Chippy shot because he had decided that the animals could not be afforded during the arduous journey across the ice.

20th Century - World War II and after

Although there were isolated stories of famous seafarers' ship cats even before the 20th century, the outbreak of World War II was due to the commitment of the national naval forces as well as the rapid increase in the spread of news through newspapers, radio and television, especially in the English-speaking world to a new "celebrity" of ship cats.

Rinda

Rinda was the ship's cat on the Norwegian cargo ship of the same name, which was torpedoed and sunk off the coast of Liberia on May 30, 1941 . After a long search, the cat was rescued by the trawler HMT Pict together with the crew members and stayed on board the Pict , where it was given the name Rinda in memory of the ship that was sunk.

Oscar / Unsinkable Sam

The history of the Bismarck's cat on board contains alternative variations and is fraught with many questions compiled by Frank Allen of the HMS Hood Association .

A hangover, name unknown, is said to have been on the German battleship Bismarck when it was sunk on May 27, 1941, with only 116 of the more than 2,104 crew members surviving. The British destroyer HMS Cossack is said to have found this cat floating on a plank and picked it up. On October 27, 1941, the Cossak was torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine, but the cat, now named Oscar, is said to have been rescued again and brought to Gibraltar . According to this, Oscar is said to have become a hangover on the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal , which was torpedoed off Gibraltar on November 13, 1941 and sank. Oscar said to have been saved again, but was now on land in the office buildings of the Governor General of Gibraltar under the name Unsinkable Sam ( Unsinkable Sam held). After all, he is said to have been brought to England, where he spent the rest of his life in a seaman's home until his death in 1955. An alleged portrait of the cat hangs in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, but shows a tabby cat, while other reports describe Oscar as a "black cat with a white collar."

Blackie / Churchill

Blackie was the cat on the Prince of Wales . During the Second World War , he achieved worldwide fame through a press photo after the Prince of Wales had brought then Prime Minister Winston Churchill across the Atlantic to the NS Argentia naval base in Newfoundland , where he spent several days with the then US President Franklin D. Roosevelt in a safe environment. This meeting led to the signing of the Atlantic Charter .

When the cat lover Churchill was about to leave the Prince of Wales after negotiations were over, the cat approached him. Churchill bent down to say goodbye to Blackie (or to prevent him from leaving the ship with him) and at that moment the picture was taken which later appeared in the world's press. In honor of the successful visit, Blackie was renamed "Churchill".

Blackie survived the sinking of the Prince of Wales later that year and was taken to Singapore with the survivors, but could not be found when Singapore was evacuated the following year. His fate is unknown.

Tarawa

The kitten Tarawa was rescued from a bunker by the United States Coast Guard during the Battle of Tarawa in November 1943 . She became the mascot of an armored landing ship. There she didn’t get on well with Kodiak, the dog on board, which is why she occasionally left the ship after returning to the USA, went ashore and disappeared.

Convoy

Convoy was the Hermione's cat . He got this name because he took part in many convoy trips on the Hermione . Convoy was duly recorded in the ship's log and had his own little hammock to sleep in. He was killed along with 87 crew members when the Hermione was torpedoed and sunk on June 16, 1942 by a German submarine (type U-205 ).

Peebles

Peebles was the ship's cat on board HMS Western Isles during World War II. She was the favorite of the ship's crew and was known for her particularly playful behavior. She greeted strangers as they entered the officers ' mess with a “handshake” (gave a paw) or “jumped through the hoop” (the arms held together in a ring) by crew members.

Free thinker

The battleship Warspite of the Royal Navy had a hangover that was born on the ship and had witnessed D-Day (June 6, 1944) and the bombing of Brest (August 25, 1944) there. In the latter case, 213 projectiles were fired from the Warspite at the German positions, which made him very frightened and led to unsanitary behavior.

This was followed by an official release of the ship's cat from duty, which was not meant to be very serious, but which was announced on the Warspite with the following words:

"An Official Service certificate, including an Honorable Discharge, has been issued on behalf of the Ship's Cat, which has left HMS Warspite owing to shell-shock and has taken up residence with the wife of a crew member A / B George Allen of Barking , Essex. "

"An official certificate of honorific Discharge has been issued regarding the ship's cat which left HMS Warspite due to the tremors of war and is now residing with the wife of crew member A / B George Allen of Barking, Essex."

The original was signed by Captain Kelsey DSO . The cat was named Ginger Brest in allusion to the bombing of Brest , and Chatham was specified as the stationing port under the official number LX. 1944. On the ship he was known as a Free Thinker and only recently had the mentions “By his actions, proved himself an example to others.” For D-Day and “On August 25, during the bombardment of the fort at Brest, he also acquitted himself in a very seamanlike manner. ”for use in front of Brest.

