silk

| Debaffed silk | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Fiber type | |

| origin |

Silkworm |

| colour |

white shimmering shine |

| properties | |

| Fiber length | 800-3000 m / cocoon; 50 km tearing length (deburred thread) |

| Fiber diameter | 12-24 µm; Wild silk 40–70 µm |

| density | 1.25 g / cm³ deburred; 1.3-1.37 g / cm³ raw |

| tensile strenght | 350-600 MPa |

| modulus of elasticity | 8.0-12.5 GPa ; 7-10 GPa |

| Elongation at break | 20-30% |

| Water absorption | 10% at f 65% / 20 ° C |

| Products | textiles |

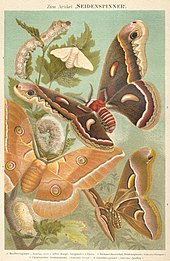

Silk (from Middle Latin seta ) is an animal fiber. It is obtained from the cocoons of the silkworm , the larva of the silk moth . Silk is the only naturally occurring continuous textile fiber and consists mainly of protein . It originally comes from China and was an important commodity that was transported to Europe via the Silk Road . In addition to China, where the main part is still produced today, are Japan and Indiaother important producing countries in which silk is cultivated.

The associated adjective is silk (consisting of silk) or silky (reminiscent of silk, comparable to silk).

history

Beginnings

Silk was already known to the ancient Indus civilization (around 2800 to 1800 BC) and ancient China. Exact investigations into the silk structure of archaeological finds revealed that the silk moth of the genus Antheraea was used for silk production in the Indus region . It is a so-called wild silk. Today's silk, on the other hand, came only from the domesticated silk moth ( Bombyx mori ). The origin of the latter is around the 3rd millennium BC. Chr. , And is more of legends, as that there were exact dates. According to legend, the legendary Emperor Fu Xi (around 3000 BC) in China was the first to have the idea of using silkworms to make clothes. Fu Xi is also considered to be the inventor of a stringed instrument covered with silk threads . The legend mentions another famous emperor: Shennong (god of agriculture, around 3000 BC) is said to have taught the people to grow mulberry trees and hemp in order to obtain silk and hemp linen. Leizu von Xiling , the wife of the Yellow Emperor Huáng Dì , is said to have lived in the 3rd millennium BC. BC taught the people to use cocoons and silk to make clothes.

Based on this legend, based on the chronology of the Chinese emperors, silk was created from 2700 to 2600 BC. Assumed since the excavations of Qianshanyang found fragments of silk fabric, which by means of radiocarbon dating to the time around 2750 BC. Could be dated. Recent archaeological finds of chemical relics of the silk protein fibroin in two 8,500-year-old graves suggest that the Neolithic inhabitants of Jianhu already woven the silk fibers into fabrics.

Roman times

Long-distance trading in Chinese silk already existed at the beginning of the Christian era. According to the Roman Pliny the Elder (around 23 to 79 AD), who also describes the silkworms, the ancient Mediterranean region owes the production of Koic silk to a certain Pamphilia from Kos . However, this silk was increasingly being replaced by finer and thinner Chinese silk. According to Publius Annius or Lucius Annaeus Florus , the Romans were to face the crushing defeat they suffered in 53 BC. The Parthians at the Battle of Carrhae learned to know Chinese silk for the first time. Florus is the only one of the Roman historiographers who mentions the silk legend in connection with Carrhae.