Rastus

Rastus was the cat on the American HMS Gorleston , which was commanded by the Royal Navy from 1941 to 1946.

In the port of Liverpool, a large seagull dared to perch and strut on the forecastle , Rastus' favorite area. After hissing and threatening gestures had no effect, Rastus attacked and bit the seagull in the leg. The frightened bird took off - together with the cat - and only above the water did Rastus loosen his bite, whereupon he fell into the harbor basin. To the cheering of the crew, Rastus swam ashore and returned to the Gorlestion . Rastus' unusual experience was retold in The Nautical Magazine in 1952 .

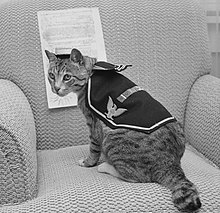

Pooli

Pooli was a ship's cat on board a US attack transport ship during World War II and was awarded three belt buckles and four service stars during this time because of the fighting he had experienced .

Felix

Felix was a cat - with his own life jacket - on board the Mayflower II when she sailed from Devon in England to Plymouth in Massachusetts in 1957, to symbolize the solidarity between Great Britain and the USA after the Second World War. When Felix broke his paw in an accident, he was treated by the ship's doctor and his paw straightened again. After the Mayflower II arrived , photos and stories of Felix appeared in the American magazines National Geographic , Life and Yankee and Felix and the ship's crew received a confetti parade in New York and toured the east coast that summer. Felix was eventually taken over by Ann Berry, the cabin boy's friend, and from then on lived in Waltham, Massachusetts .

A later Mayflower II captain wrote a children's book about him called Felix and his Mayflower II Adventures , which was published in 2007 as part of the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the ship's arrival at Plimoth Plantation .

Simon

Simon (approx. 1947–1949) was the cat of the HMS Amethyst , which was involved in an incident on the Yangtze in April 1949 during the Chinese Civil War . 25 crew members were killed and many injured, including Simon. But Simon recovered and resumed his rat fight to protect limited supplies, thereby adding to the morale of the troop. Back in the UK, Simon became a celebrity. When he died of an infection soon afterwards, he was buried with military honors in the animal cemetery in Ilford, London . An obituary appeared in The Times and he was posthumously awarded the Dickin Medal as the first and only cat to date .

Fred Wunpound (Lucky Fred)

Wunpound (referred to as Fred Wunpound in official Royal Navy documents ), black with white paws, was the ship cat of HMS Hecate (A137; stationing port Portsmouth ) for nine years . During this time he covered more than a quarter of a million nautical miles on the ship, which corresponds to about one circumnavigation of the world per year. While serving as "mouser" he was promoted from Able Seacat to Leading Seacat .

The 1974 Rabies Ordinance, which required quarantine for pets upon entry into the UK, allowed Wunpound to take early retirement, although he was not recategorized as a "shorecat" due to his merits. He died in 1976 at the age of 10, received an obituary, and was buried with military honors at sea.

It is not known whether Wunpound was really "the last ship's cat in the Royal Navy" in 1976 or whether he only became one through media attention.

21st century

Wooden construction in military and merchant ships had already been replaced by metal construction, and the introduction of rat-proof shipping containers in 1956 - instead of individual storage in the hold - as well as the use of traps and rodenticides meant that ship cats are rarely found on sailors and motor ships today.

Halifax

Halifax was Alvah and Diana Simon's ship cat, who the Simons found in Halifax Harbor on their way to winter in Tay Bay in 1994 on the Roger Henry . While Diana had to leave the boat for family reasons, Alvah and the cat stayed on the boat that was trapped in the pack ice . Alvah Simon's book North to the Night North to Night describes his adventure with Halifax, which eventually lost half an ear to frostbite.

Chibley

Chibley (also Chibs) was brought from a shelter in 1997 and became the ship's cat on board the three-masted Canadian tall ship Picton Castle . Since the Picton Castle has been a sailing training ship since the 1990s , Chibley came into contact with more than 1000 people and thus became a celebrity who even received her own fan mail. Chibley died 10 November 2011 on land in Lunenburg in the province of Nova Scotia , after being hit by a car. She had circumnavigated the world five times with Picton Castle since 1997, covering around 250,000 nautical miles at sea.

Ship's cat motif in literature

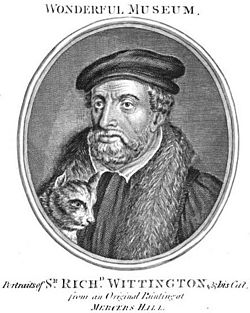

Dick Whittington and His Cat

The merchant, politician and traveler Richard Whittington (around 1354-1423) provided the template for the medieval legend Dick Whittington and His Cat , which was created in fragments as a story, play and ballad as early as the 17th century. Around 1820 George Cruikshank published an illustrated version of the legend and the Australian Joseph Jacobs published the story in his English Fairy Tales in 1890 .