The Roman satirical poet Juvenal complained in 110 AD that Roman women were so spoiled that they now even found the fine silk to be too rough. The Chinese silk reached Rome via several trading posts . Chinese traders brought the silk to the ports of Sri Lanka , where Indian traders bought it. Arab and Greek traders bought silk on the southwest coast of the Indian subcontinent. The next transshipment point was the Socotra archipelago in the north-western Indian Ocean. From there, the silk was usually brought to the ancient Egyptian Red Sea port of Berenike ( India trade ). Camel caravans then transported them on to the Nile, where the cargo was again shipped to Alexandria . Here they mostly bought up Roman traders who finally imported the silk into what is now Italy . A characteristic of this long-distance trade was that Chinese traders rarely appeared west of Sri Lanka, Indian traders only took over the intermediate trade as far as the Red Sea and Roman traders limited themselves to trade between Alexandria and the Roman Empire. Greek traders, on the other hand, had the largest share in these transactions and traded silk from India to the Italian coast. It took about 18 months for silk from southern China to reach ports along the Italian coast. Trade on the Silk Road did not increase until the 2nd century AD. The beginning of the Silk Road is often around 100 BC. Chr. Indicated. It is believed that this was due to the officer Zhang Qian, whom Emperor Wudi had sent to the kingdoms of Central Asia to establish trade relations. This trade route was much more complex and the exact route shifted according to the respective political conditions. Typical transhipment points for silk were Herat (today Afghanistan), Samarkand (today Uzbekistan) and Isfahan (today Iran). While Greek traders played a major role in maritime trade, Jewish , Armenian and Syrian middlemen dominated overland trade.

middle Ages

The Chinese were forbidden to take the caterpillars or their eggs out of the country under penalty of death . Around the year 555, however, two Persian monks allegedly managed to smuggle some eggs to the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I in Constantinople . With these eggs and the knowledge they had acquired during their stay in China about rearing silk spiders, it was now possible to produce silk outside of China. However, it is questionable whether the silkworm eggs would have survived this long journey. What is certain, however, is that silk production began in the Byzantine Empire around 550 AD . A number of regions in Europe established themselves as centers of silk production and silk dyeing. From the 12th century Italy became a leader in the production of European silk. Early centers of production and processing were Palermo and Messina in Sicily and Catanzaro in Calabria . The northern Italian city of Lucca owed its influence and power in the 13th century, for example, to its silk industry with its mechanical, water-powered silk twine mills . In particular, the splendor of colors in which Luccaner dyers could dye this silk was considered unsurpassed in Europe. Political unrest at the beginning of the 14th century led Lucca textile craftsmen to settle in Venice and this led to a knowledge transfer that in the long term contributed to Lucca becoming an insignificant provincial town. An important trade route for silk led from Italy over the Brenner Pass to Central Europe, with Bozen being a central hub for the silk trade on this route since 1200.

Modern times

From the 15th century, silkworm breeding also spread in the southern French regions of Ardèche , Dauphiné and the Cevennes , where many rural properties still have buildings that were formerly used for silkworm breeding and are known as magnaneries .

In addition to Zurich and Lyon , Krefeld also had an important silk industry from the 17th to 19th centuries , which was dominated by the von der Leyen family . Among the most famous customers were the French Emperor Napoleon and the Prussian King Friedrich II. In 1828, as part of the growing dissatisfaction of the German weavers, there were also uprisings among silk weavers in Krefeld . They protested against the Von der Leyen company wage cuts .

In the 19th century in Bavaria under Ludwig I the silkworm breeding and thus the mulberry planting was promoted.

Due to rampant animal diseases , sericulture was largely stopped in southern France, Italy and the Mediterranean around 1860.

Formation and extraction

Since most of the silkworms feed on the leaves of the mulberry tree , it is called mulberry silk . But there are also silkworms, such as B. those of the Japanese oak silk moth ( Antheraea yamamai ), which feed on oak leaves . To obtain quality silk , silkworms have to be raised under special conditions.

The caterpillars pupate, producing the silk in special glands in the mouth and laying it around them in large loops in up to 300,000 turns. They are killed using hot water or steam before they hatch to prevent the cocoons from being bitten. Each cocoon contains an uninterrupted, very long and fine filament . Three to eight cocoons or filaments are unwound or coiled together (so-called reel silk), stick together due to the silk glue and form a so-called grège , a silk thread. This thread can be processed into smooth textile surfaces. To obtain 250 g of silk thread, around 3000 cocoons are required, which corresponds to around 1 kg.