The legend tells in many episodes the life of the orphan boy Richard (Dick) Whittington, who is looking for his fortune in London. He has a cat, which he also takes on a trade trip to Africa. The sultan of the barbarian states , to whom the shipload is to be sold, has put an end to a rat and mouse plague, the Wittington's cat, which had already proven its skills as a ship's cat. The cat is sold for more money than the rest of the cargo, and Richard Whittington becomes a wealthy and respected man.

In the description of his ship's cat Trim (see above) Matthew Flinders mentions Whittington's cat and elements of the Whittington theme are also varied in the children's books Molly, the Ship's Cat and Captain Katz .

Short stories, novels, travelogues, biographies

Ship cats are mentioned in adventure and travel literature and occasionally in scientific reports. The following examples by well-known authors are a selection.

- The English writer Daniel Defoe (approx. 1660–1731) was inspired by the real experiences of Alexander Selkirk (1676–1721) in his novel Robinson Crusoe . This also included his stories of ship cats released on the island of Isla Más a Tierra , which Defoe used modified in his novel.

- The German naturalist and poet Adelbert von Chamisso (1781–1838) describes the existence and behavior of several ship cats in his trip around the world , which he undertook on the Rurik from 1815 to 1818 .

- The Swiss natural scientist Johann Rudolf Rengger (1795–1832) reports in the legacy of his Paraguay trip that “the cursed ship's cat” ate up a rail shot the day before and made it unusable as a biological sample.

- In his travelogues, the American writer Mark Twain (1835–1910) thought about how ship cats that go ashore manage not to miss the departure date.

- The French naval officer and writer Pierre Loti (1850-1923) tells in his novella Vies de deux chattes (1907), among other things, the story of the "ship's cat" Moumoutte Chinoise. During a sea battle at the time of the Boxer Rebellion in China , this cat escaped from a junk on the armored cruiser on which Loti was on duty and hid under his bed in his cabin, frightened. The cat lover Loti looked after her and during the months that followed, during which a relationship developed between Loti and Moumoutte Chinoise, the cat never left Loti's cabin, but seemed very interested in the Chinese antiques Loti collected over time . Only at the end of the mission, back in France in Loti's house with a garden, did Moumoutte Chinoise, the cat who was not a ship's cat, begin a normal cat life.

- The British writer Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936) published a short story in 1899 that tells the story of Erastasius of the Whanghoa , the cat who was raised by the devil.

- The well-traveled Danish writer and Nobel Prize winner Johannes Vilhelm Jensen (1873–1950) provides his impressions of a boat trip from Hamburg to Port Said in the short story Katzenkinder . He describes in detail how the seafarers - "rough fellows", "rough brothers" - play with the kittens of the ship's cat's fourth litter shortly before departure and "shake each other with laughter and look guilty when they are discovered". Jensen also pays attention to the behavior of the ship's cat, Sophus, and the stories told by the crew and the captain about ship's cats.

- The Canadian writer Mazo de la Roche (1879–1961) describes in the short story Cat's Cruise (1939) the adventures and emotions of the black ship's cat, Cat, who chooses her ships at her own whim and brings luck to every member of the crew.

- The German naval officer and cat lover Felix Graf von Luckner (1881–1966) is said to have hijacked and sunk around 20 ships without even killing a sailor. In his autobiography From the Life of a Sea Devil , von Luckner claims that he had the cats evacuated before each ship was sunk.

- The German writer Gustav Schenk (1905–1969) is the author of the story Seefahrer Kador , in which he describes the ship's cat Kador as a "gray hero with ... a terrible scar, about which every seafarer can tell sailors who are busy ... Happy the ship, whose planks touched Kador's soft soles. "

- In the novel The Eyes of the Sea by the Greek writer Ioanna Karystiani there are extreme scenarios in which ship cats are the focus: a captain who prefers not to be near his wife, but instead adores year in, year out on his freighter with his ship cat Maritsa live that he has the ship's cook cook delicious meals; a ship with such an overpopulation of cats that there are more cats than crew on board.

Children's books

For children, stories about "ship cats" combine an interest in animals with adventure stories. These animal adventure stories have been popular since the 19th century, especially in English-speaking countries . The following, incomplete list gives some examples of novels, stories in poetry and picture books with the theme of ship's cat .

- Heinz Rieder: Mira (The adventurous life of a ship's cat) , I. & S. Federmann, Munich (1949)

- Esther Averill: Jenny Goes to Sea , Review Books, New York 1957, ISBN 978-1-59017-155-4

- Ruth Park: The Ship's Cat , Macmillan (1961)

- Richard Adams and Alan Aldridge: Ship's Cat , Jonathan Cape Ltd, 1977, ISBN 978-0-224-01441-0

- Ludvik Askenazy (author) and Dieter Wiesmüller (draftsman): Molly, the ship's cat , Sauerlander, 1978, ISBN 978-3-7941-1770-3

- Helga Meyer:

- A tomcat goes on board , Verlag Junge Welt, Berlin (1974)

- A hangover on a long journey , Verlag Junge Welt, Berlin (1978)

- Bengt Martin (author) and Anna Friberger (illustrator): Olaf the Ship's Cat , Checkerboard Press, 1992, ISBN 978-1-56288-266-2

- Jane Simmons: Ship's Cat Doris , Hodder & Stoughton, 2011, ISBN 978-1-4083-0896-7

- Susan Aardvark (Author), Josh Wilson (Illustrator) and Sherry Deer-Wylie (Eds.): Scratch the Ships Cat and the Dog Smuggler , Susan Downham (2015)

literature

- Val Lewis: Ship's Cats in War and Peace , Nauticalia, Shepperton 2001, ISBN 978-0-9530458-1-5 .

- Wolfgang Schwerdt: Researchers, cats and cannons: About the life and work of explorers in the 18th and 19th centuries , Past Publishing, 2012, ISBN 978-3-86408-094-4 .

- Detlef Bluhm : Schiffskatzen , Insel Verlag, 2014, ISBN 978-3-458-36011-7 .

Web links

Individual evidence and explanations

- ↑ Reproduction of a colored wall painting from the tomb of Nebamun; around 1350 BC Chr .; the cat was highlighted in color for the article.

- ^ Claudio Ottoni and a .: The palaeogenetics of cat dispersal in the ancient world . In: Nature Ecology & Evolution 1, Article No. 0139, 2017 (English), doi : 10.1038 / s41559-017-0139 .

- ↑ a b c Detlef Bluhm : Schiffskatzen , Insel Verlag GmbH (2014), Chapter 1: Hired: The ship's cat was born .

- ^ A b Jaromír Málek: The Cat in Ancient Egypt . British Museum, 2006, ISBN 978-0-7141-1970-0 .

- ↑ Advanced painting techniques in ancient Egypt , New Scientist, January 15, 2009; accessed on June 13, 2015.

- ^ Malyn Newitt: A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion 1400–1668 . Routledge, November 5, 2004, ISBN 978-1-134-55304-4 , p. 65.

- ↑ Glenn Joseph Ames: Vasco Da Gama: Renaissance Crusader . Pearson / Longman, 2005, ISBN 978-0-321-09282-3 .

- ↑ Mischa Damjan and Rudolf Schilling: Mau Mao Miau - The cat through the millennia , Eugen Diederichs Verlag (1069), p. 241 ( ship cats ).

- ↑ John Bradshaw: The World from a Cat's Point of View: Ways to Better Coexistence - Insights from a behaviorist . Franckh-Kosmos Verlags-GmbH & Company KG, March 5, 2015, ISBN 978-3-440-14710-8 , p. 81 ff.

- ↑ John Bradshaw: The World from a Cat's Point of View: Ways to Better Coexistence - Insights from a behaviorist . Franckh-Kosmos Verlags-GmbH & Company KG, March 5, 2015, ISBN 978-3-440-14710-8 , p. 94 ( first selection based on appearance ).

- ↑ The practical veterinarian . Federal Association of Practical Veterinarians., January 1993.

- ^ Frank Joseph and Zecharia Sitchin: Discovering the Mysteries of Ancient America: Lost History and Legends, Unearthed and Explored , Career Press (2006), ISBN 978-1-56414-842-1 , p. 163.

- ↑ Christiane Sacase: Le Norvégien . Editions Artemis, July 11, 2007, ISBN 978-2-84416-607-4 , p. 10.

- ↑ J. Anne Helgren, Michele Earle-Bridges, David Wenzel: Himalayan Cats . Barron's Educational Series, 2006, ISBN 978-0-7641-3403-6 , p. 6.

- ↑ The German diplomat Kurt Herzbruch reports on a trip to Abyssinia: “These uninvited guests [he speaks of rats] had become very out of hand on board since the two cats on board had given their time. One day they were prepared with curry and eaten as a delicacy by the natives who were on duty as stokers on our steamer. " ( Kurt Herzbruch: Abyssinia: a trip to the court of Emperor Menelik II . F. Seybold, 1925. )

- ↑ There are many other typically nautical terms associated with cats, especially in English: Arthur Young, James Brisbane: Nautical Dictionary: Defining the Technical Language Relative to the Building and Equipment of Sailing Vessels and Steamers, Seamanship, Navigation, Nautical Astronomy, naval Gunnery, Maritime Law and Commerce, General and Particular Average and Marine Insurance, and Other Terms Relating to Maritime Affairs ... . Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, 1863, pp. 77 f.