In order to free the silk from the silk glue ( sericin , also silk bast ), which is also the carrier of the yellow and other colors, it is boiled in soapy water and appears pure white. This process is called peeling or degumming . The silk threads become thinner, smoother and shinier through cooking. The silk is then often further refined chemically . Removing the silk glue makes the thread lighter, which is partially offset by the addition of metal salts (mostly tin compounds). The silk is bleached by sulfur dioxide .

Weaving silk on a loom

Applications

Silk yarn

Several coiled silk threads are twisted together . Functionally adapted weft and warp threads are created using different twisting techniques . In this case, after the 60550 DIN ( "weaving yarns of silk") as organzine (or organzine ) a twisting referred to, which is made of two or three Grègen which are themselves already twisted; this yarn quality can be used for warps. Trame yarn, on the other hand, is twisted from two or more untwisted Grègen and is only suitable as weft material.

Silk fabric

Different weaving processes or treatments result in different silk qualities. Typical types of fabric used for further processing of silk are:

- Assemblée

- Balloon, parachute silk

- Batavia

- Bengaline

- Bobbinet

- Bombasin

- brocade

- Burat

- Charmeuse

- chiffon

- Crêpe de Chine - preferred quality among designers for its soft, crease-resistant drape, and raw material for hand-painted kimono , especially in the Yûzen process.

- Crêpe satin

- damask

- Duchess

- Dupion silk (typical irregularities in the threads)

- Duvetine

- Eolienne

- Faillé - warp made from organsine, weft made from Schappseide, the light quality is called Failletine.

- Floche

- Georgette

- Ice cream

- Grenadine

- Habotai silk, also known as pongee , is a type of silk that is particularly suitable for silk painting due to its very fine, smooth surface. This type of silk is considered to be of high quality, but is relatively inexpensive compared to other types of silk.

- Helvetia silk

- Honan silk - comes from the Honan Province in China. It consists of wild silk and is woven in taffeta weave.

- Jacquard

- Pongé , Habotai - basic material of classical (western) silk painting, a smooth, canvas-woven fabric with a fine sheen; has a strong tendency to crease and is therefore preferred for pleated blinds .

- Lumineux

- Lame

- Organza / Organsin, a 2 to 3- ply thread , which is mainly used as a warp thread (a distinction is made between the number of twists per meter of taffeta, satin, velvet, stratorto and grenadine )

- Paris silk

- Peau de soie

- Pleated blind

- Ramagé

- Samit

- Satin or atlas

- Silk jersey is actually not a silk fabric because it is not woven but knitted.

- Shantung silk - looks similar to dupion silk, which is obtained from double cocoons of silk moths, has less sheen than reel silk and is somewhat coarser to the touch.

- Soie Ondé

- Surah

- Taffeta

- Tarlatan (Grogram)

- Trame

- Silk twill

- Washing silk

Other silk fabrics are Attaline, Barege , Bock fabric, Ciré, Cisélé, Foulard, Rabanne, Radium, Rips-barré, Rupfen, Merveilleux, Onduleuse, Diobiris, Astarté, Alepine, Trikotine, Toile , Matelassé , Boyeau, Avignon, Armuré, Régence.

Silk powder

Silk powder is used as an additive in cosmetic products, e.g. B. in lipsticks , skin creams and soaps.

Properties and quality designations

Silk is characterized by its sheen and its high strength and has an insulating effect against cold and heat. It can store up to a third of its weight in water. Silk has little tendency to wrinkle. Particularly brilliant colors are achieved on silk fabrics. Silk is sensitive to high temperatures, abrasion and water stains.

The quality of silk depends, among other things, on its weight and fineness. A momme (Japanese unit of weight) is approx. 4.306 g per m². The silk is often offered with the name pongee . A momme corresponds to a pongee, the fineness of the silk is given in “denier” den or “tex” dtex .