- ^ Bibliothèque Nationale de France: Black Book of the Admiralty .

- ↑ a b c d Detlef Bluhm: Schiffskatzen, Insel Verlag GmbH (2014), Chapter 3: On the high seas .

- ↑ Lord Andrew MacDowall Bankton: An Institute of the Laws of Scotland in Civil Rights: With Observations Upon the Agreement Or Diversity Between Them and the Laws of England. In Four Books. After the General Method of the Viscount of Stair's Institutions ... . R. Fleming, 1751, p. 39.

- ^ Adrien Loir: Le chat ratier . In: Revue d'hygiène et de médecine préventive . tape 53 , 1931, pp. 182-187 .

- ^ M. de Moncrif (François Augustin): Histoire des chats . Pardès, 1988, ISBN 978-2-86714-055-6 , p. 24.

- ↑ Yearbook of the German Navy 1936.

- ^ A b The Rabies (Control) Order 1974: Animals - Diseases of Animals (No. 2212; decree: December 31, 1974, entry into force: February 5, 1975).

- ↑ Muriel Beadle: Cat . Simon and Schuster, October 29, 1979, ISBN 978-0-671-25190-1 , p. 94.

- ^ A b c Steve Roud: The Penguin Guide to the Superstitions of Britain and Ireland . Penguin Books Limited, April 6, 2006, ISBN 978-0-14-194162-2 , p. 262.

- ↑ This source claims that ship cats were compulsory on ships of the Royal Navy until 1976 : Wendy Christensen: Outsmarting Cats: How to Persuade the Felines in Your Life to do What You Want . Lyons Press, March 5, 2013, ISBN 978-0-7627-9308-2 , p. 29.

- ↑ a b www.purr-n-fur.org.uk: Famous ships cats and their lives , accessed June 10, 2015.

- ↑ Detlef Bluhm: Schiffskatzen , Insel Verlag GmbH (2014), Chapter 5: In the hammock: Religion and superstition .

- ^ Richard Webster: The Encyclopedia of Superstitions . Llewellyn Worldwide, September 1, 2012, ISBN 978-0-7387-2561-1 , p. 235.

- ↑ Superstitions add to Marine Terror . Princeton Alumni Weekly, 1926, p. 979, PRNC: 32101081976670.

- ↑ Douglas E. Campbell and Stephen J. Chant: Patent Log: Innovative Patents that Advanced the United States Navy: 1922 Rat Guard , (2013), ISBN 978-1-105-62562-6 , p. 254.

- ^ Phoebus: Nürnberger Morgenblatt: for readers of all levels . Stich, 1847, p. 645.

- ↑ Jonathan Eyers: Don't Shoot the Albatross !: Nautical Myths and Superstitions . Bloomsbury Publishing, December 3, 2012, ISBN 978-1-4081-3213-5 , p. 81.

- ^ Mona A. Radford, Edwin Radford: Encyclopedia of Superstitions . Philosophical Library, February 24, 2015, ISBN 978-1-5040-1093-1 , p. 140.

- ^ Carl Van Vechten: The Tiger in the House . Courier Corporation, June 12, 1996, ISBN 978-0-486-29129-1 , p. 122.

- ↑ Deborah Hopkinson, Titanic: Voices From the Disaster . Scholastic Incorporated, January 7, 2014, ISBN 978-0-545-45238-0 , p. 27. This Jim Mulholland story could be found in other sources - s. u. "Jenny" - not to be verified.

- ↑ Frank Pope: The Wreck of Hoi An: The True Story of an Adventurous Treasure Hunt . Scherz, 2009, ISBN 978-3-502-15123-4 .

- ↑ Otto Beneke: Hamburgische histories , 2nd collection, 1916, pp. 372-375.

- ^ Johann Georg Adam Forster: Johann Reinhold Forster's journey around the world: during the years 1772 to 1775 in the ... ships sent out on discoveries and guided by Captain Cook undertook the Resolution . bey Haude and Spener, 1784, p. 133.

- ↑ James Cook, Andrew Kippis: The Life of Captain James Cook. A New Edition. [An Abridgment of the Biography by Andrew Kippis. With Plates.] . CF Cook, 1835, p. 100.

- ↑ In the original: master of the ship

- ^ Caroline Alexander: The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty . Penguin Publishing Group, May 25, 2004, ISBN 978-1-4406-2751-4 , p. 25.

- ^ Document Pandora History and Mysteries , Queensland Museum .