Designations based on origin or manufacturing process:

- Mulberry silk (SE) (cultured silk) is obtained from the cocoon of the silkworm of the mulberry spinner Bombyx Mori .

- Tussah silk (ST) (wild silk) is obtained from the cocoons of the wild Japanese Antheraea yamamai and Chinese Antheraea pernyi oak silk moth collected from trees and bushes , as well as from other butterflies of the genus Antheraea ( Antheraea mylitta , A. roylei , A. proyeli , A. paphia ). Since the butterfly has mostly hatched here, the fibers are shorter and cannot be unwound. A breeding of the Tussah spinners has not yet been successful.

- Mugaseide (Assamseide) is a gold-colored wild silk from India from the Mugaseidenspinner ( Antheraea assama ).

- Eriaseide (Eri-, Meghalayaseide) (breeding silk) from moth Samia cynthia ricini (eats Ricinusblätter ), very short fiber can only Schappe be used.

- Anapheseide (nest silk) (wild silk) of the African butterfly Anaphe panda (Syn .: A. infracta ), Anaphe moloneyi (Syn .: Epanaphe moloneyi ), very short fiber, can only be used as a schappe .

- African wild silk of the African moth ( Gonometa postica , Gonometa rufobrunnea )

- Yamamai silk (tensan silk) (wild silk) from the Japanese oak silk moth Antheraea yamamai .

- Ahimsa silk comes from India and comes from Eri and Tussah moth cocoons.

- Fagara silk (wild silk) from the atlas moth Attacus atlas .

- Circula silk (wild silk) from the Asiatic butterfly ( Circula trifenestrata )

- Koische Silk a silk that was used in antiquity, from the moth Pachypasa otus .

- Chappe or Schappeseide also foil silk from the outer irregular layers of the cocoon, inferior quality. short fibers. Under Chappe means all in the production of silk obtained, low-flosses have again different among themselves value (the waste from the filandes unwinding of the floss of the cocoons: Struse, Strusini, waste of twisting ). The cleaned waste is spun into chape yarn in the chape spinning mill. This differs from the actual silk yarns in that it has a somewhat rough, fibrous surface; it is sometimes also called Strazza .

- Cotton floss these are the threads that the spinner produces to hold the cocoon, inferior. short fibers.

- Bourette silk (coarse spinning process from short pieces of fiber)

- Flock silk Flock silk is the name given to the silk fibers that are brushed off when cleaning the silk moth cocoons before they are unreeled. Flocked silk therefore only consists of comparatively short fibers

- Pelt silk raw silk threads from low-quality cocoons

- Raw silk, in contrast to reel silk, raw silk is not cleaned of silk glue. The caterpillars hold their cocoons together with silk glue. The silk glue, also called silk bast, gives the raw silk a yellowish color.

- Grège, coiled, untwisted silk of the silkworm; consists of 3–8 threads and also contains the silk bast (sericin). Japanese - Djoshin silk yarn, Etschingo silk yarn, the best Japanese Grége silk.

- Ecrúseide not deboned, dull raw silk, with artificially hardened bast.

- Cuit silk, also known as "gloss silk", is very soft and shiny, 100% deboned, the loss of the silk glue results in a loss of strength.

- Soupleseide - natural silk that has been partially deburred with soapy water, weight loss due to the deboning process: approx. 8–12%

- Reel silk or mulberry silk (from the coiled filaments of the mulberry spinner ) Reel silk is the name given to the silk that is unwound in one go from the cocoon of the mulberry silkworm Bombyx mori. Since a thread made of reel silk no longer needs to be spun before further processing, it has a particularly smooth and uniform surface. This leads to the special sheen of the silk fabric. The silk threads are twisted together and then various silk fabrics are made from them.

- Noile silk has an overall smooth surface with very fine bumps. Among the different types of silk, noile silk is considered the finest and most exclusive.