- ^ US Naval Institute Cats in the Sea Services ; Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ↑ a b In his biography of Trim are Flinders the ships on which he traveled or which he captained, nickname: HMS Reliance he referred to there as Roundabout , the HMS Investigator he calls word playful Spyall , the HMS Porpoise is for him Janty and the Cumberland he gives the name Minikin . It is not known whether this approach was based on Flinder's humor or whether he wanted to avoid the official names of the ships in this very personal biographical tribute .

- ↑ Mentioned several times as such in A Biographical Tribute to the Memory of Trim .

- ↑ A Voyage to Terra Australis , with an accompanying Atlas, 2 volumes, London, G & W Nicol, July 18, 1814 (one day before Flinder's death) picture text .

- ↑ a b c d e f A Biographical Tribute to the Memory of Trim

- ↑ a b Detlef Bluhm: Schiffskatzen , Insel Verlag GmbH (2014), Trim , pp. 24–32.

- ↑ Flinders gave Trim's weight as his weight being from ten to twelve pounds , about 4.5 to 5.4 kg.

- ↑ In the original: ... that this excellent unsuspecting animal was stewed and eaten by some hungry black slave ...

- ↑ Flinders Memorial: The Unveiling of the Flinders Memorial Statue , October 27, 2014; accessed on June 15, 2015.

- ^ Deane Williams, Daniel Keane: Matthew Flinders and his cat Trim honored with statue in Port Lincoln. February 24, 2017, Retrieved August 28, 2019 (Australian English).

- ↑ Jacques Boucher de Perthes: Les Masques: Biography sans nom: Portraits de mes Connaissances dédiés á mes amis 1861, pp. 487–493.

- ↑ In the French original: "... jamais le navire Argo lui-même n'en avait eu une pareille."

- ↑ Bouchiq probably slept on the bed in his cabin.

- ↑ The Voltigeur had just been sanded down and repainted.

- ↑ Jacques Boucher de Perthes points out here that Bretons are known for being very stubborn.

- ↑ Roscoff is about 80 km as the crow flies from Tréguier, the home port of the Voltigeur .

- ↑ At the time of writing, the Voltigeur was still on duty and Bouchiq was still alive. At the end of the 7-page story, Jacques Boucher de Perthes speaks directly to the reader about the credibility of the Bouchiq story, but at the same time refers to the ship's logbooks.

- ↑ a b The sex is unknown, but evidence in the literature suggests that it was a tomcat.

- ↑ Mick Conefrey: The Adventurer's Handbook: From Surviving an Anaconda Attack to Finding Your Way Out of a Desert . Oneworld Publications, November 7, 2013, ISBN 978-1-78074-319-6 , p. 63.

- ↑ Val Lewis: Ship's Cats in War and Peace . Nauticalia, Shepperton 2002, ISBN 0-9530458-1-1 , pp. 59-60.

- ↑ Belgica Belgian Antarctic Expedition 1897–1899 at www.coolantarctica.com (English).

- ↑ a b Theodor Lerner: polar driver. Under the spell of the Arctic . Oesch Verlag, Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-0350-2014-0 , p. 47 .

- ^ Neil R. Storey: Animals in the First World War . Shire Publications, March 10, 2014, ISBN 978-0-7478-1367-5 , p. 16.

- ↑ Gender is uncertain; in English-language literature, sometimes she ( she ), sometimes he ( he ) is written for kiddo .

- ↑ In the original: "Roy, come and get this goddamn cat."

- ^ A b Allan Janus: Animals Aloft: Photographs from the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum . Bunker Hill Publishing, Inc., 2005, ISBN 978-1-59373-048-2 , p. 28.

- ↑ Linda Lombardi: Animals Behaving Badly: Boozing Bees, Cheating Chimps, Dogs with Guns, and Other Beastly True Tales . Penguin Publishing Group, October 4, 2011, ISBN 978-1-101-54491-4 , p. 108.

- ^ Peter Joseph Capelotti: By Airship to the North Pole: An Archeology of Human Exploration . Rutgers University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-8135-2633-1 , p. 93.

- ^ Allan Janus: Animals Aloft: Photographs from the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum . Bunker Hill Publishing, October 15, 2005, ISBN 1-59373-048-9 . , 128 ff.

- ↑ Sir Ernest Shackleton, Captain Robert Falcon Scott, Roald Amundsen, Apsley Cherry-Garrard and Sir Douglas Mawson: The Antarctic Exploration Anthology: The Personal Accounts of the Great Antarctic Explorers . Bybliotech, March 14, 2013, ISBN 978-1-62590-993-0 , p. 1000.

- ^ Elspeth Joscelin Grant Huxley: Scott of the Antarctic . University of Nebraska Press, 1990, ISBN 0-8032-7248-0 , p. 202.

- ↑ Detlef Bluhm: Schiffskatzen , Insel Verlag GmbH (2014), Chapter 7: Survival on board .