- Kammzug silk - the radicals from the Rohseidenverarbeitung are first boiled in a large vat at about 90 degrees Celsius with hot, soapy water (degummed). The silk glue (sericin) is almost completely removed and up to 40% of the weight is lost. What remains is a fine, soft and shimmering white fiber material, which is processed into slivers ready for spinning by drying, tapping, opening and combing.

Wild silk such as tussah silk etc. is obtained from the cocoons of hatched butterflies that have not been bred under human supervision. When they hatch, they leave a hole, which tears the thread into several pieces. When woven, the threads are thickened, creating the characteristic, irregular, nubby textile surfaces.

The cocoons of wild silk can usually not be reeled in the same way as the cocoons made of cultivated silk of the silk moth (Bombyx Mori). A new method, a so-called “demineralization”, now succeeds in removing the mineral crystals that wild silkworms store between the fibers of their cocoons. These hard crusts not only damage the fibers, they are also the reason why wild silk, unlike classic mulberry silk, cannot be unwound in one piece.

Composition and structure

The silk of insects, like the silk of spiders, consists of the long-chain protein molecules fibroin (70–80%) and sericin (20–30%). Fibroin is a β- keratin with a molecular mass of 365,000 kDa.

The repeating sequence of the amino acids in fibroin is Gly - Ser -Gly- Ala -Gly-Ala.

The predominant secondary structure in the silk thread is the anti-parallel β-sheet . The quaternary structure of fibroin consists of two identical subunits, which lie parallel to one another, but face one another. This arrangement is stabilized by hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions between the subunits.

The complete molecules are arranged in parallel in the silk thread. The shine of the silk is based on the reflection of the light on these multiple layers.

Fibroin of the silk moth can exist in at least three conformations , from which different qualities of the silk thread result: silk I, II and III. Silk I is the natural state of the thread, silk II is found in the spooled silk thread. Silk III forms in an aqueous state at interfaces .

Since proteins are also polyamides , the silk thread is a natural polyamide fiber . Due to its chemical composition and the special, almost triangular cross-section of the fiber, the properties of silk differ specifically from those of synthetic polyamide fibers.

In addition to fiber proteins, silk also contains soluble (soluble in propylene glycol or glycerine) scleroproteins and other components:

| component | proportion of |

|---|---|

| Silk filaments (sulfur-free, high-polymer protein) | 70-80% |

| Silk bast | 20-30% |

| Wax components | 0.4-0.8% |

| carbohydrates | 1.2-1.6% |

| Natural dyes | 0.2% |

| other organic components | 0.7% |

maintenance

Because of their sensitivity to water, silk fabrics must be washed carefully by hand (using special silk detergents or mild soaps). A dry cleaning is possible. It is important to remove all soap residue. A teaspoon of wine vinegar can be added to the water . Silk must not be wrung out because it is sensitive to shape, especially when wet. Ironing is done inside out at a medium temperature of 130–160 ° C, whereby the silk should still be slightly damp. Chlorine bleaching and tumble drying are not possible. Silk is sensitive to the sun, the colors fade and the silk turns yellow. Therefore direct and strong sunlight should be avoided.

Use of language

Pure silk was an expensive clothing material that was only used in higher classes : “in velvet and silk”. Semi-silks are fine fabrics that only consist of 50% silk (in the weft) and the other 50% of worsted or cotton (in the warp). In the 19th century people who wanted to belong to the fine circle, but could only afford half-silk fabrics, were called half-silk . Especially women who, for example, as cocottes , moved in such circles without really belonging, were so named.

Today something is generally referred to as half-silk that is not entirely real and therefore only trustworthy to a limited extent: more appearance than reality.

Half-silk dumplings or dumplings are potato dumplings with a potato starch content of up to a third. With a higher starch content, they look silky gloss and are also known as silk dumplings or dumplings.

Worth mentioning

One of the reasons for the Mongols' military success was the wearing of silk clothing for protection. This, in combination with leather and light iron elements, could only be penetrated with difficulty by arrows and thus formed a light and functional armor.

Not only silkworms produce silk, but also mussels . The so-called mussel silk is also processed into textiles and used to be a definite status symbol.

See also

- House of Silk Culture in Krefeld (Ndrh.)

- Rayon

- Silk scarf

- Silk weaver

- List of silk museums

literature

- Heide-Renate Döringer: Silk: Myths - Fairy Tales - Legends. Spun stories along the Silk Road. Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2013, ISBN 978-3-7322-5402-6 .

- Peter Kriedte: A city by a thread. Household, house industry and social movement in Krefeld in the middle of the 19th century. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1991, ISBN 3-525-35633-1 .

- Andreas Mink: Silk: stability through trade. State secret and export hit. 6000 year old Chinese civilization. In: Structure . The Jewish monthly magazine. (= Myth of the Silk Road. Searching for traces: the beginning of globalization. ). 10th year, No. 7/8, Zurich July 12, 2010, pp. 25–27 (with additional articles on Benjamin von Tudela , the Sassoons and others in German, abstract in English).

- Anna Muthesius: Byzantine Silk Weaving: AD400 to AD1200. Fassbaender, Vienna 1997, ISBN 3-900538-50-6 .

- Xia Nai: Jade and Silk of Han China (= The Franklin D. Murphy lectures. No. 3). Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas 1983, ISBN 0-913689-10-6 .

- Andrea Schneider: The trading history of silk. Historical and cultural-historical aspects. GRIN Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-638-68856-7 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- Daniel Suter: Switzerland: silk weaving as an economic factor. Prosperity by a thread. In: Structure. The Jewish monthly magazine. (= Myth of the Silk Road. Searching for traces: the beginning of globalization. ). Volume 10, No. 7/8, Zurich July 12, 2010, pp. 22–24 (especially about Zurich , Basel ).

- Helmut Uhlig: The Silk Road. Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1986, ISBN 3-404-60267-6 .

- Herbert Vogler: The silk - legends and facts about the history of an exclusive fiber material. In: textile finishing. No. 35, H. 5/6, 2000, pp. 28-35.

- Hiroshi Wada: Prokop's riddle Serinda and the transplantation of silk from China to the Eastern Roman Empire. Dissertation . University of Cologne , 1971, DNB 720347998 .

- Hiroshi Wada: ΣΗΡΙΝΔΑ. A section from the Byzantine silk culture. In: Orient. Volume 14, 1978 pp. 53-69, ISSN 1884-1392 (The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan), doi : 10.5356 / orient1960.14.53 (full text as PDF file).

- Feng Zhao: Treasures in Silk. An Illustrated History of Chinese Textiles. ISAT / Costume Squad, Hangzhou 1999, ISBN 962-85691-1-2 .

- Baier, Otto: Textile goods for sellers , Fachbuchverlag Leipzig, 1959, DNB 450211630 .

- Otto von Falke : "Art history of silk weaving", Berlin, 1936, DNB 579370674 .

Web links

- Liliane Mottu-Weber : silk. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- History and care instructions

- The most important types of silk (PDF file; 105 kB)

- Appendix: Illustrations for silk production (English) Yong-Woo Lee, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Silk reeling and testing manual Food & Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO), 1999, ISBN 92-5-104293-4 .

- Silk information technical terms (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Silk figures, facts from swiss-silk.ch, accessed on March 26, 2016.

- ^ A b Franz Weber, Aldo Martina: The modern textile finishing process of synthetic fibers. Springer-Verlag, 1951. (Reprint: ISBN 978-3-7091-2424-6 )

- ^ Paul Heermann: Technology of textile finishing. Springer-Verlag, 1926, p. 51. (Reprint: ISBN 978-3-642-99410-4 )

- ↑ a b J. Merritt Matthews, Walter Anderau, HE Fierz-David: The textile fibers: Your physical, chemical and microscopic characteristics. Springer-Verlag, 1928, pp. 174 f, 212. (Reprint: ISBN 978-3-642-91077-7 )

- ↑ a b Hans-Georg Elias: Large molecules: chats about synthetic and natural polymers. Springer-Verlag, 1985, ISBN 3-662-11907-2 , p. 105.