- ^ Adolf Miethe : The journey of the "Mainz". In: Adolf Miethe, Hugo Hergesell (ed.): With Zeppelin to Spitzbergen . Bong, Berlin 1911, pp. 17–164, here: p. 19 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ^ Adolf Miethe : The journey of the "Mainz". In: Adolf Miethe, Hugo Hergesell (ed.): With Zeppelin to Spitzbergen . Bong, Berlin 1911, pp. 17–164, here: p. 102 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ^ John P. Eaton and Charles A. Haas (preface by William MacQuitty): Titanic: A Journey Through Time , WW Norton & Company (1999), ISBN 978-0-393-04782-0 .

- ↑ Free German translation; Originally: The cat "laid her family near Jim, the scullion, whose approval she always sought and who always gave her warm devotion." ; Violet Jessop (with introduction, edition and annotations by John Maxtone-Graham): Titanic survivor: the newly discovered memoirs of Violet Jessop who survived both the Titanic and Britannic disasters , Sheridan House, Dobbs-Ferry (2004), ISBN 1-57409- 184-0 .

- ^ Charles Pellegrino: Farewell, Titanic: Her Final Legacy . John Wiley & Sons, Jan 20, 2012, ISBN 978-1-118-19129-3 , p. 385.

- ^ Sheila Nickerson: Harnessed to the Pole: Sledge Dogs in Service to American Explorers of the Arctic 1853-1909 . University of Alaska Press, May 15, 2014, ISBN 978-1-60223-223-5 , p. 105.

- ↑ LD Cross: The Luck of the Karluk: Shipwrecked in the Arctic . Heritage House Publishing Co, May 1, 2015, ISBN 978-1-77203-020-4 , p. 131.

- ↑ Jennifer Niven: The Ice Master: The Doomed 1913 Voyage of the Karluk . Hachette Books, October 1, 2001, ISBN 978-0-7868-7097-4 , p. 166.

- ^ Edward E. Leslie, Sterling Seagrave: Desperate Journeys, Abandoned Souls: True Stories of Castaways and Other Survivors . Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1998, ISBN 0-395-91150-8 , p. 309.

- ↑ Jennifer Niven: The Ice Master: The Doomed 1913 Voyage of the Karluk . Hachette Books, October 1, 2001, ISBN 978-0-7868-7097-4 , p. 365.

- ↑ See also section on superstition .

- ↑ D / S Rinda . Was sailors. Retrieved February 7, 2012.

- ↑ Purr 'n' Fur: Featuring Felines ; accessed on June 15, 2015.

- ^ Janusz Piekałkiewicz: Sea war, 1939-1945 . Historical Times, June 1, 1987, ISBN 978-0-918678-17-1 , p. 173.

- ^ Rear Admiral Sir William Jameson ( William Jameson: Ark Royal 1939-1941 . Rupert Hart-Davis, 1957. ) describes the direct rescue as "a huge yellow cat", without giving a name. During the subsequent search of the sea by motorboat, Jameson mentions a second cat (without description) that clung to a piece of wood.

- ↑ This is where the reports differ: sometimes it's the Governor General, sometimes the harbor master, sometimes Oscar lived there before he came to the Ark Royal , sometimes it was afterwards .

- ↑ According to other sources, the Home for Sailors was in Belfast .

- ↑ Detlef Bluhm: Schiffskatzen , Insel Verlag GmbH (2014), Chapter 8: Oskar .

- ↑ a b Although not clearly specified, descriptions suggest that the ship's cat was a tom; in English texts the paraphrase “he” ('he') is used.

- ↑ Jenny Awford: Cat kept at Winston Churchill's country estate in honor of wartime PM's dying request is barred from large parts of home because of his CLAWS , Daily Mail Online, January 24, 2015; Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ R. Jerrard: Royal Navy (Cats) , (2002) ( Memento of November 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Fred Glueckstein: Churchill's Feline Menagerie . The Churchill Center. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ↑ The sex is unknown, but evidence in the literature suggests that it was a cat.

- ↑ United States Coast Guard: Coast Guard Mascots Go to War ; accessed on June 24, 2015.

- ↑ Gender unknown

- ↑ www.purr-n-fur.org.uk Featuring Felines ; accessed on June 24, 2015.

- ^ Iain Ballantyne: Warspite . Casemate Publishers, July 1, 2010, ISBN 978-1-84884-350-9 , p. 194.

- ↑ Unusual spelling of AB: Able seaman .

- ↑ Free translation

- ↑ Loosely translated: Through his behavior he was a role model for others.

- ↑ Loosely translated: On August 25th, during the bombing of the Brest fortress, he behaved like a real sailor.

- ^ The Nautical Magazine 1952.

- ↑ a b J.D. Carpentieri: That sinking feline , The Guardian Online, Aug. 4, 2001; accessed on June 10, 2015.

- ↑ Original: United States attack transport

- ↑ In the original: service ribbons

- ↑ Los Angeles Times Photographs Collection: Pooli, cat who served aboard an United States attack transport during World War II celebrates 15th birthday , accessed May 12, 2019.

- ↑ Loosely translated: Felix and his adventures on the Mayflower II

- ↑ Peter Arenstam, Plimoth Plantation, Inc: Felix and His Mayflower II Adventures . Plimoth Plantation, 2007, ISBN 978-0-9793348-1-8 .

- ↑ Nina Massey: War hero cat who protected vital food rations despite being badly wounded by shrapnel commemorated , Mirror Online, November 28, 2014; accessed on June 15, 2015.

- ↑ Detlef Bluhm: Schiffskatzen , Insel Verlag GmbH (2014), Chapter 10: Simon .

- ^ Navy News, August 2007 ; accessed on June 10, 2015.

- ↑ mouse catcher ; Since Wunpound was listed in the ration list of the Hecate and was thus officially a "crew member", members of the crew filled out a census sheet for "Fred Wunpound" in which this "occupation" and other information were given and submitted this document.

- ^ Navy News, July, 1975.

- ^ Joan Palmer: All about cats . Ward Lock, 1986, ISBN 978-0-7063-6297-8 .

- ^ Sandra Choron, Harry Choron, Arden Moore: Planet Cat: A Cat-Alog . Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, January 2007, ISBN 0-618-81259-8 , p. 123.

- ^ The Daily Telegraph, July 1976.

- ↑ Hilda Kean: Animal Rights - Political and Social Changes in Britain since 1800 , Reaction Books Ltd, 1998, p. 250.

- ^ Alvah Simon: North to the Night: A Spiritual Odyssey in the Arctic , Broadway Books (1999), ISBN 978-0-7679-0446-9 ; German North of the Night (2002).

- ↑ Barque Picton Castle - Captain's Log: Chibley of the Picton Castle - A Seagoing Cat From Lunenburg

- ^ The renowned history of Richard Whittington and his cat , J. Babcock & Son (1824).

- ^ William Granger, James Caulfield: History of the Memorable Sir Richard Whittington . In: The New Wonderful Museum, and Extraordinary Magazine , Volume vol. 3. Alex. Hogg & Co., 1805, p. 1420.

- ↑ George Laurence Gomme, Henry Benjamin Wheatley: Chap-books and folk lore Tracts: The history of Sir Richard Whittington, by T. H . Villon Society, 1885.

- ↑ Ludvík Aškenazy: Molly, the ship's cat , Aarau (1978), drawings by Dieter Wiesmüller.

- ^ Inga Moore: Käptn Katz , Urachhaus , Stuttgart (2014), ISBN 978-3-8251-7885-7 ; Original: Captain Cat , Candlewick (2013), ISBN 978-0-7636-6151-9 .

- ↑ Detlef Bluhm: Schiffskatzen , Insel Verlag GmbH (2014), Chapter 9: In foreign ports .

- ^ Johann Rudolf Rengger, Albrecht Rengger: Journey to Paraguay 1818 - 1826: With 1 map and 3 sheets of illustrations . Sauerländer, 1835, p. 391.

- ^ Mark Twain: The Writings of Mark Twain: Following the equator; a journey around the world . Harper and brothers, 1809, p. 12.

- ↑ Pierre Loti: Vies de Deux Chattes . CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, November 12, 2014, ISBN 978-1-5031-7375-0 .

- ↑ Rudyard Kipling: Erastasius of the Whanghoa , Civil and Military Gazette, August 21, 1889.

- ↑ Jensen does not judge whether his story about the ship's cat, which is said to have caught 54 mice in one morning, is true, or whether it was sailor's yarn .

- ↑ Aage Jørgensen, Sven Hakon Rossel: Praised be the light of the world--: the Danish poet Johannes V. Jensen: a research anthology . Praesens, 2007, ISBN 978-3-7069-0399-8 .

- ^ Johannes Vilhelm Jensen in The Most Beautiful Cat Stories , Zurich, Diogenes Verlag (1973).

- ^ Felix Graf von Luckner: From the life of the "Seeteufels": Letters and records . Mitteldeutscher Verlag, 2000, ISBN 978-3-89812-020-3 .

- ↑ Eugen Skasa-Weiss: Katzenspiegel: Collected and introduced . F. Bruckmann, 1963.

- ^ Bernice E. Cullinan, Diane Goetz Person: The Continuum Encyclopedia of Children's Literature . A&C Black, 2005, ISBN 978-0-8264-1778-7 , p. 9.