- ↑ Wolfgang Bobeth (Ed.): Textile fibers. Texture and properties. Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg / New York 1993, ISBN 3-540-55697-4 , p. 167.

- ↑ P.-A. Koch: Recipe book for pulp laboratories. Springer-Verlag, 1960, p. 127. (Reprint: ISBN 978-3-662-12921-0 )

- ↑ IL Good u. a .: New Evidence for early silk in the indus civilization. In: Archaeometry . Jan 21, 2009, doi: 10.1111 / j.1475-4754.2008.00454.x .

- ↑ Philip Ball: Rethinking silk's origins, Did the Indian subcontinent start spinning without Chinese know-how? In: Nature . Feb 17, 2009; doi: 10.1038 / 457945a .

- ↑ Archaeologists discover the oldest silk remains. In: scinexx.de. Retrieved January 3, 2017 .

- ↑ Yuxuan Gong, Li Li, Decai Gong, Hao Yin, Juzhong Zhang: Biomolecular Evidence of Silk from 8,500 Years Ago. In: PLOS ONE . 11 (12): e0168042. December 12, 2016, accessed January 3, 2017 .

- ↑ Pliny: Naturalis historia 11, 26, cf. Silk in the Ancient Rome .

- ^ Heide-Renate Döringer: Silk: Myths - Märchen - Legenden , BoD Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2013. ISBN 978-3-7322-5402-6 . Chapter 6, p. 88: The legend is referenced with the wrong source “Flores” (recte: the Roman historian (Annaeus) Florus ).

- ^ A b c d William Bernstein: A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World. Atlantic Books, London 2009, ISBN 978-1-84354-803-4 .

- ^ Robert Sabatino Lopez: Silk industry in the Byzantine Empire. In: Speculum . 1945, pp. 1-42.

- ↑ Raffaello Piraino: Il tessuto in Sicilia. L'Epos 1998, ISBN 88-8302-094-4 , p. 142.

- ^ Amy Butler Greenfield, A Perfect Red - Empire, Espionage and the Qest for the Color of Desire. HarperCollins Publisher, New York 2004, ISBN 0-06-052275-5 , pp. 5 and 6.

- ^ Armin Torggler: Of gray loden and colored cloth. Considerations on the cloth trade and textile processing in Tyrol. In: Verona-Tirol. Art and economy on Brennerweg until 1516. (= Runkelsteiner writings on cultural history. 7). Athesia-Verlag, Bozen 2015, ISBN 978-88-6839-093-8 , pp. 199–245, especially pp. 238–241.

- ^ History of the development of the city of Neustadt an der Aisch until 1933. Ph. CW Schmidt, Neustadt ad Aisch 1950; 2nd edition ibid 1978, p. 431.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Alois Kiessling, Max Matthes: Textile specialist dictionary. Fachverlag Schiele & Schoen, 1993, ISBN 3-7949-0546-6 .

- ↑ a b Seidenarten on seidenwelt.de, accessed on March 26, 2016.

- ^ A b Max Heiden: Concise dictionary of textile science of all times and peoples. Salzwasser-Verlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-8460-1109-6 .

- ^ A b Alfred Halscheidt: Textiles from AZ. Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2011, ISBN 978-3-8448-5871-6 .

- ↑ The most important types of silk ( Memento from January 31, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 102 kB), accessed on July 28, 2016.

- ↑ types of silk on disogno.de, accessed on 26 March 2016th

- ↑ Thomas Meyer to Capellen: Lexicon of tissues. Technology, ties, trade names. 4. fundamentally updated u. extended edition, Deutscher Fachverlag, Frankfurt am Main 2012, ISBN 978-3-86641-258-3 , pp. 271–272 (article “Organsin”).

- ↑ Duden Pariseide

- ↑ Silk Jersey at seidenjersey.wordpress.com, accessed July 28, 2016.

- ^ A b Hermann Ley, Erich Raemisch: Technology and Economy of Silk. R. O. Herzog (Ed.). Berlin: Springer 1929. p. 7. (Reprint: ISBN 978-3-642-99258-2 )

- ^ Phyllis G. Tortora, Ingrid Johnson: The Fairchild Books Dictionary of Textiles. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014, ISBN 978-1-60901-535-0 .

- ^ Valerie Cumming, CW Cunnington, PE Cunnington: The Dictionary of Fashion History. Berg, 2010, ISBN 978-0-85785-143-7 .

- ↑ Thomas Meyer to Capellen: Lexicon of tissues: Technology bindings trade names. dfv Mediengruppe Fachbuch, 2016, ISBN 978-3-86641-503-4 .

- ↑ Substances (PDF; 200 kB), accessed on July 28, 2016.

- ↑ W. Spitschka, O. Schrey: cotton fabrics and curtain fabrics. Springer-Verlag, 1933, p. 162. (Reprint: ISBN 978-3-642-50795-3 )

- ^ RK Datta: Global Silk Industry: A Complete Source Book. APH Publishing, 2007, ISBN 978-81-313-0087-9 , p. 179.

- ↑ K. Babu Murugesh: Silk: Processing, Properties and Applications. Elsevier, 2013, ISBN 978-1-78242-158-0 , p. 5 f.

- ^ Henri Silbermann: The silk, its history, extraction and processing. Volume 2, published by HA Ludwig Degener, 1897, p. 311.

- ↑ a b Sara Lamb: The Practical Spinner's Guide - Silk. Interweave, 2014, ISBN 978-1-62033-520-8 , p. 18.

- ↑ a b Ryszard M Kozłowski: Handbook of Natural Fibers: Types, Properties and Factors Affecting Breeding and Cultivation. Woodhead Publishing, 2012, ISBN 978-1-84569-697-9 .

- ^ L. Rothschilds: Paperback for merchants. GA Gloeckner, Leipzig 1902.

- ↑ Pelseil. Spelling, meaning, definition, origin. In: Duden.de. Retrieved January 13, 2013 .

- ^ J. Merritt Matthews, Walter Anderau, HE Fierz-David: The textile fibers: their physical, chemical and microscopic properties. Springer-Verlag, 1928, pp. 198 ff. (Reprint: ISBN 978-3-642-91077-7 )

- ↑ SEIDEN-KAMMZUG ( Memento from July 28, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) on natural-yarns.com., Accessed on July 29, 2016.

- ↑ Wildeseide on Spektrum.de, accessed on March 26, 2016.

- ↑ Tom Gheysens, Andrew Collins, Suresh Raina, Fritz Vollrath, and David P. Knight: Demineralization Enables Reeling of Wild Silkmoth Cocoons. In: Biomacromolecules. 2011, Volume 12, Issue 6, pp. 2257–2266, doi: 10.1021 / bm2003362

- ↑ Urs Albrecht: Three-dimensional structure of proteins (Voet Chapter 7) 2. Fiber proteins. B. Silk fibroin - a β-sheet structure. (PDF, 7.82 MB) In: University of Friborg, Department of Biology, Biochemistry. P. 6 , accessed on January 13, 2013 .

- ↑ Orientation of silk III at the air-water interface. In: International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. Vol. 24, Iss. 2-3, 1999, pp. 237-242, doi: 10.1016 / S0141-8130 (99) 00002-1 .

- ↑ Silk Lexicon. In: Spinnhütte Celle business park. Archived from the original on January 6, 2008 ; Retrieved January 13, 2013 .